|

[Previous Page]

THE BLANK LINE.

EVERYBODY who

knew anything about the case agreed with absolute and emphatic

unanimity, that there never was such a body of trustees as that

which built the Floxton Common new chapel.

The super said so, and the tightening of his thin lips and

the projection of his strong, clean jaw as he made the declaration

left nothing to be desired in the way of uncompromising statement.

The resident minister said so, and as he had taken part in

trustees' meetings, committee meetings, sub-committees and the like

almost every other night for the last eighteen months, surely his

evidence is uncontrovertible.

The trustees said so themselves, and inasmuch as several of

them had almost lived on the premises during the all-absorbing

erection, and had been threatened by their respective wives with

separation applications, divorce proceedings, etc., to say nothing

of such everyday suggestions as those of sending them their beds and

meals to the premises, it must be admitted that they had a right to

an opinion on the subject. But even people who only came into

occasional contact with them got the same impression.

The architect declared solemnly, that he had never served so

extraordinary a body of men during the whole course of his

professional career, and he added when he got into safe company that

he hoped he never should again.

The Manchester committee people shook their wise heads at the

very mention of Floxton Common, and gave vent to sighs expressive of

unspeakable feelings, and even the President of the Conference when

he went to open the chapel said they were the most extraordinary

body of men he had ever met,

The super said that nothing surprised him so much about these

"Brethren" as their automatic unanimity—except it was their chronic

disagreement. Against the architect, the super, the "red-tapeism"

of the Manchester Committee, they were a solid unit, but amongst

themselves they did not agree, even about the most trivial things.

At every one of their innumerable meetings some one either resigned

or consented to withdraw a previous resignation, and nearly every

man on the board had declared at one time or other that nothing

should ever induce him to go near the place again.

Brother Bottoms had withdrawn on the sites question, and

Brother Taubman on the selection of the architect, whilst Brother

Eli Waites, who was disgusted with the "baby work" of the two

gentlemen mentioned, sent in his resignation and even withdrew his

subscription when it came to a spire.

The youngest trustee, a mere upstart of forty, caused two meetings

and two adjournments about the position of the pulpit, which he

insisted should be at the right corner of the chancel arch as

appointed by the architect, and of course resigned when the older

members of the meeting on anti-ritualistic grounds insisted on its

being placed in the middle; and they in their turn threatened to

leave if the entrance, which in the old chapel had always been

called the porch, was christened the "Narthex."

The young minister of the circuit, who was a probationer

fresh from college, was considerably exercised by the irreconcilable

inconsistencies which he detected in these good men, for as he went

about his work he was compelled to hear all about these points of

difference, and when the last touches were being put upon the

building and it was being got ready for the opening services, he was

amazed to discover the men who had objected so strenuously to spire

or pulpit or narthex taking their friends round and showing these

particular things as the specialities of the new sanctuary, and even

in one or two cases seeming to wish to convey the idea that they

were the original suggesters of these features; at any rate they

seemed to be the things they were most proud of, and took the

greatest delight in exhibiting.

But after all it was a noble thing these people had done;

they were not a rich Church nor a very numerous one, yet they had by

hard work and wonderful self-sacrifice built a beautiful edifice at

a cost of nearly £7,000, which they intended to open free of debt,

and the super, in spite of his many troubles with them, was full of

admiration for the way they had acted, and was prompted to say, as

he had often done before, that there were no people like the

Methodists after all.

And just at the time when they thought they had got through

all their trials, they were plunged into one that was worse than any

they had come through. When the day came for selecting the

places they would occupy in the new building, it turned out that

there were two applicants for one pew—the back pew in the chapel.

Old Mr. Bottoms had sat in the back pew in the old chapel,

and thought he ought to have the same place in the new one, and

James Higson, who had a delicate wife who sometimes wanted to go out

before the service was concluded, had set his heart upon it, and

hand stated twenty times over, he declared, that he should want that

particular seat.

The trustees might have settled the matter in their

boisterous way if left to themselves, but unfortunately Barbara, old

Bottoms' daughter, a female of a certain age, and an old flame of

Higson's, took up the cudgels for what she called their "rights,"

and attacked Higson, who was chapel steward, before strangers, as he

was arranging with other pew-holders for their seats.

Eventually the matter came before the trustees, and after the

usual long wrangle, was decided against Higson. As soon as the

decision was announced, he rose to his feet, took up his hat, bowed

with mock ceremoniousness to the chairman and then to the meeting,

and walked out of the room.

One or two went after him and did not return. Those who

remained behind took no further interest in the business, and when a

few minutes later the super and his colleague called at Higson's he

refused to see them, and next day sent all his books in, and

signified that he had done with the Wesleyans once for all and for

ever.

The super, though not given much to sentiment, was quite

touched to see the distress of the trustees when they found that

Higson's defection was serious and apparently final; they refused

even to discuss the question of filling his offices, and old

Bottoms, in spite of terrible threats from his aggressive daughter,

sent at least two notes to Holly Villa, where Higson lived, to ask

him to take the pew he wanted. But all was in vain.

As the great day of the opening drew near all sorts of clumsy

attempts were made to bring about a reconciliation, and Billy

Clipston, the shoemaker, declared again and again that when the time

came Higson would not be able to stay away, but would turn up "as

sure as heggs is heggs."

But the day came and went, and the offended one did not

appear, and the super heard in the vestry and in the aisles of the

chapel a great deal more about the absent man's many past services

than he heard about the event they were actually celebrating.

They told of what he had endured for the sake of the good cause, and

altogether the éclat of one of the greatest days in the

history of Floxton Common Methodism was spoilt by the constant

lamentations of the chief men about the place because their old

fellow-worker had not taken part. The opening services were

continued for three Sundays, and it was confidently prophesied by

Billy and others that Higson would never be able to hold out to the

end.

But he did; and when they sang the final doxology at the last

of the opening services, because it was not only opened, but free

from debt, two or three of them told their minister afterwards that

they had not enjoyed their great victory at all, and would rather

have a thousand pounds debt with Higson than all the triumph of the

day without him.

Well, at any rate it was a notable achievement, and the super

was more than pleased with the noble way in which the people had

carried out and finished their great undertaking.

And then something else began to trouble him. He had

said as little as possible about the great Million Scheme whilst the

good folk of Floxton Common were straining every nerve and almost

punishing themselves to clear their chapel, and now it seemed

exceedingly hard upon them to ask them to look at another effort.

But circumstances left him no option; he had already made a definite

promise of £2,000 for the circuit; they had held the meeting at the

circuit chapel, and the contributions had somewhat disappointed him,

so that there was now nothing for it but to have the meeting as soon

as possible at "The Common." He was almost ashamed to name the

matter to them, but to his surprise the good folk expressed a great

interest in the scheme, and were not at all inclined to shuffle it.

In fact, as old Bottoms said in his sententious way: "We've gotten a

grand chap—church, Mester Shuper, an' we mun show az we appreciate

it, sir."

This was at the final trustees' meeting when the accounts had

been presented, and the votes of thanks given to those who had borne

the lion's share of the burden, a special resolution being sent to

Higson. After all the regular business had been concluded, the

super in a regretful, almost apologetic way, introduced the thing

that was just then resting somewhat heavily upon his mind.

Yes, they would go into the subject at once, as far as unofficial

suggestions were concerned at any rate. Names were mentioned

of those who would make the most effective officers for the local

fund, and a time was fixed for the holding of the meeting.

And then Blamires, the youngest trustee, had an inspiration,

and suggested that as they had all worked together so harmoniously

in this grand chapel building effort, and were all so proud of the

finished work, they should have their names down on the roll

together in the same order as they came in the trust deed.

Coming from this juvenile and impetuous source the proposition was

received with hesitation, but presently it seemed to catch their

imaginations, and they insisted upon its being so.

The super, whose chief anxiety had been the fear that they

would resent being appealed to again so soon, was only too glad to

acquiesce, and so the meeting adjourned for a couple of days to

enable the super to bring the roll that they might all sign it in

order as agreed upon.

Just as they were leaving the vestry, old Bottoms made a loud

exclamation of dismay, and then rising to his feet, for he was still

sitting at the far end of the room, he said mournfully: "There's one

thing az you've forgot, Mester Shuper."

"Indeed! What's that, Brother Bottoms?" and the super

stepped up to the table.

"There'll be one name missing."

Everybody looked suddenly very sober, little sighs escaped

them, and they glanced at each other in sorrow and disappointment.

But the super's train was due, and so he was compelled to ask them

to think the matter over until the adjourned meeting should be held.

There was much debate and questioning amongst the trustees

about what should be done in this difficulty. The more they

thought of it, the more they liked the idea of all signing together,

but the less likelihood did they see of getting the missing

signature. Moreover, it occurred to one of them that it would

look a very mean sort of thing to try and get Higson back, just in

order to get his subscription to the Million Scheme, and so nobody

could suggest any way out of the difficulty, and the super could not

help them.

The minister had informed them that as they would all give

more than the minimum amount, there was no reason why their names

should not head the list of the Floxton Common contributions, though

nobody had as yet named the sum he was intending to give, that being

reserved for the great meeting in the church.

It took them half an hour, however, to make up their minds to

enrol themselves in the absence of their estranged colleague, and at

last it was decided that a line should be left blank for Higson in

the hope that something might occur in the meantime to bring the

wanderer back. Young Blamires signed readily, but old Bottoms,

who was next, hesitated considerably, and then at last put down his

pen, and in a tearful voice faltered: "I'll gi' me money, bud I

don't want to be on if he isn't."

Whilst the old man was recovering himself and getting

persuaded to do his part, the next man signed, and then the old

fellow tremblingly followed. The next in order was Higson, and

a blank space had to be left, and hard though it had been to sign

before, it was much harder now with that blank line staring them in

the face.

The super went home that night in a brown study; whatever

could he do to reach Higson? for he felt that this effort would be

shorn of nearly all its sweetness to the good people if Higson's

name were not on the list, and they had really done so nobly that he

coveted the pleasure of this reconciliation. And he got up

next morning with the same feeling in his mind.

It took him an hour or so to dispose of his correspondence,

but when that was done he drew the precious roll out of his safe and

began to look once more at the names that had been signed the night

before. In a moment or two it dawned upon him that that blank

line looked very awkward indeed, and if it were not filled up it

would be more eloquent than all the names that went before or came

after. What a mistake he had made in allowing those whimsical

trustees to have their fad. It would, perhaps, be the only

blank line in the whole roll, and how strange it would look.

Besides, he had a reputation for neatness and orderliness, and that

would be there as a witness against him for ever.

The thing bothered him and then annoyed him, and he was just

sitting down in a sort of pet with himself when a blessèd thought

occurred to him. It was not absolutely necessary that a

contributor should sign his own name. He liked Higson, and

greatly valued him, both for his work and himself. He would

keep his own counsel, and if nothing occurred to change the state of

affairs, he would write Higson's name in himself and subscribe the

extra guinea. He had a large family, and every shilling

counted with him, but he would do that, whatever he had to sacrifice

in other ways. The super was pleased with the idea, and

pleased with himself for thinking of it, and he was just laughing at

his own self-complacency, when a knock came at the study door and

Brother Bottoms was announced.

The senior trustee shambled into the room in his

characteristic manner, and shook hands limply with his

ecclesiastical superior.

He took off his hat and placed it shyly on the floor by the

side of his chair, and then, taking a red pocket-handkerchief out of

the tail pocket of his antique black coat, he commenced: "I thought

I would just call and pay my Home Mission Fund collection, sir," and

he fumbled in his pocket and produced a little wash-leather bag,

from which he drew two half-crowns, which he placed in the

minister's hand.

The super reached out a report, which serves in these cases

as a receipt, and handed it to his visitor, wondering what was the

old fellow's real reason for calling. Bottoms took the report

without glancing at it, and then began to discuss the weather.

The subject provided an interesting topic for a minute or two, for

atmospheric conditions were just then very trying, and then there

was an awkward pause.

"I see you've got the great roll there, Mr. Shuper," said

Bottoms after a while, and he glanced round as though he would like

to look at it.

The super opened it upon the desk, and the old man got up and

carefully examined it inside and out. "H-u-m! Ha!

wonderful dockyment, Mester Shuper. We must all have our names

in that," and the minister noted that his visitor was looking very

dreely at the blank space where Higson's signature should have been.

He seemed to have nothing further to say, however, and in a few

moments rose to go.

"Well, good morning, sir, and thank you; I hope you will get

all the names you want," and then, just as he was going out of the

door, "Oh! beg pardon," and he came back and drew out the

wash-leather bag again. It took him some time to find what he

wanted, but presently he pushed a sovereign and a shilling into the

super's palm, saying as he did so: "Just put Higson's name down

there, sir; we can't have him off, you know," and before the

minister could stop him he was gone.

The super was a little nonplussed and disappointed; but

Bottoms was better off than he was, and—well, they might make it two

guineas perhaps. The same afternoon as he was going to his

class he heard some one calling after him and turning round saw

Waites, the corn factor hastening towards him.

Waites was always in a hurry, and on this occasion he

appeared more than usually so. "Here, Mr. Super, take that.

It's a fiver; put it into that fund and drop Higson's name in, will

you? Ah, here's the tram. Good day, sir."

The super was amused and touched; it began to dawn upon him

that Higson's contribution premised to be a pretty large one, if

things went on like this, and when he got home that night another of

the trustees was waiting for him. This man seemed to be

entirely unable to tell what he had come about, but at last he

blurted out:

"Mr. Super, I've come about Higson and that roll. He

must be on, sir, he must; he's done more for Methodism in this place

than any other three of us, and his family is the oldest in the

circuit. Why, his grandfather was at the opening of the first

Methodist chapel there ever was in the Common."

But the super intended to keep his secret at least for the

present, and so he said: "Yes, but we can't make the man contribute,

you know."

"No, but we can do it for him, and we will! I will!

Me? Why, sir, he got me the first situation I ever had.

He led me to the penitent form, he helped me to get my wife.

He's injured his business to look after that chapel. He

must be on, whoever else is."

"Well, but how are we to manage it? We've tried

everything we could think of"

"Manage it! We must manage it. Look here,

sir! I'll pay his share myself."

"But I've already got a guinea for him and――"

"A guinea! A guinea for the best man among us!

Why, sir, it would be a sin and a shame for Higson's name to only

represent a guinea. Look here, sir, it must be twenty at

least! Yes, twenty! and I'll find it myself."

When he had gone the super told his wife, and she put on an

air of confidence which was always rather aggravating to her

husband, and said: "Neither your money nor anybody else's will be

needed. Higson will put his own name in, you'll see."

At last the time for the holding of the Flexion Common

meeting came, and the super told his colleagues that they must not

be disappointed if the results were not what they might expect, as

the "Common" people had really done so well that they couldn't do

much more, however good their intentions.

As he had prophesied, the meeting was not largely attended,

and even he felt depressed as he noticed how few there were there

who could give much. The chairman was a "Common" man, and

started the meeting with a rousing, confident speech, which he

crowned with a promise of fifty pounds.

The super stared from the speaker to his colleagues in

amazement as the sum was named; it was three times the amount he had

expected. Then the resident minister spoke, and promised an

outrageously extravagant sum for himself and wife and little ones.

Then there was a pause, and presently old Bottoms rose to his feet.

He had a mournful, melancholy tone with him, and always spoke at

great length, but at last he announced that as the Lord had been so

good to them in the chapel scheme, he could not give less than a

hundred pounds.

The meeting applauded this to the echo, for Bottoms had a

reputation for nearness. Then two or three more followed in a

similar strain, until the poor super, scarcely knowing where he was,

felt his eyes growing dim, and had to blow his nose. Then they

sang a hymn, and were just sitting down again, when the man who was

acting as temporary chapel steward suddenly opened the inner door

and threw up his arms with a gesture of wondering triumph, and the

next moment who should walk into the chapel but Higson.

He was a short, ruddy man, and now looked redder than ever.

He held his hat in his hand and gazed wonderingly about the chapel,

which he had never seen since it was finished, and walked

staggeringly up towards the front. Presently he stopped, his

hat dropped out of his hand, and he lifted a red, agitated face

towards the platform and cried:

"I had to come, Mr. Super, I had to come! I've

been the wretchedest man in Floxton parish this last two months, but

I couldn't miss this. My father laid the foundation stone of

the last chapel, and my grandfather was the first trustee of the

oldest chapel of all. Everything I have I owe to this Church,

and my own bairns have been converted here. I've heard what

you are thinking of doing with my name, and that brought me here

to-night, that killed my pride. God forgive me. Put me

down for a hundred pounds, Mr. Super, if I'm not too bad, and I'll

sit in the free seats if you'll let me come again.

The meeting was some time before it got composed, and then

the subscriptions began to roll in faster than ever.

That night, after Higson had been down to the manse and

signed the roll, the super repeated once more his old saying, that

the Floxton people were the strangest people he had ever travelled

amongst, but this time he added, "and the best."

――――♦――――

A COSTLY CONTRIBUTION.

TWO elderly

ladies sat by the fire in a comfortably furnished room, the walls of

which were adorned with steel engravings of scenes in the lives of

the Wesleys, Centenary gatherings, and a large photograph of the

first lay representative Conference. The one seated in the low

modern armchair on the side nearest the window was small and thin,

with white hair and fair skin, and cheeks like old china. She

had a meek, Quaker-like look about her, and her dress was of plain

silver grey.

The other one was taller than her sister and dark, and had a

masculine mouth, at the corners of which there were lines which had

been left by bygone storms. She was reading the newly arrived

Methodist Recorder, and there was a disappointed, almost

peevish look on her face, and presently she threw the paper from her

with an impatient jerk, and as it fluttered to the hearthrug she

shaded her face with her hand and gazed moodily into the fire.

Her soft-eyed little sister glanced concernedly at her once or

twice, sighed a little, and then asked gently: "Anybody dead, love?"

"No; nobody we know."

Another slight pause, and then in a caressing tone: "Anybody

married?"

"No."

"Any news about Hanster?"

"No."

The little Quakeress's knitting seemed to trouble her just

then and her thin, almost transparent hands shook a little as she

fumbled for the dropped stitch. In a moment, however, she

lifted her head and asked coaxingly: "Is there nothing interesting,

love?"

Miss Hannah dropped the hand that covered her eyes, glanced

petulantly round the room and then answered pensively: "Susan,

there's one thing in that paper and one only."

The head of the meek little woman opposite to her was bent

over her knitting, the pearly cheek paled a little, and then she

asked: "And that, love?"

"That paper has got nothing in it but Twentieth Century; it

is Twentieth Century first page and Twentieth Century last, and

Twentieth Century all the way through. Oh, that we should have

lived to see this day Hannah!"

"I mean it, Susan;" and the excited woman began to rock

herself in an increasing grief. "There was a Branscombe who

entertained Mr. Wesley, there have been Branscombes in every great

movement our Church has seen; our father sat in the first Lay

Conference and we both subscribed to the Thanksgiving Fund

ourselves. And now that our Church is doing the noblest thing

she ever did we shall be out of it. Oh, that we had gone

before it came!"

"No, no, love, not so bad as that; we can give our guinea

each, and—and one in memory of our dear father, ah—with a little

more economy."

"Guineas! Branscombes giving single guineas! Our

dear father down on that great historic roll for a guinea!

Susan, how can you? what will the village think? And the

Hanster people, and father's old Conference friends? They

might suspect something! We cannot think of it for a moment"

Miss Hannah had risen to her feet during her speech, but now,

with a fretful, half-indignant gesture, she sank back into her chair

and once more covered her face with her hands.

Little Miss Susan stole anxious, sympathetic glances across

the room for a moment or two, and then, letting her knitting slide

down upon her footstool, she stepped softly to the side of her

sister's chair, and, bending over and pressing her delicate cheek

against Miss Hannah's darker one, she murmured soothingly

|

"And if some things I do not ask,

In my cup of blessing be;

I would have my spirit filled the more

With grateful love to Thee,

And careful less to serve Thee much

Than to please Thee perfectly." |

As these lines were repeated the face of Miss Hannah

softened, the shadow upon it gradually disappeared, and in the pause

that followed a gentle light came into her black eyes. She

bent forward and silently kissed the dear face that was still bent

over her, and then said impulsively:

"Bless you, love! What have I done to deserve such a

sweet comforter? But I should like to have done one more good

thing for God and our Church before I go to heaven."

"Never mind, dearest! When we get to heaven the Master

will perhaps say to us as He said to David."

"What was that?

"Thou didst well that it was in thine heart."

Now, the father of these two ladies had been a prosperous,

well-to-do Methodist layman of Connexional repute, but when he died

it was discovered that all his means were in his business, and that

he had really saved very little. His funeral was attended by

great numbers of Methodist magnates, lay and clerical, from all

parts of the country, and the respect shown to their father's memory

had been a sweet consolation to the bereaved sisters.

But whilst they were receiving the written and spoken

sympathies of many friends, the family lawyer was expressing himself

to himself in language that was to say the least very

unparliamentary. Branscombe's business was certainly a

lucrative one, and whilst he was there to attend to it all was well;

but the man who spent or gave away all his income, when he had two

daughters unprovided for was, in the lawyer's judgment, more fool

than saint, and he ground his teeth savagely when he discovered that

he would have to explain to the sorrowing women that they would have

to change their style of life.

There was nothing else for it, however. The business

would have to be carried on, for it was not the sort of thing that

would realise much when sold. A manager would therefore have

to be paid, and when that was done there would not be very much left

for the two ladies who had always been brought up in such comfort.

Lawyer Bedwell had no patience with men who left their

affairs like that, and in spite of himself, some of his feeling on

the point slipped out upon his first interview with his fair

clients.

When he had gone, their minds were occupied with one thought

only. It was clear that Mr. Befell thought their father

blameworthy in the matter, and if he did others would be of the same

opinion. But they knew as no one else did, how true and noble

a parent they had lost, and at all costs they were determined that

nothing should be done that would excite suspicion in the minds of

their friends. Appearances, therefore, must be kept up, and

everything must go on as usual; all their father's subscriptions

must be continued, and their home must still be the chief house of

entertainment in Hanster.

But as time went on these things became more and more

difficult. Nearly half the profits of the business had to go

to pay a manager; but, as he was not Mr. Branscombe and the concern

had depended largely upon the personal effort and influence of its

chief, there was a serious annual shrinkage, in spite of all that

Lawyer Bedwell could do to prevent it. Then the manager

precipitated a crisis by absconding with some hundreds of pounds,

and the legal adviser to the firm was compelled to recommend that

the business be sold and that the ladies should reduce their

establishment, so as to be able to live upon what was left.

For their own sakes this might easily have been done, but for

their father's they could not think of it. At last, however,

they decided to leave the little town where they had been born, and

where all their interests centred, and go into some quiet village,

where they might live cheaply, and do in a smaller way the kind of

work their father had done in Hanster.

And so they came to Pumphrey, where they were regarded as

very great people indeed, and where their now reduced contributions

were received as most munificent donations. But the habits of

a lifetime are not easily unlearnt, and so, finding that the memory

of their father was still fragrant in Pumphrey, and that the simple

inhabitants of the village were ready to give them all the respect

and deference due to their antecedents, they were soon acting in the

old open-handed way; and whilst the little circuit in which the

village was situate rejoiced in and boasted of their generosity, the

poor ladies were constantly over-reaching themselves and lived in a

condition of chronic impecuniosity.

Their personal expenses were pared down until they could be

reduced no further, but the large-hearted liberality to which they

had always been accustomed and which regard for their father's

memory seemed to demand, was continued as far as possible.

Recently, however, Miss Susan had had a severe illness, and this,

with the heavy doctor's bill it involved, had reduced them still

further, and the announcement of the Twentieth Century Fund found

them in the worst possible condition for doing their duty to it.

The long pensive silence that fell upon the sisters after

Miss Susan's last remark was broken presently by a knock at the

door, and Jane their faithful, if somewhat unmanageable, domestic

brought in the supper. Placing the little tray containing hot

milk and thin bread and butter on the table, she picked up the

Methodist Recorder and somewhat ostentatiously proceeded to put

it away in the homemade rack at the side of the fireplace.

"You can take the paper with you, Jane," said Miss Hannah.

"I dooan't want it, mum," answered Jane gruffly, and in

broadest Yorkshire.

"You don't want it, Jane! Why, it is full of news this

week, all about the Twentieth Century Fund, you know."

"That's just it, mum! that theer fund I caan't abeear!

It's gotten hup out o' pride an' pomp an' vanity, that's wot it is,

an it'ull niver prosper, mark my wods!"

"Jane!"

"I mean it, mum! Thank goodness, nooan a my muney 'ull

gooa tab sitchan a thing, an' bi wot I can hear ther's nooan o' t'

villigers gooin' tab give nowt neeither."

"But, Jane――"

But before Miss Hannah could stop her, Jane had burst forth

again: "It's nowt bud pride, an wickidness, mum, it's woss nor that

king as showed his treasures to that Babshakklep, an as fur that

theer rowl, it's King Daavid numberin' Hisrael, that's wot it is."

"But, Jane, we must all――"

"Yes, mum, that's wot you alias says, beggin' your pardon,

bud it's my belief you ladies 'ud subscribe tab buyin' t' moon if t'

Conference wanted it; bud I'm different, an' if I hed my waay not a

penny 'ud goa oot o' this house ta that Million Fund."

As the privileged and outspoken Jane closed the door behind

her, the two ladies looked at each other with astonishment, for Jane

was as stout a supporter of all things Methodistic as they were, and

they had difficulty sometimes in restraining her liberality.

To Miss Hannah, however, their old servant's words were more

disturbing than to her mild sister. She did all the business

of the establishment and had charge of the purse, and she had

privately resolved in spite of her querulous words to her sister

that, if the worst came to the worst, she would do as she had been

driven to do once or twice before and get a temporary loan from

Jane; but, if Jane disapproved of the fund, there might be

difficulty, for nothing was concealed from her, and, in fact, she

had more to do with the financial arrangements of the little family

than even Miss Hannah herself.

Meanwhile Jane, who was short and plump with bright black

eyes and black hair, had made her way back into the kitchen, where

sat a ruddy-looking man of about thirty, dressed like a gardener,

and whose face wore an injured, protesting expression whilst he

leaned forward propping his elbows on his knees and nervously

twirling his cap round with his hands. He glanced sulkily up

from under his brows as Jane entered the kitchen, and furtively

watched her as she picked up a wash-leather and resumed her work at

the plate basket.

The gardener gave his cap a fierce extra twirl and then

grumbled: "Ther niver wur nooabody humbugged like me; this is t'

fowert (fourth) time I've been putten off."

Jane gave an ominous sniff; her plump face hardened a little,

but she never spoke.

"It's t' Million Fund an' t' Mississes an' onnybody afoor

me."

The spoon Jane was rubbing was flung into the basket with a

peevish rattle, and rising to her feet and stepping to the rug

before the fire she said indignantly: "John Craake, hev some sense,

wilta? Here I've been telling lies like a good 'un i' t'

parlour till I can hardly bide mysen, an' noo I mun cum back ta be

aggravated bi thee. Them owd haangils i' t' parlour 'ud sell

t' frocks offen they backs tab subscribe ta this fund, an' thou sits

theer talkin' about weddins an sitch like floppery. I wunder

thou isn't ashaamed o' thisen."

John sat ruminating dolefully for a moment or two, and then

he wiped his nose with the back of his hand and said with sulky

resignation: "Well, what mun I dew then?"

"Dew? thou mun cum i' t' morning an' saay thi saay to em, an'

if that weean't dew, thou mun waait, that's what thou mun

dew."

Now John had been courting Jane in a dogged sort of way

almost ever since the Branscombes came to Pumphrey, but until

recently he had made little apparent progress. Some few months

before the time of which we write, however, a terrible burglary with

murderous incidents had taken place in the neighbourhood, and as the

news greatly upset the old ladies and made them declare that they

would never be able to stay in the house unless they could have a

man about the place, Jane had made a virtue of necessity and

accepted her lover, on the understanding that he was to come and

live in the house, and never suggest any other arrangement so long

as the old ladies lived.

John had eagerly agreed; but, though the wedding had been

fixed now three times, it had so far been put off again and again,

because, as John eventually discovered, the money which Jane with a

Yorkshire woman's thrifty ideas felt was absolutely necessary for a

decent woman's wedding, had been sacrificed to the needs of her

mistresses.

And now it had seemed that the happy event was really to come

off, and just at the last minute, so to speak, this Million Scheme

had turned up, and Jane insisted that before her spare cash was

spent on such a frivolous thing as getting married she must be sure

that it was not wanted to enable her mistresses to subscribe to the

fund as became the daughters of Thomas Branscombe. For Jane,

be it said, was as jealous for the honour of her old master as his

daughters. She was, moreover, a Methodist of the Methodists,

and had upon the first announcement of the fund decided that it was

her duty to give at least five pounds to so glorious an object.

This idea, however, she now abandoned, and whilst she

consented to try and persuade her mistresses not to think of

subscribing and had agreed that John should use his powers of

persuasion in the same direction, she knew but too well that the

dear old souls she worshipped would insist upon taking their part in

the great movement, and therefore the money she intended to have

given for herself and the money needed for the approaching wedding

would all be required for the old ladies' subscription. And,

even if the sisters themselves could be talked over, she still felt

that their names ought to be on the roll and that it was her duty to

get them on, even if she had to do it unknown to them, and pay the

subscriptions herself.

Next morning, therefore, John did his best to convince the

ladies that nobody thereabouts cared anything for the fund, and that

it would be useless to hold a meeting in the village for the

purpose. Encouraged by Miss Hannah's manner as he respectfully

argued with her, he even suggested that she should write to the

super advising him not to think of holding a meeting in Pumphrey.

Jane, however, when he told her what he had said in the parlour, was

worse than sceptical, and insisted on him as a leader writing to the

super himself.

A post or two later, however, a reply came to say that the

meeting was fixed for the following Thursday night, and that

Pumphrey surely would not be behind other places. John

hastened to Pear Tree Cottage to tell the news as soon as he got the

letter; but on entering the kitchen he was interrupted in his story

by the alarming information that Miss Susan had been taken ill in

the night, and he must hasten away for the doctor.

The Thursday night came, and the super, alarmed and

disappointed at not seeing "The Ladies" at the meeting, discovered

on enquiry that Miss Susan was confined to her room, and that the

doctor's report was not encouraging. The good man therefore

came round on his way home, and Miss Hannah came down from the

sick-room to speak to him.

Her report of the condition of the patient was so

discouraging, and she herself looked so sad, that the good pastor

forgot all about the meeting and was just saying good-night when

Miss Hannah said: "I was sorry we missed the meeting but" (with

hesitation and embarrassment) "of course we shall send our

subscription."

"Send it? But you did send it, Miss Branscombe."

"No! but we will do; it will be all right, Mr. Makinson."

"But you did send it, excuse me, and a very nice one it is.

See, here it is," and the minister pulled out a small roll of papers

and spread the top one out upon the table.

Miss Hannah with a puzzled look bent over the good man's

shoulder and read, whilst tears came into her sad eyes as she

recognised the clumsy writing:—

|

|

£ s. d. |

|

Thomas Branscombe, Esq. (in Memoriam) |

5 5 0 |

|

Miss Susannah Wesley Branscombe |

5 5 0 |

|

Miss Hannah More Branscombe |

5 5 0 |

|

Jane Twizel |

1 1 0 |

Miss Hannah turned away with a chocking sob, and the super,

embarrassed and perplexed, took a hasty departure.

In the small hours of the next morning, as Miss Hannah sat

musing by the sick-room fire, a gentle voice called her to the

bedside.

"What is it, love?" she asked anxiously.

"Oh, Hannah, love, isn't God good? I said He would find

a way and He has done—better than we can ask or think."

"Yes, love! of course, love; but what do you mean?"

"The fund, you know, the great fund; we shall do it, you see,

after all. Oh, isn't He good?"

"Yes, love, of course."

But Miss Hannah's voice showed that she did not quite

understand, and so with a bright smile the gentle sufferer explained

faintly: "The insurance, you know; it is for whichever of us dies

first."

"Dies?" cried Miss Hannah, in sudden distress; "you are not

dying, love. Oh, no! You mustn't leave me alone."

But the sufferer evidently did not hear.

Presently she murmured almost inaudibly: "There will be

plenty of money for you now, love, and the Branscombes will have an

honourable place on the roll, and whilst the money will be making

the world sweeter and better we shall be at rest."

Two days later the gentle soul slipped away and was laid by

her father's side in the Hanster chapel-yard, and shortly after the

Million Scheme was enriched by a contribution of a hundred pounds,

"In loving memory of a noble father and a sainted sister in heaven."

Poor John Crake is still waiting, though somewhat more

hopefully, to be allowed to act as a protection against burglars at

Pear Tree Cottage.

――――♦――――

THE ALDERMAN'S CONVERSION.

SORRY, Mr. Super,

but I cannot take the chair, and as for my name heading the circuit

list, I don't intend it to be there at all."

"Mr. Alderman, I'm astonished! You of all men!

Why, everybody is looking to you to lead the way."

"Can't help it, sir; the fact is, I don't approve of the

scheme at all."

The super was amazed, and most undisguisedly disappointed.

"What! What is your objection to it, Sir?"

And the alderman leaned back a little farther into his

Russian leather armchair, puffed out a volume of smoke from his

cigar, twitched up the tightened knee of his trousers, and then

drawled with an assumption of coolness he did not quite feel:

"It appears to me, sir, that this whole movement is an

attempt to endow our departments, and as a—a—conscientious Radical I

object to all endowments."

The good super proceeded to explain, and from explanation he

passed on to argument and from argument to pleading; but the

alderman held his ground, and the minister went away with

astonishment and dismay in his heart.

Left alone in his office, Joseph Carfax put his legs upon a

chair and gave himself up to meditation, in which the minister and

the Twentieth Century Fund were soon forgotten. The alderman

was a successful man of business, who had risen from the ranks, and

whilst yet in the prime of life had reached a comfortable

competence. He was also one of the most prominent public men

in the ancient borough of Knibworth, and it was confidently stated

that he might have the mayoralty any time he liked. Hitherto,

however, he had declined the honour, chiefly because he was anxious

when he did occupy the civic chair to excel his predecessors as much

in munificence as he was able to do in eloquence. He had a

large and expensive family and many calls upon his liberality, but

he was now beginning to feel that if not next year, certainly the

year after, he would be able to do himself the honour of accepting

the dignity which had already more than once been offered him.

As will have been seen already, Carfax was a Wesleyan and had

been for years a most acceptable local preacher. In his

earlier life, when he was an obscure man, he had been very popular

and very much in demand; but of late his appointments had been

reduced to an occasional half-day at the circuit chapel, and he

scarcely ever went into the villages to preach except on anniversary

days, when his liberal contributions to the collection were more

eagerly looked for than his services in the pulpit. He was

trustee of several chapels and had held every office his Church

could offer to laymen, not excepting that of Conference

representative. For some years now he had been the chief

layman of the Knibworth circuit, and was known throughout the

district as a generous, broad-minded sympathiser with every good

movement.

Of late, however, he had been conscious that the ardour of

his early days had left him, and that he was not by any means as

enthusiastic a Methodist as he used to be. As he mixed more

with men of all kinds his ideas had got broadened he told himself,

and he was compelled to admit that the nonsuch Methodism of his

earlier life did not quite satisfy his maturer tastes. The

ministers they had now were not quite the same sort of men as those

with whom he had been so very friendly in those days gone by, and

the laymen with whom he associated at the chapel were not exactly

his style. His family was growing up, too, and he began to

discover how very little society there was for his sons and

daughters in the Knibworth Methodist circles.

His wife had complained more than once recently that there

were scarcely any young people in the chapel with whom their

children could associate, and none with whom she would like them to

marry. And he felt that his wife was right, although he had

pooh-poohed her remark at the time; really when he came to think of

it, a man in his position had to make many social sacrifices, if he

continued faithful to the Church of his choice. He governed

his family upon what he called "modern principles," and allowed his

children great liberality, both of speech and action. His

growing discontent with his Church had found expression of late in

severe criticisms of sermons and half-concealed sneers at the

officials of the Church; but he was surprised and for the moment

disturbed when he discovered that his children entertained similar

views, and assumed a tolerant, contemptuous air towards all things

Methodistic.

Recently also two of the young people had taken to going to

church occasionally, making their love of music the excuse; and only

the other day his boy Fred had been invited to join the choir of St.

Margaret's.

To crown all, his wife had hinted to him a day or two ago

that there was something between their eldest daughter Emily

and young Pearson, the son of one of his brother aldermen.

Well, after all, what right had he to expect that his

children would be Methodists because he had always been one?

Hadn't they as much right to choose for themselves as he had?

It would be a grand thing for Emily, if she did marry young Pearson,

and it would be a shame for him to put anything in her way.

Perhaps if he became mayor it would help the matter, for the

Pearsons were a proud lot. Yes, that was what he must do, he

must take the chief magistracy next year, and if he did, there would

be no money to spare either for this Million Scheme or any other

merely Methodist matter.

Just as he had reached this conclusion the office door

opened, and in sauntered an old man. He was evidently very

much at home in the place, and nodded familiarly to the alderman as

he entered. He was short and thin and very straight; he wore

an old-fashioned semi-clerical suit of black, tinged here and there

with brown spots, the result of snuff-taking.

"Hello, dad! pay day again?" And the alderman rose

hastily from his reclining position and, drawing up to his desk,

began to take out his cheque-book.

The visitor was Carfax's father, an old local preacher who

lived by himself and was maintained in very generous fashion by his

only son.

"Yes, my lad, the old amount," he said playfully, as he came

towards the desk; "but I want something else to-day."

"Hello! what's up now?" cried the alderman, turning round and

smiling. "Not going to get married again, father?"

The old man grinned, for this was an old joke. "No, my

lad, it's that Twentieth Century Fund, you know."

Carfax laid down his pen, and turning quickly round, cried

"But, father, you are not going in for that, surely."

"Am I not? but I am! And why not?"

"I don't believe in it, father. You can do what you

like and have as much as you like, but I've made up my mind that I

shall not give a penny to it."

The old man's jaw dropped in dismay. He looked amazedly

at his son for a moment, took a great pinch of snuff without ever

removing his eyes from the alderman, and then gasped out:

"Thou's wandering, my lad."

It was a sure sign that he was excited when old John Carfax "thoued"

his son.

"Wandering or not, I mean it. I'll supply you with as

much as you like, with pleasure but not a penny will I give myself."

"But, my lad, my lad! it's for Methodism, our blessed

Methodism!"

"Methodism! What's Methodism? It's no better than

any other Church that I know of."

"Joseph!" and in his extreme distress the old man dropped his

snuff-box, and coming up to the desk and taking his son by the arm

he went on, "Joseph, my lad! my lad! why, Methodism has been

ivverything to uz."

"Don't see it, father; I don't see it at all."

The old man's arm was still upon his son's shoulder, and, as

he stood gazing up into the hard but handsome face of his only

living relative, he asked with eager, tremulous distress: "Joseph,

hev'n't I heard thee say at anniversaries 'at thou hed the best

mother i' England?"

"Yes, an' I had, too; but what of that?"

"That mother was saved from a bad family and a bad life by

Methodism; and thy owd father was turned from a gamblin'

skittle-player to a local preacher by Methodism; an' all 'at's good

in thee thou got fro' Methodism. Oh, Joseph! how can

thou talk like that?"

Carfax was moved somewhat, and so, promising to think of it,

he put the old man off, and as soon as he had gone tried to forget

the words he had heard in the public duties in which he was so much

interested. But again and again at the Watch Committee that

night the old man's look came back into his mind, and even when he

got to the club he could not shake off the impression that had been

made on him, and so he went home earlier than usual. He hard

just finished supper and was immersed in some corporation returns

when the dining-room door opened, and in burst Dick, his third and

most excitable son.

"Oh, dad! I've been to such a jolly meeting. Went

over to call on the Brigdens on my bike. They were just going

out to a meeting, so I went with them and heard Perks. My

stars, didn't he make a rippin' speech!"

Carfax glanced round indolently and asked: "Missionary

meeting, was it?"

"Missionary! No! it was about this Million Scheme.

Hay, I did feel proud that our Church was such a grand one."

And then he broke off: "I say, dad, why don't we take in the

Methodist papers? The Brigdens knew all about it, and there

was I as ignorant as a noodle."

Carfax felt a reproachful little pang, and was just turning

again to his returns when his impetuous son broke out once more:

"Oh, it was a speech! Why, dad, I never knew

that ours was such a grand Church. Oh, wasn't I proud I was a

Methodist, I can tell you!"

Carfax winced and was just about to speak when a little

flaxen-haired maiden, the saint of the family as her eldest brother

called her, got up from the sofa where she had been reclining, and

stealing to her brother's side, put her white arms upon his shoulder

and said softly: "I hope you will be a real Methodist some

day, dear."

Later the same evening the alderman had a somewhat serious

conversation with his wife. He was going to tell her what he

had decided to do with regard to the Million Scheme and what he had

said to the super whom Mrs. Carfax did not particularly like; but

before he could commence she began to confide to him her

apprehensions as to their eldest son, who was in business in London;

and the details she supplied, and the dark pictures which, with

motherly anxiety, she painted, made Carfax very uncomfortable.

When she had gone to bed he fell into troubled musings.

He could not forget what his father had said to him that day, and

the light words of the excitable Dick somehow stuck to him; but this

news about Edmund in London was worst of all, and sank deepest.

True, most of what the mother had said had been mere surmisings; but

he felt how easily they and much more might be true, and before he

was aware of it the alderman, who had of late dropped into the habit

of mentally minimising the favourite Methodist doctrine of

conversion, found himself wishing, with a deep sigh, that his eldest

boy had been converted before he went to London. He would give

a thousand pounds at that very moment to know that his boy was a

genuine Christian; but there seemed no hope of that, and his other

children seemed likely to become nominal Christians at most, and to

drift into other Churches. And for the next half-hour—the

deeper manhood of Joseph having fairly awakened—gave him a torturing

experience.

But next morning he felt inclined to laugh at his fears of

the night before, and was no more inclined than ever to depart from

the path upon which he had entered.

But circumstances were against the alderman, for when he got

home to dinner he found that two of his children, Dick the

irrepressible, and Kathy the saint, had been down to grandfather's

and borrowed the Recorder and had also called at the railway

bookstall and got the Methodist Times, and were now fuller

than ever of the wonderful fund.

When grandfather came in a little while afterwards they of

course received powerful reinforcement, and though the two eldest

children who were at home treated the matter rather contemptuously,

they could not altogether resist the influences of the moment, and

were soon almost as much interested as the younger ones.

On the following Sunday it was announced that the Million

Scheme meeting for Knibworth would be held on the Thursday week

following; but no chairman's name was mentioned. Literature of

various kinds was also found in the pews and carried home, and

Carfax during the afternoon noticed some very mysterious

calculations going on with lead pencils, and his wife told him as he

went to bed that, good Sunday though it was, Dick and Kathy had been

reckoning up what sundry inmates of the house owed them.

Carfax began to feel really ashamed of himself, and told

himself reluctantly that the enthusiasm of his children, the younger

end of them at any rate, was a direct reproach to him; at the same

time he was conscious of a curious feeling of relief and

thankfulness in the thought, that some at least of his family would

by this fund become more firmly attached to their father's Church.

During the week the super called again, and tried to induce

his most influential layman to take the chair at the circuit

meeting. But Carfax still held out, though more from a foolish

scruple about consistency than anything else and the minister went

away resolved to try once more before the eventful day came.

Of late Carfax had fallen into the habit of once-a-day

worship, and so he stayed at home on the following Sunday evening.

And there, by his own fireside, he got thinking once more of his

cherished plans, and was surprised to find that they did not seem so

beautiful as they had done before. And then he was drawn to

think again of his whole life, and especially of his recent attitude

towards the Church in which, as he could not but acknowledge, he had

got all his good. Then he wandered off into remembrances of

the happy days when he was young and struggling, and of the blessed

weariness he struggling to feel after a hard day's preaching in the

country. After all, those were happy days, and he was not so

sure that he was not a better man then than now, in spite of his J.

P. and municipal and other honours.

Then his father's words in the office came back to him, and

he was just choking back a lump in his throat when the dining-room

door burst open and a fairy form flung itself upon him, a hot cheek

was pressed against his, and a bright eager voice cried: "Oh,

father, father! what do you think? Oh, I am so happy!

so very very happy!"

"Whatever's the matter, child?"

"Oh, father! dear father, Dick's just told me such a secret!

such a beautiful secret."

"And you are letting it all out! What is it, you

whirlwind?"

"Oh, father, Dick's just told me he is going to join Mr.

Jimpson's class. Isn't it grand, father, glorious?"

Carfax felt he was giving way. The slumbering Methodism

in him was all at once awaking and swallowing up the alderman, and

almost to his own surprise he muttered fervently: "Thank God."

It was many a long day since Carfax had had a religious

conversation with one of his children, but that night he took young

Dick into the study and asked him what Kathy's strange story meant.

Dick was frankness itself, and the alderman's heart grew warm

and his eyes moist as he listened to his own boy telling the old

story that he once used to hear so often.

"Well, my dear lad, it's the best news I've heard for many a

day. God bless you, and make you a true Christian and a true

and faithful Methodist. Ah—there's one thing I should like you

to do, however."

"What's that, father?"

"I should like you to write to Edmund before you go to bed,

and tell him what has taken place."

On the Wednesday following, when the family came down to

breakfast, there was a letter lying on Master Dick's plate, and the

alderman who saw it first felt somehow as if he would like to open

it.

Kathy also looked at it with longing eyes, for the absent

brother was her special favourite.

Presently Dick came down and opened his letter. He had

dressed hastily and was not too much awake even now; but as he read

the note his eyes opened and a bright light came into them, and

suddenly he flung the letter into the air, and cried: "Hurrah!

I mean, Praise the Lord."

"What! What is it?" cried two or three at once.

In a moment little Kathy had slipped from her place at the

table and picked up the letter, which had fluttered down upon the

hearthrug. "Listen! listen!" she cried, with shining eyes and

radiant face, and whilst the rest looked at her eagerly she read:

"DEAR DICK,―Thank

God for the news you send me; it is the best I have had for many a

long day. May the Lord keep you faithful! You may be

surprised that I write like this, but as you have told me your

happiness I will tell you mine. I have not been very good, I

am sorry to say, since I came to London; but a fortnight ago a

friend asked me to go to St. James's Hall. I went, and what I

heard there changed my life; and that very night I gave my heart to

God. Please tell them all, but especially dear

little Kathy. With much love,

Your affectionate Brother,

"EDMUND."

"And the £250,000 for Hugh Price Hughes' work was my special

aversion," said the alderman to himself, as he went down to his

office; and when the super called an hour later he found his

hitherto obdurate layman in a very kindly frame of mind. The

next evening the chair was taken by Joseph Carfax after all, and the

fame of the Knibworth contribution has gone forth into the whole

Church.

|

|

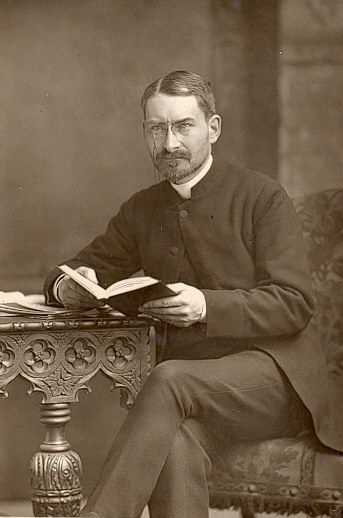

Hugh Price Hughes

(1847-1902)

Founder of the Methodist Times and

first

Superintendent of the

West London Methodist Mission. |

|