|

[Previous Page]

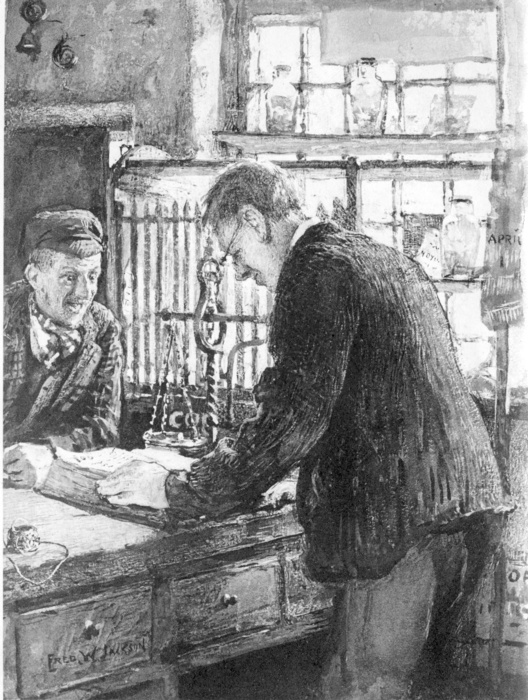

A COLLIER'S SPREE.

MANY years ago

when colliers were getting enormously high wages—some earning as

much as five pounds per week—I heard so many stories of their

intemperance and extravagance, that I determined to ascertain by my

own personal experience, how far the reports current might be

credited. I accordingly set out one morning with the intention

of visiting the coal producing districts round about "Th' Heights,"

and having a peep into the "pubs," that I might be an eye-witness of

those disgraceful orgies believed, by "correct" people, to be of

frequent occurrence in these places.

An hour's walking brought me to the colliery district of

Pendlebury. I wandered over a fairly wide area, but saw

nothing disorderly or indicative of extravagance. A storm

coming on, I turned into the "Cart and Tits," which was the

principal hostelry in the village, the model of a substantial

wayside public, and the "fowt " of which was thronged with carts.

I made my way at once to the tap-room, where I could hear something

was going on, encountering along the passage several curious

glances, expressive of surprise that broad cloth should be courting

the society of prevailing fustian, and risking the loss of caste

that was sure to follow its being "blown " upon.

Strange!—I did not meet with the scenes I expected to find

even in this promising place. The company present were mostly

carters and their followers, with a sprinkling of others whose

calling it would be difficult to make out. The operative

mining interest was meagrely represented; for only about three, and

these mere youths, could positively be identified as being connected

with coal-getting. The floor was not "slat o'er" with spilled

drink; as very little of any kind of beverage was being consumed,

except by such customers as rushed in, drained their measure at

once, and went on their journey. Amongst others, such as I may

term "fixtures" for the day, little business in the soaking line was

doing. At the rate they were going on, a shilling or so would

last them until nightfall; and it was then short of noon. They

were mostly occupied in bantering a rather pulpy specimen of the

genus homo, whose nickname of "Burgy" at once attested the

quality of the man and the nature of his vocation. This

occupation afforded rare fun for the whole company, not even

excepting your humble servant; but as the probability was that, if

carried too far, it would end in a fight, singing was substituted; "Burgy"

himself leading off with one of those old-fashioned country ballads

in which you are advised to "shun bad company;" the singer holding

himself up as the particular "warning" to be observed; and who, like

many others, had resolved to mend his ways when it was too late.

After this kind of entertainment had gone on for about

half-an-hour, and when I was disappointedly contemplating a retreat

homewards, a man entered the room, who hailed me by the familiar

salutation of—"Good mornin' sir!"

I returned the greeting, and drank to the new-comer's good

health.

"It's cowd!" he said, with an accompanying shiver that was

contagious.

I owned that it was bitterly cold, and disagreeably damp as

well.

The stranger sidled round the table behind which I sat, and

dropped himself upon the adjoining bench with a grunt that appeared

to settle the question of his whereabouts for some time to come.

The motive for his singling me out from the rest of the company will

appear anon.

"It's cowd!" he repeated, giving with a stick he carried an

emphatic rap upon the floor.

This time I nodded my acquiescence in the remark, which was

without further reiteration handed over to the record of undisputed

facts.

My companion for the time was an elderly man, and appeared to

have had many rude buffetings with the world. His frame was

spare and stooping, one shoulder being raised above the other, as if

elevated to that position by that inscrutable dispensation which

assigns to one man dominion over another, or rather by the more

obvious agency attributable to the habit of leaning upon a stick.

The coat he wore was made before it was possible for shoddy

to be palmed off for the durable article; and was of a cut familiar

in the days of our grandfathers. This portion of his attire

was buttoned to the "highest storey;" the space betwixt that and his

chin being occupied by the folds of a faded and scanty comforter, of

a rather primitive design, but which had undoubtedly been considered

as something out of the common way when it shone in its fresher

tints. From that upwards were the features of a man who at one

time might have been handsome in that particular region, but had

suffered them to be remodelled after a fashion not to be found in

the portfolio of "English Beauties." His nose had been

tampered with to an extent that removed its outline considerably

from the centre of the face, and impressed with a seal that nothing

but a hammer, or the tip of a clog, could have rendered so

positively indelible. His grey eyes twinkled vivaciously for

his years, and were concealed at times by the neb of his hat, which

had a trick of flapping down when its owner was in a particularly

demonstrative humour, and might have served as a mask had occasion

required. He was altogether a queer piece of humanity—of the

type designated "hard as nails," and which modern luxury is

rendering it impossible to perpetuate.

"Pinch o' snuff?" demanded my friend, turning round to me

rather sharply.

"I don't carry a box," I replied.

"Have one with me?" And he held out a small repository

of the refreshing dust, from which I took the proffered pinch.

"Thank you," I said, and sneezed a compliment to its quality.

"Aw dunno' mind if aw do," he said, as if in reply to some

question I had put to him.

"Do what?" I asked, at a loss to comprehend the meaning of

the observation.

"Ha' twopenno'th wi' yo'!" he replied.

"Oh, by all means!" I said. And the old man gave an

authorative rap upon the table.

"Twopenno'th o' whisky!" he said to the waiter, who came

bustling in at the summons.

The whisky was brought, and a conversation at once commenced,

but which it was difficult to continue in consequence of the noise

that came from the other side of the room.

"Yo' dunno' kennel o' this side th' park?" said my companion,

scanning me over as if I had been a living prodigy, just imported.

I admitted I did not dwell in that neighbourhood at all, or

near it.

"Too fine bred," he observed, after the first promptings of

curiosity had been satisfied. "Mostly brokken-yured uns abeaut

here. Well, come—here's to'ard yo'!" And he took his

glass and sipped, as if afraid of its being emptied too soon.

"Mostly colliers in this neighbourhood, I suppose?" I

wanted to draw the old man out.

"Aye, meaudiwarts," he replied, as if that was the term

usually applied to them.

"Pephaps you are one?" I presumed.

"Aw ha' bin," he said; "but aw never geet so mich brass as

they're gettin' neaw."

"Probably not," I observed.

"Nawe; lung shifts—hard workin's—little wage: that wur my

soart."

"A long time ago, I should think."

"No' so very. Li'en o' mi side, yeawin at a two-foout

till aw've had segs as hard as dur-flags, while silk wayvers han bin

walkin' eaut brid-neezin' (bird-nesting), or sit o'th' hearthstone

tellin' boggart-tales. Come'n whoam—had a swill, as if aw'd

bin a slutchy fowt—swallowed mi porritch—noane sich thick uns,

noather—kebbed on a stoo', starin' at th' foire till bedtime—haumpled

up steers—had what wur coed mi sleep—up an' at it agen—as if that

wur o aw're sent i'th' wo'ld for. If one could manage to raise

a battle o'th' week-end, it wur welly o'th' comfort one had.

These whelps known nowt, dun they Eccles as like! "

"Too fond of their drink and their play," I supposed.

"Dunno' know ut they're so mich different to other folk i'

that respect," the old man replied. "Ther happen seen moore at

it, an' makken moore noise o'er it. But some are so sly an'

quiet, they'n swallow a barrel afore onybody else known they'n

tasted. Folk ut wear'n betther clooas nur me, too."

"I don't see much drinking going on to-day," I remarked.

"Being Monday, I expected seeing scores of people drunk."

"Wheere han yo' looked?" he said, with a sly raising of the

eyelids.

"All round the neighbourhood," I replied.

"Ah!" he observed with a shake of the head. "Yo'n

looked i'th' wrung shop. Yo' should ha' looked reaund

Manchester; peeped into th' hotels theere: they'n gan o'er gooin' to

common aleheauses."

I felt there might be some truth in that statement, and

prepared myself for hearing something of a more than ordinary

character.

"Got above drinking fourpenny!" I remarked, to encourage the

old man to proceed.

"Fourpenny, sure!—aye, or sixpenny oather," he replied, with

an implied sneer in his manner of alluding to the popular beverage.

"Tenpenny ud hardly go deawn neaw. Nowt short o' champagne 'll

suit a collier's throttle i' these days! Yo' happen never yerd

abeaut thoose two ut went on th' spree once fro' Halshy Moor?"

I confessed I had not.

"Rare do, they had. Aw wish aw could just come across

owd Ab-o'th'-Yate some time, aw'd tell him o th' skit. He'd

mak' summat eaut on't, aw'll be bund. He knows a bit o' summat

abeaut champagne hissel, owd Ab does. Noane quite as big a

leatheryead as he purtends to be. Dun yo' know him?"

"I have a slight remembrance of having seen the man," I

admitted. "If you'll tell me the story I'll see that it gets

to his ears. He can please himself whether he makes use of it

or not "

"Then yo'st have it." The old man hereupon looked into

his glass, which he tilted on one side, the better to observe how

matters stood in that locality. I took the hint, and ordered

in a second twopennyworth of whisky after which our friend proceeded

with his story.

"These two meaudiwarts," he began, "had moore brass nur they

knew what to do wi'. It's a very awkert perdickyment fur a mon

to be put in ut doesno' believe i' savin'. They'd fuddled two

days that week; an' when they coome to reckon up, it had nobbut cost

'em abeaut three-an'-sixpence a piece; so that wouldno' do, noather

at th' pit nor at th' wharf. It wur plain enoogh they'd ha' to

save summat, if they didno' mind what they'rn abeaut. Well,

they tried keepin' dogs; an' they fed 'em wi' mutton chops, an'

oysters, an' milk, till they geet so fat they slaked the'r tongues

eaut as if they'rn gooin' mad; so they had to get beaut 'em.

Beside, th' childer had begun to ate what th' dogs couldno' swallow;

an' that, they thowt, ud mak' the'r stomachs too preaud for porritch

an' stuff. Th' next thing they tried wur bettin'; but o'

someheaw they'd to' mich luck o' the'r side. I'stead o'

lessenin' the'r brass it made it moore, an' that wur makkin' bad

wuss! So they'rn driven to the'r wit's end what for t' do

next.

"Well, they held a meetin' one day when they'rn off the'r

wark, an' consulted one another as to what wur th' best thing to be

done, as the'r pockets wur gettin' desperately too heavy, an' they

some talk of another strike for moore wage."

"What's th' use o' strikin' for moore wage," Bill said to

Bob, "when we dunno' know heaw to spend what we're gettin' neaw? "

"Not a bit o' use!" Bob said. "It'll nobbut mak' eaur

wives preauder nur they are; an' that's needless. Eaur Moll

towd me t'other day ut if we did get another rise hoo should begin

a-wearin' shinnons."

"Just th' same at eaur heause!" Bill said. "It's nobbut

a week sin' aw didno' know what to do wi' mi brass, so aw bowt eaur

Lizz two new cheears, ut aw gan four-an'-sixpence apiece for; an' it

made her so preaud ut hoo gan a three-legged stoo' away ut wur mi

gronfeyther's, an' ut had bin sit on till it wur worn hollow."

"Aye, that's way wi' some women," Bob said; "the'r heauses

are never fine enoogh for 'em. We'n a flag carpeted neaw, an'

sich a thing never wur known i'th' breed afore. They'n be

sendin' th' childer to th' skoo next! But we mun stop that

off."

"But heaw," Bill said, "when we conno' spend th' brass i' no

gradely way? It's o very weel talkin' wi' a empty pocket; but

when it's full, an' no other road for it, it puts us in a fix."

Bob puts his studyin'-cap on for a bit, an' then his face

breetened up like pooin' th' top off a lamp.

"Aw have it neaw," he said, an' he rose up on his feet.

They'd bin sittin' on the'r heels, as, aw dar'say, yo'n seen

colliers do. Aw've keaweart o' that fashin misel' mony a hundert

heaurs.

"Well! what is it?" Bill said. An' he rose up, too.

"Wurt ever in a ho-tel?" Bob o' Bill's said to his mate.

"Nawe," Bill said; "but aw've mony a time thowt aw could like

to goo i' one, if it's nobbut to see heaw th' nobs carry'n on theere,

an' what sort o' stuff they drinken. Aw've bin towd they'n ale

theere at thrippence a glass! We met get through a shillin' or

two theere yezzily, an' have a cab whoam."

"Well! what saysta?" Bob said. "Mun we try a

barrowful?"

"Aye," Bill said. "Aw'm i'th' mind if theau art.

They conno' tak' us up if we payn us road."

"Let's goo upo' th' next train," Bob said. So they geet

reaund their een wesht, an' off they went to Manchester.

They'rn a good while afore they could pike a shop eaut; an'

they'rn lunger afore they durst ventur' in when they fixed upo' one.

But at last they shoolt [shovelled] the'r courage t'gether, an' went

in. They met a chap i'th' lobby ut looked like a box-organ

grinder; but as he're bare-yeaded, they thowt he must live theere.

"Heigh, surry!" Bill said, "which is th' best drinkin' shop?"

"Do you want the smoke-room?" th' mon said. And he

star't at 'em as if he'd a notion th' police ud be after 'em afore

lung.

"Aye," Bob said; "aw reckon we's want a pipe o' 'bacco afore

we leeaven."

"Don't allow pipes!" th' mon said; "only cigars."

"It mun be a top shop," Bill whispered to Bob, "if they dunno'

alleaw pipes! Aw never smooked a cigar yet, but aw'll have a

try. We's have a chance o' spendin' summat here, chus heaw."

"This way," th' mon said. An' in th' colliers went.

It wur a big reaum they went in, abeaut four times th' size

o' this, an' it wur full o' gentlemen, makkin' noise like a skoo.

They'n reechin' away at cigars as if ther a smookin' match, an'

drinkin eaut of o sorts o' queer glasses. Whoa should th'

Halshy Moor chaps see pearcht i' one corner at th' fur end but th'

mesthurs they worched for; an' rare an' gloppent they wur! Th'

mesthurs twigged 'em in a minute; an' they'rn gloppent too, as it

wur likely they would be; an' noather Bill nur Bob felt so

comfortable at th' fust. But they soon geet o'er that, as they

knew th' mesthers dustno' cheep to 'em as things wur. Beside,

they'd as mich reet there as onybody else, if they paid for what

they had.

"Ne'er mind 'em, Bob!" Bill said. "We are here;

so let's put a good face on it. Hommer that table, as if

theau're knockin' for a barrel!"

"But what mun we have?" Bob said, raisin' a fist like a

pile-mo [a long shafted mallet used for driving in piles].

"Well, aw think we'd best start low, an' goo up to th' top,"

Bill said. "What dost' say to a quart o' ale?"

"O reet!" Bob said; an' deawn his knuckles went wi' a rap at'

seaunded like hittin' th' table wi' a flat-iron.

"What is it?" a mon said, 'at had a white napkin on, like a

pa'son.

"What's that to thee?" Bill said, thinkin' th' mon wur

meddlin'. "Thee mind thi own business, an' aw'll buy thee a

brass hat!"

"Aye, it would look betther on thee if theau'd mind thi

praichin' i'stid o' comin' to sich shops as this," Bob said.

"What were you knockin' for?" th' mon said, rayther sharply.

"If it'll do thee ony good to know," Bill said, "we'rn

knockin' for a quart o' ale."

"Mild or bitter?" th' mon said; an' he poo'd a tin booart

fro' th' back on him, an' skraumt some empty glasses on it.

"Wheay, art theau t' waiter-on?" Bill said, givin' th' mon a

good stare.

"Yessir," th' mon said.

"Well, aw took thee to be a blackin' chap eaut o' wark!" Bill

said. "There's nob'dy's cooat i' this hole 'at shoines like

thine. Theau's oather starved a peg for it, or else it's a

thank-yo'-sir. Well, stop, owd mon!" he said, seein' at th'

waiter wur gooin' away in a bit of a huff, "bring us a quart o'

gradely ale. Never mind weather it's mild or bitter, so as

it's th' best an' good messur."

"Two pints?" th' waiter said; an' he turned back to 'em.

"Aye, theau con bring it i' two pints," Bob said, "It'll

nobbut have a bit moore eautside to it, that's o. An' aw say,

owd mon, bring us a cigar apiece as weel."

Th' waiter darted eaut, an' e'enneaw he comes back wi' two

pints o' ale i' glasses as big as fleawer-pots; an' he'd a box wi'

him 'at favvort a little male-ark (meal-ark) wi' three divisions in

it.

"Threepence—fourpence—sixpence." he said, puttin' th' box upo'

th' table, an' pointin'to th' cigars wi' his finger.

"Aw reckon th' biggest are twice as good as th' leeast," Bob

said; "so goo in for a sixpenny go, Bill; aw'll pay this reaund.

Heaw mich is th' lot, owd mon?"

"Two shillings," th' waiter said.

"That's a rare start' Bill!" Bob said, as he hauled eaut a

two-shillin'-piece, an' threw it upo' th' table. "We'n a

chance o' bein' a bit expensive at last."

"A light, sir?" th' waiter said; an' he gan 'em a leeted

papper apiece abeaut th' length of a feeshin' rod.

They set to wark wi' the'r cigars, but when they'd bin tryin'

a quarter of an heaur, an' had covered th' table o'er wi' brunt

papper, they'rn as far off leetin' 'em as when they started!

"Heaw dun yo' manage t' leet these things?" Bill said to a

gentleman ut sit at th' end o'th' table.

"Unlap 'em till you find a road through 'em!" he said.

"They're rather tight."

Well, they kept unlappin', an' firin' up, till th' cigars wur

as ragged beggars, as beggars, an' as thin as candle-weekin; an'

when they'd howd together no lunger they threw 'em away, an' said

they hadno' bin eddicated for nowt o' that soart. Bob had set

foire to his cap neb, an' brunt a piece eaut afore he gan in.

They mopt up the'r pints; an' as they couldno' see onybody else

drinkin' ale, they'd ha' summat betther. So they hommert at th'

table agen for th' waiter; an' when he coom they axt him if ther

onybody i'th' reaum drinkin' champagne. Th' waiter looked

reaund, an' said ther' wurno'

"Then," Bill said, "we'n have a bottle. Mun us Bob?"

"O reet!" Bob said, "it's thy turn t' pay next."

"Well, bring it in," Bill said.

Th' waiter wur just gooin' eaut when one o'th' pit mesthurs

beckont on him.

"What han yon chaps bin orderin'?" he said to th' waiter.

"Champagne," th' waiter said.

"Well, here's a shillin' for thi," th' mesthur said; "an'

bring 'em a bottle o' katchup i'stead o' champagne. They'n

never know th' difference."

Th' waiter grinned, touched his yure, an' off he went.

Well, he browt 'em a bottle o' katchup i'stead o' champagne,

an' two little glasses a bit bigger nur thimbles; an' he put 'em on

th' table wi' as much palaver as if they'd bin two kings, or local

booards.

"Heaw mich have aw t' pay?" Bill said to th' waiter.

"Ten-and-six," th' waiter said; an' he looked as if here

givin' th' stuff away at that price.

"Ten-an'-six?—that's sixteen pence," Bill said. He're a

good reckoner for one at wur no scholar.

"Ten—shillings—and—sixpence!" th' waiter said; an' at every

word he tapped th' table wi' th' corkscrew.

Bill looked at Bob, an' Bob looked at Bill; an' then they

star't at one another. Bill whistled, an' dived his hont into

his pocket.

"We shanno' ha to knock so oft at this rate, Bob," he said,

as he thumped th' brass upo' th' table.

"Nawe," Bob said, "We conno' goo above another turn reaund

o'th' pully. But teem eaut, an' let's be tastin' what it's

like. Aw've yerd so mich abeaut this champagne 'at it sets me

a-yammerin."

Bill tem'd eaut, an' tasted; an' his face went o shapes!

"Theau doseno' favvor likin' it," Bob said; "or else theau

doesno' want me to taste."

"They may ha' the'r champagne for me," Bill said, as soon as

he could spake. "But if that wur sowd for fourpen'y, nob'dy ud

sup it."

Bob tried his meauth wi' a glass, an' he poo'ed a face as

writhen as Bill's when he'd swallowed.

"Aw think ther's a good deal i'th' name of a thing, if this

is champagne," he said. "For my own sel' aw'd as leif drink

seeny tae."

"Aye, or cockle broth!" Bill said. "But we munno'

leeave it, theau knows. We'se happen like it betther when we'n

getter used to it. We didno' like smookin' th' fust time we

tried."

"Nawe; but it'll take a fuddle or two afore we liken that

stuff," Bob said.

"What dost' co' it to taste like?"

"Aw dunno' know," Bill said, "unless it's like brunt flannel

an' traycle. What does theau think it's like?"

"Nowt 'at ever aw've tasted sin' aw had th' jaunders," Bob

said. "It favvors as if th' doctor should stand o'er me, an'

say, "Theau'rt like to tak' it if t' meeans t' get weel. Try

another dose on't."

Bill tem'd another glass eaut, an' swallowed it like takkin'

physic.

"It tastes betther this time, Bob," he said, smackin' his

lips. "Aw dar'say th' next bottle 'll be grand."

Bob tried another shove i'th' meauth, an' he thowt same as

Bill, 'at it didno' taste as ronk as th' fust glass did.

They'rn gettin' used to it, yo' seen!

"It doesno' mak' me a bit fuddlet," Bill said, tryin' his

legs upo' th' floor. "One ud ha' thowt 'at a glass o'

champagne o'th' top o' what we'n had afore would ha' auter't one's

balance a bit."

"Aw'm as sober as a pump, yet!" Bob said, gettin' up an'

stretchin' hissel'. "If we'd gone as far as th' 'Nob Inn, an

spent so mich i' whiskey an' wayter, we should ha' bin ready for a

wheelbarrow neaw. But get on wi' thi drinkin', surry! it'll

happen find us eaut afore we'n done wi't. Should aw sing,

thinksta'? That 'ud happen stir things up a bit."

"Aye, brast off wi' a stave!" Bill said; "ther'll oather be

quietness or else a bigger noise when theau starts."

Beaut ony moore ado, Bob rear't his yead back, an' begun a

singin'; but afore he'd getten to th' fust tryin'-o'er-agen th'

waiter coome, an' said they didno' want no sort of a mess there.

If here poorly he'd betther have a cab, an' go whoam.

"Poorly!" Bob said, lookin' as if he could like t' ha' put th'

waiter i'th' doctor's honds. "Dustno' know good singin' when

theau yers it, theau donned-up mopstail?"

"Gentlemen don't make that noise here," th' waiter said, an'

he turned away.

"Yer thee, Bill," Bob said; "yond mon says gentlemen dunno'

sing i' this cote. What does he mean by that?"

"He happen sings hissel', an' tak's th' hat reaund," Bill

said. "Theau's seen sich like knockin' abeaut Knott Mill

Fair."

"Aye, that'll be it," Bob said. "Sup agen, owd mate.

We con drink if we munno' sing."

Well, they emptied th' bottle, an' knocked for another but

they couldno' say 'at they gradely liked champagne when they'd

finished th' second looad.

"Heaw does thi cubbart feel, Bob?" Bill said; an' he begun a-polishin'

his waistcoat buttons wi' his hont.

"Noane so yezzy!" Bob said; an' he laid his elbows on his

knees an' grunted. Ther's a meetin' bein' howden abeaut th'

bottom o' my throttle, an' if they' isno' a strike soon it'll cap

me. Aw dunno' wonder at folk wantin' a cab when they'n been

drinkin' champagne. Aw shall want a heearse, or summat, if aw

drink mich moore o' that stuff. Oh, my!"

"It puts me i' mind o' drinkin' sooap suds for th' worms,"

Bill said; an' he gan his senglet-buttons another polishin'. "Ther's

oather a dog battle, or a rot-hunt, gooin' on under my fist.

Another bottle 'ud happen set us to reets, Bob. Dost' think it

would?"

"Ugh!" Bob said, puttin' his hont o'er his meauth, like a wax

plaister. "Dunno' name it agen! Ift' does ther's a pit

here wheere they may wind eaut on beaut engine. There'll be a

self-actin' pump a-workin', too. Howd thi noise! Ugh!

Oh my! Let's be shiftin', afore we're turn't eaut."

Bill didno' need twice axin', for he'd gone very white abeaut

th' bracket of his nose, and he'd a sort of a ramblin' feel abeaut

his top button.

"Let's goo as far as th' Mayor's Parlour, an' have a whisky

a-piece," he said. "That'll happen put things to reets."

"Aw'm quite willin' for a change, as Bowzer said when he're

walkin' up th' lung steears at th' New Bailey; so come on," Bob

said.

Wi' that they crept eaut o'th' hotel, rayther quietly, no

deaut, an' went deawn to th' Mayor's Parlour, i' Short Millgit.

Heaw mony whiskies they had theere, they never could keaunt; but it

took a lot afore they could shift th' "champagne," an' bring

quietness to disturbed quarters. The'r pockets wur in a

middlin' satisfactory state o' emptiness when th' spree wur

finished, so 'at they could goo whoam wi' hearts as leet as the'r

clooas. They'd forgetten t' save brass for a cab, an' as

they'rn too far gone for th' train to tak' 'em, they had to walk.

A rare journey they had, aw believe, afore they londed whoam.

They moandert abeaut Sawfort for mony an heaur: gettin' into o

soarts o' streets, till at last they fund the'rsel's somewheere

abeaut th' Delphi, wi' the'r arms clipt reaund a lamp-post, as fast

asleep as th' lamp-post itsel'! When they wakkent, they'd

getten a notion o someheaw into the'r yeads 'at they'rn at th'

bottom o'th' coal-pit, waitin' to be wund up; an' they'rn very nee

frozzen to deeath.

"Aw wonder heaw lung he's goin' t' be afore he starts a-windin'?"

Bill said to Bob.

"Aw dunno know," Bob said; "but if he doesno' wind soon,

aw'll swarm th' rope. This is a cowd hole, Bill! Aw

think they must ha' oppent another air shaft. By gum, surry!"

he said, lookin up at th' lamp, "he's stopt th' engine for summat.

We're within a yard or two o'th' top. Theau may do as t'

likes, but aw'll swarm for it."

So Bob set eaut on his journey up th' lamp-post, leeavin'

Bill to shift for hissel' as best he could.

"This is a rare thick rope, mate," he said, as he meaunted

up. "A patent safety, aw should think." Then his yead

struck agen a piece o' iron 'at stuck eaut like a arm; an' it

knocked him so dateless 'at he dropt, like a lump o' roofin' reet

upo' Bill, 'at wur just framin' for followin'.

They'rn never gradely wakkent till then; an' raly they star't

at one another when they fund they'rn rowlin' in a gutter, i'stead

o' bein' knockt into a jelly at th' bottom of a coal-pit. Heaw

they geet whoam they couldno' tell; but, when they went to the'r

wark th' mornin' after, they fund 'at everybody i'th' pit knew

abeaut spree at th' hotel an' kept sheautin'—"another bottle o'

katchup;"—till at last they fund it eaut they'd bin drinkin' that

i'stead o' champagne; an' rare an' mad they wur! It ever they

yer th' last o' that, it ''ll be when they con yer nowt at o.

By the time our friend had finished his story the snow had

cleared off, and the sun had set about its business apparently in

right good earnest. After thanking the old man for the manner

in which he had entertained me, and promising that I would at once

put myself in communication with "Owd Ab," I rose to depart, leaving

him gazing at the bottom of his glass, which I took care was

sumptuously replenished. I had not made my journey for nothing

after all.

――――♦――――

FOO'S.

EVERYBODY'S

a foo' at summat; but my owd rib says, "If they're foo's at one

thing, they'll be foo's at another." Aw say hoo's wrung theere;

but hoo sticks to it hoo's reet, an' ut it's me ut's wrung. Aw

know it's no use tryin' to convart her; so aw'll see if aw con talk

to someb'dy else.

Aw say everybody's a foo' at summat. They' never wur a

yead put on a pair o' shoothers, but, if yo' wur to feel it o'er,

yo'd find a crack or a soft place somewheere. It met no' be a

crack as wide as a church dur, nor a place as soft as a turf-clod;

but soft an' shaken for o that. An' heaw we becoen one another

for th' bits o' leatheryeadishness ut we conno' help but show!

An' heaw we setten eaursel's up on a hee peearch, an' praichen deawn

to thoose ut we thinken hanno' sense to look up, an' try to get at

us! We dunno' calkilate, at th' same time, ut someb'dy may be

talkin' deawn to us, for bein' such foo's as to think we'n moore

sense nor other folk. Yorneyism, to th' very chapter an'

verse; but we conno' see it!

Someb'dy says—th' wo'ld's kept on by foo's, an' ut ther'd be

poor doin's for some folk beaut 'em. Rogues 'ud ha' to look

eaut for fresh pastur' wheere folks' wits hadno' bin put to th'

grindlestone; an' thoose ut liven by rogues an' foo's met follow.

Newspappers 'ud ha' little to say; lawyers 'ud ha' nowt to do nobbut

scrat the'r wigs; doctors ud ha' to swallow the'r own physic, an'

pa'sons ud ha' moore time to beslutch one another, a job ut some on

'em liken betther nur pointin the'r finger to'ard another wo'ld, an'

tryin' t' mak' us reet i' this. What must become ov eaur red

jackets aw dunno' know; for ther'd be no moore thumpin' upo' th' owd

war tub (drum); no moore makkin' holes i' one another's stomachs; no

moore trailin' o'th' owd striped rag abeaut, an' darrin' onybody to

touch it! Some good howsome puncin' would be o ut ud be wanted

when we geet a bit cranky, an very little o' that 'ud satisfy us.

One could find very nee as mony sooarts o' foo's as faces; so

it 'ud tak' a bit o' time fort' reckon 'em up an' sort 'em. Aw

nobbut meean to tackle one or two partikilar sorts ut aw have abeaut

me. Sometimes thoose folk ut purtend to be t' fausest (the

most cunning), are th' biggest yorneys ov o, an' they're th'

plagueyest sooart we han to deeal wi'. But aw'll just put one

o' these upo' th' table, so ut you con see what he's like.

For th' fuss thing he's as stupid as a jackass, an' it's a

pity his ears are no' th' length they should be! Yo' couldno'

mak' him t' believe ut onybody's ony sense beside hissel' if yo' wur

to talk to him wi' a hommer, an' let him feel what yo' had t' say;

an' aw'm sure aw'st ne'er try. It's no use him readin' ony

books; he knows o ther' is in 'em, an' a good deal moore ut ther'

should ha' bin. He never goes to noather church nor chapel,

becose he could taich th' pa'son moore nur he knows; an' as for

religion makkin' him a betther mon—he's quite good enoogh for th'

wo'ld he's in, or ony ut's waitin' for him. Ther's aulus

summat gooin' wrang for him, i' Lunnon fowt speshly. He'd

manage things i' that shop betther nur o th' wiseacres ut ever threw

the'r wynt away at a sleepy parlyment. Owd Noll Crummell wur

smo-drink to him, an' that he'd let 'em see, if they'd nobbut put th'

guiders o'th' owd state waggin in his hont. He'd show 'em heaw

to cleean th' war score (national debt) off, an' mak' everythin' an'

everybody look as breet as a summer Sunday wi' a new suit o' clooas

on. It's a pity nob'dy con see him as weel as he con see

hissel', an' ut we should be gropin' through th' slutch i'th' dark,

an' knockin' th' owd waggin to pieces wi' bad droivin', when this

wiseacre could mak' it goo like a railroad, an' hang as mony

lanterns abeaut it as 'ud leet it reaund th' corner o'th' wo'ld.

But it aulus wur so. Nob'dy knows what a gowden karnel ther's

shut up i' his nut; an' they'll never find it eaut, becose th'

shell's to' thick to get at it. So we may grope an' tumble

abeaut eendway. Knock him off th' table, an punce him for

tumblin'.

Ov a very common sort o' leatheryead is yo'r good-natured foo',

ut says brass (money) wur made reaund so ut it could roll abeaut,

an' mak's this into an excuse for spendin' o he gets, an' happen a

bit o' summat moore nur he con co his own. I' some cases we

find this yorney is summat beside a foo'; for some time when he's

fund th' bottom ov his pocket before he's tired o' yerrin' folk

praise him for bein' "a rare good sort," he goes whoam, an' puts th'

wife's een i' mournin', becose hoo conno' put him a supper under his

nose ut 'ud be good enough for a strawberry-faced justice.

Generally speakin' this foo's heause isno' quite a palace.

Th' windows as no' very promisin' for a start. Th' heause

window has a short curtain made o' faded print, an' poo'ed as tight

as a drum for t' mak' it raich across; an' it's fifty to nowt ut one

or moore o'th quarrels (squares) are brokken eaut int' a ragged

sore, or docthered wi' a papper plaister. Th' chamber window

is screened off, like th' front ov a gallanty show, wi' an' owd

petchwark bed-cover, hanged upo' two nails. Goo into th'

heause. Ther'll be no danger on yo' breakin' yo'r shins agen

th' mahogany! Ther's nowt nobbut three cheears an' a stoo'.

If aw must chuse, aw'd rayther sit me deawn upo' th' stoo' for

safety, becose th' cheears are like "Berm Joe,"—knock-a-kneed o' one

side, an' bowlegged o'th' tother, an' th' bottoms are like crow-neests

ut han wintered badly. Th' table—ther's nobbut one—has three

or four dirty spoons on it, an' happen as mony knives ut han bin

made widows through th' childer usin' th' forks for gardenin' i'

the'r way. Ther's a dirty basin or two, an' a brokken pitcher

ut looks as if it had been cryin' till churn-milk tears had run

deawn th' sides.

If it's th' weshin'-day, ther's a line stretched across th'

foire-place, wi' a two-thri (few) hauve-wesht rags hanged on it.

Th' hesshole's full o' hess (ashes), an' th' fender's plashed o'er

wi' suds an' milk. Th' childer are like th' heause—bare an'

dirty. One on 'em's makkin' a ship eaut ov a piece o'th'

table-top. That's th' janious o'th' family, an'll come to

summat some day! At ony rate his feyther says so when he's

swaggerin' i'th' ale-heause nook abeaut his heause an' his childer,

as if the'r nowt like 'em nowhere for bein' forrad an' smart.

Another o' this precious lot should be nussin (nursing) th' little

un; but hoo sits at th' eend o'th' fender, leetin' papper at th'

fire, an wonderin', if thoose are th' best ov her days, what hoo'll

be like when hoo's a woman. Th' choilt's laid upo' th'

hearthstone, nussin' itsel',—daubded up to th' een wi' porritch an'

traycle, an' atin' cinders as a soart o' relish after dinner.

Th' mother's dabbin' away at summat in a crackt mug; neaw an' then

seawsin' th' childer wi' a weet hond, an' sheautin' like a mad-cap

at 'em, an' tellin' 'em hoo'll knock the'r heads off the'r shoothers,

or writhe the'r little necks reaund, as soon as hoo's done weshin'.

This is summat like a good-natured foo's heause, becose aw

know mony a one o'th' sort; an' when aw come for t' calkilate heaw

mony scamps it tak's fort' keep one o'these leatheryeads i' concait

wi' hissel', aw breek eaut in a cowd swat, an' cuss th' whul wo'ld

for lettin' 'em run loose!

Another sort o' foo's—an' a rare kennelful on 'em ther'

is—are thoose ut run starin' after women, as iv ther' nowt i'th'

wo'ld beside ut wur fit to be looked at, an' ut winno' stop ut nowt

short of a rope or a razzor, as if soul an' body wurno' worth keepin'

t'gether beaut a pratty wench wur grinnin' at 'em, an' lookin' feaw

at everybody beside. Aw'm no' quite sure whether these are no'

th' biggest leatheryeads ov o. They're what one may co

whoppers at ony rate. Aw dunno' think so mich at a great

hobblin' lad ut's just begun o' gropin' abeaut his chin for th' smo'

end ov a beeart, starin' his e'en eaut ov his yead at a saucy besom

ut's aulus lookin' at hersel', as if her own een wur made for nowt

else; but when a grey-yeaded sinner ut con hardly get his shoon-heels

off th' greaund, puts his e'e windows on, an' goes blinkin' at some

faded duchess wi' tight stays an' a blue nose, an' talks at her same

as if they'rn booath on 'em i'th' best o'the'r days, it's time

someb'dy interfered.

Aw knew one o' these owd blinkerts once; an' every neet he

sluthert his shoon a-seein' an owd duchess ut favvort hoo'd bin hung

up amung dried yarbs. A weddin' wur made up, an' th' foo' had

a coach for t' tak' 'em to th' church, as if the'r Makker hadno'

done enoogh for em wi' givin' 'em legs, but owt to ha' put wheels to

'em i'th bargain! Th' woman tried to look as yunk an' pratty

as a pot shepherdess; but geet on badly wi' it, an' afore they went

into th' church, hoo stood o'er t'other wife's grave, an' whimpert a

bit,—though at th' same time, if hoo thowt ther' ony chance on her

comin' to life again, hoo'd ha' had th' coffin lid nailed deawn wi'

tenpenny nails, an' a looad or two o' weight-stones tem'd upo' th'

grave beside.

When th' weddin' wur o'er, an' that gowden bant, as they

co'en it, teed as fast as it could be, they set off to Blackport, or

Southpool—aw've forgetten which, becose aw'm no quality chap—an'

tarried theere a fortni't, though th' fust wife never so mich as

seed th' sae, nor thowt o' sich a thing, bein' a dacent woman.

They coom back like a lord an' a lady; but th' day after, one on 'em

had to go to his wark, an' t'other to her housekeepin', if hoo knew

owt abeaut it. Hoo hadno' bin used to weetin' her fingers for

owt beside weshin' her face, so by th' week end ther' as mony dirty

pots lee abeaut as would ha' filled a wheelbarrow. Th'

honeymoon (traycle-moon aw co it) wur getter i'th' last quarter, an'

a very thin bit, too, it wur! It ud soon be dark o'th' moon,

th' rate it wur gooin' on at. Hoo gan eaut her weshin'.

Bake hoo couldno', an' when hoo should ha' mended th' husbant's

shirt, hoo gan it to th' ragmon, an' said it wurno' fit for wearin'

ony lunger. Hoo turned eaut to be as big a sloven as ever

"Black Sam's" wife wur, an' no dog i' Hazlewo'th 'ud ha passed her

beaut givin' her a shake, as if it had mistakken her for a mop.

Hoo sowd her rings for gin, if her husbant 'ud let her ha' no brass;

an' hoo sluthert abeaut in a pair o' clogs made eaut o' top-boots,

an' wi' a yead as roogh as a haycock, an' her clooas same as if

they'd bin tossed on her back wi' a pikel (pitchfork)! T'other

side o'th' bargain wur as mich gone i'th' meant (moult) as hoo wur;

an' neaw ther' isno' sich a pair of curnboggarts i' o Hazlewo'th as

they are. Th' jackass met ha' known ut a woman ut wur aulus

donned up, an' did nowt but read po'try an' books abeaut young lads

an' wenches runnin' off wi one another a-getten wed, ud never do for

a wife for him. Hoo wanted three or four sarvants, an' a

carriage, an' someb'dy t' dondle abeaut her, an' tak' her to th'

playheause, an' Karsey Moor races, an' doancin' shops; an' then for

t' be a little bit poorly to'ard mid-summer, so ut hoo could goo to

th' saeside, an' strollop abeaut theere for a month or two, as if

folk neaw-a-days couldno' get on beaut bein' blown a bit wi' owd Daf

Jones's ballis. Hoo'd pop't into th' wrung shop; an' when a

woman finds it eaut ut hoo's made a mistake o' that sort, it's wo-up

wi' her an' thoose abeaut her, too, for as mich o' this life as they

han to live t'gether. If hoo's bin aimin' at flyin' o' her

young days, an' has never bin able to raise her feet off th' greaund,

an' neaw, i'stid o' gettin' a lift, gets a seause—hoo tumbles i'th'

gutter, an' tarries theere till hoo's ready for cartin' off to th'

churchyard. Hoo's bin as big a foo' as onybody. Get th'

tongs, an' lift 'em booath off th' table!

If ther' are women-mad foo's, ther' are foo's quite o't'other

side o'th' hedge,—fog's ut believen if a mon spakes to a woman, it's

same as puttin' his foot in a rotten-trap, or his neck in a

noose—he's to be hob-shackled for life. These belung to th'

clever sort o' yorneys, an' a pratty kittle on 'em ther' is, as far

as my exparience tak's me! Aw con tell one as soon as ever aw

clap my e'en on him. If he's a young un, ut hasno' gan o'er

bein' marred wi' his mother, he'll ha plenty o' brass i' his pocket,

an' isno' partikilar abeaut folk knowin' it. He walks abeaut

by hissel' o'th' edge o' dark; an' if he yers a pair o' pattens

beheend him, or sees a red cloak afore him, he looks abeaut for a

gap ut he con dart through, an' get eaut o'th' road.

Whenever yo' meeten him he'll be sure to have his honds in

his pockets, an' owder he gets an' deeper he thrutches 'em.

He'll be walkin' abeaut th' rate ov a snail ut's ta'en to crutches,

an' mooastly wi' his chin nar his clogs nur it should be for a

chicken. If he says owt, he's sure to talk abeaut things ut

are no i'th' common way; an' he'll bother yo' as ill as a boat-hoss

wi' some cranklety notion ut's bin hatchin' in his yead for happen a

hay-time or two. It's seldom he puts his best clooas on ov a

Sunday, so ut he'll groo owd i'th' same hat, an' same cooat ut he

had made when his great-gronmother wur buried. Yo' may know

him when he's getten int' years by that, for he'll look like an' owd

brid i' young fithers.

But this foo' never gets owd in his own e'en. He fixes

upo' a hobbyhoss when he's in his yard-wide days, or what "Owd Pee"

would co th' beginnin' ov his puppyhood, an' rides it till he con

howd on no lunger. He'll happen keep pigeons, or hens, or

ducks, or dogs, or brids—an' it's a wonder to him heaw onybody'll

gi'e these up for th' sake ov a woman. His mother praises him

for bein' th' best lad i' England, an' aw da'say wi' some reeason,

for though a foo', he may no' be th' wo'st son ever marred, an' a

mother 'll soon put t'other to. He conno' do wrung for her,

chus what he does, if he'll keep hissel' to hissel'. Hoo aulus

has his shirt th' whitest ov onybody's, an' keeps him o'th'

hearthstone as snug as an owd tabby cat, till he's fit for bein'

nowheere else. But when hoo's gone, an' he finds a two-thri

grey yures in his whiskers, an' a dry gutter or two abeaut his e'en,

an' his sisters han o getten wed, an' ther's nob'dy nobbut him an'

his feyther left, he begins o' lookin' sich a pictur' o' misery as

conno' be likened to nowt ut goes upo' two legs.

Ther's one o' these lives i' eaur fowt neaw, ut we coen "Slogger,"

an' he's fairly a seet to be seen! He's as ragged an' as dirty

as ever owd "Mungo" wur, an' so bad tempered ut, if th' childer

meeten him onywheere, they scuttern away, like a lot o' chickens

when ther's a dog abeaut. He's aulus lived under th' same

thatch, an' he doesno' know ut he could live under ony other.

It's th' thatch ut his feyther an' mother dee'd under, an' sin' then

he's lived theere by hissel'. Twenty year sin' (heaw time

slips o'er!) he're quite a swipper young chap. Nowt very grand

abeaut him; but he're aulus cleean, an' his clooas, if they wurno'

as fine as some folk's, wur kept i' good fettle. But he set so

leet o' women ut aw felt sure he'd never be wed as lung as he lived;

an' so far, aw've bin a fortin-teller. When aw towd him aw're

gooin' t' be wed, he made o sorts o' gam' on me, an' kept shakin' a

leg at me, for t' let me see it wur loce, an' showin' mea hontful o'

brass, an' sayin' aw should never be plagued wi' havin' holes i' mi

pockets when a wife had getten howd on me.

Well, aw geet wed, like a foo', as Slogger thowt, an' in a

while after, ther' a young "Ab" chipped his shell, an' chellupt i'th'

kayther (cradle) like a young throstle ut's ne'er tried it wings.

Eaur "Joe" followed, an, then eaur "Dick" said it wur his turn an'

ever sin' th' kayther has hardly gan o'er rockin'. We geet as

thrung as a little skoo', an' welly as noisy. Every year we

had t' buy a new porritch dish, an' every time it had to be a size

bigger. It wur hard scrattin' for 'em, aw con tell yo'; wi'

wark chep, an' atin'-stuff dear! But when Setterday neet coom,

an' we'd raised a bakin', th' heause looked as brisk as a wakes.

Th' childer would ha' bin runnin' abeaut wi' a mouffin' apiece, th'

size of a trencher—beawlin' 'em across th' floor, an' stickin the'r

fingers through th' middle, an' makkin' pinwheels on 'em.

Slogger would ha' comn i'th' thrung ov o this, an' axt me if

aw could do wi' a week's fuddle, or a rant abeaut th' country.

He knew eaur Sal 'ud fly at him like a cat; but he did it for t'

plague me with, as he thowt, an' he'd ha' run grinnin' eaur o'th'

heause, an' shakin' a leg at me. But he's done neaw, an'

ther's nowt but th' warkheause for th' foo'.

――――♦――――

DOOIN' THE'R BEST.

"IF ther's a men

onywheere abeaut ut con lay his hont on his senglet, an' say ut ever

sin' he begun puncin' his road wi' his own clogs he's tried to mak'

th' best o' everythin', aw could like to see his honest face i'

Walmsley Fowt. If he'll promise to come o'er some Setterday, eaur

Sal shall brew a peck o' drink, an' mak' a thumpin' pottito-pie; an'

he shall ha' sich a blow-eaut as 'll mak' his buttons gi'e notice

they conno' stond nowt o'th' soart agen. We'n send a balloon up, an'

we'n foire eaur Ab's bobbin-gun, an' eaur Joe an' Dick shall put on

the'r Sunday garters, as if it wur a haliday. Mi owd Rib shall put

her best cap on, an' th' bed-geawn [A morning dress for working in] hoo nobbut wears o' club neets. An' mi best olive breeches, ut han

never bin had on sin' owd Colley wur buried, shall be drawn o'er mi

shanks, an' flourished abeaut th' fowt i' honour o'th' visit."

This notice aw gan eaut one neet i'th' "Owd Bell" kitchen, an'

though it's mony a year sin' nob'dy's bin yet, so ut sich like folk

mun be scarce. Aw conno' say ut aw know one o'th' soart, an' aw've

had mi een abeaut me ever sin' aw could use 'em. One neet after aw'd

bin a bearin' whoam to Manchester, th' owd stockin'-mender breetened

up her face, an' laid her hont upo' mi knee, an' said hoo thowt aw

desarved booath th' drink an' pottito-pie misel'. But then aw'd gan

fippence a yard for a new bed-geawn for her that day; an' browt a

new pair o' socks an' a ricker for th' young'st choilt; an' a curran

loaf fro' Scholes's at Plattin'; so it wur no wonder her sayin' what

hoo did. Hoo knew at th' same time aw'd bin guilty o' mony a

yorneyish trick, sich as gettin' moore fourpenny nur aw could carry

straight, an' venturin' a penny or tuppence on a race when aw could

ill afford to lose. Does th' cap fit onybody?

Well, aw'm not within a peck o' drink an' a pottito-pie yet, if

ther's onybody con come an' claim it. Aw dunno' think ut eaur fowt's

as bad a place as some holes aw've waded through; but aw see no

danger o'th' drink bein' drunken, or th' pottito-pie bein' etten by

ony o' mi neighbours. Not yet, at ony rate, though they're shappin'

to'ard it. Some han spent brass when they knew it would ha' bin betther i' the'r pockets. Others

han letten things slip through

the'r fingers ut 'll never give 'em a chance o' grabbin' at 'em agen;

an' one or two ov a common breed o' leather-yeads ut never tried to

do owt gradely i' the'r lives, putten it eaut o'th' raich ov others

for t' help 'em. Aw dunno' know heaw it is amung folk ut liven i'

grand heauses, an' getten the'r livin' wi' the'r cooats on the'r

backs; but aw know heaw it is wi' folk sich like as me, thoose ut

han th' mooest comin' in are th' wo'st off, an' th' last to keep

straight. Thoose ut are nobbut gettin' fro' nine to twelve shillin'

a week are scrattin' like a dog at a rat hole for t' pay the'r road;

but some o' thoose ut are gettin' above a peaund a week dunno' seem

for t' care abeaut dooin' exactly as they'd like to be done by; an'

if folk are yessy wi' 'em they getten moore carless, an' begin a-gooin'

fury nur they con wade. They getten into shop-books, an' putten

ale-scores on, an' han clooas off th' Scotchman; an' after a while

they getten so bothert wi' folk comin' a-seein' 'em, an' walkin'

eaut wi' black looks, ut they takken advantage o' some fine moonleet

neet, an' go'en away for th' benefit o' the'r health.

Some on 'em mun do things very grand, whether they con afford it or

not. They'n ha' fine clooas, an' fine heauses wi' carpets on th'

floor, while sich as me are fain to have a little bit ov a cot, wi'

a twothri plain sticks abeaut, an' a carpet at a penny a peck eaut

ov a sondbarrow. They mun have a great lump o' beef browt to th' dur

ov a Setterday, wi' a little ticket on it, an' a white cloth o'er

it, while eaur Sal has to fotch eaur bit on a plate, an' no sich a

big un, noather. Other things they'n ha' browt th' same road, an'

when th' rent chap comes he's fain to get eaut o'th' heause beaut

brass; for they'n ha' this thing an' that thing done afore they'd

pay a haupenny, and generally they sticken to what they sayn. What

looks strange to me is ut this soart o' folk han moore uncles nur

ony other relations; an' they getten 'em to tak' care o' the'r best

clooas fro' Monday mornin' to Setterday neet for fear o' thieves

gettin' howd on 'em! They nobbut go'en once a fortnit to church; an'

that's th' Sunday after th' pay day; though why they're partikilar

to that Sunday happen someb'dy wiser nur me con tell.

Aw recollect one time when things wur middlin' brisk i' eaur fowt,

wayvers gettin' abeaut twelve shillin' a week, an' other trades

twice an' three times as mich, they' a mon i' Hazlewo'th thowt he'd

begin a-gooin' abeaut wi' new pottitoes, an' green stuff. So he geet

a donkey an' cart, an' tried his luck. He coom i' eaur fowt mony a

time beaut sellin' a pottito, or a cabbitch; an' he wonder't heaw it

wur. Folk did get new pottitos fro' somewheere, becose he'd seen th'

scrapin's upo' th' middens. Well, one day he met Jim Thuston, an' he

axt him if he could explain heaw it wur ut he couldno' sell his

pottitoes.

"Theau happen wants brass for 'em!" Jim Thuston said.

"Wheay, doesno' theau?" th' pottito chap said.

"Yigh," Jim said, "but aw dunno aulus get howd on't when aw want it! Nob'dy con sell nowt neaw-a-days unless they keepen a book. When

folk wur dooin' badly aw could ha' getten a bit o' ready brass. But neaw they're betther off, they spend it upo' finery, an' th'

sae-side; an' aw have to wait o' mine, an' sometimes lunger nur aw

like on."

"Well, an' does theau trust o th' fowt?" th' pottito chap said.

"Nawe," Jim said. "If aw did that, aw should ha' my keaws clemmed

to deeath, an' very soon, too. Aw nobbut trust th' poorest neaw, tho'

aw went amung th' middlin's at fust, an' did a bit amung th' quality

till aw geet my fingers nettled; an' then aw begun a-weedin' em. But aw'll tell thee what to do. Go to th'

"Owd Bell," an' look at th'

back o'th' kitchen dur. Theau'll see a lot o' ale scores choked up

theere, wi' th' names o' thoose ut owe 'em. Look which are th'

biggest, an' which are th' leeast, an' if theau doesno' know what to

do after that, theau'rt a hard larner."

Th' pottito chap went to th' "Owd Bell," an' sit hissel' deawn i'th

kitchen, an' knockt for a pint. When th' londlady browt th' drink

in, he axt her if hoo'd shut th' dur while he stopt, as he couldno'

stond a draught if it wur summer time. Th' londlady shut th' dur,

an' th' pottito chap fixed hissel' at back on't. It wur choked

(chalked) o'er fro' top to bottom wi' ale scores an' other bits o'

things. Some on 'em wur woppers, too! Th' mon begun a-readin' 'em

o'er to hissel', an' markin' 'em deawn in his noddle. Aw mun own ut

mine wur amung th' lot, lest folk met think aw're swaggerin'. Th'

figures ran summat like these:—

"Smoot Dody—Sixty-three pints, fifteen cigars, a bottle o' rum, an'

two dozen eggs." He works up at th' cons, an' gets good wage. Aw mun

keep away fro' his dur.

"Shoiny Jim—another o'th' same breed—Fifty one pints, sixteen peaund

o' bacon, an' a brokken window." Aw mun keep o'th' blynt side o'

him, too.

"Smo-Cop—Thirty-four pints, twelve hauve-eaunces o' 'bacco, an' two

pint pots brokken." He's a good shop at th' Knowe factory. He's

hardly to mi likin'.

"Blackey—Twenty-three pints, eight hauve-eaunces o' 'bacco, an' two

tin-full o' toasted cheese." That mon gets his thirty-two shillin' a

week. Aw'st be shy at him aw think. What next?

"Billy o' Tummy's—Eight pints, an' two hauve-eaunces o' 'bacco."

Come, that's summat like. Billy's nobbut a wayver. Aw'll stop at his

dur, if it's oppen.

"Jack o' Flunter's—Eight pints an' a mowffin an' cheese." Jack works i'th' greaund when ther's no buildin' gooin' on, an' doesno' get

mich; but it seems he's nar straight nur some on 'em. Aw think aw

may ventur to leeave a boilin' theere.

"Ab-o'th'-Yate—Nine pints. At th' length within a pint. Th'

bearin'-whoam day o' Setterday. Promises to pay up then." Aw think,

aw may leeave a twothri theere. Ab's a wyndy soart ov a foo hissel',

but aw may trust his wife."

Well, just as he're getten to th' bottom o'th' dur th' londlady

comes in, an' catches him at th' back on't.

"What, are yo' lookin' at my shop-book?" hoo says.

"Aye," th' mon said. "Aw thowt at th' fuss it wur some soart o'

music, but aw conno' mak' a tune eaut on't."

"Nawe, nor me noather!" th' londlady said. "Aw may whistle o'er it,

aw think, afore aw get some on't rubbed off. Aw'll tak' a

hauve-a-creawn for two o'th' top rows neaw, an' think aw've made a

good bargain. Thoose ut owe 'em could pay 'em off if they would;

they getten brass enoogh."

"What would yo' tak' for thoose at th' bottom?" th' mon said.

"Oh, thoose are as good as paid," th' londlady said.

They aulus clearn th' score off when they'n ta'en the'r wark whoam,

an' never go'en above ten pints in a fornit, though aw dust trust 'em

moore. But it's just here—thoose ut han th' leeast wanten th' leeast,

an' thoose ut han th' mooest keep wantin' moore, till they hardly

known wheere to stop. Aw believe it's so th' wo'ld o'er. If aw could

get five shillin' for th' lot aw dunno' expect bein' paid for, aw

should be very glad, for th' dur wants paintin'. It hasno' bin

painted this dozen year, aw'm sure."

Well, th' chap went eaut, wonderin' if he should ever have a chance

o' paintin' his cart sides after he'd made em into a shop-book, an'

he said—

"Gee up, Jinny!"

Th' pottito chap, after he'd read a lesson eaut o'th' "Owd Bell

kitchen dur, drove straight to Walmsley Fowt afore he gan a sheaut;

an' when he geet through th' yate he made th' fowt fairly ring agen

wi' "New pottitos, eightpence a score! Pay when yo' con! Pay when yo'

con! Hie yo' women—hie yo' women!"

Folk coome to the'r durs; but he never offert to stop th' cart till

he geet facin' owd Thuston's, what we co'en th' quality end o'th'

fowt. Theere he turned reaund, an' towd Jenny for t' behave hersel',

like a good donkey, for hoo'd a good deeal to go through. As he

looked reaund he could see yeads pop't eaut o' durs—some wi' caps

on; some witheaut, an' one or two wi' ribbins flyin' abeaut 'em. He didno' like th' ribbins; they'rn too fine; nor th' bare yeads;

they'rn too slovenly. He felt th' mooest partial to th' white caps

an' check approns. A middlin' way, he thowt, aulus looked th'

gradeliest.

"Neaw then," he said to hissel', "aw'm same as owd Knocker when he'd

sown rapeseed in a mistake for parsley, aw've some weedin' to do,"

an' he sheauted agen—"New pottitos, eightpence a score! Male (meal)

in a deesh—male in a deesh! Cracken i'th' pon like limestones i'

rain! Hie yo' women—hie yo' women! Pay when yo' con—pay when yo'

con!"

Ther a wench coome up to th' cart wi' a little fancy basket in her

hont, an' hoo axt th' chap if he'd let her mother ha' five peaund o'

pottitos, an' hoo'd pay him o' Setterday.

"Whooa is thi mother?" he axt.

"Misses Trimmer," th' wench said.

"Oh, oh, Missis Trimmer is it? Then theau'rt Shoiny Jim's wench?" th'

mon said.

"They coen mi feyther so, but mi mother doesno' like it," th' wench

said.

"Thi feyther gets good wages, doesno' he?"

"Yigh, sometimes he does. But he lost two days last week wi' drinkin'."

"Well then," th' chap said, "tell thi mother hoo mun wait ov her

potittos till Setterday, as aw'm gooin' t' begin a-drinkin' misel'. Gee up, Jinny, an' dunno' keep lookin' at folk so mich!"

Th' cart wheels hadno' turned reaund above twice afore a woman wi'

as mony ribbons abeaut her yead as' ud ha' done for a rush cart hoss,

nips eaut of her heause like a doancin' wench at a fair, her face as

full o' grins as if hoo're wastin' a month's stock at once; an' hoo

says—

"Aw con do wi' a hauve score o' pottitos, if yo'n trust me till th'

week end. They're very nice uns, aw see."

"What does yo'r husbant do?" th' mon wanted to know.

"He works for Meadowcroft's, i' Birchwood."

"Oh, then he gets middlin' o' wage?"

"Well," th' woman said, "he nobbut gets two pounds a week at

present, but he expects bein' raised afore lung."

"Well, yo' shall ha' yo'r potittos when he gets his rise. Goo on Jinny, an' keep thi back up, owd lass! Happen thi looad 'll be leeter

soon."

He hadno' driven above a yard or two furr when he heard a woman sheautin' at a window. This woman coome eaut beaut cap, an' wi' a

yead as roogh as a mop, an' hoo browt an owd basket wi' her ut had a

hole i'th' bottom, an' had lost one o' its hondles.

"Let me have a score o' potittos, win yo'?" hoo said, "an' aw'll gi'

yo' fourpence to'ard 'em neaw, an' t' other aw'll pay yo' o'th'

reckonin' day."

"Let's see, yo'r men works at th' Hillock, doesno' he?" th' chap

said.

"Yigh, yo' known him; Smo' Cop, they coen him."

"Aw reckon he gets middlin' o' wage."

"Aye, but what will it do amung eight on us?" th' woman said. "We're goin' to send eaur Joe a-piecin' next week, an' that'll mak'

things betther for us, aw dunno' like this gooin' o' trust, as we

han to pay sometime if we're honest."

"Well," th' men said, "yo' shall ha' yo'r potittos if yo'n gi' me th'

fourpence." So he weighed 'em eaut, an' spit on th' brass, an'

sheauted—"Sowd agen, an' th' money drawn! as th' quack doctor said,

when someb'dy had paid him a bad shillin' for a box o' putty pills. Pike thi road, Jenny!"

He drove on, an' sheauted! till he thowt nob'dy wur havin' nowt to

do wi' him ony moore. At last he felt a pluck at his jacket laps; so

he turned reaund for t' see what wur up. It wur a little lad wi' a

check napkin i' one hont, an' a quart o' fayberry (gooseberries) in

a can i' t'other.

"Well, what does theau want, mi little apple face?" th' chap said.

"Mi mother wants to know if yo' sell'n fayberry," th' lad said.

"Nawe, aw dunno' mi lad. What does hoo want to know that for when

theau's getten some?"

"Well," th' lad said, "if yo'n let her ha' five peaund o' pottitos

hoo'll gi' these fayberry for 'em, an' then yo' con start o' sellin'. They'n come'n eaut o' eaur garden. Hoo has no brass nobbut twopence,

an' that hoo'll want for bacon."

"Aw dunno know, lad, what aw mun do wi' th' fayberry," th' chap

said. "A quart wouldno' be sich a good start."

"Well, mi mother says if yo' dunno' want th' fayberry, win yo' let

her ha' th' pottitos o' trust, an' if mi feyther doesno' pay for 'em

when he's deawnt (finished his work), yo' mun tak' it eaut on him th'

fust time yo' leeten on him at th' 'Owd Bell'?" an' th' lad looked

at th' fayberry as if he could like t' ha' etten 'em hissel'.

"Let's see, whoa is thi feyther?"

"Billy o' Tummy's."

"Oh, aye, to be sure. He wayves to owd Aaron, doesno' he?"

"Yigh, an' mi mother wayves chep trip [1] to

Sloper's."

"Does theau like fayberry?"

"Aye, but they gi'en me th' bally wartch if aw ate too mony!"

"Could t' ate o they' is i' that can?"

"Eaur Alick an' me could."

"Howd thi napkin," an' th' chap weighed eaut five peaund o' pottitos,

an' towd th' lad to tak' faberry back; an' if his mother wanted five

peaund moore i'th' mornin' after hoo could have 'em.

"Noane o' thi capers, Jenny!"

Well, he begun a-dooin' his business o' this plan straight forrad,

an' bi th' time he'd getten to the yate, he'd emptied a hamper an'

started ov a fresh un.

Ther' wur some ov a row when he'd gone! Th' quality end o'th' fowt

wur up i' arms agen t'other, an' aw thowt they'd be noses brasted

an' yure poo'd up bi th' roots afore they'd sattled the'r bother. Th'

day after things wur quite as bad, an' when Setterday coome they

sich a hullaballoo as aw never yerd afore, for booath men an' women

wur at it. My owd Rib kept i'th' heause, like a woman ut has a bit

o' dacency abeaut her, an' aw said hoo desarved a wooden medal for

it, an' aw'd mak' her one eaut ov a bobbin yead. But when Setterday

neet coome, an' things had quietened deawn a bit, Shoiny Jim's wife

coome for her an' said hoo're wanted at the'r heause very partikilar. Aw didno' like thowts on her gooin', but when Jim's wife said it wur

o i' friendship, aw said hoo met goo, an' if hoo coome back wi'

flyin' colours hoo should have a tin medal.

Well, hoo went to Shoiny Jim's, an' fund th' heause full o' quality

folk--th' women fo'in eaut wi' the'r husbants, an' th' husbants neaw

an' then givin' 'em a word back ut hit 'em like hommers! Hoo could

see in a minute what hoo're wanted for, so hoo kept her appron lapt reaund her, an' put her yure eaut o'th' seet, lest what hoo said ud

leead to a scrimmage.

"Neaw then, Sarah," Shoiny Jim's wife said—hoo aulus coes my owd rib

Sarah—"Aw want to see what theau'd do if theau're i' my place. Eaur

Jim here wur on th' spree two days last week, an' he's nobbut browt

me one pound twelve for t' do everythin' wi. Aw want to know what theau'd do with it, Sarah?"

"Aw dunno' know," eaur Sal said; "wayvers' wives hanno' bin used to

nowt o'th' soart."

"Yer thi, theau wastrel!" Jim's wife said, turnin' to her husbant,

ut looked as sheepish i'th' nook as if he'd bin drinkin' a whul

week, "hoo doesno' know what hoo'd do wi' it, an' a wayver's wife,

too!"

"Dost meean t' say theau doesno' know what theau'd do wi' one peaund

twelve a-week?" Shoiny Jim said to my wife.

"Nawe," th' owd lass said, "but aw happen met larn; but just neaw if

yo'd tak' twenty off, an' leeave me th' odd twelve, aw should happen

know what to do wi' that."

Well, they o stare't one ut another, an' aw dar'say some on 'em

thowt eaur Sal wur lyin', but th' owd stockin'- mender never

flinched fro' what hoo said. Hoo'd ha' parted wi' her yure fust.

"Twelve shillin' a-week! " Shoiny Jim's wife said.

"Twelve shillin' a-week!" Smoot Dody's wife said. "Heawever could

hoo mak' that do?"

"Aw conno' tell," my owd Rib said. "But aw've had to mak' it do

mony a time, an' sometimes less, when we'n bin waitin' o' wark. Ther's nob'dy con tell what they con do, nor what they con bear,

till they're put to it. God knows aw could ha' done wi' moore if

aw'd had it!"

Oh, but they couldno' see it. Hoo met give 'em an inklin' heaw it wur done.

"Well, for a start," th' owd skoo-missis begun "Aw dunno'

goo a tae

drinkin' ov a Monday, an' gooin' agen o' Tuesday a-talkin' abeaut

it. Aw have to mind mi wheel, an' ther's a savin' there. Aw dunno'

goo to th' 'Owd Bell' bar five or six times a-day for t' see what

time it is, when aw've a good clock awhoam. Eaur table doesno' know

what potted shrimps, an' salmon steaks, an' marmalade, an' lobsters

are. Aw believe if owt o'th' soart wur put on it, it ud break deawn. We hanno' lamb an' green peas for dinner every day. But mind what aw

say neaw, ut yo' winno' misunderstood me. It isno' becose worchin

folk should be begrudged, or should go short o' sich things, becose

aw think ut if onybody desarves good mayte an' drink it's thoose ut

wortchen for it. But twelve shillin' a week winno' afford it, unless

ther's beef at threehaupence a peaund, an' other things as chep i'

proportion."

"Well done, Sarah!" th' men sheauted; but they changt the'r tune

afore hoo'd done.

"Aw never cook moore nur we con ate," th' owd ticket went on, "so ther's nowt wasted. Aw do mi own weshin', as every wife owt to do,

if hoo's able, whether hoo be gentle or simple. Aw believe eaur Ab 'ud

go as ittert (dirty) as owd Will Kneet afore he'd wear a shirt o' onybody's weshin' beside mine. (True, owd wench; aw itch wi' thowts

on't neaw!) Aw do mi own cleeanin', but that's no mich, becose eaur

heause is nobbut a little un. Aw dunno' goo strollopin' abeaut i'

silk an' satin a day or two a week, as if aw're Lady Mary, an' then

to'ard Thursday, borrow someb'dy's ring for t' tak' to mi uncle's

an' aw dunno'—"

Hoo could get no furr, for o'th' chaps jumpt up at once, an' as

sudden as if they'd bin scauden; an' o'th' women obbut my owd rib

put the'r honds under the'r approns, an' looked as if they'rn just

bin drawn up afore th' magistrate. Ther' wurno' a ring i'th' heause,

nobbut one aw'd gan two canaries for, an' that wur on eaur Sal's

finger. Th' approns wur turned up in a snifter, an' when ther' nowt

breeter nur a finger nail could be seen, ther' wur a dooment!

Fists flew abeaut, an' threat'nin's wur made wi' sich vengeance ut

made my wife wish hoo're at side o'th' owd yate agen, for hoo thowt

ther'd be some black e'en 'liver' eaut. But it didno' come to that. Th' women promised they'd be everythin' ut wur reet an' good if th'

men ud be th' same, an' they'd try to do the'r best. Th' storm

passed off, an' th' sunshine coome eaut agen, an' aw're sent for,

just to ha' a word amung 'em. Aw backed mi owd rib up as if hoo'd

bin a tip-top race hoss, an' a rare spree we had. We'd just an odd

quart o' spigot milk as a gradely sattler. Aw sung 'em "Jove o'

Grinfilt," an' we'rn as merry as a lot o' gipsies till midneet, when

we parted.

Walmsley Fowt has bin different ever sin'. Booath men an' women are

tryin' ther' best, an' things are lookin' betther every day. Th'

pottito chap coes neaw at every dur; an' his donkey has getten so

fat, it think it's a hoss, for it draws as soon as it's towd, an'

has gan o'er singin' "another wayver deead" [2] at

th' side o'th' yate.

Ther's no wipin' o' lips nor borrowin' o' rings, neaw! Aw noticed

one day ut "mi uncles," as they coed him, ut had a shop wi' three

brass oranges o'er his dur deawn i' Hazlewo'th, had put his shutters

up, an' takken his three-legged sign deawn, an' ther an ettercrop

(spider) th' size ov a starfish wayin a bed-tick o one side o'th'

dur hole. An' one neet when aw went i'th' "Owd Bell" kitchen aw

hardly knew wheere aw wur, summat looked so strange to me. Aw

believe aw should ne'er ha' fund it eaut if th' londlady hadno'

com'n in, an' said—

"We'n managed it at last, Ab!"

"Managed what?" aw said.

"We'n getten th' kitchen dur painted!"

That wur it ut made th' place look so strange to me.

Neaw aw've bin thinkin' if things han bin gooin' wrung i' Walmsley

Fowt, heaw are they gooin' on i' bigger fowts, an' amung bigger

folks? It's o very weel praichin to workin' folk abeaut bein'

extravagant, an' sich like, but are eaur nobs dooin' betther? Aw rayther think ut i'tead o' dooin' that, they're spendin' the'r

theausands o' nowt but fiddle-faddle, while a lot o' poor craythers

are clemmin'. Is no' it a shawm? Nay, aw'll go furr—is no' it a sin

before God o Meety? Let 'em wipe the'r scores off o' every soart, so

ut when fine weather comes owd England's kitchen dur con be new

painted!

1. Chep trip, the name given by

weavers to a very poor quality of material, for the weaving of which

they only received about five shillings for fifty yards.

2. It used to be a very common occurrence for

Lancashire people in the country districts, on hearing a Donkey

bray, to exclaim "Yer thi! another wayver deead!"

――――♦――――

CATCHIN' A WEASEL.

JIM

THURSTON coome runnin'

across th' fowt t'other mornin', wi' his yure blowin' up on his yead,

an' his e'en lookin' as wild as if he'd seen a boggart.

"Ab! " he said, wyndily, "does theau know owt abeaut nattural

history?"

"Animals or yarbs?" aw axt him.

"Oh, animals, what else?" he said. "What han yarbs to do wi'

nattural history?"

"Well," aw said, "aw con tell a rottan (rat) fro' a ring-tailed

monkey, if they wur to put one aside o' t'other."

"Did theau ever see a weasel?"

"Aw have," aw said.

"An' a foomart?"

"Aw've seen booath," aw said.

"Are they owt like one another?"

"One's abeaut as mich like t'other as a kittlin' is to a cat," aw

said. "A weasel's red-breawn, an' a foomart's breawn-black."

"Well, aw've catcht oather one or t'other," Jim said "but which it

is, aw conno' tell, becose it's noather a breawn-black nor a red-breawn;

an' if aw'm not mista'en, it's bigger nur a weasel, an' less nur a

foomart."

"Theau's th' deuce as like!" aw said, an' aw laid mi pickin'-peg

deawn.

"Yoi; aw have it caged under a firkin-tub i'th' kitchen yonder," he

said. "But eaur Peggy says it's raised sich a smell hoo wants me t'

turn it eaut agen."

"Well," aw said, "aw hanno' yerd o' sich a thing bein' seen abeaut

here this mony a year. Could one manage to get a peep at this

animal, dost think?"

"Just come across," he said.

Aw didno' need twice axin', but shuttert off my loom at once, an' we

slipped across th' fowt, an' into owd Thuston's kitchen, wheere aw

seed th' firkin tub stondin' i'th' middle o'th' floor.

"If theau koiks th' tub o' one side, beaut ther's summat put i'th'

front," aw said to Jim, "th' foomart, or whatever it is, 'll get

eaut. Wi should ha' had a wire net!"

"Heaw would a riddle do?" Jim said, an' one side ov his face

puckered up, as if he could hardly howd fro' laafin'.

"That ud be too mich like eawl catchin'," aw said, an' a glimmer ov

a misgivin' shot through mi yead ut lookin' at a foomart ud turn

eaut to be summat like catchin' a eawl. Then aw yerd a noise like

scrattin' at th' tub ut put these thowts o' one side agen.

"Yer thi, heaw it's scrattin'!" Jim said, gettin' howd o'th' tub

an' just raisin' it. "Another inch an' theau met see it nose." Then

he flopped th' tub deawn agen as if he'd bin bitten!

"What's do wi' thi neaw?" aw said. "It hasno' bitten thi through th'

leggins, has it?"

"Look for weasel then."

"Oh, that smell!" he said, takkin' howd ov a hondful ov his nose an'

givin' it a screw reaund. "Does theau smell nowt?"

"Aw do smell a bit o' summat neaw," aw said. "Aw think it'll turn eaut to be a foomart bi that." Then aw clapt mi een on a

spindle-backed cheear ut stood in a corner o'th' kitchen. "Just the

very thing," aw said. "Aw'll clap that cheear back i'th' front o'th'

tub, so ut when theau lifts it up it'll be like a cage front. Dostno'

see?"

"Aw didno' think o' that," Jim said. "Theau'rt a good skamer, Ab! Aw dunno' know what we should do i' Walmsley Fowt if it wurno' for

thee. Deawn wi' thi timber!"

Well, aw gees this cheear an' laid it deawn aside o'th' tub, an'

held it tight to it. Then they another scrattin' noise, an' while

that wur gooin' on Jim koiked th' tub o one side, an' axt me if aw

could see owt. Aw couldno' while aw stood up, so aw deawn o' mi

knees an' peeped through th' cage, but if aw'd looked till neaw, aw

should ha' seen nowt. So aw begun o' keawntin' th' almanack, an'

fund ut th' day before that wur th' thirty-fust o' March!

"Thea may put th' tub deawn agen," aw said; "aw'm satisfied—it's a

weasel."

"Theau thinks it is?" Jim said, wi' a grin on his face ut ud ha'

done for a aleheause sign.

"Aye, it's a weasel," aw said. "Aw've just bethowt mi ut foomarts are

never seen after th' last o' March; an' this is th' fust ov April,

isno' it?"

He oppent a meauth as wide as a soof, an' settin' up a rooar like a

bull, said—

"April foo'!"

"Jim," aw said, "thi feyther used to say, when he're talkin' abeaut

thee, ut theau hadno' wit enoogh to poo thi finger eaut o'th' foire

if someb'dy put it in. He's a wise feyther ut knows his own son. Thine ne'er fund thee yet. If theau lives till theau'rt eighty

theau'll be a philosipher—theau will, Jim."

"Sam Smithies couldno' ha' sowd thee betther," Jim said, oppenin'

his face agen.

"That's true, Jim, he couldno'," aw said. "Theau's done th' job as

cleean as ony men could do. But aw'll tell thi what—aw'm no goin'

to be th' odd foo'. Aw dunno' care for havin' o th' honour to misel'. Someb'dy else mun share it, or else aw'll lose a day's wark."

"Well, whoa is they' we con try it on wi'?" Jim said, runnin' th'

fowt directory o'er in his mind.

"Theau mun ha' thowt aw're th' biggest yorney i'th' fowt, or else

theau wouldno' ha' come'n to me th' fust," aw said. "Theau'll be a

philosipher yet, Mesthur James. Thy feyther made a mistake when he

put thee to farmin'."

"Well," Jim said, in a way for t' piece things up, as he thowt,

"what made me come to thee th' fust wur this: aw calkilated ut if aw

could sell thee aw could sell o'th' fowt after. Doesno' see?"

"Very good; but th' clooas winno' fit this time," aw said.

"Heawever,

we mun collar another foo' before th' chiller getten t' yer. What

dost' say to tryin' Fause Juddie on?"

"Just the very chap." Jim said, slappin' his knees, an' settin' up a

yeawl. "Nob'dy betther. Eh, what a do we con have if he'll tak' th'

bait gradely! Ab, theau could get him t' swallow th' hook betther

nur aw could."

"Aw dunno' know that," aw said. "Theau's catcht one fish very smartly

an' met lond another. But never mind, aw'll lay in for Juddie. Thee

goo, an' look after th' shippon, an' keep thi meauth as close as if

theau'd a shillin' in it, while aw goo an' bait mi hook."

Wi' that we parted, Jim gooin' abeaut his wark, an' me settin eaut a

foo'-huntin' as if it wur a prime bit o' business. Aw slung mi

timber across th' fowt, an' crept under th' window, so ut eaur Sal

couldno' see me, an' think aw're gone deawn to th' "Owd Bell." Then

aw slipt reaund th' end o'th' heause, an' into owd Juddie's shop,

wheere aw fund th' owd lad agate o' cobblin' up a pair o' weighs, ut

he said would keep givin' o'er-weight, chus what he did at 'em.

"Aw believe yo'n a book upo' nattural history?" aw said.