|

[Previous

Page]

WALKS AMONGST

THE WORKERS

No. VI.

TONGE AND CHADDERTON.

WORK FOR THE SCHOOLMASTER AND THE MISSIONARY.

IN the lower, or southern part of the township of

Tonge, the extensive silk and cotton dye works of Mr. Walter Beattie, are

situated; near them is the newly erected mill for the manufacture of silk smallwares and ribbons, belonging to Messrs. Royle and Jackson; a little

to the north, at a place called "The Lodge," Mr. Gill has a compact and

well adapted concern for spinning and weaving cottons; at Spring Vale, a

short distance from this, is the malting concern, and the brewery of ale

and porter, belonging to Mr. Anson; and, at "The Old Engine," near the

railway station, is the colliery of Messrs. Whitehead and Andrew; with

these exceptions, and a few others, such as farmers and their labourers,

bricksetters, joiners, blacksmiths,

and other individuals, all the population is employed in hand-loom

weaving, either of silk or cotton.

Of the silk weavers it would scarcely be fair to draw a general inference

from their present condition, as to employment. After a long season of

full work, at steady wages, the silk weavers, like many other operatives,

experienced, at the latter end of autumn, a sudden check in the stoppage

of many of their looms. From the latter end of October to the beginning of

February, in each year, there has generally been a greater or less want of

employment amongst the weavers; this year it is more decided and of

greater extent, and the distress among the poor is correspondingly

increased, but there is nothing in the present state of employment which

should lead us to suppose that it is anything more than one of those

periodical depressions, caused by the annual pause in the market, which is

affected by the seasons, and is, consequently, in a degree beyond the

influence of human arrangement. In former years it has not been unusual

for one-fourth or two-fifths of the weavers to be waiting for work, in the

month of December; at present we shall probably be near the mark, if we

say that three-fifths are waiting, or are under a tie not to bring their

work in within less time than six weeks, which is equivalent to waiting

one half their time. As to the average earnings in such a state of things,

it cannot with reason be guessed at, nor is it required in the endeavour

to approach fair general conclusions. In the

best of times, there are here, as at other places, individuals and

families who are "distressed"—who never were, nor ever will be, in any

state, save the "distressed one." Others there are who are really

distressed, but never make a song of it—who keep it to themselves, and,

like good men and women, good fathers and mothers, meet hunger at their

threshold, and, without whine or outcry, endeavour to repel it with all

their energy. This is done every year by scores of individual families,

and the world never hears of it; nor is it known beyond their own hearths,

or, mayhap, those of some humane neighbours, not quite so poor as

themselves. These sort of people have not leisure to go round talking of

their "distress," nor would their pride let them. They are

the sort that should be looked after by the ministers of religion, by the

rich and beneficent, by the overseers of the poor; they should be rescued—they

should be sought out, and

comforted. I am sorry to have to express a belief that, at this particular

time, there are amongst the working population of the above townships, and

their neighbours also, many decent and really respectable families, who

are struggling hard, and sinking daily—where the children become paler

and thinner, and the parents more naked, stripping their apparel for a

scanty dish of food; but this description cannot as yet, by any means, be

applied to the bulk of the people. Their case is certainly bad; but it is

not like that of the operatives of Stockport and Bolton, worse after

being a long time bad—not like a battle to be begun when the breath is

already expended—a race maintained when it should have been terminated—a

night continued when morning should have dawned. The depression here has

come at the usual season, and though, as I have said, sudden and more

extensive than in ordinary times, the good run of work which prevailed

during spring, summer, and part of autumn, will, it may be hoped, enable

the weavers to bear up until the trade of the new year shall put them

again on their looms, with plenty of employment, good wages, and steady

payments.

I know that I shall be blamed by some of the operatives for admitting thus

far—for giving anything short of a picture of total distress. Exactly

as, according to information, I was blamed at Heywood, for saying the

workpeople were decently clad, and the children were cleanly and good

looking; and as some persons at Royton condemned me because I had said the

habitations of the factory hands at Crompton were kept in a cleanly and

respectable condition. But the approval or condemnation of these

persons, or, indeed, of any persons, unless well founded, cannot be

suffered to interfere with a statement intended to express simply the truth, without

reference either to individual likings, or the struggles of parties.

Of the mental condition of the population of Tonge, Chadderton, and their

districts, some opinion may be formed after the recital of circumstances

arising out of

a late melancholy accident accident, (as is to be feared). From its

perusal the christian may be urged to promote the spread of a wiser and a

better light; the learnèd may trace the living follies in which his

forefathers believed; the mere reader may be amused, and the narrator of christmas tales may have a subject for the fire-side group; and in any

case we may learn how much remains undone towards the common-sense

instruction, and the reclamation from error, of our own "benighted

ones;" of the children, as it were, of our very households.

On the night of Sunday, the twelfth instant, Archibald Hilton, a decent,

elderly man, sixty -one years of age, after attending as waiter to the

company at the funeral of one of his early comrades, left the public house

at Lower Tonge, where the funeral had been held, to go home to the hamlet

of Jumbo, a distance of about a mile and a half from the public house. It

was about ten o'clock at night, pitch dark, rather stormy, and as there

had been a fall of rain that afternoon, the brooks and waters were

considerably swollen. Hilton's direct road, however, did not lie across

any water, but for a distance, not far from the edge of a stream called

Wink's-brook, dividing the townships of Alkrington and Tonge, which brook,

like all the others, was, at the time, swollen by the afternoon's rain. He

was observed to be rather touched with liquor as he went out of the public

house, and a person offered to accompany him part of the road, but

he said he could do without assistance, and he went out, turning, as was

supposed, in the right direction towards home, and from that time to the

present day, (Wednesday, December 29th, 1841,) he has not been seen or

heard of. He wore a black hat, a blue cloth coat, a checked cotton

handkerchief round his neck, velveteen olive-coloured small clothes,

strong shoes, had a tooth out in front of the upper jaw, and carried in

his hand a blue cotton umbrella. For days all the brooks and waters, and

pits, and every place where it was conceived he could possibly be

concealed, were searched. His up-grown children and his neighbours, (he

had no wife) were out late and early, making enquiries, and dragging and

grappling for his body, and as the sons were one day engaged in the latter

duty, one of their wives, attended by some neighbour women, came and

proposed that "a cunning woman," living in one of the stone huts, near Collyhurst bridge, should be visited and consulted respecting the fate of

the lost man, and the place where, if dead, the body might be found. The

husband made light of the proposal, but one said the cunning woman had

told one thing truly, another mentioned another proof of her wonderful

knowledge, and they all set off to the house of the cunning woman, at Collyhurst bridge. Nine or ten persons were in the house when our

inquirers arrived; and, after waiting three hours, the daughter-in-law of

the missing man was admitted to the presence of the prophetess. "What was

her name?" demanded the

sybil [ED.—The first oracle at Delphi was commonly known as

Sybil, though her name was

Herophile. She sang her

predictions, which she received from Gaia]. "Betty Hilton," replied the woman. "Was she christened Betty or

Elizabeth?" asked the sybil.

"Betty," was the reply. "Well," said the sybil, looking at a round

glass, "you're come about a very decent, quiet old man, sixty-one years

of age, and you're in great trouble about him, I see ." "I am," said the

woman. "But what's the meaning of this funeral?"

said the sybil—"and him following after it?" Betty told her about the

funeral the old man had been at, and that he was an intimate friend of the

person buried. "What's the meaning," said the sybil, "of him going home?—I see him, and he turns down a narrow lane, and towards a water; and now

a cloud comes over all, and I can see no more." "Was it a running water

or a still water?" asked Betty, in the utmost simplicity. The witch said

she could not tell, for the cloud prevented her seeing; it betokened

death, and the man would never be found alive. She also said Betty must

come over again; meantime she would "set a sign for him," and would

"endeavour to trace him," and if they found him they must come or send her

word as soon as it took place. They found him not; and the daughter-in-law

went again, and the sybil then said she had endeavoured to trace him, and

he was in water, not far from a white or light-coloured house, a cindered

road, a dung heap, and a cart, with the shafts thrown up; those were signs

as to the place where they would find the body. All these "signs" they

found upon, or near the premises of Mr. Dudson, at Rhodes, and close to

the bank of the river Irk, of which Wink's-brook is a branch. They

searched above and below, as well as at the place, several days, but

neither the body of the missing man, nor anything appertaining to it, had

they found at the above date. Other conjurors have also been visited

by the relatives and friendly neighbours of Hilton. He was much

respected, and a very general interest has been felt on his behalf; and

some friends, who went to a "ruler of the stars," in Lord-street, Oldham,

were informed by that adept, that the man was killed, either by a fall or

a blow; that he lay in a hollow place where there were many stones, and

that if he was in water, it must have come to the place and washed him

away—he could not go to it, for, "there was no water planet ruling that

day."

Numbers of the poor man's friends and acquaintances have

sought the advice of one of these "Seers," who resides in Burnley-lane,

near Oldham, which neighbourhood is rife with them, there being not fewer

than seven in that vicinity. This man told a different tale from the

others, and such was his plausibility and confidence, or assumed

confidence in his predictions, that he was invited to the house where the

family of the lost man resided. He went, and there was a very

general examination and trial of his wonderful glass. A room was set

apart for him up stairs; it was darkened from the outer light, and a

table, a chair or two, and a burning candle, were placed for him.

When a person went in, which they did one at a time; he read a kind of

incantation, calling on the heavenly spirits to lend aid and assistance in

discovering the body of Archibald Hilton, who, to the great distress of

certain relatives, &c., was lost. The person then looked through a

pear-shaped glass; he was to look with a very steady gaze, and if, after

some time, he did not see anything, the angels, Michael, Gabriel, and

Raphael were invoked; and if the person still did not see anything, our

Saviour, Jesus Christ, was called on to lend assistance;—the wizard would,

at this last stage, place his hand on the neck of the gazer, who by this

time would hardly fail to notice a black speck or specks, which seemed to

be floating in the glass. When he announced these, he was directed

to look more intensely, and after some time they would begin to enlarge,

and probably assume something like the shape of a human being. These were

pronounced to be the lost man, and the head stocks at Alkrington colliery,

near to which place the conjurer declared the body to be lying. He even

said the body would be found by eleven o'clock on a certain day, wisely

adding, "or if not on that day, it would be found in nine days after."

The body was afterwards found in the river Irk, below the

works of Messrs. Schwabe, at Rhodes, near Middleton.

AN INSANE GENIUS.

JOHN COLLIER, commonly called

Jacky Collier, one of the sons of Tim Bobbin, became insane, and died at

Milnrow, near Rochdale, after having been for years an object of much

interest and commisseration to all who knew him. His appearance was

most striking, as he wore all his clothes the inside out, or the wrong

side before. He was tall and bony in person; very grave in manner,

and reserved in speech, and he generally carried a large stick, so that to

persons who did not know him, he was as much an object of alarm as of

attention. His coat buttoned behind, gave him a grotesque

appearance, but the scowl of his eye, especially when annoyed, was

sufficient to check all disposition to mirth at his expense. He

seldom spoke, even in reply to questions; and, being harmless, except when

exasperated by being interfered with, he was generally allowed to have his

own way, and he led a silent life, wandering about the neighbourhood,

entering such houses as he chose, and, when hungry, taking such food as

was offered, but never asking for anything. He was an excellent

draughtsman, and a good portrait painter; and on such occasions, he would

take up a piece of chalk or a pipe, and with a few strokes on the

chimney-piece, or the hearth, he would give an admirable likeness of any

person, or a sketch of any incident which took his attention. He had

an almost constant pain in his head, and it would seem that he imagined

his head was divided perpendicularly. His portrait, painted by

himself, and lately, if not at present, in the possession of his son, is a

very singular production, and a most correct likeness. He is

represented wearing a cap, something like the tiara of a Jewish high

priest. His face is divided by a gash down his right temple and

cheek, whilst his forehead is bound with a strap, buckled, and a bandage,

seemingly a hoop, passes across his face and his nose, as if to prevent

his head from separating. He wears a kind of loose vest or cloak,

with the collar in front, and his eye lowering from beneath his antique

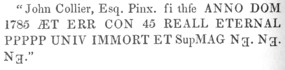

cap, has a strange and fearful expression. On the back of the

picture appears an inscription, of which the following is a fac simile.—

A TEMPERANCE ORATOR.

AT a time when the temperance movement

was making a great sensation in Lancashire, a meeting was one night held

in a room at Middleton, at which a new convert, known as "Owd Pee," stood

up, and shaking his head, expressed himself as follows:

"Aye, aw kno yo expect'n summut fro Owd Pee, but aw shanno

say mitch this toyme; aw'l gi' yo' a reawnd when none o' theese tother

speykers ar' heer. Awve bin a dhrunkart theese ten yer. Aw

laaft mony o' suit o' clooas i'th' aleheawse nook; aw laaft 'em bi three

shurts ov o' day. (laughter, and cries of "well done owd lad") Thur

wur no rags for th' rag-mon at eawr heawse i' thoose days; aw laaft 'em o'

i'th' aleheawse-nook. (Laughter) Boseeyo they'st ha' no moor o'

moine; noather um nur thur byegles, moynd tat. (Roars of laughter, and

cries of "that's reet owd Pee.") Aye! aye! they'rn reet enoof when

they geet'n me amung 'em; when they geet'n owd Pee to be a foo for 'em.

They'rn ust to ha' mhe agate o' feyghtin, an' aw went wom scores o'toymes

wi' th' skin off mhe back, an' o' stuck'n full o' sond un durt wi' rowlin

oppoth greawnd; but aw tell yo' awst do so no moor. Why, aw tell yo'

aw've had bi three good shurts ov o' day torn off mi back, an' aw bin

sitch o' foo asto goo worn an' want another, bu mi wife had moor sense nor

me, an' wudno' let mhe hav it.

One day aw're in a aleheawse nosso very far fro' this place,

an' they wantud to ha' mhe agate, but aw wudno' stur, an' so at th' last,

th' lonlort son, a yung felley, coom an' fot mhe a cleawt. Aw lookt

at him, an' shak't mhe yed; in a whoile he coom agen an' gan mhe another

seawse, an' wawkt tort th' frunt dur. Aw sed, "felley, iv theaw dus

that agen aw'l byet-te." Well, in a whoile he coom agen an' fot mhe

another good seawse o'th' yed, an' so aw at him an' beete him seawndly,

afore thur byegles cud fly in an' ridd.

Another toyme, when aw're agate feyghtin, they took'n mhe new

cloggs an' sett'n 'em oppoth foyer, an' when th' battle wur o'er, they gan

'em mhe to put on, an' aw put 'em on, an' th' rascots stood'n laighin at

mhe, for they brunt'n mhe feet, but aw gran an' abode, an' it wur mony a

week afore Dan Moors cud get mhe stockin' feet eawt o'th' sore places.

(Loud laughter.) Aye, yo' may laigh, but mind yo,' they'n ha' owd

Pee no moor for a foo; aw'l noather taste ale nor spirits. Aw'd

bwoth ale, rum, an' gin i'th heawse when aw gan o'er dhrinkin, but aw

never tucht none on 'em sinn, nor aw winno doo. (Cheers.) Aw shanno'

say mitch moor neaw, but aw'l gi' yo' a greadly blow eawt sum toyme elze

when ther's none o' theese tother speykers to tawk to yo'. (Cries of good

lad Pee! well done, Pee! until he sat down.)

A PASSAGE OF MY LATER YEARS.

ON the evening of a Friday in the

summer of 1826, when so much damage was done by mobs breaking machinery,

in the neighbourhoods of Blackburn, Burnley, Haslingden, and Bury; when

many thousands of pounds worth of property was destroyed by the starving

hand-loom weavers, many lives were lost, many of the aggressors were

imprisoned, and many transported to die in foreign lands; it was, as I

said, on the evening of a Friday of this eventful time, that a young

fellow whom I knew, came to my house at Middleton—called me aside—and

expressed concern at a plot which he said was being carried on in our

vicinity. At first he seemed rather unwilling to disclose all that

he knew, but after a little urging on my part, he said that certain

persons residing in the neighbourhood, had been in the habit of holding

secret meetings, and had once or twice sent delegates to the disturbed

districts in the moors, inviting the loom-breakers to come down into our

part of the country, when they would be joined by the working population,

and might make a clear sweep of the obnoxious machinery, all round by

Heywood, Middleton, and Oldham, and so return to their hills before any

force could intercept them. I did not at first place entire faith in

the representations of my visitant, and I told him I thought he must have

been somewhat misinformed, for I could not fully believe that any parties

in our neighbourhood would be so wicked, or were so mad as to encourage

such a thing. He however assured me he was right, and he mentioned

persons, and times and places of their meeting, which convinced me there

must be some devilish scheme going on to disturb the peace of our hitherto

tranquil district, and to cause a recurrence of scenes like those which

took place in the spring of the year 1812, when sad havock was committed

on property, and a number of lives were lost in our town; I therefore

thanked him, and, as the only reward I could give him, promised to make

some good use of the information he had afforded; and on further enquiries

in certain quarters, I ascertained, that from a dozen to a score of

persons of the worst character had got up the plot; that they had met

secretly, and delegates, and messages had passed to and fro betwixt them

and the leaders of the outbreak in the moors, and that the following

Monday morning was appointed for their next meeting on the hills, when

they would come down, and being joined by the workmen in our part, would

destroy all the mill machinery that lay in their power.

I was, I must confess, even after all my experience with

respect to popular commotions, somewhat startled at the blindness and

audacity of this scheme; yet, that it would be attempted, I had no more

doubt than I had of my existence, and I therefore determined to use my

best endeavours towards preventing the attempt from taking place. I

informed several of my acquaintance of the circumstance, and I even went

to Manchester and made it known to the late editor of the Guardian, and

having so far satisfied my conscience, I took upon myself the performance

of the remainder of my purpose.

It happened at that week's end, that I was particularly short

of money, so I went and borrowed a few shillings from one of my

acquaintance, telling him what I wanted the money for. Another

acquaintance, as poor as myself, had offered to pledge his watch to raise

the money, but I declined his offer, being desirous of trying all other

means rather than put him to such an inconvenience. Well, being thus

furnished with the needful, I set out from home early on the Sunday

morning, and traversing with quick and lengthened strides, the Parson's

meadow, I ascended the high ground on the west of Middleton, leaving the

wood—for there then was a wood—on my left, and Ebors on my right, I soon

passed Langley hall, and went through Birch, and up Whittle-lane, and on

through Pitsworth and Heap-fold, and so to Bury-moor-side. From this

place, without stopping, I pursued my course until calling at a little

shop, I quenched my thirst, and allayed my hunger by a draught of good

sharp treacle beer, and a roll of gingerbread, and so went on to Edenfield,

and thence to Haslingden, where resided a friend whom I believed had the

power to assist me in my undertaking. I found him out soon after I

entered the village, and having sent for him to a public house, I

ascertained that he was the very man I stood in need of, and I urged him

to introduce me to some of the leaders of the late outrages, that I might

make known to them the deception that had been practised towards them in

our part of the country, and the destruction that awaited them and their

followers, if they ventured down into the low districts.

After discoursing some time, and partaking the refreshment of

ale and tobacco, my friend agreed to conduct me to the parties I was in

quest of, and we accordingly went out at the west side of the village, and

after some time got upon the high moors, and to a place called Black Moss,

where several persons were informed as to the nature of my business, and

whither we were going. From hence we crossed a valley, and again

ascended high ground, and at length stopped near a small fold of low stone

houses, in a very lonely spot. My conductor left me, and entered one

of these habitations, whilst I took a survey of the bold and lovely

country around where I stood. On my right was Black Moss, the place

we had come through, and, a little more in front was Humbledon, a hill

where several insurrectionary meetings had been held. Beyond

Humbledon, arose the smoke of Burnley, and before me was Padiham with its

lovely valley, and its spectre-like population of weavers. Behind

Padiham and Burnley, Pendle-forest stretched wide and far, with its sunny

slopes and lonely dwellings, and its uplands thirsty with long drought,

and its watered dells still verdant. Then dark Old Pendle lay huge

and bare, like a leviathan reposing amid billows; whilst sweeping towards

the left, stretched other hills and moors, to me unknown, but all dotted

with houses, and marked by stone walls, and dark shadowy chasms, and green

nooks, and wreaths of white vapour rising for miles and miles, and

spreading on the wind. For, in consequence of the long drought, and

the intense heat of that summer, the moors and moss lands had cracked into

wide fissures, the edges of which had taken fire, and they were burning

and smouldering in some directions as far as the eye could reach.

Such is the recollection of the not unsublime picture of that bold and

striking land, the abode at that time of a population reduced to famine

and despair.

I had scarcely made such hasty survey, ere my conductor came

forth, accompanied by a number of men, to whom he introduced me, and by

whom I was received with a cold civility, not, as I thought, unmarked by

tokens of suspicion. They were all decent, thoughtful looking men,

and though the ghastliness of want was on their features, and though their

clothing was poor, very poor indeed, there was nothing like either filth

or squalor to be seen about them; their humble garments were neatly darned

or patched, and their calico shirts were clean; it was Sunday, and they

had don'd their best attire. Such were a group of Englishmen, of

English Saxons in truth, fathers of families, living on two-pence

halfpenny a day; how as many un-Unglishmen [sic.]—of the finest pisantry

for instance—would have born like misfortune, I leave others to describe.

We formed a kind of little meeting at a short distance from

the houses, and as we conversed, others occasionally drew towards us, and

joined us from different parts of the country. My conductor told

them who I was, and where I came from; "that I had been in several prisons

for seeking parliamentary reform; that I was at Peterloo, and was tried

with Hunt at York, and being one of those found guilty, I was confined

during twelve months in the Castle at Lincoln; that consequently I was an

acknowledged advocate for freedom, and the poor man's rights, and

understanding I had something of importance to communicate to them, he

thought it his duty to bring me amongst them;" in short, he did me justice

in a neat and brief address.

One of them asked if he knew I was the same person, the same

Samuel Bamford he had been speaking about? and he said he did know me to

be such; he had known me from a boy.

My identity having been thus established, a considerable

portion of coldness seemed to have left them, and they asked what it was

that I had to speak about?

I said I understood that delegates had been sent to them by

parties in the neighbourhood of Middleton, and they said there had been a

delegate up several times.

I said I understood that such delegate invited them to go

down to Middleton to break machinery, and had represented the people in

that part, as ready to join and assist them whenever they came, and they

said it was so.

I said I believed the delegate's name was

─── and they said that was the man.

I then told them that he was a discharged soldier, and one of

the worst of characters; that those who had sent him were only about a

score in number, and were all of them persons in whom no confidence was

placed by those who knew them; that the people at large, and the reformers

in particular, knew nothing of the plot, nor would they countenance it;

that weavers at Middleton could get their eight or ten shillings a week,

and I asked whether if they could do the same, they would not prefer to

stay at home with their honest earnings, rather than turn out and incur

the risks and anxieties which all outlaws and proscribed men had to

suffer? and they all declared, some of them most earnestly, that if they

could make their earnings anything like what the Middleton weavers got,

they would never attend another meeting of an illegal character.

I then asked them whether it was at all likely that the

weavers in our part would leave their good work, and their quiet homes,

and their comparative plenty, to join in a thing which would deprive them

of all their household comforts?—whether, if they themselves would not

join in such a thing, it was likely the Middleton people would join in it?

and they declared it was not likely; it was not to be expected.

I then conjured them not to be led astray by the parties who

had been corresponding with them. I told them the men who had

invited them would be the first to betray them, if they came down; and I

urged them by every argument that occurred to me, to abandon their project

and give up their mischievous connexion with the delegate and those who

sent him. I said I had nothing in view in coming amongst them, save

their own good; that after being made acquainted with what was going on, I

should have considered myself a betrayer, if I had not come up and laid

the whole truth before them; that I was not paid for coming; but did it at

my own expense, and on my own responsibility; that I sought no reward save

the approbation of my own conscience, and that, having thus performed my

duty, the result must be left with themselves.

They all seemed grateful for the interest I had taken in

their welfare, and informed me that a meeting had been appointed at an

early hour on the following morning, for the purpose of going down to

Middleton, and that they would have gone down; but that, in consequence of

my coming up, they would inform the meeting of what I had stated, and

leave it then to be decided upon. I urged them not to omit doing

this, and they promised they would not; and so reminding them, that if

they now came into our part, they would do so with their eyes open, and

with the sin and the responsibility on their own heads alone, I and my

guide took a friendly leave of the men, and returned to Haslingden, from

whence in a short time, I set off towards home, and arrived there at

night-fall, having travelled about thirty-six miles.

Well! the following morning betimes, the little knot of

villains who had concocted the business on our side of the country, were

on the alert, and listening until their ears cracked, for the sound of an

uproar, and an approaching tumult, but nothing was heard.

They sent scouts up to Ebors, to survey the hills of Birkle

and Ashworth, and to return and report when they saw the multitudes

pouring down towards Heywood, and they went up, but all was still, and not

a sound was heard; the chimnies were smoking, and the factories working at

Heywood as usual; the hill-sides lay mapped out in the clear air; the

white kine were seen browsing, the new washed linen was seen bleaching in

the sun, and the whole country was as quiet as on any other Monday

morning. This was perfect consternation to the plotters. Well!

eight o'clock, ten o'clock, noon came, and there was no change; nothing

was heard save the report of cannon down in the S. W. and that was soon

ascertained to arise from the practising of some flying artillery, who,

with cavalry, were traversing the road betwixt Bury and Manchester, so

that the troops, it would seem were also on the alert. The day thus

passed over in tiresome watchings and vain expectations, and when night

came they were informed by one of their own messengers, a swift footman,

that according to the appointment, a large meeting assembled that morning,

at Humbledon, expecting to make the promised descent, but that several of

the leaders were averse to it, and in giving their reasons for being so,

stated all I had told them on the Sunday, and added other reasons of their

own, arising from what I had said; the consequence was, that there was a

complete division in the meeting; some from towards Blackburn, Padiham,

and Burnley, were still for proceeding, whilst those with whom I had

conversed were decided not to do so, and a third party seeing these

divisions, entirely withdrew. The meeting therefore broke up without

coming to any effective determination; the thing fell through, the plot

was frustrated, and it never again was revived.

Happy was I that morning, when looking over my little garden.

I was startled by the reports of artillery; happy was I when having

learned that troops were on the Bury road, I reflected that but for me,

that powder, instead of being wasted in parade, would probably have been

expended in the sacrifice of human life; and the happiness arising from

that reflection has been my reward.

On the other hand, the disappointed plotters, who only wanted

an opportunity to plunder, were ferocious against me. Several hole

and corner meetings were held, at which I was denounced as a spy and a

traitor; at one of such gatherings held in a chamber at Bury, I was voted

to be a fit subject for assassination; but I never could learn that either

the proposer or seconder undertook to complete their resolution. To

my family these things were annoying, but I treated them with contempt.

I did not even go out with a stouter cudgel than usual.

It was just at the expiration of a month from the time when

this plot was defeated that another of the sort was developed, and

promptly put down; it lasted long enough, however, to confirm what I had

said to the poor calico weavers on the moors, as to what would be their

fate if they came down, and depended on the co-operation of the weavers at

Middleton; it exactly bore me out in all I had stated, namely, that those

who had invited them would be the first to betray.

At eleven o'clock on a Saturday night, about a hundred and

fifty, or two hundred strange men, from towards Manchester, most of them

armed, entered the market-place, at Middleton, and called on the people to

turn out and bring their pikes. They stood there drawn up in line,

and repeatedly shouted for their Middleton friends to come and join them.

Not a soul responded to their call, and they began swearing, and cursing

those who had ordered them to come. At length they began leaving

their ranks, and some of them went into provision shops, and others into

public houses, and demanded refreshment. This had just begun, when a

furious clatter was heard; a party of dragoons came galloping up, and the

invaders disappeared as totally as if such things had not stood in the

place. It was like a scene of enchantment, and the inhabitants who

witnessed it were quite bewildered. Several of the fellows, however,

were taken and put into the lock-ups, and the persons most active in their

apprehension, were of that very class of operatives from which they seemed

to expect assistance.

The plot on the moors having been frustrated, it was renewed

thus, and with more effect amongst the hand weavers of St. George's Road,

Little Ireland, and other out districts of Manchester, and we have seen

the result. The fact was, the originators were a set of thieves, who

wished to get up a row, that, during the scuffle, they might plunder the

more securely. Both attempts as we have seen, failed, and I count it

not one of the least fortunate circumstances of my life, that I had so

large a share in the frustration of the wicked and cowardly schemes of

those worst enemies to society.

WALKS AMONGST THE WORKERS.

No. VII.

MIDDLETON AND TONGE.

HAVING last week glanced at the condition of the

hand-loom weavers of Tonge, and part of Chadderton, it can scarcely be

expected that those of Middleton should not have a similar notice bestowed

on them. The course of work is nearly the same in all the three

townships; the number out of employ may be reckoned the same, viz:

three-fifths of the whole number of the hand-loom weavers, and the ratio

of distress—distress of some families, and serious embarrassment of

others—is also about the same. Since my last communication, I have

conversed with a most respectable gentleman, who has visited a district in

Middleton which is supposed to be the worst conditioned of any in the

town. He bears out my views with respect to the actual state of the

working population; and says that, though many families are really

distressed, the distress is not so entirely unmitigated as he has reason

for believing it is in some parts of the country; it has not yet come to a

stripping of the beds and the denuding of the walls of the houses for the

procurement of food. In fact, as I had stated last week, the

distress has come here after a good season for work,—I might have said two

good seasons—and the people were in some degree prepared for it. To

the general evil of want of work, there are, however, some relieving

exceptions. The extensive concern of Messrs. Salis Schwabe and Co.,

of Rhodes, who employ, on an average, from six to seven hundred hands,

are—with the exception of their block printers—all in full employ, and

more than that, for most of the workmen make very long over-hours, and

they consequently draw a handsome little sum at pay-day. The

spinning and weaving concern of Messrs. John Burton and Son is also in

constant work, as is that of Mr. Gill, at The Lodge; whilst the smallware

manufactory of Messrs. Jackson and Royle, at Lower Tonge, which employs

about one hundred hands, one-third of them perhaps being females, is, like

Schwabe and Co's., exceedingly brisk, and the hands are encouraged to do

as much over-work as they can. These concerns, as may be inferred,

embrace a considerable number of the population, and keep them at work,

leaving the evil to rest, as before intimated, upon the hand-loom weavers,

and some others dependent on that branch. Messrs. Stone and Kemp, an

extensive firm in London, having a silk manufactory at Middleton, are,

like others in the same branch, slack of work at present; and their

weavers feel the pressure of the times. The superintendent here is,

however, as I am informed, in the habit of affording relief in food to

some of the poor weavers; Messrs. Schwabe, of Rhodes, do the same, not

only by their own short-working block-printers, but the distressed from

other parts: the principal of this firm has also given a sum of money for

distribution to the poor in the town of Middleton. A gentleman,

connected by property, and recently dwelling in the neighbourhood, has

likewise sent ten pounds to be distributed; a munificent lady in an

adjoining township, has also been very good to the poor, visiting them at

their houses, and relieving their wants with her own hands. Nor, I

am gratified to have to say, must I stop at the clergy of the

establishment; without mentioning names, or clerical distinctions, which,

I believe, they would rather avoid, I feel bound to say that they have

done, and are still doing all they can, in visiting, inspecting, and

relieving real objects of charity, without reference to creeds in

religion, or parties in politics. Besides gifts from their own

resources, and they have not been either small or few, they have become

the almoners of others' bounty, and the poor have hitherto, and probably

will continue to be, both cared for and looked after. It is further,

as I understand, in contemplation to get up a concert in the course of the

present month, the proceeds of which are intended to be given to the poor.

The churchwarden has also, this Christmas, made his annual distribution in

cloth, to the amount of about sixteen pounds; so that, on the whole, by

the time the spring trade comes round, the weavers will have an

opportunity for returning to their work, with their hearts imbued with one

of the most pleasing of sentiments,—that of gratitude.

The styles of work done here are from the commonest gros

de naples, up through printed work scarfs, tippets, satins, and

jacquard work of all descriptions, besides the smallware silks done at

Messrs. Jackson and Royle's, some of which are also woven by jacquard.

There are abundance of hands, most of them familiar with silk from their

infancy; coal is cheap, water plentiful, ground-rent low, rates very

light, and roads (beside the Manchester and Leeds railroad) good; carriage

being, consequently, easy and cheap, there is a fine opening for the

establishment of manufactories by one or more London houses in addition to

that of Stone and Kemp. The wages are below those given in London;

for instance, gros de naple, three thousand three hundred reed, are

fourpence per yard; satins, six thousand reed, seven-pence three

farthings; six thousand four hundred, eight-pence farthing; satin shawls,

seven-fourths, four shillings and sixpence each, and the same,

eight-fourths, five shillings and sixpence. Last year these shawls

were each a shilling more for weaving; but, they have been reduced, it

being allowed that they would bear a reduction better than any other

article in the trade. The shawl manufacture has been most dull here

within the last three months; it is expected, however, to revive in a few

weeks, as preparations are in progress by several houses for an increase

of that article. It is probably expected that the reduction in price

will tend towards increasing the demand. One house, in Manchester,

is working a variety of goods by the steam-loom; the weavers receiving two

shillings a day, and it is said that one of these looms will turn out two

shawls a day. This is certainly bringing things to the lowest cost

at once, so far as workmen are concerned; but how it will work in the

gross, at Manchester, where chief-rent, rates of every description, coal,

and other outgoings are high, is best known to the parties trying the

experiment. Another house, I have been informed, is removing its

crape-weaving from the district of Chadderton, and is about weaving it in

town, in a place prepared, and by steam. If these experiments

answer, in a few years the fate of the calico hand-loom weavers will have

become that of the silk hand-loom weavers—a fate which they are not all

expecting, nor in the least prepared for. But whether the work is to

be done by hand or steam, Middleton offers about the finest field for the

experiment; and, if I might hazard an opinion as to the result, I should

say that, when our provision laws shall have been relaxed or done away

with, and other measures of free trade introduced, the hand weaver will

beat the steam weaver whether he will or no; a result which the holders of

large weaving establishments little expect.

In the higher parts of the township of Tonge many looms were,

some three or four years since, employed in weaving broad cotton table

cloths; numbers of these looms are now occupied with a description of

carpets for the foreign market, that of South America, and a rather

fanciful description of cotton scarfs for personal attire. There is

room for an increase in these last articles, and, indeed, a probability

that both these and the other courses I have mentioned will continue and

increase, notwithstanding experiments in machinery.

WHAT SHOULD BE DONE?

FRIEND ACRELAND,

You put me in mind of my implied promise to recur to the

above subject, and I take the present opportunity for doing so.

You know that we agree, or at least, I assume for argument's

sake, that we agree with the declarations of government, and the ministers

of religion of nearly all denominations, that, "the peopIe should be

educated." But we go further than do either the state ministers or

the religious ministers; we say the people should, nay must be fed and

clothed before they can be educated; and in order to this, they must be

employed, and paid for their employment. Not the off and on

employment which is the frequent lot of too many of our workmen, but

constant employment, such as will bring its Sunday dinner and Sunday duds

with every Sunday, and its good substantial meal with every meal-time on

the working days. I mean to say that whenever a man works, or

wherever he works, he should eat his fill at meals; and that no man who,

can work and is willing to do so, and thereby to earn his bread, should be

prevented from so doing; if he is prevented, there is something wrong

somewhere. This may suffice to show what I mean by being employed

and fed.

Now then, how is that grand panacea, employment, to be

procured? I say, unfetter commerce, promote agriculture, and leave

the rest to heaven and our own long heads and hard hands, and fear not.

Unbind the swathed giant, Industry, and see if he won't assume a multiform

that shall keep both want and the world at bay. Yes, unfetter

commerce; abolish the duties on food; cease to make land dear, bread dear,

and, at the same time, labour cheap; in short, extend to commerce the

principle of your improved postage, and depend upon it, similar benefits

will follow. Whatever is lost in the price of things, will be more

than made good by increased demand, and prompt payment; and thus there

would be more labour, more food, and, no doubt, plenty of both.

"Oh, Oh!" methinks I hear you say, "you're coming on with

your free trade jargon now; couldn't you argue the question without

touching that irritating subject?"

The question, friend Acreland, is, "What should be done?" and

I am stating my views as to what should be done, together, in my humble

way, with my reasons for those views.

You know I am in principle a free trader; you must have known

it long, for you cannot have forgotten my telling you, and repeating it to

others in your hearing, how I was one of those who went to the great

meeting at Manchester, in 1819, and that on one of our banners were

inscribed the words, "No Corn Laws." You have heard me declare that

all the reforms we asked for on that day, I would still obtain it I could,

or modifications of them fully equivalent to what they would accomplish in

the way of reform. This matter therefore is settled. I am a

free trader from principle, not from expediency. I advocated it when

it was dangerous and disreputable even in this town of Manchester to do

so, and I still advocate it; because, in the first place, it would

increase employment and make it constant; it would increase food, and make

it cheap, and doing so, it would tend to make the people more happy, more

tranquil in their minds, and more susceptible of that cultivation which I

deem to be absolutely necessary to the permanence of government, and the

welfare of the people.

But though these are strong reasons why I should be an

advocate for trade, and a free trade in corn especially, still stronger

reasons, have all along, presented themselves to my mind. Many good

men here, in this South Lancashire of ours, are opposed to the corn laws,

because, as they say, and I believe truly— they injure trade, and

restrain manufactures. These, considering our present state of

society, are also strong reasons against the continuance of those laws,

but I am moreover opposed to them because they are wicked; because they

are an astounding evil to mankind; because they snatch the crumb from the

lips of the hungry and toil-worn, saying, demon-like, "not yet; thou hast

worked for thy bread, now work for the tax ere thou eat it;" "thou hast

worked like a good man for thyself and thy children, now work for the

squire's extra rent; work for his dog-kennel, and his daughter's portion,

and his lady's jointure, and his son's outfit in the world; work now for

these, and then take thy loaf and eat." Well, the work is

again set about; but, whilst it is being performed, what else is going on

in that man's heart? why deepest hatred to be sure! rebellion is born!

vengeance is laid in store! infernal machines are planned! plug-drawings

are dreamt of! rick-burnings are meditated! and a general havock, and an

up-setting, and a down-casting, and a wide wasting of life and property,

are looked to, and hoped for, as the only cure for a burden so intolerably

unjust, and audaciously oppressive. Yes, it is because the corn laws

are eminently wicked that I am opposed to them. A bad trade is a

woeful bad thing for this country, but it is nothing compared with the

curse of living under laws which we daily and hourly execrate because of

their injustice. Hunger, we know, will "break through stone walls," it is

so hard to endure ; it kills the body, it murders by inches, or rather by

crumbs; but hard work though it be thus to kill the body, is it not harder

to kill the soul? to put to death God's image in the heart? to cast forth

all mercy and kindness, and patience, and beauty; to thrust these away,

and to fill their place with hatred, cruelty, rapine and overt revenge,

all working bodily peril and pain, and soul-damnation. Is not this harder?

is it not a deeper sin? Then comes the demagogue to make a fermentation—a

kind of hell-bubble of all these passions and things; and fitting dupes,

ready-made dupes, oppression-stamped dupes, finds he waiting at hand. One

shall have "a great demonstration," another "a sacred month," another "a

charter," a fourth "a fire-light meeting," a fifth prefers "lucifer

matches and a homestead," whilst a sixth shall be most handy with his

"knitting needles, amongst the cog-wheels," and a seventh, wisely advised,

and implicitly obeying, shall, "draw from his bank, and lay out his

children's coffin and shroud money in the purchase of pike, and dagger,

and gun, and pitch-torch." Such instruments have unjust laws prepared for

the hireling demagogue, and the cowardly instigator.

Still I have not done; there are deeper thoughts to come out yet; and if

you, dear Acreland, have any acquaintance either with Sir Robert, or the

Duke of Richmond, you may just let them know all I tell you. I have not

any secrets in these matters. Turn-about Chartists and their present

employers, may affect to know better than I do, but never mind what they

affect, confide in what I say, and be assured that men's thoughts

are taking a deeper turn than either the Duke or Sir Robert are aware of.

I have seen the people when discussing in groupes by the road-side,—or

the field walks—by the hedge-nooks—on Sunday mornings—far from the

League and all its influences—in the sweet balmy air of summer—amid the

sun-showers of spring—on the cold eve of winter—and after the day's work

in autumn—I have seen them in various situations, and under many

different circumstances when expatiating upon, and denouncing the corn

laws. I have seen them with their brows knitted like cable ropes, and

their eyes flashing, and their strong arms stiffened, and their fists

clenched as hard as mallets, by the influence of indignant emotion caused

by this great wrong. I have seen these outward and visible signs of their

inward feelings, and I have also heard words which made my ears tingle,

and my heart leap; words that coming from the quarter they did, and

elicited under the circumstances they were, I knew to be ominous of no

good to those who, despite of all warning, of all entreaty, continue these

bad laws.

"If ever the time does come,"—I have heard it said,—"and that it will

come, is as sure as that yon sun will set in the heavens; if ever the

time does come, when the whole people shall assume their rights, and shall

discuss their claim to the whole land; whenever that time arrives, the

strongest argument for the measure; the strongest charge against the

landowners will be the fact of their having whilst in power, enacted

a law to keep up rents! to make bread dear! to fill their own pockets at

the expense of the rest of the community! Ah! the short-sighted ones!

Why not mete out to us the breath of heaven? why not charge us with our

sun-light? why not gauge and tax our wells, and our brook-steads, and

rock-springs. Why not? for these are not more our inviolable rights, our

absolute necessaries, than is the bread for which we have toiled. The

injustice cannot continue! it cries to

heaven! it disquiets the earth! and assuredly it will cause a just, but

a terrible retribution. Will not our children say in those days? and

shall we instruct them otherwise? will they not say, "Let this

landowning class cease. They were entrusted with power and they abused it; they were endowed with honour, and they disgraced it; they were endowed

with riches, and they remained sordid; they were exalted amongst men, and

yet grovelled with the lowest; they might have been merciful, but they

were cruel; they might have been munificent, but they were

avaricious—mean; they might have been just, but they were unjust; they

might have learned wisdom, but they preferred ignorance; away with them!

they have been weighed in the balance, and have been found wanting; they

have had their day! Our fathers and ourselves have long since paid for

the land by unjust taxation, and we will have it! away with these

fellows! the land is ours! put them out! down with them!"

Such, friend Acreland, is one of the results of unjust

laws: one wrong begets another; one outrage lays the

foundation—sanctions the perpetration of more extensive outrages; and

though the bread-tax has become a law, it is not the less an outrage

against common sense, and plain common right.

Away then, I say, with the corn laws, and all other laws that tend to make

food, or clothing, or house, or land dear; abolish them as speedily as

possible. Let the people be employed; let the people be fed; let them be

comfortably housed; let them have all bodily necessaries for their labour;

set their minds so far at ease; let their hearts be ameliorated;

cultivate their generous feelings; let contentment and thankfulness be

awakened; then instruct their minds, and teach them all useful knowledge

suited to their capacities and pursuits. Let the ministers of religion

give their aid, and eschewing—if it be possible they can learn so much

charity—creeds and dogmas, let them agree upon and teach the broad

essentials of christianity; keeping the bushy, worthless disputations to

themselves, who have time for those things. Let this be done, and we will

soon have a cultivated people.

Such a people would not be long in obtaining, by fair, by peaceable, by

honourable means, all the civil rights they wanted. The labouring

population would be what it ought to be, at once the support and defence

of the state; the middle class would transfuse a vigorous life and

action, and thought, through all the body

politic; whilst the monied and landed class—no man then wishing either "to put them down," or "thrust them out"—would live in security, like elder

brothers, or fathers of a happy and grateful household. England, aye, and

Scotland too, would thus have their rights; would have justice, and having

got it, wouldn't wait long ere they took care that Ireland should have it

also; yes, there would be "justice for Ireland" then you may depend upon

it, friend Acreland; justice for Ireland in full. Irishmen would then

cease to bluster and blarney—neither having much effect with us—they

would then become more just towards each other—a thing they are sadly in

want of, on that side the water. Then we would strip Paddy of his rags,

and his filth, and flinging them to the devil—if we could—we would

clothe him anew, and bring him home like a brother that had been lost too

long. We would seat him at a board as plenteous as our own, and thus with

all kind treatment, we would put into his head better things than he has

learned from his priests; more noble sentiments than those he heard at Mullahmast and Tara. This is what we "Saxons," would do, and do it also,

not because we cared one rush about any repeal hubbub that might be going

on; not because we deigned to bestow even one pitying, pshaw! on the bullyism of Yankee and Mounseer, put together, but because we Saxons

having obtained our rights, would wish to see our neighbour Celts have

theirs also; because,

that strong feeling which impelled us to become free ourselves, would not

let us be happy until, from the uttermost verge of our state, should be

heard the voice of a free, happy, and industrious people.

I am, dear Acreland,

Your's truly,

SAMUEL BAMFORD.

Blackley, July 16th, 1844.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE MANCHESTER ADVERTISER.

SIR,

WILL you allow me a short space for a

few words in reference to the conduct of the persons styling themselves

chartists, at the meeting held for the repeal of the corn laws on Friday

last? Of all the political inconsistencies which have come under my

notice, none has appeared to me more unreasonably and humiliatingly absurd

than were their proceedings on the above-mentioned occasion. A number of

poor, and some of them personally hard working men, are heard to complain

of oppression, and they adduce as a proof of it, the raggedness and famine

to which themselves and their class are subjected; yet they clamour, not

for, as one might expect they would, but against cheap bread! which, in

fact, means cheap everything,—cheap clothing, cheap rent, and cheap

government, in its degree.

Twenty-years ago such a thing would have aroused universal

indignation throughout the ranks of reform. The old fathers and dames of

those days—the wives and children, would scarcely have credited their

ears, if told that in any part of the kingdom a body of working men had

been found who not only repudiated a petition for abundance of bread for

themselves and families, but actually insulted and abused others who were

endeavouring to obtain it for them. Major Cartwright, Lord Cochrane, Sir

Francis Burdett, William Cobbett, Henry Hunt, and all the leaders of

reform, would have denounced the "famine-seekers" at once, and would have

declared their proceedings treason against the first law of nature, and

blasphemy against the first prayer, "Give us this day our daily bread,"

and a long and deep groan of execration would have arisen from the toiling

and hungered myriads from one end of the island to the other.

One of the most offensive banners which appeared at the great meeting of

the sixteenth of August, 1819, was that whereon was inscribed "no corn

laws," and at nearly every reform meeting throughout the kingdom

resolutions were passed condemnatory of the corn laws. Seldom were those

obnoxious statutes forgotten. But now the chartists say, "we won't have

cheap bread, unless we have the whole charter also;" which is equivalent

to saying, "we won't have to-day's dinner until to-morrow's breakfast is

ready,"—"we won't have our meals at three separate times, but take them

all at once,"—"we won't wear jackets until we get clogs," "we won't, in

short, accept any part of all that we want; we will have the whole or

nothing."

Was such a thing ever propounded by sane minds before? Is there in all

nature any known power to enable poor imperfect man to rise instanter, of

his own will, a perfectly endowed being? In all time, has such a feat

been accomplished by individual, or multitude, or nation? In all history,

does such a record occur? If God himself was six days in perfecting

creation, why should not erring and feeble man be content to work out

whatever he may seek for good, with such humble means, and by such

protracted labours as his imperfect condition and acquirements impose upon

him? recollecting, as he should, that he has not only to struggle against

his own weaknesses, but against those of other fellow creatures, who may

be as much disposed, and certainly have as great a right as himself, to

close their ears against the truth, or to shut their eyes against the

light.

The slave who refused nourishment until he died or were free, would act

consistently and so far respectably; but one who said, in mock heroic, "Well, if I must remain in bondage, I'll be up with 'em at any rate—I'll

make my life as extra miserable as I can—I won't eat a belly full of

meat, hang me if I will," he would only get laughed at, whilst his

experiment would assuredly break down in time. About eighty years ago, a

poor weakling, known as Know-man, used each Christmas to visit the old Assheton family, at Middleton Hall, on which occasion he generally had

a silver sixpence given him as a present. At one time

a gentleman who was on a visit would give him a sixpence also, but

Know-man, shaking his head and looking cunningly, said, "Nawe, nawe, I'll

ha' no fresh customers." The chartists do the same, they will "ha' no

fresh customers," "no fresh aids." They may be sensible men, I don't

dispute it; but poor Know-man was always afterwards set down as unfeignedly crazed.

Even in our commonest transactions, how thoughtful we must be, and how

carefully we must move, step by step, in order to secure good and escape

evil. What thoughts and schemes from night to morn rapidly succeed each

other, ere we advance one good day, nay one good hour in life. And yet a

party are found who tell us we must obtain all our political rights at

once, or accept nothing. What would our country chartists think if Robin

O' Dick's, or John O' Tummie's, or any other of our great Lancashire apple

or gooseberry growers, were to stand by his trees, and refuse to gather

his fruit as nature offered it, declaring he would have none until the

whole were ripe, until one grand shake would bring the whole down? Would

they not turn away seriously, and say when they got home, that so and so

was utterly demented, and that the overseer should be fetched, and the

poor fellow should have a blister on his head? Would they

not say so? To be sure they would, and speak sensibly and humanely too. Yet such is the system which the chartists avow and boast of.

Why, is not the whole of man's life made up of a multitude of little

events and things, following each other as fast as ourselves and nature

can force them? Is not our existence a succession of stages of being,

until we are, step by step, matured in our several degrees? Do not our

mothers, and our fathers, and our own recollections attest this to us? And do not we attest it to our children? Is there any other possible way,

save the step by step one, in which we can work to our meridian and end? Is it not consistent with

all nature, in everything? Are not our houses set up

brick by brick? And our wells dug shade by spade?

And our trees hewed with many blows? And our ships floated after many

stages of preparation? Yet, in politics, we are told, we must jump to a

conclusion!—we must have a miracle!—a perfection all at once! We must

get up some morn, "lords of the creation," indeed! or we will, and our

wives and children shall, remain ragged, starved, and moody slaves!

In all science, Englishmen may be accounted as proficient, at least, as

those of any other country. In the science of politics (the forbidden one)

they are, as I believe, with the rest of their species, as yet but

children, comparatively: but because "an Irish gentleman" has chosen to

recommend that they at once attempt a master-stroke in the science with

which they are the least acquainted, the experiment must be tried! a

miracle must be wrought! the "charter of democracy" must be obtained in

the lump! Well! who'll

go into the stronghold of the withholders and fetch it out? Several have

sworn aforetime they would,—but did they do it? did they keep their oath? Poor John Frost was the only one who kept his word,—who did more than

talk. He raised the devil about his ears,—but what laid him? The blood of the poor vain man's comrades, and the

sacrificing and dungeoning of his better-hearted dupes.

Oh, no! the chartists may depend upon it, that if they will go forward to

erect a monument of patriotism, they must proceed in a regular, cool, and

workmanlike manner; as good workmen always do. They must take the best

materials they can find, and use them to the best advantage, forming the

mis-shapen, and softening and bending the stubborn with much patience and

skill. It will not do to get ill-tempered and sulky, because all they want

is not ready fitted to their bands; they must not bluster when the winds

blow, nor stand haranguing when the waves roar. No Demosthenizing! there

has been too much of that; no bragging about rearings and "goose-eatings

at Michaelmas;" no swagger; that don't make bricks. They must work

patiently, and steadily, and permanently, and wisely, and the more

silently the better. They must, in short, begin with a beginning which I

fear they don't like to try; and until they do so, there can be no hopes

of a good end.—I am, sir, your obedient servant,

SAMUEL BAMFORD.

March 24th, 1841. |