|

[Previous Page]

|

EH, BILL! COME TO BLACKPOOL.

EH,

BILL, come to Blackpool! an' bring

thi Wife, Mary,

Hoo looks fairly run deawn wi' moilin' through t' day;

An' bring Jack an' Nelly that curly-nobbed fairy

That cowf ut hoo's getten ull soon pass away.

It's lively just neaw for there's crowds o' folk

walkin'

Up an' deawn th' Promenade fro' mornin' till neet;

They're as happy as con be, lowfin' an' tawkin'

By gum, Blackpool just neaw's a rally grand seet!

Come on to Blackpool yo' may spend a nice hower

In a sail fro' th' North Pier to Fleetwood an' back;

Or a grand afternoon i' roamin' through th' Tower,

For th' monkeys an' tigers ull pleose yore Jack.

Yo' may goo on to th' piers there's skatin' an' dancin',

Or ride to th' South Shore, an' get fun eaut o' th' fair;

Or tak' th' childer on t' sands, an' jine i' their

prancin',

An' help um build castles theau's built some i'th' air

Get ready: come neaw! for I've getten a notion

Ut a sniff o'th' briny ull do yo aw good;

An' breathin' th' ozone fro' th' owd rollickin' ocean

Is th' reet soart o' physic to tingle one's blood.

Yo want'en a change maybe Fayther Time's markin'

A notch in his stick as each yer ebbs away;

So pack up thi luggage, tha connot keep warkin'

If tha o'erdraws Natur, tha'll have to repay.

So come on to Blackpool, yo'll never repent it,

It's a rare bracin' place for owd folk an' young,

This invite's i' good faith, tha'll be glad as I sent

it,

It's a good salve for dumps to mix up wi' t'thrung.

It's a lovely sayside for rest or for pleasure,

Wi' th' waves rowlin' high or just lavin' one's feet;

Yo' may strowl upo' th' cliffs get health without

measure,

So come, an' durnt miss such a glorious treat. |

――――♦――――

ABEAUT BLACKPOOL; AN' REAUND

ABEAUT IT.

A Quire o' Nonsense wi' Some Meeonin' in it.

RECORDS FRO' TH' "BLACKPOOL

SOCIABLE

BROTHER'S CLUB."

THERE were a

grand doo at th' oppenin' o'th' Sociable Brothers' Club. We'd no

drink, except coffee after dinner, but there were plenty o' smookin'. When th' dinner were o'er, an' we'd getten settled after a toast an'

a sung or two, somebry started a discussion, altho' there were no

ajender, an' it turned on to Blackpool, an' th' way some o'th'

members went at it showed there were moor paddin' i' their yeds than

some folk would give um credit for.

It started through Joe Short axin me, bein' th' fust president, "Cornt

we get a better place nor this for th' Club meetins? It's so stuffy abeaut here, one cornt get his wynt. Let's get nearer th' say."

This were a surprise to me, for we'd a deol o' trouble i' gettin' a

reawm as would howd us, an' we weren't very far at th' back, so for

answer I axt: "Wheer would tha like us to goo?"

"Oh, annywheer but here," he said; "let's goto th' front. Blackpool's th' ugliest teawn i'th' country, an' this is th' feawest

part o' Blackpool."

A lot o'th' members yerd Joe, an' his words kindlet a fire, as th'

sayin' is, an' one or another added moor coal to it till we were aw

blazin' wi' excitement. Some o'th' members oppent their meawths wide

enoof to catch buzzarts in, wonderin' heaw I'd answer Joe. I hardly know'd what to say, but these words were th' hondiest I could think

on: "Joe, tha's gan us summat to think abeaut, but I should like to

know what tha meons when tha caws Blackpool ugly. Look at th'

Promenade; it's three mile lung, wi' three o'th' best terraces I

know on, an' I'm sure there isn't a wider or a cleoner i'th' world. An' look what big lodgin' heauses there is on th' front."

"I weren't tawkin' abeaut th' Prom or th' lodgin-heauses at th'

front, tho' I think they're moor harm nor good, for th' say air

cornt get at th' back on um," Joe remarked; "I said, an' I stick to

it, as Blackpool's th' feawest place I were ever in, an' I've bin to

Sawford an' Manchester at that. But no place I've bin to has such

narrow or cruckt streets; in no other place have I seen such lung

rows o' heauses, chuckt up ony road, as yo'll find here."

"Hear, hear," sheauted Sol Hampson, an' this seemed for t' encourage

Joe, for he went on: "Blackpool's like a cracked bell; th' meawth on

it is th' Promenade, an' when yo' get behind theer, yo'r lookin' for

th' clapper, an' get lost i'th' cracks."

("Good again," chirped in Sol.)

"An wheer's th' fresh air when yo' get in th' teawn. Th' streets are

like entries but entries are straight an' th' heauses are so

built as they keep th' say breezes eaut o'th' teawn instead o'

lettin' um in. I knowd a chap an' his wife as coom fro' Owdham for a

wick, an' they lodged in a lung row in th' middle o'th' teawn. Of cooarse th' air smelled a bit sweeter even theer nor it did i'

Owdham, an' they thowt they were gettin' say breezes every minute. But they weren't. They happened to have a very

weet time, an' they

had to sit in th' heause a good deeol, but th' chap spent his time

puttin' his hond through th' sittin-reaum window an' pluckin'

daisies off th' lawn (?) o'th' heause opposite. He said he'd enjoyed hissel', bein' a lover o' flowers. When they geet whoam again, after

dividin' th' Blackpool rock amung th' childer, which were soon put

eaut o'th' road, th' biggest lad went to his fayther, an' said,

"When are yo' gooin' to divide th' feesh?" "What feesh?" said th'

fayther; "we'n getten no feesh, my lad." Th' lad seemed doubtful,

an' he said: "Are yo' sure? Yo're Sunday clooas smell o' feesh all

o'er." An when th' fayther went an' looked at his Sunday suit th'

smell o' feesh an' oil nearly knockt him o'er. So, yo' see, if he

didn't get th' say breezes he geet th' smell o' feesh, nobbut it had

been fried.

"Then, again, wheer is there a buildin' i' Blackpool ut's worth

lookin' at. Th' finest piece o' architecture is that drinkin'

fountain in Talbot Square, an' that's made o' iron. That's seen at

its best when th' Salvation's Army's preichin' aside on it, an'

beggin' for pennies on th' drum.

"But I wurn't blame th' present Corporation for Blackpool bein' so

ugly, but they met do better. They'n a little bit o'th' North Shore

left, but even theer they'n let some builder as wanted to make brass

sharp build heauses like lung boxes, thirty in a row, an' as these

goo wit' th' front o'th' cliffs, what chance is there uv onybody as

lives at th' back on um gettin' ony say breezes, th' only things i'

Blackpool wuth ceauntin'? They corn't do it."

"Nawe, they corn't," sheauted Sol Hampson, "an' I con tell yo' heaw

Blackpool fust come to be speiled."

"Order!" I said, an' knocked on th' table, "let Joe finish."

"I were just gooin' to finish," Joe remarked, "by sayin' as there

weren't a dacent street i'th' teawn." There were a member sittin'

i'th' group as I didn't know very weel, but I'd yerd him cawd Jerry. He were a Owdham chap, but he'd coom a keepin' a company heause at

Blackpool. He jumped up just as Joe Short had finished he were

sharper nor Sol an' he said he agreed wi' Joe abeaut th' lung

rows an' narrow streets, but he did know of a dacent street or two,

an' he should like to tell us summat what he knowed, an' this is

what he towd us.

A Dacent Street.

Said Jerry: "A yer or two back my brother Bill coom to see me, an'

he stopped a tothri' days. He thowt Blackpool were a feaw place, an'

I wanted to show him he were wrung. So one day I took him up Church

Street on to Raikes Road, an' to th' reet o' theer there is a street

or two as up to then I thowt were railly dacent an' wide, altho'

they are lung rows. So we turned in one, an' a bobby stood at th'

corner.

"'Good mornin',' I said to him, an' he ansert very civil, but he

said, 'Durn't make a neise gooin' deawn here, for th' folk ull

complain if yo' dun.'

"So we walked on eaur tippy-toes, an' th' bobby coom wi' us.

'This

street looks a bit dark,' I says to him; 'I notice it gets very

little sun.' 'That's noan it,' says th' bobby, 'th' sun's not allowed

to shine here; if it did, I should oather lock it up or summon it.'

"'Well,' I axt, 'what's aw th' window blinds hauf way deawn for?'

'Oh,' he ansert, 'one o' th' wives o'th' Sultan o' Turkey deed last

wick, an' they're in mournin' for her. Th' folk abeaut here are

thick wi' aw th' Royal Families i'th' world.'

"'Then they mun be very rich,' I said. 'Rich!' said th' bobby, an'

he staggered wi' surprise at th' question; 'Rich! Why th' poorest

mon in this street is th' Cheermon uv a Brewery!' Th' bobby spoke i'

whispers.

"Just then eaur Bill turned to me quite solemn, an' said, 'Jerry, I durnt feel so weel; let's go back.'

'Aw reet, lad,' I said, an'

then I towd th' bobby, we thanked him, but we'd go back. 'Very weel,'

he said, 'but durn't mak a neise.'

"He turned back wi' us, an' as we geet to th' end o'th' street a

feesh cart were just comin'.

"'Wheer art gooin'?' said th' bobby to th' chap as were wi' it. 'I'm takin' some salmon an' soles to th' lady at th' fourth heause fro'

th' bottom. Hoo ordered it yesterday.'

"'Tha connot tak that cart deaun here,' th' bobby said, 'th' neise

o' that ud freeten um to deoth.'

"'Well, what mun I do?' axt th' chap.

"'Why, tha mun poo thy clugs off an' carry it," ansert th' bobby,

'unless tha likes to wait till twelve o'clock then there'll be two

looad o' sond comin' fro' th' shore to scatter o'er th' street.'

"'Well, but if aw wait here two heaurs th' feesh ull go bad.'

"'Well, then,' says th' bobby, 'poo thi clugs off an' carry it.'

"We left um at that, an' lookin' back, we seed th' chap, in his

stockin' feet, carryin' a looad o' feesh to th' lady at th' fourth

heause.

"'Well, Jerry,' said eaur Bill, 'if this is bein' a gentlemon i'

Blackpool I'd rayther be i'th' jenny-gate mindin' a pair o' mules.'

"'So would I,' I says, 'a workin' chap has summat to be thankful

for, after aw.'"

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

When Jerry set down everybody were lowfin' an' shakin' honds wi'

him, an' some were sheautin' "Good for thee, Jerry," that there were

a reg'lar tumult, as th' parson would say, so I thowt it best to

adjourn th' meeting. I promised Sol Hampson, heawever, as he should

be th' fust to speik th' wick after.

We'd a good muster at th' next meeting. Sol had written his lecture deaun, an' it were yezzy to see as he'd had th' dictionary at th'

side on him while he were writin' it, because there were some words

as I'm sure he didn't understond. But read his papper for yorsels;

it's here:

Th' Origin o' Some Nicknames, an' heaw Blackpool were Speilt.

"Afore I tell you heaw Blackpool were speilt I'st ha' to tell yo

abeaut th' peculiarities o' some Lancashire folk, an' heaw they coom

to be nicknamed as they are, for it were through th' peculiarities

o' th' Blackpool folk in days gone by as Blackpool were made so

ugly.

"Fust uv aw, I'll begin wi' Bowton. Afore their Teawn Ho'

were built it were th' Market Square, an' there were a Fair howden

there two or three times a yer. But in one corner o'th' greaund

there were often a penny circus, an' awlus a set o' dobby-horses. Thoos didn't wark by steom then, an' if a lad hadn't a haup'ny to

pay for a ride he met earn one by gettin' inside o' th' roundabout

an' helpin' other lads, as poor as hissel', to shuv th' horses

reaund. I've done it mony a time. But there were a chap walkin'

reaund eautside wi' a whip, an' if he catched a lad ridin' on th'

bars, or one not shuvvin', he'd skutch him. So, wi' turnin' these

dobby-horses so sharp Bowton lads geet in th' habit o' runnin',

awlus. An' th' wenches soon catcht th' complaint wi' runnin' after

th' lads. Childer coorn thick i' Bowton i' thoos days, an' faster

nor they were

wanted, an' if a lad couldn't get wark in th' teawn he'd trot off to

Manchester, get a job as errand lad, an' trot off theer an' back

every day, never loasin' a minute. Its nobbut twenty-four mile boath

roads, but, bless yo', that were thowt nowt on. Bowton lads o' that

generation were smart, I con tell yo'. I were one mysel', an' should

know. So th' folk were cawd Bowton Trotters, an' th' name's stuck to

um to this day.

"Similarly, as th' skoomester would say, wi' mony other places. Yahwood (but it's gradely name's Heywood), f'r instance, is called

Monkeytown, an' th' rayson for that is yezzy. There were a great mon

lived a while back named Darwin. He wrote a book cawd "Th'

Hevolution of Man," in which he tells us that a very, very lung

while sin', afore th' history o' Blackpool were wrote, men an' women

used for t' walk on their honds an' feet, an' they had hairy tails.

But by-an'-by th' men begun o' wearin' collars an' women fun' eaut

they looked better wi' bonnets on. So as they had to ston' up to

admire thersels i'th' lookin'-glass they geet in th' habit o' walkin'

on their feet. By doin' this regular their tails dropped off. Darwin cawd this hevolution. So they caw Yahwood th' Monkeytown because

folk theer hasn't hevoluted yet.

(A Vice: "Shut up wi' thy lies, Sol Hampson.")

This interruption, as th' dictionary would say, were caused by Sim

Nelson, who comes fro' Yahwood. He were regular mad till I explained

as they were what Darwin wrote, an' not Sol's opinions. It mollified Sim a bit, but Sol were disturbed. Heawever, order were restored, as

th' reporters say, an' Sol went on:

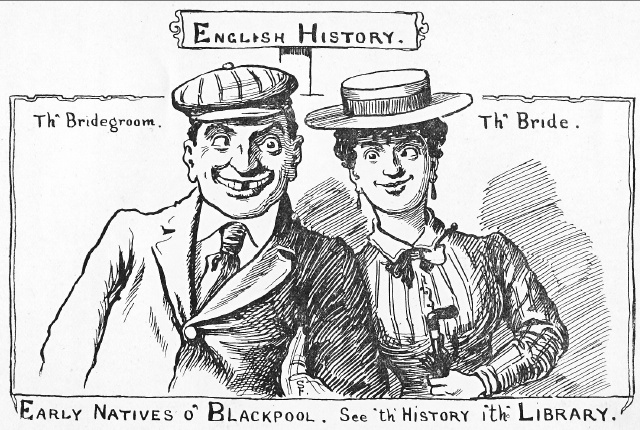

"Likewise, when Blackpool were young, an' th' childer could play

abeaut th' fields, an' breathe th' fresh air, th' sun used to shine

so very breet in th' clear blue sky, that th' childer, or th'

grown-up folk for that matter, couldn't stond th' brilliance, so

their eyes geet wake, an' some on um begun to sken. Neaw, if ony on

yo' ull stare at somebry as skens, yo'll not be lung afore yo'

squint yorsel, so yo' con yezzily understond as aw th' childer soon

begun to sken, an' they growed up that road. In cooarse o' time th'

natives coom to be nick-named Blackpool Skenners. So, when yo' see

anybody wi' a breawn face an' neck an' a gradely squint in their

e'en, be sure they, or their forbears, were born in Blackpool.

A Skennin' Local Booard.

"Well, a lung time sin', afore it were big enoof for a Corporation,

there were a election for t' Local Booard, an' as it turned eaut,

every chap as were elected, except one, skenned badly some wit'

reet e'e, some wit' left e'e, an' t' others wi' booath. Th' chap as

didn't sken were made th' cheermon, becos it were thowt he could see

as things went on straight. But when they were plannin' th' streets

there were such barjin amung um some thowt they should run fro'

reet to left, others thowt fro' left to reet, while thoos at

squinted wi' booath e'en thowt th' plans made th' streets too wide;

yo' see their vision, as th' skoomester would say, didn't stretch

across a yard measure that th' cheermon resigned, afeared he'd get

skennin' too. They geet a architect an' surveyor on th' street

plannin', but they booath skenned, an' th' ugly teawn o' Blackpool's

a monument to th' cleverness o'th' swivel-e'ed Local Booard.

"But they were i' earnest, for amung other great things they started

a Sewage Skeme, an' laid pipes i' th' streets, an' geet somewheer to

empty um. But th' next election put a stop to their enterprise, for

th' voters fun' eaut they were gooin to be let in for a big bill if

they didn't awter things, so they chucked every skenner eaut. Th'

new Booard were put in to keep th' rates deawn, an' as there weren't

mich need in thoos days for a big skeme, th' matter o' sewage were

shoved on one side, an' they let it stop theer.

"Neaw, as years went by, Blackpool geet fancyin' itsel', so they

went in for a Corporation, wi' a gradely mayor wi' a gowd cheean

reaund his neck to weight him in th' cheer, an' they geet what they

wanted. After straitenin' up things as weel as they could, an' th'

population growin' so fast, they fund eaut as they'd have to do

summat gradely to get shut o'th' sewage, so they said they'd finish

. . . .

Th' Sewage Skeme. . . .

. . . . as were started years afore by th' Skennin' Local Booard,

but they were in a mess when they fund as nobry knowed owt abeaut

it. Th' skennin' architect were deeod, an' th' surveyor had gone to

Australia, wheer he'd getten a job o' freetenin' rabbits, so they

couldn't ax them.

"I might just say here as Blackpool folk were gettin' rid o'th'

disorder o' squintin'. Wi' th' streets bein' built so narrow an'

cruckt th' childer as were born could learn to walk through um

witheaut bein' bothered wi' th' bonny blue sky, an' th' sun they

hardly ever seed, unless they walked on th' front, so their e'en

stopped as straight as when they coom i'th' world.

"Well, th' Corporation, as I said, were in a mess abeaut th' Sewage

Skeme, an' they begun o' diggin' somewheer abeaut Marton to see if

they could find any trace o'th' pipes, an' they'd build a

Destructor. But they dug here an' dug theer, an' findin' nowt, were

just gooin' to start a new skeme o'their own when th' pipes were

fund by accident.

"A visitor fro' Sawford coom o'er for a wick. He weren't used to havin' holidays, for th' fust day he coom he geet drunk, so folk

said, wi' Blackpool ale. If that were so, I'll bet a nut or two he

were fond on it, for I've yerd as in thoos days there weren't a

sowjer in th' British army as could sup hauf a gallon on it, an'

live. I've yerd as one time th' 'drink sellers offered a present of

a pint apiece to th' warkhouse folk for their Kesmusdinner, an' th'

Guardians thanked um for their kindness, but when th' poor paupers

yerd on it they sent a letter to th' Queen axin' her to make a law

to prevent th' Guardians fro' poisonin' um, an' th' Queen did. So th'

beer in thoos days mun ha' bin thick an' strung. It's better neaw, I

believe, but durn't sup too much on it.

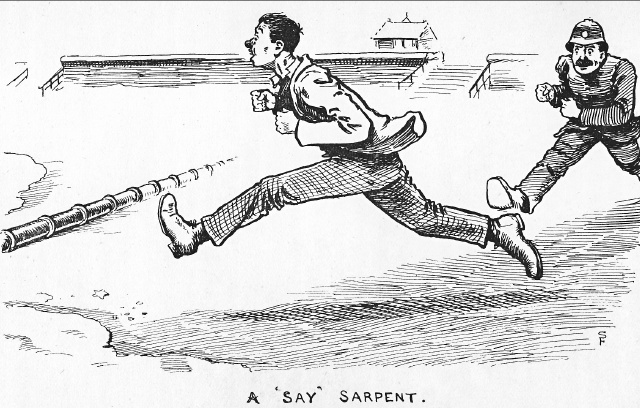

"Well, this visitor were up th' next mornin' at five o'clock, walkin'

abeaut th' South Shore wi' bleary e'en an' beery face, an' his tung

hangin' hauf road eaut uv his meawth, lookin' an' waitin' for a pub

to oppen, so as he could comfort his parched throttle. He were walkin' along th' front, an' th' tide were eaut a lung way. His

brains were addled, an' his throat were lumpy, but his nose were as

keen as his tung. In a bit he smelled summat, an' he knowed th'

smell. 'I'm not so far off Sawford Docks, I think!' an' he sniffed

hard. 'I should know that perfume.' Then he looked toward th' say,

an' he seed two hundred yards away summat trailin' in th' wayter,

till it geet lost to view. He started, shaded his een, an' then he

said, 'By gum, what's that? I've not seen that in Sawford; I wonder

what it is.' Then he looked harder, tryin' to make it eaut, an' he

thowt he seed it move. 'Why,' he said to hissel', 'it mun be th' say

sarpint.' An he rushed off, lookin' for somebry else to come an' see

it. He met a bobby abeaut where th' Central Pier is, an' he towd him

what he'd seen.

"Th' bobby ansert, 'Oh, we've yerd abeaut th' say sarpint afore. Every ship as comes to Blackpool brings a tale abeaut meetin' um. Thee go whoam an' go to bed; tha'rt noan thisel' this mornin'; some

sleep ull do thee good.'

"'Say-sarpint or not,' th' chap said, 'there's summat theer hauf-a-mile

lung, an I thowt I seed it move, but it mun be deeod, for there's a

smell comes off it. If it's not a say-sarpint, come an' see what it

is.'

"So they started back, an' th' chap's yed were a bit clearer by

this, an' he noticed th' bobby kept close to him, an' bein' a bit

freetened, he started runnin', but th' bobby kept up wi' him, an'

they were gallopin' full baz when they geet to wheer th' chap had

had his nose tickled. Th' thing were still theer, an' after th'

bobby had stood lookin' at it a while, an' had a strung whiff or two

off it, he clapped th' Sawford chap on th' back, an' said: 'I'm fain

theau browt me to see this, an' I know what it is. Thoose are pipes,

an' it's th' Sewage Skeme built by th' Skennin' Local Booard. It's

bin lost for mony a yer, an' there's five peaund reward for th' bobby

as finds it, so I'm off to claim it.' He started off runnin', but

when he'd getten abeaut fifty yards he turned reaund an' sheauted to

th' Sawford chap: 'It's nobbut ten minutes off oppenin' time. Th'

Manchester Arms is just across th' road; tha'll get a pint o' good

ale theer, if there is any. Good mornin'; see thee again.'

"An' that's th' tale o' heaw Blackpool fund their lost Sewage Skeme."

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

There were as much good humour when Sol set deaun as they were at th'

fust meetin', so I said we'd meet again at th' same time th' wick

after. Ned Nicklewood were brunnin' to tell us surnmat, an' when we

met next time he gan us this tale abeaut . . . .

A Skennin' Couple.

"A chap once towd me uv a skennin' couple fro' th' Fylde as coom to

Blackpool for their honeymoon. They booath skenned, but, what were

extraordinary, th' chap skenned wi' th' reet e'e, an' his wife wi'

th' left, so, as they walked arm-in-arm through th' street, they

stared at one another wi' one e'e beaut turnin' their yeds. They

lodged at th' side o' th' big wheel. One day they lost their bearins,

an' they fund thersels at th' side o'th' Hippodrome. Neaw, yo'll

remember, there's hauf-a-dozen streets facin' yo' fro' theer, an'

they aw lead to nowheer. Well, one peculiarity (as th' dictionary

says) abeaut this couple were that their seet caused a optical

delusion [He meant illusion Anoch Wragg, th' compiler art'

editor o' these important records]in each on um; f'r instance, th'

wife's left e'e made everythin' look as if it were to th' reet,

while her husbands reet e'e sent everythin' to th' left. As they

stood at th' Hippodrome they looked for th' big wheel, an', uv

cooarse, they soon seed it, but th' wife thowt it were to'art Uncle

Tom's, while th' chap made it eaut to be somewheer about St. Anne's. Heawever, they started up a street opposite, an' when they geet to

th' top they turned wi' th' street, an' come back to wheer they

started fro'. Then they tried another street, an' followin' reaund

th' corner o' that they just come back to th' Hippodrome. They went

up t'other street then, an' when they'd gone up an' reaund it they

were no better off. This were very disheartenin', speshally as they

could see th' wheel. There were still another chance o' gettin'

whoam, an' they dived deaun th' last oppenin' there were, an' this

time they fund theirsels aside o'th' Police Station i' South

King-street. They were gawpin' abeaut lookin' for th' road to th'

big wheel when a inspector were comin' eaut o'th' station, an' they

jowd agen him. They were excited, but th' chap had sense enoof to ax

th' inspector to show um th' road. Th' inspector stared at um, an'

seein' two eautside e'en lookin' into his brains, while two inside

uns were fixed straight on him, he thowt they were makin' faces o'

purpose. They couldn't make him understond they were lost, so he

took um into th' police office, an' were gooin' to lock um up for

insultin' him, when th' wife started o' cryin', an' th' husband at

last managed to explain as they couldn't help skennin', but they

were very sorry, an'th' inspector tumblet to th' situation in a

minute. So he leet um off, an' sent a bobby wi' um to th' big wheel

itsel'. When they fund their diggins they were so thankful they

offered th' bobby tuppence for his kindness.

"'Never mind, thank yo,' said he, for he hadn't liked th' job o'

bein' wi' um; "neaw as I've seen yo' whoam I'm moor nor paid. But

never squint at a inspector again; they wurn't have it. When yo' see

a policeman wi' braid on his cooat he's somebry an' durn't forget

it. Good day.'"

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

When Ned had finished his tale, there were so mony members jumped up

for t' say summat, that I could see we shouldnt get any forrarder,

so I cawd for order, an' to keep th' fun gooin', I wund th' subject

up like this:

"Joe Short's abeaut reet when he says as Blackpool's speilt wi' lung

rows o' heauses an' narrow streets, an' I'll tell yo' summat I

yerd a, while back as'll beer Joe's idea eaut. Six chaps coom o'er

one Owdhem Wakes, an' when they geet to th' lodgins wheer they

wanted to

put up at, th' lonlady could only tak three on um, but a friend of

hers as lived reet opposite fund room for t' other three. Yo' known

as th' Owdham Wakes fills th' teawn as full as th' October gales

fills th' wayter, so th' streets geet rayther stuffy, an' they had

to oppen th' windows when they went to bed so as to be able to

breathe. Of cooarse, as chaps will, they had some confab when they'd

put their candles eaut, but when they were ready for sleep they

couldn't catch it because everybody had lifted their windows oppen,

an' everybody could yer everybody else in th' street whisperin',

singing, an' snorin' till they had to get eaut o' bed one after

t'other to shut th' windows, an' th' neise were as bad as bedlam. Neaw these six chaps, as I said, were billeted in two lots opposite

each other one lot at No. 16, an t'other at No. 17. In th' mornin'

a chap at 16 knocked at th' bedroom window of No. 17, an' he said to

th' chap as oppend it, 'Ted, I've lost my collar stud. Han any on yo'

getten one to spare.' Ted axt um, but they hadn't one, so he went to

th' window, an' said, 'Nawe, Harry, we haven't; but here'a pin;

fasten thi dickey deann wi' that.' An' he honded th' pin through th'

window.

"That day happened to be a weet un, an' these chaps wanted to get

abeaut, an' chance th' weet, but Ted an' Harry were teetotalers, so

they let t'others goo, an' they stopped in. They geet slack for

summat to do to amuse thersels durin' th' day, so they bowt a set

o' chessmen. Neaw, as there were other folk, wi' childer, at booath

16 an' 17, they couldn't play in th' parlours, so they oppent th'

bay windows, an' put one end o'th' chessbooard on th' window-sill o'

No. 16 an' t'other end on th' sill o' No. 17. This were aw reet for

a table. They played for a lung while, an' Harry were just winning a

tight game when a young chap on a bicycle come dashin' up th' narrow

street. He didn't expect owt in th' road, so he run into th' chess

booard, an' sent one end on it tilting again' 'tother window wi' a

bang that broke aw th' glass, an' nearly knocked th' frame eaut. Th'

chessmen were lost, an' when th' bicycle felly coom to hissel he

were on th' floor, an' he didn't look as if he wanted for t' get up. He were a butcher's lad, an' when he looked for his basket an' meit

they were aw o'er th' street, an' as he gathered th' stuff up his

face were as raw as th' beef. Of cooarse there were a terrible row

o'er it, an' thoos Owdham chaps only geet eaut on it by buying th'

butcher's lad a new set o' teeth for thoose he'd knocked eaut, an'

they geet th' bicycle mended for two peaund. Th' lonlord charged um

fifteen shillin' for th' windows, an' th' butcher wanted

compensation for th' beef bein speiled, but he geet nowt, becos they

fund eaut as he sowd it for stew. Them Owdhamers awlus stop on th'

front neaw, an' when any fresh visitors goo for lodgins abeaut wheer

they lodged th' lonladies ax um if they play chess, an' if they say

'Aye' they wurn't have 'um."

"'Anooh,' said Sol Hampson, 'if I'd th' button I'd pass it on to'

thee.'"

"I thowt Sol were very insultin', so I said to him, rather savage,

'Sol Hampson, I durn't want thee to believe that tale, for I durn't

believe it mysel, but it's time tha'd had th' button, for tha tells

as mony lies as a Prime Minister. But I gan thee order, so be dacent,

an' shut up while I finish.'

"That quietened him, so I finished wi' this: 'We'n said a deeol

about Blackpool, an' we agree as th' teawn is raily ugly, but we

corn't help it. It's done, an' we're sufferin' for it, becos, altho'

folk come for their health, th' Corporation o' Blackpool, wi' only

seventy theausand folk, has to have as mony officers of health to

keep th' teawn aw reet as Manchester has, an' there's hauve a

million folk lives theer.

"Some day, when one or two o'th' doctors has made brass enoof to

speik their minds, they'll tell us it's not healthy to build heauses

in terrace fashion; that a poor mon has as much reet to have th'

wind blowing aw reaund his cottage as th' rich mon has reaund his

mansion, an' th' builder as wanted to put more nor four heauses in a

row should be made to swallow th' plans. I met as weel finish this

by sayin' as I'd sarve th' architect as draw'd such plans up same as

I'd sarve a mad dug shoot hirn."

Th' members agreed wi' what I said, an' they'd sayrious faces when

they left for whoam, for I'd gan um summat to think abeaut.

――――♦――――

A BLACKPOOL AUCTION, AN' WHAT COOM ON IT.

TUM Hamer lodged

wi' his brother Alick, who were wed an' had two childer. Emmer Hamer, Alick's wife, thowt awmust as much o' Tum as hoo did uv her

husbond, becos Tum were a mon o' few words, an' were yezzily managed

a whoam. He were quite happy when he'd done his day's wark, if he

could lie deaun on th' sofy, after his baggin', wi' a book, or goo

eaut for a walk wi' their Alick, which just pleosed Emmer, for hoo

knowed as Alick, who were rayther lively, were eaut o' mischief when

Tum were abeaut. Nayther o' th' chaps had other companions; they

were quite content one wi' th' tother. Last Wakes time Tum an' Alick

agreed to go to Blackpool for th' wick eend, becos Emmer didn't feel

fit to leove Bowton, as th' childer were gettin' reaund fro' th'

mayzles, an' hoo couldn't trust nobry else wi' um. Th' chaps booath

had mules at th' same mill, an' on th' Friday neet they started eaut

wi' leet hearts for th' shop wheer th' say breezes an' th' ozone's

sowd. I say sowd, an' I meon sowd, for yo' connot get um for nowt. Durn't try, or yo'll be sowd. Well, they geet good lodgins, an'

after a quiet evenin' abeaut th' teawn they turned in early to have

a full day on th' Saturday. They geet up betimes, an' after

breakfast they seet eaut for a good day's seet-seein'. They

enjoyed it raily weel till abeaut three o'clook, when it coom on

rainin' very hard. They'd noather top cooats nor umbrells, so

they had to run somewheer for shelter. In this road they geet

separated, as they went different roads. I durn't know wheer

Alick, th' wed un went, but as th' tale consarns his brother we mun

follow him.

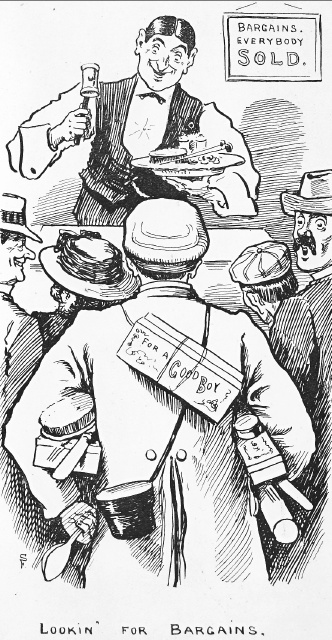

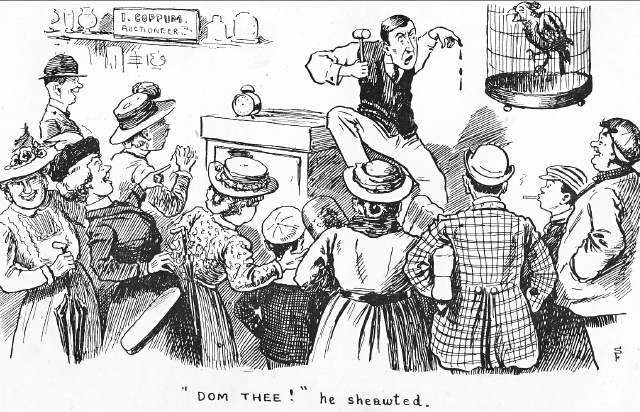

He yerd a auction chap's hammer bangin' on a booard, an' lookin' in

th' shop, he seed as th' sale were gooin' to start. He thowt he

might as weel shelter theer, an' have th' fun for nowt, an' watch

other sawneys as wanted bargains an' get summat gan um waste their

brass. That's what he thowt, an' there were a lot moor i'th' reaum

nussin' th' same belief, but these auctioneers who come to Blackpool

in th' summer know summat, an' if yo see one wi' a reaum full o'

bargain hunters tryin' toget th' best on him watch heaw he lowfs at

um at th' finish, for he's getten th' best bargain. These wanderin'

auctioneers creawd into th' watterin' places fro' July to September

Blackpool has aboon its share on 'um an' they tak' as much brass

eaut o'th' teawn as keeps um for th' rest o' th' year. This is bad

two roads: it's not fair to th' shopkeepers who live in th' place,

an' have to squeeze thro' th' tight winter as best they con; an'

it's bad for thoose who are so greedy as to want summat for nowt,

altho' I sometimes think, when I yer on um being sowd, that it

sarves um reet. An', another thing as I've noticed, wheer do aw

thoose foreign watches get to as are sowd by thoose auction chaps?

They're mooast on um bowt by trade union men. I reckon they're gi'n

to th' childer to play wi', when th' buyers find eaut what rubbish

they are. There's mony a theausand o' these sowd every yer in

Blackpool, an' if other sayside places sell um i'th' same

proportion, I'm of opinion as we British folk 'ud better waste eaur

brass on findin' eaur own a job nor givin' it to furriners who

durn't pay eaur rates an' taxes.

But I mun get on wi' my tale.

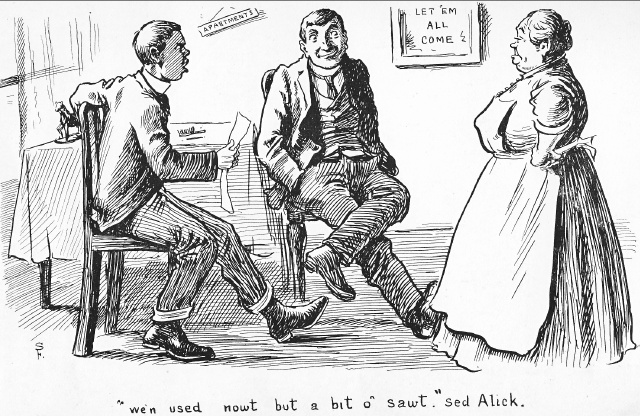

Tum Hamer went in th' auction reaum, as I said. Th' auctioneer had

just getten his sale gooin', an' havin' a lot o' gee-gaws to

dispose on, as bait to catch th' sawnies, he put up th' next lot

like this:

"Ladies an' gentlemen, I am goin' to show you how little I care for

money. See this penknife, best Sheffield steel blades, rivetted

through the head and foot, stag horn sides, with nickel-silver plate

on which to engrave your name. Now, who will give a penny for it."

"Me," sheauts a chap.

"Right, sir, here you are," an th' chap geet it.

"Here's a purse, best Russian leather, patent spring clasp, with

silver-plated engraved corners, suitable for either a lady or

gentleman. Its value is two-an'-six. My bid's a penny: who says tuppence."

Every woman in th' reaum shouted "Tuppence."

"Thank you. That lady there, Isaac " (that were to th' chap as

helped him), an' he honded th' purse to th' best-dressed woman in th'

reaum, an' who were likely to be his yezziest victim.

"I'm sorry I have no more," said th' auctioneer; "but these little

oddments are of no use to us." Then he rapped on th' table wi' his

hommer, an' folk as were passin' stopped to look, an' others comin'

in, th' shop were full in no time. Then he raised his v'ice, an'

filled um wi' stuffin like this:

"The firm I represent, ladies an' gentlemen, is one of the largest

in England. They manufacture most of the goods I sell, and they own

one of the richest mines in Africa. The governor says to me, 'Mr.

Goldstein, you are going among Lancashire folk. They're honest and

straightforward, so treat them as such, and, as we have got large

surplus stocks, let the good people have bargains.' Bargains! Bargains!! Yes, and I am here to give them to you. Now, here's a

pipe. Any gentleman wanting a good cool smoke can't have a better. Best briar, amber mouthpiece, solid silver-mounted and capped at the

top to prevent burning. My bid's a penny." Somebry sheauted tuppence,

an' he knocked it deawn.

Then he browt some breast pins eaut, an' he spotted Tum Hamer.

"You've forgotten," said he, "to place a pin in your neck tie this

morning. Will you allow me to present you with this rolled-gold

horseshoe pin; it will bring you good luck." An' he stuck th' pin in

Tum's tie. "An' you, sir," to another chap, an' in this road he gan'

hauf a dozen away. Then he browt tothri brooches eaut, an' gan' um

to th' women.

Folk by this time were gotten in a good humour, an' as that were

what th' auctioneer had been warkin' for he were moor than pleosed

wi' hissel'. But he hadn't done wi' um yet. After a joke or two, he

went on: "Now, ladies an' gentlemen, I'm goin' to show you a little

feat. I've told you why my firm has sent me here; but they wouldn't

have sent me if I weren't able to conduct their business in a

straightforward and honourable manner. I am going to put up twenty articles Here, Isaac (to his mon) bring me that tray an'

I'll undertake to clear the lot in half-an-hour, an' everybody shall

be satisfied. Are you satisfied, sir?" That were to th' chap as bowt

th' penknife for a penny. "Oh, aye," said th' chap. "And are you satisifed, lady?" to th' woman as geet th' purse. "I'm aw reet," she

ansert wi' a blush. "That's right," said th' auctioneer. Then he drawed his cuffs back, sent his fingers through his yure, and

raisin' his v'ice, he sheauted, "Yes, ladies an' gentlemen, I'll

sell the articles I'll put on this tray in thirty minutes, or I'll

present your local hospital with a hundred pounds. [They sen that

every yer, but th' treasurer av eaur local hospital is waitin' for

th' fust hundred yet. Anoch.] Here's a lady's handbag, No. l,"

said he, an' he put other things on th' tray till he geet to

nineteen.

"How many's that, Isaac," he said to his mon.

"Nineteen, sir," said Isaac.

"I thought there were twenty," said th' auctioneer, "but never mind. Here's a gentleman's watch, jewelled in nine holes, double capped,

centre balance, eccentric action, solid gold, worth ten pound worth

ten pound! but it will have to be sold. But I'll tell you what

I'll do: to encourage you, this beautiful tea and coffee service,

and this nickel-silver tea tray, shall be given away, without money

and without price (Hold it up, Isaac, an' let them all see it).

That will be absolutely given away. To encourage you to help me to

get through in time, every person who buys an article will receive a

ticket, and the lady or gentleman who has most tickets when the

twenty articles are sold will receive this most handsome present for

nothing" here he raised his v'ice again "this handsome tea and

coffee set positively for nothing!"

Th' folk in th' reaum were fairly bewildered (like th' flies in a

traycle can) at this mon's kindness, an' they stared at one another

wi' their meauths wide oppen, an' each on um made up their mind to

have that tay and coffee set, but they said nowt. When th'

auctioneer had gi'n um time to shut their meauths again, he started:

"Now, here's a handsome silver-backed hair brush and comb; pure

Potosi silver. How much?"

"Three shillin'," somebry sheauted.

"Thank yo'," he said, an' his lip curled up. "Go on."

"Four shillin'," fro' a woman.

"Thank yo', lady; go on again."

"Five." " Six."

"Six an' threepenoe," fro' Tum Hamer.

"No, I won't take threepenny bids," said th' auctioneer. "Six

shillings; any advance. Going."

"Six an' sixpence," fro' a corner o'th' reaum.

"Who'll say seven. Be quick, please."

"Seven shillin'," sheauted Tum Hamer.

"Seven; going at seven. Going ."

Then th' hommer dropt, an' Tum Hamer geet th' brush an' comb an' a

papper ticket wi' number 1 on it. That brush an' comb met be worth two shillin'.

"Now, here's a pair of opera glasses worth thirty-five shillings. Special double-crystal lens; will carry twenty-eight miles; suitable

for a captain of a ship, a general on the battlefield, a sportsman

at the races, or a lady at the opera. Who'll start me at five

shillings?"

Nobry seemed to want a opera glass. Then he spotted Tum Hamer. "You

bid five shillings, sir, an' it shan't cost you five shillings." Tum

hesitated. "Go on, sir, say five shillings," an' Tum bid five. He

knocked it deaun to him, and when he honded it deaun there were a

fancy fountain pen wi' it. "There," said th' auctioner, "I told you

they shouldn't cost you five shillings. That fountain pen is worth

ten shillings." Tum believed him, but it were nobbut wuth sixpence. An so th' sale went on. Tum bowt, amung other things, a pair o'

Marley horses, a kitchen clock, a lady's handbag, a watch an' cheean,

hauf-a-dozen knives an' forks, an' summat else, an' awtogether he'd

seven tickets, an' he'd spent o'er three peaund. Then' th'

auctioneer had sowd nineteen articles, an, he'd above ten minutes to

spare, so he leoned on th' bench, an' said, "All you who have got

tickets hold up your hands." They did as he axed um, an' he said to Tum Hamer,

"How many have you, sir?"

"Seven," answered Tum.

"Well, I'm going to reward you for your pluck. Here's five shillings

for you." Tum took it, an' thanked him. "Five shillin' an th' best

chance o'th' tay an' coffee service," thowt Tum; "this is better nor

warkin'." Th' auctioneer then gan' a bit o' brass to th' tothers as

had getten tickets, an' as they didn't expect owt o'th' soart they

were mighty pleosed wi' theirsels, an' were sure th' auctioneer were

very rich an' extra kind. But he'd hardly done wi' um yet.

"Now, ladies an' gentlemen," said th' auctioneer, "we come to the

twentieth lot, an' I've about nine minutes in which to sell it. This

solid eighteen-carat rolled gold hunter watch, capped an' jewelled,

regulator balance, real lever, is valued at fifteen guineas, but I

don't expect to get its value here. You've helped me very well, so

this is to be the best bargain, and the last of the sale this

afternoon. Who'll start me at five pounds." There were no answer to

this, an' th' auctioneer tried again.

"Will anybody say three pounds?" No answer.

"Well, see here," he went on, "this shan't keep me much longer. I'll

tell you what I'll do: the person who is fortunate enough to get

this solid eighteen carat rolled gold watch shall go away satisfied,

so give me a start. I'll give to the purchaser of it fifteen tickets

for the free gift of this magnificent tea an' coffee set."

There were a dropping o' jaws when he said this, for Tum Hamer an'

another chap wi' seven tickets apiece made sure nobry else ud come

near um, an' they'd have to toss up for th' tay an' coffee set. Tothri chaps i'th' reaum as ud bowt nowt lowft a bit, but selfish

folk awlus do when they think yo'n bin had.

Well, th' biddin' started at a sovereign, then somebry said two

peaund, an' th' biddin' run up to five peaund, when th' auctioneer

knocked it deaun to a woman. Hoo towd somebry near her hoo weren't

wed, an' no sign o' bein', but I reckon hoo thowt if hoo bowt a

hunter hoo might run deaun a chap as quarry, an' he'd wed her.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Tum Hamer gathered his stuff up, en' it were too much for t' carry

under his arm, so he put it at front on him like a big drum, an'

marched off to his diggins. When Tum geet theer Alick were havin'

his tay, an' he oppent his e'en when he seed th' donkey-load o'

stuff Tum had browt. "Wheerever hasta bin, an' what hasta getten

theer?" he axed.

"Why, when I lost thee I went in a auction-reaum to get eaut o'th'

weet, but I'm a bit too dry neaw, an' I reckon I'st have to be so

till I get whoam."

"What dosta meon by bein' dried up?" axed Alick.

"Nowt; only I'm spent up wi' gooin' in yon auction reaum.

I'st have

to borrow a peaund off thee till we get whoam."

"Borrow a peaund off me! I haven't one; it's moor nor I had to come wi'! I shouldn't ha' come but for keepin' thee company. Tha' knows

I've four folk to find grub for, an' tha's only thisel', an' tha

gets as much wage as me. Eaur Emma towd me tha wanted me to come,

an', as hoo'd nowt to spare, hoo said tha'd lend me what I were

short on."

"If I'd known that I shouldn't ha' gone in," Tum said sadly.

Alick looked at th' stuff on th' table, an' then axed,

"Heaw mich hasta spent on these things?"

"Abeaut four peaund, but its chep. I've just six bob left," was Tum's reply.

"Well, that caps aw!" said Alick. "We corn't stop here till Monday

afternoon wi' empty pockets. What's to be done?"

"I durn't know," ansert Tum, scrattin' his yed.

"We'st ha' to go whoam to-neet, I reckon."

This seet um booath thinkin', an' after a bit Alick spoke: "Well,

it's a good job I'm wed, for a chap larns by that heaw to get eaut

o' mony a scrape. Th' best thing we con do ull be to caw th' lonlady

in, an' ax her if ho'll buy some o' that stuff off thee. Happen hoo

will, if tha'll let her have a bargain."

A Chat wi' th' Lonlady.

So they cawd Mrs. Smith in, an Alick towd her what a foo their Tum

had made uv hissel' at th' auction reaum by spendin' aw th' brass he

had, an' axed her if hoo'd buy th' pair o' bronze Marley horses an'

a marble clock.

"Eh, nawe!" hoo sheauted; her face gooin' red in a minute; "I want

nowt o' that sort. I wouldnt ha' such rubbitch as that i'th' heause. I've seon it afore, an' so has every lonlady in Blackpool. Neaw an'

again a felly comes here, as shouldn't leove whoam beaut a woman

for t' tak care on him, an' he gets in one o' thoose auction-rooms,

an' lets um kid him to part wi' aw he has, an' when he comes to his

lodgins he bethinks him he hasn't enoof laft to pay his road."

"But," said Alick, "we'st not owe yo' so much if we stop till

Monday, an' if we goo whoam to-neet my wife ull have a fit. We'st

ha' to tak um to th' pawn-shop if yo' worn't have um, that's aw."

"Well, tak um," said Mrs. Smith, "an' yo'll find there's no

pawnbroker in Blackpool ull have owt what's come fro' th' summer

auction-rooms."

"Heaw's that?" axt Tum. It were th' fust time he'd spokken.

"Why, becos they're worth nowt. Heaw much hasta gan for th' Marley

horses, an' th' clock as winnat goo?" axt Mrs. Smith, after that

saucing.

"Twenty-eight shillin', said Tum.

"Twenty-eight shillin'!" an' Mrs. Smith were a while afore hoo could

tak her breath. "They're not worth hauf on it; they're only painted

tin. I durn't want um," an' hoo were beauncin' eaut o'th' reaum when

Alick cawd her back.

"Will yo' lend us a peaund on um, an' we'll send yo' th' brass forum

when we get back?" pleaded Alick.

"Nawe, I'st not!" said Mrs. Smith, "they're not worth it. I'll land yo' six shillin' on th' lot; but if I do it'll have to goo to'rds

what yo'll owe me, an' I think yo'd best pay me neaw, an' then I'st

be sure yo' corn't goo in th' auction-room again."

Alick didn't like this, becos he'd had nowt to do wi' it, but he put

th' best face on it he could. "Well, if that's th' best yo' con do,

we'st ha' to agree," he said, "but yo'll let us ha' th' goods back

for six shillin' if we send it yo' when we get back?"

"Of cooarse I will, an' be glad to get shut on it," ansert Mrs.

Smith. "If I were yo, I'd shuv um into a' auction awhoam,

particularly th' clock, or else it'll leg yo' deaun. When we fust

coom here a young chap were stoppin' wi' us an' he did just as yo'n

done to-day he wasted aw he'd getten. Among th' tackle he browt in

were a clock just like this. [But I'll sit me deaun while I tell yo'

this Umph! Theighur! That's better.] Well, we wanted a clock, so my husbond felt sorry for th' lad, an' we bowt it at hauf th' price

he'd gan for it. That looked like a bargain, didn't it? Well, wait a

bit. We seet it gooin' by th' Teawn Ho' clock, an' we went to bed

for th' lungest neet's sleep we ever had. It lost abeaut forty

minutes in th' hower, an' turned to-morrow into yesterday. My husbond wakkened at three by th' clock, an' it were too early for t'

get up, so we had another snooze, an' we were wakkend by th' rattlin'

o' milk cans. He geet up then, an' th' clock struck eight, but when

he went to oppen th' dur for th' milk, th' chap said, 'Do yo' want

any extra to-neet? I couldn't make yo' yer when I knocked this

mornin'. 'Goodness me,' said my husbond, an' he oppent his e'en

wider an' felt if th' bit o' yure he wore on his nob were still

theer, 'what time is it ?' Th' milkmon looked at his watch, an'

said, 'Why it's ten minutes past four i' th' afternoon.' It were no

use him puncin' that clock up an' deaun th' room, but he did, an' to

save his toes I picked it up an' throwed it in th' ash-bin. But my husbond welly geet sacked, an' th' teawn were

flooded two days

through that clock."

"It were a pity yo' bowt th' clock," said Alick.

"It were that, an' th' visitor we geet it fro' went oft whoam th'

day he sowd it to us, or else eaur Daniel would ha' brokken his

neck."

"Um. What did yo'r husbond do, Mrs. Smith?" axed Alick.

"Oh, he were a tide-turner for th' Corporation," hoo ansert.

Tum had been listenin' to this talk wi' his meauth oppen, but he'd

never yerd of a trade like that afore, so he axed her, "What is a

tide-turner?"

"Why," said Mrs. Smith, "he's a chap as watches th' tides come in,

an' when it gets as high as th' Corporation wants it to goo, th'

tide-turner turns th' wayter off, an' th' tide goes eaut. If yo'll

notice in some o'th' shop windows there's a fresh papper in every

day sayin' heaw high th' tide ull be, an' th' Corporation wurn't

allow it to get any higher."

"Well, I never yerd nowt like that," said Tum,

"Yo' larn moor as yo' talk to folk. Is yo'r husbond tide-turnin'

yet, Mrs. Smith?"

"Eh, nawe," said Mrs. Smith, "he's been deeod above five yer. He

deed at Simblin' Sunday, nineteen-hundert-an'-one."

"Poor chap!" said Alick, "what a pity."

"Aye, it were," an' Mrs. Smith seemed pleosed at th' sympathy, for

hoo' lifted th' corner uv her white brat up an' wiped a tear fro'

her left e'e; "as good a mon as ever lived, an' he wouldn't cruush

a worm."

Mrs. Smith were very much affected, an' that e'e wheer th' tears

coom fro' were soppin' weet, an' a corner uv her brat wanted

squeezin' when hoo'd talked a bit. But hoo liked dwellin' on her

trouble.

There was a little pause just here, then Mrs. Smith said, "I'll show

yo' his memory card, an' I'll bring yo'r bill at th' same time."

When hoo'd turned her back, Tum said to Alick, "Dosta think yon

woman's truthful? Hoo's gan us plenty o' gas for th' six shillin'

hoo'll strap us. An' I noticed when hoo were troubled an' cried

abeaut her husbond th' tears aw coom fro' one e'e."

"Well, I noticed that mysel'," said Alick, "but lonladies at th'

sayside are that road; they keep one e'e wi' a tear or two ready

for sympathy, but they keep t'other e'e awlus dreigh for business

purposes. Watch her when hoo comes back, an' tha'll catch her winkin'."

Alick had hardly getten th' words eaut uv his meauth when he yerd th'

seaund uv her feet. Hoo coom in, an' planked hersel' deaun on a

cheer. "Here's my husbond's memory card. Mun' I read it yo'?" an'

witheaut waitin' for a answer, read it like this:―

|

IN LOVING MEMORY OF

DANIEL EBENEZER NATHAN SMITH,

Who, after a troublous life,

Left his home an' left his wife,

AN' DEED APRIL,

FUST, NINETEEN-OUGHT-ONE.

Th' owd brid's flown away fro' th' nest,

He's flown to heaven to get some rest;

If he'd fly back I'd have nowt to fear,

For I'd all as I wanted when he was here. |

"Th' po'thry's mine," said Mrs. Smith, proudly; "dun yo' like it?"

"Aye," replied Alick, wishin' to cooart her favour, "it's very

good."

That were th' answer hoo wanted, so hoo went on, "I put it in th'

papper, an' when I axed him heaw mich it would be, th' gentlemen

behind th' ceaunter said, 'Well, eaur usual price is four shillin',

but this po'thry's so good we'll put it in at half price.' So I paid

him, and bid him Good-day, when he said 'Yo' should goo in for

writin', Mrs. Smith, an' if any o' yore friends dee, if yo'll write

a verse as good as this, I'll put it in th' papper at th' same

price.' . . Would yo' like a memory card?"

"Aye, we should," ansert Alick, "we want summat o' that soart to

cheer us up just neaw."

"Well, then, tak this," an' hoo honded it to him. Hoo shaped for

leovin' um then, but rememberin' hersel', turned back, an' said,

"I'd liked to ha' forgetten; here's yo're bill."

Alick took it, an' read: "Bed, three neets, 7s. 6d.; cruet, 6d.;

milk, 6d.; pratoes, 6d.; boots, 9d.; Sundays dinner for two, 3s.;

total, 12s. 9d." This awmost made him sweat, not as it were dear,

but he thowt o' th' funds. "I see yo'n getten sixpence deaun for th'

cruet, what does that meeon?"

"It's for th' mustard, saut, alecar, an' pepper," said Mrs. Smith, .

"But, we'n used nowt but a bit o' saut," Alick said.

"Well, it's bin theer for yo'," replied Mrs. Smith; "when Selina, th'

servant, took th' cruet off th' table this mornin', she said, 'Mrs.

Smith, yon two chaps come fro' Cheshire, wheer th' cheese is made. They'n not touched th' mustard.'"

"But we durn't come fro' Cheshire," broke in Tum, "we come fro'

Bowton."

"Dun-yo!" she said, surprised; "well, well; yo're th' fust Bowton

chaps I've ever had stoppin' here as didn't empty th' mustard pot th'

lust meal . . . . That accounts for it; tha'd ha' never gone to yon

auction reaum if tha'd etten some mustard."

Just then th' servant browt Tum's tay; he were nearly famished, for

Mrs. Smith's chatter had kept him waitin', an' seaside lonladies

aren't awlus in a hurry, unless th' heause is full; then they want

some on yo' eaut o'th' road.

Alick an' Tum discussed th' bill, an' they clubbed together, an'

cawd Mrs. Smith in. They paid her, an' they'd one-an'-ninepence left

to carry um on till Monday afternoon.

"I hope yo're satisfied," said Mrs. Smith, sittin' deaun facin' Tum,

"an' yo'll come again. An' yo'll send for th' ornaments when yo' get

back. Happen tha'll be wed by then." (This were to Tum, an' he

blooshed). "When my husbond were livin' he used to goo eeut recitin',

an' when he went to at tay party, wheer there were young folk,

they'd awlus sheaut for him to say 'Th' Lines to a Batchelor.' It

met hu' bin writ for thee. It were his own po'thry, an' they did

like it. I'll say it for yo'." An' hoo brested off wi' this:

|

Why, foolish mon, doesnt the get wed?

Tha'd be better off if tha were dead,

Nor livin' saingle;

There's mony at less would be thi wife,

An' comfort thee aw through thi life,

An' never wrangle.

Art' not tired o' livin' so,

I'th' midst o' misery an' woe,

Aw thi deiys?

The'd ruyther awter, I con tell,

But tha'll trust nobody but thisel',

Tha's such quare ways.

Tha never knowed affection's bliss,

Or th' love contained in one sweet kiss,

Not tha indeed;

The coom i'th' world for t' do some good,

An' not be like a block o' wood,

Or some bad weed.

Tha's no wife's cheer for t' make thee glad,

Or little childer t' caw thee dad,

An' comfort thee;

An' so, wi' awlus bein' alone,

Tha does nowt nea but sigh en' moan,

An' thus tha'll dee.

If tha were sick, neaw what would t' do?

The'd happen have to th' warkheause goo,

An' risk thi life;

An' who would soothe thi achin' yed,

Or keep thee warm ut neet i' bed,

As well's a wife.

In times like thoose hoo'd be thi friend,

Her labours then would ha' no end,

Till tha geet weel;

Tha'd find tha'd not geet wed in vain,

For hoo'd be th' fust to soothe thi pain

Thy sores to heal.

Tha'rt not like folk we see aw reaund;

Thi misery poos thee deaun to th' greaund,

An' makes thee ill;

Just get a wife thi path to cheer,

An joys ull creawn thee while tha'rt here

Tha'll ha' thy fill.

Tha looks so sour tha freetens folk

Thi face weren't made to crack a joke,

It looks too feaw;

I think it hasnt wore a smile,

Or lowft or grinned for mony a while

Has it neaw?

Such folk as thee owt ne'er be born;

Folk pity thee, tha looks forlorn,

Ah! thats quite true;

Neaw just thee wed some bonny lass,

Hoo'll tend thee well an' save thi brass

Tha'll never rue.

Women pints at thee wi' shame

"Theer's a bachelor!" what a name

For any mon;

Neaw tak' advice afore its late,

An' goo an' get a gradely mate

I know tha' con.

Thi troubles then will have an end,

For hoo'll be to thee a worthy friend,

I know hoo will;

For woman's worth is in her breast,

An' everythin' hoo schames for th' best,

Wi' her skill.

|

"That's th' eend on it," said Mrs. Smith; "dus ta like it."

"It's very good," said Alick; "han' yo' a copy on it to spare."

"Nawe, I haven't, it's not been printed; but I'll write it eaut for

thy brother if he likes," an' hoo looked at Tum wi' one o' thoose

fause smiles as th' sex larn when they're babbies an' practice till

they dee.

Tum seed through it, but he'd listened to th' po'thry, an' some on

it had settled in his nob, as we shall yer moor abeaut. He stretched

his arms eaut, an' gaped, an' said to Alick, "Let's have a bit uv

a walk. We'st see nowt sittin' here."

"Aye, do," said Mrs. Smith; "an' I'd forgetten, I've some marketin'

to do."

Heaw they Managed beaut Brass i' Blackpool.

When Alick an' Tum geet in th' street they felt lonely someheaw, an'

they kept their honds in their pockets to howd that one-an'-ninepence

deaun. They walked past th' Palace an' th' Tower mony a time on th'

spec o' seein' somebry fro' Bowton as they knowed to borrow a tothri

shillin' off, but, as generally happens at such times, nobry o' that

soart passed. They hadn't spokken to one another aw th' time, an'

noather on um knowed wheer they were gooin'. Abeaut ten o'clock they

were feelin' hungry, but there were some schamin' to be done afore

they dare touch their capital. They were passin' a shop wheer there

were potato pie in th' winder, steamin' hot, when th' nice smell

pood um up.

"I'm hungry," said Alick, "an' I mun ha' summat to eit."

"Aw reet," said Tum, "let's ha' fourpennorth o' prato pie apiece,"

an' they went in. It were good, they thowt, an' they could ha' eaten

a lot moor but for th' funds bein' low. They'd only tharteenpence

left.

Alick bethowt him on th' road whoam as his bacca were done, an' as

Tum had noan to spare, he had for t' spend threepence on an ounce o'

twist, an' that laft um wi' tenpence.

"Th' brass is fairly flyin'," said Tum; "I'm feared we'st ha' to goo

whoam to-morn."

"Well, we cornt help it," replied Alick; "I've pent nowt; it's thee

to blame."

"Well, it's my own brass," said Tum, "surely I con do as I like wi'

my own."

Alick said no moor, for he could see as Tum were a bit nettled, an'

if he hinted again perhaps they'd have words. So they went whoam,

an' were not lung eaut o' bed.

On th' Sunday mornin' at breakfast time they had to plan heaw to

spend th' day. They were booath good livin' chaps, if they weren't

teetotalers, so Alick said to Tum:

"We daren't go to chapel, becos we corn't afford to put owt in th'

collectin' box. Heaw would it be if we spent th' day on th' sands. We can yer th' preitchin' theer, an' it's only place as I know on

wheer we con get religion for nowt."

Tum could think o' nowt better, an' abeaut ten o'clock they were

stondin' aside o'th' Salvation Army, listenin' to th' band an'

tothri testimonies. They'd getten so interested as to be thinkin'

abeaut nowt else, when a young woman wi' a poke bonnet started

collectin' just wheer Tum were stondin'. Hoo offered th' box to him

th' very fust, an' he couldn't forshame to let it pass, so he put a

penny in. Alick twigged her comin', an' he backed eaut o'th' creawd

for a bit. After bein' theer a while lunger, th' captain cocked th'

big drum on its end in th' middle o'th' ring, an' as they'd seen

that done afore, they knowed what it meant. They'd nothin' moor to

spare, so they went away.

After dinner they turned eaut again, but they kept clear o'th'

Salvation Army. They went to another stond, but they were no better

off, for th' cadgin' begun theer, so they edged off to another

place, an' feared uv a collection, they kept eautside o'th' crowd. They spent moor time in dodgin th' collectin' box nor what they geet

good fro' aw th' sarmons they'd yerd.

Monday mornin' were railly grand, such a day as would make a healthy

chap feel as he'd like to live for ever.

"I wish it were four o'clock," Tum remarked, as they were havin'

their breakfast.

"What for?" axed Alick. "If we'd a bit o' brass I could do

wi'

bein' here a month. Look what a bonny mornin' it is."

"Th' mornin's aw reet," said Tum, "but what con we do wi' ninepence

between us, an' th' lonlady pooin' such faces as hoo does. We met be

beggars."

"Oh, tak no notice uv her," said Alick, "tha doesn't know women as

weel as I do. It's thy fancy; I fund her aw reet. Perhaps she thinks tha'rt a foo', an' I corn't blame her."

"Well, I feel it keen enoof, Alick Hamer, an durn't think tha's any

reason to fancy I'm gooin' to be insulted wi' thee," an' Tum were

riled.

"I didn't meeon to insult thee, Tum," said Alick, "but tha' imagines

things. Mrs. Smiths aw reet, but hoo towd thee plain enoof as chaps

as coom beaut their wives or wenches did make foos o' theirsels

betimes."

"Well, drop it, she said enoof; durn't thee bother any moor abeaut

it."

Alick had sense enoof to say no moor, an' after a bit, when his

temper had cooled deaun, Tum axed,

"Wheer mun we spend th' mornin'?"

"Well, I think we'd better goo on th' North Pier, that'll nobbut be

fourpence for booath on us. We con sit an' yer th' band, an' theres

no collectin'."

That were Alick's suggestion, an' Tum readily agreed.

They spent th' mornin' theer, sittin' smookin' an' listenin' to th'

music, but at th' interval Tum said to Alick, "I could do wi' a sup

o' ale, but there's only fivepence left. Heaw con we manage it?"

"There's only one road I con think on," ansert Alick; "we'll go to

th' refreshment pavilion together. Thee order a glass uv ale, an'

sup hauf on it; then come eaut. I'll watch thee, an' then nip in,

an' sup what tha's left. We'st ha' to do it that road, an' then

we'st have twopence-hau'p'ny left for two gills when we get to

Bowton."

An' they did this. It weren't very much ale for two strung men, but

it livened um up a good deal; it left a thirst behind it, heawever,

so as when th' concert were o'er they had to goo to th' bar again

an' spend th' last coppers they had, joinin' at th' beer as they did

afore.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Blackpool stations are wolly awlus creawded in th' summer, an' there

isn't much difference between th' folk as are comin' in an' thoose

at are gooin' away. They aw seem happy. Folk that are gooin' whoam

have friends seein' um off, an' they're merrily chattin' while th'

barriers are oppend. Then they shake honds, an' th' friends ull say,

"We're sorry yo're gooin'," an' they awlus get ansert, "An' we're

sorry to go; but, ne'er mind, we'st come again next yer!" An' they

keep their word. Then when th' train leoves th' station they wave

their honkerchers eaut o'th' carriage windows to their friends, an'

smile at um till they con see um no lunger. Then they sit deaun an'

joke an' sing all th' road whoam. Th' fresh air's made um lively an'

strung. They dunnat forget th' pleasure they'n had, an' as th'

months rowl reaund they keep filled wi' th' pleasant hope of another

good time to be spent in th' jolliest place in England, wheer

anythin' con be bowt, an' wheer there's no restriction on anybody's

liberty so long as folk behave. Good, cheery Blackpool, awlus young,

an fresh every time one comes to it!

Alick an' Tum geet to Talbot Road Station in good time, an' they

were th' only deaunhearted pair in th' creawd. When th' barriers

oppend they made for th' train, an' geet a compartment to theirsels

at fust, an' Alick stood at th' window as folk coom through th'

barrier.

"Why, here's Jane Barnes, thy big piecer, wi' Alice Atherton, an'

David Strung an' his wife," he said to Tum, who geet up to look.

"Hello, Dave," said Tum, "heaw arta? When did yo' come?"

"Oh, I'm A1," ansert Dave; "we'n bin here aw wick. Han yo' reaum

for us in theer?"

"Aye," said Tum, "come in."

When th' dur were oppent, Jane Barnes an' Alice Atherton had getten

to th' carriage, an' Alick said as there were reaum, so they geet

in, an' they'd compartment to thersels. Jane Barnes sat next to Tum,

an' Alice Atherton next to her, while Alick an' Dave an' his wife

sat on th' opposite side. Tum were pleosed wi' this arrangement, for

thoos lines in Mrs. Smith's doggerel

|

"There's mony a loss ud be thi wife,

An' comfort thee aw through thi life," |

had been runnin' through his yed since hoo said um, an' for th' fust

time in his life he were interested in women's company.

When th' train geet gooin' Jane oppent her satchel, an' pood a bag

o' chocolate eaut, an' offered it to Tum. He took some, an' hoo

honded th' bag reaund.

Tum felt moor comfortable then nor he had done since he left Bowton. Jane had worked wi' him ever sin' hoo were sixteen, an' he'd never

noticed th' change in her fro' girlhood to womanhood. He'd never

seen her dressed up afore, for hoo wore clugs at her wark, an' her

brat were so made to cover her that he'd not had th' chance o' seein'

heaw shapely hoo were. But neaw, as hoo honded him th' chocolate, he

noticed heaw cleon an' bonny her taper fingers were, an' as he

lowered his yed, an' could see her feet in nice-fitting shoon, he

thowt heaw dainty an' leet for trippin' they looked.

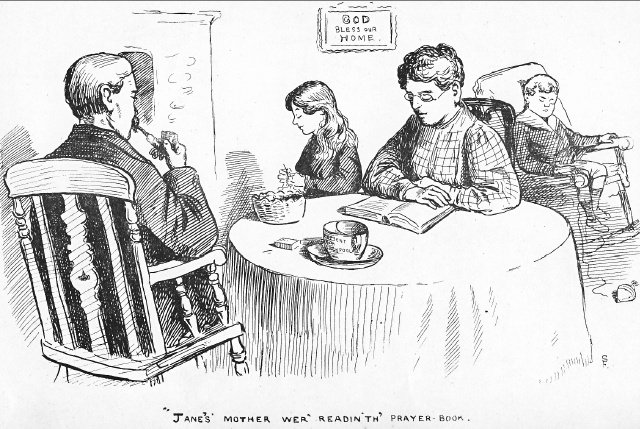

In a bit hoo pood a net bag off th' rack, an' hoo spread th'

contents on her knee, an' hoo axed Tum, wi' pleasure in her e'en, if

he liked um. "I'm takkin' um aw presents," hoo said. "This hummin'

top's for eaur little Alf. It's a nice un, isn't it."

"It's a beauty," agreed Tum.

"This wark-basket's for eaur Nelly. Hoo's in th' sixth standard, an'

her taycher said she must ha' one."

"That's very useful," said Tum

"An' I've bowt this Prayer Book wi' big print for my mother; she

corn't see so weel at church in th' gas-leet. It's nice, isn't it? An' I've writ her name in it, sithee:

'A Present from Blackpool for

my Dear Mother, from her Loving Daughter JANE.'"

"That's grand," said Tum, an' Jane were pleosed as he admired it.

Jane chuckled as hoo undid th' last parcel, an' hoo held it up for

everybody to see it. It were a mustache cup, as big as a basin, wi'

a saucer th' size of a plate. "This is for my fayther," hoo said,

"an' weren't he loff when he gets it?"

"He will that, an' I'm sure anybody would," ansert Tum. An' then in

a lower v'ice he axed her, "An' what hasta bowt for thisel'?"

"Oh, nowt," replied Jane; "I couldn't afford. Besides, I didn't want owt. We're not rich at eaur heause, but we're very comfortable."

"Does tha mind tellin' me heaw much aw th' lot as cost thee. I'd

like to know so as I shall know heaw to spend my brass." Tum were

anxious.

"Twelve shillin'," ansert Jane. Tum were fairly disgusted wi' hissel'. Here were a woman as warked for him could spend a bit o' money like

that on things as were useful an' would delight a heauseful o' folk,

an' make um happy, while he'd wasted four peaund on a lot o' rubbish

that were o' no sarvice to anybody, an' he'd made hissel miserable.

Alice Atherton then pood her presents eaut, an' hoo'd spent her brass

to as much advantage as Jane. Tum leoned o'er to look at um, an' he

were closer to Jane nor ever he'd bin afore, an' he kept so aw th'

road to Bowtun.

Ah, Tum, if tha'd only known! There were a little angel, o' mon's

creation, hoverin' o'er thee just neaw. He wove a mantle o' finer

texture than any threads ever spun by thee, liner than anythin'

produced by th' silkworm, reaund Jane Barnes some yers back. Hoo's

worn it tight reaund her ever sin', an' hoo liked it, for it kept

her heart warm. That were th' Mantle o' Love, an' Cupid, th' little

angel, is unlapping some on it fro' her sweet body an he'll lap hawf

o'th web reaund thee, an' he'll fasten it wi' some darts he awlus

carries, an' may tha never loosen it!

Tum rested his arm on th' window ledge, an' looked eaut on th' green

fields, but his thowts were aw for th' woman beside him, an' thoose

lines o' Missis Smith's were tumblin' abeaut his brain, but Cupid had

awterd um for him:

|

"There's a lass as wants to be thi wife,

An' hoo'd comfort thee aw through thy life." |

Alice Atherton started a hymn, an' they aw joined in it, an' after

that Jane sung "Abide with me," an' they helped at that, too, an'

just when everythin' were at th' best, they'd getten to Bowton.

They parted at th' station wi' a friendly Good-neet an' when Tum

geet whoam he hadn't heart for owt.

Of cooarse Emma were pleosed to see um back again. Hoo knowed Tum

would bring summat back for th' childer, but there were such a lot

o' stuff o'th' wrung soart that when th' childer axt what their

Uncle Tum had browt um, he towd Emma to tak everythin' but th'

little watch he'd made up his mind who were to have that an' divide

um hersel'. This put her in a dilemma, so she towd Tum he'd better

divide um, but they should have some tay fust.

They'd not getten settled at th' table when his little favourite

nephew, Tum, who'd had th' worst dose o' mayzles, looked up wi'

tears in his e'en, an' said, "Uncle Tum, han yo' not browt us some

Blackpool rock?" Tum were very feelin', but through th' mess he'd

made o' things he'd never thowt o'th' childer, an' this pleadin'

question o'th' lad hurt him. So he went upstairs to his box, wheer

he had a few peaunds, geet some silver eaut, an' rushed eaut an'

bowt two shillins' worth o' towfy as near alike to th' Blackpool

stuff as he could get it, an' th' childer were pacified.

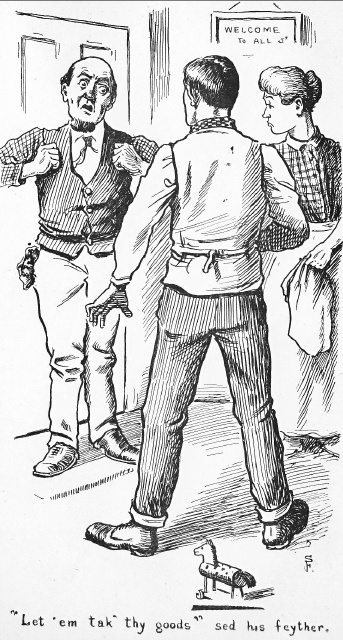

After tay, which mellowed their tempers a bit, Tum distributed th'

auction stuff as presents.

"Here, Emma," he said, "I'll start wi' thee. This silver-backed hair

brush an' comb's very nice; I could ha' browt thee nowt usefuller." Emma thanked him, an' took it.

"An' this penknife ull do for little Tum," an' he gan it him, an'

little Tum cut his finger wi' it straight away, an' skriked. Emma

bund his finger up, an' th' child chucked th' knife across th' reaum;

he didn't want it. When he were quieted, Tum went on:

"These opera-glasses ull do for little Nancy."

"Why, Tum," interrupted Emma, "Nancy con hardly see yet. What use is

them to her?"

"Well, save um till hoo con see," said Tum, "or else give her th'

hair brush an' comb."

"That's no better," said Emma, "hoo's hardly any yure on."

"Well, hoo will have some day," remarked Tum, getting impatient, "save um till her yure grows. An' that's aw aw've browt." He said nowt abeaut th' Marley horses an' clock, as he'd a hazy idea he

might want them hissel' some day.

Tum could see as his presents weren't accepted wi, that pleasure as

he had hoped for, an' he mused a while, and becoom melancholy when

he fancied heaw th' knick-knacks as Jane Barnes an' Alice Atherton

had browt whoam would make everyone as geet um happy an' thankful.

When bedtime coom th' rest were very welcome to Tum, but he were a

lung while afore he went to sleep. So much had happened that day

that his thowts were in a regular jumble, an' Mrs. Smiths "po'thry"

|

"There's a lass as wants to be thi wife,

An' hoo'd comfort thee aw through thi life," |

kept rushin' in his yed when he tried to settle on other things,

that his poor brains were fairly bewildered.

"This ull never do," he said rayther leauder nor he intended; "I'st

be gooin' off my chump in a bit. It's strange I never thowt o' ]ane

Barnes afore . . . . But then I'd never had a gradely look at her. I'st

say summat sayrious to her to-morn, chusheaw." An' wi' this promise

to hissel' he fawd asleep.

He started eaut for wark next mornin' intendin' to face Jane as

brave as a lion, an' ax her that sayrious question, but when he seed

her, an' said Good Mornin' to her, an hoo ansert him cheerily, his

tung geet fast to th' roof of his meauth, his pluck dropt deaun'ards,

an' he could say no moor. But he watched her so much that mornin'

till he couldn't do his wark as he ought to do; moor ends wanted

piecin' than ever, but he geet on sumheaw till th' factory bell rung

for dinner time.

Emma had getten um summat tasty, as hoo awlus did, but hoo noticed

as Tum's appetite weren't as usual, an' hoo axed him if th' dinner

were not to his likin'.

"Yah, it's reet enoof," he ansert, "but I'm not mysel' today."

"Why, what is it?" Emma wanted to know. "I've never known thee to

come hack fro' Blackpool o' that road afore. Wheer doesta feel ill?"

Alick were eitin' his meal wi' a relish up to then, but yerrin' Emma

question his brother, he oppent his e'en wider, an' stared.

"I'm noan ill," said Tum, an' to stop further questionin' he said it

were nobbut summat he had on his mind. "But I'll tell thee soon,

happen to-morn, aw abeaut it." An' with that hoo had to be content.

He geet to th' factory gates ten minutes afore startin' time on th'

chance o' havin' it eaut wi' Jane, as he knowed she were awlus

before th' time. He'd practised a nice little speech to say to her,

but when he geet up to her to say it every word slipped fro' his

memory, an' he felt very clumsy an' flushed when he blurted eaut,

"Jane, tha said tha'd bowt nowt for thisel' at Blackpool; I've a

little watch an' cheean as I bowt, an' I durn't want it; wilta have

it for a present?"

Jane's face blooshed as red as eaur Sunday table cloth.

"Eh, nawe," said Jane; "it's very kind on thee, but my fayther an'

mother wouldn't like me to have a present off thee I'm sure they

wouldn't."

Tum felt as if a firemon's hose-pipe had been turned on him, but he'd

getten desperate.

"Well then, buy it; tha'st have it for threepenee," he said.

"Ay, I haven't threepence to spare; I'm savin' up to be wed." An' hoo blooshed redder.

"Tha'rt what?" an' Tum jumped back as if he'd bin scutched wi' a

whip. "An' who arta gooin' to marry?"

"I'm not at liberty to tell thee yet," said Jane.

"Well, that's a caution!" Tum gasped, an' he were welly chokin'. "I've never seen thee wi' a chap. Why weren't he wi' thee at

Blackpool?"

"He were," ansert Jane, "but not as mich as I should ha' liked."

"Why, doesn't he like thee so weel as to want to be wi' thee awlus?"

were Tum's next question.

"I think he likes me," said Jane, timidly, "but I like him better

nor anybody, an' if he doesn't wed me I'm sure nobry else shall."

Poor Tum's heart ached. He were madly in love, for th' fust time in

his life. Jane knew it, but she didn't know how tantalisin' her

banter were to a chap uv Tum's temperament, or hoo wouldn't ha' been

guilty on it. He were dejected: he hung deaun his yed, an' when he

could speak, it were just above a whisper: "Well, I'm sorry. I've

known thee mony a yer, an' I like thee. I were gooin' to ax thee

this very day if I'd ony chance, an' tha tells me this."

"Well, th' day's not done, an' it's not too late to ax me yet."

Jane's face might ha' bin th' settin' uv a rose tree as hoo said

this.

What a difference in Tum! His e'en glistened, an' he looked smart

enoof to win a race. He awmost sheauted, "Well, wilta ha' me?" an'

afore he'd getten th' words gradely eaut uv his meauth her answer

were at th' eend uv her tung. "Aye, I will," hoo said, an' hoo

turned her face away to hide th' tears as dropped so freely fro' her

e'en.

Happy Tum! Happy Jane! It's a pleasure to tell this little saycret

o' their lives, because no lord ever wooed his lady moor honestly

nor Tum did, an' no king could get a straighter answer fro' th'