|

|

|

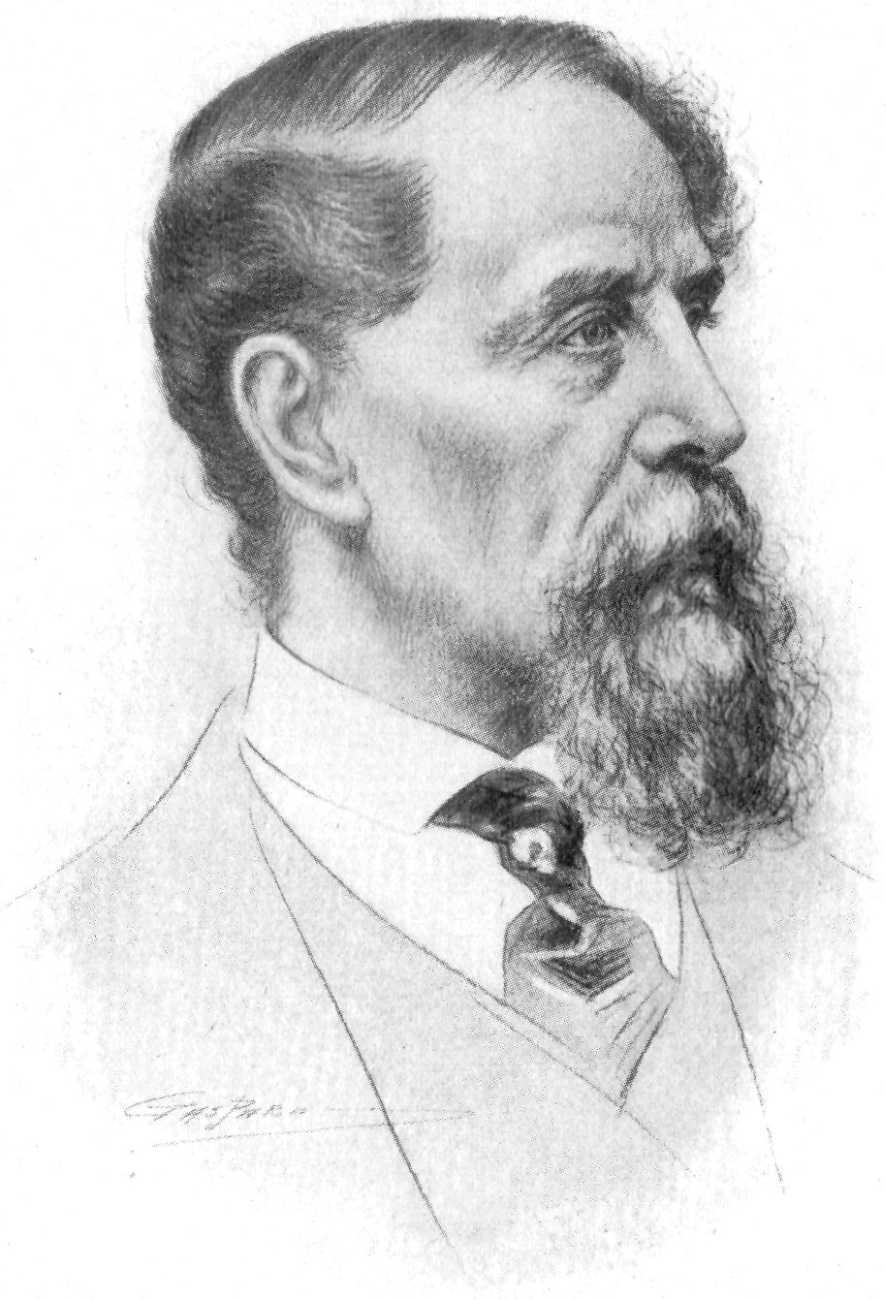

Charles Dickens

1812 - 1870 |

CHARLES DICKENS.

――♦――

AN INTRODUCTION

TO

LEGENDS AND LYRICS

BY

ADELAIDE ANNE PROCTER.

IN the spring of the year 1853, I observed, as

conductor of the weekly journal Household Words, a short poem among

the proffered contributions, very different, as I thought, from the shoal

of verses perpetually setting through the office of such a periodical, and

possessing much more merit. Its authoress was quite unknown to me.

She was one Miss Mary Berwick, whom I had never heard of; and she was to

be addressed by letter, if addressed at all, at a circulating library in

the western district of London. Through this channel, Miss Berwick

was informed that her poem was accepted, and was invited to send another.

She complied, and became a regular and frequent contributor. Many

letters passed between the journal and Miss Berwick, but Miss Berwick

herself was never seen.

How we came gradually to establish, at the office of Household Words,

that we knew all about Miss Berwick, I have never discovered. But we

settled somehow, to our complete satisfaction, that she was governess in a

family; that she went to Italy in that capacity, and returned; and that

she had long been in the same family. We really knew nothing

whatever of her, except that she was remarkably business-like, punctual,

self-reliant, and reliable: so I suppose we insensibly invented the rest.

For myself, my mother was not a more real personage to me, than Miss

Berwick the governess became.

This went on until December, 1854, when the Christmas number,

entitled The Seven Poor Travellers, was sent to press. Happening to

be going to dine that day with an old and dear friend, distinguished in

literature as Barry Cornwall, I took with me an early proof of that

number, and remarked, as I laid it on the drawing-room table, that it

contained a very pretty poem, written by a certain Miss Berwick.

Next day brought me the disclosure that I had so spoken of the poem to the

mother of its writer, in its writer's presence; that I had no such

correspondent in existence as Miss Berwick; and that the name had been

assumed by Barry Cornwall's eldest daughter, Miss Adelaide Anne Procter.

The anecdote I have here noted down, besides serving to

explain why the parents of the late Miss Procter have looked to me for

these poor words of remembrance of their lamented child, strikingly

illustrates the honesty, independence, and quiet dignity, of the lady's

character. I had known her when she was very young; I had been

honoured with her father's friendship when I was myself a young aspirant;

and she had said at home, "If I send him, in my own name, verses that he

does not honestly like, either it will be very painful to him to return

them, or he will print them for papa's sake, and not for their own.

So I have made up my mind to take my chance fairly with the unknown

volunteers."

Perhaps it requires an editor's experience of the profoundly

unreasonable grounds on which he is often urged to accept unsuitable

articles—such as having been to school with the writer's husband's

brother-in-law, or having lent an alpenstock in Switzerland to the

writer's wife's nephew, when that interesting stranger had broken his

own—fully to appreciate the delicacy and the self-respect of this

resolution.

Some verses by Miss Procter had been published in the Book

of Beauty, ten years before she became Miss Berwick. With the

exception of two poems in the Cornhill Magazine, two in Good

Words, and others in a little book called A Chaplet of Verses

(issued in 1862 for the benefit of a Night Refuge), her published writings

first appeared in Household Words, or All the Year Round.

The present edition contains the whole of her Legends and Lyrics,

and originates in the great favour with which they have been received by

the public.

Miss Procter was born in Bedford Square, London, on the 30th

of October, 1825. Her love of poetry was conspicuous at so early an

age, that I have before me a tiny album made of small note-paper, into

which her favourite passages were copied for her by her mother's hand

before she herself could write. It looks as if she had carried it

about, as another little girl might have carried a doll. She soon

displayed a remarkable memory, and great quickness of apprehension.

When she was quite a young child, she learned with facility several of the

problems of Euclid. As she grew older, she acquired the French,

Italian, and German languages; became a clever pianoforte player; and

showed a true taste and sentiment in drawing. But, as soon as she

had completely vanquished the difficulties of any one branch of study, it

was her way to lose interest in it, and pass to another. While her

mental resources were being trained, it was not at all suspected in her

family that she had any gift of authorship, or any ambition to become a

writer. Her father had no idea of her having ever attempted to turn

a rhyme, until her first little poem saw the light in print.

When she attained to womanhood, she had read an extraordinary

number of books, and throughout her life she was always largely adding to

the number. In 1853 she went to Turin and its neighbourhood, on a

visit to her aunt, a Roman Catholic lady. As Miss Procter had

herself professed the Roman Catholic Faith two years before, she entered

with the greater ardour on the study of the Piedmontese dialect, and the

observation of the habits and manners of the peasantry. In the

former, she soon became a proficient. On the latter head, I extract

from her familiar letters written home to England at the time, two

pleasant pieces of description.

A BETROTHAL.

"We have been to a ball, of which I must

give you a description. Last Tuesday we had just done dinner at

about seven, and stepped out into the balcony to look at the remains of

the sunset behind the mountains, when we heard very distinctly a band of

music, which rather excited my astonishment, as a solitary organ is the

utmost that toils up here. I went out of the room for a few minutes,

and, on my returning, Emily said, 'Oh! That band is playing at the

farmer's near here. The daughter is fiancée

to-day, and they have a ball.' I said, 'I wish I was going!'

'Well,' replied she, 'the farmer's wife did call to invite us.'

'Then I shall certainly go,' I exclaimed. I applied to Madame B.,

who said she would like it very much, and we had better go, children and

all. Some of the servants were already gone. We rushed away to

put on some shawls, and put off any shred of black we might have about us

(as the people would have been quite annoyed if we had appeared on such an

occasion with any black), and we started. When we reached the

farmer's, which is a stone's throw above our house, we were received with

great enthusiasm; the only drawback being, that no one spoke French, and

we did not yet speak Piedmontese. We were placed on a bench against

the wall, and the people went on dancing. The room was a large

whitewashed kitchen (I suppose), with several large pictures in black

frames, and very smoky. I distinguished the Martyrdom of Saint

Sebastian, and the others appeared equally lively and appropriate

subjects. Whether they were Old Masters or not, and if so, by whom,

I could not ascertain. The band were seated opposite us. Five

men, with wind instruments, part of the band of the National Guard, to

which the farmer's sons belong. They played really admirably, and I

began to be afraid that some idea of our dignity would prevent me getting

a partner; so, by Madame B.'s advice, I went up to the bride, and offered

to dance with her. Such a handsome young woman! Like one of

Uwins's pictures. Very dark, with a quantity of black hair, and on

an immense scale. The children were already dancing, as well as the

maids. After we came to an end of our dance, which was what they

called a Polka-Mazourka, I saw the bride trying to screw up the courage of

her fiancée to ask me to dance,

which after a little hesitation he did. And admirably he danced, as

indeed they all did—in excellent time, and with a little more spirit than

one sees in a ball-room. In fact, they were very like one's ordinary

partners, except that they wore earrings and were in their shirt- sleeves,

and truth compels me to state that they decidedly smelt of garlic.

Some of them had been smoking, but threw away their cigars when we came

in. The only thing that did not look cheerful was, that the room was

only lighted by two or three oil-lamps, and that there seemed to be no

preparation for refreshments. Madame B., seeing this, whispered to

her maid, who disengaged herself from her partner, and ran off to the

house; she and the kitchenmaid presently returning with a large tray

covered with all kinds of cakes (of which we are great consumers and

always have a stock), and a large hamper full of bottles of wine, with

coffee and sugar. This seemed all very acceptable. The

fiancée was requested to distribute

the eatables, and a bucket of water being produced to wash the glasses in,

the wine disappeared very quickly—as fast as they could open the bottles.

But, elated, I suppose, by this, the floor was sprinkled with water, and

the musicians played a Monferrino, which is a Piedmontese dance.

Madame B. danced with the farmer's son, and Emily with another

distinguished member of the company. It was very

fatiguing—something like a Scotch reel. My partner was a little

man, like Perrot, and very proud of his dancing. He cut in the air

and twisted about, until I was out of breath, though my attempts to

imitate him were feeble in the extreme. At last, after seven or

eight dances, I was obliged to sit down. We stayed till nine, and I

was so dead beat with the heat that I could hardly crawl about the house,

and in an agony with the cramp, it is so long since I have danced."

A MARRIAGE.

"The wedding of the farmer's daughter has taken place.

We had hoped it would have been in the little chapel of our house, but it

seems some special permission was necessary, and they applied for it too

late. They all said, "This is the Constitution. There would

have been no difficulty before!" the lower classes making the poor

Constitution the scapegoat for everything they don't like. So as it

was impossible for us to climb up to the church where the wedding was to

be, we contented ourselves with seeing the procession pass. It was

not a very large one, for, it requiring some activity to go up, all the

old people remained at home. It is not etiquette for the bride's

mother to go, and no unmarried woman can go to a wedding—I suppose for

fear of its making her discontented with her own position. The

procession stopped at our door, for the bride to receive our

congratulations. She was dressed in a shot silk, with a yellow

handkerchief, and rows of a large gold chain. In the afternoon they

sent to request us to go there. On our arrival we found them dancing

out of doors, and a most melancholy affair it was. All the bride's

sisters were not to be recognised, they had cried so. The mother sat

in the house, and could not appear. And the bride was sobbing so,

she could hardly stand! The most melancholy spectacle of all to my

mind was, that the bridegroom was decidedly tipsy. He seemed rather

affronted at all the distress. We danced a Monferrino; I with the

bridegroom; and the bride crying the whole time. The company did

their utmost to enliven her by firing pistols, but without success, and at

last they began a series of yells, which reminded me of a set of savages.

But even this delicate method of consolation failed, and the wishing

good-bye began. It was altogether so melancholy an affair that

Madame B. dropped a few tears, and I was very near it, particularly when

the poor mother came out to see the last of her daughter, who was finally

dragged off between her brother and uncle, with a last explosion of

pistols. As she lives quite near, makes an excellent match, and is

one of nine children, it really was a most desirable marriage, in spite of

all the show of distress. Albert was so discomfited by it, that he

forgot to kiss the bride as he had intended to do, and therefore went to

call upon her yesterday, and found her very smiling in her new house, and

supplied the omission. The cook came home from the wedding,

declaring she was cured of any wish to marry—but I would not recommend

any man to act upon that threat and make her an offer. In a couple

of days we had some rolls of the bride's first baking, which they call Madonnas. The musicians, it seems, were in the same state as the

bridegroom, for, in escorting her home, they all fell down in the mud.

My wrath against the bridegroom is somewhat calmed by finding that it is

considered bad luck if he does not get tipsy at his wedding."

Those readers of Miss Procter's poems who should suppose from

their tone that her mind was of a gloomy or despondent cast, would be

curiously mistaken. She was exceedingly humorous, and had a great

delight in humour. Cheerfulness was habitual with her, she was very

ready at a sally or a reply, and in her laugh (as I remember well) there

was an unusual vivacity, enjoyment, and sense of drollery. She was

perfectly unconstrained and unaffected: as modestly silent about her

productions, as she was generous with their pecuniary results. She

was a friend who inspired the strongest attachments; she was a finely

sympathetic woman, with a great accordant heart and a sterling noble

nature. No claim can be set up for her, thank God, to the possession

of any of the conventional poetical qualities. She never by any

means held the opinion that she was among the greatest of human beings;

she never suspected the existence of a conspiracy on the part of mankind

against her; she never recognised in her best friends, her worst enemies;

she never cultivated the luxury of being misunderstood and unappreciated;

she would far rather have died without seeing a line of her composition in

print, than that I should have maundered about her, here, as "the Poet",

or "the Poetess".

With the recollection of Miss Procter as a mere child and as

a woman, fresh upon me, it is natural that I should linger on my way to

the close of this brief record, avoiding its end. But, even as the

close came upon her, so must it come here.

Always impelled by an intense conviction that her life must

not be dreamed away, and that her indulgence in her favourite pursuits

must be balanced by action in the real world around her, she was

indefatigable in her endeavours to do some good. Naturally

enthusiastic, and conscientiously impressed with a deep sense of her

Christian duty to her neighbour, she devoted herself to a variety of

benevolent objects. Now, it was the visitation of the sick, that had

possession of her; now, it was the sheltering of the houseless; now, it

was the elementary teaching of the densely ignorant; now, it was the

raising up of those who had wandered and got trodden under foot; now, it

was the wider employment of her own sex in the general business of life;

now, it was all these things at once. Perfectly unselfish, swift to

sympathise and eager to relieve, she wrought at such designs with a

flushed earnestness that disregarded season, weather, time of day or

night, food, rest. Under such a hurry of the spirits, and such

incessant occupation, the strongest constitution will commonly go down.

Hers, neither of the strongest nor the weakest, yielded to the burden, and

began to sink.

To have saved her life, then, by taking action on the warning

that shone in her eyes and sounded in her voice, would have been

impossible, without changing her nature. As long as the power of

moving about in the old way was left to her, she must exercise it, or be

killed by the restraint. And so the time came when she could move

about no longer, and took to her bed.

All the restlessness gone then, and all the sweet patience of

her natural disposition purified by the resignation of her soul, she lay

upon her bed through the whole round of changes of the seasons. She

lay upon her bed through fifteen months. In all that time, her old

cheerfulness never quitted her. In all that time, not an impatient

or a querulous minute can be remembered.

At length, at midnight on the second of February, 1864, she

turned down a leaf of a little book she was reading, and shut it up.

The ministering hand that had copied the verses into the tiny

album was soon around her neck, and she quietly asked, as the clock was on

the stroke of one:

"Do you think I am dying, mamma?"

"I think you are very, very ill to-night, my dear!"

"Send for my sister. My feet are so cold. Lift me

up?"

Her sister entering as they raised her, she said: "It

has come at last!" And with a bright and happy smile, looked upward,

and departed.

Well had she written:

|

Why shouldst thou fear the beautiful angel, Death,

Who waits thee at the portals of the skies,

Ready to kiss away thy struggling breath,

Ready with gentle hand to close thine eyes?

Oh what were life, if life were all? Thine eyes

Are blinded by their tears, or thou wouldst see

Thy treasures wait thee in the far-off skies,

And Death, thy friend, will give them all to thee.

________________________________

|

|

|

|

|

Bessie Rayner Belloc

1829-1925 |

THE PARENTS OF ADELAIDE PROCTER.

FROM

"In a Walled Garden"

BY

BESSIE RAYNER BELLOC

(née PARKES)

The father and

mother of Adelaide Procter were both highly gifted, and their household

was known to so many surviving friends, that it is only fitting their

names should precede her own, although she achieved a greater fame; yet

there were years when "Barry Cornwall " was known to all, and when his

songs were sung all over England. Two of them, "The sea, the sea,

the open sea," and the "Return of the Admiral," have their permanent

place, though many of his charming and poetic pages have sunk into

comparative oblivion. In his own person he was a refined and

somewhat silent man, with a head said to resemble Sir Walter Scott's in

miniature, and he was extremely beloved by the literary world. But

he lived an interior life, into which, I think, none but his wife ever

penetrated. He was profoundly attached to her, and she was for ever

shielding him from the wind that blew too roughly. He had many

sorrows, and death twice visited his household under most pathetic

circumstances. To ward off blows from "Brian" and to sustain him

with her own abundant strength, was Mrs. Procter's constant care, and in

this she showed a side of her character wholly unsuspected by the outer

world.

Mr. Procter was born so long ago as 1787, and was not far

from forty when he married the lovely girl, Anne Skepper, who had been

brought up in the home of her stepfather, Basil Montagu. Bryan

Walter Procter came from the North of England. He was educated at

Harrow, and spent his holidays at the house of a great-uncle who lived

about a dozen miles from London; and his first real instructress in

literature was a female servant, born in a better station of life, who had

read Richardson and Fielding and worshipped Shakespeare. She used to

recite whole scenes to the boy, and encouraged him to buy a Shakespeare of

his own. "But," says he, "I had not leisure to study and worship my

Shakespeare long, for at the end of a month or six weeks my destiny drove

me back to school." There he had two schoolfellows, boys named

Robert Peel and George Gordon Byron. Of Byron, Mr. Procter says that

he then showed no signs of poetic grace. "He was loud, even coarse,

and very capable of a boy's vulgar enjoyments. He played at hockey

and racquets, and was occasionally engaged in pugilistic encounters."

Of himself he says he was neither very short nor very tall, neither

handsome nor hideous. He survived Byron for fifty years, seeing the

dawn, the zenith, and the partial oblivion of his fame.

Among Mr. Procter's poems should be especially noticed the

fine ring of Belshazzar, and some of deep and tender domestic interest.

The lovely lines to his wife, beginning—

|

"How many years, my Dove,

Hast thou been mine!

How many years, my Love,

Have I been thine!" |

and the

exquisite tribute to his dead boy, called "The Little Voice," are among

the most poignant utterances of the human heart. But nothing in his

gentle, reserved face betrayed in later life the interior fire.

He led a hard-working life in London as a barrister, and

later in a Government office. In looking through the memoir published in

his widow's lifetime, I was chiefly struck by a letter in which he

describes his study, and says, regretfully, that he has never been abroad,

never seen Italy or France, he, the poet and the lover of Italian art; and

by another letter about the Indian Mutiny, in which "Our son (the only son

I have, indeed) escaped from Delhi." He tells how this young man,

left to him after the death of his eldest boy Edward, had been in Delhi,

and how he and four or five other officers, four women, and a child,

escaped. The men were "obliged to drop the women a fearful height

from the walls of the fort amidst showers of bullets. They were

seven days and seven nights in the jungle without money or meat, scarcely

any clothes, no shoes. They forded rivers, lay on the wet ground at

night, lapped water from the puddles, and finally reached Meerut."

Montagu Procter married some years later the youngest of the

ladies here spoken of. At the time of the Mutiny she was a girl of

fifteen. He became eventually a general, and, returning to England,

survived his father, but predeceased his mother, who, indeed, lost

successively all her children save two.

Of Mrs. Procter much will inevitably be written in future

years. She was a very remarkable person, and lived in possession of

almost unbroken health and faculties until nearly ninety. As a girl

("my dearest girl," writes the poet during his betrothal) she had been

extremely pretty. She was an early playmate of my mother's, but my

memory of her dates from her middle age, and extends over nearly fifty

years. She was the daughter by a first marriage of Mrs. Basil

Montagu, and always spoke of her mother with the greatest reverence.

But of the race of poets to which she was inextricably bound, she spoke

with a half-laughing satire. One was evidently her life-long lover,

and one was her child, and several others clustered about her like bees.

She did not exactly hold a salon; there was no great fortune in the

household, nor any sort of pretension whatever, and Mrs. Procter gave one

the impression of having her hands very full; but everybody of any

literary pretension whatever seemed to flow in and out of the house.

The Kembles, the Macreadys, the Rossettis, the Dickens, the Thackerays,

never seemed to be exactly visitors, but to belong to the place.

Three of the daughters became Catholic, and Mrs. Procter, who, I imagine,

did not dwell much on the next world, stood between them and the sensitive

father, to whom the loss of close union was a great misery. I used

to think it infinitely touching to see Mrs. Procter trying to harmonize

the household. If "Brian" could be kept cheerful, and if nobody was

ill (and, alas! somebody was very often ill), then the quick vivid mother

of the family seemed content. She had a habit of going into the

world, a habit of dressing fashionably, a habit of writing the neatest and

most concise notes possible; but her consistent, steady kindness had

assuredly some deep spiritual root, of which she never spoke. Like

her mother; she never abdicated for a moment her great tenue, never

kept her room, never lowered the scale of her dress, never lost her

composure; I should doubt if in sixty years a meal had ever been placed

upon the table which she had not herself ordered. It was my fate to

be very closely associated with her under circumstances in which

ninety-nine people out of a hundred would have broken down, and yet when

she lost her daughters, it was their friend whom she tried to spare.

I particularly remember her taking me with her to the Catholic cemetery in

Kensal Green to plant a quantity of ivy on Adelaide's grave. I can

see her kneeling at the headstone, twisting the sprays, with a face of

anxious, steady determination. That grave is now a place of

pilgrimage to American and Colonial travellers. It is thickly

overgrown with ivy, but nobody guesses that the mother planted it herself.

Many years afterwards, Edythe Procter died very

suddenly—indeed, in a manner truly tragical—failure of the heart's

action. Mrs. Procter was then more than eighty; and before the

announcement could traverse the Continent in the newspapers, came a

careful letter, addressed to a delicate friend at Mentone, and on the

corner of the envelope two tiny, neatly-written words, "Bad News:"

Such were the environments of Adelaide Procter's life—a

short life, for she died at the age of thirty-eight. Of outward incidents,

apart from the sudden blossoming of her literary fame, there were scarcely

any. The year spent in Italy, where her aunt, Madame de Viry, was

attached to the Court circle at Turin, was certainly a determining

influence on her life. Emily de Viry had become a devout Catholic,

and at that time the saintly wife of Victor Emmanuel was living. The

example impressed Adelaide's mind, and doubtless contributed to her

religious change. At Aix-les-Bains is a large portrait en pied of

the young Queen of Sardinia in her bridal dress. It looks, at first

sight, to be a purely conventional picture, but the eyes are of a haunting

depth. They recall a word-picture of the Queen returning from Holy

Communion, which Adelaide Procter gave. The wife of Victor Emmanuel

was passing along one of the galleries of the Palace, her face "shining as

with an interior lamp," when she was met by the young English girl, who

never forgot the sight. Of this association Adelaide Procter always

bore the trace. In her religious attitude she resembled a foreign rather

than an English Catholic. She looked like a Frenchwoman mounting the

steps of the Madeleine, or a veiled Italian in St. Peter's. The one

thing she never mentioned was her own conversion.

One of Miss Procter's sisters, named Agnes, joined the order

of the Irish Sisters of Mercy; and in looking back to our childhood I best

remember her, as the nearer to my own age.

In 1840 the Procters lived in St. John's Wood, and used to

visit their grandparents in Storey's Gate; and in this house it must have

been that two children were sitting by the fireside one evening.

There was no other light in the room, and Agnes Procter (Sister Mary

Francis) suddenly made a confidence; saying, in a tone of intense childish

conviction, "I do love mama." These words made an ineffaceable

impression on the hearer, for the little speaker was never supposed to be

at all imaginative, and certainly Mrs. Procter did not pose before the

world as a tender woman—rather the reverse—though her intimates knew her

for a very good and kind one. And the last time that I saw Sister

Mary Francis she was kneeling by that mother's open grave at Kensal Green,

her sincere, gentle face, under its veil, looking but little changed since

the day of her profession some thirty years before. It may not be

irrelevant to add that shortly after her somewhat unexpected death after a

few days' illness, the Reverend Mother spoke of Sister Mary Francis' great

and unusual affection for her mother as of a profound sentiment rarely

noticed either in or out of the religious life. It was the sweet

soul's one earthly romance. I do not know in what light Mrs.

Procter's memory will go down to posterity when the letters and memoirs of

the generation in which she played so large a social part come to be

written and published; but this image of her as enshrined in her

daughter's heart should be recorded, for it is true.

|

|

|

Adelaide, from a painting by

Emma Gaggiotti Richards |

Of the gifted eldest daughter the mother was intensely proud, and well may

she have been, for a more vital spirit never inhabited a finely wrought

frame. Adelaide Anne Procter was so curiously unlike her poems, and

yet so distinct in individuality, that it is a pity she was not painted by

any artist capable of rendering her singular and interesting face.

There was something of Dante in the contour of its thin lines, and the

colouring was a pale, delicate brown, which harmonized with the darker

hair, while the eyes were blue, less intense in hue than those of Shelley;

and like his also was the exquisitely fine, fluffy hair, which when

ruffled stood out in a halo round the brow. A large oil painting of

her exists, done, I believe, by Emma Galiotti, and it is like her as she

appeared in a conventional dress and a most lugubrious mood, but the real

woman was quite different. She had a forecast of the angel in her

face and figure, but it was of the Archangel Michael that she made one

think. There was something spirited and almost militant in her

aspect, if such a word can be applied to one so exquisitely delicate and

frail. She was somewhat older than myself, and therefore, while I

remember Agnes as a little girl, my first distinct memory of Adelaide

dates from a period when she was already grown up, and had returned from

Turin.

In her manner and dress she bore all the marks of a very

exquisite breeding. She was conversant with foreign languages, knew French

and Italian well, and wrote a peculiarly clear and delicate hand.

One of her minor accomplishments was that of illumination. Monsignor

Gilbert possessed two excellent examples of her skill in this unusual art.

In her youth she danced lightly and well. All these little details

go to make up the portrait of a very charming personality.

She was already thirty before her name had been heard, except

as that of Barry Cornwall's "sweet, beloved First Born." Her poems

circulated among friends, just as Rossetti's used to do, being copied from

hand to hand. Then one was sent by her anonymously to Charles

Dickens, and inserted by him in a Christmas number of Household Words.

Dickens thus tells the story: "Happening one day to dine with an old and

dear friend, distinguished in literature as 'Barry Cornwall,' I took with

me an early proof of the Christmas number of Household Words, entitled

'The Seven Poor Travellers,' and remarked, as I laid it on the

drawing-room table, that it contained a very pretty poem, written by a

certain Miss Berwick. Next day brought me a disclosure that I had so

spoken of the poem to the mother of the writer in the writer's presence;

that I had no such correspondent in existence as Miss Berwick, and that

the name had been assumed by Barry Cornwall's daughter, Miss Adelaide Anne

Procter."

From this time forward, I forget the year, she continued to

write in Household Words, and the poems attracted so much attention

that people used to pretend they had written them. When they were at

length collected into a volume, with the writer's name attached, they

rushed into fame, and circulated all over the kingdom; and Miss Procter

received a pathetic appeal from a young lady, who asked her could it be

true that these lovely verses were all hers, for her lover had been in the

habit of assuring her, as each poem successively appeared, that it was his

own! Twelve editions followed one another, and five years after, the

demand for her poems was still "far in excess of that for the writings of

any living poet except Mr. Tennyson:" I think it caused her a feeling of

shyness amounting to pain to have so far outstripped her poet-father in

popular estimation. "Papa is a poet. I only write verses."

A very few years after this wide recognition of her genius

the end came. Her health began to fail in 1862, and by the end of

that year she was confined to her bed. So great was the fragility of

her frame, that when once the lungs were attacked there seemed to be no

chance of saving her. Then began a battle which the two or three

surviving people who witnessed it can assuredly never forget—a battle

royal with the power of Death. I do not mean that she consciously

tried to live a longer life, but that she did not give way an inch to the

Destroyer. The only time I ever saw her quail was one day when I got

a little pencil note, "They say the second lung is attacked." I

hurried off to the house, and found her sitting up in bed, her pretty fair

hair standing out in a halo, her blue eyes fastening on mine with an

anxious, wistful look. But the momentary panic passed away, and she

recovered her cheerfulness, repeated her prayers, talked of

Jean Ingelow's

poems (and particularly of the "High Tide in Lincolnshire"), made her

gentle jests—she was naturally extremely witty—and faced the Destroyer

with the most pathetic mixture of resignation and pluck imaginable.

At last, one day—it was the 1st of February, 1864 (Thackeray

had died on Christmas Eve)—I went to her in the evening, and found her

greatly oppressed. But she was very eager about a poem of mine, "Avignon,"

and would sit up in bed holding it in her slender, trembling hands, and

trying to correct the proof. The last line ran—

"Ora pro nobis, Sainte Marie."

The evening wore on—nine—ten—eleven o'clock. It was not possible for me

to remain later without greatly alarming my parents, and I had to leave.

After an anxious consultation with Edythe, I returned to the sick-room and

kissed her forehead, saying, "Good-night, dear." She looked up at me

quickly and gravely, and said, "Good-night." After I had left, they

sat beside her—the mother, the sister, and the maid who had been with

them very many years. About two in the morning of the Feast of the

Purification her breathing became oppressed. She looked up in her

mother's face, and said, "Mamma, has it come?" And Mrs.

Procter said, "Yes, my dear," and took her in her arms. And

so, while Edythe knelt by her side, reciting the prayers for the dying, my

dear Adelaide passed away in peace.

It remains to say a few words about her poems. Since

for years they had a larger sale than those of any other poet save

Tennyson, they must have penetrated into every reading household in Great

Britain. Of late, however, their popular fame seems chiefly to

repose on the "Lost Chord," nobly set to music by Sir Arthur Sullivan.

It is wonderful to see the enthusiasm infused by this song. The vast

audience of St. James's Hall thrills as one man when it is given.

But in the beauty of the narrative poems, and in the profound depth of

feeling of those which have an autobiographical source, the student of

Victorian literature will, I am convinced, find permanent delight; and

that many verses and many lines will survive may be inferred from that

perfection of form which is essential to lasting fame. Miss Procter

always used the plainest words to convey her thought, the simplest,

choicest words to express her feeling. Some of those which deal with

the human heart are wonderfully sweet and subtle.

One of the most striking of the personal poems is "A Woman's

Question," beginning—

"Before I trust my fate to thee."

And another, named "Beyond," of which the two last stanzas run thus:

If in my heart I now could fear that, risen

again, we

should not know

What was our Life of Life when here—the hearts we

loved so much below;

I would arise this very day, and cast so poor a thing

away.

But love is no such soulless clod ; living, perfected it shall

rise

Transfigured in the light of God, and giving glory to the

skies.

And that which makes this life so sweet shall render

Heaven's joy complete." |

Another delicately subtle poem is entitled "Returned—Missing," and how

strong and noble, is "A Parting." And lastly, the charming "Comforter."

"If you break your plaything yourself, dear,

Don't you cry for it all the same?

I don't think it is such a comfort,

One has only oneself to blame.

"People say things cannot be helped, dear,

But then that is the reason why ;

For if things could be helped or altered,

One would never sit down to cry." |

The more specially religious poems are to be found in a small volume

entitled "A Chaplet of Verses," published for the benefit of the Night

Refuge originally established close to the church in Moorfields. It

opens with the trumpet call of the "Army of the Lord," a splendid piece of

verse. But "Give me thy heart " is to be found in the first volume

of "Legends and Lyrics." Both of them are surely equal to any of

Father Faber's. What nobler prayer, more perfectly expressed, than

that contained in the eight lines:

"Send down, O Lord, Thy sacred fire!

Consume and cleanse the sin

That lingers still within its depths;

Let heavenly love begin.

That sacred flame Thy Saints have known,

Kindle, O Lord, in me!

Thou above all the rest for ever,

And all the rest in Thee." |

The "Chaplet" has been stereotyped, and has had a wide circulation. One

poem, entitled "Homeless,"* was written at Monsignor Gilbert's special

request, and was for years inserted in the annual report and appeal for

funds. Of the seven stanzas, I quote two. The concluding lines

of each exemplify the vigour with which Miss Procter rounded a thought

where weaker poets fail:—

"Why, our criminals all are sheltered,

They are pitied, and taught, and fed;

That is only a sister—woman,

Who has got neither food nor bed—

And the Night cries, 'Sin to be living,'

And the River cries, 'Sin to be dead.'"

*

* *

* *

*

"Nay; goods in our thrifty England

Are not left to lie and grow rotten;

For each man knows the market value

Of silk, or woollen, or cotton . . .

But in counting the riches of England,

I think our Poor are forgotten!" |

The profits

of this little book, of which the sale still continues, were so

considerable that Monsignor Gilbert founded a bed in the Refuge called the

"Adelaide Procter Bed," a permanent memento and reminder of prayer for her

soul.

And lastly, I have been told upon the highest authority that

her personal habits of piety were of the most fervent and consistent kind.

The intensity of her susceptible nature found expression and support in

her faith. She was strengthened in much suffering, and consoled in

much grief, by ardent love of God. She never failed in courage when

to publicly confess obedience to the Catholic Church demanded strength of

no usual sort, for her lot was cast among those who did not acknowledge

the claim; and she, who was eminently delicate in fibre and subject to

many fears, went down by slow degrees into the "valley of the shadow of

Death," with a cheerful heroism rarely seen.

It was on the 2nd of February, 1864, that Adelaide Procter's

wasted frame was laid within the coffin. The snow lay on the ground in

patches outside the old church in Spanish Place, full of the lighted

candles held by a dense congregation.

"And we know when the Purification,

Her first feast, comes round,

The early spring flowers to greet it

Just opening are found;

And pure, white, and spotless, the snowdrop

Will pierce the dark ground." |

So we laid

masses of snowdrops all about her, and for years the recurring sight of

them brought back the vision of that calm spiritual face amidst the

flowers. But of her, more than of others, it truly appeared that

only the frail worn envelope lay there. While on earth she had

habitually dwelt in the spiritual world; and into its inner depths, behind

the veil, the Lord, whom she so well loved, had led her, by a long and

painful path, so that it seemed to those who knew her as if by an almost

imperceptible vanishing she had been withdrawn from their eyes.

Edythe now lies in the same grave in the catholic Cemetery at Kensal

Green, and the names of their two sisters are folded in the ivy which

their mother planted there.

* Now that Monsignor Gilbert

has been withdrawn from our midst, there is no reason for refraining to

say that he, who was her confessor, and whom she certainly trusted above

all, read through this paper and ratified it with his approval. |

|