|

[Previous Page]

Chapter

II.

MR. FREDERIC HARRISON

HALF A CENTURY'S FRIENDSHIP

WHAT a subject

have I here, more than full enough for a volume, and only to be

inadequately dealt with in a monograph, a paper suited to The

Quarterly or Edinburgh Review.

My intercourse, personal and on paper, with the last of the

great Victorians and the doyen of letters throughout the Edwardian

and Georgian periods until the present time, began more than fifty

years ago. Proudly, indeed, do I enter upon a record so full

of interest to the general reader and so fruitful to myself. At

every stage I am brought face to face with momentous events and

phases of thought, political, social, and religious problems long

since solved, for better or for worse. And the more closely I survey

the delightful task before me, the more incompetent do I feel in

dealing with it. For I cannot aver of myself, as of my illustrious

and, by five years, my senior contemporary, that I am still in the

plenitude of bodily as of mental vigour. Time, on the whole, has

dealt very kindly with me. In the diamond jubilee of my literary

career—1857-1918—I enjoy entire immunity from "that which doth

accompany old age," defective hearing, vision, and perception. Nor

can I complain of what is even worse to bear—namely, slights and

oblivion. No more generous body exists than the novel-reading

public. Newcomers, however brilliant their debut, however numerous

their editions, do not hustle old favourites off the stage. A

novelist whose first work attains the rank of a classic, modest

although it be and modest as may have been its author's emoluments,

cannot arraign Fortune.

Friendships equally with achievements make red letters in our

calendar. How I wish that I had put down in writing the exact date

and precise circumstances of first encountering kindred and

inspiring souls, those men and women who have straightway enriched

life and opened new fields of thought and endeavour. The aftermath

is remembered, the spot on which fell the handful of seed is

forgotten. Fortunately, Mr. Frederic Harrison's memory is better

than my own. On referring the subject to him, he writes:

MY

VERY DEAR MATILDA,

— I am on holiday—at last—having read and passed for press within

the last five to six weeks my book of 460 pp. and four Review

articles, and written piles of MS. on various matters. So I take a

quarto page, a new pen, and my most amiable spirit to reply to your

very grateful letters. My memory holds out still, and I have a rough

diary of mere incidents and movements posted up since the year 1829,

the year in fact of my parents' marriage. (N.B.—From 1829 until 1847

these entries were from my father's books of accounts. He entered

every 6d. of expenses from setting up house, and I have those books

now. My wife, in The Cornhill Magazine, wrote a most interesting

paper on the habits of an early Victorian household out of these

diaries, and I used them in my own Autobiographical Memoirs, vol. i.

ch. i.) So your inquiry as to our first meeting. It was in July

1890. We were then passing the summer in our cottage—Blackdown

Cottage, Haslemere, in Sussex, not in Surrey, an old cottage and

farm on the Blackdown, which is 1030 feet high (not Hindhead, which

is eight miles off in Surrey). Our pretty old place stood 800 feet

above sea, and had magnificent views over the Weald of Sussex, four

miles from Haslemere Station, and one mile from Aldworth, Tennyson's

summer house. Why you wrote to me, and why you so kindly promised to

visit us, you know better than I. Anyhow, we were proud to have you

as a guest. We sent our man and carriage to fetch you from Haslemere. Our coachman, Williams, after twenty-four years' service with us,

is now driving a great motor omnibus in London.

Yes, it was twenty-eight years ago when I had the happiness to hand

out a bright and smiling lady who seemed to be on the right side of

fifty. It was love—i.e. lifelong friendship—at first sight, and we

have been lovers, in the sense of close and intimate friends in

thought, ever since. We spent a happy day rambling about that

timbered hill with our daughter, not quite four, and with Bernard,

not quite nineteen, from his first year and the Studio in Paris. How

well I remember that visit! Now for replies.

As I said, my articles were in first numbers of the three Reviews,

Fortnightly, Nineteenth Century, the third is The Positivist Review. It (the P.R.) contains 32 pp. every month, words of wisdom—from

others as well as mine. In 1917, the Review contained each month my

"Thoughts on Government," being a reissue of Part I. of my

Order and

Progress, 1875. This present year, 1918, it contained my (new)

"Moral and Religious Socialism," which began in May and continued up

to August. These two years contained a profoundly full summary of

the entire political and economic synthesis according to the Gospel

of Augustus Comte. They were as lucid as they were philosophic, not

from my own ability but from the truths of the Master. I am only the

phonograph. But all this—purely gratuitous—indeed, was published

at our own cost—was utterly unheeded, unknown, and buried. Not even

friends would spend their pennies in getting it. Probably only two

or three score people read it, and only two or three of these quite

understood and accepted it. All pure waste in our lifetime. Yet by

2018 A.D., or say A.H. I, these little pieces will be held to be as

well worth study as, say, Burke on the Revolution or his "Thoughts

on the Present Discontents." People will read any chatter, short

stories at 6s., and will buy dozens of picture papers at 1s. each,

but will not give 3d. [p.20-1]

for real wisdom. My life is spent in pouring out precious wine into

glasses without bottoms, so that all runs into the sewer. [p.20-2]

. . . My first visit to the East was from October 1 to November

1890—to Constantinople, Athens, and Rome. Lectured on Homer at

Newton Hall on November 2, the day after my return from sight of

Troas; lecture almost extempore, now in my Among my Books, 1912, ch.

viii. On November 15 I lectured on Athens at Toynbee Hall. This is

now in my Meaning of History, 1894, ch. x., and it is one of the

most suggestive things I ever wrote. (N.B.—John Morley was reading

it in the train coming from London to Bath the other day, and highly

praised it as real history.) So that not everything I write passes

like "bubbles in the air." Theophano was in twelve numbers of

The

Fortnightly, and was written at intervals over a whole year from

month to month. But the tragedy of Nicephorus was written as a

whole, and has a systematic plot and catastrophe, in form modelled

on Alfieri and Goethe rather than Shakespeare, and without any

attempt at poetic phraseology. I intended Tree to play it, but he

found it too big and costly, and, as Henry Arthur Jones told me,

Tree saw that the woman's part would overpower him. Mrs. Pat

[presumably Patrick Campbell] has read it. Well, here it is.—Yours

always devotedly,

FREDERIC HARRISON.

The play itself I give an account of farther on, and I here give a

few extracts from these letters, not one without typical literary

and, needless to say, personal interest, diversely written in

French, English, and Latin.

BATH,

Juin 12, 1913.

(Gerbert, [p21] 125).

Le volume est arrivé. Admirable, mieux que jamais.

Comparable à George Sand.

I am not sure whether this high compliment was paid to my The

Dream Charlotte or The Romance of a French Parsonage,

both published some years before.

BATH, July 3, 1913.

I have returned my little Introduction [to The Lord of the

Harvest] marked for press without alterations in word or in

letter. I never correct a proof except to note printers'

blunders. Reading it in print, I like it as well as anything I

ever wrote, and that because I enjoyed it. You inspired me,

and I trust I caught some flavour of your idyllic tone, and that I

kept the "values true," as painters say.

Everyone has his little vanities, and my vanity is fine calligraphy,—see what a lucid and artistic hand is this,—and my whim is never to

alter a word in a manuscript or even in a letter. I follow Pontius

Pilate, a fellow of good sense, who has never been appreciated.

Quod scripsi, scripsi, said he, and so say I.

I enclose you my MS. to show you how I write for the press—tout

d'un trait. I am sure that fifty years hence the MS. of your

Lord of the Harvest will be secured for some library, and I wish

that but one page of my little Foreword may be preserved, tacked to

your copy.—Your aged friend and more than ever true admirer,

F. H.

March 8, 1914

(Thucydides, 126).

I rejoice to hear of your literary success. We both urge you to get

your Suffolk Courtship put into "Everyman." . . . I find that

I can read no new books—except yours. I spent my afternoons [of a

holiday sojourn with his wife near Bath] over Sophocles, Æschylus,

and now Xenophon on Socrates. [Oh, Mr. Harrison, Positive and

anti-female Suffrage as you are, you might here have alluded to the

accomplished woman scholar Elizabeth, whose translation of that

famous book has long been a classic!] And I have just finished

Tristram Shandy—my copy is first edition, 4 vols., 12 mo,

1765—and Don Quixote in a translation. I find the Spanish

difficult, but I can read The Positive Review of Mexico,

which translates our Calendar month by month. And I have Furtwängler's Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture—grand Greek

sculpture is my only hobby.

I entirely agree with you as to Bulwer [I believe re my admiration

of his Last Days of Pompeii and Rienzi]. If you saw

Bath forty years ago, you may be assured that it is almost the only

city in England which has not been changed. It has not grown and has

no new buildings. There is only one, the new hotel (a view of which

I enclose). (Shakespeare, "How many evils have enclosed me round!")

The charm of Bath is its magnificent country round, its parks,

gardens, and endless walks, etc., its mild climate, daily music, and

agreeable society. We know all whom we care to know, especially

clerics, bishops, archdeacons, rectors, and the best houses within a

motor drive. I belong to the Philosophical Institute and to the

Literary Club, and my wife works her Anti-Suffrage Committees.—With

her love and mine, ever your

FREDERIC HARRISON.

With regard to this letter I wrote suggesting that the Archdeacon

and his new friend should change pulpits on Sundays, so refreshing

and such a tonic to both congregations!

BATH,

April 6, 1914.

Many

thanks for your letter and the kind words of Professor Hales, whom I

well remember years ago as one of the F. D. Maurice men. I am sure

that your Lord [of the Harvest] will have a long

reign.

By way of rousing intellectual elements dormant in Bath, I resolved

to read my Nicephorus in the old historic theatre here,

before our friends and a lot of Bath people. It has been adapted and

translated into German for an opera, and is now being translated as

a play in full. And, in order to secure copyright "acting rights,"

it has to be produced in a public theatre. So I took the title-rôle

myself, and got the amateur dramatic society to read it in parts on

the stage before an invited house. They all said they

heard—especially Nicephorus; and they seemed interested. One lady

who is deaf, and cannot hear a sermon in church, heard "every word" in the theatre. [Quite naturally, for she was not sent to sleep by

curate's twaddle-dum-dee!] . . . In any case, it was an event this

première of tout Bath.

I took this up partly to relieve my feelings about the awful public

crisis. We are going straight to the most horrible catastrophe in

English history. Ere this year is over, Britain will be in the

throes of dissolution. It is no use trying to make any more

compromises. I don't know which side is the most culpable. But civil

war is inevitable, and all without any real principle to fight

for—and certainly nothing but generations of evil to follow on it.

I am obliged to you for telling me about our Professor [the late Mr.

Beesly]. I have [had] no correspondence with him for some time. We

are likely to differ so deeply that I fear to write and could not

bear to open a discussion. I can hear his snort of contempt if he

ever heard of my playing in a theatre. I am a Gallio, I know, but

now a very sad one.

Oddly enough, I should say, were not oddities so-called of daily,

hourly occurrence, an early letter of Frederic Harrison has just

come to hand. I had taken up that striking Byzantine play,

Nicephorus, 1906, to re-read, when out slipped a letter which

ran as follows—we had not yet called ourselves by our baptismal

names, nor had I as yet received one of his epistles in Ciceronian

Latin. These endearing privileges were to come.

10 ROYAL

CRESCENT, BATH,

April 14, 1914 (Archimedes, 126).

DEAR MISS

BETHAM-EDWARDS,—Many

thanks for your letter and views and all. If you really wish to read

my tragedy, let me present you with an author's copy. I prefer it as

a work of art to the romance of Theophano [by himself. Macmillan]. That was not written as a whole with a general plan at

all. It was taken up to give miscellaneous illustrations of the

Byzantine world of the tenth century, which I had been studying for

years. It came out in the twelve numbers of the Fortnightly.

. . . I am busy enough. I am continuing my Last Thoughts, and

have just finished my Commentary on the Common Prayer [Book?] and

Catholic Missal. My notes on our Calendar go on in the Pos. Rev.,

and next week I am writing a review of Bridges' Bacon. I have

promised to read a paper on R. Bacon at our Bath Literary Club, and

I shall give a course of history lectures for the Bristol University

branch at Bath. So I have enough to do—after sweets, the sour!

Your words about Ireland show me how unfit the ablest and best women

are for politics. They judge by their hearts, not their heads, and

mistake vague ideals for observed facts. [I fancy this refers to the

Casement incident.] Bloody war in Ireland, and possibly in England,

will not transfer cottagers to Abergavenny Castle. It will only keep

Liberal policy out in the cold for a generation. —Yours always

devotedly,

FREDERIC HARRISON.

Such a compliment I cannot omit, but blushingly set down. Who so

modest as the really great? To think of F. H. thanking M. B.-E. for

a word of praise!

April 25, 1914.

"It is indeed a memorable compliment to me that you should take the

trouble to read my play, and with such minute attention and such

accurate memory. Your note about Princess Theodora not being in the

Dramatis Personæ had escaped me. I think she was thrown in at the

last moment to heighten the contrast between the callousness of the

wife and the grief of the sisters of Romanus, and perhaps also to

enable Tree to put on the stage another pretty girl (and Byzantine

court robes. . . . Yes, there are too many Johns). [In the

dialogue.]

BEAU RIVAGE

PALACE,

OUCHY, LAUSANNE,

July 2, 1914.

Your letter reaches me here, but not the book. We both left Bath on

Monday, 22nd ult., with Olive for the first tour we have taken

together for twelve years. My wife's health has been so much

improved at Bath that we felt moved to go to Paris, partly to see

Bernard's three pictures [their eldest son] well placed in the

Salon, to make acquaintance with his many friends in Paris—artists,

connoisseurs, and patrons of his; secondly, to our Positivist

Society, where I was asked to give them my personal reminiscences of Auguste Comte, being now the only survivor of those who saw him and

talked to him in 1855.

Our journey (broken at Dover) did my wife no harm, and though she

did not attempt to walk in Paris, she was able to go to the Salon,

the Studio, the Luxembourg, and the meeting in the new rooms of our

Society. The reunion was most interesting—about one hundred

members, old and new. The President said fine things of her and me,

and I spoke for thirty minutes, reading parts of my presidential

address to the Sociological Institute—the English form of which will

be in the Positive Review for August. . . . The principal

etcher in Paris has etched in colour two of Bernard's Italian

landscapes, which G. Petit, the boss of painters (the G. Petit

Gallery is an annual exhibition), has purchased. So our visit was a

business affair for B. of much value. And our visit to the new rooms

of the Society was greatly appreciated by them and enjoyed by us. Bernard and I took Olive about to the various galleries, shows, to

the Bois de Boulogne, Bagatelle; and B. took her to the theatre. We

did not go out but lived en pension. After a week in Paris,

which by Sunday got very hot, we came on the 30th to this place. Our

Bath doctor thought it would be of use to my wife. . . . Ouchy is my

old favourite haunt, and I was really athirst to see the snow

mountains once more—of course, we shall not go touring about here. At present the Lake is not too hot, but 72º F. in my rooms—but we

may go up to some place on the hills, the doctor insists not above

4000 feet. At that, he thinks Switzerland will do her good. She is

wonderfully well in general health, and everyone says she looks

twenty years under her age. Only she has to be very careful not to

stand or walk.

As for me, I am quite well, I think. I can walk for two or three

hours uphill, and sleep well; but I hardly eat anything but eggs,

and fricassees, and vegetable food. I have brought some classics and

some poets, and have been since 6 a.m. in our balcony reading Horace

and Shelley at intervals, and looking across the Lake at the

Dent-du-Midi and Savoy Alps, and dreaming of glacier excursions, and

of Byron and Gibbon and all the memories of this centre of European

traditions. The regicide Ludlow, who lived and died at Vevey,

inscribed on his door:

Forti omne solum patria.

I inscribe:

Sapienti—solum Helveticum—patria.

Our travelling abroad together for once all these years—our tour to

Switzerland, for our last look at the Delectable Mountains—has been

a bold experiment, but it has succeeded, as yet. Outside, in France,

in Europe, in the Balkans, in Ireland, I see nothing but chaos and

battle. I cannot write a word on it.—Yours always devotedly,

F. HARRISON.

November 28, 1914.

I have been much pleased with your little volume. That bit about the

Marseillaise is really most interesting and authentic, after

Lamartine's gush. And the account of Doré interests me much. I had a Doré phase once myself. Do you know his Rabelais? Did I not once

before ask you this question? Do see Austin's new little book,

The

Kaisers War, with an Introduction of mine. The Kaisertum is

cracking up. But I fear our Radical Pacifists will try to stop

bringing the war to its proper end. There will be a desperate effort

to call uti possidetis, "as you are," a drawn battle about Easter. Germany is still in Russia, France, Belgium. Her borders are

untouched.—Yours always, F. H.

March 21, 1917.

MY VERY

DEAR FRIEND,—I

am indeed grateful to you for giving me news of yourself, and I wish

you joy most heartily on the success of your new book [Twentieth

Century France. Chapman & Hall]. It is a fine compliment from

the great Frenchman. [p.30-1]

I must see it as soon as I am free of work. I am now just finishing

my memoirs of all I have lost in Her [his beloved wife], and have

made a collection of her essays to make a volume, I trust, after the

war. In making a record of all her activities, I am amazed at the

great mass of various tasks she took and completed in spite of her

poor health and many domestic cares. No one has any idea of what she

did. Our outreaching towards Humanity owed more to her than to any

of us men. Why am I left, the useless one?—and she who could have

done so much more is gone. Your beautiful "In Memoriam" [Westminster

Gazette] I purpose to put as the motto of the volume, and her

hymn, No. 58, [p.30-2] as the

L'envoi. . . .

I am re-issuing my "Thoughts on Government," 1874, in the current

Positive Review. I foresaw forty years ago the House of Commons

pretending to govern. And the French Chamber is as bad as

ours . . .

(Re Scott's novels.) I have always thought The Black Dwarf

one of the very worst. When I was at Ruskin's in 1899 he gave me to

read in Scott's own MS. that he bought, a folio or quarto written

about 2500 words every morning. That beats you.

I read no new book at all—I am now reading only tragedy: Sophocles'

Antigone, the greatest of all tragedies; Corneille's

Horace, Racine's Athalie, etc. etc. . . . I have been

occupied every afternoon this month by Lord Rosebery, who comes to

take me out in his car, or to take a walk with him in the parks and

country. He is a brilliant talker.—Affectionately yours always, F. H.

On November 6 of 1917 comes the following in Ciceronian Latin:

Fredericus Matildae suae S.D.

Gratissimo sane animo recepi litteras tuas amabiles, anno aetatis

meae sexto et octogesimo jam peracto. Socii enim sumus et aequales in

senectute, in litteris, in cogitationibus tam de rebus publicis quam

de rebus divinis. Nihil prorsus habemus, O sodalium meorum superstes

unica, quod senectutem accusemus. Anni quippe octogessimi corporibus

nostril nihil intolerabile afferunt, dum mentibus nostris—gratias

agamus Sanctae Humanitati—pauca certe detrahunt. Hoc si incredibile

videatur junioribus, qui nugis trivialibus vacare solent, monendum

est nos—praesertim te amica mea venerabilis—e juventute prima

animum totum dedisse in litteras vere humaniores, tam Graecas quam

Latinos, tam in versu quam in sermons pedestri scriptas. Quid dicam—non

solum in litteras Anglican led in quidquid France et externae gentes

optimum et celeberrimum tradiderunt.

Mirabile est quomodo stadia nostra in idem consentire videantur. Libros illos quos hodie te legere mihi scribes, ego autem praecipue

in menu habere soleo. Nihil pusillum, nihil vulgare, nihil obscenum

aut obsoletum in bibliothecam meam intrat. Die noctuque verso

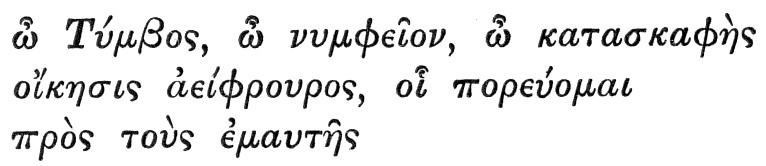

praeclaras illas veterum tragedias et comedias—praesertim Aeschyli

Septem. Quippe τριλογίαυ Άτρειδώυ censeo ingenii humane maximum

partum fuisse, Swinburnius noster recce aestimavit. Si quis velit

Sophoclem—Graecorum omnium dulcissimum—senem ilium qui ad

nonagesimum annum novas tragedias fecit—Aeschylo proxime accessisse,

certe hoc erat in Άυτιγόυης suea τραγικωτάτη illa

orations Virginis moriturae:

Homeri, Aeschyli, Sophoclis et Aristophanis opera

omnia recenter perlegi—Euripides non aeque mihi arridet, forsitan e

memoria lugubre scholarium dierum. Inter Latinos, Vergilius,

Horatius, Catullus, Juvenalis, Plinius maxims me delectant. Lucretium, Taciturn, Persium studere laboriose potius quam legere

vacue fas est.

Hic legendi meus est mos. Mane, adhuc in lecto requiescens, cantica

illa recito quae conjux mea in aeternum deploranda tanto studio et ingenio confecit. Haec

sunt preces matutinae. Tum, quum epistolas

receptas, actorum diurnas scriptural ephemerides illas perfecerim,

converto me ad Ajacem Sophocleum cum commentariis optimis Ricardi

Jebb, aut "Poetae" nostri W.S. aliquid, vel Idyllium quod

Tennysonius noster e carminibus vetustis Med: Aevi elaboravit. Tandem in cubiculum scandens Scotti nostri incomparabilis historian

nonnullam mecum porto.

Morem legendi tuum, precor, mihi quoque describere velis.

Scribebam Bathonia die Vico. Nov. A.D. 1917.

If you want details and dates, turn to my

Autobiographic Memoirs (Macmillan, 8vo, 2 vols., 1911). It is

the most veracious, shameless, naked, unveiling, disembowelling

exposure of a man's inside ever seen in literature. [p.33] In its

800

pages it tells almost everything I could remember and find recorded

in letters, diaries, or books, even common trifles from October 18,

1831, down to October 18, 1911, when it was first published, ætat.

80. But even if you read that through with all the huge

bibliography, pp. 335-345, you would not know half what I have done,

seen, and written. Without that remarkable classic (as in the

twenty-first century it will be) you would not know one per cent of

my doings and writings. People here in Bath have no idea of what I

am or have done or written. It is not a double life I lead, a Hyde

and Jekyll [p.34-1] affair—it is a centuple life I lead. I have been, seen,

done, written fifty things they never heard of [dear harmless old

ladies and gentlemen, how should they?]. There is almost nothing

that I have not tried [p.34-2]—even stag-hunt, fox-hunt, hare-hunt. I have

ridden a race-horse on a race-course, and have been at all the great

great races, at times driven in my dog-cart, and in a four-horse

drag [carriage or coach, Thackeray], etc. etc. I have often been on

the top of every great mountain in Scotland, Wales, Cumberland,

Alps, Pyrenees, Apennines, Austria, and Greece. I have yachted in

the Channel and in the Mediterranean. I have been in every capital

and great city in Europe barring Madrid and Seville, and also in the

U.S.A. I have worked in every museum in Europe barring Madrid, and

have talked with nearly every famous politician and writer in

Britain, France, Italy, U.S.A., Holland, Greece, Turkey,

Scandinavia. I have been down coal-mines, I am an enrolled member of

two great Trades Unions. I have been the guest and the host of many

Labour leaders, including a visit to a prisoner in the Conciergerie

[no explanation], and I witnessed the decapitation of an Italian

officer in a riot. I was present at the Italian vote in the Duchies

for Victor Emmanuel and at the election of Tricoupis in Athens. I

have shaken hands with Gambetta, Mazzini, Victor Hugo, Garibaldi,

and sat in the gallery of the House of Commons beside the Comte de

Paris. I have heard every great actor since Macready and every

actress since Rachel and Grisi. I have tried everything—have been an

alderman, a J. P., an LL.D., D.C.L., Litt. D., a horseman from

boyhood, a swimmer, a mountaineer, a waltzer, a card-player, a

diner-out, member of a dozen clubs, a man about town, a Park

revolutionary orator. Only two things I have always barred: (1)

Tobacco in any form and drink. (2) Sport, meaning killing of

animals. But I have been on the Alps with hunters and have walked

over most moors in Scotland and Britain—indeed, have owned game

preserves. . . . Well, I can't go on. I only want to assure you that

you will never get to the end of me. . . .

I am really going to stop writing for the public now. I am going to

rest and read old books. I have always had of late at my bedside

Plato, and mystical stuff it is, and Malory's Mort d'Arthur, far

finer than Tennyson's "fashion-plate" Idylls. Now I am going to read

through Plutarch's Lives.

Glorious news! Early victory.—Your devoted friend,

FREDERIC.

From a later note about the same time:

I rejoice to hear that you are so cheerful and so

busy. We have just got home to Bath, having had three weeks at Lyme

Regis, far the most interesting and pleasant of all Channel ports, a

real old harbour of Plantagenets and Tudors—sent out ships to the

Armada, keeps her old stone breakwater. Read Persuasion. I am

wonderfully well. . . .

Then follows a sentence on the quite imaginary indifference of the

reading world to his own works. He styles himself effete, passé, oublie,

mort, as many others of his mental height in moments of

depression have done before.

"Will anyone read my novels when I am gone, doctor?" asked the great

Dumas of his doctor when on his dying bed. "We always give one to

patients about to undergo an operation," was the retort. "Straightway their own case is clean forgotten, and the ordeal is

cheerfully met."

――――♦――――

Chapter

III.

GEORGE ELIOT AND MADAME BODICHON

I.

IT was in the

spring of 1867 that I first met the great woman novelist now known

throughout the entire reading world. Our acquaintance began in this

way. I had spent the winter in Algiers under the roof of that

remarkable pair, Dr. Eugene and Madame Barbara Leigh-Smith Bodichon. The doctor had won his titles of fame by valuable works on the

colony, also by equally valuable medical services during visitations

of malaria, and last, but not least, when Deputy of the Chamber, by

his motion to abolish slavery throughout the French African colony,

a measure which was straightway carried into effect. Daughter of a

landed proprietor, Benjamin Smith, M.P. for Norwich, his English

wife before her marriage in 1857 had done much for education and the

improvement of the legal status of her sex. A charming water-colour

artist, she never attained the position her gifts merited, too many

objects occupying her ever-active mind. With her husband she

did much to improve hygienic conditions of the Algerian plain by

vast plantations of the health-giving American Eucalyptus globulus.

A rich woman, her wealth was always spent upon great objects, and as

the foundress of the first University for women (Girton College) in

the United Kingdom, she has won for herself an imperishable niche in

history. Women are very disloyal to each other, and her

biography yet remains to be written. No Girtonian has troubled

herself about her benefactress.

This noble woman was my intimate friend, and at the date I

mention we had returned together from a tour in Spain and a winter

in Algiers, myself, for the nonce, being again her guest at 5

Blandford Square.

On the morning after our arrival she said

"Now, Milly" (that was what the French call the petit nom

always used by my family and familiars), "put on your bonnet and go

with me to the Priory. I will ask Marian if I may present

you."

My heart leaped at the proposal, for I knew that Marian was

the baptismal Mary Ann thus euphemised by George Eliot's closest

friend.

The Priory, that celebrated "gathering-place of souls," to

quote our equally great Victorian poetess, was one of the many St.

John's Wood villas almost to be called country retreats. The

comfortably proportioned two-storied residence, approached by a

drive, stood sufficiently apart from the road as to ensure its

inmates comparative quiet. Here Mr. and Mrs. Lewes lived

historic years; and although uncemented by legal ties, never was

union more complete or more fruitful in blessing to both: wit and

perennially youthful spirits on his part lightened the weight of

thought on hers, and kept alive the all-saving grace of humour.

Even her best friend could not introduce anyone without

permission. So I waited inside the gate till my hostess

beckoned me, and there I was in the presence of a tall, prematurely

old lady wearing black, with a majestic but appealing and wholly

unforgettable face. A subdued yet penetrating light—I am

tempted to say luminosity—shone from large dark eyes that looked all

the darker on account of the white, marble-like complexion.

She might have sat for a Santa Teresa.

Unaffectedly cordial was my reception, but hardly had I

recovered from one thrill when I was bouleversée, as the

French say, by the glamour of another. The conversation

naturally turned upon Spain, when suddenly Mr. Lewes accosted the

great woman with boyishly enthusiastic cameradeship.

"Now, Polly, what say you to this?"

Bishop Proudie in Trollope's immortal scene could not have

been more thunder-struck at hearing "the wife of his bosom called a

woman" than I was then.

What the "this" referred to I forget, but very possibly to an

idea afterwards carried out. In the following year Mr. and

Mrs. Lewes followed our footsteps south, their journey resulting in

The Spanish Gypsy, a poem, despite the invention of its

heroine's exquisite name and many fine lines, now all but forgotten.

As an hour later we passed out of the gate, my friend began:

"Shall I tell you Marian's compliment to yourself? 'I

congratulate you, dear Barbara,' she said, 'on possessing a friend

who is without fringes.'"

It is the only time that I have ever heard the word "fringes"

used for "fads," [p.40] and the

only time I ever received a commendatory one from the same lips.

How much more gratified should I have been had she expressed her

pleasure at meeting the authoress of such and such a novel!

But I can understand her reticence. What, indeed, would life

have been worth had she once begun to receive the confidences and

aspirations of youthful tyros? Her lot would have been worse

than Miss Mitford's.

My hostess's invitation to dinner for the next day was

accepted, and circumstances grave and gay made the occasion equally

ineffaceable. Quite sure of the great visitors' punctuality,

we awaited them in the drawing-room. True enough, the street

bell rang on the stroke of seven. What was Madame Bodichon's

dismay when her incomparable parlour-maid threw wide the door with

the announcement:

"Captain and Mrs. Harrison."

Then came a ripple of laughter—George Henry Lewes' hearty and

unfeigned, George Eliot's slightly remonstrant. The name was a

joke. It was beyond her competence to play the child. In

excellent spirits the simple but well-cooked dinner was partaken of,

Madame Bodichon involuntarily ever acting upon a precept of Mahomet

in the Koran—"Bestow not upon the rich." The more opulent her

guests, the plainer was their fare.

But conviviality had no meaning for these two. The

dinner-table topic resolved itself into this problem: How and by

what means would the world—that is to say, the terrestrial globe we

inhabit—come to an end? By combustion, submergence, gradual

decay, and so on. I seem to hear George Eliot's penetrating,

pathetic voice:

"Yet, dear Barbara, might not this come about—" Or, "Suppose

that—"

For myself, I was silent, overawed as some alumnus when

Pericles and Aspasia held their court.

II.

Thenceforward I was invited to the famous Sunday afternoons

at the Priory, and I well remember George Eliot's kindly attempt to

set me at ease.

The entry into such a circle was no trifling ordeal to a

young country-bred, although already much-travelled, girl, and

already having several novels to her credit, the first of these now

celebrating its diamond jubilee. [p.42]

There in the centre of the room, as if enthroned, sat the

Diva; at her feet in a semicircle gathered philosophers, scientists,

men of letters, poets, artists—in fine, the leading spirits of the

great Victorian age. Frederic Harrison, almost the only one

left us of so memorable a group; Professor Beesly, Herbert Spencer,

Browning, William Morris, that charming poet and self-styled "singer

of an empty day"; Sir Frederick Leighton, Director of the National

Gallery; Philip Gilbert Hamerton, author of French and English and

cementer of Anglo-French friendship at a time when we seemed

perilously, if not hopelessly, Germanised, to our certain moral,

intellectual, and national abasement—these were only a few of the

noteworthy figures caught sight of as, timidly enough, I advanced to

the hostess.

Despite her grand aloofness from conventionalities and an

utter incapacity to overdo courtesy,—I will not use the word to

flatter,—George Eliot, never, that I ever heard of, hurt people's

feelings or pooh-poohed valueless admiration. She could not

have rebuked a naive worshipper with a Johnsonian, "Before you choke

me with your praises, Madam, remember what your praises are worth."

Not that I should have ventured upon so much as an allusion to the

masterpieces so dear and familiar, Adam Bede and the rest. And

seeing that she had nothing to fear from me on that score, as soon

as a break in the discussion permitted, she withdrew from the group

and chatted with me in the easiest, least bookish fashion possible.

Madame Bodichon had naturally told her of my farming days,

and that, having now lost my father and mother, I was entering upon

a literary life in London. Be this as it may, she immediately

began to talk of her own early life and of her father. Very

tender was her voice as she touched on the sacred theme, and so full

of tenderness were her large dark eyes that I quite understood Sir

Frederick Leighton's enthusiasm. For, our brief chat over, I

fell back, and taking the first vacant chair, it happened to be next

his. We were old acquaintances, had walked and talked in

Kensington Gardens, had set out in a bus for a Saturday Pop

together,—as the celebrated week-end concerts at St. James's Hall

were called,—and a most pleasant friend and neighbour he became.

On this Sunday afternoon he seemed oblivious of everything

around him, his eyes fixed on the priestess-like, rather Sybil-like

figure opposite. After a mechanically uttered phrase or two he

burst out—a lover's voice could hardly have been more impassioned:

"How beautiful she is!"

After all, was not the artist right? What is physical

perfection compared to spiritual beauty, the inner radiance that

transforms, etherialises features not flawless according to rule of

thumb? Meanwhile Mr. Lewes was doing everything to promote the

general pleasure—acting, indeed, a dual part, relieving the hostess

of all responsibility. Who could help comparing the pair to

Titania and Puck?—herself, queen-like, effortless, impassible; he,

anticipating her behests, here, there, and everywhere, taking care

that no guest should be neglected. Naturally, the German

element was never absent from these assemblages. Was not the

biographer of Goethe styled der Goetische Lewes by his

country-people, and had not homage been paid to both in the so

ironically called Fatherland? He now brought up a quiet,

gentlemanly-looking man, saying in German:

"I have the pleasure of introducing to you Herr Liebreich,

the discoverer of chloral." [p.44]

I had already spent many months at Stuttgart, as many at

Frankfort-on-the-Main, and had wintered in Vienna, so the question

of language was not disquieting. But a tête-à-tête with

a scientist did seem rather dreadful. My interlocutor,

however, tried to talk down to me, and I tried to talk up to him,

and soon the welcome clatter of cups and saucers relieved the

tension. There was a move towards the lower end of the room,

Mr. Lewes presiding at the teapot.

"To make tea, my friends," he said laughingly, "I hold is the

whole duty of man."

All now was comparative frivolity, gaiety, and persiflage;

mirth and music replaced Socratic discussion and talk worthy of

being Boswellised.

"We have a singing bird here," said Mr. Lewes. "She

must charm us before departure."

The fashionably dressed young lady in question, some Lady

Clara Vere de Vere, did not deny the delicate imputation, and true

enough, before the party broke up, those almost solemn precincts

were ringing with just such a song as might divert the guests of any

Belgravian drawing-room.

Belgravia, indeed, had forced an entrance into the Priory,

and, as we might expect, that intrusion was followed by an exodus.

More than one old friend and habitue, more than one distinguished

guest dropped off. The "gathering-place of souls" gradually

changed its character. Its doors had been thrown too wide, and

"fools rushed in where angels feared to tread." [p.46]

III.

But I was soon to see George Eliot in intellectual and social

undress, to enjoy her company for an entire week, perhaps the only

person now living retaining such a memory.

Madame Bodichon had rented a High Church vicarage in the Isle

of Wight for the winter of 1870-71, myself being her guest

throughout the period, and before Christmas she invited her great

friends to join us.

"Yes, dear Barbara," came a reply in the exquisitely neat

handwriting of one who could do nothing flimsily—"Yes, dear Barbara,

we will come and weep with you over the sorrows of France."

They duly arrived, and a memorable week it was to the

youngest of the quartet, doubtless her fellow-guests little

suspecting that there was "a chiel among ye takin' notes."

From the first Madame Bodichon monopolised Titania.

Puck had to put up with me, and from the first he gave us all a

taste of his quality. As we sat down to breakfast next

morning, the sedate, middle-aged parlour-maid was greeted by "A

merry Christmas to you, Ann, and a marrying New Year." Too

well-trained to giggle, and perhaps not displeased with the

suggestion, Ann blushed like a sixteen-year-old and just managed to

stammer out her thanks.

With dinner-time came another display of irrepressible

frolicsomeness. Soup being removed, Mr. Lewes rubbed his hands

with a well-affected Epicurean air.

"You will, I know, dear Barbara," he said, "excuse the

liberty taken by an old friend. I have ventured to add a

little delicacy to your bill of fare."

Well tutored, Ann now removed the silver cover with a

flourish, and as she did so the uninitiated three sprang back with a

cry. Lo and behold! Instead of a rare dainty, an uncanny

thing like a crayfish uncurled as if alive! It was the scourge

with which the rector flagellated himself, and which the temporary

occupant of his sanctum had laid hands upon for our diversion.

A week of glorious walks and talks followed.

Fortunately, the weather was fine, and every day, most often between

lunch and tea, we paired off for long strolls, in what Swift would

have described as a "walkable" country. Sometimes we made

little excursions, and of one I retain a pathetic remembrance.

At a village station I met a pleasant novelist, to-day, I fear,

quite forgotten—by name, Georgiana M. Craik. Now I had been

cautioned by no means to disclose the name of Madame Bodichon's

visitors to chance-met acquaintances. But my conscience did

afterwards reproach me for not having whispered in this one's ear,

as the others sauntered up and down, "That lady in black is no other

than the author of Adam Bede."

Could persuasion, however, could anything have prevented the

other from metaphorically falling on her knees before the Diva?

I should very likely have brought about mortification and got myself

into a terrible scrape. George Eliot was in her zenith, the

gentle little author of Riverston and other tales had hardly popped

her head above the horizon.

During our walks Madame Bodichon would carry George Eliot in

one direction, Mr. Lewes and myself taking another. He

generally talked the whole time of "Polly." It delighted him

to discover in me a whole-hearted admirer of Felix Holt, a

work generally less admired than their great brethren. How he

laughed when I quoted that denunciation of his sex by Mrs. Transom's

maid: "creatures who stand straddling and gossiping in the rain."

But the crowning hour of the day came when dinner was over,

lamps were shaded, and we gathered round the fire. No

recreations were in request; whist, chess, backgammon, billiards,

would here have been the extreme of boredom. High talk mingled

with lighter topics have left golden memories.

And may I be excused for mentioning a proud remembrance?

On two occasions the shy country girl was listened to by the great.

Once all three heard me with profound interest, and once I gave them

the merriest moment of that especial symposium.

It happened that a Socialist friend, Mr. Cowell-Stepney by

name, had lately escorted me to a sitting of the International,

presided over by Dr. Karl Marx, the founder of International

Socialism, who more than any other man has influenced the Labour

movement throughout the civilised world. Now this sort of

experience was quite out of Mr. and Mrs. Lewes's way. Their

world was the world of the intellectual élite, not of "the man in

the street," the hewers of wood and drawers of water. So to

the least little particular I could give, all paid the utmost

attention.

I must not forget that during these evenings we sometimes

enjoyed a musical treat. George Eliot would sit down to the

piano and very correctly, perhaps somewhat too painstakingly, give

us a sonata of Beethoven from notes. The charm of the

performance was that it was done amiably and evidently in order to

give us pleasure.

"What shall it be, dear little boy?" she would ask, as she

turned over the contents of the music-wagon, and the "dear little

boy"—I love to hear these terms of endearment among the

great—generally demanded Beethoven. One sonata she played to

us was Op. 14, No. 2, containing the slow, plaintive Andante in A

minor, ever one of my favourites.

For light holiday reading the wonderful pair had brought

surely the strangest book in the world—namely, Wolf's Prolegomena,

which, however, had one advantage. It did not touch upon the

tragedy of the time. In this work the most gifted scholar and

first critic of his age (1729-1824) unfolded with equal erudition

and acuteness his bold theory that the Odyssey and Iliad

are composed of numerous ballads by different minstrels, strung

together in a kind of unity by subsequent editors.

As I have mentioned, our rectory adjoined the church, and on

Christmas morning, and in arctic weather, Madame Bodichon carried

her friend off to hear the fine musical service—Mass would be the

proper appellation.

George Eliot listened with subdued rapture, the clear shrill

voices of the choir, the swell of the organ evidently evoking a

religious mood nonetheless fervent because unallied with formulary

and outward observance.

The midnight service had been proposed, but—

"No, dear; on no account would I keep George up for me so

late," said the great visitor, unlike her hostess in one respect,

indeed in many. Whilst Madame Bodichon could never have half

enough of anything she loved, whether good company, aesthetic

impression, or strawberries and cream—her abnormal energy craving

more and yet more expansion—George Eliot's nature needed repose.

She did not, in French phrase, chercher des émotions.

But why, oh! why did I neglect the seven days' wonderful

opportunity? With the unwisdom and self-assurance of youth, I

neglected notebook and tablets. It never occurred to me to set

down the high talk of that Ventnor drawing-room. Instead of

binding them into a sheaf, I let the golden ears fall to the ground.

Here are one or two, the topic being literary excellence and

fame—perhaps I should rather say, recognition and the criterion of

both.

"There is the money test," George Eliot said, and paused, as

she often did before continuing a train of thought. [Would she

have uttered that sentence nowadays, when novels reaching fabulous

prices are clean forgotten before copies have become soiled in

Mudie's?]

Her next sentence even less commends itself to all lovers of

literature:

"Then there is the test of sincerity."

A canon not unassailable either. For of course the

only, the final, test of literature, whether grave or gay, is

duration, the ineffaceable seal of Time. Was ever any book

written with greater sincerity, for instance, than the Proverbial

Philosophy of Martin F. Tupper?—a book that enriched the author

and was for a time taken seriously. Who reads poor dear Martin

Tupper's twaddle-dum-dee nowadays?

If George Eliot, naturally enough, held aloof from literary

aspirants, Mr. Lewes never lost an occasion of helping them.

When the great week came to an end he said to me:

"Now you will, I am sure, like your new novel to appear in

the Tauchnitz edition. I will write to the Baron, and as you

say you are going to Germany in the spring, I will ask him to call

upon you. On arriving at Leipzig, you have only to send him

your card."

The German visit was carried out, and to Mr. Lewes I owed not

only the satisfaction and profit of having all my books

thenceforward published in the famous Continental series, but the

warm friendship and hospitalities of the first Baron and the second,

his son.

IV.

Yet a few words more about one of the greatest figures in our

national Valhalla, and one whose fame, if she ever troubled herself

about fame, has surpassed any author's wildest dreams. I am

sorry that she died half a century before she had an enthusiastic

following in Japan. I can fancy Mr. Lewes's exuberance over

the triumph, his "Well, Polly, after that I shall never venture an

opinion of your books, that is quite certain." Or, "Now,

Polly, see if a Chinese translation of Adam Bede won't be the

next pleasant surprise." It was really beautiful, this

absolute comprehension of a larger intellect and character by a

lesser and less stable.

A more agreeable walking companion could not be, but I

sometimes wished that we had not invariably paired off. There

were, however, excellent reasons for this arrangement.

Although not admitted to the confidential tête-à-tête of our

hostess and her visitor, I well knew what grave subjects would be

discussed by them.

The foundress of Girton College and the indefatigable pioneer

of legal reforms regarding women had one subject even nearer her

heart than even the educational, material, and social elevation of

her sex. Madame Bodichon entertained a passionate pity for her

pariah sister, a horror of conditions accepted, not to say in a

civilised but also in a Christian country. Had she lived

longer, she would have joyfully welcomed a growing repulsion in

France and a spirit of revolt against the system which, in plain

words and excused on behalf of the public health, legalises and

supervises prostitution.

If righteous indignation characterised the doer, the woman of

action, I should call sensitiveness the other's leading quality.

I firmly believe that had George Eliot convicted herself of

inflicting a grave injury on any living soul, remorse would have

worn her out, killed her by inches. Her super-sensitiveness in

little things was painful to witness. Here is an instance.

During the week I was obliged to call in a surgeon, and have

a finger lanced on account of a painful gathering. Next

morning, in shaking hands by the breakfast table, she pressed, or

rather fancied she pressed, the injured part.

"Oh!" she said, with a look of positive anguish, "I have hurt

the poor finger. I am always doing this sort of thing."

And it was with difficulty that I could reassure her.

An instance of such sensitiveness was told me by Mrs.

Hamerton, who in her husband's lifetime had occasionally attended

the Sunday afternoon receptions. On her reappearance after a

year or two's absence, George Eliot asked news of her family and

friends.

"No gaps?" she said, with quite affectionate solicitude.

Again, when the widow of Arthur Hugh Clough, the poet of the

Bothie of Tober-na-Vuolich and the subject of Matthew

Arnold's fine elegy Thyrsis, called one Sunday with his

little son, the hostess's first question was a pathetic, "What is

his name?" She always liked to call children by their names,

she added.

There is a suavity in sovereign natures. These alone

can discern the infinitely fine shades dividing simplicity from

annoyance, real from affected admiration. As a subtle writer

of the last century has admirably written: "It is a rare perfection

of the intellectual and moral faculties which allows all objects,

great and small, to be distinctly perceived, and perceived in their

relative magnitudes." George Eliot was "a soul of the high

finish" of which Isaac Taylor wrote. Here is an instance.

After that Christmas week I returned to 5 Blandford Square,

and had a very severe bronchial attack. So serious was my

condition that on partial recovery I was summarily ordered a

Mediterranean cruise, and with a friend sailed from Portsmouth to

Gibraltar, thence to Malta and Alexandria, thence to Athens, and

from Athens to Venice.

On my return in March I ran up from Hastings, my abode from

that period to this, to London. On the way to Madame

Bodichon's I called at the Priory, leaving with my card a bunch of

violets, one of the cream cheeses formerly a Hastings speciality,

also some pats of butter, golden of the golden, creamiest of the

cream. The unsophisticated, perhaps to ordinary folks

impertinent, attention was charmingly acknowledged on the following

Sunday afternoon. Taking both my bands when I entered with my

hostess, George Eliot said, with congratulations on my recovered

health and a smile:

"So, having recovered yourself, you are bent upon fattening

your friends?"

Little traits of quite other kind will, I am sure, be

welcome.

The two great friends would sometimes stroll along the

streets together and look at the shops like other womenkind.

One morning as they sauntered down Bond Street, pausing

before each glittering display, George Eliot said: "How happy are we

both, dear Barbara, that we want nothing we see here!"

One point struck me. The Priory knew no pets. So

intellectually and humanly full were the lives of both master and

mistress that there was no room for cat, dog, bird, or goldfish.

Children, as has been mentioned, were occasionally admitted into the

learnèd precincts, but no live playthings. Did ever a dog wag

its tail and therein ask a caress from hosts or guests? I know

not.

Nor except at the door was anything seen or heard of Grace

and Amelia, the two faithful middle-aged maids, who, as far as I

ever learned, knew nothing of their great lady's writings except

that they had made her famous. To the perpetual disappointment

of the worthy couple, Queen Victoria never drew up to the door, no

royal visit filled their cup to overflowing. Grace and Amelia

little dreamed that their own names would live in the book of fame!

Such is the irony of life.

V.

To criticise the world's classics is to find fault with the

Pyramids for not being round, with Shakespeare for not having been a

novel-writer, with Victor Hugo for not having laid the scene of

Notre-Dame between 1789-94, and made Madame Roland his hero instead

of Esmeralda, and so on and so on. How futile, indeed, is all

criticism of the Immortals; how puerile are quibbling and cavilling

at leading spirits, "whose names are written on the book of Time."

One or two noteworthy estimates only of George Eliot, her

life-work and character, I give here. A great Victorian, one

of the greatest, who knew her well, and who is happily yet among us,

has said, "George Eliot was greater than her works." But must

not this be affirmed of creators in any field? Is not the

master ever greater than his masterpiece? Do we adore a

chef-d'œuvre in the same frame of mind as we adore a beautiful

landscape or sunset? The individual gift, the aspiration and

achievement, cannot be ignored by the least reflective.

Again, it is often urged that fame, adulation, and

intercourse with the most brilliant wits, geniuses, and most

renowned thinkers of her time were in her case a loss rather than a

gain. The idyllic charm, the raciness and spontaneity of

Scenes of Clerical Life, Adam Bede, and perhaps of The

Mill on the Floss, gradually gave way to a more laboured style

and a more introspective psychology. Romola—a midway

production—is an historical novel worthy of comparison with Bulwer

Lytton's ever-delightful Last Days of Pompeii, but Daniel

Deronda, 1876, if not a dead-weight on her reputation, as was

Count Robert of Paris on the great Sir Walter's, showed, as a

judicial critic wrote, [p.58]

"a marked falling-off in power, though many of the scenes are

sufficiently rich in pathos, humour, and insight."

In confirmation of my remark, another friend to whom, as to

Barbara Bodichon, she was "Marian" always, herself a wife and

mother, and by no means a commonplace writer—Madame Parkes-Belloc,

wrote:

"The truth is, dear Milly, after her early years, and

especially after her installation as mistress of the Priory, she saw

very little of life—that is, of family life."

How could it have been otherwise? What room was there

in that Parnassian retreat for noisy bantlings? But George

Eliot had known childhood in earlier years. She was not

obliged, like Herbert Spencer, to borrow a friend's child or two in

order to study the workings and development of the human mind.

Although there were neither pets, human nor four-footed, nor

games at the Priory, it was by no means a case of all work and no

play. The founder of synthetic philosophy must be referred to

on this head. The two ponderous volumes Herbert Spencer has

devoted to his own life abound in references to his friend, hostess,

and lawn-tennis partner!

It is not surprising to find that one of George Eliot's

characteristics was diffidence of her own powers, and the

philosopher found it no easy matter in early days to persuade her

that she possessed all the gifts of a novel-writer. So

sensitive was she regarding her own gifts, even after recognition,

that Mr. Lewes used to put into a special drawer such reviews as

were encouraging only. Onslaughts and animadversions were

rigidly excluded. And did not Mr. Lewes once write to Spencer,

"Marian is in the next room crying over the distresses of her young

people."

Here is a witticism at the expense of a certain Dr. A— who

was remarkable for his tendency to dissent from whatever opinion

another uttered. After a conversation in which he had

repeatedly displayed this tendency, she said to him:

"Dr. A—, how is it that you always take your colour from your

company?" "I take my colour from my company?" he exclaimed.

"What do you mean?" "Yes," she replied, "the opposite colour."

Here is another delightful story, but not referring to the

great novelist. Spencer used to attend the first Wagner

concerts at the Albert Hall with friends. One day he relates:

"As we came downstairs the lady of the party was accosted by an

acquaintance with the question, 'Well, how did you like it?' to

which her reply was, 'Oh, I bore it pretty well,' a reply which went

far to express my own feelings."

How seriously, one might almost say how sacred, George Eliot

regarded her calling the following story will show.

Her great friend Barbara, handsome, rich, spirited, generous,

was one of those fortunate individuals who could never for an

instant imagine herself an intruder, never conceive it possible that

she should be in anybody's way, least of all in the way of those who

loved her. One morning, with happy unconcern, she rang the

Priory bell half an hour before lunch, and was admitted and

announced. Tender-heartedness itself, the novelist rushed out

of her study, pale, trembling, agitated, her remonstrant "Oh,

Barbara!" even more poignant than could have been Sir Isaac Newton's

"Oh, Diamond, Diamond, thou little knowest the mischief thou hast

done!" And quite certainly Diamond did not droop his ears, wag

his tail, and with his eyes plead for forgiveness so pathetically

as, ready to cry, poor Madame Bodichon murmured excuses then.

Ever on the alert where Polly's quietude and comfort were

concerned, straightway Mr. Lewes emerged from his study and, as the

culprit related, coaxed and soothed her as if she had been a child.

This, I believe, is the single occasion on which the close

friendship of these two noble and contrasted women was for a moment

clouded.

Contrasted they were physically and intellectually.

Barbara Bodichon, née Leigh Smith, was everything that George Eliot

was not. If the rare lot of supernumerary gifts ever fell to

any woman, that one was the foundress of Girton College. Not

that she was an Admirable Crichton in petticoats. Although

half her life was spent in France and she married a Frenchman, she

never mastered French grammar or idiom. To the last she would

speak of à ma maison instead of chez moi. She

could no more spell her own language than could Queen Elizabeth.

Although very fond of music, she never acquired sufficient facility

to play the simplest of Haydn's easy sonatas. Except, indeed,

as a delightful artist in water-colours, and in that field regarded

as an amateur, she might be described as the most unaccomplished

member of a highly distinguished milieu.

But she was destined to live among the great, and what in

ordinary cases would have proved a disastrous upbringing developed

her remarkable endowments of heart, wit, and brain. Thus was

exemplified Selden's famous saying: "Wit and wisdom are born with a

man." So suited to her was her early education—in a certain

sense, we may say, lack of it—that when twelve years old everything

she said was worth listening to; without an approach to

precociousness, she talked well. Later, alike in English and

in French, despite utter disregard of grammar and syntax, she was a

brilliant and suggestive talker. I have heard Frenchmen extol

her conversational powers, so full was it of wit, acuteness, and

originality.

And if she failed in perhaps the one personal object nearest

her heart, if she is still regarded as an amateur by connoisseurs

and the art-world generally, she has achieved a rare and enviable

reputation. What indeed do not two generations of

English-speaking women already owe her in the matter of education,

and to-day what do not her sex owe her? To be one of the

first, most intrepid, and most liberal advocates of parliamentary

equality, at last has come posthumous triumph. Let us hope

that the newly enfranchised will prove themselves worthy of the

privilege!

To Mr. and Mrs. Lewes came years of almost seclusion,

fabulous prosperity, alike intellectual and material, but the

ambition of Grace and Amelia was not fulfilled. No royal

honours were showered upon the greatest novelist of the age by the

sovereign characterised as "sour and unattractive" by another

"illustrious Victorian." [p63-1]

No Order of Merit for women was likely to be instituted by a queen

who said that suffragettes ought to be whipt. [p.63-2]

But George Eliot held the reading world in fee. I have heard

on excellent authority that Romola brought her a cheque for

£8000 down. And good fortune was wisely made the best of by

both. A pretty country house was purchased at Witley in

Sussex, drives in their own carriage replaced the long walks of

earlier days, Mrs. Lewes saying to her friend Barbara, who visited

them in their new home:

"Of course you did not acknowledge us till we kept a

carriage."

She could jest then, but the days of playfulness were short.

Their holiday had come too late for overworked brains and physiques

of hardly normal robustness.

Mr. Lewes died in 1878, and on the morning of May 6, 1880,

Madame Bodichon received a note from her great friend saying that

she was to be married that day to Mr. J. W. Cross. I cannot do

better that cite the following passage from Chambers's

Encyclopædia, written by R. Holt Hutton:

"After the death of Mr. Lewes,

George Eliot, who was always exceedingly dependent upon some one

person for affection and support, fell into a very melancholy state,

from which she was rescued by the solicitous kindness and attention

of Mr. John Cross, an old friend of her own and of Mr. Lewes's, and

to him she was married on the 6th of May 1880. Their married

life lasted but a few months. George Eliot died in Cheyne

Walk, Chelsea, on the 22nd of December of the same year, and is

buried in Highgate Cemetery in the grave next to that of Mr. Lewes."

Madame Bodichon outlived her by eleven years, but thrice

happier for her had it been otherwise.

Always endeavouring to crowd the activities and achievements

of a dozen lives into one, both bodily and mental powers gave way

under the strain. Restfulness she never knew, and the close of

a noble and fruitful life was of sad helplessness and invalidism.

The crowning monument to her memory is her College of Girton.

Mr. Cross's biography of George Eliot is a classic, but it

must not be forgotten that he is a noteworthy Dante scholar. [p.65]

We have read how among her last literary recreations were Dante

studies under his guidance, and we can understand how she would glow

over the lines:

|

"Light intellectual replete with love,

Love of true good replete with ecstasy,

Ecstasy that transcendeth every sweetness." |

How satisfactory the reflection that the biographer was in

every respect worthy of his subject, as he had been of the love and

confidence called forth by his devotion.

Let me in conclusion allude, not to the creator of Hetty

Sorrel or Silas Marner, of Mr. Casaubon, Dorothea, and Celia, but to

the deep thinker on grave problems. Is not genius prescient

always, the poet ever a seer, the "greatly dreaming" man or woman

ever a prophet?

During one of those long talks in the Isle of Wight,

1870-1871, the subject of Governments came up.

"A time will of course come, dear Barbara," said George

Eliot, in her slowly enunciated, thoughtful way, "when royalties

will disappear" (I believe the word "caste" was used also, but am

not sure). "Kings and queens will be pensioned off, with

cushions for their feet."

Are we not much nearer this period than we think? Are

not all thrones tottering, Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns trembling

before Time and his hour-glass, inherited privileges, unearned

prerogatives doomed to speedy and eternal disappearance? Let

us hope so.

I add a note from Mr. Cross:

QUEEN ANNE'S

MANSIONS,

ST. JAMES'S

PARK, S.W.,

July 6, 1908.

DEAR MISS

BETHAM-EDWARDS,—Many

thanks for your note, which has been forwarded to me here. At

this time of the year I am always more in London than in Tunbridge

Wells. It is indeed long since I have had the pleasure of

seeing you, and I had never heard that you had been laid up.

But I am very glad to hear that you are now fairly well again.

I should very much enjoy coming over one afternoon for a chat, and I

will try if I can manage it; but I am going away shortly to

Switzerland, and my time is very much occupied in the meanwhile.

However, if I can't get to Hastings before going abroad, I will

certainly come over when I return, as I should like to see you again

and exchange views with you.—Yours very sincerely,

J. W. CROSS.

Here is the only letter I ever received from George Eliot,

and a charming one it is; her exquisite handwriting in itself a

lesson to us all, scribblers that we are!

THE PRIORY,

21 NORTH BANK,

REGENT'S

PARK, January 5,

1872.

MY DEAR

MISS EDWARDS,—We

have been to Weybridge for a few days, and I did not succeed in

finding a few minutes to thank you for your letter on Monday morning

before we set out.

Any sign of remembrance from you will always be welcome, even

without such sweet and encouraging words as you wrote about what I

have done.

I am rather a wretch just now, apt to be more conscious of a

disordered liver than of all the better things in the world. I

hope you are freer than you were from such bodily drawbacks.

Madame Belloc assured me that you were, and that you looked

unusually strong.

Mr. Lewes and I often revive the memory of you with pleasure

(it is about the anniversary of our acquaintance with you); he

unites his wishes with mine that the year may bring you new

blessings.—

Always yours sincerely,

M. E. LEWES.

Yet a postscript more about the foundress of Girton College

and George Eliot's most intimate friend.

Long ago Madame Bodichon's writings ought to have been

collected, edited, and published by some grateful beneficiary of her

foundation. Not a bit of it! As I have before said, and

I reaffirm it now, the disloyalty, ingratitude, and jealousy of

women towards each other is flagrant and will ever with me remain an

unanswerable objection to women's political advancement.

Here is a list of these terse, lucid, admirably-written

expositions, in so far as I know not one having been reprinted.

Most likely Girtonians have never heard of them, and if so, would

very likely shake their heads over "poor, second-rate stuff."

See "On the Girl of the Period," Mr. Frederic Harrison,

Fortnightly Review, February 1918, true as the satire is biting.

(i) A brief Summary in plain language of the most important Laws

of England concerning Women, together with a few observations

thereon, by Barbara L. S. Bodichon. Third edition with

additions. Trubner & Co. London, 1869. Price 1s.

(ii) Reasons for and against the Enfranchisement of Women, by

Mrs. Bodichon. Spottiswoode & Co. London, 1869.

(iii) Illustrations of the Operation of our Laws as they affect

the Property, Earnings, and Maintenance of Married Women.

Edinburgh, 1867. Price 1d.

(No name given, but undoubtedly the work of Madame Bodichon. A

marginal note points to a knowledge of French law, unlikely to be

possessed by an Englishwoman.)

A generation earlier, wrote Herbert Spencer (Autobiography,

p.149), a conspicuous part had been played in public life by Madame

Bodichon's father [p.69], Mr.

William Smith, for many years Member of Parliament for Norwich. His

were times during which immense sums were lost over contested

elections, and he is said to have spent three fortunes in this way:

not for the gratification of personal ambition, but prompted by

patriotic motives. For, himself a Unitarian, he was the

leading representative of the much-oppressed Dissenters, and it was

he who, by untiring efforts, finally succeeded in obtaining the

abolition of the Test and Corporation Acts. Various of his

descendants have been conspicuous for their public spirit,

philanthropic feeling, and cultivated tastes. From the eldest

son, his father's successor in Parliament, descended Mr. Benjamin

Leigh Smith, whose achievements as an Arctic explorer are well

known, and Madame Bodichon, of note as an amateur artist and active

in good works. One of the daughters became Mrs. Nightingale of

Lea Hurst, and from her, besides Lady Verney, came Miss Florence

Nightingale.

Among the younger sons was Mr. Octavius Smith, who might be

instanced in proof of the truth—very general but not without

exception—that originality is antagonistic to receptivity. For

having in early life been somewhat recalcitrant under the ordinary

educational drill, he was in later life distinguished not only by

independence of thought, but by marked inventiveness—a trait which

stood him in great stead in the competition which, as the proprietor

of the largest distillery in England, he carried on with certain

Scotch rivals. Energetic in a high degree, and having the

courage and sanguineness which comes from continued success, he was

full of enterprises, sundry of them for public benefit. Partly

because of the personal experiences he had in various directions of

the obstacles which governmental interferences put in the way of

improvement, and partly as a consequence of the fact that, being a

man of vigour and resource, he was not prone to look for that aid

from State agencies which is naturally invoked by incapables, he was

averse to the meddling policy, much meddling in favour then, and

still more in favour now. One leading purpose of Social

Statics being that of setting forth both the iniquity and the

mischief of this policy, a lady who knew Mr. Octavius Smith's views

planned an introduction; and this having been made, there was

initiated an acquaintanceship which afterwards grew into something

more.

I have been very fortunate in my friendships, and not the

least so in that with Mr. Octavius Smith. In later years I

owed to him the larger part of my chief pleasures in life.

The Member for Norwich was an original, and evidently loved

to contravene social mandates, taking his little daughters out for

drives on Sunday in their ordinary frocks and pinafores, and

otherwise throwing the gauntlet at public opinion—even objecting to

the shibboleth, as he regarded it, of baptism.

How proud would he have been had he lived to see the fruition

of his efforts! How he would have gloried in Barbara's name

and fame! It was not to be. But there is fortunately a

prescience in the parental mind. Doubtless as the old man lay

dying with the map of Algeria on his pillow, reminder of that

beloved child long since lost to him in a double sense—by a French

marriage and by a thousand miles of sea—he felt that she would do

more and more credit to his name as the years wore on, and that

without vain gloriousness he could here take credit to himself.

Here are a few samples of Madame Bodichon's wit, humour, and

repartee.

On high thought and small snobberies:

"I lunched the other day at the Deanery (with Dean and Lady Augusta

Stanley) to meet Mr. Gladstone. There was served a cut

gooseberry pie. That pie doing double duty is a standing

lesson to my housekeeper, and now she has to bring to table pies

that have been begun."

On other snobberies:

"My leg-of-mutton dinners, as I call them, I began in Algeria.

Whenever rich people dined with me, I gave them just anything.

When poorly paid French functionaries were invited, I always

provided a sumptuous repast."

(In London the leg-of-mutton dinners were also the rule, and not,

perhaps, always accepted with a good grace. When the table was

set the hostess would also go round with a bottle of water, and well

dilute the half-filled decanters of sherry and claret.)

Madame Bodichon had a rough-and-ready way of treating

practical details. When travelling with her in Spain, she

found me puzzling over pesetas, doubloons, and the rest.

"Why trouble your little head about Spanish money?" she said,