|

THERE are

persons so destitute of a sense of humour, that they cannot make merry,

have no ear for a jest, no eye for the 'gayest, happiest attitude of

things,' no heart to rejoice in it. And the puritanical spirit

would fain have human nature reformed and re-stamped according to this

dull and dismal pattern; would, in truth, make this life a preparatory

process to fit us for a smileless eternity, and begin by trying to

paralyse the risible muscle of the human face. But the greatest

and the wisest men have not been of this type; they could laugh as well

as weep, and they lived in fuller perfection of spiritual health.

The deepest seers have frequently been the men who not only felt the

seriousness of life, but who also saw the province of humour as a

pleasant reconciler of opposites, and who bore their lot and wrought

their work in a brave spirit. The most earnest, we do not mean the grimmest,

of men, have had the keenest sense of fun.

We will not propose to define the nature of

humour, nor to discuss, metaphysically or philosophically, the

difference betwixt wit and humour; but as we shall have to use the

terms with some distinction of meaning, we may indicate by a few

examples the sense in which we understand and use them. When

Curran was asked by a brother lawyer, 'Do you see anything ridiculous

in this wig?' and he replied, 'Nothing but the head!' that was

wit. And when Scott describes the inmates of Cleikum Inn, in 'St.

Ronan's Well,' who thought they had seen the ghost of a murdered

man, we get humour, the root of which lies far deeper in human

nature. He says the two maidens took refuge in their bedroom,

whilst the hump-backed postillion fled like wind into the stable, and

with professional instinct began in his terror to saddle a horse.

This was his most natural refuge from the supernatural; a touch of

humour at which we smile gravely, if at all. When Hood describes a

fool whose height of folly constitutes his own monument, he calls him

|

'a column of fop,

A lighthouse without any light a-top.' |

That is wit. But when Chaucer

describes the fox as desirous of capturing the cock, and trying to

flatter him into singing by telling him how his respected father used to

sing, and put his heart so much into his song that he was obliged to

shut his eyes, and by this means gets poor chanticleer to imitate his

father and sing and shut his eyes also, whereupon the fox pounces on him

and bears him off; — that is humour; a sort of shut-eyed

humour quite irresistible. Again, we have wit when Jerrold defines

dogmatism as 'puppyism come to maturity.' But we get at humour when Panurge, in his mortal fear of shipwreck, cries,

'Would to heaven that

I was safe on dry land with (we presume, to make quite sure of his

footing) somebody kicking me!'

The strokes of wit that are most

delightfully surprising are often the most evanescent. A flash and

all is over. You must be very much on the qui vive to see

by its lightning, or you may find yourself in a similar predicament to

that of the poor fly which turned about after his head was off, to find

it out. Not so with humour. It does not cut you

short. It is for 'keeping it up.' Wit gives you a nod in

passing, but with humour you are at home. Wit is a later societary

birth. Humour was from the beginning. There are persons who

have a sense of humour to whom the pranks of wit are an

impertinence. The true account of Sidney Smith's joke respecting

the necessity of trepanning a Scotsman is that the Scotch have

the pawkiest appreciation of humour, but do not so plentifully

produce or care so much for mere wit.

In its lowest range humour can produce its

effects with means most slight and simple. Indeed it is here as it

is in art, we sometimes admire all the more, and are apt to overrate

results, on account of the insignificance of the means employed. A

good deal of what is called American humour has been produced in this

lower mental range. It is not much beyond that which is uttered

nightly by the gallery 'gods' of our theatres, or daily by some

village humourist, who is noted locally for his ludicrous perceptions

and unctuous sayings. Artemus Ward's 'How goes it old

Sweetness, said I?' is precisely on a par with the humour of English

canal boatmen. Like the Scotch, the Americans have more

humour than wit. Their writers would not shine brilliantly

in company with such men as Hood, Lamb, Sydney Smith, or Jerrold.

But the humour is many-sided, quaint, and characteristic, ranging from

the dryly demure to the uproariously extravagant.

The Yankee character is in itself an

exceedingly humorous compound. 'A strange hybrid, indeed, did

circumstances beget here in the new world upon the old Puritan stock,

and the earth never before saw such mystic practicalism, such niggard

geniality, such calculating fanaticism, such cast-iron enthusiasm, such

sour-faced humour, such close-fisted generosity.' The Yankee

will make a living out of anything, and anywhere. His ingenuity is

just the most certain lever for removing difficulties and obstacles from

his path. It has been remarked that if a Yankee were shipwrecked

overnight on an unknown island, he would be going round the first thing

in the morning trying to sell maps to the inhabitants. 'Put him,'

says Lowell, 'on Juan Fernandez, and he would make a spelling-book

first and a salt-pan afterwards.' A long, hard warfare with

necessity has made him one of the handiest, shiftiest, thriftiest, of

mortals. In trading, he is the very incarnation of the keenest

shrewdness. He will be sure to do business under the most adverse

circumstances, and secure a profit also. This propensity is

portrayed in the story of Sam Jones: that worthy, we are told, called

at the store of a Mr. Brown, with an egg in his hand, and wanted to 'dicker'

it for a darning-needle. This done, he asks Mr. Brown if he isn't

'going to treat?' 'What, on that trade?' 'Certainly; a trade is a trade, big or little.'

'Well, what will you

have?' 'A glass of wine,' said Jones. The wine was

poured out, and Jones remarked that he preferred his wine with an egg in

it. The storekeeper handed to him the identical egg which he had

just changed for the darning-needle. On breaking it, Jones

discovered that the egg had two yolks. Says he, 'Look

here, — you must give me another darning-needle!' Or to

relate one other veracious history —

'"Reckon I couldn't drive a trade with you to-day, Square," said a

genuine specimen of the Yankee pedlar, as he stood at the door of a

merchant in St. Louis.

"I reckon you calculate about right, for you can't

noways."

"Wall, I guess you need'nt git huffy 'beout it.

Now, here's a dozen ginooine razor-strops—wuth two dollars and a

half: you may hey 'em for two dollars."

"I tell you I don't want any of your traps, so you may as well

he going along."

"Wall, now, look here, Square. I'll bet you five

dollars that if you make me an offer for them 'ore strops, we'll hey a

trade yet."

"Done," said the merchant, and he staked the money. "Now,"

says he, chaffingly, "I'll give you sixpence for the strops."

"They're your'n!" said the Yankee, as he quietly

pocketed the stakes! "But," continued he, after a little

reflection, and with a burst of frankness, "I calculate a joke's a

joke; and if you don't want them strops, I'll trade back."

The merchant looked brighter. "You're not so bad a chap, after all,"

said he. "Here are your strops — give me the money."

"There it is," said the Yankee, as he took the strops and handed

back the sixpence. "A trade is a trade, and a bet is a

bet. Next time you trade with that ere sixpence, don't you buy razorstrops."'

The Yankee,

however, unlike the Jew or the Greek, has a soft place in this hard

business nature; there is a blind side to this wide-awake character;

he may be 'bamboozled' through his better feelings. And,

strangest thing of all, this acutest of creatures, is just the first to

be taken in by words. We might have fancied that a people so full

of shrewdest mother-wit, and so matter-of-fact, would easily see through

pretence, and sham, and snuffle.

' 'Tis odd,' says

Emerson, 'that our people should have, not water on the brain, but a

little gas there. Can it be that the American forest has refreshed

some weeds of old Pictish barbarism just ready to die out—the love of

the scarlet feather, of beads and tinsel? The English have a

plain taste. Pretension is the foible especially of American youth.'

But surely the boasting and buffoonery that is tolerated on American

platforms, and in American papers, cannot all be seriously swallowed by

the masses that pretend to believe in it. Surely it must be to a

great extent another form taken by the national humour. Naturally

enough, human nature likes to see itself look grand, and next to seeing

this, we should suppose the greatest pleasure is hearing it. And

the Americans 'must be cracked up,' and patriotically and

institutionally tickled; so it looks as if speakers and listeners had

tacitly leagued to keep the thing going, and that whilst the speaker or

writer distributed 'buncombe' and balderdash, the listeners accepted

it with the proper twinkle of the eye and the nod of

understanding. What but a suppressed sense of humour in both

speaker and auditors could possibly have carried off such a speech as

that attributed to Webster:—

'Men

of Rochester, I am glad to see you; and I am glad to see your noble

city. Gentlemen, I saw your falls, which I am told are one hundred

and fifty feet high. That is a very interesting fact. Gentlemen,

Rome had her Cæsar, her Scipio, her Brutus, but Rome in her proudest

days had never a waterfall a hundred and fifty feet high!

Gentlemen, Greece had her Pericles, her Demosthenes, and her Socrates,

but Greece in her palmiest days NEVER had a waterfall a hundred and

fifty feet high! Men of Rochester, go on. No people

ever lost their liberties who had a waterfall one hundred and fifty feet

high!

The kind of

humour (such as it is) to which this belongs has been named by the

Americans themselves as high falutin.

We are told that there was a paper in

Cincinnati which was very much given to 'high falutin' on the

subject of 'this great country,' until a rival paper somewhat

modified its continual bounce with the following burlesque:—

'This

is a glorious country! It has longer rivers and more of them, and

they are muddier and deeper, and run faster, and rise higher, and make

more noise, and fall lower, and do more damage than anybody else's

rivers. It has more lakes, and they are bigger and deeper and

clearer, and wetter than those of any other country. Our rail-cars

are bigger, and run faster, and pitch off the track oftener, and kill

more people than all other rail-cars in this and every other

country. Our steamboats carry bigger loads, are longer and

broader, burst their boilers oftener and send up their passengers

higher, and the captains swear harder than steamboat captains in any

other country. Our men are bigger, and longer, and thicker;

can fight harder and faster, drink more mean whisky, chew more bad

tobacco, and spit more, and spit further than in any other country.

Our ladies are richer, prettier, dress finer, spend more money, break

more hearts, wear bigger hoops, shorter dresses, and kick up the devil

generally to a greater extent than all other ladies in all other

countries. Our children squall louder, grow faster, get too

expansive for their pantaloons, and become twenty years old sooner by

some months than any other children of any other country on the earth.'

This, however,

which is meant to be a satire, can be equalled in expression and

excelled in sentiment from the ordinary literature of America written

with a seriousness not meant to be absurd.

An article, entitled 'Are we a

Good-looking People?' appeared in 'Putman's Monthly Magazine,'

March, 1853, the writer of which maintains that John Bull won't do;

he 'must be done over again' on the Yankee model of humanity.

'Jonathan may be described as the finishing model of the Anglo-Saxon,

of which John Bull is the rough cast.' He goes on to say that

American ladies surpass all other women. American 'notabilities

are better looking than most notabilities elsewhere.' American

'crowds, and public gatherings, and thronged streets, show the

best-looking aggregate of humanity, male and female, in the world.'

To show how much superior in stature the Americans are, he says: 'Put

Lord John Russell and Daniel Webster back to back, and mark how the

Americans overtop their English relatives.' The American 'features

are more sharply chiselled than in any other people,' and their 'foreheads

are higher and wider.' In expression (he does not mean language)

'the Americans surpass every other people. The expression

of the common face of America is without doubt the finest in the world.'

He concludes that 'man has never had so fair a chance as in America

'- not only of living in the world or of diversifying his way of going

out of it, but he emphatically asserts that, until the American woman

was formed, or reformed, man had never had but half a chance of coming

into the world. 'It is easier, say the midwives, to come into

this world of America than any other world extant.'

As a matter of choice we prefer the humour

of the serious writing to that of the intentional parody. It is

ever the most provocative of mirth when the humour produces its effects

with unconsciousness of manner. Many writers assume this look and

attitude, and thus render their drollery all the drier. But

they cannot possibly compete with the man who does not know that he is

making fun all the while he is so much in earnest, and whose jokes are

too subtle for his own perception. This is one of the most

laughable aspects of American humour.

Again, the Yankee character has presented to

the world a fresh complexity of the great human problem. Hitherto

we have been in the habit of thinking that boasting and doing were

almost incompatible. And here is a nation of boasters who can act

as vigorously as they can brag; who can keep up a lusty crow under the

most discouraging circumstances, go on telling the world what they mean

to do and be as good as their word in the end. The Yankees can

both brag and hold fast. Of course it was not, even with them, the

great boasters that did the real work. Their fighting-men were

comparatively silent; they did not spend their breath in words, but put

it into blows. The burden was borne, the success attained by those

who knew how to put the

|

'silent rhyme,

Twixt upright Will and downright Action; |

men who had come to the conclusion

that

|

'Words,

if you keep them, pay their keep,

But gabble's the short cut to ruin;

It's gratis (gals half-price), but cheap

At no rate, if it hinders doin'.' |

Still, the

national character includes these two extremes; thus creating that

congruity out of the incongruous which is so great and effective an

element in the production of humour.

One of the earliest, most obvious, and most

easily illustrated characteristics of Yankee humour is its lusty

hyperbole and power of boundless exaggeration. It is great in 'throwing

the hatchet,' and 'pitching it strong;' mighty in drawing the 'long-bow'

for a flight unparalleled. In this respect it shows some traits of

kinship to the old Norse humour, with its immeasurable broad grins and

huge uncontrollable laughters. We catch a far-off echo from the

back woods of the new world of that Brobdingnagian humour which once

delighted the Norsemen in the old. The story-tellers are not the

simple men of the Sagas; they have acquired a few more 'wrinkles'

of knowledge; the laugh has lost somewhat of the old hearty ring; the

imagination is seldom sublime; still we recognize the instinct of race

working on and asserting itself; and in defiance of time, and change,

and shape, we find an affinity here to the broad humour of the blithe

Norsemen.

We can trace certain types of Norse humour

in some of the Yankee stories. Also in expression there is yet a

speaking likeness. At the gate of Urgard, says the Norseman, you

found it so high that 'you had to strain your neck bending back to

see to the top!' In the Norse tales we have a character who

listens and listens until 'his ears are fit to fall off!'

Another is in such a passion he 'does not know which leg to stand

upon.' Another has such a bush of beard that the birds come

and build their nests in it. Speaking of a very long distance, the

North Wind attempts to indicate it by saying that 'once in his

life he blew an aspen leaf thither, but it made him so tired he

could not blow a puff for ever so many days after.' And

surely the American Eagle, of which we hear such astounding things, must

be one with that great Giant of the Edda who sits at the end

of the world in eagle's shape, and when he flaps his wings all the

winds come that blow upon man.'

This tendency to humorous exaggeration has

run to riot in the Yankee mind, especially in that which is a dweller

somewhere 'down East' or 'out West.' In comparison with

its faculty for 'stretching it' when 'spinning a yarn,' the 'going

in for it,' the 'piling of it up,' the Norse originals are left

far behind. In no domain does it 'go-a-head' more rapidly than

in 'running a rig' with that species of humour which depends on

enormous lying for its success. Something vast in this way might

have been anticipated from a people born and bound to 'whip all

creation;' the children of Nature and of Freedom,' half horse and

half alligator, with a dash of earthquake, whose country is bounded 'on

the East by the Atlantic ocean, on the North by the Aurora Borealis, on

the West by the setting Sun, and on the South by the Day of Judgment.'

The Geography has been too much for the brain. Thus we meet

with a Yankee in England who is afraid of taking his usual morning walk

lest he should step off the edge of the country. Another, who had

been to Europe, when asked if he had crossed the Alps, said he guessed

they did come over so me risin greound.

It is related of one of this class which

nothing astonishes, nothing upsets, that he wanted to send a message by

telegraph, something like a thousand miles, and on being informed that

it would take ten minutes said he couldn't wait.

|

|

|

Nathaniel Hawthorne

(1804-64) |

Akin to which is the story told by Mr.

Howells, in his recent work on Venetian Life, of a 'sharp, bustling,

go-a-head Yankee,' who rushed into the Armenian convent one morning

rubbing his hands, and demanded that they should show him all they

could in five minutes. The Yankees pride themselves on this

trait of their character. They consider themselves much quicker

and 'cuter' than the slow unwieldy English. Mr. Hawthorne

found one of his consolations in this fact. We have never heard,

however, what become of that particularly acute child (Yankee of course)

who left his home and native parish at the age of fifteen months,

because he was given to understand that his parents intended to call

him 'Caleb.' There can be no doubt that so precociously

sensitive an advanced intellect was soon snuffed out.

Here is a bit of Yankee humour really worthy

of the Norse imagination. It is so ridiculous as to be within one

step of the sublime. A traveller called at an hotel in Albany, and

asked the waiter for a bootjack. 'What for?' said the

astonished waiter. 'To take off my boots.' 'Jabers what a fut!'

the waiter remarked, as he surveyed the monstrosity, for the man had an

enormous foot. At length, we may say at full-length, he gave it as his

opinion that there wasn't a bootjack in all creation of any use for a 'fut' like that, and if the traveller wanted

'them are' boots

off he would have to go back to the fork in the roads to get them off.'

The Yankee also too keenly follows out the

consequence of any embarrassment in which he finds himself. To

take a recent illustration of this tendency, a Pittsburgh paper states

that a melancholy case of self-murder occurred on Sunday, near Titusvile,

Pennsylvania. The following schedule of misfortunes was found in

the victim's left boot:—

'I

married a widow who had a grown-up daughter. My father visited our

house very often, fell in love with my step-daughter and married

her. So my father became my son-in-law, and my step-daughter my

mother, because she was my father's wife. Some time afterwards

my wife had a son—he was my father's brother-in-law and my uncle,

for he was the brother of my step-mother. My father's wife—i.e.

my step-daughter, had also a son; he was, of course, my brother, and in

the meantime my grandchild, for he was the son of my daughter. My

wife was my grandmother, because she was my mother's mother. I was my

wife's husband and grandchild at the same time. And as the

husband of a person's grandmother is his grandfather, I was my own

grandfather.'

It may have been

'out West' that the thieves were so 'smart' they stole a felled

walnut-tree in the night-time; drew the log right slick out of the

bark, and left the five watchers sitting fast asleep astride the rind! Kentucky must have the credit for that wonderful curative

ointment, which was so effective that when a dog's tail had been cut

off, they had only to apply the ointment whereupon a new tail instantly

sprouted, and a youngster, with a genuine Yankee turn of thought, picked

up the old tail, and tried the ointment upon it, when it grew into a

second dog, so like the other that no one could tell which was which.

There is just a smile of this kind of

humour in a story told of two Yankees on meeting; the one said, 'How

are you, old Ben Russell?' 'Come now,' says the other, 'I'll

bet you I aint any older than you! Tell us, what is the earliest reccollection that you have?'

'Well,' says he, looking back

intently through the mists of memory, 'the very first thing that I can

remember is hearing people say, as you went by, 'There goes old Ben

Russell!' Holmes has neatly bottled a flash of this

lightning, and put it into verse.

|

'Rudolph,

professor of the headsman's trade,

Alike was famous for his arm and blade.

One day a prisoner Justice had to kill,

Knelt at the block to test the artist's skill.

Bare-armed, swart-visaged, gaunt, and shaggy-browed,

Rudolph the headsman rose above the crowd,

His falchion lighten'd with a sudden gleam,

As the pike's armour flashes in the stream.

He sheathed his blade; he turned as if to go;

The victim knelt, still waiting for the blow.

"Why strikest not? Perform thy murderous act,"

The prisoner said. (His voice was slightly crack'd.)

"Friend, I have struck," the artist straight

replied;

"Wait but one moment, and yourself decide."

He held his snuff-box—"Now then, if you please!"

The prisoner sniffed, and with a crashing sneeze,

Off his head tumbled—bowled along the floor—

Bounced down the steps; the prisoner said no more.' |

The Americans

are rich in specimens of what we may call the humours of character,

though, we should imagine, these are much droller in life than the dried

samples we have gathered up in books.

A complicated case was rather nicely met by

an American preacher, who owned half of a negro slave, and who used in

his prayers to supplicate the blessings of heaven on his house, his

family, his land, and his half of Pompey.

The late President Lincoln was very

fond of one particular form of Yankee humour, which consists of telling

a little allegorical story pat to the purpose, and pointedly

illustrative of some present difficulty. He had a large fund of

personal humour, by the aid of which his other self often took refuge

behind the mask that has a broad grin on it. In this way he was

enabled to parry many obstinate questionings which pressed inopportunely

upon him. No one ever had a quicker eye for the humours of the

national character, but it is evident that his grim jests and strange

mirth were only deep sadness in other shapes; bubbles from the troubled

depths. He was by no means author of all the sayings attributed to

him. Some of these are older than he himself was. Many were

well known before he made use of them and re-stamped them for a quicker

and wider circulation. Of this class was his story of the man who

would not change horses when crossing a stream, applied by him as an

argument against changing his Cabinet at a peculiar time. His

favourite illustration of a round peg in a square hole, by which he

indicated a man who did not fit his place, is one of Sydney Smith's

happy markings-off. It occurs at least twice in the course of his

'Letters.' And this reminds us that various stories collected

in 'American Wit and Humour' have already seen much service in the

old world before they were transplanted. One of these belongs

originally to Partridge, the Almanack Maker, and it has been applied to

David Ditson.

Curiously enough, we find cited as a sample

of American humour a description of a man who had fallen in love and

been wrecked on the coral reefs, namely, of a woman's red lips.

And in a quaint old English love-poem, probably of the seventeenth

century, we find the idea in these lines—

|

'Tell

me not of your starrie eyes,

Your lips that seem on roses fed,

Your breasts, where Cupid trembling lies,

Nor sleeps for kissing of his bed;

These are but gauds: nay, what are lips?

Coral beneath the ocean-stream,

Whose brink when your adventurer slips,

Full of the perisheth on them.' |

It is difficult

to discover anything under the sun that is perfectly new. What the

Americans are and do is often so much more ludicrous than what they

write. The first specimen of American humour which attracted much

attention among us was 'Major Downing's Letters,' a keen political

satire, which presented us with the first authentic specimen of the

wonderful tongue which forms the actual colloquial dialect of the United

states.* Major Downing represented very cleverly

the bluntness and shrewdness of a country Yankee. He was the

parent of Sam Slick, who was the great illustrator of the style of

humorous exaggeration; but as Sam was not a Yankee, and as enormous

lying is not the most valuable feature of Yankee humour, we do not

include him in the present article, which is devoted to the humour of

the Yankee writers themselves. And we must avow that in our

opinion the Yankee humour has not the ruddy health, the abounding animal

spirits, the glow and glory of healthful and hearty life of our greatest

English. As the Yankee has a leaner look, a thinner humanity, than

the typical Englishman who gives such a fleshy and burly embodiment to

his love of beef and beer, so the humour is less plump and

rubicund. It does not revel in the same richness, nor enjoy its

wealth in the same happy unconscious way, nor attain to the like fulness

and play of power. We cannot imagine Yankee humour, with its dry

drollery, its shrewd keeking, shut-eyed way of looking at things,

ever embodying such a mountain of mirth as we have in Falstaff.

|

|

|

James Russell Lowell

(1819-91) |

But, as Lowell reminds us, the men who

peopled the New England States were not the traditionary full-fed,

rotund, and rosy-gilled Englishmen, but a hard-faced, atrabilious,

earnest-eyed race, somewhat 'stiff with long wrestling with the Lord

in prayer, and who had taught Satan to dread the new Puritan hug.'

Then their sense of freedom scarcely included the liberty of the lungs

in full crow with merriment. And if they felt internal ticklings

now and again they were sure to suspect it was the devil's work.

It was necessary, they fancied, to keep the face rigidly set in order

that they might preserve their spiritual balance. So they kept

watch and ward against all such wanton wiles of the wicked one.

Thus humour lived a more silent and stunted life it grew slyer in

character and more covert in expression; it learned to say the drollest

things with the old family face and with a sense of the stern Puritan

eye still upon it. Such, we think, was the early formation of its

most characteristic manner. And this manner has been very recently

illustrated by the 'Sayings' of Josh Billings. Josh never

laughs downright. There may be a knowing light in his eye, an

oafish pucker at the corners of the mouth, otherwise he is prim as a

Puritan; his hearing is formed on the early model. The

Yankee has a knack of splitting his sides silently and making no outward

sign. He does not laugh, he only chuckles internally. We

have heard of an English actor who went to New York, and on the first

night of his playing performed an exceedingly comic part, in which he

was accustomed to produce roars of laughter. But here there was

scarcely a grin. He thought he must have failed

altogether. On leaving the theatre he heard two of the audience

conversing on the subject of his acting. 'Never saw such a funny

fellow in all my life,' said one; and the other replied, 'Thought I

should have busted twenty times over.' But they had kept it to

themselves whilst inside the theatre. So is it with 'Josh

Billings' personally: a few of whose sayings we quote:—

'Some

people are fond of bragging about their ancestors, and their great

descent, when in fact their great descent is just what is the

matter of them.'

'If I was asked, "What is the chief end of man now-a-days,"

I should immediately reply, "10 per cent."

'It is dreadful easy to be a fool. A man can be a fool and

not know it.'

'God save the fools, and don't let them run out! for if it

wasn't for them, wise men couldn't get a living.'

'It is true that wealth won't make a man virtuous, but I

notice there ain't anybody who wants to be poor just for the purpose of

being good.'

'There are some dogs' tails which can't be got to curl

no-ways, and some which will, and you can stop 'em. If you bathe

a curly dog's tail in oil and bind it in splints, you can't get the

crook out of it. Now a man's ways of thinking is the crook in the dog's

tail, and can't be got out; and every one should be allowed to wag his

own peculiarity in peace.'

'When a fellow gets to going down hill, it does seem as though

everything had been greased for the occasion.'

Josh Billings'

notions respecting the animal kingdom are very amusing at times.

This of the mule for instance:—

'The

mule is half horse and half Jackass, and then comes to a full stop,

Nature discovering her mistake. The only way to keep a mule in a

pasture is to turn it into a meadow adjoining, and let it jump out.

They are like some men, very corrupt at heart. I've known them

to be good mules for six months, just to get a good chance to kick

somebody. The only reason why they are patient is because they

are ashamed of themselves.'

His puritanical

manner and dry caustic cynicism notwithstanding, 'Josh Billings' can

tell 'whoppers' on occasion after the 'down East' fashion, the

uproarious breakings out of nature long repressed. He has likewise

a touch of a kind of humour that in itself is inexpressible, in its

character indescribable, in its appeal helplessly ludicrous. An

example of what we mean occurs in Dickens's 'American Notes.'

We think it is the writer himself who was standing on the deck of the

vessel in a storm, up to his knees in water; and when some one suggested

that he would take cold, he pointed down towards his feet and murmured 'cork soles.'

It must be merely from imitation that Josh

Billings has adopted his mode of spelling. It does not in the

least enrich his humour, has no affinities to it. In the case of Artemus

Ward, we may imagine it to be a part of the speaker's character.

With him it looks like an element in that species of drollery which is

his forte; it helps to elongate and drawl out the

humour. But many of Josh Billings' sayings are keen enough for

the short, sharp, direct utterance of Douglas Jerrold, and the spelling

is an annoying obstruction; this we have removed in our quotations.

Again, in relation to the old world, there

is a spice of the Gamin nature in American humour, a dash of

impudence in the way it will 'take a sight' at the venerable author

of its being, or, as it may consider, the 'onnatural old parent.'

It can he as amusingly pert in its patronage of England as Mr. Bailey

was when his impudent eyes detected in Sairey Gamp the remains of a fine

woman. Its assumption is astoundingly vast; it takes such a range

of conditions for granted, each of which we should dispute at the

outset, and every one of which we might consider totally

inadmissible. But, whilst we may be pointing out the impossible

premises, it has reached its equally impossible conclusions.

Sometimes this is done with the consciousness made visible. At

other times it attains its triumph in apparent unconsciousness of the

existence of the societary or personal distinctions which it so coolly

and so utterly ignores. Not that we believe in the unconsciousness

of Yankee humour. If unconscious, it would be more self-enjoying,

and experience more 'the delight of happy laughter.' The

utmost that it can reach is a sort of knowing unconsciousness.

Artemus Ward will help to make our meaning understood. He has

given to it the broadest illustration in his well-known 'Interview with

the Prince of Wales in Canada.'

Artemus Ward, however, is

not so good in his sayings as in his scenes; but the most racy of

these, such as his Interview with the Prince of Wales in Canada, and his

Courtship of Betsey Jane, are too long for quotation in full. The

position of the lovers in the courting scene must have been rather a

perilous one:—

We

sot thar on the fense, a swingin our feet two and fro, blushin as red as

the Baldinsville skool house when it was fast painted, and lookin very

simple, I make no doubt. My left arm was ockepied in ballunsin

myself on the fense, while my rite was woundid luvinly round her waste.'

The natural reasons why the two

were drawn together are amusingly simple:—

'Thare

was many affectin ties which made me hanker arter Betsey Jane. Her

father's farm jined our'n; their cows and our'n squencbt their

thirst at the same spring; our old mares both had stars in their forrerds; the measles broke out in both famerlies at nearly the same

period; our parients (Betsey's and mine) slept reglarly every Sunday

in the same meetin house, and the nabers used to obsarve, "Wow thick

the Wards and Peasley's air!" It was a surblime site, in the

Spring of the year, to see our sevral mothers (Betsey's and mine) with

their gowns pin'd up so thay could'nt sile 'em, affeeshunitly

Biling sope together & aboozing the nabers.'

The humour of

Artemas Ward hardly attains the dignity of literature. If

Republicans kept their fools, we might class him with the court jesters

of old. He is a species of the practical joker who wears a cap and

bells. To us it seems that the drollery would be better spoken

than written. It wants the appropriate facial and nasal expression

to make it complete. Now and then, however, he says

something perfect in itself, as where he announces that 'the world

continues to revolve round on her own axeltree onct in every twenty-four

hours, subjeck to the Constitution of the United States.' 'If

you ask me,' he says, 'how pious Brigham Young is? I treat it as a

conundrum, and give it up.'

After all, we do not see that he gains much

by his mis-spelling. Mr. Ward makes no humourous use of this

device. The spelling here, as with Josh Billings and others, is

neither genuinely Yankee nor really witty. Indeed, this habit of

trying to make letters do the grinning, looks like an African

perception of the ludicrous: a trick caught from the negro.

The faculty which the negro has for making

fun by the distortion of language is well known. The sound that

words make when tortured appears to please his fancy, and constitute a

sort of humour; and America is now producing as many imitators of this grotesquerie

which is natural to the negro, as it has sent forth followers of the

negro minstrel in the swarms of sham Ethiopian and other serenaders.

It is quite true that iteration, if

not an element of humour, is at least a potent instrument for tickling

the ears of the multitude, as we may learn from the inextinguishable

laughter produced in our own country by so very moderate a piece of

pleasantry as 'How's your poor feet?' or the Parisian 'Where's

Lambert?' or any other vulgar catchword. By constant

repetition, together with the absurd appeal to the gravity of the person

addressed, a sort of fun is generated, and thousands can repeat and

repeat it, and enjoy the jest as much as if it contained the best wit in

the world.

In the 'Biglow Papers' the spelling is

perfectly legitimate. It carefully reproduces a dialect, and we

have real nature contributing to the purpose of art.

In this description of Hosea Biglow by his

father, the spelling is an essential part of the representation.

It not only helps to set before us the rustic poet under inspiration, in

life-like colours, but it also served to give bucolic character and

national twang to the speaker's self.

'Hosea he com home considerabal riled, and arter I'd

gone to bed I heern Him a thrashin round like a short-tailed Bull in fli

time. The old Wotnan ses she to me, ses she, Zekle, ses she, our

Hosee's gut the chollery or suthin another ses she, don't you Bee skeered, ses I, he's ony amaking pottery ses i, he's ollers on hand

at that cre busynes like Da & martin, and shure enuf, cum mornin,

Hosy, he cum down stares full chizzle, hare on eend and cote tales flyin,

and sot rite of to go reed his varses to Parson Wilbur hem he haint aney

grate shows o' book larnin himself, bimeby he cum back and sed the

parson wuz dreffle tickled with 'em as I hoop you will Be, and said

they wuz True grit.'

'Hosy ses he sed suthin' a nuther about

Simplex Mundishes or sum sech feller, but I guess Hosea kind o' didn't

hear him, for I never hearn o' nobody o' that name in this villadge,

and I've lived here man and boy 76 year cum next tatur digging, and

thar aint nowheres a kitting spryer'n I be.

But the work of

which we are now speaking is the lustiest product of the national humour; it is Yankee through and through; indigenous as the flowers of the

soil, native as the note of the bob-a-link. The author is a poet

of considerable repute, who has written much beautiful verse. But

he has never fulfilled his early promise in serious poetry. In

this book alone has he reached his full stature, and written with the

utmost pith and power. Doubtless because in this he relies more on

the national life, his work is more en rapport with the national

character, and thus the book is one of those that could only be written

in one country, and at one period of history. The enduring

elements of art, of poetry, of humour, must be found at home or

nowhere. And the crowning quality of Lowell's humour is, that it

was found at home, his book is a national birth.

The 'Biglow Papers' include most of the

aspects of American humour upon which we have touched, the racy and

hilarious yet matter-of-fact hyperbole, that is, 'audible and

full of vent;' the boundless exaggeration uttered most demurely, the knowing

unconsciousness, and other characteristic clues. They have also

that infusion of poetry which is necessary to humour at its best.

The two great characters of the book are the

'Rev. Homer Wilbur,' to whom Hosea Biglow, the young poet, takes his

verses, and 'Birdofredum Sawin.' But there are various smaller

sketches of character admirably drawn with the fewest strokes. We

have not room for the Newspaper Editor, one of the base 'mutton-loving

shepherds,' of which says the Rev. Homer Wilbur, there are two

thousand in the United States.

The life and glory of the Biglow Papers is

Mr. 'Birdofredum Sawin.' His experiences are as delightful as

his character is disreputable and true to nature. He has been

through the Mexican war, and this is his description of his

losses. Among other things he has lost a leg; however, he has

gained a new wooden one.

This was what he got, instead of making his

fortune as he had anticipated. Dilapidated and maimed as he is,

useless for anything else, he proposes to canvas for the Presidency, and

his instructions for agents show genuine insight, a fine sagacity—

|

'Ef,

wile you're 'lectioneerin' round, some cur us chaps should beg

To know my views o' state affairs, jest answer

WOODEN LEG?

Ef they aint settisfied with thet, an' kin' O' pry

an' doubt,

An'ax fer sutthin' deffynit, jest say ONE

EYE PUT OUT!

Then you can call me "Timbertoes,"- thet's wut the people

likes;

Sutthin' combinin' morril truth with phrases sech

ez strikes;

"Old Timbertoes," you see, 's a creed it's safe

to be quite bold on,

There's nothin' in't the other side can any ways

git hold on;

It's a good tangible idee, a sutthin' to embody

Thet valooable class o' men who look thin

brandy-toddy;

It gives a Party Platform, tu, jest level with the

mind

Of all right-thinkin', honest folks thet mean

to go it blind;

Then there air other good hooraws to dror on

ez

you need 'em,

Sech ez the ONE-EYED SLARTEREE,

the BLOODY BIRDOFREDUM;

Them's wut takes hold o' folks thet think, ez well

ez o' the masses,

An' makes you sartin o' the aid o' good men

of all classes.' |

Lowell tried

during the late war to continue his 'Biglow Papers.' It is

proverbially difficult to continue a work like this, as difficult, we

should say, as it is to continue a first child in the person and

character of a second. But he succeeded in writing one or two

papers worthy of being included in the design. It is interesting,

on looking hack now, to observe how much national character there is in

the book. The theme on which he wrote is obsolete, but the human

nature remains the same. 'Birdofredum Sawin' is vital and

superior to circumstance, and impudent as ever.

Neither Lowell nor any other American

poet has ever before painted the coming of the New England spring with

the native beauty and new-world truth of these lines—

|

'Fust

come the blackbirds clatt'rin' in tall trees,

An' settlin' things in windy Congresses,—

'Fore long the trees begin to show belief,—

The maple crimsons to a coral-reef,

Then saffern swarms swing off from all the willers

So plump they look like yaller caterpillars,

Then grey hossches'nuts leetle hands unfold

Softer'n a baby's be at three days old:

This is the robin's almanick; he knows

Thet arter this ther' 's only' blossom-snows;

So, choosin' out a handy crotch an' spouse,

He goes to plast'riu' his adobe house.

Then seems to come a hitch, - things lag behind,

Till some fine mornin' Spring makes up her

mind,

An' ez, when snow-swelled rivers cresh their

dams

Heaped-up with ice thet dovetails in an' jams,

A leak comes spirtin' thru some pin-hole cleft,

Grows s'ronger, fercer, tears out right an' left,

Then all the waters bow themselves an' come,

Suddin, in one gret slope o' shedderin' foam.

Jes' so our Spring gits everythin' in tune

An' gives one leap from April into June:

Then all comes crowdin' in; afore you think,

The oak-buds mist the side-hill woods with

pink,

The catbird in the laylock-bush is loud,

The orchards turn to heaps o' rosy cloud,

In ellum-shrowds the flashin' hangbird clings

An' for the summer vy'ge his hammock slings,

All down the loose-walled lanes in archin' bowers

The barb'ry droops its strings o' golden flowers

Whose shrinkin' hearts the school-gals love to try

With pins,—they'll worry yourn so, boys,

bimeby!

Nuff sed, June's bridesman, poet o' the year,

Gladness on wings, the bobolink, is here;

Half-hid in tip-top apple-blooms he swings,

Or climbs aginst the breeze with quiverin'

wings,

Or, givin' way to't in a mock despair,

Runs down, a brook o' laughter, thru the air.' |

Lowell has

fought long and strenuously against negro slavery, and lashed the vices

of American politics. But his ballad of 'The Courtin' is on

quite a different theme, and causes a regret that he has not written

more rustic poetry:—

|

'Zekle

crep' up, quite unbeknown,

An' peeked in thru the winder,

An' there sot Huldy all alone,

'ith no one nigh to hender.

Agin' the chimbly, crooknecks hung,

An' in amongst 'em

rusted

The ole Queen's arm thet gran'ther Young

Fetehed back from Concord

busted.

The wannut logs shot sparkles out

Towards the pootiest, bless her!

An' leetle fires danced all about

The chiny on the dresser.

The very room, coz she wur in,

Looked warm frum floor to

ceilin',

An' she looked full ez rosy agin

Ez th' apples she wuz

peelin'.

She heerd a foot an' knowed it, tu,

Araspin' on the scraper,—

All ways to once her feelins flew

Like sparks in burnt-up

paper.

He kin' o' l'itered on the mat,

Some doubtfle o' the seekle;

His heart kep' goin' pitypat,

But hern went pity Zekle.

An' yet she gin her cheer a jerk

Ez though she wished him

furder,

An' on her apples kep' to work

Ez ef a wager spurred her.

"You want to see my Pa, I spose?"

"Wal, no; I come designin—"

"To see my Ma? She's sprinklin' clo'es

Agin tomorrow's i'nin'."

He stood a spell on one foot fust,

Then stood a spell on

tother,

An' on which one he felt the wust

He couldn't ha' told

ye, nuther.

He was six foot o' man A 1,

Clean grit an' human natur;

None couldn't quicker pitch a ton

Nor dror a furrer

straighter.

He'd sparked it with full twenty gals,

He'd squired 'em,

danced 'em, druv 'em,

Fust this one and then thet by spells,—

All is, he couldn't love

'em.

But long o' her his veins 'ould run,

All crinkly like curled

maple.

The side she breshed felt full o' sun

Ez a South slope in Ap'il.

She thought no v'ice hed such a swing

Ez hisn in the choir,

My! when he made Ole Hundred ring,

She know'd the

Lord was nigher.

Sez he, "I'd better call agin;"

Sez she, "Think likely, Mister;"

The last word pricked him like a pin,

An'— wal, he up and

kist her.

When Ma bimeby upon 'em slips,

Huldy sot pale ez ashes,

All kind o' smily round the lips,

An' teary round the

lashes.

Her blood riz quick, though, like the tide

Down to the Bay o' Fundy,

Au' all I know is they wuz cried

In meetin', cum nex Sunday.' |

In this we see

humour at play with sentiment, and should like to have had more such interiors

pictured with the same vividness and delightful ease. In the other

poems we meet with humour—Yankee humour—in a working mood.

Hosea Biglow means 'business' when he enters the arena, and he

strikes his blows with the most sinewy strength; they go right home

with the utmost directness. The scorn that is concentrated in a

local phrase, the satire that is conveyed in the homeliest imagery, are

hurled with double force; the irony often reaches a Swift-like

intensity. The amount of hard truth here flung in a humorous guise

at humbugs political and literary is positively overwhelming. And

to enhance the effect there is that Yankee dialect, with its aggravating

drawl. Therefore we look upon the 'Biglow Papers' as the most

characteristic and complete expression of American humour.

We do not purpose including the humour of

Irving in this sketch. It does not smack strongly of the American

soil; its characteristics are old English rather than modern

Yankee. In its own mild way it is akin to the best humour, that

which gives forth the fragrance of feeling, and is a pervasive

influence, elusive and ethereal, sweet and shy; the loving effluence of

a kindly nature whose still smiles are often more significant, and come

from a deeper source, than the loudest laughter. This is the

quality likewise of Hawthorne's humour. But his has more

piquancy and new-world flavour. To do it justice, however,

would demand a close psychological study, so curious and complex were

the nature and genius of the man; the nature was a singular growth for

such a soil, the genius out of keeping with the environment, or, as the

Americans would say, the 'fixings,' —a new-world man who shrank

like a sensitive plant from the heat, and haste, and loudness of his

countrymen, and whose brooding mind was haunted by shadows from the

past. There was a sombre background to his mind or temperament,

against which the humour plays more brightly. In the piece

entitled the 'Celestial Railroad,' a modern version of the 'Pilgrim's

Progress,' which shows how easy it is to do the journey now-a-days by

the new and improved passage to the Celestial City, where stood the

wicket-gate of old we now find a station. Here you take your

ticket, and there is no need of carrying your burthen on your back, as

did poor Christian; that goes in the luggage-van. A bridge has

been thrown across the Slough of Despond. There is no longer any

feud betwixt Beelzebub and the wicket-gate keeper. They are now

partners in the same concern, with all the ancient difficulties amicably

arranged. A tunnel passes through the hill Difficulty, with the debris

of which they have filled up the Valley of Humiliation; and instead of

meeting pilgrims and compelling them to mortal combat, Apollyon is the

engine-driver. The passage is safe, the journey is short, but

somehow, when the end is near, the doubts thicken, and the smile of the

humourist is of a kind to awaken grave troubled thoughts.

Hitherto slavery and politics have been the

chief subjects of the best American humour. The great social

satirist has to come. And should he arise there will be ample

scope for the play of his saturnine humour. 'The leading defect

of the Yankee,' says an American writer, E. P. Whipple, 'consists in

the gulf which separates his moral opinions from his moral principles! His talk about virtue in the abstract would pass as sound in a

nation of saints, but he still contrives that his interests shall not

suffer by the rigidity of his maxims. Your true Yankee, indeed,

has a spruce, clean, Pecksniffian way of doing a wrong, which is

inimitable. Believing, after a certain fashion, in justice and

retribution, he still thinks that a sly, shrewd, keen, supple gentleman,

like himself, can dodge in a quiet way the moral laws of the universe,

without any particular bother being made about it.' This affords

a fine opening for the great humourist with genuine insight and a sure

touch; a nature that can 'coin the heart for jests,' use the scalpel

smilingly, apply the caustic genially, and give the bitter drink

blandly. Would the Americans welcome such a writer? There

was a time when they would not: we think there are signs that they now

would. They are beginning to laugh, and to laugh at their own

expense. This is finding out the true remedy for that

over-sensitiveness at the laugh of others which has tyrannized over them

so long.

|

|

|

George William Curtis

(1824-92) |

The author of the 'Potiphar Papers 'has

attempted to satirize the vices and foibles of the 'upper ten

thousand,' the ruinous extravagance and vulgar display, the insane

ambition to blow the loudest trumpet and beat the biggest drum, the

crushing and trampling to get a front seat in the universe of fashion,

i.e. a palatial residence with thirty feet of frontage; the

coarse worship of wealth, the pompous profusion, and the vain endeavours

of a shoddy aristocracy to outshine all foreign splendours; the houses

which are 'like a woman dressed in Ninon de l'Enclos' bodice, with

Queen Anne's hooped skirt, who limps in Chinese shoes, and wears an

Elizabethan ruff round her neck and a Druse's horn on her head;'

the vast mirrors that only serve to magnify the carnival of incongruity; the want of taste everywhere, or rather the prevalence of the taste

that estimates all things as beautiful and precious which cost a great

deal of money. One of the best characters in these papers is 'Thurz

Pasha,' ambassador from the 'King of Sennaar.' He writes

home to his royal master the results of his experience. 'I have

found them (the Americans) totally free from the petty ambitions, the

bitter resolves, and the hollow pretences, that characterize the society

of older States. The people of the first fashion unite the

greatest simplicity of character with the utmost variety of

intelligence, and the most graceful elegance of manner.

'The

universal courtesy and consideration—the gentle charity, which does

not consider the appearance but the substance—the republican

independence, which teaches foreign lords and ladies the worthlessness

of mere rank, by obviously respecting the character and not the title—the

eagerness with which foreign habits are subdued, by the positive nature

of American manners—the readiness to assist—the total want of coarse

social emulation—the absence of ignorance, prejudice, and vulgarity in

the selecter circles - the broad, sweet, catholic welcome to all that is

essentially national and characteristic, which sends the young American

abroad only that he may return eschewing European habits, and with a

confidence in man and his country chastened by experience—these have

most interested and charmed me in the observation of this pleasing

people. They are never ashamed to confess that they are poor.

They acknowledge the equal dignity of all kinds of labour, and do not

presume on any social difference between their baker and themselves.

Knowing that luxury enervates a nation, they aim to show in their lives,

as in their persons, that simplicity is the finest ornament. We,

who are reputed savages, might well be astonished and fascinated with

the results of civilization, as they are here displayed.'

|

|

|

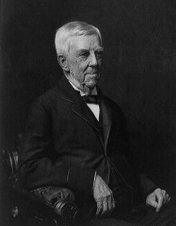

Oliver Wendell Holmes

(1809-1894) |

Oliver Wendell

Holmes is likewise doing his best to tell his countrymen a few truths it

was well they should learn, especially from their own writers. He

can say the most unpalatable things in the pleasantest possible

way. He does not appeal to the pride and pugnacity of his

countrymen, or tell them that America is the only place in which a man

can stand upright and draw free breath. He thinks there is 'no

sufficient flavour of humanity in the soil' out of which they grow,

and that it makes a man humane to 'live on the old humanized soil'

of Europe. He will not deny the past for the sake of gloryfying

the present. 'They say a dead man's hand cures swellings if

laid on them; nothing like the dead cold hand of the past to take down

our tumid egotism.' He is equally the enemy of high-falutin,'

and spread-eagleism, and social slang. 'First-rate,' 'prime,' 'a prime article,'

'a superior piece of goods,' 'a gent in a

flowered vest;' all such expressions are final. They blast the

lineage of him or her who utters them, for generations up and down.

He tells them that 'good-breeding is surface Christianity.' He

slyly consoles them with the thought that 'good Americans when they

die go to Paris.' He is thoroughly national himself, and would

have American patriotism large and liberal, not a narrow provincial

conceit. The 'autocrat' is assuredly one of the pleasantest

specimens of the American gentleman, and one of the most charming of all

chatty companions; genial, witty, and wise; never wearisome. We

fancy the 'Autocrat of the Breakfast Table' is not so well known or

widely read in this country as it deserves to be. A more

delightful book has not come over the Atlantic.

We have reserved Holmes to the last, not

that he is least amongst American humourists, but because he brings

American humour to its finest point, and is, in fact, the first of

American Wits.

Perhaps the following verses will best

illustrate a speciality of Holmes's wit, the kind of badinage

with which he quizzes common sense so successfully, by his happy paradox

of serious straightforward statement, and quiet qualifying afterwards by

which he tapers his point.

|

CONTENTMENT.

'Man wants but little here below.'

'Little I ask; my wants are few;

I only wish a hut of stone

(A very plain brown stone will do),

That I may call my own;—

And close at hand is such a one,

In yonder street that fronts the sun.

Plain food is quite enough for me;

Three courses are as good as ten;

If Nature can subsist on three,

Thank Heaven for three. Amen!

I always thought cold victuals nice,—

My choice would be vanilla-ice.

I care not much for gold or land—

Give me a mortgage here and

there,

Some good bank-stock, some note of hand,

Or trifling railroad share,—

I only ask that Fortune send

A little more than I shall spend.

Honours are silly toys, I know,

And titles are but empty names;

I would, perhaps, be Plenipo—

But only near St. James;

I'm very sure I should not care

To fill our Gubernator's chair.

Jewels are baubles; 'tis a sin

To care for such unfruitful

things;—

One good-sized diamond in a pin,

Some, not so large

in rings,

A ruby, and a pearl, or so,

Will do for me;— I laugh at show.

My dame should dress in cheap attire

(Good heavy silks are never dear);

I own perhaps I might desire

Some shawls of true

Cashmere,—

Some marrowy crapes of China silk,

Like wrinkled skins on scalded milk.

Wealth's wasteful tricks I will not learn,

Nor ape the glittering upstart fool;

Shall not carved tables serve my turn,

But all must be of

buhl?

Give grasping pomp its double care,—

I ask but one recumbent chair.

Thus humble let me live and die,

Nor long for Midas' golden touch;

If heaven more generous gifts deny,

I shalt not miss them much,—

Too grateful for the blessing lent

Of simple tastes and mind content!'

|

Having had our

laugh at Yankee humour, let us glance at what it tells us

seriously. In the first place it is morally healthy and

sound. It has its coarsenesses, though these lie more in the using

of a word profanely than in profanity of purpose. It has no

ribaldry of Silenus, nor is there any leer of the satyr from among the

leaves. We perceive no tendency to uncleanness. Fashionable

ladies of the New York 'upper ten thousand' may be French at heart

in the matter of dress and novel-reading, but the national humour does

not follow the French fashion; has no dalliance with the devil by

playing with forbidden things, no art of insidious suggestion. In

this respect it is hale and honest as nature herself and it is just as

sound on the subject of politics. Disgust more profound, scorn

more scathing, than Lowell expresses for the scum of the national

intellect thrown up to the political surface by the tumult and fierce

whirl of the national life, could not be uttered in English. He

tells the people they cannot make any great advance; cannot ascend the

heights of a noble humanity cannot reach the promise of their new land

and new life; cannot win respect for self nor applause from others,

|

'Long'z

you elect for Congressmen poor shotes thet want to go

Coz they can't seem to git their grub no otherways than so,

An' let your bes' men stay to home coz they wun't show ez talkers,

Nor can't be hired to fool ye an' sof'-soap ye

at a caucus,—

Long 'z ye set by Rotashun more'n ye do by

folks's merits,

Ez though experunce thriv by change o' sile,

like corn an' kerrits,—

Long 'z you allow a critter's "claims" coz,

spite o' shoves an' tippins,

He's kep' his private pan jest where 't would

ketch mos' public drippies—

Long 'z you suppose your votes can turn biled kebbage into brain,

An' ary man thet 's pop'lar 's fit to drive a

lightnin'-train,

Long 'z you believe democracy means I'm ez good ez ,you be,

An' thet a felier from the ranks can't be a

knave or booby,—

Long 'z Congress seems purvided, like yer street cars an' yer 'busses,

With ollers room for jes' one more o' your

spiled-in-bakin' cusses,

Dough 'thout the emptins of a soul, an' yit with means about 'em

(Like essence-pedlers**) thet'll make folks

long

to be without 'em,

Jest heavy 'nough to turn a scale thet 's

doubtfle the wrong way,

An' make their nat'ral arsenal o' hem' nasty

pay.' |

The war has

taught the Americans many lessons, but it was only driving home, and

clenching in some places, what their writers had been telling them

beforehand. For example, that it is man, manhood, not multitude,

which leads the nations and makes them great. They were made to

learn, through a long and painful struggle, the helplessness of hands

without head.

But this was what their best instructors had

already insisted on. And, in the midst of the fight, Lowell cries

to his countrymen,—

|

'It

ain't your twenty millions that 'll ever block

Jeff s

game,

But one man thet wun't let 'em jog jest ez

he's takin'

aim.' |

And again, in answer to the continual call for more men,

he says,—

|

'More men? More Man! It's there we fail;

Weak plans grow weaker yit by lengthenin':

Wut use in addin' to the tail,

When it's the head 's in need of

strengthenin'?

We wanted one thet felt all Chief,

From roots o' hair to sole o' stockin',

Square-sot with thousan'-ton belief

In him an' us, ef earth went rockin'!' |

We have always

believed that there were better things at the centre of American life

than were made conspicuous on the surface. We knew there were

Americans who had not the popular belief in 'buncombe,' who had the

deepest contempt for the 'tall talk' of their newspapers, and on

whom the sayings and doings of their countrymen inflicted

torments. Human nature in America is somewhat like the articles in

a great exhibition, where the largest and loudest things first catch the

eye and usurp the attention. Also, their system of representation

gives the largest and loudest expression to the, grosser human interests

in the political sphere; it aggregates a huge mass of ignorant

selfishness, such as is not swiftly or easily touched with the fine

thought or noble feeling of the few. For instance, the writers of

America who represent its moral conscience, are in favour of an

international copyright; they are on the side of right and justice, in

opposition to those who represent, only the political conscience of the

country. But their difficulty is in bringing their momentum

to bear upon the political machine, seeing that they cannot work

directly through it. With us the apparatus is far more delicate

and sensitive, and the chances of representation for the truer feeling

and higher wisdom are infinitely greater. Nevertheless it is

satisfactory to find—and the finger-pointings and the smile of Yankee

humour help greatly to show it—that there is among the Americans a

stronger backing of sound sense, of clear seeing, and of right

feeling, than we could have gathered any idea of from their political

mouthpieces.

GERALD MASSEY. |