|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XX.

DOUBTS AND FEARS.

BUT Doxie could

not get rid of Sam's peculiar look, and she was confirmed in her

fears about it next morning, when he came into the parlour through

the front door and handed her a circular containing a long address,

signed at the bottom by Andrew Barber. Sam made a most

grotesque attempt to appear unconcerned as she stood reading the

document; and when, she had done, he pulled out of his pocket a

Manchester paper doubled down at a place where there was a report of

a speech which Andrew had been making on the industrial crisis.

Doxie felt she was blushing, and raised her head to search Sam's

face; but that worthy looked as blank as a stone wall for a moment,

and then, puckering his face into a series of most extraordinary

contortions crowned by a sort of encyclopædic wink, and followed up

by a succession of emphatic nods, he turned hastily round and

vanished. Doxie felt like a person who is slipping over the

edge of a precipice: her secret was discovered, Sam Speck knew it,

and others very soon would. And then she began to wonder

whether it would really matter very much if people did know.

Her uncle would be furious, but even his wrath was better than the

miserable sense that she was deceiving him; and when she explained

to him that it was a secret hidden in her own breast, and that she

had no intention of ever accepting Andrew, perhaps he would not be

very hard upon her. Well, she would see; and if the worst came

to the worst, she felt sufficient confidence in her power over her

cross-grained relative to think that all might be well. As the

day wore on, however, she was conscious of a soreness in the throat;

and when her uncle came in to dinner and caught her hoarse tones, he

sent for the doctor, and she was ordered off to bed, where she

stayed for nearly a week.

One day, as she lay dozing and listening dreamily to the

clack, clack of the workpeople's clogs as they returned to their

work, it seemed to her that the sounds lasted longer than usual, and

presently her mother, who was in the room, got up and went to the

window, and almost immediately cried out, "Goodniss! Wot'sup?"

Doxie turned her face towards the window, and asked drowsily

what was the matter.

"Matter! ther's a craad o' men gooin' past wi' Andrew Barber

i' th' middle on 'em lewkin az peeart as a sparrow."

In a moment Doxie was out of bed and at the window; but the

crowd had nearly got past, and she only saw stragglers, who came

hurrying from all parts of the village. Then she saw Sam Speck

come across to the shop, and a moment later he and the clogger were

seen hastening towards the mill gate. The mill could not be

seen from the window, and Doxie, consumed with curiosity and ill

with excitement, gave a little groan of despair. Her mother at

once insisted upon her getting back into bed; and as she could

scarcely stand for trembling, she obeyed, and buried her head in the

bedclothes to try to shut out the fearful thoughts that were

crowding into her brain. Then she heard shouting and cheering,

and when all was quiet again thought she could hear occasionally the

sounds of a man's voice. She guessed only too well what was

taking place, although she had never witnessed such a scene.

The street outside was still now, and nothing could be heard but the

dim, far-off voice, that grew fainter and fainter; then more

cheering, and presently one great burst of shouts; and then she

heard clogs again, and the wearers were evidently running. A

minute or two later she heard her uncle's voice outside raised in

excited debate, followed by the shuffling of many clogs in the shop;

and when she had sent her mother downstairs to see what was the

matter she had to hold her beating heart. Her mother seemed a

long time in returning; but at last she brought the alarming tidings

that the minders and spinners had been holding a meeting in the open

air, winter though it was, and that Andrew Barber had been

addressing them, and as a result they had decided not to return to

work, and were now on strike.

Doxie never saw her uncle until late that night, and when she

did he had words to say about Andrew that went to her heart; and the

first day she went downstairs she ascertained that the Duxbury

minders had come out in sympathy with their brethren at Clough End

and Beckside, and that the other branches of the trade were

preparing to follow the same course.

It seemed to Doxie as if the life of the village had

undergone a sudden and serious change. The hum of the mill, to

which they were all so well accustomed, was no longer heard, and it

sounded like perpetual Sunday. The triangle opposite the

clog-shop was dotted all day with little knots of workpeople

discussing the situation and hearing or telling the latest

developments of the crisis; whilst the shop itself was so

inconveniently crowded, that, what with the embarrassment thus

occasioned, and the fact that Jabe and one or two others of the

chapel people were in a decided minority in the discussions, the

clogger was in a constant state of irritation, and never lost an

opportunity of denouncing Andrew as the originating cause of all

these troubles and inconveniences. As she became convalescent,

Doxie took every opportunity which presented itself of hearing the

arguments; and it soon became clear to her that her lover was little

less than a hero to most of the men, and that her uncle and those

who thought with him had little or no support. As time passed

on and the strike continued, Sam Speck, between whom and herself a

sort of secret, unacknowledged understanding seemed to have arisen,

brought her first one bit of strange news and then another.

One day he came into the parlour, and informed Doxie that he had

just heard that since the strike commenced Andrew had not taken one

penny of wages from the association which employed him, and that a

man who lodged in the same house had informed him that he was living

on thick porridge. Another day he called her aside as she was

coming back from a meeting at the chapel, and told her that Andrew

had sent money to a local committee at Clough End to help to support

the poor people, who were already beginning to feel the pressure of

lack of food. These items were very sweet to Doxie, and she

found them very acceptable antidotes to the bitter things that were

being said every day about Andrew by her uncle.

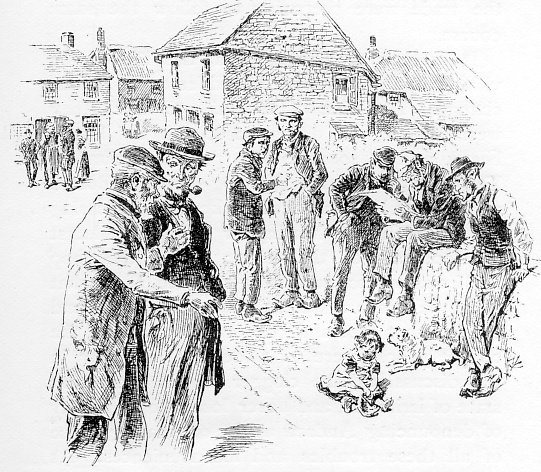

Discussing the situation.

As the results of the strike began to manifest themselves in the

distress of the poorer part of the inhabitants of the village, Doxie

began to make little efforts herself to try to meet the needs of her

suffering neighbours. As time went on, and there seemed to be

no prospect of the struggle coming to an end, it occurred to her to

try to organise some more adequate means of assisting the now

starving workpeople, and she had already spoken to the doctor's wife

and Nancy at the fold farm, when she was amazed one day to receive a

letter from Andrew suggesting the very thing she had been thinking

about, and inclosing a five-pound note as a nest-egg for the fund

required. In a few days she and her friend had established a

soup-kitchen at the chapel; but Doxie was surprised to find that her

uncle peremptorily and in his surliest manner, refused to

contribute, yet she was touched and somehow felt reproved when Long

Ben insisted on contributing about three times as much as she had

expected from him.

Doxie's philanthropic activity did her good, and came as a

blessed relief to her torturing thoughts. Every now and again,

however, she had sudden and painful relapses. What if Andrew

should have been wrong after all? What if, after this long

struggle and all this suffering, the poor workpeople should be

compelled to surrender? Their condition would then be worse

than ever; and she had learnt enough lately of human nature to know

that all the obloquy would be laid upon Andrew, and Beckside would

curse his very name. And then her own position would rise up

before her: how wicked it was to be concealing her secret from her

uncle and her mother, and how unchristian to nurse and cherish

within her heart an affection which she could never gratify; for,

deeply though she acknowledged she loved Andrew, the thought of

sacrificing her religion to him never came into her head, neither

did she allow herself to debate the question as to whether she could

marry Andrew and still retain the favour of God.

Once or twice when she had felt unusually despondent, she had

been tempted to unbosom herself to her uncle; not that she thought

he could help her, but that he seemed to be the person against whom

she was sinning. So the weeks rolled slowly by, and the strike

continued, without the least promise of any settlement. And

now Doxie began to realise some of her fears. One by one the

frequenters of the clog-shop came over to her uncle's way of

thinking, and gradually Andrew's name began to be mentioned in hard

and bitter terms. His youth, his consequent ignorance, and

inexperience, and his past peculiarities were sullenly canvassed;

and the moody, ill-fed men began to openly abuse the man they had

before idolised. But the women were much worse than the men.

Doxie heard that Mrs. Ben, Andrew's mother, could not go out for

fear of having the iniquity of her son flung at her; and one day,

whilst she was serving out the soup, a woman from the brick croft

cursed Andrew in such language as Doxie had never heard in her life

before. Then she began to imagine that Sam Speck was deserting

her. He scarcely ever came near her, and when he did he was

most disappointingly vague in his information, and she soon surmised

that the only news he had to tell was so unpleasant that he

preferred to incur her displeasure rather than utter it. This

fear was confirmed when she began to pick up here and there little

hints that Andrew was suspected of "ratting." The cotton trade

was very good at that time, and the masters were known to be much

pressed to execute orders; so much so, in fact, that there was the

possibility that they would not be able to hold out much longer, or

if they did they would not do it unitedly. Then news reached

Beckside that one or two of the smaller mills had given in and

conceded the men's demands, this being followed by the much uglier

news that others were introducing "knob-sticks" into their works,

and "running" in some kind of fashion in spite of the strike.

Hardly had Doxie digested this piece of news when the inexplicable

but apparently well authenticated information came that Andrew was

suspected of secretly being in the masters' pay, and of sympathising

with and protecting the obnoxious "knobsticks."

In her distress Doxie fell back upon her one woman friend,

and during these sad times went at least every other day to

Beckbottom. These visits were all the more comforting to her

from the fact that Leah stoutly maintained her faith in her brother,

and became more emphatic in her indorsement of him as she grew more

and more unpopular with the rest of the villagers. Luke,

Leah's husband, also stoutly defended Andrew, although he chafed

exceedingly under his enforced idleness, which was, however, only

partial; and Doxie was quick enough to note that he not only

retained and even increased his faith in his brother-in-law, but

asserted that he was as wise as he was honest, and would eventually

turn out to be right. This sympathy warmed Doxie's heart

towards the young couple at Beckbottom; and one day, when she felt

unusually sad and in need of sympathy, she blurted out sufficient to

open Leah's eyes as to the state of her affections, and she, after

expressing great joy thereat, assured Doxie that all would yet come

right. Upon this Doxie introduced the religious difficulties

that were involved in the case; but Leah had a word of comfort for

that aspect of things also. She told Doxie of the conversation

she had had with Andrew, and of his declaration that he was not an

atheist or ever had been, and she added several very acceptable and

comforting details about Andrew's character; and then, with a

passionate little parting hug, told her friend that she had been

praying for her brother for years, and exhorted her to do the same,

assuring her that God always had answered her petitions, and that He

surely would in this case also. Doxie dried the soft tears

that had unwittingly risen into her eyes, and fervently thanked

Leah; and then, after begging her to keep her secret from everybody,

and especially from Andrew, she left for home. Here she met

her uncle in a state of great excitement; for Long Ben had been to

the cloggery that afternoon for the first time for weeks, and had

sat like a log for hours, until, goaded by something which was said,

he had uttered sentiments that were almost blasphemous, and had

announced that he intended to sell up and leave the neighbourhood

where so much shame had come upon him, and where one of his had

inflicted so much suffering on his fellow-workmen.

This was bad to bear, Doxie felt, and it took all the new

courage she had got at Beckbottom to endure it without an outburst;

but, however disheartening, it was nothing to what almost

immediately followed, for news came next day that things had reached

a terrible pass in Duxbury, and that Andrew was in open conflict

with his co-workers upon some point not quite clear. A few

more anxious days followed, during which Doxie was strongly tempted

to write to Andrew and beg him, if he had any such regard for her as

he had so often declared, to give up this terrible struggle, and

bring peace back to the neighbourhood. Before she could bring

herself to do this, however, it became too late; for early in the

following week Sam came running to her with a face as white as the

tablecloth she was folding, and informed her in breathless, choking

tones that there was a riot at Duxbury, and that the military had

been sent for; and ere she had recovered from this she learnt that

Andrew had been very prominent in the riot, which had been roughly

put down, and that her lover was in prison, and would next day be

brought before the magistrates.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXI.

A GREAT FIGHT.

IT is altogether

beyond our power to describe the scene at the clog-shop when the

awful message Sam brought became known. In two or three

minutes the place was crowded to the doors, and numbers of the

unemployed were standing outside discussing the situation.

Doxie, who had almost fainted when Sam informed her, could now hear

the growls and curses of some of the rougher men; and the women, who

seemed more excited than their husbands, flung about scathing and

horrible denunciations of Andrew and all his works. Inside the

shop everybody was talking at once, and Sam was almost worried when

he defiantly took up cudgels for the absent young agitator.

Jabe stood still in the middle of the shop, and seemed incapable of

speech; but when the talk became general, instead of joining in it,

he hastily made his way to the door, and was soon seen posting off

to Long Ben's, with his ordinary limp painfully exaggerated by his

excitement.

Here another amazing thing presented itself. As Jabe

went up the little front garden he could hear a woman's voice raised

in high, strident expostulation; and entering the open door he

caught sight of Ben sitting in a state of collapse in his chair,

whilst his wife was standing over him with red face and angry tears:

for the sudden and awful tidings had at last reached the mother in

her, kept down so long by prejudice and misapprehension; and she,

now that there was something really to be ashamed of and to mourn

over, had suddenly turned completely round, and was defying either

her husband or anybody else to "dar" say a word against Andrew.

But Jabe was too much excited to think of discretion, and in a

moment he had plunged into the discussion with his usual

impetuosity. He found more than his match, however; for though

he excelled himself in the fierceness of his denunciations, Ellen

Barber flung them back at him with interest, and poor,

broken-hearted Ben had at last to interfere to prevent worse

happening.

Meanwhile Doxie had rushed upstairs as soon as Sam left her;

and notwithstanding the shouts and angry cries of those outside, she

presently found time to think. She had suddenly become a new

woman. The terrible news she had just heard had swept before

it all doubts, fears, and hesitations; she knew exactly what she had

to do, and had only to decide how best to do it. Andrew, the

perplexing and singular young man, who held strange views and

suffered for them, might be left to himself and kept at arm's

length; but Andrew the slandered and mobbed prisoner, hated by every

one and utterly without a friend, was quite another thing, and all

cause for hesitation at once vanished. All the world had left

him; then her place was by his side. He was baffled, beaten,

and utterly deserted; then it was hers to succour, comfort, and

honour him. Her uncle? What he thought and said about

the matter now seemed so trivial a consideration, that she wondered

she could have been so long and so much influenced by it. Her

religion? Why, if anything was religion, surely it was to

stand by the deserted, befriend the friendless, and support a noble

action, however grossly it might have been misrepresented; for in

this moment Doxie did not doubt for a single instant that Andrew's

motive had been a heroic one. It did not take her long to

decide; it was so delightful to realise that the time of patient

endurance and waiting was over, and that the time for rapid and

decisive action had come. In a few moments she was flying away

to Beckbottom, where, bursting in upon Leah with her dreadful news,

she almost frightened the baby out of its senses. She grew

impatient and almost angry with Leah because the news had so stunned

her that she was incapable of anything but lamentations and tears.

Luckily Luke came in just then, and Leah grew calmer, and the three

began to discuss what must be done. There was no holding

Doxie; nothing but the promptest action would satisfy her.

Luke must go off to Duxbury at once, engage a solicitor, and bring

back all the news. Then he must get a trap from Clough End to

take them to the town next morning; because, she reasoned, everybody

will want to go to-morrow, and we shall not get a seat in the coach.

Then she decided that there would be nothing but trouble and

opposition if she told her uncle, so she would leave him to find

out, and thus be untrammelled in her movements. And then, yes,

she would meet Luke at the four road ends, and they would go round

by the Halfpenny Gate, and so avoid the possibility of being seen,

or even stopped. She talked in such a torrent that Luke was

bewildered; but there was no resisting her, and in a short time she

was on her way back, with all her arrangements made and her mind in

a complete whirl of excitement.

It was harder, after all, to meet her uncle then she had

expected; for he had got beyond anger now and was full of most

sorrowful concern for the carpenter and his family in their great

trouble. It struck the clogger once or twice that his niece,

usually the most charming of listeners, was strangely inattentive to

his utterances; but he soon forgot so small a matter, and spent the

whole night in heated discussion at the shop fire. It would

have been well for Doxie if she could have slept that night, for in

those terrible small hours of the morning she had an unexpected

struggle: every reason that love and respect for her uncle's wishes

could urge came up before her, and every objection to the course she

had decided upon which womanly delicacy could suggest rose before

her mind, and sometimes seemed about to overwhelm her; but whenever

that point was reached in those long, painful debatings, the sudden

vision of Andrew sitting in his lonely cell immediately blotted out

everything else, and she went downstairs next morning fully resolved

to go through with the plan she had adopted. The clogger made

a hasty breakfast, for friends were already waiting to resume the

absorbing topic of the hour; so Doxie was left to herself earlier

than usual. Dressing as quietly as possible, she stole out

into the back garden, climbed over the fence in a most unladylike

fashion, and was soon speeding past the chapel towards the four road

ends.

It was nearly eleven o'clock when they reached Duxbury; and

as they drove into the square in which the town hall stood, they

discovered that it was already nearly full of people waiting for the

court to open. Doxie had come for the express purpose of

getting into court, and she had comforted herself with the thought

that if Andrew saw her it might cheer him in his painful position.

But Luke soon ascertained that the court was already full of people

who had got special permits, and that it was useless to try to

enter, as they might get crushed in the attempt. This was a

great disappointment; however, as Luke suggested they should retain

the horse and trap so as to be above the heads of the crowd and thus

see what took place outside, Doxie was fain to consent, though she

did it with tears of regret.

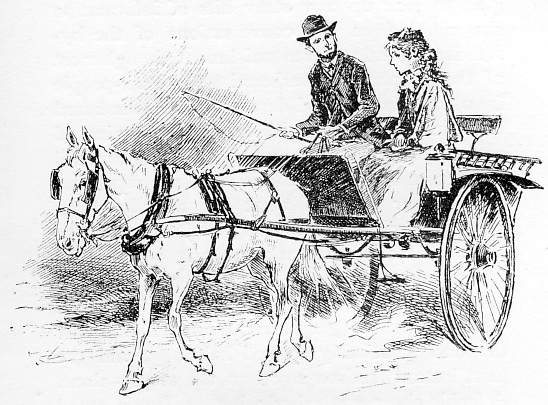

It was nearly eleven o'clock when they reached

Duxbury.

Luke had gained much information about the arrest of Andrew

and the circumstances connected with it, but for his own reasons he

had told very little; so, as Doxie sat in the trap, a prey to all

sorts of apprehensions and trembling at her own daring conduct, she

was glad to pick up any stray bits of information she could from the

conversations of the bystanders. And to her astonishment,

though most of the people she overheard were work-people for whom

Andrew had dared so much, she heard his name mentioned in bitterest

terms again and again. This was incomprehensible to her, until

she remembered that this was only a repetition on a larger scale of

what had already taken place in Beckside; and she was just turning

to Luke to make a remark about it, when there was a sudden shout,

all eyes were turned in the direction of the court-house door, and

the crowd went forward to get nearer. Then Doxie saw the door

cautiously opened half way, and the next instant Andrew stood on the

steps—alone. A feeble cheer was raised; but as Doxie stood up

in her excitement, this cheer was suddenly drowned in a perfect roar

of execration. Doxie's eyes were fixed on Andrew, and as soon

as he heard the reproachful cries of "Knobstick," "Traitor,"

"Ratter," etc., he turned round and faced the cursing crowd.

Wavering a moment, he suddenly darted forward, made for a lorry that

was standing in the midst of the crowd, and before the swarm of

execrating men and women had grasped what he was going to do, he had

climbed into the vehicle, and, lifting his head, turned a stern but

immovable face upon the people. Then three or four men made a

rush at him, and Doxie screamed, and jumping upon the seat of the

trap began to call out to the people. Just at this moment,

however, as the men got near her lover, she saw Luke, who had left

her side, rush up to the lorry and stand beside it, with the evident

intention of defending Andrew. To her astonishment, Luke was

joined by Nathan and Sam Speck, and, marvel of marvels, Long Ben

himself! These, standing round the lorry, looked rather too

ugly to be tackled, so the men fell back; whilst Andrew, taking off

his hat, stretched out his hands and began to speak.

|

|

Doxie could not catch what he was saying but it was easy to see that

he was facing enemies, and was not afraid of them. For the

first few minutes the young man's voice could scarcely be heard for

the interruptions, and again Doxie heard "Traitor" and "Knobstick."

Andrew, however, was not to be daunted. Steadily and without

unduly lifting his voice, he spoke, and presently the interruptions

subsided; and now and again a feeble cheer arose, which was always

drowned by the angry roar that followed it. It soon became

apparent that Andrew was making converts, whatever he was pleading

for; and after another five minutes he paused, jerked his thumb in

the direction of the Concert Hall at the bottom of the square, and

immediately got down from the lorry and began to move towards what

was evidently a new rendezvous. Upon this Luke came back to

Doxie, and declared that Andrew was doing the maddest thing under

the sun: he was going into a hall with that rough crowd, all of whom

hated him, and he might easily be trampled to death under their

feet.

Doxie immediately urged Luke to go and get her other Beckside

friends and see if they could save the reckless Andrew; and away

they went on their errand, Sam and Nathan turning to nod with

surprise at her as they hurried away, for it was evident that Luke

had told them of her presence.

Standing up in the trap, with white, drawn face, and hands

clasped before her in nervous apprehension, Doxie watched the crowd

swarming towards the Concert Hall. All kinds of horrible fears

passed through her mind, and she was just uttering a low cry, when

she heard herself called "Miss Dent! Miss Dent! You

here!" and, turning round, she saw old Mr. Wragge standing on the

curbstone, and calling to her in tones of anxiety.

"Oh, Mr. Wragge, will they hurt him, do you think? Will

they hurt him?"

The old man, whose quiet face wore at the moment a look of

curious inquiry, came close to the side of the trap and said

soothingly, "No, my dear. No! that young man's their master,

only they don't quite know it yet. But why are you here?

Is he――"

But Doxie had jumped hastily out of the trap, and was

standing by his side.

"Tell me! tell me all about it," she cried eagerly.

For a moment or two the old man tried to comfort her, all the

while watching her face as if to ascertain why she was so deeply

concerned in what was taking place; and then, having apparently

satisfied himself, he smiled gently and began to talk. Slowly,

and with many interruptions from his excited listener, he told the

story. It seemed that Sam had rather exaggerated in calling

the disturbance of the evening before, a riot; but Mr. Wragge

admitted it might easily have become one, and, in fact, probably

would have done but for Andrew's interference. The strikers

were furious with the "knobsticks," and had threatened violence

against them; and here for the first time Andrew had opposed his

supporters, and insisted that, whilst every moral means possible

should be used to persuade the imported workpeople to cease their

opposition, nothing in the shape of violence should be attempted.

His brother leaders had opposed him angrily, and it seemed as if the

strikers were drifting towards an open split. Then some of the

rashest of them had taken to "picketing," which Andrew denounced as

cowardly and brutal and un-English.

This kind of struggle had gone on for several days; and the

evening before, hearing that there was a plot to mob some of the

"knobsticks," Andrew had gone down to the gate of the mill where the

deed was to be done, and had done his best to persuade his followers

to desist. Before he could accomplish his purpose, however,

three or four of the imported workmen came out of the office door,

and a moment later they had been attacked by some of the strikers.

On seeing this, Andrew at once plunged into the thick of the

mêlée, and it was whilst he was thus engaged that the police had

appeared upon the scene and arrested those they found actually

breaking the law; but as the alarm was given in time, everybody

bolted save Andrew, who was pounced upon and arrested. To

complicate matters, Wragge explained, the masters had a day or two

previously made a private offer of a settlement, and Andrew thought

that the terms quoted were fair and reasonable; but the rest of his

fellow-leaders, some of whom Andrew suspected of having "axes to

grind," insisted upon holding out for the last fraction of their

demands, and contended that the offer, being private, should not be

made known to the workpeople. Both these ideas were repugnant

to Andrew, who, in fact, had seen so much to disgust him in the

motives of some of his co-leaders that he was not able to conceal

his contempt of them, and consequently had exasperated them by his

uncompromising attitude.

Affairs had reached this juncture when the fight and arrest

took place. The magistrates had acquitted Andrew after a very

brief examination, the police themselves confessing their mistake;

and now he was engaged not in defending his conduct in the matter of

the "knobsticks," but in an endeavour to persuade the workpeople to

bring the strike to an end. His opponents, however, had been

very busy, and the groans which Doxie had heard were the indignant

cries of men and women who had been told that Andrew was "ratting"

and had been bribed by the masters, but who as yet knew nothing of

the offer that had been made for a settlement.

Just as the old man finished his explanations a great cheer

was heard coming from the Concert Hall, and, stopping a man who was

running by, Wragge ascertained that after a long and terrible

conflict Andrew had prevailed, and that the Duxbury operatives had

decided to return to work if their fellows in the district could be

prevailed upon to do the same.

There was light and hope in the faces of those who passed

Doxie and her friend, and she now heard men expressing themselves as

extravagantly in Andrew's praise as they had done in blame not more

than half an hour before. Then Sam and Nathan came running up;

and the former, who looked as if he had tidings that were worth a

universe to hear, stepped up to Doxie and cried, shaking her arm in

intense excitement, "See yo' yonds the best bit o' flesh an' blood

az iver coom aat o' Beckside. Pluck! When Aw seed yond'

slip ov a lad stop up an' face aw yond' yowling, folk Aw skriked aat!

Aw cudna help it. Talk! seyo he con just make em dew wot he's

a moind, that wot he con dew."

But at this moment Doxie caught sight of a tall form coming

across the market-place, and a thrill went through her; for the

approaching man was Long Ben, whose face wore a proud, uplifted

look, and by his side, looking very small in comparison, was Andrew.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXII.

ANDREW'S VICTORY.

AS the Barbers

drew up Doxie was conscious of sudden and painful embarrassment; her

heart came into her mouth, she felt herself blushing violently, and

the hand she held out to Andrew trembled as he grasped it. He

seemed neither surprised nor particularly pleased at her presence,

and as the others began to talk he ranged himself by her side and

murmured anxiously "This is no place for you."

"Yes, it is," she replied impulsively, whilst her great eyes

flashed. "This is exactly my place."

Andrew looked really perplexed now, but just then Sam

mentioned the question of dinner, and suggested an adjournment to

the Blue Bell, which was kept by a distant relative of his.

Andrew seemed to hesitate; and Doxie, realising all at once that she

was the only woman amongst a company of men, drew nearer to Luke,

and they all began to move towards the inn. Andrew was walking

behind, apparently still debating something in his mind.

Suddenly Doxie turned round, and, waiting for her lover, placed

herself by his side and sent a thrill through him by slipping her

arm into his. Andrew nearly stopped in his amazement; but as

she gently pulled him along, he followed the others, and a moment

later they all came to a stand opposite the Blue Bell, where, as

they noticed the young folk, Sam and Nathan turned to each other

with glances of significant intelligence, and Long Ben became

suddenly absorbed in a careful scrutiny of the signboard. Here

old Mr. Wragge took leave of the party, declining an invitation to

dine with them; and as the others made for the door of the inn,

Doxie drew Andrew back a moment until they had all got inside and

she and he were alone on the flags. Then her courage suddenly

failed her, and she felt like sinking through the ground. She

was going to do an awful thing there in the broad daylight, in the

open air, with strangers passing by and her friends watching them

from the upstairs window—she was going to do what no woman ought to

do. But it was only for a moment, she braced herself up.

She had come to do it and she would not give way now; and so, with a

nervous glance around and a blush that reddened all her face except

her white quivering lips, she said, "Andrew, do you remember Peggy's

stile?"

Andrew raised his head, a look of passionate eagerness came

into his black eyes, followed almost instantly by one of gathering

alarm, and then he cried, "Remember it! Shall I ever forget

it? But, Miss――"

But Doxie was speaking again.

"You asked me a—a—something then, Andrew."

And Andrew, struggling between delight and great fear, cried

again, "Yes, but, Doxie, everything is changed since then."

And as he paused and gazed at her with a wondering exultation that

thrilled and yet frightened him, she bent her head, and whilst her

face was covered with fresh blushes and her voice trembled with

timidity she said:

"And I have changed too."

"Doxie!" cried Andrew, almost in a scream, "don't! Oh,

don't! You mustn't! It is cruel! It is heaven and

hell in the same breath." And then with a sudden soberness he

went on "Don't you know that I am now a jail-bird that my

fellow-workers are all cursing me; that in a few days, unless God

intervenes, I shall have men's blood on my soul, and that this

country will be too small for me?"

And as he stood back looking at her with a wild, despairing

look, Doxie presently raised her eyes to his, and with a glance of

proud, passionate admiration she replied, "That is why I've changed

my mind, Andrew, that is why I am here."

"No, no, no! You must not! You shall not!

I'm ruined, Doxie; I've failed, I've disgraced you――" But here

they both started guiltily, for Sam Speck was knocking upon the

window upstairs for them to come to dinner. "My dearest girl,"

Andrew went on, looking at her with a passion of love and sadness in

his eyes, "I love you this moment a thousand times more than I ever

did before, and for that reason I cannot listen to you; for I must

not, I must not marry you."

And Doxie leaned forward until she almost touched him, and

then, with her grey eyes swimming with tears, she replied, whilst

love and archness shone through the tears, "Then I will marry you,

Andrew, and be ruined along with you;" and then she turned and led

the way into the tavern, whilst her sweetheart, in a whirl of

rapture and fear, silently followed her.

It was a very odd party that sat round the table in the Blue

Bell that day. Sam, with ostentatious and ridiculous fuss,

made way for Doxie to sit next her lover; and then, planting himself

opposite to them, he spent his time between the mouthfuls in leering

slyly at the girl, bursting into sudden and inexplicable laughs,

driving his elbow into Nathan's ribs, and whispering very mysterious

secrets to him. Doxie was conscious of a tendency towards

hysterics, and hovered constantly between laughter and tears.

Long Ben looked wonderingly at his son every now and again, and

sighed and solemnly shook his head; whilst Andrew seemed so absorbed

in his own thoughts that he had neither eyes nor ears for anything

else. Presently the young labour leader explained that time

was now very precious to him, and that he would have to leave them.

Two more meetings would have to be held in Duxbury that day, besides

private ones, to make arrangements for other demonstrations; and, in

fact, while the matter was settled one way or the other he would

have to be working and talking night and day. He left them as

soon as the meal was finished, and Long Ben and Sam began to speak

of returning home by the three o'clock coach. Luke, however,

soon discovered that Doxie was uneasy about something; and when he

drew her aside, she whisperingly coaxed him to stay with her and try

to get her and himself into at least the first of Andrew's meetings.

Luke wavered for a moment, knowing how anxious Leah would be about

him; but at length he consented to get Sam to go down to Beckbottom

as soon as he reached home and reassure his wife; and so they

started, he and Doxie going with the others to see them off at the

coach, and then returning to inquire where Andrew's first meeting

was to be held.

|

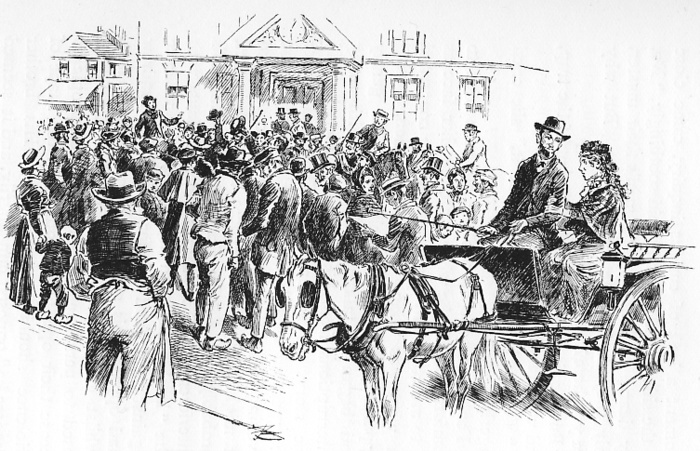

A very odd party that sat round the table.

|

When that was over, Doxie seemed as though she would have liked to

stay to the second one; but as that was to be held in a remote part

of the town and would not be concluded until late, and as Luke was

sure that if she got there it would not be possible to get her away

until all was over, he insisted that they must start off home at

once. Then she proposed that they should stay until the

evening edition of the Gazette came out; and against his own

inclinations he consented.

It was eight o'clock before they commenced their return

journey; but as soon as the town had been left behind Doxie became

suddenly very quiet, and the tongue that had rattled on so excitedly

for some hours seemed to have tired, and she sat limply by Luke's

side, looking very mournful and pensive indeed. The fact was

that throughout the day she had scarcely thought of her uncle at

all; but now, as every moment brought them nearer the village, she

began to wonder what sort of reception she would have. She

felt weary and exhausted with the trying excitements of the day, and

did not at all relish the prospect of a scene; and so presently she

resolved that she would not attempt to defend herself that night,

but endure as patiently as possible Jabe's anger and then coax him

into reconciliation next day.

Alas! when Luke put her down in the little triangle opposite

the shop, and, bidding her a cheery good-night drove off to take the

trap home, she stepped to the front door of the house and tried to

raise the latch, and then from that went hastily to the clog-shop

door and tried that, only to discover that both were closed against

her and that the clogger had gone to bed. A fretful little cry

escaped her, for she did not realise the significance of the

situation for a moment. She took hold of the "sneck" and

impatiently rattled it, then she bent down, and, putting her mouth

close to the keyhole, called to her uncle in pleading tones but

there was no response. After waiting a moment or two, she

knocked loudly on the door and then on the shutters; but still there

was no reply, and as the dreadful truth dawned at last upon her she

turned away with a wild little sob, and rushed down the hill towards

her aunt's cottage.

The two women were waiting for her, for they already knew

what the clogger thought and intended; and when Doxie saw her

mother's sad face, the pent-up emotions of the day found vent, and

she burst into a long fit of sobbing. It was morning before

she could be pacified, and almost daylight before she got to sleep;

and when late in the next forenoon she came downstairs, the first

things that met her eyes were her own boxes and all her little

possessions, even down to the cherished clarionet and the pair of

fancy clogs which had been made for her so long ago. But she

was stronger now and, though she wept at the pathetic sight before

her, she soon recovered, and sent a message to Sam Speck to come and

tell her all the news he had gathered about Andrew. She had

resolved, upon awakening that morning, to go at once to her uncle

and let him have his fling at her, and then wheedle him into a

reconciliation; but the sight of her own possessions touched her

pride, and the thought that to submit to the clogger's scoldings

might be disloyalty to Andrew restrained her, so she reluctantly

decided to let matters take their own course. And to tell the

truth, Andrew's struggles and dangers seemed to her very much more

important subjects for thought than any trials of her own, however

great; and so for the next few days she spent almost all her time

gathering what intelligence she could of his whereabouts and doings.

Little by little she realised that he was succeeding in his perilous

undertaking. First one and then another of his fellow leaders

came ever to his side, and as meeting after meeting was held and

reported she saw that the flowing tide was with her lover. One

day he came to hold a meeting at Beckside; though to her

disappointment and pain he did not attempt to get a word with her,

but hastened away to Clough End. Neither did he write during

these anxious days; and, remembering what he had said outside the

Blue Bell, she began to understand that in his view of the case much

more was involved than the settlement of the strike, and that, in

fact, if his efforts in that direction failed he would regard it as

the closing of his hope of winning her.

Gradually Doxie came to have a more perfect comprehension of

the whole struggle. Andrew had been one of the moving causes

of the strike, and had done his best by word and act to sustain the

people in their efforts. When, however, as they saw defeat in

the coming of the "knobsticks," the angry operatives, encouraged by

several of the leaders, began to resort to physical violence, his

whole soul had risen against it; and he who had been the chosen

oracle of the masses now began to be mistrusted, and, in fact,

heartily detested by them. But Andrew had held his ground,

even when suspicion looked as if it were justified by the changed

attitude of the masters. The offer made by the employers had

seemed to him a fair one; and now he was fighting an uphill battle

against prejudice and invincible suspicion to bring to an end the

very contest he had been one of the foremost instruments in

starting. Gradually also Doxie discovered that the more

reliable and moderate people on both sides of the dispute were

speaking in tones of ever increasing admiration of the manifold and

transparently honest efforts Andrew was making, and hour by hour now

the uncertain sounds of battle became more and more distinctly notes

of victory for his side.

At last, after ten days of anxious and exciting conflict,

news came that Andrew had prevailed, and the strike was over; and

whilst Doxie was clapping her hands and crying for joy a great

shouting was heard, and then the sound of a horn; and a few moments

later a dashing four-in-hand came down the "broo," crowded with

excited and joyful men, who cheered and shouted as they came, and

waved in the air flags and handkerchiefs and caps. As they

crossed the triangle Doxie, who had hastened up the hill, caught

sight of Andrew sitting on the front seat of the conveyance, looking

haggard and worn and also very embarrassed and sheepish. One

person at any rate was not enjoying the demonstration. The

four-in-hand pulled up at the mill gate, and cheers were given and

repeated for Andrew, who then made a short speech. Then they

drove away from the village en route for Clough End; and presently

Sam Speck came to Doxie with all particulars of the great victory

and of the wonderful things people were saying about Andrew.

Later still, some one brought to the village a special edition of

the Gazette, and Doxie read with swimming eyes the paragraphs

concerning the great settlement, and found them full of earnest

commendations of her once detested lover.

Next day Sam went to Duxbury, and returned with stories of

the things he had heard, which were as welcome as sweetest music to

Doxie. No persons, it appeared, were more enthusiastic in

praise of the hero of the hour than the masters themselves, and all

kinds of wonderful predictions were made as to Andrew's future; and

to crown all, when the Advertiser came out on the Saturday,

it was even more extravagant in its eulogies of the once obnoxious

"Lamp-lighter" than the paper which had introduced that now famous

writer to the public.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE EMIGRANT'S RETURN.

LATE on that same

Saturday evening Andrew arrived in the village, and almost

immediately sought Doxie out at her aunt's. The look of proud,

happy love with which she received him dispelled at once any

lingering doubt he might have as to her feelings towards him, and he

was soon deep in the story of his recent struggles and the victory

which at length had crowned his efforts. Doxie noted that

though he looked bright and happy whilst he was talking, yet when

his face was at rest it had a worn and jaded look upon it, telling

only too clearly how much he had suffered. He seemed

dispirited also; and though he was still as keen as ever in his

sympathies, he spoke somewhat bitterly of the motives and methods of

some of his fellow-secretaries, and presently told her that he had

resolved to resign his appointment and accept the situation offered

him from Manchester if it was still open.

Next day, to her surprise, he presented himself at chapel,

sitting in the Barbers' family pew between his parents, both of whom

had proud and contented looks on their faces. After a few

happy, never to be forgotten days in which she grew to understand

and admire her unselfish and high-minded lover as she had never done

before, Andrew left for Manchester, after having extracted from her

a promise of an early marriage. When he had gone to his new

employment, and things resumed their ordinary humdrum manner, Doxie

began to fret about her estrangement from her uncle. That was

the only thing which spoilt the sweet happiness she was now

enjoying, and she racked her brain again and again to try to

contrive some means of reconciliation. But so far Jabe was

uncompromisingly obdurate. He had never been to her aunt's

cottage since Doxie had returned to it, and twice when she had met

him in the road he had pursed out his lips, cocked his chin in the

air, and passed her by without speaking. There was one sign,

however, which she was fain to think was hopeful; for several days

now he had commenced to abuse her to Aunt Judy whenever that worthy

dame went to the clog-shop; and Doxie knew him well enough to be

assured that this was a certain sign of his relenting. Still,

as the days passed into weeks and no reconciliation was made, she

began to feel exceedingly uneasy and sad; and when at last she wrote

and told Andrew how it was troubling her, he replied in terms of

such respect for her uncle, and made such flattering statements

about his faith in her own powers of persuasion if only she would

exercise them, that she felt absolutely compelled to try to adopt

some means of getting back into her uncle's heart.

Meanwhile, the old clogger was suffering prolonged torture.

When his first wrath had subsided, it might have been comparatively

easy for Doxie to have effected a reconciliation; but just then she

was absorbed in the anxieties connected with Andrew, therefore the

opportunity slipped by; and when she was at leisure to think of it

again, it appeared much more difficult to accomplish, and so the

matter hung still in the balances. Jabe, however, was having a

very bad time of it with himself and his friends. Sam Speck

was indignant, and allowed no opportunity to pass of expressing his

very pronounced views; Lige and Jethro shook their heads, and sighed

whenever the subject was mentioned, moralising vaguely about people

who made rods for their own backs. It was clear to all that

the clogger was suffering, and those who came in contact with him

found him distressingly surly. One Sunday afternoon, the

super, who missed Doxie's bright presence in the house, fidgeted

about uneasily for a time, and then opened out upon Jabe, sternly

telling him that his conduct was utterly unworthy of a man of his

age and position. Jabe was obstinately silent after that, and

so the good minister, to complete his reproof, went out and had tea

with Doxie at Aunt Judy's. To make matters worse, the clogger

was compelled to hear the truth with respect to Andrew; and as the

details were laid before him, and the whole case was explained,

though he still denounced him as an "impident yung upstart," he was

feeling in his own breast that he was unjust, and that the young

man's conduct was such as ought to have elicited his unstinting

praise. But Long Ben was his worst trial. That worthy

seemed now as elated about Andrew's deeds as before he had been

distressed; and Jabe could scarcely bear himself when he saw his old

friend sitting quietly in the inglenook listening with ridiculous

complacency to the commendations which were constantly being uttered

about his brilliant son. One night, after he had delivered

himself of an unusually fierce denunciation of women, especially

young ones, the clogger received the worst blow he had as yet

sustained, when Ben suddenly rose to go home, and turning to his

friend, and surveying him with reproachful indignation said, "Mon,

Aw'm shawm't fur thi."

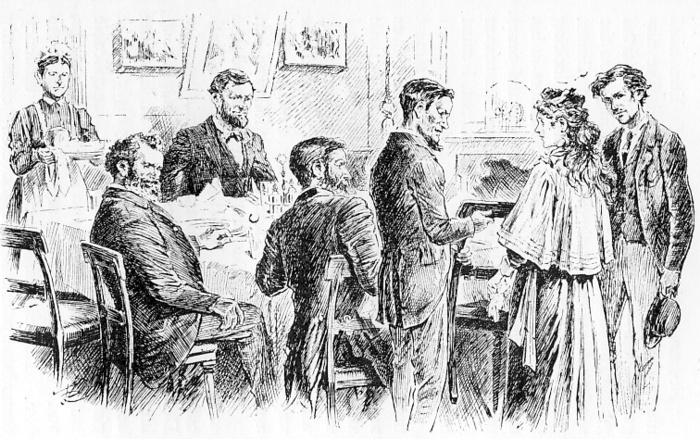

The super sternly told him that his conduct was

utterly

unworthy of a man of his age and position.

How much he missed his merry niece in those sad days nobody but Jabe

will ever know, and as day after day passed and no change came

about, he felt a sulky resentment towards Doxie because she had not

made some more decided effort to come to terms with him. The

whole thing worried him so much that he began to think it would make

him ill, and as he sat over his lonely tea one afternoon a few weeks

after Andrew had departed for Manchester he almost convinced himself

that he was ill. Then he began to pity himself as a deserted

and suffering mortal, and wondered what Doxie would do if she heard

that he had taken to his bed. He was sure what she would do,

and he heartily wished for the moment that he might be sick; and

tears came into his eyes as he pictured her bursting into the house

and coming upstairs to him the moment she was told. He was

just wiping his tears away and calling himself a "sawft owd numyed,"

when he thought he heard a low knock at the door. He held his

breath and listened, and then started violently as the knock was

repeated. He stared at the door as if he were afraid of it,

and before he could get out the "Cum in" he was preparing, the door

opened a little way, and there, framed between the edge of the door

and the post, was the bright though now wistful face he loved so

much to look upon. The emotion of the moment was too great for

him; the cup he held in his hand fell to the ground, and the next

moment, more from terror of revealing himself and his well nigh

uncontrollable feelings than from any desire to avoid her, he rose

hastily to his feet and limped off into the shop. He waited

there for several minutes anxiously expecting Doxie to follow him,

and when she did not he grew terribly alarmed, and, going back into

the parlour, felt like dropping through the floor as he discovered

that she had taken his action in the wrong light and had gone.

Jabe dropped into his chair, and felt as though he would have

liked to cry again; but the feelings that had been aroused were now

no longer to be kept down, and he knew there was nothing for it but

to take the earliest possible means of getting his niece back into

her old place. But next day, whilst he was still trying to

screw up his courage to make an attempt at reconciliation, something

occurred which upset all his plans, and made him feel that the

opportunity was probably gone for ever, and that he was to be

punished for his hard-heartedness in the worst possible form that

punishment could take; for the first thing he heard as he entered

the shop was that Thomas Dent had come back from Australia with an

immense fortune.

Yes, Doxie had not retreated from her attack upon her uncle

because she was discouraged by the way he received her, but because

her attention was suddenly and most completely diverted; for just as

she was on the point of stepping into her uncle's house she heard

herself called, and, turning timidly round, saw her aunt hastening

towards her waving apiece of paper in her hand and beckoning her to

make haste. In a moment she was reading a telegram informing

them that her father had landed in Liverpool and would be with them

that very night. Everything else was forgotten; and though she

gave more than one sad little thought to her uncle, Doxie was so

excited that she could think clearly of nothing. A trap was

hired, and she and her mother got into it, and in a few moments were

driving as fast as they could go to meet the train at Duxbury.

The women gave Thomas Dent a reception that would have satisfied the

hungriest heart, and before he had been long in the village, late

though it was, the greater part of the inhabitants had heard the

wonderful news of the emigrant's return. Jabe, as we have

already shown, did not learn the new tidings until next morning; and

before he could digest the fact his brother-in-law walked into the

shop, followed almost immediately by a little knot of curious

villagers. As our readers are already aware, Jabe bore his

relative no good will; but whatever his prejudices, they were

immediately deepened by the man's appearance and airs. He

looked browned and hard, and older than Jabe had expected; but his

manner was rough and bouncing, and his dress loud and vulgar.

He wore a velvet waistcoat and a gorgeous smoking-cap; small

earrings were in his ears, and large studs in his expansive

shirt-front; whilst heavy rings adorned his fingers, and a huge

cigar with massive mouthpiece was stuck jauntily in his mouth.

He greeted the clogger with patronising familiarity, and made a

silly joke about the fact that he was still a bachelor; then he

squatted down upon one of the stools, spread out his long legs, and

was soon regaling the open-mouthed occupants of the Ingle-nook seats

with marvellous stories of his adventures and the immense fortunes

to be picked up at the antipodes. The clogger never had harder

work to be civil to any one in his life, and Thomas must have

noticed the fact, for he soon turned his back upon the master of the

shop, and devoted his attention to more encouraging company.

He greeted the clogger with patronising familiarity.

Left thus to himself, the clogger felt his heart sink within him; he

could not get rid of a conviction that somehow the coming of Thomas

boded ill to himself, and his regrets for the occurrences of the day

before were intensified as he realised that perhaps this unexpected

return would separate him for ever from his still beloved niece.

And had he known that Doxie had already told her father about the

strained relations now existing between her uncle and herself, and

that he had expressed himself as rather glad of it than otherwise,

he would have been more miserable still. For several days

nothing was talked of in the village but Thomas Dent and the great

fortune he had got in Australia; and Thomas, revelling in most

unusual yet very acceptable popularity, used language of vague

vastness about his financial position, spoke of the mill-owner with

patronising contempt, and seemed very curious about the price of

estates in the neighbourhood, all of which, when repeated in Jabe's

ears, drew from him language which it would be an injustice to him

to print.

The poor clogger was almost beside himself. What with

Thomas displacing him in Doxie's heart, and the bold Andrew, turning

up from Manchester every other week-end, it seemed that Doxie had

forgotten him, and that he was being punished for this last cruelty

of his towards her, as he acknowledged, in his extreme depression,

he richly deserved.

The days dragged wearily by, and Jabe grew hungry for

reconciliation with an intensity that was telling upon him and

reducing his never very abundant flesh. He got a grain of

comfort one day out of a piece of information that Sam brought him,

to the effect that Andrew was said to dislike Thomas Dent as much as

he did himself; but any little consolation he thus obtained was

immediately quenched by another item of intelligence which came the

very same day, namely, that Doxie's father was not going to settle

in England after all, but that he was already arranging to return

and take his wife and daughter with him.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXIV.

THE INEVITABLE.

THE old clogger's

cup was now full. Shame, self-reproach, and fear of finally

losing his niece, struggled together within him, until he could

neither work nor think; and at last he was driven in sheer

desperation to unbosom himself to Sam Speck, and in his roundabout,

clumsy way to ask his advice and assistance. It took them some

time to get to anything practical; for Sam, inflated with the novel

dignity of mentor to his great chief, insisted upon delivering a

long and very pointed address on the folly and sinfulness of

obstinacy, and almost goaded the cowed and penitent clogger to

rebellion as he descanted on the wonderful conditions things might

have been now in if his advice had been taken. When all this

had been got through, however, Sam comforted the heart of his friend

by assuring him that if Doxie wanted to go she would go, and

if she wanted to stay she would stay, reminding him also that both

she and Andrew were of age by this time, and might be expected,

within reasonable limits, to wish to please themselves.

Now Sam said these and many other unnecessary things because

he really saw no way out of the difficulty himself, but hoped that

discussion might suggest something; and sure enough, just at this

point, he had one of his rare inspirations. But as he did not

wish the clogger to think he had only just thought of it, he beat

about the bush a little longer, and then by little particles let out

his great plan. What it was will be seen presently, but after

the clogger had offered his counsellor a most unusual compliment,

and they had arranged all the details of their great conspiracy,

they parted, and the next afternoon Sam, in pursuance of the scheme

already agreed upon, was waiting in the triangle opposite the

cloggery when the extra Saturday afternoon coach from Duxbury

arrived. As he anticipated, Andrew Barber alighted from the

conveyance, and was just turning round to go down the "broo," when

Sam touched him on the shoulder and informed him that the clogger

wanted to speak to him before he went any farther. Andrew,

somewhat astonished and perplexed, and withal a little impatient,

followed his conductor towards the house door, which Sam, as soon as

he had admitted Andrew, immediately closed from the outside, thus

leaving the young man alone with his old enemy.

Jabe was sitting before the fire with his short leg on the

hob, and seemed not for a moment to have noticed the entrance of his

visitor. As Andrew approached him, however, he turned round

with a transparently affected look of surprise, and then, pointed,

without speaking, to a chair.

"You wish to see me, I hear, Mr. Longworth," said Andrew,

dropping into the offered seat.

"You wish to see me, I hear, Mr. Longworth."

"Mester Lungworth! Mester Lungworth! Ha lung is it sin

Aw gan o'er being cawed Jabe?" And the clogger looked at his

visitor with apparent sternness.

"Oh, well, thank you! 'Mr. Jabe,' then. I think you

have something to say to me?"

"Ay, Aw've hed summat ta say ta yo' fur a lung toime, bud yo'

ne'er gan me t'chonce." And Jabe looked dreely at the curling

smoke as it rose from the bowl of his pipe.

"Indeed, sir! I shall be glad to hear what it is."

Jabe looked as if the conversation was not taking exactly the

course he wished, and he affected to appear very dubious about

Andrew's last remark. "You'll happen no be sa fain ta yer it

when Aw tell yo' wot it is."

"Indeed! sorry to hear that; but what is it, Mr. L—Jabe?"

Jabe looked as if he would have liked to explode upon Andrew

for still using such stiff English; but it was time they came to

business. He took two or three pulls at his pipe, and then,

without turning his head, said:

"Aw allis thowt az yo' wur a chap az hed plenty o' pluck."

"Pluck! Nothing to boast of, I'm afraid; but what do――"

But the clogger, entirely disregarding Andrew's remarks, here

interrupted: "An' they tell me az when yo' taken owd of a thing, yo'

niver let gooa."

"They are very complimentary, whoever they are; but what does

all this matter?"

Jabe smoked on as if Andrew had never spoken, and presently

resumed: "If a wench is woth hevin' at aw, boo's woth feightin'

fur."

"Really, Mr. Jabe, I cannot understand."

But here the clogger could contain himself no longer, and so,

whisking suddenly round in his chair, he rose to his feet, and

shaking his fist at Andrew, he demanded: "Wot Aw want ta know is

this, arr yo' goin' t' let yond' wench goo ta Australy or arr yo'

not?"

Now Andrew had not as yet heard anything of this second

projected emigration, and so, opening his eyes very widely, he

demanded: "Mr Jabez, whatever are you talking about?"

"Talking abaat? Aw'm talkin' abaat yo'. Yo're

goin' meytherin' abaat wi' them mollycoddlin' bewks o' yores woll

yond' wench is slippin' through yur finger; that's what Aw'm talkin'

abaat. Dun yo' know az yond' wastril's takkin' hur back ta

Australy?"

The puckers suddenly faded out of Andrew's face. He

knew enough of Doxie to be sure of his ground as far as she was

concerned; but he was reminding himself of the estrangement between

the clogger and his sweetheart, and so he looked steadily at Jabe

and inquired, "Well, you won't mind that at any rate, will

you? Doxie's nothing to you, you know, now."

This was hitting the poor clogger very hard indeed, and he

felt it all the more because it was so entirely unexpected; he

winced visibly, dropped his head, and then with a sullen growl he

put out his arm and cried:

"Ne'er moind me. Wot aar yo' gooin' t' dew?

That's th' pint."

And Andrew, who was rather wickedly enjoying Jabe's evident

distress, answered with assumed carelessness, "Oh, that's Doxie's

affair; she'll take care of herself, don't fear."

Jabe's condition was pitiable to behold; he was making no

headway, and the iron was striking deeper every moment. He

paused and drew a long breath, and at last, throwing off all

pretence, he burst out in tones that were quite pathetic, and that

touched Andrew in spite of himself: "Naa lewk here, yang felly, dew

yo' want yond' wench ta goa ta Australy, or dew yo' not?"

"Oh, I don't, of course."

"Well, then,"―and here Jabe became wonderfully confidential

and almost coaxing,—"yo' mun wed her and keep her here, yo' mun

helope wi' her or run off wi' her, or dew owt az yo'ne a moind wi'

her, nobbut keep her here, an' Aw'll ton by yo' an' find th' brass,"

By this time, however, Andrew's patience was exhausted, and

so to get away he thanked the clogger very warmly and promised to do

his best, and a few minutes later he was sitting over his tea at

Aunt Judy's. Thomas Dent happened to be out—he generally

managed to be so when Andrew was about, for there was no love lost

between the two; though Andrew for Doxie's sake contrived to conceal

his feelings as much as possible. They had finished the meal,

and Doxie was just preparing to go for their usual walk to

Beckbottom, when Andrew dropped a word or two about his interview

with her uncle. Doxie was all eagerness in a moment, and

before he had finished his story she abruptly left him, and a moment

afterwards was rushing up the "broo" as fast as she could go.

Before the clogger could realise what had happened she had burst

into the house and had taken him by the neck and was kissing him as

though she never intended to cease. Andrew not only missed his

expected walk that night, but Thomas Dent found that neither

coaxings nor threats could get his daughter away from her old home;

and she established herself, in spite of everything and everybody,

once more as her uncle's housekeeper, whilst Andrew, with affected

jealousy, yet with real joy in his heart, had to do his courting

henceforth in the clog-shop parlour.

However, they were not yet quite out of the wood.

Thomas Dent was inclined to be awkward. Neither Jabe nor

Andrew had treated him, he thought, with proper respect, and he said

to his wife, what he was evidently afraid to say to Doxie herself,

that he had a good mind to spoil her spooning and teach her that he

was not to be trifled with. Somehow he had been disappointed

in this great return of his, and said more than once to Doxie's

mother that he was sorry he had come home. But when the news

that he was to return almost immediately got noised abroad, people

began openly to sneer at his pretensions to wealth, and Sam amused

himself by telling him whenever he came to the clog-shop fire of

this and that "good thing" in the way of investments, always quoting

large figures on the assumption that nothing smaller would be worth

the Australian hero's notice. Jabe greatly enjoyed his

friend's sallies, and chuckled inwardly as he watched Thomas's

evident embarrassment. But one day Sam hazarded the prediction

that Thomas would not return to Australia after all—he wouldn't be

able to find the money; at which the clogger took alarm, and

declared that he would take care he did go even if he had to find

the passage money himself. Thomas seemed to wither under his

growing unpopularity, and became impatient to get away; but in order

to recover himself somewhat in popular esteem before he went, he

affected to make a great virtue of consenting that Doxie should

remain, and he insisted that the marriage should take place before

they—he and his wife—departed. Then seeing that by this means

he was recovering himself in popular favour, he began to hasten on

the preparations, and instructed Doxie to spare no expense, but to

give "these Becksiders" something to remember. Doxie and her

sweetheart took it all very quietly; they had soon decided that her

father need not be considered in the arrangements, and his sudden

disposition to help things really made little difference.

At last the happy day was fixed, and Beckside began to

prepare itself for another sensation. By Jabe's express orders

the chapel was cleaned from floor to ceiling and the paint touched

up wherever it was discovered to need it. The super was

retained for the occasion a full month before the date fixed, and

Jabe and Sam solemnly discussed the question as to whether it was

not the correct thing to send the officiating minister some sort of

fitting apparel such as a hatband or gloves at least. The band

of course was to officiate at the ceremony; but when Doxie insisted

that the proper thing would be for the doctor's wife to play a

wedding march on the organ they set to work to prepare to lead up

the wedding procession. Doxie explained that that was not the

correct thing, and so they hit upon the happy idea of meeting Andrew

at his father's house and marching him up to the chapel; and it was

only when she discovered that her uncle was getting warm about the

matter that she consented. A day or two later, however, she

hit upon an expedient, and asked her uncle why he was not going to

be of the wedding party itself. This was a new view of the

case; and so the clogger gave way, as far as he was concerned, and

finally, it was settled that the musicians were to perform outside

the chapel whilst the organ was doing its work inside.

Never was there so much utterly reckless expenditure on mere

fine clothing as on the days preceding the great event. Jabe

of course must have an entirely new suit of black and some wonderful

new fronts. Sam Speck borrowed a dress suit from a cousin of

his, who had once attended the mayor of Duxbury's reception; and it

was only after he had given one or two strictly private exhibitions

of himself in these marvellous garments that Doxie discovered what

was on foot and induced him to abandon the clothes in favour of a

grand waistcoat which Luke Yates had had for his wedding.

The happy morning came at last, and proved as fine a one as

the most superstitious bride could wish. There was an

immemorial tradition in Beckside that the bride should not be seen

on her wedding day until she appeared ready to be led to the altar;

but Doxie was up almost before daylight, and waiting in her own

gayest fashion upon those who were supposed to have come to wait

upon her. Her mother was dressed before breakfast, and was so

afraid of spoiling her new finery that no possible persuasion could

induce her to partake of food.

Leah Yates came early to assist in dressing the bride, and

had just got into her happy task when Aunt Judy came back from the

clog-shop almost crying, and denouncing her brother as the most

awkward and unmanageable man ever made. Doxie saw at once that

something was wrong, and gradually drew out of her aunt the

intelligence that she had been engaged for the last hour in trying

to "fix" Jabe's new front, and that at last her uncle had got into

such a pet that he had actually thrown the offending garment on the

back of the fire. Bride or no bride, Doxie was off in a moment

up to the cloggery, where she found Jabe, sitting half-dressed in a

chair and looking the very picture of wretchedness. In a few

minutes she had him smiling; and though he did not understand what

she was doing to the second front which she unearthed from

somewhere, he looked at himself in something like terror when she

led him to the glass and showed him an immaculate piece of linen

with two dazzling real gold studs in it, her own secret gift to him.

Then she scurried off back to her own toilet, whilst the clogger

went over and inspected Sam, who had already been dressed some time.

The unmanageable man ever made.

Presently there was a cry in the village that the coaches were

coming—real gray horses, with white tassels on their ears. Oh,

what a commotion they did make! Then the band, consisting of

all those who were not required for more important business, came

and planted itself before the clog-shop, and solemnly played the

"Old Hundredth." After this the coaches came dashing up the

"broo" with the bridegroom inside, and the chapel became the centre

of attraction. It was crowded long before the time appointed,

and when at last the bride's coach left Aunt Judy's little cottage,

the bystanders sent up a great cheer, and the band hastily picked up

their music-holders, and raced along towards the chapel. Doxie

looked undeniably pretty as she came to the communion-rail on the

arm of her father, and it seemed only right that Jabe should bring

the bride's mother. Andrew was almost forgotten in the

interest shown in the others, and it was only when his sonorous

voice repeated the sentence that people realised his presence.

"Who giveth this woman to be married to this man?" said the

minister, and he glanced quietly up at Doxie's father. That

good man, however, had not expected to be thus publicly challenged,

and before he could recover himself to do his part a hard elbow had

been thrust into his side, a rugged face projected itself alongside

his, and the now husky voice of the clogger rang through the chapel

as he cried, "Me."

It was over in a minute or two, and then there was a pause

whilst the register was being signed in the vestry. "They're

coming," cried some one at last; and as the organ began

Mendelssohn's grand march the band outside struck up a hymn tune,

and the party left the chapel in the full blare of complete, if

somewhat conflicting, musical honours.

Two years later Jabe received a message to say that Doxie and

her husband were coming to Beckside to bring the baby to be

christened, and after many debatings Sam Speck was sent off to

Duxbury to buy a new font, with strict injunctions that it was to be

a full size larger than the Clough End one, and that he must be sure

to bring it back with him for fear of accidents. When the

young people arrived on the following Saturday the clogger seemed as

if he did not want to see the baby; but Doxie knew how it was with

him, and very soon left it in his charge. A few minutes later

it was squalling in the clog-shop, where Jabe had taken it to

exhibit.

"Wot's its name?" he demanded gruffly, as Doxie came in and hastened

to rescue her offspring from its clumsy nurse.

"Ah, that is a secret! What do you think would be a

nice name, uncle?"

Jabe "knew nowt abaat sick things" but he "reaconed it would

be saddled wi' sum newfangled nomminney or uther." The proud

mother assured him that it was going to have the very nicest name in

all the world; and next morning Jabe gave a loud grunt, which might

be interpreted to mean wonder or satisfaction or almost anything

else in the world, as standing up in his place in the chapel, he

heard the little stranger solemnly endowed with the baptismal name

of JABEZ LONGWORTH.

――――♦――――

PRINTED BY

HAZELL, WATSON, AND VINEY, LTD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY. |

|