|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER XIII.

NETTY'S DIPLOMACY.

NETTY

SWIRE'S

brothers were strong-minded though narrow men, with perhaps more

than their share of that high pride of character so common in the

upper ranks of the working classes. They were, however, solid,

unimaginative souls, and had no little of that stern severity and

pharisaic intolerance of human weaknesses which so frequently

accompanies a spotless personal record. What was, therefore, a

characteristic escapade to their neighbours assumed in their eyes

the proportions of a crime, and deeply-wounded pride and sullied

family honour made them bitter and unforgiving; and they watched

their old father with jealous eyes, lest, as they expected, he

should show signs of relenting. They were, moreover, confirmed

bachelors, and their sister's disposition, the reverse of their own,

had strengthened their original prejudices; and so, in the proud

confidence of perfect ignorance and inexperience, they decided that

no woman should henceforth cross their threshold: they would do the

necessary domestic work themselves. Three or four days of

actual experiment, however, shook their confidence somewhat, and

they proposed that their father should stay at home and keep house.

But to this the old man offered peremptory resistance, and they

could not conceal from themselves the fact that his continued

estrangement from his only daughter was making him querulous and

obstinate. They had sternly forbidden him to mention Netty's

name in their hearing, and though for a few days he obeyed, he soon

began to make oblique and hesitant references to her, which only

inflamed their anger against the culprit. Then Johnty came

home one night with the information that Netty was scandalously

happy, or pretended to be, and openly gloried in what she had done.

This in his indignation he blurted out before the old father, whose

long, pathetic face took on a harder look as he listened.

Later the same evening they saw him drop a novel of Netty's into the

fire and force it down with the poker. But domestic

discomforts were beginning to tell upon them, and their frequent

mistakes—ludicrous enough under other circumstances—made them

fretful and peevish with one another. To go home to a cold

house, have to prepare their own food, and spend their precious

leisure hours in "messing," woman's work, was not to their minds at

all, and the old man sighed and moaned about the house until they

could scarcely bear themselves for ill-temper. Meanwhile their

hitherto spotless house grew dirtier, and they began to understand

that their sister, working in the mill during the day and attending

to household duties at night, had had no mean task.

They had both been kept away from the week-night service one

night, and even when supper-time came and the old man had gone to

bed, they had not finished their unwonted and unpleasant tasks.

Dirty, disgusted and miserable, they sat over a small fire partaking

of a makeshift supper of bread and cheese. The coffee had been

made in a mill breakfast can, and they cut for themselves at both

the loaf and the Cheshire.

"I'm sick o' this: we cannot go on i' this way much longer,"

grumbled Johnty, and petulantly tossed a bit of cheese into his

mouth.

"What's done's done," was the surly reply, and David blew the

floating grounds from the top of the coffee and took a cautious sip.

"Huh!" he cried, and glared with unutterable disgust at his

brother.

"There's no sugar i' t' house," responded Johnty, sulkily.

"Sup, man! what's a bit of sugar?"

David put down the can with cynical resignation, and munched

moodily at his cheese and bread.

"We mun have a charwoman, that's what we mun have," remarked

Johnty at last.

"Ay, as 'll break one half o' t' stuff and steal t'other."

"They're not all thieves."

"No, some on 'em 's sluts."

Johnty glanced across the table as though he would have liked

to annihilate his brother, and then he appeared to want to say

something, but could find nothing crushing enough, so he held his

peace.

David, quite as wretched as the other, seemed to find

malicious satisfaction in tantalizing him, and so he said presently:

"Thou'd happen like to fetch her back."

"I should find thee soaping up to her when I got theer if I

did."

The argument was getting perilously near to the explosive

point, and so David curbed himself, looked round on the heaps of

unwashed pots on the side-table, and from them to the cinder-choked

fire-grate, and muttered gloomily:

"We shall have to go i' lodgings; I can see nothin' else for

it."

"T'owd chap 'ud look well i' lodgin's, wouldn't he?"

And Johnty was losing his temper, and all the more so because his

brother's biting jibes had so much palpable truth in them.

"Talk sense, man; we mun do summat."

"Ay, there's one thing might do—that is, thou might."

"What's that?"

"Get married!"

"Get married? Me? Thou means thyself?"

"Me?"

"Ay, thee; thou'rt t' oldest."

Johnty stared fiercely at his brother for a moment, then rose

haughtily to his feet, and stalked off upstairs stamping heavily

with his feet as he went, to emphasize his disgust.

Two days later David gave in, and went in search of a

charwoman; but those to whom he applied had some sort of amazing,

but sneakish sympathy with George Stone, and outdid each other in

the decisiveness of their refusals, one of them going so far as to

say she would see them fast first. He succeeded at last in

obtaining the services of old Ann Crawshaw, who was to go and

"fettle up" for them on Saturday morning.

But when the brothers approached the house on the appointed

day they met the old woman hurrying breathlessly down the lane, and

incoherently denouncing all Methodists as hypocrites and wastrels,

and a few steps further they beheld their father standing in the

doorway, shaking his head threateningly, and brandishing a

ferocious-looking stick after the retreating charwoman.

Another miserable week-end passed, during which David remembered a

distant relative, who was a widow, and suggested that she should be

negotiated with. But Johnty, remembering an affair of the

heart with this same lady, and realising that she was still of a

dangerously likely age, reluctantly explained that the thing was not

to be thought of. Meanwhile the old man was pining visibly,

and they expected every day that he would either break out and

insist upon a reconciliation, or, what was worse, go and interview

Netty himself.

On the Monday night the three came home from work together,

and as Johnty, key in hand, approached the door, the old man lifted

a weary sigh that ended in a quivering sob. The brothers

turned and fixed him with stern, forbidding looks. The key was

turned, and they passed one after the other into the house.

Johnty pulled up with an exclamation, and as the others ranged

themselves alongside, they beheld a pile of newly washed

clothes—clean, mangled, and folded. Johnty gazed stupidly at

them, and then turned inquiringly to his brother. David

returned the stare with interest, the old man's eyes suddenly lit up

with sweet, eager light, and he started forward towards the bundle.

Then he stopped and drew back, looking with wistful shyness into the

sour faces watching him, and then put out a trembling hand, and

gently stroked the clothes, as though the bundle had been a pet dog,

and as he did so he murmured, "It's her! Bless her! it's her."

In their surprise they had not noticed that the fire was burning

brightly, the kettle singing on the hob, and the fire-irons gleaming

with their old-time polish, but when they had taken in all these

things a pregnant silence fell upon them, and the sons had to hide

their faces from the old man's wistful, beseeching eyes. They

sat down to tea with brooding looks, but their father seemed

possessed with unaccountable restlessness. He got up from the

table and paced about the room, he went to the bundle of clothes and

turned them over, one by one, with caressing fingers and dim,

brimming eyes. Then he stared out of the window, blinked his

eyes rapidly, turned abruptly to the staircase, and as he toiled

heavily up, they heard him muttering, "Joy in the presence of the

angels! Joy in the presence of the angels!"

The brothers spent a long, uncomfortable night, each prepared

to suspect the other of weakness, and each expecting momentarily to

be accused of it himself. They did not think it necessary to

speculate as to who had come to their assistance, nor even to ask

themselves how she had got into the house. They went about

their unpleasant household duties in sullen silence, and each

retired to rest inwardly resenting the fact that the other had not

even spoken on the topic uppermost in their minds.

They had drifted into the habit of living upon "bought"

bread, for obvious reasons, and took their meals to the mill with

them, so that they only returned at night, the house being locked up

all day. But when they arrived next evening, at their now

unattractive home, they found a batch of bread, newly baked, lying

upon the sideboard, a tea-table with a white cloth set in the middle

of the room, the kettle boiling on the hob, and a great plate of

buttered toast on the fender. Next to the toast stood another

pile, containing oven-bottom cakes. Now, these cakes were old

Abe's special dainty, and the delicate compliment entirely broke him

down. He stared mistily at them and then at the table, stood

for a moment shaking with inward emotion, and then, lifting a

haggard face and gazing at his sons with eyes streaming with tears

and blazing with desperate defiance, he cried, "Oh, bless her!

God bless my little lass!"

The sons, knowing both Netty and her husband, more than

suspected that this was one of his contrivances, but they glanced at

each other and hurried away, one into the scullery and the other

upstairs, to conceal their faces, and as soon as he was alone the

old fellow, after a furtive look round, dropped upon his knees

before the fire, bent his white head as low as he could, and

reverently kissed the fragrant cakes. And then with his face

in his hands he sobbed out, "Was dead and is alive again, was lost

and is found."

Fearing what he might do if he got the opportunity, the

brothers did not let the old fellow out of their sight for a single

moment, but he grew more restive and querulous as the night wore on,

and they were only too thankful when he went off to bed, denouncing

them vaguely as hard-hearted and unforgiving children. They

were prepared to find Netty in the house when they came home next

night, and when she was not, the old man spent the evening toying

tenderly with a pair of scissors that had been his daughter's.

He looked so old and wistful that it made them wretched to look at

him, and each wondered to himself how long this sort of thing would

last. On Friday night, as they now half expected, they found

the cottage bright and speckless, as they had been wont to see it in

other days; the windows even had been cleaned, and fresh curtains

added. But there was a change in their father; he seemed to be

impatient for his food, and took little heed to the signs of

tidiness, but ate his meal with reckless haste. Then he went

upstairs, and came back presently dressed in his Sunday best.

The brothers looked at each other with significant and resigned

glances, and David hurried into the scullery, where Johnty followed

him.

"Let him go," grunted David, and immediately plunged his face

into the wash-bowl to avoid argument.

It never seemed to occur to any of these self-absorbed men

that Netty, being married, could not return, and so the sons saw

their father depart in the confident expectation that he would bring

his daughter back with him. But the now all-desirable

reconciliation was not to be, for on his way to "Squint Hall" old

Abe met a couple of villagers who would not be put off with his

hasty nod, and in a quarter of an hour after his setting out he

staggered back into the house reeling like a drunken man. When

he recovered from a long faint he retailed what he had heard, and

next afternoon being Saturday, Johnty, with hard, set face, spent

his time putting new locks on the doors and patent catches on the

windows, whilst David was journeying to Lopham to fetch cousin Ann.

And whilst the Swires were struggling with these unpleasant

experiences, the schoolmistress was constructing a theory about

George Stone and his mad marriage. He had a strong brain,

plenty of shrewd, Lancashire common sense, a full share of those

nobler impulses which are the common heritage of youth, and certain

whimsical notions of honour, which were the results of his

environment, and manifested themselves with that bewildering

eccentricity so common in such natures. But underneath all

these surface excellences was that deep, strong, slow-working, but

unconquerable force of heredity, which was so much more powerful

than all the rest, and would assert itself with increasing power as

his character developed. Yes, he might have been made as an

illustration of the meaning of heredity, and these odd freaks of

his, so perplexing and disappointing to those who wished him well,

were simply, according to the doctrines of her scientific

authorities, volcanic eruptions of the sub-conscious self, and

explained perfectly the apparent inconsistencies and

self-contradictions so perplexing to ordinary people. The

theory gave her much intellectual satisfaction, but unfortunately

created a hopeless feeling, against which she somehow felt her

better nature rebelling, which will perhaps reveal to the reader a

fact she would have stoutly denied, namely, that her interest in her

"subject" was no longer exclusively intellectual.

As a set-off to this disappointment, however, she was

enjoying a complete triumph over her old adversary, Mr. Lot

Crumblehulme. The tripe-dresser had been very eager to inform

her of George's inclusion in the list of converts at the recent

Methodist revival, and had boastfully prophesied that as, according

to a generally accepted opinion amongst Methodist experts, converted

wastrels always made exceptionally devoted Christians, she would

soon see George one of the pillars of the Church. But the

doctrine of conversion was one of the "superstitions" from which she

had been emancipated, and nothing delighted her more than to be able

to demonstrate its inadequacy by actual example. George's

case, therefore, seemed made for the purpose. The Methodist

doctrine of conversion supposed a total change of character and

conduct, but it seemed to her that natural disposition, environment,

and other such circumstances explained the differences in people far

more naturally and perfectly than any theory of supernatural

revolution. George Stone had been converted one week, and had

rushed into the most ridiculous of marriages the very next week; and

therefore there could have been no such total change of character as

conversion was supposed to produce.

Poor Lot was at his wits' end, the wedding had knocked all

his foundations away, and the clever little lady in the parlour had

him at her mercy.

"But Mr. Crumblehulme, what is conversion?" she asked for the

twelfth time during a long evening's wrangle.

"Conversion! Conversion's being born again."

"And what is being born again?"

"Regeneration."

"Yes, but what is regeneration?"

"Regeneration is a—a—you think you've flabbergasted me, but

you haven't—regeneration is con—con—conversion!" And the

baffled old man, conscious of his failure, broke helplessly down.

"Exactly! which brings us back to our starting-point.

But don't you see you are only making things worse? This

wedding is bad enough in George the sinner, but in George the saint

it is an incongruous absurdity."

Lot gaped at her in helpless dismay; but pity for a beaten

foe, and a feeling of delicacy in dwelling upon what she knew was

one of his cherished doctrines, prompted her to change the

conversation, and so she broke the awkward silence by asking in a

changed voice—

"Mr. Crumblehulme, what is the first thing you remember about

George?"

"T'fost?" And Lot, glad enough to escape the dilemma

into which she had forced him, and hopeful of something turning up

in conversation which might give him an opportunity of revenge,

puckered his brows for a moment and then went on. "T'fost time

I iver seed the young scamp to my knowledge, he was standin' outside

t' school door, and old Abe Swire was coaxing him to come in with a

red-cheeked apple."

"And did he succeed?"

"He did that—and rued it, I can tell you!"

"How?"

"He fought two lads in t' school and two more out, because

they laughed at his old woman's shoes 'at were twice too big for

him."

The mistress smiled.

"And did he stick to the school?"

"He's never been as much as late since, and, mistress"—Lot's

confidence was returning as he spied a new argument—"it's been t'

Sunday-school again' his blood and bringing up ever since, and thank

the Lord t' school's won!"

"Won?"

"Ay, won! Isn't he converted? Where's your logic,

where's your skeptikism now?" And for a moment Lot looked

almost triumphant.

"And the first sign of his conversion is this marriage?"

The defiant look on the old man's face slowly faded, his

brows drew together, and his eyes wandered furtively over the

opposite wall. It was no use; no argument that was even

plausible would come, and so, with a sudden spring and a flirt of

his coat tails, he flung to the kitchen door, crying, as he vanished

with a dramatic gesture of repudiation, "It is better to dwell in

the corner of a house top than with a brawling woman in a wide

house!"

And the schoolmistress smiled indulgently as he vanished, for

she knew that only the direst sense of defeat would have betrayed

him into such unintentional rudeness.

CHAPTER XIV.

GEORGE'S DISCOVERY.

GEORGE

STONE lounged into

Mollins Station in his usual easy, careless manner. He was on

his way by the early train to Manchester on business for the firm.

He had a cigarette between his lips, and his hands were deep in the

pockets of a light, country-made overcoat, whilst a smile, half

pleasure, half surprise, played about his strong mouth. As the

train came up he opened a carriage door and threw himself indolently

into a corner seat. He had the compartment to himself, and

tilting his hat over his eyes, was soon lost in thought.

"Well, this is a topper," he murmured to himself presently.

"You can just do what you like with women if you soap 'em.

Just fancy, little flipperty-flopperty Netty trying to be a decent

wife! It's a scortcher!" He mused a moment or two, and

then went on: "I shouldn't be surprised if she were to be converted.

My stars! if it weren't for t'other, I should fall in love with

her."

Pursuing this train of thought for a time, he presently broke

out "The grace of God can do anything, and—blow heredity!"

Then his face grew serious: his thoughts were dwelling on

something else, evidently. "A bonny man I am, to be married to

one woman and loving another!" And then he added, with a

deprecatory laugh, "Wouldn't she turn her proud little nose up if

she only knew!"

This new turn in his thoughts occupied him for several

minutes, during which the slow train had stopped at a station.

As it began to move again he muttered, "I wish she'd get married and

done with. Jerusalem! I could make anything of Netty—and

myself. Anything!"

His head sank deeper into his chest, his hat began to slide

over his left ear; but just as it was falling, he sprang up and

caught it, crying as he did so, "Scandalous! George, thou's

made thy bed, and thou must lie on it. What's the use spending

thy days crying for the moon?"

But at this moment the train pulled up at the junction, and a

shabby-genteel young fellow started for George's compartment; but

when he perceived who its occupant was he would have gone further,

only George raised his head at that moment, so he stepped sheepishly

in with a monosyllabic salutation. The new-comer took the seat

that was farthest away from George, and threw his feet on the

opposite cushion, whilst a half-timid, half-insolent sneer gathered

round his lips.

He had lost his place some time before as warehouse clerk at

the Mollins mill, and knew that George had benefited by his

misfortune.

"Well, t' old shop isn't busted up yet!" he said in a piping

but truculent tone; but George merely settled himself in his comer

again in a manner which announced unmistakably that he did not

desire conversation.

The man at the other end of the carriage eyed him with sour

envy for a moment or two, and then, with a mocking leer, said, "By

gum! but it will do afore long."

George did not yet appear to hear.

"Nobbut let t' old chap shuffle off this mortal coil, and the

blooming consarn won't last a twelvemonth."

Still George held his peace.

"Yond' fly Mr. Tom's running a bonny rig as it is."

From under the brim of the tilted hat came a gruff, "Thee let

him alone."

"I'll the Hanover as like! I know what I know. He

bets and races, and he's head over ears in debt this minute."

It seemed as though George was not going to reply he might

have been asleep for any sign he gave—but suddenly he pushed his hat

back, leaned forward, and fastened his eyes relentlessly on the man

on the opposite seat, freed his great hands with a terribly

significant little movement, and then said quietly:

"Mathy, if thou mentions that name again I'll send thy soft

head through those boards!"

Matthew moved uneasily and shrank back into the corner,

wriggling every way to escape those terrible eyes.

"Well, I nobbut—"

"Hush, Mathy; Mr. Tom and me used to be pals. If ever I

hear of thee as much as turning his name over, thou'll rue it! mind

that."

It was rough enough talk, but George evidently knew his man.

The two settled into their corners again in sullen silence, and it

looked as though the episode had ended. But Matthew, conscious

of possessing a piece of information which would excite his

companion, could not restrain himself; and so, after several

preliminary wriggles, he said:

"I were nobbut talking. Some folk 'ud give a lot for

what I know."

A threatening glance was the only reply, and the

secret-burdened man had another fit of restlessness. Unable,

however, to entirely repress himself, he ventured presently:

"He's lost hundreds at St. Leger; and I know summit worse

than that a fine sight!"

"What dost know?"

"Oh, ah, I dare say!"

"What dost know?"

"Never mind! I know."

With the easiest possible sang-froid, George rose to

his feet, deliberately buttoned his overcoat, and let down the

window sash. Then, with a quick movement, he turned upon his

man, seized him by the front of his vest and the knee of his

trousers, and lifting him up until his head was half through the

window, he commanded sternly:

"Out with it!"

Limp, panting and terrified, Matthew begged to be released,

and then, with George standing over him, he told his sordid tale.

He was now employed by a firm of accountants and money lenders in

Manchester, and had seen young Mr. Bradshaw in the office, and by

prying and searching had discovered that a deed belonging to some

property of Miss Bradshaw's had been left with the firm, presumably

as security for a loan. Before they parted George had bound

Matthew over by threats, as rough and terrible as the ones he had

already used, to keep the secret he had divulged; and when he left

him he went out of the station staring hard before him and colliding

every minute or two with some person on the pavement. By the

time he reached the warehouse he had seen as deep into the mystery

as he was ever likely to do, and spent every spare moment of that

day in painful, anxious broodings over it.

The fact that Mr. Tom had gone to such a firm spoke clearly

enough of the secrecy of the transaction. It was most

evidently some dire necessity, and just as clearly something that

must be kept from the old master. The deeds he supposed could

not be pledged without some note of hand from Miss Jessie, and that

she should need it for her own use and not be able to obtain it from

her father was absurd on the face of it. Miss Jessie was

helping her brother out of a difficulty, and if Miss Bradshaw had

kept her own deeds the transaction might pass without discovery.

But that he knew was highly improbable, and if, as he felt certain,

the document was kept where the old man kept the family deeds as

distinct from his business ones—in the old safe at home—then any day

the absence of this one might be discovered, and Miss Jessie

involved in the disgrace of her brother with the head of the house.

And yet Miss Jessie must have known all this when she

consented to the use of the documents in this way. Did she

know the risk she was running? and would she have incurred it if the

case had not been a desperate one? Deeds of property,

especially when they belonged to rich people like the Bradshaws,

were often left undisturbed for years; had Miss Jessie and Tom

calculated upon this? That nothing but very real difficulty

would have prompted them to this it was easy to see; but he knew, as

few others in Mollins knew, that if the transaction became known to

the old master there would in all probability be a rupture, the

relations between father and son being already sufficiently

strained.

He was devoutly thankful to have the information supplied by

Matthew Drabbs, only the difficulty was to decide what use to make

of it now he did know. He might easily do more harm than good

by meddling, and there might after all be a natural and easy

explanation of the affair which would show him up as a prying

busybody if he interfered. No; it was nothing to him, and any

Mollins man would have told him so if he had been consulted, but

somehow George felt dreadfully miserable and was conscious of a

strange, wild longing to have possession of that deed. It was

characteristic of him that he thought of all sorts of wild,

desperate plans to get the thing into his hands, or, better still,

safe back in the Highfield safe; for this strange fellow had one

strong, unquenchable passion in his heart. His juvenile

acquaintance with Tom had brought him under the notice of the

family, and his smartness in his work had made him a favourite with

the master, and the little favours thus bestowed had created within

him a dog-like devotion of which they were wholly unconscious.

When he returned to the mill that day, one of his first

discoveries was that the young master was doubling his original

holiday, and would not return for some five or six weeks longer, and

this increased his uneasiness as it increased the chances of

discovery. Then he thought of writing to the absent one

himself, and was only deterred by the reflection that in his present

mood Mr. Tom would be likely to tell him to mind his own business.

He sighed as he wondered what could have turned the heart of his

young master against him.

As he drew up to the tea-table at "Squint Hall" that night,

Netty without a word put a letter into his hand, and, glancing at

it, he noted that it bore a foreign postmark and was directed in the

scrawling hand of Tom Bradshaw, which, of course, Netty knew as well

as he did. He slipped it carelessly into his pocket as though

it was something he had expected, and a mere business affair which

could be attended to in business hours, and immediately began to

chaff both his wife and old Lyd. The women were both waiting

upon him, and he flattered them so mendaciously that they laughed

and buzzed about him in pure delight, and though Netty was consumed

with curiosity, his easy manner and the fact that when he had

finished his meal he drew up to the fire and lazily lighted a pipe,

led her to conclude that it was some mere business message which

would keep very well until he went to the office next day. Had

she been less happy she might have noticed that her big husband's

pipe went out now and again, and his answers to her questions were

somewhat absent and irrelevant; but to have him for her very own and

to see him so contented and merry, was happiness enough just then to

her. Her love to her husband and its strange realisation were

fast transforming her, and she was becoming a grateful, devoted,

sweet-minded little woman, under the spell of a wonderful affection.

About eight o'clock, however, George took up the evening

paper, tucked it under his arm, and strolled off to the little

church-shaped summer-house. Netty watched him wistfully as he

went, evidently hoping to be invited to accompany him; but he did

not notice her looks, and went away, candle in hand, to his retreat.

The air was somewhat damp, the summer-house smelt musty, but George

noticed neither the one nor the other, but setting the candlestick

on the little deal table and dropping upon a rustic bench, he drew

out the letter and hastily broke it open.

"―― Hotel, Vienna.

"Dear George,

"You will be surprised to get a letter from me, but the fact

is, I am in a hole—not the first one, you will say. I paid

some accounts before I left, which I did not expect to have to meet,

and it left me very bare. It is dreadfully expensive out here,

and I am about hard up. I cannot ask the old man, and I cannot

leave this place until I have something to pay my shot with.

You helped me out of scrapes many a time in the good old days when

we were lads together, and you were always a 'cute hand with the

bawbies. Could you let me have a hundred pounds, or even

fifty, at once? I will return them with jolly good interest

when I get home. Don't fail me—you never have—for old

sake's sake.

"Yours as ever,

"TOM B.

"P.S.—Address, Poste Restante, Vienna."

George read the letter over every line, and over again, dwelt

on every line, grudged greedily its brevity, and turned it over and

over again in search for something which he felt he missed.

Then he explored the recesses of the envelope, and finally laid the

two down on the table side by side, and fell to musing dreamily.

The significance of the letter was unmistakable, and its bearing on

the question of the abstracted deed clear. Tom was in extreme

financial difficulty, and after what had occurred between them

recently must have had a bitter struggle before he brought himself

himself to write that note. That he remembered how Tom had

treated him, that his young master would be as distant as ever when

he returned, he was prepared to admit, and yet as he sat there his

strong face softened strangely, and he rapidly blinked his eyes.

Pleasure and pain were chasing each other in his mind, his mouth

hardened, and then relaxed again, his face grew stolid and even

solemn, and presently great, unmanly tears began to roll down his

cheeks. He did not move, he seemed even to enjoy the presence

of these signs of weakness, and allowed them to remain and dry on

his face. For some time he sat, sunk in deep, anxious thought.

The tear-marks had almost dried, his eyes began to blink rapidly,

there was a slow, convulsive movement in his great body, and staring

hard before him he cried, through a fresh gush of tears, "Bless him

God—God—bless him!"

Another moody, dubious fit—harder thoughts were uppermost

evidently; he gave them place with a vacant, staring face, and then

sweeping his hand over his face, he cried, with a quivering pathetic

repetition, as of one listening to old-time music: "For old sake's

sake! For old sake's sake!" It was a weak, womanish way

of acting; George was still a simple rustic, but the thoughts behind

that struggling face were not the thoughts of a weakling, as we

shall see.

But at that moment he caught the click of the garden gate,

and a patter of light feet on the gravel path, and snatching at the

candle he held it to his mouth, and then, just as the door opened,

he gave it a puff, sprang hastily forward in the smoky darkness,

caught the struggling Netty in his arms, and starting down the path

pressed his face to hers, and trumpeting an old Lancashire love-song

on her glowing cheeks as he went, carried her laughingly back to the

house.

CHAPTER XV.

UNEXPECTED PROMOTION.

A SLEEPLESS

night, during which he debated schemes too extraordinary and violent

for anybody but himself, brought George no relief. His plan

for getting back Miss Jessie's deeds was sufficiently quixotic, but

Mr. Tom's letter brought complications that strained his ingenuity

to the utmost. Upon the house he had recently bought he might

raise perhaps two hundred pounds, or even sell it for what he had

given, but that would entirely exhaust his resources—and where was

the loan for his young master to come from? That must be sent

off at once—that day if possible—but if he did that, what was to

become of his other scheme? It was not so pressing, perhaps,

but he knew he would never be able to rest until it was disposed of.

His pre-occupation did not, however, prevent him anticipating

criticism as to his over-night's sleeplessness, for as soon as he

appeared downstairs he commenced a wonderful, highly diverting, but

strictly imaginary description of a marvellous dream he had had, the

moral of which was that he was very much in love with his wife,

though he elaborated and prolonged the story so lengthily that this

last fact did not appear until he was already at the door and out of

reach of playful assault.

As he went down to the mill he began to ask himself what had

taken place within him; he was conscious of a curious sense of

responsibility and importance; the task he had undertaken, though at

present apparently insoluble, seemed to have awakened something

within him, some dormant faculty that made him curiously conscious

of a larger equipment. The total effect was bracing, strangely

enough, and he looked more self-possessed even than usual as he

entered the mill gates. As foreman warehouseman, his time was

now spent partly at the mill and partly in Manchester, and he was

liable to have to pass from one place to the other at almost any

moment. He worked at his desk for a while with feverish

energy, vainly endeavouring to keep pace with his many rushing

thoughts. Just as the dim outlines of his actual plans began

to shape themselves before his mind, he was interrupted by a most

disturbing diversion. He was summoned to speak with his

master. Hot and perspiring, with rolled-up sleeves that

exposed strong, sinewy arms, he strode to the office with an air of

impatience.

"Well, sir?" and he held the office door in his hand as a

sign that he was in a hurry. The mill-owner turned round in

his revolving chair, ran his eyes deliberately over him, much as a

horsey squire might inspect a favourite charger, and then turned,

with a quizzical twinkle in his eye and an eyebrow slightly raised,

to a well-dressed, gentlemanly man who was standing in the room.

This was Appleyard, the firm's chief Manchester man, and as his eye

fell upon George a look of impatient annoyance and disgust passed

rapidly over his face, giving way gradually to one of impenetrable

blankness.

"Well, sir?" demanded George again. The curtness that

comes of excessive zeal for business was never resented at Mollins

Mill, especially by the owner. Mr. Bradshaw was evidently in

exceedingly good humour, amused and tickled about something, and so

he glanced from Appleyard to George, and from George back to the

salesman, and chuckled consumedly to himself. A reluctant grin

appeared on Appleyard's face, but George was frowning darkly.

Their employer watched them narrowly, with increasing enjoyment;

evidently he was having the joke all to himself. At last he

motioned to George to come in and shut the door. With the air

of one taking a part in a performance he disliked, George did as he

was told, whilst the salesman turned away with a disgusted,

protesting shrug of the shoulders. He was clearly of opinion

that there was something wrong with the old master this morning.

"Has thou ever had a top hat on?" asked the employer of

George, with a decorous face, but wicked, mirthful eyes.

George glared with indignation, and Appleyard stifled a groan.

George's "No!" was almost rude, but Bradshaw was so absorbed in a

careful inspection of George's person that he did not heed the tone.

Appleyard was still staring out of the window and

endeavouring to conceal his disgust, when the mill-owner, studying

him relishfully for a moment, suddenly got up, stepped into an inner

room, returned with his own silk hat, and placed it upon George's

head. It was some sizes too small, and covered about as much

of his head as a lancer's cap does of his. Stepping back, head

on one side and brow knit, the old man surveyed the effect with

elaborate mock gravity, and then, as much to cover rising laughter

as to continue the experiment, he cried: "Why, it's too little,

Appleyard! Ay, and by shot, my shoes 'ud be too little for

that rapscallion—eh? Oh, ay! lend us yours."

The dignified salesman's hat, thus summarily confiscated,

fitted better, and, to complete the effect, the old master took off

his frock coat and bade George put it on, the salesman grumbling

audibly the while and protestingly, shaking his head. The

master was in high feather; he walked round his victim again and

again, offering appreciative remarks, and grinning and winking at

Appleyard every moment. But George, standing stiff as a wax

figure, and gradually growing red in the face, could stand it no

longer, and so he cried—

"When you've finished with this tomfoolery there's some cloth

wants getting off."

The mill-owner chuckled slyly at Appleyard, chuckled again

all to himself, and then, taking the hat and coat from George, he

commanded—

"Be off with thee, get thy cloth out; but don't leave the

place till I send for thee."

When the warehouseman had gone, Bradshaw dropped into a

chair, helped himself to a cigar, signalled to his salesman to do

the same, and then, as he held the light ready for his weed, he

said—

"He'll be the handsomest fellow on that Exchange, bar none!"

"But, Mr. Bradshaw, you don't—you don't really mean it?"

And behind the deferential remonstrance even the master could detect

chagrin and rebellion.

"Don't I, by Jove? but I do! Why, man, properly rigged

out—as he shall be—he'd fetch orders like winking."

"But a country bumpkin! It is an insult to the

Exchange!" And Appleyard would dearly have liked to add, "and

to me."

"Insult! Ay, it is an insult! Why, man, before

he's been on those flags a month there'll be some of you won't have

a chance!"

"Oh, patience! What are we coming to!" And

Appleyard, losing at last all self-control, flung the band of his

Havana into the fire, and began to pace irritably about the room.

Bradshaw blinked his eyes contentedly, and smoked coolly on.

"You might have a bit of consideration for me; it's a

humiliation! I—I shall be the laughing-stock of the trade."

"Don't be an ass, Appleyard! He'll sell more stuff than

you, and get better prices too;" and then, as he glanced at his

companion, he cried in angry surprise, "Great Scot, man! you are not

jealous?"

The salesman did not answer for the moment, perhaps he

couldn't trust himself; but presently, with a grieved, remonstrant

look, he murmured, "I don't want to leave the old— "

The master ripped out an oath.

"Shut up, simpleton! You've been here twenty years, but

no man alive shall hint at resigning to me." And then, after a

slight pause, he went on conciliatorily: "You can take another

hundred a year if you like, but have him I will! "

The advance of stipend thus offered considerably mollified

the salesman, though his face was still troubled when he resumed his

seat opposite his employer.

"You don't know him, Appleyard; if ever business was in a

man's blood it is in his. Why, man, he'd sell wooden nutmegs;

he can't help it!"

For a quarter of an hour longer they talked, one as certain

as ever that the suggestion was a mad one, and the other unmoved in

his determination to have it tried.

"It is the best idea I've had for many a day," said the

principal, to finish the discussion; and then he added, with a half

coaxing kick at Appleyard's foot, "Let's have the wastrel up, and

get a bit of fun out of him!"

As he rose to ring the bell the salesman made a wry face, but

Bradshaw settled himself in his chair with the air of one preparing

himself for enjoyment.

George, hat in hand now for his journey to the town, opened

the door, looking more impatient than ever, and the master eyed him

with tantalising insolence.

"Put that hat down and shut that door."

"It's train time, master."

"Hang the train; do as you are told."

With a grunt of protest and a demonstrative glance at his

watch, George obeyed and came up to the side of the table, Appleyard

scrutinising him as he did so with growing discontent, and old

Bradshaw eyeing him sideways with ever-increasing mirth. For a

few moments the young man stood waiting to be questioned, and

presently the master, taking the cigar out of his mouth with extreme

deliberation, surveyed him with mock seriousness, and then said—

"I'll tell thee what, that moustache of thine's coming on

rarely!"

"It's more than you can say of my day's work," was the surly

reply, and, as his hands went to his watch chain again, he added,

"Is that all you want with me?"

This was, however, the sort of impatience that went right to

the commercial soul of the mill-owner, and so, still staring hard at

the warehouseman's upper lip, and speaking with an exasperating

drawl, he went on—

"It's fair curly at t'end; thou'll have to have it waxed."

George, inwardly fuming and counting the minutes, looked

unspeakable anathemas on all moustaches and all frivolous employers,

but dared not trust himself to speak. Watching him slyly with

twinkling eyes, and evidently greatly enjoying himself, the old

master dropped into a jeering tone and asked—

"What's the price of spot cotton, George?"

George's face flushed, but he did not reply.

Bradshaw, inwardly hugging himself with pleasure, now turned

towards the salesman, who was trying to catch George's eye to assure

him that even he was sorry for him.

"This is a bonny man to get wed, isn't he?" asked the master,

giving his head an indicatory fling towards the fuming warehouseman,

and then he added, entirely ignoring Appleyard's deprecatory frown,

"They say he's married the wildest little besom in Mollins."

Appleyard expected an explosion, the old master was evidently

playing for it; but George was staring hard through the window and

apparently did not hear.

The master turned his back upon his young employee, stared at

the fire-grate for a moment, and then, with a mischievous glance at

his Manchester man, he jeered—

"They've turned him out of the Sunday-school now, and he's

going ding-dong to the devil, they say."

Appleyard began to despise George—he had no spirit at all.

It was a great mistake not to stand up to the chief.

"It caps me that the hands don't turn out again' him, and

strike to have him sacked. He's a disgrace to the village,

they say."

Still the victim did not reply, and the puzzled salesman

thought he caught a little smirk of fun in the corner of the

badgered young fellow's mouth. Did he, too, see some hidden

joke in this sort of thing?

But at this moment there was a knock at the door, and some

one opened it to say that George was wanted in the warehouse.

Happy to escape, George turned to depart, but the master snapped out

curtly—

"Stop where thou art; Dick, go and tell Flint I want him."

George moved a little to relieve increasing impatience,

whilst his employer put on a terrible frown and glared hard at the

salesman. Flint having presented himself, he was gruffly

ordered to return to the warehouse and take George's position as

foreman, and when, after an effusive but unheeded burst of

gratitude, and a sly glance at the man he was supplanting, he

vanished, a dead silence prevailed in the office, and Appleyard,

nervous and bewildered, began to hum a Sankey's hymn. Two or

three times the old man looked round at the younger man, but nobody

spoke, and the culprit had just assumed something of his old manner,

for he just seen the train steam out of the station.

"Well, what art standing gaping there for?" And the

employer looked the picture of sternness.

"I'm waiting for orders."

"Orders? Thy place is shopped; isn't that orders

enough?"

No answer.

"Well, art na going?"

"I'm no' going neither for you nor anybody else. I'm

where I'm stopping."

Bradshaw glared fiercely at his defiant subordinate, and then

turned upon Appleyard a face glowing with triumph. It reminded

the salesman of nothing so much as the foolish pride of an

over-indulgent parent, when a child has said an amazingly impudent

but precocious thing.

Then the master's manner changed. He rose from his

chair, strode across the room to the safe, took out a cash-box,

selected three bank notes, and handing them carelessly to George he

commanded—

"Thou goes to town by the next train and gets a swell rig-out

from old Stamp—silk hat and all." And then, after scowling at

him for a moment, he went on: "Thou gets a second-class contract to

town, thy hair cut, thy brains washed and thy moustache curled, and

gets ready to go 'on 'Change,' by next Tuesday."

"Me! The Exchange! What for?" And George

was fairly knocked over for once.

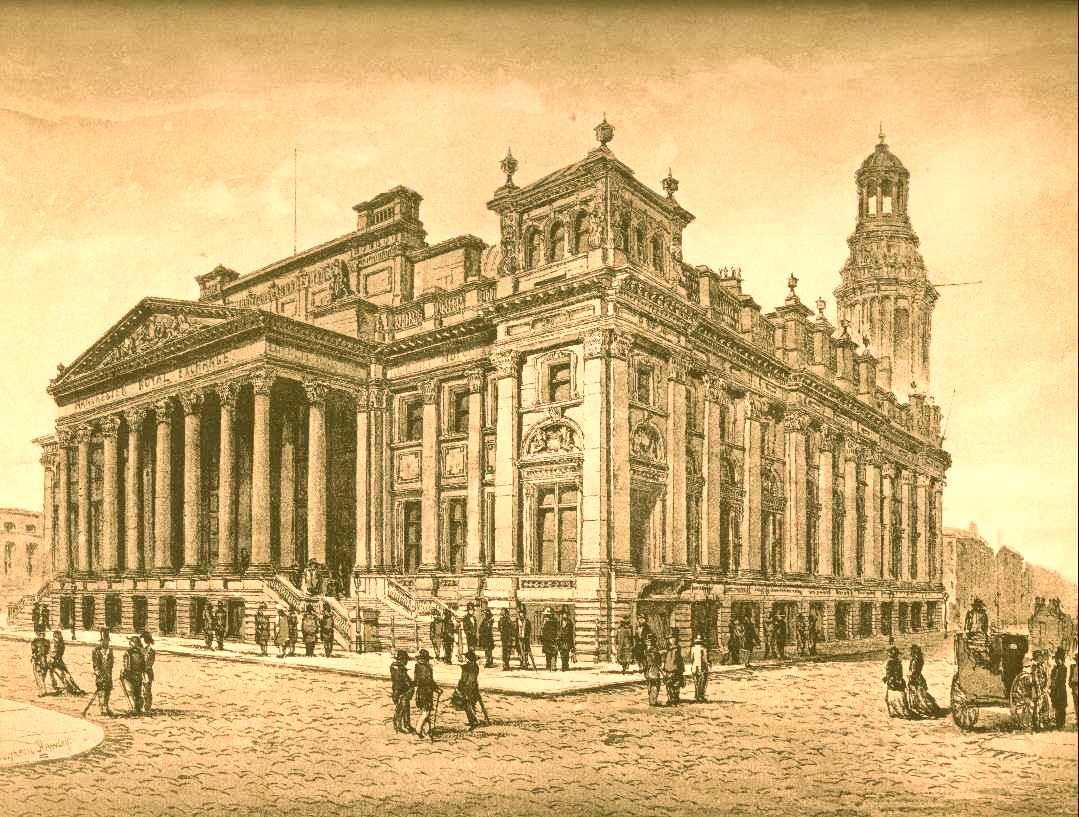

Manchester Royal Exchange

"What for? to sell calico; what do folks go there for—to play

dominoes?"

"But me—on the Exchange!" and George was a picture of

distress.

"Ay, thee; thou's been grumbling at the stocks long enough.

Thou mun go and sell 'em now."

"But, master! Me? It's ridiculous!" And

whilst his face expressed most genuine dismay, there were curious

twitching movements about his mouth, which the old master was

watching keenly.

Appleyard was mollified; George was displaying a most proper

sense of the importance of the work he was required to do, and the

salesman was just opening his mouth to speak when the master broke

in—

"Come, be off with thee; thou starts at five pound a week,

and we'll reacon about the commission after. And mind thee!

No more street corner and bar-parlour work. Good morning,

Mr. Stone!"

But the young employee was not quite so easily disposed of.

Utterly unexpected though the promotion was, he had the same curious

sense of something awakening within him which he had had before that

day, only this time it was more distinct and unmistakable. At

the same time the height to which he was thus suddenly raised was so

bewildering and the responsibility involved so serious that he was

deeply concerned, and entered another earnest protest. But the

master would have none of it, and though the wrangle was long, and

to Appleyard very instructive, the old chief would have his way, and

George finally left the office in a much limper condition than if he

had been actually discharged.

"Appleyard," remarked the mill-owner by way of summing up the

situation after George's departure; "there are some fellows who seem

to be made for success and get it, but they cannot carry corn; and

there are some others that are broad-bottomed, so to speak, and get

steadier the more you put on 'em. Yond' chap is of that sort;

give him nowt to do and he'll do nowt and ruin himself at the

bargain, but the more you weight him the faster he'll grow and the

steadier he'll get."

George's face was preternaturally solemn when he returned to

the warehouse, and he was mopping his face as he entered to remove

the dank moisture that had gathered. All eyes were turned upon

him in mournful sympathy and every voice suddenly hushed. For

half-an-hour the workmen watched him as he imparted to Flint the

information necessary for a proper discharge of his new duties,

glancing the while at each other and signalling the changing phases

of their own feelings. It was too palpable to be unnoticed,

and George, in spite of his preoccupation, became gradually

conscious that there was something forward, and immediately

exaggerated his own mournfulness. "Well, chaps," he said,

glancing round comprehensively as he turned to leave, and flipping

half-a-crown upon the packing-table, "here's for good luck!

Keep your peckers up; the best of friends must part."

With an unsteady sort of cheer the men sprang forward to

shake him by the hand. "Ta-ta, old lad, ta-ta!" they cried,

and the separation seemed to threaten to become pathetic, but just

as he was leaving, George, with the door in his hand, put on a look

of owlish gravity, drew down the lid of his left eye just far enough

to puzzle and not pronounced enough to illuminate, and then

vanished, leaving them to speculate for the rest of the day whether

this parting salutation was mere bravado or a sign of undeveloped

hope.

CHAPTER XVI.

THE SCHOOL HOUSE FIRE.

THE next two days

were the busiest George Stone ever spent. Late in the

afternoon of the day of his promotion he obtained a secret interview

with Jessie Bradshaw, terrified her by revealing what he knew about

the deed, and then obtained her consent and assistance in the plan

he had formed for its recovery. Jessie could give him little

help in the way of money, but her gratitude touched his soul, and he

went away from Highfield envying the happy man who should succeed in

capturing the affections of so sensible and true-hearted a young

lady. Then he managed somehow to sell "Squint Hall" for sixty

pounds, and posted fifty immediately to his young master, with a

letter full of apologies and regrets that he could not send more.

The larger sum was, of course, more difficult to negotiate, but

having Miss Jessie's note of hand about the deed he felt confident

of success, and at last, though he had to trump up a specious story

of haste in order to get ready money, he sold his new house again

and was thus prepared for his next move. He was not ignorant

of the danger he ran, but his was not the nature to over-estimate

things of that kind, and so he presented himself at the accountants'

in Manchester with a note, written on the lithographed memorandum

form of the firm, requesting in curt, business-like terms that the

deeds recently deposited with them should be handed to the bearer,

who would pay the mortgage and all other charges and give a receipt.

George's sudden appearance at the office scared Matthew

Drabbs, but it also facilitated the business in hand, for Matthew

identified him as representing the Bradshaws, and thus lulled

suspicion. That same night, dressed in his new clothes and by

special order from the old master, George presented himself at

Highfield, where the mill-owner abruptly introduced him into the

drawing-room and enjoyed the perplexity, surprise, and amusement of

his daughters when they discovered who their father's visitor really

was. This led to the first official announcement of George's

promotion, and when, after staying an hour, he finally departed,

escorted unfortunately to the gate by the old man himself, he missed

the opportunity he had hoped to obtain of handing the deed, which

had given them both so much anxiety, to Miss Jessie. And

whilst these two were parting at the gate, Lena Bradshaw was amusing

her sister by declaring, with characteristic impetuosity, that their

departed visitor was simply the handsomest man she had ever seen,

and that it would not be her fault if Mollins was not scandalised

ere long by the elopement of a mill-owner's daughter with a married

man.

Meanwhile, the subject of their terrible prophecies was

making his way home, regretting only that the precious deed was

still in his pocket. He arrived at "Squint Hall" in such high

spirits that he kept Netty and old Lyd in screams of laughter, as he

burlesqued the way in which he had genuflected and otherwise played

the gentleman in the Highfield drawing-room. When his

womenfolk retired for the night he set the cottage door open for

coolness, and sat down for a final pipe. The night was calm

and sultry, and for the time of the year somewhat unusually dark.

The soft stillness was favourable to meditation, and George gave

himself up to pleasant cogitations upon his recent great advance in

position; his joy, however, being mingled with a certain

regretfulness, which he seemed to regard as exceedingly

reprehensible, for he tried almost angrily to suppress it.

Presently, however, it struck him that his success was too perfect,

and he began to cast about in his mind for that inevitable "stone in

the other pocket," which he expected would soon enough present

itself. He was busy painting day-dreams of the future, not too

rosy it would appear by his looks, when he raised his head and began

to sniff the air. The sensation passed, however, and his

thoughts were slowly returning to the old topic, when he heard a

woman scream, and there at the top of the stairs stood Netty, crying

earnestly, "George, there's a fire somewhere!" and before he could

reply, his ears were assailed by a deafening b—u—z—z!

With an alarmed exclamation he sprang back, made a hasty

search for his boots, snatched the first coat that came to hand, and

hurried into the lane. The buzzing sound, though seldom heard,

was well known enough; it was the mill fire-buzzer, and the works

were on fire!

In a moment he was rushing down the slope to the cross roads,

and there looking over the wall he glanced round, before, behind,

and above him, but there was no sign of smoke. Then he heard

hurried feet and shouting, but as there were still cries of fire, he

darted back up the hill, and taking the turn at the end of the road

was soon at the mill gates. All was quiet; nobody seemed to be

coming his way, and so he flung himself heavily against the stout

doors, but they did not move, and there was no response.

Suddenly there was a flash of light, a flickering shadow danced for

a moment on the wall above his head, and wheeling round he

discovered there, on the shoulder of the hill, silhouetted against

the dark sky, was the Methodist School-house enveloped in thick

clouds of smoke, weirdly rimmed with flickers of light. He was

half a mile away, and out of breath, but with a fresh cry of alarm

he dashed up the hill, and was soon threading his way along the

bye-streets to the scene of destruction. Now the shouts became

clearer, and both men and women were in the road. The buzzer

had stopped; pattering feet and clamouring cries were heard on every

hand, and he reached the top of the lane and sprang towards the old

school. Then there was a roar, a flash of light, and houses,

walls, and faces suddenly shone with a lurid illumination.

That it was already too late to save the dear old building

was clear to George the moment he took in the situation; the glass

in the little window panes was crackling and flying in all

directions, and the hungry flames had already made a great hole in

the roof, through which smoke and flames were pouring. The

mill fire-engine was already on its way, and the men were making

preparations for its reception, and lamenting in loud tones that the

factory hose-pipe would never reach from the dams to the school.

Little bands of school officials were making futile efforts with

buckets, and women were standing in groups further back wringing

their hands and excitedly egging on the workers. The old place

was very dear to some who looked on, and their distress was pitiable

to see. Half-dressed men rushed about, getting into each

other's way, and yelling contradictory orders one to another; for

the most part doing nothing after the noisiest and most frantic

fashion.

George was conscious of twenty different impulses urging him

to as many different actions, and as he stepped back for a moment he

heard a loud thumping at the front door of the burning building: men

were evidently trying to break it open. Then a shrill,

peremptory, woman's voice was heard from the rear of the bystanders,

and the thuds stopped. In a moment he was in the middle of the

crowd, and beheld the intrepid little schoolmistress, arrayed in a

dressing-gown, standing near the front of the building, commanding

the excited men back. Realising her meaning at once, George

sprang to the front.

"Back, chaps, back!" he cried; "she's right! if you open the

door it will let the air in. Back with you!"

In a moment he had taken command, and the men turned away and

seized the little fire-engine, which had just arrived.

"Save the school! Save the school!" the women were

screaming. "The houses! the houses!" cried another party, but

as the crowd in the lane was now pushed forward to make room for the

apparatus, George glanced round for a moment, darted behind a knot

of screaming women, flung his arm round the schoolmistress, who was

much too near the building for his liking, and presently set her

down near the engine, saying breathlessly as he did so—

"There; superintend that!"

Crash! went the flag-tiles on the school-house roof, and a

fresh burst of lamentations broke out over the crowd. The fire

had commenced evidently in the second story, the lower one so far

remained dark, but now a dull glow began to show there also—the

upper floor was on fire.

The schoolmistress began to protest to the pumpers, but just

then some one shouted "Gas!" and George, picking up a stone, dashed

round to the back premises, where a loud banging soon told that he

was knocking up the pipe on the outside of the meter. It was

rough, hurried work, but when he came back the upper room was all

ablaze, and shone like a mansion of gold. There was still much

shouting and excitement in the direction of the fire-engine, but no

pumping, and the bucket men were standing staring aghast at the

terribly beautiful spectacle. George was looking about for the

teacher again, but she was nowhere to be seen, and on the spot where

he had left her stood a figure which attracted his attention.

It was an old man, who had evidently only just arrived. Stiff

and still, with white, appalled face, fright-dropped chin, and

glazed eyes, he was gazing spell-bound at the devouring flames,

whose flickering light played on his face and made it ghastly.

He saw nothing, heard nothing, knew nothing, but that the roaring,

shining temple of flame before him was the dearest spot on earth.

Old Abe Swire—for he it was—was beholding the destruction of that

which was more than life itself to him. George stared at the

touching figure until his eyes went wet, for there was that in him

which gauged the feelings of the old man more accurately than any

other soul there. Another roar of flame, and the crashing of a

chimney down upon the roof and through the burning floor to the very

basement attracted George's attention for a moment, but as he looked

a flash of thought caused him to turn round and stare stupidly at

the old superintendent. Then he glanced at the burning

building, looked calculatingly back once more at old Abe, and then

all at once flung off his coat, sprang lightly forward, leaped up

and caught the sill of a window in the lower story, and began to

pull himself up.

"Stand back! stand back!" cried a score of male voices, and

then pitiful, wailing, woman's tones, crying, "George, George!" and

coming clearly from Netty, were heard; but he was already on the

sill, and was breaking the glass to get at the window latch. A

rattle of glass, a puff of smoke that blinded and nearly choked him,

and he pushed up the window, and amid shouts that were almost

shrieks, sprang down into the vestry and vanished. Netty

uttered a quick succession of ringing screams, the women standing on

the bank of the lane re-echoed them, and in a moment every other

interest was forgotten, and the crowd swarmed forward in the

direction of the window through which young Stone had disappeared.

A perfect chorus of hoarse expostulations were shouted, and cries of

"Madman! lunatic!" were heard on every side. "Pray, men,

pray!" wailed out old Abe, awaking to consciousness at last.

Three tense, terrible minutes passed, horror sat on every face, a

score pairs of scared, fascinated eyes were fixed on that now tragic

lower window. A creak, a sharp tearing crack, and part of the

roof came crashing down into the interior, whilst a howl of terror

went up from the agonised watchers. Suddenly the spectators

checked their cries, and held their breath; there was something

moving at the window. The smoke was still pouring out of it,

but something thicker appeared—a man's head, a great bulky body came

out of the thickness, and drew itself up for a leap. He had

difficulty in balancing himself. Ah! what was that in his

arms? What could he have taken that reckless, perfectly insane

plunge into smoke and fire for? Simply the old school-desk

Bible, precious for its eighty years of service and the signature of

a Wesleyan President of the Conference on the flyleaf! That

under one arm, and the framed portrait of old Abe Swire, the senior

superintendent, under the other

As he jumped safely down, and, black as a negro, strode back

towards the crowd, the half-formed cheer died away on men's lips,

incredulous surprise stood on several faces, whilst not a few gave

vent to exclamations half amazement, half disgust. Netty, her

light hair streaming down her back, sprang at the framed portrait as

though in her frenzy to smash it. George, with both arms

occupied, stepped aside to avoid her onslaught, and walked away

shyly, hanging down his head, and with a foolish grin on his sooty

face. The crowd parted to let him pass, and he walked up to

the spot where old Abe still stood spell-bound. "Thou reckless

fool!" cried two or three of the men as he passed. "Thou

champion man!" shouted an elderly woman, with glowing eyes and wet

cheeks. "It's going! it's going!" cried several, as the going

water from the engine at last began to spout out upon the hissing

building, and a rush was made again for the scene.

Only a little group was left about George, and he, sheepishly

enough, held out the rescued treasures to old Abe. The

patriarch did not seem to see him, but stared fixedly at the burning

school. There was a pause, the women standing round held their

breath, the old man moved his glassy eyes, fixed them solemnly upon

his son-in-law, held out his arms in mute request for the picture;

but suddenly changing his mind, he flung his arms round the

blackened George, and then dropping his head, and resting it on the

Bible now hugged to his heart, he cried, "Thou'rt a better man nor

me, George Stone, a fine sight better!"

Carrie Hambridge, who stood looking over the shoulder of

another woman, drew a long breath and sighed, whilst her great,

eyes, which had watched the whole scene with puzzled, impatient,

half-contemptuous look, suddenly shone with wondrous light; and as

she turned away to hide her emotion she murmured, "Quixotic?

fantastic? The nature that understood to do that is—is

sublime!"

*

*

*

*

*

The arrangements for the supply of water were, after all, not

very successful, and constant interruptions occurred, so that by the

time the first glint of daylight began to touch the top of the

opposite hill, the old school-house roof had fallen in, and nothing

remained but three grotesque, jagged-looking pieces of wall.

The crowd began to disperse, and except for stray groups which stood

here and there lamenting that the dear old building had not been

insured, very few remained to watch the concluding scenes of this

most distressing accident. A few, however, still remained to

watch the smouldering ruins; and as they alternately doused a

dangerous revival of flame, or discussed the various incidents of

the night, nobody observed a stealthy figure moving here and there

about the premises—now creeping about on hands and feet, and now

making little plunges into the apartments in the rear.

Netty Stone had been seized with a shivering fit, and her

husband had carried her home. But before he had been in

"Squint Hall" many minutes, he remembered something that took him

back to the scene of the fire in a fever of trepidation; and for the

last half-hour he had been searching in the pocket of the coat he

had thrown off earlier in the night, and then over the broken ground

upon which he had thrown it; and at last, after nearly tearing the

garment to pieces in a frenzy of impatience, he had taken to the

singular and secret exploration of the scene in an agony of

excitement: for the ill-fated deed, which was in his pocket when he

threw off his coat to make his reckless plunge into the building,

was gone. He dared not inquire, he dared not even seem to be

seeking; and the growing daylight, welcome enough as an assistant,

was almost cursed as a revealing enemy.

To have lost the deed was infinitely worse than to have left

it in the hands of the money-lenders. It would be found, of

course, and taken to Highfield, or even to the mill; and in either

case would come into the hands of old Bradshaw, and thus spoil

everything. And so, instead of helping his whilom friend, he

would be hated as a bungling busybody. He was compelled now to

hide amongst the ruins of the back vestries. One moment he was

choosing a fresh place and narrowly scanning the locality, and the

next he was spying round the corners, suspiciously watching the men

left in charge of the building. Now he felt an impulse to

drive them all away, even if he had to do it with his fists; and

then he was raging inwardly at the departure of any of the watchers,

whom he immediately suspected of being in possession of the lost

document.

For so cool a person his agitation was pitiable; and when,

upon the company being reduced to four, he ventured out and joined

the remainder, his manner was so strange that they could not answer

his clumsy questions for astonishment at his embarrassment. By

dint of sternest self-command, however, he contrived gradually to

ascertain that nobody there knew anything about the lost article.

Then, dropping into his old, careless, bantering manner, he began to

make roughly witty comments on what he saw around him and the

incidents of the fire, moving off and commencing to wander again

amongst the ruins, and keeping ever a sharp look-out for the thing

he was so anxiously seeking. He could have sat down and cried

over the charred, blackened remains of the old buildings, but every

other emotion was choked back in the presence of one overmastering

desire; and he searched until the "buzzer" called the hands to work.

Six o'clock passed, and he had the building almost to

himself, until the newly-awakened children began to swarm upon the

scene. Dirty, weary, sick at heart, he strode home, where

neither Netty's increasing feverishness nor Lyd's voluminous

reminiscences of the old school could rouse him from his despairing

stupor. He could not eat, he could not sit, he could not even

answer a question coherently. Netty, though very unwell, had

to call downstairs to remind him that he must be at the office at

nine; and though he washed and dressed, and gulped down a cup of

tea, he forgot his wife's request that she might see him before she

went to sleep; forgot even his precise instructions to call at the

doctor's, and stalked along towards the factory, walking like one in

a dream hearing, heeding nothing.

That was the day upon which he was to make his first

appearance on the Manchester Exchange as representative of the firm,

and was to travel to town with his master; but as he entered the

yard the thought of it all made him sick, and the curt, hard tones

of his master's voice, which he heard a moment later in the lobby,

sent a shiver through his mighty frame.

CHAPTER XVII.

THE FALL OF GEORGE STONE.

AS he stood at

the high desk in the outer office blindly making entries in his new

pocket book, George was calling himself hard names, and reminding

himself that at any rate his fears were premature. But at that

instant the bell rang and he was summoned to see his master.

With a supreme effort, the blood leaving his tightly-pressed lips as

he moved, he laid down his pen, raised his big shoulders

apprehensively, and then dropping them with a stern effort, pulled

himself together and strode down the passage. As he entered

the room he realised that his worst fears were justified, and that

the supreme moment had come.

"Shut the door!" But the voice was so harsh and grating

that George would not have recognised it, and as it was he could

neither move nor speak, for his eyes seemed glued to a document

lying on the table—it was the fateful deed! The old master,

when at last George raised his eyes, looked thinner and older all at

once, and his face was drawn and tight, whilst his grey eyes

glittered with steely light. Stern-faced, eye to eye, the two

stood for one terrible moment; but George had his back to the wall,

and the old man was the first to quail. He looked down at his

boots, from them to George's, allowed his eye to travel slowly up

the other's person, glanced at the document on the table, and then

striding across the floor he closed the door with a bang and locked

it, and then, pointing a grim finger at the deed, cried hoarsely, "I

want the truth about that; the whole truth, and nothing but the

truth!"

George's face set hard, and he tried to catch the eye that

would not meet him.

"Out with it! every—bit of it!"

Still no answer.

The master was evidently struggling to be calm, but

resentment, bitter grief, and galling humiliation were too strong

for him; and so, snatching at a heavy ruler, he sprang towards his

man, and shouted: "If thou doesn't speak, I'll break thy big head

with this!"

Grave, grieved, but perfectly quiet, George stood still and

tried hard to catch the eye he was anxious to arrest, but that would

not face him.

"Speak! speak!"—but the blow had fallen. Over George's

left brow was an ugly gash, and a gush of blood was dyeing his hair

and dripping down his cheek. Still, and with a sickly,

apologetic smile, as though he had been the assailant, the younger

man put his handkerchief to his head, and made one more effort to

catch his enraged master's eye. Inflamed rather than softened

by the sight of his work, the master brandished the ruler once more

and hissed, "Don't think thou art doing something.

Thick-headed fool! dost think I cannot see? Out with it, I

tell thee!"

The same sickly smile, and the same silent mopping of the

bleeding brow.

"I'll beggar him! I'll cut him off with a shilling!

I'll bring him to the gutter, and you with him!"

George wavered a moment, opened his lips as though to speak,

looked wistfully at his master from under the corner of the

handkerchief he was holding to his wound, but not a word could he

get out.

The mill-owner watched him keenly amid a tense silence, and

at last he dropped the ruler, turned himself round, and leaning his

elbow on the mantelpiece, stared with changing eyes and relaxing

face at a date rack. Several moments passed, the tick of the

office clock being the only sound, and then, moving uneasily, the

softened but still desperate old man remonstrated, "Thou fool! it's

worth a cool thousand to tell the truth. What's he ever done

for thee? He hates thee, man! he hates thee!"

George's head had dropped a little, and he shook it sadly;

but that was his only response. With face that changed with

every word, and hands and legs that would not be still, the old

fellow peered from under scowling brows at his subordinate, and

then, still leaning heavily on the mantelpiece, and staring at the

wall-paper, he said complainingly—

"I thought thou would have done owt for me."

A heavy, shuddering groan, and George had to grip the table

to hold himself up.

"George, owd lad," and the master, leaning forward, put out

his hand beseechingly, "I know thou likes me! Out with it, for

the sake of thy old master!"

It was an unheard-of position—this gruff, brusque, proud, and

hard-headed old man, pleading to him like a child; and George felt

that he had never known difficulty until that moment. He

stepped back, looked at Bradshaw with mournful, misty eyes, and

heaved a long-drawn sigh. For one struggling moment he

wavered, and then realising that the slightest word would be enough,

he moved back, set his face hard, and looked the refusal he did not

dare to speak.

The employer sprang back as though he had been struck in the

face.

"Wastrel! Scoundrel!" he yelled. "If thou defies

me, I'll make a jail bird of thee! Speak, or I'll send for the

police this minute!"

As he spoke, the baffled, goaded old man snatched at the

bell-rope, and stood waiting for the answer.

"I'd sooner be there nor here, master."