|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER XXXVI

'TYRANNICIDE'

THE burden of the crimes of the Second Empire did

not fall on France alone. Italy also shared that burden. It

was, however, before he had waded through blood to a throne that Louis

Napoleon had begun the treason against Rome. When the Republic was

proclaimed in the Eternal City, he despatched General Oudinot with a

fratricidal expedition to Civita Vecchia, solemnly declaring it was not

his object to "force upon the State a government contrary to the will of

the people." This was in April, 1849. "Three months after,"

says Mazzini, "Rome, her Government, the will of her people, were

inexorably crushed." The heroic defence of Garibaldi failed; the

bombarded city surrendered; the Triumvirs, Mazzini the chief, wandered

about the streets dazed till friendly advisers found them shelter and

safety; Garibaldi himself, after incredible hardships, during which he

lost his beloved Anita, escaped to the coast and thence into exile.

From that time for many years forward the throne of the Holy Father was

poised on the points of French bayonets. Hope there was none for

Italy as long as France, misled by the man who had mastered her, remained

at the head of the coalition of enemies. Every Italian knew

this—nobody better than a Roman citizen who had valiantly fought against

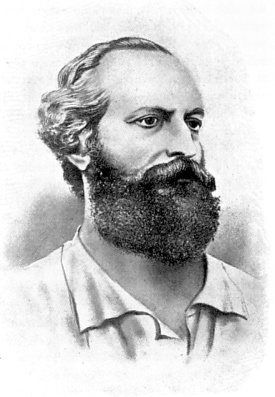

fearful odds in the defence of his home, Felice Orsini.

|

|

|

Felice Orsini

(1819-58) |

The patriotic spirit of Italy, during all the dreadful,

dreary years that followed the occupation of Rome, was kept alive by

fervent appeals from Mazzini, by schemes which he organized, by revolts

and risings which he inspired and in which he shared. But Orsini was

impatient of Mazzini's policy. He had taken part in many of the

daring adventures and struggles of his time. He had made a

marvellous escape from the fortress of Mantua. The story of that

escape, told by himself in a little volume, was as widely read in England

as the earlier story of Silvio Pellico's imprisonment in the fortress of

Spielburg. Coming to this country, he had lectured here and there on

the cause of Italy and his own sufferings in connection therewith.

Also he had written and published a book of Memoirs. His earnest

faith, his intense patriotism, his absorbing passion—all centred in his

beloved Italy—made for him friends and admirers in England. But he

longed for some speedier and more certain results than any that had yet

followed the efforts of the revolutionary party. Writing in 1855

from his dungeon in Mantua, he declared his distrust of the old

methods—conspiracies, outbreaks, insurrections. Again, in his

Memoirs, published in 1857, he wrote:—"Italy finds herself at the present

moment in the most deplorable condition that can be imagined. This

state of things, however, will not last long, because all depends upon

Napoleon, and this man will not be tolerated long, with his government

based on despotism and treason." It would seem that Orsini was even

then contemplating the movement which a year later startled all Europe—a

movement which was to employ for the salvation of Italy the very methods

which had been employed in 1851, but with infinitely more awful

accompaniments, for the subjugation of France.

It came to pass on the night of Jan. 14th, 1858, that Louis

Napoleon was returning from the opera. Bombs burst under his

carriage, spread terror and destruction all around, but failed to do more

than affright the intended victim. The explosions—clumsy,

ineffective, fatal to many innocent people—were the work of Orsini and

his accomplices. It was thus that he hoped to rid Italy of the one

man who made her redemption impossible. The attempt failed in

everything except in arousing the conventional indignation of Europe.

Orsini, who had staked his life on the hazard of a desperate venture,

resigned himself to his fate. He died, as Mazzini a few months later

counselled Louis Napoleon to die, "collected and resigned."

|

|

|

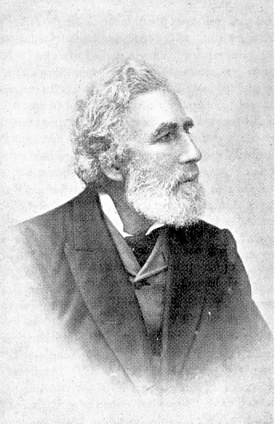

Louis Napoleon

(1808-73) |

Throughout England there was one long howl of execration.

The newspapers forgot the provocation—forgot the bombardment of Rome, the

maintenance of the subjugation of Italy—forgot the crime of Dec. 2nd,

which had begot the crime of Jan. 14th—forgot their own bitter

imprecations of the author of the parent crime. [22]

Orsini, from one end of the land to the other, was denounced as a vulgar

assassin. Every epithet of abhorrence was heaped upon his name.

It seemed to be thought that there was absolutely no difference between

him and the vilest ruffian that had ended his days in Newgate.

But surely there was another side to the picture. Would

not somebody take cognisance of the cause of the attempt, of the motive

that impelled it, of those not very distant events which had generated in

an otherwise high-souled man a fierce and implacable passion? The

question presented itself to some of us. It presented itself to me.

I prepared a paper which was in some measure a protest against the

universal chorus of condemnation, and at the same time an attempt to

explain some of the ethical points involved in the catastrophe. The

production was juvenile enough; but it did at any rate show that the event

which had so excited and enraged the Press had really another aspect than

that alone which the exponents of public opinion were content to

recognise.

The manuscript was offered in the first place to George Jacob

Holyoake, then a publisher in Fleet Street. Mr. Holyoake declined

the offer, for one reason, I understood him to say, because he was already

in treaty with Mazzini for a pamphlet on that very subject. "Very

well," I said, "if Mazzini or anybody else will raise a voice against the

pitiful clamour of the day, especially the beatification of Orsini's

intended victim, I will pitch my own little screeching behind the fire."

The pamphlet which Mr. Holyoake had in his mind was probably that terrific

indictment of Louis Napoleon, one of the classics of the Revolution, which

was published a few months later by Effingham Wilson. If Mazzini's

letter, which must have made even imperial villainy squirm, had appeared

earlier, this chapter would not have been written. But, like Orsini,

I was impatient: so the manuscript was offered to Edward Truelove at

Temple Bar. It was the beginning of a life-long friendship.

Mr. Truelove was pleased with the piece that was submitted to him—almost

as pleased, I think, as the young author himself. Yes, he would get

it printed at once. But he had two suggestions to make. One

was that the title of the pamphlet should read—"Tyrannicide: Is it

justifiable?" The other related to a name or nom de-plume for

the title-page. The manuscript was anonymous: it was intended to be

anonymous. "The name," I said, "is nothing, the argument everything.

The argument can stand by itself: the authority for it will add nothing to

its weight, particularly an unknown authority." Mr. Truelove then

suggested a nom-de-plume. "Well," I said, "if there is to be

a name, it shall be my own." So the thing went forth. But

nobody believed the name to be other than fictitious. The pamphlet

was said to be the work of a French exile. I was told myself that

Louis Blanc was the author. Even workmen in the office who knew me

and knew my name, when discussing the pamphlet and the prosecution, did

not associate me with the authorship. It remained an open mystery to

the end. [23]

|

|

|

Edward Truelove

(1809-99) |

The police of the Metropolis were vigilant in those days.

It is likely that they acted under orders; for despatches had already been

received from the French Government. Anyway, the pamphlet had not

been on sale for more than a few hours before an inspector of police

invited Mr. Truelove to accompany him to Bow Street. The invitation

was so imperative that he was not allowed to do more than change one coat

for another. That day I was taking my usual walk with a fellow

compositor during the dinner hour towards the Strand. We had passed

the book-shop at Temple Bar. Suddenly I was clutched by the arm.

"Come, I want you: Truelove has been arrested." The person who spoke

was urgent and excited. It was the wife of the publisher—a refined

and accomplished lady, herself devoted to advanced ideas. I was

enjoying a smoke at the time, but my pipe was effectually put out for the

rest of the day. I went into the book-shop. There I learnt

what had happened. I, the cause of the trouble, the real offender in

the case, was ready to become a substitute for the publisher. What

else could a poor compositor do? But this, I was told, would make

two victims instead of one. Besides, the police, believing that I

was a myth, had no warrant against me. Mr. Truelove remained in

durance—only a few hours—till sufficiently substantial friends could be

found to go bail for his appearance before the magistrate next morning.

The result of the proceedings at Bow Street was a foregone

conclusion. Mr. Truelove was committed for trial. The charge

against him was that of having "unlawfully written and published a false,

malicious, scandalous, and seditious libel of and concerning his Majesty

the Emperor of the French, with the view to incite divers persons to

assassinate his said Majesty." The charge itself was a false and

scandalous libel. First of all, there was not the smallest intention

on the part of author or publisher to incite anybody to do any thing.

Nor was there any incitement either, except such as may arise from

indignation at the recital of past crimes. As for libel, the

pamphlet could have been voted libellous only on the old doctrine "the

greater the truth, the greater the libel." The pamphlet, it is true,

pointed out that the outrages of tyrants and usurpers are apt to inspire

desperate men, and even sensitive and judicious men, to attempt the

vindication of their country's rights and honour. If an adventurer

violated his oath, dragged the foremost men of the country from their

beds, cast the representatives of the people into dungeons, suppressed and

dispersed the courts of justice, slaughtered thousands of unarmed people

in the streets, shipped without charge and without trial tens of thousands

of innocent citizens to a penal and pestiferous colony, made himself by

these and other foul and infamous means the master and oppressor of the

people—was he therefore to be absolved from the consequences of his

villainies? This was the question that was asked. A writer in

the Times—the author of the "Letters of an Englishman," understood

at the time to be Mrs. Grote, the wife of the historian of Greece—had

declared that "a man who sets himself above the law invites a punishment

beyond the law." The doctrine proclaimed by Mrs. Grote after the

Coup d'Etat was merely reasserted after the attempt of Orsini. But

no name was mentioned in the pamphlet. All the same, said Mr.

Bodkin, who prosecuted for the Crown, there could be no doubt as to the

person meant. The description could apply only to his Majesty the

Emperor of the French. The cap fitted him exactly. Where,

then, was the falsehood? Mr. Truelove, however, was committed to

take his trial before the Queen's Bench.

CHAPTER XXXVII

"A LAME AND IMPOTENT CONCLUSION"

THE prosecution of Edward Truelove was seen at once

to be an attack on the liberty of public discussion. As such it was

resented by most of the

leading Radicals of the day. The prosecution was all the more resented

because it had clearly been commenced at the instigation of a foreign

Government and to appease a foreign despot. A Committee of Defence was

formed; a fund was opened for defraying the expenses of the trial; and

local committees in the provinces busied themselves in collecting

subscriptions. John Stuart Mill contributed £20 to the Defence Fund. Among

the other

contributors were Harriet Martineau, Professor F. W. Newman, W. J. Fox,

Joseph Cowen, James Stansfeld, P. A. Taylor, Dr. Epps, Abel Heywood,

Edmond Beales, besides many more whose names, though forgotten now, were

well known and even famous at the time. Charles Bradlaugh was

appointed secretary to the committee, and James Watson accepted the office of treasurer. The duties of the committee were

afterwards increased by a second press prosecution—the prosecution of a

Polish

bookseller in Rupert Street for publishing a pamphlet by three French

exiles, Felix Pyat, Besson, and Alfred Talandier. It may be mentioned, as

indicating

the bitter spirit of the day, that the Times, which had seven years before

printed diatribes as fierce as any in the two pamphlets, refused to

advertise the

appeal of the committee for subscriptions. Though the press was hostile,

however, the public was not unfriendly; for the announcement that Henry

J.

Slack, eminent in later years as a microscopist, was going to deliver a

lecture on the subject of the prosecutions, drew together a crowded and

enthusiastic audience at St. Martin's Hall. Professor Newman saw more

clearly than most people, not only the real character of the English

pamphlet, but the consequences that would follow the success of the

Government attempt to punish its publisher. "The question," he wrote, "is not

whether Mr. Adams's doctrine is right or wrong, but whether, as an

Englishman addressing Englishmen, he has a right to advocate it. Substantially he

protests against the confused application of the word 'assassination,'

similar to the confused application of the word 'murder' to all deeds of

battle. It is

permissible for a free citizen to argue

even against the law under which a felon has been condemned. If Mr. Adams

may not endeavour to convince us that Orsini's deed, though punishable and

punished at law, is not morally wrong, I do not see how Englishmen can

retain the right of censuring the law at all. Free moral criticism is

effectually

stopped." As for the doctrine of tyrannicide, the sentiment embodied in

that doctrine, said Professor Newman, "is that which for ages

predominated among

Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans, the three nations which have been the chief

feeders of our moral and intellectual life." "If," he added, "we have

now

outgrown certain sentiments and judgments of those three nations, it is

rather too much to prosecute, or rather persecute, those who hold to the

old

opinion that lynch law against a treasonable usurper is better than no law

at all."

The classical and scriptural doctrine against which so great a hubbub was

raised in 1858 had not, however, lost favour even among modern statesmen

and poets. Many examples were cited when the subject was of public

interest. Two or three may be cited here. Walter Savage Landor was

almost fanatical in his pronouncements. "I have," he wrote to the Marquis d'Azeglio,

"never dissembled my opinion that tyrannicide is the highest of virtues,

assassination the basest of crimes." Mr. Disraeli had published in

1834. his "Revolutionary Epic," wherein occurred the well-known lines:—

|

And blessed be the hand that dares to wave

The regicidal steel that shall

redeem

A nation's sorrow with a tyrant's blood. |

But only fourteen days before Orsini's attempt a poem of Matthew Arnold's

on an incident in Greek history had appeared. And this is what the

poet wrote:—

|

Murder! but what is murder? When a wretch

For private gain or hatred

takes a life,

We call it murder, crush him, brand his name.

But when, for some great

public cause, an arm

Is, without love or hate, austerely raised

Against a

Power

exempt from common checks,

Dangerous to all and in no way but this

To be annulled—ranks any man an act

Like this with murder?

|

Quite as truly could the charge of incitement have been preferred against

Matthew Arnold as against the author of the "Tyrannicide " pamphlet.

The prosecution—hateful to the people because it had been instituted at

the instance of a Government whose origin and practices were alike

odious—was

fatal to the Ministry which undertook it. Lord Palmerston, only a few

months before the Orsini affair, had swept the constituencies. Bright,

Cobden, and

Milner Gibson all lost their seats. Ministers had a stronger majority than

any previous

Ministry for many years. But they truckled to a foreign Power, and they

went speedily to pieces. The fate of Lord Palmerston's Government is an

object

lesson in English politics. Although the Prime Minister had as Foreign

Secretary exhibited indecent haste in recognising the Government of Dec.

2nd, the

favour he had shown it was not reciprocated seven years later. Following

the Orsini attempt there came despatches from Count Walewski, Minister of

Foreign Affairs to Louis Napoleon, that were almost insolent in tone. England was charged with harbouring murderers, and was practically

commanded to

restrict her own liberties for the protection of the French Emperor. And

swashbucklers of the French army demanded to be led against what they

called a

"den of assassins." It was under the pressure of these insults and menaces

that the Government of Lord Palmerston ordered the prosecution of Dr.

Bernard, commenced proceedings against the publishers, and even had the

supreme folly to attempt a revision of English laws. So much subserviency

could not be tolerated. When the Conspiracy Bill—otherwise popularly

known as the French Colonels' Bill—came up for consideration, an

amendment proposed by Mr. Milner Gibson, who had returned to Parliament

for a new constituency, shattered to pieces

one of the most powerful Ministries of the century. Lord Palmerston, as a

consequence, surrendered the seals of office to Lord Derby.

The new Government did not abandon the prosecutions; but it showed an

evident reluctance to press them; and it eventually succeeded, with the

aid of

an unprincipled counsel, in finding a way out of the difficulty. The

prosecution of Mr. Truelove commenced in February; but the lame and

impotent

conclusion of the affair was not reached till the end of July. Meantime,

there had been informal negotiations between the Committee of Defence and

the

Law Officers of the Crown. It was intimated to the Government at the

outset that the author was ready to surrender himself, provided the

proceedings

against the publisher were withdrawn. But the offer was declined. This was

in February. Three months later the author committed a grave indiscretion:

he got married. It was one of the best day's work he ever did, though he

saw afterwards that it would have been more prudent to wait till the

so-called

libel business was settled. During the time he was taking a brief holiday

in the Isle of Wight, wandering from Ryde to Brading, from Brading to

Ventnor,

from Ventnor to Newport, from Newport to Ryde again, with no postal

address anywhere, an important change occurred in the legal

situation. The Crown authorities, who had refused the proposal of the

Defence Committee, now offered to accept it. The very night the author

returned

from his short honeymoon he attended a meeting which was called to decide

whether he or his friend Truelove should run the risk of a trial that

might or

might not end in a residence of six or twelve months in one of her

Majesty's gaols. Of course he placed himself unreservedly in the hands of

the

committee. That body, however, seeing in the overtures of the Government

clear evidence of weakness in the prosecution, declined to help the legal

advisers of the Crown out of the quagmire. Preparations were therefore

made for the coming trial.

It was the desire of the defence that a question which involved a distinct

violation of the liberty of the Press should be fought out before a

British jury.

Eminent counsel were retained. Mr. Edwin James had at that time achieved

considerable popularity by an impassioned address he had delivered at

the Old Bailey on behalf of Dr. Bernard. It was supposed, too, that he had

every prospect of rising from office to office till he finally reached the

Woolsack.

But he must even then have begun to disclose to keen observers those

faults of character which wrecked his career. Dickens, after a single

sitting, as Edmund Yates records, drew his portrait as Mr. Stryver in "A

Tale of Two Cities." Soon after the inglorious conclusion of the Truelove

trial, he

found it necessary to take flight to New York, where he made a further

mess of his life. But these things had not happened when Edwin James was

thought

to be the best man at the Bar to conduct a great trial. The selection

turned out to be a blunder. We were all expecting a new vindication of the

right of public

discussion. What we did not know was that intrigues were in progress to

defeat the desired object; that the man who had been chosen to lead the

defence was going to betray it.

The trial was finally fixed for June 22, 1858. It was to take place in

Westminster Hall before Lord Chief Justice Campbell and a special jury. The prosecution

was to be conducted by the Attorney-General (Sir Fitzroy Kelly), Mr.

Macauley, Mr. Bodkin, and Mr. Clarke, while associated with Mr. James for

the defence

were Mr. Hawkins, Mr. Simon, and Mr. Sleigh. I was working late, as usual,

the night before. Mr. Truelove came to me in a state of great indignation

and

excitement. He had just been informed that the case was to be compromised. Edwin James, without consulting the defendant or the defendant's friends,

had settled

the matter with the Law Officers of the Crown. It was never known what was

the consideration. All that was known was that cause and client had both

been sold. But, I said, could not new counsel be retained? No, it was too

late. Well, then, could not one of the juniors act for us? No, it was

contrary to the

etiquette of the Bar. So a pregnant opportunity was lost. The rights of a

British subject, the rights of the public itself, had been sacrificed to

satisfy the

conveniences of the Government. Then came the farce at Westminster Hall. Sir Fitzroy Kelly solemnly informed the court that the indictment would

not

be tried; that he understood his learned friend was prepared on behalf of

his client, who was "a respectable tradesman, and the father of a large

family,"

etc., etc. And then Mr. James solemnly disavowed that either the writer or

the publisher of the pamphlet had any intention to incite, etc.; that Mr.

Truelove,

believing, etc., had agreed to discontinue the sale of the pamphlet; and

that he trusted, etc. And then Lord Campbell solemnly told the jury that

it was

satisfactory to know, etc.; that the pamphlet was such, etc., that he

should have said if the trial had proceeded, etc.; that the defendant had

acted with the

utmost propriety in the course he had taken, etc. And then the jury

solemnly returned a verdict of not guilty. And so the solemn farce ended.

The prosecution was begun by Sir Richard Bethell under the Government of

Lord Palmerston, and was abandoned by Sir Fitzroy Kelly under the

Government of Lord Derby. It would probably not have been begun at all if

a less subservient Minister had been in office. As it was, Lord Derby and

his

colleagues were no doubt greatly relieved when they found that they had to

deal with so obliging a gentleman as Edwin James. But the mischief did not

end

there; for the very changes in the law which were defeated in 1858 were

effected at a later date without anybody seeming to know much about it. Thus

was the liberty of discussion restricted. And thus did it become perilous

to show that the slaughter of Garibaldians at Mentana was simply another

challenge to tyrannicides. It was on this occasion that Du Faillu,

reporting to the French Government how Italian patriots had been mown down

in swathes,

exultantly exclaimed: "The Chassepot has done wonders!" An indignant

protest, warning the perpetrator of the outrage of the

consequence of his misdeeds, though printed and prepared for publication,

had to be suppressed [Ed.--see 'Bonaparte's

Challenge to Tyrannicides']. So were despots and usurpers protected from fitting

condemnation,

while the very danger which Professor Newman had anticipated befell the

country. But an inexorable fate asserted itself at last. Twelve years

later the

despot and usurper who had triumphed on the Boulevards disappeared in

shame and ignominy amidst the blood and smoke of Sedan.

CHAPTER XXXVIII

THE WORKING MEN'S COLLEGE

FACILITIES for the higher education of the people

were far from abundant in the middle of the last century. Even

mechanics' institutes were few and far between. But scant as were these

facilities, it almost seemed that the supply was equal to the demand. The

masses of the community, indeed, were so ignorant that they placed little

or no value on education of any sort. Nor had they grown much more

enlightened

towards the end of the century; for many were the parents—mothers

especially—who, when Mr. Forster's Education Bill had become law,

resented the intrusion of the School Board officer. A few years after that

event, I remember accompanying an antiquarian friend on a visit to some

historic

buildings in the neighbourhood of Tuthill Stairs, Newcastle. We were

surprised to notice the effect of our appearance—women hurrying their

children into

the houses, or hiding them in other ways. When we came to inquire

the cause of the commotion, we were told that we were thought to be

officers of the School Board! It was really among the educated

classes that the necessity for educating the people was first recognised.

Mechanics' institutes and other similar enterprises were thus promoted,

formed, and supported by persons who had no need for the establishments

themselves. Precisely in the same way was that best of all

institutions of the kind—the Working Men's College in London—set on

foot.

The Rev. Frederic Denison Maurice, the founder of the

College, was a distinguished scholar and divine. More than that, he

was a distinguished friend of the people. He had been associated

with Thomas Hughes and Charles Kingsley in what was known as the Christian

Socialist Movement. And he was so much respected and beloved that I

found myself, when any point or problem in the doctrine or practices of

the Church of England struck me as absurd, asking the question: "How,

then, can such things obtain the assent or approval of Mr. Maurice?" The

question settled one difficulty at any rate: that there could be nothing

inherently absurd in the matter, else so good and so able a man would not

preach or conform to it. Yet I knew Mr. Maurice only from seeing and

hearing

him occasionally at our college meetings. It was out of affection for the

people, and especially the working people, that he conceived the idea of

placing in the hands of as many as could reach or appreciate them the

priceless advantages of a collegiate training. The venture was commenced

in 1854 at a house in Red Lion Square, Holborn. After two years'

successful operations there, the council announced in its second report

that a freehold house, No. 45, Great Ormond Street, Bloomsbury, had been

purchased for the further work of the college. The price of the house was

£1,500; of this £500 was contributed by Mr. Maurice, and the rest raised

on mortgage. So was permanency given to an institution which has conferred

infinite benefit on many a struggling student.

The staff of the college—whose services were all voluntary

of course—was probably as brilliant as that attached to any other college

in the kingdom. Mr. Maurice was the principal. Associated with him were

fifty gentlemen, every one of them eminent in art, science, or

scholarship. The scholars were distinguished in the list of teachers by

the degrees they had acquired at the Universities; the others were

described as artists, sculptors, or members of the learned professions. Here are a few of the names:—John Ruskin, Thomas

Hughes, F. J. Furnivall, Llewellyn Davies, Lowes Dickinson, R. B.

Litchfield, J. M. Ludlow, Godfrey Lushington, Vernon Lushington, Alexander

Munro, Dante G. Rossetti, Thomas Woolner, Ford Madox Brown, Frederic

Harrison, Edward Burne Jones. Mr. Ruskin taught a drawing class; Mr. Furnivall

taught classes in grammar and in the structure and derivation of English

words; and the author of "Tom Brown's School Days," still the best book

for boys ever written, besides other work in the college conducted, or

wanted to conduct, so that the physical as well as the intellectual

culture of the student should not be neglected, a boxing class!

Teachers and students—at least one-third of the latter belonged to the

artizan class—constituted a happy family both at Red Lion Square

and at Great Ormond Street; for perfect equality prevailed among all. The

only paid officer connected with the college in my time was, I think, the

secretary; and this office was held by an old Chartist, Thomas Shorter,

whose name I recollected to have seen attached to contributions in Thomas

Cooper's Journal.

My circumstances when I joined the Working Men's College in the autumn of

1855 were not particularly conducive to study. Being, however, in some

sort of settled employment now, the old

longing for better education asserted itself. Wherefore I entered three of

the classes in the college—Latin, English Grammar, and the Structure and

Derivation of Words. But the pursuit of knowledge in my case was

necessarily attended by many difficulties. I find in my old diary

statements of the conditions under which compositors had to earn their

daily bread in the office of a weekly newspaper. An entry for July 12th,

1855, reads thus :—"Worked without intermission for forty hours; slept

for twelve, with many intermissions." Other entries show that long hours

in the middle of the week were the invariable rule. Monday was our only

regular day, and then we worked, or waited for work, from nine o'clock in

the morning till eight o'clock at night. "On Tuesday," the old record

runs, "we begin at eight, nine, or ten o'clock. From that time till the

paper goes to press we work without intermission. Not without

interruption, though, especially on Wednesday morning. Always midnight on

Wednesday, frequently early hours of Thursday morning, before the last

pages are ready for stereotypers. Thus nearly forty hours of continuous

work—standing nearly all the time, for to sit is to fall asleep, and run

the risk of pieing all the matter we may have in our sticks, as has really

happened

several times in my own case." The rest of the week we had little to do,

except distributing our type ready for the next. But the leisure we got in

that way was poor compensation for the excessive toil that preceded it. That excessive toil, moreover, was an indifferent preparation for the

study of languages. All the same, the classes were delightful, though I

had to give up the Latin from sheer inability to rivet the attention.

The English classes were conducted by Mr. Furnivall. Our tutor was a

remarkable man at that date, but he has become a much more remarkable man

since. A quarter of a century later he was considered to have done so much

excellent work in connection with the study of English philology that he

was awarded a pension of £150 a year. It was said at the time that he was

the founder of more literary societies than any man living. The Early

English Text Society, the Chaucer Society, the New Shakspeare Society, the

Society for the Publication of old English Ballads—these are among the

learned bodies which owe their existence to his untiring efforts. And the

list of books he has edited for the various societies forms a most

interesting catalogue of early English literature. Dr. Furnivall's

seventy-sixth birthday fell on Feb. 4th, 1901. The occasion

was celebrated in a unique and appropriate fashion. A year or more

previous fifty of the foremost students and professors of English in

different parts of the world—Germans, Americans, Frenchmen among

them—combined together to do him honour. They presented him with an old

boat—he declined to accept a new one; they persuaded him to sit for his

portrait; and they each contributed to a collection of essays and papers

which, along with a bibliography of Dr. Furnivall's own productions, was

published in a handsome volume by the Clarendon Press on his next

birthday. Dr. Furnivall is not only a scholar, but a good deal of an

athlete—at least he was even after he had entered his sixties. Like his

friend, Tom Hughes—Tom was a term of endearment in this case—he did not,

while cultivating the intellectual, neglect the physical element of man. When he had reached the age of sixty-one, and was president of the Maurice

Rowing Club, he is recorded to have won in a single season no fewer than

three prizes for his skill as a sculler. From what has just been said it

will be gathered that he retained at seventy-six his old affection for

boating on the river.

But we must hark back to 1855. Our class evenings were exquisite. Part of

the time Mr. Furnivall took the words as they followed in the

dictionary—dissecting them, showing their origin, and tracing their

transformation in sound, meaning, and spelling. Afterwards we read Chaucer

and Shakspeare, getting to the root and pursuing the history of every word

the poets used. Mr. Furnivall was at that time pale, handsome, and less

than thirty. The members of his class were mostly working men. But our

tutor put on no airs, as indeed none of the other tutors did. He was a

friend and companion even more than a teacher—absolutely one of

ourselves. It was his delight to take his class on walking or boating

excursions on the Sunday. I remember one glorious afternoon at Kew, for I

could not often join the party. Another summer afternoon I remember being

at Hampstead, when teacher and class came pelting along the road with

coats over their arms. Mr. Furnivall on other occasions invited the

students to his chambers after lessons. I joined them one winter's night. The chambers were in Ely Place, Holborn. Every nook and corner was filled

with books—all treasures of literature. Here we sat over biscuits and

coffee till an advanced hour of the morning, talking or listening to talk

about poets and poetry, and languages and literature, and having such a

feast of reason and flow of soul as almost never was since Shakspeare

had his bout with Ben Jonson at the Mermaid. Ely Place, closed to all

intruders by an iron gate in Holborn, was perhaps then the only locality

where an ancient custom of the Charlies was still observed. Anyway, we

heard the watchman crying in the street below—"Past two o'clock, and a

frosty morning." But Dr. Furnivall in those days burnt much midnight oil

in his studies, rarely retiring to bed, he told us himself, till five

hours "ayont the twal."

Three of the students of the college acquitted themselves so well that

they were elected to the Council of Teachers—Rossiter, Roebuck, and

Tansley. Rossiter was held in high favour and esteem both by professors

and students. And he eminently deserved the position he held, on account

alike of his genial qualities, his capacity for acquiring knowledge, and

his readiness at all times to impart what he knew to others. Influenced

probably by the commanding and attractive character of Maurice, Mr. Rossiter became a clergyman himself. Some ten years after the period I

have been writing about, he was instrumental in founding another college

in the metropolis—the South London Working Men's College, of which

Professor Huxley was for a long time the principal. Ten years later again

this institution was removed to Kennington Lane,

Lambeth, where Mr. Rossiter, placing his own books at the disposal of the

poorer classes of the neighbourhood, opened the first Free Library in

South London. Subsequently, a few pictures being added to the library,

this small exhibition became the germ of the South London Fine Art

Gallery, which, in 1897, having been acquired by the Camberwell Vestry,

was converted into the permanent establishment that is now known as the Passmore Edwards Art Gallery and Technical Institute. I was brought into

contact with Mr. Rossiter again some time in the early nineties—how I

can't recollect. But at that time he was a regular contributor of dramatic

and other notes to the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. When he died in 1897,

the event was sympathetically noticed by all the London and many of the

provincial newspapers; for he was, as the Times said of him, and as I can

testify from personal knowledge, "much beloved by all whose privilege it

was to share his friendship."

I cannot close this chapter without confessing that large numbers of

working people owe a deep debt of gratitude to the eminent and

enthusiastic gentlemen who, placing their scholarship at the service of

the artizans of London, helped to establish a real bond of union between

the richer and poorer classes of the country.

CHAPTER XXXIX

MANCHESTER

THE irritating nature of my employment in London,

coupled with the miserable wages I was able to earn, owing to the many

hours of weary idleness we had to pass in waiting for "copy," induced me

to accept the offer of a situation in Manchester. I had suffered so

much, mentally and bodily, from the treatment I had received in common

with the rest of our little companionship, that it was no longer a mystery

to me why working men hated their employers. If others endured what

I had endured, the animosity was not only excusable, but justified.

The root of the mischief was want of thought or consideration for people

whose lot it was to toil in shop or factory. Indifference to wrongs

and evils that can often be easily removed—how can it help but breed

bitterness and wrath? Had the captains of every industry behaved to

the rank and file as men ought always to behave to men, they would not

have planted those seeds of strife which have brought in recent years so

plentiful a crop of strikes and disasters. Bad masters sowed the

wind, and good masters are now reaping the whirlwind. But I am

digressing.

Manchester at the end of the fifties had stoned its prophets.

But it was still the seat and centre of the political school to which it

had given its name. Mr. Bright, handsome and portly, was often seen

in its streets, often heard on its platforms. The Free Trade Hall

was filled to overflowing whenever any great question was to be discussed.

It was there that I heard Kossuth; it was there that I heard Mason Jones;

it was there that I heard Washington Wilks. Kossuth we know; but who

were Jones and Wilks? Jones was an eloquent lecturer, Wilks an

eloquent politician of the day. The Hungarian exile met with a

magnificent reception. The audience seemed to cheer itself hoarse.

A few years later I heard Kossuth again. It was somewhere in

Clerkenwell. But the audience then was miserably scanty.

Between it and the applauding thousands in Manchester the contrast was

terrible. The fickle populace had forgotten or forsaken its idol.

No wonder that the poor exile, cast down and almost broken-hearted, soon

afterwards retired to another clime. The great hall in which so many

stirring scenes were enacted was one of the products of the corn-law

agitation. Mr. George Wilson, the chairman of the association that

conducted the movement, was yet an active force in the town. But

when he and other colleagues of his in the old organization ventured to

suggest an advance in the direction of Parliamentary reform, they were

described and assailed, I recollect, as the "rump of the League."

There came a time, however, as we may see later, when Manchester again led

the van.

Amusing to me, when I became a resident in the town, was the

evil reputation I had heard given to it by the chance acquaintance I had

met on the road only four or five years before. The people, I found,

were up to the average in behaviour and kindliness—above the average in

intelligence and cleanliness. There was not, I thought, a more

neighbourly woman in the world than the Manchester woman. As for

cleanliness, she took as much pride in the front of her house as she did

in her own kitchen, whereas women in other parts I have known never think

of even sweeping their pavements, no matter what the filth or foulness

accumulated around. But there were black spots about. Part of

Deansgate was a nest of thieves. The Irk was a foul and inky ditch,

and the Irwell and the Medlock were scarcely less loathsome. The

Town Hall was in King Street, and the site of the present municipal palace

was a camping-ground for Corporation dust carts.

Of course there was a better side to the town. The

first Free Library was established in a building that had been erected by

the followers of Robert Owen, and branch libraries were being opened in

different districts. The Athenæum

was a flourishing institution, as was the Mechanics' Institute, and a

Working Men's College was offering immense advantages to poor students.

Pomona Gardens in one direction and Bellevue Gardens in another were

favourite resorts of the people. Charles Calvert was manager of the

principal theatre, and Charles Hallé was

giving periodical concerts of the highest quality. Chetham Library

was a restful resort, where the quaintest of quaint volumes could be

consulted by everybody. Charming places surrounded the town.

Whalley Range was a residential suburb of exquisite beauty; Brooks's Bar

was away in the country; Greenheys Fields were charged with rural walks;

beyond Moss Lane the Moss-side Fields afforded opportunity for a lovely

ramble to Northenden. Chorlton-cum-Hardy was a delightful little

village within reach of Hulme on a Sunday morning in summer. For

Saturday afternoon excursions—factories and workshops and warehouses were

all closed at mid-day or soon after—there were Bowden and Alderley Edge

and many another point of attraction. So Manchester was not such a

bad place after all.

The situation I accepted was that of reader and compositor in

a small jobbing office. Our principal business was the production of

the Alliance News, the organ of the United Kingdom Alliance.

Mr. Thomas H. Barker was then the secretary of the society, and Mr. Henry

Septimus Sutton the editor of the paper. Mr. Barker was a man of

great energy, absolutely absorbed in his work; Mr. Sutton was a bit of a

poet ("Emerson thought some of his pieces were worthy of George Herbert ")

who ingeniously turned almost every event of the day into an argument for

the prohibition of the liquor traffic. What I chiefly recollect

about the Alliance at that time was the long, elaborate, and masterly

reports which Mr. Samuel Pope, the hon. secretary, used to produce for the

annual meetings of the society. [24] Yes, I

recollect another thing. A question had been submitted by the

Alliance to the clergy and ministers of religion throughout the country,

and hundreds of letters had been received in reply. These replies

were printed in the News, and passed through my hands as reader.

I was astonished at the loose, slovenly, and ungrammatical way in which

educated men—all of whom had been trained in colleges and some of whom had

won degrees in universities—expressed themselves. It occurred to me

that these gentlemen had spent so much time in the study of Latin and

Greek and Hebrew that they had forgotten to learn English.

The change I had made was, as Mr. Epps said of his cocoa,

grateful and comforting. I had regular work, regular hours, regular

wages—always my evenings at home or to myself, except once a week. I

had now several hours of a night which I could spend in my own pleasures

or my own pursuits—in reading, writing, taking a stroll, or attending a

class. Life was no longer a weariness: it was a real enjoyment.

I was happy and contented: so was my dear companion. There wasn't a

happier or more contented couple in all Manchester. The men with

whom I worked, too, were generally of a higher order than those I had

encountered in London. While there was less dissipation among them,

there was also, as may be supposed, a more refined taste. Every man

in the establishment, and indeed every boy, took an intelligent interest

in public affairs. The talk was of politics, of literature, of

cheering events of the day. Men and boys read the newspapers, the

magazines, books; and they had views of their own about all they read.

The Free Libraries were a boon and a blessing to many of them.

Besides borrowing books from the libraries, we had a book club of our own.

Thus we kept ourselves abreast of the culture of the time. Better

than all, I found lifelong friends in Manchester, one in the office,

others elsewhere. The friend I made in the office was one of the

gentlest, best read, and most refined gentlemen I have ever met. [25]

It was in such sweet companionship at home or on pedestrian excursions

among the picturesque dales and peaks of Derbyshire that my four years in

Manchester passed like a summer holiday.

There was a Working Men's College in Manchester too. I

made other friends at the college. The classes I attended were

conducted, the one by a Unitarian minister, the other by a curate of the

Church of England. The Unitarian minister was the Rev. William

Gaskell, husband of the famous novelist; the curate of the Church of

England was the Rev. William Thackeray Marriott, who, leaving the Church,

became first a barrister, then a member of Parliament, and finally the

Right Honourable Sir W. T. Marriott. Mr. Gaskell was a master of

literature. I thought at the time that he was the most beautiful

reader I had ever heard. Prose or poetry seemed to acquire new

lustre and elegance when he read it. Our literary evenings under Mr.

Gaskell were ambrosial evenings indeed. [26] Mr.

Marriott's class was devoted to the History of England. The reverend

gentleman was as little like a clergyman as he was like a costermonger.

There was nothing clerical—nothing even conventional—about him. Free and

easy in his manners, he was as familiar with the members of his class as

they were with each other. Even his lectures, if they could be called

lectures, were notable for their freedom from the least sign of pedantry.

It was really a conversation on historic subjects that he carried on with

the working men who sat before him. Mr. Marriott's views, moreover,

especially on the controversy between the Parliament and Charles the

First, were of a very advanced character. Our old tutor has figured in

many prominent transactions since 1859, but in none which was more

calculated to win the esteem and regard of his old scholars. Besides

literature and history, I tried my hand at logic, under Professor Newth of

the Lancashire Independent College. But logic, literature, and history, so

far as classes were concerned, had to be abandoned when the Working Men's

College, greatly to the disappointment of the students, was merged into

Owens College, then situated in an old mansion in Deansgate, but now

located in a palatial home of its own.

While gratifying my taste for such studies as I had time or

capacity for pursuing, I did not forget the republican idea. Whenever

chances presented themselves, the editors of the local papers—the

Examiner, the Guardian, and the Courier—were pestered with letters in

defence of Mazzini or in explanation of revolutionary enterprises. With

the view of reviving interest in the Reform question, I wrote, printed,

and published at my own expense a rather heavy "Argument for Complete

Suffrage." But nobody wanted the pamphlet, and I was burdened with a debt

which took me a long time to pay off. Also I wrote,

and here and there delivered, a lecture on a still heavier subject—"The

Province of Authority in Matters of Opinion." This was printed too, but

nobody wanted it either. However, a peculiar opportunity for getting said

what I wanted said occurred in the summer of 1859. Somebody speculated on

the publication of a weekly paper called the Buxton Visitor. It was

printed in our office. The speculators had no notion of what was wanted

for even an ephemeral journal. All they supplied was a list of the

visitors to the Derbyshire town, with of course the advertisements. The

rest of the matter had to be found by the printer. I was asked to write

the leading articles—gratuitously of course. Yes, I said, if I was allowed

to choose my own subjects and treat them in my own way. It was the time

when Louis Napoleon went to war for what he called an idea—the idea

subsequently taking the substantial form of a couple of Italian provinces. Well, I pegged away at the war and other questions all through the season. The summer butterflies who fluttered about Buxton must have been much

surprised when they read, if they did read, the fiery lucubrations that

occupied the leading columns of the Visitor. At that time I was rejoiced

when I could get my opinions before the public, anyhow or anywhere.

I would write anything for nothing if I approved of it—nothing for

anything if I did not. A quack doctor wanted his wretched treatise revised,

and an invitingly handsome sum was offered me to do the work. I refused. Great was the astonishment of the smug printer, who went regularly to

church with silk hat and prayer-book of a Sunday morning, when I politely

declined a proposition which he thought any poor devil in my situation

would jump at. "Old Jacky," as we called him, did not understand how

anybody could be fool enough to make a conscience of writing.

Mr. Ruskin, during my time, came to Manchester to lecture on some art

subject. The chair, I remember, was taken by the Mayor—then Mr. Ivie

Mackie. His worship was a spirit merchant—a man of liberal sentiments, but

not, I thought, very intellectual. Stout and stolid, he sat in the chair

without moving a muscle of his face or betraying the least interest in

the subject. Presently, however, Mr. Ruskin quoted Goldsmith's epistle to

Lord Clare for the gift of a haunch of venison:—

|

Thanks, my lord, for your

venison, for finer or fatter

Ne'er ranged in a forest or smoked on a platter;

The haunch was a picture

for painters to study,

The fat was so rich, and the lean was so ruddy. |

Here was something the Mayor could understand.

It probably revived recollections of feasts he had enjoyed. Anyhow, he

laughed consumedly. I think it was the only time he smiled or showed any

intelligence throughout the discourse. As for Mr. Ruskin—I had not then

read any of his books, and knew little or nothing of his style as a writer

of pure and beautiful English—I am afraid I was not very much impressed

with either his appearance or his performance. Admiration for the man and

the author came later. |