|

CORRESPONDENCE WITH

CHARLES KINGSLEY.

Taken from

CHARLES KINGSLEY, His

Letters and Memories of his Life

edited by his wife.

Published Kegan Paul, Trench & Co., London,

1888.

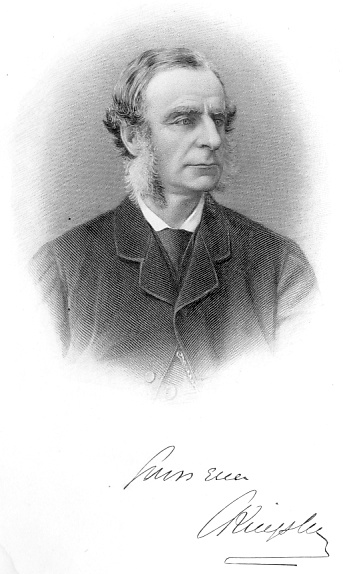

Rev. Charles Kingsley (1819 – 1875)

Church of England clergyman, Christian Socialist,

university professor, historian, and novelist.

From a carte-de-visite.

THE

following are extracts given without regard to dates, from letters

to Mr. Thomas Cooper, Chartist, author of the "Purgatory of

Suicides." When Mr. Kingsley first knew Thomas Cooper, he was

lecturing on Strauss, to working men; but after a long struggle his

doubts were solved. He is now at the age of 70, a preacher of

Christianity.[1]

――――♦――――

February 15, 1850.—"Many thanks for your paper. On

Theological points I will say nothing. We must have a good long

stand-up fight some day, when we have wind and time. In the mean

time, I will just say, that I believe as devoutly as you, Goethe, or

Strauss, that God never does—if one dare use the word, never

can—break the Laws of Nature, which are His Laws, manifestations of

the eternal ideas of His Spirit and Word—but that Christ's Miracles

seem to me the highest realizations of those very laws. How? you

will ask—to which I answer. You must let me tell you by-and-bye. Your thinkings from Carlyle are well chosen. There is much in

Carlyle's 'Chartism' and the 'French Revolution,' and also in a

paper called 'Characteristics,' among the miscellanies, which is

'good doctrine and profitable for this age.' I cannot say what

I personally owe to that man's writings.

"But you are right, a thousand times right, in saying that the

[co-operative] movement is a more important move than any

Parliamentary one. It is to get room and power for such works, and

not merely for any abstract notions of political right that I fight

for the suffrage. I am hard at work—harder, the doctors say, than is

wise. But 'the days are evil, and we must redeem the time,'—Our one

chance for all the Eternities, to do a little work in for God and

the people, for whom, as I believe, He gave His well-beloved Son. That is the spring of my work, Thomas Cooper; it will be yours;

consciously or unconsciously it is now, for aught I know, if you be

the man I take you for. . . ."

――――♦――――

EVERSLEY: November 2, 1853.—"Your

friend is a very noble fellow.[2] As for converting either you or

him, what I want to do, is to make people believe in the

Incarnation, as the one solution of all one's doubts and

fears for all heaven and earth; wherefore I should say boldly,

that, even if Strauss were right, the thing must either have

happened somewhere else, or will happen somewhere some day, so

utterly does both my

reason and conscience, and, as I think, judging from history, the

reason and conscience of the many in all ages and climes, demand an

Incarnation. As for Strauss [Ed.—probably David

Friedrich Strauss], I have read a great deal of him, and

his preface carefully. Of the latter, I must say that it is utterly

illogical, founded on a gross petitio principii; as for the mass of the book,

I would undertake, by the same fallacious process, to disprove the

existence of Strauss

himself, or any other phenomenon in heaven or earth. But all this is

a long story. As long as you do see in Jesus the perfect ideal of

man, you are in the right path, you are going toward the light,

whether or not you

may yet be allowed to see certain consequences which, as I believe,

logically follow from the fact of His being the ideal. Poor ――'s

denial (for so I am told) of Jesus being the ideal of a good man, is

a more serious evil

far. And yet Jesus Himself said, that, if any one spoke a word

against the Son of Man (i.e. against Him as the perfect man) it

should be forgiven him; but the man who could not be forgiven either

in this world or that to

come, was the man who spoke against the Holy Spirit, i.e. who had

lost his moral sense and did not know what was righteous when he saw

it—a sin into which we parsons are as likely to fall as any men,

much more

likely than the publicans and sinners. As long as your friend, or

any other man loves the good, and does it, and hates the evil and

flees from it, my Catholic creeds tell me that the Spirit of Jesus,

'the Word,' is teaching

that man; and gives me hope that either here or hereafter, if he be

faithful over a few things, he shall be taught much. You see, this

is quite a different view from either the Dissenters or

Evangelicals, or even the High-Church parsons. But it is the view of those old 'Fathers' whom they

think they honour, and whom they will find one day, in spite of many

errors and superstitions, to be far more liberal, humane, and

philosophical than

our modern religionists. . . . . "

――――♦――――

TORQUAY: 1854.—"I am now very busy at two things. Working at the

sea-animals of Torbay for Mr. Gosse, the naturalist, and thundering

in behalf of sanitary reform. Those who fancy me a 'sentimentalist'

and a

'fanatic' little know how thoroughly my own bent is for physical

science; how I have been trained in it from earliest boyhood; how

I am happier now in classifying a new polype, or solving a

geognostic problem of strata,

or any other bit of hard Baconian induction, than in writing all the

novels in the world; or how, again, my theological creed has grown

slowly and naturally out of my physical one, till I have seen, and

do believe more

and more utterly, that the peculiar doctrines of Christianity (as

they are in the Bible, not as some preachers represent them from the

pulpit) coincide with the loftiest and severest science. This

blessed belief did not

come to me at once, and therefore I complain of no man who arrives

at it slowly, either from the scientific or religious side; nor

have I yet spoken out all that is in me, much less all that I see

coming; but I feel that I

am on a right path, and please God, I will hold it to the end. I see

by-the-bye that you have given out two 'Orations against taking away

human life.' I should be curious to hear what a man like you says on

the point, for

I am sure you are free from any effeminate sentimentalism, and by

your countenance, would make a terrible and good fighter, in a good

cause. It is a painful and difficult subject. After much

thought, I have come to the conclusion that you cannot take away human life. That

animal life

is all you take away; and that very often the best thing you can

do for a poor creature is to put him out of this world, saying, 'You

are evidently unable

to get on here. We render you back into God's hands that He may

judge you, and set you to work again somewhere else, giving you a

fresh chance as you have spoilt this one.' But I speak really in

doubt and awe . . . .

When I have read your opinions I will tell you why I think the

judicial taking away animal life to be the strongest assertion of

the dignity and divineness of human life; [3] and the taking away

life in wars the strongest

assertion of the dignity and divineness of national life."

――――♦――――

1855.— "―― sent me some time ago a letter of yours, in which you

express dissatisfaction with the 'soft indulgence' which I and

Maurice attribute to God . . . .

"My belief is, that God will punish (and has punished already

somewhat) every wrong thing I ever did, unless I repent—that is,

change my behaviour therein; and that His lightest blow is hard

enough to break bone and

marrow. But as for saying of any human being whom I ever saw on

earth that there is no hope for them; that even if, under the

bitter smart of just punishment, they opened their eyes to their

folly, and altered their

minds, even then God would not forgive them; as for saying that, I

will not for all the world, and the rulers thereof. I never saw a

man in whom there was not some good, and I believe that God sees

that good far more

clearly, and loves it far more deeply, than I can, because He

Himself put it there, and, therefore, it is reasonable to believe

that He will educate and strengthen that good, and chastise and

scourge the holder of it till he

obeys it, and loves it, and gives up himself to it; and that the

said holder will find such chastisement terrible enough, if he is

unruly and stubborn, I doubt not, and so much the better for him. Beyond this I cannot say;

but I like your revulsion into stern puritan vengeance—it is a lunge

too far the opposite way, like Carlyle's; but anything better than

the belief that our Lord Jesus Christ was sent into the world to

enable any man to be

infinitely rewarded without doing anything worth rewarding—anything,

oh! God of mercy as well as justice, than a creed which strengthens

the heart of the wicked, by promising him life, and makes ―― ――

believe (as I

doubt not he does believe) that though a man is damned here his soul

is saved hereafter. Write to me. Your letters do me good."

――――♦――――

1856.—"You have an awful and glorious work before you,[4] and you do

seem to be going about it in the right spirit—namely, in a spirit of

self-humiliation. Don't be downhearted if outward humiliation,

failure, insult,

apparent loss of influence, come out of it at first. If God be

indeed our Father in any real sense, then, whom He loveth, He

chasteneth, even as a father the son in whom he delighteth. And

'Till thou art emptied of

thyself, God cannot fill thee,' though it be a saw of the old

mystics, is true and practical common sense. God bless you and

prosper you. . . .

" . . . Your letter this morning delighted me, for I see that you

see. If you are an old hand at the Socratic method, you will be

saved much trouble. I can quite understand young fellows kicking at

it. Plato always takes

care to let us see how all but the really earnest kicked at it, and

flounced off in a rage, having their own notions torn to rags, and

scattered, but nothing new put in the place thereof. It seems to me

(I speak really

humbly here) that the danger of the Socratic method, which issued,

two or three generations after in making his so-called pupils the

academics mere destroying sceptics, priding themselves on picking

holes in

everything positive, is this—to use it without Socrates' great Idea,

which he expressed by 'all knowledge being memory,' which the later

Platonists, both Greek and Jew, e.g., Philo and St. John, and after

them the good

among the Roman Stoics and our early Quakers, and German mystics,

expressed by saying that God, or Christ, or the Word, was more or

less in every man, the Light which lightened him. Letting alone

formal

phraseology, what I mean, and what Socrates meant, was this, to

confound people's notions and theories, only to bring them to look

their own reason in the face, and to tell them boldly, you know

these things at heart

already, if you will only look at what you know, and clear from your

own spirit the mists which your mere brain and 'organisation,' has

wrapt round them. Men may be at first more angry than ever at this;

they will think

you accuse them of hypocrisy when you tell them 'you know that I am

right, and you wrong;' but it will do them good at last. It will

bring them to the one great truth, that they too have a Teacher, a

Guide, an Inspirer, a

Father: that you are not asserting for yourself any new position,

which they have not attained, but have at last found out the

position which has been all along equally true of them and you, that

you are all God's

children, and that your Father's Love is going out to seek and to

save them and you, by the only possible method, viz., teaching them

that He is their Father.

"I am very anxious to hear your definition of a person. I have not

been able yet to get one, or a proof of personal existence which

does not spring from ŕ priori subjective consciousness, and which

is, in fact, Fichte's. 'I

am I.' I know it. Take away my 'organisation,' cast my body to the

crows or the devil, logically or physically, strip me of all which

makes me palpable to you, and to the universe, still I have the

unconquerable knowledge

that 'I am I,' and must and shall be so for ever. How I get this

idea I know not: but it is the most precious of all convictions, as

it is the first; and I can only suppose it is a revelation from God,

whose image it is in me,

and the first proof of my being His child. My spirit is a person;

and the child of the Absolute Person, the Absolute Spirit. And so is

yours, and yours, and yours. In saying that, I go on 'Analogy,'

which is Butler's word

for fair Baconian Induction. I find that I am absolutely I, an

individual and indissoluble person; therefore I am bound to believe

at first sight that you, and you, and you are such also This is all

I seem to know about

it as yet.

"But how utterly right you are in beginning to teach the real

meaning of words, which people now (parsons as well as atheists) use

in the loosest way. Take even 'organisation,' paltry word as it is,

and make them

analyse it, and try if they can give any definition of it (drawn

from its real etymology) which does not imply a person distinct from

the organs, or tools, and organising or arranging those tools with a

mental view to a

result. I should advise you to stick stoutly by old Paley. He is

right at root, and I should advise you, too, to make your boast of Baconian Induction being on your side, and not on theirs; for 'many

a man talks of Robin

Hood who never shot in his bow,' and the 'Reasoner' party, while

they prate about the triumphs of science, never, it seems to me,

employ intentionally in a single sentence the very inductive method

whereby that

science has triumphed. . . . Be of good cheer. WHEN the wicked man turneth from his wickedness (then, there and then), he shall save

his soul alive—as you seem to be consciously doing, and all his sin

and his

iniquity shall not be mentioned unto him. What your 'measure' of

guilt (if there can be a measure of the incommensurable spiritual) I

know not. But this I know, that as long as you keep the sense of

guilt alive in your

own mind, you will remain justified in God's mind; as long as you

set your sins before your face, He will set them behind his back. Do

you ask how I know that? I will not quote 'texts,' though there are

dozens. I will not

quote my own spiritual experience, though I could honestly: I will

only say, that such a moral law is implied in the very idea of 'Our

Father in heaven'. . . . "

". . . . You must come and see me, and talk over many things. That is

what I want. An evening's smoke and chat in my den, and a morning's

walk on our heather moors, would bring our hearts miles nearer each

other,

and our heads too. As for the political move, I can give you no

advice save, say little, and do less. I am ready for all extensions

of the franchise, if we have a government system of education

therewith: till then I am

merely stupidly acquiescent. More poor and ignorant voters? Very

well—more bribees; more bribers; more pettifogging attorneys in

parliament; more local interests preferred to national ones; more

substitution of the

delegate system for the representative one . . . ."

――――♦――――

June 14, 1856.—"It is, I know it, a low aim (I don't mean morally)

for a man who has had the aspirations which you have; but may not

our Heavenly Father just be bringing you through this seemingly

degrading work,

[5] to give you what I should think you never had,—what it cost me

bitter sorrow to learn—the power of working in harness, and so

actually drawing something, and being of real use. Be sure, if you

can once learn that

lesson, in addition to the rest you have learnt, you will rise to

something worthy of you yet . . . . It has seemed to me, in watching

you and your books, and your life, that just what you wanted was

self-control. I don't

mean that you could not starve, die piece-meal, for what you thought

right; for you are a brave man, and if you had not been, you would

not have been alive now. But it did seem to me, that what you wanted

was the

quiet, stern cheerfulness, which sees that things are wrong, and

sets to to right them, but does it trying to make the best of them

all the while, and to see the bright side; and even if, as often

happens, there be no

bright side to see, still 'possesses his soul in patience,' and sits

whistling and working till 'the pit be digged for the ungodly.'

"Don't be angry with me and turn round and say, 'You, sir, who never

knew what it was to want a meal in your life, who belong to the

successful class who have.—What do you mean by preaching these cold

platitudes

to me?' For, Thomas Cooper, I have known what it was to want things

more precious to you, as well as to me, than a full stomach; and I

learnt—or rather I am learning a little—to wait for them till God

sees good. And

the man who wrote 'Alton Locke' must know a little of what a man

like you could feel to a man like me, if the devil entered into him. And yet I tell you, Thomas Cooper, that there was a period in my

life—and one not of

months, but for years, in which I would have gladly exchanged your circumstantia, yea, yourself, as it is now, for my circumstantia,

and myself, as they were then. And yet I had the best of parents and

a home, if not

luxurious, still as good as any man's need be. You are a far happier

man now, I firmly believe, than I was for years of my life. The dark

cloud has passed with me now. Be but brave and patient, and (I

will

swear now),

by God, sir! it will pass with you."

――――♦――――

June, 1856.—"You are in the right way yet. I can put you in no

more right way. Your sense of sin is not fanaticism; it is, I

suppose, simple consciousness of fact. As for helping you to Christ,

I do not believe I can

one inch. I see no hope but in prayer, in going to Him yourself, and

saying: 'Lord if Thou art there, if Thou art at all, if this all be

not a lie, fulfil Thy reputed promises, and give me peace and the

sense of forgiveness,

and the feeling that, bad as I may be, Thou lowest me still, seeing

all, understanding all, and therefore making allowances for all!' I

have had to do that in past days; to challenge Him through outer

darkness and the

silence of night, till I almost expected that He would vindicate His

own honour by appearing visibly as He did to St. Paul and St. John;

but He answered in the still small voice only; yet that was enough.

"Read the book by all means; but the book will not reveal Him. He

is not in the book; He is in the Heaven which is as near you and me

as the air we breathe, and out of that He must reveal Himself;—neither priests

nor books can conjure Him up, Cooper. Your Wesleyan teachers taught

you, perhaps, to look for Him in the book, as Papists would have in

the bread; and when you found He was not in the book, you thought

Him

nowhere; but He is bringing you out of your first mistaken

idolatry, ay, through it, and through all wild wanderings since, to

know Him Himself, and speak face to face with Him as a man speaks

with his friend. Have

patience with Him. Has He not had patience with you? And therefore

have patience with all men and things; and then you will rise again

in His good time the stouter for your long batte . . . .

". . . . For yourself, my dear friend, the secret of life for you

and for me, is to lay our purposes and characters continually before

Him who made them, and cry, 'Do Thou purge me, and so alone I shall

be clean. Thou requirest truth in the inward parts. Thou wilt make me to understand

wisdom secretly.' What more rational belief? For surely if there be

any God, and He made us at first, He who makes can also mend His own

work if it get out of gear. What more miraculous in the doctrines of

regeneration and renewal, than in the mere fact of creation at all?

"I am glad to hear you are regularly at work at the Board. It will

lead to something better, doubt not; and if it be dry drudgery,

after all, some of the greatest men who have ever lived (perhaps

almost all) have had their

dull collar-work of this kind, which after all was useful in keeping

mind and temper in order. I have a good deal of it, and find it most

blessed and useful."

――――♦――――

April 3, 1857.—"Go on and prosper.[6] Let me entreat you, in

broaching Christianity, to consider carefully the one great

Missionary sermon on record, viz., St. Paul's at Athens. There the

Atonement, in its sense of a

death to avert God's anger, is never mentioned. Christ's Kingship is

his theme; the Resurrection, not the death, the great fact. Oh,

begin by insisting, as I have done in the end of 'Hypatia,' on the

Incarnation as morally necessary, to prove the goodness of the

Supreme Being. Insist on its being the Incarnation of Him who had

been in the world all along. . . . Do bear in mind that you have to

tell them of The Father—Their Father—of

Christ, as manifesting that Father; and all will go well. On the

question of future punishment, I should have a good deal to say to

you. I believe that it is the crux to most hearts."

――――♦――――

May 9, 1857.—"About endless torment . . . . You may say,—1.

Historically, that, a. The doctrine occurs nowhere in the Old

Testament, or any hint of it. The expression, in the end of Isaiah,

about the fire

unquenched, and the worm not dying, is plainly of the dead corpses

of men upon the physical earth, in the valley of Hinnom, or Gehenna,

where the offal of Jerusalem was burned perpetually. Enlarge on

this, as it is

the passage which our Lord quotes, and by it the meaning of His

words must be primarily determined.—b. The doctrine of endless

torment was, as a historical fact, brought back from Babylon by the

Rabbis. It was a

very ancient primary doctrine of the Magi, an appendage of their

fire-kingdom of Ahriman, and may be found in the old Zends, long

prior to Christianity.—c. St. Paul accepts nothing of it as far as

we can tell, never

making the least allusion to the doctrine—d. The Apocalypse simply

repeats the imagery of Isaiah, and of our Lord; but asserts,

distinctly, the non-endlessness of torture, declaring that in the

consummation, not only

death, but Hell, shall be cast into the Lake of Fire.—e. The

Christian Church has never really held it exclusively, till now. It

remained quite an open question till the age of Justinian, 530, and

significantly enough, as

soon as 200 years before that, endless torment for the heathen

became a popular theory, purgatory sprang up synchronously by the

side of it, as a relief for the conscience and reason of the

Church.—f. Since the

Reformation, it has been an open question in the English Church, and

the philosophical Platonists, of the 16th and 17th centuries, always

considered it as such. g. The Church of England, by the deliberate

expunging

of the 42nd Article which affirmed endless punishment, has declared

it authoritatively to be open.—h. It is so, in fact. Neither Mr.

Maurice, I, or any others, who have denied it, can be dispossessed

or proceeded

against legally in any way whatsoever. Exegetically, you may say, I

think That the meanings of the word αίώυ and αίώυιος have little or

nothing to do with it, even if αίώυ be derived from άεί always,

which I greatly doubt. The word never is used in Scripture anywhere else, in the sense of

endlessness (vulgarly called eternity). It always meant, both in

Scripture and out, a period of time. Else, how could it have a

plural—how could you

talk of the ćons, and ćons of ćons, as the Scripture does? Nay,

more, how talk of οΰτος ό αίώυ, which the translators, with laudable

inconsistency, have translated 'this world,' i.e., this present

state of things, 'Age,'

'dispensation,' or epoch—ίώυιος, therefore, means, and must mean,

belonging to an epoch, or the epoch, αίώυιος κολασις is the punishment

allotted to that epoch. Always bear in mind, what Maurice insists

on,—and what is

so plain to honest readers,—that our Lord, and the Apostles, always

speak of being in the end of an age or aeon, not as ushering in a

new one. Come to judge and punish the old world, and to create a new

one out of

its ruins, or rather as the S. S. better expresses it, to burn up

the chaff and keep the wheat, i.e., all the elements of food as seed

for the new world.

"I think you may say, that our Lord took the popular doctrine

because He found it, and tried to correct and purify it, and put it

on a really moral ground. You may quote the parable of Dives and

Lazarus (which was the

emancipation from the Tartarus theory) as the one instance in which

our Lord professedly opens the secrets of the next world, that He

there represents Dives as still Abraham's child, under no despair,

not cut off from

Abraham's sympathy, and under a direct moral training, of which you

see the fruit. He is gradually weaned from the selfish desire of

indulgence for himself, to love and care for his brethren, a divine

step forward in his

life, which of itself proves him not to be lost. The

impossibility of Lazarus getting to him, or vice versa, expresses

plainly the great truth, that each being where he ought to be at

that time, interchange of place i.e., of

spiritual state, is impossible. But it says nothing against Dives

rising out of his torment, when he has learnt the lesson of it, and

going where he ought to go. The common interpretation is merely

arguing in a circle,

assuming that there are but two states of the dead, 'Heaven' and

'Hell,' and then trying at once to interpret the parable by the

assumption, and to prove the assumption from the parable. Next, you

may say that the

English damnation, like the Greek κατάκρισις, is perhaps κρίσις simple,

simply means condemnation, and is (thank God) retained in that sense

in various of our formularies, where I always read it, e.g.,

'eateth

to himself

damnation,' with sincere pleasure, as protests in favour of the true

and rational meaning of the word, against the modern and narrower

meaning.

"You may say that Fire and Worms, whether physical or spiritual, must

in all logical fairness be supposed to do what fire and worms do do,

viz., destroy decayed and dead matter, and set free its elements to

enter into

new organisms; that, as they are beneficent and purifying agents in

this life, they must be supposed such in the future life, and that

the conception of fire as an engine of torture, is an unnatural use

of that agent, and

not to be attributed to God without blasphemy, unless you suppose

that the suffering (like all which He inflicts) is intended to teach

man something which he cannot learn elsewhere.

"You may say that the catch, 'All sin deserves infinite punishment,

because it is against an Infinite Being,' is a worthless amphiboly,

using the word infinite in two utterly different senses, and being a

mere play on

sound. That it is directly contradicted by Scripture, especially by

our Lord's own words, which declare that every man (not merely the

wicked) shall receive the due reward of his deeds, that he who, &c.,

shall be beaten

with few stripes, and so forth. That the words 'He shall not go out

till he has paid the uttermost farthing,' evidently imply (unless

spoken in cruel mockery) that he may go out then . . .

"Finally, you may call on them to rejoice that there is a fire of

God the Father whose name is Love, burning for ever unquenchably, to

destroy out of every man's heart and out of the hearts of all

nations, and off the

physical and moral world, all which offends and makes a lie. That

into that fire the Lord will surely cast all shams, lies,

hypocrisies, tyrannies, pedantries, false doctrines, yea, and the

men who love them too well to

give them up, that the smoke of their Βασαυισμός (i.e., the torture

which makes men confess the truth, for that is the real meaning of

it; Βασαυισμός means the touch-stone by which gold was tested) may ascend

perpetually, for

a warning and a beacon to all nations, as the smoke of the torment

of French aristocracies, and Bourbon dynasties, is ascending up to

Heaven and has been ever since 1793. Oh, Cooper—Is it not good news

that that

fire is unquenchable; that that worn will not die. . . . The parti prętre

tried to kill the worm which was gnawing at their hearts, making

them dimly aware that they were wrong, and liars, and that God and

His universe were

against them, and that they and their system were rotting and must

die. They cannot kill God's worm, Thomas Cooper. You cannot look in

the face of many a working continental priest without seeing that

the worm is

at his heart. You cannot watch their conduct without seeing that it

is at the heart of their system. God grant that we here in

England—we parsons (dissenting and church) may take warning by them.

The fire may be

kindled for us. The worm may seize our hearts. God grant that in

that day we may have courage to let the fire and the worm do their

work—to say to Christ, These too are Thine, and out of Thine

infinite love they have

come. Thou requirest truth in the inward parts, and I will thank

Thee for any means, however bitter, which Thou usest to make me

true. I want to be an honest man, and a right man! And, oh joy,

Thou wantest me to be

so also. Oh joy, that though I long cowardly to quench Thy fire, I

cannot do it. Purge us, therefore, oh Lord, though it be with fire. Burn up the chaff of vanity and self-indulgence, of hasty

prejudices, second-hand

dogmas,—husks which do not feed my soul, with which I cannot be

content, of which I feel ashamed daily—and if there be any grains of

wheat in me, any word or thought or power of action which may be of

use as

seed for my nation after me, gather it, oh Lord, into Thy garner.

"Yes, Thomas Cooper. Because I believe in a God of Absolute and

Unbounded Love, therefore I believe in a Loving Anger of His, which

will and must devour and destroy all which is decayed, monstrous,

abortive in His

universe, till all enemies shall be put under His feet, to be

pardoned surely, if they confess themselves in the wrong, and open

their eyes to the truth. And God shall be All in All. Those last are

wide words. It is he who

limits them, not I who accept them in their fulness, who denies the

verbal inspiration of Scripture.

"P.S. When you talk to them on the Trinity, don't be afraid of

saying two things.

"They will say 'Three in One' is contrary to sense and experience. Answer, that is your ignorance. Every comparative anatomist will

tell you the exact contrary; that among the most common, though the

most puzzling

phenomena is multiplicity in unity—divided life in the same

individual of every extraordinary variety of case. That distinction

of persons with unity of individuality (what the old schoolmen

properly called substance) is to

be met with in some thousand species of animals, e.g., all the

compound polypes, and that the soundest physiologists, like Huxley,

are compelled to talk of these animals in metaphysic terms just as

paradoxical as,

and almost identical with, those of the theologian. Ask them then,

whether, granting one primordial Being who has conceived and made

all other beings, it is absurd to suppose in Him, some law of

multiplicity in unity,

analogous to that on which He has constructed so many millions of

His creatures

"I have said my say on the Trinity in the end of 'Yeast,' and in the

end of ' Hypatia' . . . ."

.

.

.

.

.

"But my heart demands the Trinity, as much as my reason. I want to

be sure that God cares for us, that God is our Father, that God has

interfered, stooped, sacrificed Himself for us. I do not merely want

to love

Christ—a Christ, some creation or emanation of God's—whose will and

character, for aught I know may be different from God's. I want to

love and honour the absolute, abysmal God Himself, and none other

will satisfy

me—and in the doctrine of Christ being co-equal and co-eternal, sent

by, sacrificed by, His Father, that He might do His Father's will, I

find it—and no puzzling texts, like those you quote, shall rob me of

that rest for

my heart, that Christ is the exact counterpart of Him in whom we

live, and move, and have our being. The texts are few, only two

after all; on them I wait for light, as I do on many more:

meanwhile, I say boldly, if the

doctrine be not in the Bible, it ought to be, for the whole

spiritual nature of man cries out for it. Have you read Maurice's

essay on the Trinity in his theological essays? addressed to

Unitarians? If not, you must read it. About the word Trinity, I feel much as you do. It seems unfortunate

that the name of God should be one which expresses a mere numerical

abstraction, and not a moral property. It has, I think, helped to

make men

forget that God is a spirit—that is, a moral being, and that moral

spiritual, and that morality (in the absolute) is God, as St. John saith God is love, and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and

God in him—words

which, were they not happily in the Bible, would be now called rank

and rampant Pantheism. But, Cooper, I have that faith in Christ's

right government of the human race, that I have good hope that He is

keeping the

word Trinity, only because it has not yet done its work; when it

has, He will inspire men with some better one."

NOTES.

1. Thomas Cooper's autobiography, published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1872, is a book well worth reading for its

own sake and for the pictures

of working class life and thought, which it reveals.

2. This refers to a letter in which Thomas Cooper

says, "My friend, a noble young fellow, says, you are trying to

convert him to orthodoxy, and expresses great admiration for you. I

wish you success with him, and I

bad almost said I wish you could next succeed with me; but I think

I am likely to stick where I have stuck for some years—never

lessening, but I think increasing, in my love for the truly divine

Jesus—but retaining the

Strauss view of the Gospel." "Ah! that grim

Strauss," he says in a later letter, "How he makes the iron agony go

through my bones and marrow, when I am yearning to get hold of Christ! But you understand

me? Can you help me? I wish I could be near you, so as to have a

long talk with you often. I wish you could show me that Strauss's

preface is illogical, and that it is grounded on a petitio principii. I wish

you could bring me into

a full and hearty reception of this doctrine of the Incarnation. I

wish you could lift off the dead weight from my head and heart, that

blasting, brutifying thought, that the grave must be my 'end all.'"

3. See Sermon on Capital Punishment, preached in

1870, by Rev. C. Kingsley. (All Saints' Day and other Sermons. C. Kegan Paul & Co.)

4. Thomas Cooper had now re-commenced lecturing at

the Hall of Science on Sunday evenings, simply teaching theism, for

he had not advanced farther yet in positive conviction.

5. Thomas Cooper had been given copying work at the

Board of Health; and his hearers at the Hall of Science, already

made bitter by his deserting the atheist camp, made the fact of his

doing government work and

taking government pay, a fresh ground of opposition to his teaching.

6. T. Cooper had written to say that he had now

begun the "grand contest." "God has been so good to me that I must

confess Christ, and we shall have greater rage now that I have come

to Christianity.

|