|

DOXIE DENT.

CHAPTER I.

THE CLOGGER AT BAY.

JABEZ

LONGWORTH, clogger,

woman-hater, Methodist steward, and general village oracle, sat one

morning in the parlour adjoining the clog-shop meditatively eating

his breakfast. His reflections were evidently of a distracting

character, and interfered with the progress of the meal. As he took

up the last spoonful of porridge and transferred it to his mouth his

face puckered into frowns, and, arresting the spoon as it approached

his lips and setting his teeth grimly, he growled out, "The brazzened bosom!" Then he slowly swallowed the porridge, thinking

rapidly the while, and at length, throwing the empty spoon down upon

his plate with a sort of punctuating bang, he went on, "It sarves

him reet! He's wur nor hur! he is, fur sure."

A moment later he turned his chair towards the fire and put out his

hand towards the oven-top, and began to feel absently for his pipe. As he did so his eye fell upon the steaming coffee-pot, and,

suddenly remembering that he had had only one of the courses of his

double-barrelled breakfast, he picked up the vessel and poured

himself out a full cup. As he turned to replace the coffee-pot on

the hob, he paused a moment, took a long, comprehensive look round

the room, and heaving a little sigh burst out, "Thank goodness

there's wun haase i' Beckside az isna plagued wi' th' petticoat

pestilence! Neaw, nur ne'er will be woll Aw'm in it!" And then he

resumed his seat, flinging his expressive short leg over the other

with an emphatic and conclusive jerk. Just as he was taking a

sampling sip at his cup the door opened, and in stepped his big,

much enduring sister, Aunt Judy.

"Aw've browt thi sum scratchings fur thi breakfast," she said, with

a heavy sigh, as she approached the table.

The clogger helped himself to the scratchings with an inarticulate

grunt.

"Hay dear!" began Judy, who evidently had something on her mind, and

was in a fretful and despondent humour; but just then she caught

sight of the long-settle, which was tumbled up as though some one

had slept on it. "Wot's ta dew wi' th' lung-settle? Tha's bin

sleepin' onit, an' thee wi' th' best feather bed i' Beckside

upst'irs: a body 'ud think tha'd bin drunk an' aat aw neet. Aw'm

shawmed fur thi, Jabez."

Jabe dipped his scratchings in the salt and grunted, "It's no me."

"Then whoar is it?" demanded Judy sternly.

"It's Sam; yond'

bully-ragging huzzy locked him aat."

"An' sarve him reet! that shop o' thine's woss nur ony ale-haase ov

a neet! Wot's he want going whoam at that time fur?"

Jabe crammed the last of the scratchings into his mouth, and then

turned away from the table. As he did so he put out one hand to feel

for his pipe, and stretching out the other he clenched his fist and

shook it at his sister and cried fiercely, "Si thi, Judy, if Aw'd

owe ta dew wi' yond' woman Aw'd welt her rig fur her! that's woe

Aw'd dew." And he crammed the tobacco savagely down into the bowl of

his pipe and proceeded to light it.

"Women!" he cried, dropping back into his chair and pouring out a

volume of smoke, "women! wherever there's women there's bother. Th'

weaker sect!" he added, curling his lip with intensest sarcasm. "Theyn played Owd Harry wi' th' strunger sect, that's aw az Aw know;

bud theyn ne'er bamboozle me, thank goodness, an' they ne'er will

dew noather. Aw'll show 'em!"

Now it so happened that the conversation had taken the most

unfortunate of turns for poor Aunt Judy; she had come on a very

delicate and difficult mission, and her little present of

scratchings was intended to pave the way for her; and, lo! the

conversation had taken a turn which made her errand more difficult

than it might have been, which was unnecessary. She wished she had

never seen the crumpled long-settle, and turned away from it with a

petulant gesture. Then she took a long, wandering glance round the

room, and, putting her feet upon the fender, looked dreamily into

the fire.

"Hay dear!" she murmured presently, with a most alarming sigh, "this is a weary wold." And then, as she realised her feelings were

getting the better of her, she hurried into the pantry to recover

herself. Presently she came back again, and, standing leaning over

the fireplace, resumed her absorbed gaze into the fire.

Now the clogger had been dimly conscious for some minutes that there

was something not quite satisfactory about his sister, and so as she

stood before him looking dejected and miserable he jerked out

shortly, "Wot's up wi' thi?"

Judy commenced to rock herself over the

fireplace, and at last answered in a breaking voice, "Nowt."

All the same the poor creature's rockings became more rapid and

pronounced, and presently a great tear dropped upon the hot

fire-irons and sent out a loud hiss. And of all things Jabe hated

tears, especially women's tears. He pulled himself together in his

chair, glared angrily at the moving form of his portly sister, and

then said with stern deliberateness, "Judy, prating women's bad, an' schaming women's wur, bud the Lord deliver me fro yowling women." And then, with a jesture of disgust, he rose to his feet, knocked

the ashes out of his pipe, and walked off towards the shop.

But this did not suit Judy's purpose at all; the matter in her mind

was too serious to admit of delay, and so she cried in fear and

alarm: "Jabe, dunna, dunna goo. Aw've summat to tell thi."

Jabe, standing with the clog-shop door half open in his hand,

demanded in his surliest tones, "Well, wot is it?"

And Judy, dropping into a tone of dark mystery, cried, "Aw conna

tell thi theer; shut th' dur an' cum here."

Jabe let the door slip from his hand, and taking a step nearer, but

still standing at a non-committal distance, he jerked out, "Well?"

But now Judy's feelings suddenly overcame her, and she dropped her

head on the arm that was leaning on the fireplace and began to sob. Jabe glared at his sister in angry disgust, and after a muttered

imprecation on all women he demanded in louder tones, "Wot is it,

woman? aat wi' it."

Judy only sobbed the louder, and presently groaned out, "This is a

weary wold."

"Confaand th' wold! Aat wi' it, woman."

After a moment or two of uneasy silence, the weeping woman turned

her pathetic and tear-stained face to the clogger and stammered out,

"Jabe, aar Tummas 'as brokken"; and then she fell back into a

chair and began to cry afresh.

Jabe's face suddenly straightened into excessive gravity; he lifted

his hand nervously to feel for his coat collar, but as he had no

such garment on at the moment, it dropped helplessly to his side

again, and his loose, short leg began to move uneasily.

"An' sarve him reet!" he cried presently, in a voice too full of

wrath and scorn to be loud. "Didn't Aw allis tell thi it 'ud cum to

that?"

Judy heaved a most appealing sigh, and groping in her pocket

produced a letter which she held out to the clogger, crying as she

did so in pleading tones, "Bud tha'll help 'em, Jabe lad, wiltna?"

"Help 'em!" Snatching the letter from his sister, the clogger threw it

as far as he could across the room, and said bitterly, "Aw'll see 'em

i' th' bastile (workhouse) fost!"

"Bud there's aar Annie an' th' chilt; tha'll tak' pity upa them,

sureli."

"Help her! Ay! Aw'll help her, Aw will that! Hoo's made her bed, an'

hoo mun lie on it."

"Hoo nobbut wants uz to tak' th' chilt tin they getten streight

ageean," persisted Judy.

"Nobbut th' chilt!" mocked the slogger indignantly. "Oh, neaw!

nobbut th' chilt, th' thin end o' th' wedge! Fost chilt an' then th'

muther, an' then th' baancing blash-boggert ov a husband! Not me,

Judy! not me!" He shook his head in knowing but resolute refusal.

"Ther wur noabry loike aar Annie wi' thee, Jabe, wunce."

"Naa then! noan o' that! Aw whop Aw'st neer see ony on 'em ageean." And he limped uneasily across the floor to the window, for Judy's

last remark had evidently probed an old wound.

"Nor even up aboon," murmured Judy; and she winced in anticipation

of the explosion that she expected would follow.

Jabe stood staring hard through the window to get his face under

control, and at last he said:

"Judy! Aw tewk cur o' that wench loike a feyther; Aw'd 'a' made a

lady on her if hoo'd 'a' let me. Aw warnt her ageean yond' wastril

toime an' toime ageean. An' hoo desaved me an' cawd me everything hoo could lay her tongue tew, and then hoo left me an' went off wi'

him. Hoo's made her bed, Aw tell thi, an' hoo'st lie on it fur me."

Then Judy rose to her feet and stepped towards the clog-shop door,

for all the familiars used that mode of entrance to the parlour, the

front door being only available on Sundays. When she reached the

door and was just passing out, she turned round and with solemn

dignity said:

"Jabez! aar Annie sarved me ten toimes wur nur hoo sarved thee: an' Awm nor a classleader nor a steward nor a superintender; Aw'm nobbut

a poor, sinful woman. Bud Aw'st need forgivin' sum day, an' Aw've

furgeen aar Annie upo' my knees this varry morning. Thaa con pleease

thisel'; bur Aw'st send fur yond' chilt this varry day."

And with a sort of I've-cleared-my-conscience cough Judy drew the

door to and disappeared.

As the reader will have already guessed, the

conversation just reported had reference to an early episode in the

family history of the Longworths. About twenty years before the time of which we

write Jabe and Judy had been proud in the possession of a bright and

clever younger sister. At Jabe's expense she had received education

much beyond what was possible to those of their class. She had

worked all those wonderful "samplers" which, framed in heavy

rosewood, were still the chief ornaments of Judy's little cottage,

and knew more wonderful and complicated stitches than any woman for

miles around. She was the chief treble singer in the choir, and the

only person who could be trusted to bake the tea-party "bun loaf." Her brother was inordinately proud of her, and came as near to

compromising his already pronounced opinions on the woman question

in her favour as he ever did in his life. It was even rumoured in Beckside at one time that the minister, who was young for a "super," and a childless widower, was "makkin' up to her," and it

was whilst the expectation of the news of this engagement was

keenest in everybody's mind that there came to the village that

frivolous and "impident cock-sparrow," the travelling draper's

assistant from Duxbury.

This young man was from Cumberland, and had been engaged to assist "owd

Dyson," who for many years had come twice a week to Beckside and

the surrounding villages retailing drapery, but who now was unequal

to the journeys himself. Jabe took a dislike to the young fellow

from the first, and missed no opportunity of taking him down. Aunt

Judy went to the length of withdrawing her custom from him, and even

did some little to influence Mrs. Ben Barber in the same direction. When therefore, it was suddenly discovered that young Dent was

making love to Annie, and that she was encouraging him, Jabe's wrath

knew no bounds. He stormed, he walked up and down the parlour

calling the young draper all the opprobrious names he could think

of, and threatening that if he saw him speaking to Annie again he

would "bansil his hide fur him." Then in his disgust he fell to

mimicking a peculiar manner the young man had of carrying his left

shoulder. He satirised his unusual height and extreme thinness, and

went through a savagely grotesque imitation of the way he dealt with

his customers, until poor Annie was provoked into taking the young

fellow's part and defying her relatives.

Then it was discovered that young Dent was not a member of Society,

was not even a Methodist, and, in truth, made light of religion

altogether. This last fact cooled Jabe somewhat, and he felt so

absolutely sure his sister would not think seriously of marrying an

utterly worldly man and a stranger, that he was inclined to think

there was no need to be alarmed. One morning, however, Aunt Judy

came to the clog-shop with a fearful and alarmed look on her face. Annie had just told her that she was going to be married almost

immediately. Once more Jabe lost control of himself; he limped off

down to Judy's house, and burst in upon his frightened sister with

most terrible denunciations. After recovering herself a little, she

replied in kind, and in the end the clogger had pronounced his final

fiat:

"Goa! thaa impident madam! Goa thi ways! Bud moind thi, th' day az

tha drops th' Lung'orth name tha drops th' Lung'orth blood. Moind

that naa."

And Annie had gone; not indeed immediately, for she spent several

days more in her old home with Judy. When at last she departed, and

word came that she was married, Judy discovered that Annie had spent

most of her time since Jabe's final pronouncement in rummaging the

drawers and boxes of the house and appropriating everything movable

that she could lay her hands on. Nay, more: in one of the upstairs

drawers the two of them had put their little savings together in an

old purse; but Judy found that the purse was gone.

Since that sad parting Jabe and his sister had scarcely heard of

Annie, and when they did, it was some inflated piece of intelligence

setting forth how wonderfully they were getting on, and in what fine

style they were living. The Dents had, however, led a wandering

life, and Judy, who was generally the first to get the news, had

heard of their living in this and then in that provincial town; but,

finally, they had gone to London, and knowing how much this fact

would impress the minds of the Becksiders, Annie had written a

letter to Judy describing the grand style in which they were living

and carefully detailing all the little attractions of their only

child, who was about six years of age. Since that time next to

nothing had been heard of them, and Judy had long ago concluded that

they had got too big to think of their poor relatives.

In justice to both Judy and her irascible brother it is only fair to

say that in their hearts they had been more than willing for years

to come to a reconciliation; but the others gave no sign of

relenting, and what messages had been received were so flippant in

tone that the two had concluded that the Londoners were still

obdurate.

All at once this had come. Annie had sent a most touching and

pathetic letter, telling of their misfortune, and begging in words

of penitent humility that the disgrace might be kept from the child,

and that for a time her auntie would take her in. Twice during that

day Judy returned to the clog-shop to plead with her brother, but he

remained cruelly obdurate; and so at last, heedless of what he might

either say or do, she had got Mrs. Johnty Harrop to write a letter

bidding her relatives send the child at once.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

THE COMING OF DOXIE.

AUNT

JUDY held an important

position in Beckside; she was the self-appointed and unpaid village

nurse. In fact, a salaried nurse was unheard of amongst the

villagers; when any one was seriously ill and needed attention, such

service was usually rendered by the relatives and neighbours, with

the assistance and under the superintendence of Jabe's big sister.

She lived in the old cottage, where all the present generation of

that family had been born, and which had been left to her by her

father. She had a small annuity bequeathed to her by her

husband, and this, together with a subsidy paid to her by the

clogger in return for her services as non-resident housekeeper,

enabled her to live in modest comfort. She had her brother's

love of authority, and this, with certain skill in the making of

herb drink and other simple medicines, and her own big, tender

heart, had gradually led her to adopt nursing as her sphere in life.

But her "professional" duties, of course, greatly interfered with

her domestic arrangements, and she was so uncertain in her habits,

and so often away from home, that she could never entertain visitors

for any length of time. When, therefore, friends did come to

stay with her, it generally happened that the duty of entertaining

them fell quite as much upon the clogger as upon Judy herself, and

they usually ended by settling down at the clog-shop as in every

sense the more attractive place. But though all the world

might come and welcome to the clog-shop fire, Jabe had decided views

as to who should occupy the parlour and sit down to table with him;

and as Judy was never certain at what hour she might be summoned to

attend to some one, it was always necessary to get the clogger's

consent before she could invite anybody to stay with her for a

lengthened period.

This, therefore, whilst it explains the object of Judy's

interview with her brother, will enable the reader to enter into

Jabe's feelings as he sat at his bench that morning. The news

about Annie was sufficient of itself to send him off into a long fit

of abstraction, for he had dearly loved her, and did so still, in

spite of the scorn with which he always received any reference to

her. But this additional item of the coming of Annie's

daughter was a serious complication of the situation and worried him

exceedingly. Judy, as we have already intimated, visited him

twice that day, but found him increasingly raspy and abusive, and to

all his other friends he was taciturn and uncommunicative.

As Judy went home from her second attack upon her obdurate

brother, she met Sam Speck coming up the "broo," and immediately

communicated to him the news. Sam received the intelligence

with interest, and with something more than resignation. He

had now a partner in distress. The "wench" whom Judy was

inviting was as near as she could reckon about fifteen years of age,

and would prove in Sam's way of reckoning a sufficient "handful" for

the clogger. For years Jabe had chaffed and "bullyragged" him

about his cowardly subjection to feminine tyranny, and had chuckled

triumphantly about the freedom of the clog-shop from such

exasperating and humiliating torments. Anything and everything

that wore a petticoat was an irritation to Jabe, and provoked his

sarcasm or his abuse. What would he do now? And a wench

of that age was such an uncertain quantity; you never knew whether

to treat her as a woman or as a child. Jabe would be in a "hotterin

mafflement," that was certain. Well, at any rate he would have

more sympathy with him now, and that was something. Meditating

thus, Sam lounged into the clog-shop.

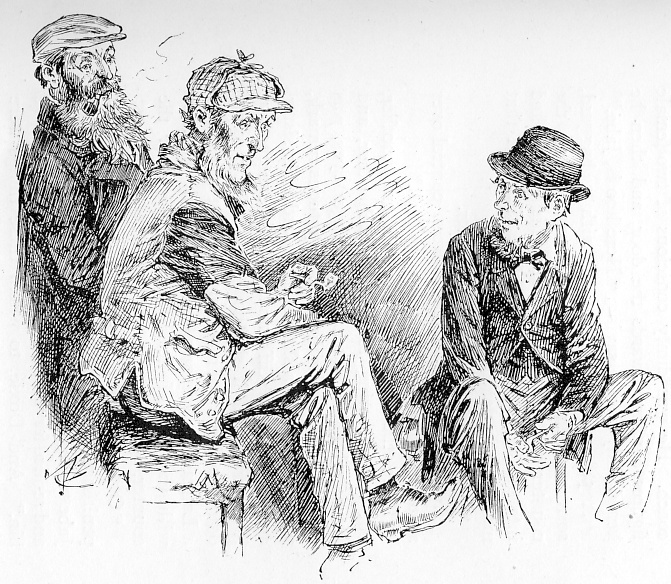

|

Sam lounged into the clog shop.

|

He cast a quick glance at the clogger as he passed to the fireplace,

and noted with satisfaction that his aspect was distinctly thundery.

He bent over the fire for a light, and his face had a smirk of

satisfaction upon it.

"Yore Judy's in a foine flutterment yond'."

And Jabe lifted his head and glanced out of the window with a

significant sniff, but never spoke.

"Yore Annie's wench 'ull be a woman bi this welly."

But the slogger went doggedly on with his work.

Sam shifted his position, stretched his legs out on the old

clog-bench near him, transferred his pipe to the other hand, and

then resumed, "Wenches o' that age is awkerd to dew wi'."

Jabe took another long look through the window, but did not

reply; and so Sam changed his tune and said, with a demonstrative

sigh, "Hay dear! ther's nowt bud bother wheer wimin is."

Jabe lifted his head, and, taking another look through the

window, answered with a slight sneer, "Ay, when them az hez 'em's

wimin tew."

"Ivverybody con deeal wi' th' divil bud them az hez him,"

responded Sam; "bud we shouldna whistle afoor we're aat o' th'

wood."

"Wot wood? Wot's th' lumpyed talkie' abaat?" Jabe

turned half round, and looked at his friend with a glance in which

affected surprise and lofty disdain were curiously blended.

But Sam had just got another idea. Jabe was evidently

vulnerable on this point; he had often bullied him on this question

before all their friends, and had held him up again and again to

scorn. Now it was his turn, and he would make the most of it.

Yes, he would have Jabe "upo' th' stick" that very night, and would

reserve and prepare himself for that occasion. And so, when

evening came, and the regular frequenters of the clog-shop had got

to their places and were filling the shop with smoke, Sam, who had

carefully chosen his place, and was almost invisible far into the

Ingle-nook, waited for a pause in the conversation, and at length

said, looking across at Long Ben the carpenter, "This is a wold o'

changes, lad." Then he winked a wink that puckered the whole

of one side of his face, whilst with the other eye he glanced

significantly at Jabe.

Ben, who had not yet found his cue, sighed sympathetically

with a half-expectant "Ay."

"An' cappin' changes tew," persisted Sam and he nodded his

head sagaciously. "They arr that—mooast on 'em!"

Sam drew a few long, reflective pulls from his pipe, and

then, leaning forward and putting as much serious sympathy into his

voice as he could command at the moment, he said, "There's a change

coming to th' clug-shop."

Jabe, who was standing at the counter and cutting out

clog-tops, here began to give some directions to his apprentice in a

loud, hurried tone.

"I' th' clug-shop! Wot soort o' changes?" asked Ben, as

soon as the clogger paused.

"A wench!"

"A sarvent lass, dust mean?"

"A sarvent lass!" cried Sam, in high disdain. "A missis,

mooar loike; a high stepper—a Lundun wench wi' frills an' flaances

an' stroiped stockin's an'foine cockney talk!"

An illuminating grin passed over Ben's countenance, and his

eyes twinkled with fun. He had already heard the news from

Judy, and now fully comprehended what Sam was after. He sat

musing for a moment, then stole a sly glance at the silent clogger;

at last, heaving a sigh of prodigious length, as an expression of

profoundest sympathy with his unfortunate friend, he said:

"Them Lundun wenches is ter'ble forrat."

"Ay," sighed Sam, with exaggerated impressiveness; "theyn

tongues loike razzors."

"An' they don thersel's up loike pace-eggers."

"An' they conna eight wot we eightn." This from Lige,

the ex-road-mender.

|

"Wot sort o' changes?" asked Ben.

|

For ten minutes more the confederates went on with their comments,

but the clogger was not to be drawn. He kept his lips tightly

closed, and gleams of wrath shot every now and again from under his

shaggy eyebrows; but never a word would he speak, and Sam went home

very disappointed with the result of his attack. Nevertheless

Jabe was a long time in getting to sleep that night, and next

morning as Judy was leaving him after discharging her duties he

called her back.

"Si thi," he cried, fiercely shaking his fist at her, "if

thaa brings ony missnancified powsement of a wench here, Aw'll—Aw'll

chuck her i' th' beck, an' thee efther her; soa moind that naa."

A week later it was known in Beckside that Judy's sister's

daughter was coming, and would, in fact, arrive next day; and though

the story of the failure of Annie's husband was a sufficiently

interesting topic of conversation, it was almost forgotten in the

curiosity shown to see a real London "wench."

Jabe, however, manifested complete indifference on the

subject, and even went so far as to pretend not to know when the

visitor was coming. All the same, as the time of arrival drew

near he grew most unusually fidgety.

Sam and Lige strolled in during the afternoon with the object

of having a good view of the coming wonder, from the safe

vantage-point of the clog-shop window and also, it must be admitted,

of enjoying the meeting between Judy's guest and the clogger.

Jabe began to be very restless; twice he sat down to his work near

the window, and each time relinquished it in a pet and resumed his

place by the fire. Then he began to tidy up the little

counter, humming fitfully an old tune; but upon Sam making a remark

which showed that he thought his friend was making ready for the

new-comer, he suddenly abandoned his task and went and sat down

again in the chimney nook. Next he tried to start conversation

on two or three utterly uninteresting topics, and when he could got

no satisfactory response, and noticed that Sam grinned every now and

again in a most suspicious but wholly unexplainable way, he called

that worthy a "gibbering numyed" and resumed his work once more.

Just then the coach was heard coming clattering down the "broo," and

a moment later it had stopped in the triangle opposite the shop.

Sam and Lige immediately hastened to the outside of the counter, and

with heads close together stood watching for the first glimpse of

the new arrival.

"Si thi, Jabe! theer hoo is! Hay, by gum! si thi, mon,

si thi! Hoo's a switcher."

But Jabe would not even lift his head.

As the passengers alighted, they turned and looked towards

the cloggery, evidently expecting its owner to appear; then Aunt

Judy climbed slowly down the coach steps, and turned in the same

direction, whilst a tall, fair girl who followed her moved her head

half round and glanced shyly about. The coach drove away, and

Judy, after another pensive look towards her brother's residence,

taking hold of one end of a big box, and motioning Nathan the smith,

who was a passenger, to take the other, moved off towards her own

home.

For the next half-hour or so Sam and Lige held forth on the

attractions of the girl who had just arrived, making as often as

they dare oblique references as to what they would have done if they

had had so attractive a relative. But the clogger neither

moved nor spoke, and only gave indication of feeling by smiting away

most unmercifully at an obdurate piece of leather. It was

Sam's tea-time, and as he was in disgrace at home, he had need to be

punctual, and so began to make off. As he reached the door he

turned aside and took another peep through the window, and very

hastily drew back.

"By gum, Jabe, they here! they here!" And he hopped

hurriedly back to the fireplace, for, tea or no tea, he must see

this out.

Jabe's face twitched rapidly, and he began once more to

belabour the leather. The door opened, and in walked Judy, a

little out of breath and visibly nervous, followed by the girl.

"This is hur, Jabe," she said, gently pushing the girl before

her into the shop. The clogger went on banging at his leather

as if he had never heard.

"Jabe! Jabe! this is hur." But the clogger took

not the slightest notice, and Sam and Lige held their breath as they

watched the scene from the shadow of the Ingle-nook.

The visitor took the matter into her own hands. She

stepped round the end of the counter, avoided with a graceful little

motion that quite won Sam's heart the heap of clog-tops on the

floor, and coming close up to her sphinx-like uncle held up her face

and turned to the clogger two pretty pink lips to be kissed.

Sam was nearly bursting with excitement to see the crabby old

clogger who scoffed at all "sawftness" and hated anything in

petticoats kissing a pretty girl was the sight of a lifetime, and he

silently hugged himself to keep down his feelings.

For the first time Jabe seemed to become conscious of the

presence of his niece. He gave a guilty little start, glanced

in something very like terror at the sweet face so confidingly

turned up to his, turned his head away, hesitated, and went a shade

paler, and then, hastily drawing the back of his hand over his

mouth, he bent over meekly, received the proffered salute, and

hastily wiping his mouth again, went on with his work; whilst Sam

and his chum breaking into broad grins, stared amazedly at each

other, and dropped into their seats, fairly overcome.

A moment later their attention was once more attracted by

what was going on in the shop. Judy, to break the ice, had

commence to give her brother some details of their niece's journey,

when suddenly a clear, girlish voice broke in: "And oh! Uncle Jybus,

there was a fat man with three dogs all tied to strings." Off

the girl plunged into a long and excited description of a funny

incident she had met with on her journey. She opened her great

gray eyes and spread out her hands to aid her in depicting the

scene; then she showed a row of faultless white teeth, and rippled

out merry little laughs as she outlined the fat man's grotesque

appearance; next she spread out her skirts in a most bewitching

manner to give some idea of the proportions of her corpulent

subject; and when at last, out of breath and excited, she described

the final catastrophe of the fat man measuring his full length on

the platform of the station, whilst his dogs yelped and howled and

tugged at their strings and got more and more entangled, her pale

face was red with merry blushes, and her long eyelashes wet with

tears of laughter.

Sam and Lige listened like men enchanted the pretty grace of

her movements, her fine-sounding cockney accent, her perfect

naturalness, and the abandon of her acting were all so new and

delightful to them that when she finished her story they burst into

a long, loud laugh.

Jabe mumbled something about "numyeds," but turned away his

face to conceal a relishful smirk, and then, putting on a look of

terrible sternness, he looked at his niece with his fiercest glance,

and demanded, "Wot's thi name?"

"My name's Charlotte; but father calls me Doxie, Uncle Jybus."

"Doxie? Wot the hangment mak' of a name's that?"

"Oh! I like it, and so does mother! Don't you, Uncle

Jybus?"

But Jabe turned away to his work with an incomprehensible

grunt, and Sam and Lige suddenly remembered tea.

When they had got outside, however, Sam turned to the still

grinning Lige, and said impressively, as he punctuated every word

with his forefinger on the ex-road-mender's breast: "Liger, owd

Jabe's pipe's put aat! It's petticut guverment at th' clug-shop

fro naa—that's wot it is!"

And Lige drew his brows together, and staring from under them

into vacancy, he nodded his head with looks of sagacious

comprehension, and departed.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

THE CAPITULATION OF JABE.

ON the night of

Doxie's arrival in Beckside Jabe held out more fiercely than ever on

his favourite topic. His niece's coming provided him with an

excellent opportunity, and he made the most of it.

"Women!" he cried indignantly: "ther born contrairy. Wotivver yo'

tell 'em ta dew, they goo an' dew collywest."

This, of course, had reference to Judy's obstinate persistence in

receiving the girl in spite of his repeated protests.

"Ay! it's a bit awkert fur thee," said Sam, in affected sympathy.

"Me? Hoo'll ha' nowt ta dew wi' me, Aw'll tak'

cur o' that! Aw'll

show her." And he threw back his head in indignant defiance of Doxie

in particular and all other women in general.

"Hoo's noice sooart o' ways wi' her, tew," said Lige, after a slight

pause.

"Ways! Aw'll give her ways! Hoo'll come nooan of her connifogeling

dodges wi' me, Aw'll tell thi. Yo' sawftyeds hez aw bin collogued wi'

women's ways; but Aw'll show yo'!"

Poor Jabe! he kept up this show of defiance all night, and even

condescended to mimic the new-comer's manner for the entertainment

of his associates; and if this boisterous language was meant to

cover a masterly retreat, it was neither too soon nor too violent,

for in a short time he found himself in a parlous condition indeed.

For the next two days he saw little of his niece, but on the third

morning, when he went into the shop after breakfast, he found her

perched on a stool, and telling the apprentices a story which, with

the novel attractiveness of the teller, was so absorbing that they

did not notice the entrance of their dread master, and had to be

roused out of their enchantment by the sudden blast of his wrath. Jabe had two apprentices at this period, for Isaac was nearly out of

his time, and his successor had just been installed. But from that

hour they led him a weary life. It was easy for him to assume his

old ascendency when they were alone, but the moment Doxie appeared

they had eyes and ears for nothing else, and government, except in

so far as it is represented by abusive language, may be said to have

ceased to exist in the clog-shop. Then Doxie took to talking to Sam

Speck, and telling him secrets; and Sam was henceforth to be found

at the shop at any and every hour when there was the least chance of

the "Lundun wench" being around.

One day, about a week after her arrival, Doxie came to the cloggery

as usual and announced to her uncle that she was going to stay to

tea with him. And though this was the first time she had really made

any overture of a particular kind to him, and the moment therefore

when he could put his foot down once for all, the clogger simply

muttered a sort of surly grunt to himself, heaved a little sigh, and

tamely went on with his work. Presently Doxie adjourned to the

parlour to prepare the coming meal, and Jabe could hear her rattling

the pots and singing as though in triumph over her first victory. Then she called him to tea, and before he could sit down she

delivered him a little lecture upon the way in which, as she could

see from the teapot, his tea had been usually brewed, and carefully

instructed him in the latest London style of doing it; and Jabe

listened, or pretended to do so, meekly replying, "Ay."

Just as he was drawing his chair up to the table, the girl stopped

him, and, with a prettily affected sternness, demanded to know

whether Beckside gentlemen usually took tea in their shirt sleeves

and without washing; and Jabe, the valiant, unconquerable Jabe,

champion of freedom and defender of north country ways, muttered

something about forgetting, and limped humbly off into the scullery

to wash, calling at the parlour door on his way back to put on his

coat.

|

Before he could sit down she delivered him a little lecture.

|

Throughout the meal Doxie rattled and talked to her taciturn uncle

in the gayest manner, and he, furtively watching her every movement

from under his thick eyebrows, made no response except an occasional

inexplicable grunt. He was not giving in, he told himself; no, he

was not to be bamboozled; but all the same the tea lasted twice as

long as when he was alone, and even when it was over he lingered to

light his pipe, dropping into a chair for a moment to hear her

finish a characteristically graphic description of going out to tea

in London with her mother.

Doxie was certainly very unlike an ordinary Lancashire girl. Her

features were fairly regular, and her complexion almost colourless,

and there was nothing remarkable about her face when it was at rest; but it rarely was at rest. When she spoke, every word was

accompanied by corresponding changes of expression, which, though

slight in themselves, gave charm and piquancy to her face; even

when she was only listening to you, the quick-changing light in her

great gray eyes, the rising and lowering of her finely pencilled

eyebrows, and the constant play of varied expression around her

large but mobile mouth were so attractive, that as you watched her

you were in danger of forgetting what you were saying. When she

became animated, as she did upon the slightest occasion, her

feelings expressed themselves through every limb; and, as all her

motions had a strange, subtle grace, she was then an enchanting thing

to look at. Doxie's hair was of a dull, commonplace brown, but so

abundant that no ordinary chenille net, such as was worn by girls at

that time, would hold it, and it hung in thick clusters down her

back. Tall for her age, her many-flounced dress-skirt was, according

to Beckside fashion, disgracefully short, and her long, striped

stockings, though in the height of fashion in London at that period,

shocked the susceptibilities of Aunt Judy and her lady friends.

The night of the tea Jabe held forth at the clog-shop fire on the

weakmindedness of parents towards their children, especially those

who had only one child. From that he passed on to the frivolous

vanity of townsfolk in the matter of dress. Then he came by easy

process to the wiles and weaknesses of women, finishing with a

terrible tirade against Aunt Judy for introducing into Beckside such

a fearful example of "proide an' peertniss" as this newly arrived

niece. But Sam Speck took particular note that, except for the last

sentence, Jabe did not directly denounce the new-comer.

Thenceforward Doxie came more and more to the clog-shop, until, by

the end of another week, she had established herself there

altogether, except that she went home early in the evening and

always slept at her aunt's. And now Jabe's troubles began in

earnest. Early and late the shop was the scene of most disgraceful

"carryings on." Sam Speck came to the Ingle-nook every morning as

soon as Doxie arrived, and could not be driven away; whilst the

quiet of the place was broken every few minutes by his irritating

laughter at some word or deed from the "wench." The most provoking

part was that, whenever he was recovering from one of the outbursts,

he was sure to turn round and glance most significantly at the

clogger, to see how he was taking it. As to the apprentices, Jabe

was simply at his wits' end. If Doxie was near them, they could not

be kept at work in the daytime, and it was equally difficult to get

them away when "knocking off" time came at night. At her slightest

wish they would jump up from their seats, getting into each other's

way in their haste to serve her, and neither their master's strong

language nor his even more terrible glare had any effect. Jabe hated

cats almost more than he hated women, but one day Doxie appeared at

the clog-shop with two kittens in her arms which she had begged from

a boy who was going to drown them. A burst of wrath escaped the

clogger as he saw what was being brought to him; but when she came

round the corner and opened her arms to show him her treasures,

asking him whether they were not dear little things, Jabe glanced

helplessly at the pussies, gave a dismal groan, and turned away to

resume his work. The sputtering, smothered laugh which came at that

moment from the Ingle-nook where Sam and Lige were smoking was

unbearably tantalising; but if those two unsympathetic merry-makers

had seen the poor clogger standing helplessly upon his bedroom floor

in the dead of night, with one loudly mewing little wretch in his

hand and the other clinging nervously to his shirt tail and lifting

up its voice on high, they would have had cause for jubilation.

|

Jabe gave the fiddle a hasty kick.

|

A

day or two later as Jabe was just finishing for the third time a

rasping assurance to the new apprentice that he would "ne'er mak' a

clugger wo'll tha'll wik," a sudden sharp cry, followed by a loud

bang and a boom, was heard coming from the parlour, and the old man

jumped to his feet crying, "Lord, a massy! wot's that?" Then he

limped hastily across the shop floor, and burst into the parlour to

behold Doxie rising hastily to her feet with a great bump on her

forehead, whilst Jabe's cherished and incomparable bass-viol lay in

pieces at her feet.

"O uncle! I'm sorry! I am sorry!"

But Jabe gave the fiddle a hasty kick with his foot, and seizing the

trembling girl by the arm he dragged her to the window. "Maw wench! maw wench!" he cried, in great distress; and then, as Doxie

suddenly turned pale and was about to fall, he caught her tenderly

in his arms and cried with face all a-work to his apprentices, "Fetch

Judy! fetch th' doctor! Hoo's deein'! Oh! hoo's deein'."

But Doxie recovered herself and stopped the frightened lads,

declaring she was all right; and then she tried to laugh and got

away from her uncle, and, dropping into a chair, drew a long breath.

"O uncle! heaw bad of me! You cannot forgive me neaw, can you? I

shall never, never forgive myself."

For answer, Jabe got up and, giving another vicious kick at the

fiddle, went off into the pantry to fetch some goose-grease for the

girl's bruised forehead. Putting a little of it on the end of a not

too clean finger, and placing one arm round her neck, with infinite

gentleness he anointed the throbbing wound.

"Oh, that is nice!" she gasped; and then, throwing her soft arms

round the clogger's neck, and pressing her face against his, she

burst into a long, relief-ful sob.

Jabe bore this "cuddlin"' with remarkable fortitude, and to judge by

his looks would have endured more; but presently his niece let him

go, and once more began to express her contrition. But he noisily

broke in upon her confessions, picked up the broken viol, tossed it

upon the long-settle, and then commenced to lecture her. He began

cautiously enough, for this was confessedly a type of character with

which he was not familiar. Soon, however, he discovered that his

niece, so far from being unduly alarmed, was rather enjoying his

tirade; and now, sure of his ground, he launched out in his own

inimitable style. The recklessness of young people in the presence

of danger, the fearful consequences that might have ensued from the

accident, the risk of permanent disfigurement she had run, the

wisdom of taking heed to her elders, were all descanted upon with

due length and seriousness, the whole discourse being finished off

with a few pungent sentences on the folly and wilfulness of all

women, especially of young ones.

Doxie listened to the deliverance with ever increasing delight. She

had not before heard her uncle "read off," as Sam would have said. Her eyes, out of which the tears of penitence had scarcely departed,

shone with eager fun; her nods followed the clogger's points as

though she were supplying the emphasis; and when at last he

concluded, she burst out into a long, delighted laugh. From that

moment Jabe was unmuzzled. Hitherto some ideas of old-fashioned

hospitality had restrained him; but the accident of the bass-viol

at least had this good about it, that it assured him he was free to

talk as he pleased, so far as his niece was concerned.

His views about her sex greatly amused Doxie, and when she

discovered that he had opposed her coming and regarded her

presence as a trial from which he hoped speedily to be delivered, she

laughed more than ever; and whenever she was in danger of getting

dull, though to give the girl her due that was not often, she would

go into the shop, and, sitting cross-legged on a stool by the side

of Sam or Lige, would make a remark which she knew beforehand would

set her uncle off, and then sit and hug herself, laughing with

keenest delight.

In a few days Doxie was the most popular person in Beckside. Her

striking appearance and dress, her high spirits and frank, open

manners, her remarkable gift of mimicry, and a certain indefinable

daintiness of person, made her exceedingly attractive to the simple

villagers, and every day Jabe was treated to numerous compliments

about "yore Annie's wench." To all these the clogger replied with

loud scoffs and ironical sneers.

"Yo' en ta live wi folk ta know 'em," he would cry; and then with a

significant sniff he would add, "An' then yo' dunna know 'em —if

the'r women."

Now and again Doxie would overhear these choice sentiments; but she

only laughed the more merrily, and prophesied that her uncle would

end by marrying a widow. "Mother says such people alwiys do."

One morning, however, she came to the shop with a cloud on her face. "O uncle, isn't it a shaime?" she cried, as soon as she caught

sight of him.

"Wot's up naa?" he growled, in his surliest tones.

"I've to go home the daiy after to-morrow isn't it dreadful?"

"Thank the Lord fur that burst out Jabe. Wee'st ha' peace an'

quiteniss once mooar."

This brought the light back into Doxie's eyes, and as the fun

gleamed through a little tear she said coaxingly, "But ain't

you sorry a little bit, uncle, just a little, neaw?"

"Sorry! Aw am that! As sorry as a felley az gets aat o' Bedlam."

"But you'll miss me when I'm gone, won't you, uncle?"

"Miss yo'! Aw shall that! Loike Billy Twitters said to th' bums

when he paid 'em aat."

This kind of raillery went on the whole day, and at night Jabe, with

an exaggerated air of joyousness, boasted over the shop fire of his

coming deliverance; and though thereby he was confessing to having

suffered more than he would have previously admitted, yet,

regardless of consistency and everything else, he did his best to

convince his friends that he was unfeignedly glad of his approaching

escape from petticoat persecution. His recent experience seemed to

have aggravated unnecessarily his dislike for the opposite sex, and

before the evening was over he had out-heroded Herod in his

denunciations of their ways.

Next morning, when Doxie came as usual, he was worse than ever. "Only one day more! Oh, what a blessin'!" Doxie seemed inclined to

cry, and could not manage even a smile. Jabe seemed encouraged by

these signs, and surpassed himself in highly coloured descriptions

of the peace and comfort he was so eagerly anticipating. But had his

niece been less preoccupied with her own regrets, she might have

noticed how keenly he was watching her from under his shaggy brows.

Doxie spent the greater part of the day in making farewell calls,

but just before tea-time she came back to her uncle's looking sad

and tired, and quietly commenced to make the tea. Jabe drew up to

the table with a sly leer on his face, and in a moment or two gave

vent to a dry chuckle.

"Oh, you nawsty, wicked, hard-hearted man, you! When I do go I'll

never, never come back, so there!" But in spite of herself there was

a gleam of fun behind her sorrowful looks, and the clogger chuckled

again.

"Ain't you a little bit sorry, uncle—just a little bit?"

And the clogger gave his head a series of very emphatic shakes, and

cried, "Not me! Not me!"

"What did you maike me love you for then?" And Doxie's mouth began

to droop at the corners.

Jabe gave another loud, rough laugh; but if his niece had been more

observant, she might have noted that it was a mirthless exercise. For a moment there was a pause; Doxie looked steadily and musingly

at her uncle, and then, as the tears came in spite of her, she

dropped her head upon her arms and said, as she began to cry

quietly, "I didn't know you liked the fiddle so much, uncle."

Jabe was surprised; a gleam as of sudden enlightenment shot into

his eyes. "Fiddle!" he cried, with the utmost contempt; "wot's th

fiddle getten to dew wi' it?"

"I'm sure it's the fiddle," sobbed Doxie.

"Confaand th' fiddle!" And Jabe looked really angry for a moment.

But just then Aunt Judy came in, and seeing her favourite in tears,

and being at that moment wrought up to a high point of emotion at

the prospect of parting with the girl who had so entwined herself

around her heart, she drew herself up, fixed a stern eye upon her

brother, and for full five minutes poured out a long-accumulated

flood of indignant reproach upon him. Jabe listened to his sister's

tirade with a face of exasperating blandness. "Mon!" she cried,

"tha'rt nowt! that's wot thaa art! tha'rt nowt!"

Jabe threw his expressive leg over the other and laughed.

"Hert! tha's noa hert! thaa river hed! Thaa wur born baat, it's my

belief."

Again the clogger laughed.

"Tha's lived bi thisel', an' tha'll dee bi thisel', an' not a sowl

i' th' wold ull cur fur thi."

"Yes they will, uncle; I will, I will!" And Doxie, flinging her

arms around him, chair back and all, dropped her pretty head on his

bosom and sobbed as though her heart would break.

Jabe sat imprisoned in his chair, and looking like a man undergoing

a painful operation, whilst his little red eyes shone with a strange

moisture; yet never a word did he speak. Judy looked down on the

pair with wondering perplexity. Presently she drew Doxie away, and

bade her prepare to pack her box for going. Left to himself, the

clogger seemed unusually restless. He tried to smoke, but the pipe

went out as often as he lighted it. Then he stood up and took a

long, meditative look out of the window; and finally, feeling more

and more uncomfortable, he sauntered into the shop. Yet when his

friends assembled they found him moody and unsociable, and when Sam,

by way of feeler, expressed regret at the approaching departure of

Doxie, the clogger exploded into one of his most violent outbursts,

and altogether made himself so disagreeable that his companions were

fain to let him alone in silence. But this displeased him more than

ever, and turning his attention to the hapless apprentices he gave

them a most uncomfortable time of it.

Next morning Jabe was astir earlier than usual, and seemed more

irritable even than on the previous evening. Judy was so busy

getting her niece ready for departure, that she could not come to

the shop, and so he was left to prepare his breakfast for himself. Twice he went into the parlour to do so, but on each occasion he

fell into a brown study, and finally wandered back into the shop.

Presently word came from the cottage that the box was ready and

somebody must go to fetch it. Sam and Isaac started at once, and in

a few minutes came back with the package. A little later Aunt Judy

and Doxie, both seeming very miserable, arrived to wait for the

coach; and Jabe, carefully avoiding his niece's eye, sat down to his

work, trying to look as though nothing unusual was happening. Then

the coach was heard coming up the brow, and Doxie turned and gazed

distressfully at her uncle; but he would not see her. The

conveyance stopped opposite the shop, and Sam and Isaac came forward

to carry out the box.

"Wheer 't gooin' wi' that box?"

|

"Wheer t' gooin' wi' that box?"

|

It

was Jabe who was speaking; he had risen to his feet, and stood

glaring at Sam as though he had caught him in the act of stealing

it.

"Aw'm takkin' it to th' cooach fur shure."

"Clap it daan."

"Bud t' cooach is here."

"Clap it daan, Aw tell thi."

"Bud th' wench conna goo baat hur box."

"Th' wench is no gooin'."

"No gooin'?"

"Neaw, nur th' box nother."

*

*

*

*

"Naa then! arr yo' gooin' t' be theer aw day?" shouted Billy from

the coach box.

"Ay, an' aw neet tew," bawled Jabe in reply.

"Jabez, art maddlet? Let th' wench goo!" cried Judy, in sore

amazement.

"Judy," replied the clogger, turning to his sister and speaking in

slow, deliberate tones, "that wench is wheer hoo's stoppin'; hoo

coom ta pleease thee, an' hoo'll stop ta pleease me." Then as Doxie

flung her arms about his neck, the rugged old clogger drew her

gently to his side, and looking round defiantly at the astonished

company he cried, with a quaver in his voice, "Aw've fun wun bit a

gradely womanhood i' th' wold, an' Aw'm goin' t' stick tew it—bless

her!"

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV.

AN IRRESISTIBLE AMBASSADRESS.

WHILST the events recorded in the last chapter were taking place at

the clog-shop, a woman was seated before a small fire in the dingy

back room of a London lodging-house. She was respectably dressed,

and had a comfortable, cared for air about her; but her face showed

unmistakable signs of recent and severe suffering. She had turned

her back to the table, on which were the remains of a spare

breakfast, and was sitting looking sadly and dreamily into the fire. She held in her hand a letter, and glanced absently at it every now

and again. The woman was Doxie's mother, and the letter was the one

informing her why her daughter had not started for home that day. She held it loosely between her fingers, and turned it over with

mingled feelings.

When her husband had first communicated to her the condition of

their affairs he had, of course, made the best of it, and had

suggested that if they could manage to get Doxie out of the way for

a little while until things got settled again, she would probably

escape all the unpleasantness, and know nothing of what had taken

place when she returned. For some time Mrs. Dent had been

longing for the opportunity to become reconciled to her people, but

hitherto she had felt too much condemned for her own conduct to

attempt any approach, unless she could be assured that her brother

and sister were of similar mind. She discovered, however, that

her husband was not at all prepared to allow Doxie to go to

Beckside, and it was only under the pressure of their misfortunes

that he brought himself to make the suggestion. She found the

writing of the letter, humble though it had to be, comparatively

pleasant, and the prospect of a possible reconciliation to her

friends helped considerably to soften the severity of the sufferings

which her husband's circumstances had brought upon her. Aunt

Judy's prompt and simply affectionate reply further relieved the

situation, and in the preparations for Doxie's visit and the

anticipations connected with it she forgot for the time her own

grief. She had never before been separated from her only

child, yet she had such confidence that Doxie's sunny temper and

winsomeness would pave the way to the reconciliation she longed for,

that she parted with her daughter with something very like

eagerness.

But since the day upon which she saw her child off at the

station Mrs. Dent's sorrows had multiplied. Her husband

confessed that things were worse than he had at first supposed, and

one sad day the bailiffs came to mark the goods of their pretty

little home. Then everything had been sold, and they had come

into these shabby lodgings. What would Doxie think when she

came into them? Then in her wretchedness the lessons of

earlier and happier days came back to her, and poor Annie spent many

of her lonely hours in that little back room in prayer.

Her husband was as miserable as she was, and she suspected

that he was pining for his child. One morning when she awoke

she found to her surprise that he was not in bed at her side.

Where had he gone? Sometimes he rose before her and lighted

the fire, but the fire was untouched. She dressed hastily and

looked about her. His boots and overcoat were gone also.

Then her eye fell upon a little packet on the table. Her heart

gave a great jump, and with a cry of bitter distress she snatched it

up and began to examine it. It contained her husband's watch

and chain and about twenty-five shillings. Underneath these

was a little note, at which she eagerly caught, but dared not open.

"O Lord, ha' marcy! ha' marcy!" she cried, as she wrung her hands

and crushed the note in them. Then she sat down, and, after

sobbing a moment or two, opened the letter. This is what she

read:

DEAR ANNIE,―I

cannot bear it any longer. If I stay here I shall do away with

myself. Sell the watch and chain and do the best you can.

As soon as I have money I will send you some; but you will not see

me until I have a home to give you again. God bless you, my

dear lass, and our bonnie Doxie!

THOMAS.

Short as it was, Mrs. Dent did not read the whole of the

letter at once. Every sentence brought a fresh burst of tears,

and it was some time before she comprehended all it meant. She

did not blame her husband; in fact, that view of the case never

occurred to her. But she intensely pitied him. For days

she had watched him suffering under her very eyes, and in one sense

his departure was a relief. At length she got up and walked

about the room. Presently her agitation subsided, and she

began to think calmly what she was to do. Then she remembered

that Doxie was returning that day, and this broke her down again.

For over an hour she wandered about the room in agonised perplexity.

Suddenly she remembered that, put away in a box, she had five or six

pounds about which her husband knew nothing. It was so small a

sum that until lately she had not thought of telling her husband

about it, and since they had come into the lodgings she had decided

to keep it until the day of emergency. Now she reproached

herself with the thought that, if she had told her husband, he might

not have left her. This made her think of her failing, a

liking for secret saving, and it brought back to her mind the old

purse which she had carried away from home in the long, long ago,

and all other feelings were for the moment lost in a deep remorse.

Again and again she thought she could hear her oracular brother

saying in his stern way, "Be sure your sin will find you out."

Poor Annie! it was a bitter moment. Just then a clock

on the stairs struck two, and she was suddenly reminded that in an

hour or two Doxie would be there. Oh! what was she to do?

What would Doxie say when she found that her father was gone?

Yet she must be stirring; and so, absently getting ready, she went

to the station to meet the train. The day passed; through

trains from Lancashire were not so numerous as they are now, but,

having nothing else to do, and fearing almost to be alone, Mrs. Dent

stayed and met them all as they came in. The last train

arrived, and still no Doxie. She grew alarmed, and all other

troubles were for the moment forgotten in anxiety about the one whom

she longed and yet dreaded to see. A porter suggested that she

should telegraph to Beckside; but telegrams were much dearer then

than now, and she knew there was no telegraph office at Beckside.

Mrs. Dent did not go to bed that night, and was at the

station early next morning to seek her child. There she learnt

that two trains had come in during the night; she had not thought of

that contingency, and was nearly distracted at the possibility of

having missed her child. The friendly porter suggested that

she should go home and see whether Doxie had arrived during her

absence. It was a long way to her lodgings, but Annie did not

feel the distance. When she arrived, she found the room still

empty, and as a cry escaped her, and she was dropping into a chair

in sheer despair, her eye fell upon a letter propped up against the

little clock on the mantelpiece. It was in Doxie's

handwriting, and she kissed it and sobbed again for relief as she

turned it over and over. When she found strength to read the

letter, it contained the story of Uncle Jabez' sudden and peremptory

refusal to let Doxie return, and concluded with an urgent request

that she might be allowed to stay longer. It was this letter,

with its comforting and yet perplexing contents, which was in

Annie's hands when we introduced her to our readers in that little

back sitting-room.

The first feeling in Mrs. Dent's mind as she read the letter

had been one of intense relief at the safety of her daughter, and

that was deepened as she gratefully realised that at least for

awhile longer Doxie would be in comfort and safety. Presently

into her mind came a deep, overpowering longing. Doxie's

previous letters had been much longer than this one, and were full

of most entertaining particulars about Beckside, and all the

delights she was enjoying; yet none of them had stirred her mother's

heart as this had done. For a few minutes she felt as though

she must get up and set off to her village home, if she had to walk

every step of the way. She could imagine her irascible elder

brother suddenly putting his foot down, and refusing to let his

niece return. The clog-shop, their own little cottage, and the

little chapel came vividly before her mind, and she could see

herself standing in a Sunday-school class and singing "God moves in

a mysterious way." For a little time the feeling in her heart

was almost unbearable. Presently she slipped down upon her

knees, and although her thoughts did not form themselves into

definite prayer, she remained there quietly weeping, and somehow

deriving comfort and hope from the exercise.

A soft peace seemed to steal slowly over her heart as she

knelt, and when at last she rose to her feet, her face, though pale

and tearful, had a look of resignation and tranquillity. She

now found herself ready to face the situation. She herself had

sent for Doxie, but that was because she felt she could not remain

longer without exciting suspicion. Now Providence had

intervened, and the very thought of that gave her courage and

strength. Soon she had her plans formed, and proceeded to act

on them with the energy of her practical nature.

All her efforts were exerted to discover, without giving

grounds for suspicion, where her husband was. She proceeded

very cautiously. She had no mistrust of him. She knew

that he was of an active and enterprising nature, and would not be

long before he obtained some kind of employment. But day

succeeded day, and she gleaned nothing about the absent man,

although she used every means she could think of to obtain

information. Then she began to be depressed, and had to fight

night and day with a great longing to see her child; and this was

strengthened when in her next letter Doxie wrote an impulsive little

sentence which revealed that she was becoming home-sick. But

now the possibility of her coming home suddenly seemed to frighten

the poor mother; with a great effort she sat down and wrote a letter

in which she informed her daughter that they were expecting to

remove into a new house, and that she had better stay until the

bustle was over.

Meanwhile things were going on much as usual at Beckside.

Doxie, now that she had discovered her uncle's feelings towards her,

would gladly have entered into more affectionate relationship with

him; but she soon found that he had relapsed almost instantly into

his old manner, and repulsed her tentative caresses with all the old

gruffness, and received all her endearing words with impatient

scorn. She found, however, that he grew more and more

impatient of her absences from the clog-shop, and became quite testy

if she omitted to take any of her meals with him. A day or two

after his peremptory stopping of her departure he began to speak of

himself in depreciatory and abusive terms as an "owd sawftyed," and

sought, whenever Doxie was present, to convey the idea that he had

only relented out of foolish and weak-minded pity, and that he had

already most completely repented of it. Then he slid into the

habit of constant self-pity, affecting to regard himself as the

victim of most mysterious and undeserved misfortunes. "Plagues

o' Egypt!" he would say with expressive elevations of the eyebrows,

"th' trials o' Jooab! the'r' nowt tew it." Both Doxie and all

others who heard him were left to interpret for themselves what the

"it" meant.

As the days grew into weeks and Doxie still remained, Aunt

Judy began to grow uneasy. It would be a great wrench to her

whenever "th' little wench" left them, but every day she could see

that Doxie was getting a stronger hold upon her uncle's affections,

and there was no telling what outrageous thing he might do if the

parting was deferred much longer. It would not surprise her,

in fact, if he refused to let her return home at all. Then it

occurred to Judy that her sister was strangely easy about the

continued absence of the child. Had the girl been hers, she

reasoned, she would have had her home long ago. She made no

account of children staying so long in strangers' houses, it made

them discontented with their own. Then the letter about the

removal came, and it struck Judy as being rather strange that the

Dents should remove twice in less than three months. The next

letter that Doxie received contained a sentence which made her

aunt's heart sink and opened her eyes. It was only a word or

two, but to Judy it was a covert, yet none the less distinct, bid

for reconciliation. "Oh how I should like to peep just for

once at the dear old home!" wrote Annie. Judy felt a sinking,

as she phrased it afterwards, and in a few minutes she had come

perilously near to guessing the truth.

At any rate Annie was in a much humbler mood than usual, and

evidently would like an invitation to come home. Yes! and

Doxie had been sent to Beckside as a peacemaker. Judy smiled

to think how effectually her niece had done her work. But what

had brought about this remarkable change? As she turned the

thing over and over in her mind, and recalled all the circumstances

of the case, she came to the conclusion that the Dents were in

trouble and needed friends.

"Haa mitch lunger art goin' t' keep yond' wench?" she asked,

turning round and looking at her brother as she was leaving the

clog-shop parlour next morning.

"Me? Me keep her! Well, that's a good un!"

And the clogger stared at Judy and laughed with an elaborate

affectation of amazement.

"Then hoo'd bet-ter goo next wik, aar Annie 'ull be

fret-tin'."

"The sewner the better."

It was no use talking to Jabe, and Aunt Judy lapsed into her

own uneasy musings and departed. But a day or two later Judy

discovered that Doxie herself was beginning to grow restless, and

without much trouble she ascertained that the girl was longing to

see her parents. At the same time she could not get rid of the

feeling that something was wrong in London. For two more days

she brooded over these things, and then went to consult her

unfailing friend, Mrs. Ben, the carpenter's wife. That good

woman recommended that Doxie should be told, and left to settle the

matter with her uncle. But Judy shrank from that course, and

so they consulted the carpenter. After tantalising his wife by

a long and provoking pause, during which he did nothing but stare

before him, and puff away at his pipe, Ben advised that Annie should

be sent for, and introduced into the clog-shop unexpectedly.

Judy was not very confident of either of these courses, and took

more time to reflect. Then the matter settled itself.

Next morning Doxie was somewhat late in starting for the

clog-shop, and consequently was still in the house when the postman

came. Hitherto Judy had contrived more by luck than anything

else to get her letters when Doxie was absent, and thus she got to

know their contents before she showed them to her niece. But

this morning the girl herself went to the door, and handed the

letter to her aunt with a look on her face that showed the elder

woman that it would be cruel to keep the news from her.

Moreover, Judy was not good at reading writing, though she had so

far managed with Mrs. Johnty Harrop's help to get to know the

contents of the letters before Doxie learnt of their arrival.

The letter when opened proved to be so long and so closely written,

and Doxie looked so very impatient, that Judy handed it to her to

read, though not without misgiving. Doxie had not commenced to

read aloud, but was just glancing over the first few lines when she

uttered a cry of alarm and went exceedingly pale. Then she

read on without in the least heeding Judy's eager enquiries, and

again a cry of pain escaped her. "O mother! dear, dear

mother!" she cried, and as her eyes filled with great tears she read

hungrily on.

"Wot is it, wench? wot is it?" cried Judy in terror; but

Doxie stepped mechanically back, as though to get out of her aunt's

reach, and went on reading greedily.

"O father! father!" she cried with a fresh burst of weeping,

and once more resumed her perusal of the painful missive.

It was the full utterance of poor Annie's heart.

Lonely, miserable, and sick at heart, she had at last become

desperate, and throwing discretion to the winds had written to her

sister a full statement of their recent troubles and her present

miserable condition. Doxie read it through with tear-blinded

eyes, and then when she had finished she stepped back, and putting

her hand to her side she cried out piteously, "O auntie, I shall

die!" For fully half a minute she stood looking wildly at her

aunt, and then suddenly rushing to the door she darted off up the

hill to the clog-shop.

"Come back wi' thi, come back," cried Judy; but the fleeing

girl was already half-way up the "broo." "It's happen better

sa," murmured Judy, as she realised how hopeless was the task of

catching her niece, and then she went indoors again and waited

developments with a heavily beating heart.

Meanwhile Doxie had burst in upon the clogger like a

whirlwind. He was seated by the fire talking to Sam, but in a

moment she had caught him round the neck and was pouring into his

bewildered ear the whole distressful tale. All that took place

at that memorable interview has never been known, for even Sam saw

that it was something very serious and discreetly took himself off.

Half an hour later, however, Doxie left the shop with a new light in

her eyes and ten pounds in gold in her hands, and that day a

registered letter was sent to London with full directions for the

lonely watcher there to come to Beckside at once.

The next two days passed over very slowly, and it would have

been difficult to say whether Doxie or her uncle was more restless.

On the morning of the third day the post brought the expected

letter, and a little later Doxie and her aunt started in the coach

to meet Annie. Jabe ate no dinner that day, and as the time

for the arrival of the coach drew near he became painfully agitated.

"Aw've seen th' owd lad i' monny a pucker," Sam Speck

confided to Lige and Ben that night, "bud Aw ne'er seed him nowt

loike that."

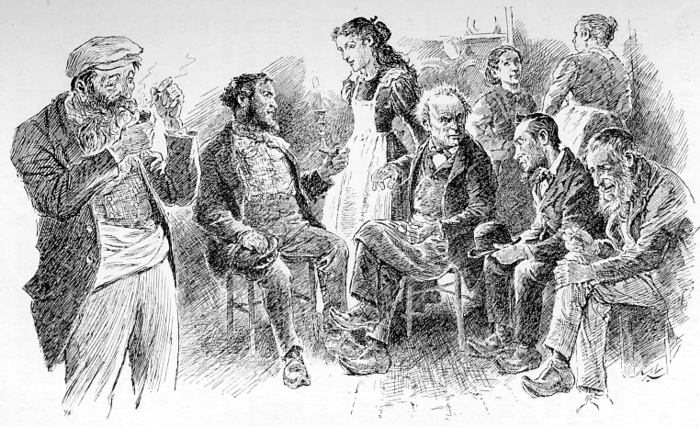

|

"Aw've seen the old lad i' mony a pucker . . . . bud aw ne'er

seen him nowt loike that."

|

Five minutes before its usual time the coach was heard coming

rumbling down the "broo." The clogger was as pale as death.

A moment later the door was burst open and a bright, eager voice

cried, "Here she is, uncle! here she is!" But she was not

there, she was only getting out of the coach.

Jabe rose to his feet, and his legs positively shook under

him. Without turning his head he glanced out of the window

towards the coach. He was dimly conscious of two female

figures coming towards the door, and then he heard Judy's voice

saying, "Here hoo is, Jabe."

A pale, trembling woman, with a haggard, sorrow-stricken

face, moved slowly towards the counter, and Jabe, tardily lifting

his eyes, looked into the face of his sister. The silence of

that moment was deathly.

"Well, lad," stammered the sister.

And Jabe, trying vainly to keep control over a quivering

mouth, faltered out, "Well."

There the two stood opposite one another, but not venturing

to look at each other, and Doxie, who was watching with eager eyes,

was about to burst in with some impetuous remark, when Jabe took a

slow step towards his sister, and held out a stiff hand. Annie

snatched at it eagerly, and if she had been a lady would doubtless

have put it to her lips; but being only a Lancashire woman after

all, she gripped it as with the grip of death, and held it over the

counter.

"O Jabe, Jabe!" she cried, in tones of bitter penitence,

"I've been a great sinner." And Jabe turned his head hastily

towards the window, and replied fervently, "It's nowt towart wot

Aw've bin." And Doxie, to whom these things were not

only altogether incomprehensible, but also altogether out of place

in a glad reunion, put her red lips together, and making a grotesque

and lugubrious face at her uncle, murmured in exact imitation of the

new Brogden curate's tones, "So are we all, all miserable sinners."

And as the clogger began to laugh through his tearful eyes, she

cried, in her imperious, though to him always delightful, way, "And

now, uncle, we are all going to stay for ' baggin.'

|

Polly, put the kettle on,

And we'll all have tea." |

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

UNBLUSHING HYPOCRISY.

NOW the little

black door that divided the clog-shop from the parlour was about as

plain and uninteresting a construction as ever filled an aperture,

but on the night of Annie Dent's return to Beckside it came in for

an amount of interested attention that would have filled with pride

a much more pretentious article of the kind.

Sam Speck, who came into the shop just as the tea-things were

beginning to rattle in the parlour, eyed it over from his place at

the fire with a most curious and impatient stare. Next he went

and sat down beside the new apprentice, who was working at the back

window, and, whilst he asked fitful questions of that worthy every

now and then, he scarcely attended at all to the answers, but became

absorbed again in his contemplation of the door. Presently he

got up and walked up and down the shop, stopping each time and

scrutinising the latch as he passed. Then he took a long,

abstracted stare into the fire, and, finally, unable to bear it any

longer, he affected to remember something which he ought to have

told the clogger earlier in the day, and enquired earnestly from

Isaac whether he thought there would be anything wrong in him

knocking at the parlour door and speaking to Jabe about it whilst it

was in his mind. Isaac did not think there would, and so Sam

stepped over and was just about to tap, when his heart suddenly

failed him, and he hastened on tip-toes back to the fireplace.

After a moment or two, however, he tried again, yet once more

hesitated; but this time without leaving his place before the

terrible door. Then he began to make all kinds of grotesque

faces at the door, and sudden stabs at it as though he was only

wavering as to where exactly he should assault it. Finally,