|

INTRODUCTION

THIS is a book

that will keep summer in the house, even when there is a foot of

snow on the ground. There is sunshine on almost every page, for the

author had nothing else in his heart. He went along life's road

carefree as a bird, and singing his merry songs to cheer the weary

hearts of less happy wayfarers. Now he is dead, but his songs live,

and will live while men love joyous things. In this introduction, I

mean to tell the reader what kind of a man he was, what hailfellow

ways he had, and what pleasant paths of boon companionship we trod

together. I feel, that I owe it to his memory, for I do not expect

ever to look upon his like again. My concern is with the man, not

with his work. I leave that to the reviewers.

|

|

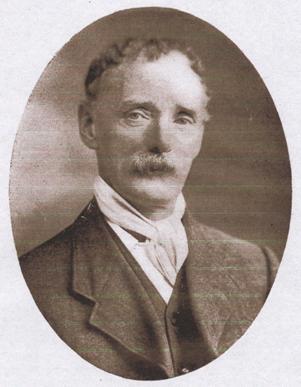

Ammon

Wrigley (1861-1946) |

Sam Fitton, one of seven children, was born on the 30th of June,

1868, at Smallwood, near Congleton. About 1870, his parents removed

to Rochdale, and afterwards settled at High Crompton. He started to

work as a doffer, and when he became a piecer he began to show an

unusual talent for drawing. His caricatures of the workpeople and of

well known local men were sometimes done on the interior walls of

the mill and were not allowed to be destroyed when the rooms were

whitewashed. All this came to the ears of Mr. Abraham Clegg, and he

sent the little piecer to the Oldham School of Art and paid for his

tuition. While pursuing his art studies he came out as a dialect reciter and won several competitions. At one hall, he took the first

Prize for three years in succession. Then he turned to authorship

and published a few booklets, including a racy "Unofficial Guide to

Shay (Shaw)."

He was one of the founders of the High Crompton Dramatic Society,

wrote the plays, painted the scenery, coached the players and took

the difficult parts. In the Autumn of 1911, he issued the first

number of, "The Crompton Chanticleer," a humorous monthly journal of

prose and verse that came almost entirely from his own pen. It

dragged on till April, 1912, and then ceased publication from lack

of support.

For years he was "Peter Pike," of The Cotton Factory Times, writing

and illustrating a weekly column of jest and good-humoured banter on

current events. He also wrote

dialect sketches to the same paper under the pen names of "Billy Bloggs," and " Sally Butterworth." His "Pancake Neet," "Village

Wedding," and many other playlets

are still performed in winter by Sunday School Dramatic Societies. As a member of the Oldham Dramatic Society, he often played the

first low comedy part. He was also a member of the Oldham Society of

Artists, and during his illness, sketched and painted in bed, till

he was too weak to hold either pen or brush.

As a public entertainer, he was for twenty-five years the delight of

Lancashire audiences. Few singers and reciters are authors, and his

concerts were out of the ordinary, as he rarely gave anything but

his own work, and he composed the tunes to his songs. He used to

say, "If I don't get an audience in three minutes, there is

something wrong with me." I have often seen people yawning with

weariness at some dreary concert item and then Sam burst on to the

platform singing

|

"Aw con run a good way when Awm op to th' mark

Aw like apple puddin' but Aw dunnot like wark." |

In a moment the room was ringing with laughter and he was held up

till it ceased. He had a remarkably mobile face and could make it

portray anything. His recitations were not only heard, they were

seen in his facial play. He used to amuse my folk by standing in

front of the mirror, and saying "Would you like to see Winston

Churchill?" "Yes." In a moment he would turn round and say "Here

he is." Then he would show us Lord Curzon, Admiral Beatty, and many

other notabilities. He had got their faces from the newspapers and

he changed from one to another in a few seconds.

He died on the 11th of June, 1923, and is buried in the cemetery at

High Crompton. His grave is marked by a small grass-covered stone

inscribed, S. F. No. 8249.

We knew each other when I lived on the hills in Saddleworth, and to

misquote Burns

|

. . . . . "ere years had run

Like waters to the setting sun." |

After the death of his first wife he lived in lodgings at Oldham,

and often came to my house at Waterhead, and called it coming home. He was then in poor health, and one night at a hillside inn called

"The Three Crowns," he said that he was weary of taking physic and I

must be his doctor. I assumed the professional manner, felt his

pulse, looked at his tongue and prescribed a strong tonic mixture of

moorland air, the smell of peat and heather, draughts of water where

it sparkled out of the brown earth, and a pot or two of ale at

bedtime. So in the long summer evenings, we went up the old farm

lanes to the hills, and wandered over field and moor till the sun

had reddened down into the smoke cloud of Lancashire. Then we called

at some lane-side inn and sat for an hour in the chimney comer

telling tales and learning each other's songs and tricks of mimicry. He "mended a cake at a meal," as farmers say of cattle, and often

said that I had saved his life. But it was not to me alone that he

owed thanks. It was the wind that blows from the Yorkshire moors

over the meadows in the haytime, that did much towards giving health

to his body and colour to his cheeks. It blows from the bracken in Wessenden, from the cloudberry on Isle of Skye moors and from the

heather below Far Wain Stones. There is the tang of the Pennine soil

and the savour of the open heaths in its breath, and to Sam, coming

from the smoky streets it was almost life itself.

He had no liking for long tramps over rough ground. I asked him to

climb to the Fairy Holes on Alderman moor. He replied by sending

eight witty verses to a newspaper,

here are two

|

So t'other day wi' good intent,

To roam those moorland wilds I went;

To sniff those breezes heaven-sent

'At Ammon likes to talk on;

But, Oh, mi legs, Oh dear o' me,

Th' owd hills were glorious I'll agree,

An' th' upland roads were good to see,

But bloomin' bad to walk on.

I cast mi een o'er Stanedge cut

I sized it up, an' scrat mi nut;

"Come Sam, be gam'," I muttered, but

I couldn't do it, drat it,

Mi heels began to warch an' brun

Mi wambly legs felt nearly done

An' as for climbin' Alderman

They warched wi' lookin' at it." |

There were nights in the old inns when extempore rhymes flowed out

of him, as if he were brimming over with song and could not stem it. A stray word spoken by one of the company, would set him jingling in

my ear.

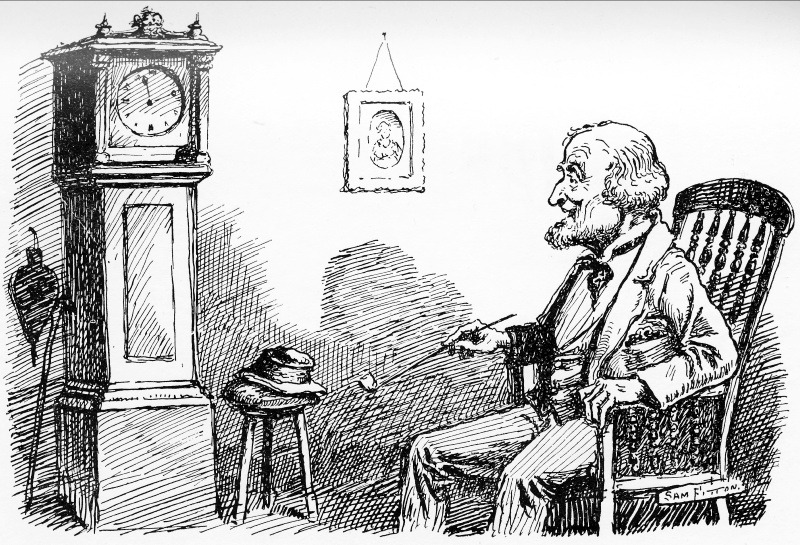

On our way home from the hills we often called at the "Tiger Inn,"

at Austerlands, that was then a joy to see. In its old ale room

there was the peace and restfulness of ancient days. Time had gone

to sleep there and many years had passed and brought no change. The

walls were whitewashed, the floor stone-flagged and worn by the feet

of bygone villagers. There was an old case clock with its moon dial,

a corner cupboard, rush-bottomed chairs with spindled backs, an oak langsettle and on the breadstrings above the hearthstone hung crisp

leaves of oatcake. The inn was then kept by a woman now dead, and

the way in which she conducted it, is one of the sweetest memories

of the village. She would have no drunkenness, no swearing, no

gambling and no sneering at religion. She was ever glad to see Sam,

and he often stood on the hearthstone and sang and recited till men

were doubled up and holding their sides with laughter. They caught

the infection of his joyousness and were the happier from having

known him.

We agreed to write something about the "Tiger," and he wrote his

famous "Owd Case Clock," and I followed with "Lines to an Alehouse

Pot," afterwards printed in "The Sign of the Three Bonnie Lasses." One evening at my house he gave me his poem written with pencil and

said "Read that and tell me what you think about it." There were

so many erasures and corrections that after blundering through the

first verse I said "We'll go to the 'Tiger,' and you shall read it

to the company. There were a few villagers in the room and when he

had read it we were delighted and pressed for its publication. He

refused, but after I had worried him for weeks he got it printed in

sheet form and one thousand copies were sold. He could recite it far

better than anyone that I have ever heard. It is considered to be

his masterpiece in verse and has been so often broadcasted, that it

is now well known all over Lancashire. Its contrasts, its comedy

and tragedy, its laughter and tears, and the pinch of hard times are

so charmingly introduced that they do not jar one's feelings. Still

I think, there are other poems in this book that when they are

better known will challenge the popularity of the "Owd Case Clock."

He often called me a brother bard, but we were miles apart in what

appealed to us and formed the subject matter of our verse. I am not

stirred by the town or its people, but to Sam, they were an

unfailing source of inspiration. He loved the herded houses, the

life and bustle of the streets and the clatter of clogs. To him they

were everything, to me they are nothing. I used to quote Borrow's

gipsy and say, "There's the wind on the heath brother." There is no

poem or prose piece in this book that is descriptive of the

countryside or of country folk. He never sang of fields, or streams,

or woodlands or of the wild life that is in them. I had often

wondered why, and one evening we were wading knee-deep through the

heather on Highmoor, away to the south was Wharmton moor, white as

new-fallen snow with acres of cotton grass. "There, Sam," I said,

pointing over the green farmlands, "is something worth a bit of

rhyme."

"Not to me," he replied, "I never write about the country, I have

never felt its call."

Of all the songs that I have heard him sing as we tramped at night

by the quiet farms on the hill roads, there is one that remains an

unforgettable memory. It was a song of a lad from the north and in

the chorus Sam placed one hand to his mouth and made the music of

bagpipes. I have never understood how he produced the weird skirling

strains that seemed to belong to the wild glens of Argyllshire. Perhaps in some way the mystery and the darkness of the hills got

into his music. I only know it haunts me.

|

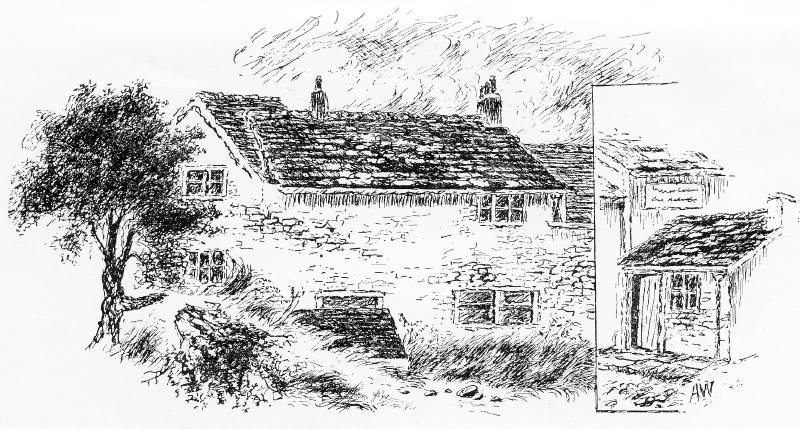

The "Royal Tiger" Inn, Austerlands, the scene of the "Owd Case Clock".

|

There is a story attached to his little poem, "To a Caged Lark".

Walking out one day he saw a lark in a cage outside a cottage door.

He sent his poem to a newspaper and when the owner of the lark read

it, he set the bird free. It is probable that other owners of

caged wild birds did the same.

When Sam Fitton comes into my thoughts it is not as a poet

and an artist, but first of all, as a most lovable man; a man that

people were ever glad to meet and loath to leave. In his

company they felt how good it was to be alive. An uplifting

cheerfulness runs through much of his verse. He is ever

reminding us of the old song, that says ―

"And joy is a cargo so easily stored

That he is a fool who takes sorrow aboard." |

He was first and last a dialect writer and in that literary

medium his wit is the brightest and his humour the most whimsical.

In ordinary English he was a skylark with one wing tethered to the

ground, but in the dialect he soared wing-free and wild with

spontaneous song. His versatility was amazing, and I often

wondered if there were anything that he could not do. The gods

had over-loaded him with gifts. With fewer, he might have gone

farther, yet he went far enough to leave a rich legacy of prose and

verse to all lovers of Lancashire dialect literature.

He was a poet, prose writer, playwright, painter, cartoonist,

actor, mimic, and an inimitable entertainer. For all his

gifts, he was wise enough never to write upon subjects that he knew

little or nothing about, and never floundered out of his depth.

He had not far to go in quest of material, he found it by his own

doorstep among his neighbour folk, and their foibles and

characteristics are herein depicted with wonderful truth and

vividness.

He was childless, yet had he been father of five children he

could scarcely have had more knowledge of their prattle and their

ways.

He was a master of dialogue, which he handled with singular

ease and naturalness, and his word pictures of Lancashire life and

character in the industrial areas will, I think, give him a high

literary place and an enduring fame.

The merry twinkle in his eyes and the laughter that played

round the corners of his mouth, led people to believe that he did

not know the meaning of adversity. But he did, and the pity of

it is that he died just when better days were in sight and he was

about to receive a well earned recognition as an author.

Outside one's own home folk, no greater loss can come to a

man than the death of a kindred spirit and boon companion. Six

years have gone, and even now, that is how I feel when I think of

Sam, and the happy Bohemian days we I spent together and of the

songs we sang at night on the lone highways and by the clear red

fires in old inn kitchens. I cannot think that it will be my

good luck to meet another man on life's road with such wit,

light-heartedness and charm of comradeship. It is ever so,

good days and good friends that are never replaced, and at last we

ourselves are swept away like withered leaves in autumn. Time

is ever taking the living in at one door and the dead out at

another. In our grey moods when our outlook seems drear as

winter, we feel that the southern poet was right, when he wrote ―

|

"What's the use to think or care,

Win or lose, hold or share?

What's the use to laugh or sing,

What's the good of anything?" |

Yet, when the sad days come, and come they will, the surest way and

a short cut to laughter and the light heart will be to draw a chair

to the fireside and open this book. The author died all too

soon, but as the years hurry on he will, I am sure become dearer and

dearer to the hearts of Lancashire folk, and when this and many

generations are laid in the dust,

"The passer-by will hear him still,

The lad that sings on Crompton hill." |

As I close this slight sketch, the October wind is blowing

through the grass on a grave in High Crompton Cemetery that may one

day become a place of pilgrimage.

A. W.

――――♦――――

|

THANKS ARE

DUE TO THE EDITORS

OF THE Oldham Chronicle

AND

The Cotton Factory Times |

――――♦――――

GRADELY LANCASHIRE

EAWR SARAH'S

GETTEN A

CHAP.

|

EH,

dear; There's bin some change in

Eawr heause this week or two;

Wheer once there used to be a din

It's like a Sunday Schoo';

We never feight for apple pie,

We very seldom frap;

An' what d'ye think's the reason why?

Eawr Sarah's getten a chap.

Eawr fender shines just like a bell,

We'n had it silvered o'er;

An' th' cat appears to wesh itsel

Moor often than before;

Eawr little Nathan's wiped his nose,

Eawr Jimmy's brushed his cap;

An' o this fuss is just becose

Eawr Sarah's getten a chap,

He's one o' thoose young "nutty" men,

They sen he's brass an' o,

My mother's apron's allus clen,

For fear he gives a co;

We'n polished up th' dur knocker, too;

We'r swanky yo' con tell;

But Sarah says it winno do,

We'st ha' to have a bell.

We bowt a carpet t' other neet,

To wear it seems a sin;

My feyther has to wipe his feet

Before he dar' come in;

He never seems a-whoam someheaw,

He says he's noan on th' map;

He allus wears a collar neaw

Eawr Sarah's getten a chap.

We'n serviettes neaw when we dine;

A brand new bib for Ben;

Eawr Fanny's started talkin' fine,

Wi' lumps in neaw an' then,

Sin' Sarah geet her fancy beau

Hoo fairly cocks her chin;

Hoo has a bottom drawer an' o'

To keep her nick-nacks in.

Hoo's wantin' this, an' wantin' that,

Hoo thinks we're made o' brass;

Hoo goes to th' factory in her hat,

Hoo says ut it's moar class;

Hoo's bucked my feyther up shuzheaw,

He darno' wear a cap;

He gets his bacco chepper neaw

Eawr Sarah's getten a chap.

He comes o' courtin' every neet,

He fills eawr cat wi' dread;

He's sky-blue gaiters on his feet,

An' hair-oil on his yed;

He likes to swank abeawt an' strut

An talk abeawt his "biz";

He's "summat in an office," but

I don't know what it is!

His socks are crimson lined wi' blue,

I weesh he'd do a guy;

I weesh he'd pop the question, too,

Or pop his yallow tie.

My feyther darno' raise a row,

An' th' childer darno' scrap;

We feel to live i' lodgin's neaw

Eawr Sarah's getten a chap.

He's put eawr household in a whirl,

He's sich a howlin' swell;

I weesh he'd find another girl,

Or goo an' loose hissel;

Eawr parrot's gone an' cocked its toes,

Eawr roosters conno' flap;

We'er gooin daft an' o' becose

Eawr Sarah's getten a chap. |

|

――――♦――――

SPRING CLENNIN'.

|

DOES anybody want a chap

For just a week or two?

Eawr heawse is like a bedlam, an'

I don't know wheer to goo.

Eawr Mary's started clennin' deawn,

An' when hoo gets it bad,

I feel just like a tiger, for

I get so ragin' mad.

It doesna' matter what I say,

Nor heaw I grunt an' groan,

I met as weel be silent for

I know hoo'll do her own.

Becose I towd her t'other day

Hoo'd made a mess o' th' place,

Hoo flipped some whitewesh in my e'e,

An' said: "Thee shut thy face,"

I conno' find a single thing

Hoo doesna care a fig;

I'm wearin' two odd stockins' neaw,

An' one's a lot too big.

I lost my jacket yesterday,

An' when I looked about,

I fun it in a dolly-tub

Hoo thowt it were a clout.

I lost my cap this mornin', but

I geet it back to-neet;

Some little lads were puncin' it

Abeawt i'th' t'other street.

Eawr Jimmy's smashed a picther frame,

'Twere awful yo'll agree,

He went an' put his foot through t'

"Rock of Ages, Cleft for Me."

There's mops an' buckets everywheer,

Yo conno' stir for lime,

But Mary looks as happy as

A saint, an' as sublime.

Hoo cooked a kipper for my tay

That werno' bad yo know

But when hoo coom to sarve it eawt,

Eawr cat had etten it o'.

Hoo's scrubbin' everything hoo sees,

An' moppin' neet an' day;

I conno find my road i' th' house

I'm like a waif an' stray.

Th' owd cat left whoam last Friday neet,

An' th' parrot sits an' swears;

I go to bed through t' window for

I conno' get upstairs.

There's rowls o' papper up an' deawn,

An' o' through little Jack

I went deawn t' street o' Monday wi'

A lump glued on my back.

Hoo's fun o' soarts o' lumber fro'

A bedpost to a nail;

I cornt tell heaw we'n getten it o',

It's like a jumble sale.

An' heaw hoo'll get it back again

Is moor nor I con tell;

I'll oather fotch an auctioneer,

Or goo an pop mysel'.

Hoo's slingin' whitewesh up an' deawn,

An' thinks it jolly fun;

I weesh some kindly neighbour 'ud

Adopt me till hoo's done.

When next hoo starts o' clennin' deawn

Hoo waint find me no moor;

I'st goo up in an aeryplaine

Or goo live deawn a sewer. |

――――♦――――

|

MONDAY MORNING.

(Pen Picture of Lancashire Life as it used to be)

FIVE-thirty a.m.,

an' a middlin cowd mornin.

Hoooooooeeeeeee. Ohhoooeeeeeee Dunno be alarmed, I'm

nobbut tryin to imitate a mornin buzzer wi cowd type. OOh―――――,

EEeeeeeeeeeeeoooooooooo. Han yo getten me? Bang bang

bang bang bang bang bang! Bum bum bum bum bum bum bum! A

pause. Then a bit moor Hoooooooooeeeeeeee. Then another

spasm o Bang bang bang bang bang bang! Rat tat tat tat tat tat

tat tat tat tat! Bang bang!

"Hey up. Na then, theer. It's hawf past five."

Bum bum bum bum bum!

"Hello! All right." That's a woman's voice as a

rule. Aye, t' poor mother has to yer for o' th' family.

Rat tat tat ta dithery tat, rat ta tat ta dithery tat! Bang

bang!

"Oh reet, oh reet. I yer thi, mon. I'm comin."

Another pause an then "Bill! Bill! Dost yer?

Bill wakken!" Elbow an rib business "Bill!"

"Haw?" That's Bill tryin to say "What."

"Come on, lad. Th' knocker-up's bin."

"O reet, Oh heck. I'm wary this mornin."

"Tha should ha comd whoam sanner last neet, George Robert!"

"Wha?"

"Come on, lad. Martha Lizzie! Serran!

Willie! John Thomas! Come on."

"Hel―――lo. I'b kubbid." Willie's cattahr does

bother him in a mornin sometimes. (Heaw the heck dun they

spell catarh? Never mind).

"George Robert, arto comin?"

"I yer yo, mon. What dun yo keep shoutin abeawt?

John Tommy, gerrup."

"Thee gerrup, I getten t'yed warch. An' beside, it's

cowd."

By this time Bill, t' husband, is puttin his cowd trousers on

and doin his best to throttle a tuthri words he hasno fun i' th'

dictionary. I do believe he's put his reet leg deawn his left

trouser. Aye, he has. He rips an tears an says ―――― "??

! ! ! ―――― ? ? ―――― ! ! D; ? ―――― ," (All solutions to me

together wi postal order for a thousand pounds). His wife

laughs an that's better nor skrikin so soon on in a mornin. He

is a brute at'll stop a poor hard workin Lancashire mother fro

laughin, or any other mother for that matter. Let husbands get

vexed if they want. Let o thoose who hanno put ther reet leg

in ther left pant throw the first bowster. Accidents 'll

happen in t' best regulated families so soon on in a mornin,

especially when it's cowd an dark.

"Willie."

"Whaw?"

Poor Willie's fairly done up an terribly sleepy, an it were

nobbut th' neet before he were tellin his mother he'd like to be a

sailor lad an' sail the angry sea, or else a bobby an then he could

stop up o neet.

"Willie, come on, my love, get up. Eh, dear, it seems a

shame for young childer to get up so soon. Come on Willie,

that's a love."

"Ib kubbid buther, Booeeoo: I coddo fide by stockid."

"Bless thi lad, wheer did ta put thi stockin last neet?

Martha Lizzie, get up an help eawr Willie to find his stockin.

Eh dear. I'm some wary this mornin."

"Tha mun stop i bed a bit, an I'll bring thi a cup o tay up,"

said Bill. Bill's th' husband, or "yon of eawrs" as hoo coes

him.

"Stop i bed eh? I favver stoppin i bed an o yon burn o

clooas to wesh. No fear! I mun get up or I'st neer ha

done. Serran! Martha Lizzie! Come on an shap!

It's gettin twenty to six oready, an see as that lad has summat warm

before he turns eawt. Thi lad's noan weel bi a greyt way."

Then there's a bit of scuffle an some skrikin fro th' back

reawm.

"Mother! Eawr George Robert's pinched my jinnybant

garter."

"I hav'no. It's my own. I nobbut geet it o'

Setterday. Pinch one of eawr Serran's. Get a bit o tape

or else go wi thi stockin deawn. Gerroff wi thi."

"Gi us that garter. Booo:――― Mother! Give it

us." Then there's a scuffle at brings "yon of eawrs" to th'

bottom o th' stairs on which he knocks wi th' poker.

"Hey! I'm comin' up theer in a minute." That

settles em. They'n sin him come up before, an felt him too.

Feythers are useful in their place. If they winnor punce th'

place too hard. Some feythers forget they'n bin lads once.

"Come on Martha Lizzie. Get eawr Willie off. Cut

him a butty."

"I don't want a butty, mother. Give us a bit o that

curran cake. I'm noan bread an butter hungry this mornin.

Wheers my cap?" He conno find his cap nowheer. His

mother says he should mind wheer he puts it of a neet. By this

time th' kettle's beylin an there's a saup o tay made.

"Mother, yo hanno put my breakfast up. Yo'n put eawr

Willie's up."

"Eh, bless us, I conno attend to yo o. Be sharp.

Reitch me that loaf. Will ta have a bit o that potted meyt?"

"Oh, heck. Yo hanno gan me no potted meyt."

"I know I havn't. I've put thee up a bit o that lamb we

had left from yesterday. Neaw come! Shap, o on yo!

Yo'll be lat. It's getten five minutes to six an, Willie, come

here. Let me put thee this muffler on. It's very cowd

this mornin, I can tell wi my rheumatics. Neaw, good mornin,

Willie, an see at tha eyts o thi breakfast." Hoo tees his

muffler on an kisses him nicely, "Good mornin my love, an do look

after that cowd. Tha't fair full of a cowd, I con see.

Kiss me again love, an good mornin." Martha Lizzie looks fed

up."

"Good bordid, buther." Eh, th' poor lad has a cowd.

"Atchoo, buther, cod I have a dew jersey for t' footboo batch o

Setterday?"

"I'll see. I darsay I'll beigh thi one. Good

mornin. Stick to his hond George Robert. It's happen a

bit slippy eawtside, an don't be so awkert."

George Robert: "Oh heck; put him a clen pinney on an' let him

stop awhoam an' play wi eawr Lizzie's dolly."

"Go on wi thi, an less lip. Tha were wor nor him when

tha were his age."

Bill, "yon of hers," tucks his clen overalls under his arm an

shaps for gooin. "Good mornin Bill, if tha'rt gooin. I

reckon tha's forgetten heaw to kiss me neaw same as thae used to do?

But goo on, it doesno matter."

Th' poor woman expects too mich. Bless my life, they'd

bin wed twenty-six year, an a husband's kisses winno last for ever.

Bill goes eawt laughin an saying summat abeawt him havin a cracked

lip or he would ha done. Eh, these owd wed fellies! Heaw

soon they forget at a woman's noan a chap. Hello, that's th'

six o'clock buzzer gooin neaw. Martha Lizzie's beawn to be

late. Hoo'll ha to run for it.

"Come, come Martha Lizzie! Tha'rt bown to get sacked.

Tha wants to come in a bit sooner of a neet astid o stonnin i'th

cowd, proppin th' heawse end up." Yo con guess by that at

Martha Lizzie's courtin. "My mother never would let me stap

eawt so lat of a neets."

"Oh, would not hoo? I weren't theer to see. What

abeawt eawr Sarah theer? Hoo coom in hawf an heawr after me.

But I reckon it doesn't matter for her. Becose hoo's courtin a

Manager's lad yo letten her do what hoo likes."

"I shannot axe thee when I mun come whoam," says Sarah.

"I geet whoam as soon as I could. They had company an they

axed me to stop to my supper."

"Swank," says Martha Lizzie as hoo banged th' dur too beawt

sayin good mornin. The mother sighs, "Eh, dear, childer are a

bother sometimes."

"Come childer, do hurry up! Yo make me ill wi your

waywardness. Good mornin John Tommy, an do be sharp.

Hey! Wait a minute. Tha's forgetten thi tay an sugar.

Eh dear! I conna watch o on yo. What's up wi thee Jack?

Getten tooth warch? Dear, dear! Tee thi scarf up thi

ears an keep thi meawth shut, an hurry up. Good mornin, my

lad."

They're o gone neaw. Quietness reigns supreme, barrin a

pair o' slutterin' clogs whose owner hasn't time to fasten em.

Then Hooooooooooeeeeeeeeeeoooooooow.

"Eh, hom, yon's t' six o'clock buzzer. They'll get

sacked as sure as sure. I weesh I could get em to bed a bit

sanner,Well, I'll have a saup o tay and then I mun leet that beyler

feigher. I've a big wesh to-day. Women's wark's never

done."

Two heawrs later hoo shouts lovinly fro t' bottom o' th'

stairs, "Cissie Ellen, come on love, an wakken eawr Joedy.

It's time I were gettin yo off to t' schoo. Joedy, come on my

love. Come on neaw, both on yo, an be sharp, then. I've

getten a bit o toffee for yo."

Who said "martyrs"? Gerroff!

|

How some poor women bear, to me's a mystery.

When writing of your heroines of history,

Pray tell in words of gold your page adorning,

Of this poor patient soul on Monday morning. |

――――♦――――

BAKIN' DAY.

(Pen Picture of a Lancashire Home).

A Lancashire working-class living room;

combining also drawing-room, smoke-room, and bakery, and

incidentally conversation room and conservatory, not to mention its

other utilitarian uses. On this Wednesday morning it contains

at conglomeration of baking mugs, loaf tins, and other baking

utensils. It also contains one Mrs. Brella, with one child in

the cradle, one double chin, one smiling face, two fat arms, and a

cheery disposition. There is a fast-gated clock on the

mantelpiece that tells a utilitarian lie by proclaiming bare-facedly

that it is ten o'clock. It isn't. It is only 9-43.

There is also half a pair of pot dogs perched open-eyed at one end

of the same mantelpiece. The other half fell and broke its

neck some weeks before owing to Brella pere, or "yon of eawrs"

unseating it while looking for his ever-lasting pipe-wire, a

happening that caused "yon of eawrs" to say, "Thoose pot dogs were a

blooming nuisance," and left the remaining dog, like the last rose

of summer blooming alone. As the scene opens Mrs. Brella is

discovered with her plump arms covered up to the elbows with flour

and dough, or "doaf" as she calls it, and she is doing her best to

replace the covering over the child's bonny sleeping arms by series

of contortions of her nose, her elbows, and her foot. The

child is disturbed thereby somewhat, and gurgles something that

sounds like "Google googooshy," but which the doting mother

translates into "Mamma, I'se got the tummy ache," and she forthwith

begins gently to rock the "kather" with her foot and mumble a song

something about a baby on a tree top, which song may have some

connection with the Darwinian theory after all.

The door opens and a too-raucous voice enters saying, "Mornin',"

Mrs. Brella, I want to know if "Shhhh, sh," said Mrs. Brella

shaking her fist. "I've just getten it to sleep at last.

T' little thing seems a bit fretful."

"Oh' I'm sorry. I were just thinking 'at ―― hello,

you'r bakin, I see. Dun yo allus bake at Wednesday?"

"Nawe, not allus, but I thowt I'd bake a bit to-day.

Yon of eawrs wininot ha' bowt bread. I have to humour him, yo

known. Beside, I'd rayther have it mysel. I thowt I'd

mak a pottito pie, too, while I were agate. Yon of eawrs likes

pottito pie. I'll tell yo what; beef's a rare price, yet,

isn't it?"

"I should think it is. It's time it coom deawn a bit.

Wages han comd deawn, an it's time a lot o other things coom deawn,

too. Mon, folks conno live."

"Thi connot. I know it taks me o my time to mak booath

ends meet."

"Booath ends meet, eh? I'm makin a flesh puddin for eawr Bill, an I

shanno try to mak booath ends meat. He'll ha plenty o pudd at booath

ends when I've done wi it. Fancy givin one an four for pie meyt. We

used to get it for sixpence when I were fust wed. An neaw they're

reckonin to blame it on t' foot-an-meawth disease."

"Foot an meawth my leg! I gan seven an six for a cock chicken o

Sunday 'at had no moor meyt on it than my feather boa. It were no

bigger nor a shuttle cock. I've sin mony a pigeon at could ha' gan

it a pound at a weighin sweep. Seven an six mind thi! That werno

caused bi th' foot and meawth disease were it? An look at thoose

eggs no bigger nor sparrow eggs an they cost me fivepence apice. Han they getten foot and meawth disease too."

"Nawe, I should think they'n getten th' maysles. They look'en

measley enough shuzheaw. I'll back eawr canary at laying bigger eggs

nor thoose. An then if we axe t' reason why, they say its on account

of t' price o corn an hen meyt. An look at price of corn. What's t'

reason it's so dar?"

"Eh, I dunno know, unless its getten th' foot and meawth disease

too."

"I'll tell thi what it is, Mary. We're bein robbed o ends up. Everybody seems to be after gettin summat for nowt, while us poor,

honest, hard-worchin folks han to worch, an worch an―――"

"An get nowt for summat," interrupted the other as she banged the

oven door hard enough to call forth another fretful wail from the

cradle, "Bless me, I've gone an wakkent t' child wi my bangin. Well

love, come den, shhhby-bye, babby mine, bo bo bo bo," Another rock

with her foot and half a minute of feminine silence and the baby was

soundly sleeping once more, and possibly dreaming of the days when

she, too, would pour forth loquacious invective anent undersized

cock chickens and oversized profiteers.

"As I were sayin," Mrs. Brella continued, "what wi one thing an

another, an this that an' tother, an a lot of other things beside, a

body con never tell when a body's safe fro other bodies, an I think

its about time at there were awterations. These profiteers desarve

hangin."

"They dun, Mary, they dun. Neaw look at price o bread to what it

used to be, I think some o these bakers want ――."

"Eh dear," yelled Mary. "I've gone an dreawned t' miller."

"Dreawnt t' miller has ta? Well dreawn t' baker while tha'rt at it."

"Eh, dear, there's a lot o awkert wark gooin on at present. Everybody seems to be gooin mad after brass."

"Ah, well, I reckon it's everybody for theirsel. It's quite

natural."

"I don't co it natural at o. Even t' cats an dogs know

when they're satisfied."

Just then a neighbour runs excitedly in at the back door.

"Missis Brella, be sharp. Yor cat's just run eawt at th' back dur wi

a lump o beef in its mouth."

Mrs. Brella was beside herself. Had she been beside the cat at that

moment I fear it would have lost at least two of its nine lives. Poor "yon of eawrs" would evidently have a 'tato pie in a literal

sense for his dinner that day. He would be too full for words, and

the cat would be too full for potatoes. It was a strange cat too a

barred one. Had the back door been barred also the family 'tato pie

would have gained by at least half a pound of nice pie meat, but

cats, like humans, are ever pleased to "take all" in this game of

Put and Take. Never mind, she said, he would have to make out with

currant bread, unless she ran across the way and brought him a "picklet

yerring."

"Eh, dear," she said as she wiped a tear from her eye with her hand

and left a piece of dough hanging on her nose like an icicle, "I

should ha' no luck at o' but for bad luck, I weesh I could just get

beside o that cat." But she couldn't for, as I said before, "Mrs. Brella was beside herself." She longed to make a wakes of that

feline, but she didn't. She began to make the currant bread instead.

"An look at price o currans an o. We connot afford to mak gradely

stuff neaw-a-days. I allus mak what I co 'enchantment curran loaf'

neaw. And she began to stick the currants in about shouting distance

from each other. Her neighbour called it 'shouting bread' because,

as she said, "Th' currans are so far apart at they han to shout at

one another to be yerd."

"Aye, that's a very good name for it too, but I co it enchantment

bread becose distance lends enchantment tha knows. An I reckon

they'll ha to shout when they want to talk o'er th' current topics."

"Tha'rt gettin funny Mary, an I think Eh, hello! Who dosta co yon? He's some swank, isn't he?"

"Weah, tha knows him. Its Owd Annanias Doodleum's lad. His feyther

used to go to t' school when we did."

"Oh, aye. An heaw long has yon mon had a motor car?"

Oh, ever sin I bowt thoose shares in th' Diddleum Spinnin Company. His feyther's a director theer, tha knows, an I reckon he's gan his

lad a push up."

"Aye well, I reckon its nobbut natterable. Their own helps their

own. I weesh yon of eawrs had a feyther at were a director. By the

way, heaw are to gooin wi thoose

shares? I reckon tha'rt pilin up an owd stockin somewheer."

"Owd stockin? Aye, by go! I connot afford no new uns shuzheaw. I did

get a bit o divi once, but I've yerd they're bown to mak another

call o five shillin a share an if they dun I'st ha to sell up to pay

it I'm afraid."

"Willta for sure? Eh, I'm sorry. It's hard wark when a body's done

her best an comes off th' worst."

"It is. But I reckon if folks geet on by merit only, a lot o folks

ud soon ha better doins nor they han neaw."

"Aye, an a lot of other folks ud soon ha to swap their motor cars

for shanks ponies. I dunnot envy nobody, but I do like fair play. I

reckon business is business, an we'st ha to win an lose like

sports."

"I know. I con do wi business, but I detest dodgery. Of course, I

reckon things are bad, an poor folks are sufferin a lot on account

of t' war an what-not."

"Tha's said it what not. It's that what-not at's causin a lot o

trouble. It's noan o t' war. It's that what-not an etcettera an

other things beside fair play at's ruinin a lot on us. Everybody's wantin to get howd. Tha never catches folks givin nowt away neaw a

days."

"Unless it's shares, an they conno gie thoose at time. It's awful."

"It is. Some folk han o t luck i t world. Look at Joe Coppall. He

hadn't a penny piece a bit sin, an his wife towd me tother day he'd

made three hundred pound wi jugglin wi shares this last two year. He

should ha bin weel off, but I darsay he's spent welly o on it i

drink."

"Hello, hushtl Here comes his wife. Talk o'er the

Mrs. Coppall rushes in with a face like a mixture of startled hare

and bogie-bogie. "Mrs. Brella! What dun yo think? Eawr Joe's had a

call o fifteen shillin' a share on thoose he had i th' Bunkum

Tiddley-wink Manufacturing Company. Eh hom, I dunno know wheer to

put mysel."

"Weah, yor Joe con pay om connot he?"

"Con he heck! Eawr Joe pay? Axe me summat yessier. Why he hasn't a

penny piece to bless hissel wi! Its sickenin! There's some feaw wark

gooin on somewheer! I weesh we'd neer had nowt to do wi their

bloomin shares."

"Oh, dear! It were o reet, I reckon, when he were makkin money! But

I think onybody at will gamble an play ony sort o' game owt to win

or lose like men."

"So do I," said the other, "but they owt to mak sure their playin a

game at's worth playin before they start. Fairation, that's the game

for me."

"Oh, it's o reet for you, Mrs. Brella, to talk like that. Yo'n lost

nowt yet."

"Nawe, an I've won nowt noather. Hey eawt! I mun shap my dinner. It's everybody for theirsel neawadays, isn't it Mrs, Taylor?"

"It is. That's what t' cat said, shuzheaw. But I'm gooin."

"I think its a bloomin shame," yelled Mrs, Coppall.

"They're a lot of rogues, an I weesh they were o' in――"

"Hey eawt! Hey eawt! My loaves are brunnin."

The oven door banged, the fretful baby awoke with a cry, Mrs,

Coppall swore, the loaves looked black, the family cat sprang in a

corner, the door banged, the dinner buzzer buzzed, the picklet

yerrin fizzed, the potato-pie blew the steam off, the potatoes

looked brown, the beef looked sick, the clogs outside clattered,

Mrs. Brella bustled, "yon of eawrs" swore, etc., etc., and so on

― and

that ended one half of the baking day.

――――♦――――

TO A SILK

HAT ON

SEEING IT ON A

RAG CART.

|

HELLO,

owd topper! What art doin' theer?

Tha once were indispensable an' needy;

Tha's lost thi bloom for ever neaw, I fear;

Tha'rt lookin' seedy.

When tha were in thi pomp an' feelin smart,

Tha little thowt tha'd later be i'th' cart!

Come, tell me, did thi mester look a gawk

When on his napper tha were gaily sportin?

An' did ta yer a lot o' sloppy talk

When he were courtin?

I'll bet he spread his feet when he were wed

If tha were nicely balanced on his yed.

But neaw he wouldna wear thi onyway;

I fancy he'd be feart o' Mrs. Grundy.

But tell me, did he wear thi every day,

Or nobbut Sunday?

I'll bet tha used to make a big to-do;

I fancy I can see thi in a pew.

Eh! heaw he loved to see thi glossy glare!

When th' sun were shinin' he were prone to praise thi'

An when he met a charmin' lady fair,

He used to raise thi.

Tha's often mixed wi' Lady de la Jones,

An' neaw they'n mixed thi up wi' rags an' bones!

Thi mester must appear to thee unkind,

I'll bet tha swelled wi' pride when he bespoke thi,

But neaw a bone sticks in thi gullet. Mind

It doesna choke thi.

Howd tight, or else they'll jowt thi off thi perch;

Tha'rt noan as safe as bein' in a church!

Tha'rt noan so very yessy, I con tell;

Tha allus were an awk'ard sort o' bonnet.

I used to wear a thing like thee misel,

But made nowt on it.

Thi owner happen thowt tha looked divine;

I allus felt at sort o' clown i' mine!

Thi silky face is wrinkled un an' feaw;

Tha'rt lookin' crushed, an' deawn tha's come a cropper;

But if tha'rt noan so very lively neaw,

Tha's bin a topper.

Tha'rt full o' wrinkles neaw tha'rt not i'th' swim,

Thi cup o' sorrow's full up to the brim.

When tha were younger, an' as breet as gowd,

Thi owner used to treat thi wi' compassion,

He wouldna recognise thi neaw tha'rt owd

An' eawt o' fashion.

I'll bet a penny, if he seed thi neaw,

He'd swear he'd never worn thitha'rt so feaw.

When he were showin' off o'er plainer men,

Did't' tell him tha were made o' rags an' papper?

An' if he geet swelled-yedded neaw an' then,

Did't' pinch his napper?

He brushed thi up wi' silk once, I suppose,

Tha's neaw a blackin'-rag beneath thi nose.

He's bowt a brand new topper neawan' eh!

Tha'd get thi rag eawt if tha seed him care it.

But, cheer up! Every topper has its day,

Tha'm grin an' bear it.

Tha met receive a gusset or a tuck,

An' shine againtha never knows thi luck.

Some hats are often doctored up, they sen,

Tha'll happen come across some other hatter,

An' if tha doesna rise an' shine again,

What does it matter?

Somebody has to get it in the neck;

We conno live for ever, con we heck! |

――――♦――――

"IT'S COWD

TO-NEET."

|

BY

gum, it's gone some cowd to-neet!

I think it's going wor'.

Come up, owd lass, an' warm thi feet;

An, Jammy, shut that dur!

An, come inside, monhas't no wit?

Thee goo eawt if tha dar.

That feigher dosna' draw a bit

Let's rake this bottom bar!

It's draughty, Jammy, stir thy feet,

An' fot' some moor coal,

Here, strike a match an' mak' a leet,

An' put that wood i' th' hole.

It's grooin' windy; heaw it moans,

"I'm cowd," it seems to say,

I feel it creepin' in my bones;

It's winter ony day.

Wheer's th' poker? Here, I'll mak' a glow,

An' then we'st tak' no harm,

I'll mak a cup o' tay an o',

To help to get us warm.

Ha' patience, then tha'st have a sup;

Hutch up an' brun thi toes,

It tak's a lot to warm us up;

We're gettin' owd, tha knows!

I feel reet wheezy on my chest;

But still we munno fret;

Cheer up, owd lass, we'll do eawr best:

We'st happen winter yet.

Let's try to live an' bear eawr yokes,

We'st both be warm in neaw;

We're better off nor lots o' folks

We han a whoam shuzheaw!

We'n done some teylin, thee an' me;

We'n had it rough. But come,

We winno growl shuzheaw o' be,

We're better off nor some!

Thank God we han a tuthri coals;

Let's pile 'em rayther heigher,

My heart fair aches for thoose poor souls

Who cornt afford a feigher!

There's Mrs. Jones next dur but one,

Hoo's short o' coal it's true,

What says to, mun we send eawr John

Wi' just a shool or two?

Just yer' thoose hail-stones heaw it blows!

Hello, here comes eawr Kate,

Eawr Harry's cooartin' now, tha knows,

I reckon he'll be late.

He had a muffler round his throat;

He winno tak' no harm,

He hasno' ta'en his overcoat,

But love 'ull keep him warm.

They'll get together, does ta' see,

An' hutch behind a wo'.

I know when I were cooartin' thee

I ne'er felt cowd at o'.

I love thi still, tha may suppose

But love grows cowd, they sen,

It wants a bit o' feigher, tha knows,

To warm it up again!

Well, never mind, we'n had eawr day;

We'n ne'er rued gettin' wed,

Come, lass, let's have a cup o' tay,

An' then we'll go to bed. |

|

"IT'S COWD TO-NEET."

――――♦――――

EAWR SAY-SIDE

LODGIN' HEAWSE.

AN ATTRACTIVE RETREAT.

|

I'm livin' in a sayport, wheer

It's awlus breet an' shiney;

I keep a little boardin'-heawse

At Blackpool on the briney.

Come up an see, you'll quite agree,

It's natty, neat an' clever,

An' if yo'll spend a week wi' me

Yo'll want to stop for ever, |

SO when yo'r sick

o' worchin', an' yo'r nerves are feelin' funny, pack yo'r bag an'

come to me, but don't forget yo'r money.

Nawe! yo' munno forget that, if I connot awlus mak' dacent

room for you, I con manage to find a corner for yo'r rhino i' yon

owd stockin' o' mine. Money's the root of all evil, they sen,

so yo' bring it to Blackpool an' improve yo'r morals. What's

th' good o' walkin' abeawt wi' fifty-one weeks' gooin'-off club

money i' yo'r pocket if it breeds badness. Bring yo'r root to

me, an I'll soon stop it fro' sproutin'. I con cure yo' o'

twelve-months' evilness in a week if I want.

But it's a takkin' little heawse is Sea View. One

cynical visitor said it should ha' bin coed Deceive You, as he

couldn't see th' say at o'; but that wer' becose a fat bobby wer'

stood wi' his back to th' corner o' th' window. We'n every

convenience; hot an' cowd wayter well we'n nobbut cowd really, but

yo' con soon get it warm wi' swearin' at it an' knockin' it abeawt

wi' bein' vexed; but it's a takkin little place, so is my missis; in

fact, some say 'at hoo's too takkin' for out, but, then, as I say,

it 'ud bi silly takkin nowt, wouldn't it?

Oh, but it is bonny! Trams pass th' door sometimes.

Ther' wer' one passed yesterday. Some hen farmers at Marton

'ad bowt it, an they wer' takkin' it whoam on a lurry. Ther

wer' a tram run off th' line t'other week, an turned deawn our

street; an', as luck would have it, ther' wer' one o' my visitors in

it, an' it chucked him eawt, an' he leet wi' a bang up agen eawr

door. When I went to look he wer' hangin' on th' door-knocker

wi' his braces.

"Hello!" I said, "I see tha's had a special tram."

"I have," he said. "But I conno' say as I like th' road

they chucken 'em eawt."

But some folk are so particler. Onyheaw, I gave th'

conductor tuppence, an' towd him to come deawn onytime when he

wanted a change an' he geet a bit off th' line.

But, beawt jestin', it's a conny little spot. Yo con

see Douglas of a clear day when yo'r i' th' Isle o' Man. Yo'

wouldn't believe it beawt yo' seed it; some folk winno' believe it

when they seen it. We believe i' havin' plenty o' air, an'

they getten it at eawr heawse especially i' th' sitting reawm, wheer

ther's a window brokken.

It's a treat to see 'em when it's a extra warm dey, feightin'

for that window, so's they con sit wi' the'r back to it.

There's a nice, leet-coloured draught blows deawn t' back o' the'r

neck, an' they fancy the'r havin an heawr's sail. I charge 'em

extra for sittin' theer.

An' then th' piano! It's a grand! I know it's a

grand, becose I yerd a musician say so t' other day. He'd bin

playin' a tuthri twiddley bits on it, an' when he'd done he shut it

up, an' I yerd him say to th' tother visitors:

"Hum! It's a grand piano that!"

I didna' like road 'at he said "Hum!" for o' that. It

is a piano, shuzheaw. It's bin as good as a little hen farm to

me. Yo' seen, one o' th' front legs is lose, an' some

youngster's sure to knock it fro' under afore th' week-end, then it

go's deawn on the'r bill, "Damage to piano, five shillings."

Then I shove it under ready for th' week after. It drops every

week durin' th' season, so yo' seen if th' piano's noan mich yed

abeawt it, it has a good understonin' an' that's bin worth summat to

me.

But fancy! who ever knew a lodgin'-heawse piano at wer' i'

tune? I awlus tune mine misel.' I haveno' lived i'

Blackpool o' mi life beawt knowin' summat abeawt sharps an' flats.

Folk connot expect a full military band for two bob a neet' an'

extra's for cruet what they dunno' use.

|

We'n getten' a little

garden, an'

A

cheer for you to sit in;

It's very nice for t'

women, when

They come an' bring the'r knittin';

Or when it's bin a rainy

day,

An' th' promenade's a puddle,

It's just the place for

courters when

They want to sit an' cuddle.

An' wi' should have a splendid view, if t' street wer'

noan so narrow,

An' but for t' tother heawses wi could see across to

Barrow. |

Yo' know some folk are so particler. Ther' wer' a felly

coom an' stopped six weeks one day; an' he wer' awlus losin' summat;

he'd com'd for a rest, he said, so one day his wife coom o' seein'

heaw he wer' gooin' on.

"Oh!" he said, "I'm havin' a jolly time, lass,"

"Oh, arto?" hoo said. "Well! tha go's whoam wi' me

to-morn, so I'll goo an' pack thi bag up."

Hoo' coom runnin' deawnstairs in a minute or two after an'

sheawted.

"What hasto dun wi' thoose six shirts tha' browt wi thi?"

"I dunno," he said, "ther' up theer, I reckon," so he went up

o'lookin', an' in a bit he coom deawn.

"Eh, lass!" he said, "what doesta' think? I've getten'

'em o' on!"

An' me thinkin he'd getten steawt wi' good keep.

Ther' wer' a big fat woman coom once, an' hoo browt her two

childer wi' her, a lad an' a chilt. Hoo grumbled becose th'

bath wern't big enough. Yo' know I couldna pretend to measure

everybody for a bath. Well, wi had two baths really; they wer'

two bakin' mugs, so I towd her hoo must put one foot in each mug,

an' wesh a bit at once. Hoo didn't expect a swimmin' bath at

two-bob a neet, an' extra for blackin' boots' which they awlus did

thersel' wi' an owd rag an' a tin o' cobra.

That woman did carry on becose I wouldna' let her two childer

pluck th' fleawers i' th' back garden; we'd nobbut two, an' one o'

thoose wer' deeod, but t'other looked champion when t' sun wer'

shinin' on it. So I said they must rowl abeawt on th' lawn.

Of course, it's nobbut a little lawn, two or three sods 'at th'

misses rowls every mornin' wi' th' rowlin'-pin. It 'ud favver

a bowlin' green if th' grass wern't black.

"Well, they started o' rowlin. Of course, they couldna'

rowl above once an' a hawf a'piece afore they wer' i'th' slutch, an'

then th' woman wanted to blame me becose they'd dirtied the'r

pinnies.

I like to yer' these young couples best when they'r sit on th'

garden seat of a neet time; I yerd one young love-sick felly say to

his girl once.

"Tha knows that letter tha sent mi t' other day?"

"Aye, Joe! What abeawt it?"

"Well, I absolutely licked th' stamp, becose I knew tha'd

licked it wi' thi' lips."

"Eh! tha' silly un!" hoo said, "I didna' lick it at o'; I

rubbed it on eawr Carlo's weet nose, I awlus do so,"

Blackpool's a rare place for courters. Giddy Cupid's kept

very busy turnin' factory lasses into duchesses, an' big piecers

into promenade coppers-on, an' six-day millionaires, but, eh! bless

em! I do so like to see 'em ogle one another. They're o'

Venusus an Adonisus for one week eawt o' th' year shuzheaw.

They con pay as mony respects to one another as they like if they'll

pay my bill at th' time. So when yo'r feeln' yo' want to get

beawt yo'r dumps an' yo'r money, yo' mun ―

|

Come to Blackpool! Breezy Blackpool!

When yo'r after lodgin's, yo' mun come an' stop wi' me!

When yo'n had enough o' wark,

If yo' want to see a lark,

Come an' have a paddle in the deep blue sea. |

|

――――♦――――

OWD TIMES AN' THESE.

(A Lancashire Sketch).

|

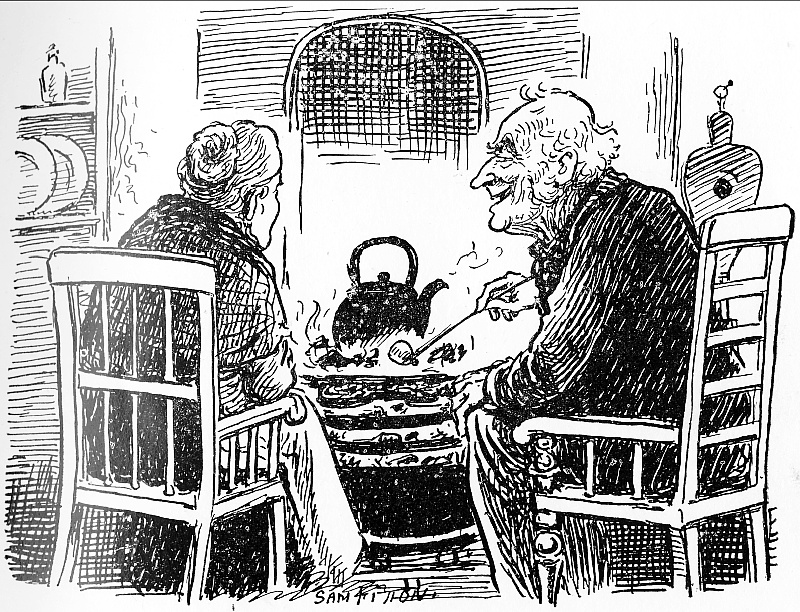

OWD

BEN WEATHERBY

(Grandad) is seen pottering about his frugally furnished kitchen. He

is an old retired cotton worker who lives by himself on the small,

though hard-earned, savings of a strenuous lifetime. Though poor, he

is an optimistic, convivial old codger, with health, wealth and

wisdom enough to enable him to enjoy his closing days as well as any

retired weaver of seventy-eight can do. Having just finished

chopping sufficient firewood to last him for a week, he lays by his

well-worn chopper and stretches himself.

Grandad: That'll last me for a bit shuzheaw. I mun keep warm so lung

as I'm on t' top of this bit o' dirt, for goodness knows heaw cowd

I'st be i th' next world. I reckon I'st ha to tak pot luck abeawt

that. I dunno think St. Peter has a greyt deel o black marks agen my

name i that owd book of his. They con put me wheer they'n a mind if

I'm just warm enough to be comfortable. Ooh my back! I'm noan quite

as swipper as I were when I wrastled owd Twister. Poor lad; he couldno put a strangle howd on a fourpenny rabbit at present. He's wor nor me. Never mind.

Then he begins to sing:

|

|

I used to go singing as blithe as the day,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I allus were glad when I had my own way

When I were a bit of a lad.

I geet what I wanted, or somewheer abeawt;

I geet lots o jam, when my mother were eawt;

An sometimes I geet sich a heck of a clout,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I spent o' my time at a bit of a schoo,

When I were a bit of a lad,

An one day I spent o my schoomoney too,

When I were a bit of a lad,

They taught me to read, an to reckon, an parse;

They talked abeawt Mercury, Venus, an Mars;

An when I were stupid they made me see stars,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I fell deep i love wi a girl in eawr street,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I took her a walkin one Seterday neet,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I said hoo were nice an I coed her a duck,

I gave her a ring an a penny for luck;

An then I kept rabbits an gave her the chuck,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I went in an orchard one day for a lark,

When I were a bit of a lad,

I geet amung th' apples an made weary wark,

When I were a bit of a lad.

Then th' owner coom up an he said wi a frown,

"I'll make thee sit up in a bit tha young clown,"

Then he made me sit up till I couldn't sit deawn,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I ripped my best trousers an thowt it were prime,

When I were a bit of a lad,

In fact I met say I'd a rippin good time,

When I were a bit of a lad.

One cowd frosty mornin I ran off fro t' schoo;

I tumbled i th' well an I went welly blue,

Then I geet a good hidin for getting weet throught,

When I were a bit of a lad,

I started o smoking a penny cigar,

When I were a bit of a lad.

But someheaw I think I were noan up to par,

When I were a bit of a lad.

I smoked till I felt dear o me, well I'm sure

My tummy went reawnd, and I crawled up o th' flure,

An then well, I connot remember no moor,

When I were a bit of a lad. |

|

Then

he tries to dance and resembles nothing so much as a hamstrung

cab-horse with a double touch of St. Vitus.

Grandad: Eh, it's no use trying to dance, Ben, my lad. Thy doancing

tackle's rayther to' stiff i' th' cranks. Thy game's sittin deawn

for th' remainder o thy days, or else takkin a tuthri drops o monkey

gland juice wi thi supper drink every neet. I weesh I could dance

like that little grandowter o mine. It's as good as a dayful o

spring sun to see her merry little een, an my owd heart goes up a

huntin th' larks cheerin trill when I yer her prattlin tongue

[There is a lively knock at the door.J Bigum, hoo's here.

Hoo never misses comin to see me every [His grand-daughter, Fanny,

enters, full of flapper-like exuberance. She is a girl of twenty or

thereabouts who talks fine.J

Fanny: Good morning, Grandy. How's the rheumatics this morning? Better, I hope. What can I do for you? What? Have you washed up

already? Well, well, you are a busy old I mean young Grandy.

What have you been doing?

Grandad: Oh, different things tha knows. Come an sit thi deawn. Eh,

I am some an glad to see thi. Ceawer deawn, lass. Ceawer thi deawn.

Fanny: You mean "sit down" Grandy. Why do you say "ceawer?"

Grandad: Becose I meeon "ceawer." "Sit," met suit yung uns, sich as

thee, but I'd raythey ha "ceawr." It sounds softer, an beside, it is

"ceawr," so na then.

Fanny: All right, old sport. I'll bet you were a caution when you

were a lad.

Grandad: Goo on wi thi bother! I were as good as ony other lad as

bad as mysel. I weesh tha'd ha lived i thoose owd-fashioned days,

Fanny. We used to co a spade a spade then.

Fanny: And what do you call it now Grandy a knife and fork?

Grandad: What I meeon to say is, we're livin in a day o make-believe

an sham neaw. A gentleman were a gentleman then.

Fanny: That's right, old bean.

Grandad: Owd bean? I'm not an owd bean. Tha'll be co'in me a

peighswad next. Do I favver an owd bean or summat?

Fanny: Oh no. You look more like a beetroot with whiskers on.

Grandad: For shame on thi! Co me a skallion an ha done wi

it. Tha

owt to respect thi superiors. I don't know what yo lasses are comin

to.

Fanny: That's right, old cock. Ooh;

sorry! I mean, that's right, Grandy. You know I wouldn't

hurt a hair of your dear old head. [She strokes his grey hair.J

Grandad: It's very nice, Fanny, but I have no chocolate.

Fanny: Don't want any. Have a tab, Grandy? But see, I've brought you

some tobacco. Now then. I don't want your choc choc, thanks.

Grandad: It's very good on thi. Eh, but I weesh tha'd

ha lived i' thoose owd days when folks were better behaved nor they

are neaw.

Fanny: We are not all heathens now, Grandy.

Grandad: Don't yo weesh yo were? Heathens didno

used to wear corsets to show off their figures.

Fanny: No; they showed off their figures with no

clothes at all, but we don't do that.

Grandad: Not quite, but yo'r improvin. Yo soon

will do if Dame Fashion doesno mend her manners. Women o'

to-day han rayther too mich neck stickin' eawt. They'r stickin'

eawt all oer arms, legs, an necks. They favvern porcupines.

They're too artificial, Fanny.

Fanny: Well, the heathens used to paint their faces

Grandy. The new times are by far the best. Listen. I'll

recite you a bit I've written out of my head. [She recites.J

Oh give to me these modem times,

With things I love so well,

Where roads are full of motor cars |

Grandad: An a gradely nasty smell.

Fanny: Doen't interrupt me. Where roads are full

of motor cars

Grandad: Be careful! Tha'rt at wrung side o th'

road.

Fanny (impatiently): Oh, Grandy, do let me get on.

Grandad: O reet. Hasto thi sparkin plug i order?

Fanny: Oh, please Grandad. Where roads are full

motor cars

Grandad: Be sharp an mind o gettin run oer.

Hurry up, lass. Sithee! There's an owd woman oer theer

wants to cross th' road. Hurry up, there's a bobby comin.

Fanny: Oh, do let me get on.

Grandad: I'm 'noan stoppin th. Tha's put th'

motor cars theer thisel. Shift em, or change thi gear, for thi

subject. Hasto put ony petrol in thi tank?

Fanny (reciting):

Give me the good old iron horse,

With speed that's most terrific:

Its grace is grand, as o'er the land |

Grandad: Its smell is petrolific.

Fanny: Order please! let me finish.

O'er hill and dale we scorch along,

To where the skies are bluer:

We leave behind the maddening throng |

Grandad: An then run up a sewer.

Fanny: Oh, do stop it, Grandad.

Grandad: Hey! Stop that motor car! It's

beawt muzzle, an it hasn't getten a license. Sorry, Fanny.

Get forrad.

Fanny (reciting):

Give me the days of push and go,

Where cars and trams are horseless |

Grandad:

Aye, wheer a crazy horn they blow,

An run oer folks remorseless. Konk, konk. |

Fanny: Oh, do please shut your konk.

Grandad: I shall do when that motor car

comes past.

Fanny (reciting):

No joys were in those good old days,

No pleasures to relax us:

No lamps to light the roads at night |

Grandad: An no Lloyd George's taxes.

Fanny (stamping her foot): Do let me get

on.

Grandad: Aye, we o want to get on, but we

conno. We're taxed too mich. ―

Thoose good owd days had good owd ways,

Some which I'd like to mention;

There were no strikes nor free-wheel bikes |

Fanny (struttingly): And there was no old

age pension.

Grandad: Hello, tha thinks tha's scored

one, doesta?

Fanny:

There were no trains in those slow days,

They'd no hygienic houses,

Those slow old folks had no new jokes ― |

Grandad: An they'd no pneumonia blouses. ―

They didno paint their faces then,

They were allus strong an boney,

We were full o grace, an we went the pace, ― |

Fanny: But you went on Shank's pony.

The modern girl is best by far,

She's livelier and plumper, ―

She jumps o'er hedges, jumps on cars, ― |

Grandad: An sometimes through her jumper.

Tha knows, Fanny, it tha'd nobbut talk English ―

Fanny: Nobbut? There's no such word

as "nobbut" in the English language.

Grandad: It's nobbut a poor language then. I

like "nobbut." Only's nobbut a makeshift. I'd rayther ha

"nobbut."

Fanny: There you go again.

Grandad: I nobbut spoke. I nobbut said "nobbut."

Fanny: Yes, and a vulgar word too.

Grandad: Nay, "nobbut's" nobbut one. Talk

gradely an say "Puddin."

Fanny: Your dialect is far too crude,

It's far too many bumps in;

Give me the land where English reigns ― |

Grandad: An folks talk fine wi lumps in. Oh,

Fanny, do talk gradely,

Fanny: Who says "gradely."

Grandad: O' gradely folks say "gradely." Tha

conno find a gradely word to equal it in thy superfine talk.

If tha'd nobbut say "gradely" astid o' "awfully nice," an' "nobbut"

astid o' "only," tha'd talk English.

Fanny: I think your dialect is simply awful.

Grandad: An I think talkin too fine is awfully simple;

so we're two apiece, so let us change t' subject an shap a bit of a

sis for t' baggin. So long as we're both gradely jannock an

han a bit o cake-brade on th' bread-fleyk, an a thible to stir up

eawr porritch we dunno need gawm whether we coen a kayther a cradle,

a feigher potter a poker, or lobscouse tato ash; so put th' door on

th' sneck an I'll put th' draw tin up an we'll shap a bit o dinner.

|

――――♦――――

WATCHING THE WEDDING.

The Villagers Enjoy One of Their Little Excitements.

|

TRULY one half of

the world would be surprised to learn how the other half seeks its

enjoyment. Our smoky village situate amid the cotton mills of

Lancashire has little in the way of recreation during the course of

its work-a-day week. No fine ladies and gentlemen on

well-groomed hunters, plus a picturesque pack of hounds, ever grace

its sombre precincts. The only society functions or Royal

processions it is conversant with are those reproduced on the sheet

of the little kinema a couple of miles away. Barring the usual

morning gossips and an occasional tune on a discordant piano-organ,

a wedding at the little smoke-stained church is the only

entertainment our hard-working villagers receive unless it be a

funeral. I cannot understand why our villagers delight in

watching these latter sad ceremonials, but they do. Verily

human nature in some places is strange. I can excuse them for

desiring to know the style and colour of the bride's dress, the

state of her health, and the colour of her complexion, etc., for

that, no matter in whatever state of society, is woman's weakness

or shall I call it her curiosity? Of course I needn't tell you

that women comprise the greater portion of the spectators at our

village weddings. Long before the happy event takes place the

most curious portion of our villagers have known, about it.

But it is on the morning of the actual ceremony that curiosity and

excitement hang on tenter-hooks. Leaving their homes, and

often their children, to fend for themselves, our stay-at-home

female populace throw their shawls over their shoulders and hurry,

sometimes breathlessly, to the church gates to await the interested

couples as they emerge from the hired taxis. Oh, yes, poor

people manage to afford taxis somehow. Come and lean over the

church wall with me and listen to the remarks, often made in the

crudest vernacular.

"Be Sharp, Serran. They're comin, they're comin.

I wouldn't ha missed this wedding for th' world. Eh' sithee.

Here's th' bride. Isn't hoo bonny?"

"Hoo is. I like her dress. I'll bet yon dress has

cost a bonny penny."

"I don't think so. Hoo's made it hersel, they sen.

It's nice, shuzheaw. I like her hat an o. Bless her!

Wheer are they gooin to live? Has ta yeard?"

"They're goin a livin wi her mother. They sen they

conno' get a house. I dunno know wheer they're goin' to put 'em

o'. They'n a house full o' ready."

"Its sickenin isn't it? Folks han to live somewheer, an

I reckon couples han to get wed sometime or else th' world ud stop.

They conno goo on courtin for regular. I reckon human folks

are noan like cats an dogs."

"Some are an some aren't Mary Allis. There's some on em

live cat an dog lives, shuzheaw. It ud pay a lot o couples

better if they kept courtin' for regular."

"Nay; give th' divorce courts a chance. If folks never

geet wed a lot o magistrates ud ha to goo on th' unemployment books.

An what abeawt th' poor parsons? They want to live tha knows."

"I reckon they dun. I wonder if they'll drop th' price

o their weddin fee neaw th' price of living has come deawn."

"Why? Has th' price o livin come deawn or summat?"

chimed in Missis Quivver, a woman with a houseful of children and a

larderful of space. "I know one thing. If it go's ony

heigher I'st ha to dig for worms an turn my childer eawt to grass,

if it hasn't o bin brunt up. It's us women who han to goo a

shoppin as knows whether th' cost o' livin' has come deawn or not.

It's o' bunkum."

"Aye. Thoose newspapers try to mak us believe owt, but

they conno mak us fat wi thin paragraphs, nor keep us warm wi cowd

print. Look at th' price of beef. That's thick enough

isn't it? An they coen this liberty."

"O there's plenty o liberty in th' lond at present, Mary.

Tha'rt a pessimist. There's ony amount of profiteers about yet

wi plenty of liberty to fleece us. I wonder they dunno lock a

tuthri on em up."

"Hear, hear. They'd jolly soon lock us up if we were to

steyl a loaf."

"Eh, that reminds me. I've left my loaves ith' oon.

I weesh they'd be sharp an come eawt. I want to see em."

"I'st ha to goo in a bit too. I've left yon of eawrs

weshin eawr little Jimmy oal o'er an pillin th' potatoes. I

towd him he mun mak' th' beds an o, for I don't believe i speylin a

husband for want o wark. I con humour him."

"For shame on thi. I reckon tha towd him tha'd love,

honour an obey him when yo geet wed. I believe i both pooin

one road. It pays best i th' long run."

"Oh, aye. Thy husband's an angel wi fithers on, Ann

Jane."

"He's noan henpecked, shuzheaw. Henpecked husbands han

a habit o turnin round later on in life. Then th' fun starts."

"Shut up, both on yo. It's a weddin, noan a row.

If folks geet wed becose they loved one another astid o gettin wed

just to put their bit o money together there'd be a lot moor

pleasure an fewer divorces ith' world."

"Eh, heck! Tha should ha bin a parson. Did tha

get wed for love?"

"I did. An onybody who gets wed for owt else desarves

to be miserable o their life. That's what I say. A

life's happiness doesn't end when courtin stops, when there's ony

love abeawt. A gradely happy couple ull goo on courtin for

ever. Gettin wed for money alone is an insult to th' wedding

ceremony,"

"Oh dear! Yer yo at th' little turtle dove talkin!

I reckoned to get wed for love, but my husband's noan a saint by a

greight way,"

"Nawe, but it's thy own faut if he isn't. Tha wants to

use moor tact, moor ――"

The Sentence is broken by the sound of jubilant voices near

the church door.

"Hurray! "Weesh yo mich happiness." "Wheer's that

confetti?" Be sharp. Goo on. Give em some moor."―

"Cheer up Sarah." "Weesh yo mich happiness."

"Eh, bless her. Isn't hoo nice? See yo, look at

thoose little childer. Look at thoose flowers. Eh,

sithee, sithee, her fayther an mother. Poor owd sowl.

Hoo'll miss that lass of hers. An' Joe. Watch him smile.

He's o reet, is Joe."

"Is he?" said Mrs. Pessimist with a sneer. "That's o yo

known. He's no better than he owt to be. It o depends

heaw he turns eawt."

"Gerroff wi yo. Don't measure a peck eawt o yor own

seck. Weesh thi much happiness, Joe. That's it.

Give him some confetti."

The crowd laughs, cheers, yells congratulations, and smothers

the happy couple in good wishes and tons of confetti. Sunshine

and joy is in the air, that is marred only by the still small voice

of the soulless pessimist who will insist on snarling, "Oh, aye.

It's o reet, but they're noan o weddin days."

Poor, pitiable creature. And thrice happy couple.

|

――――♦――――

TH' CHILDER'S

HOLIDAY.

|

EH dear, I'm

welly off my chump!

I scrub, an' wesh, an' darn;

Eawr childer han a holiday,

An th' heawse is like a barn.

Yo talk abeawt a home sweet home!

My peace is flown away;

I have to live i' Bedlam for

A fortnit an' a day.

They're in an' eawt fro morn to neet,

I met weel look so seawer;

They're wantin pennies every day,

An' butties every heawer.

They'n worn my Sunday carpet eawt

Wi' runnin' up an' deawn;

Eawr Polly broke a jug to-day,

An' Jimmy broke his creawn.

They'n nobbut bin a-whoam a week,

But, bless me, heaw they grow;

An' talk o' childish innocence,

The devil's in 'em o.

They'n smashed a brand new dolly tub,

An' o' my clooas pegs;

They'n rattled th' paint off th' parlour door,

An' th' skin off th' table legs.

They started pooin th' picters deawn,

One neet when I were eawt,

Eawr Tum geet th' "Rock of Ages," an'

He gave eawr Joe a clout,

Eawr Bill, who has a biggish meawth

He's allus in disgrace

Set off cowfin t' other day,

An' went reet black i' th' face.

He'd swallowed th' babby's dummy-tit

Wi rawngin wi eawr Bet;

We'n gan him tons of physic, but

We hanno fun it yet.

Eawr Jack's a plester on his nose,

An' th' beggar looks a treat;

He'd pood his tongue eawt to a lad

Who lives i' Stoney-street.

Eawr Bobby's bin i' bed o day,

Poor lad, he does look hurt,

He went o bathin' yesterday,

An' some'dy stole his shirt.

They're o so full o dirt an grime,

I'st never get 'em clen;

I'st ha' to scrape 'em when it's time

To go t' schoo again.

Eawr Tommy says he winno goo,

That lad's a wary wight.

He's had his thumb i' th' mangle, an'

He swears he conno write.

I sat me deawn o Wednesday neet,

An' th' parson's wife were theer,

I hope hoo didno yer me swear

They'd put a pin i' th' cheear.

I'd lock 'em up i' th' schoo for good

If I could ha' my will;

I'd see they had another clause

I' th' Education Bill.

I've clouted 'em an' slapped 'em till

My honds an' arms are sore;

I'st fancy I'm i' Paradise

When th' holidays are o'er.

They're like a lot o lunatics,

They'n getten eawt of hond;

But yet, I wouldno part wi 'em

For o there is i' th' lond. |

――――♦――――

TO A FLY

STUCK FAST

ON A

FLY PAPER.

|

EH! neaw tha's

gone an' done it!

Tha'rt in a sticky mess for sure!

Tha's done some buzzin' far an' near;

Tha's bin a rogue, but neaw I fear

Tha winno

steyl no moor.

Tha should ha' bin more careful,

For neaw tha never knows thi luck!

Tha's caused some trouble tha'll allow!

Tha's takken liberties ― but neaw

Tha favvers

bein' stuck.

Eh, fly, tha's bin a terror;

When in mi' cheer I've tried to doze

Bi th' hob-end of a winter's neet,

Tha's crope in eawt o' th' wind an' sleet,

An' often browt thi dirty feet

An' warmed 'em

on mi nose.

Tha's groped abeawt i' places

'At hadna' sich a pleasant smell ―

Na', stop thi buzzin' an' be good,

I conna save thi if I would;

Tha shouldna root abeawt i' mud;

Tha's done it

o thisel.

Thee goo on wi' thi poatin,

But nob'dy seems to care a rap;

Tha'rt same as us: we smile an' wink,

An' work an' dodge for meyt an' drink;

When we're i' th' sun we little think

Ha' soon

we'st be i' th' trap.

Get deed, then tha'll be quiet,

Tha'll do no harm then onyway!

I knew a fly bi leet misled

'At flew i' th' gas an' brunt its yed,

But it did harm when it were de'd

Wi droppin'

in mi tay!

By gum tha'rt fairly stickin'!

An' yet it welly sarves thi reet;

I've sin thi try to wesh thi shirt,

But other times I've felt quite hurt;

Heaw oft hast com'd in eawt o' th' dirt

An' never

wiped thi feet?

We're towd we owt to starve thi!

An' yet I conno' tell thi why;

If we mun live we'st want some corn,

It isno' eawr fawt we were born;

Men allus looked on thee wi' scorn,

An' hollered

"Kill that fly!"

Tha allus were a nuisance,

A tantalizin', buzzin bore!

Yo'r o a set o' thieves, uncle'n,

Yo' flies are good for nowt they sen;

The better deeds o' flies an' men

Are often

smothered o'er!

We'n lots o' human bein's,

Who're quite as big a pest as thee!

They suck their brothers through and

through!

They're terrorsan' to tell thi true

I rayther think there's one or two

Who don't

think mich o' me!

Get forrad wi' thi deein'!

There's once apiece for thee an' me;

Too often in this worldly state

We see eawr fawts a bit too late!

We winno' growl an' rail at Fate;

Let's say:

"It had to be!" |