|

[Previous PageJ

CHAPTER XIII.

1894 TO 1899 ―

MR. J. R. HINCHLIFFE, SECRETARY ―

MR. J. B. MASON, MANAGER ―

MEMBERS VISIT THE "WHOLESALE" ―

OTHER EXCURSIONS ―

CONCERTS ―

ELECTRIC LIGHTING

EXTENDED ―

CHEETHAM HILL ROAD

PROPERTY ―

BUCKLEY STREET PROPERTY ―

LORD STREET PROPERTY ―

ADDITIONAL STABLES ―

BUILDING RULES ―

INFIRMARY COT ―

INDIAN FAMINE FUNDS ―

MILL OPERATIVES'

DISTRESS FUND ―

ENGINEERS' LOCKOUT

FUND ―

WEST OF IRELAND DISTRESS

FUND ―

SMALL SAVINGS BANK ―

FIRST EXHIBITION ―

CASTLE HALL BRANCH

OPENED ―

TELEPHONE ―

TECHNICAL SCHOOL

GRANT ―

SOUTH AFRICAN WAR

FUND ―

HELPING RESERVISTS'

DEPENDANTS ―

VOLUNTEERS' PRIZE

FUND ―

DEATH OF MR. JOHN

HEAP.

IN February,

1894, the writer was appointed secretary in succession to Mr. J. R.

Jackson, who had held the office since 1880. The new

secretary's business career had been entirely with the society,

first as check boy, then successively as grocery assistant, clerk,

assistant secretary and treasurer, until, on the lamented death of

his chief, the committee showed their confidence by appointing him

to the vacancy.

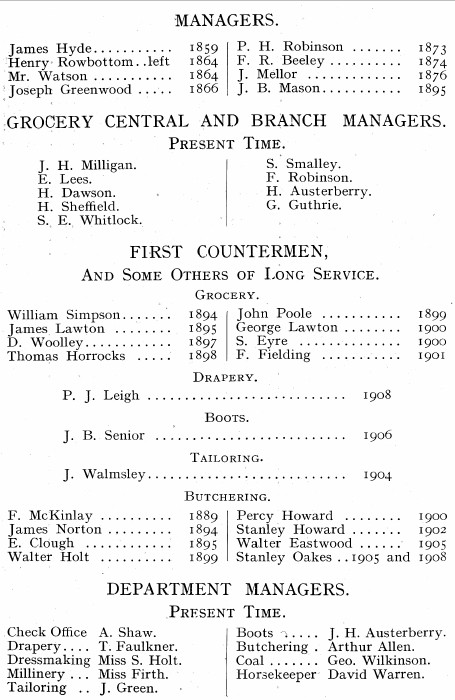

Mr. J. B. Mason, the present general manager, was appointed

on the 27th March, 1895, in succession to Mr. J. Mellor, who had

been manager since 1876. Mr. Mason seemed from the first to

have a conviction that everything depended on the turnover being

kept up or increased. He set himself to augment it, and to his

management is largely due the fact that the sales, which were

£56,300 during a year immediately preceding his coming, have reached

a total, imposing for a town of the size and with the population of

Stalybridge, of £130,000, an increase of no less than 130 per cent

in fifteen years. Whilst this increase has been making, the

remuneration of the staff has not been overlooked. Substantial

advances of wages have been made and the standard of efficiency has

been raised. There was a visit of members to the Balloon

Street premises of the Co-operative Wholesale Society on Saturday,

30th March, 1895. The cost to each visitor, including railway

fare and tea, was 1s. 6d. Six hundred persons went; they were

conducted over the premises in small parties, and tea was served by

the Wholesale Society.

On the 24th August of the same year there was an excursion to

Alderley Edge, approximately 600 persons spending a very enjoyable

day. Two trains were run, and the Ancient Shepherds' Reed Band

accompanied the party. The trip was so popular that it was

repeated on the 20th June, 1896. On this occasion the

Stalybridge Old Band was engaged, and 454 adults and 55 children's

fares were paid.

Another excursion in 1896 was to Hebden Bridge and Hardcastle

Crags on the 22nd August. Tea was served by Hebden Bridge

Society, and the accommodation was taxed to the utmost, the number

of people who attended being nearly 1,000. There were other

excursions in the 'nineties, including one to Buxton in 1897, and

another to Belle Vue in 1898. In connection with the latter,

there was given a guarantee of 600 persons to tea.

From 1894 to 1899 the committee arranged concerts rather more

freely. In addition to the annual gathering of members, there

were concerts at the Oddfellows' Hall, Millbrook School, and other

places. In September, 1895, and for several years, the theatre

was hired for one evening, and there were some very large audiences.

Popular prices were charged, varying from 1d. to 3d., with a small

number of seats in the dress circle and stalls of the theatre at 1s.

Mr. Charles Parker's Eolian Opera Company, of Rochdale, was booked

for several of the large concerts. For the annual soirιe, held

March 5th, 1898, the Stalybridge Harmonic Society, with a band and

chorus of 100 performers, was booked.

The electric lighting installation was extended at the end of

1895 by the Lancashire Electrical Engineering Company, of

Ashton-under-Lyne. A new and larger dynamo, to light about 100

16-c.p. lamps, was put in; the premises were re-wired; and early the

following year we had electric light in the office, boardroom, and

grocery for the first time. The expenditure was a little over

£200, and it was entirely written off the capital account from the

profits of two quarters.

Cheetham Hill Road property, consisting of 23 houses and a

shop, was bought in January, 1896; seven houses in Buckley Street

were purchased in October, 1897; Lord Street land was bought in

July, 1897, and the erection of 15 houses thereon commenced early in

1898 by Mr. T. G. Shaw, with Mr. Geo. Rowbottom as architect; and in

August, 1898, Mr. Tim Bradbury's tender for the erection of seven

houses in Wakefield Road, Heyrod, was accepted, also under the

superintendence of Mr. Rowbottom. In 1897 additional stables

were built in the yard off Booth Street by Mr. A. Chorlton.

The building rules were adopted in 1897. Previously

members could borrow money for building purposes under the general

rules, but the special building rules provided for the advance by

the society of a larger proportion of the purchase money, and in

other ways have been conducive to a greater number of members

becoming owners of the houses they occupy.

A subscription at the rate of 1d. per member per annum towards the

maintenance of a children's cot in the Ashton District Infirmary was

unanimously passed by the members in 1897. The cot is still

maintained by Ashton, Stalybridge, and other neighbouring societies,

and a good work is being done.

The same year there was a grant of £50 to an Indian Famine

Fund. A similar grant was made three years later. The

Co-operative Wholesale Society gave a donation of £1,000 to the 1897

fund, an action that our quarterly meeting approved.

Distress funds were somewhat numerous during the six years

1893 to 1898. The distribution of 1893 has been referred to.

At quarterly meetings held January and April, 1896, there were

appeals on behalf of the workpeople of Messrs. Adshead's and Messrs.

Wilkinson's mills, and payments amounting to £69 were made. In

November, 1897, a special meeting of members voted a sum of £100 as

a donation to a local fund to aid people affected by an engineers'

lockout, the payment to be spread over five weeks. The society

was also asked to quote for a tea to be provided for the children of

the engineers; 4d. per head was quoted, and the use of the hall

granted for the 8th January, 1898. The Amalgamated Society of

Engineers' Ashton, Stalybridge, Hyde and District Lockout Committee

wrote tendering hearty thanks for the manner in which the children

had been entertained, and for what they described as not the first

generous action on the part of the society. Another appeal not

made in vain was on behalf of a West of Ireland distress fund,

raised locally, a contribution of £25 being made by a special

meeting of members held 27th April, 1898. The small savings

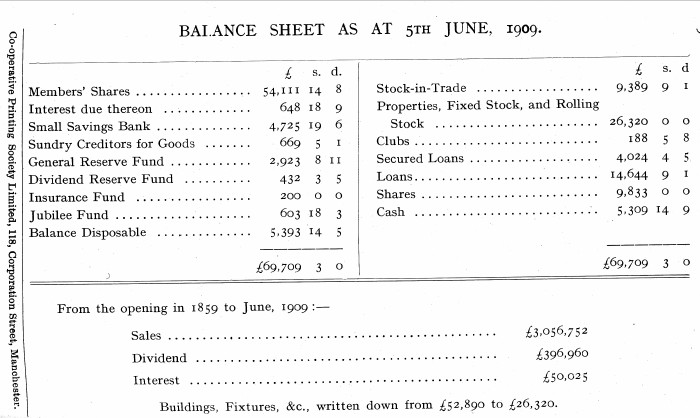

bank was established in March, 1898. It has been an incentive

to thrift on the part of the children of members. There is now

£4,725 to the credit of depositors, a very large proportion of whom

are children.

On Saturday, 22nd April, 1899, there was opened a three days'

exhibition of articles produced by the Co-operative Wholesale and

other productive societies, and the Castle Hall branch store was

opened. His Worship the Mayor, Alderman Norman, performed the

ceremony of opening the exhibition, and Mr. G. R. Patten, president

of the society, discharged the function at the new premises.

At the exhibition there was a large attendance, the

assembly-room of the Town Hall being crowded. Mr. Patten

presided, and was supported by the Mayor; Messrs. T. Knott, S.

Knight, J. T. Bate, J. Allen, W. H. Kenyon, W. Wardle, E. P. Owens,

and J. Heap, committee; J. H. Hinchliffe, secretary; J. B. Mason,

manager; W. Thompson, treasurer; S. Hall and D. Holt, auditors; John

Fawley, A. Hopwood, T. Beard; Geo. Rowbottom, architect of the new

premises; Mr. F. Thompson, of Messrs. Buckley, Miller, and Thompson,

solicitors to the society; Mr. W. Lander, of the Co-operative

Wholesale Society; and delegates from neighbouring societies. |

|

The Chairman said it gave him great pleasure to preside on

that occasion, and to know that every article displayed in the hall

had been produced under good conditions of labour, with a fair day's

wages for a fair day's work. Co-operative production was

cutting away one of the greatest curses of the country by its effect

upon the sweating dens, where people were working early and late in

insanitary workshops for a mere pittance. In doing that the

co-operative system had rendered an important service to the public,

and such an exhibition as they saw before them would in its results

be of lasting importance. He would quote the words of Mr.

Holyoake, who said: "Co-operation supplements political economy by

organising the distribution of wealth. It touches no man's

fortune, it seeks no plunder, it causes no disturbance in society;

it gives no trouble to statesmen, it enters into no secret

associations, it contemplates no violence, it subverts no order, it

envies no dignity; it asks no favour, it keeps no terms with the

idle, and it breaks no faith with the industrious; it means

self-help, self-dependence, and such share of the common competence

as labour shall earn, or thought can win, and these it intends to

have." In the co-operative movement there were distributive

and productive departments. The latter had not the advantage

of the early start which the former had enjoyed, but to prove that

there had been a great advance made he would give them some figures

showing the progress recorded from 1883. In that year there

were 15 societies, in 1893 there were 108, and in 1898 no fewer than

169. The sales of the 15 societies in 1883 amounted to

£160,751, in 1893 the sales of the 108 were £1,292,668, and in 1897

the results of the 169 societies' operations came to £2,713,436.

The capital of the societies in 1883 was £103,436, in 1893 £639,884,

and in 1897 no less than £1,180,906. The figures he had given

showed an increase of about fourteen fold in the same number of

years.

He then introduced Alderman Norman, who had a cordial

reception. He said he was pleased to see such a large

gathering at the inauguration of the first exhibition of the

Stalybridge Co-operative Society. It was a proof that the

efforts of the committee were appreciated by the members. He

had no doubt many members of the society and many of the public

would attend to view the numerous articles so tastefully displayed.

He looked upon it as his duty as Mayor of the borough to assist in

any movement for the benefit of the people of the town. He had

been very cosmopolitan. It had not mattered to him what class

of politics or what sect, if the idea had been good and for the

benefit of the inhabitants he had joined with it. The

co-operative society of Stalybridge was strong and powerful, and the

report before him showed that they were very successful. The

sales during the past twelve months had been £84,705, and the

carrying on of business with such a turnover meant industry and

effort on the part of the committee for a nominal payment. Not

only had the turnover been large, but so had the profit £13,000 on

£84,000. If such progress could be kept up he should expect,

in the course of a few years, that the society would do a little

more in aid of the charitable institutions of the town. The

membership of the society was over 3,000, and represented some

15,000 persons, a large proportion of the inhabitants of the town.

The co-operative movement nowadays touched almost every branch of

trade, and he understood the opening of the Castle Hall Branch would

make the sixth connected with the Stalybridge Society. Amongst

the departments of the society he noticed they had one which dealt

with the building or buying of houses by the members. The

Government was bringing in a Bill by which municipal authorities

would be able to advance money to any person on suitable security

for the purchase or erection of his own dwelling. It might

tell somewhat against co-operative societies, but personally he did

not care which way it went, so long as he could see people living in

their own houses, because he believed that the more people lived in

their own houses the better they would know their responsibilities,

and the better it would be for the sanitary and moral arrangements

of the town. (Hear, hear.) He had great pleasure in

declaring the exhibition open. (Applause.)

Mr. J. T. Bate proposed a vote of thanks to Alderman Norman.

During the past 15 months, he said, the building contracts let by

the society amounted to about £10,000, all to Stalybridge

contractors. The society employed 86 persons, and paid wages

which averaged £1. 1s. per week all round, a sum which he thought

was very good when they considered the number of young persons

employed.

Mr. W. Wardle seconded, and Mr. W. Lander supported the

motion, both gentlemen speaking of the benefits conferred by the

co-operative societies of the country. On the proposition of

Mr. J. Fawley, seconded by Mr. Hopwood, thanks were given to Mr.

Patten for his services in the chair. During the three days

the exhibition was open there was an excellent programme of music by

an orchestral band, conducted by Mr. T. Cheetham, with Mr. J. Hulme

as leader.

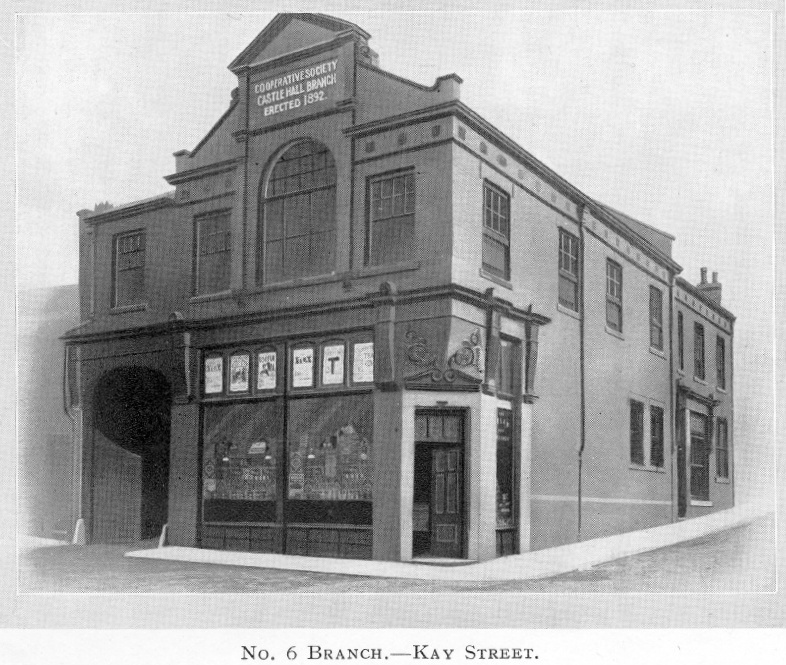

The Stalybridge Reporter of April 29th, 1899, had the

following comments:

The Stalybridge Co-operative Society is to be

complimented upon the success which attended the exhibition of

co-operative productions, and upon the magnificent stores erected in

Kay Street. During the time the exhibition was open some

thousands of people visited it. After the opening of the

exhibition on Saturday, the officials of the society, together with

a number of members, proceeded to Kay Street for the opening of the

Castle Hall branch store. Mr. John Heap called upon Mr. Geo.

Rowbottom, the architect, who presented a gold key to Mr. G. R.

Patten, president. Mr. Patten complimented Mr. Rowbottom and

the contractors (Messrs. Shuttleworth Brothers) for the admirable

manner in which they had carried out the work. He returned

thanks for the gift, and observed that they had erected those new

premises on account of the steady progress the society had made

during the past four years. The inscription on the key was as

follows:"Presented to George Patten, Esq., of Heyrod, at the

opening of the Castle Hall Branch of the Stalybridge Industrial

Co-operative Society Ltd., George Rowbottom, Esq., architect, April,

1899." The premises were then inspected, and afterwards tea

was served in the society's hall.

The following description was given:

The new building consists of a hue grocer's shop,

with a flour store behind, a butcher's shop, and two dwelling

houses. The grocers shop is entered at the angle of Brierley

Street and Kay Street, and is fitted up with all the latest

improvements. The whole of the interior of the butcher's shop

is faced with opalite treated in various shades of colour, and

presents a beautiful appearance. The building is arranged to

suit the special needs of the site. The design is treated in a

free, classical manner, the walls being laced with Accrington

bricks, with dressings of polished Yorkshire stone. The work

was carried out by Messrs. Shuttleworth Brothers, the

sub-contractors being Messrs. Myles and Warner (brickwork), Mr. T.

G. Shaw (joiners' work), Messrs. Pickles Brothers (slating), Messrs.

W. H. Whitehead and Sons (plumbing and painting), and Messrs. Mellor

and Walker (plastering).

The same year (1899) the telephone was installed, the society

becoming a subscriber to the National Telephone Company, and having

all the branches and Central put in communication with each other by

means of private lines.

Efforts in the direction of an education department had not

achieved so much as those of some other societies. Newsrooms

had been opened, and after a brief spell closed, and little or

nothing had been attempted in the formation of classes such as are

carried on successfully by many societies. In 1899 a small

grant for educational purposes was used in another manner, a sum of

£25 being handed over to the Stalybridge Technical Instruction

Committee. To form a connecting link between elementary and

continuation classes there had been offered free admission to the

technical school to a certain number of children attending day and

evening classes, limited to grant-earning classes. The

society's grant was used to extend to commercial classes what was

already done for the others, the subjects specially named for

encouragement being cotton-spinning, shorthand, book-keeping,

typewriting, dressmaking, millinery, and cookery. The grant

has been repeated yearly. The principal of the school reported

in 1906 that by means of the grant 104 free scholarships had been

awarded to students who had acquitted themselves well in the various

examinations, and, in addition to that, 93 scholarships had been

granted to pupils who were entering the school for the first time.

Any pupil, he said, of any promise, who worked and had the necessary

ability, could by means of the grant obtain free admission and pass

through the various stages of the subject free of cost. The

scholarships were thoroughly appreciated by the students, and had an

excellent effect on their attention and application to their

studies.

A fund to aid the dependents of army reservists who had gone

to the front in the South African War was raised in the town in

1899. In November the members voted a sum of £50. In

addition to this there was granted to the wife, children, or

dependents of each member who had been called up for active service

goods to the value of 10s. per week, except where they were

otherwise provided for. Members of the committee met to

receive applications. From November, 1899, to September

quarter, 1902, when the last of the reservists returned from the

front, the dependents of nine men received £376, and there was

evidence from the men themselves that great good had been done by

the timely help. Mr. W. Wardle was a member of the War Fund

Committee for the town.

In January, 1901, the members passed a contribution of £5 to

the volunteers now territorial force prize fund, a contribution

which has been repeated yearly to date.

In their report of June, 1900, the committee expressed their

deep regret at the death, which occurred on the 2nd May, of Mr. John

Heap. Mr. Heap had been officially connected with the society

for the long period of 27 years, and was a member of the Board until

his death.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIV.

1900 TO 1907 CHEETHAM

HILL ROAD BRANCH

"CLIMAX" CHECK SYSTEM

WORK FOR TRADE UNIONISTS

ONLY SPECTACLES, &c, AGENCY

CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL

SOCIETY FOR PREVENTION OF

CRUELTY TO CHILDREN

CHILDREN'S GALA

MILLINERY IN MELBOURNE

STREET SIX

FIGURES OF SALES

INCREASED PRODUCTION

DEATH OF MR. S. KNIGHT

ABATTOIR MOUNT

PLEASANT BRANCH EXTENDED

DEFENCE FUND

BOROUGH EDUCATION COMMITTEE

EXCURSION TO LONDON

DEATH OF MR. WM.

HALL COTTON SHORTAGE

AND DECREASE IN TURNOVER

COTTON GROWING ASSOCIATION

CONVALESCENT HOMES

ANOTHER LOCAL DISTRESS

FUND DELEGATES'

APPOINTMENT OFFICE OF

TREASURER ABOLISHED

SUNDRIES SOCIETY DIRECTORATE

PRINTING SOCIETY SHARES

STRATFORD EXCURSION

CORN MILLS TAKEN OVER BY

THE WHOLESALE SOCIETY

PREMIER MILLS

ELECTRIC MOTORS

KNITTING MACHINERY

MR. J. T. BATE RESIGNS

PRESIDENT A MAGISTRATE

BOOK-KEEPING CLASS

MISS FIRTH, MILLINER

MISS HOLT, DRESSMAKER

INTEREST ON SHARES.

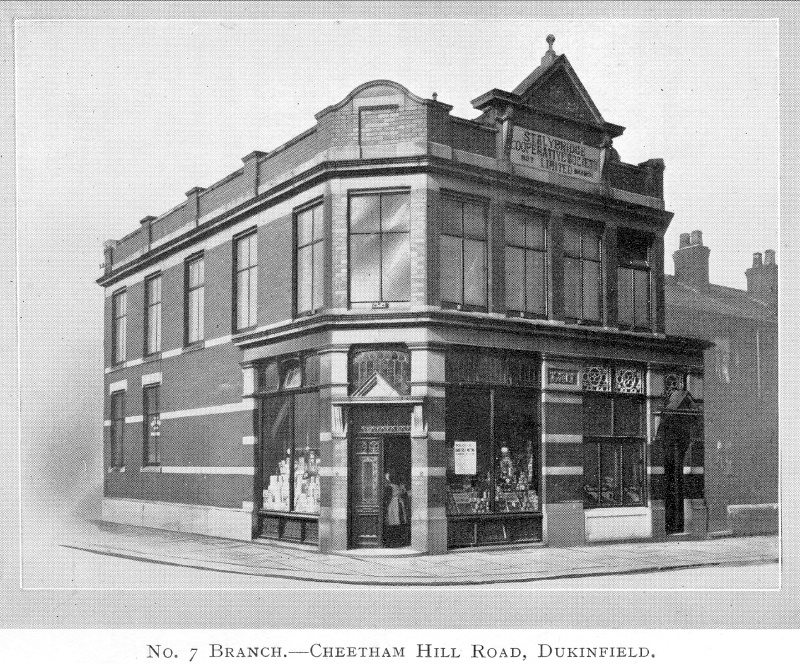

CHEETHAM Hill

Road Branch, No. 7, was opened 1900. Fully eight years before

there had been a proposal to open a branch store in or near Lodge

Lane, Dukinfield, the committee agreeing to recommend such a scheme.

It did not go forward, however, until October, 1898, when the

members decided that it should be opened in Cheetham Hill Road.

In May, 1899, the tender of Messrs. Saxon Brothers was accepted, and

soon work was commenced, with Mr. Geo. Rowbottom as architect.

The branch was opened February 19th, 1900, with Mr. W. Broadbent as

branch manager. During the three weeks to the end of March

quarter the sales were £213, and the first complete quarter (June,

1900) they were £1,013.

In January, 1901, a deputation, which included the writer,

visited Farnworth, where the "Climax" check system, as at present in

operation at Stalybridge, was originated. A report to a

special meeting of members was given on February 6th; the system was

adopted, and on the 11th March was introduced in the shops. In

September the same year Mr. Albert Shaw was appointed to take charge

of the check office. He was a man who knew exactly what was

required to ensure the successful operation of the system, and he is

still conducting very efficiently that important department of the

office. |

|

A resolution of the committee of the 14th June, 1901, will be

appreciated by all trade-unionists. It was to the effect that

no work would in future be given to any tradesman who did not comply

with the rules and regulations of his trade society.

In June quarter, 1901, the society commenced to act as agent

to Messrs. Cowan and Sons, the eminent optologists, of Manchester.

Since that date many members have had the advantage of the best

possible advice from Messrs. Cowan in the selection of spectacles,

eyeglasses, artificial eyes, &c.

The same year, at the October quarterly meeting, the present

annual subscription of £10 to the Manchester Royal Infirmary was

passed.

A year later the annual subscription of £2 to the Manchester

Children's Hospital at Pendlebury was fixed.

A donation of £5 to the National Society for the Prevention

of Cruelty to Children had been made yearly for some eight years,

and another, similar in amount, to the Stalybridge Sick Nursing

Society since 1899.

The children's gala was inaugurated in 1901, the first being

held August 24th.

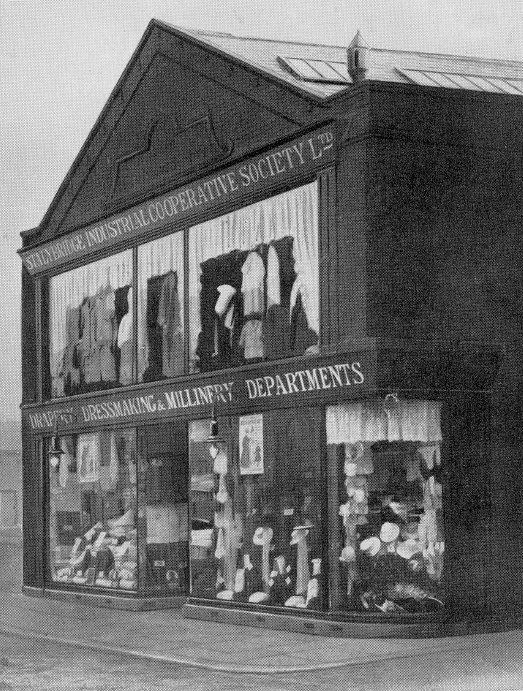

The removal of tailoring to a front position in Melbourne

Street six years before had been so advantageous to that department

that it was thought when tailoring was removed to the larger

premises in Grosvenor Square the shop vacated could be utilised to

good purpose for millinery. Miss Bruce was engaged in August,

1901, and on the 3rd October millinery was taken into Melbourne

Street under her management. A very smart millinery business

was done there. There were disadvantages, however, in drapery

and millinery being so far apart, and some four years later the

drapery premises were partly reconstructed internally, and millinery

was again removed to its present position in Back Grosvenor Street.

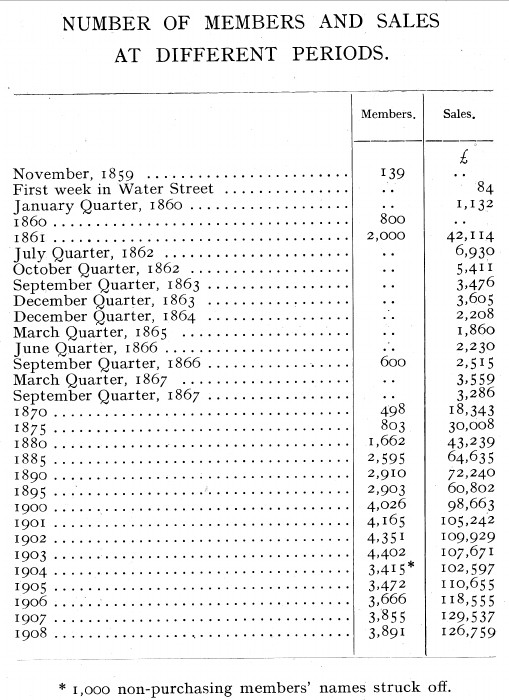

Six figures of sales were reached for the first time in 1901,

the total being £105,242, £6,947 over that of 1900 and the highest

then attained. The dividend to members was £15,591, and

interest on their shares £2,024. One hundred and three persons

were employed. Seven years before the wages paid to productive

workers in millinery, dressmaking, tailoring, and boot-making

totalled £600; in 1901 the amount was £1,539, an increase of 156 per

cent.

The committee referred with sorrow in their report of

September, 1902, to the death of Mr. Samuel Knight, which occurred

on the 16th September. For thirteen years at least they had

known Mr. Knight as an earnest co-operator and a conscientious man,

his connection with the Board dating back to 1889.

In this year a small building off Robinson Street, rented for

the purposes of an abattoir, was given up, and the existing

commodious premises at the rear of Buckley Street property were

built by Messrs. W. Storrs, Sons and Co.

Mount Pleasant Branch was extended backward by Messrs.

Shuttleworth Brothers.

A defence fund, for the purpose of counteracting the

despicable boycotting tactics of certain traders in St. Helens and

other towns was raised at this time by the Co-operative Union.

A special meeting of members held Wednesday, October 8th, 1902,

unanimously voted a sum of £100. It was suggested that for the

movement there was nothing to fear, the boycott having the effect

eventually of increasing the membership and turnover of the

societies attacked; but that there should be a contribution to the

fund for the sake of individual co-operators who had been dismissed

from their employment and in other ways victimised. The

directors of the Co-operative Wholesale Society had proposed to

guarantee a sum of £50,000. The proposal was approved by the

societies, and the fund of £100,000 desired by the Union was very

soon guaranteed. There is still a defence committee of the

Union prepared to take action if required. Four calls upon the

societies have been made, in proportion to the amounts guaranteed,

amounting together to 6 per cent of the fund. Thus Stalybridge

Society has been called upon for £6 only, and there is still

available, nearly seven years after the raising of the fund, a sum

of £94,000.

In March, 1903, Mr. J. B. Mason, general manager to the

society, was nominated as the society's representative on the

Education Committee of the borough, a position he still holds.

An excursion to London, joint with Ashton Society, was run

this year, leaving Stalybridge on Whit-Friday night and returning

Whit-Saturday night. The inclusive charge for fare, breakfast,

tea, and some six hours' driving was 17s. 6d. each person.

Breakfast was served by the Co-operative Wholesale Society's London

Branch, and the arrangements for rail journey, tea, and drive were

made by Messrs. Dean and Dawson. Stalybridge sent 110

passengers; including those from Ashton, there were 300.

In August, 1903, the committee had to regret the loss by

death of another colleague, Mr. William Hall, who died on the 3rd.

He was a man, they said, of long experience in the movement, having

been elected to the Board so long before as 1876.

The shortage of American cotton was responsible for a

decrease in the turnover, the first for nine years, in 1903.

The total sales were £107,671, compared with £100,030 in 1902.

A hope was expressed that the great work of the British Cotton

Growing Association would meet with success. A contribution of

£50 to the funds of the association was passed by the members at

their January, 1904, meeting.

The North-Western Co-operative Convalescent Homes Association

was registered about this time, and in January, 1904, the members

decided to apply for 85 £1 shares. The shares are not

withdrawable, and do not bear interest. There are two homes,

one at Blackpool and one at Otley in Yorkshire. A good number

of Stalybridge members have had residence at the homes as

convalescents and visitors, and all who have reported have testified

to the excellence of the arrangements. Another convalescent

home which many members have utilised to advantage is owned by the

Co-operative Wholesale Society and situated at Roden, near

Shrewsbury.

At the beginning of 1904 another fund for the relief of

distress in the borough was raised, on this occasion by the Mayor.

The committee made a grant of £10. On April 6th the members

confirmed the action and voted a further sum of £40, to be paid as

the committee thought fit. It appears that the society was not

called upon for the full amount, the fund being closed when £30 had

been paid.

The annual meeting, April, 1904, resolved that delegates to meetings

of societies or companies of which the society was a shareholder be

appointed partly by the committee and partly by the members at

annual meetings, and that they report to quarterly meetings.

The delegates under this arrangement are now Messrs. James Harrison,

Geo. Heathcote, A. Longden (one of the joint jubilee secretaries),

and F. Nash.

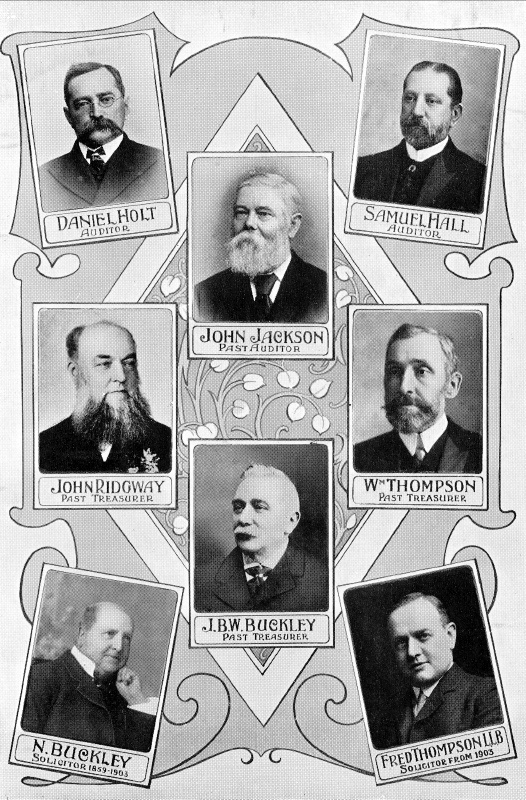

Until 1905 there had been elected as treasurer, with the

exception of about one year, 1893 to 1894, one not on the permanent

staff. Mr. John Ridgway has been referred to as the holder of

the office. He was followed by Mr. J. B. W. Buckley in 1885,

then came Mr. Wm. Backhurst in 1888, and the writer, who was on the

staff, from 1893 to 1894, and who relinquished the office on his

appointment to the secretaryship. Mr. Wm. Thompson followed in

1894. The duties were very conscientiously performed by Mr.

Thompson for some eleven years, until April, 1905, when he retired,

and it was arranged that the work should in future be undertaken by

one of the office staff. Mr. A. E. Jackson, then chief clerk,

was the first to take office under the new arrangement, and he held

it until he left the society's service in 1907, when he was

appointed secretary to Fleetwood Society. He was succeeded by

Mr. Edwin Wright, the present cashier.

The Co-operative Sundries Manufacturing Society Limited, of

Droylsden, elected Mr. John Fawley, our present chairman, at a

meeting of shareholders held March, 1905, to the seat he still holds

on the board of directors.

The same quarter 100 £1 shares of the Co-operative Printing

Society Limited were taken up.

On Whit-Saturday, June 17th, 1905, Ashton, Stalybridge, and

Hyde societies ran another joint excursion, conducted by Messrs.

Dean and Dawson. On this occasion it was to Stratford-on-Avon,

the birthplace of Shakespeare, and the arrangements included a drive

to Warwick and Leamington, with breakfast at Stratford, and tea

after the drive. The inclusive charge for fare, drive,

breakfast, and tea was 11s. 3d. There were 78 passengers from

Stalybridge, 43 from Hyde, and 150 from Ashton.

The Star (Oldham) and Rochdale corn mills were taken over by

the Co-operative Wholesale Society in 1906. There was a small

loss on realisation of the Rochdale shares, but the Star Mill had

been so prosperous that there was a substantial profit on the whole.

The amount at credit of our share account in the books of the

Rochdale Corn Mill Society was £412, and the shares realised £364;

the Star Corn Millers' Society had £503 to our credit as shares,

which brought in £909. Thus there was a net profit on the two

lots of shares of £358, which was added to the reserve fund.

In April, 1906, the members discussed a proposal to take up shares

of the Premier Mills Limited. Three years before there had

been a suggestion that shares of the Victor Mill Limited should be

applied for, but it was negatived. Of the Premier, 1,000 £5

shares were taken up, and the society nominated Mr. Thomas Knott for

the board of directors of the company. He remained on the

directorate until his death in October, 1908, when he was succeeded

by Mr. R. Firth, who is still in office.

Electric motors for hoisting, coffee-grinding, &c., and

electric irons for dressmakers' use, were introduced in 1906.

The latter were not a great success, and their use was discontinued

in 1909, but the motors are still in use. Current is taken,

not from the society's dynamo, but from the Tramways Board.

Another development in a small way in 1906 was the

introduction of a Harrison knitting machine in drapery.

At the annual meeting in April, 1906, Mr. J. T. Bate resigned

his seat on the Board in consequence of his appointment as manager

of the Roy Mill, Royton. The committee expressed their regret

at the loss of his services, and said their hearty good wishes would

go with him.

In November the same year Mr. William Wardle, the society's

president, was appointed to the magisterial bench of the borough.

A book-keeping class, open to the staffs of all departments,

was commenced in earnest in October, 1906, the committee granting

the use of the hall. Mr. A. E. Jackson was teacher, and he had

students of both sexes. At the end of the term an examination

paper was set by the writer, and several students acquitted

themselves well. They showed their appreciation of Mr.

Jackson's services by a presentation.

Millinery passed into the hands of its present head in 1906.

Miss Bruce was followed by Miss Hollinshead, and on the retirement

of the latter in 1906, Miss Firth, who still controls the department

successfully, was appointed to take charge of the workroom, with

Miss R. Roberts responsible for the showroom and sales.

Dressmaking, too, passed under new management the same year.

Miss Lawton was succeeded by Miss Leach in 1902; then followed Miss

Schofield, March, 1904; Miss Wood, March, 1906; and finally the

indefatigable Miss S. Holt, who is still in charge.

The present rule as to interest on share capital was passed

by the members January 2nd, 1907. The matter had been many

times discussed. As far back as April, 1885, Mr. James

Bamforth moved that the rate of interest be reduced from 5 to 4 per

cent. In July, 1886, the minimum quarter's trade of a member

to secure the full rate of interest, still 5 per cent, was fixed at

£2, the rate to be 2½ per cent

to members not complying with the rule as to trade. In

October, 1893, there was a motion to the effect that a member

trading to the extent of £2 a quarter be paid 5 per cent on £10, £3

trade 5 per cent on £15, and so on; and in October, 1894, there was

an effort to raise the minimum trade to £4. The committee had

before the members in April, 1905, a recommendation that the rate of

interest on all shares be reduced to four and one sixth per cent,

and that a member's quarter's trade to entitle him to that rate be

raised to £4. The members accepted that part of the resolution

which referred to the raising of the minimum trade, but the rate of

interest payable to those who did the necessary trade remained

through all those years at what it is in 1909, 5 per cent. It

was thought by many members that the provision for £4 minimum trade

was a hardship, and in January, 1907, a special meeting of members

accepted Mr. John Fernley's proposal to the effect that £2 trade a

quarter should entitle a member to 5 per cent up to £20 shares, £3

trade 5 per cent up to £30, £4 trade 5 per cent up to £40.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XV.

1907 TO 1909 UNION

NEW HEADQUARTERS

WHAT THE UNION HAS DONE

SUNDRIES SOCIETY NEW

WORKS A BANKING

ACCOUNT WITH THE WHOLESALE

SOCIETY ADDING BY

MACHINERY "OUR

CIRCLE" DEATH

OF MR. JAMES BAILEY

SALES 1907, £120,537 COMMITTEE

ELECTIONS CANVASSING

CO-OPERATIVE INSURANCE

SOCIETY ASHTON

DISTRICT INFIRMARY

DEATH OF MR. THOMAS

KNOTT CASTLE

HALL MILL BOUGHT

STORY OF DRAPERY CONTINUED

MR. T. FAULKNER, DRAPERY

MANAGER STOCK

BRANCH, NO. 8

SUNDRIES SOCIETY REFERRED

TO £100 SHARES ALLOTTED

COLLECTIVE ASSURANCE

JUBILEE COMMITTEE.

THE Co-operative

Union had under consideration a scheme for new headquarters, and

there was an appeal to the societies for a sum of £20,000 to secure

a site and erect a building to he styled "Holyoake House," near

those of the Co-operative Wholesale Society in Manchester. It

was suggested that societies should contribute at the rate of 3d.

per member. Stalybridge Society's contribution at that rate

was £46, and at the annual meeting held 3rd April, 1907, the members

readily passed it. A brief account of what the Union is and

what it has done may be useful here. The Co-operative Union is an

institution charged with the duty of keeping alive and diffusing a

knowledge of the principles which form the life of the co-operative

movement, and giving to its active members, by advice and

instruction literary, legal, or commercial the help they may

require. Most of the legal advantages enjoyed by co-operators have

been attained by the Union. Amongst those advantages are (1) the

right of the societies of holding in their own names lands and

buildings, and property generally, and of suing and being sued in

their own names instead of being driven to the employment of

trustees; (2) the power to hold £200 instead of £100 by individual

members; (3) the limitation of the liability of members; (4) the

exemption of societies from charge to income tax on profits under

the condition that the number of their shares shall not be limited;

(5) the extension of the power of members to bequeath shares, loans,

and deposits up to £100 by nomination, without the formality of a

will or the necessity of appointing executors.

The Co-operative Sundries Society commenced the erection of new

works at Droylsden about this time, and on the 2nd October, 1907,

our members accepted a recommendation of the committee that 200

additional £1 shares of the Sundries Society be taken up, and that a

further sum of £200 be placed as a loan. The new building was opened

February 13th, 1909, and we were represented at the opening

ceremony.

As early as 1880, and again in 1889, it had been suggested that a

banking account with the Co-operative Wholesale Society should be

opened. The suggestion was not then adopted. On the 17th June, 1907,

however, it was arranged that such an account should be opened, and

from a date shortly after that all the society's banking business

has been done through the Wholesale Society.

A Burroughs adding machine was bought in June, 1907, and since that

date members' purchases have been added by machinery. It is used for

many other purposes; it saves an immense amount of time and

brain-fag; it never makes a mistake; and it seems now quite

indispensable.

The same year the first issue of the admirable children's journal,

"Our Circle" appeared. A good order was given, and copies were

placed for sale in all the shops.

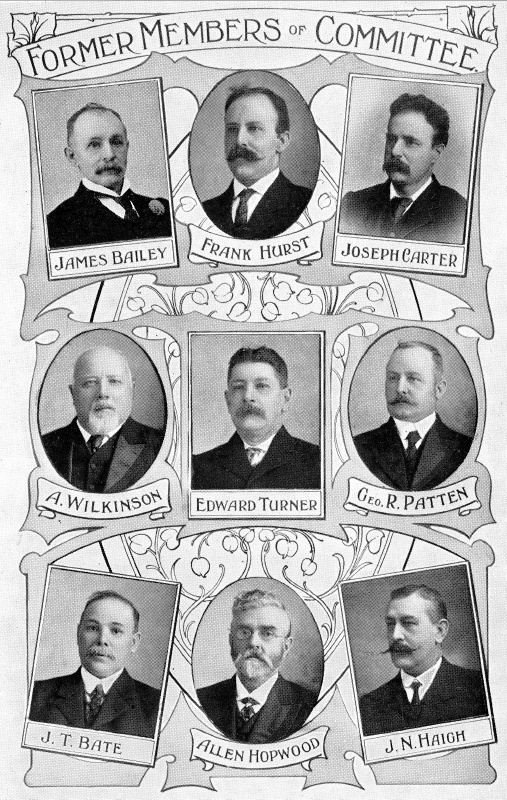

Mr. James Bailey, of Millbrook, died in 1907. He had been on the

Board so recently as July, 1906. A letter of condolence was sent to

the family.

The year 1907 was the best the society had experienced. The sales

were £129,537, an increase of £10,982 on 1906, the previous highest. The dividend to members was £19,232, and the interest on their

shares £2,454.

The subject of committee elections was brought forward at members'

meetings time after time. In April, 1884, there was a resolution to

the effect that the committee retire one quarterly, not three

annually as hitherto. Two years later Mr. Wm. Brown moved "That

retiring members be not eligible for re-election until they have

been off the Board four quarters." The motion was negatived. In

April, 1886, Mr. T. Kenworthy proposed "That the members of

Millbrook should have the power to nominate one or more members to

represent their district." This carried, and Mr. Thomas Wood, of

Millbrook, was elected at the same meeting. In January, 1893, Mr. M. Naden was successful with a motion in favour of standing down, and

in July, 1895, there was an unsuccessful effort to reverse that

decision. A motion in October, 1897 "That Millbrook and Heyrod

members each have a representative, that in each case he be elected

by his branch only, and that the members of those two branches do

not vote in any other election" was rejected by 82 votes to 27. In

October, 1898, and January, 1904, there were efforts to revert to

the system of yearly elections, but they were defeated, and

quarterly elections took place until 1908, when Mr. Allen Hopwood's

proposal of the present rule was accepted. This provides for the

election and retirement of three members half-yearly, each to serve

eighteen months, to be eligible for re-election for a second term of

eighteen months, and after that to stand down for twelve months;

Millbrook and Heyrod branches to have jointly one representative.

There were efforts, too, to put a stop to canvassing, by making it a

disqualification, in April, 1900, January, 1907, and January, 1909. On the last of the three dates Mr. A. Hopwood's motion on the

subject was passed unanimously.

The Co-operative Insurance Society Limited had new offices in

Corporation Street, Manchester, erected about this time, and in

April, 1908, Mr. J. Fawley and Mr. A. E. Dickin represented us at

the opening. At a very early stage the committee had given their

support to the Co-operative Insurance Company as it was formerly

styled. There was a resolution December 31st, 1866 "That the

society join the conference to consider the mutual insurance

proposition." Probably the conference here referred to would be one

of the early steps toward the formation of the Insurance Society,

which was registered in 1867. In November, 1867, it was decided that

the society become a member of the company; there was a first call

of 1s. per share in April, 1868, and further calls amounting to 4s.

per share, the present amount per share called-up. Our holding was

increased, first to 50, and in 1881 to 65 shares, at which it still

stands. In February, 1869, the society's buildings and stock were

insured with the company for £1,500. From that the business we have

given to the Insurance Society has increased until the amount

insured is many thousands of pounds in fire, fidelity, and other

departments, including the insurance against fire of all the branch

stores and a good proportion of the Central premises risk, the

latter being partly reinsured in other fire offices. A member of the

society, Mr. Samuel Hibbert, was acting as agent to the insurance

company in 1889. Afterwards there was a long interval during which

there was no agent for Stalybridge. In 1908 Mr. James Harrison, of

Millbrook, was appointed an agent.

The Ashton District Infirmary has had the society's support since

1870, a donation of £5 being passed by the annual meeting of May

2nd. Later an annual subscription of five guineas was paid; it was

increased in April, 1886, to ten guineas; in July, 1908, it was

again doubled, the present subscription of twenty guineas per annum

being fixed.

On the 2nd October, 1908, the committee passed a vote of condolence

with the family of the late Thomas Knott, who had died suddenly the

day before. A similar vote was passed by the quarterly meeting of

members, October 7th.

The old Castle Hall Mill was offered for sale to the society in

August, 1902. The offer was not accepted. In 1908 it was again

offered; on the 4th May the conveyance was sealed and the mill

became the property of the society. At the time of writing there is

no definite scheme, but it is thought that the site may at some

future time be used for an extension to the Central premises.

The story of the drapery department to 1894 has been told. In that

year Mr. J. T. Evans became drapery manager; he remained until 1905. Mr. Evans was succeeded by Mr. A. V. Cartlidge, who came to us from

a Yorkshire society in 1902. Mr. Cartlidge was very energetic and

the department flourished under his care. He was drapery manager

from June, 1905, to June, 1908. The sales for a year immediately

preceding his taking charge were £8,378; during the last year of his

management they were £12,518. He left with good credentials to take

the management of drapery for Peterborough Society. Mr. T. Faulkner,

who was appointed first counterman when Mr. Cartlidge took the

management, and who became drapery manager on the resignation of the

latter, has proved a worthy successor.

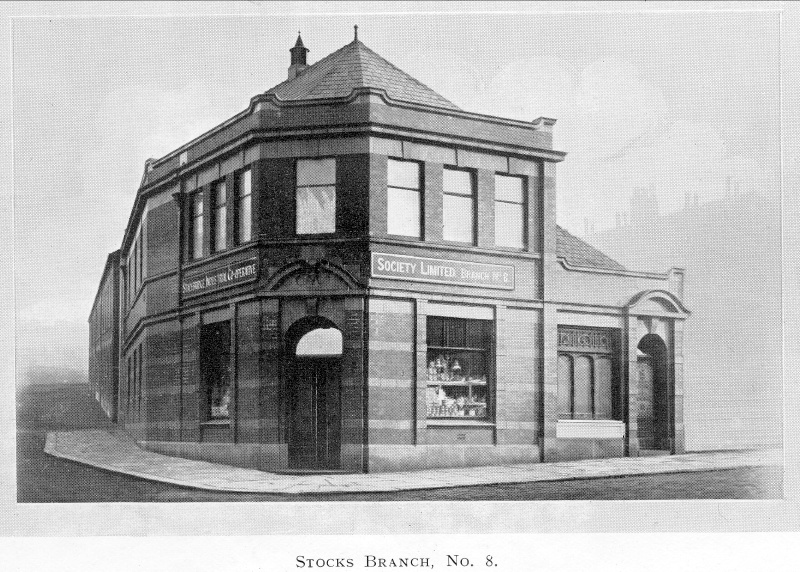

The annual meeting of members held 1st April, 1908, adopted the

recommendation of the committee that a branch store, No. 8, for

grocery and butchering, be erected in Taylor Street, Stocks Lane,

Stalybridge. A plot of land fronting Taylor Street and French Street

on the Stamford Estate was taken. Messrs. Saxon Brothers and Co.

Limited undertook the builders' work and Mr. Arthur Mee the

plumbers, with Mr. Geo. Rowbottom as architect. The branch was

opened on Saturday, December 5th, 1908, under the management of Mr.

Garnet Guthrie. There were present at the opening Mr. John Fawley,

president; Messrs. R. Hanson, W. Shaw, T. W. Barnett, Hugh Lawton,

A. Cooper, R. Stubbs, E. P. Owens, and A. E. Dickin, committee; Mr.

J. H. Hinchliffe, secretary; Mr. J. B. Mason, manager; Mr. D. Holt,

auditor; Mr. A. Turner,

of the committee of Ashton-under-Lyne Society; Mr. Geo. Backhurst,

manager of the Co-operative Sundries Society; Messrs. J. Saxon and

O. Andrew, of Saxon Bros. and Co. Limited, builders of the branch;

Mr. A. Mee, plumbing contractor; Mr. Geo. Rowbottom, architect; and

others. Mr. Barnett called upon Mr. Rowbottom, who said the new

store had been constructed in such a manner as to ensure cleanliness

and to avoid interference with business whilst any necessary

decoration was going on. He trusted it would do all the society

expected, and more, and that further extension would soon be

necessary. (Hear, hear.) He had very great pleasure in presenting to Mr. Fawley the key. Mr. Fawley thanked Mr. Barnett for his

introduction, and Mr. Rowbottom for his handsome present the key.

It was at the request, he said, of a large number of members in that

district that the committee decided to build that branch. It was in

a populous district and a growing one, and he believed it would

prove one of the best of the branches. Speaking as he was to

co-operators he need no more than mention one or two of the

advantages to be derived by members of a society. They participated

quarterly in proportion to their purchases, in the dividend, which

would otherwise be profit going to one or a few. They knew how

useful that dividend was. For one who was bringing up a young family

it would probably clothe the children, or provide a trip to the

seaside; or if it were left in as share capital at interest it would

be there for any emergency such as sickness or bad trade, or

disputes such as had just been experienced in the cotton trade. He

had no doubt many members had felt recently the advantage of having

such capital. He was connected with a productive concern at Droylsden, the Co-operative Sundries Society. The workers there were

employed under the most favourable conditions, and they participated

half-yearly in a bonus to labour. Everyone who worked for the

Sundries Society received 1s. 6d. in the £ bonus on his wages. No

young man of 21 or over, whatever his occupation, had less than 24s.

a week, and with bonus that was increased to 25s. 9d. a week. His

hearers would find in their new shop that afternoon a fair show of

the goods made at Droylsden and at the productive works of their

great Co-operative Wholesale Society. The Stalybridge Society had

been very successful in other parts; he believed Stocks Lane people

would prove that they were good co-operators and would make that

enterprise a huge success. He had pleasure in opening No. 8 Branch

of the Stalybridge Co-operative Society. Mr. Fawley then unlocked

the door and the shop was at once crowded by purchasing members. |

|

Additional withdrawable shares were allotted, commencing April,

1909, making the maximum holding per member £100. It appears that in

1881 the society went to the limit imposed by Act of Parliament, as

much as £200 shares being allotted to individual members. In April

of that year there was a proposal to reduce it to £100, and in the

following year notice was given that shares over £100 held by any

one member would cease to bear interest from the 1st April, 1882. There was a resolution, January, 1885, further reducing it to £50,

but this was rescinded a year later. The limit became £90 in April,

1886, and later it was lowered by £10 at a time, until in February,

1890, it was £40. That limit was retained until the April, 1909,

meeting carried unanimously Mr. A. E. Dickin's motion that it be

raised to £100, the maximum under the rules then in force, the rate

of interest to remain at 5 per cent up to £40, and to be 3 per cent

on the remaining £60.

The Co-operative Insurance Society's Collective Life Assurance

scheme was referred to at the same meeting. Nearly five years before

we entertained the conference of the Oldham District, North-Western

Section of the Co-operative Union, and "Collective Assurance" was

the subject, Mr. James Odgers, secretary to the Insurance Society,

reading a paper. The scheme was not then taken up in Stalybridge. In

other places it made headway until in April, 1909, 118 societies had

it in operation. Then the members accepted Mr. James Hibbert's

motion requesting the committee to obtain further information as to

the scheme, with a view to its being adopted. Under the scheme, if

it is adopted, the lives of all members will be assured by one

policy, the premium of 1d. per £1 of sales being paid by the

society. The experience so far is that the premium is reduced

eventually by surpluses to about Ύd.

per £1. The expenses charged to the collective department by the

Insurance Society are limited to 5 per cent of the premiums. What a

great saving is effected will be apparent when it is realised how

great is the expense of industrial life assurance where the premium

is collected in weekly instalments from house to house. The average

benefit secured for a premium of £1 so collected is 11s. 5d. only;

by means of the collective method of the Co-operative Insurance

Society members may secure 19s. benefit for every £1 of premium

paid.

For the purpose of carrying out the jubilee celebration the annual

meeting of April, 1908, appointed a committee consisting of the

General Committee, the manager, secretary, and six other members

Messrs. John Woolley, Joe Ollerenshaw, George Barrett, A. Longden,

George Heathcote, and Arthur Hamer. Three months later it was

decided that the jubilee fund, already accumulating, should be

increased to £1,000. Mr. W. Wardle, J.P., and Mr. A. Longden became

jubilee secretaries, and the committee set to work.

――――♦――――

PART III.

The Jubilee Celebration.

AGED MEMBERS'

PARTY.

DURING the

jubilee year smoking concerts were held. The first function in the

scheme of the jubilee committee, however, was a gathering of aged

members from sixty years of age upwards on Saturday, 27th

February, 1909. Including members and husbands and wives of members,

some 450 tickets were applied for, and just about 400 persons

attended, although the weather was somewhat severe. Tea was served

in Old St. George's School, and at the Town Hall they were

entertained by Mrs. A. N. Turner (soprano), Mr. T. Shaw (bass), Mr.

Sam Hill (the local elocutionist), Mr. Sam Fitton and Mr. George

Hilton (humorists), and Mr. J. Cropper (pianist).

At the Town Hall Mr. John Fawley was chairman. In a

pithy address, he said it was the society's jubilee year, and it had

been decided that certain festivities should take place to celebrate

that jubilee. It was considered that the older members were

the first entitled to recognition, because they in years gone by had

done a good deal to strengthen and sustain the society, and to bring

it up to what it was that day. In May there would be held an

exhibition of articles made in co-operative manufactories, just to

show the members and the public what was produced by co-operators,

with co-operators' capital, for co-operators. Other parties

would be held, but the one which to his mind was most important, and

to which he looked with the greatest hope of success, was the one

which would be held in June the demonstration, procession, and

field day for the children of members. He trusted everybody

would help during those months; would do all they could to

strengthen the hands of the committee; and so contribute towards a

general success that jubilee year. Fifty years ago the society

had started, with a decision to supply the wants of the working

people. It was seen even in those early days that there were

many opportunities and advantages for working people in

co-operation. It was a banding together of working men that

started the movement in Stalybridge. They were men of ability,

of courage, and of determination. In the early stages they had

to prove to the people that co-operation was beneficial and

necessary to the workers. The society had in the early years

many difficulties, many trials. The American war broke out,

and many there that night would remember the great trials and

privations of those in the cotton manufacturing towns of Lancashire

in consequence of the war between North and South. The society

at that time was struggling very hard indeed, but the men in charge

were not easily daunted by obstacles. The society had grown

until it was the most powerful and influential trading concern in

the borough, catering for more than half the people of Stalybridge.

He trusted members would rally round and try to make that year of

their jubilee one of the best and most prosperous their society had

known. He could not call those present old people; he had

noticed that day much energy amongst them; but they would remember

the time when working people had shop-books, and credit, not

cash-trading, was the rule. Then came the co-operative

movement, and instead of a shop book a member was asked to have a

share book, with something to his or her credit. The

co-operative movement had done a great deal in Stalybridge, and he

hoped it would continue. He relied on the members present to

maintain it, to uplift it, to bring it to an even better position

for doing good than it had yet attained. He could assure them

that the committee, on their part, would do their utmost.

――――♦――――

TEA PARTY AND

CONCERT FOR THE MEMBERS

OF

MILLBROOK AND HEYROD

BRANCHES.

On the 20th March, 1909, tea was served to about 498 persons

at the Town Hall, and Mr. J. Fawley presided at the concert held at

the same place. He extended a hearty welcome to those present,

expressing the pleasure the committee felt at seeing so many members

there, taking their part in the jubilee celebrations. He

called upon Mr. W. E. Dudley, of Runcorn, who said he would, as Mr.

Fawley had promised, speak as one co-operator to another. He

associated himself with the co-operative movement because he

believed it was to the co-operative movement that they would have to

look for the salvation of the worker. The history of the

Stalybridge Society spoke volumes to him, and he would advise them

to let no one come between them and their society. Some queer

statements as to the aims and principles and effects of the movement

were made by some persons. He would be delighted if that hall

were occupied by such men, and if they would heckle him on the

subject. The movement sought absolutely earnest, whole-hearted

publicity. One object of that gathering was to create thought

and reflection, and he believed his hearers would agree that thought

and reflection in the hearts and minds and practice of the working

classes of this country were a standing necessity. If they and

he had many years ago thought more upon their own welfare and their

own doings, their position would have been different that day.

It had been said that ideas were like flowers weaving into garlands.

Could they not find in their own minds a necessity for garlands in

this life? Were there not many homes into which such garlands

had brought brightness? Carlyle had said "a thinking man is

the worst enemy that the prince of darkness can have." He

would give them three points of a creed of Robert Owen, stated in

1834. The first was that the wants of all mankind should be

met without slavery and without servitude. Robert Owen was not

a man wanting to make a position for himself; he was a man of

affluence spending his life and money in improving the social

condition of the working classes. He did not tell the workers

at that time that labour was not required; he said that labour was a

blessing, but that slavery and servitude was a curse. Their

chairman, Mr. Dudley continued, was concerned in the management of

another institution that did much to reward labour as it should be

rewarded. Not only did that society the Co-operative

Sundries Manufacturing Society pay full wages, but it contributed

bonus to labour in addition. That went to prove that where

production was brought under the influence of co-operation, slavery

and servitude were shunned. The workers shared in the profits

they created, and sanitary conditions and everything desirable was

brought in. The next point Owen wanted to raise was that all

must be made intelligent, and all must be made charitable.

Co-operators did not seek to take the workers outside their class,

but they did help them to understand the problems of life better

than they did before. Therefore they gave an opportunity of

seeing things in a different light, and as the intelligence of the

worker was raised, there would be a greater future for the

co-operative movement. In the third place, Owen wanted to say

that co-operation must get rid of buying in the cheapest market and

selling in the dearest. The producer in the outside world

wanted to find when he went to market that everything he was about

to put on the market was selling at the highest possible price.

The consumer, when he went to market, desired that he should be able

to purchase at the lowest possible price. The co-operative

movement stepped in to level these interests. His hearers were

both the producers and the consumers, and profit did not go to this

or that section, but was divided equitably. Co-operators

worked as a collective body, but observed the individuality of the

collective system, and in proportion to that which they were

prepared to contribute, whether in labour, capital, literary work,

or management, so in proportion would be their reward. Henry

Ward Beecher put it well when he said that to live aright and to

assist human progress means this that which you receive in seed

must be handed on in blossom to the next generation, and that which

you receive in blossom shall be handed on in fruit. Their

pioneers in Stalybridge took the seed and handed on the blossom.

They and he had that blossom; what were they doing to pass on the

fruit? They should use every effort to build up those

organisations of theirs, and then they could go on to the words of

Dr. Norman Macleod :

|

Courage, brother, do not stumble,

Though thy path be (lark as night;

There's a star to guide the humble

Trust in God and do the right. |

An excellent programme was rendered by Mr. E. Spafford's

Elite Concert Party, consisting of Miss Margaret Hadfield (soprano),

Miss Helena Joy (contralto), Mr. John Collett (tenor), Mr. Harry

Bray (baritone), and Mr. Frank Crawford (humorist), with Mr.

Spafford himself as accompanist.

――――♦――――

MOUNT PLEASANT

BRANCH MEMBERS'

GATHERING.

A tea party and concert for the members of Mount Pleasant

Branch was held at the Town Hall on Saturday, 3rd April, 1909.

Fully 600 people partook of tea, and an excellent programme was

rendered by a concert party directed by Miss Pennington, of the

Pennington Concert Agency, Longsight, Manchester.

The artistes were Madame Nellie Teggin (soprano), Miss Eva

Sparkes (contralto), Mr. John Moran (tenor), Mr. G. H. Ditchburn

(bass), Mr. Frank Crawford (entertainer), and Miss Pennington at the

piano. Mr. John Fawley took the chair, and introduced Mr.

Charles Wright, manager of Manchester and Salford Society.

Mr. Wright congratulated the members on the great meeting in

connection with the jubilee, and on the flourishing state of the

society. It reminded him, he said, of an old man whom he heard

at a party. He was a hundred years of age, and the jolliest

old fellow at that gathering. Somebody said to him, "Why,

John, you look as if you would live to be another hundred."

"Well," he said, "why should I not? I am a good deal stronger

now than when I started the first hundred." The society was

fifty, and he hoped it would go forward cheerfully and hopefully and

unitedly towards the next half century. It had passed its

infancy and early childhood, with the ailments incidental to

childhood. Now they appeared in full manhood and full

womanhood as members of a great and prosperous undertaking.

The society he represented had been interested in the movement at

Stalybridge right from the beginning, and he came that day from

18,000 members of Manchester and Salford to say to those of

Stalybridge, "Go on and prosper." The Manchester and Salford

pawnbrokers recently held their 100th anniversary, and they

congratulated one another on the soundness and progressive character

of the undertaking. He had no word of complaint against

"uncle," who had perhaps helped occasionally someone to tide over a

real difficulty, but there was an old proverb that "who goes

a-borrowing goes a-sorrowing," and while he said nothing about

visiting "uncle" for the purpose of getting a temporary loan, he did

feel that there was a danger lest that going to "uncle" should

crystallise into a habit, which would injure the moral fibre.

Turning from the pawnbrokers to the store, he said the latter had

something which no pawnbroker could show. His hearers were

members of a great body numbering two-and-a-half millions of

members, doing a trade of £103,000,000 a year, and dividing profits

amounting to £11,000,000. During the past forty-five years the

store movement in this country had earned for the members no less

than 165 millions. Where would those profits have gone if not

to members of co-operative societies? They would have made a

hundred millionaires; but better a million people with £1 each in

their pockets than one millionaire. Co-operators believed in

better distribution of the world's wealth, and if that were

achieved, there would not be such terrible stories of fellow men and

women on the brink of starvation. There was talk about the

greatness of our empire, and in many senses the empire was great;

but what was the good of an empire on which the sun never set to the

man or woman who lived in a court where the sun never rose. We

sang "Britons never shall be slaves." Were there not thousands

of slaves in every city throughout the land? Were there not

crowds of helpless women and girls whose everyday life was a fight?

He would give one or two instances of the pay to those women workers

in Manchester. For making roses such as women wear in their

hats, 3s. 6d. per gross was paid; for making parma violets and

scarlet geraniums, 7d. per gross; for making shirts, five farthings

each; and for making a pair of men's trousers, a woman was paid 5d.

The women-folks should remember, when they were tempted to rush

hither and thither, and to leave their own drapery store, that the

average wage of the women workers of this country only worked out at

1½d. to 2d. per hour. The

workers did not want charity to help in such cases; they wanted

better homes, better food, better wages, and more leisure to enjoy

them. Surely the day of doom for the sweater and the sweating

den was coming, and the day of hope for the toiler was at hand.

Co-operation was trying to remedy that; it was trying to uplift

people by paying a fair day's wage for a fair day's labour, by

providing for the workers healthy and well-appointed workshops, such

as the Stalybridge Society had in its tailoring department. It

was trying to span with a golden bridge that great gulf which exists

between the haves and the have-nots. He urged his hearers as

co-operators to work heartily and unitedly for their own, for the

growing good of this big and busy world. He believed the time

was coming when co-operation would be more widely known and

practised between man and man, and when it was, we should all

understand that the roar of the blast-furnace was better than the

roar of the cannon. It might be thought that this co-operation

was going on in England only, but there were 146 journals in the

world devoted to the popularising of co-operative principles, and

co-operation was being widely practised abroad. As it took

root abroad, people of different nationalities would look upon one

another as brothers, and, as Mr. Seddon, M.P., said, we should know

and feel that the gospel of co-operation was self-help, thrift, and

international amity. He asked all to take with them, as they

crossed the threshold of the jubilee into the next half-century, the

message of "Peace on earth; goodwill to men."

――――♦――――

HIGH STREET AND

CHEETHAM HILL

ROAD

MEMBERS' GATHERING.

There was a gathering of members from High Street and

Cheetham Hill Road branches on Saturday, April 17th, 1909. Tea

was served at Christ Church School to nearly 800 persons, and there

was a concert at the Mechanics' Institution. The artistes were

Miss Myra Dudley (soprano), Miss Annie Hargreaves (contralto), Mr.

J. W. Cottrell (tenor), Mr. Samuel A. Moore (bass), Mr. Fred

Ashcroft (humorous entertainer), and Mr. E. Spafford (accompanist).

Mr. George Hayhurst, of Accrington, a director of the

Co-operative Wholesale Society, addressed the gathering. He

was there, and he felt honoured thereby, to rejoice with them at

their jubilee. He noticed that it was announced on the

programme as a party for the younger members; he looked at some of

those before him, and thought well, that they were getting on.

(Laughter.) He had been trying to form a picture in his mind

of the old man of that day and the same man as he appeared fifty

years before. He was informed that a few of the co-operators

of those early days remained in Stalybridge. All honour to

them; the younger fellows before him owed a great deal to the grey

hairs, and they should always respect them. But for the

battles of their fathers, they would not enjoy the privileges they

did. At a conference he had seen an old man of over seventy

who heard another say, "Give me the good old days of fifty years

ago." "Nay, nay, noan soa," said the old man; "I were livin'

then, tha knows, an' I want noan o'th' old days; I have my tit-bit

now." He was delighted that the old people had their pension

of 5s. a week. (Hear, hear, and applause.) He was proud

that the Stalybridge Society had that jubilee year beaten its

record. Were they as good co-operators that day as those of

fifty years ago? (A voice: "Better.") He was glad to

hear that word "better." Those Stalybridge co-operators of

fifty years ago were proud of their little shop, and if his hearers

were as thorough as their pioneers, they would not go outside their

own shops for anything. He reminded his audience of the words

of the Rev. C. G. Lang, D.D., when Bishop of Stepney, at the

Stratford Congress Exhibition in 1904:

You won't forget, will you, those great ideals in the

midst of which co-operation was born, when the working classes were

banded together not only to raise their capital, but to raise their

character. You should always keep those ideals before you, and

maintain the honour of the goods you sell. Let it never be

said of co-operative factories that they turn out shoddy articles.

Let it never be said of a distributive store that it tried to make

money by permitting the sale of goods which could not possibly be as

cheap as represented unless there was sweating going on somewhere.

He had no patience, said Mr. Hayhurst, with the trade-unionist who

went into the cheapest shop he could find. Every

trade-unionist should be a co-operator, and every one ought to be

true to his ideals. Trade union funds had been the means of

keeping the wolf from the door, and from the Co-operative Wholesale

Society alone there had been over £300,000 expended in relieving

distress. He reminded his hearers that they were a part of

that great organisation, which had a trade turnover of nearly

£25,000,000 a year, and its own bank with a turnover of £100,000,000

a year. The power they possessed was power they should be

proud of and stick to. If, as one member present had said,

they were as good co-operators as those of fifty years ago, how was

it that of a trade of £100,000,000 done in the movement, only

£25,000,000 found its way to their own Wholesale? They could

make it more. An old lady of over seventy had given him a

motto. It was:

|

Whatever you are, be that;

Whatever you do, be true;

Straightforwardly act,

Be honest, in fact,

Be nobody else but you. |

The co-operative movement had been built up to what it was in spite

of opposition, in spite of boycotting; and, without legislation, if

all men were true brothers, there could be brought about such a

state of affairs as had never been dreamed of in the wisest man's

philosophy. They had, in their own Wholesale Society, people

working a 48 hours week, the men having a four-course dinner

supplied them for 4d. and the girls a similar dinner for 3d.

Those girls did not work in the clothes they went to and from the

works in. Such were the conditions under which the people

worked, and a good profit was made. Yet many of the mothers

present did not, he was afraid, buy the biscuits made by themselves

in those works. He had a message for the men, too, that they

could get the best clothes cheap from their own works without any

sweating. There was opened at Dunston-on-Tyne, the day before,

a soap works that would turn out over 200 tons of soap a week, and

when fully occupied 900 tons a week, without giving watches for

coupons. They had five flour mills of their own. They

were producing for themselves nearly £8,000,000 worth of goods every

year. If they were as good co-operators as those of fifty

years ago, Stalybridge Society would have a big increase that year.

People said we should buy from our own. "Yes," concluded the

speaker, "this society is your own, and be sure you buy from your

own. Be true to one another, and success will attend every

effort." (Applause.)

――――♦――――

HUDDERSFIELD ROAD AND

STOCKS BRANCHES'

PARTY.

There was a gathering of the members of Huddersfield Road

Branch, together with about a hundred of those of Stocks Branch, at

the Town Hall, on Saturday, April 24th, 1909. Tea was served

to 850 persons, and a concert was given by Miss Myra Dudley

(soprano), Miss Annie Barker (contralto), Mr. Stanley Jenkinson

(tenor), Mr. G. H. Ditchburn (bass), Mr. Fred Price (humorist), and

Mr. Ernest Spafford (accompanist). Mr. John Fawley occupied

the chair. He introduced Mr. William Lander, a director of the

Co-operative Wholesale Society, expressing a wish that everyone

present would think about what Mr. Lander said. He was a man

of vast experience in the movement, and there was no better to speak

to co-operators on co-operation.

Mr. Lander said it would seem almost unkind, with such a fine

programme before them, to ask them to listen to a long address.

It was fitting, however, on such occasions that something should be

said in reference to the co-operative movement. That meeting

was one of a series at which they were rejoicing over the attainment

of their jubilee. He was delighted to renew his acquaintance

with Stalybridge co-operators for the purpose of joining with them

in rejoicing that they had accomplished such an event and had made

such remarkable progress during the fifty years of their existence

as a society. He gathered from figures supplied to him by

their secretary that since they commenced they had done a trade of

about £3,000,000, and, as a result of their activity, had had

returned to them something like £430,000 dividend and interest.

Those were figures and facts about which they should rejoice, for

they spoke volumes for their appreciation of the advantages that

co-operation conferred on them in their own society, and proved to

them the value of combination for the improvement of the people.

Co-operation was a power and an influence for good in the State,

judging it by what it had done not only in that town, but throughout

the length and breadth of the United Kingdom, indeed almost

throughout the civilised world. Fifty years was an important

period in the history of the individual, the institution, or the

nation. Perhaps some of them had seen the realisation of fifty

years of married life and a golden wedding. The uniting of two

individuals represented in miniature the larger coming together for

the purpose of helping one another. Fifty years ago their

pioneers in Stalybridge, and those of many other societies, joined

together to improve the lives, to better the condition of the

people, in a word, to help one another. That was the basis of

co-operation, and it was a noble ideal that the movement always had

before it. To him co-operation was a profoundly sacred thing.

Social reform was, or ought to be, in the heart and mind of every

true citizen of this great empire, and co-operation was practical

voluntary social reform, a joining together for self-help and

self-improvement, and therefore true, practical, every-day

Christianity. (Hear, hear, and applause.) They in

Stalybridge had travelled fifty years, the movement had travelled

about sixty-five, and there were immense figures showing success all

along the line. Great difficulties had been encountered, but

unity of purpose, oneness of heart, and determination had brought

about the great result seen that day. Their society in

Stalybridge had been one of the blessings of their town. Its

influence on the distribution of the wealth of the town had made for

the domestic happiness of the people. Would anyone tell him

that the homes in Stalybridge were not that day better because of