|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER VI.

HIS APPEAL TO THE PEOPLE

"There are some very earnest and benevolent persons who

have nevertheless a hollow jingle in their goodness. They mistake

their own indifference for impartiality, and call upon men to renounce for

philanthropic purposes convictions which are as sincere, as salutary, and

often more important to public freedom than philanthropy itself."

G. J. H.

IT was the year 1825 which saw co-operative

views—which since 1812 had been addressed by Mr. Owen to the upper

classes—first taken up by the working class. In 1817, as the reader

has already seen, he declared "all the religions of the world to be

founded in error"; he alarmed the bishops and clergy, many of whom were in

sympathy with his views, and had themselves intermittent compassion for

the working class. For twenty-three years their wrath endured.

In 1840 Mr. William Pare, one of the earliest and ablest of Mr. Owen's

disciples, was compelled to resign the office he held of Registrar of

births, deaths, and marriages in Birmingham, in consequence of its being

made known to the Bishop of Exeter that Mr. Pare sympathised with Mr.

Owen's views.

Many of Mr. Owen's difficulties with theologians arose

through their not understanding him, and through Mr. Owen not

understanding that they did not understand him. His followers were

fond of quoting the lines:—

|

"For modes of faith let graceless zealots fight,

His can't be wrong whose life is in the right."

|

It is not at all clear that a man has a fair chance of

getting his life right while his creed is wrong. With all men creed

has a great deal to do with conduct. Pope's lines are the doctrine

of a latitudinarian without a conscience. But the argument of Pope

imposed on Mr. Owen, as it has done on other excellent men. Mr. Owen

was not himself indifferent to conviction. His own conviction about

the religion of humanity was so strong that he paid no heed to any

opinions which contradicted it. An innovator may point out the

errors and mischiefs of a popular faith; but he can never command respect

from adversaries unless he makes himself master of their case and does

justice to the equal honesty of those sincerely opposed to him.

Meaning nothing offensive by it, Owen often displayed the common insolence

of philosophers—the insolence of pity. It is irritating and

uninstructive to earnest men to be looked down upon with compassion on

account of convictions acquired with anxiety and many sacrifices.

"It is not our object," at other times Owen used to say, "to

attack that which is false, but to make clear that which is true.

Explaining that which is true convinces the judgment when the mind

possesses full and deliberate powers of judging." The creed of

Co-operation was that the people should mean well, work well, secure to

themselves the results of their labour, and neither beg, nor borrow, nor

steal, nor annoy. Owen inconsistently denied men's responsibility

for their belief, and then said the new system did not contravene

religion. As religion was then understood it did.

In 1837 Mr. Owen, in his discussion with the Rev. J. H.

Roebuck, at Manchester, said "he was compelled to believe that all the

religions of the world were so many geographical insanities." It was

foolishness in followers to represent, as did John Finch and Minter

Morgan, that their views were those of "true Christianity." Their

business was simply to contend that their views were morally true, and

relevant to the needs or the day, and rest there. Neither to attack

Christianity nor weakly attempt to reconcile social views to it would have

been a self-defensive and self-respecting policy.

Mr. Owen's theory of the motives or conduct was one which

could only commend itself to persons of considerable independence of

thought—who were then a small minority. To incite men to action he

relied on four considerations, namely, that what he proposed was:—

1. True; 2. Right; 3. Humane; 4. Useful.

It was understood very early [37]

that Co-operation was proposed as a system of universal industry, equality

of privileges, and the equal distribution of the new wealth created.

This was an alarming programme to most persons, except the poor.

Many did not like the prospects of "universal industry." The

"distribution of wealth" in any sense did not at all meet the views of

others, and "equality of privilege" was less valued.

Mr. Owen determined upon committing his schemes to the hands

of the people, for whom he always cared, and sought to serve. Yet,

politically, he was not well fitted to succeed with them. Cobden

said Lord Palmerston had no prejudices—not even in favour of the truth.

Mr. Owen had no political principles—not even in favour of liberty.

His doctrine was that of the poet:—

|

"For modes of government let fools contest,

That which is best administered is best"

|

—a doctrine which has no other ideal than that of a benevolent despotism,

and has no regard for the individual life and self-government of the

people. Mr. Owen was no conscious agent of the adversaries of

political rights. He simply did not think rights of any great

consequence one way or the other. There never was any question among

Liberal politicians as to the personal sincerity of Mr. Owen. Jeremy

Bentham, James Mill, Francis Place were his personal friends, who were

both social and political reformers, and valued Mr. Owen greatly in his

own department, which was social alone. [38]

The French social reformers, from Fourier to Comte, have held

the same treacherous tone with regard to political freedom. Albert

Brisbane, who published the "Social Destiny of Man," himself a determined

Fourierite, announced on his title-page, "Our evils are social not

political"—giving a clean bill of health to all the knaves who by

political machination diverted or appropriated the resources of the

people. "Our most enlightened men," he contemptuously wrote, "are

seeking in paltry political measures and administrative reforms for means

of doing away with social misery." Tamisier more wisely wrote when

he said, "Political order has alone been the object of study, while the

industrial order has been neglected." Because social life had been

neglected for politics, it did not follow that political life was to be

neglected for social. This was merely reaction, not sense.

Another dangerous distich then popular with social reformers

was the well-known lines Tory Dr. Johnson put into a poem of Goldsmith:—

"How small of all that human hearts endure

That part which laws or kings can cause or cure." |

Goldsmith knew nothing of political science. The cultivated,

generous-hearted, sentimental piper was great in his way. He foresaw

not England made lean and hungry by corn laws; or Ireland depopulated by

iniquitous laws; or France enervated and cast into the dust by despotism;

but social reformers of Mr. Owen's day had means of knowing better.

It was not their ignorance so much as their ardour that misled them.

The inspiration of a new and neglected subject was upon them, and they

thought it destined to absorb and supersede every other. The error

cost them the confidence of the best men of thought and action around them

for many years.

Mr. Owen's own account of the way in which he sought to

enlist the sympathies of the Tories of his time with his schemes is

instructive. They were, as despotic rulers always are, ready to

occupy the people with social ideas, in the hope that they will leave

political affairs to them. How little the Conservatives were likely

to give effect to views of sound education for the people, irrespective of

religious or political opinion, we of to-day know very well.

"I have," says Mr. Owen, "attempted two decisive measures for

the general improvement of the population. The one was a good and

liberal education for all the poor, without exception on account of their

religious or political principles; to be conducted under a board of

sixteen commissioners to be chosen by Parliament, eight to be of the

Church of England and the remainder from the other sects, in proportion to

their numbers, the education to be useful and liberal. This measure

was supported, and greatly desired, by the members of Lord Liverpool's

administration; and considerable progress was made in the preliminary

measures previous to its being brought into Parliament. It was very

generally supported by leading members of the aristocracy. It was

opposed, however, and, after some deliberation, stopped in its progress by

Dr. Randolph, Bishop of London, and by Mr. Whitbread. But the

Archbishop of Canterbury, and several other dignitaries of the Church,

were favourable to it. The declared opposition, however, of the

Bishop of London and of Mr. Whitbread, who it was expected would prevail

upon his party to oppose the measure, induced Lord Liverpool and his

friends—who, I believe, sincerely wished to give the people a useful and

liberal education—to defer the subject to a more favourable opportunity.

The next measure was to promote the amelioration of the

condition of the productive classes by the adoption of superior

arrangements to instruct and employ them. I had several interviews

with Lord Liverpool, Mr. Canning, and other members of the Government, to

explain to them the outlines of the practical measures which I proposed.

They referred the examination of the more detailed measures to Lord

Sidmouth, the Secretary of State for the Home Department, and I had many

interviews and communications with him upon these subjects.

"I became satisfied that if they had possessed sufficient

power over public opinion they would have adopted measures to prevent the

population from experiencing poverty and misery; but they were opposed by

the then powerful party of the political economists.

"The principles which I have long advocated were submitted

for their consideration, and at their request they were at first printed

but not published. They were sent, by the permission of the

Government, to all the Governments of Europe and America; and upon

examination by statesmen and learned men of the Continent were found to

contain no evil, but simple facts and legitimate deductions. In one

of my last interviews with Lord Sidmouth, he said: 'Mr. Owen, I am

authorised by the Government to state to you that we admit the principles

you advocate to be true, and that if they were fairly applied to practice

they would be most beneficial; but we find the public do not yet

understand them, and they are therefore not prepared to act upon them.

When public opinion shall be sufficiently enlightened to comprehend and to

act upon them we shall be ready and willing to acknowledge their truth and

to act in conformity with them. We know we are acting upon erroneous

principles; but we are compelled to do so from the force of public

opinion, which is so strongly in favour of old-established political

institutions.' To a statement so candid I could only reply, 'Then it

becomes my duty to endeavour to enlighten the people and to create a new

public opinion.'" [39]

If Lord Sidmouth believed what he said, in the sense in which Mr. Owen

understood him, he dexterously concealed, in all his public acts and

speeches, his convictions from the world.

It was happily no easy thing even for Mr. Owen to win the

confidence of the working-class politicians. They honourably refused

to barter freedom for comfort, much as they needed an increase of physical

benefits. We had lately a curiously-devised Social and Conservative

Confederation, the work of Mr. Scott-Russell, in which the great leaders

of the party always opposed to political amelioration were to lead the

working class to the attainment of great social advantages, and put them

"out in the open," as Sir John Packington said, in some wonderful way.

Several well-known working-class leaders, some of whom did not understand

what political conviction implied, and others who believed they could

accept this advance without political compromise, entered into it.

There were others, as Robert Applegarth, who felt that it was futile to

put their trust in political adversaries to carry out their social schemes

and then vote against them at elections, and so deprive their chosen

friends of the power of serving them. Twelve names of noblemen, the

chief Conservatives in office, were given as ready to act as the leaders

of the new party. Mr. Robert Applegarth caused the names to be

published, when every one of them wrote to the papers, denying any

authority for connecting them with the project.

Mr. Owen's early followers were looked upon with distrust by

the Radical party, although he numbered among his active disciples

invincible adherents of that school; but they saw in Mr. Owen's views a

means of realising social benefits in which they, though Radicals, were

also interested. Mr. Owen looked on Radicals and Conservatives alike

as instruments of realising his views. He appealed to both parties

in Parliament with the same confidence to place their names upon his

committee. He went one day with Mrs. Fry to see the prisoners in

Newgate. The boys were mustered at Mrs. Fry's request for his

inspection. Mr. Owen published in the newspapers what he thought of

the sight he beheld. He exclaimed:

"A collection of boys and youths, with scarcely the

appearance of human beings in their countenances; the most evident sign

that the Government to which they belong had not performed any part of its

duty towards them. For instance: there was one boy, only sixteen

years of age, double ironed! Here a great crime had been committed

and a severe punishment is inflicted, which under a system of proper

training and prevention would not have taken place. My Lord Sidmouth

will forgive me, for he knows I intend no personal offence. His

dispositions are known to he mild and amiable; [40]

but the chief civil magistrate of the country, in such case, is far more

guilty than the boy; and in strict justice, if a system of coercion and

punishment be rational and necessary, he ought rather to have been double

ironed and in the place of the juvenile prisoner."

When Mr. Owen applied personally to Lord Liverpool, then

Prime Minister, for permission to place his name with the leading names of

members of the Opposition, to investigate his communistic plans, Lord

Liverpool answered: "Mr. Owen, you have liberty to do so. You may

make use of our names in any way you choose for the objects you have in

view, short of committing us as an administration." The next day Mr.

Owen held a public meeting. "I proposed," Mr. Owen has related,

"that these important subjects should be submitted for consideration to

the leading members of the administration and of the Opposition; and for

several hours it was the evident wish of three-fourths of the meeting that

this question should be carried in the affirmative. But as it was

supposed by the Radical reformers of that day that I was acting for and

with the ministry, they collected all their strength to oppose my

measures; and finding they were greatly in the minority, they determined

to prolong the meeting by opposing speeches, until the patience of the

friends of the measure should be worn out. Accordingly, the late

Major Cartwright, Mr. Alderman Waithman, Mr. Hunt, Mr. Hone, and others,

spoke against time, until the principal parties retired, and until my

misguided opponents could bring up their numerous supporters among the

working classes, who were expected to arrive after they had finished their

daily occupations; and at a late hour in the day the room became occupied

by many of the friends and supporters of those gentlemen, who well knew

how to obtain their object at public meetings by throwing it into

confusion." [41] The

wonderful committee Mr. Owen proposed comprised all the chief public men

of the day, who never had acted together on any question, and unless the

millennium had really arrived—of which there was no evidence before the

meeting—it was not likely that they would. This was the resolution

submitted to the meeting: "That the following noblemen and gentlemen be

appointed on the committee, with power to add to their number:—

|

The First Lord of the Treasury.

The Duke of Sussex.

The Lord Chancellor.

The Duke of Richmond.

Sir Robert Peel, the Secretary of

The Earl of Winchelsea.

State.

The Earl of Harewood.

Sir George Murray.

The Marquis of Lansdowne.

Sir Henry Hardinge.

Lords Grosvenor and Holland.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Lord Eldon.

The Attorney and Solicitor General.

Lord Sidmouth.

The Master of the Mint.

Lord Radnor.

The Secretary of War.

Lord Carnarvon, [York.

The President of the Board of

The Archbishops of Canterbury and

Trade.

The Bishops of London and Peter

The First Lord of the Admiralty.

borough.

Deans of Westminster and York.

Mr. O'Connell.

Cardinal Wild and Dr. Croly.

Mr. Charles Grant.

William Allen and Joseph Foster.

Mr. Wilmot Horton.

Mr. Rothschild and Mr. J. L. Gold-

Mr. Huskisson.

smid.

Lord Palmerston.

Lord Althorp.

Mr. J. Smith.

Brougham.

Lord Nugent.

Sir J. Graham.

The Hon. G. Stanley.

Sir Henry Parnell.

Lord Milton.

Mr. Spring Rice.

Sir R. Inglish.

Lord John Russell.

Sir Francis Burdett.

Sir John Newport.

Mr. William Smith.

Sir James Mackintosh.

Mr. Warburton.

Mr. Denman.

Mr. Hobhouse.

Mr. Alexander Baring.

Dr. Birkbeck.

Mr. Hume.

Mr. Owen."

|

There was this merit belonging to the proposal, that such an

amazing committee was never thought possible by any other human being than

Mr. Owen. Ministers were to forsake the Cabinet Councils, prelates

the Church, judges the courts; the business of army, navy, and Parliament

was to be suspended, while men who did not know each other, and who not

only had no principles in common, but did not want to have, sat down with

heretics, revolutionists, and Quakers, to confer as to the adoption of a

system by which they were all to be superseded. It was quite

needless in Major Cartwright and Alderman Waithman to oppose the mad

motion, such a committee would never have met.

Mr. Owen was never diverted, but went on with his appeal to

the people. He had the distinction of being the gentleman of his

time who had earned great wealth by his own industry, and yet spent it

without stint in the service of the public. It is amusing to see the

reverence with which the sons of equality regarded him because he was

rich. His name was printed in publications with all the distinction

of italics and capitals as the Great Philanthropist OWEN;

and there are disciples of his who long regarded the greatness of

Co-operation as a tame, timid, and lingering introduction to the system of

the great master whom they still cite as a sort of sacred name. It

was a very subdued way of speaking of him to find him described as the

"Benevolent Founder of our Social Views."

Long years after he had "retired from public life" his

activity far exceeded that of most people who were in it, as a few dates

of Mr. Owen's movements will show. On July 10, 1838, he left London

for Wisbech. On the three next nights he lectured in Lynn, the two

following nights in Peterborough. On the next night at Wisbech

again. The next night he was again in Peterborough, where, after a

late discussion, he left at midnight with Mr. James Hill, the editor of

the Star in the East, in an open carriage, which did not arrive at

Wisbeach till half-past two. He was up before five o'clock the same

morning, left before six for Lynn, to catch the coach for Norwich at

eight. After seeing deputations from Yarmouth he lectured in St.

Andrew's Hall at night and the following night, and lectured five nights

more in succession at March, Wisbech, and Boston. It was his

activity and his ready expenditure which gave ascendancy to the social

agitation, both in England and America, from 1820 to 1844.

Robert Owen died in his 88th year, on the 17th of November,

1858, at Newtown, Montgomeryshire—the place of his birth. His wish

was to die in the house and in the bedroom in which he was born. But

Mr. David Thomas, the occupant of the house, was unable so to arrange.

Mr. Owen went to the Bear's Head Hotel, quite near, and since rebuilt.

He was buried in the grave of his father in the spacious ground of the

Church of St. Mary. Mr. David Thomas and Mr. James Digby walked at

the head of the bearers. The mourners were:—

|

Mr. George Owen Davies.

Mr. Robert Dale

Mr. William Cox.

Mr. William Pare.

Mr. W. H. Ashurst.

Col. H. Clinton.

Air. Edward Truelove.

Mr. G. J. Holyoake.

Mr. Francis Pears.

Mr. Robert Cooper.

Mr. William Jones.

Mr. Law.

Mr. George Goodwin.

Mr. Pryce Jones.

|

There was quite an honouring procession—the Rev. John

Edwards, M.A., who read the burial service, medical gentlemen,

magistrates, Mr. Owen's literary executors, deputations of three local

societies, and, very appropriately, twelve infant school children—seeing

that Mr. Owen was the founder of infant schools.

After the funeral, Mr. Robert Dale Owen came into the hall of

the "Bear's Head" with a parting gift to me of the Life of his father, in

which he had inscribed his name and mine. While paying my account at

the office window, I placed the them on a table near me, but on turning to

enter the London coach with other visitors I found the books were gone.

Though I at once made known my loss, nothing more was heard of them until

forty-four years later, July 24, 1902, [42]

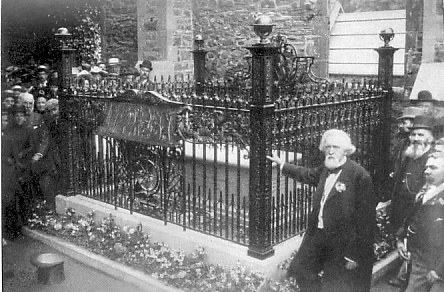

when a large delegation of co-operators from England and Scotland

assembled to witness the unveiling of the handsome screen erected by them,

to surround the tomb of Mr. Owen, on which occasion I delivered the

following address:—

We come not "to bury Cæsar"—but

to praise him. It is now recorded in historic pages that "Robert

Owen was the most conspicuous figure in the early part of the last

century." [43] We are

here at the commencement of another century to make the first

commemoration that national gratitude has accorded him.

Being the last of the "Social Missionaries" appointed in 1841

to advocate Mr. Owen's famous "New Views of Society," and being the only

survivor of his disciples who forty-four years ago, laid his honoured

bones in the grave before us, the distinction has been accorded to me of

unveiling this Memorial. As the contemporaries of a public man are

the best witnesses of his influence, or his eminence, we may recall that

Southey described him as "one of the three great moral forces" of his day.

There is a rarity in that praise, for there are still a hundred men of

force to one of "moral" force.

Do we meet here to crown the career of a man unremarkable in

the kingdom of thought, or without the genius of success? It is for

us to answer these questions. It is said by parrot-minded critics

that Owen was "a man of one idea," whereas he was a man of more

ideas than any public man England knew in his day. He shared and

befriended every new conception of moment and promise, in science, in

education, and government. His mind was hospitable to all projects

of progress; and he himself contributed more original ideas for the

conduct of public affairs than any other thinker of his generation.

It was not the opulence of his philanthropy, but the versatility of his

ideas and interests, which led members of our Royal Family to preside at

public meetings for him, brought monarchs to his table, and gave him the

friendship of statesmen, of men of science and philosophy, throughout

Europe and America. No other man ever knew so many contemporaries of

renown.

Because some of his projects were so far reaching that they

required a century to mature them, onlookers who expected them to be

perfected at once, say he "failed in whatever he proposed." While

the truth is he succeeded in more things than any other man ever

undertook. If he made more promises than he fulfilled, he fulfilled

more than any other public man ever made. Thus, he was not a man of

"one idea" but of many. Nor did his projects fail. The only

social community for which he was responsible was that of New Harmony, in

Indiana; which broke up through his too great trust in uneducated

humanity—a fault which only the generous commit. The communities of

Motherwell and Orbiston, of Manea, Fen, and Queenwood in Hampshire were

all undertaken without his authority, and despite his warning of the

inadequacy of the means for success. They failed, as he predicted

they would. Critics, skilled in coming to conclusions without

knowing the facts, impute these failures to him.

The Labour Exchange was not Mr. Owen's idea, but he adopted

it, and by doing so made it so successful that it was killed by the

cupidity of those who coveted its profits. He maintained—when nobody

believed it—that employers who did most for the welfare of their

workpeople, would be the greatest gainers. Owen did so, and made a

fortune by it. Was not that success?

A co-operative store was a mere detail of his factory

management. Now they overrun the world. Have they not

succeeded? We Co-operators can answer for that.

He bought and worked up the first bale of cotton imported

into England, thus practically founding the foreign cotton trade.

Will any one say that has not answered?

He was the first to advocate that eight hours a day in the

workshop was best for industrial efficiency. The best employers in

the land are now of that opinion. He did not fail there.

Who can tell the horrors of industry which children suffered

in factories at the beginning of the last century? Were not the

Factory Acts acts of mercy? The country owed them to Robert Owen's

inspiration. They saved the whole race of workers from physical

deterioration. Were these Acts failures? Millions of children

have passed through factories since Owen's day, who if they knew it (and

their parents, too) have reason to bless his name.

He was the first who looked with practical intent into the

kingdom of the unborn. He saw that posterity—the silent but

inevitable master of us all—if left untrained may efface the triumphs, or

dishonour, or destroy the great traditions of our race. He put

infant schools into the mind of the world. Have they been failures?

He, when it seemed impossible to any one else, proposed

national education for which now all the sects contend. Has that

proposal been a failure? In 1871, when the centenary of Owen's birth

came round, we asked Prof. Huxley to take the chair. He wrote, in

the midst of the struggle for the School Board Bill, saying: "It is my

duty to take part in the attempt which the country is now making, to carry

into effect some of Robert Owen's most ardently-cherished schemes. I

think that every one who is compelled to look closely into the problem of

popular education must be led to Owen's conclusions that the infants'

school is, so to speak, the key of the position. Robert Owen,"

Huxley says, "discerned this great fact, and had the courage and patience

to work out his theory into a practical reality. That" (Huxley

declares) "is his claim—if he had no other—to the enduring gratitude of

the people."

Huxley knew that Owen was not a sentimental, speculative, or

barren reformer. He was for submitting every plan to experiment

before advising it. He carried no dagger in his mouth, as many

reformers have done. He cared for no cause that reason could not

win. There never was a more cautious innovator, a more practical

dreamer, or a , more reasoning revolutionist.

Whatever he commended he supported with his purse. It

was this that won for him confidence and trust, given to no compeer of his

time. When 80,000 working men marched from Copenhagen Fields to

petition the Government to release the Dorchester labourers, it was Mr.

Owen they asked to go with them at their head.

It was he who first taught the people the then strange truth

that Causation was the law of nature on the mind, and unless we looked for

the cause of an evil we might never know the remedy. Every man of

sense in Church and State acts on this truth now, but so few knew it in

Owen's day that he was accused of unsettling the morality of the world.

It was the fertility and newness of his suggestions, as a man of affairs,

that gave him renown, and his influence extends to us. This Memorial

before us would itself grow old were we to stay to describe all the ideas

the world has accepted from Owen. I will name but one more, and that

the greatest.

He saw, as no man before him did, that environment is the

maker of men. Aristotle, whose praise is in all our Universities,

said "Character is Destiny." But how can character be made?

The only national way known in Owen's day was by prayer and precept.

Owen said there were material means, largely unused, conducive to human

improvement. Browning's prayer was—"Make no more giants, God; but

elevate the race at once." This was Owen's aim, as far as human

means might do it. Great change can only be effected by unity.

But—

|

"Union without knowledge is useless;

Knowledge without union is powerless." |

Then what is the right knowledge? Owen said it

consisted in knowing that people came into the world without any intention

of doing it; and often with limited capacities, and with disadvantages of

person, and with instinctive tendencies which impel them against their

will, disqualifications which they did not give themselves. He was

the first philosopher who changed repugnance into compassion, and taught

us to treat defects of others with sympathy instead of contempt, and to

remedy their deficiency, as far as we can, by creating for them amending

conditions. Dislike dies in the heart of those who understand this,

and the spirit of unity arises. Thus instructed good-will becomes

the hand-maid of Co-operation, and Co-operation is the only available

power of industry. Since error arises more from ignorance of facts

than from defect of goodness, the reformer with education at command,

knows no despair of the betterment of men. This was the angerless

philosophy of Owen, which inspired him with a forbearance that never

failed him, and gave him that regnant manner which charmed all who met

him. We shall see what his doctrine of environment has done for

society, if we notice what it began to do in his day, and what it has done

since.

Men perished by battle, by tempest, by pestilence.

Faith might comfort, but it did not save them. In every town nests

of pestilence coexisted with the Churches, which were concerned alone with

worship. Disease was unchecked by devotion. Then Owen asked,

"Might not safety come by improved material condition?" As the

prayer of hope brought no reply, as the scream of agony, if heard, was

unanswered, as the priest, with the holiest intent, brought no

deliverance, it seemed prudent to try the philosopher and the physician.

Then Corn Laws were repealed, because prayers fed nobody.

Then parks were multiplied, because fresh air was found to be a condition

of health. Alleys and courts were first abolished, since deadly

diseases were bred there. Streets were widened, that towns might be

ventilated. Hours of labour were shortened, since exhaustion means

liability to epidemic contagion. Recreation was encouraged, as

change and rest mean life and strength. Temperance—thought of as

self-denial—was found to be a necessity, as excess of any kind in diet, or

labour, or pleasure means premature death. Those who took dwellings

began to look, not only to drainage and ventilation, but to the ways of

their near neighbours, as the most pious family may poison the air you

breathe unless they have sanitary habits.

|

|

|

The Owen Memorial at Newtown

Unveiled by G. J. Holyoake, July 12th, 1902 |

Thus, thanks to the doctrine of national environment which

Owen was the first to preach—Knowledge is greater; Life is longer; Health

is surer; Disease is limited; Towns are sweeter; Hours of labour are

shorter; Men are stronger; Women are fairer; Children are happier;

Industry is held in more honour, and is better rewarded; Co-operation

carries wholesome food and increased income into a million homes where

they were unknown before, and has brought us nearer and nearer to that

state of society which Owen strove to create—in which it shall be

impossible for men to be depraved or poor. Thus we justify ourselves

for erecting this Memorial to his memory, which I am about to unveil.

The town has erected a Public Library opposite the house in

which Mr. Owen was born, to which the Co-operators subscribed £1,000.

One part of the Library bears the name of Owen's Wing.

CHAPTER VII.

THE ENTHUSIASTIC PERIOD. 1820-1830

|

"Then felt I like some watcher of the skies,

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez, when with eagle eyes

He stared on the Pacific; and his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise,

Silent upon a peak in Darien."—KEATS.

|

THE enchanted wonder which Keats describes on first

finding in Chapman's Homer the vigorous Greek texture of the great bard,

was akin to that "wild surmise" with which the despairing sons of industry

first gazed on that new world of Co-operation then made clear to their

view.

To the social reformers the world itself seemed moving in the

direction of social colonies. Not only was America under way for the

millennium of co-operative life—even prosaic, calculating, utilitarian

Scotland was setting sail. France had put out to sea years before

under Commander Fourier. A letter arrived from Brussels, bearing date

October 2, 1825, addressed to the "Gentlemen of the London Co-operative

Society," telling them that the Permanent Committee of the Society of

Beneficence had colonial establishments at Wortzel and at Murxplus

Ryckewvorsel, in the province of Antwerp, where 725 farmhouses were

already built; that 76 were inhabited by free colonists; and that they had

a contract with the Government for the suppression of mendicants, and had

already 455 of those interesting creatures collected from the various

regions of beggardom in a depot, where 1,000 could be accommodated.

No wonder there was exultation in Red Lion Square when the slow-moving,

dreamy-eyed, much smoking Dutch were spreading their old-fashioned canvas

in search of the new world. From 1820 to 1830 Co-operation and

communities were regarded by the thinking classes as a religion of

industry. Communities, the form which the religion of industry was

to take, were from 1825 to 1830 as common and almost as frequently

announced as joint-stock companies now. In 1826 April brought news

that proposals were issued for establishing a community near Exeter—to be

called the Devon and Exeter Co-operative Society. Gentlemen of good

family and local repute, who were not, as some are now, afraid to look at

a community through one of Lord Rosse's long-range telescopes, gave open

aid to the proposal. Two public meetings were held in May, at the

Swan Tavern. The Hon. Lionel Dawson presided on both occasions.

Such was the enthusiasm about the new system that more than four hundred

persons were willing to come forward with sums of £5 to £10; one hundred

others were prepared to take shares at £25 each; and two or three promised

aid to the extent of £2,000. Meetings in favour of this project were

held at Tiverton, and in the Mansion House, Bridgewater. The zeal

was real and did not delay. In July the promoters bought thirty

seven acres of land within seven miles of Exeter. A gardener, a

carpenter, a quarrier (there being a stone quarry on the estate), a

drainer, a well-sinker, a clay temperer, and a moulder were at once set to

work.

The Metropolitan Co-operative Society, not to be behind when

the provinces were going forward, put forth a plan for establishing a

community within fifty miles of London. Shares were taken up and

£4,000 subscribed in 1826. There was a wise fear of prematurity of

proceeding shown, and there was also an infatuation of confidence

exhibited in many ways. However, the society soberly put out an

advertisement to landowners, saying, "Wanted to rent, with a view to

purchase, or on a long lease, from 500 to 2,000 acres of good land, in one

or several contiguous farms; the distance from London not material if the

offer is eligible." Information was to be sent to Mr. J. Corss, Red

Lion Square. Four years earlier Scotland, a country not at all prone

to Utopian projects not likely to pay, entertained the idea of community

before Orbiston was named. The Economist announced that the

subscriptions for the formation of one of the new villages at Motherwell,

though the public had not been appealed to, amounted to £20,000. [44]

Eighteen hundred and twenty-six was a famous year for

communistic projects. A Dublin Co-operative Society was formed on

the 28th of February, at a meeting held at the Freemasons' Tavern, Dawson

Street, Dublin. Captain O'Brien, R.N., occupied the chair. The

Dublin Co-operative Society invited Lord Cloncurry to dine with them.

His lordship wrote to say that he was more fully convinced than he was

four years ago, of the great advantage it would be to Ireland to establish

co-operative villages on Mr. Owen's plan, and spoke of Mr. Owen in curious

terms as the "benevolent and highly-respectable Owen." This was nine

years after Mr. Owen had astounded mankind by his London declaration

"against all the religions of the world." [45]

Two years before the Economist appeared, as the first

serial advocate of Co-operation, pamphleteers were in the field on behalf

of social improvement. Mr. Owen certainly had the distinction of

inspiring many writers. One "Philanthropos" published in 1819 a

powerful pamphlet on the "Practicability of Mr. Owen's plan to improve the

condition of the lower classes." It was inscribed to William

Wilberforce (father of the Bishop of Winchester), whom the writer

considered to be "intimately associated with every subject involving the

welfare of mankind," and who "regarded political measures abstractedly

from the individuals with whom they originated." Mr. Wilberforce, he

said, had shown that "Christianity steps beyond the narrow bound of

national advantage in quest of universal good, and does not prompt us to

love our country at the expense of our integrity." [46]

The Economist was concluded in January, 1822. It

was of the small magazine size, and was the neatest and most

business-looking journal issued in connection with Co-operation for many

years. After the 32nd number the quality and taste of the printing

fell off—some irregularity in its issue occurred. Its conductor

explained in the 51st number that its printing had been put into the hands

of the Co-operative and Economical Society, "and that it would continue to

be regularly executed by them." After the 52nd number the

Economist was discontinued, without any explanation being given.

It was bound in two volumes, and sold at 7s. each in boards. Many

numbers purported to be "published every Saturday morning by Mr. Wright,

bookseller, No. 46, Fleet Street, London, where the trade and newsmen may

be supplied, and where orders, communications to the editor, post paid,

are respectfully requested to be addressed." Early numbers bore the

name of G. Auld, Greville Street. With No. 22 the names appear of J.

and C. Adlard, Bartholomew Close. With No. 32 the imprint is "G.

Mudie, printer"—no address. After No. 51 the intimation

is—"Printed at the Central House of the Co-operative and Economical

Society, No. 1, Guilford Street East, Spafields."

Twelve years later, when the Gazette of the Exchange

Bazaars was started, a fly-leaf was issued, which stated, "This work

will be conducted by the individual who founded the first of the

co-operative societies in London, 1820, and who edited the Economist,

in 1821-22, the Political Economist and Universal Philanthropist,

in 1823, the Advocate of the Working Classes, in 1826-27; and who

has besides lectured upon the principles to be discussed in the

forthcoming publication (The Exchange Bazaars Gazette), in various

parts of Great Britain. He enters on his undertaking, therefore,

after having been prepared for his task by previous and long-continued

researches." Mr. Owen never thought much of co-operative societies,

regarding grocers' shops as ignominious substitutes for the reconstruction

of the world.

The dedication of the Economist was as follows:—

"To Mr. John Maxwell, Lord Archibald

Hamilton, Sir William de Crespigny, Bart., Mr. Dawson, Mr. Henry Brougham,

Mr. H. Gurney, and Mr. William Smith, the philanthropic members of the

House of Commons, who, on the motion of Mr. Maxwell, on the 26th of June,

1821, for an address to the throne, praying that a commission might be

appointed to investigate Mr. Owen's system, had the courage and

consistency to make the motion; this volume is inscribed in testimony of

heartfelt respect and gratitude by THE

ECONOMIST."

The earliest name of literary note connected with

Co-operation was that of Mr. William Thompson. He was an abler man

than John Gray. Though an Irishman, he was singularly dispassionate.

He possessed fortune and studious habits. He resided some years with

Jeremy Bentham, and the methodical arrangement of his chief work, the

"Distribution of Wealth," betrays Bentham's literary influence. This

work was written in 1822. In 1825 he published "An Appeal of

one-half the human race—Women—against the pretensions of the other

half—Men." It was a reply to James Mill—to a paragraph in his

famous "Article on Government." Mr. Thompson issued, in 1827,

"Labour Rewarded," in which he explained the possibility of conciliating

the claims of labour and capital and securing to workmen the "whole

products of their exertions." This last work consisted of

business-like "Directions for the Establishment of Co-operative

Communities." These "directions" were accompanied by elaborate plans

and tables. A moderate number of pioneers might, with that book in

their hand, found a colony or begin a new world. He consulted

personally Robert Owen, Mr. Hamilton (whom he speaks of as an authority),

Abram Combe, and others who had had experience in community-making.

Jeremy Bentham's wonderful constitutions, which he was accustomed to

furnish to foreign states, were evidently in the mind of his disciple, Mr.

Thompson, when he compiled this closely-printed octavo volume of nearly

three hundred pages. He placed on his title-page a motto from Le

Producteur: "The age of Gold, Happiness, which a blind credulity has

placed in times past is before us." The world wanted to see the

thing done. It desired, like Diogenes, to have motion proved.

In practical directions for forming communities exhaustive instructions

were precisely the things needed. Where every step was new and every

combination unknown, Thompson wrote a book like a steam engine, marvellous

in the scientific adjustments of its parts. His "Distribution of

Wealth" is the best exposition to which reference can be made of the

pacific and practical nature of English communism. He was a solid

but far from a lively writer. It requires a sense of duty to read

through his book—curiosity is not sufficient. Political economists

in Thompson's day held, as Mr. Senior has expressed it, that "It is not

with happiness but with wealth that I am concerned as a political

economist." Thompson's idea was "to inquire into the principles of

the distribution of wealth most conducive to human happiness."

His life was an answer to those who hold that Socialism implies

sensualism. For the last twenty years of his life he neither partook

of animal food nor intoxicating drinks, because he could better pursue his

literary labours without them. He left his body for dissection—a

bold thing to do in his time—a useful thing to do in order to break

somewhat through the prejudices of the ignorant against dissection for

surgical ends. Compliance with his wish nearly led to a riot among

the peasantry of the neighbourhood of Clonnkeen, Rosscarbery, County of

Cork, where he died.

Another early and memorable name in co-operative history is

that of Abram Combe. It is very rarely that a person of any other

nationality dominates the mind of a Scotchman; but Mr. Owen, although a

Welshman, did this by Abram Combe, who, in 1823, published a small book

named "Old and New Systems"—a work excelling in capital letters.

This was one of Mr. Combe's earliest statements of his master's views,

which he reproduced with the fidelity which Dumont showed to Bentham, but

with less ability. There were three Combes—George, Abram, and

Andrew. All were distinguished in their way, but George became the

best known. George Combe was the phrenologist, who made a reputation

by writing the "Constitution of Man," though he had borrowed without

acknowledgment the conception from Gall and Spurzheim, especially

Spurzheim, who had published an original little book on the "Laws of Human

Nature"; but to George Combe belonged the merit which belonged to

Archdeacon Paley with respect to the argument from design. Combe

restated, animated, and enlarged into an impressive volume what before was

fragmentary, slender, suggestive, but without the luminous force of

illustrative facts and practical applications which Combe supplied.

The second brother, Dr. Andrew Combe, had all the talent of the family for

exposition, and his works upon physiology were the first in interest and

popularity in their time; but Abram had more sentiment than both the

others put together, and ultimately sacrificed himself as well as his

fortune in endeavours to realise the new social views in practice.

In 1824 Robert Dale Owen (Mr. Owen's eldest son) appeared as

an author for the first time. His book was entitled "An Outline of

the System of Education at New Lanark." It was published by Longman

& Co., London, written at New Lanark, 1823. It was dedicated to his

father. The author must have been a young man then. [47]

Yet his book shows completeness of thought and that clear and graceful

expression by which, beyond all co-operative writers, Robert Dale Owen was

subsequently distinguished. His outline is better worth printing now

than many books on New Lanark which have appeared; it gives so interesting

a description of the construction of the schools, the methods and

principles of tuition pursued. The subjects taught to the elder

classes were the earth (its animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms),

astronomy, geography, mathematics, zoology, botany, mineralogy,

agriculture, manufactures, architecture, drawing, music, chemistry, and

ancient and modern history. The little children were occupied with

elementary education, military drill, and dancing, at which Mr. Owen's

Quaker partners were much discomfited. The schoolrooms were picture

galleries and museums. Learning ceased to be a task and a terror,

and became a wonder and delight. The reader who thinks of the

beggarly education given by this wealthy English nation will feel

admiration of the princely mind of Robert Owen, who gave to the children

of weavers this magnificent scheme of instruction. No manufacturer

has arisen in England so great as he.

The London Co-operative Society was formally commenced in

October, 1824. It occupied rooms in Burton Street, Burton Crescent.

This quiet, and at that time pleasant and suburban, street was quite a

nursery-ground of new-born principles. Then, as now, it had no

carriage way at either end. In the house at the Tavistock Place

corner, lived for many years James Pierrepoint Greaves, the famous mystic.

As secluded Burton Street was too much out of the way for the convenience

of large assemblages, the discussions commenced by the society there, were

transferred to the Crown and Rolls Rooms, in Chancery Lane. Here

overflowing audiences met—political economists seem to have been the

principal opponents. Their chief argument against the new system,

was the Malthusian doctrine against "the tendency of population to press

against the means of subsistence."

In the month of April, 1825, the London Co-operative Society

hired a first-floor in Picket Street, Temple Bar, for the private meetings

of members, who were much increasing at that time. In November of

the same year, 1825, the society took the house, No. 36, Red Lion Square.

Mr. J. Corss was the Secretary. The London Co-operative Society held

weekly debates. One constant topic was the position taken by Mr.

Owen—that man is not properly the subject of praise or blame, reward or

punishment. It also conducted bazaars for the sale of goods

manufactured by the provincial societies.

At New Harmony, Indiana, David Dale Owen, writing to his

father, related that they had had debates there, and Mary and Jane,

daughters or daughter-in-laws of Mr. Owen, both addressed the meetings on

several occasions. After all the discourses opportunity of

discussion and questioning was uniformly and everywhere afforded.

The second serial journal representing Co-operation appeared

in America, though its inspiration was English. It was the New

Harmony Gazette. Its motto was: "If we cannot reconcile all

opinions let us endeavour to unite all hearts."

The recommencement of a co-operative publication in England

took place in 1826. The first was entitled the Co-operative

Magazine and Monthly Herald, and appeared in January. It was

"printed by Whiting and Branston, Beaufort House, Strand," and "published

by Knight and Lacey, Watt's Head, Paternoster Row." It purported to

be "sold by J. Templeman, 39, Tottenham Court Road; and also at the office

of the London Co-operative Society, 36, Red Lion Square." The second

number of this magazine was published by Hunt and Clark, Tavistock Street.

A change in the publisher occurred very early, and additional agents were

announced as J. Sutherland, Calton Street, Edinburgh; R. Griffin & Co.,

Hutchinson Street, Glasgow; J. Bolstead, Cork; and A. M. Graham, College

Green, Dublin. The third number announced a change in the Cork

publisher; J. Loftus, of 107, Kirkpatrick Street, succeeded Mr. Bolstead,

and a new store, the "Orbiston Store," was for the first time named. [48]

The co-operative writers of this magazine were not wanting in candour even

at their own expense. Mr. Charles Clark relates "that while one of

the New Harmony philosophers was explaining to a stranger the beauties of

a system which dispensed with rewards and punishments, he observed a boy

who approved of the system busily helping himself to the finest plums in

his garden. Forgetting his argument, he seized the nearest stick at

hand and castigated the young thief in a very instructive manner." [49]

The worthy editor of the Co-operative Magazine was one

of the fool friends of progress. In his first number he gravely

reviews a grand plan of one James Hamilton, for rendering "Owenism

Consistent with our Civil and Religious Institutions." His proposal

is to begin the new world with one hundred tailors, who are to be

unmarried and all of them handsome of person. Hamilton proposed to

marry all the handsome tailors by ballot to a similar number of girls.

After sermon and prayer the head partner and minister, assisted by foremen

of committees, were to put the written names of the men in one box and

those of the girls in another. The head partner was then to mix the

male names and the minister the female names. When a man's name was

proclaimed aloud, the minister was immediately to draw out the name of a

girl from his box. The couple were then requested to consider

themselves united by decision of heaven. By this economical

arrangement young couples were saved all the anxiety of selection, loss of

time in wooing, the suspense of soliciting the approval of parents or

guardians. The distraction of courtship, sighs, tears, smiles,

doubts, fears, jealousies, expectations, disappointments, hope and despair

were all avoided by this compendious arrangement. How any editor,

not himself an out-patient of a lunatic asylum, could have occupied pages

of the Co-operative Magazine by giving publicity to such a pamphlet

more ineffably absurd than here depicted, it is idle to conjecture.

Could this be the Mr. Hamilton, of Dalzell, who joined Mr. Abram Combe in

the purchase of Orbiston for £20,000, and who offered to let lands at

Motherwell for a community, and to guarantee the repayment of £40,000 to

be expended on the erection of the buildings?

Apart from the eccentric views which we have recounted (if

indeed they were his) Mr. Hamilton was distinguished for the great

interest he took in co-operative progress and the munificence by which he

assisted it. In the projected community of Motherwell he was joined

by several eminent men, who had reason to believe that a large and

well-supported co-operative colony might be made remunerative, besides

affording to the Government of the day a practical example of what might

be done. Several gentlemen in England subscribed many thousands each

in furtherance of this project. Mr. Morrison, of the well-known firm

of Morrison and Dillon, was one of those who put down his name for £5,000.

The Co-operative Magazine of 1826 was adorned by an

engraving of Mr. Owen's quadrilateral community. The scenery around

it was mountainous and tropical. The said scenery was intended to

represent Indiana, where Mr. Owen had bought land with a view to introduce

the new world in America. Mr. A. Brisbane prefixes to his

translation of Fourier's "Destiny of Man" the Fourier conception of a

phalanstere. Mr. Owen's design of a community greatly excelled the

phalanstere in completeness and beauty. Mr. A. Combe exhibited

designs of his Scotch community at Orbiston, but Mr. Owen had the most

luxuriant imagination this way. Artists who came near him to execute

commissions soon discovered that the materialist philosopher, as they

imagined him, had no mean taste for the ideal.

Lamarck's theory of the "Origin of Species" was introduced

into the Co-operative Magazine—a harmless subject certainly, but

one that was theologically mischievous for forty years after.

"Scripture Politics" was another topic with which co-operators afflicted

themselves. "Phrenology," another terror of the clergy, appeared.

Discussions upon marriage followed, but, as the co-operators never

contemplated anything but equal opportunities of divorce for rich and

poor, the subject was irrelevant. The editor actually published

articles on the "Unhappiness of the Higher Orders," [50]

and provided remedies for it, as though that was any business of theirs.

It was time enough for readers to sigh over the griefs of the rich when

they had secured the gladness of the poor.

In those days a practical agitator (Carlile), who had the

courage to undergo long years of imprisonment to free the press, thought

the world was to be put right by a science of "Somatopsychonoologia." [51]

There were co-operators—Allen Davenport, the simple-hearted ardent

advocate of agrarian views, among them—who were prepared to undertake

this nine-syllabled study.

Every crotcheteer runs at the heels of new pioneers.

Co-operative pages advocated the "Civil Rights of Women," to which they

were inclined from a sense of justice; and the advocates of that question

will find some interesting reading in co-operative literature. Their

pages were open to protest against the game laws. The

Co-operative Magazine gave almost as much space to the discussion of

the ranunculus, the common buttercup, as it did to the "new system of

society." The medical botanists very early got at the poor

co-operators. A co-operative society was considered a sort of free

marketplace, where everybody could deposit specimens of his notions for

inspection or sale.

In 1827, a gentleman who commanded great respect in his day,

Mr. Julian Hibbert, printed a circular at his own press on behalf of the

"Co-operative Fund Association." He avowed himself as "seriously

devoted to the system of Mr. Owen": and Hibbert was a man who meant all he

said and who knew how to say exactly what he meant. Here is one

brief appeal by him to the people, remarkable for justness of thought and

vigorous directness of language:

"Would you be free? be worthy of

freedom: mental liberty is the pledge of political liberty. Unlearn

your false knowledge, and endeavour to obtain real knowledge. Look

around you; compare all things; know your own dignity; correct your

vicious habits; renounce superfluities; despise idleness, drunkenness,

gambling, and fighting; guard against false friends; and learn to think

(and if possible to act) independently."

This language shows the rude materials out of which co-operators had

sometimes to be made. In personal appearance Julian Hibbert

strikingly resembled Shelley. He had at least the courage, the

gentleness, and generosity of the poet. Hibbert had ample fortune,

and was reputed one of the best Greek scholars of his day. Being

called upon to give evidence on a trial in London, he honestly declined to

take the oath on the ground that he did not believe in an Avenging God,

and was therefore called an atheist, and was treated in a ruffianly manner

by the eloquent and notorious Charles Phillips, who was not a man of

delicate scruples himself, being afterwards accused of endeavouring to fix

the guilt of murdering Lord William Russell upon an innocent man, after

Couvoisier had confessed his guilt to him. Hibbert's courage and

generosity was shown in many things. He visited Carlile when he was

confined in Dorchester Gaol for heresy, and on learning that a political

prisoner there had been visited by some friend of position who had given

him £1,000, Hibbert at once said: "It shall not appear, Mr. Carlile, that

you are less esteemed for vindicating the less popular liberty of

conscience. I will give you £,1000." He gave Mr. Carlile the

money there and then. It was Mr. Hibbert's desire in the event of

his death that his body should be at the service of the Royal College of

Surgeons, being another of those gentlemen who thought it useful by his

own example to break down the prejudice of the poor, against their remains

being in some cases serviceable to physiological science. This

object was partly carried out in Mr. Hibbert's case by Mr. Baume.

Some portion of Mr. Hibbert's fortune came into possession of Mrs. Captain

Grenfell, a handsome wild Irish lady after the order of Lady Morgan.

Mr. Hibbert's intentions, however, seem to have been pretty faithfully

carried out, for thirty years after his death I was aware of five and ten

pound notes occasionally percolating into the hands of one or other

unfriended advocate of unpopular forms of social and heretical liberty,

who resembled the apostles at least in one respect—they had "neither

purse nor scrip."

During 1827, and two years later, the Co-operative

Magazine was issued as a sixpenny monthly. All the publications

of this period, earlier and later, were advertised as being obtainable at

19, Greville Street, Hatton Garden, then a co-operative centre, and at

co-operative stores in town and country. If all stores sold the

publication then it proved that they better understood the value of

special co-operative literature than many do now.

It was on May 1, 1828, that the first publication appeared

entitled the Co-operator. It was a small paper of four pages

only, issued monthly at one penny. It resembled a halfpenny

two-leaved tract. The whole edition printed would hardly have cost

thirty shillings if none were sold. [52]

It was continued for twenty-six months, ceasing on August 1, 1830.

The twenty-six numbers consisted of twenty-six papers, all written by the

editor, Dr. King, who stated that they were concluded because "the object

for which they were commenced had been attained. The principles of

Co-operation had been disseminated among the working classes and made

intelligible to them." This was not true twenty years later, but

everybody was sanguine in those days, and saw the things which were not,

more clearly than the things which were. [53]

The chief cause of failure which the editor specifies as having overtaken

some co-operative societies was defect in account keeping. Of

course, as credit was customary in the early stores, accounts would be the

weak point with workmen. Dr. King wrote to Lord (then Henry)

Brougham, M.P., an account of the Brighten co-operators. Lord

Brougham asked Mr. M. D. Hill to bring the matter of Co-operation before

the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Timid members on

the council were afraid of it, as many councils are still. It would

have been one of the most memorable papers of that famous society had they

treated this subject. They never did treat any original subject, and

this would have been one.

Mr. Craig, who had extensive personal knowledge of early

societies, states that one was formed at Bradford in 1828. A stray

number of the Brighton Co-operator (the one edited by Dr. King),

soiled and worn, found its way into Halifax, and led to the formation of

the first co-operative society there, owing to the foresight and devotion

to social development of Mr. J. Nicholson, a name honourably known, and

still remembered with respect, in Halifax. His son-in-law, Mr. David

Crossley, of Brighouse, all his life manifested intelligent and untiring

interest in Co-operation.

The first Birmingham co-operative rules were framed in 1828

by Mr. John Rabone, a well-known commercial name in that town, who was a

frequent writer in early co-operative years. The reports of the

early success of the Orbiston community reached Birmingham, and had great

influence there. Some who had seen the place gave so good an account

of it, that it was the immediate cause of the first Birmingham

co-operative society being formed.

On January 1, 1829, the first number of the Associate

was issued, price one penny, "published at the store of the first London

Co-operative Trading Association, 2, Jerusalem Passage, Clerkenwell."

The Associate, a well-chosen name, modestly stated that it was "put

forth to ascertain how far the working class were disposed to listen to

its suggestion of means by which they themselves may become the authors of

a lasting and almost unlimited improvement of their own condition in

life." The Associate was from the beginning a well-arranged,

modest little periodical, and it was the first paper to summarise the

rules of the various co-operative associations.

The author of "Paul Clifford" takes the editor of the

British Co-operator by storm, who states that this work bids fair to

raise Mr. Bulwer to that enviable pinnacle of fame which connects the

genius of the author with the virtues of the citizen, the philanthropist

with the profundity of the Philosopher. [54]

The Society for the Promotion of Co-operative Knowledge held

regular quarterly meetings, commencing in 1829. They were reported

with all the dignity of a co-operative parliament in the Weekly Free

Press, a Radical paper of the period. The proceedings were

reprinted in a separate form. This society bore the name of the

British Association for Promoting Co-operative Knowledge first in 1830.

This publication, entitled The Weekly Free Press, was

regarded as a prodigy of newspapers on the side of Co-operation. The

editor of the aforesaid British Co-operator described it as "an

adamantine bulwark, which no gainsayer dare run against without suffering

irretrievable loss." No doubt "gainsayers" so warned, prudently kept

aloof, but the "adamantine journal" ran down itself, suffering

irretrievable loss in the process.

No one could accuse the early co-operators of being wanting

in large ideas. It was coolly laid down, without any dismay at the

magnitude of the undertaking, that the principles of Co-operation were

intended to secure equality of privileges for all the human race.

That is a task not yet completed.

In addition they made overtures to bring about the general

elevation of the human race, together with univeral knowledge and

happiness. Ten years before the British Association for the

Advancement of Science was devised in Professor Phillips's Tea-room in the

York Museum, and forty years before Dr. Hastings ventured to propose to

Lord Brougham the establishment of a National Association for the

Promotion of Social Science, the Co-operative Reformers set up, in 1829, a

"British Association for Promoting Co-operative Knowledge." It had

its quarterly meetings, some of which were held in the theatre of the

Mechanics' Institution, Southampton Buildings, Chancery Lane, London,

known as Dr. Birkbeck's Institution. The speeches delivered were

evidently studied and ambitious, far beyond the character of modern

speeches on Co-operation, which are mostly businesslike, abrupt, and

blunt. Among those at these early meetings were Mr. John Cleave,

well known as a popular newsvendor—when only men of spirit dare be

newsvendors—whose daughter subsequently married Mr. Henry Vincent, the

eminent lecturer, who graduated in the fiery school of "Chartism,"

including imprisonment. Mr. William Lovett, a frequent speaker, was

later in life imprisoned with John Collins for two years in Warwick Gaol,

where they devised, wrote, and afterwards published the best book on the

organisation and education of the Chartist party ever issued from that

body [ED.—"Chartism: A New Organization of The People"]. Mr.

Lovett made speeches in 1830 with that ornate swell in his sentences with

which he wrote resolutions at the National Association, in High Holborn,

twenty years later, when W. J. Fox delivered Sunday evening orations

there. Mr. Lovett was the second secretary of the chief co-operative

society in London, which met at 19, Greville Street, Hatton Garden.

The fourth report of the British Co-operative Association

announced the Liverpool, Norwich, and Leeds Mercuries; the

Carlisle Journal, the Newry Telegraph, the Chester

Courant, the Blackburn Gazette, the Halifax Chronicle,

besides others, as journals engaged in discussing Co-operation. The

Westmoreland Advertiser is described as devoted to it. [55]

The first Westminster co-operative society, which met in the

infant schoolroom, gave lectures on science. Mr. David Mallock,

A.M., delivered a lecture on "Celestial Mechanics"; Mr. Dewhurst, a

surgeon, lectured on "Anatomy," and complaint was made that he used Latin

and Greek terms without translating them. [56]

The British Co-operator, usually conducted with an editorial sense

of responsibility, announced to its readers that "it is confidently said

that Mr. Owen will hold a public meeting in the City of London Tavern,

early in Easter week; and it is expected that his Royal Highness the Duke

of Sussex will take the chair. We have no doubt it will be well

attended and produce a great sensation among the people." This

premature announcement was likely to deter the Duke from attending.

The first London co-operative community is reported as

holding a meeting on the 22nd of April, 1829, at the Ship Coffee-house,

Featherstone Street, City Road. Mr. Jennison spoke, who gave it as

his conviction that the scheme could be carried out with £5 shares,

payable at sixpence per week. [57]

The first Pimlico Association was formed in December, 1829.

Its store was opened on the 27th of February, 1830, and between that date

and the 6th of May it had made £32 of net profit. Its total property

amounted to £140. Its members were eighty-two.

The first Maidstone co-operative society was in force in

1830, and held its public meetings in the Britannia Inn, George Street.

A Rev. Mr. Pope, of Tunbridge Wells, gave them disquietude by

crying—"Away with such happiness [that promised by Co-operation] as is

inconsistent with the gospel." As nobody else promised any happiness

to the working men, Mr. Pope might as well have left them the consolation

of hoping for it. He would have had his chance when they got the

happiness, which yet lags on its tardy way.

In 1830 Mr. J. Jenkinson, "treasurer of the Kettering

Co-operative Society," confirmed its existence by writing an ambitious

paper upon the "Co-operative System."

England has never seen so many co-operative papers as 1830

saw. Since the Social Economist was transferred to the

promoters of the Manchester Co-operative News Company, in 1869,

there has been even in London no professed co-operative journal.

The Agricultural Economist, representing the

Agricultural and Horticultural Association, is the most important-looking

journal which has appeared in London in the interests of

Co-operation—"Associative Topics" formed a department in this paper.

In 1830, when the Co-operative Magazine was four years

old, the Co-operative Miscellany (also a monthly magazine)

commenced, and with many defects, had more popular life in it than any

other. The editor was, I believe, the printer of his paper.

Anyhow, he meant putting things to rights with a vigorous hand. His

Miscellany afterwards described itself as a "Magazine of Useful

Knowledge"; a sub-title, borrowed, apparently, from the Society for the

Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, then making a noise in the world. The

editor of this Miscellany held that co-operative knowledge should

be placed first in the species useful. It was then a novel order of

knowledge. The Miscellany was of the octavo size; the

typographical getting-up was of the provincial kind, and the title-page

had the appearance of a small window-bill. It was printed by W.

Hill, of Bank Street, Maidstone. The editor professed that his

magazine contained a development of the principles of the system.

The allusion evidently was to Mr. Owen's system. Of the people he

says "many of them are beginning to feel the spark of British independence

to glow." He tells us that some "are moving onwards towards the

diffusion of the views of Mr. Owen, of New Lanark, now generally known as

the principles of Co-operation."

Speaking of the meeting of the British Co-operative

Association, at which Mr. Owen spoke, "who was received with enthusiastic

and long-continued cheering," the editor of the Co-operative Miscellany,

said: "The theatre was filled with persons of an encouraging and

respectable appearance." Persons of an "encouraging appearance" are

surely one of the daintiest discoveries of enthusiasm.

At this time Mr. Owen held Sunday morning lectures in the

Mechanics' Institution, followed, says this Miscellany "by a

conversazione at half-past three o'clock, and a lecture in the evening."

Early in 1830 appeared, in magazine form, the British

Co-operator, calling itself also "A Record and Review of Co-operative

and Entertaining Knowledge." This publication made itself a business

organ of the movement, and addressed itself to the task of organising it.

To the early stores it furnished valuable advice, and the sixth number

"became a sort of text-book to co-operators." No. 22 had an article

which professed to be "from the pen of a gentleman holding an important

office in the State," and suggested that intending co-operators should

bethink themselves of bespeaking the countenance of some patron in the

infancy of their Co-operation—the clergyman of the parish, or a resident

magistrate, who might give them weights and scales and a few shelves for

their store shop. The members were to sign an arbitration bond,

under which all questions of property in the society shall be finally

decided by the patron, who must not be removable, otherwise than by his

own consent. The plan might have led to the extension of

Co-operation in rural districts. And as the authority of the patron

was merely to extend to questions of property when no law existed for its

protection, the members would have had their own way in social

regulations. All the patron could have done would have been to take

away his scales, weights, and shelves. A very small fund, when the

society was once fairly established, would have enabled them to have

purchased or replaced these things. The British Association for

Promoting Co-operative Knowledge, published in the Weekly Free Press

a special protest against "patrons of any sort, especially the clergyman

or the magistrate." The early socialists spoke with two voices.

With one they denounced the wealthier classes as standing aloof from the

people and lending them no kind of help, and with the other described them

as coming forward with "insidious plans" of interference with them.

It was quite wise to counsel the working classes "to look to themselves

and be their own patrons," but it was not an encouraging thing to

gentlemen to see one of their order "holding an important office in the

State," kicked, "by order of the committee," for coming forward with what

was, for all they knew, a well-meant suggestion.

The British Co-operator prepared articles for the

guidance of trustees and directors or committees of co-operative

societies. It gave them directions how to make their storekeeper a

responsible and punishable person. How to procure licences.

How to execute orders and schemes of book-keeping. It usefully

remarked: "We regret that the neglect of the first Bloomsbury society to

take legal measures to secure their property has deprived them of the