|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER V.

The nightmare life-in-death.—COLERIDGE.

NOT many days

after, Sarah Russell, as she sat at the window of the Rood Hotel,

was struck with the unoccupied appearance of a large house on the

opposite side of the Hallowgate Square. There were some dingy yellow

blinds and heavy crimson curtains at the windows of the

second-floor, but those of the parlours and the first flat were left

staring blankly like those of an empty house. She called up Mrs.

Stone and enquired if she had heard who lived there.

'Just one old gentleman, of the name of Halliwell,' Mrs. Stone

replied. 'Just himself and a woman to wait on him. The housekeeper

was mentioning that house in particular when she was a-talking over

the changes for the worse that have been in the Hallowgate, ma'am. For

she says the housekeeper that was before her told her that she had

known it as a family residence, with two maids and a man, and gas

and fire in every room. The housekeeper says she don't

recollect hearing what it was that happened, but it was something

peculiar, one or two sudden deaths, or something of that sort, so

that the master was left by himself, and got strange-like, and

turned off his servants; and they say he packed all the furniture

into the attics, except what he uses himself. For years and

years he had up a board that the parlours and first-floor were to be

let; but one stormy day it was blown down, and it was never put up

again, as was little use, since, as Housekeeper says, this is too

out-of-the-way for most offices, and folks won't live in this kind

of place now, though the rooms is beautiful, far better than these,

and the outlook at the back is pleasant for London, having a tree in

sight, and no high house near, but just the back-yards and

outbuildings of that little Crosier Street, that runs up beside it.'

'Mrs. Stone,' said Sarah, 'I wish you would go across to the

house and explain what you have heard about the notice-board, and

enquire if the rooms are still to be let to a suitable tenant whom

they might suit.'

'Certainly I will, ma'am', said Mrs. Stone; and may I make

bold to ask if you are thinking of taking them yourself, if so be

they are agreeable?'

'I think we might easily go farther and fare worse,' Miss

Russell answered. 'I should really like to stay in this

neighbourhood, for it is a quiet and pleasant place, and not too far

from my cousin, Miss Tibbie. I suppose you'll have no

objection to a service in the City, Mrs. Stone?'

'Indeed, and I'd just be uncommonly sorry to leave the

Hallowgate again,' said Mrs. Stone. 'One does not know what

one may lose while one's gadding about. Only last evening I

went down our old court again, and dropped upon an old neighbour and

introduced myself. And what do you think, ma'am? within this

last month there's been a man making enquiries for me. He

didn't ask after me in my married name, but he seemed to know I were

married, for he asked if anybody knew anything about a woman who had

been Annie Baker in her maiden days. And of course nobody knew

nothing 'cept that I'd gone to America, and he said he knew where

I'd been there, but I wasn't there now, and it was thought I might

have come back to the old place. He seemed like a decent

mechanic, they say; but he said it wasn't for himself he wanted to

know. He may have been a lawyer's clerk for aught I can

tell—they can look like anything when they are going after people.

There was always some talk about a second cousin of my father's who

went to India, and was believed to have made money. But there,

if there's property looking for me, it's just like my luck to have

missed it.'

'Perhaps it is some old friend wanting some help or kindness

from you,' suggested Miss Russell.

'Then they haven't missed much, for I'm sure I can't do more

than for myself, unless it was just in the way of going to see 'em

and talking over things,' Mrs. Stone answered. And nobody

wouldn't think that much good, I reckon.'

'Oh, but they might,' responded Miss Russell.

'Well, I don't know, but I'll go over and ask about the rooms

at once,' said Mrs. Stone.

The result of which was that Miss Russell was invited over to

survey them, and was then directed to negotiate with a friendly

chatty old solicitor who transacted a profitable business in two

cupboards at the City end of Crosier Street, and who informed her

that he was empowered to give her every information and to consider

all her wishes, since Mr. Halliwell was too infirm to transact

business or to see strangers—the most definite information that Miss

Russell received about her future landlord and housemate lying in

the lawyer's remark.

'The fact is, you will have the place really all to yourself,

for Mr. Halliwell is just as if he was not there.'

Miss Russell took the apartments. The rent was not

exorbitant. She was to have six rooms entirely for her own

use, with liberty to introduce a servant-girl into the lower regions

for kitchen-work. The front parlour, looking upon Hallowgate

Square, she planned as a house-keeping room—the living apartment of

Mrs. Stone, who, with the servant-girl, would sleep in the third

parlour, while she herself would use the second one as a

dining-room. This parlour looked out upon a patch of green

which had been the burial-ground of a church long since destroyed.

There had been no funerals there for many years, and almost the only

trace of its former use was a high altar-like tomb, covered with

half-effaced tracery, most of the other graves being wholly

overgrown with ivy or flattened into the turf.

The three rooms on the first floor Miss Russell apportioned

as drawing-room, sleeping apartment, and spare bedroom.

As she had brought no actual furniture with her from America,

she remained at the Rood Hotel while she made her arrangements.

And she and Tibbie spent many an hour in planning, and discussing,

and shopping. Jane Russell was not shut out of the

conclave—she shut herself out with the observation—

'I cannot think how you can waste your time and energy over

such things. A furnishing upholsterer would do it better in a

single day. It is his business. Of course one likes to

buy some things for one's self. I have bought a good deal of

china and knick-knackery; but Sarah could do that afterwards as time

went on. I could advise her on those matters. I saw a

lovely pair of red-and-black dragons the other day. I was very

much inclined to treat myself with them; and Sarah might do so

without any scruple, as she has nothing of that sort already.

But how you two women can waste days over common carpets, and beds,

and chairs I cannot understand.'

'It's all Cousin Sarah; it isn't I,' Tibbie would say,

mischievously. 'I go with her just to keep her in countenance.

In the shops I am popularly supposed to be the bridegroom's grim

maiden sister, sent out with the betrothed to keep an eye on the

purse, and to whisper hard facts about moth and mildew.'

And so room by room was gradually furnished. The brown

housekeeping-room was spread with a blue drugget—with a

blue-and-brown checked table-cover, and blue-and-brown cushions in

the great wooden rocking-chair. There was a nettle-geranium

put in each window. And the brown walls were brightened with

four or five chromo-lithographs, after Birket Foster—sweet sunny

scenes, with happy children clambering cliffs or gathering flowers.

And over the cuckoo-clock on the mantel-piece hung a scroll,

'Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with all thy might.'

The dining-room was rosy, so that on the coldest day the

greenery of the little churchyard would never make it chill.

There was a flush of rose on the wall-paper, a deeper one on the

carpet; the chairs were covered in rose-coloured morocco; a

richly-flowered Dresden vase stood on the mantel, a great pink bowl

on the window-sill; the table china was in delicate pink and

cerulean blue. There were two oil-paintings, which Sarah

bought at some of the minor galleries. One was of a rocky

coast, a rough sea going down, and the first rays of dawn falling on

a rude little church by the sea; the other was of a sunset in the

heart of a dense pine-wood. Sarah had a wood-carving set into

the old oak mantel. It was 'the grace' which she always used,

she explained to Tibbie, and was simply, 'Whether we eat or drink,

or whatsoever we do, may we do it all to the glory of God.'

The little drawing-room was green-and-grey. Sarah had

some little bits of old stained glass, which had hung in her own old

home, with which she decorated the windows, so that the pale London

light came in brightened. Nor was the greyness and greenness

suffered to become chill. There was a kind of sunlight

imported into the room which made their background only as

refreshing as a leafy nook in midsummer. There was not one

'drawing-room chair' in the apartment. There were easy-chairs,

and prie-dieus, and lounging-chairs, and witching little low chairs,

and a sofa, and an ottoman, and lots of stools. In fact, Sarah

announced that it was never to be called the 'drawing-room,' but

always the 'parlour.' She could not find out a meaning for

'drawing-room,' she said; but 'parlour' might be taken as derived

from the Latin par, 'like,' or 'equals,' or, nearer still,

from the French parler, to 'speak,' which she suspected was

really a branch from the same root.

The books were to be kept in this room. There was a

large bookcase on one side, and a little bookcase above a

writing-table in a corner. The covers of Sarah Russell's books

fell into a kind of arrangement like an Indian-work pattern.

Then there was a cabinet, with a few pieces of china in it, but

generally filled with all sorts of queer, quaint things—shells, old

fans, scraps of pictures, and such pretty little trivialities as are

often bestowed by affection that can find little other voice.

'I've had a great many things of this kind at different

times,' said Tibbie, pondering; 'but I've lost some, and others have

got spoiled, and I've forgotten about the rest.'

As for the pictures, it is no use attempting to describe

them. There were little watercolour sketches of Sarah's

own—pictures of places not especially beautiful in themselves, but

sacred to her from some association of incident or idea; portraits

of all sorts of people—poets, preachers, workers of all kinds, many

of them in compound frames, grouped by a law of harmony which was

not always apparent at a first glance. Among the engravings

were Holman Hunt's 'Light of the World,' and Rosa Bonheur's 'Horse

Fair,' and the wonderful etching, 'Death as the Friend.' And

there was one exquisite picture in water-colours, hanging just where

it was on a level with the eyes of whoever sat in the wide low

chair, beside which Sarah's dainty little round-waggon was placed,

with her paper-cutter and pencil, and a blank book, and a work-case.

This picture was a 'seascape'—a green headland, where the dead had

been buried close beside the waves whereon they had doubtless mostly

spent much of their lives. On one of the graves sat a woman,

gazing out over the grey-green sea towards a calm but yellow and

tearful sunset. And in the frame was fixed a little plate,

bearing the simple words, 'I am the resurrection and the life.'

But if there was one room over which Sarah Russell pondered

most lovingly and lingeringly, it was the spare bedroom Jane could

not understand why she had at all—saying 'she had no relations

likely to stay with her; and as she was come to what was really a

strange place to her, she was little likely to have "strangers"

staying with her—a very good thing, too, for visitors in the house

only put one out of all one's own ways.'

But Sarah only said something about 'entertaining strangers,'

and thereby 'entertaining angels unawares,' on which Tibbie made the

characteristic observation, 'That no doubt Sarah might; but if it

was herself, the strangers would come without the angels.'

To which Sarah rejoined, 'You mean you might not recognise

them: perhaps not; but give the angels a chance of recognising you.'

There was something a little pathetic in the sight of the

gentle little woman, in her loneliness, preparing hospitality whose

secrets were so utterly hidden. For this chamber she chose a

soft carpet, coloured in two greys, with dashes of rose-red; and the

bed was curtained and the chairs cushioned in the same hues, only

with more rose-red in the tender greys. A little

black-and-gold vase was set upon the table in readiness for flowers,

and a writing-case, with pens, ink, paper, and postage-stamps, was

put beside it. On a little side-table there was placed a

Bible, red-leaved, and leather-bound, which looked as if it had been

bought a long time, and even used, but not with a regular and

constant use. Tibbie peeped into it, having a strange

curiosity about its inscription. But she found only three

initials—initials that she did not know and a date some years back.

Sarah herself illuminated the scroll that she placed over the

mantel. She could not find the text she wanted in any shop,

and she would not give an order for it, as she did for one or two

others, but did it herself; and Tibbie declared that 'there was more

in its execution than in that of the others,' though she frankly

admitted that 'it was technically not nearly so good.' The

words were taken from Isaiah—

'The Lord shall give thee rest from thy sorrow and from thy

fear, and from the hard bondage wherein thou wast made to serve.'

She lingered long in her choice of pictures for this chamber.

'She should often add another,' she said. For the present she

put in engravings from Millais' 'Order of Release,' Scheffer's

'Monica and Augustine,' Reynolds's 'Nelly O'Brien,' seated in her

sweet bright innocence in the sunshine under the trees; Harvey's

'Castaway,' with the ship just in sight on the horizon; and Dobson's

'Good Shepherd.'

And still, when all was done, she would go back and back to

that room, adding here a touch and there a touch.

But at last the servant-girl was hired, and the final remnant

of baggage was carried over from the Rood Hotel. Tibbie came

to share her cousin's first evening in her new home. Jane was

also invited, and Jane promised to come, but the day proved cold and

foggy, and instead of herself there came an excuse.

Tibbie was unusually grave and quiet, at first with a

slightly preoccupied air, which Sarah had often noticed in her, when

they had been going about the house arranging and planning.

But presently she shook it off.

'Jane is rather shocked at you, Sarah,' she observed.

'She thinks, as you have saved so much from your income during many

past years, you might have laid out the surplus in ways less selfish

than in such careful furnishing of your own house.'

'Why, Jane has a very handsome house of her own,' said Sarah,

astonished.

'Yes, but she says she inherited that from our aunt and her

godmother. You know she got all her fortune, and that is how

Jane is richer than me. She says she thinks you ought to have

seen a leaning to sit loosely to the things of time, and to have

gladly taken the opportunity not to be cumbered with the cares of

this world. I told her to mind her own business.'

'Nay, Tibbie,' said Sarah, expostulating, 'but it is her own

business. We are all of us each other's business; only it is a

part of that business to take care how we judge each other, and also

to try to set each other's judgments right, and to preserve each

other's charity. I must try to make Jane see what I mean in a

different light.'

'In her disapproval of you Jane actually got so far as to

approve of me,' Tibbie went on. "Even you," she said, "feel

that there is a better way of spending your time and money in this

world of sin and sorrow." And I said, "Well, I wish I didn't.

I wish I could find it in my heart to be like Sarah."'

'I almost think Jane is confining the word Charity to one,

and that not its highest meaning. Charity is Love, and not

almsgiving,' said Sarah. Love will endure for ever; its form

of almsgiving will always vary, and in its present form will pass

away. As Love grows almsgiving will decrease. Almsgiving

is the crutch for a lame world. Love is Life. If no

parents deserted their children there need be no foundling homes.

If we were all good and wise enough to care for the sick, within our

gates or at them, there need be no hospitals. If children did

their duty to their parents and guardians there need be no

almshouses. Do not think I am undervaluing "almsgiving."

It is an angelic attribute—the gift of making amends for others'

negligence, and undoing others' blunders, of warming where others

have chilled. But we must begin at the right end, by first

being watchful and careful and warm in our own lives. I shall

only "give away" but a very little less for what I have spent on my

pretty home, Tibbie, and it will enable me to be personally more

helpful and loving. It may suggest an ideal to somebody else,

out of which a life and a home may grow, from which more shall be

"given" than I could ever give.'

'And you are not afraid of being too like the world,' said

Tibbie. Most pious people are. And they are very like, I

must admit—too often like worldlings spoiled, like Indians dressed

in fashionable garments, with just a few feathers and glass beads

stuck about to proclaim their nationality.'

Sarah smiled a little sadly. 'We have not to think

about other people in that way,' she said. 'I think we may

make an effort to agree with them, but not to differ, though often

we cannot help it, and must differ. Everything good and

beautiful in this world, wherever and whatever it be, is nearer God

than its reverse. But there is hope in everything: we know its

present but dare not decide upon its future. Out of chaos rose

the beauties of creation; the wailing child grows into the guiding

genius; out of discord harmony is evolved. We know, too, that

every good and beautiful thing has its pernicious and perverted

imitation, its shadow as it were, resembling it only as the

distorted shadow of a man, thrown behind him on the earth, resembles

his real figure upright in the sunlight. Arts, which have it

in them to elevate and purify, have it also in them to debase and

defile. Even virtues—household virtues, for instance—may lose

all that is virtuous in them when, as often happens, the thing

typified is lost in the type, and the feast and the furniture and

the finery are themselves substituted for the "love" which alone

gives them any value or meaning. The analogy runs through

everything, and even into the highest mysteries: there is the New

Jerusalem, the pure "bride" of the Revelation; and there is Babylon,

the "harlot-bride," doomed to destruction. There is Christ,

and there is Antichrist.'

Tibbie glanced up at her suddenly, and seemed just going to say

something, when Mrs. Stone knocked at the door with a little sudden

imperativeness in all the respectful timidity of the knock. Sarah

bade her 'Come in;' and she entered, mysterious, on tiptoe.

'Ain't this awful?' she said, enigmatically. 'I never will forgive

them Rood Hotel people for not telling us afore; but letting you do

up the place as innocent as possible. I thought there was something

in the significant grin they always gave. It seemed to me queer that

you nor I shouldn't have seen the old gentleman up stairs, and yet

it might be natural enough in one old and infirm. But what do you

think, Miss Russell, ma'am? That housekeeping body, that has been

here ten years, hasn't ever seen him either!'

'Oh, how can that be?' asked Sarah. 'She waits on him.'

'So she do,' agreed Mrs. Stone; 'but there he is among them five or

six shut-up rooms at the top of the house, and there's two of them

and a great big light closet, that all communicate with each other,

and the two rooms have each a door on to the staircase. And when the

housekeeper takes up his meals she rings a little bell on the

landing, and when she goes into the room he is away into the other;

and when he's done he rings, and by the time she gets up there he's

away again. He leaves bits o' paper along with his plate and glass,

telling her what to buy, and when she can clean each room, which she

does turn about; but he must clean out the big cupboard himself,

for it's always locked, and she never gets in, and a pretty pig-stye

I'll engage it is. And she leaves his bills for him, and he puts out

cheques to pay 'em. And to think you've had all the trouble of

putting down carpets and planning, just to take 'em up and go away

again!'

'But I don't suppose I shall go away,' said Sarah, thoughtfully. It

makes me sad to think of such a life; but my going away would not

alter it, and therefore could not comfort me. I am afraid you will

not care to remain, Mrs. Stone.'

'Well, it's just like it always is—something to upset me as soon as

I'm comfortable,' said Mrs. Stone, wiping her eyes.

'But it needn't upset you,' said Sarah. 'You will be able to get

another situation; and if you don't like to wait here till you do,

I must make you an allowance somewhere else for a few weeks.'

'No, ma'am, you shan't do that,' said Mrs. Stone, with some

briskness. 'It's as bad for you as for me, and I ain't going to put

upon your kindness. I'll serve you here till I get somewhere else,

at any rate; and may be if I rub on for a bit I shall get kind of

used to it, and be able to stop; for I'll never get another missis

like you. I know that, but it is hard!'

'How does the servant-girl take it?' asked Tibbie.

'Oh, miss, she says she don't mind, as she ain't got to sleep by

herself,' said Mrs. Stone, smiling dimly. 'But what purtection is

that, if one thinks deeper? We're as good as all by ourselves

together—four lone women.'

'I'm not in the least frightened—understand that, Mrs. Stone,' Sarah

said, vigorously. 'There is nothing to be frightened about.'

'Deary me, deary me!' wailed the attendant, shaking her head

drearily. 'To think folks can't be like other folks!'

'Doesn't that mean that you wish everybody was like yourself?' said

Tibbie. 'That Mr. Halliwell would not do what you cannot understand,

or that Miss Russell would be like you, so frightened that she would

instantly decamp?'

'You do put things so funny, miss,' said the good woman, retreating

to the door; 'but I wasn't thinking of mistress at all, but of the

queer, cracked gentleman.'

'I suppose there is no doubt this is true,' said Tibbie, when she was

gone. 'I don't think it was quite honourable or considerate that

this was not explained to you before, Cousin Sarah.'

'Neither do I,' Sarah admitted; 'but that only gives one hope that

nobody who was really honourable and considerate towards others

would be allowed to fall into such a shocking way of life as this

poor gentleman's.'

'I have seen this landlord of yours,' said Tibbie, 'years and years

ago. He was connected with a family whom I visited. I did not tell

you this—because—I did not care to speak about his relatives—whom—I

knew. He was a tall handsome man, rather domineering. I think he was

a widower, with one daughter. I never knew what became of the

daughter. I knew there had been something very peculiar about him

for many years, but I thought it was nothing more than a withdrawal

from general society, something like my own. If I had thought it was

anything like this, believe me, I would have told you, cousin.'

'I am sure you would,' said Sarah. 'Poor

man, poor man! it is so dreadful!'

'There are many things that I can understand less,' said Tibbie,

rather curtly.

Mrs. Stone had a very eerie face when she brought her mistress's

bedroom candle that night.

'I hope it will be all right, ma'am,' she said, vaguely. 'And good

night, ma'am. I ain't frightened, ma'am. Only queer. It is worse

than being in a house with a ghost, ma'am!'

CHAPTER VI.

|

A fire just dying in the gloom;

Earth haunted all with dreams;

.

.

.

.

.

And near me, in the sinking night,

More thoughts than move in me.

Forgiving wrong and loving right,

And waiting till—I see.

GEORGE

MACDONALD. |

DAY after day

passed on, and Mrs. Stone apparently grew accustomed to the unseen

presence in the house, and would comment on the dinners that went

upstairs, and the directions which came down.

'If you make up your mind to put up with anything, it's wonderful

how little there is to put up with; and I always lock my door at

nights,' she would say. 'Not but what I do get the creeps at times

but then days have been when I read silly stories just to get the

creeps, so why should I mind taking' 'em natural?'

Sometimes, as Miss Russell sat in her little drawing-room,

she would hear a slow, heavy step totter across the room overhead,

and she would drop her work or her book for a moment, to yearn over

the worn, proud life that was going down so darkly to its close.

The mystery about it was not lifted. Mrs. Stone reported that

the housekeeper said that there were two or three attics upstairs

shut up, full of furniture that 'had been just bundled into them

anyhow.' Sarah respected her cousin Tibbie's statement that

she knew really nothing of this Mr. Halliwell or his history, and

for reasons of her own did not wish to speak of the people with whom

she had met him. Sometimes, when Tibbie was visiting Sarah,

that heavy step would pass overhead, and then the two would pause in

their talk, and look up at each other, and Tibbie would answer

Sarah's sigh by a long, in-drawn breath.

Christmas was drawing near—very near.

'Christmas is a mistake,' was Tibbie observation; 'I mean as

far as I am concerned. From June to December it lies on my

mind like a nightmare, and from December to June it takes all my

strength to throw off the shadow of it. My one care is "to get

it over;" and between you and me, cousin, I believe the very same

feeling lies at the root of more than half of the frantic festivity

of the season. It is all very well when one is young, and can

enjoy turkey and plum-pudding, and see a real meaning in the

mistletoe. But now I'd rather trust mutton-chops and semolina,

and might stand under the mistletoe for a month quite fearlessly.'

'But are not these only the little fleeting brightnesses with

which merry young life clothes the reality?' said Sarah. 'Just

as children put flowers before their parents' portraits on their

birthdays. Is not the reality the star, and the angels' song,

and the dear lowly birth of Him who revealed to us the Sonship of

Humanity and the Fatherhood of God?'

'But then it's all nothing to me,' said Tibbie. 'It is

a very pretty story, eighteen hundred years old, and it is all quite

true, and all that, you know. Only there's no star to guide

me, and there's no peace in my world, and no goodwill in my life;

and it is my special season for hobgoblins and blue devils, don't

you know? So, just to get rid of the time, I put on an old

gown and go down to our rooms in Whitechapel, and stick up a few

texts that nobody ever reads, and buy some holly and laurel (not

mistletoe, you know—'tisnt proper; kissing ain't respectable if

you're poor). And I stand there all day, handing out

plum-puddings, and ladling broth, and writing coal-tickets.

I'm quite invaluable, don't you understand, for all the other

philanthropists want to be away enjoying themselves, and they say

they can do so with a quiet conscience if I'm there, because I'm so

efficient, i.e. so crabbed, and expert in the

"move-on-or-I'll-take-you-up" style. And after one's stood so

for six or seven hours one is ready enough to rush home, and drop

upon one's bed and lose consciousness.'

'Don't you even look in upon Jane?' Sarah asked.

'No, indeed,' 'Tibbie answered, energetically. 'At

these seasons Jane has such a keen consciousness of the reality of

blessings which she undervalued while she had them, that she nearly

drives me crazy. If I die first (as very likely I shall,

though Jane fancies herself so frail, and though I believe when I

was made I was meant to live to be ninety), I daresay Jane will

canonise me, especially on the return of these pathetic festivities.

I shall be "her darling, sainted sister Tibbie," along with "her

dear sainted parents," with whom she used to be so terribly fretful.

She drives me to Gehenna in my lifetime while she has any power over

me, but when I shall be taken out of her reach she'll clap a palm

into my hand and a crown upon my head. I may have given no

sign of any change, but Jane will fall back on her mysterious faith

in last moments

|

Between the saddle and the ground

Mercy was sought and mercy found. |

Only, as it wouldn't be edifying to have a family connection

barely saved, she'll just touch me up into a shining saint.'

Sarah looked sadly into Tibbie's face during her scornful

tirade. 'If it is all as you say,' she pleaded, 'ought you not

to be sorry for Jane rather than angry? Tibbie, might you not

catch more of the real Christmas blessing if you would consider what

is now generally admitted to be a more correct version of the

angelic chorus: "Peace on earth to men of good will?" '

'Oh, but Jane would not thank me for any consideration for

her that came through what she would call "wresting the Scriptures,"

' said Tibbie, flippantly. She believes in the direct

inspiration of the English version. She wants to know nothing

of possible renderings of the Hebrew and Greek original. She

does not believe in an infallible Church—Jane is a very sound

Protestant—but she does believe in whole generations of infallible

translators and copyists. If there is at the present time a

missionary translating the gospel into Fijian, she firmly believes

that he is inspired to give every word its exact and complete

meaning, regardless of the capacities of the Fijian dictionary.'

'I only mentioned that variation as a help for you,' said

Sarah. 'These variations do not really signify. Whoever

accepts the Bible as a revelation from God cannot help seeing love

and good-will written in capital letters across the whole of it,

whatever details may remain for the eyes of particular races or

individuals; and about details I believe there will be differences

for ever.'

'That's a comfort for me, anyhow,' said Tibbie, recklessly.

'I like to be different. I am hĕtĕrŏs

by nature.'

'There is no advantage or originality in being hĕtĕrŏs—"dissimilar"

merely,' Sarah observed, rather decidedly. 'A crooked tree is

dissimilar, as far as that goes. But a pine is dissimilar from

nettles, because it belongs to a higher order. The first point

a dissimilar person should be careful to ascertain is, is he unlike

others because he is above them, or below? That question of

above or below explains nearly all the paradoxes of the world.

One man does not care for the luxuries and refinements of life,

because they are no pleasure to him—he is below them. Another

gives them up or does not grasp them, because he has higher aims,

and has in his own soul all that they only typify—he is above them.

Some people bear the death of friends easily, because they live so

deep in the mere animal life; others bear it bravely, because they

have such clear faith and such an intimate sense of the communion of

saints. That is how extremes meet. That is how all life

appeals to a judgment that can reach the spirit below the form.

As for you, Tibbie, I cannot help saying to you what I have said

quite lately to poor Mrs. Stone, that you seem to live your life

entirely at other people's mercy—that you drink from soiled and

broken cups instead of carrying your own vessel to the fountain, and

yet complain that you are nauseated. Figuratively you consult

oracles which you feel are false, and then complain that you are

bewildered at their response, as if a Christian had gone to Delphi,

and then marvelled that the answer came in the name of Apollo

instead of Jesus. Pardon me, Tibbie, I have no right to speak

to you thus, except the right you give me yourself by speaking as

you do.'

'Well, you are quite right,' Tibbie replied. What you

say is true. My life has fallen into the power of another.

I am what I am, because one woman willed it. Not Jane. I

should not like you to think it was she. She has really never

touched my life to hinder it—except by not touching it at all.'

'Then forgive me for what I am about to say, Tibbie,' said

Sarah, and remember that I say it fearlessly, knowing nothing of the

facts of the story. If this woman, whoever she be, has injured

you and your life, as you say, be sure you have injured hers as

much.'

('I wish I could think so,' said Tibbie, in bitter

parenthesis.)

'You have injured her by allowing her to injure you.

You are like two people who have fought a duel, stabbed each other,

and fallen dead together. If you had had on your armour —the

armour of God—you would have turned aside her weapon, saved her from

the guilt of spiritual bloodshed, and gained a dominion over her for

her good that should never have been taken away.'

'Well, it's all over now,' Tibbie observed. The die is

cast, and it is too late for another throw. Quite too late,

Sarah. The only chance of my recovery is gone for ever from

me. The story is done.'

Sarah looked up at her, with a strong light in her quiet

eyes. 'Do you think anything is ever done?' she asked.

'I don't. I believe things are always going on, and that our

hands are always in them.'

'We have nothing to do with the next world,' said Tibbie.

'Do you say so?' asked Sarah. 'The Bible says

otherwise. Dives was made more miserable by the remembrance of

his brothers, and the angels are made happier by the repentance of a

sinner. Much of the misery of Gehenna, and much of the bliss

of glory, will be darkness or light reflected from this world.'

Tibbie shook her head. 'How could glorified spirits be

happy if they could see the sin and misery of their dear ones left

behind?' she asked.

'They could bear it, because they would be growing more and

more into the secrets of the Father of Faith, Hope, and Love,' Sarah

answered. 'Why, Tibbie, the more we know the more we can

always bear. The missionary, the philanthropist, the teacher,

the physician can bear all sorts of sad sights, not because they

feel less than others, but far more. We can endure anything

when we are workers with God, and not fighters against Him, because

when we are on His side we have as much of His strength as we need,

and as much of His knowledge as we can support.'

' "The angel's hopeful side," ' said Tibbie, quoting herself.

'And I mean to come to Whitechapel with you on Christmas

Day,' observed Sarah, changing the subject. 'I shall send my

servant home to her parents, and Mrs. Stone and I will come and help

you with the puddings and the broth, and then I shall go on and

spend the evening with Jane. Don't think I'm going to omit

festive preparation in this house by the arrangement. I would

not lose the mincing and stoning for anything. On Christmas

Eve the kitchen shall be full of roasting and boiling, and sweet

herbs and candied-peel. We must have nice things ready to give

anybody who comes in our way between Christmas and Twelve Night.

The mere eating is the least part of it. I daresay "waits"

[Ed.―archaic: 'itinerant nocturnal

musicians'] come to a wide, pleasant square like this.'

'Well, Christmas is just nothing to me,' said Tibbie, with

the air of a person carelessly astonished at a mood beyond

comprehension. 'Why, it is not the Saviour's real birthday.'

'Is it not?' asked Sarah, smiling. 'I know it is not

Jesus' birthday. That, like Moses' grave and many other things

we should like to know about, has been concealed from us for wisest

reasons. But any given season of household love widened to

hospitality and regularly recurring, whether it be the Jewish

"Sabbath of the land," once in seven years, or the wider "Year of

Jubilee," twice in a century, is the type and foretaste of the

revelation of that Christ of Love and Resurrection power towards

whom the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together.

We need not think that our dainties, and our gifts, and our good

wishes must be too puerile for such a connection. God Himself,

by His prophet Zechariah, was pleased to depict the beauty of His

kingdom by such typical touches as that there shall be upon the

bells of the horses "holiness unto the Lord," and every pot in

Jerusalem and Judea shall be holiness unto the Lord of Hosts.'

And then the cousins parted, after arranging the time and

place of their meeting on Christmas morning, for it only wanted a

day or two to the festival, and they were not likely to meet again

before it.

Christmas Eve came. Miss Russell and Mrs. Stone and the

servant made a busy household day of it, as women always can.

Miss Russell heard Mrs. Stone draw long, long sighs more than once,

and her eyes looked a little red. The little family always

joined in household prayer now—very simple prayer—that God would

direct and control all their ways, and pour down His love upon their

lives, and adopt them as His children, according to the revelation

of His Son, the Elder Brother, Christ Jesus. Miss Russell

always made a long pause before her solemn 'Amen,' wherein each

heart could send up its special petition. But this evening

Mrs. Stone lingered as she put the Bible before her mistress, and

whispered―

'Would you mind asking out loud, ma'am, that God will keep an

eye on those that we've lost sight of? I don't know how it is,

ma'am, but staying in the house with that poor gentleman upstairs,

and turning over in my mind how he can be so darkened and shut up

like has given me a terrible hankering after my poor man. I

expect we're parted for ever and ever; but I'll wish him well, if I

ain't to have another chance to do more.'

And so, instead of the hush, Sarah prayed aloud the petition

with which she had always filled her own share of it—'that the Lord

of life and love would remember those whom men forget, and gather in

those whom men cast out, and fill the empty hearts, and re-build

earth's ruined homes in heaven.'

'Thank you with all my heart, ma'am,' Mrs. Stone whispered as

she said 'Good-night.' You said just what I felt and could not

say—just exactly as if you knew what it was. And I'm kind of

sure of an answer, whether I ever know it or not. That's what

mother used to say: "Ask and receive," she said; "one received in

asking." '

Miss Russell went away to her own room. She thought to

herself that she would sit up though the midnight bells rang in the

Day of joy. She was not afraid of a lonely Christmas Eve—the

past, the dear parents who had made the happy home of her girlhood,

the pleasant friends who had gone before, lowly old women, young

girls, brave, frank lads, were all as much alive to her heart as

ever. She did not shrink from any silence in her life which

gave it a chance of catching its own angelic chorus. Nay,

rather she sometimes thought she must beware lest the past and the

future should join hands to shut out the present—must remember that

the lives still in the shade of the flesh must be very diligent and

full if they are to keep pace with the dear ones who, lifted into

the sunshine, are swiftly passing from glory unto glory.

She did not sit and think only of death-beds and 'last

words.' The darkness of the dying flesh may eclipse the light

of the passing soul—was there not gloom over all when One died on

Calvary?—and 'Eloi, Eloi, Lama Sabachthani!' was wrung from Him who

had overcome the world? She thought of sunny summer walks—of

mountain clambers, of merry winter nights. She laughed—yes,

once she laughed so that she heard herself—at the remembrance of an

old merry saying of one who had been for years in everlasting joy.

Some death-beds she did ponder over, where strength had been made

perfect in weakness, and the soul had visibly burned brighter in the

breaking of its lantern. Some last words she did dwell on,

flowers from Paradise which those just entering had thrown back upon

the watchers outside.

There were other memories too—stories, one story—which had

been bound up with her own life, and to which 'Finis' was not

written, but the end was torn away. The 'ends of the earth'

are so much farther off than the New Jerusalem, and the absent in

the flesh may be so drearily separated. It takes a really

higher faith to trust God for this world than for the next, because

this is a faith which must be all fact, without any dangerous

possibility of a mixture of fancy. Even Sarah Russell had

often to remind herself that

|

God is not only kind through us

He blesses, though we are not there;

For are not stranger skies as blue,

And are not stranger flowers as fair? |

But to one truth she clung—and it kept her brave and bright—that we

only learn how to love from God Himself, and that our truest love is

barely a faint type of His!

Sarah Russell did not mean to sit long dreaming; she was a

woman of regular and orderly ways. But just as the most

methodical of us sit longer than we know, when dear friends meet and

heart histories are revealed, so the stream of her pleasant and

tender and sacred reverie swept Time swiftly past unheeded. The

bells began to ring—rang—she did not even notice when they ceased.

The joy-bells of her own heart's love had been ringing in harmony

with them, and they still went on. It needed a discord to

rouse her. The discord came.

Only a slow shuffling step on the stair—a step that she did

not know—a step that seemed unused to stairs, and fell upon them

with an uncertain totter.

Only for less than a moment Sarah Russell's heart stood

still. Then she said to herself

'It is Mr. Halliwell!'

She sat motionless. Had she believed that it was a

disembodied soul returned to haunt the platform of its history she

would not have felt such awe and dread.

For was not this really 'a ghost?'—an unhappy soul, torn from

its place and its work, beating out its life in a horologe whose

signs and sounds were no longer displayed and struck in the visible

world? We need not go out of the flesh to be 'ghosts' in the

modern and ghastly meaning of something 'unknowing and unknown.'

She sat and listened. The step went down and down.

Then a door opened. She knew the sound; it was the

working-room door. A few minutes' pause, and it closed, and

another opened. It was the dining-room door this time.

Another pause, and it too was shut. With that strange mingling

of the practical which always dashes our most mysterious moods,

Sarah congratulated herself that Mrs. Stone locked her door, and

hoped that the good woman and the servant-girl were both lost in

slumber.

The step slowly ascended the stairs. Sarah remembered

that both the drawing-room door and that of the spare bedroom stood

open. The unknown visitor went into the drawing-room, and

through the partition which divided it from her chamber she heard

the slow step go about, pausing before the portraits of strange

faces; puzzling out the engravings whose originals had grown famous

since he had been dead in life. Then he came out and went into

the other room, and stayed there long, and long, and long. She

wondered if he noticed the text above the mantel, and what he

thought of 'Nelly O'Brien,' and 'Monica and Augustine,' and 'The

Castaway.'

The step came out again, and lingered for a moment outside

her door, but no hand was laid upon it. Sarah debated within

herself whether she should not go out and face the awful hermit and

break the black magic of his silence and solitude. But she

thought 'No.' For none can be led further than they will go:

no light will penetrate more than the curtain is withdrawn.

The spells of the soul are not broken in the breaking of their sign.

God's sun dawns gently, and makes us long for light before we have

it. It was enough for this time that he had wanted to look

upon a home, and that her doors had been open.

The step went up-stairs.

Sarah Russell had a picture of Mr. Halliwell in her mind. We

all of us have such pictures of those we have never seen.

Sometimes they prove true—sometimes false. And sometimes,

after years have past, we find a truth in them which escaped the

first sight of what we call 'reality.' People talk a great

deal about the mysteries of first impressions; but if we look

closely into our own minds we shall find that these very impressions

are secondary—that something else went before, and that our 'first

impressions' only impress us by their contrast or harmony with this

something. Our minds are like mirrors, and there is an inner

eye which sees reflected upon them pictures of people and places

which the eyes of our flesh have never beheld. But the mirror

is more or less blurred, and the inner vision, like the outer, is

often so imperfect that it sees 'men as trees walking.'

Sarah Russell's mental picture of Mr. Halliwell, as he

returned to his solitary chamber, was of a tall old man, just a

little bent, with that sad, touching bowing of a figure that has

once been very erect. He had a long grizzled beard—and his

face was dark and hawk-like, with quick angry eyes—somehow like some

face she had seen somewhere. How did she put that likeness

into it? She did not even know whence it came.

She heard the slow foot go to and fro for a while in the room

overhead, and then, when all was at last quiet, she herself lay down

to sleep—her last waking thought set in the verse which had become

the refrain of her life—

|

If some poor wandering child of thine

Have spurned to-day the voice divine,

Now, Lord, thy gracious work begin;

Let him no more lie down in sin. |

CHAPTER VII.

|

She cries, 'Theses things confound me,

They settle on my brain:

The very air around me

Is universal pain.'—R. M. MILNES. |

THE room in which

Sarah, Tibbie, and Mrs. Stone met on Christmas morning presented a

sight not to be easily forgotten.

Seated on forms, or forlornly hanging about against the

walls, were rows of people, who seemed all of one dreary middle age,

for the youth among them had no brightness and the age no

venerableness. They looked all soddened and beaten-out, no

more resembling humanity as it comes from the hand of the Creator

than their hueless, slackened rags resembled the bright textures

which had once come from the loom. Nothing is made so, however

much may be spoiled so.

They were not interested in the sight of the strangers, as

Sarah would have been interested with new faces in any sphere of

hers. They did not expect anything but their soup and pudding,

and those they could take from anybody. They did not know to

care for the hand of the giver as well as the gift. For a

moment Sarah's heart sank, and a swift wonder shot across her mind

whether those who put themselves to contend with a wretchedness like

this must not always be hard and hopeless, like poor Tibbie:

hopeless in endurance, and hard to endure.

But as the two cousins and Mrs. Stone ranged themselves

behind the long table Sarah's eye fell upon two women, close at her

right hand, who were eagerly looking at something they held between

them. It seemed like a little book or picture, and they smiled

and shook their heads over it; and then as the elder of the two

thrust it into her bosom her eyes met Sarah's.

'May I see it too?' said Sarah, yielding to a sudden impulse.

'Shure, 'tain't anything to look at, 'cept for those as knew

him,' the woman answered, in a strong brogue, holding out a little

dim glass photograph. 'It's only my poor bhoy, that's been in

glory just two months since yesterday. I brought it round to

show my sister, 'cause she daren't come to our place, because she's

married on an O'Flanagan, and my husband's an O'Reilly, and they

nivir spake to each other 'ceps with shillelaghs. That's my

poor bhoy, and that's me, ma'am, for he would be taken holding my

hand. He knew he were a-going, ma'am, and he said I'd like to

look at us so when he were gone. A real fine-looking gossoon

he was—ask anyone down our court; and he died in his chair, being as

all the while he was ill; he was too spirity to lie down, only just

outside the bed. That don't look like me, ma'am, because I had

on Mrs. O'Brien's bonnet with the red flowers, an' in a gineral way

I don't wear bonnets myself; and it made me feel quare, as the pig

said when he put his head through the stocks. A good dutiful

bhoy he was always, ma'am, and thought there was nobody like his

mother—little reason he had! He used to say, "If the room was

full of people, and not mother, I'd call meself lanesome." I'm

paying all I can to get him out o' purgatory, but I always think of

him as in glory, for I'm sartain shure he's at the glory-end, and

the Holy Vargin wouldn't let me be desaved. Isn't it a pratty

picter, ma'am?'

'It is indeed,' said Sarah, and it must be very valuable to

you. You must take great care of it, because glass is apt to

break.'

'Marcy me!' cried Mrs. O'Reilly; 'the first thing, whinever

there's a fight on, I catch it down from the wall and sit on't.

I says to my Mike now, "Ye must look after yeself; I've got

something else to look arter. I can't even reach ye a broom if

ye're out o' hand's length." Young Mike didn't fight much.

He was one of those that are marked to be took, and minded his

church duties, and I nivir saw his blood up 'crept whin Miss

O'Flanagan insulted his mother.'

'Can't you persuade your husband to leave off fighting too?'

asked Sarah.

'Losh me, miss, it's just in the natur,' explained Mrs.

O'Brien. 'He means no harm. He gives and takes.'

'But should not he try to get it out of his nature?' said

Sarah.

'He ain't so quick up as he was,' Mrs. O'Brien admitted.

'He let that Jim O'Flanagan call him a mean word the other day,

because he minded how Jim helped our Mike home when he turned faint

in the street the day before he died. "I'll never forget a

kindness to my bhoy, Jem," says he; "so if ye're mane enough to

insult a man whose hands are tied, ye may, Jim." And says Jim,

"I'd do as much for you as I did for him, though you are an

O'Reilly; but never you come down our court." '

'That woman belongs to an awfully drinking, fighting lot,'

whispered Tibbie to Sarah, as they passed to and fro.

'Did you know the lad who died?' asked Sarah.

'Yes,' said Tibbie; 'he was a good-looking, delicate young

man, with a pleasant tongue. He came here hanging about on one

of our soup-days, but he wasn't one of our regular cases; and I

didn't notice he looked particularly ill, and I didn't give him

anything. He died two or three days after. The O'Reillys

and O'Flanagans will never be anything but O'Reillys and

O'Flanagans, not even if they cross the water, and rise in life and

mix in Yankee politics.'

'Never mind,' said Sarah, whose soul was once more light with

the lustre of that Sun which had not forgotten to shed its ray of

mother love, and neighbourly kindness, and elevating influence, even

down the foul court where pokers and brooms and pewter-pots flew

about in Irish faction-fights.

She turned brightly back to the dismal room and its forlorn

crowd. That Sun was shining on all that crowd, and in that

light she could bear to look at each, assured that not the dreariest

heart there was without some tender memory, or vague hope, or

clinging affection, the dimly perceived lower rung of that ladder of

Love which reaches to the throne of God. And, with that

consciousness of human affinity shining strong upon her face, many

of the deadened faces round seemed to grow responsive, so that the

moment faith rose to the realisation of the great human brotherhood

it changed to sight. Those who believe can see!

One by one, as the people came up, Sarah found some bright

word to say to each. Something about the baby, something about

the pudding, some question about who was to eat it at home.

Slow smiles broke stiffly on faces unaccustomed to that form of

muscular exercise. One or two, after they had walked away with

their prize, in their first hungry eagerness, turned back to drop a

curtsey and wish her a merry Christmas.'

'Its very good o' you to come here to-day, seeing after the

likes o' us,' said one woman, 'for the likes o' you will have plenty

o' people wanting you otherwheres.'

Sarah only smiled. Never mind! And it was true

too—there were some in heaven who, she was sure, would be glad to

see her there—and one or two somewhere in the world—and there would

be always somebody like these, who would be glad of her. 'The

poor ye have always with you'—the poor in heart or in life. No

fear of not being wanted!

Among the crowd came one middle-aged woman, whose decent

though threadbare garments and scrupulously clean face were so

obviously different from all the others, that Sarah felt her being

among them made her an object of special interest and pity.

'Is your card an order for a family dinner?' she asked.

'Yes, indeed, ma'am,' said the woman; 'it's for two families;

the ladies were so kind as to give it so. And indeed I'm most

thankful, for we're having a bad time.'

'Is your husband out of work?' Sarah enquired.

'He hurt his hand three weeks ago, and won't be able for his

trade for another week yet,' said the woman. 'And then our

lodger isn't paying anything, and we're most keeping him besides.'

'How is that?' Sarah asked. 'Well, he came to us about

three months ago,' said the woman, and he was ailing and poorly

then, and very bad in his mind, and he'd come from America; and I'd

had brothers in San Francisco, and it made me take to him. He

paid us regular then. But about six weeks ago he took a

stroke, and he went on paying a little; but now he's had another,

and his money is all gone. He just run out as my husband hurt

his hand. Troubles always come together.'

'Could you not get him into some infirmary?' Sarah asked.

'No, ma'am; I don't think there's any hospital takes in those

kind of cases, leastways only one, that has always more than it can

do. Of course there's the workhouse. My husband had

thought of that when the man was first took ill, but I said, "Wait a

bit; maybe he'd mend." When my husband met with his accident I

thought then he must go; but, when I spoke on't, my husband wouldn't

hear of it then. He gets kind o' low like, afraid of us having

to go into the House ourselves; and I thought it would be a burden

off his mind. But he took it contrary, as men do, and said it

would be the beginning o' folks going from our place to the House,

and that it wasn't the way to keep out of it to send others there;

so there he is yet. My little gal's minding' him—he don't want

much minding; he's just stock-still and nearly dumb now, however bad

he may be in his mind. The ladies knew what we were doing for

him, so they gave me tickets for two family dinners, and some jelly

and beef-tea was sent round for him.'

'Well, I must get your address from my cousin and call on

you,' said Sarah. 'I hope you will have a cheerful Christmas

dinner. Trust in God, and keep up your spirits, and all will

go well.'

'The children keep us a bit lively,' the woman answered

again; 'they go upstairs and sing in the man's room—he seems to like

it. Their father used to sing hymns with them, but just now he

turns all-over-like if they do it in the room with him; but when he

hears their voices from upstairs he often begins to hum the tune

with them. He don't notice himself, and I says nothing for if

I did he'd leave off, and say he was in no singing temper.'

'Good bye. A cheerful Christmas and a brighter new

year,' said Sarah, as the woman went away. So down in some

other dreary court there was hymn-singing, and 'entertainment of the

stranger!' Sarah caught herself repeating a verse she had read

somewhere—

|

We see the struggle, we hear the sigh

Of this sorrowful world of ours;

But in loving patience God sits on high,

Because He can see its flowers. |

'Eh, ma'am,' said Mrs. Stone, as she trudged off with Sarah,

in search of a cab to take them to Jane Russell's house. 'Eh,

ma'am, I can't forget that paralysed man! Fancy lying dumb and

stiff in a strange place, where one might be turned out to-morrow!

And bad in one's mind beside! It is to be hoped he hasn't got

to remember that he left people that would have had a right to look

after him! My husband's father died a paralytic, and I've

heard him say he shouldn't wonder he'd come to it himself; and I

used to think I should have a hard time of that sort with him, as

soon as he was through the hard times he gave me with his drinking

and ways. But that wasn't to be, if he was took sudden, as I

suppose he was. And if he wasn't, and his words come true,

he'll be like that poor creature yonder, only not with such good

people, most likely.'

Mrs. Stone was to dine with Jane's servant, while Miss Sarah

dined with the mistress. They found the gate locked, and the

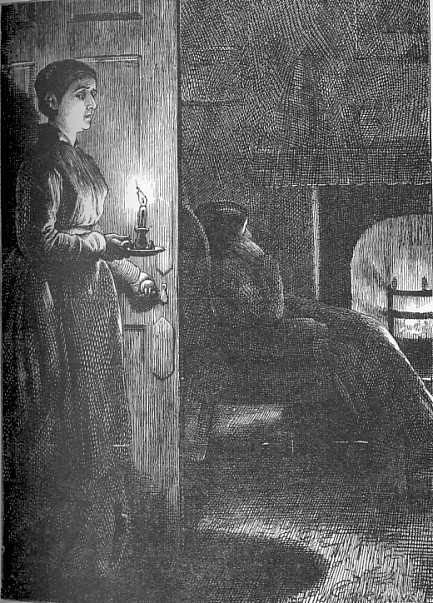

door bolted as usual. Jane was sitting in the drawing-room

before a huge fire, wearing a fur tippet instead of her usual light

knitted shawl; and she received Sarah with a tearful sympathy, that

was clearly quite thrown away on that bright and brisk little woman.

|

|

|

'IN THE DRAWING ROOM BEFORE A HUGE FIRE.' |

'I really could not stir out to church to-day,' she said.

'The weather is so bitter; and besides, I am so sensitive that the

anthem and hymns try me far too much. I had to leave the

church in the middle of the last Christmas service I attended.

I cannot bear to think of the time when I stood with my dear mother

singing "Hark, the herald angels." And there was one Christmas

too when another dear voice was raised beside me—such a fine tenor!

And now there's only me!'

'O but can't you hear them singing far more sweetly in the

Higher Home?' said Sarah. 'I don't think people can know half

the beauty of the dear old hymns until they can hear in them far-off

voices which others cannot hear.'

'But they sing a new song in heaven, and that is all we know

about it,' said Jane, adding, with quite unconscious humour, 'As for

the other voice—he goes to the Wesleyan chapel now, and he's quite

middle-aged—he was some years older than me—and very likely he does

not sing at all; middle-aged men seldom do. I've left it off

myself, though a woman of forty is not quite middle-aged, you know,

Sarah.'

'I think to join in congregational singing is as much a duty

as to join in congregational prayer,' said Sarah. 'If one

can't quite make one's voice harmonise at first, sing softly till it

does.'

'I had a sweet voice when I was a girl,' Jane observed.

'I think I lost it by fretting. Though, as I always say, women

like us, with even our little fortunes, do not lack offers to share

with us, yet among all my admirers I never really cared but for that

one, Sarah. I think the heart has but one love. All that

affair was a bitter blow to me. It withered my youth at its

core. It is a marvel to me that I am still young-looking and

cheerful on the outside.'

Sarah was silent. She did not want to be unsympathetic,

so she could not venture on words.

'He was very delicate-looking,' Jane went on. 'He had

no home, and nobody to care for him; and I used to fret to think how

lonely and neglected he must be. But it is a terrible

undertaking to marry a sickly man, Sarah. I was a hearty,

pretty girl then, as I daresay you remember me, and it would have

been a fearful sacrifice of my young life to tie it to an ailing,

frail husband. I was so sensible as to be able to consider the

whole bearings of the matter, so that my dear mother did not attempt

to urge me to any decision, but only to help my judgment by making

me well acquainted with the real facts of the case. I never

heard her express a decided opinion either way further than to say

that "she did not desire a child of hers to undertake anything

blindfold." I could see that such delicacy as his might

possibly soon slip into a valetudinarianism which would prevent our

going into the society that I was then calculated to adorn, and

condemn me to the slavery of a sick nurse. I saw, too, that it

might easily set him aside from his profession, and as he had no

private means, would throw us back on my own resources, which,

though sufficient to maintain my present position, would have kept

up but sordid married state. I saw, too, that he might very

probably die young, and leave me, just as before, only worn out,

impoverished, and blighted. How could I face such a prospect?

Now, how could I do it, Sarah? My mother said I was right to

allow myself to weigh all these contingencies, and having weighed

them, what could I do but give him up! I can assure you, it

was like tearing my heart out to do so. But I saw it was my

duty, and I never flinched from my duty yet.'

Jane covered her face with her handkerchief; it was quite

unnecessary, for there was only a very slight moisture about her

eyes, such as might come from the too near proximity of the blazing

fire.

'And if he had grown a confirmed invalid or died, I could

have borne it so much more easily! But after two or three

years he married somebody else, and he's a great, strong, healthy

man now, and must make fifteen hundred a-year at least. And

somehow I broke down from the day I gave him up, and now I'm the

wreck you see, and I might have had him to cherish me and care for

me.' And up went the handkerchief again!

Sarah did not know what to say. She could scarcely find

it in her heart to say that there is a cross in the way to every

crown, whether of human joy or spiritual triumph, but that often the

only crown revealed to our eyes, until we have fairly lifted the

cross, is a crown of thorns.

'Well, Jane,' she said gently, 'it would not have been right

for you to marry him, unless you loved him so much that you could

take joy in your sacrifice, even had its utmost penny been demanded

of you.'

'But I did love him,' said Jane, fretfully. 'I did love

him as much as ever woman loved man.'

Sarah sighed softly. Jane had doubtless loved him as

much as she could herself, and in our standard of human

possibilities, we can never rise higher than our own.

'It was only my high idea of duty,' said Jane. 'I am

made a martyr to my sense of right. I was right in my

inferences. The cruel thing is that I was allowed to be

mistaken in my facts. And here I am left in the full

realisation of my loss and loneliness! If I was like most

people, who have never really loved at all—like Tibbie, for

instance—I could be quite content!'

'Oh! does not love bring its own blessing with it?' pleaded

Sarah. 'Is there not comfort in the very longing it leaves

behind it? Besides love is never lost.' Alas!

Sarah felt that she was talking wide of the true mark in this case,

but she did not know what else to say.

Jane smiled supremely. 'Ah, it is sweet to fancy how

sweet it is to love !' she said; but the real thing is different,

and its loss is very real. But now, dinner is ready.'

It was a very sumptuous little repast—not a strictly

seasonable one, because Jane preferred pheasant to roast beef or

turkey, and could not endure plum-pudding, so supplemented the

mince-pies with chocolate, soufflé,

and tipsey cake. There was no Christmas decoration about the

rooms. Jane saw Sarah's eye go in search of it, and remarked,—

'I never have any of that nonsense. The vegetation

always brings in a sensation of raw cold and damp which sets my

nerves a-jar.'

There was something a little tart and ungracious in the

manner of the servant, which her mistress explained when she left

the room.

'She wanted to have her mother here to spend the day with

her. Of course I could not allow it. Her mother is a

charwoman, and no charwomen are very particular, and I could not

have her about on the very day when all my best plate is exposed.

Afterwards, when we agreed that you should bring your maid with you,

I told the girl that she would have a visitor, and that she ought to

be very thankful. But she only muttered some impertinence.

There is really no pleasing these low kind of people. So

to-day she has been very saucy, saying that she did not know how she

could get through to-morrow, turning away the people who come for

Christmas-boxes. For I never allow any. People get their

wages. What have you done with your other servant to-day,

Sarah? And how shall you manage with all your tradesmen's

people to-morrow? If I were you, I should just get over this

year by saying that you have not been here long enough to think of

giving any douceurs.'

'I let my servant go home, for she has a father and mother,

and ever so many brothers and sisters,' said Sarah. 'If I had

needed her services myself, I should have let her have one of them

with her, and given her a holiday on some other festive date.

As for Christmas-boxes, I shall give some—I know people get their

wages, but wages have to be regulated by all sorts of principles of

political economy. They are the wheels, as it were, of life,

and they go all the easier for a little oil. Human life

defined by a line, is as uncomfortable as would be the human figure

defined by a wire. One prefers a little mist about it, where

Hope may put out a wondering hand. One likes life weighed out

with something to turn the scale. Perhaps I look for so much

for myself in God's "more abundantly," that I like to make little

earthly types of it when I can.'

'Well, I only know that I get no Christmas-boxes,' said Jane;

'and what is good for me is good for other people.'

Sarah smiled secretly. That was all Jane knew!

Why, a little package directed to her, and containing a water-colour

sketch of Sarah's old American home, was already in charge of the

Parcels Delivery Company, and would arrive to-morrow—in an innocent

mystery to be solved—as many mysteries will be—in happy laughter, or

at least with a smile. At least, surely Jane would smile!

But the utmost Sarah could get from Jane that night was a

somewhat frigid expression of approval on a little poem by a

nameless writer, which Sarah had copied into her pocket-book, and

requested permission to read. It was called—

|

THIS DAY LAST YEAR.

This day last year! It has a solemn sound,

It has been sighed above so many graves,

About so many hopes, that faded, fell,

And sank among the wrecks on Time's dark waves.

This day last year! There has not been much

change,

For all the bitter change was long ago.

There was a time I could not speak these words,

The old dates meant such agony of woe!

But now I think it will not grieve me more

To see the shadow on this brow of mine:

Not for the old-time laughter of mine eyes

Would I a single thrill of pain resign.

For since 'this day last year' I've learned the truth

That sorrow bears a gracious light from heaven,

That truly they know little what they ask

Who envy those to whom it is not given.

For they who fear not, do not know the rest

When heavenly breezes bear away the fears;

And they who weep not, do not know the peace

When God's own angels wipe away the tears. |

'Yes, it is very pretty,' Jane said; 'but I have known

religion a great many years, and does not destroy one's natural

feelings. Grace is grace, dear Sarah, but nature is nature.'

'True,' Sarah answered, 'but is not nature the chalice, more

or less transparent, into which grace is poured from on high?'

Sarah did not stay late. She knew that Jane's hours

were very early, at least in the sense of retiring to her sleeping

chamber, though Jane had pointed out to her a little bookcase there,

with 'whose contents,' she said, 'she soothed and edified many

midnight hours.' Among the books Sarah noticed Hervey's

'Meditations among the Tombs,' Mrs. Rowe's ' Letters,' and

'Meditations,' Drelincourt on 'Death,' and some less standard works,

bearing such titles as 'Dark Days in the Wilderness,' and 'Secret

Cries of a Sad Heart.'

Poor Jane! She had leisure without life, sentiment

without sympathy, loss without love, a form without a faith!

Nevertheless, she was one in God's world, and as she kissed

Sarah and said it was nice to have had her with her, Sarah felt a

half remorseful pain that she could not help thinking to herself

that it is well that God does not leave unloved even those who are

very unlovable!

CHAPTER VIII.

|

One gentle look, one tender touch

Had done so much for me.—R. BULWER

LYTTON. |

IN the course of

the next day Sarah received a note from Jane:—

'DEAR

COUSIN,—Your parcel has

just arrived! It is very kind of you to think of these things,

and it is the first Christmas gift I have had for twenty years.

The postman was asking for his Christmas-box just as the porter

brought in your present; so I sent him down half-a-crown. I'm

sure my correspondence don't trouble him much, and the few letters I

have might stay away for all the good they are to me. But I

believe the post-office people are not too well paid, and so that is

the only concession I have made.

'My servant has given me notice to-day, which is of course

particularly inconvenient, as this is a bad season for hiring.

It would have put me about less to have let her have her mother

here. You see, I try to keep up discipline, and am only

punished for it.

'Your affectionate cousin,

'JANE.'

In the course of a few days, Sarah went to visit the family

who had sheltered the paralytic man. She did not go

empty-handed: beside some little valuable dainties, she took a small

sum of money, being fully aware that much kindness is neutralised by

the timidity that refuses to trust a deserving person with a little

cash to supply those little nameless daily wants which only ready

money can allay.

Whenever Sarah Russell gave relief—which was not very often,

because she rather sought to develop the healthier powers of

self-relief—she usually gave it half in kind, and half in cash.

She was not addicted to give relief at all where there was any

possibility that cash would find its way to the gin-shop.

Mrs. Stone had her special contribution. Among her very

miscellaneous luggage she had an old bolster. This she had

unpicked, had taken out the feathers, and quilted them into an old

chintz counterpane.

'Those cases are always so cold,' she said; they want a deal

of rubbing, and I'll go bail this poor creature can't get much.

I've heard my husband say that after his father had the strokes, his

greatest comfort was a down cover-lid that my husband saved up for

and gave him;' and Mrs. Stone sighed a portentous sigh.

Sarah Russell found the poor little house clean and quiet.

The decent, rather dejected-looking father was trying to make some

rude toys to sell in the street, the wife had just got some

needlework to do, and the eldest lad had found an errand boy's

place. The wife came down from the sick lodger's room, and

apologised for not asking the visitor to see the invalid. 'He

was that fractious, that the sight of a stranger was tortures.'

Sarah expressed no surprise. If she herself were dying,

she felt she could now bear to see anybody, to peacefully answer the

most impertinent well-meant inquiry, and to endure the most boring

curiosity. But she knew that it had not always been so with

her. She had known the frantic hiding of the hunted soul.

She knew when she had even shrank from friendship because with all

its kindness, its touch was too rough for wounds whose deep seat it

could not guess. She knew that there are times when, if we

would see God, we must turn our face to the bare wall and keep

silence, ay, and that such times must precede the illumination which

reveals God to us in the roughest human face, and the most awkward

human charity, though such times are not always followed by such

revelation. She did not altogether suppose that this poor waif

knew in what high search a stranger's appearance interrupted him.

Very likely he only felt he was more peaceable' when he was left

alone.

But the good woman was so delighted with Mrs. Stone's nice

warm quilt, that she would at once carry it up-stairs to display it.

She came down again wiping her eyes.

'I can't make out what he said,' she narrated; he can only

make a kind of noise, and there's only one of my little girls that

can understand him a bit. But he began to cry; and cuddled his

head down sideways on it to show how nice it was and how it pleased

him.'

When Sarah told Mrs. Stone this, Mrs. Stone cried too.

'I'm sure it's a poor concern to what my husband gave his father,'

she said, 'but I hope there's somebody to do the same for him if he

wants it,' she sobbed.

Sarah had not forgotten Mr. Halloween's ghostly survey of her

home on Christmas Eve. She had tried to realise what might be

the real state of the case. Was it possible that this man,

stunned by the shock of some terrible blow, had rushed into solitude