|

THE EDINBURGH NEWS,

SATURDAY, JULY 28, 1855.

TENNYSON'S NEW VOLUME OF POEMS.

BY

GERALD MASSEY. |

|

Maud and other poems. By Alfred Tennyson, Poet Laureate, D.L.C. London, Moxon.

|

|

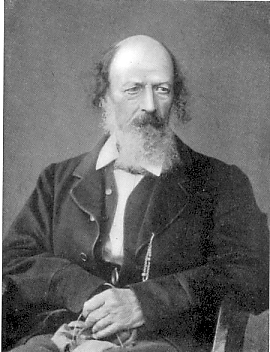

Alfred Tennyson

(1809-92) |

One of the things which present themselves to us early in life is the fact that events seldom come about as we have imagined they would. The fulfilment may be for better or for worse, but anticipation is not often realised according to our pattern. We draw upon the future confidently as though we had the power to shape it, while truly we

know not what a day may bring forth, and then forsooth we are disappointed that he event of circumstance

should come in such a questionable shape, and not wearing the livery of our dreams as lacquey* to on will. It is even so in the workings of genius. It seldom or never fulfils itself after the manner you had fashioned for it, or according to the thing you had predicated of it. If it be truly creative, you can never prophecy of the fruit of its future by the promise of its past,

for genius is an endless series of delightsome surprises, and it always returns back from the infinite in which it voyages and works with something new to us. It may be that it will come to us with some shining gem of the orient which shall flash on the eyes of all and win immediate recognition. It may also happen that it will return with something which does not glitter and attract the eyes of all; some spar, or pebble, or weed unknown or unappreciated. Our first glance may be that of disappointment. But wait and examine in patience. The tendency of poetry, as well as its sister science, is to learn the might meaning, the worlds of wisdom and the melodious anthems which lie hidden in common things, in thing that lie about us every day.

We believe the foregoing observations will be found apropos to the reader's first impression of "Maud." We confess to a feeling of disappointment. But we remember it was the same with us when we first read the "Princess." We had been listening to the singer who ended his last strain, leaving us

bewildered with the glancing glories of his imagery, enchanted with his magic melody and we had expected him to take up the strain where he left off, and to where we had followed him. But no; he has gone on in advance of us, and breaks into a new

song which we do not catch so well from the distance. The new beauty is not so immediately recognisable as the old. Or, it is as though you had been watching the majestic swan on the waters near your feet, and admiring the grace of its motion. Suddenly it dives and comes up again at a considerable space from you, and although it is the same swan, fully as majestic

and dropping rich pearls, yet it looks diminished because it dwindles in the distance. So we

found it to be with both the "Princess" and "Maud." We read them again and again, and were as surprised as delighted to find how much we missed at the first reading, how much we found in every successive perusal.

"Maud" is a tale of the time. The whole materials, save the melody, he got out of the time in which we live. Here we have nineteenth century life, with its perplexities, its wars of caste, its heart-breakings and heart-burnings, its pride of wealth and

meanness of Mammonism, its craven peace men an its red-rising battle-dawn of promise. Our mightiest master of the

"living lyre" sits down to it stern and grim, a though Carlyle had put on the singing-robe to smite a clanging iron harp.

He has put forth a new song in a new measure, and both song an measure will astonish.

In the mirror of his hero's private grief the poet shows us the public life of to-day, and the man who has fed up on delicate dainties and crowning cates at the feast of music, can give us the sponge dipped in the gall and vinegar, though not in a mocking spirit, but in a spirit of terrible, tremendous

earnest.

This burst of bitter indignation on an ignoble peace makes us stare and ask, "Is this Tennyson?"

|

PEACE.

Why do they prate of the blessings of peace? we have

made them a curse.

Pickpockets, each hand lusting all that is not its own;

And lust of gain, in the spirit of Cain is it better or

worse

Then the heart of the citizen hissing in war on it's own

hearthstone?

But these are the days of advance, the works of the men

of mind,

When who but a fool would have faith in a tradesman's

ware or his word?

Is it peace or war? Civil war, as I think, and that of a

kind

The viler, as underhand, not openly bearing the sword.

Sooner or later I too may passively take the print

Of the golden age—why not? I have neither hope nor

trust;

May make my heart as a millstone, set my face as flint,

Cheat and be cheated, and died: who knows? we are

ashes an dust.

Peace sitting under her olive, and slurring the days gone

by,

When the poor are hovell'd and hustled together, each

sex like swine.

When only the ledger lives, and when only not all men not

lie;

Peace in her vineyard—yes!—but a company forges the

wine.

And the vitriol madness flushes up in the ruffian's head,

Till the filthy by-lane rings to the yell of the trampled

wife,

While chalk and alum and plaster are sold to the poor

for bread,

And the spirit if murder works in the very means of life.

And Sleep must lie down arm'd, for the villanous centre-

bits

Grind on the wakeful ear in the hush of the moonless

nights,

While another is cheating the sick of a few last gasps, as

he sits

To pestle a poison'd poison behind his crimson lights.

When a Mammonite mother kills her babe for a burial

fee,

And Timour-Mammon grins on a pile of children's bones,

Is it peace or war? better, war! loud war by land and

by sea,

War with a thousand battles, and shaking a hundred

thrones.

For I trust if an enemy's fleet came yonder round by the

hill,

And the rushing battle-bolt sang from the three-decker

out of the foam,

That the smoothfaced snubnosed rogue would leap from

his counter and till,

And strike, if he could, were it but with his cheating

yardwand, home. |

|

|

Leaving the subject-matter of these lines, we pause to remark on the measure. At first reading it, seemed cumbersome and halting, something like the measure of "Evangeline" put into alternate

rhymes. But it grows upon you, and gains in a wonderful degree. Tennyson is a great master of movement. He has contributed some of the most subtle, plastic, and vigorous of measures to modern verse. A great deal has been attributed to the American poet Poe which originated with Tennyson. The peculiar refrain of the melody, and even the

'e' vowel rhyme to be found in "Annabel Lee" will also be found in the "Merman" and "Mermaid" of Tennyson. After he has given us the overture of this measure, the author treats us to many variations of linked sweetness long drawn out, and brings it to a glorious climax in the conclusion of the poem. Here it is. Mark the long, leaping, lyrical, wave-like burst of some of the lines. They move, and lengthen out, and shout again with Homeric gorgeousness of sound, as, for example in the "Hail once more to the banner of battle on unrolled." This conclusion is something akin to that of Locksby Hall. Says a hero of his

passion—

|

And it was but a dream, yet it yielded a dear delight

To have look'd tho' but in a dream, upon eyes so fair,

That had been in a weary world my one thing bright

And it was but a dream, yet it lighten'd my despair

When I thought that a war would arise in defence of the

right,

That an iron tyranny now should bend or cease

The glory of manhood stand on his ancient height,

Nor Britain's one sole God be the millionaire:

No more shall commerce be all in all, and Peace .

Pipe on her pastoral hillock a languid note,

And watch her harvest ripen, her herd increase,

Nor the cannon-bullet rust on a slothful shore,

And the cobweb woven across the cannon's throat,

Shall shake its threaded tears in the wind no more.

And as months ran out and rumour of battle grew

"It is time, it is time, O passionate heart," said I

(For I cleaved to a cause that I felt to be pure an true),

"It is time O passionate heart and morbid eye,

That old hysterical mock-disease should die."

And I stood on a giant deck and mix'd my breath

With a loyal people shouting a battle cry,

Till I saw the dreary phantom arise and fly

Far into the North, and battle, and seas of death.

Let it go or stay, so I wake to the higher aims

Of a land that has lost for a little her lust of gold,

And love of a peace at was full of wrongs and shames,

Horrible, hateful, monstrous, not to be told;

And hail once more to the banner of battle unroll'd!

Tho' many a light shall darken, and many shall weep

For those that are crush'd in the clash of jarring claims,

Yet God's just doom shall be wreak'd on a giant liar;

And many a darkness into the light shall leap,

And shine in the sudden making of splendid names,

And noble thought be freer under the sun,

And the heart of a people beat with one desire:

For the long, long canker of peace is over and done,

And now by the side of the Black and the Baltic deep,

And death-grinning mouths of the fortress, flames

The blood-red blossom of war with a heart of fire. |

|

|

Two sketches, one of the Millionaire of the Mine, the other of a "Quaker," have a Hogarthian

graphicness.

|

Sick, am I sick of a jealous dread?

Was not one of the two at her side—

This new-made lord, whose splendour plucks

The slavish hate from the villager's head?

Whose old grandfather has lately died,

Gone to a blacker pit, for whom

Grimy nakedness dragging his trucks

And laying his trams in a poison'd gloom

Wrought, till be crept from a gutted mine

Master of half a servile shire,

And left his coal all turn'd into gold

To a grandson, first of his noble line,

Rich in the grace all women desire,

Strong in the power that all men adore,

And simper and set their voices lower,

And soften as if to a girl, and hold

Awe-stricken breaths at a work divine,

Seeing his gewgaw castle shine,

New as his title, built last year,

There amid perky larches and pine,

And over the sullen-purple moor

(Look at it) pricking a Cockney ear.

What, has he found my jewel out?

For one of the two that rode at her side

Bound for the Hall, I am sure was he:

Bound for the Hall, and I think for a bride.

Blithe would her brother’s acceptance be.

Maud could be gracious too, no doubt,

To a lord, a captain, a padded shape,

A bought commission, a waxen face,

A rabbit mouth that is ever agape—

Bought? What is it he cannot buy?

And therefore splenetic, personal, base,

A wounded thing with a rancorous cry,

At war with myself and a wretched race,

Sick, sick to the heart of life, am I.

Last week came one to the county town,

To preach our poor little army down,

And play the game of the despot kings,

Tho’ the state has done it and thrice as well:

This broad-brimm’d hawker of holy things,

Whose ear is stuff’d with his cotton, and rings

Even in dreams to the chink of his pence,

This huckster put down war! can he tell

Whether war be a cause or a consequence?

Put down the passions that make earth Hell!

Down with ambition, avarice, pride,

Jealousy, down! cut off from the mind

The bitter springs of anger and fear;

Down too, down at your own fireside,

With the evil tongue, and the evil ear,

For each is at war with mankind.

Ah, God, for a man with heart, head, hand,

Like some of the simple great ones gone

For ever and ever by,

One still strong man in a blatant land,

Whatever they call him, what care I,

Aristocrat, democrat, autocrat—one

Who can rule and dare not lie. |

|

|

We shall abstain from an extended critic as we are anxious to enrich our review with as many extracts as we cay get in.

Surely the voice of love never sang with a more passionate sweetness than in this night-song.

What ethereal luxury and flower-like tenderness it has, and yet with what a pulse and fire of passion it beats and

glows!—

|

A NIGHT-SONG OF LOVE.

Come into the garden, Maud,

For the black bat, night, has flown,

Come into the garden, Maud,

I am here at the gate alone;

And the woodbine spices are wafted abroad,

And the musk of the rose is blown.

For a breeze of morning moves,

And the planet of Love is on high,

Beginning to faint in the light that she loves

On a bed of daffodil sky,

To faint in the light of the sun she loves,

To faint in his light, and to die.

All night have the roses heard

The flute, violin, bassoon;

All night has the casement jessamine stirr’d

To the dancers dancing in tune;

Till silence fell with the waking bird,

And a hush with the setting moon.

I said to the lily, “There is but one

With whom she has heart to be gay.

When will the dancers leave her alone?

She is weary of dance and play.”

Now half to the setting moon are gone,

And half to the rising day;

Low on the sand and loud on the stone

The last wheel echoes away.

I said to the rose, “The brief night goes

In babble and revel and wine.

O young lord-lover, what sighs are those,

For one that will never be thine?

But mine, but mine,” I sware to the rose,

“For ever and ever, mine.”

And the soul of the rose went into my blood,

As the music clash’d in the hall:

And long by the garden lake I stood,

For I heard your rivulet fall

From the lake to the meadow and on to the wood,

Our wood, that is dearer than all;

From the meadow your walks have left so sweet

That whenever a March-wind sighs

He sets the jewel-print of your feet

In violets blue as your eyes,

To the woody hollows in which we meet

And the valleys of Paradise.

The slender acacia would not shake

One long milk-bloom on the tree;

The white lake-blossom fell into the lake,

As the pimpernel dozed on the lea;

But the rose was awake all night for your sake,

Knowing your promise to me;

The lilies and roses were all awake,

They sigh'd for the dawn and thee.

Queen rose of the rosebud garden of girls,

Come hither, the dances are done,

In gloss of satin and glimmer of pearls,

Queen lily and rose in one;

Shine out, little head, sunning over with curls,

To the flowers, and be their sun.

There has fallen a splendid tear

From the passion-flower at the gate.

She is coming, my dove, my dear;

She is coming, my life, my fate;

The red rose cries, "She is near, she is near;"

And the white rose weeps, "She in late;"

The larkspur listens, "I hear, I hear;"

And the lily whispers, " I wait."

She is coming, my own, my sweet;

Were it ever so airy a tread,

My heart would hear her and beat,

Were it earth in an earthy bed;

My dust would hear her an beat,

Had I lain for a century dead;

Would start and tremble under her feet,

And blossom in purple and red. |

|

|

Very lovely, too, is the following bridal-song where we have music at dalliance with love's sweet "silly

sooth:"—

|

BRIDAL SONG.

Go not, happy day

From the shining fields,

Go not, happy day

Till the maiden yields.

Rosy is the West,

Rosy is the South,

Roses are her cheeks,

And a rose her mouth.

When the happy Yes

Falters from her lips,

Pass and blush the news

O'er the blowing ships.

Over blowing seas

Over seas at rest

Pass the happy news,

Blush it thro' the West;

Till the red man dance

By his red cedar tree,

And the red man's babe

Leap beyond the sea.

Blush from West to East,

Blush from East to West,

Till the West or East,

Blush it thro' the West,

Rosy is the West,

Rosy is the South,

Roses are her cheeks,

And a rose her mouth. |

|

|

Inimitable Tennysonian touches are abundantly scattered through-out the poem of "Maud".

Here is a fine bit on a shell:—

|

See what a lovely shell,

Small and pure is a pearl,

Lying close to my foot,

Frail, but but a work divine,

Made so fairily well

With delicate spire and whorl,

How exquisitely minute,

A miracle of design!

The tiny cell is forlorn,

Void of the little living will

That made it the stir on the shore.

Did he stand at the diamond door

Of his house in, rainbow frill?

Did he push, when he was uncurl'd,

A golden foot fairy horn

Thro' his dim water-world? |

|

|

Here also is a rich suggestion; something rises in memory:—

|

It is an echo of something

Read with a boy's delight,

Viziers nodding all together

In some Arabian night? |

|

|

Besides the poem of "Maude," there are seven others in the book, two of which we have had before

— the "Duke's Funeral" and the "Charge of the Light Brigade." The latter has bee rewritten.

The present version omits the "Down came an order which some one had blundered," which we are glad of, as it was neither true nor poetical.

But we miss the last lines—

|

"Oh, The wild charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade!

Noble six

hundred!" |

which, we submit to Mr Tennyson's consideration, is a fine and necessary

conclusion.

Trusting that we shall have quoted enough to sharpen the reader's mental appetite and send him to the book with a finer zest, we conclude by quoting the fine, free, and frank lines to "Maurice" which we should consider ample compensation for expulsion from any number of bigoted colleges.

|

TO THE REV. F. D. MAURICE.

Come, when no graver cares employ,

Godfather, come and see your boy:

Your presence will be sun in winter,

Making the little one leap for joy.

For, being of that honest few,

Who give the Freind himself his due,

Should eighty thousand coIlege-councils

Thunder 'Anathema,' friend, at you;

Should all your churchmen foam in spite

At you, so careful of the right,

Yet one lay-hearth would give you welcome

(Take it and come) to the Isle of Wight;

Where, far from noise and smoke of town,

I watch the twilight falling brown

All round a careless-order'd garden

Close the ridge of a noble down.

You'll are no scandal while you dine,

But honest talk and wholesome wine,

And only hear the magpie gossip

Garrulous under a roof of pine:

For groves of pine on either hand,

To break the blast of winter, stand

And further on, the hoary Channel

Tumbles a breaker on chalk and sand;

Where, if below the milky steep

Some ship of battle slowly creep,

And on thro' zones of light and shadow

Glimmer away to the lonely deep,

We might discuss the Northern sin

Which made a selfish war begin;

Dispute the claims, arrange the chances;

Emperor, Ottoman, which shall win:

Or whether war's avenging rod

Shall lash all Europe into blood;

Till you should turn to dearer matters,

Dear to the man that is dear to God;

How best to help the slender store

How mend the dwellings, of the poor;

How gain in life, as life advances,

Valour and charity more and more.

Come Maurice, come: the lawn as yet

Is hoar with rime, or spongy-wet;

But when the wreath of March has blossom'd,

Crocus, anemone, violet,

Or later, pay one visit here,

For those are few we hold as dear;

Now pay but one, but come for many,

Many and many a happy year. |

|

|

―――♦―――

* ED. —'Lacquey'.....butler, footman, henchman, hireling, lackey.

|

|

See also

Massey's essay 'The Poetry of Alfred

Tennyson.' |

|