|

APRIL FOO-DAY.

WHEN I were a lad April Foo-day were reckoned as mich on as Tracle-cake

Day or Poncake Tuesday. We had to think on it comin' weeks afore t'

time, an' if we happened t' forget it when we wakkend on April fust

ten to one eaur faythers an' mothers ud mak a foo on us, an' then

lowf. An' we had to keep it i' mind aw day, for every lad one met

tried to trap yo', an' if yo' happened to remember it, an' he

couldn't foo yo', if he were th' bigger lad he'd cop yo' one i'th'

yer-hole.

At th' Sunday Skoo as I went to th' dobby as cleond th' skoo an'

kept us i' order wi' a cane while th' skoo oppent were named

Skinner Ham Skinner. He were a lung, thin chap, an' his wife, wot

helped him, were very fat, an' puffed a lot when hoo were warkin',

so th' lads cawd her Bacon. An' hoo soon geet to be cawd Fat Bacon.

Well, one Foo-day I'd forgetten it were Foo-day eaur Bess, my owdest

sister, says to me, "Jack, I want thee to goo to Skinner's, an' ax

Mrs. Skinner for that peaund o' fat bacon I left theer last neet. Be

sharp, neaw, for I want it to put i'th' beef-steak pie as I'm makkin'

for th' dinner. An here's a aniseed drop for thee."

Neaw, if there were owt i'th' chewin' line as I were fond on it were

beef-steak pie, an I were so pleosed to know we were havin' it for

dinner ut I galloped off, like a gobbin, thinkin' nowt wrung, an'

knockt at Skinner's dur. Mrs. Skinner ansert it. I said, "Eaur Bess

has sent me for that peaund o' fat bacon hoo left here last neet." Mrs. Skinner says, "Wait a minute," an hoo cowft, an' I seed her

face goo red. Hoo went i'th' kitchen, an' browt a papper i' one hond,

while hoo held t'other behind her. "Here theau art," hoo says, an'

pretended t' offer me th' papper, while hoo whizzed her husbond's

cane, which were in her other hond behind her, on mi' yed an'

showders till, when I think on it neaw, I con feel th' sore places

yet. "Theighur," hoo said, "that's fat bacon; goo an' tell yore Bess theau's getten it." An' when I went whoam cryin' eaur Bess an' my

fayther nobbut lowft, an' cawd me a April foo. Nobry else copt me

again that day, I con tell yo'.

It were another Foo-day after that as a lot of us lads geet nicely

tricked i' tryin' th' gam on, an Joe Baxter lost a penny through it. It were this road: There were a chap cawd Abram Watson but he were

better known as Owd Abram kept a shop i' Deansgate, where he sowd

everythin' i'th' grocery an' fizzik line. He were a little fat chap, wi' a bawd yed, an' he'd no teeth, so as when he spoke yo' had to be

very quiet, or else yo' couldn't tell what he said. He wor a

good-tempered chap, wi' a ripplin' smile awlus on his face.

Well, one o'th' lads we played wi' were cawd Tum Smith. He were a

quiet lad, an' we aw liked him, for he were awlus willin' t' run a

errand for us, or field aw day when we played cricket, an' he were innercent. On this April Foo-day, i'th' afternoon, we were gooin'

cricketin', an' Joe Baxter, th' biggest lad amung us, browt his bat

an' baw, an' Tum Smith carried th' stumps. We had to pass Owd Abrams

shop, an' Joe Baxter stopped us aw afore it, an' pood a little

bottle eaut of his pocket, an' a penny, an' said to Tum Smith,

"Here, Tum, tak' this bottle an' penny an' goo to Owd Abrams for a

pennorth o' pigeons milk. Its good for rubbin' eaur shins wi' if we

getten hit wi' th' baw." Some on us bethowt eaursels then what day

it were, an started lowfin' quietly, but little Tum poor lad, he

deed a while after on th' road to Canada looked so gawmless, an' thowt it were aw reet as Joe Baxter had sent him. When Tum geet i'th'

shop we aw flattened eaur noses agen' th' window, lowfin' like skoolads con lowf, an' Joe Baxter busted two buttons off his wescut

wi' jumpin' an' chinkin', thinkin' what foos he wur makin' o' booath

Tum an' Owd Abram. But as Tum didn't come flyin' eaut o'th shop, as

we aw expected, Joe put his face to th' window, an' his jaw dropped,

for he seed Owd Abram tak' th' bottle off Tum, an' Abram said, "Tha

wants a pennorth o' pigeons milk, doesta? Wheer's thy penny?" So Tum gan Abram th' penny, an' he off wi 'th' bottle to th' kitchen. In a bit he coom back wi' abeaut a tablespoonful o' milk i'th'

bottle, an' he said to Tum, "Its for th' choilt, I reckon. Well,

tell thi' mother to soak a piece o' flannel i'th' milk, an' let th'

choilt suck it. It'll cure it. An' if theres anny laft tha can have

a suck. An' be careful an' du.rn't spill iu, for pigeon milk's very

dear."

Yo con gowse heaw we felt when Tum coom eaut o'th' shop wi' th'

bottle, an' we could see through th' window Owd Abram doubled up

nearly havin' a fit wi' lowfin'. Joe Baxter were mad abeaut that

penny, for he hadn't another, an' when we went on Owd Abram hadn't

recovered, an' as Joe seed his merriment he sheauted, "I wish tha'd

brasted thysel', ewd mon," which I thowt were very wrung, becos Joe

were to blame. Anyheaw, it speilt th' day, for Joe were very bad

tempered, an' poor little Tum cried hard when he thowt he were th'

cause on it;.

None on us had th' pluck to try th' gam on again, an' I've never

done ony April fooin' sin.

――――♦――――

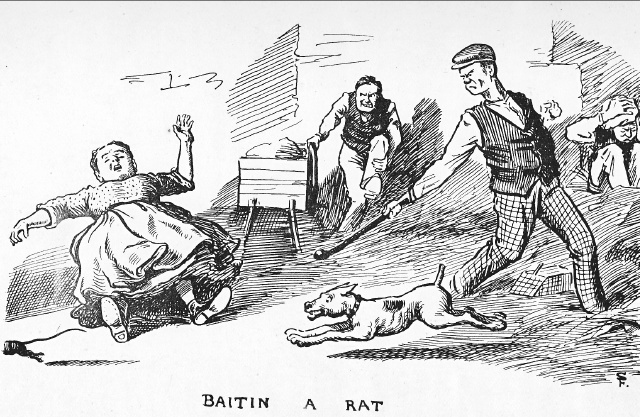

BAITIN' A RAT.

I'ST never forget it! Jim Parkinson, as kept th' hay an' straw shop,

had catcht a big rat such a whopper it were as he darn't goo

near th' trap, for it growled an' barked like a little dug. So he cawd Topper, a chap as worked for him, but Topper were feared on it,

too, then he fetched Jack Bradley, th' butcher, an' Jack browt his

fox-terrier dug. When Jack went near th' cage trap th' rat set at

him, so he stopped still for a minute. Then he towd Topper an'

Parkinson to get a stick a-piece, an' they'd tak th' trap upstairs

into th' shop, wheer there were plenty o' reaum, an' they'd bait it

wi' th' dug. Jack Bradley teed his hankicher reaund his hond, geet

howd o'th' trap, an' they went upstairs to th' shop. Then they shut th' shop dur, an' th' dur as led to th' kitchen. When they'd getten

settled, Jack Bradley said, "Neaw be sure at hit it wi' yor sticks

if it dodges th' dug . . . . Are yo ready?" They said they were, an'

Jack put his foote on th' cage, an' tilted th' lid up, but th' rat

didn't oss to come eaut. So Topper went to th' back o't' trap, an'

hit it wi' his stick. Then th' rat run eaut, an' Bradley's terrier

went for it, but it missed it. As th' rat run to'rt Parkinson he

jumped up, an' comin' deawn tumblet o'er th' dug. He were up sharp enoof, an' made at th' rat wi' his stick, but as Topper were runnin'

forrud at th' minute he geet a whack on his napper fro' Jim's stick

as knockt him mazy, an' made blood come. Then Bradley, seein' as th'

terrier had missed th' rat, which had run under some straw, made a

punce

at th' straw an' londed his clug on Jim Parkinson's shin. Jim yelled eaut, an' dropt his stick for t' rub his leg. Missis Parkinson, yerrin th' row an' scuffle i'th' shop, coom hurryin eaut o'th'

kitchen, an' as hoo oppent th' dur th' rat, seein' a chance to

escape, coom fro' under th' straw an' run past her. Hoo seed it, set

up a skrike as would ha' freetend a thunder clap, an' fawd deaun in

a fit. Then th' dug, seein th' rat gooin, barked an' were after it. Jack Bradley were so mad at th' terrier missin th' rat, that he hit

it on th' yed wi' th' stick as Jim Parkinson had dropt. There were

such a yelpin as raised th' nayburhood, an' a creawd collected

reaund th' shop door in no time. Yerrin th' neise inside th' shop

they thowt murder were bein' done, an' sombry fotcht a bobby. When

he coom he banged at th' dur, an' Jack Bradley oppent it. Th' bobby

thowt he'd getten a good cop (though he wur a bit narvous) when he

seed Mrs. Parkinson lyin' on th' flure in a fit, an' Topper sittin'

on a bundle uv hay, moanin' hard, an' howdin' his hankicher to his

yed, which were bleeding fast; an' then looked at Jim Parkinson,

who were groanin an' rubbin' his leg.

"Whooa's done aw this?" he axt Jack Bradley, who were th' only one

as wern't hurt.

Jack Bradley were so bewildered he couldn't speik.

"If tha's nowt to say I'st lock thee up, an' charge thee wi'

attempted murder."

He collared Jack Bradley, an' were makin' off wi' him, when Jim

Parkinson, seein' as things were gettin sayrious, pood hissel'

together, an' towd th' bobby as Jack had done nowt wrung. "We'n

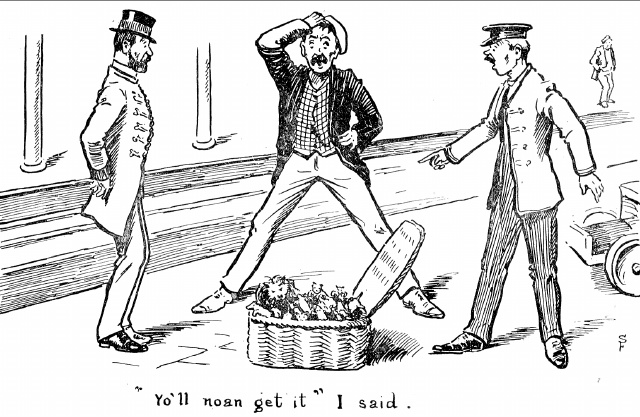

nobbut bin baitin' a rat," he said.

Th' bobby, yerrin' Missis Parkinson groanin', just as if she were at th' last gasp, went to her, lifted her up, an' when he geet her

reaund, Topper had to be looked after, for his yed were bleeding,

an' he were skrikin' like a hooter at a fair. Then th' bobby turned

to Jim Parkinson, who were still rubbin' his leg an' pooin' afeaw

face. "I think," said th' bobby, an' he looked disgusted, "th' best

thing I con do for thee is to send for th' ambulance, an' ha' thi

leg tan off."

"Durn't bother, mester," said Parkinson, "I'st be reet in a bit. Thank you, aw't same," an' he limped ith' kitchen. Th' bobby went to

th' shop dur to send th' creawd away, an' then bethowt o' summat. He

turned back, an' said to Jack Bradley, "Wheer's th' rat yo'n bin

batin?" Jack looked reaund, an' said, surprised-like, "Why, it mun

ha' getten away!"

Th' bobby looked as if he didn't believe it, but he went off. When

he'd getten a bit deawn th' road he stopped still, pood his helmet

off, an' scrat his yed. He were thinkin'. In a bit he recollected,

an' he said to hissel, "By gow! it is; I've bin had. Yesterday were

t' thirty-fust o' March."

He were mad then, an' he set off back as fast as his feet would let

him goo. When he geet to Parkinson's shop he shuved th' dur open,

an' sheauted, "This is a trick. Yo'd best be careful; I'm noan to

be had twice."

――――♦――――

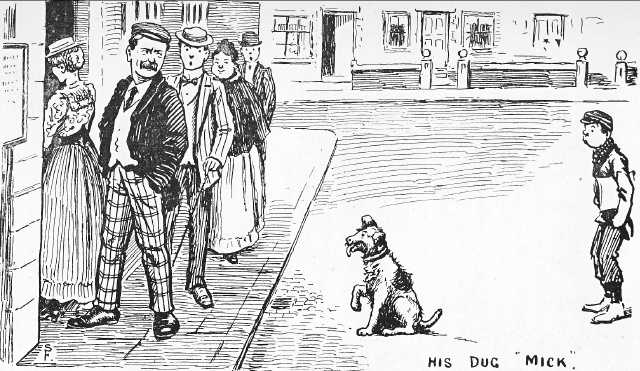

HIS DUG "MICK."

IF annybody

thinks I'm fond o' drink it's a mistake for I'm not. Mony a

time when I've bin beaut brass, or bin' savin' up for my holidays,

I've never touched ale for wicks at a time, an' I could do it again.

But I do go i'th' Miller's Arms i' Blackpool sometimes, for I yer

mony a quip theer ut's woth tellin'.

Me an' Joe Short were theer t'other neet. Yo' seen we'n

a pictur club Joe's secretary an' I'm treasurer an' we'd bin

canvassin' for customers, so we thowt we'd have a pint apiece after

th' neet's wark.

There were nobbut one felly i'th' room when we went in, an',

by gum, he were a quare-lookin' customer. He were a little

chap, wi' ferrety een, an' his body were on th' twitch aw th' time

we were in, as if he'd summat on his mind.

In a bit two farmers wot lived at Marton coom in, and they'd

a collie dug wi' um. They'd bin takkin' cattle to Poulton, an

wur on th' th' road whoam again. After suppin' an' warmin'

theirsels, th' chap as owned th' dug begun o' strokin' it an tawkin'

to it, an it looked as if it knowed every word as were said to it.

"Thats a good dug yo'n getten, mester," I said.

"It is that," said he; "it con do owt but talk. Hast' a

penny in thi pocket?" he axt.

I towd him I had.

"Well," said he, "put it on its nose, an' see what it'll do

wi' it."

So I chanced a penny, put it on its nose, when th' dug

balanced it, chucked it up i'th' air, an' then copt it in its meawtb.

Then it walked eaut o'th' room, an' in a bit it coom back wi' a

papper bag in its meawth. It put it between its paws on th'

flure, tore th' bag oppen, an' theer it had bowt three sugar-covered

biscuits wi' th' penny, an' begun eitin' 'um.

"Well, that is clever," said Joe Short; "but it's done it

afore."

"Aye, it has," said th' farmer, "th' shopkeepers abeaut here

aw know eaur Dan." An' he patted it again.

Then th' little chap wit' ferrety een chipped in. His

body had bin twitchin' a lung while, an' his little een twinkled an'

twitched like his body.

"I'd a clever dug once," he said, "an' it were a rip."

"Well, tell us abeaut it," said Dan's mester.

"Well, I am doin'. I fun it wanderin' abeaut th' street

when it were a whelp, ragged an' rough-haired, wi' only hawf a tail.

It were a Irish terrier. When I took it whoam th' wife an'

eaur Selina (she's eaur only choilt) took pity on th' poor thing,

an' they geet to like it. But I mony a time wished I'd never

seen it, for it caused me mony a freet, an' made me so narvous I'st

never get o'er it. It were awlus feightin', an I were never

eaut o' trouble. It would tackle any dug it met, an' after

sendin' th' licked dug yelpin' deaun th' street it would come an'

sit on its haunches at my feet, an' wi' one yer cocked up an' its

yed on one side, would ax me in its way if it hadn't done that very

weel.

"I cawd it Mick. One day, when I thowt it were abeaut

six months owd, I took it wi' me to th' Post Office i' Coronation

Street to get a dug licence. Th' office were crowded. I

wur waitin' my turn to get in just behind a woman as wanted a

haup'ny stamp when there were such a skrike as made aw th' postmen

an' clerks stop sarvin', an everybody looked to see what were up.

It were Mick. This woman had her little wench wi' her, an' I

reckon Mick couldn't understood why I should wait for her to be

sarved afore me, so it had getten howd o'th' wench's frock an were

draggin' her eaut o'th' road. Then her mother throwed her arms

reaund her, an skriked "Murder," "My choilt," an' such like. I

rushed at Mick, an' punct him eaut o'th' door into th' middle o'th'

street, yelpin' an' yelpin'. Then aw wur quiet for a bit; I

geet my licence, an' wur turnin' reaund for t' come eaut, when,

behowd, Mick were set down wi' one yer cocked up lookin' so fause I

couldn't find i' my heart to hit him again.

"That were a good start o'th' trouble I had wi' him.

"I daresay yo'n seen on a summers day when th' visitors bring

their dugs to Blackpool a lot o'th' dugs ull get to th' wayter's

edge an' dash in time after time for anybody as'll throw sticks or

stones for um to swim for. Well, Mick liked that job very weel.

One day I took him to th' North Shore wheer th' bathin' vans are.

Yo know there's mixed bathin' theer. Well, Mick geet tired o'

swimmin' after sticks, so he gallivanted abeaut th' bathin' vans,

an' popped in one of um, while th' ladies as hired it were in th'

wayter. He coom eaut wi' a red flannel petticoat in his meawth,

dragged it alung th' weet sond, an' laid it at my feet. I were

so shawmed I hardly knowed wheer to look, but I said summat as I

durnt want to say again, an I gan him a punce, an' sent him off back

wi' it. He took it back reet enuff, as I thowt, but in a bit I

yerd a scream, an' seed two lasses rushin' eaut of a bathin' van,

an' tumble i'th' say. It were Mick's wark again. He'd

tan th' flannel petticoat back, as I said, but instead o' puttin' it

wheer he geet it fro', had dropped it on th' flure of a bathin' van

belungin' to two young men. When th' lasses coom back to dress

they hadn't noticed th' number on their vans, an' seein' th' red

petticoat on th' flure had walked in. They picked th'

petticoat up, an' begun o' pikin', bewildered like, amung some

wescuts an' treasure for their other garments, when th' young men

coom eaut o'th' wayter, an' walked in th' van, which were that as

they'd hired. Th' ladies went i' hysterics, an' could be yerd

as far as th' South Shore, dashed into th' wayter, an' were welly

dreawned i' their freet.

"I didn't stop to yer any moor, but skulked off wi' Mick at

my heels, one of his ears cocked up, as fast as I could, an' when I

geet near whoam I gan him a punce as I thowt he wouldn't forget.

Then I yerd a leaud knock at eaur bedroom winder, an' a smash o'

glass followed. I looked up, an' seed th' wife. Mad wi'

rage when hoo seed me punce Mick, hood hit th' window too hard at

me, an' it had brokken. That window cost me five bob, besides

a row wi' th' wife, an' hoo didn't spake to me for a month after."

"He were a smart dug," said th' farmer as owned Dan.

"He were," said Ferret Een. "Too smart bi th' hauve,

for his smartness were t' deeath on him."

"Heaw were that?" I axt.

"Well, yo seen, one day I had him eaut wi' me, an' hed had

tothri feights wi' dugs bigger nor hissel', an he'd cocked one yer

up after every victory to show me he'd won, when, just as we were

opposite eaur door comin' whoam, a motor-car coom drivin' up at

abeaut forty mile an heaur. Mick seemed to know as th' shuvver

(chauffeur) were scorchin' an' he went for th' car. His barkin'

did no good, so he jumped up at th' glass screen at th' front, but

he wuru't sharp enoof that time, for when he dropt th' motorcar run

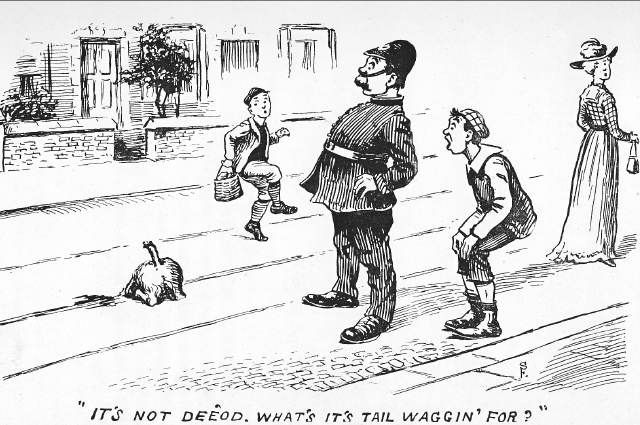

o'er him, an' cut him in two."

"Poor Mick," said Dan's mester, "that were a sad job."

"It were," said Ferret Een. "Well, I picked him up

afore anybody had time to make remarks abeaut his folly, an' th wife

an' eaur Selina bust eaut cryin' as hard as they could; I'd a bad

twinge or two mysel', an' could feel a hot drop or two on my cheeks

as I took him i'th' back garden. I started diggin' a grave for

him, an' I'd made it pratty deep, when eaur Selina sheauted eaut, "Fayther,

there's a policemen wants you."

"Hello," I thowt, "what's up neaw," as I put th' spade deawn

an went to th' dur.

"Is that yore dug lyin on th' tramway lines?" says he.

"Nawe," I says, "my dug's just bin run o'er by a motor-car,

an' I browt it in to bury it. I'm diggin' his grave i'th'

garden neaw."

"But theau's not getten th' dug," says he; "it's in th'

street! Come an' look."

I went, an' sure enoof I'd getten only hauve o' Mick, for

there were th' back eend on him lyin' across th' tram lines, an' his

tail were up waggin' like a clock pendylum."

"Why, this is funny," said th' policeman. "He's not

deeod, an still there's only hauf a dug. What's his tail

waggin' for?"

"It's just like Mick," I said; "he never were licked in his

life, an' he wurn't be licked neaw. He's waggin' his tail, I

reckon, becos he's busted a tyre o'th' motorcar as run o'er him."

We aw coom eaut o'th' room at that, except Ferret Een, an' as

he geet to th' dur, th' farmer as owned th' sheep dug turned reaund,

an' said:

"Neaw, as I look at thee, I think I know yore family."

"Dun yo," said Ferret Een, quite gawmless.

"Aye, I do," said th' farmer. "Hadn't thi' gronfayther

a big family? Tha's a lot o' relations?"

"I have," said Ferret Een.

"I thowt so," said th' farmer. "I've read abeaut thi

gronfayther. Worn't his fust name Ananias?"

There were a lowf fro' th' lobby, an' Ferret Een said nowt,

though some colour coom in his face, as th' farmer bid him good-neet.

――――♦――――

ANOTHER DUG TALE.

TWO-OR-THRI' wick after

meeting Ferret Een we'd bin canvassin' for th' picter club again,

an' we were tired, so we cawd i'th' Miller's just to have a rest and

one pint apiece afore gooin' whoam. Thoos two farmers fro'

Merton were theer again, an' they had that collie dug, Dan, wi' em.

After we'd chatted awhile, th' talk turned to dugs. Joe Short

were larkin' wi' Dan, which remembered him, an' th' farmer as owned

it said to Joe, "Tha seems fond o' dugs; dos't understond 'em?"

"Well," said Joe, "I uset' fancy um one time, an' I've reart

a lot, but they were a little breed."

"Oy, aye!" says th' farmer, "I dare say tha con tell a tale

or two abeaut um if tha likes."

"I happen con," said Joe, "but if I towd yo summat as were

true, yo'd happen say as I were a relation o' Ferret Een."

"Not us," said th' farmer, "we durnt think tha could tell

lies like him. But tell us summat worth yerrin' when tha

starts."

"Aw reet," said Joe, an' he brasted off wi' this tale.

"Yo may believe it if yo like."

"It's some yers sin this happened. In thoos days I used

to breed breawn Poms, an' I could get good prices for um too, for

they were like black strawberry then, very scarce an' dear. So

one time I browt a whelp, six wick owd, fro' Bowton to Blackpool,

an' th' chap as wanted it arranged for t' meet me in this very

heause to buy it. I'd never bin in th' place afore. When

I geet here th' chap hadn't come to meet me, an' he never turned up

aw day. Th' lonlord took a fancy to th' pup, an' he'd ha' bowt

it but his wife had gone to her mother's for a wick. So I left

my Bowton address, an' he said he'd write me for one, if hoo liked.

Well, I had to tak th' puppy whoam again. I'd browt it in my

pocket, but I were soft enoof to carry it under my arm when I went

to th' station for whoam. Th' porter at th' barrier axed me

for my ticket, an' I showed it to him. "But wheer's th' ticket

for th' dug?" he axt. "What dug?" says I. "I have no

dug."

"What's that under thy arm, then? It's not a cat, or a

squirrel; perhaps it's a monkey" an' he lifted my cooat away to

look. "Neaw, " he says, "it's a dug."

"It's noan a dug," I says, "it's nobbut a whelp."

"Well, I'st want a ticket for it," he said.

"I'st get no ticket for it," I ansert. "Th' Goverment

says its noan a dug till its six months owd, an' then I'st ha' to

pay th' tax for it."

"Th' Goverment's nowt to do wi' it," th' porter said. "Th'

railway company's mester here, an' they say I mun have a ticket for

every dug as passes through this gate. But th' station-mester's

theer see what he says.

So I went to th' station-mester an axt him. "Tha'll

have to get a ticket for it," says he.

"But it's nobbut six-wick owd," I said.

"It doesn't matter if it's nobbut six minutes owd, tha'll

have to get a ticket. . . . An' be sharp," he says, an' he stamped

his foote, "for I've kept th' train waitin' six minutes for thee."

That were his joke. But I had to get a ticket, an' it

cost a shillin'. I were mad, yo may be sure, an' I grumbled a

lot in th' carriage. A lady felt so sorry for me she said

she'd pay for th' dug, an' hoo pood her purse eaut.

"Thank yo, missis," I said. "I shall be much obliged if

yo will."

So hoo offered me a shillin'. "But I'st want th' dug,"

hoo said.

Well, I thowt that banged Banniger. I'll bet that woman

were a regular moocher at th' bargain ceaunters i'th' drapers'

shops.

"Nay, missis," I says, "this whelp's price is two peaund, an'

I railly couldn't let yo have it for a shillin'. But I'm much

obliged for yo'r offer." Hoo bluushed, an th' passengers lowft.

But I never could get that shillinl eaut o' my crawl, an' one

day a letter coom fro' th' lonlord here (as wor then; his name were

Jones), sayin' he'd be glad to have a pup o' that breed as I'd shown

him. Well, I had noan, but I'd getten th' mother on um, an'

hoo were gooin to have another litter. So, as I were tiret o'

breedin', I wrote an' offered him th' mother as hoo were for six

peaund. "Aw reet," he ansert, "bring her." So I put her

in a basket, fastened th' lid deawn, geet a shillin' ticket for her,

an' gan th' basket to th' guard. He oppent th' basket to see

as she were aw reet. When we geet to Blackpool I went to th'

luggage van for th' basket an' th' guard said, as he honded th'

basket eaut, "Theres a merricle here. I thowt tha said there

were only one dug, but I've yerd a lot o' yelpin'. Here, let's

look again." An' he oppent th' basket. "Why, there's

nine whelps an th' mother! I'st want a ticket apiece for this

lot."

"Well, tha'll noan ger it," I said. "There were only

one dug when I started, an here's th' ticket for that."

"Well, there's moor nor one neaw," he says, "an' I want a

ticket apiece."

I were gettin' a bit mad by this, an I ansert, "I've only one

ticket, an I'st pay no moor."

"Yah tha will," he said, as he cawd th' station mester, wot

knowed. He oppent th' basket lid, an' theer were nine o'th'

bonniest brown poms yo ever seed.

"That's getten one ticket, tha says, an' there's ten dugs.

I want nine shillin' moor fro' thee," an' he grinned so fat till his

silk hat lifted up.

My temper were gradely up neaw, as th' litter were welly

stewed, an' th' mother wanted feedin. "Yo'll noan get it," I

said, "there were only one dug when I started, but th' chep engine

has shook th' train so much that th' pups ha' coom afore their time.

I'st want compensation if owt happens."

"Compensation be hanged!" he says, "tha'll ha' to pay for um,

or else I'st keep aw th' lot."

"Aw reet; keep um," I says, an' I wrote Mester Jones's

address on a bit o' papper, an' gan it him. "These dugs belung

to th' lonlord o'th' Millers Arms."

I said, " an' he'll want ten dugs off yo, so if yo wurn't let

me tak um, an' ony on um dees, we'll ruin yore little railway

company."

"Aw reet," he ansert; "pay up an' tak um; if tha doesnt I'st

keep um."

So I coom to th' Miller's Arms, an' towd Mester Jones, an'

afore I'd finished my tale a porter coom in carryin' th' basket on

his showders, an' said th' station mester had sent th' dugs, wi' his

compliments, an' thowt he were reet in demandin' th' fare for um,

but had fun' he were wrung, and would Mester Jones o'erlook th'

mistake.

"So Mester Jones looked in th' basket, an' findin' th' dugs

aw reet, he said he'd o'erlook it this time, an' he stood th' porter

a pint for fotchin' um. But I never geet my shillin' back."

"That's very good," said th' farmer as owned Dan, "an' it

shows heaw railway companies ull do you if yo durnt watch 'em."

――――♦――――

GINGER'S CUSTOMER.

SHE were nobbut a

mite abeaut nine yer owd but she could cleon a pair o' dursteps

wi' ony woman, an' as for nussin' a choilt, well, th' little darlins

seemed to come i'th' world o' purpose to find her a job, for hoo'd

very oft one in her arms. She'd two owder brothers, an' hoo

brooshed their shoon o' cooartin' neets, an' hoo were th' one as her

mother could trust to send to Owd Ginger's shop for oather tape,

shoe tees, or groceries. So, aw th' family cawd on Little Emma

for onythin' as wantid dooin', an' hoo were th' drudge for th' lot.

Owd Ginger were a Scotchman, an' his name were Mac Summat,

but Bowton folk couldn't get their tungs reaund th' Summat, so they

cawd him Ginger, because his yure were red. He kept a shop,

an' sowd everythin', like th' Co-op. When Ginger fust coom

i'th' nayburhood he talked Scotch, an' nobry could understond him

for a while, but he soon geet into th' Lancashire twang, though he

sometimes dropt some Scotch in it. (That's nobbut a joke.)

Heawsumever, little Emma were a favourite wi' Ginger; he

awlus breetened up a lot when hoo went to his shop, an' she very oft

coom owt wi' a cake or some towfy as Ginger had trated her to; so

Little Emma were fond o' Ginger. (That's another joke.)

But Little Emma crabbed him onct. He thowt, for a bit,

hoo were playin' a trick on him, but th' choilt did it quite

innercent. It were like this:

One day Little Emma's mother sent her to Ginger's shop.

"Tak th' traycle jug, Emma," hoo said, "an' fotch two peaund o'

black traycle. Here's sixpence, an' tha' wants tuppence back.

I'll put th' sixpence i'th' jug, so as tha'll not loase it."

Then Emma started off, an' on th' road hoo met Charley Stone,

a little nipper she played wi' when she'd th' chance, an' were very

fond on. Charley started larkin' wi' her, as lads generally do

wi' wenches as soon as they con walk beaut tumblin', an' yerrin' th'

sixpence rattle i'th' traycle jug, he tried to grab it. Little

Emma dodged him, took th' sixpence eaut o'th' jug, an' put it in her

meawth. Then hoo hooked it off to Ginger's shop.

"Well, little Starleet," said Ginger, "what does tha want

this mornin'?"

"Two peaund o' black traycle," said Little Emma, "an'

tuppence back."

"Aye, an' tha'st have it," said Ginger, an' he reicht th' big

traycle can deawn, put Little Emma's jug on th' scales, an' teemed

th' syrup in till th' jug bumped deawn.

"Here tha art, little cherub," said Ginger, "an' tha wants

tuppence back, does ta? Well, if tha gies me sixpence tha'st

ha' tuppence."

"Yo'n getten it!" said Little Emma, who'd forgotten her

larkin wi' Charley Stone. "Didn't yo' tak it fro th' bottom

o'th' jug?"

"Wot?" he skriked, leauder nor a set o' bagpipes, "at bottom

o'th' jug! Why didn't tha say so afore? Tha careless

wench! Seethi' wot trouble tha's gan me!" Then he geet a

little seive, an' temd th' traycle through it back again into th'

big can, but he couldn't find th' sixpence.

"Tha's not browt th' money, tha' little imp," said Ginger,

his face gettin' red, "an' tha wants th' traycle an' tuppence back

for nowt. Ger off wi' thee. Hoots, toot."

Little Emma were in a terrible state while Ginger were

carryin' on this road, an' while hoo were cryin' hoo oppent her

meawth an' hoo felt th' sixpence slip fro' under her tung.

"Oh, I'd forgetten, Ginger," hoo cried, "th' sixpence is in my

meawth." An' hoo put her finger in, but, as her hond were

tremblin', she lost her grab, an' it slipped deawn her throat.

"I've swallowed it," said th' choilt, th' tears runnin' off

her cheeks as if they were macintosh. "Oh, Ginger, what mun I

do?"

Ginger's heart softened when hee seed her so much troubled,

an' he said: "Well, I cornt empty thee th' same as I emptied th'

traycle jug, but, as I believe thee, I'll fill it again. Tak

it, an' tell thi mother to send th' fourpence th' next time tha

comes."

I never yerd whether Ginger geet his fourpence, but I think

Little Emma lost that sixpence for ever.

――――♦――――

SARS-PRILLA.

GENERALLY speikin,

I'm a greit believer i' wimmin. If ever a chap goes wrung, an'

loases his balance, if there's a chance ov his ever gettin' reet

again it's oather his mother or his wife as con do th' trick; his

wife for cheice.

There's nowt I like to see as weel as a warkin' chap smookin'

his pipe after his tay an' a day's hard wark, sittin' by th'

fireside wi' his wife an' childer gathered reaund him, listenin' to

a tale he's tellin', while th' fire sparkles breet, th' fireirons

are like lookin' glasses, an' th' harthstone so cleon it wud show a

cockroach up. Yo may tell then as that chap's getten a wife

worth havin', an' such women con generally keep a chap straight,

when hoo goes th' reet road abeaut it. I've a little tale here

ov a chap as wanted some straitenin', but he'd a wife 'as made no

booans of a job o' that soart, when hoo made her mind up.

Th' chap's name were Dick Hampson, an' he were a spinner.

He wor a good worker, an' yo'd caw him him level-yedded, but every

neaw an' again he'd goo on th' spree for a month at a time, an' then

make a reglar soss of hissel. His wife, Margit, were one o'th'

best heausewives I've ever seen, an' her two childer were noticet as

th' prattiest an' cleonest i'th' naburhood. But Dick's sprees

were Margit's ghost, an' I used to wonder, when I seed wrinkles o'

care on her face when Dick were drinkin' heawever hoo'd such i

patience wi' him. But hoo had, an' she didn't blackguard him

at such times. Nowt o'th' soart; she'd coax him, an' when he

were gettin' reaund an' his lips were parched an' his throat dry

hoo'd do th' Lazarus business, an' fotch him a pint o' ale to

relieve his sufferin'. While he were suppin' it hoo'd talk to

him quietly an' sayriously abeaut dammin' his sowl an' his body till

Dick would be ashamed ov hissel', an' while th' misery were on he'd

promise when he get reaund never to taste again.

Well, th' last spree he had were woss than ever. He

were off wark lunger, an' he supped moor ale, but summat happened as

made him teetotal, though it welly kilt him.

Margit had coddled an' nussed him moor like a mother than a

wife, an' as he geet a bit better, after givin' her a lot o'

trouble, hoo made bowd to give him a talkin' to just at th' time

when there were a gradely thirst on him. He axt her just to

fotch him one moor pint. "It'll be th' last," he said, "for

I've made up my mind when I get better never to touch, taste, or

hondle any moor."

"Dick," said Margit, "tha's said that so oft that I'm hard o'

belief. But I'd give owt as I have if I were sure tha'd keep

that promise."

"Well," ansert Dick, "if theau'll fotch me a sup o' summat

just neaw tha may believe me this time, for my throat's fairly

brunnin', an' my yed's comin' off th' top."

Margit railly felt sorry for him, he were so bad. I'll

fotch thee summat, Dick," hoo said, "but wilta have a pint o' yarb

beer instead uv ale? It'll slake thi thirst just as weel, and

do thi yed good."

"Aye," ansert Dick; "I'll have owt as is weet. Fot me

some sars-prilla."

So Margit, pleosed as he'd have it, put her shawl on an' went

to Bill Clegg's shop for a pint o' sars-prilla. When hoo geet

theer Bill happened to be eaut, au' his niece, Susannah, coom to

sarve her. Margit towd her what hoo wanted, but th' wench

didn't know wheer it were. So hoo went to th' bottom o'th'

stairs, an' sheauted to Bill's wife, who were cleonin' th' rooms,

"Aunt Sarah, wheer dun yo keep th' ears-prilla? Dick Hampson

wife wants a pint."

"Why," ansert her aunt, "there's two full bottles i'th' front

o'th' bottom shelf, filled wi' black stuff. It's th' bottle

nearest to thee."

So hoo geet th' bottle nearest to her, an' temd a pint into

Margit's jug, and drawed tuppence for it.

"Margit took it whoam, an' gan it to Dick, who put th' jug to

his lips, an' drained every drop. He pood his face when it

were gooin' deawn, but he were so thirsty he'd ha' supped owt.

In a bit he begun o' feelin' queer, an' his stomach were unsettlin'.

He put up wi' it for a while, not carin' to let Margit see as owt

ailed him. He geet so bad in a bit, an' were vomitin' so much,

that Margit were freetend, so hoo rushed off to Bill Clegg's for

summat to stop th' gripin' pain an' sickness. Hoo met Missis

Clegg on th' road. She were hurryin' to Margit's to tell her

as heaw Susannah had used th' wrung bottle, an' instead of a pint o'

sars-prilla she'd emptied hauf-a-dozen black draughts in Margaret's

jug.

Margit were in a terrible way at yerrin' this. "Oh

dear," hoo cried, "whatever mun I do; it'll kill him. Let's

goo an' see if yore Bill cannot give him summat for it;" an hoo

started off, pooin' Margit wi' her.

"Nawe, tha' munnot goo, Margit," said Missis Clegg, howdin'

back. "Eaur Bill doesn't know ov owt as'll do him good, an' he

doesn't know abeaut th' mistake; if he did, he'd carry on, for eaur

Susannah gan thee six black draughts, which were a shillin', an' tha

only paid tuppence. I'll tell thee what to do go to Doctor

Roberts, an' tell him abeaut it. He'll mak him aw reet, an'

durnt trouble, black draughts aren't peison. I'll pay th'

doctor, if tha'll promise not to tell eaur Bill abeaut it.

He'd carry on so."

Margit weren't in a humour for argifyin, so hoo turned off to

Doctor Roberts's surgery.

Doctor Roberts were th' medical mon for everybody i'th'

nayburhood. He were very kind to th' poor, an' just th' reet

mon to have aside on yo when yo were ill, so one may say he were

everybody's friend. But he were a bit ov a wag, for aw that,

an' liked a joke, as yo shall see.

Margit had lost a deol o' wynt by th' time hoo geet to th'

surgery, but as luck ud have it, th' doctor were in. When

Margit had towd him th' tale between sobs an' shortness o' breath,

th' owd doctor smiled, but he tried to comfort her. "There's

no danger," he said, "so I'll mix him a bottle that'll soon put him

to rights. Let's see, I've met him several times lately, an'

judgin' by the aimlessness of his gait, his legs seemed unable to

decide which way to carry him; by which I concluded that he was

having another drinkin' bout. If so, how long has he been

fuddlin' this time?"

Margit didn't expect this, but hoo towd him th' truth, an'

hoo could see as th' doctor were chucklin' to hissel. But hoo

were tan aback when Doctor Roberts axt her if hoo'd like him cured

fro' drinkin'.

"I should that," said Margit, "but yo'll not manage that; for

I've tried aw I know. Besides, but for a spree neaw an' again,

he's a good husbont, an' I wouldn't have yo' hurt him."

"There's no danger, as I told you," said th' doctor, "but

fuddlin's a nervous disorder, an' if he's as bad as you represent

now, I could so act on his system with make-believe that a revulsion

in his appetite for intoxicants would ensue, and he would never

taste again."

Margit didn't understand everythin' what th' doctor said, but

hoo knowed what he meant, an hoo agreed to what he said, an' even

promised to help him.

"Well, then," said th' doctor, "take this bottle, give him a

dose, an' I'll call to see him in half-an-hour."

Margit rushed off whoam, an' hoo fun their Dick aw uv a lump

on th' floor i' awful agony. His een were shut, his face blue,

an' th' sweat were rowlin' off him as if he were in a Turkish bath.

Wit' th' help o' some nayburs hoo managed to get him upstairs, an'

bi th' time they'd getten him i' bed Doctor Roberts coom. He

walked to th' bed wheer Dick lay groanin' after th' shakin he'd had

i' bein' pood abeaut, an' oppenin' one uv Dick's een wi' his finger,

said quite loud, "It's a bad case of alcoholic poisoning."

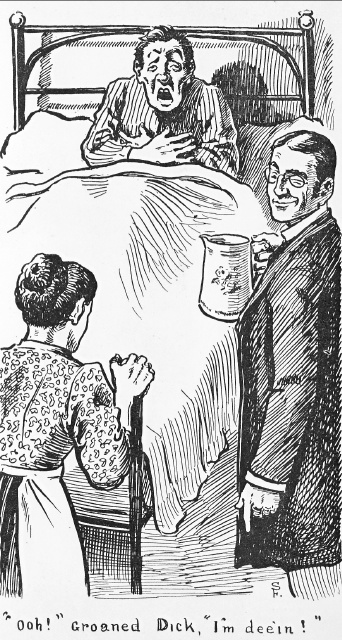

"Oh-o-o-o!" groaned Dick, as if he were deein'.

"Give me some mustard an' a jug of hot water," said th'

doctor. "He must have a strong emetic at once."

Dick groaned again while Margit geet th' hot wayter an'

mustard. Th' doctor pretended to mix it, an' he put th' jug to

Dick's lips. After a lot o' persuadin' Dick oppent his meawth,

an' th' doctor temd th' wayter deawn him faster nor he could sup it.

Dick were sick in a minute, an' th' bedclooas geet spotted

aboon a bit.

"Oh-o-o my!" groaned Dick, "I'm deein'."

"Oh, no, my man, you'll be better in a while," said th'

doctor. Then he turned to Margit, an' said, leaud enoof for

Dick to yer what he said, "Don't let him move for three days, and

don't allow anyone to talk to him. I'll call tomorrow for a

thorough examination. Meantime, if he becomes worse send word,

and I'll come at once."

Th' doctor went downstairs an' Margit followed. "Don't

be alarmed, Mrs. Hampson," said th' doctor, lowfin'; "we'll cure

him, and if he has anymore sprees I shall be a false prophet.

Give him warm water to drink every two hours, with a very little

mustard in it. This will remind him that he's poorly.

To-morrow morning you may give him a cup of beef tea."

"Aw reet, doctor; but if he gets yezzier an' wants some ale

mun he have it?"

"What!" said th' doctor, "have you already forgetten your

promise to help me? No; he mustn't have any ale or anything

like it. He won't ask for it or want it again of that I'm

sure so don't show any false sympathy by tempting him."

Then th' doctor went, an' Margit seet off upstairs to her

husbont. Hoo fun th' bed empty, an' comin' deawn to look for

him hoo met him crawlin' in eaut o' th' back dur. "Eh, my poor

lad," hoo said, "tha shouldn't ha' geet eaut o' bed. Th'

doctor says tha mun stop in for three days, an be very quiet."

"Oh dear!" wailed Dick, "I cornt stop i' bed three minutes,

let alone three days. I'm sure I'm done for."

He looked hawf deeod, an' laid his yed on her showder as hoo

helped him back. "Neaw, lie thee still, that's a good lad, an'

I'lI fotch th' emmetic up."

"Oh-o-o-o!" groaned Dick, "nawe, durnt. I corn't stond

any moor on um."

Th' very seaund o'th' word acted like magic on Dick, for he

rowled off th' bed an' scuttered deawn th' stairs an' into th' yard

faster nor a deein' chap would be expected to goo. When he

coom i'th' heause again Margit had to help him upstairs, for his

legs doubled up under him. "Oh-o-o my!" he groaned, when hoo

were ill-in him up i' bed, "if th' Lord ull forgi' me this time I'st

never touch a drop o' ale again as lung as I live. Oh, dear;

oh, dear." (Yawp!) Then he were sick again.

Margit were railly touched at seet uv her husbont when hood

getten him composed. Hoo could see his flesh were gooin', an'

his thermometer were risin'. Hoo lunged for th' next day, an'

th' doctor. An' they coom.

Doctor Roberts were theer very early on, but afore he went

upstairs he reminded Margit uv her promise to help him to cure Dick

uv his spreein'.

"Don't be afraid," said th' doctor, "of what I say during the

examination: it may be all wrong, but act as if I were in earnest,

an' when the examinations over follow me downstairs, and I'll tell

you what to do."

So th' doctor went to examine Dick, who were fast asleep

after a weary neet. He pood Dick's shirt front oppen, put th'

trumpet o'er his heart, an' put his yer to it. This wakkend

Dick. After Iistenin' a bit, th' doctor said, "Just as I

thought. Heart terribly weak, probably diseased; clearly a

case of alcohol poisoning." Then he axt Dick if he'd a pain in

his back. "Aye," groaned Dick, "but I've one a deol woss i' my

stummack."

"I thought so," said th' doctor, "kidneys worse than heart.

Open your eyes."

Dick groaned, an oppent his een. "Um! Yes!" said

th' doctor. "He's highly feverish, Mrs. Hampson. I'm

afraid we shall have a job to pull him through. Give him half

a pound of castor oil with four ounces of turkey rhubarb in it;

perhaps that will clear his stomach."

"Whow-ow!" sheauted Dick; "for God's sake, doctor, durnt

order that. My stummuck's cleared eaut enoof, I'm sure," an'

he dropped back, done up.

"Yes, but you want to get better for the sake of your wife

and children, don't you?"

"Aye, I do," groaned Dick; "but durnt gi' me any castor oil

or rhubarb if yo con help it."

"Well, I'll see," said th' doctor. "But if we get you

round from this I hope it will be a lesson for you, for you've been

as near death as I care to see a young man."

"It will, doctor, it will. If I get better this time

I'll never touch drink again."

Margit followed th' doctor deawnstairs, an' he'd a grin on

his face when he towd her as Dick were gettin' on aw reet, an' hoo

could give him some beef tay. But hoo mut keep him in bed a

day or two.

Margit did as th' doctor towd her, an' Dick geet reaund, but

when he come deawnstairs he weighed two score less nor he did when

he fust went up.

I've never yerd as Dick Hampson had a spree sin then, but I

did yer as he'd getten to be th' manager o' th' mill, an' I do know

as if yo'l1 go th' chapel at Lone Ends uv a Sunday yo'll see see a

chap, wi' a grey nob neaw, leodin' th' quire. They caw him

Mester Hampson, but his front name's Dick.

――――♦――――

|

ON A MOTHER'S BIRTHDAY.

(Written on a card, of my daughters'

request, on the eve of

their mother's birthday.)

MAY

Old Time pass blindly,

When he's dealing out care;

And. Nature treat kindly

A fond mother so rare;

May Heaven show'r blessings

Upon her whom we love,

And after life's journey

May we meet her above. |

――――♦――――

JIM ROGERS'S WART.

(Reprinted, by permission, from "Teddy Ashton's

Annual.")

WE were set deawn

comfortably, Joe Short an' me, in th' Millers Arms, i' Blackpool,

suppin' a well-earnt pint apiece that is, we'd earnt it for walkin'

abeaut aw day injoyin' eaursels. We'd bin talkin' abeaut th'

Budget, an' he'd getten rayther excited, for Joe's a red-hot

Radical, while everybody knows I'm a Tory. Joe were gettin' th'

wust o'th' argyment, when he said, "Oh, bi hanged to th' Budget,

let's drop it; we'st be fawin' eaut in a bit." Just as he said

that, who should come walkin' in but Tum Entwistle, lookin' as glum

as if he'd swallowed a mustard playster.

"Hello, Tum!" we booath said at once. "What's browt

thee here? An' wheer's Sarah?"

I met just say as Joe Short, mysel', an' Tum Entwistle were

aw tacklers at th' same wayvin' shed i' Bowton, an' nobry ud never

seen or yerd o' Tum Entwistle bein' in a aleheawse afore, or ever

walkin' abeaut bi' hissel. His wench, Sarah Watson, were awlus

wi' him, so yo' may be sure we were surprised.

"Well," said Tum, "I yerd yo'd come to Blackpool for th'

wick-end, an' as I'd nowt else to do I thowt I'd come too. I

knowd yo'd stop at th' owd diggins, an' so I've planked mysel' theer.

But I didn't expect findin' yo' here. Sup up, an' have a pint

wi' me."

So we supped up, an' Tum cawd for three pints, an' then I

said: "But I thowt tha were a teetotaler; it I seems I'm wrung."

"So tha art," replied Tum, "for I broke when Sarah jackt me

up six wick sin, but I'st ha' to put th' peg in, or else I'st peg

eaut."

"Sarah jackt thee up!" said Joe, surprised; "well I never

yerd nowt like that. Whatever hasta done to desarve that

tratement?"

"Nowt as I know on," answered Tum, "except as Bill Wrigley's

bin hangin' after her a lung while neaw, an' th' last time me an'

Sarah were eaut together hoo were very sulky, an hoo towd me at last

hoo were tiret o' courtin'. Hoo wished me no harm, hoo said,

but I were too slow for an ordinary woman, so hoo'd made up her mind

to chuck it, until sombry turned up as ud talk abeaut gettin' wed

afore they'd keep a wench hangin' up for six yer, to be lifted off

th' nail just as he wanted.

"Well," axt Joe, "an' what did tha say to that?"

"Say! What could I say?" ansert Tum, wi' his een showin'

wayter. "I said nowt, an' hoo laft me, beaut even sayin' 'Good

neet.'"

I could hardly howd misel' when I yerd aw this talk, so I

chimed in: "Well, Tum, I never yerd owt like that noather. I

awlus thowt tha were slow when women were abeaut, but I did think

tha'd moor grit in thee than let an ugly beggar like Bill Wrigley

tak' a breet wench like Sarah fro' off thi shoe-tips. But

Bill's smart, an' no mistake. Tha'll ha' to get her back agen,

for I see tha'rt on th' down'ard track, an' if tha'rt gooin' t'

dreawn thi trouble i' drink tha'll find as th' drink ull dreawn

thee. '

"Tha'll ha' to get her back; an' I'll tell thee heaw to

manage it. But I'st ha' to tell thee a tale a true 'un and

if tha's sense enoof to act at onct on th' moral tha wins.

"It's ten yer sin' me an' Jim Rogers fust coom to Blackpool,

an' as we were single chaps we'd an idea e' pickin' up just to make

th' time pass in a jolly way; but, as tha'll see, Cupid nabbed us

booath, an' I durn't regret it. We were walkin' bi th' North

Pier when we met two bonny wenches, an' we know'd um bi seet, for

they booath weve at King's wayvin' shed. I durn't boast o' ony

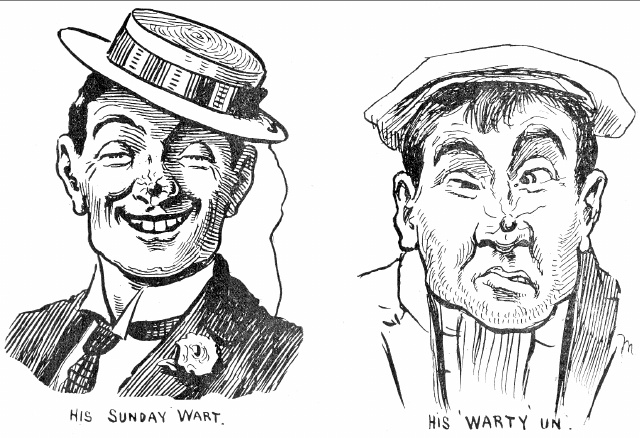

good looks mysel', but I mun say as Jim Rogers were th' feawest chap

I ever did see. He were flat-footed an' he'd a thick red nose,

an' at th' eend on it he had a big wart, an' this wart had toothri

hair growin', which, when he didn't trim um off, made th' wart look

like a deeod spider wi' its legs cocked up. Yet altho' he were

as ugly as a devil-fish, he were as breet as a star i'th' firmament.

"Well, we axt these wenehes to have a walk, an' they were

ever ready. So we happened to mate wi' th' reet uns, for we

each wed th' one we pickt. Neaw I soon fun' eawt as I were

only a second favourite i'th' cooartin' line, for eaur Nance thowt

me, I'm sure, awfully slow, just becos Jim went at it as if he were

on piece-wark, an' couldnt get through hawf enoof. We took um

on th' pier for a start, an' we weren't theer hauf an heaur afore

Jim hurried Bess (that were his wench's name) off to ha' suxnmat to

eit, an' laft me an' Nance gawpin' an' wonderin'. He said he'd

meet us at th' Tower at two o'clock; an' he were theer, an' Bess an'

aw. So we aw went in, an' Jim an' Bess danced every measure on

th' bill o' fare; then he bustled her into th' caffy for tay, an'

they were just finishin' when we fun wheer they were. Then

he'd th' cheek to tell us they were gooin' to th' theatre, an'

they'd see us awhoam, when th' play were o'er. An' he bustled

Bess off afore we'd hauf finished eitin'. So Nance an' me had

to walk abeaut like two softies wi' nowt to say, bein', so to speak,

strangers to one another.

"Nance has towd me mony a time abeaut Bess gettin' whoam that

neet, tired, but happy. Hoo'd never had such a day afore, an'

hoo thowt hoo'd getten th' nicest felly as ever lived. He

hadn't gi'n her time to look at his face, or else hoo met ha' thowt

different: an' hoo towd eaur Nance, too, as it were nice to

be kissed by a chap wi' a good mustache! Well, I fairly

chinked wi' lowfin' at that, for Jim were cleeon shaven, an' what

Bess had ta'n for a mustache were thoose three hairs on Jim's wart

ut had tickled her face! Well th' next day were th' same: Jim

bustled her off to Fleetwood, an' Bess never could tell us whether

hoo went theer on th' tram or bi wayter, but hoo did remember bein'

sick, an' when they geet to Fleetwood Jim trated her to brandy an'

oysters to mak' her aw reet again. An' when they geet whoam at

neet Bess could hardly stond, hoo were so tired, but hoo were very

happy, an' towd eaur Nance ut hoo were sure as Blackpool were th'

heaven they uset to sing abeaut in th' Sunday Skoo, an' Jim were th'

archangel showin' her th' seets o' Paradise.

There's an end to booath pleasure an' toil, an' of cooarse we

had to goo to Bowton again an' wark, but Jim kept th' bustlin' gam

up theer, an' I know Bess were fain when it were o'er, an' they coom

eaut o'th' church mon an' wife. They were wed twelve months

afore us, an' just as we were abeaut teein' th' knot they'd a babby

born. It were a lad, an' a nice choilt, too, but it had one

blemish, an' that were a wart on its nose. It were hardly

noticed at fust, but as th' choilt grew so did th' wart.

"Neaw here's th' mooast remarkable thing abeaut it; Bess

didn't know till th' choilt were born as Jim had a wart on his nose.

It coom eaut at th' kessenin'. They'd had a bit of a weet doo

at th' tay-time an' after, an' next mornin' Jim were sufferin' fro'

th' after-effects. He were set in th' rockin' cheer when Bess

coom deawn th' stairs o'th' Monday mornin', an' his een were a bit

blood-shot, an' his nose were redder nor usual, an' th' wart at th'

eend on it were as blue as a wimbery. Bess looked at him i'

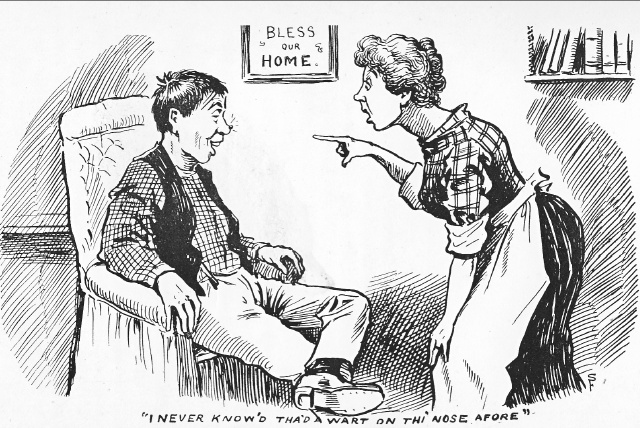

surprise, an' drew a lung breath. Then hoo said: 'Oh! Jim,

I've never had a gradely look at thee afore. If I'd seen that

face afore we were wed I'm sure I shouldn't ha' had thee.'

"Well,' said jim, 'tha'd plenty o' chances o' lookin'.

Why didn't tha look?'

"'Look!' said Bess. 'Heaw could I look? Tha never

gan me time to look. Tha bustled me abeaut too much . . . .

But theau'rt noan so bad to me, after aw, so I mun make th' best

o'th bargain. I never knowed as theau'd a wart on thi nose

afore, an' th' choilt taks after thee, I'm sorry to say. But I

durn't want that thing to stop at th' eend of its nose aw its life,

so we mun find some road o' shiftin' it.'

"'Oh, thats yezzy enoof,' said Jim. 'An owd woman towd

my mother ov a remedy when I were a lad, but I'd getten too big to

try it, but it owt to tak it off th' choilt. Tha mun get some

olive ile an' bath brick, an' bustle it off.' An' hoo did.

"So, Tum, tha sees th' moral. Goo back to Sarah; get

her to gie thee another chance, an' if hoo will tak thee on trial

again, bustle her."

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

That tale made a impression. A bit after we geet back to Bowton Tum

Entwistle left eaur wayvin' shed, an' geet a job as under-manager at

Horrocks's. He'd smartened hissel up a good lot, an' he'd begun o'

wearin' collars everyday. Abeaut six months at after Sarah coom to

eaur heawse one neet an' axt for me.

I were a bit surprised when eaur Nance sheauted as I were wanted,

for Sarah had never been afore. I axt her in, an' when hoo were set

deawn, hoo said:

"Anoch, Tum wants to know if thee an th' missis ull come to eaur

weddin' next Saturday but one."

"Why, I thowt theaud gin him up a lung while sin', bein', so to

speik, too slow for a ordinary woman." That were my chaff, an' hoo

smiled.

"Too slow!" hoo ansert; "not he. I uset think he were, but it were a

mistake. He's too sharp neaw; an' I'st oather ha' to wed him or be

killed. He runs me off my legs. He took me to Barrow Bridge a month

sin', an' when we geet to th' sixty-three steps he put one leg on

one side o'th ladder and t'other leg on th' t'other side, an'

slurred deawn th' lot, an' when he geet to th' bottom he looked up,

an' sheauted, 'Come on, Sarah.' 'Oh,'lord,' I thowt, 'does he think

I con get deawn like that?' an' I begun o' walkin' deawn th' steps. He were rayther impatient, an' when I geet to th' bottom I were eaut

o' wynt. As soon as I could get my breath, I said, 'Tum, this wark

ull have to stop; no woman could stond it. Tha'rt drivin' me to th'

grave.'

"I'm very sorry, Sarah," he says; "I durnt' want to do thee ony

harm; but if I'm gooin' too fast for thee let's get wed, an' then

theau con settle deawn."

"An' what didta say to that, Sarah?" I axt.

"Well, I were a bit tak'n back, for I didn't expect that just then,

but I thowt we'd courted lung enoof, so I towd him I were willin',

an' we went off theer an' then to put th' axins in. We're not makin'

a big fuss abeaut it, but Tum thowt he'd like Joe Short to stond as

th' best mon, him bein' sengle, an' he'd like yo' to come an' aw. Yo' seen, he's known yo' so long, an' he's warked wi' yo for mony a

yer."

"Let's goo, Anoch," said eaur Nance; "it's nobbut reet. I should

like to see th' weddin'." But that's just like eaur Nance; a woman

ud goo to a weddin' every day if hoo were axt.

"An' besides, th' manager o' Horrocks's is gooin' to China in a

fortnit, an' Tum's getten his job," Sarah said, "so do come."

That clinched it. It would ha' looked as if I were jealous o' Tum's

good fortin if I'd refused, so I towd Sarah heaw glad I were, an'

we'd goo, but I didn't know what I were lettin' mysel' in for, or I

shouldn't ha' promised. But I'll tell that tale another time.

――――♦――――

SCARPOLOGY.

WHEN their second

choilt were born Jim Rogers invited me o'er to Bowton. He towd me

i'th' letter they'd getten a bonny fat wench, as took after its

mother; an' as a bit of a joke, I reckon, he said its nose were aw reet. I knowd it ud be nice if it were like its mother, for Bess,

afore hoo were wed, were as nice a wench as ever ony chap

need get spliced to. So I went to th' kessenin', an' stopped wi' um

for th' wick-eend.

At th' Saturday neet we were sittin' i'th' heause smookin', an' Jim

were readin' th' evenin' papper. He turned to me an' said, "Listen

to this, Anoch," an' he read ―

YOUR BOOTS TELL YOUR CHARACTER.

Dr. Garrier, of Bale, declares that scarpology is a science to which

criminal investigators as well as others who wish to read character

accurately will have to pay more attention. It is the art of knowing

men and women by the examination of their footwear. The doctor says

that, given a pair of boots worn by their owner for at least two

months, there is not the slightest reason why one should not be able

to tell the character, disposition, and habits of the wearer.

"It is impossible to over-estimate the importance of this new

science," says the doctor, "for by careful practice one may, after a

few minutes' acquaintance, be able to gauge a man at his worth, and

this simply by glancing at his feet."

"Neaw", he said, "what dost think o' that for

rubbitch?"

"I durnt know abeaut its bein' rubbitch," I said; "doctors

are gettin' very clivver neaw-days. Look at that French chap

I think his name's Bertillon he con tell a thief bi his finger

marks."

"That may be," replied Jim, "but heaw the deuce con he tell a

chap's karraeter bi lookin' at his shoon. If it were his feet

I could understond it. We'st ha' some doctor sayin' in a bit

as he con tell a chap's name if he nobbut smells his breath! . . . .

Nawe, I'st noan believe it."

"Well," I said, "th' subject's too deep for me, so I cornt

say owt abeaut it; but, if there is owt in it, we'st ha' to be

careful wheer we plant eaur feet, an' we'st ha' to brun eaur owd

shoon when we'n done wi' um, or else th' nayburs ull be sayin' as

its us as stole their clooas off th' lines o' weshin' days.

An' we'st not ha' to leove eaur shoon eautside o'th' bedroom dur at

th' lodgins when we goo to Blackpool for th' holidays, or else th'

sarvants ull happen swop um, an' we'd praps get a pair wi' a bad

karracter."

"Aye, that met be done," said Jim, "if there were ewt in it,

but there isn't. Tak my shoon for a start. Tha knows my

feet are not what I should like um to be, bi a lung way, but I cornt

help it. An' yet I durnt think I'm a bad karracter."

Bess were bathin' th' lad i'th' kitchen, when hoo popped her

yed i'th' durway, an' said, "Well, Jim, tha knows tha'rt not as good

as tha should be sometimes."

"Well, if I'm not, what's that to do wi' my feet or my shoon?

I'm noan so bad to thee, after aw. Tha'd better sheaut i'th'

street as tha feeshed for a' angel, an' nobbut a mon swallowed thi

bait."

Jim were nettled at Bess for interruptin' him, for he doesn't

oft talk to her that road. Hoo'd sense enoof to see hoo'd hurt

his feelins, so she said no moor. Jim turned to me again, an'

went on: "As I wur sayin', heaw could he tell my karracter bi my

shoon. I have to goo to Manchester to be measured for um bi a

chap as does nowt else but make shoon to fit one's feet i'stead of

fitting th' feet into his shoon. Neaw, look at these," an' he

pickt his Sunday shoon up, which were laid aside o'th' fender, "they

durnt look like shoon, dun they? Well, they're yezzy, an' I

mun have um yezzy, for on my left foote I've getten two bunions, as

hard as Billy Mug's face; an' when I were a lad, Ned Cunliffe's

tacker-up slipped off th' flag he were liftin', an' it dropt on my

big toe, an' split th' nail, an' ever sin' then its grown uppards

istead o' lengthways, an' every neaw an' again I have to file it

deawn. An' my reet foote's wuss. Under my big toe I've a

nasty corn as speils my razzor every time I cut it, an' on my fourth

toe I've another corn what I cornt ger at to keep in order; an' in

th' baw o' my foote I've a segg as big as th' bush uv a cart wheel,

an' it makes me yell 'Jerusalem' sometimes. So heaw the hee

con onybody tell my karracter fro' th' boots I have to wear if I'm

to walk at aw.

"I'll show thee heaw a chap's karracter connot be towd fro'

his shoon. I remember two-thri yer sin I'd formert a new pair

in Manchester, an' when they were ready I went for um. I put

um on in th' shop to see if they were aw reet, an' as they were

yezzy to my feet I kept um theer. Th' shoemaker lapt mi owd

shoon in breawn papper, so I browt um that road, intendin' to wear

um eaut, as they weren't hauf done. I put um on th' rack in th'

train, an' when I geet to Bowton I forgeet um. I bethowt me th'

next day, an' wrote to th' company axin if they'd fun a pair o' big

shoon in a railway carriage. In abeaut a wick I geet a answer

that they'd fun nowt o' that soart, but on th' train I travelled by

they'd fun two postmen's leather bags lapt i' breawn papper, an'

they'd sent word to th' post office i' London, as they thowt they'd

bin stown! Well, I felt thoos were my shoon, but I made no

bother, an' forgeet um. In a while after I were i' Manchester

again, an' I happened to pass a auction reawm, an' I went in when a

chap towd me they were sellin' t' things wot had bin left an' lost

in railway trains. I bethowt me o' my shoon, when, behowd, in

a bit th' auctioneer put up two pair, an' I could see as one pair

were thoos I'd lost! Tha's yerd auctioneers' gammon when

they're sellin' stuff. They think they're clivver, but that

mon geet three bob less for them shoon than he would ha' done but

for his joke. He said he didn't know what to caw th' big pair,

but if they were shoon they'd belunged to a foote pad. I were

a bit riled at that, for I'd noticed a policemen in th' place lookin'

at my feet, an' I sheauted eaut, "Heaw dost know he were a foote

pad?" He ansert in a jiffy, "Becos th' chap as wore um 'ud

have to pad his feet!" That were good for him, an' th' folk

lowft, aw except me. So I nobbut offered him a bob for um, an'

he knocked um deawn for that. I sowd t' other pair for

hauf-a-creawn to a chap as couldn't forshome to bid after th'

auctioneer's joke, an' as I were comin' eaut th' bobby as I

mentioned followed me, an' axt me t' let him look at um. I

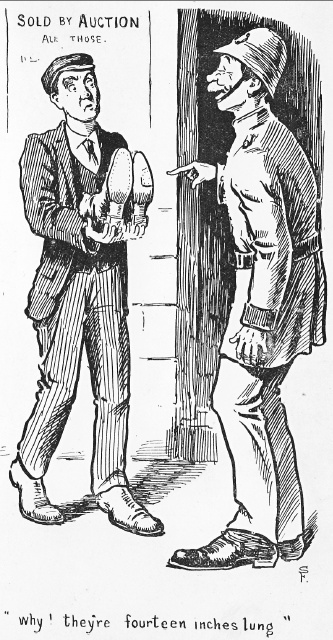

did. "Why," he said, "they're fourteen inches lung!"

"They're pratty big," I ansert. "Well, if I were thee I'd tak

these to th' Teawn Ho', an th' Chief Cunstable 'ull happen gi' thee

ten shillin' for um. Tha sees th' littlest policemen i'

Manchester has fourteens feet mine's sixteens an' they're flat,

like thine. They're bothered abeaut gerrin' shoon to fit um,

an' thine's just th' pattern. Tak um to him."

"An' did tha tak um?" I asked.

"Nawe, I didn't want th' bother, as I'd getten um back for

nowt, wi' my railway fare chucked in, so I browt um back, an' wore

um mysel'."

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Bess has towd eawr Nance as when Jim were coortin her he

could mak' her believe owt, an' I think sometimes he ratches um when

he tells me a tale, but I con pleeos mysel' abeaut believin' it, so

I say nowt. I towd him, heawever, that there were rayson in th'

argyment part o' what he said, an' we'd caw th' new science o'

Scarpology Scrapology.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

I connot finish this beaut sayin' as th' kessenin' next day

passed off very well. I gan th' choilt away that's what they

caw godfaytherin' I think an' they cawd it Bess, like its mother.

It skriked a good deeol when th' minister degged its face wi' cowd

wayter, but I thowt he put moor on nor were needed, an' I shouldn't

ha' liked it mysel'. We'd a champion tay, an' Bess were very

nice. Hoo temd summat eaut of a bottle, wi' a goold label on,

into every cup we had, which set me an' Jim talkin' like magpies,

an' I tried next mornin' to think what we'd argued abeaut, but 'twere

no use, I couldn't remember.

It's th' fust time I've bin at godfayther, but it's aw reet,

an' if ony decent young married couple wot has a new babby ull ax

me, I'll get my white wescut weehed an' stond for um under th' same

conditions.

|

[Lines for a Christmas Card.]

HO! FOR A MERRY CHRISTMAS.

WHEN

the snowflakes fall, and the drifts gather deep,

And the harsh wintry winds are hushed into sleep,

When the sun brightly shines, tho' the frost be keen,

That is the right sort of good weather, I ween,

For a Merry

Christmas.

When the yule-log's ablaze up the chimney high,

And the keg is just breached, and the port tastes dry,

When the sizzling turkey is done to a turn,

And the sauce on the pudding is sure to burn

That's the

fare for Christmas.

When father comes home muffled up to the chin,

And mother shouts "Welcome!" and ushers him in,

He's quickly besieged by his girls and his boys,

For they know his pockets are laden with toys,

For a

Children's Christmas.

When the rich man's larder is filled with good cheer,

And his books show a rise in trade for the year,

If he's thought of the hungrycheerless and cold

And gen'rously helped them with silver or gold,

He's a Merry

Christmas.

My wishes for all on this auspicious day,

For my kindred at home and friends far away,

Is that Heaven may grant them the best of health,

And Fortune endow them with plenty of wealth,

For many a

Christmas. |

――――♦――――

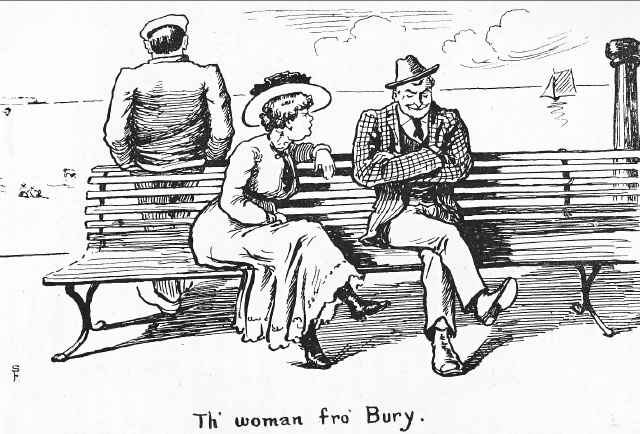

TH' WOMAN FRO' BURY.

A Sketch at Blackpool.

I SUPPOSE most

folk who enjoy fair health like a good stroll. I know I do,

and one of the pleasures of my life is in walking in the early

morning from the Gynn Inn along the Promenade to South Shore Fair

Ground. It is, in fair weather, a glorious experience.

Three-and-a-half miles along the cleanest and widest promenade in

England probably in the world every yard of it asphalted, with

no hills to climb, the ozone-laden breezes gently filling one with

physical purity, is a splendid tonic indeed. Walks like that

inspire one with hopes of joyful life, and are a panacea for many of

the ills that afflict overworked or harassed humanity. Young

people may gain strength by indulging in it; the middle-aged may

take such a walk with advantage, and if the return journey should

prove too much for them, the enterprise of Blackpool Corporation has

provided comfortable tramcars whereon they may return, all along the

coast, at a moderate fare.

When I have walked the whole length, and back to the North

Shore, I generally indulge in a rest, and if I can manage it I take

a seat on the form nearest to, but south of, the North Pier.

Sometimes I have to wait awhile, and when any of the sitters vacate

their places it is necessary to dodge or rush quickly, as most

visitors seem to favour that particular form as a resting-place.

There is much to be seen about there: the crowd is so dense, the

fashion of Lancashire congregate near and upon the North Pier, and

there the student of the philosophy of life may see its tragedy and

comedy kaleidoscopically portrayed. There the gushing maiden

and her lover (temporary or otherwise) trip on light feet, she

smiling sweetly at the sun-burnt talk her Adonis is pouring into her

too-listening ears, each careless and fearless of the future before

them; then the aged couple, possibly on their last seaside holiday,

slowly hobbling along, with little or nothing to tell each other,

but remembering the days of long ago, when, with cheery hearts and

lightsome feet, they joined in the revelries associated with youth.

Then comes a bath chair with an invalid, probably weary of life, yet

sent to the seaside by friends, who count not the cost, wishful to

keep their loved one longer on earth. Here follow four or five

young roysterers, without headgear, and dressed loudly, humming the

refrain of a comic song they had probably heard at one of the

amusement palaces the previous night. The scene has no charm

for the next one who passes a boy just merging into manhood, who

is being wheeled on a stretcher carriage. He has lost his

youth, his half-shut eyes lack lustre, consumption has laid a fast

hold of him, and he no doubt feels dead to the world, but he is

wheeled gently by his father, who is making a toil of his holiday in

the hope of benefitting his boy, a parent's labour of love.

Thus the interesting panorama continues without cessation as long as

the day lasts.

One afternoon, after a long walk, I was fortunate to secure a

seat on my favourite form. The day was an ideal one: the sky

bright blue, with here and there a streak of cirrus cloud, the edges

of which were turned to pink as they passed over the sun, whose

fierce glare reflected a phosphorescence of such varied colours upon

the calm sea as to render its beauty beyond my powers of

description. It was a picture not often to be seen, even at

Blackpool.

I was not seated long before the heat and the sun's glare

overpowered me, and I had to leave my seat. There was room for

me on a form opposite, where I might escape the sun's fierce heat,

which seemed to grow stronger, so I sat there and dozed.

When I had lost outward consciousness, and had, in perhaps two

minutes, dreamed of pleasantries that would only fall to one's lot

in a whole lifetime, I was startled by a sudden thud on the form

whereon I was seated, and an exclamation that sounded like a painful

long-drawn-out "Oh-o-o-o!" I rubbed my eyes and looked around.

The left half of the seat had been vacated during my somnolence, for

it was getting teatime, and the only other occupant was a woman.

I turned my head to the right to look at her, and she sat sideways

facing, and looking straight at me. She was a fine specimen of

womanhood, with a round red face, and the day's heat had rendered

necessary frequent applications of her handkerchief to keep pace

with the perspiration that would otherwise have rolled off her, for

her hair was plastered down on each side of her face as though her

head had been dipped in oil. Yet withal, for a matron she was

not bad looking, but just now she was troubled, and her contracted

countenance gave her an appearance of abject misery. And her

feet troubled her; this was apparent from the manner in which, with

great effort, she now and again knocked the heel of her right boot

on the asphalt pavement, lifting me out of position at each savage

blow. Then she would cross her right leg over the left, and

give another grunt, right from the depths, which sounded "U-u-u-gh."

I became interested, and noticed that whilst she sat very

close to me, her face directed towards me but staring at nothing,

there was room on the right of her for another person to be seated.

Possibly she expected someone ― we should see. But I dozed

again; I couldn't help it. In a while I was aroused by voices

in altercation, and turning, saw a man of medium stature leaning on

the back rest of the seat, the front part of him facing the sea.

He was her husband, and was obviously the junior partner at

home. I could tell by his attitude he was guilty of ―

something, but I knew not what. She told me, however, when,

after expressively banging her right heel on the pavement to relieve

the pain from her corn, she addressed him:

"Th' next time tha brings me to Blackpool tha'll not leove

me, I know, for I'st never goo eaut wi' thee again as lung as I

live."

"I didn't leove thee o' purpose," he replied sheepishly, "tha'

knows I only went to have a pint wi' thoose two Bury chaps tha

knows um, they sen so an' when I coom back tha'd gone."

"Aye, an' I reckon tha went back wi' um, an' filled thy guts

wi' dirty ale, whether I geet owt or nowt. It didn't matter

abeaut me, did it?"

No answer being forthcoming to that pertinent inquiry, there

was solemn silence for a while.

Presently two men approached. Dressed in dark tweeds,

slack-back coats, and light-coloured cloth caps, their trousers were

turned up at the bottoms, and they were each smoking short clay

pipes. They stopped opposite me, evidently recognising their

pal from Bury.

"Hello, Sam," said one, addressing the man with his back

turned towards them, "we missed thee aw at once. Wheer did ta

goo?"

But, whilst waiting for a reply, they caught sight of a pair

of searching eyes that belonged to the woman next to me, and the

spokesman, a little non-plussed, ejaculated, "Hello, Mrs. Haton, are

yo' here? We didn't know yo'd come."

"Neaw, I daresay not; so yo' crack, but yo'n had him aw day,

an' yo' con have him neaw. I reckon when yo' made him drunk yo'

wanted to get shut on him."

"Nay, he weren't drunk when he laft us two hours sin'.

He'd only had three pints. He towd us he'd come by hissel'."

"Did he?" she asked. "He awlus were a liar. But

tak him again. I durnt want him."

The man took the clay from his mouth, and, after some

hesitancy, ventured: "Well, we're gooin' to Fleetwood. We'n

three heaurs afore th' train goes. Will yo' booath come?"

"Nawe," she answered vehemently, as she banged her heel again

on the ground to relieve the twinge of pain from her corn, "I'st not

goo; but tak him, he cares nowt abeaut me, so's he fills hissel' wi'

drink."

There was silence for several minutes, during which the

quartette stared four different ways. Then the man who had

been spokesman said: "Well, if yo' worn't come, we'll goo.

Good afternoon." He was glad to get away.

At that moment there was a catastrophe like an earthquake;

the form suddenly heaved, lifting me several inches in the air; the

husband scooted, thinking his wife's wrath was bursting in a

castigation of himself; and their acquaintances stopped and turned

to see the cause of the earth's vibration and noise.

Th' woman fro' Bury had encountered her worst spell of pain

from her corn, and that, coupled with her mental irritation, had

caused her to bang her right heel on the ashphalt with such force as

to cause her to gurgle "U-u-gh" at each stroke, and everything in

her vicinity to shake and tremble. She got a little ease,

however, from the exercise, and her husband dared to resume his

position at the back of the seat.

There was silence for quite a long while, then the man spoke:

"Wilta come an' have some tay?"

"Nawe, I want no tay. I want nowt, but to get whoam.

Th' next time tha axes me to come to Blackpool, or anywheer else,

I'll break thi yed."

The man was cowed. After a long silence he again

requested: "Wilta come an' have a drop o' gin?"

"Nawe, I'st not," was the reply, but a faint smile played

round her mouth. She was winning!

"Yah do," he entreated, "tha'll be famished."

"I'st not, I tell thee again," she replied.

"Well, come an' ha' summat to eit. It's no use o'

speilin' thy eaut." This he urged persuasively.

"That were spelled lung sin'," she replied bitterly, "when

tha laft me to go wi' thoos drunkards. Tha didn't find their

wives comin' wi' um. They'd moor sense."

"Well, durnt bother, lass. I'st know better next time.

Come an' have summat; tha'll be ill." From the tone of his

voice I wondered whether his sympathy was genuine or his fear was

strong.

She uncrossed her legs, and tapped her right heel twice or

thrice on the ground, so gently now as seeming to coax her corn into

better behaviour, and, with a grunt lifted her stout body erect, and

she followed him into Talbot Road. I saw them enter the Wine

Lodge.

There was peace, but the victory was hers. |