|

[Previous Page]

SOME FILOSOFY; AN' JOE SHORT'S FUST FEIGHT.

"I WONDER," said

Joe Short,"if bawd yeds is ony relation to midges?"

"What?" I axed, an' as I oppened my meawth i' surprise at th'

question my pipe dropped eaut, an' I swallowed a looad o' smook.

Then I started cowfin' till I were red in th' face, an' I were welly

choked. When I were able to speik, I says, "Whatever dost

meeon, Joe?"

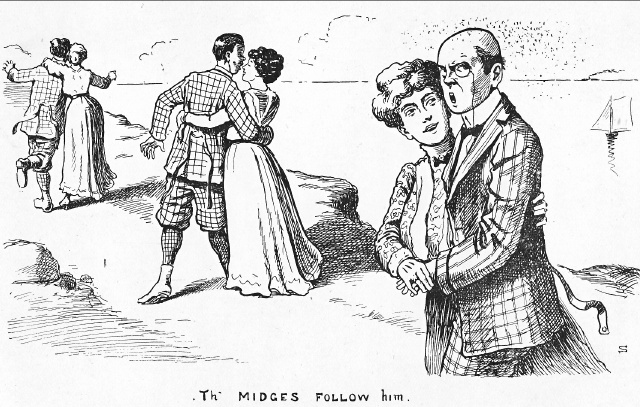

We'd been havin' a walk o'er th' cliffs at Bispham, an' had

getten as far as th' Gynn on th' road back.

"Well, Anoch," he says, "if tha'll not kill thysel' I'll tell

thee. I've noticed that whenever I've walked alung these

cliffs to Bispham I've bin welly blinded by th' midges followin' me,

an' gettin' in my ears an' meawth, an' aw o'er my face. They

were as thick as summer hailstones afore th' rainbow comes.

But there's bin noan abeaut this back end. I seed lots o'

chaps last summer walkin' on th' cliffs beaut hats, dressed in knee

breeches, wi' their legs padded as fat as their yeds, an' there were

some on um as bawd on their nappers as th' top uv a collifleawer.

I've noticed, too, as th' midges followed thoose bawd yeds as far as

they went, an' tickled an' bit their soft places till th' chaps were

fain to turn back to Blackpool, th' midges stickin' to um aw th'

road. An' I were wonderin' if thoose fellies took aw th' breed

on um away fro' Blackpool."

"I durnt know, Joe," I said, "but neaw as tha's mentioned

that, it brings summat to my mind as I were witness on mony a yer

sin'. . . . A day-skoo taycher o' my owdest lass were gettin' wed; I

knowed her an' aw th' family on um by seet, but they didn't know me.

I weren't warkin' that day, an' as I were near th' church when th'

carriages drove up, I went an' watched th' ceremony eaut o'

curiosity.

"Well, I geet in a pew just at th' back uv her parents.

Her fayther had a bawd yed, an' as we were prayin', an' everythin'

were so quiet an' solemn, I yerd a blue-bottle buzzin abeaut, an' in

a minute its buzzin stopt aside o' me. I lifted my yed an'

looked (I couldn't help it), an' it had settled on th' owd

gentlemon's nob, which, as I said, had no yure on th' top. It

were havin' a good tuck in off th' gracey part, as it were a very

hot day. It tickled him, for he slapped his flat hond on th'

top uv his yed, an' it seaunded all o'er th' church. But th'

blue-bottle had gone.

"He pood his honkercher eaut uv his pocket, an' rubbed it aw

o'er his yed, an' he seemed reet then. In a bit I yerd th'

buzzin again, an' th' blue-bottle dropped reet on th' top o'th' bawd

lump. It mun ha' bit him hard, for his hond went slap on th'

spot, wi' a neise like a plank fawin' off a scaffold. An' he

missed it again.

"He were so mad he sit up straight in th' pew, an' I think

he'd blue-bottle-murder in his e'en, nobbut I couldn't see um.

Well, aw were quiet for a bit a short bit when I yerd th' music

once moor, so did th' owd gentlemon, for he'd his hond ready when th'

blue-bottle dropt on th' back uv his yed, an' th' hond coom deaun,

just as we were singin' 'A-men,' wi' a bang on th' blue-un an'

squashed it. That fly were big enoof to ha' bin slaughtered at

th' abattoir. His yed were in a fine mess, an' as he wiped it,

th' skeleton uv his tormentor dropt on his collar, wheer it hung as

if it were danglin' fro' a spider's web. So, neaw as tha's

made me think on it, there may be some connection between midges an'

blue-bottles an' bawd yeds. It's like th' looadstone an'

needle, one draws t'other."

"I'm fain tha agrees wi' me on that p'int," said Joe,

"because it looked so soft, I dare hardly mention it."

"Joe," I said, after thinkin' a minute or two, "thoose bawd

yeds theau's seen on th' cliffs puts me in mind o' summat I've

noticed mony a time, an' I didn't know whether to lowf or cry for

shame when I've seed it. It's this: Every day in th' sayson

tha may see young men an' women generally three or four couple

walkin' abeaut these cliffs witheaut caps or bonnets, th' chaps in

knee breeches an th' wenches witheaut cloaks but plenty o' frills

an' folderols on their dresses, an' they strut as airy as if they

owned th' lond, an' say, an' all that therein is. Th'

procession's generally tailed up wi' a chap wi' a bawd yed linkin'

up a lass wi' red yure. An', as tha mentioned at fust, I've

seen mony a time whole columns o' midges floatin' abeaut th' last

couple. They'll drop on th' red yure fust, then they'll shift

for refreshment on th' poor chap's bawd yed. He pretends he's

injoyin' th' walk, but it's aw make-believe, an' she wishes she were

awhoam.

"Th' chaps, tha knows, are strangers to th' wenches, but

they'd met um th' neet afore at one o' th' dancin' reaums, an' they

agreed to meet in th' mornin'. They do meet, an', as tha met

expect, they're aw bare-yedded. That's swagger. Well, th'

chap wi' th' bawd yed is moor often than not th' sharpest i'th' lot,

an' he tries for th' fust pick o'th' lasses. But th' one he

spots has happen been amung th' midges afore, an' hoo says, 'Where's

your hat, Charlie?' That settles it, as far as hoo's consarned.

Noan o'th' lasses wants him, but th' feawest on um's left witheaut

cheice, so Mester Bawdyed has to have her. An', as I said,

hoo's generally red yure. But I'm not meonin' as every woman

wi' red yure is feaw. Nowt o'th' sort. Any skoo-lad ull

tell thee as Queen Elizabeth had red yure, an' it set th' continent

o' fire, an' Philip o' Spain were so ta'n up wi' her gowden strands

as he sent word sayin' he'd wed her. 'Wilta?' hoo axed; 'nay I

think not! I'st never ha' thee as lung as tha lives by suckin'

oranges.' Philip were mad at that, for he were a greit king.

'Go back an' tell her,' he said to his flunkey as were a ambassador,

'as I'll have her, if its nobbut to show her who's th' mester.'

An' Elizabeth said, 'Let him fotch me then.' Hoo were a

detarmined woman red-yured uns are so hoo coom to Lancashire to

raise a' army. Hoo went to Owdham th' fust, an' when hoo towd

what Philip had said, th' chaps rushed off for sowjers theer an'

then, an' hadn't time to ready their yure, so hoo cawd th' regiment

'Owdham Ruffyeds.' Then hoo went to Bowton, an' chaps trotted

off to list in as greit a hurry. Th' Wiggin colliers went i'

their clugs, an' there weren't arms enuff to goo reaund, so she cawd

them her 'Wiggin Puncers.' When Philip yerd as Queen Bess, as

they cawd her, had getten such a army as that, he'd sense enuff to

know as it couldn't or wouldn't be licked, so he awterd his plans,

an' sent th' Armada filled wi' powder an' stuff to blow eaur little

country up, but th' Armada's not been yerd on sin'."

"Tha'rt skippin' th' subject, Anoch," Joe said, "I know aw

abeaut that; it's history."

"So it is, Joe; I'd forgetten. But I were talkin'

abeaut th' folk on th' cliffs, weren't I?"

"That's reet, Anoch; tha were."

"Well, tha'll see groups like as I've mentioned any day in th'

sayson, an' when tha sees um again just try to imagine heaw rich

this country is, for every one o' thoose young men mun be gettin' at

th' very lowest five hunderd a yer."

"Nowt o'th' soart," said Joe, an' he struck a match to leet

his pipe again. "I'll bet their wages are nearer fifty peaund

a yer nor five hunderd."

"Well, that may be so," I ansert, "but I'm nobbut showin'

thee heaw they'd like to make folk think they geet so much."

"I see neaw what tha'rt drivin' at, Anoch, an' I've often

lowft at their impudence mysel'."

"But that's not th' wust on it, Joe," I said; "what pains me

moor is to see heaw yezzy it is for young men to get sweethearts

neaw-a-days. Thoose lasses tha'll see walkin' on th' cliffs

stick howd o' th' lads' arms as if they'd have um, wilta-shalta.

It's disgustin'. When I were a lad we had to feight for eaur

wenches an' a good lass wouldn't look at a lad unless he'd had a

black e'e or two for her sake. If he'd had his nose brokken

hoo valued it still moor as a ornyment, an' hoo'd love him harder.

I fowt twice for eaur Susan, an' I've had her forty yer, yet we're

as happy as two red robins at Christmas. Though she's gettin'

owd neaw, an' th' lines on her face show deeper, still, when hoo

smiles at me, an' I see traces o' th' breetness uv her young days

flashin eaut uv her e'en, I feel as I'd feight for her again, as owd

as I am. In thoose days th' Divoorce Cooart weren't bothered

unteein' church knots; th' mon stuck to th' wench he'd fowt for an'

won, an' she stood by him; but neaw th' Cooart's at it every day

upsettin' th' weddins o' rich folk who owt to know better. So,

I tell thee, a woman what's wuth havin' is wuth feightin' for."

I were a bit excited on th' subject, an' when I'd done I felt

hot.

When I looked at Joe his e'en were starin' across th' say,

an' his pipe had gone eaut again. He'd been thinkin'.

When I stopped he roused himsel.

"What tha says, Anoch," he said, "is very true, an' my thowts

has wandered back to my cooartin' days. My fust feight were

for a wench, an' th' lad as I fowt were one o'th' best friends I

ever had, but we'd a good battle for eaur fust sweetheart, an'

noather on us geet her. But that boxin' match were good

practice, for yers after then I had to feight my road into eaur

Grace's affections, an' I'm sure hoo thowt moor on me for it."

"I never yerd thee tell o' that fust feight, Joe," I said,

"but I should like to yer it."

"Well, tha shall," Joe ansert. "But let's goo into th'

shelter. Th' sun's beilin' hot here. It might be

midsummer, i'stead o'th' middle o' December."

"Th' weather's very good; but it owt to be nice at

Blackpool," I said, as we walked across to one o' th' kiosks, an'

carred us deaun.

Joe started. "Tha knows," said he, "when a lad's

between fifteen an' sixteen he gets an idea that he's quite a mon.

Well, a lot on us abeaut that age signed th' temperance pledge, not

as we knowed owt abeaut it, for we were life teetotalers, but there

were a lot o' Temperance Halls abeaut Bowton in thoose days, an' we

wanted somewheer to goo on wet neets, an' there were plenty o' fun

to be had at thoose places. We jeined a society somewheer

abeaut Halliwell Road, an' every Sunday neet we used to be at th'

meetins, an' oft enoof in th' wick time. Th' yed mon were a

foreman fitter in th' foundry, but he were mooastly away fro' whoam

fittin' machinery up. He were a nice-lookin' chap, an' favvort

a gentlemen when he were dressed up. He gan a deol o' brass to

th' cause, for one time he'd bin a greit drunkard hissel', so he

wanted to make his owd pals believe as cowd wayter were better for

th' constitution than nut-brown ale, but I mun tell thee th' owd

topers were slow at believin' him. For thoose raysons th'

committee made him cheermon, an' when he were awhoam they made a

fuss on him.

"His name were Ormrod, an' he'd three fine dowters. Th'

owdest, Mary, were cooartin'; th' next, Jessie, were abeaut sixteen,

but hoo looked twenty, for hoo were weel built, an' hoo wore lung

frocks; t'other lass were too young for lads to bother abeaut.

"Neaw, one or two uv us lads geet it into eaur silly yeds

that Jessie were noddin' her cap at us, an', uv cooarse, we

swaggered abeaut, like gam cocks, showin' eaursels, when hoo were at

th' meetins. We were so jealous o' one another, that, though

we didn't come to blows, we were awlus ready. But two on us,

Harry Farnworth an' me, were badly smitten, for Jessie ud talk to

oather on us, when t'other were away, as if there weren't another

lad in th' world.

"We used to have two parties a yer, an' after th' tay were

shifted we'd spend th' evenin' in rompin'. Eh, what fun we

used to have! There were as mony lasses as lads, an' if that

Temperance Hall did nowt else good, it were th' meons o' mony a

couple gettin' wed, an' th' population uv Halliwell to-day is th'

result on it. But I'm gooin' to tell thee uv some bother we

had, as happen shaped th' cooarse o' my life. One neet, at a

party, after tay we'd settled deaun for th' fun, as usual, when I

noticed as Jessie Ormrod, were talkin' very sayriously to a chap a

full-grown mon cawd Joe Benson. He'd not been a member so

lung, but he'd jeined for a purpose, as tha'll see. He were a

moulder, but o' Sunday neets he wore a cleon collar an' a striped

tie, fastened wi' a goold breast pin. But what disgusted me

were as at th' bottom uv his cooat sleeves he had a pair o' starched

cuffs hangin' eaut, an' he tried to talk fine-but, sometimes he

forgeet hissel'. When I seed him talkin' so nice to Jessie

Ormrod, an' she liked it, I hated him.

"Well, when th' forms were shifted, somebry axed what we

should play at, an' one o' th' lasses sheauted, 'Drop honkercherf.'

An' we started. Tha knows that gam, Anoch: we make a ring, an'

stick howd uv honds, an' then th' lass starts o' runnin' eautside o'

th' ring wi' a honkercher in her hond, an' hoo drops it on th' road,

beaut stoppin', at th' heels o'th' lad hoo likes best. It's a

good gam; it gives one a seet in th' inner workins o' human nature,

for it shows heaw every lad i'th' ring mun think hissel' th' nicest

in th' cruush, for he looks reaund to see if hoo hasn't dropt th'

honkercher behind him. When hoo has let it faw th' lad has to

pick it up an' catch her afore hoo gets to th' place he's just left,

or else he loases th' kiss as would ha' been his reward.

"Well, some lass dropt that honkercher at me, an' I were

after her like a whippet dug, an' byet her yezzy. Then I went

reaund wi' it, an' dropt it at th' back o' Jessie Ormrod. Neaw

I did try for a kiss fro' her, but hoo were too smart for me.

I were a bit mad, an' I couldn't help bein'. But I felt wuss

when I seed her drop that honkercher at th' back o' Joe Benson, an'

when he started o' runnin' hoo slackened her speed so as he could

catch her. In a bit some other lass dropt it behind me again,

an' I very yezzily won a road to her lips. Then I let th'

honkercher drop at th' back o' Jessie for th' second time. Hoo

expected it foo as I were an' if hoo didn't byet me at runnin'

again I'll be hanged. I needn't tell thee wheer th' white

linen went to after that, but I thowt after as Jessie could ha' done

wi' bein' kissed wi' Joe Benson aw neet.

"Heawever, Harry Farnworth geet th' honkercher fro' somebry,

an' as he went reaund he let it slide very nicely at th' back o'

Jessie Ormrod. Hoo knowed it were comin', an' hoo seet off

runnin'. Well, hoo'd ha' licked him, but just as hoo were

droppin' into his place her foote slipped, an' he won. My

human nature could stond no moor, an' I were grumpy aw neet.

When th' party broke up, an' as we were gooin' eaut, Harry Farnworth

begun o' chaffin' me, just because he'd kissed Jessie an' I hadn't,

an' he said she wouldn't let a cove like me shuv th' dobby-horses

reaund if hoo were ridin'. T'other lads lowft, an' they walked

aside uv Harry, as if they were shomed o' me. This welly broke

my heart, an' altho' I weren't cryin', my cheeks were gradely weet

wi' wayter fro' my e'en. Harry were speilin' for a feight, an'

he couldn't ha' gone abeaut gettin' it in a smarter road.

"So I went up to him, an' said, 'Harry, if tha says that

again, I'll make th' words choke thee.' When I thowt o' that

at after it were a bit foolish on me talkin' that road, for Harry

were two inches bigger nor me, but he were thin an' lanky, while I

were a sturdy lad.

"'Ger on wi' thy makin',' said Harry, 'an' I'll spread some

o' that stuff on th' flure eaut o' thy puddin' yed,' an' he pood his

jacket off.

"Harry's temper were gooin' up, an', what were strange, mine

were coolin' deaun very fast. I were sorry I'd spokken, but I

daren't draw back neaw.

"When we'd rowled eaur sleeves up, Harry axed Bill Johnson,

th' strungest lad amung us, if he'd see fair play. Bill had

fowt mony a time, an' he were one as wouldn't stond any nonsense

fro' owt his size. 'Oh, aye,' ansert Bill, 'if yo'll feight wi'

yo'r neives. No puncin', remember.'

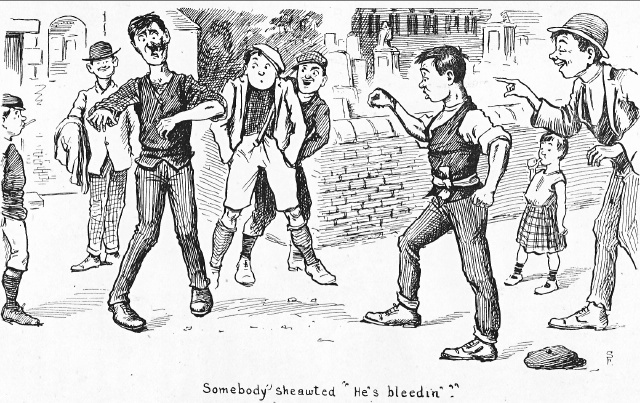

"So we agreed to feight wi' fair boxin', an' Harry sheauts to

me, 'Arto ready?' 'Aye, I am,' I ansert, an' he coom on.

I mun ha' shut my e'en then, for I didn't see him, but I felt he

were somewheer abeaut, an' in a bit my heel kenched o'er a stone,

an' as I felt summat touch my face I fawd on my back. I rowled

o'er an' were up sharp, but as I stood up Harry gan me a regular baz

reet o'er my meawth, an' I went deaun again.

"'Time,' sheauted Bill; 'a minute's rest. Th' fust

reaund goes to thee, Harry.'

"While we rested, Bill says to me, 'Goo for his face, Joe;'

an' then he went to Harry, an' advised him to hit me just above my

stummack.

"We started again, an' I were tryin' to do what Bill towd me,

but I fund I weren't tall enuff to reich Harry's face, an' he were

too high up to come deaun to my body, so we dodged abeaut doin' very

little till Bill cawd 'Time.'

"I coom back to my own style, if I had one, at th' thard

round, I were larnin' to keep my e'en oppen neaw, so I went for

Harry as hard as I could goo. He were faster on his feet nor

me, an' I had to run after him reaund a circle. Sometimes he'd

stop an' catch me one on th' chops, an' start runnin again, me after

him. Th' lads were chaffin' him for runnin', so he stopped an'

sent his arm eaut, an' I fawd again. I'd lost my wynt wi'

skippin' after Harry, so I lay on th' flure till I yerd Bill

ceauntin' me eaut. Then I jumped up for th' fourth reaund.

"My paddy were up neaw. I didn't know whether to cry or

not, but I thowt I'd bite my lip instead. I tried to put it in

my meawth, but I couldn't, for oather my face had run up or my lip

had swelled. When I looked in th' glass next mornin' my lip

were swelled. That made me sure as Harry Farnworth had hit

me.

"Th' fourth reaund begun weel. Harry started runnin'

reaund, but I didn't follow him far. I turned afore he did,

an' as he were passin' I put my fute eaut, an' tripped him up or,

should I say, tripped him deaun. I waited for his gettin' up,

an', as he did, I planked one fro' my reet fist bang on his chops.

I should ha' gan him some moor, but Bill Johnson geet howd on me,

an' said that reaund were mine.

"While we rested I were gettin' used to it, an' I didn't feel

feared a bit. 'This is th' fifth reaund,' said Bill johnson; 'neaw,

Harry get on.' I were waitin' wi' my neives up, but he were a

while a-comin', an' I thowt he were feelin' like I did at th' start.

But he did come, an' I helped mysel' to his body pratty weel, an' as

he were tumblin' again my left fist londed on his lips. He

were up again, afore I'd time to steady mysel', an' I geet some

attention fro' his reet neive just under my left e'e. It made

me blink a bit, an' I run reaund wi' Harry after me. I stopped

in a hurry, an' he went flyin', but he dropped on th' flure.

"Bill Johnson sheauted 'Time.' He slapped me on th'

back, an' said, 'That's thy reaund too, Joe.'

"We sat us deaun on th' low wo' for a bit, when Bill cawd us

for t' sixth reaund. We'd squared up, an' somebry sheauted,

'He's bleedin'. I could feel nowt, so I rubbed my honds o'er

my face, an' there were nowt theer, so I doubled my neives again,

an' set mysel'. When I looked at Harry, oh, what a face he'd

getten! It were covered all o'er. I felt sorry for him,

an' would ha' stopped feightin' if he'd said owt. But he

didn't. I'stead, he coom rushin' at me like a mad bull, an' we

fowt faster that reaund nor any. We were in th' thick on it

when somebry catcht howd on me bi th' back o' th' neck an' th' top

o' th' division o' my breeches an' run me reaund into th' next

street. As I were gooin' I seed Joe Benson were carryin' Harry

Farnworth, just as if he were a babby, an' he chucked him o'er th'

churchyard wo', amung th' gravestones.

"When th' mon as were dreivin' me had had aw th' fun he

wanted, he gan me an extra shuv, an I went to th' flure face fust.

'Theighur!' he said, 'stop theer till tha con behave thysel'.'

Then he walked away. I knowed him; he were a blacksmith, an'

his smithy were aside o'th' Temperance Hall.

"I geet up as weel as I could, for my limbs were gettin'

stiff an' sore, an' I started cryin'. I couldn't help it, for

I were beilin' wi' rage, an' I tried again to put my lip in my

meawth, but I couldn't, an' bit it instead, which made me howl.

'That big coward,' I said to mysel, 'to drag me away fro' a job I

were just gettin' used to, an' when I were winnin' an' aw I wait

till I grow up, an' I'll show that mon summat!' I leoned agen

a wo', an' a chap as were passin, seein' me troubled, axed me what

were to do. This browt me to my senses, an' I were shomed, so

I towd him th' fust lie as coom to my lips. "I've lost my

little brother,' I said. 'Hasta?' he axed; 'well, there's a

bobby reaund th' corner wi' a little lad; happen that's him.

I'll goo back an' tell him, an' p'raps he'll tak thee an' aw.'

An' he turned back, so' I slunk off. As Igeet to th' eend o'th'

street Abram Tacks were bringin' my jacket.

"'Tha's byetten him,' he said; 'two lads has tan him whoam.'

"I never spoke to that, for I felt just then as if I never wanted to

go whoam, or onywheer fro' theer, as I were gettin' stiffer. Heawever, Abram helped me on wi' my jacket, an' stuck to my arm as I

walked. On th' road we met Jessie Ormrod an' Joe Benson, walkin'

arm-i-arm, an' as they looked at me I could see they were havin' a

good lowf. Th' wust on it were as it were Saturday, an' th' teawn

were creawded.

"There were to be a big meeting at th' Temperance Hall next day. Professor

Crosky and Madame Crosky, th' eminent temperance

lecturers, mesmerists, and phrenologists, were advertised all o'er

th' teawnship to address a monster meetin' in th' hall, an', mind

thee, th' place wouldn't howd two hunderd. Well, I wanted to goo,

but my face were in such a mess. When I looked in th' glass my lips

an' my face were so swollen till I didn't know mysel', an' my e'en

were so little I hardly knowed onybody else. When I coom to put a

collar on, it wouldn't goo above hauf road reaund my neck, so I put

a muffler on, an' I went to th' meetin'. When I geet near th' hall I

were just turnin' th' corner to goo in when I bumped reet agen Harry

Farnworth! I thowt he'd done it o' purpose, an' I were shapin' for

another feight, but he said, 'Beg thy pardon, Joe; I didn't meeon

it.'

"'Aw reet,' I towd him; 'no harm done.'

"Then he axed me to come aside a bit, as he wanted to say summat to

me. We went under th' lamp, an' when I looked at his face I should

ha' brasted eaut o' lowfin' only my face wouldn't crumple, an' it

hurt me. He looked like a pace-egger wi' a mask on. Booath his e'en

were black, an' one side uv his jaw looked as if he'd had a tacker-up

on it aw neet.

"'Doesn't tha think,' he axed, 'we were very foolish last neet for

feightin' for a wench like Jessie Ormrod, when hoo's made a foo o'

booath on us?'

"'I do,' I ansert, 'but I didn't know then as hoo were after Joe

Benson, an' made use o' thee an' me to get him.'

"'Well, we'st ha' moor sense another time. Let's be friends again,'

an' he offered me his hond. I took it, an' we shook. 'I'st never

forgive Joe Benson,' he said, 'for throwin' me o'er th' churchyard

wo'. When I'm a gradely mon I'll punce him to pieces.'

"'Well, I think th' same o' Horseshoe Bill,' I said; 'he scufted me

into th' next street, an' then shuved me on my face. Look at it. (I

wanted to make Harry believe he hadn't speilt my looks, but he had.) If ever I get big enuff I'st goo for that mon for aw I'm wuth.'

"'Well, never mind neaw,' said Harry, 'we're thick again; let's goo

in afore th' meetin' starts.'

"So we went in, an' th' reaum were welly full, but we geet a place

at th' front, an' Harry were on th' same form as me at th' t'other

end.

"Madame Crosky were th' fust to lecture on th' evils o' drink, an'

hoo towd heaw a friend uv hers, what were a lord, geet so drunken

that he didn't know what he were dooin'; heaw he chucked her

ladyship, his wife, into th' cut, an' heaw, when hoo geet eaut at

t'other side, he had her locked up for tryin' to dreawn hersel'. Then hoo said th' same lord, another neet in one uv his drunken

sprees, climbed up a lamp-post, an' unscrewed three brass balls fro'

a pawnshop front, an' sent his footmon th' next day wi' um to th'

pawnbroker, who lant him three shillin' on um; heaw he'd wasted his

brass on drink an' riotous livin', till he'd come so low in th'

world that he had to jein th' police force, an' he were a bobby yet.

'That's drink! Drink!' hoo said, 'an' if it will bring a friend o'

mine, a real lord, deaun, heaw much woss will it be for poor folk

like you,' an' then hoo set deaun.

"Th' folk didn't seem to like that soart o' talk, but th' speaker

bein' a woman, they said nowt.

"Then th' Professor geet up to make a few remarks, but I didn't yer

um, for Madame had left th' platform an' come feeshin' for drunkards

to tak th' pledge. Th' fust one hoo ooom to were me. She bent her yed deaun, an' I thowt I smelt gin fro' her breath, but I weren't so

sure o'th' flavour then.

"'Will you sign the pledge, my man?' said she; 'you know drink will

bring you to the grave, if you don't alter your course of life. It's

terrible to see a man in the prime of life going to a drunkard's

doom. Come and sign the pledge.'

"I have signed th' pledge once,' I said, 'but I'll sign again if

it'll do ony good.'

"'That's right,' said she, 'I'm glad you've got a resolution. Just

sit on the platform. There's a form there for penitents.'

"So I went on th' platform an' signed my name, an' th' Professor

clapped his honds.

"'Number one,' said he; 'send them up, Madame.'

"One or two moor coom up, an' then Madame geet to Harry Farnworth. After talkin' to him a bit, he were persuaded to come on th'

platform. He were lowfin' as weel as his face would let him, an' I

made reaum for him at th' side o' me. When th' form were full, an'

they'd aw signed, th' Professor started his discoorse. He

spouted for a bit, an' walked up an' deaun th' platform wavin' his honds,

an' then he turned reaund an' peinted to us as examples o' what

drink does for warkin' folk.

"'Look at these two men,' he said, peintin' to Harry an' me, 'how

distorted their features are. Lock at their bloated faces; isn't it

a warning to you all.'

"Somebry sheauted, 'Thoos lads are life tee-totalers.'

"Th' Professor looked gloppent. He were let deaun a bit, but he were

ready for owt. He stared at us a while, an' then he let off a joke

on me. He said he could see I were only a lad, but I favvort a

monkey wi' its jowl filled wi' nuts. I durn't know heaw I looked

then, wi' everybody starin', an' Jessie Ormrod an' Joe Benson lowfin'

ready to bust, at me, but I felt hot. Then th' Professor said, 'If

these lads aren't drunkards, their faythers an' mothers are.'

"Thats a lie,' sheauted Harry, 'noather my fayther nor mother ever

touched ale. An' mind what yo're sayin'.' He were stondin' up then,

an' I never seed him or onybody else in such a temper. He stared at th' Professor, who seemed a bit freetened uv a row, an' then walked

off th' platform. On th' road eaut o'th' hall ]oe Benson geet up

fro' his seat aside o' Iessie Ormrod as if he'd stop Harry, so I

stood up an' sheauted, 'Let him alone, wilta,' so he didn't bother

to touch Harry. If he had I should ha' fowt too, for we'd said if

oather him or Horseshoe Bill ever tackled oather on us again we'd 'two' him. Then I walked eaut o'th' hall, an' I never went theer

again.

"In a while after I begun o gooin' to another temperance reaum in

Little Bowton, an' when I geet to know um they axed me to jine th'

choir, as I were a good singer. Well, I did, an' as I were abeaut

twenty by then, I fixed my ee'n on a bonny lass as I used to sit

aside on, named Grace Peacock. We booath seemed to like meetin' on

practice neets, an' when th' singin' were o'er hoo didn't object to

stop wi' me at th' street corner, wheer we'd talk for hauf-an-hower.

One neet I took her a bit o'th' road whoam, an' I axed her slap-bang

if hoo were cooartin'.

"'Well, I am an' I'm not,' hoo ansert, but I thowt by th' road she

spoke she'd rayther ha' said, 'Nawe, I'm not.' So I says, 'Well, wilta ha' me?'

"She eyed me all o'er for a minute, then she spoke sayriously:

'Well, there's two chap in th' road one's a moulder, an t'other

chap dreives his own cab they'n booath axed me th' same question,

an' I've towd um I wouldn't have oather on um, but they winnat tak 'Nawe'

for a answer. If tha con shift um fro' botherin' me ony moor I'll

have thee, for I think I should like thee for a husbond.'

"That were enuff. She'd put me on my mettle, an' I went to their heause to ax her parents! consent th' very next neet. When I geet to

their door I seed a chap stondin' on th' opposite side o'th' road at

th' corner uv a bye street. I felt, fro' th' description Grace had

gan me, that he were th' cabman, so I went across to him. He were a

bit less nor me. I axed him were he waitin' for sombry.

"'What's that to do wi' thee?' he says.

"'Oh, I durn't mind what tha'rt hangin' abeaut for at aw,' I towd

him, 'so as tha'rt not waitin' for Grace Peacook.'

"'Well, I tell thee,' he says, 'as tha seems particular abeaut

knowin' I am waitin' for Grace Peacock,' an' he put hissel', as th'

pappers would say, in a feightin' attitude.

"My jacket were off sharp, an' I went at him ding-dong. I winnat

tell thee heaw I banged him abeaut, but he said he'd give in when I

were having a bit o' good practice wi' him, an' uv cooarse I had to

stop then. Yerrin' th' neise Grace an' her mother coom eaut, an'

seed him on th' flure, cryin' for marcy, as one may say.

"'Durn't hit him again, Joe,' hoo said, as soon as hoo knowed who we

were. Then hoo turned to him, as he were gettin' up, an' sheauted in

his face, 'Tha's bin a pest here lung enuff; happen tha'll keep away

for a bit.' He slinked off then, an' he bothered her no moor.

"Grace lifted my jacket, an' her mother were as preaud on me as if

I'd saved a Chinamon fro' a wattery grave by stickin' to his pigtail.

'Come in th' heause, an' wash thy honds,' hoo says, an' I went in,

an' th' owd lady (bless her memory!) gan' my clooas a good brushin',

while Grace put my necktie straight.

"That were a extraordinary introduction," I ventured, just to give

Joe time to get some wynt.

"It were, Anoch; an' it made things yezzy for me, for when I axed th'

mother for her consent to me walkin her dowter eaut, hoo said, 'Aye;

tha'rt just th' lad as I've dreomed eaur Grace would have. I'm glad tha con fend for thysel'. I want no milk-sop in eaur family,' Grace

towd me at after as her mother were quite preaud on me, an' when th'

fayther coom whoam he said wi' a chuckle, after he'd yerd th' tale,

'Good lad; he's th' reet soart; plenty o' Lanky in him.' An' he towd

th' mother he'd be very fain to see me.

"That seaunded aw reet, but I'd some trouble to come yet. . . . Arto

listenin'?'

"I am that, Joe,' I says, "it's like th' story uv a tournyment . . . . .

But th' sun's gradely hot; it make's one sleepy, doesn't it'?"

"It does, Anoch; but I'st not be so lung neaw. Well, Grace an' me

were comin' fro' th' meetin' one neet, arm-i-arm, when a felly

tapped me on th' chest, an' says, 'Here, I want thee.' He were th'

moulder, an' I could smell he'd had some drink. So I loased mysel'

fro' Grace, an' went aside wi' him.

"'What didta meeon by leatherin' Dick Button t'other neet,' he said'

'a chap less than thysel'.'

"I seed I were in for it, but I were owt but feared, so I said,

'What business is it o' thine? If he were less, tha'rt bigger, an'

as tha's hit me on th' breast, tak that," an' my fist went between

his e'en. He staggered, an' as he straitened hissel' I were at him

again. I didn't give him time to put his neives up. When Grace seed

who I were feightin' wi', hoo were railly angry, an' hoo said, 'Give

it him, Joe. He's insulted me oft enuff. Stop his impidence for

ever.'

"'I will,' I said, an' I bashed at him again. He made such a poor

show, that I were feelin' sorry for him. After knockin' him this

road an' then that, I stopped, an' axed him if he'd had enoof, but

he couldn't speik, an' then he dropped to ith' flure beaut bein'

touched. Some men had gathered reaund injoyin' th' scrap, an' one on

um helped me wi' him to a durstep. I wiped his face wi' my own

honkercher, an' in a bithe were better. I axed him if he felt aw reet, an' as he looked into my face so sorrowful it hurt me very

much. Grace (thowtful wench) went to a milk shop a tothri doors off,

an' borrowin' a jug bowt a pint o' milk, an' hoo held it to his lips

to sup.

"In a while he coom reaund, an' thanked Grace, an' said he thowt

he'd manage hissel'. I held eaut my hond to him, an' towd him I were

sorry, but I'd nowt agen him, an' we'd be friends. He shook it, an'

agreed it were his own faut, an' it sarved him reet. 'Good neet,' he

said, as we left him, an' then he cawd eaut, 'Stick to him, Grace;

he's won thee. That mon ull feight a road for thee aw through this

life. Good neet.'"

Joe stopped suddenly, an' as I turned my e'en to his face he were

starin' across th' say as if he were peerin' at th' picture after th'

battle. One or two boats, stragglers fro' th' Fleetwood fishin'

fleet, were lazily makin their way whoam.

"Hasta finished, Joe?" I axed. "It's been like a tale eaut uv a

book."

"I've hardly finished yet, Anoch. I were tryin' to picter that

feight o'er again. I towd thee as Harry Farnworth an' me were fast

friends after eaur feight, an' I may as weel tell thee heaw it coom

abeaut. When he'd yerd I'd jined another Temperance Hall he cawd at

eaur heause one neet, an' said he'd felt lonely sin' we'd left

Halliwell Road, an' axed me if I'd tak him wi' me to th' place I

went to uv a Sunday. Well, I couldn't refuse, noather did I want to,

speshally as he could sing a bit. Grace's younger sister Ellen had jined th' choir just afore then, an' when I introduced Harry I'll be

hanged if he didn't make up to Ellen th' very fust neet he went, an'

th' aggravation uv it were he hadn't to feight for her. But I towd

her he could feight, for I'd had a scrap wi' him when we were

younger. Then hoo had him, an' they'n been wed nearly as lung as us,

an' he's as good a husbond an' brother-in-law as I know. But, as I

started wi' sayin', th' best lasses in thoose days would rayther be

fowt for, an' they liked their chaps better after a flare-up o' that

soart."

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Joe stopped aw at once, an' were pooin' hard at his pipe, as if it

owed him summat.

"Well, ger on wi' thy tale," I said.

"It's finished," he ansert.

"Is it? Why, what becoom o' Horseshoe Bill, an' Joe Benson, an'

Jessie Ormrod?"

"I didn't think that would interest thee," he said; "I only meant to

tell thee abeaut th' feight . . . . Well, Horseshoe Bill deed abeaut

two yer after th' outrage had bin done on me. But I durn't think I

should ha' bothered to quarrel wi' him, anyheaw, an' he thowt he

were doin' me good.

"Joe Benson an' Jessie geet wed, an' though I never bothered my yed

abeaut um, I yerd as they'd three childer when me an' Grace were

spliced."

"But did tha never see um after they were wed?" I axed.

"Nawe, I durn't think so," Joe ansert. "They were dooin' very weel,

an' they were suited to one another; an' when I were fixed up wi'

Grace I were satisfied, an' bore um no ill-will."

I thowt that were railly th' last o'th' tale, till Joe, after bein'

quiet for a minute or two, took his pipe eaut uv his meawth, an'

blowin' a cleaud o' smook away, brasted eaut lowfin'.

"Neaw as I bethink me," he went on, "I have seen Jessie again, an'

it were in such a funny way that I corn't keep my face straight as I

caw it to mind. A while after me an' Grace geet wed I think I've

towd thee as Harry Farnworth an' Ellen were glued together at th'

same time we left Bowton an' coom to live at Blackpool. We'n made

it a practice to spend to'thri days wi' um at Christmas, an' they

return th' visit in th' summer. Well, four yer sin', we were sat

smookin' after finishin' th' Christmas goose deaun to th' lucky

booan, an' th' talk turned back to eaur lad days, an' th'

remembrances uv Halliwell Temperance Hall coom on th' carpet. We

were very merry o'er it, when I axed Harry if he'd ever seen Joe

Benson an' Jessie Ormrod sin' they were wed.

"Oh, aye," he ansert, "I've seen her mony a time. Joe's been deeod

mony a yer, an' neaw as their family's grown up hoo keeps a shop in

Moor Street."

"For a bit o' divilment I said, 'Let's goo an' have a look at her.' I could see as Grace's e'en twinkled to'rt Ellen as I used thoose

words, for they were ready for fun when it were to be had. 'Is that th' wench yo' two fowt for when yo' were lads?' Grace wanted to

know.

"We towd her it were, an' hoo turned to Ellen, an' said, 'Get thee

ready. It's a grand neet; let's see th' dark-eyed beauty as turned

eaur husbonds' yeds, an seet their hearts afire.' Th' women put

their things on, an' we aw went for a strowl.

"Th' air were crisp an' sharp, an' we went reaund by th' Gilnow to

Dean Lone, comin' back by Dobhill. Abeaut ten minutes walk fro'

whoam Harry stopped us at a bacca shop, an' said, 'This is it. Hello! hoo's theer.'

"I looked through th' winder, an' I seed a woman abeaut fifty-six

yer owd sarvin' a lad wi' a penn'orth o' fags. 'That's not Jessie Ormrod, is it?' I axed.

"'It is,' ansert Harry. 'Isn't hoo awterd?'

"'Hoo has. I shouldn't ha' known her.'

"We were shapin' to goo away, when Grace axed, 'Arn't yo' gooin' to

speik to yo'r fust love?' An' I looked at her. Her face were ripplin' wi' smiles, an' so were Ellen's, so, as I seed as they took

it so comically, I says, 'Yah, I'll goo in an' buy some cigs.'

"I

walked in, an' said, 'Good afternoon. Han yo' ony Black Dug

cigarettes?'

"'Nawe," hoo ansert, 'but wo'n Red Robins an' Sergeant-Majors.'

"'Well, gi' me hauf-a-peaund o' Red Robins.'

Hoo lifted a drawer fro' th' back uv her, an' while hoo were findin'

th' cigarettes, I looked at her. I never seed such a change in my

lifetime. She'd looked to us, o'er thirty yer afore, a rare bonny

wench, but neaw she'd no bottom teeth an' she'd a lump at th' top uv

her yed as big as a duck's egg. She were th' fattest woman I'd seen

for a lung time, an' her neck were level wi' her face. I wondered

then wheer my e'en were when I were so young.

"She looked for th' cigarettes up an' deaun, then she coom to me. 'I'm

sorry I'm run eaut o' Red Robins, but th' Sergeant Major is very

good; will yo' have them?' an' as hoo said this, I seed her starin'

at me.

"'Well, I durn't care much for thoose,' I said; 'but I'll have an

ounce on um.'

"As hoo were weighin' um I spoke to her. 'Weren't yo' cawd Jessie

Ormrod afore yo' were wed?'

"Hoo looked full at me. 'I were,' she ansert, 'but I'm Mrs. Benson

neaw.'

"'Well," I axed her 'did yo' remember two lads, named Joe Short an'

Harry Farnworth, as went to th' Temperance Hall at th' same time as

yo' an' yo'r husbond?.'

"'I do,' she said; 'an' art theau Harry Farnworth?'

"'Nawe; I'm Joe Short.'

"'Heaw lung's thy wife been deeod?' she axed in a hurry.

"'Hoo's not deeod, I hope,' I says; 'hoo were lookin' through th'

window when I coom in; an' so were Harry Farnworth an' his wife!"

"Ah, dear," hoo sighed; "what a while sin' then. Fotch him in,"

"So I cawd Harry in, an' he shook honds wi' her. 'I'm fain to see

you booath,' hoo said. 'My husbond's bin deeod three yer. See yo',

that's my youngest dowter,' as a young woman coom fro' th' kitchen

to ax her summat. I felt a shock come o'er me as I looked at th'

young woman, for hoo were th' very spit uv her mother in her younger

days.

"Well, we talked o'er owd times for a minute or two, an' I axed her

at last if hoo remembered me an' Harry havin' a pitched battle at

side o'th' church when we were lads.

"'Aye, I remember,' hoo ansert, 'but I never yerd what yo' fowt

abeaut.'

"'Well, I'll tell yo,' I said, 'we fowt for thee, an' noather on us

geet thee.'

"'Nawe, yo' didn't. Well, it corn't be helped. I durn't think yo'd

feight for me neaw; would yo.'

"'Nawe, we shouldn't,' Harry blurted eaut, witheaut thinkin'. I seed

Harry had put his fute in it, an' hoo looked shomed, so I chimed in,

'We wed two sisters; they're theer at th' window grinnin' at us. We're gradely mated, an' very weel satisfied wi' um.'

"'That's reet,' said Mrs. Benson, 'stick to um.'

"Grace knocked at th' window for us to come eaut, as they were

gettin' cowd stondin' theer, so I held eaut my hond. Mrs. Benson

took it, an' said, 'Caw to see me again, ony time yo're abeaut,

booath on yo'. Good neet; good neet.'

"So we left her, an' aw th' road whoam Grace an' Ellen were chaffin

abeaut what we'd missed in not weddin' eaur fust sweetheart. 'Just

fancy,' said Ellen to Grace, 'these two honsome men marryin' such

feaw beggars as us when there were such dark-eyed beauties as yond

knockin' abeaut.' I felt a bit mad, an' I towd Grace hoo owt to be

ashamed uv hersel', lowfin as hoo did, for it were Nature as had

awterd Mrs. Benson, an' hoo didn't know but what hoo'd have a bob on

her yed afore hoo deed. This made um sayrious, an' they said no

moor."

"Heaw's Mrs. Benson gettin' on neaw, Joe?" I axed.

"I've never seen her sin'," he ansert.

It were gettin' dusk neaw, so we went towards whoam. Grace were stondin' at th' dur lookin' for him when we geet to their street,

an' I waved my hond to her an' bid Joe "Good neet."

――――♦――――

HARD TIMES!

Remembrances of the Cotton Famine.

1.The American War.

IT is fifty years ago, this 1911, since the commencement of the

American Civil War. Fifty years! It is a long time, certainly, but

to one who has lived much over half a century the occurrence of some

happening of unusual magnitude during that one's youth leaves its

impress upon the memory till the end of life. The history of the

American War has been written more than once, and the interest in it

has lost its significance for Europeans. Yet there are many people

living in Lancashire who do

remember the effect it had upon our trade, and those old people will

testify, with a saddened sigh, to what working folk endured during

Lancashire's tribulation.

No one thought, when the war started, that it would be greatly

prolonged; the Northern States, not expecting war, were entirely

unprepared for it, and as they were badly beaten in the initial

engagements, it seemed much as there would be two Americas, and that

very quickly. But President Lincoln took, as the Persian maxim has

it, the bit between his teeth, and, by his untiring energy, not only

utilised all the known forces of the loyal States, but created an

enthusiasm which resulted in the organisation and equipment of

armies large enough in those days to astonish the world.

When the war broke out in 1861 America's fleet was so small as not

to be considered seriously as a factor in war, and that was one

reason why British folk didn't fear that the war's horrors would be

felt over here more severely than hostilities between any two

civilised nations must disturb trade in any other country who had

had close commercial relations with them.

Our eyes were opened, however, when we read that within a period of

eight months after the fall of Fort Sumter the Northern States had

doubled the tonnage of her war fleet, and that they had stretched an

effective blockading chain across the Southern ports, right from

Cape Hatteras to the Rio Grande.

2.Cotton "Famine" or "Panic."

After then there was a "famine" in cotton, but that was only a name

given to the stoppage of importation, for many wise heads among

cotton brokers and factors had foreseen or professed to foresee a

dearth in the raw article, and had bought and stored every pound of

cotton they could lay their hands on.

The Lancashire operative, ever alert in matters concerning his work,

read with satisfaction of the accumulation of large stocks of the

raw material in our county, and naturally concluded that this

abundance meant continued work for him, and his chagrin was intense

when he was told that the mill from whence he earned his living

would be closed until further notice.

In reply to representations made later, the masters urged that there

were tremendous stocks of manufactured cloth on hand, that

remunerative prices had not ruled for a long time previously, and

that the mills could not be re-opened until those stocks had been

depleted. The explanation was mostly true, and, as the war had

affected the demand, the over-production was a long time in being

materially lessened.

In the meantime events were occurring which developed disastrously

for the workers. When the surplus stocks of cloth did begin to move,

holders were able to get better prices, not, however, so great as to

show a large profit on manufacture and stock, but such as made it

more profitable to sell than to hold.

Now came the factory masters' chance. The blockade of the Southern

ports was so vigilant and effective that the importation of cotton

was stopped, and the masters and brokers held the whole available

supply. The temptation to make big fortunes was too great to

withstand, and the brokers offered high prices to the masters for

repurchase of the raw cotton they had previously sold them. This

caused what Lancashire called the "Cotton Panic," by which name the

effects of the Civil War are remembered to-day. The scenes on the

Exchanges were bewildering. Brokers, in their frenzy to get hold of

the untouched bales of cotton, offered fabulous prices for it. Manufacturers, who had been wont to use the Exchanges for buying

cotton now became the sellers of it, and the brokers who had sold it

to them bought it back again. Then it was re-shipped to America

this time to the Northern States for manufacture. The Americans

paid our brokers three times as much as it originally cost from the

Southern planters. So, men who had never done a fair day's work in

their lives amassed handsome fortunes out of the traffic in a

commodity which was necessary for providing us with a means of

livelihood, and that at a time when Lancashire was starving! But I

have noticed since then that there were men always ready, and quite

willing, to wax fat by their country's calamities.

The stoppage of the mills had its effect on other industries which

were dependent to a degree on their running. Coal mining,

engineering, and machine making were seriously affected, and

thousands of workers who followed those occupations for a livelihood

were soon in as sad straits as the cotton workers themselves.

Now and again a ship laden with cotton would succeed in "running the

blockade," but the prices asked for it were almost prohibitive, and

the mill-owners those with large hearts who succeeded in getting

hold of it would work it more out of sympathy with their suffering

dependents than with regard to profit for themselves. But such

relief was spasmodic, and but served to temporarily soften the

privation and misery. The whole north of England suffered, but there

were degrees of distress in different parts. The towns of Preston,

Ashton, Blackburn (Lancashire), Stockport (Cheshire), and Glossop

(Derbyshire), were very hard hit.

3.Surat Cotton.

Indian cotton, of a very coarse fibre, which had been despised when

there was a plenitude of American grown, now came in vogue, but as

the demand for it grew, the planters, in their greed for big

profits, sent it here so poorly picked that, although special

machinery was adapted to its treatment, the bales contained so much

pod and green cotton that it often spoiled the machines, and tore

the hands of the workers who manipulated it.

As the imported Surat became worse so grew the operatives dread of

working it, until eventually many of them preferred to go hungry

rather than have anything to do with the vile stuff. When these were

driven to apply for relief to the Guardians, and were taunted with

idleness or malingering, they would retort, "Look at my honds!" and

they would show them, mutilated, bleeding, or indented with cuts, in

proof of their inability to continue working the material.

The pitiful state of distress into which the factory worker was

reduced was well pictured in the following poem, by Joseph

Ramsbottom, a rhymer of some distinction in Lancashire forty years

ago:

|

THE OPERATIVE'S LAMENT.

Eh, dear! What weary toimes are these,

When scores o' honest workin' folk

Reaund th' poor-law office dur one sees,

Like cadgers, wi' a cadgin poke;

It's bad to see't, but woss a deeal,

When one's sel helps to make up th' lot ;

We'n nowt to do, we dareno' stayl,

Nor con we beighl an empty pot.

Aw hate this pooin' oakum wark,

An' breakin' stones for t' get relief;

To be a pauper pity's mark

Ull break an honest heart wi' grief.

We're mixt wi th' stondin' paupers, too,

Ut winno wark when wark's t' be had,

A scurvy, fawnin', whinin' crew

It's hard to clem, but that's as bad.

An' for mysel' aw wouldna do 't,

Aw'd starve until I sunk to th' flure;

But th' little childer bring me to 't,

An would do th' best i'th' lond, I'm sure.

If folk han childer starvin' theer,

An' still keep eaut, they're noan so good;

Aw've mouy a time felt rayther queer,

But then I knew they must ha' food.

When wark fell off aw did my best

To keep mysel' an' fam'ly clear;

My wants aw've never forrud pressed,

For pity is a thing aw fear.

My little savins soon were done,

An then aw sowd my twoth'ry things

My books an' bookcase o' are gone,

My mother's picter, too, fund wings.

A bacco-box wi' two queer lids,

Sent whoam fro' Indy by Jim Bell,

My fuschia plants an' pots, my brids,

An' cages, too, aw'm forced to sell;

My fayther's rockin-cheer's gone,

My mother's corner cubbert too;

An' th' eight-days' clock has followed, mon

What con a hungry body do?

Aw've gan my little garden up,

Wi' mony a pratty flower an' root,

Aw've sowd my gronny's silver cup,

Aw've sowd my Uncle Robin's flute;

Aw've sowd my tables, sowd my beds,

My bedstocks, blankets, sheets as weel;

Each neet on straw we rest eaur yeds,

An' we an' God know what we feel.

Aw've sowd until aw've nowt to sell,

An' heaw we'n clemmed's past o' belief;

What next for 't do I couldna tell,

It were degradin' t' ax relief.

There were no wark, for th' mill were stopt,

My childer couldn't dee, yo' known;

Aw'm neaw a pauper cose aw've dropt

To this low state o' breikin' stone.

But wonst aw knew a diff'rent day,

When every heawr ud comfort bring;

Aw earned my bread, aw paid my way,

Aw wouldna stoop to lord nor king.

Aw felt my independence then,

My sad dependence neaw, I know;

Aw ne'er shall taste thoose jeighs again

Aw'm sinkin' wi' my weight o' woe. |

4.When Lancashire "Clemmed."

There were, as I mentioned, those who never forgot their duty to the

workers who had been instrumental in giving them the opportunity of

obtaining wealth. These men, when they couldn't run their mills for

lack of cotton, assisted in forming relief societies and emptied fat

purses into their coffers. Their wives and daughters found useful

occupation in organising and working sewing schools, which made

garments for the women and children most in need, and tradesmen gave

of their time and depleted means in managing soup kitchens.

All classes were brought closer together by common suffering. The

poorest were kept from actual starvation by voluntary inspectors,

who hunted out and immediately relieved those in dire need. Tickets

were left with heads of families entitling them to so much soup per

head on two days per week, and these tickets were supplemented by

other coupons representing value in bread and groceries on the same

ratio. Those doles and the times are still remembered in Lancashire

as "Th' Dow Days."

As time went on, without prospect of improvement, the drain on

public charity began to tell, and the distribution of food had to be

curtailed to such limits that there was not sufficient to satisfy

the cravings of Nature; little more, indeed, than was necessary to

sustain life. The outlook was dark, and the times were hard!

It was pitiable to hear of the efforts, with poor returns, of the

more independent workers to help themselves; they resorted to every

thinkable means of getting a penny honestly. Sturdy men, whose hands

were so torn and blistered by spade work, or working Surat cotton,

in return for relief, that they could labour no longer, formed

singing groups, and the more clever among them would compose

ballads, which they sang in market places and at street corners, and

sold copies to any who would buy. I remember a verse of one of

these, which I print as a curiosity:

|

See a poor mother weeping,

Heart-broken and sad.

Her garments all threadbare,

Her children half clad.

Save a chair and a table

No furniture there,

And the cupboard, once laden,

Now empty and bare

For want and starvation

Look in at the door

Of the once happy homes

Of the Lancashire poor. |

Such was the condition of the county folk in 1864. Life was a misery

to many but still it was Life, and the veriest poor shrink from

the alternative! Lancashire was broken, and the hitherto hearty and

industrious worker had nothing in prospect save Hope and Dow!

5. Some Personal Experiences.

In the remaining pages of this book are some of my own experiences

during the Cotton Panic, the names of persons (some of whom are

still living) and of places being, for obvious reasons, imaginary:

Hope-street might have been visited by a plague. One-third of the

forty houses of which it was composed was empty, not from any fault

in their construction, or that they were in bad repair. There was

nothing to complain of in the width or position of the street, for

it was typical of those generally occupied by factory workers long

rows of small tenements, two rooms up and two down, with the windows

well polished and the footpath flags always scrubbed as clean as

hands could make them. But the tenants had had to abandon their

homes through lack of work. Some of them had gone to other parts of

the town, to live with other families almost as poor as themselves,

and, by so doing, being able to economise both rent and fuel. Others

had sent their children to friends in distant counties, who

generously undertook their care till times mended, and the father

would go on tramp, seeking a job by which he might earn a living;

whilst the mother would char, wash clothes, or take domestic

service, where it could be got. Where others got a lodgement I

cannot say, for sure, but I am sorry to think it was the work-house. Of the remaining two-thirds then occupying Hope-street one half

would be out of work or only casually employed.

I lived in Hope-street, the topmost house on one side. It was the

smallest house, as, being built at the top, there were four similar

ones round the corner, and, having no yard space, we had only two

rooms, a kitchen and a bedroom. The rent was 2s. 9d. per week.

I was one of the fortunates, having as much work as enabled me to

earn nine shillings a week, certainly no more. I had not long been

married, and my wife, as a weaver, had the good luck to work for one

of those sympathetic employers who strove hard to keep his sheds

running, even if he lost money, rather than let his workpeople

starve. But he had to divide his work to enable a greater number to

earn a subsistence, so the ordinary four-loom weaver had to be

contented with two, and as the cloth woven was not of the best, my

wife would be able to earn about as much as myself. We couldn't

perform miracles with eighteen shillings a week, but as we had been

even worse off, we had learnt frugality, so we managed to save even

a trifle out of that. The sum was small, about nine-pence a week,

but when we married we had very little indeed to furnish even our

small house, and the savings were accumulated until we had

sufficient to buy an extra chair or two, or anything we felt we most

needed.

We had managed to get together five shillings as the result of a few

weeks' savings, and as we had had to use candles for light in the

evenings, we decided to have gas. A company owned and controlled the

gas lighting in Bolton then (it has for many years past been owned

by the Corporation), so we had to lay down a deposit of five

shillings before being served. I paid it, and the gas was turned on

from the street. When we lighted the jet the glare was so great by

comparison with what we had been used to that we were afraid the

house would catch fire. I smile when I remember hearing a pair of

clogs wander up the street and the wearer would stop under our

window, look with amazement at the illumination through the blind,

then clomp back again, followed by the sound of another, and yet

another, repeating the performance, and when I opened the door there

were gathered several of my neighbours anxious to discover what had

illumined the street, for there was no light at the top, the only

public lamp being at the bottom. During the first night of our using

gas we were kept awake very long by a bad smell, which we found

emanated from some of the fittings, and I went to the Gas Office to

complain of it, thinking, in my innocence of such matters, they

would put them right. I was taken down a bit when they told me to

call in my plumber to make the fittings tight. "My plumber!" I

exclaimed; "plumbers are luxuries, an' I've no brass for owt o' that

soart." "Well, then," replied the clerk, "you'd better have your

deposit back, and we'll turn the gas off. We'll check the meter

to-day, and if you'll call to-morrow we'll return you the balance."

I went during my dinner hour the next day, and he returned me 2s.

8d., saying that we had consumed 2s. 4d. worth of gas. I was glad

afterwards that we had settled up, for we had only one gas jet in

the house, and 1s. 2d. a day for gas was about equal to the amount

we could then spend on food.

I may mention an incident in connection with the gas which, though

it hurt me very much when it occurred, furnished the best lesson I

ever learned, and served as a model rule which I adopted in

business, and has been largely responsible for whatever success I

have had in life. Young men in those days did not think it

derogatory to their dignity to attend a Sunday School. The teacher

of our class at the one I attended was a good living man, and his

lessons and addresses were much appreciated by us. He was a friend

to us all, and we reciprocated his good feelings. Kind-hearted he

was, and would often invite us in batches to take tea with him at

his house in the week evenings, and so we came to know his wife and

family very well. He was a manager at some kind of works, and he

also owned an ironmonger's shop, which his wife and daughter tended.

A fortnight after I had drawn what remained of the gas deposit I was

going home on the Saturday afternoon. As I passed my teacher's shop,

the thought struck me that if I bought an oil lamp it would be much

better than candles, and as I saw some of those commodities in the

shop window, I went in and asked Mrs. Brown, my teacher's wife, to

show me two or three different patterns, and tell me the prices of

them. She arranged several on the counter, and I chose one that I

thought would suit us.

"That's two-and-sixpence," she remarked.

"Well, I think that will please my wife, Mrs. Brown, and I'll take

it. I'm coming down again after tea, and I'll bring the money then."

"Nay, yo' winnat," she said, and she removed the lamps from the

counter. "We durn't trust onybody here."

I remember being very much ashamed then, as I had really intended to

bring her the money within two hours. I went home, however, and

without waiting to have my tea, got the money and bought the lamp,

more to let her see we had the cash than with the intention of

hurrying the purchase.

It was a smart warning which left an impression, for since that day

I don't think I have ever asked anyone to give me credit. I have

bought everything, be it little or much, with my cash ready, and I

soon earned a reputation among the business men I traded with for

paying promptly. This system has been very beneficial, by enabling

me to buy cheaper, and often to laugh at market prices. That

experience of mine may be of benefit to some people starting married

life; if so, it will have been worth the telling.

6.―How we Lived.

Some of my friends have doubted the statement that we could have

lived and worked on seventeen shillings a week, and I have smiled at

their doubts. The fact is easily explained, for coarser, but much

more wholesome, foods were ordinary diet. Oatmeal porridge was a

staple dish; treacle, now called golden syrup, was kept in large

tin jugs, and sold by every grocer at 2d. per lb.; whilst black, or

Scotch treacle, was only l½d.

per lb. Every child would have his "butty" covered with treacle, and

it had the merit of keeping the bowels right. Margarine and butter

substitutes were neither known nor wanted. Tea was dear, but

splendid buttermilk could be got for a penny a quart. Again, good

Irish bacon cost but 5d. a pound; whilst good house coals were to

be had from the pit mouth by the load at 4½d. per cwt., and the

customer, if reliable, was not called upon to pay for his load until

he ordered its successor. Added to this, every Lancashire lass over

sixteen years old could cook and bake, knit and darn stockings, wash

and starch and iron clothes, and do everything required for keeping

a house in order, and on entering the cottage of a young married

couple there would be seen an antimacasser over every chair back, on

the table, and on the sideboard, and each cover had been "crowsherd"

by the wife's own hands. I don't know if the Lancashire lasses of

to-day have been so well tutored; one may hope that they make such

good housewives. I have shared, with five others, a potato pie made

by a Lancashire housewife, and we have each had a satisfying meal,

the whole of the ingredients of which cost only ninepence.

At the time I have in mind the war was just over. General Grant had

compelled General Lee, the Confederate leader, to surrender his army

and Richmond, some months before, and although there was some

scattered fighting by minor armies, the end was at hand. The hope

which had buoyanted the cotton worker through the terrible ordeal

was near realisation, but now was "the darkest hour before the

dawn," and the suffering was intense.

7. Our Neighbours.

My home was at 39, Hope-street. Our neighbour at 37, Jim Hitchin,

was a moulder. He had been out of work a long time, and their wealth

consisted of a large family, they owning five children ranging in

years from five to two. Jim was a life teetotaller, and, I

understood, a good workman. His mother, who owned a small shop not

far away, had helped them as well as she could; his trade club had

done something, and wherever he could find a temporary job within

his capacity he was eager to earn a trifle for doing it. But they

were poor, and as the children were sometimes short of food it was

not to be wondered at that their father should often be dejected and

miserable. Jim's neighbour Tom Cross, at No. 35, was a collier, and

was working about two days a week. He had a wife and child.

Coal was

low in price in those days,

and the miner, when in regular work, couldn't be charged with

receiving extravagant wages when fully employed. Though the price of

coal was low, it was very scarce in our neighbourhood. I know we had

to be very sparing in the use of it, and we and the Cross's used to

sit in each other's houses on alternate evenings to save one fire,

and Jim Hitchin and his wife would often join us to warm themselves

after their children had been put to rest.

We were sitting in Tom Cross's house early one night when Jim

Hitchin lifted the door latch and walked in. His face was as pale as

one could imagine a man yet alive to wear. Mrs. Cross had been

baking three pounds of flour, and there were several muffin cakes

on the clean table. I was going to speak to him, when I saw him look

across the table to where Mrs. Cross stood.

"It's come, Emma," he said.

Mrs. Cross knew what he meant.

"Has it?" she retorted. "What is it, Jim?"

"Another lad," he answered, and he sank down in a chair beside me,

and he rested his elbows on his knees, and with his head in his

hands, he cried bitterly.

I have been many times since then a witness of, and on occasion,

unfortunately, a participator in, scenes that were grief-laden and

distressing, but I shall never forget the agony of that cry. I was

too inexperienced to understand the meaning of it, for up to then we

had no children of our own, and I thought the advent of a child to

bear one's name through life was an occasion for joy rather than

sorrow. But I didn't know at that moment there was neither bite nor

sup in Jim's cupboard, and that his fire-grate was empty.

Jim's trouble cast a damper on what little spirits we had within us,

but the womenfolk grasped the situation at once. There was a little

whispering between them, and my wife went home. Mrs. Cross toasted a

cake and buttered it, and my wife returned with some tea and sugar

in a paper. We had bought a pound of black currants the week

previous, and had them preserved for our use on Sundays, as long as

they would last, and we did make such luxuries spin out then! This,

however, was requisitioned, and a nice repast was made for the sick

woman, which she enjoyed, and for which I know she was thankful. Tom

and I went in to see Mrs. Hitchin and the baby when matters were

composed. Tom Cross, looking at the fire-grate, whispered, "Th'

place looks cowd; let's build um a foire." And we did, giving them a

day or two's supply of coals from our scanty stores.

After all the years which have intervened between then and now it is

still one of my most pleasurable memories to recall how our wives

tended Mrs. Hitchin when they had the time. The self-denial

exhibited by the Cross's I couldn't forget, and they so poor! If

ever men prayed devoutly for a change of fortune they were we three

of Hope-street. The change in our circumstances still seemed afar

off, but it did come.

8.Jim's Struggle.

Mrs. Hitchin was getting about again, and her baby boy was healthy

and strong; we had lusty "vocal" evidences of the fact, and that was

something to be thankful for. We were "camping" in our house about a

fortnight after the "event" just mentioned, when Jim Hitchin joined

us. Our conversation turned, as was generally the case, on our day's

experiences and an exchange of views as to what prospect there was

of an improvement in our circumstances. In a while Jim told us he

had been trying to borrow a little money from some friends, but they

had been unable to accommodate him.

"I durn't know what to do," he said, "nobry seems to have owt. I yerd to-day as Molyneux's were startin' moulders, an' I went. They

promised me a job, but it'll be a month afore they con get ready. Heaw we're gooin' to live for a month on nowt I connot tell."

We all stared at the little bright fire, for no answer was ready. Eventually I remembered the gas deposit, which we made up into over

five shillings again, and I remarked, "Jim, I've five shillin'; tha

con have that till tha'rt able to pay me back."

A load seemed lifted from him. "Well, I shouldn't know heaw to thank

thee if tha would land it me. Tha'st have it back, if I live."

I went upstairs quite cheerily, for poverty had seemed to strengthen

our friendship. We kept our savings in a hair trunk, bound with

strips of leather and studded with brass nails (a style of box much

in use fifty years ago), and scraped the money, nearly all copper,

from the bottom. We had five shillings and twopence-halfpenny, and,

leaving the twopence-halfpenny to "breed off," I took the five

shillings down, and as I placed it in Jim's hand I never heard

gratitude more strongly expressed.

9.Luck at Last.

Now fortune's wheel began to turn in my favour. The week after

I lent Jim the five shillings I was offered a job in Manchester at

thirty shillings a week a fabulous sum it appeared to me. Of

course I accepted it, and we removed our goods in about three weeks

afterwards. The extent of our worldly possessions may be gauged from

the cost of removal. The railway company sent a lorry to

Hope-street, Bolton, then transferred the goods to a railway truck,

conveyed them to Manchester, and delivered them more than two miles

from their station, at a cost of 4s. 7d.!

Having been compelled to be frugal when poor it was quite easy to

practice economy in our improved circumstances, and we managed to

put a few shillings aside every week. In a few years I was able to

start business on my own account, and as time rolled on I was fairly

successful. I learned that business was often so speculative as to

become a gamble, and, although I had lost many pounds in early

efforts, and had dismissed from my mind many bad debts, I never

forgot that I had once lent a man, when at the bottom of his luck,

the only five shillings I had, and that he had promised to pay it

back to me, "if he lived." I never doubted his honour, but I

remembered his large and increasing family of youngsters, and

wondered if ill-fortune still kept him company.

10. After Twenty Years.

Twenty years after I had left Bolton I was agreeably astonished one

day at seeing Tom Cross enter my shop. I knew him at once, and I

persuaded him to stay and have tea with us. He could hardly believe

his eyes when I introduced him to my three daughters, fast

developing into womanhood, and when my wife came into the room he

couldn't restrain his joyous feelings. He took her hand in his

strong grip, and shook it so hard, that I had to laughingly ask him

to release it.

"Why, bless yo', yo're lookin' younger nor ever," he remarked; "Eh,

eaur Emma would be fain to be here just neaw."

"Well, tha should ha' browt her," replied my wife, humouring his

mood by dropping into the dialect; "whatever makes thee tak such

lung journeys by thysel'? Tha'll be gettin lost some day."

"Not as lung as I've such owd chums as yo' for t' tak' care on me. Hoo'll goo off her yed when I tell her I've seen yo' booath."

"Well, sit thee deaun an' mak thysel' a-whoam. I'll soon have some tay ready, an' it'll warm thee up a bit."

Tom did her bidding, and, when he did recover from his surprise and

pleasure, we talked of the old dark days of the "cotton panic," and

then the conversation lightened up to the changes in fortune that

had fallen to the lot of each of us. I asked him if Hope-street

still occupied a place on the town's map, and, if it did, was there

any change in its appearance since the time we lived there as

neighbours.

"Oh, aye," he replied, "th' owd streets still theer. I were through

it abeaut two months sin', but everybody were strangers to me. It's

as cleon as it were when we used for t' cleon th' flags to stop eaur

limbs from growin' stiff an' rusty."

"Well, neaw, Tum," said I, "I want thee to tell me summat abeaut

thysel'. Tha sees I'm better off nor when we lived at th' side o'

thee; an', besides, wen getten these three wenches, an' they're a

comfort to booath on us.' So, tell me heaw yo'n bin dooin' for th'

last twenty yer."

The huge smile left his face, and he looked serious in a moment.

"We'n had aw soarts o' luck sin' then," he replied, "but mooastly

good. After yo' left, eaur Emma had another babby a gradely bonny

lad but when he were abeaut a yer owd he couldn't get through his

teethin', an' he deed o' croup. It were a great trouble to us for t'

loase him, an' th' wife were two or three yer afore hoo geet o'er

it, she took it so much to heart."

"I'm sorry to yer that," I told him, "but we corn't have things eaur

own road. If tha goes to th' sayside in th' summer, or to th'

country when Nature's in her happiest mood, tha doesn't give a thowt

that th' grander th' place is then, wi' th' sky so clear o'eryed,

an' th' leaves on th' trees rustlin' abeaut so merrily, when winter

comes it gets just as dismal, when th' trees are bare an' th' sky

gets grey, an' th' winds are howlin' o'er th' say, an' one connot

stond upreet. So it is wi' life, Tum: th' greater pleasures we han

mun be followed by doses o' pain, or else we shouldnt know what

pleasure were."

"I see," answered Tom, "tha talks just th' same as tha awlus did,

an' tak's things as they come . . . . . Well, when yo' left Bowton

we lost two pals we thowt summat on, an' what made it woss, th' pit

stopped at th' time; it were flooded for a month, an' I durn't know

to this day heaw eaur Emma managed to keep eaur sowls an' bodies

together, for I didn't earn a penny aw th' time."

"One doesn't know what a good woman con do," I remarked, "till

they're tried by circumstances. Emma were awlus careful, an' happen

she'd saved a bit as tha knowed nowt abeaut."

"Maybe so," he said; "hoo awlus were clever. Well, when th' pit

oppend again we started full rig, an' we worked lung heaurs. We made

up what we'd lost, I think, an' after abeaut three yer I were made

under-manager, an' I've had th' job ever sin'."