|

PART I.

CHAPTER I.

THE HARD LOT

OF THE WORKERS ―

THE FIRST FACTORY

ACT ―

ROBERT OWEN.

THE lot of the

workers at the end of the 18th century and in the early part of the

19th was a hard one. In 1802 the first Factory Act was passed at the

instance of Sir Robert Peel. It was described as an Act "for the

preservation of the health and morals of apprentices and others

employed in cotton and other mills." The immediate cause of the Bill

was the fearful spread through the factory districts of Manchester

of epidemic disease, owing to the over-work, scanty food, wretched

clothing, long hours, bad ventilation, and overcrowding in unhealthy

dwellings of the workpeople, especially the children. The hours of

work were reduced to 12 per day, but the Act did not apply to

children residing near the factory in which they were employed, for

they were supposed to be under the supervision of their parents. In

his "Industrial History of England." Mr. H. de B. Gibbins says: "We

hear of children and young people in factories overworked and beaten

as if they were slaves;" and Southey, writing in 1833, said of

factory labour that the slave trade was mercy compared to it.

To Robert Owen is due the credit of being the originator of

co-operation. He was born in 1771, at the commencement of the new

system of industrial life. The factory system took the place of the

domestic, and the conditions of labour were entirely changed. The

people whose labour was rapidly displaced by machinery could not so

rapidly adapt themselves to the new conditions, and there was deep

poverty and severe suffering. This was the problem that faced Robert

Owen, and in an endeavour to solve it he spent his life. He saw the

danger lurking in the discontent of the people with regard to the

apportionment of the wealth of the country, and he set himself to do

what he could to avoid that danger. He devoted his time, money, and

energy to the education and welfare of the people from whom

co-operators sprang, with the result that in later years it became

very much easier to co-operate. He had lived amongst the people, and

knew what they suffered, and he made it his chief aim to ameliorate,

as far as he could, their lot. He suffered for his efforts; derision

and scoffing came to him, but he never turned aside.

After occupying situations in large drapery businesses, including

one in St. Ann's Square, Manchester, and being a partner of a

concern which made what were called mules, he became a manufacturer

of fine yarn, first as an individual employer and afterwards as

partner in a larger concern, and was regarded as one of the best

judges of cotton in the market.

How to get the most out of the machinery of Watt, Arkwright,

Crompton, and others became the first consideration of the majority

of the cotton manufacturers, and the factory system was pushed to

extremes. By means of the Factory Acts and in other ways much has

been done to remove those evils, and the lot of the present-day mill

worker is a happy one indeed compared with that of the worker in the

same position in Owen's days.

On the 1st January, 1800, he commenced operations as a cotton

manufacturer at New Lanark, Scotland, and at once commenced an

experiment for the improvement of the condition of the workers, his

aim being not to he a manager of cotton mills only, but to change

the circumstances by which the people were surrounded, and which

were so injurious to them. By the directions of Mr. Dale before him

the pauper children working at the mills, who were in those clays

brought in large numbers from other parishes and housed in sheds,

had been well lodged, fed and clothed; but Owen decided that no more

pauper children should be received. He also determined that the

village streets should be improved, and that better houses should be

built to receive families to fill the places of the pauper children. There was at that time little if any protection of the workers by

the law, but Owen did so much for them that differences arose

between his partners and him, who thought he was expending too great

a portion of the profits in that direction. He found a ruinous

system of credit in operation, the small shopkeepers buying and

selling on credit at high prices. He opened stores; bought for cash

and sold at cost, at a saving to the people, it is said, of 25 per

cent. The distrust of the workpeople was gradually removed, and when

Owen, although he had to close the mills in consequence of the

embargo placed by the United States on the export of raw cotton,

paid them full wages for nearly four months, their complete

confidence was gained. In spite of the opposition of his partners,

who were in two cases bought out, he had schools erected, and

although the cost per child was about £2 per year, the parents were

charged only 3s. per year, the firm paying the difference. At twelve

years of age the children could be sent into the works to contribute

to the support of the family. He met opposition not only from his

partners, but from other factory owners, and even from the clergy,

the latter seeming to think that his efforts in the direction of

education were an interference in their province. Others regarded

the intellectual advancement of the workpeople as a political

danger, and there was a risk of reform being denounced as an effort

to upset the throne, attack property, and overthrow religion. Lloyd

Jones, the author of "The Life and Times of Robert Owen," says,

however, that in the matter of education for the people Owen was

successful beyond his most sanguine expectations, and that there is

every reason to believe that his last partners were thoroughly

satisfied with his management as an employer of labour and a maker

of profit, the profit realised being more than the deed of

partnership required. The villagers presented a written address to

the partners, thanking them for the many advantages enjoyed and

expressing a desire that all cotton spinners might enjoy the same

advantages.

One of the strongest arguments for the existence of our co-operative

movement is found in the opposition of Owen's partners to his

efforts on behalf of the people. The partners were so afraid that

their profits might be reduced that they forced a dissolution of

partnership. Yet his management of the New Lanark Mills was so

successful that, after paying 5 per cent on the capital employed,

the net profit was at the rate of £40,000 a year. What an immense

amount of good for the people might have been done had that profit

been devoted to the purposes of the many, instead of taken by the

few.

As showing the disinterestedness of the man, it may be mentioned

that the meetings held in London for the fighting of the cause of

the factory children cost him £4,000. He purchased thirty thousand

extra copies of papers containing the reports, and had copies sent

to the ministers of all the parishes in the kingdom, and to all

members of both Houses of Parliament. It is related elsewhere that

in 1829 there were established 130 co-operative societies, and that

by the end of 1831, although the exact number cannot be given, there

were about 250 societies. The work of Robert Owen had prepared the

way for their establishment, and although most of them went out of

existence, they in turn had prepared the way for such societies as

ours, on the Rochdale system. As Lloyd Jones puts it, it constitutes

a special claim on our gratitude that Robert Owen brought into

practical activity for the public good the energies of the humblest

and poorest to augment the vast popular power by which the present

co-operative movement is sustained. He laboured for the people; he

died working for them; and his last thought was for their welfare. He was laid to rest within a short distance of his birthplace, in

1858.

In October, 1908, the Co-operative Wholesale Society held an

exhibition at Newtown of co-operative productions, to commemorate

the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Robert Owen. A few years

before appreciation in a tangible form had been shown. Opposite the

house wherein he was born stands a public library, and a tablet

indicates that the Co-operative Union, acting on behalf of the

societies of the country, was by far the largest donor to the

building fund. A portion of the building is dedicated to his memory,

another tablet making that fact known. Co-operators have also

erected a memorial over the grave in Newtown churchyard, and it has

been placed in the care of the local society by the Co-operative

Union.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

G. J. HOLYOAKE.

AS the life and

work of Robert Owen had such an influence in the direction of

co-operation as we know it, so, it is thought, should any history of

the co-operative movement, whether in a town or over the world,

include more than a passing mention of the later work of G. J.

Holyoake.

He was born in Birmingham on the 13th April, 1817, in days of social

ferment. A commercial panic had reduced his parents from comparative

comfort to anxious privation. His mother was a deeply religious

woman, and brought up the boy very carefully. At the Sunday School

he was considered so extremely pious that he was called "The angel

child." He began his business career in days when labour was

absolutely at the mercy of capital, and when it was almost a social

misdemeanour for a working man to take an active part in politics. Before he was seven years of age he worked in a business conducted

by his mother, and at nine he commenced regular work as a

whitesmith. The impression he received while working at the foundry,

of the petty tyranny of masters and the apathy and helplessness of

workmen, played no small part in shaping his career. He came under

the influence of Robert Owen in 1837, and in consequence of the

bitterness of the clergy towards Owen and those who held his views,

and because of their accusations of heresy, was led to taking sides

with free-thought. During the same year he began his advocacy of

co-operation. With three fellow students of the Mechanics' Institute

he formed a small Utopian community, and they all four lived

together in an "associated house." What these young men advocated on

a large scale they sought to practise on a small one, on the

principle that one should do what one could, when unable to do what

one would.

Mr. Holyoake associated with the Chartists immediately after the

passing of the Reform Bill, when he was but 15 years of age; but,

although a Chartist and frequently acting with the party, he never

joined in their war upon the Whigs. He even published a criticism of

Chartism, in which he suggested that violent action was altogether

unnecessary, and he became an exponent of the best aspirations of

the working classes. He became an uncompromising foe of churches and

churchmen, and that attitude was mainly due to the relentlessness

with which the Church persecuted unfriended free-thought, and the

harsh legality by which it gathered taxes from the very poor of the

parish in which he lived. One of his earliest memories was of a time

when his parents were struggling to keep the wolf from the door and

his little sister fell dangerously ill, sadly needing all the

nourishments that could be afforded. The money laid aside for the

church rate or Easter dues had to be expended on suitable food for

the sick child. Within a few days the rector issued a summons, and

dreading the possible warrant of distraint, such as had been served

upon a neighbour, the mother took the money herself, none of the

children being old enough, to pay the dues. She was kept waiting at

the court five or six hours until the case was called, and when she

returned the child was a corpse. So very dear was this young sister

to him that from the moment of her death he unconsciously turned his

heart to methods of secular deliverance. Mr. Holyoake has been

described as an atheist; Mr. C. W. F. Goss, author of the admirable

bibliography of the writings of G. J. Holyoake, says he was not an

atheist, although he was wholly for the right of atheism, or any

other opinion that appealed to reason to be heard.

In 1845 the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows offered five prizes of

£10 each tor five new lectures on Charity, Truth, Knowledge,

Science, and Progression, to be read to members of the order in

taking successive degrees. There were 79 competitors, some of them

clergymen, and Mr. Holyoake, taking for his motto "Justitia

Sufficit," was awarded the whole of the five prizes. The

lectures were sanctioned by the Bristol A.M.C. in June, 1840, and

published. They are still used.

He was one of the most earnest advocates of the repeal of the taxes

on knowledge. One of his experiences was to be sued by the

Government for publishing newspapers on unstamped paper. Early in

the 'thirties the price of a newspaper was 7d., including the 4d.

revenue tax. In 1836 it was reduced by 3d, and in 1840 Mr. Holyoake

became one of the active and enterprising members of an association

formed to secure the exemption of the Press from all taxation. Each

copy of a paper sold without a stamp involved a fine of £20 and

possible imprisonment, and it is said that he incurred penalties to

the extent of £600,000. The Treasury authorities appealed to Mr.

Gladstone, whose reply was that he knew Mr. Holyoake's object was

not to break the law but to test it, and who shortly afterwards

repealed the taxes which fettered the Press. The repeal of the Act

caused the prosecution to be abandoned.

The first part of the history of co-operation in Rochdale,

1844-1857, written by Mr. Holyoake, was issued in 1858 under the

title "Self-Help by the People." The book was reproduced in every

European language, while in England it was the seed from which

sprang 250 co-operative societies in two years. Later a second part

was added, and the whole published in one volume entitled "History

of the Rochdale Pioneers." This has been reprinted three times, the

last issue being dated 1907.

In 1868 he became editor and joint proprietor of the Social

Economist, which was, with true co-operative spirit, suspended

in order that the Co-operative News might be the collective

organ of co-operation.

His greatest literary work for the movement, however, is the

"History of Co-operation," commenced in 1873. The first volume was

published in 1875 and the second in 1879. A revised and completed

edition was published in 1906 by T. Fisher Unwin. Mr. Holyoake wrote

the history of the great Leeds Industrial Co-operative Society, a

society of 48,000 members, which completed its fiftieth year in

1897. In that book he writes: "I knew co-operation when it was born. I stood by its cradle. In every journal, newspaper, and review with

which I was connected I defended it in its infancy when no one

thought it would live. For years I was its sole friend and

representative in the press." At the advanced age of 85 he performed

the ceremony of unveiling a monument over the grave of Robert Owen

in Newtown churchyard.

In 1902 Mr. Holyoake defended the cause of

co-operation against the private traders. The traders had

adopted their boycotting tactics in St. Helens and other towns, in

many cases getting people dismissed from employment solely because

they were members of co-operative societies, and he wrote a series

of ten papers for the Co-operative

News in answer to the tradesmen's arguments. They were afterwards

published in a volume entitled "Anti-boycott Papers." He was a close

friend of such men as Garibaldi, Emerson, John Bright, Richard

Cobden, John Stuart Mill, W. E. Gladstone, and many others. His

personal qualities were honesty, love of truth, charity, sympathy,

unvarying good nature, and fairness towards his fellows and towards

his foes. Mr. Cobden said he was the man to say the most unpleasant

thing in the least unpleasant way. Almost the whole of his life he

laboured for the cause of social reform and to ameliorate the

condition of his fellows, and as an advocate for co-operation he

helped to bring greater comfort and happiness to the operative

classes and to provide working men with better homes, better wages,

better food, and better opportunities for the educating of their

children. He died in 1906.

There was a unanimous resolution at the Birmingham Congress in 1906,

that the life and work of the late G. J. Holyoake and his services

to the co-operative movement be perpetuated by a building bearing

his name, to be erected as a habitation for the headquarters of the

movement, in which facilities may be found for carrying on all kinds

of work for the spread of co-operative ideals. On May 12th, 1908,

more than the sum asked for had been promised, societies totalling

2,332,754 members having undertaken to contribute £24,667.

The last rites were observed at the Crematorium at Golders Green on

Saturday, January 27th, 1906, and every public movement with which

Mr. Holyoake had been actively associated paid its tribute of

respect. A memorial sermon preached by the Rev. Dr. Clifford

described Mr. Holyoake as a soldier of freedom, one fitted to take

his place in the great company of the prophets of freedom and the

apostles of liberty. He (the preacher) had no hesitation in placing

him in the ranks of that great succession where they found Moses,

who led the people into the land of promise, and of Judas

Maccabaeus, with the hammer of God that broke in pieces the tyranny

of monarchs. He was in line with English leaders Alfred, who

fought against the oppression of the Danes, and Cromwell, who fought

against tyranny in the name of religion. He had freed the press; he

was a soldier of liberty. Joseph Cowen had said, with reference to

the people who talked glibly about his religion, that he knew

Christian people who would not go across the street to help another,

but that Mr. Holyoake would go to any trouble to do a kindness. In

fact, he was a much better Christian than many who made a loud

profession of religion. "By their fruits ye shall know them."

|

Thou glorious Titan, art thou gone at last?

Shall the embattled peal thy name no more?

Must the majestic spirit that of yore

Made thy young heart a home be now outcast?

Ah, never! with thy passing hath not passed

The Truth eternal that thou suffer'dst for.

Never again shall clang the iron door

Thy bleeding hands thrust open and held fast.

Servant of man, well done! The great unborn

Shall thunder forth thine honour in that light

Whose radiant and unutterable morn

Thy life hath hastened over Freedom's night.

And o'er the upward pathway thou hast worn

Thy steadfast name shall blaze, a star of might.

EDEN

PHILLPOTTS,

in the Tribune.

February, 1906. |

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

CO-OPERATION PRIOR TO 1859.

MR.

HOLYOAKE defines

co-operation as "voluntary concert, with equitable participation and

control among all concerned in any enterprise." As the same author

says, it has been common since the commencement of human society in

the sense of two or more persons uniting to attain an end which each

could not attain singly.

Mr. Owen had pointed out that one oven might suffice to bake for a

hundred families with little more cost and trouble of attendance

than a single household involved, and set free a hundred fires and a

hundred domestic cooks. Co-operative laundries were unknown in his

days, but he suggested that one commodious wash-house and laundry

would save one hundred disagreeable, screaming, steaming, toiling

wash days in the homes of the people. And so could one large shop

supersede twenty smaller shops and effect an enormous saving in

administration.

As a result of Robert Owen's activities many societies, originally

called union shops, were formed. At the end of 1820 the number of

societies was 130; in 1831 they had increased to 250; and two years

later there were 400. They divided profits, not according to

purchases, but as interest on capital. The first co-operative shop

known in England was that of a tailoring society in Birmingham in

1777, and the second a store at Mongewell, Oxfordshire, in 1794.

Amongst others, in a list of early societies and their dates of

establishment, the following local names appear: Ashton, 1838; Broadbottom, 1831; Hyde, between 1830 and 1833; Macclesfield, 1829;

Mottram, about 1830; Mossley, about 1830; and Stockport, 1839.

Most of the 400 societies referred to went out of existence, some

for want of legal protection against unscrupulous members, others

from the apathy of members and the fact that working people had not

acquired the habit of association. The Combination Laws,

consolidated in 1799 and 1800, regulated the price of labour and the

relations between masters and workmen, and prohibited the latter

from combining for their own protection. They were repealed in 1825.

It was left to the Rochdale Pioneers in 1844 to inaugurate a new

era. The principle of dividend on purchases was in operation with a

society at Meltham Mills, near Huddersfield, as early as 1827. It is

also claimed to have been recommended by Mr. Alexander Campbell at

Glasgow in 1822, and at Rochdale in 1840. It is believed, however,

that the idea was separately originated by Mr. Charles Howarth, one

of the 28 pioneers of Rochdale.

A few days before Christmas, 1843, a few poor weavers, out of work

and almost without food, met to discuss their condition and to make

an effort to better it. They would become merchants and

manufacturers on their own account. A subscription list was handed

round, and a dozen of those present promised a weekly contribution

of 2d. each. Three collectors called at the homes of the members for

the subscriptions, walking miles for the collection of a few

shillings. Other meetings were held; it was decided to open a

co-operative provision store, and their society was registered as

the "Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers" on the 24th October,

1844. The ground floor of a warehouse in Toad Lane was taken; Mr.

William Cooper was appointed cashier his duties were very light at

first, says Mr. Holyoake, and Mr. Samuel Ashworth became salesman. The stock consisted of infinitesimal quantities of flour, butter,

sugar, and oatmeal, of a total value of about £14. On the 21st

December, 1844, they commenced business. A few of the co-operators,

continues Mr. Holyoake, had clandestinely assembled to witness their

own dιnouement and there they stood, like the conspirators under Guy

Fawkes in the Parliamentary cellars, debating on whom should devolve

the taking down of the shutters. One bold fellow rushed at it, and

in a few minutes Toad Lane was in a titter, the "doffers"

ventilating their opinions at the top of their voices and calling

"Aye! th' owd weavers' shop is opened at last." A few women went in

to ask for things they knew they could not get, just to look round

and be able to report to others on the commodities for sale and at

the bareness of the shelves. It was declared that the shop would not

be open a week.

But those pioneers had their reward. It remained open, and soon they

were in a position to pay interest on capital and dividend on

purchases. To what great things has that two-penny subscription led. From that timid beginning they have gone on until their members

number 16,000, with a share capital of £314,000. They employ 370

people, pay £23,000 a year in wages, and their sales for a year

amount to £350,000.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV.

THE COTTON FAMINE.

|

There's a moan on the gale, there's a cry in the air,

"Tis the wail of distress, 'tis the sigh of despair;

All silent and hushed is the factory's whirl,

And famine and want their black banner unfurl

Where the warm laugh of childhood is hushed on the ear,

And the glance of affection is met by the tear;

Where hope's lingering embers are ready to die,

And utterance is chok'd by the heartbroken sigh.

From " A Visit to Lancashire in December, 1862,"

By ELLEN

BARLEE. |

THE supply of

cotton from North America nearly ceased in consequence of the

secession of the Southern States from the Union in 1860-61. At the

beginning of the latter year the prospect seemed to the operatives

so bright that they pressed for an advance in wages. In March there

was a turn-out of weavers at several mills. Somewhat suddenly the

American Civil War broke out, and at once it was realised that the

mills must close for want of cotton unless the war came to an end

soon. The weavers returned to work after a brief struggle, but the

war continued and the mills were run short time. Some were closed

altogether, and the operatives, with aching hearts, became unwilling

recipients of relief. "Short commons and long faces," said one, were

his recollections of the "panic." "I wur nobbut a lad at th' time,

but I'd a lad's keen feelin's, especially in certain vital parts. I wur punced through th' panic, I wur."

So scarce did employment become that in the winter of 1862-3 nearly

7,000 of 11,484 operatives usually employed were out of work, and a

large number of those employed were on short time. Of 39 cotton

manufactories, 24 foundries and machine shops, and three bobbin

turning shops in the town, only five were employed full time with

all hands; 17 full time with a reduced number of hands; 34 on short

time; and seven were stopped. A gigantic system of relief was

organised in the town, and it is said that more than three-fourths

of the population became dependent. The cotton operatives were not

so well organised as now, and what little they had saved was soon

exhausted. Contributions of money, immense quantities of clothing,

and cloth for making up flowed in from all parts of England. To

provide food for the distressed people orders on grocers in the town

were issued. To clothe them the garments received from various parts

were distributed, and the tailors of the town were employed by the

relief committee to make up the cloth. When that work was done many

of the tailors went to the workhouse, some to repair the clothing of

the inmates, and some to become inmates themselves. The Rev. Mr. and

Mrs. Hoare started a school in the Albion Mills, employing a tailor

to teach the men who attended to mend their own clothing. Another

considerate action of Mr. Hoare's was to forego his fees for

marriages solemnised at St. Paul's. Mr. James Buckley, of Buckley

and Newton's, was a generous helper. It is said that he told the

people, "You'll never starve so long as you have plenty of bacon and

potatoes," and he gave large quantities of those comestibles. About

the beginning of 1863 our society distributed quantities of stew

from the butchering department.

Mr. B. Worth had the shop at the end of Castle Street. On one

occasion a mob of half-famished people went for it, but Mr. Worth

was prepared. He announced that if they would come at ten o'clock

the next morning he would distribute 200 loaves. The crowd passed

on; at the appointed time the loaves were thrown from the windows

and caught by the people.

Sewing schools were opened for the women and girls, who were paid

for attending, and instructed in dressmaking and other sewing work

each afternoon, and in ordinary school subjects in the morning.

These are referred to in Sam

Laycock's "Sewin' Class Song"

|

Come, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing;

It's no use lookin' sad;

We'll mak' our sewin' schoo' to ring,

An' stitch away like mad.

We'll try an' mak' th' best job we con

O' owt we han to do;

We read, an' write, an' spell, an' keawnt,

While here at th' sewin' schoo'.

Sin th' war began, an' th' factories stopped,

We're badly off, it's true,

But still we needn't grumble,

For we'n noan so mich to do;

We're only here fro' nine to four,

An' han an hour for noon;

We noather stop so very late,

Nor start so very soon.

|

One rather humorous local incident may be remembered by some

readers. Mr. Bates' mill in Castle Street was used as one of the

relief stores. A man stationed at the door for the purpose of

regulating the applicants had a way of issuing the command "Hook

it!" to any applicant who became importunate. The expression stuck

to the man the rest of his life, and after his death people were

asked, "Do'st know 'Hook-it's' dead?"

Another, a retired army sergeant, marched out numbers of the

unemployed men and put them through exercises; anything to keep them

occupied.

The decision of the relief committee to issue tickets instead of

money resulted in the "Bread Riots." The great excitement commenced

on the morning of Thursday, March 19th, 1863, when the executive

committee sent word to the schools that relief would be given by

ticket at the rate of 3s. a week, but that a day in hand would be

kept. The scholars objected. They contended that they ought to

receive their "wages" in money and to the full amount, or attend

what they termed the labour test certain hours per week less. The

tickets were refused, and a vast crowd congregated around Castle

Street Mill. The windows of a cab in which Mr. Bates and Mr. J. Kirk

were riding had its windows smashed, portions of the mill machinery

were broken, and missiles were thrown at the police, who had turned

out under the superintendence of Mr. Wm. Chadwick, chief constable. The officers were quite overpowered by the mob, which numbered

hundreds. Much damage was done to shops in Market Street,

particularly those occupied by Mr. Brierley, the druggist, and Mr.

Dyson, the eating-house keeper, and the shopkeepers were soon busy

putting up their shutters. The animus of the mob seemed to be

directed, however, toward the more prominent members of the relief

committee. At Mr. Bates' house, in Cockerhill, windows were broken

and many valuable pieces of furniture destroyed, even young women

joining in the wanton destruction. From there the mob turned again

to Market Street, Melbourne Street, and Caroline Street. Every

window of the Central Relief Committee rooms in Melbourne Street was

smashed. At the shop of Mr. Ashton, another member of the relief

committee, bottles, canisters, and groceries were thrown about and

destroyed savagely. There was also an onslaught on our society's

drapery department in Caroline Street, but the mob desisted when it

was found that the shop was not Mr. Ashton's property. Two adjoining

shops were used as relief stores. They were quickly broken open, and

a scene more disgraceful perhaps than any other enacted. Piles of

clothing and cloth were hurled out of the upper windows to the

people in the street.

A cry was raised that the soldiers were coming, but amidst laughter

from the mob it was declared to be only a woman in a red cloak, and

the work of destruction went on, several things being wantonly set

on fire, until, a little after half-past five, a company of the 14th

Hussars from the Ashton Barracks, under the command of Captain

Chapman, appeared in sight. The soldiers galloped along flourishing

their swords, and every one in the crowd looked to his or her

personal safety. Some of those still in the store, in attempting a

hasty retreat, fell at the entrance; others behind were thrown upon

them, and there the people lay, five or six deep, male and female,

when the soldiers reached them. The police were almost as soon as

the Hussars, and some who had created such havoc were easily

captured. Amidst the hooting and yelling, Mr. D. Harrison read the

Riot Act, and the troops proceeded to clear the streets. To escape

detection some of the plunderers burned the clothing; others threw

it into

the canal and the river Tame, and various articles of wearing

apparel could be seen for some time floating on the water. Special

constables were sworn in, armed with sabres, and arrangements were

made for the calling in of fifty of the Cheshire police force should

their services be required. Under the protection of the military the

police visited certain parts of the town, where they found large

quantities of the stolen clothing, and many more people were taken

into custody. At 10 o'clock the soldiers were called off and the

town was left to the guardianship of the police and special

constables. When the prisoners were brought before the magistrates

they were admonished by Mr. David Harrison (chairman) and Mr. John Cheetham.

It was a most disgraceful thing, they were told, that

after so much had been done for the people the benefactors should be

turned upon and abused as they had been. Mr. Bates, for instance,

had opened his door to the people, and this was the return they had

made for his kindness. He (Mr. Cheetham) had been speaking publicly

in London, within a fortnight, of the high character he thought they

had won for their patience and forbearance under their trials. He

felt it deeply; he felt that they had not only alienated the people

at a distance, but had disgraced the town. Many of the prisoners

were committed to Chester for riot. There was further resistance to

the police and military when two omnibuses appeared for the purpose

of conveying the prisoners to the railway station to take train for

Chester, brickbats and other missiles being thrown. The people vowed

that they would have something to eat before they went to bed, and

would "clem" no longer. Prisoners to the number of 29 were placed in

a separate railway carriage and left the station amidst loud

cheering. Twice the cavalry rode through the mob, creating the

greatest consternation, and a company of infantry marched the

streets with fixed bayonets, but little personal injury was done. On

one or two occasions blood was drawn; the sight of it had a great

effect on the crowd, and order was restored.

In the spring and summer of 1865 a few more hands were employed in

the mills. When the panic was at its height there were, it is said,

730 houses and shops empty, and in October, 1866, there were still

620. It was estimated that before the panic had lasted two years

about 1,000 persons had emigrated, and from 1861 to 1866 the

population had decreased by 2,000. At the height of the distress

there was the extraordinary spectacle of 84 persons emigrating to

Australia in a body, headed through the town by a band of music,

with flags flying and thousands of people cheering.

Mr. William Cooper, referred to elsewhere as the first cashier of

the Rochdale Pioneers, wrote to Mr. Holyoake that Stalybridge,

Ashton, Mossley, Dukinfield, Hyde, Heywood, Middleton, and

Rawtenstall had suffered badly, being almost entirely cotton

manufacturing towns, but that none of the stores had failed, so

that, taken altogether, the co-operative societies in Lancashire

were as numerous and as strong after the cotton panic as before it

set in. Mr. Cooper wrote of Manchester at the same time rather

contemptuously, that it was good for nothing then except to sell

cotton. Bnt even Manchester, he said, had created a Manchester and

Salford store, maintained for five years an average of 1,200

members, and made for them £7,000 of profit. What would Mr. Cooper

think now, we wonder, of the same Manchester and Salford store, with

its 18,000 members?

In 1852 Mr. T. Bazley warned the country of the danger of trusting

to America alone for cotton. In I857 there was formed the Cotton

Supply Association, with our townsman, the late John Cheetham, M.P.,

as president. The scheme had its inception in the fears of a portion

of the trade that some dire calamity must sooner or later overtake

the cotton manufacture of Lancashire if it were left to depend upon

the treacherous foundation of slave-labour as the main source of its

raw material. The association established agencies in various

countries, and distributed large consignments of cotton seed and

preparatory machinery, but the scheme did not meet with the support

it deserved.

In May, 1862, Mr. Bazley stated that through the failure of the

American supply the loss to the labouring classes was £12,000,000 a

year, and estimated the loss including the employing classes at

nearly £40,000,000 a year. In the Lancashire district population

about 4,000,000 there were receiving parish relief, September,

1861, 43,500 persons; in September, 1862, 163,408. The Union Relief

Act, passed August, 1862, gave much relief by enabling overseers to

borrow money to be expended in public works executed by the

unemployed workmen. In October, 1864, much distress still existed,

and fears for the approaching winter were entertained. At that time,

it was stated in the Times of 18th January, 1865, there were 90,000

more paupers than ordinary in cotton districts. In June, 1865, a

special commissioner appointed in May, 1862, was recalled by the

Poor Law Board, and the famine was declared ended. £1,000,000 had

been expended in two years. The executive of the central relief fund

held their last meeting on the 4th December, 1865.

――――♦――――

PART II.

CHAPTER I.

THE START AT STALYBRIDGE.

|

F.R.S. and LL.D.

Can only spring from A B C.

Eliza Cook. |

WHAT is described in the society's records as the preliminary

meeting was held on the 7th March, 1859, but Mr. Charles Wright, of

Manchester and Salford Society, carries us back six days to the

first of that month. He points out that the Co-operator, a monthly

journal of the period, of August, 1860, gives an account of a

meeting on the earlier date. Eleven persons were present, and they

met "to discuss the practicability of opening a store where the

working man's wife might purchase with safety and advantage those

articles of consumption which are daily required in the homes of

working men." A copy of the rules of the Rochdale Pioneers was sent

for and adapted to local circumstances.

On the first meeting night twenty-two £1 shares were taken up. No

names are given, and there is some uncertainty as to the identity of

those present; but what appears to be the first share ledger has

been traced, and it shows that the numbers 1 to 22 were allotted as

follows :

|

1 Alexander

Maxwell |

12 Henry Bradley |

|

2 Ambrose

Jackson |

13 John Shaw |

|

3 Dan Woolley |

14 Jonathan Blacker |

|

4 John Peacock |

15 Charles Rodgers |

|

5 Thomas Baxter |

16 Jerry Ratcliffe |

|

6 Thomas Phillips |

17 Joseph Woolhouse |

|

7 Charles Gaskill |

18 John Dearnaley |

|

8 William Haynes |

19 John France |

|

9 Henry Pool |

20 Devenport Davis |

|

10 Joseph Edgar |

21 John Holding |

|

11 Johanan

Booth |

22 Hiram Ratcliffe |

Following these, there were admitted as members :

|

23 John Bradbury |

46 William Simpson |

|

24 William Harrison |

47 Benjamin Hurst |

|

25 Thomas Ellis |

48 Henry Sheppard |

|

26 Thomas Hornby |

49

Joseph Swift |

|

27 Thomas Lockwood |

50 Arnold Rowbottom |

|

28 James Heywood |

51 John Whiteley |

|

29 Joshua Allsop |

52 John Beswick |

|

30 John Langford Porter |

53 John Cocker |

|

31 Daniel Marsland |

54 James Haughton |

|

32

Joseph Bailey |

55 Charles Haughton |

|

33 Abel Frederick Wood |

56 John Miller |

|

34 John Hassall |

57 Nancy Hassall |

|

35 Martha Norminton |

58 Joseph Allen, sen. |

|

36 John Holt |

59 Charles Marsland |

|

37 Robert Winterbottom |

60 George France |

|

38 Mary Moss |

61 John Duffy |

|

39 Joseph Allen, jun. |

62 Charles Jones |

|

40 William Greenwood |

63 Edward Booth |

|

41 Joshua Hill |

64 William Campbell |

|

42 James Cook |

65 James Kenworthy |

|

43 William Howarth |

66 William Brougham |

|

44 John Cheetham |

67 Giles Hinchcliffe |

|

45 George Woodhead |

68 Samuel Platt |

| |

|

|

69 Thomas

Jones |

86 Joseph Roebuck |

|

70 John Ridgway |

87 John Marsden |

|

71 Thomas Lee |

88 Henry Clayton |

|

72 Joshua Andrew |

89 Samuel Lowe |

|

73 Joseph Hill |

90 Abraham Lawton |

|

74 William Banton |

91 Bradburn Cocker |

|

75 George Kay |

92 Ratcliffe Buckley |

|

76 John Smith |

93

James Cooper |

|

77 William Lowe |

94 George Barker |

|

78 James Kay |

95 Henry Langley |

|

79 Hugh Kenworthy |

96 John Jones |

|

80 John Thorp |

97 David Hastings |

|

81 Joseph McQuire

|

98 Charles Deakin |

|

82 George Kiddy |

99 Thomas Haslam |

|

83 William Haynes, sen. |

100 Josiah Rigby |

|

84

John Eastwood |

101 James Mitchell |

|

85 James Lee |

102 Samuel Sykes |

There were some alterations of the machine paging of the ledger in

which these names appear, hence there is some uncertainty as to the

numbers; but all the names appear in the order and under the numbers

given, and all are those of members admitted during 1859 and 1860. They are detailed here because they appear to be what may be called

original members, that is, first holders of the share accounts so

numbered.

One of the early share accounts had been closed and balanced,

apparently for withdrawal, and either the member had changed his

mind or it was found that the entries were intended for another

account. For some reason the ledger folio bears the remark, "account

closed wrongfully," and shows that the account was reopened, an

instance of the strong language inadvertently used by some people. Clearly, the book-keeper who wrote the remark meant, not that a

wrong had been done, but that there had been a slight error.

The first minute book is still in existence, and it is recorded that

the following resolutions were carried at the meeting held 7th

March, 1850:

1. That the shares be £1 each, and that the subscription be 1s. per

week.

2. That no member have less than one share, nor more than five

shares;

3. That Johanan Booth be treasurer and Thomas Baxter secretary for

the time being.

4. That the contributions be brought to the house of James Cook

every Monday fortnight, betwixt the hours of seven and nine of the

clock.

5. That every member who is six weeks in arrear be fined threepence,

and if three months in arrear be excluded, except sufficient cause

be shown to the committee why they or he should not.

6. That the following members form the committee: Charles Gaskill,

Daniel Woolley, Ambrose Jackson, William Haynes, Alexander Maxwell,

Joseph Edgar.

7. That 1,000 handbills be printed, and that A. Maxwell and Thomas

Phillips see that they be printed.

8. That the committee meet on Wednesday night, March 9th, for the

purpose of drawing up a handbill for delivery among the public.

(Signed) THOMAS BAXTER, Secretary.

JOHANAN BOOTH, Chairman,

There were also present at this meeting Henry Pool and John Peacock. Thus, assuming that the others named in the resolutions six

forming the committee, and Messrs. Booth, Baxter, Cook, and Phillips

were all present, there would be a total attendance of twelve

persons.

Other members admitted during 1859 were:

|

John Barmford |

Michael O'Donnel |

|

Richard Bentinck |

Frederick Brown |

|

George Rainforth |

Betty Dearnaley |

|

Joseph Sykes |

Edward Davis |

|

Henry Dyson |

Augustus Ball |

|

John Crossley |

James Hill |

|

James Hallam |

Ann Chadwick |

|

George Rushton |

John Lyttle |

|

Henry Hurst |

Ben Platt |

|

William Wood |

James Lomas |

|

Harriet Sykes |

Randal Cheetham |

Mr. James Bamford, of Huddersfield Road, became a member in 1859,

before the society was registered. The writer learned from him that

the movement originated at Messrs. Harrison's mill. Mr. Bamford says

the mill and a beerhouse in Harrop Street joined; the latter was the

house of James Cook, referred to in the fourth resolution of the

March 7th meeting.

Mr. Baxter's inquiry for a form of declaration brought forth from

the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers' Co-operative Society a reply

addressed from Nos. 8, 16, and 31, Toad Lane, March 12th, 1859,

offering to get made a declaration and proposition book, arranged to

conform to the Stalybridge rules. Our Rochdale friends had paper

printed and partly ruled ready for the making up of such a book. They had also a wholesale department for supplying goods to other

societies. In a letter dated May 25th they expressed pleasure at the

progress-making at Stalybridge, and thought business might be

commenced in a small way before November or December. Many of the

letters at this time were addressed to Mr. Baxter, 30, Wakefield

Road, Stalybridge.

At the meeting held March 9th, 1859, the secretary was instructed to

write to Rochdale for a form of declaration to make members, and was

empowered to buy the books that were necessary to record the minutes

and to keep the accounts. The entrance fee was fixed at one shilling

per share.

The first general meeting was held March 21st, 1859. John Bradbury,

John France, and Johanan Booth were elected trustees, and William

Haynes and Joseph Woolhouse money stewards. At the same meeting it

was resolved that any officer being absent after 7 o'clock on any

meeting night be fined three-pence, to go to the

incidental expenses fund.

At a meeting held April 4th, 1859, a committee composed of John

France, Charles Rodgers, Thomas Ellis, Jonathan Blacker, Thomas

Hornby, and James Heywood was formed to revise the rules. Three days

later the contribution was reduced from a shilling to sixpence per

week, and it was decided that dividend on purchases should be paid

to non-members. On the 21st April it was resolved that a member be

allowed ten shares instead of five, and on the 9th May this was

further extended to twenty shares. At the same meeting Johanan Booth

was authorised to take up five shares of the Rochdale Corn Mill

Society, and the rules passed by John Tidd Pratt, Esq., Registrar of

Friendly Societies, were adopted. The Registrar's certificate reads

"I hereby certify that these rules are in conformity to law and to

the provisions of the Statute 15 and 16, Vict. c. 31, relating to

Industrial and Provident Societies.

"JOHN TIDD PRATT,

"The Registrar of Friendly Societies

"Copy kept. in England.

"J. Tidd Pratt. "9th June, 1859."

Premises in Water Street, then in the occupation of Mr. Joshua

Crowther, were taken on the 16th May, 1859, and in September Messrs.

France and Edgar were appointed to go to Mr. Crowther to bargain for

whatever he might have to dispose of that would suit the purposes of

the society. It was decided that the words "Stalybridge Co-operative

Stores, enrolled under Act of Parliament," should be painted on the

sign.

The first record of the election of officers after the society was

established in Water Street is dated 23rd June, 1859. Thomas Baxter

was appointed secretary for twelve months, and the following

gentlemen were elected to other offices for the same period:

CommitteeJoseph Edgar, Thomas Ellis, Charles Gaskill, Joseph Woolhouse, Daniel Woolley, James Heywood, Jonathan Blacker, Joseph Allen, and John Langford Porter.

Auditors Alexander Maxwell and Joshua Allsop.

Trustees John France, Abel Frederick Wood, and James Cook.

Treasurer Johanan Booth.

Money Stewards Robert Winterbottom and Joseph Bailey.

At this meeting there were also appointed five Arbitrators:

Matthew Hutchinson, Tom Milburn, Frank Farrow, Robert Whitehead, and

Nathan Pickering.

The first reference to remuneration of an officer is under the date

November 17th, 1859, when the secretary's salary was fixed at

twenty-eight shillings per quarter as from November 1st. Some months

later the treasurer's salary was fixed at £5 per annum, and the

persons who took stock were to have sixpence each for their trouble.

In June and July, 1859, there were resolutions admitting "as fit and

proper persons to be members of this society," Benjamin Hurst, Henry

Sheppard, Joseph Swift, William Simpson, George Woodhead, Arnold

Rowbottom, John Whiteley, and John Beswick.

It is probable that about this time useful information was obtained

from Rochdale and other towns. Johanan Booth was requested to "make

a bill of his expenses to and from Rochdale," and it was resolved

that all the books of account be purchased from William Cooper, who

was the first cashier appointed by the Rochdale Pioneers.

James Heywood was appointed to go to Rochdale to glean whatever

information he could from the store-keeper there, Charles Gaskill

and Joseph Woolhouse to go to Dukinfield and Mossley to get

information respecting their mode of conducting business, and

Johanan Booth was appointed to represent the society at Mossley

Society's tea party, which was held on Saturday, February 18th,

1860.

Our pioneers were evidently for a time dependent for fixtures and

utensils in trade on the former tenant of the shop, for it was

resolved "That we put ourselves in a state of independence as

regards shop fixtures, and that Joseph Edgar and Johanan Booth are

engaged by this committee (with power to add to their number) to

make all the shop fixtures that are required. That we have baywood

tops to the counters." About the same time Messrs. Heywood, Gaskill,

and Ellis were deputed to go to Manchester to purchase scales,

weights, canisters, &c., and they were to take a few pounds with

them to be left on articles as deposits. Later, Frank Farrow was

sent to convey the scales, &c., to Stalybridge, and he was to take

the money to pay for them. A vote of thanks to Mr. Ellis was passed

"for his exertions on behalf of this society at Manchester in

getting discount off the articles bought at Sutcliffe's, canister

manufacturer."

On the 12th September, 1859, it was decided to advertise in the

Ashton Reporter, Ashton Standard, and a Rochdale paper for a shopman, and that the security to be given by the shopman should be

"£100 or two fifties." On the 22nd that portion of the resolution

referring to insertion in a Rochdale paper was rescinded. The

committee met October 11th to select a shopman from the applicants,

and James Hyde was appointed at "26s. per week and sleeping room." It was arranged that he should commence his duties on the 31st

October, and the trustees were asked to look to the shopman for his

security. The "£100 or two fifties" was not forthcoming, and it was

decided that the matter be referred to a guarantee society, the

premium to be paid by the employers until the wages of the employed

had been reconsidered. This reconsideration took place in January,

1860, and the remuneration was increased to thirty shillings per

week and four shillings for expenses. Mr. Hyde and Mr. Baxter, the

secretary, were to go together "to buy good groceries for and on

behalf of this society," and William Leech was offered a situation

as assistant at twelve shillings per week for a month. It appears

that Mr. Hyde lent money to the society, for in January, 1860, there

was a resolution authorising payment to him of £1 for interest on

money used for the society's purposes during the previous quarter.

It is evident, too, that Mr. Hyde gave good service, and that the

committee appreciated. On the 9th February, 1860, there was a

resolution "That James Hyde have a vote of thanks from this

meeting for the efficient manner in which he has discharged the

duties of his situation during the past quarter."

In October, 1859, there was passed a resolution that the treasurer

for the time being be allowed to sit on the committee and to vote on

any question under discussion. At the same meeting it was resolved

"that we have checks" the first reference to the method of keeping

account of members' purchases and the quantities of checks to be

bought were 4,000 pence checks, 2,000 shilling checks, and 1,000

copper checks, with a set of figures. About the same time it was

decided that any person buying wholesale at the store, whether a

member or not, should not have checks.

A minute penned on the 27th October, 1850, is somewhat problematic. It was resolved "That we keep the first quarter's dividend among

ourselves." At first thought, this savours of a summary method of

distributing the profits, but it may be that the resolution

indicates merely a determination not to disclose details to

outsiders by publication. During the same month the secretary was

instructed to write to Joseph Clarkson, tea dealer, Huddersfield,

requesting him to send his representative with samples.

It appears that during the very month in which the Stalybridge

Society commenced business indeed, a few days before the shop was

opened amalgamation with the Dukinfield Society was suggested. It

was decided on the 2nd November, 1859, that the matter be laid

before the general meeting, and a vote of thanks to the Dukinfield

Committee was passed; but, so far as the writer can gather, there

was no development of the scheme.

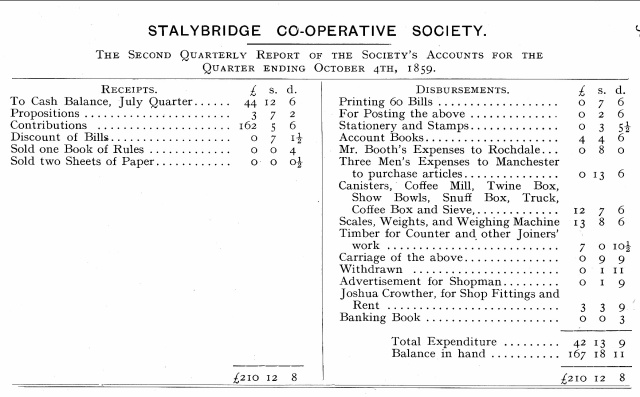

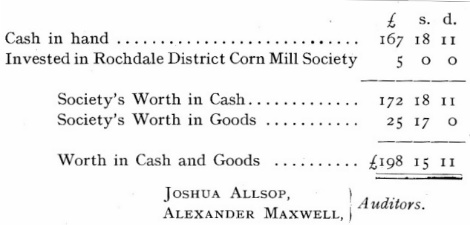

The first report of the committee has not been traced, but the

second, pen-written, is in existence and is as follows:

Even at this early stage the committee had such confidence that they

decided on the 10th November, 1859, to take the shop on a lease for

fourteen years. There were some willing helpers at shop-fitting and

in other directions. There was a vote of thanks to Mr. John Miller

for the valuable services he had rendered the society in lending men

and tools, and another to the joiners for the complete manner in

which they had fitted up the shop and for their usefulness

generally. A few months later one member, who had £5. 0s. 9d. to his

credit, found it necessary for some reason to withdraw. He withdrew

the pounds; the share ledger bears the remark opposite the balance

of nine-pence "Presented to reading room." Every little helps, and

doubtless the spirit that prompted the presentation of that

nine-pence was appreciated.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

THE OPENING IN WATER

STREET.

|

Think naught a trifle, though it small appear;

Small sands the mountain; moments make the year;

A trifles life.

Young. |

BUSINESS in Water

Street was commenced on the 11th November, 1859. The writer's

father remembers, as a tradesman, how the shopkeepers received the

news. They said: "They're startin' a co-op.; we me't as well shut

up." There was a capital of £210, held by 139 members. The opening

proved a great success, for at the close of the first week £84.10s.

2½d. had been taken over the counter. Thomas Ellis was deputed to

go to Richard Bentinck to get information respecting insurance

premiums, and in December it was decided that the stock of groceries

be insured in the Sun Fire Office for £500.

From insurance the deliberations passed to pork, and it was resolved

"That Johanan Booth buy Edward Stanley's pig for this society." At

another meeting it was decided that no New Year gifts be granted to

members or others. At this time there were to be printed 2,000

copies of a notice and two dozen notice cards, the cards to announce

that members must bring in their rule books and checks not later

than the following Saturday, and Samuel Harrison was to have the

preference for the printer's work if he could complete it in time.

At this early period, too, butchering was essayed, and a

sub-committee formed to look out a site or a building for a

butcher's shop and slaughter-house. The result of the inquiry was

that there was taken a shop "at the top end of Caroline Street" for

the sale of butcher's meat, and a slaughter-house belonging to the

Foresters' Society in Vaudrey Street. The butchering utensils of

Henry Dyson and George Kay were bought, and Arnold Kay was appointed

butcher to the society on the 3rd April, 1860, at a weekly wage,

together with house and gas free. The gas-fitting in the shop was to

be done by James Smith, if he could do it in time. At the same time

the making of a hand-cart was placed in the hands of Frank Longden,

and the painting and sign-writing was entrusted to Oliver N. Gatley,

who was in business in Grosvenor Street where the Central premises

are now situated.

At this time a dividend of 9d. per £ was declared, and it was

decided that the report should be printed. Three hundred copies were

to be obtained, and the printer's work was done by H. and S.

Burgess, of Stalybridge and Ashton. During the same year other

printers' work was placed in the hands of Mrs. Cunningham. There was

an effort to find work for the members, a resolution being passed

"That the carriage of goods for the store be divided amongst the

members alone, as far as possible."

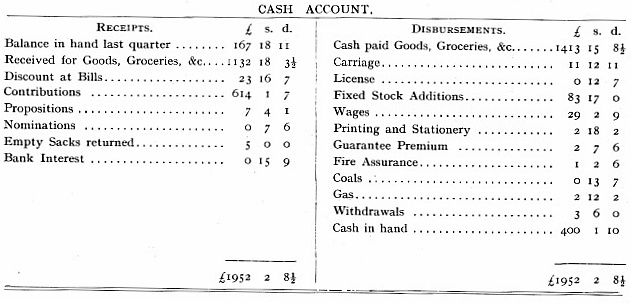

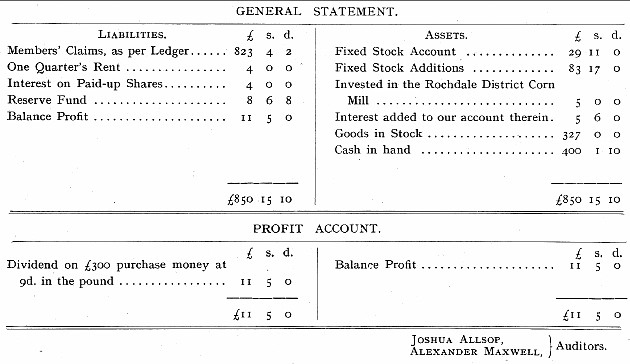

From the day of opening in Water Street to the end of the quarter

the society's third quarter, but the first open for the sale of

goods members increased daily, and the total sales were £1,132.

18s. 3d. It appears, however, that consumers were not entitled to

dividend on the whole of this, as a dividend at the rate of 9d. per

£ was declared on £300 only. The profit on some articles was

precarious. On sugar, for instance, no dividend was paid. The report

and accounts were as follows: |

|

THE STALYBRIDGE INDUSTRIAL CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY.

THE THIRD QUARTERLY

REPORT OF THE ACCOUNTS OF THE

SOCIETY FOR THE QUARTER

ENDING

JANUARY 31ST, 1860.

Your committee feel great pleasure in issuing this their

third quarterly report, showing the progress that has been made

during the last quarter, and taking into consideration the

difficulties that we have had to contend with feel assured that our

efforts have not been in vain; the committee wish to impress upon

all the members the necessity as far as practicable of dealing at

the Society's store, being convinced that it is the only the source

from whence profit will accrue to the members.

Your committee has great pleasure in being able to give

nine-pence in the pound on members' purchases this quarter, the

first quarter that the Society's Store has been open, and hope and

trust that the spirit of co-operation will cause each and all of the

members to have that zeal and confidence in the society which cannot

fail to have good results.

|

|

Some

of the early resolutions go into detail, and in others quaint

expressions are used. One on the 6th March, 1860, reads "That the

shelves required in the shop be put up, and that a saw be bought for

the use of the shopman to saw bones." Another on the same date is

"Moved by Charles Gaskill, seconded by Cook James vice versa,

that the Act of Parliament relating to Friendly and Provident

Societies be bought." Another resolution appointed two members of

the committee to go to the Temperance Room to look at some forms on

sale there, and if they thought the articles worth the price, they

were to buy them. Still another reads "That there be two books

provided for the store, one to be called the petty cash book and the

other to be called the inventory book, to put all the articles in

that belong to the society;" and another "That any member can have

his money at sight if there is cash in hand that will pay him,

unless the money be wanted for some uses of the society more

urgent." Not all the resolutions are so explicit, however. One reads

"That one thousand summonses be obtained," but it is not stated

whether they were summonses to a meeting or to a Court, nor on whom

they were to be served.

A sub-committee was appointed to look out a room for the society to

hold its meetings in, and on the 12th April, 1860, the Foresters'

Hall, in Vaudrey Street, was taken for the purpose. About the same

time there was taken a room in the Angel Inn yard, belonging to

James Wilson, at the yearly rent of five guineas. A dozen forms were

to be made, and Joseph Edgar was to buy the table of John Marshall

for the room. Mr. W. Evans (once a member of the Stalybridge Town

Council), who became a member of the society about October, 1859,

remembers that the room was used as the society's office, whilst the

Water Street shop was still used for sales. He has a lively

recollection of the long queue waiting to pay share contributions

and take up their books. Mr. Evans' first share book is still in his

possession.

In April, 1860, a sub-committee was appointed to inquire about the

shop of Butterworth's in Caroline Street, with a view to taking it,

if suitable, for drapery. On the 17th April, John Marshall was

appointed to fit up for drapery the shop No. 58, Caroline Street,

and William Lowe was engaged to clean it. An advertisement was

inserted in the Manchester Guardian on the two following Saturdays,

April 21st and 28th, for a "shopman draper," he was to be a married

man and give security in £100. The remuneration was fixed at 26s.

per week for the draper himself and 8s. per week for his wife. Four

of the applicants were invited to meet the committee, their

references were investigated, and on the 8th May James Frederick Keeley was appointed, to commence his duties on Monday, the 14th

May, 1860. The committee restricted him in his buying to three

wholesale houses, those of Messrs. S. and J. Watts, Messrs. Thorp

and Son, and Messrs. J. and N. Philips. The stock and fixtures were

shortly afterwards insured for £500 with the Sun Fire Office. Mr. Keeley was not long employed. On the 19th July, 1860, a Mr. Edwards

was appointed draper, but the resolution was rescinded at the next

meeting, and it was left to Mr. Hyde, who was appointed general

manager at the same meeting, July 26th, to inquire for a draper. At

this point there is a gap in the records. The minutes from 1860 to

1865 are missing. It is known, however, that Miss Hampshire was

employed in drapery in Caroline Street, and was still in the

department when it was removed to Grosvenor Street; she followed

Mrs. Rowbotham, wife of Mr. Henry Rowbotham, who was manager after

Mr. Hyde left.

A general meeting for the election of officers was held in the

Foresters' Hall, Vaudrey Street, on the 1st May, 1860, and the

following were elected:

Committee Thomas Ellis, Charles Gaskill, Daniel Woolley, Joseph

Edgar, Joseph Allen, Joseph Woolhouse, George Kay, Alexander

Maxwell, and James Heywood.

Trustees John France, James Cook, and Robert Marsland.

Stewards Joseph Bailey and Robert Winterbottom.

Auditors Joshua Allsop and Bradburn Cocker.

Treasurer Johanan Booth.

Secretary Thomas Baxter.

Arbitrators Matthew Hutchinson, Tom Milburn, Nathan Pickering,

Robert Whitehead, and Frank Farrow.

At this time the committee felt justified in employing the secretary

whole time, and on the 10th May, 1860, the resolution passed on 17th

November fixing the secretary's remuneration at 28s. per quarter was

rescinded, and he was appointed at £1 per week to undertake the

duties of secretary and to make himself generally useful. He was

asked to seek the advice of Mr. Occleshaw who was manager of the

Stalybridge Branch of the Manchester and Liverpool District Banking

Company Limited, and on the 17th May it was decided to open an

account with the District Bank. A week later the trustees were

requested to go to Mr. Noah Buckley, attorney, to have prepared an

indenture between the society and Albert Newton, butcher's

assistant, and on the 31st May it was arranged that the trustees

should go to Mr. Wilson, Butterworth's agent, on the 12th June, "to

see all things settled and right as regards the drapers' store and

the stable behind for a slaughter-house."

In June the same year it was resolved that one share be taken up in

The Co-operator newspaper, published by the Literary

Committee of the Co-operative Society, Great Ancoats Street,

Manchester. It is evident that the committee's attention to detail

was great, for there was a resolution penned the same month that

there be a slate bought for the use of the secretary, and another

that a large ledger be bought for the purpose of keeping account of

members' investments. There is here what appears to be the first

reference to the occupation of Grosvenor Street premises, Mr. Hyde

being instructed to find a man for the branch store there.

At the end of the fourth quarter there were 480 members, and the

number of shares taken up was 1,500, 1,300 of which were fully paid. The committee reported as follows:

We have now in connection with our store a butcher's shop, which

kills weekly an ox, six sheep, one calf, one lamb, and occasionally

a pig; which, considering the high price of flesh meat, we think

pretty good. We have also opened a shop for drapery, which took for

goods sold £34. 10s. the first week, and promises to do well; for

our wives and children are always wanting frocks, bonnets, &c., and

I suppose we men-folks require shirts, &c.

We may just mention that, through the jealousy and interference of

the shopkeepers, and the fear of the landlords, we were nearly two

months before we could get anyone to let us a shop; but these

drawbacks only stimulated us the more when we got one, and we are

now reaping the reward of our labour, for we forgot to mention that

our dividend was 1s. 3d. in the pound, and last week we took in the

grocery shop alone £203. 0s. 3d., to say nothing of the butchery and

drapery.

We are all working men; our treasurer is a joiner, and the secretary

a blacksmith, though we have decided to take the latter away from

the anvil, and put him to the business of our society.

Our committee have decided to take up shares in the company for

conducting your (or we would rather say our) journal; for we think

it is a first-rate affair, and just the

paper that ought to be placed in the hands of every working man. We

may say, in conclusion, that we intend very shortly inaugurating a

newsroom and library, where

our members can, free of charge, read and converse, and where solid

instruction can be obtained.

Mr. Charles Wright says, referring to this report, that it is very

interesting to find that education was not lost sight of by our

pioneers, and that they believed intelligence was a paying

investment.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

THE FIRST TEA

PARTY.

AT the end of

June, 1860, there was held in the large room of the Foresters' Hall

a tea party, the proceeds of which were to be devoted to the

formation of the newsroom and library just referred to. Upwards of

600 persons sat down to tea, which was amply provided by members of

the society. A brass band was in attendance, and the audience was

delighted during the evening by select pieces of music at intervals. After the tables had been cleared, the Mayor, Thomas Hadfield

Sidebottom, Esq., took the chair amidst enthusiastic applause, and

accompanying him on the platform were Moses Hadfield, Esq., J.P.;

Mr. Abraham Greenwood, of the Rochdale Pioneers' Society; Mr, Edward Longfield,

President of the Manchester and Salford Equitable

Co-operative Society; and Mr. William Marcroft, one of the founders

of the Oldham Industrial Society. It was at Mr. Marcroft's that the

first officially recorded meeting of that society was held.

The Chairman, in opening the proceedings, said he

took the chair with very great pleasure. They were all aware

of the object for which they had met, and therefore it would be

unnecessary for him to go into it. But, with reference

to the co-operative societies in Manchester, Rochdale, and other

places, he could say that they had attained very great success.

The formation of a library and newsroom in connection with the

Stalybridge Co-operative Society was a noble achievement, and he

could assure the audience that he wished the society every success

and prosperity. That was their first meeting, and he hoped it

would not be the last; it was very well attended, and he hoped the

next would be doubly so, and that their gatherings would keep on

doubling. There was nothing more beneficial than to be members

of a good library.

Mr. Hadfield then addressed the meeting. He was glad,

he said, to see the Mayor occupying the chair on that occasion.

He could not be better engaged in his official capacity, nor in a

more worthy cause, for that, in his opinion, was an active endeavour

on the part of the people to improve their condition, and he must

congratulate the meeting on the numerous assembly that evening.

It augured well for the success of the society. The history of

the workers hitherto had been of a varied character, and they had

been subject to many evils; but as society was progressing in the

arts and sciences, the workers apparently were not behind the times.

That there was progress among them there could be no doubt, because

he believed the Stalybridge Co-operative Society was composed of the

most intelligent, the most industrious, and the most careful of the

workers of Stalybridge. There must be progress so long as this

was the case, and it struck him that they must be successful in

their endeavours. That society had only been in existence

about eight months, and it was doing a fair and favourable business,

taking, he believed, about £101 per day. The society had

opened a butcher's and a draper's shop, and each was doing a good

business. But perhaps they owed their rapid progress in

Stalybridge in a great measure to the noble and trustworthy

individuals in Rochdale, who appeared to be the pioneers of the

movement. The people of Rochdale had gone through a great deal

of up-hill work; they had proved the worth and practicability of

co-operation; and he thought too much praise could not be given

them. Mr. John Bright had made the following statement in the

House of Commons a short time before:"The Rochdale Pioneers'

Society was established in 1844, with 28 members and a capital of

£28; at the end of 1859 it had 2,703 members and a capital of

£27,060. It had done a business during the year of £104,000,

and had divided amongst its members a sum of £10,730.

Two-and-a-half per cent of the profits, amounting in the past year

to £300, was deducted for the purchase of books, newspapers, &c.,

for the use of the members' reading-room. The library

contained about 4,000 volumes, and was increasing rapidly every

quarter. There was likewise a Sabbath School attached to the

institution. The working men of Rochdale established a corn

mill in 1850. In 1851 the capital was £2,103, and in that year

it suffered a loss of £421, which sum was made up by subsequent

profits before any division was made. At the end of 1859 the

capital of the corn Mill Society was £18,236, the business done

£85,845, and the profit £6,115. A co-operative manufacturing

society had been established in Rochdale, consisting of 1,600

members with a capital of £50,000." Now, considering the

success which had attended the labours of the Rochdale Pioneers, he

(Mr. Hadfield) did not see anything to prevent the Stalybridge

Society going on in a similar manner. The town was favourably

situated, and the people received as good wages as in any other part

of England; therefore, in the hands of the energetic and hard

working people whom he saw before him, he thought the progress of

the Stalybridge Society might be even more rapid than that of the

Rochdale Pioneers. It was a little over twelve months since

the first eleven Stalybridge co-operators met and established that

society, and they had continued to meet fortnightly up to that time,

and with considerable success. On the 11th November, 1859, the

first store for the sale of groceries was opened. At that time

they had 139 members, with a capital of £210. Since then the

society's progress had been so rapid that it had never been

surpassed, and never, he believed, equalled. The receipts the

first week the store was open were £84. This had increased in

thirteen weeks to £119 for the week, and they were enabled to give

9d. in the £ dividend, with 5 per cent interest on paid-up capital.

At the commencement of the following quarter the number of members

had increased to 247, with a capital of £420, whilst the weekly

sales ranged from £118 to £160. About that time great

difficulty was experienced in obtaining a shop for butchering, and

great credit was due to the sub-committee and a few of the members

who nobly seconded their endeavours. They had now a butcher's

shop where there were sold beef and mutton of a quality not often

met with in that neighbourhood. At the commencement of the

present quarter the number of members was 377, with a capital of

£1,219, and that was increasing rapidly, for, although only two

months were passed, the number of members was 575 and the capital

£2,000. The weekly sales in grocery alone were £250 and with

butchering and drapery added, the amount drawn over the counter at

the present time was £314; a grocer, with one assistant and a man to

weigh flour, actually taking £101 in one day. With such an

accumulation of funds they were obliged to open another store, and a

shop was taken for the drapery business. The shop was stocked

with an excellent assortment of goods, and it was to be hoped that