|

|

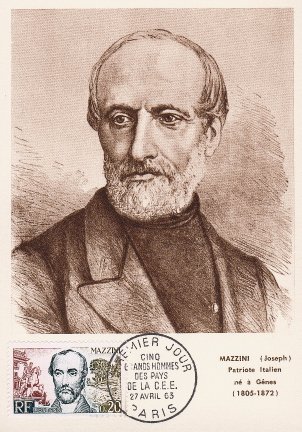

GIUSEPPE MAZZINI

(1805-82) |

THE rarest produce of this world of ours is not its mines of ore, its jewelled Indies, its fruitful lands and overflowing granaries; but its great hearts and great minds, these are its riches beyond price.

The great and veritable history of this world, also, is to be found written in the lives of its noble women and great men.

If it were possible to cancel the existence of those Greek and Roman heroes whose lives and deeds are chronicled in old Plutarch, with the chief

painters and sculptors, and writers of ancient Greece and Rome, how miserably

mean would be the remains of those illustrious nations! Or try to fancy our own England without its Alfred, Shakspere, Milton, Newton,

Coeur de Lion, Elizabeth, Bacon, Caxton, Watt, Cromwell, Nelson, and some others who have wielded sword and pen, or thrown the inkstand at the head of the Devil Ignorance!

You cannot realize it. England would not be England with out them.

Nor could any number of small men and mediocrities supply their fill their spheres.

I am somewhat of a hero-worshipper, and think it good to venerate the heroic.

To believe in the heroic tends to make heroes, for men grow into the likeness of that which they look upon.

I do not advocate that we should cling to the glittering skirts of great men to the abnegation of our own self-reliance and personality, but with a loving trust in their superior strength, and with an admiring and worshipful recognition of the divinity that is within them, and shines through them, and flashes from them, in wise speech and noble deed.

We should look up to them as to our elder, wiser brothers, by sympathy to grow with their growth, and be lifted toward their loftier stature.

For not only do they bring the gods down to us, but they, exalt us to the gods.

The veriest dwarf may increase the length of his stride as he walks on his life journey by earnestly endeavouring to track the footprints of the giants who have gone before.

It is from the lives of great men that we shall get the rarest glimpses of the divine significance of life and the glorious promise and unfathomable possibilities that lie in our human nature.

Great men have spoken their 'bravo sublunary things,' done their heroic deeds, and lived their grand lives, that we may also become great.

Let us learn to love and reverence them, and we shall not fail to comprehend them: for love is such a luminous revealer and tutor that it makes us like the uneducated woman who is mated to an intellectual husband, and who understands him and climbs to the height of his character in the light and strength of her great love.

But where shall we find our great man, our hero, in these days of small things?

Live there now such men as have glorified the past? Yes: great men are among us to-day; great men are standing on the threshold of this 'our wondrous mother age.'

They are walking in our midst, although our minds may not be large enough to mirror their altitude.

It has been said that no great man is a hero to his valet, but surely the reason lies more in the valet's want of insight than in the hero's want of noble attributes.

Who that has marked the life and watched the work of Joseph Mazzini will gainsay that he is a great man and a true

hero—a genuine worshipful Presence? He is a man who, in an age of dwarfs and pigmies, has attained something like the old Roman stature of soul, the old Roman force of intellect and bravery of heart.

He is a man of the kingliest faculties. As a man of thought and deed combined, he is second to none that we have heard

of. Mazzini is the son of that glorious mother of greatness, ITALY.

Italy! that makes the heart leap up and the eyes brighten at the mention of her name.

Italy! the loved and the lovely, the everliving Eden of the world.

Italy! with its peerless wealth of genius, its hallowed shrines of art for passionate pilgrims, its glittering host of glorious men, and its long array of martyrs.

Italy! that stands before the world its best glory and worst shame, the victim of innumerable

wrongs—that is not and never can be a slave in spirit, though the Austrian fetters hang heavy on her chafed limbs.

Italy is the nursing mother of Mazzini, who is the fitting child of such a parent.

I do not intend to make this article a biographic sketch, but will jot down in it something about the man, and his work, which is the redemption of Italy.

Mazzini is the worthy son of the country which has borne the Gracchi, Cato, Brutus, Marcus Aurelius, Cicero, and Cincinnatus; Dante and Titian; the sweet and gracious Raphael and massive Angelo; the martyred Bandiera and that poor boy the son of a washerwoman, the plebian humbler of patrician pride, the man who kindled the fire of freedom into such a blaze in old Rome that lighted the whole world,

RIENZI. Indeed he is a modern Rienzi. There are some noticeable points of resemblance between Cola de Rienzi and Joseph Mazzini.

There is in both the same early and ardent devotion of their lives to the emancipation and regeneration of their beloved Italy, the same persistency in carrying out a cherished idea, the same self-sacrifice, the same breadth and grandeur of character, the same self-reliance in action, and

proud bearing under defeat. History sometimes repeats itself, and it would almost seem that, in the person of Mazzini, Rienzi had revisited the earth, sadder and wiser through subliming suffering, stronger through stern experience, to accomplish the work begun five centuries ago.

Both have been inspired with the one idea of uniting Italy into a vast Republic, one and indivisible, with Rome for its proud head.

Both have alike been thwarted by petty princes and royal robbers, who have parcelled out Italy that they may conquer piecemeal and murder in detail.

Both have spent some of the best years of their lives in exile; and both have had one glorious grip at the throat of their country's oppressors, though Mazzini's hold was all too brief.

Both went into exile a second time: but here let the parallel end.

Not but what Mazzini will return a second time to reign, even as Rienzi did: he will return, he shall return, but the victory will be nobler, the end more glorious.

Our Rienzi is wiser by the experience of five hundred years, and he will not fail to pluck the fruit that is ripening within his reach.

Who doubts that Mazzini shall yet triumph that has watched the course of his

life—whether nursing his studious youth with traditions of Roman virtue, kindling his soul with visions of Italy's coming glory, inspiring Young Italy with his own great love of country, working on with patient endurance through partial defeat, and through long years of martyrdom bating no jot of heart or

hope,—or in that proud straggle for Rome, Italy and Liberty, in 1849?

Did you mark his heroic toil, his unblenching endurance of suffering?

Did you see how calmly and how grandly he dilated to fill the emergencies of that grim crisis?—how gallantly he rode the waves of adverse circumstances?—how firmly and untremblingly he stood beneath the burden of his great cause, and supported a weight that must have crushed a lesser man?

And yet it was so like him, and came so naturally to him, as though he had been born for it.

Mazzini is one of the clearest and deepest Seers of our time. He has a hand which is as prompt to execute as his thoughts are quick to conceive.

He has the self-reliance which can stand alone against the whole world.

He has the earnestness which claims victory as its own high prerogative by natural right.

What Cecil said of Raleigh is applicable to Mazzini—he can 'toil terribly.'

He has what Napoleon called the 'two-o'clock-in-the-morning' kind of courage, or rather he keeps eternal watch.

He is generous and magnanimous to a fault, if that be possible.

Mazzini is the prophet, teacher, and inspirer of a Faith, not a tailoring or tinkering systematizer of details.

He is a leader in the vanguard of Humanity, and you must not expect to find him looking after the commissariat in the rear.

Others will do that: and every one to his work, and the tools to him who

has the peculiar art to handle them!

Mazzini had no such lease of power in Rome as Rienzi

had. Yet for the time and opportunity he worked wonders and

performed the utmost of human possibility. Through all that tragic

struggle he was to be found everywhere, cheering, directing, organizing,

inspiring. Who forgets his thirty days and nights' toil—his

self-sacrifice, his sublime faith in the heart and energies of the

people, and that heroic bearing of his which seemed to exalt those who

looked upon him into a race of heroes inspired with the prescience of

victory, so contagious was his calm courage?

All this and more will be found treasured up for Immortality, when the History of Heroism shall come to be written, and will form one of its sublimest chapters.

Grand, clear, and lovely does the character of Mazzini shine out in the expiring light of that Roman Revolution!

Here is a graphic picture of him after all was over, by one who knew him well, and who laboured with him in the glorious struggle, poor Margaret Fuller!

'Mazzini has suffered millions more than I could. When the French entered, he walked about the streets to see how the people bore themselves, and then went to the house of a friend.

In the upper chamber of a poor house I found him with his life-long friends the Modenas.

Mazzini had borne his fearful responsibility: he had let his dearest friends perish; he had passed all these nights without sleep; in two short months he had grown old; all the vital juices seemed exhausted; his eyes were all blood-shot, his skin orange: flesh he had none: his hair was mixed with white: his hand was painful to touch.

But he had never flinched, never quailed, had protested in the last hour against surrender: sweet and calm, but full of a more fiery purpose than ever: in him I revered the Hero, and owned myself not of that mould.'

When all was over in Rome, and the torch of liberty which he had kindled was extinguished, Mazzini left for Marseilles, and from thence he went to Lausanne, in Switzerland.

It was here he wrote his crushing letter to De Tocqueville, De Falloux, and Montalembert, the Jesuitical crucifiers of Rome's young Republic, convicting them of the most dastardly lies, and heating the branding-iron seven times hot in the forge of his mighty intellect, wherewith History shall set the mark of Cain on their foreheads.

Various other eloquent works have been written by him, and the State-papers of Mazzini are the noblest political manifestoes in the archives of Europe: there is nothing of the kind approaching them for heart or earnestness, save a few which emanated from the English and French Revolutions.

Mazzini is one of the few unsuccessful great men that are not used up and killed out by defeat.

It is difficult for the world to see the hero in the unsuccessful man.

But Mazzini has stamped his impression upon it as indelibly as the image of a king upon the coinage from his mint, and all the tricks and artifices of his enemies cannot deface the heroic features.

The world still believes in Mazzini, and the tyrants tremble in their triumphal cars at the mention of his name.

When he speaks, one half the world listens and gathers up his words to run post for him.

His hair has turned grey; he is, among men, a king of sorrows, crowned with scars.

But his eye of faith is bright as ever, and lifted with as sublime a confidence; his hope and heart are steadfast and unshaken still.

As Napoleon said of Massena, we may say of Mazzini, he never was so much himself, or so great, as when the battle went the sorest against him, when be rose up in all the magnitude of his might, his roused soul put forth its rarest energies, put on the robes of victory, and went forth to conquer.

Mazzini still lives; and looking upon his past who can doubt that there is a great future in store for him?

Italy is not dead, and has not said her last word. True, she lies hushed as in the silence of the grave.

True, her martyrs are sleeping in their bloody shrouds, or are led out day by day to fall by the Austrian or Swiss bullet.

True, it is midnight in Rome, and the owls, and bats, and creeping things of priests are out on their soul-murdering errand.

True it is that the reaction reigns rampantly, that Rome, Milan, Berlin, and Hungary wear the gyves and fetters as tightly as of old, with no token of life save a death-cheer or a groan.

True, that France has swerved from the lofty purpose which beat in her heart and brain and nerved her arm in '48.

But for all these things we will not despair. The battle goes sorely for the soldiers of freedom, but it will make the grand triumph more signal and bright. Nor for long shall Priest, Pope, and Cardinal darken the sunny homes of Italy with their presence.

But we are forbidden to speak of Italy now. We are in league with Austria, our natural ally! Austria, false as hell, cruel as hell, and whom we hate with the hate of hell.

And do Englishmen suspect the price we pay for Austria in this Russian war?

It is that we are not to permit Italy and Hungary to rise! That is the bond, as sure as death.

In the face of present circumstances, the apathy of Englishmen, and the cunning of secret diplomacy, we have but one consolation.

It is this. Our statesmen are not altogether the arbiters of fate, and absolute decreers

of events. At any moment they may quarrel among themselves.

The brotherhood of wrong and robbery is but a weak bond. And at

any moment the popular forces may explode in revolution. England

is silent about Italy, but we mean Italy, and Hungary, and Poland, in

every cry we hurl at Russia. We mean Italy, and Hungary, and

Poland, in every cheer we send to the Turk! GERALD MASSEY. |