|

[Previous Page]

ROGER BELL. |

|

OF all my good and faithful friends,

But few I loved as well,

As the subject of my humble song,

The good old Roger Bell.

Oft have we, at the close of day,

When all our work was done,

Together climbed some lofty hill,

To watch the setting sun.

Old Roger was a thoughtful man,

Of cultivated mind;

And in the meanest things of earth.

Some lesson he could find.

He loved whatever God hath made,

In earth, in air, and sky;

Nothing appeared too mean for him,

And nothing seemed too high.

The modest daisy at his feet:

The dew-drop on the grass;

The tiny insect on the leaf,

He did not idly pass.

To him each dull and passing cloud

Was something to admire;

When musing on the works of God,

He never seemed to tire.

At early dawn, with stick in hand,

This veteran might be seen,

Pacing with feeble steps and slow,

Around the village green.

And, oh! to me it was a treat,

This good old man to see,

When seated at his cottage door,

With the Bible on his knee.

The thin, grey locks upon that head,—

That broad and thoughtful brow,—

The gentle look and well-known voice,

I well remember now.

I saw him on the day he died,

And o'er his corpse did bend;

My heart was full; my tears came fast;

For I had lost a friend.

We saw that pale and wasted form

Enveloped in the shroud:—

Beheld his children o'er him stoop,

And weep, and sob aloud.

We bore him to the silent grave;

Few cheeks that day were dry;

And, tho' the village mourned his loss,

None felt it more than I.

Now lone and sad, I move along,

Among the haunts of men;

And wonder when my friend and I

May hope to meet again.

I've lost a many valued friends,

Relations, too, as well;

But none for whom I sorrow more

Than good, old Roger Bell! |

|

_______________________________

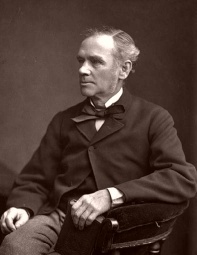

TO HUGH MASON, ESQ., M.P. |

|

(1817-86) |

|

A philanthropic and paternalistic mill owner and politician, Hugh Mason

was a passionate Liberal and Nonconformist. His philanthropy and

radical approach to the care and welfare of his workers earned him respect

amongst the working classes, but considerable opposition from other

mill-owners who saw his "charitable extravagances" as a threat. He

was to become an instrumental supporter of factory reform. He was

mayor of Ashton-under-Lyne from 1857-1860 and its M.P. from 1880-1885, a

period during which the town saw great improvements. In 1861 the

Infirmary was opened; in 1862 the Albion School; in 1870 the Public Baths;

Stamford Park in 1873; and the Library in 1882. Improvements were

also made in housing conditions and in most cases Mason's influence was to

the fore. During the

Cotton Famine of

1861-1865 he refused to cut workers' wages, despite it being common

practice in other mills in the district—he also contributed £500 to the

Ashton Borough Cotton Famine Relief Fund. Mason died in 1886,

becoming the only local industrialist to have a monument erected in the

town in his honour by public subscription. (See also HUGH

MASON). |

|

MY Dear Sir,—

May I ask you to kindly excuse

A few simple thoughts from a homely muse.

And as I now write to a Parliament man,

I will make this epistle as brief as I can.

Allow me to say I am gladdened to see,

That the people of Ashton have made you M.P.

'Tis an honour well-earned, and most richly deserved

An acknowledgment, too, from the party you've served.

That grand scene near Jerusalem comes fresh to one's mind—

Where Christ rides in triumph; the people behind

Waving branches of palm trees along the highways,

And rending the air with hosannas of praise!

But, alas! for our frail human nature!—next day

The very same people cried "Take him away!"

But at Ashton it seems the whole thing was reversed,

They grave you the thorns and the crucifix first.

We remember the time, and now pen it with shame,

When the spirit of hate sought to tarnish your name;

But your foes were frustrated in all they could do,

And were hung on the gallows intended for you.

But the eyes of the people were opened, and now,

Instead of the thorns there's a crown on your brow!

And those who were harsh and unkind in those days,

Now load you with honours, extol you with praise.

The cross came first, while the crown was delayed;

The bright glowing sunshine came after the shade;

And we hope these dark shadows will haunt you no more,

But that brighter and happier days are in store.

May your life long be spared, and the powers of your mind

Employed in the cause of your God and mankind.

Gird your armour afresh, Sir, and manfully fight,

For freedom to all men, for justice and right.

We call ourselves Christians, and wet up the sword,

To murder and rob in the name of the Lord.

O Christ! it is men of thy pattern we want,

To expose this barefaced, hypocritical cant!

Where are all the grand saints!—we need Cromwell again,

With his high-souled adherents, his broad-shouldered men.

We need brave John Milton, that Master of Song,

To denounce this impurity, bloodshed, and wrong!

The priests and the Levites still grasp after wealth,

And the gods that they worship are Mammon and self.

We may boast and feel proud of these dear British Isles,

On which it is said a kind Providence smiles;

But what will yond poor despised savages think

Of the freedom of those who are slaves to drink!

I have long been considered an "ill-natured thing,"

For fiddling and scraping so much on one string.

Still, I've faith to believe that the seeds we have sown,

Will firmly take root;—that our Father will own

These earnest endeavours the people to bless,

And crown them at length with a glorious success.

And I venture to hope I shall yet live to see

The drink traffic crushed, and poor drunkards set free.

I have long been devoting my own humble powers,

To pluck up the weeds, and replace them with flowers.

And I know that the weariness, heart-aches, and pain,

Have not been endured altogether in vain.

Oh, no! for behold! on the far distant hills

The morning is breaking! The sparkling rills,

As they stream down the mountains are silvered with light,

And these streamlets strike out to the left and the right,

Gaining swiftness and strength as they rush on their way,

Till at length they arrive in the great open bay!

So with our noble cause; we have toiled through the night,

And already the mountains are flooded with light;

The day-star of Temperance is now shining clear,

And silently telling us victory is near.

Come, thou with pale face and impoverish'd blood—

Who hast worn out thy life for thy country's good—

Step out to the breeze, bare thy brow to the sun!

And join in the shout, "The great battle is won!"

Excuse me for tiring your patience so long;

I've been tempted to ramble a bit in my song,

But I wanted to state in a plain humble way,

What has been in my cranium for many a long day—

Namely—congratulate you, at this distant hour,

On your upward advance to distinction and power.

And tho' this small trifle may seem out of date.

Perhaps you will pardon me sending it late.

By way of excuse, just allow me to say,

That I've purposely caused this protracted delay;

For I did not desire to appear as a pest,

At a time when I knew you must wish for some rest.

But, now that you've leave to absent from the House

To make speeches, read letters, write books, or shoot

grouse—

I thought one might venture to scribble a song,

And say what has been in reserve for so long.

I remember last Spring, when the telegram came,

To say that M.P. had been placed to your name—

You will think I was greatly excited, of course—

But I actually shouted until I was hoarse!

When I got to my home, our dear girl—ten years old—

Said "Dada! you seem to have got a bad cold."

"Bless thee, child," I replied, "I've been shouting for fun,

Because of the victories the Liberals have won!"

Well, I see they have christened you "Member for Hurst;"

Now, I do not profess to be very well versed

In matters like these; still, I venture to say

That the Banker would jump at your shop any day!

Never mind their bad temper, their venom and spite,

Still hoist up the standard of justice and right;

And when in the future the goal shall be won,

May you hear the glad sound of the Master's "Well done!" |

|

_______________________________

TO AN UNKNOWN FRIEND, ON RECEIVING

FROM HIM SOME VERSES ENTITLED

"WORDS OF CHEER." |

|

I know not who thou art, my friend,

But thou art well-disposed, 'tis clear;

How very kind of thee to send

Such soothing words, such words of cheer.

Art thou acquainted with my grief;

Ah, me! I've lost a faithful wife;

And I have none with me to share

The sorrows and the sweets of life.

Bereft of one to me so dear,

No wonder I am lone and sad.

Alas! alas! she is not here

To cheer my soul, or make me glad.

I do not wish to pine or fret,

Or doubt the goodness of my God;

I try to check my grief; and yet,

'Tis sometimes hard to kiss the rod.

'Tis hard to see our friends depart,

To see them from our presence borne;

And O! what sorrows fill the heart

To think that they shall ne'er return.

Dost thou admire me? then I feel

I have not wrote or sung in vain;

And, if these wounds of mine should heal,

I'll try to pen some nobler strain.

I'll try to tune my harp once more,

My silent harp, now laid aside,—

And wake its music as of yore,

Ere my, beloved partner died.

And since I know not who thou art,

These lines may never reach thine ear;

But, oh, I thank thee from my heart;

God bless thee for those "Words of cheer." |

|

_______________________________

BEWARE! FOR THE CLOUDS ARE GATHERING. |

|

BEWARE! for the clouds are gathering,

And the rumbling noise that we hear

Is the murmur of suffering people,

That tells us a storm is near.

Shall we dare to despise this warning,—

Pressed upon us again and again?

Beware of the sullen storm-clouds,

On the brows of desperate men!

We may boast of our vast dominions

Of our national wealth and might;

But be sure that God and the People

Will be found on the side of Right.

When the storm-clouds burst in the heavens,

And the fiery bolts descend,

The proudest hearts will be shaken,

And the reign of oppression end.

Why all this magnificent splendour

Adorning the halls of the rich,—

While the toilers who made them their fortunes

Are pining away in the ditch?

Must the masses be beggared, in order

To bolster up kingdoms and thrones?

Are the bees to be forced into silence,

While the honey is eaten by drones?

Who amongst us are found most deserving?

The labourers delving the soil?

Or the inhuman, land-grabbing tyrants,

Who fatten and feast on the spoil?

Are these to have British protection,—

Their halls and their lands made secure,—

While bludgeons, and cowardly insults,

Break the heads and the hearts of the poor!

Who gave these proud lordlings their mansions,—

The riches with which they are blest?

Who bribed them to use their great influence,

In crushing the weak and oppressed?

Were these business transactions done fairly?

Do they add to our honour and fame?

Ah, no;—but quite the contrary,—

To our lasting dishonour and shame!

Shall England still swagger and bluster?

Is the world given up to our care?

If so, why not bottle the sunshine,

And peddle it out with the air!

Look out, for the clouds are gathering!

Yes, gathering on poor men's brows;

Beware of the pent-up feelings

Which your heartless acts may arouse!

Feast on, ye proud Belshazzars!

Let joy fill the banqueting hall;

But be sure of this—that God's finger

Is writing upon the wall!

Go on with the feast, but remember

That while you are feeding your pride,

The storm-clouds are ready for bursting,

And Lazarus is starving outside.

What is it we hear from Old Ireland?

The children's innocent songs?

Oh, no! 'tis the down-trodden, groaning;

Yes, groaning beneath their wrongs.

Her patriots and priests are in prison;

Her sons and her daughters in tears;

And yet we have men so degraded

As to mock them with jibes and jeers!

How long shall this conflict continue;—

This war between Wrong and Right!

And when shall the weak be successful

In their struggle 'gainst Wealth and Might!

Take heed to the gathering storm-clouds,

And the writing upon the wall;

For pride goes before destruction,

And the haughty in spirit must fall! |

|

_______________________________

A FATHER'S LAMENT FOR HIS ABSENT SON. |

|

THANK you the same, but while that chair is vacant

Your kindly wishes must be all in vain;

For while the wandering one is absent from us,

I cannot join you in the merry strain.

Here we are met, 'midst scenes of peace and comfort;

The lamps are lit, the fire is burning bright;

But such a festive scene must needs remind us

That one is absent. Where is he

to-night?

Cold hearts still ask I "Am I my brother's keeper?"

Their laugh is merry as they sip the wine;

But how can I, a sickly, sorrowing father,

In such gay sport,—in such amusement join!

My mother, with her latest breath, besought me

To make this first-born son my special care.

His mother, too, in her last painful moments

Made him the subject of her dying prayer.

And yet, a father's heart needs no reminders

From dying lips, long, long ago at rest.

How can a bird forget its absent fledgling,

Or gaze unmoved on the forsaken nest!

Say you my boy's unsteady,—fond of roving?

Leaving his lawful duties here undone?

It may be so; but I am still his father,

And he, the prodigal, is still my son!

Is he the only one who introduces

A note of discord into this our song?

Are all the others innocent and blameless?

Is he the weak one? all the others strong?

If so, I point you to the gentle Jesus

Who were the characters to whom He clave?

The Pharisee,—the wealthy, vain, self-righteous?

Or was it sinners that He came to save!

Gather your robes about you, O ye virtuous!

Spurn the poor brother crawling in the dust;

Boast of your piety, but please remember,

That He who holds the balances is just!

And who are we, that we should sit in judgment!

Are we all perfect?—all our actions pure!

Have we no faults to hide?—no secret failings?

Does all the filth lie at our neighbour's door?

On with the dance, all ye whose hearts are merry!

Bring to your banquet beauty, wealth, and wine:—

All who can drown their sorrows in their pleasures;—

But, for the present, don't ask me to join.

Deem it a weakness, if it so should please you;

All my good feelings ridicule and spurn;

Still, I must wait with saddened heart, and joyless,—

Wait for the absent prodigal's return!

I like the ring of hearty, merry laughter,—

The harmless frolic and the sober jest;

But cannot take a part in the enjoyments,

This festive season brings, with proper zest.

This being so, perhaps you'll please excuse me,

If my cold manners seem to cast a blight

On what, to you, are lawful, healthy pleasures;

And more so now, on this glad New Year's night.

My thoughts are wandering o'er the great Atlantic,

Where one we love may now be sat alone;

And, while we rest our weary frames in comfort,

His only bed to-night may be a stone!

Excuse me, then, if I may seem unsocial,

Or sit in silence when the cup goes round;

I cannot form a link in this dear union,

Until the chain's complete,—the lost one found! |

|

_______________________________

AN APPEAL ON BEHALF OF SUNDAY SCHOOLS.

READ AT A BAZAAR AT OSWALDTWHISTLE. |

|

AT the outset, I think I can truthfully say,

That it gives me much pleasure to meet you to day,

And take—though it may be a very small-part,—

In promoting the object we all have at heart.

Sunday Schools are our nurseries,—Eden-like bowers,

Where we keep our most cherished,—most beautiful flowers;

The training-ground, where our young saplings must grow,—

Have their minds stored with truths it is well they should know.

We see from the programme that one of your wants

Is more room for the health and the growth of these plants;—

Where the sunshine must enter, and strike at the root,

Ere the saplings can thrive or put forth their fruit.

For though not skilled farmers, we all of us know

That seed must have room or it never can grow.

Let us hope that those present their duty won't shirk,

But see that our friends are not cramped in their work.

For I hardly need say—neither wise men nor fools

Can build, if they have not materials and tools.

But I must not thus needlessly take up your time,

And I need not appeal to your reason in rhyme.

As a stranger, perhaps you'll allow me to say,

That for what little help I may give you to-day—

I must thank my dear parents, who made it a rule,

That their children should go to the Sunday School.

The good lessons there learned I shall never forget,

And the hymns have a place in my memory yet;

I name this to shew that the seed you may sow

In the minds of the young will assuredly grow,

And gladden the hearts of the reapers, we trust,

When the hands of the sewers have crumbled to dust;

We labour in faith, and our eyes may not see

The struggling blade as it strives to be free;—

But obstructions will vanish; and, bursting to bloom,—

The sweet flowers will repay you with grateful perfume.

We are reaping to-day what was sown in the past,

And the fruit so long looked-for has ripened at last.

Yes, the men who are served, and the women who wait;—

The great minds that now guide the affairs of the state,—

These are all the results of the care and the toil

That our fathers bestowed on the virgin soil.

It is our turn now, and the world looks on,—

Not only to thank the grand souls that are gone,—

But to see if we quit ourselves well in the fight,—

For God, for humanity, justice, and right.

Then let us so build, that in years to come,

Our children may meet in a beautiful home,

And sing once again the old hymns that were sung

With such pleasure and profit when we were young. |

|

_______________________________

OH! THIS RAIN! |

|

OH! this rain, rain, rain;

It has rained all afternoon;

I have tried, but tried in vain,

To strike up a merry tune.

I have sought relief in books,

Culled thoughts from the brightest, best;

But my jaded and restless looks

Proclaim the mind's unrest.

I long for the sun's bright beams,

To come and dispel the gloom

That gathers around my dreams,

As alone I sit in my room,

And think of the days gone by

When my pen had the power to charm,

When I basked 'neath a cloudless sky,

And the hearts of my friends were warm.

And wherefore now are they cold?

And why do my warblings tire?

Has my Muse, like myself, grown old?

Is there nothing left to admire?—

No flashes of humour or wit,

Such as tickled my readers of yore?

Is the striker now powerless to hit?

Is the lion unable to roar?

Who dares to approach my den!

Who dares to enslave my mind!

Can ye silence the angry waves?

Have ye power to control the wind?

Do men look out at night

Expecting the sun to shine?

Or have I complete control

Over these poor thoughts of mine?

Oh! this rain, rain, rain!

Will it never, never cease!

Must I seek relief in vain,

For a mind so ill at ease!

Must all my efforts fail?

Is there no bright cheering ray,—

No kind and friendly gale,

To chase the clouds away! |

|

_______________________________

AN ESSAY ON A COW. |

|

IT is said that a girl living out in the West,

On her knowledge of cows being put to the test,

Wrote the following essay, which surely will serve

To show that the girl had begun to observe:—

"A cow is an animal (that's not denied),

And has got four legs on the under side.

The cow, too, has got a long tail, you know;

But the cow doesn't stand on it—oh dear, no.

Now the animal under review is wise,

For it uses its tail for the killing of flies.

A cow has big ears, which she flaps like a sail,

And they wriggle about much and so does the tail.

The cow, too, is bigger a deal than the calf;

But a full-grown elephant's bigger by half.

The cow is so small (as they make them at Rooking)

That they get in the barn when there's nobody looking." |

|

_______________________________

A WINTER'S NIGHT AT BLACKPOOL. |

|

'TIS a wintry Sunday evening, I am here in the house

alone;

Outside, a storm is raging; the sea-god is on his throne,

And hark to the wind, how it whistles through keyholes and under doors;

While here,—confined in the chimney—the storm-fiend rages and roars!

Here I am surrounded with comforts; the lamps and the fire burn bright;

But what of my storm-bound neighbours who are out on the sea to-night!

And what of the wives and children with features sad and pale,

Whose hearts are struck with terror, as they list to the fearful gale!

The churches are open for worship; there the young and the old repair,

To listen to words of comfort, and join in praise and prayer.

From the pipes of the grand old organ are heard the sweetest notes;

While through every part of the building the sacred music floats.

Ah! listen again to the storm-fiend! how restless and reckless to-night!

Now drowning the voice of the preacher, now filling the hearers with

fright;

For they know from sad experience that many a tearful eye

Must have seen the last of their loved ones, and uttered the last

good-bye!

The gale increases in fury: huge billows are dashed on the shore;

And the angry elements clashing make a terrible, deafening roar.

The foam from the madden'd ocean is driven about on the Strand,

And the scene, as beheld from the shore, is exciting, and awfully grand.

The moon is now up in the heavens, and appears to look down on the sight;

But the clouds sailing o'er full of mischief, hide from us her silvery

light.

The stars—with but few exceptions—are hiding behind the clouds,

And,—like poor frighten'd children—are huddled together in crowds.

In the fishermen's cots, on the sand hills, where the turf-fires brightly

burn,

Warm suppers are waiting for loved ones who may never again return!

Oh! ye who are blest with riches, who can sit in your homes at ease,—

Do pity these seaside dwellers in trying times like these;

For many a loving father, and many a bright-eyed boy,

Have gone down with the ships that were bringing the comforts you enjoy!

And pity the widows and orphans who this evening are sitting alone,

And fancy that well-known voices are heard in the wind's sad mourn.

God help and protect the poor sailors, who,—out on this winterly night,

May be struggling for very existence, and getting the worst of the fight.

And ye who profess to be Christians, when down on your bended knees,—

Know you cannot petition High Heaven for braver men than these!

We read of the fields of battle, and the heroes in the strife;

But these go out as destroyers, and not as the savers of life.

The noblest deeds of daring, the deeds that all else eclipse—

Are performed by the large-souled sailors who "go down to the sea in

ships!" |

|

_______________________________

AT THE GRAVE OF JOSEPH COOPER.

["THE DERBYSHIRE BARD."] |

|

TO-DAY, 'neath the clods of the green graveyard,

We lay the remains of an aged bard;

A bard we have known and have honoured long,

For the lessons he taught by his life and song;—

For the pleasures experienced by those who might roam,

To see the old man in his "flower-fringed home."

But those days are past, we shall meet no more,

Till we join the glad throng on a happier shore.

His well-known cot on the brow of the hill;

The garden and posies are all there still;

But he has departed who graced those bowers,

And others must watch o'er the plants and flowers.

The pen he long handled is now laid aside;

The pictures and books that he looked on with pride

Will be squandered and pass into other hands,

And admired by the dwellers in far-off lands.

His neighbours will miss his well-known face,

And the children who lisped his simple lays

Will go with sad hearts and with tearful eyes,

To look on the grave where the old man lies!

Though death hath silenced the throbbing brain,

The thoughts that were born there still remain,

And take—though it may be—a humble part,—

In cheering many a sorrowing heart.

What joys and sorrows, what hopes and fears

Must have crowded a life-time of fourscore years!

And he oft must have stood with uncovered brow,

And mourned o'er some lost one, as we do now.

What a spot is this for the grave of a bard!

For the hills all around us seem placed as a guard,

To assure the thousands of sleepers here

That their beds are protected, so need not fear.

Good-bye, brother-bard! we shall meet again,

When the world shall have listened to my last strain;

When—as Waugh says—"Death has ta'en his tow,"

And my lips silenced, as thine are now! |

|

_______________________________

ON THE DEATH OF THE LATE RICHARD

OASTLER.

THE SUCCESSFUL CHAMPION OF THE TEN HOURS BILL. |

|

(1789-1861) |

|

For ten turbulent years

Richard Oastler trod the edges of revolution as a staunch campaigner against the

cruelties of the factory system and its exploitation of children.

Oastler was appointed steward to Thomas Thornhill's estate near

Huddersfield in 1820. In 1830 he met John Wood, a worsted

manufacturer from Bradford who agonised over the need to employ children

in his factory. Oastler wrote on the subject to the Leeds

Mercury. Having read the letter, radical M.P. John Hobhouse

introduced a child labour bill into Parliament that aimed to ban all

factory work for children under nine, and limit those between nine and 18

to 12 hours a day, 66 hours a week. But Parliament was dissolved

before the bill could be passed, and when reintroduced in 1831 it was

diluted to apply only to cotton factories and without any provision for

its enforcement. The 'short-time committees' that were now forming

in industrial towns continued the battle, Oastler becoming leader of what

became known as the 10-Hour Movement. He urged workers to use

strikes and sabotage to achieve their aims, while also campaigning against

the iniquities of the new poor law. This was too much for his

employer, Thornhill, who sacked him and called in unpaid debts.

Oastler, being unable to pay, was jailed for debt in December 1840.

It took his friends over three years to raise the cash, but on release

from the Fleet Prison, he returned to his campaign. Oastler achieved

limited success with the 1847 Factory Act, which restricted children to a

10-hour day in cotton mills, but it was not until 1867, 6 years after his death, that the Act was extended to cover children employed in

all factories. The statue of Oastler with two small children shown

above, the result of a national subscription, was unveiled in

1869 by the Earl of Shaftesbury, one of the great reformers for better

conditions for children. It is currently situated in Northgate, Bradford. |

|

WEEP on! weep on! a People's tears are due;

We've lost a friend, right noble, brave, and true.

No traitor he, to flatter, then deceive;

No, 'tis for honest worth that now we grieve.

'Tis meet and right that we our sorrows blend,

For Richard Oastler was the Poor Man's Friend.

Time, wealth, and influence—all he freely gave,

To snap the fetters of the Factory Slave.

O ye, who like myself were doomed to toil

In pent-up rooms, 'mid stench of gas and oil—

Bone, blood, and muscle, time and talent given—

Shut from the pure, the blessed air of heaven—

Think of the boon his pen and tongue secured,

The insults, jeers, and hardships he endured.

Think of the time when children, young in years,

Paced the dark streets, their eyes bedewed with tears;

Dragged from their beds, their labour had begun,

Long ere those eyes beheld the morning sun.

Their feeble limbs were clammy still with sweat,

When that bright orb had run his course and set.

No time for needful rest or healthful play,

On, on they toiled from weary day to day.

Their cheeks, once ruddy, now were sunk and pale,

And crowded graveyards told a mournful tale;

For, ere brave Oastler raised his arm to save,

Poor worn-out childhood found an early grave.

But, oh! a brighter day has dawned, and now

The youthful toiler wipes his sweaty brow,

And leaves his workshop at an early hour,

E're the cold dew hath shut his favourite flower.

The workman now, his daily labour o'er,

Can trim the garden at his cottage door;

Draw up his chair beside the chimney nook,

And spend an hour in poring o'er some book;

Or with the poet soar on fancy's wing,

And learn from him how sweet it is to sing.

Read how the man with patriotic zeal,

Gives time and talent for his country's weal;

How the philanthropist leaves home and friends,

And, like his Lord, o'er human frailty bends.

At close of day the labourer can repair

O'er hill and dale, midst prospects bright and fair.

Far in the west the gorgeous setting sun

Sinks to his rest like one whose work is done;

While from the eastern hills, the moon's pale light

Heralds her advent as the Queen of Night.

Above the head, the gold-tinged clouds are seen;

Beneath the feet, a carpet fair and green.

He hears the milkmaid chant her simple air,

The good old farmer offer up his prayer;

And he recalls to mind that happy day

When first his mother taught her child to pray;

And though she's dead, he thinks he sees her now,

With silvery hair smoothed o'er her wrinkled brow,

And hears that well-known voice say tenderly

"Prepare, my son, prepare to follow me."

He hastens home, a tear is in his eye;

But, though he weeps, his soul is filled with joy.

Dark brooding care that preyed upon his mind

Is now dispelled, and wisely left behind;

Gone is the downcast look and manner strange;

His evening's walk has wrought this happy change.

All honour to the men whose tongue and pen

Secured this precious boon to toiling men—

The leisure hour, the season doubly fair,

To roam the fields and breathe the balmy air.

Brave men were these—they toiled and laboured hard,

Until at length success was their reward.

A thousand blessings on thy hoary head,

Thou veteran "King!" What, though thy spirit's fled,

Thy name shall live amongst the good and brave,

And thousands yet unborn will seek thy grave

With grateful hearts, to drop a tear or two

On the green sod that hides thee from their view.

Crowd round his tomb, ye youths and maidens fair,

For, oh! a noble-minded man lies there!

When such an one as Oastler was departs,

His greatest monument is grateful hearts. |

|

_______________________________

MR. SOPKIN'S MISADVENTURES AT BLACKPOOL.

(After Ingoldsby's "Misadventures at Margate.") |

|

WHEN down at Blackpool last July, and walking on the

pier,

I met a pretty maiden, so I said, "How do, my dear?

What do you here, love, by yourself? How is it you're alone?

Come, tell me all about it now, and where your sweetheart's gone."

She smiled, as maidens always do, and turn'd her head aside;

Then walked along in front of me with some degree of pride;

And yet some outward signs of grief methought I did espy,

Her grateful bosom heav'd, and then she gave a deep-drawn sigh.

"Come, what's the matter with you now? Do tell me all," I

said;

"Has some one been deceiving you, or is your sweetheart dead?

Come, now, and don't be backward, dear, for I'm a single man,

And shall be very glad, indeed, to help you all I can."

The teardrops in her bright blue eyes I saw began to spring;

Again her bosom heaved, and, oh! she cried like anything.

At length her tongue found utterance. Her tale was brief, but

sad:

"I haven't got a sweetheart, sir—I only wish I had.

"My father's very cross to-day, and told me I must go,

And, ere I show'd my face again, be sure to get a beau;

I've walked along this very pier full twenty times or more,

Besides the many hours I've spent in walking on the shore;

"I'm quite as nice as Alice Jones, Miss Brown, or Lucy Young

They're all as proud as peacocks, these, (she had a rattling tongue!)—

If they're selected out for wives in preference to me,

I've made my mind up what to do—I'll jump into the sea!"

"Cheer up! cheer up! don't fret this way! cheer up!" I kindly said;

"You should not get such silly thoughts as these into your head:

If you should jump into the sea you'd certainly be drown'd,

And months might pass away before your body could be found.

"Come, take a walk along the shore—yes, come along with me—

I lodge a little way from here, they call it 'Number Three;'

My landlady will be within, her name is Mrs. Coe,

A very nice old lady, too—you'll like her well, I know."

She went with me to "Number Three," 'tis inland from the shore,

And as we entered in the house the clock was striking four;

I briefly introduced the maid, and then politely said,

"Two cups of tea, ma'am, if you please, and a little ham and bread."

But Mrs. Coe seemed rather cross, and made a little stir;

She said she'd gladly wait on me, but wouldn't wait or her;

She said I'd found her lying by, upon some dusty shelf,

And if I brought such hussies there, I must wait on them myself.

I did not speak, but took my hat, and called on Mr. Price,

And said, "A pound or two of ham, and please to cut it nice;

A half-a-dozen eggs as well, and let them be new-laid;"

I did not want them for myself as much as for that maid.

When I came back I gazed about, looked round on every chair,

But could not see my female friend—'twas plain she was not there;

I looked behind the parlour door, beneath the sofa too;

I said, "Oh, dear, my darling maid, why what's become of you?"

I could not see my best cloth coat, I could not see my hat;

My silver-mounted cane was gone, yes, even more than that;

My gold repeater, too, I missed, I left it on the wall,

But this was gone, and what was worse, my albert chain and all.

I could not see my potted shrimps, my nice black currant jam—

Both these were in the cupboard safe, when I went out for ham;

I missed my bran-new dressing case, 'twas on the sideboard laid;

My scent and hair-oil—all were gone, and so was that dear maid.

What could I do? I rang the bell, when in comes Mrs. Coe—

"Oh dear! oh dear! what do you think? ain't this a pretty go!

That modest-looking little maid, whom I brought here to-night,

She's stolen my things and run away!" Says she, "And serve you

right."

Next morning I was up betimes, and when I reached the town

I told the people whom I met that I would give a crown

If I could only find that maid who'd gone and served me so;

I was so vexed to hear a boy exclaim, "Poor simple Joe!"

I went along the promenade, a half-a-mile or more,

And looked at every girl I met or saw upon the shore;

I went into a coffee house, my doleful tale did tell,

And many persons seemed to think I'd not been treated well.

An oyster woman said she'd seen, that morning on the shore,

A—something funny—'twas a term I'd never heard before,

"A little forrud-looking puss," (dear me, what could she mean?)

"Wi' a set o' movable teeth in her yead, an' a pair o' roguish een."

She spoke about her being "spliced," and having seen her "sheer"—

It's very odd these oyster girls should talk so very queer—

And then she drew her brawny hand across her ruddy nose,

It's very odd that oyster girls should have such tricks as those.

I did not understand her well, but think she meant to say

She'd seen the maid I wanted catching snugly sail away

In Captain Slipham's Friendly Gale, about an hour before,

And they were now, as she supposed, some miles away from shore.

A donkey boy came up and said, "I know the duck you seeks,

The bobbies call her 'Hook-'em-od,'—she's been in gaol six weeks."

He said he thought she "hooked me od, and nicely twigged my clo'es,"

But I could scarce tell what he said, he talked so through his nose.

I went and asked the man in blue my property to track;

He said, "Now don't you wish that you may get it back?"

I answered, "To be sure I do, it's what I've come about."

He only smiled and said, "Sir, does your mother know you're out."

Not knowing what to do, I thought I'd go to Mr. King's,

And ask him if he'd catch the girl who'd gone and stole my things;

He very kindly said to me he'd try and find her out,

But hardly thought he should succeed—there were many such girls about.

He called Detective Twig'em in, and I sat down and wrote

A list of what I'd lost—my cane, my hat, and best cloth coat;

He said my wishes one and all should promptly be obey'd,

But never to this hour have I beheld that faithless maid.

MORAL:

Remember, then, what, when a boy, I heard my grandma say,

"Beware of strangers you may chance to meet with on the way."

Avoid loose girls who've got no home, but hang about the Pier,

Or they may rob you of your things, and, like this maiden, "sheer."

Well, now, don't mention this affair, or spread it through the town,

I do not want it to be known that I've been done so brown;

And when you go to Blackpool next, just stop and ring the bell,

Give my respects to Mrs. Coe, and say I'm pretty well. |

|

_______________________________

TO UNCLE MATTHEW. |

|

DEAR Uncle, we hope you arrived safe at home,

And feel none the worse for your "out."

You ought to be very much better, I think,

For a fortnight's good knocking about.

Oh! how sad and how sorry we all of us felt,

When this morning we bade you good-bye!

The tear-drops came silently out of our eyes,

And we fancy your own were not dry.

This is one of the shadows that darken our path,

As we wearily travel along;

We meet with the bramble as well as the flower,

And sadness is blended with song.

But away with reflection, for spring-time is near,

And the hedgerows will soon be in bloom;

Dame Nature will put on her holiday dress,

Spreading round her a grateful perfume.

Your springtime, your summer, and autumn are past,

And wintry winds blow on you now;

Your travel-stained limbs are beginning to tire,

While care-marks are seen on your brow.

Life's journey with you must soon come to an end;

We shall see you no more as a guest;

The heart that has throbb'd on for seventy-nine years,

Must soon be for ever at rest!

The garden at Hepworth you tend with such care,

Will seem quite deserted and lone;

The willows will weep, and the flowers will droop,

When Old Matthew the gardener's gone!

But this must not be yet, dear old Uncle, oh, no

For you have not yet cracked your last joke;

You have some of last summer's potatoes to eat,

And an ounce of good 'bacco to smoke.

God bless you, dear Uncle, in this your old age;

May your last days on earth be the best;

And when the last summons shall call you away,

May you quietly sink to your rest! |

|

_______________________________

THE REFORMER'S MONUMENT.

SUPPOSED TO BE DISCOVERED ON RE-VISITING THE EARTH. |

|

WHAT! here a Monument, and this a graveyard!

A curious casket for so rich a gem!

There's nothing here but crumbling dust and ashes,

And sculptured urns can be no use to them.

Their eyes are closed, who sleep in these dark chambers;

These drooping flowers must rear their heads in vain;

Their ears are deaf to all the fulsome flat'ry,—

Which—could they hear it,—would but give them pain.

The bells are chiming out the hour of midnight;

A solemn, painful stillness reigns around;

I am the only one on this "God's Acre;"—

Alone I hover o'er this hallowed ground.

But what is here,—in this secluded corner?

Where careless footsteps have but seldom trod?

A faded wreath or two lie here untended;

A willow, too, bends o'er the grassy sod.

Now, o'er my head, the queenly moon is shining;

And, by her silvery light, I plainly see

A sculptured stone; and, by its brief description,

Find that this stone is raised to flatter me.

Is this the boon for which I spent a lifetime?

The goal I laboured for, and sought so long!—

The sole reward of all my best endeavours!—

Alas! mistaken kindness, cruel wrong!

I fain had hoped for something far more human,

Than this cold, lifeless monument of stone!—

Something more cheerful than these sad surroundings;

And more akin to living flesh and bone;—

The merry ring that comes from human voices;—

The sweet remembrance of a child's last kiss;—

A grateful heart for some kind word I've uttered,—

Would be more welcome than a scene like this.

I waited long for what you never gave me,—

A kindly word to help me on my way,

And give me courage in my poor endeavour,

To bring about a brighter, better day.

This sculptured stone—raised here to do me honour,—

Telling to passers-by my name and worth,—

Can ne'er wipe out, or blot from my remembrance,—

The pangs of torture I endured on earth!

Oh, Queenly Moon, withdraw thy silvery brightness!

Clouds! roll along; shut out this painful sight!

And may this mocking scene be lost for ever,—

Lost in the darkness of this winter's night.

How quiet round me lie these thousand sleepers!

Forms that once trod this earth in health and life;

Some of them left the battle field uninjured;

Some, like myself, were worsted in the strife.

The very dust on which I tread is sacred;

These forms, though dead, are still to memory dear.

These clods shut out from view our great reformers;—

The men who fought our battles slumber here!

Here lie the shells that held the precious jewels—

That simple Ignorance thought of little worth:—

Pushed from the stage to make more room for actors

Of meaner talents, though of "nobler birth."

But why stay here; the morn is slowly breaking;

Far in the east I see a gleam of light:

The King of Day will soon ascend the chariot

Now driven by the stately Queen of Night!

Farewell, damp graveyard! farewell, kindly Mother;

On thy dear breast thy children safely lie;

The world can ne'er disturb their peaceful slumbers,

Thy breast their bed, their coverlet the sky! |

|

_______________________________

TO MY FRIEND COUNCILLOR W. H. BUCKLEY, J.P.

ON RECEIVING FROM HIM A NUMBER OF OLD MANCHESTER

"OBSERVERS,"

CONTAINING—AMONGST OTHER MATTER—AN ACCOUNT OF THE TRIAL OF

HENRY HUNT, AND OTHERS. |

|

I AM pleased with the present you sent me,

And though all the papers are old,

I can honestly, truthfully tell you,

That I value them more than gold.

These time-worn "Observers" remind us

Of the struggles and desperate fights

The Reformers were called to encounter,

While demanding their lawful Rights!

Ah! little we know of the hardships

Our forefathers had to endure,

When fighting the heartless oppressors,

And pleading the cause of the poor!

They were hunted from village to hamlet,

As foes to the King and Crown

As firebrands bent on destruction,

And turning things upside down.

But—thanks to the Lancashire heroes,

Bad laws have been swept away;

We can speak our thoughts out freely,

And men are men to-day!

All honour to brave Sam Bamford,

Who, while in the prime of life,—

Surrounded with dear home comforts,

The smiles of his child and wife—

Led on his suffering neighbours,

With some cheering word or song,

To demand their Rights as a People,

And denounce all crime and wrong.

He has finished his work here, and left us,—

Gone to live in his home on high!

Has anyone caught his mantle,

And worn it? If not, then why?

Have we got all reforms that are needed?

Is the talked-of Millennium in sight?

Have all bad laws been abolished?

Have we got to the end of the fight?

Again let me heartily thank you,

And assure you of this one fact,—

That it gives me the greatest of pleasure,

To publish your generous act. |

|

_______________________________

JUBILEE SONG. |

|

GOD preserve and bless our Empress!

May His choicest, richest blessing

Fall in showers on Queen Victoria,

On her jubilee!

England's Queen, and India's Empress,

Widow of the Good Prince Albert,—

Hail! all hail to thee!

Join the chorus, swarthy Indians!

Waft the strains along, Columbia!

All can sing Victoria's praises

On her jubilee.

Prattling babes, and hoary vet'rans,

Stalwart youths, and lovely maidens,

Laud the name of Queen Victoria,

Laud it o'er the sea! |

|

_______________________________

TO MY SON ARTHUR,

ON HIS TWENTY-FIRST BIRTHDAY. |

|

TO-DAY you attain unto manhood, dear son;

Having served the three sevens, you are now twenty-one.

Like others before you, your journey through life,

Has had its full share of annoyance and strife.

But the seed has to struggle awhile in the soil,

Ere the labourer secures the results of his toil;

We have sickness and losses, the storms and the showers,

Mixed with health and successes, with sunshine and flowers.

You will find, son, as others before you have found,

That both good and evil come out of the ground.

We are ever surrounded by virtue and vice,

And can't be too careful in making our choice.

"This world is a stage"—so Will Shakespeare declares;

And you amongst others are one of the players.

It may be till now you've been much out of sight,—

Kept at work on the scenes, or arranging the light.

But to-day, my dear son, you've arrived at full age,

And you'll have to appear at the front of the stage;

Where your acts will be open to praise or to blame,

And the audience mete out to you honour or shame.

What an anxious position is this to be in,—

The applause of the public to lose or to win!

May you have many happy returns of the day,

And the people's "well-done" at the end of the play! |

|

_______________________________

DEAR OLD ENGLAND, GOOD-BYE.

Tune—"The Mistletoe Bough." |

|

DEAR home of my childhood, I bid thee good-bye,

With a load at my heart, and a tear in mine eye;

Thou home of my forefathers, land of the free,

I sigh at the thought of departing from thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

Good-bye to thy mountains, thy moorland, and trees,

And the health-giving fragrance that floats on the breeze;

Other mountains and moors I expect soon to see,

But they cannot blot out my remembrance of thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

Good-bye to thy graveyards; I'm loath to depart

From the long-cherished objects that cling to my heart;

The graves of my fathers are sacred to me,

And now, my dear country, I leave them with thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

I go where more labour is found for the poor,

And the bread of industry is often more sure;

But in my new home, far away o'er the sea,

My thoughts will oft wander, dear England, to thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

I have basked in the sunbeams that play on thy rills;

I have trod thy fair valleys and roamed o'er thy hills;

And whate'er be my lot, wheresoever I be,

These fond recollections will cling unto me.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

There's a grandeur about thy old bulwarks and towers,

And loveliness seen in thy gardens and bowers;

Thy maidens are beautiful, lovely to see—

No wonder I sorrow at parting from thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

In the land I am bound to, whatever betide

Should fortune smile on me, or wealth be denied,

In sunshine or shadow, in sorrow or glee,

My true English heart will beat fondly towards thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

I am soon to be wafted away o'er the main,

And these eyes may not feast on thy beauties again;

But whatever the distance between us may be,

I shall never forego my attachment for thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

When surrounded by strangers in some far-off glen,

I will talk of thy greatness again and again;

How unworthy the land of my birth I must be,

If I fail to make known my affection for thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye.

When toss'd on the lea by the wave and the wind,

I will think of the dear ones I'm leaving behind;

And in my new home I will fall on my knee,

And offer a prayer, dear Old England, for thee.

Dear Old England, good-bye. |

|

_______________________________

"BETHESDA,"

READ AT THE MEETING HELD TO CELEBRATE THE RE-OPENING

OF BETHESDA CHAPEL, BLACKPOOL, FEBRUARY 16TH, 1876. |

|

MR. Chairman and friends, it affords me delight

To respond to your kind invitation to-night,

And I venture to hope you will kindly excuse

A few rambling remarks of my wayward muse.

'Tis a pleasure to many now present, I know,

To meet where our fathers met long ago,

And tread in the very same steps they trod,

When they met in this building to worship their God.

There may be some here who remember the day

When God's people first met here to praise and pray;

And I'm sure it must please all good women and men

To meet with their Lord at "Bethesda" again.

And to some this old spot is especially dear,

For those they once loved are now slumbering here:

The father, who buried his pride and his joy,

Comes to drop a warm tear o'er the grave of his boy.

Others mourn over flowers faded early in life—

The wife mourns her husband, the husband his wife;

Many groans have been heard, many hearts have bled,

And open graves moistened by tears that were shed.

But we meet not to-night to lament or be sad—

Oh no! we are here to rejoice and be glad

That the "Pool of Bethesda" is open once more,

Where the sick their Physician may meet as of yore.

Where the sin-sick, the helpless, and impotent folk,

May again hear the Saviour say, "Rise up and walk"—

That this great healing power may be felt in our day,

Let us earnestly labour and fervently pray.

It was here the Dissenters their banner first raised,*

On this small hill of Zion. And oh! God be praised,

It has never been lowered, 'tis there to this day,

As a guide to the pilgrim through life's rough way.

To arms! Christian soldiers! The day draweth nigh

When the cries of God's people shall reach to the sky;

When the curse of intemperance no longer shall mar

The fair face of this earth. Truth's victorious car

Shall ride forth triumphant, and speed on its way,

And darkness shall flee at the dawning of day.

Then up, Christian soldier, and gird on thy sword,

And tread in the steps of thy Master and Lord.

Go up to the greatest, and down to the least,

And invite them to come to the gospel feast;

Ask the envious to cease from his envy and strife,

And the drunkard to take of the "water of life."

Be kind to the erring—we all of us know

There is far greater power in a kiss than a blow;

And a word spoken kindly, as everyone knows,

Is far more effectual than blame or blows.

But I must not detain you with words such as these,

So excuse the remarks I have made, if you please;

There are those now before me more able to teach,

With attainments that I shall ne'er offer to reach;

Who must always outstrip me, howe'er I may plod—

Whose heads have grown grey in the service of God.

With these I must leave you, but cannot do less

Than wish all our friends at "Bethesda" success.

Success to the preacher—may God's help be given;

Success to the choir—may their songs rise to heaven;

May the hearers—of whom I myself form a part—

Take the lessons and teachings of scripture to heart;

And when we have ta'en our last look at the sun,

When the world disappears and the battle is won,

May we meet those we love in the realms of the blest

Where the flowers never fade, and the weary find rest!

* Bethesda Chapel was the first Dissenting place of worship

erected in Blackpool. |

|

_______________________________

CHRISTMAS SONG. |

|

HOW Christmas-tide stirs our emotions,

And we hail the return of the morn,

When angels proclaimed the glad tidings,

That Jesus the Saviour was born!

What a theme we have for the poet!

What a subject is this for the pen!

But who can describe the sensations

Of those who were witnesses then!

CHORUS:

Still, we on this festive

occasion,

Our tribute of

praises will bring;—

Loud anthems to God in the highest,

And to Jesus the

new-born King!

The world had long groped in the darkness;

God's people were sorely oppressed;

His temples defiled by the stranger,—

The noblest, the purest and best

Were objects of hatred and malice,—

When the heralds of God came forth,

With tidings of joy to all nations—

"Good-will to men! Peace upon earth!"

CHORUS:—And

we, &c.

And now, in the hall and the cottage,

When this season of joy comes round

When hoar-frost is seen on our windows,

And snow-flakes lie thick on the ground,

We meet in the family circle,

And again sing the dear old song

We learnt at the knees of our mothers,

So long ago; ah! so long!

CHORUS:—And

now, &c.

Then reach the old fiddle down, Robin;

And, lads, get your voices in tune;

Wife, put by that knitting, and help us,

And Peter shall play the bassoon;

And though our best efforts be feeble,

And faults may be found in our strains,

Our songs shall at least be as hearty,

As those heard on Bethlehem's plains!

CHORUS.—Yes,

we, &c. |

|

_______________________________

VERSES READ AT A JUBILEE TEA MEETING.

Held in the Congregational School, Stalybridge, on Saturday Evening, April

23rd, 1887, on which occasion Messrs. John Laycock and Joseph Hurst, the

Superintendents, were each Presented with a Purse of Gold and an Address

in book form. |

|

MR. Chairman and friends, it affords me delight

To be here and take part in this meeting to-night;

Tho' a platform, 'mongst parsons is hardly my sphere,

But your minister kindly invited me here;

And tho' you may some of you think me to blame

For accepting his kind invitation, I came;

If the general discovers he's picked the wrong men,

No doubt he will mind not to do it again.

This is jubilee Year, and, to judge from this scene,

All the honours are not to be showered on the Queen—

For while city and hamlet and town are astir,

As to how they shall celebrate jubilee Year

In a manner becoming, 'tis pleasing to find

That our Stalybridge friends are not lagging behind;

And for those they would honour they have not to roam

To London or Scotland, but find them at home.

You have learned to distinguish the wolves from the lambs,

And honour real heroes and not the mere shams—

The man who by labour increases our joy,

Not the warrior whose business it is to destroy.

I remember distinctly the year 'thirty-seven,

Altho' but a boy—not much more than eleven;

Fifty years have rolled o'er, but at this distant day

I can still see the school—the old school o'er the way.

Three lads sought admission—two brothers and self;—

The stones of this building were then in the delph;

I had not commenced spinning thoughts into rhyme;

Our old friend Mrs. Warhurst was then in her prime.

Fifty years since her wedding attire would be worn,

And two out of three of her children unborn!

We had then a dear brother—your guest here and I—

But for forty-nine years he has slept hard by.

Very few of the friends—I am sorry to say

Who were here fifty years since, are with us to-day.

In fancy I see a whole host of them now:

The old pastor with silvery locks on his brow;

The fine, manly bridegroom, and lovely young wife,

Setting out with great hopes in the morning of life;

But the lurking disease with its withering blight,

Removed these dear loved ones away from our sight.

You will pardon these mournful reflections, I hope,

I have purposely given my feelings full scope,

Because it is well to reflect now and then,

And put these reflections in shape with the pen.

It is well to be merry, but if we are wise,

We must look for the storms that are sure to arise.

Let me speak to the young who are met in this place—

This life is a battle, a voyage, a race!

The honours of earth are not easily won;

You must toil in the shade a deal more than the sun.

And you'll find this, my friends, while advancing in years,

The smiles will be few when compared with the tears.

The guests we have met here to honour to-night,

Whose locks, as you see, are both scanty and white—

Had entered the conflict, their armour had worn,

Before you young men and young women were born!

Fifty years in the fight, and not once known to yield!

Fifty years of hard service, and still in the field!

Have you thought of these hardships, denials, and strife,

Ye who think easy births the great objects of life?

Their talents were used, the trees have borne fruit,

And the seeds they have sown here have taken deep root;

And many brought up 'neath their nurturing care,

Are now women and men who are taking their share—

In the work of improving this country of ours,

And replacing the thistles with fruitage and flowers.

Please remember the lines I have published before—

I will venture to bring them before you once more:—

"Life's battles aren't fought upon couches of down;

You've a cross you must bear before reaching the crown;

The farmer for months has to labour and toil,

Before he can gather the fruits of the soil."

This is jubilee Year, and these faces we see

Proclaim the great fact that their owners are free—

Yes, free from the many temptations that stand

The traps set to ruin the youth of our land.

Our two worthy guests would ne'er dream of the day,

When their work would be noticed in this pleasing way;

And I'm sure it must give them more pleasure than pain,

To find that they have not been labouring in vain;

That many from childhood were tenderly nurst

By my brother, John Laycock, and friend Joseph Hurst.

Ah! worthy old neighbours, 'tis little we know,

What a deep debt of gratitude some of us owe

To the dear sainted parents now passed to the skies;

No wonder the tear drops should start to our eyes,

As our minds wander back to the days of our youth,

When our minds were well stored with the lessons of truth.

There is just this one thought mars the meeting to-night,—

That our parents aren't present to look on this sight:

If the sons any praiseworthy actions have wrought,

These are due to the lessons the parents have taught.

Let me thank my old neighbours for being so kind

As to give me this chance to unburden my mind;

For no doubt you have heard, and may think it seems strange,

That in some of my views I have ventured to change.

But to me it seems madness o'er dogmas to fight,

So long as the head and the heart are all right;

I care not what censure you pass on my creeds,

So long as you cannot find fault with my deeds.

Let me say that the lessons I got at this place

Will influence my life to the end of my days.

As one suffering bad health—as a poor weaver's son—

I am not ashamed of the work I have done.

If what I've accomplished has brought any fame,

I am willing my friends here should join at the same;

For allow me to say you have given me delight,

By the honour conferred on my brother to-night.

I am certain your gifts have been wisely disbursed,

Both on brother John Laycock, and friend Joseph Hurst;

May their lives be long spared to enjoy what you've given,

Then receive a still grander reception in heaven. |

|

_______________________________

A STALYBRIDGE SUPPER HOAX. |

|

GOOD people, attend; have you heard of the "hoax"

Which has lately been played upon some of our folks?

If you have not, pray read on awhile, if you please,

And I'll give you a few of the facts;—they are these:—

Some "wags" in the town, who seem fond of a joke

At the expense of others, (od rot on such folk!)

Got some circulars printed and had them sent out

To our middle-class tradesmen, and "nobs" round about,—

Inviting them all to a supper, one night;

And of course many went, thinking all would be right,

Well prepared, I've no doubt, for a "jolly good spree;"

For some had been training all day, do you see,

In anticipation of what they might get;

You could see by their looks they had stomachs "to let."

One man, whose employment is oft very high,

Between the green earth and the lovely blue sky,

Thinking this a nice offer, he left all his slates,

Determined for once he would clean them some plates.

So he dressed himself up in his white blouse and hat,

(He fills all his clothes very well, he's so fat,)

Went down in good time,—for this reason, no doubt,—

To loose a few buttons, and spread himself out;

For his mind was made up long before he went in,

To take all the wrinkles clean out of his skin.

But, alas for the castles he built in the air,

Not a morsel of supper awaited him there.

Another man, very well known in the town,

As one very clever at knocking things down,

Was kindly invited along with the rest,

And a feeling of thankfulness rose in his breast.

Oh, he seemed quite delighted! it's likely he would:

I would draw you his portrait out now, if I could,

As he went to the "Angel," as clean as a pin,

(Though he never looks clean—he's a very dark skin.)

And, seeing the landlord, he nodded his head,

Threw the circular down on the table, and said—

"Aw'm goin' to a feed at th' Commercial to-neet;

Th' lon'lord's givin' a supper,—an' nowt nobbut reet.

They sen there'll be sammon, plum puddin', an' lamb.

He's a jolly owd trump, mon—good-hearted—is Sam!"

And away he went out, with a hearty good will,

Expecting, of course, very shortly to fill

His corpulent pouch, which had got rather flat,

With fasting so long,—but no matter for that,

For, along with the rest of the "nobs" of the town,

He very soon found he was "done" rather "brown."

A dealer in "fourpenny," living hard by,

(Now, I've nothing against this cheap beverage,—not I,)

Feeling troubled with wind,—having fasted since noon,

Some seven or eight hours,—went in rather soon;

Of course, he'd no notion of how he was caught,

So he called for some ale, which the waiter soon brought,

To whom he just whispered, while handing his "brass,"

"Aw reckon this supper's noan quite ready, lass?"

"Not quite," she replied, "you are rather too soon;

You see we are plagued with a very slow oon."

"O reet, lass, o reet," said our friend, with a smile;

Then he drank off his ale, and went home for awhile.

But he did not stay long there—he could not abide;

For the wrinkles began to appear in his hide;

And his boiler sung out in the key of "B flat;"

Why, the fellow would almost have worried a rat.

He returned in this starving and famishing state,

To be told (oh, how dreadful!) he'd gone back too late;

For some hungry scarecrow,—confound the old thief,

Had been in the house, and walked off with the beef.

Now one of the guests had been absent from home,

And his wife—not aware of the hour he would come,

Had not got any supper spread out on the board,

But she handed the circular o'er to her lord,

Which she said had been left for him during the day,

By a party residing just over the way.

He took it, and glanced it well o'er at the light,

Then said—with a smile on his features—"All right.

Aw'm invited to go to a supper, ha! ha!

That's just what aw'm wantin',—aw'm off, lass,—ta ta."

And soon the Commercial he entered with glee,

For the thought of plum pudding, with brandy dip, free,

Had created most pleasing sensations, you know,

And made his saliva profusely to flow.

But, my eye! he stood there as if shot from a gun,

When the company told him the stuff was all done.

Not a bit of a crust nor a bone could be seen;

A sickening look out when the appetite's keen.

He went home to his wife, and made known his sad fate,

When she said, "What a pity tha went deawn to' late!

But it's noan th' furst misfortin' tha's had sin we'rn wed,

So ne'er mind, get thi porritch, an' let's go to bed."

And now for a lesson such hoaxes may teach;—

But don't be alarmed, I'm not going to preach.

Let nothing, my readers, induce you to roam,

In search of good suppers, but get them at home.

Should a neighbour invite you some night to a "stir,"

You can say "Please excuse, I'm obliged to you, sir."

Should it turn out a hoax, you can relish the fun,

And subscribe yourself thus:—

ONE WHO HAS NOT BEEN "DONE." |

|

_______________________________

TO MY BROTHER BARD, THOMAS BARLOW.

(BORN ON THE SAME DAY AS MYSELF.) |

|

DEAR and worthy Mr. Barlow,

When I first began this letter,

I intended you should have it,

Through the medium of your pastor,

Who has lately been at Blackpool,

But I could not get it finished.

In the first place, let me tell you

That I felt extremely sorry,

When I heard from Mr. Lambley,

That your health had failed you lately.

Let us hope that splendid weather,

Grateful showers, and glorious sunshine,

And the warbling of the songsters,

May revive your drooping spirits,

To their wonted health and vigour.

As for me,—I'm much as usual;—

Sometimes worse, and sometimes better;—

One day full of joyous feelings,

And, perhaps, the very next day

Finds me fretful, sad and gloomy.

Such is life: we find our pathway

Strewn with thorns, as well as roses.

In the soil the seed must struggle,

Ere the flower gives forth its fragrance;

And, to get a perfect picture,

We must have both lights and shadows.

But away with serious musings;—

You are down, and need uplifting.

Would to God that I could help you,—

Write you out some safe prescription,—

Something that would raise your spirits,—

Help to put new life within you!

But you know, friend, I'm no doctor;

But, like you, an ailing patient,—

Taking "Mother Seigel's Syrup,"

Boring others with my ailments;

Preaching what I seldom practice,—

Namely, patience in our sufferings.

Well, we're all poor, weakly sinners,

Giving way to heavy dinners;

Grovelling, groping in the darkness,

When we ought to face the sunlight.

Come to Blackpool, dear friend Barlow,

Come, if possible, this week-end.

And inhale the healthy breezes,

Sweeping o'er the great Atlantic!

Overwork is always harmful;

Man must have some recreation.

You and I are getting older,

Work we once performed with pleasure,

Now we often find a burden,

And we long for rest and quiet.

Well, dear friend, we must not murmur;

We have had our youthful pleasures,

Now we stand aside for others;—

They're the actors, we're spectators!

Few can say what you and I can,

That we started life together;

You 'midst Derbyshire's attractions,

I amongst the hills of Yorkshire.

Both of us have had our trials;

Have we met those trials bravely?

Well, the fight is nearly over;

Now and then a shot may strike us,

But we let them pass unheeded.

Still a few more paces onward;

Slowly pass a few more milestones;

Then life's journey will be ended!

Here I close this long epistle—

Longer than than at first intended.

Thoughts came fast as I proceeded,—

Thoughts I could not pass unheeded,

So I put them down in writing,

Very plain and very simple.

Well, good-bye, friend, for the present;

May God's blessing rest upon you,—

Is the earnest supplication

Of the writer,—Samuel Laycock. |

|

_______________________________

HUGH MASON. |

|

ANOTHER great man fallen;

A leader in the ranks;

For whose kind benefactions,

A Nation owes her thanks.

We mourn when the Spoiler snatches

A brother from our side;

And this world of ours is poorer,

Since good Hugh Mason died!

We read in history's pages,

Of actions nobly wrought;—

Of difficulties conquer'd,

And battles bravely fought.

We read of deeds of daring;—

Of fearless men and bold,

Who fought for God and Country,

In the warlike days of old.

All these we love and honour;

And now we have one more name

To add to the band of heroes,

Who grace the scroll of fame.

The people's friend, Hugh Mason,—

So lately from us torn,—

Will live in the hearts and affections

Of thousands yet unborn!

He fought, but with moral weapons

The press, the voice, and pen;

And some of us well remember—

Brave men were needed then!

As a large employer of labour,

He was generous, just, and kind;

And, while seeking the good of the body,—

He tried to improve the mind.

His generous, kindly actions

Will live in our memories long;

And the honoured name of Mason

Shall be handed down in song! |

|

_______________________________

THE EXCURSIONISTS' SONG. |

|

ALL hail to the season when Nature is dressed,

In her fine summer clothing, her gayest and best;

When the trees of the forest are laden with bloom,

And a thousand wild flowers breathe a fragrant perfume.

Farewell, for a while, to the dull smoky town,

Where the seeds of diseases so often are sown;

Where the lingering consumption turns sickly and pale,

The cheeks of the girl once so blooming and hale!

We will leave these sad scenes, and away we will go,

Where the health-giving breezes unsparingly blow;

Where our ears may be charmed with the ocean's wild roar,

As we playfully gather the shells on the shore.

The clash of machinery is hushed for awhile,

And the care-burdened look is exchanged for a smile;

We leave the dull workshop, and haste to the bowers,

Where our hearts shall be gladden'd with music and flowers.

These foreheads of ours we will bare to the breeze,

Which gathers its fragrance from moorland and trees;

And for once in our lives we'll enjoy the rich treat,

Provided alike for the poor and the great.

We will gaze on the clouds tinged with purple and gold;

Feast our minds for a time upon beauties untold;

Thus refreshed with the journey, our voices we'll raise,

And join with the birds in a chorus of praise!

Then at night, as the sun gently sinks in the west,

We'll return to our homes, and the friends we love best;

Feeling thankful to Him whose all bountiful care,

Provides such enjoyment for mortals to share. |

|

WHEN asked to assist you this evening

With my poor, limping muse,

Though unwell, and unfitted for labour,

I couldn't very well refuse.

Still, we all of us know what is needed—

From what we can hear and see,

Without any special exertions,

Or any appeal from me.

We do well to provide entertainments,

And places of public resort,

Where the care-worn may fling off trouble,

And join in pure, innocent sport.

We are proud of our beautiful buildings,

Such as this one in which we are met;

But there's something we haven't that is wanted—

We haven't a hospital yet!

We some of us claim to be Christians,

But religion is put on the shelf,

If it fails to promote our interests,

Or bring to us power and pelf.

Now, these raps at the people of Blackpool,

May appear to be very unkind,

But I'm sure you will please to excuse me,

If I venture to speak my mind.

That we've souls that require our attention,

Is a fact we admit as true;

But we must not forget—nay, we cannot,

That we've got our bodies, too;

And while men are exposed to danger,

Bruised limbs must be bound and set;

But we haven't provided for these things—

We haven't a Hospital yet.

I have long been a careful observer—

An observer of men and things,

So am not without that knowledge

That a long experience brings;

And I hardly need tell my hearers,

It has pained my heart to think

How vice has been nursed and supported,

And virtue left to sink!

Yes, and this in a land of Bibles,

Where Queen Victoria rules;

Where we've colleges, churches, and chapels,

And both day and Sunday schools!

How shall we account for this conduct—

These strange, un-Christ-like deeds!

We are certainly wrong in our practice,

Whatever may be our creeds.

We invest our money too often,

In what tends to our National shame—

And we've naught but good wishes and pity

To bestow on the sick and lame.

I am pleased with our grand motto—"Progress,"

For it indicates breadth of mind,

And shows that the people of Blackpool

Don't intend to be left behind.

We hail the new Tower they are building,

And we hail the fine Pier down South;

These show we abhor stagnation,