|

[Previous Page]

"The Zeal of Thine House."

-I-

When Greek Meets Greek.

IN the September

following Jimmy Juddy's wedding there was a change of superintendent

ministers in the Duxbury Circuit. It was the middle of October

before the new preacher came to Beckside, his first visit having

been reserved for the "Trust Sermons" Sunday. He had come from

a circuit near London, and had never been in Lancashire before, the

only piece of information retailed about him being that he was a

great chapel-builder.

Such descriptions of the good man as had reached Beckside

were strangely conflicting. Some said he was a thorough

gentleman and a polished speaker, others that he was rather too high

and mighty for Lancashire. In this division of circuit opinion

Beckside realised its responsibility, and prepared itself to give

the preacher a very careful hearing.

The little he had heard of Beckside prepared the preacher for

amusement, and he was a little nonplussed therefore when Jabe and

Long Ben received him in the vestry with impenetrable and icy

stolidity. To counterbalance this, however, he was cheered

when the service was over by Lige, the road-mender, who, in his

Sunday attire, looked a very imposing person, and who met him at the

bottom of the pulpit stairs, and exclaimed, "That's th' best sarmon

we'n had i' this chapil for mony a ye'r." And the minister did

not know that Lige had expressed the same opinion of nearly every

sermon he had heard for many years.

It was Long Ben's turn to take the preacher that day, and

that worthy over the after-dinner pipe imparted to his visitor as a

profound secret the disturbing information that he would have to get

a new steward in his place at Christmas. Well, there was

nothing remarkable in that piece of news, but it was impressed more

than usually upon the "super's" mind by the peculiar action of Ben's

plump, red-cheeked little wife, who happened to overhear the closing

words of Ben's speech. For she shut with a bang the drawer

into which she was putting the tablecloth, shook her cap-strings

quite violently, and then remarked, apparently to the big

brass-clasped Bible on the drawer-top, and in a tone between

amusement and irritation―

"Hay, dear! Owder and softer!"

Now, the "super" was not quite sure in his own mind whether

the remark, which he only imperfectly understood, applied to the

good lady's husband or himself, and was glancing inquiringly from

one to the other of them when Ben invited him to have a walk up to

the Clog Shop.

There, more pipes were smoked, though the minister was not a

disciple of St. Nicotine; and when Sam Speck came in and took Ben

out to hunt up some negligent Sunday School scholars, Jabe informed

the "super" that after twenty-four years' service he had made up

his mind "wilta shalta" [whether or not] to "cum aat at Christmas."

This second resignation made the minister think he smelt a rat, and

so he inquired whether there was anything wrong in the Church.

"Neaw," Jabe replied, "we're reet enough, but Aw mean wot Aw say,"

and he puffed away and looked a very sphinx of stony mystery.

The minister was a little annoyed, and went rather early to the

Sunday School to inspect and address it. When the children were

being dismissed, Nathan, the smith, drew him into the vestry; and

having carefully closed the door, informed him that he had been

seven years in the office of chapel steward, and had only kept on

holding the office to oblige the "supers" who had been there before

the present one, but that now there were so many young ones coming

up he should retire at the end of the year, especially as he wasn't

very good at keeping accounts—and the new minister did not know, of

course, that account-keeping was Nathan's hobby, and that it was his

constant boast that he had never been more than nine-pence wrong in

all these years.

All this was perplexing, not to say irritating, to the minister, and

when he reached his armchair at Ben's, he heaved a little sigh as he

sat down.

"Yo're siking [sighing], mestur," said Mrs. Ben. "Is summut wrung

wi' yo?"

"No, I'm all right; but what are all these good men resigning for?"

"Bless yo'; is that aw? They allis [always] do it when a new mon

comes. Yo' munno tak' ony noatice on 'em; they'd be a fine sight

mooar bothered nor yo' if yo' did."

Then she bustled back into the kitchen, and Ben coming in from the

garden, the minister heard him called "lump-yed," and told that it

would "sarve him reet if he wor turn't aat."

Now the "super" was a shrewd man, and laid these things up in his

mind.

After the evening service the minister went to the Clog Shop for

supper, and was formally introduced to the members of the Club.

When supper was over and the pipes were in full work, Jabe with a

characteristic movement of his short leg, and an assumption of

modesty which did not at all fit him, asked—

"Well, wot dun yo' think of aar chapil, Mestur 'Shuper'?" And

every man in the company tried to imitate Jabe's expression of

grateful modesty in anticipation of the only answer which could

possibly be given.

The new minister seemed most unaccountably embarrassed, and was

about to give an evasive reply when old Lige burst out―

"Yo 'hanna [have not] seen a prattier chapil i' yo'r life, naa, han

yo'?"

The minister smiled rather oddly, and did not quite succeed in

keeping a contemptuous tone out of his voice as he inquired―

"What style do you call it?"

"Style! it's th' A1 style, an' nowt else," cried Lige excitedly,

whilst the others held their pipes at arm's length, listening

intently.

The minister looked wicked, and there was the ghost of a scoff on

his face as he asked—

"Well, but is it classic, or Gothic, or what is it?"

"G-o-t-h-i-c," shouted Lige with lofty indignation. "Neaw, it

isn't; it's gradely owd Lancashire, that's wot it is—wi' yo'r

classics an' yo'r Gothics!"

The minister laughed, and as he had over a mile to walk to catch the

circuit conveyance at the four-road ends, he excused himself and

went away.

But he left behind him a most painful impression. For the first time

in its history the beauty of the Beckside tabernacle had been called

into question, at anyrate by implication. And the offence had been

committed by the superintendent minister, of all persons!

The talk in the Clog Shop parlour was long and very serious; and

though Jabe kept up for some time a show of defence of the

ecclesiastic, it was very half-heartedly done, and he admitted to

Sam Speck when the rest were gone—

"When he talked abaat his Gothics, thaa could 'a knocked me daan wi'

a feather."

Next day all Beckside knew that the minister had scoffed at the

chapel; and the feeling of indignation was quickened when Silas, the

chapel-keeper, made it known that when the minister came to the

week-night service on the following Tuesday he had gone round the

chapel laughing at the high-backed pews, putting his stick into the

cracks in the gable wall, and talking of ventilation until Silas

said—

"Aw welly brast aat on him."

Every time the "super" came to Beckside, he dropped hints about the

chapel which conveyed the impression that he thought it past

redemption.

Then a local preacher told Sam Speck under an inviolable bond of

secrecy that he had heard the "super" call the chapel a "ramshackle old building." But as Sam always made mental reservations

in favour of the Club in his promises of silence, this most

offensive expression was soon common property.

Under these circumstances, when the Annual Trustees' Meeting came to

be held in the following January, feeling ran very high, and the

minister, unconscious of the sentiments of his flock, very speedily

made things worse. The possibility of danger to their tabernacle put

everything else out of the heads of the Church officers, and not a

word was said on the question of resignations. This was a time to "hold on," everybody felt.

When the routine business of the meeting had been got through, the

minister leaned back in his chair and said—

"Well now, brethren, what about this building? It was all right, I

dare say, seventy or eighty years ago; but it won't do now. It is

behind the times. What do you say to a new chapel?"

Nobody spoke, but Long Ben and Nathan began to stare hard at the

fire, and the rest became absorbed in some mysterious matter going

on on the ceiling.

The circuit steward from Duxbury, who had come with the minister,

and was present as auditor of accounts, then took up the tale.

"You know, brethren, this is a box; simply a box; and (with a very

demonstrative sniff) a very musty box too."

Nobody spoke.

A non-resident Trustee, who had also come in the

circuit conveyance, next broke in―

"You know we must move with the times, friends. What was good enough

for our grandfathers is not good enough for us."

Another long silence.

"Come, friends," said the "super " in the chair;

"What do you think?"

No answer.

"Will some one propose that we meet again this day three weeks to

take into consideration the advisability of building a new chapel?"

Another pause.

Presently Jabe rose to his feet, turned slowly round, picked his hat

off the peg above his head, and deliberately limped down the whole

length of the vestry to the door amidst a dead silence.

After another minute's pause Long Ben got up and went through

exactly the same performance as his colleague, staring steadily

before him as he marched out. Then Lige followed, and then Sam

Speck. Only one local Trustee was left; and as the minister sat back

in his chair, watching the scene with amazement, Nathan followed the

rest.

One behind another, like a procession of ducks, the Trustees made

for the Clog Shop, and there held long and excited debate on the

crisis. Everybody agreed that Jabe's mode of treating the matter was

the correct one, and did him credit.

Presently the circuit trap was heard driving past. This seemed a

sort of relief, and crowding as far as possible into the Ingle-nook

and lighting their pipes, the conspirators discussed the situation

in all its bearings, whilst the firelight cast flickering shadows on

their faces.

The chapel was compared to other edifices of the kind in the

neighbourhood, very much to its advantage. Long Ben dwelt with

affectionate pride on the labours of the committee who had cleaned

and decorated it for Jimmy Juddy's wedding, and the "super" was

denounced as a stuck-up cockney, a formalist, and finally by Sam

Speck as a Puseyite—the last epithet being all the more popular

because of its being only faintly understood and altogether

inapplicable.

The minister's talk about "Gothic" was held up to derision, and it

was confidently prophesied that "he wouldn't stop his time aat."

Presently Sam, who was in a state of mental

elation in consequence of his late brilliant feat in nomenclature,

asked from behind clouds of tobacco smoke, which rendered him

invisible far into the chimney nook―

"Well, wot mun we do?"

This gave the conversation a new turn, and brought forth a number of

extraordinary proposals. None of them, however, met with

general approbation, chiefly because of their inadequacy to express

the seriousness of the occasion or the magnitude of the

superintendent's transgression.

At last, however, all criticism was silenced; and perfect, and, in

fact, vociferous unanimity was secured, by the paralysing suggestion

that Jabe should resign all his offices at once.

Yes! That would do. Action so astounding would bring conviction even

to the callous heart of the new "super."

When it was first proposed as a bare possibility, Jabe, though he

thought it not decent to say much, let it be seen that he regarded

the suggestion as a truly heroic one, but when the others began to

discuss it as a really practicable thing he was a little staggered,

and left to himself would probably have been content with something

less drastic.

But he was the leader of the revolt—first in honour and first in

danger. Desperate diseases require desperate remedies; and so,

though he postponed final decision as long as he could, the

infectious confidence of his comrades stimulated him, and he was

soon trying to wear modestly the honour of being the hero of the

hour, and every now and again was dropping mysterious hints as to

the startling effects of their coup on the offending dignitary.

At first it was decided that the awful act should take place on the

"super's" next visit, an idea which Jabe strongly supported; but

Sam Speck and old Lige contented that that was too long to wait, the

moral effect of the deed depending on its following promptly on the

occurrences of the night.

Next day was the Duxbury market, and it was decided that Jabe should

send all his books and other insignia of office, accompanied by a

formal written resignation, by Squire Taylor's market cart in the

early morning.

Then the company dispersed; and Jabe, when the stimulating effects

of friendly presences was withdrawn, found it strangely difficult to

make up his mind about the note. Writing was not the easiest thing

in the world to him at any time, and composition generally took

time, but this evening he was slower than usual. A sudden thought

about the dear old chapel, however, and the "super's" sacrilegious

suggestions about it, brought the necessary resolution, and after

spoiling several sheets of paper he finally produced the following

laconic epistle—

"SIR,—

"I resine all my offices.

"Your brother in Christ,

"JABEZ LONGWORTH."

During the next two or three days the Clog Shop Club sat in almost

perpetual committee. Highly coloured pictures of the stunning

effects of Jabe's resignation on the minister were painted by Sam

Speck and Lige, and anticipations of what that dignitary would do

were canvassed all day long by those who came and went from the

Ingle-nook.

Sam Speck expressed an intense desire to see the minister arrive "wi' his tail between his legs," as he phrased it; and, as the others

shared his curiosity, and, with the exception of Lige, were their

own masters, very little work was done for some days.

But the "super" gave no sign.

The Trustees' Meeting had been held on a Monday, and when Friday

arrived and neither letter nor message had been received, and Jabe's

books were still at Duxbury, everybody became very serious, and Jabe

was evidently labouring under deep anxiety. It was concluded at the

Clog Shop on Saturday night that the "super" would be sending the

books back together with a note by the local preacher who was coming

on the morrow.

When Sam suggested that a note would not do, and that in an affair

of such magnitude nothing but a visit in person would suffice, he

was somewhat seriously reproved by his elders, and reminded of his

disqualification for sober counsels on the score of juvenility.

The preacher arrived on Sunday morning, and was met by the stewards

in the usual way, and when it was clear that he had brought neither

books nor message, Long Ben looked anxiously at Jabe, who wheeled

round in the vestry and limped out into a little back lane, and was

absent from service for the first time for many years.

This was probably as dark a day as the old Clogger had ever spent,

and when the usual Sunday night deliberations in the parlour

produced not a single ray of light, Jabe went to bed to spend a

sleepless night.

The next day he was snappish and bitterly sarcastic. Customers did

their business in the fewest possible words and departed; and the

ingle-nook conspirators endured Jabe's temper very meekly, regarding

it as a special and richly deserved judgment on themselves.

By Wednesday Jabe's crustiness had gone, however, and the Clogger's

aiders and abettors in rebellion noted with consternation that he

had become excessively but sorrowfully amiable. A patient, resigned,

but terribly sad look sat on his face. He sighed heavily every few

minutes, and stuck to his work with a sort of dull desperation.

On Thursday he positively refused to smoke; and on Friday, whilst he

still sat on his bench, it was observed that he was constantly

gazing through the window with a far-away look of melancholy on his

face.

Late on Friday he and Long Ben sat up in deep and secret conclave,

and before daylight next morning Jabe had started to see the "super" at Duxbury.

Now, the minister was a clever man, and prided himself on his

knowledge of human nature. His silence on the question that so

greatly agitated the Beckside Trustees was the silence of policy,

and a smile of triumph crossed his face as Jabe was ushered into his

study on Saturday morning.

"Good morning, Mr. Jabez. Glad to see you! Sit down, sir!"

But Jabe, with a grave, sad face, remained

standing, and overlooking the minister's outstretched hand, and too

deeply troubled to notice his ill-concealed look of victory, he

said―

"Mestur 'Shuper,' Aw've done wrung."

"Wrong, Mr. Jabez? I hope not! In what way?"

"Aw've left a good shop [situation] and a grand Mestur, just because

one of my workmates didn't agree wi' me."

"I don't understand you."

"Dunno yo'? Well th' Lord's let me work for Him till Aw thowt He

couldn't dew ba'at me, but He's shown me as He could. He can dew

better ba'at me nor Aw con dew ba'at Him, a fine sight."

The minister began to have misgivings as to his skill in judging

character.

"Is it about the chapel?" he inquired gently.

"Neaw. It's abaat them books as Aw sent back. Aw've come ta humble

mysel' an' ta ax for t'books back, an' if my Heavenly Father 'ull

forgive me this time aw th' 'supers' i' Methodism shanna drive me

fro' my pooast ageean."

The minister began to feel small.

"Yo' see, Mestur, yo'rs is a changin' life. Yo've seen hundreds o'

chapels i' yo'r time, an' if God spares yo' yo'll see hundreds mooar. But us at Beckside yond' hev' ony wun little Bethil ta think abaat,

an' when yo'n been ta'n to a place as little childer, an' ne'er been

noa wheer else mitch, an' when yo'n getten yo'r fost glimpse o'

Calvary theer, an' aw th' peeps into th' New Jerusalem yo'n iver

hed, why yo' luv' that spot, yo' know, an' theer's sum on us i'

Beckside as luvs ivery stooan there is i' th' building, an' we'd dee

for it if we mud" (must).

"Mr. Jabez," interrupted the minister, gripping the Clogger's hard

hand, whilst his eyes gleamed with unfamiliar tears, "Forgive me,

sir, forgive me! Would to God I loved Him and His cause as you do. I

honour you from my heart."

And the minister asked Jabe to pray with him as a son would ask a

father. And then with wet eyes he went out and told his wife, and

brought her in to see his latest teacher. Then they both asked Jabe

to stay to dinner, and the "super" sent for the circuit conveyance,

and drove Jabe back to Beckside, charging him on the way to keep

silence about his visit.

When they reached the Clog Shop he went and saw Long Ben and Nathan,

and it soon became known that all was well again, the minister

cleverly contriving that it should be understood that Jabe had

conquered him—as indeed he had.

――――♦――――

"The Zeal of Thine House."

-II-

"To Be, or Not to Be."

THE new "super,"

whose attack on the Beckside chapel has been recorded, was too wise

a man to push his plans in the face of such determined opposition,

and consequently abandoned the whole project; and it is only

consistent with the nature of things that, when the minister had

finally given up the idea, those who had so resolutely resisted

began to see something in it.

Jabe had poured scorn on the suggestion that the pews were

not altogether what they ought to be, but somehow they never either

looked or felt quite as cosy afterwards, and he caught himself very

nearly admitting that they were deep and stiff-backed.

Long Ben, who had been so proud of the work of the painting

and decorating committee which "fettled up" the chapel for Jimmy

Juddy's wedding, presently became troubled with inward doubts as to

whether the result justified the effort, and Sam Speck had to be

severely reproved for expressing the treasonable wish that the

chapel didn't look quite so much like the mill engine-house.

In proportion, however, as these doubts took root in their

minds, each became more and more demonstrative in repelling attacks

on the old building, and more and more emphatic in praising its many

excellences. At the same time each man was conscious of all

uneasy suspicion of the loyalty of his friends in the matter.

To have heard the conversation as they stood outside and

watched Silas lock up on Sunday evening, you would have thought that

their admiration of the edifice was higher than ever; for whilst

before the "super's" ill-starred proposal the chapel came in for

occasional commendation or defence, just as circumstances required,

now there scarcely ever passed a Sunday night but, on their way to

the Clog Shop parlour or home, some one of the officials would be

sure to turn round just where he could get a last glimpse of the

building and say―

"Ther' isn't a cumfurtabler little chapil for twenty mile

raand."

All the same, a slow progress of disintegration was going on

in the minds of these authorities, a process of which this excessive

admiration was but too certain a sign. The fact was the

Becksiders had a great respect for the superintendent minister,

whoever he might be, and the present one—the new chapel suggestion

apart—was so popular with them all that unconsciously they had been

deeply impressed by his opinion. The way also in which he had

borne himself when opposed, and the good sense he had displayed in

not resenting opposition, commended him strongly to their judgments,

and one or two of them had gone so far as to secretly regret the

part they had played in his recent defeat.

Not that anyone ever spoke of the matter. The "super"

regarded the question as closed, and apparently the officials did

the same, but they were all nervously afraid of some one suddenly

springing the question upon them again, and thus compelling them to

avow their modified views.

The lesser lights were particularly uncertain about Jabe.

Judged by his utterances, there wasn't the slightest chance of a new

chapel whilst he lived, but they were not quite sure, some of them,

that his loud protestations were not a trifle overdone, and they

were strengthened in their suspicions by the Clogger's very apparent

admiration of the "super."

These feelings were deepened by the fact that Jabe announced

to them, one evening, that the "super" had been an architect before

he entered the ministry, and had built at least a score places of

worship in the course of his public life. Evidently Jabe and

the preacher had been talking of chapel-building.

One Sunday night a stray remark by that rash young man, Dr.

Walmsley, gave Long Ben a long-looked-for opportunity, and five men

stopped in the middle of long pulls at their pipes, and held their

breaths, as Ben alluded for the first time openly to the forbidden

subject in the presence of the minister.

But the "super" knew his men by this time, and did not rise

to the bait, and every listening smoker breathed a sigh of relief.

When he had gone, and the company had settled down to the

regular Sunday evening topic, and Lige had finished a

highly-flattering criticism of the sermon, Jabe once more brought

all talk to a standstill. For, tilting back in his chair and

balancing it on its back legs, in sublime indifference to the

subject under discussion, he said, apparently to a half-consumed ham

hanging on the joist near the door―

"If ever we dew have a new chapil i' Beckside, yon's

th' mon as Aw should loike ta build it."

There was a long silence. Not a word was said in reply,

and when the conversation was resumed it was on the old topic of the

evening's sermon. All the same every man went away that night

with the feeling that the new chapel was now at anyrate a

possibility.

Next week was the Circuit Quarterly Meeting, and as usual,

Jabe, Long Ben, Nathan, and Sam attended as the representatives of

Beckside. Just before the meeting closed, the "super," with a

palpably gratified air, announced that a very interesting

communication was about to be made to the meeting, and called upon

Brother Ramsden, of Clough End.

This gentleman, who was to Clough End what Jabe was to

Beckside, and who had been, for him, unusually quiet all evening,

with a look of immense importance, rose at the call of the chairman,

and after justifying his reputation for jocularity by a number of

more or less appropriate witticisms, formally asked the permission

of the meeting to build a new chapel at Clough End.

"An' Aw whop (hope)," he concluded, "as it 'ull stir aar

Beckside friends up ta get aat o' yond' owd barn o' theirs."

All eyes were at once turned towards the Clogger and his

friends, but Jabe closed his mouth very tightly, pursed his lips,

and looked across the room into vacancy; and the others feeling, as

Sam Speck afterwards admitted, "as if cowd wayter wur runnin' daan

my back," shot glances of quick inquiry at Jabe, and imitated his

look of stern gravity, as if in rebuke of the frivolity of the

speech to which they had just listened.

The Clough Enders, who had to pass through Beckside on their

way home, got into the coach with the Clogger and his friends, and

were, of course, full of their new scheme. Soon they drew Long

Ben—as a practical man—into the discussion of a draft plan of the

proposed structure which they had brought with them.

This was too much for Sam and Nathan, whose curiosity proved

stronger than their dignity, but Jabe with folded arms sat bolt

upright in the far corner of the vehicle, not deigning to notice the

plans or show the slightest interest in the conversation.

There was always a full attendance round the Clog Shop fire

on the evening of the Quarterly Meeting, and on this occasion every

possible seat was occupied. Jimmy Juddy, Sniggy Parkin, the

Doctor, and even retiring Ned Royle, being there to hear the news.

The air with which the Clogger walked through the shop into

the parlour to change his Sunday coat announced more plainly than

words that there was something unusual to tell, and the company

present was preparing itself for a feast of succulent intelligence

and discussion when Sam Speck, who had stayed behind to say "Good

neet" to the Clough Enders, suddenly burst into the shop and spoilt

all by blurting out in excited eagerness―

"Chaps! th' Clough Enders is goin' to hev' a new chapil."

Instead of the sensation he expected Sam received a decided

snub. The news he brought was unwelcome, but his manner of

serving it up was inexcusable. Matters of this kind were not

to be flung at them as if they were mere items of ordinary gossip,

and so instead of looking at each other in amazement, as Sam had

expected, they carefully avoided catching each other's eyes, and sat

looking into the fire with a decidedly non-commital look on their

faces.

At this moment Jabe reappeared, and everybody felt that now

the subject would receive becoming treatment. But first the

Clogger held a consultation with his apprentice on some matter of

business, and the company was divided between impatience to hear his

story and admiration of his artistic sang froid.

Then he sauntered idly to his seat by the fire, and commenced

to charge his pipe, attempting as he did so to start a discussion on

the probable age of the vehicle in which he had just travelled.

But nobody assisted him, though all admired his magnificent

self-possession.

The pipe duly lighted, he at length commenced his regular

description of the events of the day. But he was most

aggravatingly deliberate. Not a detail was omitted, though he

must have seen with what impatience his needless elaboration was

received.

Then he diverged into a discussion with Sam Speck as to

whether the average contribution per member from Brogden had been

1s. 4½d. or 1s. 5½d., and when the latter figure was eventually

accepted he branched off, for the special edification of Sniggy,

into an exhaustive description of the financial system of averages

which obtained in the circuit.

The company listened with growing but carefully-concealed

impatience to this digression, marvelling uncharitably at Sniggy's

lack of comprehension, and all looked relieved and hopeful when,

with a long-drawn "Well," Jabe prepared to resume the main current

of his story.

But just at that moment his pipe went out, and every man in

the company watched with painful interest as, after trying three

matches, he finally discovered that the fuel was exhausted, and

proceeded with exasperating deliberateness to refill and relight it.

As a rule the members of the Club were proud of the

prodigious memory of their chief, but for once they could have

wished it had been a little less tenacious and precise, for the

speeches of the officials seemed long and tedious affairs indeed as

Jabe reported them.

At last, however, the statement for which every one was

waiting with a burning impatience could no longer be withheld, and

so propping himself against the shoulder of the Ingle-nook, and

drawing it out as if it were a hardship to have to give such an

utterly unimportant detail, he said―

"An' then Hallelujah Tommy said summat abaat a new chapil at

Clough End. But Awne'er tak's mitch heed ta wot that gaumless

says."

But nobody was deceived by this painful pretence of

indifference, and in a moment or two Sam set every tongue wagging,

and got rid himself of much pent-up excitement by crying―

"Ay! an' it's ta hev' churchified windows, an' a pinnicle."

Soon the discussion waxed hot, the interest being intensified

by the fact that though they were only discussing the Clough End

chapel, a far more important question was felt to be in the

background.

By long-established custom the Club sat an hour longer than

usual on Quarterly Meeting nights; but though it was late when they

began to separate, Long Ben, often one of the first to leave,

lingered behind, and when he and the Clogger were alone and had sat

for some minutes silently looking at the dying chip embers in the

fire, he turned to Jabe and said, with an anxious sigh,―

"Aw'm feart wee'st ha' ta give in, lad."

And the sigh which accompanied the Clogger's reluctant "Ay"

was longer drawn and deeper than Ben's.

It was customary in the week of the Quarterly Meeting to hold

a united fellowship meeting instead of the ordinary classes, and at

such gatherings Silas, the chapel-keeper, was generally a prominent

figure. But the night after the events just described Silas

was dumb, and neither long pauses nor nods, nor even nudges, had any

effect.

"Th' dumb divil's getten howd of sum folk," said Jabe

significantly, as he, Ben, and Silas were passing along the side of

the chapel homewards. But Silas only held his sharp, sallow

face a little higher, and gazed sideways at the rising moon.

As they were turning the corner to the front of the chapel,

however, Jabe pulled up, and whipping round at Silas in the rear, he

demanded sternly―

"Wot's up wi' thee?"

"Up!" shouted Silas, a look of fierce aggressiveness

springing into his face; "Up!" he repeated, and seizing his

companions by the arms he pulled them back into the little graveyard

and cried―

"We're goin' t' have a new chapil, Aw ye'r."

"Well! wot if we are?" demanded Jabe.

"Well, if there's a new chapil ther'll be a—a," and Silas's

voice became tremulant, "there'll be a new chapil-keeper, that's

aw."

The two leaders looked Silas over slowly from head to foot

with a mournfully curious look.

"Dunna meyther thysel', lad," said Ben soothingly, as he put

his hand gently on Silas' shoulder.

"Meyther mysel'!" cried the chapel-keeper almost in a scream,

and springing away from Ben's touch, "Aw've ta'n cur of this chapil

for welly forty ye'r, an' Aw'm th' poorest mon among yo', but Aw've

ne'er ta'n a brass fardin o' wages aw th' toime. Wot have Aw

done that fur? Wot have Aw lived i' th' little damp

chapil-haase fur aw this toime?"

The leaders moved uncomfortably, and had a guilty,

self-reproachful look.

"Dunna, Silas! dunna, lad!" said Ben, in a mournful, coaxing

tone.

"Dunna!" shouted the agitated apparitor, and, pointing to a

grave close under the chapel wall, he continued in high, protesting

tones―

"Sithee, my owd mother lies theer, an' aar Kitty, an' little

Laban, an' yond"'—pointing across towards the boundary wall—"yond'

lies my own bonny Grace an' her little un. An'," he continued,

wheeling round, "here's thy fayther, Jabe, as poo'ed mi aat o' th'

Beck when Aw were draandin', and theer's owd Juddy, as poo'ed me aat

o' the horrible pit an' the miry clay. Ay," he went on,

standing up and wildly waving his hands around him, "they're aw

here. An' Aw live wi' 'em, an' they live wi' me. An'

when Aw feels looansome an' daan i' th' maath, Aw comes aat here an'

sits me daan an' sings aw by mysel'—

|

'Come, let us jine our friends above

That hev obtained the prize.' |

An' Aw'st ne'er leave 'em. Aw'st ne'er leave 'em till

Aw goa an' see 'em gradely."

And, out of breath with his exertion and excitement, the poor

chapel-keeper sank back and propped himself against a gravestone.

By this time Ben was in tears, and Jabe, trying ineffectually

to swallow something, looked first at one grave Silas had pointed

out, and then at another, with a miserable convicted look on his

face and certain strange twitches about his mouth.

"We met poo' it daan, an' rebuild it, thaa knaws," suggested

Ben hesitatingly, from behind his pocket-handkerchief.

"Ay! for sure," chimed in Jabe.

"Poo' it daan!" cried Silas, in new agitation; "that's woss

nor aw. Sithee, Jabe, Aw'll show thee summat as thaws ne'er

seen afoor. Aw nobbut fun it aat mysel' t'other day."

And, taking Jabe by the elbow, he led him forward to where,

close to the ground, in a dark corner all green and mouldy, was a

stone in the wall. Then he plucked a handful of grass and

briskly rubbed the face of the stone, and then, striking a match and

holding it near the stone, he made Jabe kneel down and examine it,

pointing as he did so to certain indistinct marks on the face of the

stone.

"Con ta read it?" he queried eagerly, but Jabe did not

answer; but, kneeling on the grass, he kept looking carefully at the

scratches until they slowly formed themselves into a scrawling

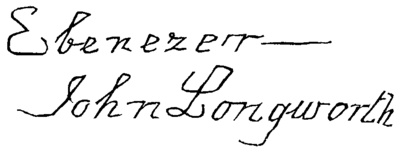

legend, evidently made by the point of some sharp instrument―

Jabe continued to scrutinise the inscription, which was very

faint, and had evidently been hastily done, until Ben came and knelt

at his side and assisted in the work of decipherment.

"It's reet," said Silas, when at length they rose to their

feet. "It's just loike his writing i' the burrying-book."

The three men stood looking down at the stone, and presently

Silas resumed―

"Naa, that's it. Thy fayther 'ud nobbut be a lad when

he put that in—just convarted, Aw reacon, an' thaa talks o' poo'in

it daan, does to?"

"An'"—throwing open a window as he spoke―"yon's th' owd

poopit as Adam Clarke preached in, an' Sammy Bradburn. Aw

reacon thaa'll poo' that daan. An' yond's th' penitent-form

[communion-rail], wheer thee an' me, an' sum 'at's up aboon, fan

peace i' th' Great Revival. Thaa'll be poo'in' that daan,

wilta? Well, yo' con dew as you'n a mind, but t'owd Book says,

'Thy servants shall take pleasure in her stones and favour the dust

thereof.' An' Aw dew! Aw dew!"

And, leaning his dark face against the old wall caressingly,

as a child to its parent, he concluded―

"Aw love every stoaan in it, ay, an' th' varry dust we're

treidin' on."

Deeply moved by what they had heard, the two leaders somewhat

hastily bade Silas "Good neet," and as they were going down the broo

"each turned round and took a long, lingering look at the edifice

they had just been discussing, sighing heavily the while; and that

same week, without any spoken word having been used, but by such

processes as were perfectly understood amongst them, it penetrated

into the minds of the Beckside Methodists that whatever else was

done there would be no new chapel.

――――♦――――

"The Zeal of Thine House."

-III-

Of His Necessity.

LONG

BEN, Jabe, and the

"super," with their heads close together, were bending over certain

hasty lead-pencil drawings, engrossed in earnest conversation.

"Howd! howd," cried the Clogger, interrupting the minister, "Yo'

munna talk like that. Th' on'y chance o' gerrin' it through 'ull

be fur t' keep them names aat. If yo' talken abaat Roman ex's

[esques] and Gothics to aar chaps yo'll ruin th' job, an' wee'st ha'

wark enew as it is."

"Aw think we'd better let th' owd winders a' be," chimed in

Ben; "bud yo' con mak' a fancy frunt if yo'n a moind. On'y

dooan't caw it by ony fancy names."

"Very good," said the "super," with a sigh of disappointment.

"I'll do the best I can, and you must pave the way for me."

"An' they' mun be noa steeples, nur pinnacles, nur hangels'

yeds, nur Chineese wark abaat it," persisted Jabe. And, as the

"super" nodded slowly, Ben gently added, "An' we mun ha' noa

thrutchin, an' wilta-shalta wark. If they winna they winna,

and we ar'na' fur t' hurt even 'one o' these little ones.'"

And the tremolo cadence of anxiety in the carpenter's voice disarmed

a momentary irritation in the minister's mind.

This conversation took place on a Sunday afternoon. The

two officials having made up their minds that, though the old

building must be preserved, some heed must be paid to the wishes of

those who pressed for improvement, had requested an interview with

their ecclesiastical chief, of which the words recorded above were

the closing parts.

They had explained to him the exact situation, and after a

stealthy visit to the chapel ostensibly to address the scholars, but

really to survey the premises, the "super" had hastily sketched a

plan which had the tentative support of his subordinates, the

understanding being that he was to prepare detailed drawings and

submit the whole scheme to a meeting of trustees, Jabe and Ben

undertaking to prepare the way as best they could.

Now, since the memorable scene in the chapel-yard, Silas,

only an occasional visitor before, had taken to attending regularly

at the Clog Shop, evidently apprehensive lest, in his absence, some

conspiracy might be hatching for the injury of his beloved chapel.

And as Sam Speck had recently taken to openly advocating a new

building, thereby manifesting a dangerous independence of judgment,

the Clog Shop confabulations often developed into stand-up forensic

fights between the two, the other members of the party only making

occasional contributions to the debates.

On the Sunday night in question, the discussion on the

"super's" sermon lasted rather longer than usual, a passing

reference of his to Socinianism having produced itching curiosity on

the part of the irresponsibles, and evasion and impenetrable mystery

on the part of those who were generally recognised as authorities.

Presently, however, Long Ben, who was generally supposed to

dislike the subject of the new chapel as provocative of strong words

and stronger emotions, actually introduced the question himself.

Sam Speck, astonished at this manoeuvre, and hoping, though

with misgivings, that he had made a convert, at once launched out in

commendation of the enterprise and pluck of the Clough Enders, and

the grandeur of their new building, at least as far as its plans

were concerned.

Of course Silas, the chapel-keeper, at once accepted the

challenge, and was soon giving Sam a Roland for his Oliver.

To the surprise of everybody, Long Ben and Jabe immediately

took sides with Silas, and out-Heroded Herod in their denunciation

of any idea of erecting a new sanctuary.

Sam was dumbfounded, and Silas, whose only reliable

supporters hitherto had been Lige and Jethro, rejoiced over the new

converts with many a quiet chuckle. Sam looked crestfallen,

and Jonas Tatlock and Nathan the smith, his chief supporters,

frowned and looked at each other in sympathetic resentment.

Presently Long Ben, contemplating with peculiar steadiness

the candle on the table, and with the most guileless expression of

countenance he could command, remarked―

"Th' Independents hez a gradely nice chapil at th' Hawpenny

Gate."

"Ay," added Jabe reflectively, as if the idea were perfectly

new to him, "specially sin' it wur rebuilt."

As nobody followed this subtle lead, Ben resumed―

"Le'ss see; when wur it fettlet up?"

"Nine ye'r sin', cum th' frost of February," said Lige, who

prided himself on chronology.

Nobody, however, seemed to take any particular interest in

the matter, for the Halfpenny Gate was four miles away, and the

chapel only an Independent one, and Jethro was just beginning to hum

a tune preparatory to

starting a hymn, singing being not an uncommon practice when topics

of interest were scarce, when Jabe observed―

"It wur th' poorest chapil i' th' countryside afoor it wur

enlarged."

"Soa it wur, lad," replied Ben, apparently only just

remembering the fact, and then, after another pause, he went on―

"Aw'm nor i' favour of new patches upo' owd clogs as a

general thing, but it's aw reet i' sum cases, and saves boath

brass an' fawin' aat."

Now, Sam Speck, indignant at the unusually emphatic manner in

which the recognised heads had opposed his new building scheme, was

giving but a sulky and indifferent ear to the conversation, but

happening to lift his head at this moment, he caught a gleam in

Ben's eye which came as a revelation to him, and catching at the

suggestion hidden under Ben's last remark, he cried out suddenly―

"That's it! By th' mon, that's it! Chaps, we'll

enlarge th' owd 'un!"

And those crafty schemers, Jabe and Ben, affected to consider

this as a totally new idea. They tilted back their chairs and

studied the joists intently, and then slowly shook their heads, as

if to say that they thought very little of the scheme, and, at

anyrate, saw serious difficulties.

And their attitude had exactly the effect they expected.

Gentle opposition only wedded Sam the faster to his idea, and made

him the more fruitful of arguments in favour of it.

Silas also—a much more serious difficulty than Sam—was

deceived by the manoeuvre, and, as the only person present who knew

the exact measurements, supplied details which strongly confirmed

Sam's proposal, and very soon found himself getting angry at the

inconvinceableness of the arch-conspirators.

At length, after long argument, Jabe, in dubious, hesitant

tones, admitted that "Ther' met be summat in it," and with that the

assembly dissolved, Sam full of the double glory of invention and

conquest in argument, and the two stewards demurely content.

The following Friday the "super" held the Trustees' Meeting

and expounded his scheme. The old building was to be left

intact, except that the front was to be taken out and brought

forward, thus giving about forty extra sittings in the chapel.

The vestry at the back was to be pulled down and a schoolroom

erected in its place. The old woodwork of the chapel was to be

removed into the school, but the pulpit and communion-rail were to

be left intact; and when, after describing his scheme in outline,

the "super" unfolded a number of beautifully drawn and coloured

plans ("as good as picters," according to Sam Speck), and invited

examination, seven self-consciously important men drew up to the

table and proceeded to scrutinise the designs with as much of the

air of experts as they could manage to put on. They hung long

and lovingly over the "picters," and when the "super" returned that

night to Duxbury he had full authority to proceed, and left behind

him a body of men who spent the rest of the evening marvelling at

the extent and versatility of his gifts.

A day or two later completed plans were sent, and lay on the

Clog Shop counter for public inspection, and for the next fortnight

Beckside Methodism sat in almost perpetual committee over these

latest examples of the minister's skill. By the end of that

time, there was scarcely a person concerned even remotely in the

matter who had not given judgment in favour of the scheme.

There was one exception, however, and though it would ordinarily

have been regarded as of little moment, yet after what had passed in

the graveyard, Jabe and Ben were honestly distressed at the ominous

absence of Silas.

The "super" was coming over to a public meeting for the

purpose of raising funds on the Friday, and Wednesday night had

arrived, but the chapel-keeper had given no sign. Glowing

descriptions of the new designs had been given him by those who knew

nothing of what had occurred between him and the leaders.

Twice, after putting the plans in a conspicuous place on the

counter, Jabe had sent for Silas on some invented business in order

to draw him into a criticism of the scheme, but without success, and

to have directly broached the question would have been to court

failure.

Thursday, the day before the great meeting, arrived, and no

satisfactory evidence was forthcoming as to Silas's attitude.

In the quietest part of the afternoon of that day, however, whilst

Jabe was busy upon a new pair of clogs, Silas suddenly presented

himself. He wanted a clog-iron on, and he wanted it on in a

great hurry, and, catching sight out of the corner of his eye of the

plans, he turned his face toward the opposite wall, and became

intensely interested in a quite venerable advertisement of patent

blacking.

Jabe took most extraordinary pains with that clog-iron, and

succeeded in making the operation last quite a long time. In

the meantime, Silas, affecting the most restless impatience,

fidgeted every moment about the shortness of time.

Presently Jabe began dropping hints, and putting leading

questions, but Silas would not be caught, and when the iron had been

replaced, and another one that Jabe discovered to be "loosening" had

been made secure, and the repairing process could no longer be

prolonged, he handed back the clog to its owner with a petulant

jerk.

Silas, on his side, now that the opportunity of departure was

provided, seemed suddenly to have been seized with a fit of

lingering, and manifested a reluctance to depart strangely

inconsistent with his former feverish impatience.

At this moment a new idea occurred to Jabe, and, catching

sight of a pair of clogs, evidently waiting to be taken home, he

cried out―

"Hay, dear! that lump-yed of a Isaac's goan to his tay ba'at

takkin' Jethro's clugs wi' him. Sit thi daan, Silas, an' moind

th' shop woll Aw nip daan an' tak' em. Th' owd lad conna cum

aat till he gets 'em."

Silas, forgetting his previous haste, complied with

ill-disguised alacrity, and almost before Jabe had closed the

shop-door, he was bending eagerly over the erstwhile invisible

plans. He had a good long look at them, for Jabe was an

unconscionable time away, and when he did return he found the plans

apparently as he had left them, and Silas still engrossed in the

subject of patent blacking.

Jabe attempted to draw the chapel-keeper into conversation

again, but without success. Silas remembered his forgotten

haste, and departed with demonstrations of impatience, leaving the

Clogger wrestling with a sense of defeat.

In the evening Silas joined the company round the fire, and

appeared very attentive when anything referring to the renovation

scheme was introduced; and, when he had departed, Ben nodded his

head sagaciously across the fireplace at his friend, and re-marked―

"He's cumin' raand nicely, tha sees."

The following night the great meeting was to be held.

The "super" was to take the chair, and for some days consultations

had been held, challenges given, and thinly-veiled exhortations

addressed by the Becksiders one to another with a view to promoting

liberality.

It was getting dark on the Friday evening as the "super"

reached the top of the hill going down to the village, and his

reverence was just tightening rein to steady his steed down the

rough incline when a man came out from behind a gatepost and cried,

looking cautiously round as he did so, "Whey!"

It was Long Ben, and as he came close to the trap the "super"

noticed a look of apprehensive caution on his face. After the

heartiest of greetings, and another anxious glance towards the

village, he said, dropping his voice almost to a whisper―

"He's bin agate on me ageean; he winna le' me gie nowt."

"Who won't?" asked the "super."

"Whey, him!" jerking his thumb in the direction of the Clog

Shop. "He says Aw'm nobbut fur t' gie five paand!" And

Ben's long face lengthened considerably with an injured, resentful

expression.

"Well, can you afford more, Mr. Barber?" asked the "super,"

who knew enough to justify the question.

"Affooard! Wot's affooarding to dew wi' it?" cried Ben,

now fairly roused. "This is fur th' Lord's haase, isn't it?

Aw mun affooard, an' Aw will, fur oather him or yo'!"

"Well, but, with your family, Mr. Barber"―

"Family! that's just it. Dew yo' think my childer 'ud

loike fur t' goa theer, an' gie nowt towart th' fettlin' on it?

Neaw, neaw, mestur, we'est dew it if we 'an ta clem [starve] fur

it!"

"And does Mr. Jabez want to stop you?"

"Stop us? Ay, does he. He says as if Aw give a

hawpenny mooar nur five paand he'll stop th' job."

"Well, what do you want me to do?"

"Aw've getten a bit of a plan fur chettin' him, if yo'll help

me."

"Well, what is it?"

"When yo' begin ta read aat th' subscriptions yo' mun read

aat ' Ben Barber, five paand,' an' then a bit efther yo' can say, 'A

Friend, twenty paand,' dun yo' see, an' theer's th' brass," and Ben

handed the minister five five-pound notes.

A few minutes later the "super" and Ben entered the Clog Shop in

company, and Jabe seeing them together, glared fiercely at Ben and

demanded―

"Weer'st bin?"

But Ben merely sauntered to his seat with his hands in his pockets,

and began humming a tune.

"Tum, tum, tum," cried Jabe, mocking the carpenter's music, and

evidently in the worst of humours; "tha's summat ta 'turn, turn'

abaat, tha has." And eyeing him with a look of mingled suspicion and

disgust, he suddenly demanded―

"Hast browt that writin' papper?"

"Hey, neaw!" cried Ben in sudden remembrance; "Aw'd cleean forgetten

it," and he hurried off homeward.

Jabe watched him disappear with distrustful, uneasy looks, and then,

turning with a heavy sigh to the minister, he cried despairingly―

"Aw'st ne'er mak' nowt on him, Aw con see. Aw've bin trying forty

ye'r, an' Aw'm furder off nor ivver!" and then on sudden

recollection he changed his tone and said, "But Aw want ta hev a

word wi' yo', Mestur Shuper, afoor we goa."

"Proceed, Mr. Steward."

"Naa, when yo' starten a talkin' abaat brassta-neet, yon sawft ninny

'ull be up on his feet an' givin' away his childer's meit afoor we

know wheer we are. Well, Aw'm gooin' fur t' stop him. As soon as yo'n oppened aat, yo mun read aat, 'Jabez Longworth, twenty-five

paand,' an' then, afoor he has time fur t' speik, yo' mun say, 'Ben

Barber, twenty-five paand.' An' if yon mon gets up on his lung legs

yo' mun stop him, an' if he gets up twenty toimes yo' mun stop

him,—and theer's th' brass." And Jabe handed fifty pounds to the

minister in gold and notes.

The "super," touched, amused, and a little embarrassed by the

conflicting confidences of these two friends, was about to reply,

when Ben returned with the writing materials, and all three

adjourned to the chapel.

A goodly company had assembled, and, after a formal opening, the

minister proceeded in a clear and forcible speech to explain the

scheme and solicit subscriptions.

"I have received one or two subscriptions already," he said, "which

I will read:―

"Mr. Benjamin Barber, five pounds.

"A Friend, twenty pounds."

There was an exclamation of smothered wrath from Jabe, but the

minister proceeded:―

"Mr. Jabez Longworth, twenty-five pounds.

"Mr. Benjamin Barber, twenty-five."

The meeting looked mystified. Two subscriptions in one name sounded

very odd. Long Ben sat in his side pew with his eyes closed, and his

face void of all expression, and Jabe, after emitting from

tightly-pursed lips certain indescribable sounds, suddenly rose to

his feet, and glaring over the heads of the people, across the whole

length of the chapel, exclaimed, shaking a podgy finger at Ben—

"Thaa thinks thaws dun it this toime, dust na? Bud Aw'll be straight

wi' thee yet, tha long lump-yed, thaa."

The minister was shocked at this very unparliamentary language, and

was about to intervene when his attention was diverted by a

scuffling sound in one of the middle pews, where Sam Speck and

Nathan seemed to be having some trouble with Silas the

chapel-keeper, who was tightly jammed between them.

More subscriptions began to come in. Dr. Walmsley, in his own and

his "dear wife's" name, offered a thankoffering for a good mother,

followed by smaller gifts from the ladies themselves. Then came

Jonas Tatlock and Johnty Harrop, followed by poor Phebe Green from

the mangle-house, who wanted "to thank God for being a friend to the

widow and sending her some more friends."

"Ten paand, Mestur Shuper," shouted Nathan the smith, still

embarrassed by that mysterious conflict in the middle pew.

"An' me ten," chimed in Sam Speck, apparently out of breath from the

same cause.

Then a sudden hush fell on the assembly as Sniggy Parkin stood up,

in evident emotion.

"Aw—aw hevn't getten gradely straight yet, friends," he stammered, "bud if yo'll trust me twelve months Aw'll gee two paand ten fur th'

schoo'-missis, God bless her" — (loud Amens)—"an' two paand ten fur

this blessed owd place wheer Jesus washed my sins away."

Then came smaller contributions from others of the reformed

Brick-crofters, each accompanied by some rudely-tender reference to

"th' schoo'-missis."

A pause followed, and Lige, the road-mender, started off singing, "Ther'll be na mooar sorra theer."

And when that was got through, Job Sharples, the niggardly

pig-dealer, rose. There was breathless silence as he opened his pew

door and walked up to the communion-rail, behind which the minister

sat, and put down on the table a coin.

Then he smiled patronisingly on the minister, and walked back to his

seat. Several persons rose in their seats and leaned over to see

what the coin was. "A sovereign," passed in whispers round the

chapel, and expressive looks were exchanged.

As the whispers reached the back pew Jabe rose from his seat, paused

to draw himself to his very fullest height, and then kicking

savagely at the disobedient pew door, he limped down the whole

length of the chapel, took the coin from the table, and, stepping

with a haughty mien to Job's seat, he placed the coin on the narrow

book-rest with a loud click, saying as he did so, in tones of

inexpressible scorn and irony, "Thaa conna affooard it, Job," and

then, with his nose very much in the air, he limped back to his pew.

A second time, at a moment of intense interest, that mysterious

noise came from Sam Speck's pew, and taking advantage of the

momentary distraction, Job snatched his cap from one of the pegs

against the wall and hurried out.

A few more subscriptions were now announced, including quite

reckless sums from Jethro and Lige, and once more that unruly

disturbance in Sam Speck's neighbourhood broke out. A sharp sound,

like the rending of cloth, was heard, and Silas, the chapel-keeper,

with a flapping rent in one of his coat-sleeves, came struggling out

of the pew, having evidently escaped with difficulty from the

restraining hands of Sam and Nathan.

With his long, thin hair waving about, and excitement and triumph in

his look, he rushed up to the table, and dragging out of his pocket a

large tobacco-box, he opened the lid and emptied the contents before

the minister. It was a strange collection. There were several dim

and dirty threepenny and fourpenny pieces, a number of green-mouldy

coppers, two crowns, a few other odd silver coins, and three little

greasy packets containing a half-sovereign each.

"They say Aw munna give nowt 'cause Aw'm sa poor," he cried, in his

wild way. "They say as they'll send it back if Aw dew. Did th' Lord

stop th' poor widow fro' givin' 'cause hoo wur poor? Did He send her

mite back? Neaw! An' He winna send mine back, if they dew. It wur aw

as hoo had, and He took it; an' it's aw as Aw have, an' He'll tak'

mine. An' Aw daar ony on yo' to stop me." And poor Silas sank

sobbing upon the communion cushion.

"Friends," said the minister, with wet eyes and shaking voice,

"Silas, like the widow, has given more than we all, for he has given

of his necessity."

――――♦――――

"The Zeal of Thine House."

-IV-

Raising the Wind.

THE Clogger sat

in a high-backed arm chair, very close to the parlour fire. He

had a huge "comforter" round his neck, the ends of which passed up

over his ears and met in a knot at the top of his head. One

side of his face was swollen. Though the weather was cold, he

was without a coat, for Beckside gentlemen seldom wore their coats

indoors; but his shoulders were covered by a heavy shawl. He

had on his knee a jug containing ale-posseta very popular local cure

for colds—and near him, on the oven top, another jug containing "cumfrey

tay."

He held his head a little on one side in a pensive manner,

and had a pathetic, self-pitying expression on his face. He

had got wet through two or three times lately whilst out begging for

the chapel, and this was the result. He had now had several

days of invalidism, which had tried his temper very severely, and at

last had reduced him to pensive and sorrowful resignation.

"Aw've towd thi mony a toime as Aw shouldn't be a lung

liver," he said, in melancholy, whining tones, to Aunt Judy, who was

nursing him. "An' tha sees Aw'm reet. Aw'st dee abaat th'

same age as my muther did."

"Dee? Ger aat wi' thi, tha owd mollycoddle. Yo'

felleys is so feast if owt ails yo'."

"Judy," he replied, shaking his head with profound solemnity,

"yo'r Jabe's dun." And then, after another pause and a sob,

which he did not even try to conceal, "Aw'st ne'er see th' chapil

oppened aat."

Judy was in difficulties. She did not in the least

share the patient's fears, but she knew that to refuse to believe in

them would only make things worse. So she tried to get up an

argument with him on the comparative virtues of ale-posset and "cumfrey

tay," and roundly declared, in the hope of arousing a spark of the

old combativeness, that the preference of men-folk for ale-posset

was a suspicious circumstance to her.

But even this did not succeed, and Jabe was commencing to

give some directions as to the disposal of his worldly possessions,

when Judy had a sudden inspiration, and broke in—

"Hast yerd wot Sue Johnty's bin propoasin'?"

"Neaw, wench," replied the Clogger, but with just the

faintest gleam of curiosity in his eye. "Aw've noa interest i'

warldly things naa."

"Hoo says hoo can see a hunderd paand in it, at ony rate,"

said Judy, stealing a sly look at her brother's face, and knowing

that if anything could rouse him it would be the chance of hearing

of means to raise money for the chapel renovation scheme.

"Well, hoo's a loikely wench is Susy," Jabe replied.

"Wot's hoo been sayin'?"

"Hoo wants us to have a buzaar." And Judy gave a sort

of anticipatory wince, and shot a glance of quick apprehension at

the Clogger, as she dropped out the last word.

"Wot?" shouted Jabe, jumping to his feet, and upsetting the

jug of ale-posset as he did so. And for the next five minutes

poor Judy had poured upon her a torrent of abuse and reproach.

The attack would doubtless have lasted longer than it did but

for the fact that Jabe's excitement burst a huge gumboil and

effectually closed his mouth for the time, and the doctor, coming in

a little later, found him faint and exhausted, but still "breathing

out threatenings."

For the next three days Jabe sat in semi-state in his

parlour, passing through the various stages of convalescence, and

telling over and over again the story of Sue Johnty's wicked and

worldly proposal, and though many disagreed with him, and some had

even given a conditional adhesion to Mrs. Johnty's scheme, nobody

dared to say so in the Clogger's presence.

Jabe had never seen a bazaar, but he regarded them as the

last sign of worldliness and pride in a church, and declared again

and again during those days of convalescence—

"Aw'd sooner see th' bums [bailiffs] i' th' chapel fur debt

nur pay it off wi' brass fro' Vanity Fair."

This episode seemed also to increase his animosity towards

the opposite sex.

"Women an' trubbel cam' into th' warld together, an' they'n

bin together ivver sin'; bud Aw'll watch 'em at this."

But poor Jabe was only human, and turned pale with a sense of

approaching discomfiture as on the first day after he resumed work

he lifted his head and saw the schoolmistress (now Mrs. Dr. Walmsley),

Nancy of the Fold farm, and the irresistible Mrs. Johnty Harrop

approaching the shop.

It was a long tussle in the parlour that afternoon, and when

the ladies retired they had a subdued and resigned air about them

which seemed to indicate defeat, but it was only the meekness of a

great sense of victory, for that very night Jabe, by tortuous and

difficult processes, understood only by the initiated, caused it to

be known that he was sacrificing his principles for peace sake, and

that the bazaar would be held.

In a few days all Beckside was working and begging for the

sale. It was intended to be held in the following February,

and as the time of opening drew near, the whole neighbourhood became

excited about it. Church people from Brogden offered to help,

and the families of the two brothers who owned the Beckside Mill

took hearty interest in the enterprise.

Jabe and his confederates became positively nervous about it.

A bazaar had never been held nearer than Duxbury, and our friends

had many misgivings. Most of the arrangements were in the

hands of the ladies, and one or two of them were wilful and quite

irresistible women, who did not even consult the dignitaries of the

Clog Shop, and every few hours Sam Speck brought tidings of fresh

arrangements of an utterly unheard-of character, until, when the

Sunday before the great event arrived, Jabe was almost ill with

suppressed excitement.

The sale was to last two days, and the local preacher who was

appointed on the preceding Sunday brought a note from the "super"

containing hints for the management of the affair. At the

close of the note he remarked that as the schoolhouse where the

bazaar was to be held was over the Beck-bridge, and rather lonely,

it would be well to get someone to stay in the building all night,

as a protection against fire or thieves.

This suggestion was a perfect boon. After having had to

stand aside and act as mere camp-followers in the affair, the Clog

Shop authorities suddenly found themselves in charge of an important

department, and proceeded to discuss the situation with undisguised

relish.

As soon as the question was raised there were numerous

volunteers, and it seemed at one time as if there was going to be

difficulty in settling who should have the honour of defending the

schoolhouse—Sam Speck, whose father had been a parish constable, and

had bequeathed an old truncheon to his son, and Lige the

road-mender, who often at the Clog Shop fire told remarkable stories

about his achievements as gamekeeper's substitute in days gone by,

being the most clamorous.

As the debate proceeded, however, it widened out somewhat,

and in a short time the bazaar was forgotten in the breathless

interest with which the circle listened to stories of footpads,

burglars, and highway robbers.

By this time Sam and Lige seemed to show some uneasiness.

From thieves the conversation seemed to pass quite naturally to

ghosts, and by the time that Jonas Tatlock had told once more his

never-failing story of the sexton who fell asleep one night in

Brogden Church, and was awakened by a ghost which touched his hair,

leaving a white tuft amidst a plentiful shock of brown, every person

present was most satisfactorily thrilled, and the sudden falling

together of the embers in the fire sent a shock through the whole

company.

In the silence that followed every man seemed to be inwardly

resolving to swallow his own preferences and to waive any claim he

might have to the hitherto coveted honour. And so, when

conversation on the immediate question was resumed, Sam and Lige

found that all competition for the perilous honour they claimed had

ceased, and they were likely to be left in unchallenged possession.

Then Sam became suddenly generous, and intimated that he

really didn't mind very much if anybody particularly wanted the

honour.

But nobody did, and some hints dropped by Lige about the

dangers to his "asthmatic" in being out late were ignored; in fact,

the more generous Sam and his companion showed themselves, the more

self-sacrificing became the rest of the company, and Sam, at anyrate,

went home that night anathematising his own long tongue.

But real self-sacrifice brings its own reward, and so the

valiant volunteer guardsmen were comforted next day by the discovery

that they had achieved fame as heroic spirits. All day on

Monday they were receiving offers of loans of firearms of almost

every style and age, whilst bludgeons and cudgels were tendered

wholesale, and Micky Hollows, from the Gravel Hole, offered an

ingenious man-trap with powerful springs of his own invention.

This popularity, of course, had its effect on the two daring

spirits, and when the policeman sauntered into the Clog Shop on

Monday night, and volunteered to assist them, his offer was

slightingly — almost scornfully declined.

The next day, "Poncake Tuesday," was the opening of the

bazaar. All passed off well in spite of the fuming and

agitation of Jabe, and when the first day's proceedings were over,

and it was announced that £93, 17s. had been taken, everybody went

home tired but happy.

As the buyers and sellers dispersed, much interest was

excited by the arrival of Sam and Lige to mount guard over the

building and its valuable contents. Sam carried a thick cudgel

over his shoulder, and a pistol sticking out of each pocket, whilst

Lige had an old gun, one of his own long-handled stone-breaking

hammers, and an old-fashioned powder-flask, whilst he led by a chain

Long Ben's big yard dog "Tenter." Feeling that admiring and

even envious eyes were upon them, the watchmen marched towards the

stove in the middle of the schoolhouse, and very self-consciously

proceeded to arrange their weapons in order.

When the general public had gone, Jabe, Ben, and a few of the

others stayed behind with the watchers, and smoked a social pipe

whilst they recounted the successes of the day. When they

talked of going, Sam, who seemed somehow to have laid in quite a

stock of new or revised stories, began to tell them faster than

ever, putting into the relation rather more than his usual

animation. Then he invited them to taste a brew of hot coffee,

which he proceeded to make; and so it was past midnight when the

last lingerers departed, and the valiant defenders of church

property were left alone.

For a time they stood in the road listening to the retreating

footsteps and voices of their friends, and then to the banging of

doors which followed, but in a minute or two all was quiet, and an

eerie stillness seemed to be in the black darkness.

So the watchmen went inside for the comfort and company of

the dog. Then they smoked, glancing uneasily up at the high

windows every now and again, and holding their breath to listen at

the slightest sound.

After a while Sam began to examine his weapons, and showed

unmistakable signs of nervousness, while Lige took frequent pulls at

a large can of warm ale, which was kept in condition by standing

near the stove. The dog stretched himself out on the floor to

sleep.

Presently Lige began to nod, which made Sam quite angry, and

he tried to draw him into conversation. But it was no use; the

road-mender was overpowered, and was sinking every minute or two

into slumber, in spite of his own and Sam's efforts to keep him

awake.

The stove was a closed one. They had been recommended

for safety's sake to use a lantern instead of a naked light, and so

the room was almost dark, and the articles that hung about made all

sorts of strange deep shadows, and assumed all sorts of suggestive

and terrifying shapes.

Sam grew so apprehensive that he dared not look round.

It was the very longest night he had ever spent. How cold it

was getting, and how awesomely quiet. Would morning

never—Bang!

Sam must have been dozing, but this bang brought him

instantly to his feet. He snatched up the pistols, held them

straight over his head, shut his eyes, and fired. One of the

pistols kicked and hurt him, and he jumped back and yelled.

The shots were followed by the furious barking of the dog,

and by Lige falling from his seat and lying on his back, where he

remained shouting, "Murther! Thieves! Fire!"

Then the dog, frantic with excitement, jumped at Sam, who

sprang back and fell over the small table on which the lantern was

standing, and extinguished the only light they had.

"Help! Murther!" shouted Sam.

"Fire! Fire!" shouted Lige, and then they both lay

panting on the floor in the powder smoke until the dog ceased

barking, and all was still again.

Presently they heard a scraping sound on the walls outside,

which set the dog barking again, and then there was a bang at one of

the high windows. A minute later, Sam, venturing to lift up

his head, saw a man with a lantern trying to open the window.

"Thieves! Help!" shouted Sam agaip, and began to grope

on the floor for a weapon, the dog the while going nearly frantic.

All at once the window flew open, a puff of cold air entered the

room, and the thin, squeaky voice of Jethro the knocker-up was heard

crying—

"Sam! Liger! wotiver's to dew? Are yo' kilt?"

In a few minutes Jethro had lowered his lantern into the room

on the end of his handkerchief, and by its light Sam rescued Lige

from the débris and opened the door, when it appeared that Jethro,

getting up early to prepare for his rounds, had remembered the

lonely watchers, and had made them a can of hot coffee, but that in

the darkness he had stumbled against the door with the butt-end of

his knocking-up stick, and had made the sharp bang which had

startled Sam so terribly.

The next day nearly all the goods were disposed of. The

handsome total of £204 was realised, and the graver spirits of the

Clog Shop were of opinion that it was worth while to have had the

bazaar, if only for its chastening effects on the irrepressible Sam.

But Sam and Lige escaped more easily than they otherwise

would have done, because another matter attracted public attention.

The bazaar had made Beckside popular, and the struggles of the

villagers with their chapel scheme evoked sympathy in quite

unexpected quarters.

One day the younger of the two gentlemen who owned the mill

sent for Jabe to the office, and proposed to him, by the help of a

party of musical friends from Duxbury, to give a grand concert in a

temporarily empty warehouse belonging to the mill. The

proceeds were to go to the renovation fund. As soon as the

scheme was described to him Jabe saw in it a grand opportunity for

the Beckside string band to display its talents, but the master,

after long and skilful fencing, managed to convince the Clogger

that, however desirable, this was scarcely practicable.

When Jabe announced the arrangements to his friends he was

almost unanimously reproached for never having proposed that their

band should give concerts. They might have had the schoolhouse

for the asking. But when it was clear that he had actually

discussed the question of the band assisting at the forthcoming

performance, and had allowed himself to be beaten, he was regarded

as having seriously compromised himself.

The concert promised to be a very grand affair, and, to crown

all, the day but one before it was to take place the master brought

news that the famous Madame Bona, a great professional lady singer,

who happened to be singing at Whipham, a town a few miles the other

side of Duxbury, had sent a special message to say that she had

heard of the Beckside concert and its object, and would like to sing

at it without fee.

This being noised abroad the fame of the lady created quite a

rush for tickets, and when the evening arrived the big warehouse,

swept out and decorated for the occasion, was crammed. The

reserved seats were filled with the local gentry, many of whom had