|

[Previous Page]

Isaac's Fiddle.

I.

Rocks Ahead.

HO! ho! ho!

hoo'll ha' me! Hoo'll ha' me! Hoo says hoo'll ha'

me!" laughed Isaac to himself, as he walked down the "broo"

homewards, on the night of Lizer's acceptance of him.

His head rolled about, his hands were thrust deep into his

greasy fustian trousers, and he seemed to walk on air; whilst every

limb of his body appeared to be working on springs. His

delight was almost uncontrollable.

When he had got past Long Ben's he stopped and looked up.

The sky was full of soft light, and though it was not yet dark, the

stars seemed so close and bright that they appeared to challenge

him, and so, lifting his head, he cried joyfully―

"Capt? Ay, Aw'st think yo' arr capt. Aw'm capt

mysel'! Bud it's trew! Hoo'll ha' me. Me! Aw tell

yo'. Hoo said hoo wod hersel'," and he burst out into a great

triumphant laugh.

A moment later he had reached his own little dwelling, the

door of which he had left open on departing to see Lizer home.

On the threshold he stopped and pointed to a flag a yard or

two nearer the fireplace.

"It wur theer," he cried, "just theer. Hoo wur stonnin'

o' thatunce," and the foolish fellow produced a grotesque imitation

of Eliza's naturally graceful attitude. "An' hoo said it

hersel'. An' hay, hoo did say it noice; hoo did fur shure."

The house seemed strangely empty and unresponsive.

Isaac felt he must give expression to his feelings, and there was

nobody to talk to. Just then he spied the birdcage hanging in

the inside of the chimney-jamb with its dropsical-looking occupant

fast asleep. Even a bird was better than nothing to tell his

happiness to.

"Naa, then," he cried, giving the cage a sharp rap. "Wakken

up, wilta. Did t'yer what hoo said? Tha owt to sing, mon!

Sing till tha brasts thisel'. Hoo says hoo'll ha' me. Bi

th' mon, if hoo does Aw'll bey thi a new cage."

The bird, startled out of its sleep, hopped clumsily into the

middle of its little house, opened the eye nearest to Isaac with a

startled protesting look, and then drowsily closing it again, dozed

off once more to sleep.

Isaac turned away and went and stood in the doorway. By

this time it was as dark as it ever would be that night, and the

village sounded strangely still. Leaning against the doorpost,

Isaac glanced up and down the road two or three times as if seeking

someone to whom to tell his great secret; but not a soul seemed to

be stirring.

Then he stepped out gently, closed the door after him, and,

crossing the road, turned hurriedly into "Sally's Entry," and

hastened through the mill yard and along the mill lane, and in a

moment or two was standing under the lilac tree at the bottom of

Jonas's garden.

For several minutes he stood looking in a sort of triumphant

ecstasy at the windows, first downstairs and then up. He had

never even heard of serenading, and couldn't have sung if he had, so

he propped his chin on the flag fence under the lilac bush, and,

looking from one window to another, he murmured thickly―

"Tak' cur on her, Lord! Tak' cur on her! Tha's

tan wun guardian hangil off me, bud Tha's gan mi anuther."

Then he paused, and looking over his shoulder as if to answer

some invisible objector, he went on.

"Simple? Aw know Aw'm a bit simple, bud hoo isna?

Hoo's as sharp as a weasel, an' as bonny as a rooase, and hoo says

hoo'll ha' me, an' Aw cur fur nowt nor noabry if hoo does."

And suppressing with difficulty another great laugh, he moved away

towards home, stopping every now and then as he went along, and

glancing proudly back at Jonas's windows.

His heart gave a little leap as he passed the Clog Shop, for

he suddenly noticed by the starlight that Jabe was standing smoking

at the shop door, and great as was his joy and confidence, the sight

of that terrible form quite chilled him.

He had not altogether recovered when he reached home, and on

entering the cottage he carefully closed the door as if apprehensive

that his master might be following him.

Standing on the hearthstone, and looking round in the dim

light, he noticed a little can of milk, and, picking it hastily up,

he "swigged" away at it until the last drop was gone.

As he put the can down again slowly and meditatively in the

faint light he touched something that gave forth an indistinct

strumming sound. It was his old fiddle.

The preoccupied look which had been on his face ever since he

had seen his master vanished like magic, a gleam of eager joy came

into his eyes, and, groping about on the table, first for the

instrument and then for its bow, he cried delightedly

"Hay! is that thee, owd lad? Come here wi' thi," and

snatching it up and holding it out eagerly, whilst his face beamed

with admiration and gratitude, he cried―

"Sithi! If Aw didna want to play on thi Aw'd ha' thi

framed. Bless thi owd hert, dust know wot tha's dun?

Tha's getten me a sweetheart, mon! Th' bonniest wench i' th'

Clough. Ay, or i' th' country oather. Hay, bud thwart a

grand un. Aw nobbut gan three shillin' fur thi, bud Aw wodna

tak' ten paand this varry minute."

And then he grasped it again between his fists, and shook it

as a sign of excessive affection, and holding his coat sleeve in its

place by doubling his hand over it, he gently polished the already

shining back, and looked as though he would kiss it.

"Sithi," he cried at last, holding it out at arm's-length and

gazing at it with ardent admiration, "Aw wodna part wi' thi fur aw

th' instruments th' Clog Shop iver hed in it, an' wotiver comes an'

wotiver goos, thee and me niver parts―niver, neaw niver!"

Poor Isaac! If he had known—but fortunately he did not.

And so, after polishing it and caressing it and doing all sorts of

ridiculous things with it to show his affection, he finally put it

tenderly away in the chimney-corner, and went to bed.

Next morning, in spite of a restless, almost sleepless night,

Isaac was in, if possible, higher spirits than ever. Rising

earlier than usual, he waylaid Old Jethro on his knocking-up rounds,

and dragged him into the cottage to have a cup of hot coffee, and

when the old man was departing he called him back, and with an air

of mingled mystery and delight, said eagerly―

"Jethro, afoor th' wik's aat yo'll yer summat. An' it's

trew, moind yo', every wod on it," and then darting indoors, he

banged the door upon his old friend and set up another great laugh.

Then he tried to engage the "throstle" in a whistling

competition, but his own notes were so loud and shrill from sheer

excess of happiness that the poor bird realised at once that he had

no chance, and retiring from the contest, stood looking at Isaac in

amazement and apparent perplexity.

Ten minutes to six found our young clogger dodging up and

down Mill Lane, in the hope of seeing, and maybe even speaking to

his sweetheart, but when she at last appeared he had to resist a

sudden temptation to run away. And as Lizer caught sight of

him, and actually left the two girls she was walking with and

crossed the lane to speak to him, even the exhortation she gave him

to "goa whoam, and donna mak' a foo' o' thisel'," failed to damp his

joy, and he went down the "broo" again, struggling with a great

desire to shout.

At seven o'clock he went to the Clog Shop, and after opening

the shutters and lighting Jabe's parlour fire and putting on the

kettle, he sat down before the back window to work.

But he was very restless. Taking a partly-finished clog

between his knees, he sat looking musingly at it and smiling every

now and again at his evidently delightful thoughts.

Presently he got up, threw open his window, and seeing a

cluster of roses hanging over the window frame, he plucked one, and

filling the bottom part of an old oil-can with water, stuck the

flower in it and set it on the bench before him. Then he began

to work again in a sudden hurry, and as he worked he whistled.

Then the whistle grew into a hum, and in a few moments, in entire

forgetfulness of everything but his own great happiness, he burst

out singing— if singing it could be called.

The sun was pouring its warm rays through the window and

bathing him in golden light, the waving corn on the hillside beyond

his master's garden seemed to smile with him, the birds were singing

blithely in the trees that fringed the garden in evident sympathy,

and all nature seemed to him to felicitate him on his great

gladness. The singer, though his tones were harsh and

unmusical, had thrown back his head, and was almost shouting in the

excess of his joy, when suddenly a whole shower of clog-tops came

flying at his head.

He stopped, and, with his mouth still open, turned in the

direction from whence the missiles came, and lo! quite near to him

was his dread master, standing glaring at him in the parlour

doorway.

Jabe was very scantily apparelled. His stockings had

been pulled hastily upon his legs, the feet part of them still

flapping about. His blue-striped shirt was stuffed hurriedly

into his trousers, which were held in their place by a single brace,

the remaining one hanging down behind and dangling about his legs.

He still wore his red-tasselled nightcap, and the face below that

headdress was something terrible to behold in its indignant

sternness.

"Wot's to dew wi' thi, thaa yowling swelled yed?" he demanded

in gruffest anger.

Isaac felt a momentary shock at the sound of his master's

voice, but his joy was so great that even this fearful apparition

could not daunt him, and so, dropping the clog he was working upon,

he rose hastily to his feet and cried―

"Aw conna help it, mestur. Aw'st brast if Aw dunna

sing. Hoo'll ha' me! Hoo says hoo'll ha' me!"

Jabe stood in the doorway glaring at his apprentice with

fixed, stony gaze, but not a word did he utter.

"Lizer, mestur! Lizer Tatlock. Hoo says hoo'll

ha' me."

Jabe's face became grimmer and stonier than ever, every

muscle seeming to be perfectly rigid.

"Hay, mestur, Lizer'ud mak' a—a—a—wheelbarrow sing.

Hoo'd mak' yo' sing if hoo said hood hev yo'."

The grotesque figure in the doorway neither moved nor spoke,

but still stood gazing in annihilating scorn on the poor apprentice.

Presently the short leg gave a sort of premonitory jerk, the

eyelids twitched rapidly, and at last, in tones of withering rebuke,

the Clogger said―

"Isaac, women's bin makkin' gradely men inta foo's iver sin'

th' wold began, bud naa they've started a makkin' foo's inta bigger

foo's. Tha's bin totterin' upo' th' edge o' Bedlam iver sin'

Aw know'd thi, an' th' fost bit of a wench as leuks at thi picks thi

straight in."

And drawing himself up to his full height, and putting on, if

possible, a grimmer look, Jabe transfixed poor Isaac with a stony

eye, and then solemnly stepped back into the parlour and banged the

door.

When Jabe came downstairs into the parlour, after completing

his morning toilet, the look of stern anger had entirely disappeared

from his rugged countenance, and a pleasant, even amused, expression

had taken its place.

The fact was that the indignation that made him look so

terrible to poor Isaac had been almost entirely assumed, in

conformity with the general principles of his workshop discipline.

As he mashed his tea and cut his bread and butter a look of

mischievous enjoyment gleamed out of the corners of his eyes, and

now and then a soft relishful chuckle escaped him. As he

consumed his breakfast his merriment increased, and he more than

once burst into a laugh, whilst he slapped his thigh in keenest

enjoyment, his short leg becoming increasingly demonstrative as he

mused.

"Well dun, Isaac," he chuckled, "tha's byetten [beaten] th'

fawsest woman i' Beckside aw ta Hinters. Bi th' ferrups! bud

hoo'll mak' a shindy abaat this."

And then he rose from his chair, put on his leathern apron,

lighted his pipe, and assuming once more a grim, surly air, walked

into the shop.

All that day poor Isaac was subjected to a constant fire of

raillery.

At one time the ridiculous and impudent presumption of

"'prentice lads" and "little two-loom wayvers reaconing to cooart"

was scoffed at.

"Sich childer! wee'st ha' hawf-timers puttin' in th' axins

next."

Then the folly of marriage under any circumstances was set

forth, and dwelt upon with becoming length and exhaustiveness.

Isaac's mentor then passed by a natural and easy transition to a

diatribe on the ways and wiles of women.

Soon the tormentor became ironical, and pretended to offer

his misguided apprentice sincere commiseration on his reckless act

and its terrible consequences, and finally he dropped into a

humorous vein, and affected curiosity as to the art and mystery of

courtship.

All this Isaac bore with buoyant equanimity, having, in fact,

anticipated something very much worse. Late in the afternoon

the unusually garrulous Clogger started a new line of thought.

He had been sitting in the inglenook chatting with Sam Speck, after

baggin', and when his visitor had departed he still sat musing in

the fireless corner. All at once, however, he whisked round,

and eyeing his apprentice with a look of stern reprobation, said―

"Tha'rt a bonny mon ta steil anuther felley's wench, artna;

an' thee a member tew."

The self-complacent, almost consequential, simper which

Isaac's plain face had worn most of the day suddenly vanished, and

in its place came an expression of blank surprise and sorrow.

For, in all the hours of his happiness since Lizer's acceptance of

him, strange though it may appear, he had never once thought

seriously of Joe Gullett, and now that he was suddenly reminded of

him, the sun of his gladness suffered an almost instantaneous

eclipse.

A customer came in just at that moment who had left a pair of

clogs to be reclogged, which Jabe had decided were not worth it, and

as this meant a battle royal, exactly to the pugnacious Clogger's

heart, poor Isaac was left for a while to his own painful

reflections.

"Hay, dear!" he sighed forlornly, looking out through his

little window, "happiness doesn't last lung! Wheniver Aw wur a

bit marlocky my muther uset say as Aw shud sewn hev' a clewt at th'

t'other soide o' mi yed; an' it is sa." And then after a

moment or two of most melancholy musing, he groaned―

"Poor Joe!"

Presently he began to see himself as an interloper and thief.

He had stolen an old friend's sweetheart. Basely stolen her!

And not fairly either. Hadn't he employed the subtle and

irresistible witchery of fiddling to accomplish his selfish purpose?

And he began to feel much as a person would do who had obtained some

coveted possession by basely resorting to sorcery.

But just then the memory of certain quite irresistible

glances and certain most seductive tones which he had seen and heard

the night before under the lilac tree came back to him, and sent

such a sweet thrill through him that in a moment or two Isaac found

himself contemplating a certain young clogger so bound in the

enslavements of love that he had become utterly reckless of all

moral or spiritual considerations whatsoever, and this, as it

intensified his sense of guiltiness, compelled him to regard himself

as a mass of meanness, selfishness, and treachery.

Just as he felt himself sinking deeper and deeper into this

slough of iniquity, he suddenly heard a loud whisper―

"Isaac!"

Isaac started guiltily, made a fussy pretence to be working,

and then glanced furtively round to see who was calling him.

It was Sam Speck. Jabe was still engaged in a loud

unsparing denunciation of the "scrattin' ways" of the owner of the

condemned clogs, and so Sam had come in and taken his seat in the

fireless inglenook without being noticed. He was perched on

the outermost edge of a superannuated clog bench, which now did duty

as a fireside seat, and was leaning forward as far as he could so as

to be able to whisper to Isaac without being heard. And as

Isaac glanced round in response to the call, he put his hand to his

mouth and called out quickly―

"Tha'll cop it, lad! Bet Gullett's fair raving yond'!

Hoo says hoo'll leather thi," and then as the door banged to, and

Jabe's customer, vanquished and humbled, left the shop, Sam turned

round to conceal what he had been doing, and entered into

conversation with his chief, whilst Isaac was left to his own

tormenting reflections.

Betty Gullett was the village termagant, and a terror to all

peaceable people. The one soft place in her heart was that

filled by her son Joe, and Isaac suddenly realised that he had made

a most formidable enemy, who would stick at nothing to accomplish

her revenge.

Isaac was not, of course, afraid of any mere physical

castigation that might be in store for him, but in his excited fancy

he saw himself attacked on the road, or outside the chapel, or even

in his own house, by a fearful woman whose very husband had run away

to America years ago to be out of reach of her tongue and temper.

By this time he was in a cold sweat. The hand that

limply held the clog-top he was stitching positively shook, and his

emotions were so distracting that he could neither work nor think.

He felt sick, and for the first time in his life he could not cry to

relieve his distress.

He had sat in his place fighting, now with a reproaching

conscience and then with his own quaking fears, for some time, when

presently he became dimly conscious that he was being made the

subject of a muttered conversation in the inglenook. And now

Sam Speck and his gruff employer suddenly appeared to his distorted

fancy as kind friends, instead of the cynical critics he had ever

regarded them. He would sooner face them a hundred times than

endure one five minutes of Betty Gullett.

Another moment, and in his anguish he would have got up and

unbosomed himself to them, and thrown himself on their pity and

protection; but just then others of the Clog Shop cronies came in,

and Isaac, with a despairing gasp, shrank back into himself again.

The hour that followed was probably the longest of Isaac's

life. Would "knocking off" time never come? One five

minutes he was working desperately; the next he was gazing out of

his window with a woeful, desolate look.

Oh, what a wretch he had been to steal another lad's wench!

What would people think of him? He would never be able to hold

his head up in Beckside again. But he was being most

deservedly punished. Judgment had overtaken him with most

exemplary swiftness; and as the squat form and red face of Mrs.

Gullett rose before his mind, she appeared to him as an awful

avenging sprite. Then he fell to pitying himself as an unlucky

wight, and a poor friendless orphan, and here relief would have

come, for he felt he could cry but for the close proximity of so

many unfeeling men. Oh that he could be alone, just to relieve

his heart, as he longed to do!

And "at lung last" the old long-cased clock just inside the

parlour door began to growl as an introduction to barking — that is

striking; and by the time the latter operation was concluded, Isaac

was out of the shop and hurrying down the "broo" to the little

cottage where he knew he would be alone.

And now an extraordinary thing happened. As Isaac

turned homewards, with his head down and his heart thumping at his

side, he began to pray, and as he prayed he reached the cottage door

and commenced fumbling in his pocket for the lever of the latch,

which was the only form of key he used. And if any curious

reader interested in spiritualistic manifestations will make a

journey to Beckside, the present occupant of the Clog Shop will tell

him that just as he was putting the sneck into the door on that

memorable evening, he distinctly heard a voice say to him, "Goa ta

Lizer," and he will ask you, in a voice that rebukes all scepticism,

"Wurn't that a hanser ta pruyer?"

Answer or no, voice or no, it came to poor buffeted Isaac as

a revelation.

Of course! Why had he never thought of it before?

Lizer was equal to anything—equal to anything—even to Betty Gullett.

It took only a very few minutes for him to get some hasty

apology for a supper.

A great load had been taken off his mind. Leaving Lizer

to deal with his terrible she-enemy, and relying on old

acquaintanceship and a close knowledge of Joe's disposition, he

would do his best to conciliate his rival. He would apologise.

If absolutely necessary, and Lizer didn't object, he would tell Joe

the whole truth as to how he came to get Lizer at all, and surely

that would pacify him.

But his first duty was to see Lizer, and after Lizer, Joe.

With these thoughts in his mind, he started for his

sweetheart's house. Perfectly satisfied and at ease as to

Lizer's ability to deal with the greater enemy, he began to arrange

in his mind his own interview with the injured Joe. He grew

surer and surer that he could mollify Joe. He would seek him

out immediately after seeing Lizer, and get it done with and off his

mind.

He hoped he would be able to find Joe. It would be

disappointing if he couldn't, or if Joe wouldn't talk to him when he

did find him, but he would hope for the best.

Hello! Isaac had by this time nearly reached Tatlock's

house, and was stepping forward at much more than his usual pace,

when lo! right under the lilac tree, the scene of last night's great

happiness, stood Joe himself.

Isaac pulled up suddenly; his heart gave a great leap; he

began to shake from head to foot. Joe had seen him, and was

actually coming towards him, so that the interview so eagerly

desired a moment ago would be got over at once. Isaac

hesitated a moment, tried to move, but felt as if he could not; put

his hand to his head, grabbed frantically at his cap, and the next

moment, cap in hand, he was fleeing along Mill Lane as fast as his

shaking legs could carry him.

――――♦――――

Isaac's Fiddle.

II.

Remorse.

DOWN the lane,

through the mill yard and along Sally's Entry, rushed poor Isaac,

evidently making for home. As he neared that haven, however,

he began to have misgivings as to its security as a place of refuge,

and so, when he reached it, he rushed past and down the "broo" and

over the bridge, turning to the right on the other side, and

scudding along the path up the Beck side, glancing apprehensively

around every few yards to see if he were being followed.

When he had got some half a mile up the Clough he slackened

pace, for no pursuer was in sight. Then he sat down on the

Beck side to get his breath, moaning and groaning in self-disgust

and fear. Then he grew quieter, and, as it was now nearly

dark, he began to pick his way across the stones in the Beck, and to

steal slowly but fearfully homeward.

He hesitated for some time before approaching the cottage,

but now the desire to see Lizer, and the fear of what she would say,

first of his absence and then of his cowardly flight before his

rival, were urging him forward as strongly as his fear of meeting

Joe was holding him back.

Very cautiously he approached the backyard wall in Shaving

Lane. Then he climbed clumsily over it into the disused

hencote, where he would fain have rested; but by this time his

concern about Lizer had grown so strong that he could not keep

still, and in a few moments he had re-climbed the back wall, scudded

along the lane again, and striking the footpath that led up into the

Duxbury Road, he was soon stealing carefully past the chapel and the

Clog Shop on his way to Tatlock's house.

"Isaac!"

The young clogger nearly jumped out of his skin. The

voice came from somewhere behind him, and as he remembered the voice

he suddenly realised that he must have passed Lizer somewhere and

never seen her. The girl was standing with a shawl over her

head, under the hedge of a garden, and he must have almost touched

her as he passed.

She was evidently shaking with quiet laughter, and began to

question him quite innocently as to where he had been, and why he

had passed her "sa independent."

Now Isaac had vowed half a dozen times within the half-hour

that no power under the sun should ever induce him to tell Lizer why

he had so ignominiously fled, and so in a clumsy fashion he tried to

fence. And Lizer only laughed a soft delightful sort of laugh,

and pretended to be quite satisfied with his lame and contradictory

explanation.

But, somehow,—Isaac never could understand how it came

about,—ten minutes later, as they stood once more under the lilac,

he was telling his sweetheart, without ever being asked to do so,

all that he had suffered during the day, not omitting his terror of

Mrs. Gullett, and his sudden flight from the presence of Joe.

Sad to relate, Lizer laughed, and not a mere good-behaviour

laugh either. Under a surface of demure sobriety, even Isaac

could see that she was secretly revelling in amusement and delight.

She enjoyed his description of his many misgivings and

heartrendings; she enjoyed even more his terror of Mrs. Gullett; but

when it came to his pathetic and sympathy-seeking account of his

flight from Joe, the hard-hearted little "hussy" could no longer

control herself, and broke out into a long rippling laugh—a laugh

which made her little body shake all over, and even brought tears of

delight into her eyes.

Isaac felt chagrined, and had to struggle more than once to

overcome that unfortunate tendency of his to tears. And then

Lizer seemed to understand, and lightly changed her manner, so that

by the time they parted that night she had somehow contrived to

inspire her lover with some of her own contempt for the terrible

Betty, and had also impressed upon him the necessity of doing all he

could to comfort the forlorn Joe.

Now this last idea was so much in harmony with his own

feelings that Isaac readily promised and resolutely determined to

carry it out. But though he told himself twenty times a day

how eager he was to meet young Gullett, it was odd that no

opportunity seemed to present itself, and when it came to actually

setting out to look for Joe, it was astonishing how many things came

to prevent him, and how easily he allowed himself to be overcome by

them. Saturday night came, and he had not even seen his rival.

Moreover, do as he would, he could not get over his terror of the

terrible Betty, and every time the Clog Shop door opened he gave a

nervous start, and held his breath in torturing suspense until he

heard the actual voice of the new-comer and was reassured. Not

once in those days did he dare turn round to see who the visitor

might be.

Saturday and Sunday nights were regarded as the great

courting nights in Beckside, and Isaac spent the whole of the former

evening in most delightful intercourse with his lady-love, and was

in a seventh heaven of delight.

Next morning, however, there came a change. Isaac had

for some few weeks now been taking the violin part in the

singing-pew, but that morning as he went into school Lizer's

youngest brother, Jacky, stopped him, and told him that his father

wished him to keep away from the singing-pew that day. That

sounded ominous, and Isaac became at once very uneasy.

When chapel commenced he saw with alarm that Joe's place

amongst the singers was vacant, as was also that of Sophia Gullett,

Joe's sister.

A minute later, Isaac felt a "crill" run down his spine as

Mrs. Gullett, accompanied by her only son, stalked into the pew

immediately in front of his. Twice, at least, during the

singing of the first hymn Mrs. Gullett turned half round, and stared

coolly and contemptuously at poor Isaac, each time sending him into

a cold sweat.

Then in the prayer Isaac heard Joe sigh, and this made him

feel worse than ever. Once he caught Sophia looking at him as

if he were some awful monster, and the sorrowful reproachfulness of

her glance as she turned away nearly brought the ever-ready tears

into his eyes.

Oh dear! what a miserable fellow he was! But it was

only another illustration of his master's oft-repeated proverb that

"the way of transgressors is hard." As the service proceeded,

Joe kept sighing, and every sigh seemed to go through the unhappy

Isaac, his only consolation in these painful moments being to take

long reassuring looks at his sweetheart.

The service seemed a terrible length, and towards the end of

it another tormenting thought took possession of him. Mrs.

Gullett would be sure to attack him when the service was over,

perhaps in the very chapel itself. There was nothing for it

but to go out before the service closed. But no; that would be

to openly manifest his cowardice, and Lizer wouldn't like that.

What must he do? They were singing the last hymn.

Another moment and it would be too late. The music stopped,

and the people began to kneel.

Now for it! Isaac slid his hand softly down over the

side of the pew door. He partly opened the door. Mrs.

Gullett was moving. He grabbed at his Sunday "crow" (hat),

rose softly to his feet, and made a rush.

Alas! alas! the matting outside the door had puckered, and as

poor Isaac started down the narrow aisle, his Sunday boot caught in

a fold, and he went sprawling full length on the floor.

How he got up, and out, and home that day he never knew.

And in the afternoon the chaff to which he was subjected nearly

drove him, as he said, "maddlet." To make matters worse, Lizer

seemed actually to have enjoyed his ignominious downfall, and did

nothing but titter and laugh as he poured out to her the tale of his

woes. Nay, to crown all, as he was leaving her that night she

gave him a sharp little lecture, and bade him "be a gradely mon, an'

nor a dateliss gawmlin."

Another miserable night for poor Isaac, and next day the

attack was renewed.

As soon as he got to his work in the morning old Jabe began

to "bullyrag" him as a disturber of divine worship, and an enemy of

the church's peace; and later in the day, Sam Speck, in a loud

voice, informed the Clogger that Joe Gullett was "takkin' lessons i'

boxin' off little Eli."

By evening, Isaac, made desperate from sheer misery, was

driven to the resolution to end the matter one way or the other.

All the night, therefore, after ceasing work, he was hunting for

Joe. He dared not go to the house, but he visited every other

place where it was at all likely that his rival might be found, but

all to no purpose. Then he went and hid himself in a dark

corner, opposite Joe's residence, to watch for him coming home.

But though he watched long and anxiously until one by one every

light in the Gullett house had been extinguished, no Joe turned up,

and the suffering lad had perforce to go home and brood over his

sorrows.

During that long night, as he lay tossing about in bed,

alternately lamenting his fate and praying for help and deliverance,

a great thought came to him. It made him sick as he faced it,

but slowly it took an inexorable grip of him, and after fighting

with it for an hour or more, he realised that the path of duty had

been laid before him and that there was no escape.

As soon as it grew light enough he got up and fetched his

fiddle upstairs, and then lay back in bed looking lovingly at it and

groaning, and every now and again drawing the bow gently across the

strings in an absent, pensive sort of way.

Then he got out of bed again and went downstairs, returning

almost immediately with some rubbing cloths and a bottle of little

Eli's wonderful furniture polish.

Then sitting on the bedside in his shirt,—he had never

possessed a night-shirt,—he began to take the fiddle to pieces and

clean and polish it, part by part. Carefully and lovingly

putting it together again, and replacing an imperfect string, he

then began to play, slowly and pensively at first, but as his

interest in the music deepened he grew earnest and then excited,

until, as he finished an encore on his mother's favourite tune, he

suddenly discovered that it was almost time to be at work. So,

hastily dressing, he took the instrument downstairs again, hung it

carefully in its place, and then standing away from it and looking

sorrow-looking fully at it, he cried hoarsely―

"Aw conna help it, lad! Aw'm shawmed to leuk at thi,

bud Aw conna, conna help it."

And then he turned hastily away, and wiping his eyes with the

back of his hand, hurried out to his work.

――――♦――――

Isaac's Fiddle.

III.

The Sacrifice.

TWICE that day

Isaac saw Joe Gullett, and Joe saw him, but now, strange to say, the

youth who was supposed to be almost thirsting for poor Isaac's blood

hurried away before Isaac could get near him.

But Isaac was not to be baulked. Having once realised

that the step he contemplated was inevitable, he watched eagerly for

his opportunity.

He happened to be getting in the Clog Shop coals that

afternoon, and so as the mill was "loosing" he spied Sophia Gullett

going home from her work.

Isaac dared not wait to think, and without a moment's

hesitation he darted across the road.

The girl pulled up as he drew near, and hastily drew her

shawl more tightly round her arms,

"S'phia," began Isaac, with an attempt at a coaxing smile,

"wilt dew summat for me?"

Sophia, who had had in her secret heart a sort of fancy for

Isaac for herself, and therefore felt the more aggrieved at the

choice he had made, drew a step back, and then asked, with a

tentative inflexion in her voice―

"Wot is it?"

Isaac felt the unspoken rebuff, but dared not draw back now,

and so, with quivering lips, he stammered―

"Aw want ta speik ta your Joe ta-neet. Wilt ax him ta

cum daan ta aar haase? Do, wench, wilta?"

Sophia was tender-hearted, and felt herself giving way, but

remembering the necessity of being loyal to her brother, she tossed

her head again, dodged past Isaac, and started homewards, simply

saying as she did so, with a look that gave, Isaac no clue whatever

as to her intention―

"Happen Aw will, an' happen Aw winna."

The young clogger went back to his coal-carrying very

despondently. There was no knowing what Sophia would do, and

it seemed very probable that he would not get rest to his troubled

mind that night, in spite of all his resolutions and efforts.

However, when work was over he made for home. There he

busied himself "fettlin' up" the house. Then he fetched in a

couple of bottles of little Eli's famous "Yarb beer," and then

taking down his fiddle, he laid it tenderly on the table and sat

down to wait.

He had set the door open that he might see anyone who passed,

and moving his chair so as to command as much of the road as

possible without being too conspicuous, he began his watch.

But the time passed and no Joe appeared. Isaac began to

fidget. Several times he was on the point of picking up his

violin, but restrained himself. Then he began to walk about

the house. Then, as impatience and excitement grew upon him,

he tried to whistle and even to sing, but there was no heart in his

effort, and his music soon ceased.

Presently he sauntered to the door, and, putting on a

laboured look of indifference, stood propping the doorway with his

elbows. Still no Joe, and it began to grow dark. He had

not explained his last night's absence to Lizer, and this was

evidently going to be a second wasted evening.

To a girl of Lizer's spirit this was a serious thing.

Oh, what an unlucky wretch he―

Ah! Sure enough, right up the "broo" was coming the

long-expected Joe, but he was sauntering along as if he were going

nowhere. Isaac's heart went thump! thump! His legs began

to tremble. An almost irresistible desire to flee, or to go

inside and bolt the door, came over him, but struggling earnestly

against it, he held his post.

Joe drew nearer, and Isaac had a good view of him. He

appeared to be just taking an easy evening stroll. His mouth

was puckered as if he were softly whistling, and he was turning his

head and glancing at the housetops, first on one side of the street,

and then on the other, as though he were looking for a stray pigeon,

or were interested in smoky chimneys.

And the nearer he came to Isaac the more engrossed he seemed

to be in his elevated studies. He was now only a few yards

away, but was apparently entirely oblivious of Isaac's presence.

The supreme moment had come. It was now or never, Isaac

felt. And so, assuming an air of most careless unconcern,

strangely unlike his actual feelings, he finally managed to squeeze

out―

"Heaw dew, Joe?"

Joe did not stop, though he slackened speed somewhat.

He brought his eyes slowly back from their distant occupation; an

awkward smile flickered at one corner of his mouth. He shot a

shy glance at his rival, and then quickly transferring his gaze to

the housetops once more, he answered―

"Heaw dew?"

Then there was a pause, and Joe, to Isaac's horror, seemed to

be moving on again; and so, with another great effort, he forced out

the profound remark―

"Ther's a deeal o' midges abaat ta-neet."

But even this bold advance did not entirely arrest the

progress of the tantalising Joe. He paused uncertainly, swung

uneasily round on one leg, and at length answered very slowly―

"Ay."

And then he stopped, and the two stood with half the road

between them, but for a minute or more neither of them spoke.

Presently Isaac tried again. With a sigh, and a painful

effort, he ventured―

"Eli's tarrier's kilt a rotten [rat] ta-day."

"Aw've yerd sa."

And still the two were no nearer, and watching them standing

awkwardly talking at each other from that distance, it would have

been difficult to decide which was more uneasy.

After a while, Isaac stepped timidly down from the doorstep,

and taking one stride nearer to his rival, made another remark about

as interesting as those above recorded. Then, as he made a

monosyllabic reply, Joe took a little step towards Isaac, and stood

hesitating in the road. And so they went on, moving almost

inch by inch nearer to each other, making casual and inane remarks

about anything that occurred to them, until they were actually close

together.

And then a spirit of dumbness seemed to have seized upon both

of them, and whilst Joe looked up the road very dreely and hummed a

tune, Isaac looked down the hill and seemed to be making a special

study of the schoolhouse beyond the bridge.

Then Joe made his first voluntary remark, and though it was

as little connected with the subject in both their minds as any of

his own remarks had been, Isaac plucked up wonderfully, and at last,

making a desperate plunge, he cried with quite unnecessary

excitement―

"Joe, halt seen my throstle?"

Joe never had, and so a minute later he was standing in the

house, waiting whilst Isaac found a candle with which more

effectually to exhibit his feathered friend. The candle having

been lighted, and the poor bird wakened up to be inspected, Joe

passed encomiums upon it, which were a clumsy compromise between

polite approval of the throstle and protest against too great

familiarity with its unpardoned proprietor.

When at length ornithology had been exhausted as a topic of

conversation, Isaac turned round and thrust a chair forward, so that

Joe, if he wished, could sit down. But he, somehow, could not

ask him to do so.

Then he placed the candle on the table, carefully setting it

so that it would show off the fiddle that was lying there.

Then he espied the two bottles of "yarb beer," and with a sudden but

very hollow show of cheerfulness, he gaily opened them, and handed a

foaming pint pot to Joe.

But a sudden fit of taciturnity, and even melancholy, seemed

to have seized Joe. For though he dropped into the chair near

him, he heaved a most lugubrious sigh, and tragically waved the beer

away, as though it were trifling with his lacerated feelings to

offer it.

Isaac had a sudden return of his sense of guiltiness, and

stood looking at his visitor with mournful eyes.

"Joe," he said presently in a low, husky voice.

"Wot?" came heavily and reluctantly from the afflicted youth.

"Aw allis loiked thee, Joe."

But Joe heaved another deep sigh, and sadly shook his head.

After another long silence, during which Isaac stood at the

far side of the table, now shutting his eyes tightly as if in

prayer, and now looking earnestly from the fiddle to Joe, and then

from Joe to the fiddle again, he screwed his body about as if

thereby to force the words out, and said in a voice the tremor of

which was more eloquent than any words―

"Aw've wuished mony a toime as thee an' me wur bruthers,

Joe."

Joe suddenly bent forward, and dropping his elbows on his

knees, buried his head in his hands and uttered an awful groan.

Isaac stood looking wistfully at him for a moment or two, and

then in a most pathetically coaxing tone he said―

"Less be friends, Joe."

Joe shook his head in a wearily decided manner, and heaved

another sigh.

Isaac waited a little while, and then went on, still more

anxiously―

"Joe, if tha'll be friends, dust know wot Aw'll dew?"

Isaac evidently expected that curiosity, at any rate, would

make Joe speak, but he was disappointed, for he only shook his head

more sadly and decidedly than ever.

"Aw'll gi' thi th' preciousest thing Aw hev' i' th' wold,

Joe."

Joe raised himself slowly up, and leaned back in his chair,

and partly because he felt he must say something, and partly because

curiosity was, after all, beginning to assert itself within him, he

said, with exaggerated indifference and melancholy―

"Dunna meyther me."

But Isaac was by this time desperate. He had worked

himself up to this point of excitement, and felt that he must end it

now or never, and so, seizing his cherished instrument and thrusting

it feverishly into Joe's hands, he cried―

"Aw'll gi' thi me fid—fiddle, Joe," and the poor fellow burst

into a passion of tears—for it was like parting with life itself.

Joe sat leaning back in his chair, and looking at the joists

above his head for quite a long time. Then he suddenly rose to

his feet, and awkwardly thrusting out his hand, he stammered in

choking tones―

"Shak' hons, Isaac!"

Anyone could see by the way it was done that these two

village lads had had little practice in this form of salutation, but

as they stood together on that old sanded floor, in the dim

candle-light, gripping each other's hands and looking into each

other's eyes, they entered silently into a bond which neither time

nor trial has been able to break.

"Aw winna tak' thi fiddle, lad," faltered Joe with his hand

still in Isaac's, "bud Aw'll tak' thee. Ay, an' Aw'm suman'

praad to tak' thi tew. After wot tha's dun ta-neet, Aw dunna

Wunder as Lizer loikes thi. Aw'm glad tha's getten

her—a—partly wot."

And in this strange interview this was the only mention made

of the subject of their differences. And when, as Isaac saw

his friend home, they came unexpectedly upon Lizer, and in the

fulness of their hearts told her all that had taken place, the

bewitching little besom called Joe a "lumpyed" in such a delightful

sort of way, and gave him such a tap on the cheek where any but a

Lancashire lass might have given him a kiss, that Joe, when he left

the courters, went home as nearly reconciled to his fate as could

well be expected.

――――♦――――

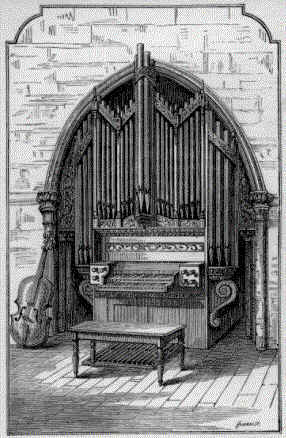

The Harmonium.

I.

An Apple of Discord.

JABE and Long Ben

had been spending a week at the seaside for the first time in their

lives. Excursions of this nature were in those days very rare

amongst Beckside folk, and this was brought about by Lige, the

road-mender. That worthy and his wife, now retired and living

comfortably in a little cottage near the "Beck," had evidently

determined to enjoy themselves for the rest of their lives, and so

gave way to habits which occasioned their friends much concern.

Amongst other questionable tendencies, they grew fond of

making little excursions abroad on visits to friends and the like.

This was all very delightful to Lige himself, although he

took his pleasure somewhat fearfully. He was troubled on every

new adventure of the kind with painful misgivings as to the

righteousness of such conduct, and vainly attempted to square

matters with his plain-spoken conscience by extraordinary

contributions to the chapel collections.

When, therefore, Jane Ann had proposed to him to go to "th'

sayside," he had had a somewhat painful struggle; and, in fact, even

when he had got to the watering-place, and was enjoying himself to

the full, he had moments of such painful self-reproach, that he hit

upon the ingenious expedient of trying to persuade the grave heads

of the church at Beckside to join them in their dubious pleasure;

and thus, by obtaining official sanction for his frivolities, to

relieve himself of at least some of the responsibility for them.

And so Jane Ann, of whose penmanship Lige was most

inordinately proud, had written a long letter, enlarging, not upon

the worldly attractions of the place, but upon the marvellous

eloquence of the preacher at the Methodist Chapel, and the beauty of

certain new tunes which were being sung there, and closing with a

most urgent request that Lige's friends would join them for a few

days.

But Lige, uneasy and impatient though he was, had to wait

several days for a reply, for so grave and altogether unusual a

matter was not to be settled all at once.

Seaside visitation was, according to Beckside standards, a

somewhat questionable practice. It savoured of pampering

self-indulgence. It was extravagant and worldly, and was

generally regarded as a sign of ostentation and frivolity. It

was some time, therefore, before the two friends could find an

excuse for the journey which satisfied themselves and those about

them. What made it worse, Sam Speck had not been invited, and

he was very stern and uncompromising in his maintenance of the

orthodox Beckside view of the case, and came down upon any weak

argument advanced by Jabe or Ben in favour of the excursion, or any

such-like worldly vanities, with unexampled fierceness, and

contrived to obtain the at any rate partial support of Nathan,

Jonas, Jethro, and the rest.

Sam's position was made the stronger by the fact that both

the Clogger and his friend found themselves surprisingly inclined to

accept Lige's invitation, but were very much ashamed at being so

weak and frivolous.

At last, however, Sam went too far one night, and so goaded

the wavering Clogger, that he suddenly arose from his seat and

announced his intention of going, whatever either Sam or anybody

else might say.

Of course, if Jabe went, Ben must go too; and as Mrs. Ben

rather encouraged the idea, and Jabe's mode of settling the

discussion transferred the moral responsibility of the whole

expedition to the Clogger's shoulders, Ben plucked up courage, and

away they went.

When they arrived at their destination, they were shocked to

find Lige so evidently carried away by his frivolous surroundings

that he met them at the station wearing a straw hat and a thin

alpaca jacket, and flourishing a rakish-looking cane. And the

light-hearted manner in which their old friend walked them into

lodgings of awe-inspiring grandeur, as if it were an everyday matter

to him, quite took their breath away.

Well, they had spent a busy and very happy week, and, having

got their faces most satisfactorily tanned, were returning on the

'bus from Duxbury to Beckside.

There was only room for one on the driver's box, and the 'bus

was kept standing several minutes at the bottom of Station Road

whilst Jabe and his friend settled which of them should occupy the

coveted seat. Ordinarily, neither of them would have cared to

travel outside, but on this occasion they were both of one mind, and

neither would give way for the other—and neither would confess that

the real reason of this obstinacy was an intense desire to catch the

very first possible glimpse of dear old Beckside.

As the reader will guess, Jabe was the successful candidate

for the outside berth; and Ben, when he got inside, went up to the

far end of the vehicle and took his seat by the window, in order to

have the next best possible view to Jabe's.

It was, perhaps, as well they were parted, for as they drew

near home, certain painful misgivings began to exercise their minds.

What had hppened to the dear old place in their careless and

unnecessary absence? They were both sure they would find

something wrong. And only justly so, either. They had

been gadding about and seeing wonderful things, and wickedly

enjoying themselves without stint, whilst the chapel had been left

to take care of itself—or what might turn out even worse than that,

to be managed by rash and inexperienced hands.

It would not have greatly surprised Ben to find his children

all ill of fever, or his shop burned down. And Jabe was by no

means sure that he should find the chapel where he left it, and all

right. Ah! how wicked they had been! Why, the very

evening of their arrival at the watering-place, as they were walking

on the sands, Lige, the trifler, had gaily challenged Long Ben to a

game at "Aunt Sally"; and Jabe was convinced that, but for his own

indignant protest, Ben would have accepted, and the world would have

had the scandalous spectacle of two pillars of the church throwing

sticks at a big, hideous-looking wooden image with a pipe in its

mouth.

On the other hand, Jabe was very uneasy lest Ben should,

after all, know what he did whilst Ben and Lige were having their

photos taken; and the uneasy Clogger realised that he would never be

able to hold his head up in Beckside again if it got out that he had

had his "bumps" felt by an itinerant phrenologist.

Neither of these men had ever been a week out of Beckside in

his life before, and as the coach drew near the village they grew

quite nervous and apprehensive as to what might have happened during

their absence, their fears being all intensified by the painful

recollections of the thoughtless and wicked gaiety in which they had

been indulging.

When the 'bus reached the top of the hill, and was going down

into the village, Jabe heaved a great sigh, and Long Ben, with his

nose flattened against the coach window, had difficulty in keeping

back his tears.

And after all nothing had happened. The chapel stood

just where they had left it, and looked bonnier than ever. The

buzz of the mill could be distinctly heard, and over that the

c-h-e-e-t, c-h-e-e-t of the saws from Ben's sawpit; and when the

conveyance stopped, and Isaac, Sam Speck, Nathan, and Jethro came

rushing out to meet them, overwhelming them with questions and chaff

about their sunburnt faces, Jabe, standing off from the group, and

looking round with unwonted seriousness on his face, cried out―

"Th' sayside's reet enuff fur them as loikes it, but

Beckside's good enuff fur me."

And Long Ben, turning his back to the group of friends, and

looking very earnestly at the mill chimney, whilst he vainly tried

to straighten a quivering face, responded―

"Ay, lad; ther's noa place loike whoam, is ther'?"

Safe home again, both our friends felt inclined to laugh at

the fear that had spoilt the pleasure of the return journey, but

almost immediately other thoughts began to trouble them. Jabe

wondered whether Ben really did know about that phrenologist, and

Ben felt himself going red about the ears as he thought of the

dreadful possibility of Jabe blurting out the truth about the "Aunt

Sally."

These things were too shameful even to be discussed by them,

and so, though they had abundant opportunity as they came home of

entering into a compact, neither of them had ventured to suggest it

to the other. Fortunately Lige had stayed behind a little

longer, and so could not expose them; but what if he came home and

in his garrulous way blurted out the whole story?

At the Clog Shop that night there was, of course, a full

assemblage, and as Jabe and Ben described what they had seen, and

marked the effect of it on the company present, they forgot their

pricks of conscience, and were very soon on the best of terms both

with themselves and each other.

Jabe, of course, was the chief spokesman, and he sat in his

shirt-sleeves with a new long pipe before him, smoking a wonderful

brand of tobacco to which Lige had introduced him, and enlarging on

all they had seen and heard. He dismissed the ordinary

attractions of the place in a very summary manner, although Ben

confessed afterwards that he "fair crilled" as Jabe mentioned "Aunt

Sally" a second time. And when Jabe paused for a moment to

relight his pipe, Ben seemed inclined to take up and continue the

story, for he drawled―

"An' ther' wur wun o' them—them bumpfeelin' chaps—an'"―

But here Jabe broke in with most unwonted haste―

"Th' Ranters wur howdin' camp-meetin's upo' th' sonds; an'

hay, wot singin'!"

Having thus got the conversation into smooth waters again,

Jabe passed on to what he knew would be more interesting to the

company, and described the big chapel they had attended, and the

preachers, and the music; and the company noted with interest that,

instead of describing the leaders of the music as the singers, he

called them the "kire," and even the singing-pew itself was

denominated the "horkester"—which were regarded as signs that even

the sturdy ecclesiastical conservatism of Jabe had been relaxed by

his short sojourn abroad.

"Haa mony wur ther' i' th' band?" asked Jethro at this point.

"Band? thaa lumpyed; it wur a horgin."

Sam Speck, who, with the memory of his late ill-treatment on

his mind, had hitherto manifested an ostentatiously supercilious

indifference, now suddenly woke up, and glancing significantly at

young Luke Yates, who sat near him, leaned his head against the

chimney, and winking mysteriously at Jonas Tatlock, said quietly―

"Ay! bands is gooin' aat o' fashion fur chapils."

"Soa mitch wur fur th' chapils, then," retorted Jabe with

emphasis.

Sam and his friends glanced at each other again, and the

conversation seemed somehow to have got stranded.

"We went to th' Independent Chapil i' th' afternoon; it wur

th' Sarmons,"—said Long Ben at length,—"an' talk abaat singin'"— But

Ben could find no words in which to express his admiration, and so

he nodded with most eloquent suggestiveness at Jonas.

"Wur ther'a band theer?" asked Sam, whose mind seemed somehow

to run very oddly on this subject.

"Neaw; ther' wur a harmonion."

Sam's eyes sparkled, and after turning and looking

significantly over his shoulder at those who sat nearest to him, he

drew a long breath, and asked quietly―

"An' th' music wur tiptop, thaa says?"

"It wur that," replied the carpenter, putting as much weight

into his words as he could make them carry.

Sam was conscious that Jabe was studying him curiously, and

so he moved restlessly in his seat. Then, after a pause, be

dropped his voice somewhat, and remarked with a very awkward attempt

at indifference―

"That's wot we wanton here."

Ben opened his eyes a little, and then, looking at Sam

interrogatively, he asked―

"Uz! wot dun we want?"

Sam cast another look at those nearest to him, and then,

wincing as if in anticipation of a blow, he said softly―

"A harmonion."

Everyone in the company shot a quick glance at Jabe, and as

quickly turned away again, whilst the possessors of those eyes held

their breath as if anticipating an explosion. But the Clogger

neither moved nor spoke. His rugged face became a shade

sterner, but for any other sign he gave he might never have heard

Sam's remark.

The silence that followed was most unpleasant, and so, to

relieve it, Long Ben looked across at Sam, and asked―

"Wot dun we want wi' a harmonion?"

Sam stole another quick glance at Jabe, whose silence was

more ominous than any speech, and answered sulkily―

"Well, we dew. Th' Clough Enders hez wun, an' th'

Brogdeners hez wun, and they'n tew at Duxbury Schoo'."

Sam sat like a naughty boy expecting a box on the ear.

And the rest of the company stole shy, quick glances at the Clogger,

whose silence under these conditions was a sort of slow torture.

Presently Ben went on―

"Dust know what harmonions cosses?" (costs).

"Cosses? Ay!" replied the now desperate Sam. "We

can hev a gradely good un wi' six stops in fur ten paand, an' Jimmy

Juddy says he'll gi' tew towart it."

Then two or three others added details, and for the next few

minutes they talked eagerly, but somewhat nervously, on the subject,

evidently unconscious of the fact that in every word uttered they

were betraying themselves to the silent and inscrutable Clogger.

In the discussion thus initiated, it gradually became clear

that, immediately after the departure of Jabe and Ben for "th'

sayside," Sam and Luke Yates had begun to carry out a long-cherished

plan of agitating for a modern musical instrument for the chapel.

The suggestion had met with more encouragement than they had

expected—Jethro, the knocker-up, being their only serious opponent;

and, as he was not of much account, and was clearly prejudiced, they

had, by the time the two excursionists returned, nearly perfected

their scheme.

Amongst other things, they had got a lot of tentative

promises that nearly covered the proposed outlay, and an illustrated

price-list of very attractive looking instruments.

At this point, Sam produced from his pocket a gorgeous

catalogue, with one of the leaves carefully turned down, and,

opening the book at this particular page, he looked anxiously round

for someone to whom to present it.

But, though they had all examined it several times a day for

the last few days, they seemed to have suddenly lost all interest in

the matter, and shrank from accepting Sam's offer under the stern

eye of the terrible Clogger. Sam bent forward and nervously

thrust the catalogue towards Long Ben, but that worthy looked

straight before him and absolutely ignored the document. Sam

was visibly agitated, and would gladly have put the list back in his

pocket, but he either could not or dared not, and so he held it out

hesitantly and looked at it a long time, conscious that everyone was

watching him, and finally, making a desperate effort, he got up,

strode across to where Jabe was sitting, and, pointing with his

finger at a picture of a very imposing looking instrument, he cried

"That's it, sithi. Wee'st ha' sum music when we getten

that."

Jabe was sitting with his short leg flung carelessly over the

other against the opposite side of the chimney-jamb, and to

everybody's surprise he put out his hand, and in a listless,

indolent fashion took hold of the catalogue and glanced at the

indicated picture.

Then, still holding the list between his thumb and finger, he

lolled back lazily, and fixing his eye on a thick cobweb in the

corner of a walled-up side window, he said, with a slow impressive

shake of the head―

"Aw'll tell yo' wot, chaps; we liven i' wunderful toimes."

Everybody was surprised and mystified, and whilst one or two

of the conspirators began to show an inclination to hopefulness, the

more experienced hung their heads apprehensively.

Nobody replied to Jabe's enigmatical remark, and so in a

moment or two he shook his head more seriously than ever, and still

contemplating the cobweb, added―

"Wunderful toimes."

But, even then, nobody responded, and the older ones present

glanced pityingly at Sam.

"Iverything's dun by machinery naa-a-days," continued Jabe,

putting on a look of carefully simulated wonder. "We'en

spinnin' machines, an' weyvin' machines, an' sewin' machines, an'

weshin' machines, an' naa, bi th' ferrups, we'en getten

warshippin' machines," — and absorbed with the contemplation of

all these modern marvels, Jabe stared at the cobweb in rapt

astonishment.

"Machines?" began Sam indignantly, but two or three put out

their hands and checked him, whilst the Clogger, still gazing at the

spider's habitation, went on with slow and painful deliberateness―

"Wee'st ha' prayin' machines an' preichin' machines next.

Naa, if nobbut some handy chap 'ud mak' a machine fur turnin' sawft

gawmliss bluffinyeds inta gradely felleys, Aw'd bey wun mysel'.

Ther'd be plenty o' wark fur it i' Beckside."

There was a sudden sputter of half-amused, half-angry

laughter, which relieved the tension somewhat. Two or three

slily drew the backs of their hands across their mouths as if they

had just tasted something enjoyable but forbidden, and Sam was

lifting his head to reply, when Jabe went on once more in a

humorously sarcastic tone―

"A harmonion, eh? We'd better send for lame Joe, an'

start a concerteena band, or else a singin'-pew full o' lads wi' tin

whistles an' Jews' harps."

Sam Speck, goaded to desperation, set his teeth, and,

clenching his fist, brought it down heavily on the bench before him,

crying in indignant anger—

"Well, we'en getten th' brass, an' wee'st ha' wun, chuse wot

thaa says."

Jabe's face became suddenly very stern. The amused,

contemptuous look upon it vanished, and, pursing his lips, and

drawing together his brows, he said, with slow weighty emphasis―

"As lung as ther's a fiddle-string i' Beckside, or a felley

as can start a chune [tune], ther'll be noa harmonion i' aar chapil."

The countenances of Sam's supporters dropped visibly, and a

glint of unholy fire shot into several eyes, and as Long Ben noted

this he chimed in soothingly―

"We met use it fur th' schoo', thaa knows. We'en bin

rayther hard up sometimes lattly."

But the possibility of Ben's defection from his side roused

Jabe, and so, jumping to his feet, he shouted in his excitement―

"Ther'll be noa barril-orgins—baat handle—i' that schoo' woll

Aw'm alive," and then, after a pause—"Neaw, an' if yo' getten wun

efther Aw'm gooan, bi th' mop' Aw'll cum back to yo'."

As Jabe sank back into his seat, glaring relentless

resolution all around, a spirit of sulky depression seemed to fall

on the company; and what should have been a highly enjoyable evening

proved so disappointing, that the friends began to depart quite

early, whilst those who remained looked more and more dismal.

Scarcely had the last man except Ben departed when Jabe rose

to his feet, and, glaring at the companion of his recent jaunt, he

cried in bitter distress―

"This is wot comes o' thi sayside maantibankin'. Didn't

Aw tell thi haa it 'ud be?" And then, sinking into his seat

again with a face all a-work, he cried with added bitterness―

"Aw wuish th' sayside 'ud bin at Jericho, Aw dew, fur shure."

Now, as Ben had gone to the watering-place quite as much

because he thought Jabe wanted to go, but would not go alone, as

because he fancied the excursion himself, and as all the warnings

and misgivings had been uttered by himself, as far as he could

remember, and had been received by his friend with fine scorn, he

was somewhat surprised to have this charge hurled at him, but he

knew his man too well to reply just then. And so, after

sitting and smoking in silence for a long time, he said soothingly―

"Ne'er moind, lad; ther'll be noa harmonions i' heaven."

"Neaw, nor saysides noather," grunted Jabe.

――――♦――――

The Harmonium.

II.

The Trustees' Meeting.

IT is perhaps

necessary to explain that the musical service at the Beckside Chapel

was conducted on rather free-and-easy principles. The choir

was a fairly stable quantity, but the instrumental part of the

service was somewhat carelessly managed. To begin with, there

was only room for about four instruments in the singing-pew, and as

Nathan's "'cello" was regarded as indispensable, it only left three

places for all the rest. These places were filled by any

members of the band who took it into their heads to attend and bring

their instruments—as far, at any rate, as the limited accommodation

would allow. Jonas Tatlock always kept his violin at chapel to

be ready for those odd occasions when no other fiddler turned up,

but the music of this instrument was usually provided by Jimmy

Juddy, or Isaac the apprentice, or both. The "'cello" and the

two violins were regarded as all that were absolutely necessary for

an ordinary service, but on Sunday evenings, and on all special

occasions, the instruments would be reinforced by, an additional

"'cello," Peter Twist's clarinet, and occasionally by a double bass,

or even Jethro's trombone.

When, therefore, on the very Saturday night that Jabe and his

friend departed for the seaside, Sam Speck sprang upon the company

assembled at the Clog Shop his revolutionary proposal to introduce a

harmonium into the chapel, all the instrumentalists regarded it as a

direct attack upon their order, and resented it accordingly.

"If we getten a harmonion ther'll be noa raam fur fiddles,"

objected Jimmy Juddy, toying with one of Jabe's hammers.

"Fiddles, thaa lumpyed! wee'st want noa fiddles when we

getten a harmonion," said Sam, looking pityingly on Jimmy for his

lack of comprehension.

"Dust meean to say as if th' harmonion gooas in aw th'

t'other instruments 'ull ha' to cum aat?" demanded Jethro in painful

surprise.

"Ay, fur shure! Wot else?"

Now, up to this point there had been a disposition to at any

rate give the question a fair hearing, but now, seeing that, like

Othello's, their occupation would be gone, those in the company who

were accustomed to play in the chapel at once went over to the

opposition. One or two, however, found their positions

somewhat difficult. Jonas, for instance, who, as leader of

both band and choir, was an important person, whilst conscious of a

desire to experiment with a new instrument, felt that his own

beloved fiddle would be displaced, and that his protégé and

future son-in-law, Isaac, would be reduced to the rank of an

unimportant private member, and so he wavered, and with him were

Jimmy Juddy and one or two others.

On the other hand, Jethro, the knocker-up, in the absence of

his great leader, maintained a fierce and uncompromising opposition,

and so it happened that far into that night the Clog Shop resounded

with the noise of argumentative battle, and on the very Sunday when

Jabe and Long Ben were luxuriating in the clover of grand preaching

and grander singing, the church they had left behind was agitated

with conflict.

All through the following week the battle had continued, and

consequently, on their return, the Clogger and his friend found the

society divided into two compact and fiercely belligerent parties,

Sam Speck's being numerically and forensically the stronger, and

Jethro's making up in obstinacy what it lacked in numbers and logic.

The return of the two excursionists meant, of course, a

sudden accession of strength to the weaker party, and on the Sunday

night after their arrival the Clog Shop parlour was the scene of one

of the fiercest word-battles that even it had ever known.

Jabe had no great difficulty with his revolted lieutenant

Sam. It was comparatively easy by characteristic torrents of

raillery and satire to silence him. But there was a new

combatant in the field on this particular night—no less a person, in

fact, than Ben's son-in-law, Luke Yates. And the cool, adroit,

and aggravatingly polite style of this young man's arguments

provoked the irate Clogger almost beyond endurance. The

fiercer and more boisterous Jabe became in argument, the quieter and

more conciliatory were Luke's replies, so that the Clogger was

angered, not only by the cogency of Luke's reasoning, but also by

the consciousness that his own methods were clumsy in comparison,

and that his favourite weapon of abuse was grossly unfair.

Every now and again during the debate Long Ben would

interject some softening remark, which, though exactly what

everybody expected of him, seemed on this occasion to be unusually

irritating to his friend; the truth being that Jabe felt that the

arguments which were steadily undermining his own position would be

sure to be producing the same effect on Ben's mind, and he knew only

too well that eventually Ben would go over to the other side if only

in the interests of peace. Moreover, Luke was Ben's

son-in-law, and Jabe felt that Ben's pride in the young man's

debating power would lay him open to easy conviction.

Besides all this, Jabe, as the conflict continued, began to

have an uneasy feeling that more was involved in the dispute than

the question of the harmonium, and he found himself struggling with

a consciousness that this was the first indication that the day of

his absolute reign in the Beckside Church was over, and that in Luke

Yates the Methodist people would before very long recognise a leader

more suited to modern ideas, and, withal, altogether more capable

than himself. The Clogger, therefore, rallied all his

resources. Abuse, scorn, satire, and threatenings were all

employed without measure or mercy; and when these failed, he fell

back on inscrutable and obstinate silence, and pretended to regard

the harmonium agitation as the offspring of feather-brained and

utterly worthless individuals, of whom no serious notice need be

taken.

But as time passed, Jabe gradually discovered that he was

more alone in this matter than he had expected to be. The

doctor and his wife were both in favour of the new instrument, the

erstwhile schoolmistress, in fact, having gone so far as to promise

to play it when it was introduced into the chapel. The young

people of the Society were all enthusiastic about it, and even such

staunch supporters of old-established ways as Aunt Judy and Long Ben

wavered most disgracefully.

On Thursday, Lige returned, and though, as a rule, the

Clogger had no great respect for the old road-mender's judgment, yet

in his present circumstances he was glad of the slightest support,

and looked quite eagerly for Lige's arrival.

Alas! alas! Before he had even seen Lige, or had had

the least opportunity of sounding him on the question, he received

the disheartening intelligence that his old friend was an

enthusiastic supporter of the popular proposal.

Jabe had one hope left. The "super" would, of course,

support him in his defence of established institutions, and as that

gentleman was to preach at Beckside on the following Sunday, and was

appointed to be entertained at the Clog Shop, the Clogger comforted

himself with the hope that help was at hand, and that the

representative of law and authority would stand firmly by him.

But, somehow, when the super came, Jabe could not for the

life of him introduce the subject, and the minister, who, unknown to

our old friend, had been fully enlightened as to the state of

affairs, was almost as anxious to hear as Jabe was to speak.

But although during the day they discussed every possible subject

concerning the chapel, and the super deftly led up to musical

matters several times, Jabe always avoided them, and the evening

service was over and the minister was finishing his supper in the

Clog Shop parlour before the subject he had been waiting for all day

was introduced.

The other occupants of the parlour were Long Ben, Lige, and

Jethro, but even now the Clogger seemed to have no intention of

introducing the subject which was uppermost in everybody's mind.

"Han yo' yerd abaat th' bother as we han here, Mestur Shuper,"

asked Ben hesitantly, tilting back his chair, and puffing out a huge

mouthful of smoke.

"Bother? Bother at Beckside! I hope not," replied

the minister evasively, but with a sufficiently passable show of

surprise to hoodwink the listeners.

"Ay!" cried the Clogger contemptuously, but with a nervous

little laugh; "a storm in a tay-pot, sureli."

"A bother? A storm? What is the matter?" asked

the super, putting on an even greater look of astonishment.

"Dunna meyther," replied Jabe, with an impatient jerk of the

head, whilst his demonstrative leg began to rock excitedly over the

other, "it's nobbut childer wark."

"Childer wark? It's babby wark," cried Jethro,

leaning forward, and putting out his chin with a grim, pugnacious

expression which looked very strange on his gentle old face.

"Ay! but wot Aw want to know is which is th' babbies?"

retorted Lige doggedly.

"Gently, gentlemen, gently!" said the minister.

"Someone tell me what is the matter, please."

"Matter?" cried Jabe, rising to his feet in his excitement,

and holding his pipe away from him in one hand, whilst he

gesticulated tragically with the other, "ther's a lot o' gawmliss

young wastrils, just aat o' petticuts, an' they wanten ta rule th'

church; that's wot's th' matter."

An exclamation of dissent escaped Long Ben, and Lige and

Jethro both rose to their feet, and began to talk excitedly.

The super, putting out his hands, cried, "Sit down,

gentlemen, please. Now, Mr. Jabez, what is the matter?"

"Matter?" shouted Jabe, rising to his feet again, in spite of

the minister's injunction. "Mun Aw ax yo' wun queshten?"

"Well, what is it?"

"Han' yo' iver yerd better music i' ony chapil yo'n iver been