|

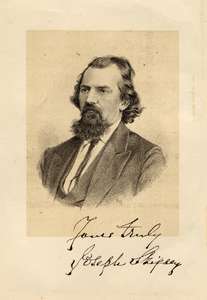

1. Joseph Skipsey:

A Brief Biography

by Basil Bunting.

|

|

|

JOSEPH SKIPSEY

(1832-1903) |

A man's circumstances seldom matter to those who enjoy what he makes.

We buy our shirts without asking who the seamstress was, and should read our

poems without paying too much attention to the names they are printed over.

Things once made stand free of their makers, the more anonymous the better.

However, there are exceptions.

The poems JOSEPH SKIPSEY made stand in a territory of their own, fenced off

on one side from the nameless elaborators of ballad and folksong and on the

other from literary poets who have taken what advantage they could of ballad

and folksong conventions. Burns had a language and a whole literature

of forerunners, an album of tunes to find words for and an output of very

sophisticated satire to underpin his songs; but Northumbrian is only a

spoken language, with no recognisable spelling, as Swinburne found, and no

literature of its own within the last four centuries, except anonymous

ballads. The Scottish small-holder had an education, however brief:

the Northumbrian pitman had none. On the other hand, the process of

balladry had ended, at least in the pit villages, before Skipsey's time.

He had to speak with his own mouth even when he meant to speak for all his

people.

Thus the facts of Skipsey's life are useful, not as Burne-Jones thought, to

excuse his shortcomings though his shortcomings are plain, but to define his

qualities, which, perhaps, the historians of literature have failed to

perceive.

Joseph Skipsey was born on the 8th of July 1832 [1] at Percy Main, near North

Shields, in the midst of a turbulent strike. The pitmen wanted two

shillings and sevenpence a day and a twelve hour day (with waiting time at

the shaft that would make at least thirteen hours on most days) but the coal

owners got the help of special constables to club such extremists back to

work. Joseph's father, Cuthbert Skipsey, overman at the pit, stepped

between one of the special constables and a man he was bullying, and was

shot dead by the constable for his intervention. The zealous ruffian

was sent to prison for six months and Mrs. Skipsey was left without

pension or relief to feed her eight children on nettle broth until they were

old enough to go down the pit. That was not long. The youngest,

Joseph, was set on as a trapper at the age of seven, to regulate the

ventilation by opening and shutting a door when the wagons passed through

for sixteen hours a day - the strike had failed. What Joseph earned is

not recorded, but can be inferred from the fact that ten years later, when

he was promoted to be a putter, he was paid five shillings a week.

The coal owners were much too thrifty to supply candles to trapper boys.

The children sat in the dark. Except towards midsummer they never saw

light at all except on Sundays (for they started before dawn and ended after

sunset) unless a passing hewer or putter might spare one of them a candleend.

By such occasional light Joseph taught himself to read and write, imitating

the print on playbills and throwaway advertisements in chalk or

finger-tracings on his dusty door. William Straker, president of the

Northumberland miners, told me that he had a similar education a score of

years later. My great-grandfather got no candles. He taught

himself to play the tin whistle when he was a trapper in the dark.

Some pits lowered and raised their men and boys in cages, as now.

Other coal owners thought that made men soft. They provided only

ladders, or else an endless chain with stirrups, to which weary children

clung as best they could. Skipsey saw another seven-year-old whose

grip slackened. He called to his brother behind him: "A'm gannen to

faal, Jimmy". "Slide doon to me, hinny", his brother answered, but

could not hold him and both were killed at the shaft bottom. William

Straker's first pit had ladders, up which the boys swarmed, each followed by

a man huddling up to catch him if he fell. At home, Skipsey told

Spence Watson, it was still nettle broth for supper, with a slice of bread

on lucky days.

Before he owned a book or had seen more than a glimpse of the inside of one

Skipsey made songs his mates picked up and sang. "I have never known

anyone who got more excellent enjoyment out of song", Spence Watson observed

many years later. Skipsey's first books, given him by an uncle when he

was fifteen, were a Bible, Pope's Iliad and a worn Paradise Lost.

Two years later when he became a putter he saved out of his weekly five

shillings to buy a Shakespeare. He had tried to get the Bible by

heart, but transferred the effort, more successfully, to Shakespeare from

whom he could still quote whole scenes verbatim in old age. He read

Burns too, translations of Greek dramatists and a little political economy.

That may be said to have been his whole education, though he went on reading

all his life and was certainly influenced both by Blake, and by Heine in

translation.

At twenty Skipsey walked to London - the train was too dear - but found no

other fortune there than a wife, whom he brought back to the north where

they tried to set up a village school. The fees were too small to live

on, so for the rest of his life bar three short intervals Skipsey worked in

the pits, though his friends tried several times to fit him into some more

comfortable trade. He was thought in Northumberland to be a very

strong and skilful hewer and a reliable man for deputy, but the deputy's

responsibilities lay so heavy upon him that he went back to his pick.

In 1859 his first book was printed at Morpeth. It was hardly noticed.

However, three years later, when the whole country was horrified by the

Hartley colliery disaster, Skipsey composed a ballad about it which he read

at many meetings to gather funds for the widows and orphans. Spence

Watson says: "It was not at all like the reading or recitation of other

men... He waited quietly until he felt the spirit of that which he was

about to do come upon him. Then he was as one possessed, everything

but the poem was forgotten, but that he made to live, or perhaps I should

more truly say that he incarnated it; he actually became the poem himself.

His features changed with every expression of the verse, his hands, nay,

even his fingers, expressed the meaning of the words, and that meaning

thoroughly revealed itself. It was far beyond what you had thought of,

but it stood out clear for you ever afterwards."

Robert Spence Watson of Bensham was then a young Newcastle solicitor of an

ancient Quaker yeoman family from Allendale. His wide sympathies with

the art and thought of his day and the great influence he gained behind the

scenes of the radical section of the Liberals brought him an immense

acquaintance ranging from Mazzini to the Pre-Raphaelites, from scholars to

cabinet ministers, most of whom, when they became his guests, sat at table

and conversed with Joseph Skipsey. Skipsey's table-talk is said to

have been trenchant and accurate. Spence Watson's guests listened and

marvelled, but usually did nothing to help the poet. He did not become

a part of the so-called world of letters, he was only brushed lightly by its

fringe.

The other permanent friend Skipsey's early poems brought him was Thomas

Dixon, the Sunderland cork-cutter to whom Ruskin addressed the letters

published as Time and Tide. Dixon's own letters are extant but

have not been published, and I have not been allowed to consult them.

Ruskin's do not mention Skipsey.

Spence Watson had found a place for Skipsey as sub-librarian to the

Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society, but the pay was too meagre;

and another, as porter at the newly founded Armstrong College, now the

University of Newcastle on Tyne. There Spence Watson's own

middle-class marrow was curdled when Lord Carlisle, walking with the

Principal, paused to talk to Skipsey, who set down two scuttles of coal to

shake hands. "It was quite impossible to have a college", Spence

Watson wrote, "where the scientific men came to see the Principal and the

artistic and literary men came to see the porter." Burne Jones took

pains to have Skipsey made custodian of Shakespeare's house at Stratford on

Avon, just the job, he must have thought, for a poor man who knew almost all

Shakespeare's work by heart. The list of those who supported Skipsey's

application included "Browning, Tennyson, John Morley, Burne Jones, Dante

Gabriel Rossetti, Theodore Watts, Leighton, F.R. Benson, Andrew Lang,

Lord Carlisle, W.M. Rossetti, Austin Dobson, Brain Stoker, Lord

Ravensworth, Thomas Burt, William Morris, Wilson Barrett, Edmund Gosse,

Professor Dowden and many other men of mark." This battalion prevailed, and

the "tall, portly, well-proportioned man, with a fine grave face ... a

somewhat retiring and aloof expression" and a strong Northumbrian accent

moved to Stratford-on-Avon to usher a continual flow of mainly American

tourists through the rooms, answer their questions and put up, if he could,

with their continual assertion that it was Bacon who wrote the plays.

Skipsey could not endure it and returned to the pits after a year.

Burne Jones tried again and persuaded Gladstone to grant Skipsey a Civil

List Pension of £10 a year, raised later to £25.

Skipsey was master-shifter for a while, I think at Backworth, where he

helped to give the village its reputation as a centre of workingmen's

thought and education. Throughout the eighties he was editing

selections of Coleridge, Shelley, Burns, Blake, Poe and other poets in his

spare time for the publishing house of Walter Scott at Felling. His

prefaces, like those of his contemporaries, are too long and too verbose,

but sometimes unexpected or acute.

Three times in his later life Skipsey travelled for pleasure; once to visit

the Lake District with the Spence Watsons and once on a rich Australian's

yacht to sail up the Norwegian coast where he renewed his friendship with

Fridjof Nansen a little before the Fram sailed on its famous North Pole

voyage. The other time, a little earlier, he went to London with

Thomas Dixon to call on a number of Pre-Raphaelite poets and painters.

They probably met Ruskin too, but there is no record of it.

Skipsey lived to be 71. His wife [2] died more than

a year before him, and the dignified, rather austere old man was cared for

by his housekeeper, a grand-daughter, Jane Skipsey, just twelve years old. His son William was inspector of schools at Durham, his eldest son, James,

[3] master shifter at

the Montagu colliery at Scotswood, where Joseph Skipsey sometimes visited my

father, the colliery doctor there; but I was too young to have any memory of

him. He died at Harraton in September 1903. [4]

It will be seen that I have hardly been able to add anything to the account

Spence Watson gave of Skipsey in his memoir published in, I think, 1909,

though I sought out several of the survivors of his family. They

remembered him with awe, but not with knowledge.

Spence Watson wrote rather distrustfully of Skipsey's poems. Burne

Jones dismissed them: "Of course his poems are not much to us; only one

measures by relation', and sometimes the little that a man does who has had

no chance whatever seems greater than the accomplished work of luckier men -

on the widow's mite system of arithmetic. . ." Burne Jones and

Spence Watson were not poets. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who was, saw

more clearly; "Joseph Skipsey, the Northern Collier Poet, a man of real

genius."

There had been nobody to point out to Skipsey where his improvised technique

failed him, so that his work is full of clumsinesses he could easily have

avoided if he had once been shown how. The reader must accept them,

for the sake of the admirable poems they are embedded in. Narrative

and rhythm alike sometimes seem to stumble where there is no real obstacle.

When Rossetti pointed out one of these failures of technique, Skipsey was, I

suppose, too set in the bad habit to change it.

Rossetti wrote: "I am gratified to know that my poems appeal at all to you.

Yours struck me at once. The real-life pieces are more sustained and

decided than almost anything of the same kind that I know, I mean in poetry

coming really from a poet of the people who describes what he knows and

mixes in. Bereaved is perhaps the poem which most unites poetic

form with deep pathos: the Hartley ballad is equal in another way, but

written, I fancy, to be really sung like the old ballads.

Thistle and Nettle

shows the most varied power of all, perhaps. In this, and throughout

the book, the want I feel is of artistic finish only, not of artistic

tendency: the right touch sometimes seems to come to you of its own accord,

but, when not thus coming, it remains a want. Stanzas similarly rhymed

are apt to follow each other, and the metre is often filled out by catching

up a word in repetition - I mean, as for instance, 'Maybe, as they have

been, maybe' etc.

"Other favourites of mine are Persecuted,

Willy to Lilly,

Mother Wept (this very

striking) and Nanny to Bessy. It seems to me that, as regards

style, you might take the verbal perfection of your admirable stanzas

Get Up as an example to

yourself, and try never to fall short of this standard, where not a word is

lost or wanting. This little piece seems to me equal to anything in

the language for direct and quiet pathetic force."

All Rossetti told Skipsey is just. But a twentieth century reader may

find faults that belong as much to the age he lived in as to Skipsey

himself, occasional intrusions of what Samuel Butler called 'Wardour Street'

into his vocabulary, for example. 'Wight' has no more place in modern

English or modern Northumbrian as a synonym for 'man' than 'gome' or 'freke',

though probably every voluminous poet of Victoria's reign hid a whole

population of wights in his pages. 'Maid' is good English and good

Devonshire, but we say 'lass'. Such deviations irritate only a little,

but often.

Skipsey was too ready to confuse his syntax in order to keep the stresses on

the theoretical beat of the metre, not knowing, or not noticing, how one

syllable drawn out beyond the metrical limit can keep the swing of the

rhythm yet introduce an expressive change of pace; but in this too, though

he was clumsier than many, he was following the usage of most poets of his

time. He does not use many dialect words nor many 'terms of art' from

the collieries, but now and again he seems to have funked setting down the

dialect syntax which was in his head and made clear sense to put in its

place something of which it is hard to make sense at all.

Since Skipsey's own pronunciation was always that of Tyneside (but of

Tyneside before the Irish navvy immigrants had made 'geordie' of it), I

think the way to read his verse is to give the word spelled as the

dictionary spells it the often unspellable sound it has between Alnwick,

Hexham and Tynemouth. If the page says 'called' I would read 'ca'd'

except where metrical propriety forbids it, and so on. But Skipsey

baffles me when he rhymes 'night' ('neet') with 'wight', which has, so far

as I know, no Northumbrian sound. Its Old English sound would have

fitted ('weet'), but it is not to be found in northern writers - once in Sir

Gawain and once in Pearl, meaning, in each case, a young girl; in Beowulf, a

thing.

But when all faults of technique, of vocabulary and of syntax have been

added to the difficulty of reading a dialect written in the spelling of the

capital Skipsey still has power to please and to move, sometimes, as

Rossetti told him, as powerfully as anything in the language. It is

easy to feel the strength of the pitman's fear of the pit when he expresses

it. It may be less easy for such city-dwellers as we have become to

acknowledge the truth of the pretty incidents of pit village courtship,

especially since there is a convention which must be observed. The

things you may publicly admire in a girl, the things you may compare her to

are fixed by what was originally a rustic tradition, withered in the towns

and apologised for by villagers aware of town scrutiny, but not dead in the

least. Only the ornaments change a little. The lad Skipsey's

lasses admired for dancing and wrestling plays football now. It is in

handling such matter that Skipsey comes nearest to the folksong, at times,

like it, practically anonymous. But always he is very close indeed to

the people and the life, as little embarrassed by its prettiness as by its

pain. Burns sees Ayr and Dumfries vividly but from outside. He

is not one with the people he observes. But Skipsey hardly sees Cowpen

and Percy Main at all. He is inside the pit village, part of it, and

but for a certain dignity of bearing, we might say he was the village itself

composing.

So this preface comes back to its beginning. Skipsey is the most

impersonal of poets, very close indeed to the anonymous ballad singers and

folksong singers, yet with his own voice and his own manner, holding a place

of his own between them and such poets as Burns. The best of his work

is utterly convincing, even when its faults are obvious. He ought not

to be forgotten. The general anthologists owe him a page or two. |

|

Bibliography:

-

Poems,

Songs, and Ballads. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1862.

-

The

Collier Lad, and Other Lyrics, 1864.

-

Poems. Blyth: William Alder, 1871.

-

A Book of Miscellaneous Lyrics. Bedlington: printed for the author

by George Richardson, 1878 .

-

Carols

from the Coalfields. London: Walter Scott, 1886.

-

Songs

and Lyrics. London: W. Scott, 1892 (limited edition of 250 copies).

-

Watson,

Robert Spence. Joseph Skipsey, his Life and Work. London: T.F. Unwin,

1909.

-

Selected

Poems. Ed. Basil Bunting. Sunderland: Ceolfrith Press, 1976.

――――♦――――

Footnotes.

(Information provided by Skipsey's great grandson,

Roger J. Skipsey—

see also Family

Documents)

1. The date of birth given by Bunting

is incorrect. Skipsey was born on 17th. of March 1832.

2. Skipsey married Sarah Fendley in December 1868

(after the deaths of five of their children.) Their three children

who survived into old age were:

Elizabeth Ann Pringle Skipsey b. 1860, married

John Harrison;

Joseph Skipsey b.1869 married Sarah Leech (three

single daughters);

Cuthbert Skipsey b.1872 (one single daughter and

my father, Joseph Fendley Skipsey).

3. There is no record of sons James and William, or of

a granddaughter Jane.

4. Joseph Skipsey died on the 3rd. of September 1903

at my Grandfather`s home, 5 Kells Gardens, Low Fell, Gateshead.

Not with his daughter Elizabeth at Harraton. |

――――♦――――

|

2. Biographic Sketch

by

ROBERT SPENCE WATSON.

(Appended to 'Carols from the Coal-Fields').

___________ |

|

I HAVE been

solicited to say a few words about the author of this book, and I think

that his readers will be sufficiently interested to wish to know something

about him. As we have been intimate friends for more than twenty

years, I have not much difficulty in the task.

The poems must stand or fall upon their merits. The

conditions under which they have been produced do not affect their

literary value. But so far as form and style go, the critic will

only be able to come to a sound judgment when he knows something of those

conditions. The author is a Northumbrian born and bred; his speech

is racy of the soil. Northumbrian pronunciation is other and older

than that which obtains amongst our south-country kinsfolk; this must be

borne in mind when in these poems a rhyme may seem uncouth or even

non-existent; it is probably only to our manner born. A

south-country Englishman may read even Robert Burns's finest verses as

though they had but little of the jingle of rhyme about them.

Joseph Skipsey has passed the greater part of his life in

coal mines; he comes of a mining race. Having lost his father when

yet a child in arms, and his widowed mother having seven other children to

care for, he had to begin work early. At seven years of age he was

sent into the coal pits at Percy Main, near North Shields. Young as

he was, he had to work from twelve to sixteen hours in the day, generally

in the pitch-dark; and in the dreary winter months he only saw the blessèd

sun upon Sundays. But he had a brave heart; he was paving his way,

and he was determined to get wisdom. When he went to work, he had

learned the alphabet, and to put words of two letters together, but

nothing more. He devoted such scanty opportunities of leisure as he

could get to learning to read, write, and cypher. He was his own

schoolmaster. He taught himself to write, for example, by copying

the letters from printed bills or notices, when he could manage to get a

candle end,—his paper being the trap-door, which it was his duty to open

and shut as the waggon passed through, and his pen a bit of chalk.

The first book he really read was the "Bible," and not

content with reading it, he learned the chapters which specially pleased

him by heart. When sixteen years old he was presented with an old

copy of Lindley Murray's Grammar, and by the aid of that unrivalled, if

old-fashioned work, he gained some knowledge of the structural rules of

his native tongue. He had already become acquainted with "Paradise

Lost," and was another proof of the truth of Matthew Prior's axiom, "Who

often reads will sometimes want to write," for he had begun to write verse

when only "a bonnie pit lad."

I need not follow his subsequent career in detail. For

more than forty years of his life he has laboured in "the coal-dark

underground;" he has had a short experience of storekeeping in a

manufactory, and of acting as assistant in a public library; and is now

the caretaker of a Board School in Newcastle-upon-Tyne,—an office of much

labour and small emolument, which affords its fortunate possessor little

opportunity of lettered ease.

I must say a word or two more about Joseph Skipsey

himself,—for we have in him a man of mark, a man who has made himself, and

has done it well. His life-long devotion to literary pursuits has

never been allowed to interfere with the proper discharge of his daily

duties. Whilst still a working pitman he was master of his craft,

and it took an exceptionally good man to match him as a hewer of coal.

When, after many long years of patient toil, he won his way to an official

position, he gained the respect of those above him in authority whilst

retaining the confidence and affection of the men. Simple, straight,

and upright, he has held his own wherever lie has been placed. Since

he left the mine he has, among other things, edited as well as written

several of the introductory biographies and critical notices of the

Canterbury Poets Series for Mr. Walter Scott.

For such work he has peculiar qualifications. He has

read much and has thought carefully; he has gone to the works themselves,

and has formed his conclusions upon them for himself; and his critical

judgments have a freshness and a value which are all their own. Few

men have a more thorough knowledge of our literature from the Elizabethan

period downwards; and by patient and diligent study of their best work, in

various translations, he has gained an intimate acquaintance with several

of the greatest writers of the Continent. It is an intellectual

treat to hear our pitman-poet discuss such questions as the comparative

merits of the "Jew of Malta" and "Shylock," the necessity of the second

part of "Faust," or the comparative value amongst poets of Wordsworth and

Shelley, with men of high and acknowledged literary position and

attainments, and more than hold his own.

It is not for me to enter upon a criticism of my friend's

poems, but I may perhaps be allowed to say that one great merit of many of

them lies in the fact that in them he is dealing with the most vivid

aspects of that strange, uncertain, hazardous, and interesting calling

with which he is practically familiar. He speaks in them as only one

who knows can speak,—straight from the heart to the heart. Take the

two verses named, "Get Up." How simple, strong, and true they

are—not a word which could be spared nor a word too few; and yet as

suggestive, as picturesque, as full of food for much thought, as any two

verses you will find, no matter who the singer. The life of the

miner is one of peril; he lives with his own and the lives of those dear

to him constantly in his hand; and Joseph Skipsey has had bitter and

painful experience of the cruel sorrows to which he is exposed.

He is personally known to not a few of the men whom, in

letters and art, England delights to honour, and I think I may truly say

that he is "honoured of them all." Perhaps, if we could see things

as they really are, Joseph Skipsey is the best product of the coal-fields

since George Stephenson held his safety-lamp in the blower at Killingworth

pit.

R. SPENCE

WATSON.

January 1886. |

――――♦――――

|

3. PALL MALL GAZETTE

11th July, 1889.

A POET FROM THE MINES.

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOSEPH

SKIPSEY.

I PASSED through

the old pit Village of Percy Main an my way to visit Joseph Skipsey,

at Newcastle. It is now a pit village no longer, but a

populous suburb of North-Shields, inhabited by railway men, and

"trimmers" from the docks, and workmen from the shipbuilding yards.

There is one row of pit cottages still remaining—houses with perhaps

two rooms and a garret, with a long slope of brown-tiled roof, and

with small, trimly kept gardens in the rear. In one or other

of these cottages was born Mr. Thomas Burt, the member of Parliament

for the borough of Morpeth, and Mr. Joseph Skipsey, miner and poet,

who before this article appears in print will have been duly

installed as the custodian of Shakespeare's birth place.

Mr. Skipsey is a well-built, kindly-looking, grave-eyed man,

with a head reminding one first of Tennyson and then of Dante

Rossetti. A true Northumbrian, one who has seen little of the

world outside his native county, Mr. Skipsey's speech has scarcely a

trace of that famous "burr" which both Mr. Burt and Mr. Joseph Cowen

have failed to conquer.

"I want you to tell me," I said to him, "all about your early

life, and your means of education, and how you were led to the

writing of verse"—"I had no means of education to speak of," Mr.

Skipsey replied. "I was born on St. Patrick's Day, 1832.

Before I was seven years of age there was a colliery strike,

accompanied by rioting. My father was one of the leading men

among the miners, and endeavoured to make peace between the rioters

and the constables. While he was in the act of speaking to a

policeman he was shot dead, and my mother was left with eight

children, of whom I was the youngest. Then I went into the

mines. I was only seven years of age, but even such little

weekly sum as I could earn was of importance to a family like ours.

I became a trapper boy —that is to say, I sat all day by a door used

for the ventilation of one of the passages of the mine, opening it

and closing it as the trams and rellics went through. That was

when I taught myself to write. Mostly I sat in the darkness of

the mine, but sometimes I had a piece of candle, which I stuck

against the wall with a bit of clay. At such happy seasons I

amused myself by drawing figures upon the trap-door and by trying to

write words. I learned the alphabet, and the a, b, ab, before

going in to the pit. I learned to read on Sundays. This

was not at Sunday school, but in our own garret. My mother was

too poor to buy Sunday clothes for me, and I didn't like to go out

without them, so I sat in the garret and read. I found a few

books of my father's there. There was the Bible, of course,

and at ten years of age I must have known it all through. That

was my schooling, then; learning to read in the garret and to write

on the trap-door in the pit."

"And how was your love of poetry awakened?"—"In those days I

didn't know that there was such a thing as poetry; but the elder

boys in the pit, the putter lads, as they were called, had a habit

of ballad singing. It was seldom that they knew a ballad all

through, but they used to sing snatches of ballads and songs at

their work, and these fastened themselves in my memory. Their

incompleteness dissatisfied me. I wanted them all, and as I

could not obtain them, I used to fill them out here and there, and

piece the fragments together, and so give them a completeness of my

own. This patching of old ballads was my first effort at verse

making."

"And the next step?"—"Well, the next step was the composition

of new words to the old tunes. I do not doubt at this day that

the lilt of the old ballads has given a tone to whatever music my

verse may be supposed to possess. There was, I think, more

love for ancient ballad poetry in those days than there is now."

"But you have been a great reader. When did you make

your way to more books than were to be found in the garret?"—"In my

fifteenth year I found that an uncle of mine had a small library.

I borrowed 'Paradise Lost'. They laughed at me when I took it

away. 'Why, Joe,' said my aunt, 'thoul'll nivvor be able to

understand that.' 'Well,' I said, 'I mean to try.' The

book was a new revelation to me. I was entranced by it.

I thought of nothing else night or day, and I believe I accepted the

book as a narrative of fact. My enthusiasm induced my uncle to

open his whole book-case to me. In this way I came across

Pope's 'Iliad' and Lindley Murray's Grammar. The grammar was a

great service to one in my situation, as you may believe."

"But how did you come to feel your grammatical

deficiencies?"—"I don't believe that I did feel them. One can

scarcely explain these things; it is too far off now; but I must

have convinced myself that there was a right way of writing and a

wrong one, and that this grammar was intended to teach the right

way. It somehow seemed necessary to learn."

"And when your uncle's books were exhausted how did you get

more?"—"I had made the acquaintance of a man named Turner, a

bookseller in Newcastle. One day he said, 'Joe, did you ever

read Shakespeare? I had never heard of him, and 'Paradise

Lost' I had read more as a fact than as a work of art. Turner

pressed Shakespeare upon me. He had a copy, for which he

wanted five shillings. I was then seventeen. All my

earnings were given to my mother, except a shilling a fortnight.

I saved up for ten weeks, and then took Shakespeare home. The

book altered the aspect of the world to me. Whole passages

rang in my mind. I used to recite them to the other lads in

the pit, and I was half crazed for the stage, though I had never so

much as seen a theatre."

"And in what order did you read Shakspeare's plays?" "I

began with the 'Tempest' and read right through. I think the

comedies and histories fascinated me most. It was from

Shakespeare that I obtained my chief knowledge of English history.

In fact I may almost say that now. There was another work that

was very useful to me, in a different way. Chambers'

'Information for the People' was coming out in penny numbers.

That suited my pocket very well, and I bought the whole set. I

bought Joyce's 'Scientific Dialogues' too, and the works of Thomas

Dick, the 'Christian Philosopher,' and Chalmer's 'Political

Economy.' Chalmers enlarged my views on questions of wages and

labour. He steadied my mind, made me weigh matters carefully,

gave me a dislike to strikes, and so kept me out of the movements of

that time. There were then no such men among the miners as

Thomas Burt and William Crawford. I knew Mr. Burt as a boy.

We were at Seaton Delaval together. We were never very intimate, for

I had no great intimacies; but though he was younger than myself I

respected him greatly, and I think that he liked me."

"And to come back to your writing and reading, Mr.

Skipsey."—"Well, at twenty I came across Emerson's 'Essays,' and

this was another great awakening, and sustaining force. Just

before this I began to note down some of the verses that I had made.

And here I ought to explain that I never wrote anything with a view

to publication. I made verses because it seemed a natural and

was a delightful thing to do. Sometimes a thing would be

months in shaping itself in my mind. I would write it out when

I got the opportunity. But I never sat down with any

deliberate intention of writing poetry. Writing was merely a

transcription of what had taken shape already. Many of my

smaller pieces were composed as I was walking to the pit, and some

of these these have been praised as among the best that I have

written. At twenty one I found that I had as many pieces as

would make a book, but after reading them over I put almost the

whole of them into the fire. Three or four songs were saved,

and are now to be found in my books. I have been told that

they were worth saving. One of them greatly took Dante

Rossetti's fancy afterwards."

"Did you read your verses to your mates in the pit?"—"No; I

had just one friend, now a well-known artist in Australia. One

day he said to me, 'Joe, I am going to take some of these verses

away.' He took them to Archdeacon Prest, at Gateshead, who

asked if there were any more, and wished to see the author. He

was the first educated man I had met. The verses were brought

out it a small pamphlet shortly afterwards. The late James

Clephan wrote a long article about them, and this made me known to

the public. Somebody asked one of the men at the pit if he had

known that I made rhymes. No, he said, he had worked beside me

ten years, and he knew nothing about it; but he knew I was a good

hewer."

"You were constantly at work, I suppose?"—"I used to go down

the pit at four in the morning. We sometimes came up at four

in the afternoon, but more frequently at six. In winter we

never saw daylight except on the Sundays. That may be the

reason why my verses do not contain more descriptions of natural

scenery. When I saw the outer world I usually saw the skies

with the stars in them."

"But you did leave the pit for a while?"—"Yes. After I

had published my second book of verses, in 1873 I was offered

employment at the Gateshead Iron Works, and I accepted it.

Still later I became assistant librarian to the Newcastle Literary

and Philosophical Society; but, unfortunately, what I earned was not

sufficient for the maintenance of my family, and I again went back

to the mine. I became deputy-overman, and then master-shifter.

This last was a position of great responsibility, for it was part of

my duty to see that the mine was in a state of safety. My

'Book of Lyrics' was published in 1878. This attracted Dante

Rossetti's notice, and he wrote to me, asking me to go up to London.

Theodore Watts reviewed the book very favourably in the Athenæum,

and when I did visit Rossetti I found that I had already a great

number of friends, with William Morris, and Burne-Jones, and William

Bell Scott among them. Rossetti was very kind, and it was to

me that his very last letter was written. There is little more

that I need tell you, except of my delight in becoming the custodian

of Shakspeare's birthplace. The secretary, Mr. Savage, and

myself, hope to make some discoveries. Mr. Savage has

found—what do you suppose?—the name of Nicholas Bottom in an old

Stratford register. I wonder what Mr. Donnelly would make of

that!" and here Mr. Skipsey, with a pleased light on his face, fell

to dreaming of Stratford and of Shakspeare. The duties of the

new post will not be altogether strange to him. For some years

he and Mrs. Skipsey, a bright, pleasant woman, gentle-looking, were

caretakers at a Board school in Newcastle, and more recently they

have occupied similar positions at the new College of Science, in

the same city. These are strange uses to which to put a poet.

Even King Admetus did better to him who "stretched some chords, and

drew music that made men's bosoms swell." And what did King

Admetus?

|

—Well pleased with being soothed

Into a sweet half-sleep,

Three times his kingly beard he smoothed,

And made him viceroy o'er his sheep. |

|

|