|

[Previous page]

AN EYE FOR AN EYE

WE were in the

weaving shed — old Harry and myself — he doing his best to initiate

me into the make and method of the looms filling the vast square

devoted to the claims of commerce; while I, ignorant and dull,

vainly endeavoured to master those lessons in mechanics which my

mentor had acquired, not in the schools, but by rule of thumb. As I

looked at the network of belting, the horizontal lines of shafting,

and the multitudinous array of wheels, I was dazed; nor did the

naming of the various parts of the machinery help me. What did I

know of ‘tappet-shafts,’ ‘crank-arms,’ ‘breast-beams,’ ‘heald-rods,’

‘monkey-tails,’ and the like? It was as though I were listening to

one who spoke in an unknown tongue. What did rouse my attention,

however, was the warp and weft and shuttle, those old-world

preachers as to the fate and brevity of man’s life.

Perhaps it was the shuttle that played most suggestively upon my

imagination; for I had read of it so often, poet and philosopher

alike weaving it into the web of their song and soliloquy; the

world’s first great dramatist, even in a patriarchal age, when the

span of life was long, speaking of his sojourn as being swifter in

flight than its leap along the parted threads; so taking up one in

my hand and showing it to Harry, I quoted to him the ever memorable

lines.

His imagination, however, had been cultured in a school other than

mine, for with a smile of sarcasm, and a gesture of impatience, he

looked up into my face and said :—

‘Them as weyves has no time for poetry. I’ these days th’ shuttle

preyches th’ race of steam, an’ th’ clock yon th’ flight of time,

an’ you’ve to keep up wi’ both. Nowe,’ he continued, ‘there’s noan

mich poetry for them as works i’ th’ factory; an’ as for shuttles —

if them as works wi’ ’em durnd look aat they ged one i’ their ee ’at

makes ’em see stars.’

This was indeed a step from the dramatist to the mechanic, and threw

into striking contrast the ancient and cultured philosophy of the

East, with the rude and commonsense utilitarianism of a commercial

age.

Once more I turned to the shuttle, still eloquent to me despite the

prosaic criticism of my friend. Turning it over, I mused as I looked

at its long and smooth and arrowy form, tapering off at the ends,

and tipped with steel. Then I too became prosaic, for as I drew my

fingers along its glossy surface, and let them glide over its

shining metal point that swept so deftly through the warp, I thought

of the sweat it wrung from the toiler, as with nimble fingers she

sought to keep pace with its flight, and I tried to calculate what a

blow from it would mean when propelled by the power of steam. Then,

turning to the old man who stood by my side, I asked him if

accidents from the flying shuttle were common, or their consequences

disastrous.

‘Yi, common enough,’ he said. ‘Th’ shuttle doesn’t tell yo’ when

it’s baan to fly, nor where it’s baan to leet. As often as not it mak’s for yor dayleets, an’ then, as aw tell yo’, yo’ see starleet,

an’ happen after that no leet at all. Aw never had one i’ my ee, bud

aw’ve had one near enough to mak’ the sparks fly;’ and the old man

pointed to a scar on his cheek which, though long years healed,

still told its tale.

‘Yo’ll ha’ noticed,’ he said, ‘that aboon a few of th’ lasses oather

skens, or are baat one e’e.’

I told him I had noticed the defect, and often wondered as to its

cause.

‘Well,’ he continued, ‘them’s ’em ’at’s been hit wi’ th’ shuttle; th’

skenners wearin’ a glass e’e i’ th’ place of th’ one ’at’s lost,

t’others bein’ content wi’ th’ one ’at’s left.’

‘And what is the cause?’ I asked, — ‘carelessness on the part of the

workpeople?’

‘Nay, not awlus; happen th’ loom’s slack set up, or th’ warp bad; it

doesn’t awlus foller.’ And the old man led me in and out amid the

narrow alleys and between the close-set looms, philosophising or

explaining as became his mood.

Suddenly he stopped, and putting his lips to my ear that I might the

better catch his words, he said:—

‘Talkin’ of flyin’ shuttles an’ blind een, aw con tell yo’ th’

queerest tale aat — a tale as true as th’ sunleet ’at’s pourin’ in

through th’ topleets yon. It’s abaat a lass as used to weyve at

these very looms agen which we’re stonnin’. Bud come i’ th’ boiler

haase — there’s too mich din here for talkin’ to th’ likes of yo’.’ So we adjourned to the spot in which the old man was always

eloquent, and where in times past he had recounted to me so many of the strange stories of his life.

‘Yo’ never knew Blind Bess? Nowe! Well aw durnd know as it matters

mich; bud aw knew her both lass an’ woman for thirty year. Hoo were

a quiet sort, one as noabry had aught to say agen, an’ abaat th’

best weyver i’ th’ shade. There were more nor one as wanted to wed

her, bud like as hoo took on wi’ Neddy Brown, one of the carters for

th’ mill. Ned had nobbud one fault — he were terrible havin’ (mean),

an this were awlus geddin’ him into lumber. He used to talk aboon a

bit abaat marryin’ a four-loom weyver, and what brass hoo were

addlin’, an’ haa mich they were baan to save when they were wed, an’

all th’ rest on’t, until folk fair cried shame on him, for th’ lad

were noan baat brass hissel’, let alone marryin’ a lass as were to

wark to help to keep him.

‘Bud he were noan to have it all his own way, as yo’ll yer; for one

mornin’ Bessy’s shuttle flew aat, an’ tumbled her o’er into th’

alley; an’ when they piked her up they fun’ her ee were mashed, an’

her face covered wi’ blood. It were a seet, so them said as see’d

it; an’ when they geet her home th’ doctor shook his yed, an’ said

he were afeeard t’other ee would go an’ o’; an’ so it did, for the

lass never see’d agen.

‘At first Ned made a great to-do, an’ were awlus hangin’ raand the

lass i’ his spare haars. It weren’t long, haaever, before he took to

stoppin’ away for a week at a time, an’ began to ged uneasy like

when he were by th’ lass’s side. Then i’ a bit he wrote a letter to

her mother sayin’ as blind folk were no use to him, an that he mut

be like to wed a woman ’at could see.

‘Th’ news of th’ letter soon spread through th’ village, an’ Betty

Pillin’, an owd Methody, an’ a class-leader wi’ whom Bessy used to

meet, set off to settle the job wi’ Ned.

‘“Ned,” hoo said, when hoo geet to his haase, “when arto baan

to marry Bess?”

‘He were fair takken to, an’ towd some sort of a lame tale as roused

th’ owd woman’s temper.

‘“Thaa doesn’t meean to say as thaa’rt baan to sack her, doesta?”’

‘But Ned nobbud told her that blind folk were no use to them ’at had

their livin’ to ged.

‘“For shame o’ thysel’!” th’ owd woman shaated. “If thaa sacks yon

lass, th’ Almeety’ll punish thee as sure as thaa’s a mon. Bud come,

aw think better on thee, Ned;” an’ hoo talked i’ her coaxin’ tones.

“Thaa’ll marry her, willn’t ta?”

‘Ned were noan to be moved, haaever, an’ he axed Betty who’d cook

his meeat, an’ wesh his bits of linen, an’ mend his clooas, if he

wed a woman ’at were baat een.

‘“Do thy duty, lad,” said Betty, “and the Lord’ll look after thee,

an’ bless thee, an’ cause His face to shine on thee.”

‘“If th’ Lord had meant me to marry Bess, He wouldn’t ha’ takken her

seet,” replied Ned. “There’s no stonnin’ agen Providence, thaa

knows.”

‘“Providence?” cried the owd woman; “Providence, didta say? Arto one

of those foo’s as saddles Providence wi’ th’ sins of th’ world? It

were noan Providence, lad; it were a bad warp.”

‘Bud it were all no use; an’ Ned telled her as th’ Almeety

manifested Hissel’ i’ o’ mak’s of things, fro’ a jackass to Balaam

to a shuttle to hissel’.

‘Bud if Bess were baan to be baat her seet, Ned were noan baan to be

baat a wife; for afore th year were aat he paired wi’ Rachel

Ratcliffe, a shy sort of a lass, an’ as timid as hoo were shy.

‘Hoo weren’t at first for keepin’ company wi’ him; bud there were a

big family on ’em at home, an’ her mother said at hoo munnot throw

away her chonce. So they were wed; but somehaa or other Rachel never

seemed to thrive after.

‘What it were noabry could tell. Ned were noan a bad husband, an’ th’

lass had a daycent home. But still hoo were awlus frettin’, an’ hoo

lost her colour an’ looked drawn under th’ een. It were soon th’

talk of th’ village; an’ there were as said as Rachel were carryin’

summat on her mind.

‘One day Betty Pillin’, th’ same as went to see Ned, took on hersel’

to go an’ see Rachel an’ o’, for hoo were a sort of mother i’ Israel

to all th’ lasses, an’ Rachel, like Bessy, had met i’ th’ owd

woman’s class. “What is it thaa’rt carryin’ on thy mind?” hoo axed

th’ lass. Bud Rachel said nowt. Then Betty talked to her kindly

like, an’ said as hoo’d known her, an’ prayed for her, sin’ hoo were

a little un; bud hoo nobbud cried an’ said nowt. Then Betty told her

to think of th’ childt ’at th’ Lord were sendin’ her, an’ to try an’

keep up for its sake. Bud when hoo spoke abaat th’ childt Rachel

brast into tears, an’ threw her arms raand Betty’s neck an’ telled

her it were that ’at were troublin’ her.

‘“It ought to bring thee joy, lass,” said Betty, “an’ not trouble. Childer’s a heritage fro’ the Lord, thaa knows; they come to mak’ us

younger as we grow owder, an’ it’s th’ fulfilment of th’ Covenant

an’ o’; thaa’rt one of th’ highly favoured among women, thaa mun

look up.” Bud it were no use; Rachel kept sobbin’ as though hoo were

burdened wi’ some sin.

‘“Thaa’s done nowt wrong, hasto?” asked Betty.

‘“Not as thaa meeans,” said Rachel; “bud aw’m feeard aw’ve done

wrong i’ marryin’ Ned, after he’d sacked poor Bess an’ o’. Aw welly

awlus see her wi’ her blind een; neet an’ day hoo follers me like a

boggart; aw cornd ged her aat of my seet.” An’ then hoo telled Betty

haa hoo prayed abaat it till her knees were sore, bud Blind Bess

were awlus afore her.

‘Betty were an owd woman, an’ knew what were what i’ family life, so

yo’ may be sure hoo were upset abaat what Rachel towd her; but hoo

put a good face on’t, an’ said hoo munnot be foolish, an’ tried to

talk her aat of her consait; an’ when hoo left th’ haase th’ lass

were a bit more lively like.

‘Haa things would ha’ gone on aw cornd say; happen Rachel would ha’

getten o’er her trouble o’ reet if it hadn’t been for a sermon hoo

yerd preyched th’ Sundo’ neet after fro’ Joel Ramsbottom.’

‘It isn’t often that aw trouble parsons, or chapels oather, bud aw

thought for once i’ a while aw’d turn in an’ yer owd Joel, as he’d a

gradely name for preychin’. Them as once see’d him ne’er forgeet

what he were like, an’ them as once yerd him ne’er forgeet what he

said. He were a chap as carried no sunleet i’ his een — it were leet

o’ th’ other sort — o’ Siniai an’ hell. There was noan as didn’t

fear him, bud th’ fear were like th’ candle to th’ moth — it drew

folk fro’ th’ whole countryside.

‘That neet th’ chapel were craaded, an’ Ned an’ his wife sat i’ th’

gallery o’er th’ clock, where there were no geddin’ aat for noabry. Aw were just at th’ side on ’em where aw could see their faces baat

any trouble. Ned were as cool as when he were whistlin’ by th’ side

of his horses — yo’ never knew a meean un yet as weren’t brimstone

proof; an’ as yo’ may suppose th’ chap as could sack a lass becose

hoo were blind were noan ahaid of th’ likes of Joel Ramsbottom.

‘Well, there were a great brast off wi’ th’ singin’, an’ then come a

prayer ’at roused th’ congregation to shaatin’s an’ clerkin’s till

yo’ couldn’t tell who were th’ loudest, th’ parson or th’ people —

it were like a row i’ a fair. Then he gave aat his text. It were i’

th’ Old Testament somewhere, abaat th’ sins of th’ faithers bein’

visited on to th’ childer to th’ third an’ fourth generation.

‘Like as aw looked straight at Rachel. Aw couldn’t help mysel’, aw

couldn’t for sure; an’ there were a good many i’ th’ congregation as

did th’ same. Aw see’d her change colour as soon as th’ owd chap

started, an’ if ever there were a soul i’ purgatory it were hers

that neet while Joel were preychin’.

‘He towd us ’at th’ Almeety were a mon as never broke His word, and

that His threatenin’s were “Yea” an’ “Amen” as well as His promises. There were nowt, he said, ’at God said He’d do ’at He wouldn’t do,

whether it were i’ th’ way of clamnin’ folks or savin’ ’em. “It’s

not what yo’ ax for,” he shaated; “Esau axed for repentance, bud did

he get it, an’ did his childer? Wasn’t it over Edom ’at th’ Almeety

cast His shoe?” Then he went on to tell ’em as sin were a long debt,

an’ when it were forgiven it weren’t forgetten, an’ ’at th’ third

an’ fourth generation come in for th’ first generations marlocks. He

said there were little uns i’ th’ graveyard naa becose of their

parents’ misdoin’s, an’ folks i’ ’sylums an’ hospitals becose they

were born o’ corruption. Then he poo’ed hissel’ together, an’ fixed

his een on Ned, an’ says, “Yi, an’ there’s other sins an’ o’ — sins

of unkindness an’ cruelty as are paid back wi’ compaand interest to

them ’at’s guilty on ’em, an’ to their childer after ’em.”

‘“Yi!” he said, stretchin’ aat a finger like a pickin’-rod, while th’

fire glinted fro’ his een, “yi, to th’ third an’ fourth generation.” Then he went on to tell abaat families he’d known as had sinned agen

God an’ their felley-men, an’ had getten dominoe (an expression

illustrative of a sad end); guzzlin’ folk has had left a terrible

thirst i’ their children’s throttle; rich folk who’d made their

brass by cheatin’, whose kin had died i’ th’ work-haase; lyin’ folk

who passed on their repitation as a legacy to them as came of th’

same breed after ’em. “Th’ third an’ fourth generation,” he shaated,

“caant it up for yorsel’s. Yo’ eyt sour grapes an’ yore childer’s

teeth ’ll be set on edge; an’ there’ll be no cure for it noather. Th’

third an’ fourth generation — that’s them as is unborn, an’ them as

’ll be born when yo’re deead. Yi, though hond join in hond, th’

wicked an’ their seed ’ll be punished for ever.”’

During the description of the sermon the old man so worked himself

into a dramatic mood that I too was lost in the scene and in the

subject, realising for the moment the spell of this modern prophet

Joel. I felt the hot breath of the excitement, the strained silence

of the crowd, the terror roused in those hundreds of hearts that

hung upon the preacher’s words, and above all the agony of that poor

girl so soon to be a mother, and haunted with the terrible

anticipation that her husband’s sin, and her own for marrying him,

would be wreaked by an avenging deity in the blindness of her child; and as the strain wrought by the old man’s story was relaxed, I

was thankful that a milder religion than Joel Ramsbottom’s was the

one in which I had been nursed.

As the engineer paused in his narration, wiping the sweat from his

brow with his wad of cotton waste, he was called away by the manager

to another part of the works, leaving me in uncertainty as to the

fate of her whom he had so eloquently described; and as he did not

return I journeyed to my lodgings, curious as to the sequel.

Circumstances, however, sometimes play the part of interpreters; and

it was to be so in this case. On the following day, as I was walking

across the meadows, I met a number of children at play, among whom

was a fair-haired little girl joyous as her companions, and fully

sharing in their glee, yet with a movement about her I could not

understand. The longer I watched her the more I was perplexed, until

at last curiosity prompted me to approach and speak with her. Judge

my dismay when I found the little one was blind, yet gifted the

while with that added keenness of the other senses which is one of

Nature’s kindly laws of compensation.

I spoke with her, as well as with her companions, and told them

about the flowers among which they sported, and whose varied colours

gladdened all eyes but one; and I daresay the incident might have

been forgotten had not one of the children said, ‘Tell Rachel Brown

haa bonnie th’ buttercups are.’

When I next saw old Harry he remembered the sudden interruption

which his story had received at the hands of the manager, and would

have recommenced it, and carried it to its finish. I laid my hand on

him, however, and said, ‘I know all.’

‘Have yo’ yerd, then?’ he asked,

‘No,’ I said; ‘I have seen.’

――――♦――――

HEPHZlBAH’S VICTORY

‘JACKASSES an’

women weren’t in it.’

We were walking along the lodge banks, the setting sun

gilding its sluggish waters, and lighting up with flashing fires the

windows of the many-storied mill. Around us sported the rising

generation, of whom old Harry knew and cared but little; while on

the moorland side lengthening shadows were thrown from the grey

headstones that marked the sleeping-place of the generation over

which he was so fond of musing.

It was a reminiscence of one of this generation that called

forth the quaint soliloquy with which I begin this story — a

reminiscence of one of the original founders of the firm, Jonas by

name, and already mentioned in a previous sketch. Few

remembered him, but many of his sayings and doings were still

current among the people who dwelt in that valley, and of him it

might be said that though dead he was not forgotten. When

living, he was of an original type — hard, shrewd, persistent.

Permitting no nay, he was never known to withdraw his word, hating

idleness, and being the sworn foe of drink. It was his boast

that he never re-engaged a discharged hand; when once notice was

given, no matter whether by operative or master, the consequence was

irrevocable; the door was shut, and bolted with a bar of steel.

It was in recalling this feature of the old master’s character that

my companion declared that ‘jackasses an’ women weren’t in it.’

‘Why jackasses and women?’ I asked.

‘Well, it’s i’ this road, yo’ see. Yo’ con leather a

jackass, an’ yo’ con please a woman; but th’ owd gaffer yo’ could

neither drive nor lead. He’d nobbud go one gate, an’ that were

his own. Aw’ve heard men curse him, an’ aw’ve seen women wi’

tear i’ their een, go on their knees to him; but neither t’one nor

t’other moved him — he were as firm as th’ engine bed yonder, an’ as

hard an’ all. They used to co’ him “Owd Gibraltar,” becose he

were like a rock. But he were once licked, an’ it were by a

woman an’ all.’

‘By his wife?’ I asked.

‘Partly what an’ partly not,’ said old Harry. ‘His

missus were i’ th’ job, but there were another woman wi’ her; an’ th’

two o’ them were more nor he could face. It were nobbud once,

aw tell yo’; but it were enough; an’ ever sin’ aw’ve awlus said aw’d

back woman’s wit agen th’ world.’

There now followed one of those tantalising pauses which it

was always fatal to interrupt. The sun was dying behind the

moors, and the tints on the factory windows paling before the

approaching gloom. The children were scampering to their

homes, and the voices of the day retreating before the silence of

the nightfall. The waters at our feet took a more sullen hue,

and a chill air sweeping from the hills, drove our steps towards the

old man’s shrine of labour. We climbed the stone stairway that

led into the engine-house, and seated ourselves once more before

that ponderous mass of steel, now silent, and shadowy beneath the

twinkling gaslight that dimly illumined the room.

I often wondered how it was that Harry was more voluble in

the presence of his engine. It seemed to me that it was his

inspiration — a recaller of forgotten incidents and restorer of

bygone memories. What the grove was to the Academician, and

what the laboratory to the scientist, such this engine-house was to

the old son of toil, whose life, even to its pulse-beat, was

incorporated with the engine’s movement and work. Its very

motion gave momentum to his mind, while the roar was music, and the

pause provocative of the past.

‘Aw were sayin’ that th’ owd maister were nobbud o’erfaced

bud once, an’ then it were by a woman. Hoo were a woman an’ no

mistak’, a woman wi’ a will an’ a way o’ her own; and hoo were th’

wife o’ a chap as we co’ed Sossin’ Simon. Yo’ know what sossin’

means? It means a chap ’at laps drink as a cat laps milk.

An’ Simon were a lapper an’ all; he’d a tongue as dry as a new-brunt

brick, an’ a throttle like a sough. Nowt come amiss to him,

fro’ traycle-beer to owd four-penny, though he stuck to the latter

when it come i’ his gate. He spent so mich time i’ th’ ale-haase

that once o’er he were welly sold for one o’ th’ fixtures, an’ he

lost so mich time o’er his wark that if he hadn’t been th’ best

weyver i’ th’ shade, he’d ha’ got th’ sack long afore he did.

‘One mornin’ th’ owd maister come into th’ shade an’ axed th’

overlooker where Simon were; an’ when he telled him he were at th’

“Sheaf an’ Sickle,” he went straight across th’ road an’ took th’

bull by th’ horns, for all he were i’ th’ tap-room wi’ his cronies

raand him. “This is noan weyvin’, Simon,” he said.

“Nowe, maister, aw were nobbud wambly (weakly or unsteady) this

mornin’, an’ as aw didn’t want to spoil yore warps aw thought aw’d

just fortify mysel’ wi’ a pint.” “That tale willn’t do, lad,”

said th’ gaffer; “if thaa’s ill thaa mun bring a doctor’s certihcate,

an’ then thaa con play till thaa’rt better.” An’ he marched

him off towards th’ shade.

‘On th’ road he talked to him like for his good, an’ telled

him there were no sense i’ bein’ a berm-yed (ale drinker), an’ haa,

if he didn’t mend, he’d sack him; “an’ thaa knows,” said he, “if

thaa’rt once sacked thaa’s sacked for good.” Then Simon telled

him as haa he suffered fro’ th’ dithers, a complaint ’at nowt but a

stimulant would cure. “All reet,” says th’ gaffer; “next time

thaa ails aught thaa’s nowt to do but bring a doctor’s certificate,

an’ aw’ll see that nowt happens thee.”

‘Well, Simon were a daycent lad for welly six months; but

when Kesmas come he went on th’ spree, an’ kept on’t for aboon three

week. All th’ time he were off his wark th’ owd gaffer kept

quiet; but th’ mornin’ he turned up he sent for Si’, as we used to

co’ him, into th’ office, an’ axed him to give an acaant o’ hissel’.

“Aw’ve none been so well, maister,” said Simon. “Hasto brought

thy certificate,” he axed; “for if thaa hasn’t thaa works no more

for me.” “Yi, aw’ve brought th’ certificate; it’s here, sithee,”

an’ he poo’ed th’ doctor’s paper aat o’ his pocket, an’ handed it

with a regular baance to th’ maister.

‘As yo’ may suppose th’ gaffer were takken aback. At

first he thought it were a lark, but he soon seed it were jannock.

To mak’ sure on’t, haaever, he put on his glasses, an’ then he brast

aat laughin’, for what he read were:—

‘“This is to certify that Simon — is suffering from chronic

alcoholism.”

‘“Thaa’s done me one this time, Simon,” said the gaffer; “go

an’ get on wi’ thy wark, thy looms are waitin’ for thee.”’

‘But where did the woman come in?’ I asked; somewhat

surprised at what I took to be the climax of the story, yet none the

less relishing the joke.

‘Howd on a bit,’ said Harry, ‘we hav’n’t getten to her yet.

Afore many weeks were over Simon were at his drinkin’ again, but th’

owd gaffer were true to his word, an’ everybody knew as haa he would

keep it.

‘It were a long, hard spring that year, th’ yest wind were

never tired o’ blowin’, an’ snow fell at Whissuntide. Coiles

were scarce, an’ flaar were dear, for th’ times were bad, an’ them

as hadn’t mich were hard put to’t. Trade were bad wi’

everybody but publicans. Aw durnd know haa it is, but folk con

awlus find brass for drink; onyroad Simon did, an’ poor Hephzibah

were terribly ooined (punished) o’er it an’ all. Fro’ th’

first thing i’ th’ mornin’ till th’ last thing at neet he were

stretchin’ his feet under th’ tap-room table, while th’ haase were

left to go to rack and ruin. Bit by bit th’ furniture went to

th’ pawn shop, an’ that ’at didn’t were takken for th’ rent.

Not but what Hephzibah were a gradely weyver hersel’, an’ able to

earn a good wage, but hoo were expectin’ her first child an’ were

past warkin’; an’ if hoo had worked he’d nobbud ha’ swallowed her

brass. One neet, haaever, when he come home, he fun her on th’

floor i’ a deead faint, an’ like as that sobered him. He

raised her yed, but he’d nowt to put it on, for th’ haase were as

bare as th’ palm o’ yore hand. He looked raand to give her

summat to sup, but there weren’t a glass or pot he could lay howd

on. There hoo were, poor lass, her bonny een closed, an her

face all marred wi’ want, an’ noabry at hand to help her, but Simon

who were just gettin’ sober wi’ his fright. It were a neet an’

no mistak’. Th’ wind whistled under th’ threshold, an’ th’

only leet were fro’ th’ moon which were at full. But there’s

awlus summat turns up, an’ while he were tryin’ to lift her yed a

naybor come in, an’ they carried Hephzibah next door where there

were a fire an’ summat warm.

‘Some women’s like cats,’ continued Harry, after a

pause,‘they’ve nine lives; an’ Hephzibah were one o’ that breed, for

aw met her i’ th’ mornin’ goin’ to th’ factory to see if hoo could

persuade th’ owd gaffer to give her husband another try.

‘Thaa’s on a fool’s errand,’ aw said, ‘thaa’d best save thy

legs an’ thy breath, thaa’s none fit i’ thy state to go an’ upset

thysel’ wi’ a row wi’ owd Jonas abaat a waistrel like yore Si’.

‘Then she telled me haa he’d getten th’ owd family Bible ’at

were his mother’s, an’ oppened it, an’ kissed it on his knees, an’

towd th’ Almeety as haa he would be damned if he’d ever touch

another drop o’ drink. “An’ he meeans it,” hoo said, “an’ aw’m

baan to ax th’ gaffer to give him another trial.” “Save thy

breath an’ save thy legs,” aw says, “for he willn’t listen to thee.”

But it were no use, hoo’d have her way.

‘Aw were i’ th’ factory yard when hoo met him. “Well,

Hephzibah,” he says, “what doesta want? Is there owt aw con do

for yo’,” for hoo were a woman he awlus respected. “Yi,” hoo

says, “aw want yo’ to give aar Simon another try.”

‘“Aw thought yo’ hadn’t known me twenty years for nowt,

Hephzibah,” he says.

‘“Nowe, maister,” hoo says, “aw havn’t; an’ its becose aw

know there’s so mich good abaat yo’ aw’ve come to yo’.”

‘“Hephzibah,” he says, “my word’s my bond.”

‘“But supposin’ thaa does more good by breakin’ thy bond nor

keepin’ it.”

‘“Aw’ll tak’ th’ consequences of that, Hephzibah.”

‘Then hoo towd him as haa Simon had sworn on his mother’s

Bible never to touch another drop o’ drink, an’ haa he meant to turn

o’er a new leaf an’ be a daycent husband an’ a better workman.

But it were all no use, an’ th’ gaffer waved his hand an says, “Aw

con do nowt for thee, nor for him noather, for that matter.”

‘Then hoo touched him on th’ shoulder an’ says, “There’s

sombry else thaa con do summat for. Thaa knows aw’m near my

trouble, an’ a week’s wage’ll happen save another life besides

mine.”

‘Hoo telled me at after haa hoo shamed as hoo spoke i’ this

fashion. “But thaa knows, Harry,” hoo said, “th’ mother geet

th’ better part o’ th’ woman an’ th’ wife. It were noather my

felley no mysel’ aw were pleadin’ for, but th’ little un ’at were on

th’ road.”’

I was struck with the deep pathos of the story, and felt that

while there might be a coarseness about it unknown in the more

conventional circles of life, yet after all it was rich with the

plea of nature, a true note, perhaps rudely struck, in the poetry of

life.

‘The master granted the woman’s request, I suppose!’ I said,

anticipating, as I thought, the end of the old man’s story.

‘Nay, he were noan of that sort. For all that he put

his hand i’ his pocket an’ fotched aat a couple o’ suvverins, an’

telled her that would see her o’er her trouble. But hoo

wouldn’t have ’em, an’ telled him as no brass should go into their

haase ’at wernd worked for. Then he telled her he’d done all

as he could for her but break his word, an’ that he said he’d do

noather for her nor any other woman.

‘Then like as Hephzibah broke daan, an’ wipin’ th’ corner o’

her een wi’ her apron, hoo turned aat o’ th’ factory yard a brokken-hearted

lass.

‘As hoo were comin’ away hoo met owd Betty Pickup.

“What ails thee, lass?” hoo said. An’ when Hephzibah telled

her tale th’ owd woman said, “Thaa mun see his wife.”

‘At first Hephzibah wouldn’t hear on’t, but th’ owd woman

kept at her, an’ hoo had her reasons, for th’ gaffer’s wife were

what Hephzibah co’ed “near her trouble” an’ all. When Betty

whispered this i’ th’ lass’s ear, an’ telled her ’at there were

times when th’ rich an’ poor were noan so different fro’ one

another, an’ had a sort o’ felley-feeling, Hephzibah made up her

mind hoo’d go to th’ Hall an’ see if th’ gaffer’s missus could do

owt i’ gettin’ Simon back to wark.

‘Naa th’ gaffer had nobbud been wed abaat twelve months, an’

his wife, who were a lady born, were only weakly. Hoo were th’

very sunleet o’ his life; an’ there were as said he gathered th’

daisies i’th’ meadows as hoo trod on. Th’ servants used to

tell as haa he couldn’t say her nay. Onyroad, hoo were th’

gaffer up at th’ Hall whoever might be at th’ factory. Yo’ con

understand haa he were anxious abaat her, an’ did all he could to

please her, never lettin’ any trouble light i’ her road if he could

help it; an’ yo’ may be sure ’at if he’d known Hephzibah were baan

to’ th’ Hall, he would ha’ stopped her, even if he’d fotched th’

perlice to her. But then yo’ see he didn’t know — an’ there

hangs my tale.

‘Aw heard Hephzibah tell haa hoo donned hersel’ up i’ th’

bits o’ things ’at hadn’t gone to th’ pawnshop, an’ went wi’ a lump

i’ her throat an’ lead at her heels up th’ road to th’ Hall.

Aw’ve heard her tell haa hoo went to th’ back door, an’ rung at th’

big bell, an’ telled th’ servants haa hoo wanted to speak to th’

missus. But it were th’ servants theirsel’s who telled haa

they met each other, an’ what they said to each other, for there’s

naught tak’s place i’ a rich man’s haase but th’ servants know.’

Here the old man fell into one of his musing fits, removing

his cap and wiping his brow with his wad of cotton waste, his pipe

for the time being laid on the chest whereon we sat. Suddenly

taking his eye from the silent engine on which he had been looking,

he turned towards me and said:—

‘Aw’ll tell yo’ what, though women’s terribly jealous o’ one

another, there’s times i’ their lives when they remember nowt but

each other’s troubles.

‘They say at first ’at th’ gaffer’s wife would hear nowt

abaat oather th’ factory or Simon gettin’ sacked, tellin’ Hephzibah

all th’ time that hoo’d nowt to do wi’ what her maister did at th’

mill, an’ that hoo never meant to. But when Hephzibah began to

fiddle on th’ string ’at touched th’ tender place i’ her heart, an’

telled her as haa th’ little heir they were expectin’ at th’ Hall

would find its head pillowed i’ down, while that i’ th’ cottage

would find no restin’ place but a half-clemmed bowsom, they say th’

gaffer’s wife fair broke daan, an’ said as haa hoo’d see as noather

th’ mother nor th’ child wanted for nowt.

‘Then it were as Hephzibah stretched hersel’ up, her rags

showin’ her breast as hoo hadn’t clooathes to cover. “Yo’re

very kind,” hoo says, “but it’s noan charity aw’m axin’ for, an’

it’s noan charity aw’ll tak.’ Yo’ con get my maister set agate

if yo’ve a mind to. Yo’ve nobbud to raise yore finger an’ it’s

done. It’ll nobbud be a day or two, an’ yo’ an’ me’ll have to

go through th’ mill together, an’ we shall happen both get dusted;

but yo’ll be all th’ easier i’ yore pain when yo’ remember yo’ve

done summat to lessen mine.”

‘But th’ little woman were firm, an’ said as haa her maister

knew his business best, an’ hoo were noan baan to meddle wi’ it.

Then Hephzibah towd her there’s some things ’at women understand

better nor men. But th’ gaffer’s wife never spoke.

‘Aw believe it were a feyght wi’ th’ maister’s wife, for they

say as haa hoo poo’ed aat her handkercher an’ wiped her een.

Aw could like to ha’ seen ’em, rags an’ riches, both waitin’ for

their haar o’ sorrow to strike. They say ’at a fat sorrow’s

better nor a lean un, an’ happen it is; but there’s some doors ’at

both rich an’ poor have to go through, an’ they’re very narrow ones

an’ all. An’ this were a narrow one ’at these women had getten

to, an’ noabry knew it better nor theirsel’s.

‘Haa it would ha’ ended, aw durnd know; but th’ servants as

were spyin’ telled as haa Hephzibah went daan on her knees, an’

said: —

‘“For th’ sake o’ th’ child yo’re bearin’, tak’ pity on

mine.”’

It was not often that old Harry betrayed feeling, and seldom

had I seen a tremor cross his lean, firm-set face. But the

narration of this story, and especially its climax, had touched the

nether springs hidden away in the deeps of this rough product of

manufacturing life. His voice grew thick, and with a rude

excuse, he left me to look after some trilling detail belonging to

his engine.

On his return the spasm of sympathy was passed; he was old

Harry once more, hard and cold as the steely monster he tended; and

when I asked him as to the fate of Simon and Hephzibah, he told me

how that on the morning following the pleadings of the weaver’s

wife, Simon was running his looms, and that he continued so to do

until the day of his death, keeping faithfully to the vow which he

had breathed over the old Bible, wherein, as the engineer said, the

name of a little Hephzibah had been inscribed, the silent pleadings

of whose unconscious life bent the will, and gainsayed the word of

one who, in Harry’s words, was ‘as firm as th’ engine bed an’ as

hard an’ all.’

――――♦――――

NO PLACE FOR REPENTANCE

‘AW welly think

hoo’s th’ most unhappy woman i’ th’ parish, an’ that’s sayin’ a

deal, for there’s some weary (sad) uns, aw con tell yo’.’

‘She looks it,’ was my reply; ‘yet why she should, I can’t

imagine, for she seems to have all that heart can wish.’

‘Nay, noabry has that — not them as has th’ most.

There’s awlus a float or a mash i’ yor piece, or summat,’ said the

old engineer, falling back for illustration on factory phraseology

and figure. ‘Th’ richest have a hoile i’ their purse, an’ them

as drinks th’ sweetest cup find it smacks o’ gall. Aw know

there’s aboon a few looks at yon wi’ envious een; bud they durnd

know what hoo carries; it’s th’ owd sayin’ o’er agen, an’ it seems

fresher every time yo’ say it, “Th’ heart knows its own bitterness,”

— an’ there’s some bitterness in hers an’ no mistak’.’

She of whom we were speaking was one of the steadiest and

most skilful of the old weavers in the factory’s employ, and one of

the most thrifty too. She was far past middle-age and

unmarried, and, to all appearance, well-to-do, and living in a

cottage of her own. Silent and self-contained, she seemed to

follow her work without either the love or hate of friend or foe, a

dull and settled sorrow clouding her eyes, and a dispirited air

clothing her like the desolation of an autumn day. Soon after

my sojourn in the village I had singled her out from among the

operatives as they hurried to and from their work, she, the while,

neither pairing nor hurrying with the crowd, but walking slowly and

alone. I often wondered what unkindly fate had crossed her

path, and what, and from where, fell the perpetual shadow beneath

which she seemed to dwell. Indeed, I vexed myself as to her

fate, and as to the history of despair that was writ so large on

every feature of her face.

My chance of inquiry without undue curiosity soon came; for

one afternoon, as I stood talking with old Harry in the factory

yard, she passed us on her way to the warehouse, and it was in reply

to my question that the old man declared his belief that she was

‘th’ unhappiest woman i’ th’ parish.’

‘Another story, Harry, I suppose?’ I said.

‘Yi, an’ a sad one an’ o’ — as sad as ony aw’ve told yo’.

There is some nuts as is hard to crack; an’ when aw think of yon

woman aw’m in a quandary. Aw sometimes wonder if the law of

God will let her off as easy as th’ law of th’ land! Hoo

carries a curse abaat wi’ her, does yon. An’ yet, aw durnd

know! It’s every one for hissel’ an’ hersel’, isn’t it?

An’ yet, it’s nobbud reyt ’at first come should be first sarved.

Bud if th’ strong push th’ weak ’at’s afore ’em aat o’ th’ gate, an’

ged their share, what do yo’ co’ ’em?’

‘Thieves and robbers,’ I replied.

‘An’ what do yo’ do wi’ em?’

‘Give them what they ask for, or let them take it,’ I

laughed.

‘Yi, that’s it. Yo’ know it’s robbery, bud then yo’

treat ’em like honest folk.’

I was lost to know what the old man meant, and failed to

construe his reasoning so as to interpret the character of the woman

that had so perplexed me, and about which I was anxious for further

light. However, I was to be perplexed still more, for with his

next breath he continued:— ‘If it had nobbud been a case of robbery,

it would ha’ been different; bud them as is aboon sees blood on yon

lass’s heart, if they see noan on her honds!’

‘Then she’s shadowed by a tragedy?’ I said.

‘That’s givin’ it one of yore fine names ’at comes of bein’

larned,’ he replied. ‘Aw co’ it summat else, shuzhaa’ (right

or wrong).

‘You don’t mean to say the woman has been guilty of taking

the life of one of her kind?’ I exclaimed.

‘Aw meean to say if hoo’d done reyt hoo’d ha’ been deead long

sin’; an’ them as is deead would ha’ been alive an’ weel naa, plez

God. Bud, as aw towd yo’, th’ nut’s hard to crack.

Happen aw should ha’ done th’ same as hoo did; bud that doesn’t mak’

ony difference to her. We’ve all to carry aar dirty honds

afore Him as is clean an’ just;’ and for once the old man fell into

religious mood.

It was with anxiety I awaited the clue to this perplexing

epilogue, which I knew would come in the form of story; and it was

with fear I anticipated one of those interruptions which, when they

came, so disastrously destroyed the spell of the narrator.

Fortune was favourable, however; for, turning towards me, old Harry

said:—

‘Aw mun tell yo’ th’ tale, for aw see yo’ con mak’ nowt of an

old man’s maunderin’s. Come along i’ th’ boiler-haase, an’

when aw’ve shut off th’ steam yo’ shall yer all.’

In a little while, when the machinery was at rest and the

sound of clogs had died away on the pavement, Harry came out of the

engine-house, and sat beside me on the rough improvised bench

whereon I had heard so many of his stories both grave and gay.

Lighting his pipe, and musing amid the blue wreaths of smoke

that ascended therefrom, he slowly and in subdued voice said:—

‘There’s nowt oather i’ earth or hell to match a jealous

woman, for hoo’s noather conscience nor heart. Hoo’ll say

aught, an’ hoo’ll do aught — hoo will, for sure. It’s bad

enoof when hoo’s jealous of a felley; bud when hoo’s jealous of her

own kind it’s war to th’ knife, an’ knife to th’ hilt, an’ th’ hilt

i’ th’ part ’at tak’s longest to heal. Th’ bitterest things

aw’ve ever yerd aw’ve yerd fro’ a jealous woman; an’ they con be as

cruel as Turks. As th’ Methodys say i’ their prayers — there’s

noather “hope nor mercy” abaat ’em. Nay, aw welly think as

haive th’ mischief i’ the world comes fro’ jealous women.’

The old man’s sudden and unexpected tirade was not lost on

me, for it lifted the cloud that hid the secret of the life of the

woman whose lot had been a problem beyond my solution; and in her I

now began to see a wreck wrought by jealousy, and became all the

more expectant.

‘When two lasses love th’ same lad,’ the old man continued,

‘they hate each other as mich as they love him they’ve set their

hearts on; for, as yo’ know, love an’ hate is noan far apart — they

light their kindlin’ at th’ same fire. Durnd yo’ think so?’

I nodded my assent, and in my own mind silently complimented

Harry on his shrewd observance and wisdom.

‘Well,’ he continued, ‘yon lass an’ Clara Robison both set

theirsel’s to marry Jimmy Rothwell, an’ at first he were noan

pertickler which on ’em it were, so he left ’em to settle it between

theirsel’s. Naa, this were fool’s wark, for he might ha’ known

’at‘ he could ha’ settled th’ job wi’ th’ least trouble; bud he were

one of th’ yessy sort, leavin’ things to tak’ their chonce.

‘As yo’ may suppose, it weren’t long before there were bad

blood between ’em; an’ it showed itsel’ an’ o’; yon lass as we’ve

just passed i’ th’ factory yard sayin’ all as hoo could agen Clara,

an’ Clara bein’ noan slow to say all as hoo could agen her. Th’

worst on’t were, they wove at th’ side of one another, an’ Jimmy

were th’ tackler. There were some marlocks, aw con tell yo’,

for both th’ lasses were of th’ feightin’ breed. Them as

looked on had th’ best on’t, as they awlus have, for that matter;

and there were aboon a few laid their money as to which would be th’

winner.

‘Sometimes Jimmy walked wi’ t’one an’ sometimes wi’ t’other;

bud whichever he walked wi’ he were forced to yer all that were bad

abaat her as were left awhom. There were some folk ’at said it

were a wonder he didn’t sack ’em both wi’ yerin’ so mich that were

bad abaat both; bud like as he believed noather on ’em, for he kept

on keepin’ company wi’ ’em like a chap ’at didn’t know his mind.

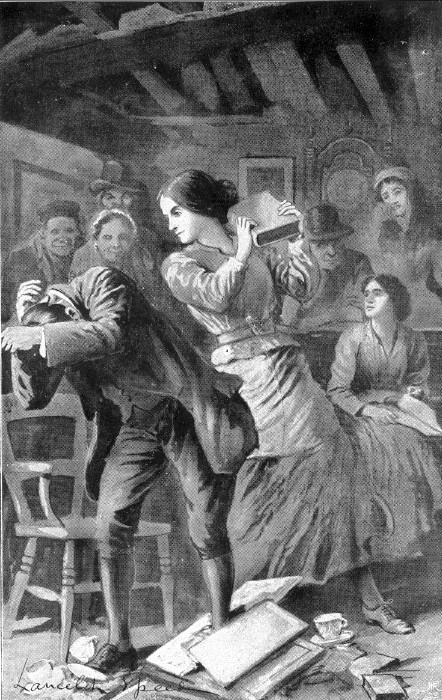

‘One afternoon they geet to poo’in’ one another’s yure i’ th’

weyvin’-shade, yon lass tellin’ him to his face that he favoured

Clara, an’ Clara co’in’ her names ’at were noan perlite. Aw

pitied th’ lasses, bud aw pitied noan o’ him; for a chap as cornd

mak’ up his mind where lasses is consarned desarves none; an’ if th’

punishment that follered had come on noabry else bud hissel’ aw

shouldn’d ha’ minded; bud, as yo’ll yer, it come on ’em all three.

‘Have yo’ never noticed,’ asked the old man, ‘that like as

Providence, or summat, has a way of sattlin’ th’ jobes ’at we oather

cannot or willn’t sattle for aarsel’s? Onyroad, it were so wi’

Jimmy, for what he ought to ha’ done hissel’ were done for him; an’

he soon fun’ aat which on ’em it were he wanted; bud he fun’ it aat

when it were too lat’.

‘Th’ owd mill were stonnin’ i’ those days, an’ th’ weyvin’-shade

where the lasses worked were on th’ basement floor, abaat six feet

below th’ level of th’ roadway. There were an area raand it

fenced off wi’ iron rails agen which th’ childer used to lean an’

look at th’ looms, and felleys short of wit coome an’ gloor through

the winders at th’ weyvers. It were a cold damp hoile, an’

welly sent as mony as worked i’ it to th’ doctor’s as it sent pieces

to Manchester.’

I was amused with the old man’s exaggeration, and ventured to

correct him by asking how they managed to carry on any work at all

with such a loss of time and labour.

‘Aw could like yo’ to ha’ seen th’ owd shop,’ said he, ‘then

yo’d ha’ some idea of th’ places folk worked in forty year sin’.

They were smithies, an’ no mistak’ — reyt enoof for them as run ’em,

bud murder for them as worked i’ ’em. Brass were turned aat i’

barrowloads for th’ maisters i’ those days, bud nobbud i’ spoonfuls

for th’ honds, an’ th’ spoons never ran o’er. Th’ owd mill as

used to ston’ here were five storys hee, an’ full of little winders

filled in wi’ iron frames as yo’ couldn’t open, th’ bays between ’em

bellyin’ aat like th’ calves of a chap i’ knee-breeches. There

weren’t a room i’ it as yo’ couldn’t touch th’ ceilin’ wi’ yore

lingers when yo’ stood on th’ floor wi’ yore toes — that is, if

yo’re ony height. An’ what were more, yo’ were oather sweat

aat or frozen aat, an’ yo’ couldn’t draw yore breath for “fly”

(refuse of the cotton). Bud like as th’ owd folk took to’t,

an’ there were some warchin’ hearts when it fell to th’ graand.’

‘It was not destroyed by fire, then?’ I asked.

‘Nay, it tumbled in of itsel’. It were like a mony poor

folk — they worked it to deeath, an’ there were aboon a two-thre

died wi’ it.

‘It were i’ this road,’ said the old man, drawing steadily at

his pipe—‘they took to fillin’ it wi’ new machinery. There

were some as said th’ walls would never ston’ th’ strain, nor th’

floors noather, for that matter; bud there were them as said they

would; so as th’ doctors differed they sent for a chap fro’

Manchester as put his nose into every nook, an’ did a deal of

examinin’ abaat th’ beams an’ walls, an’ then pronaanced it safe.

Bud, as yo’ll yer, it were a case of puttin’ new wine into owd

bottles, an’ them as did it ne’er forgave theirsel’s.

‘Aw used to help th’ mechanics to ged th’ machinery up i’ my

spare time, an’ th’ more aw knew of th’ strength an’ power on’t, th’

more aw blamed th’ folly o’ fixin’ it i’ such a ramshackle hoile;

an’ aboon once aw telled th’ manager my mind; but he nobbud laughed,

an’ telled me my mind were to mind my own bisness. “It’s all

reyt,” aw says, “bud yo’ll find that oather yo’, or th’ gaffer, or

sombry else, will have more on yore honds than yo’ con ged off wi’

swop an’ watter.” But he said aw were a foo’, and telled me to

go to th’ shop ’at were hotter than th’ one i’ which aw worked.

‘Well, th’ fixin’ of th’ machinery were a slow job, for there

were a deal of manoevourin’ to ged all th’ frames in, an’ very

little room were left for th’ honds to work in. Th’ mornin’

afore we were ready for startin,’ one of th’ maisters said to me,

“Harry, it’s a mistak’; there aught to ha’ been a new factory for th’

new tackle.”

‘Aw were fair on a thremble when aw started th’ engine i’ th’

mornin’, for like as aw knew summat were baan to happen. Not

as aw believe i’ what yo’ co’ presentiments — aw ne’er had no time

to do that; but aw couldn’t ged it off my mind as there were

mischief abaat. Aw remember haa aw kept my een on th’ swaybeam,

an’ watched th’ fly-spur as th’ speed geet on’t, an’ haa aw

hearkened to th’ machinery through th’ wall, expectin’ all th’ while

a catastrophe. But all went on reyt, an’ as my nerve come back

aw knocked abaat my wark as aw were used to.

‘Just afore th’ dinner-haar, as aw were crossin’ th’ factory

yard, aw yerd a smashin’ o’ glass, as though sombry were breakin’ th’

winders. “What’s yon?” aw says, as aw looked i’ th’ direction

o’ th’ saand. Bud aw soon seed, for one o’ th’ bays were

swayin’ aat, an’ it took me all my time to keep mysel’ fro’ geddin’

buried under it as it fell to th’ graand.

‘Aw’d seen th’ inside of a factory mony a time, but aw’d

never seen it fro’ th’ aatside afore. There were th’ ends of

th’ floorin’ just on th’ totter where th’ walls had left ’em, wi’

shaftin’ still runnin’. Then come th’ smash, th’ machinery

fallin’ an’ crushin’ th’ felleys an’ lasses, while th’ gearin’ an’

beltin’ geet howd on ’em an’ fair rove ’em like rags. When th’

dust had cleared off a bit, an’ th’ buildin’ had sattled itsel’, an’

yo’ could tak’ in th’ measure of th’ mischief, yo’ seed a seet ’at

would ha’ sickened th’ een of one o’ th’ carrion ’at gathers where

th’ carcase is. A bit aboon where aw stood were an arm as

seemed to be feightin’ fro’ under a beam, bud nowt were seen of her

as moved it. Then aw geet a glint of a clog at th’ end of a

leg ’at were smashed by a length o’ shaftin’. Then aw clapped

my een on a lot o’ long red yure tangled wi’ some weft, but th’ face

weren’t i’ seet, an’ when it were, them as seed it were quick to

cover it o’er. One poor lass were spiked wi’ a rod — pinned

daan wi’ th’ iron through her like a bagonet. Mony as weren’t

hurt, an’ were buried i’ th’ ruins, made th’ air ring wi’ their

cries to be takken aat; th’ felleys facin’ th’ Almeety wi’ curses,

while th’ lasses were co’in’ on th’ Saviour to have mercy on their

souls. There were one little un, abaat six year owd, wedged i’

one o’ th’ frames, cryin’ for it mother, while hoo, poor thing, all

th’ while were lyin’ wi’ her neck brokken under a beam as had fallen

fro’ th’ floor aboon. It were th’ first time aw’d seen a

gradely feight between flesh an’ blood an’ stones an’ iron; bud

stones an’ iron were th’ maisters, for th’ poor crayters had no

chance at all;’ and the old man held his hand before his eyes, as

though he would fain dim the sight of that awful morning.

After a lengthened pause he continued: ‘As yo’ may suppose,

it were aboon a bit afore us ’at were aatside poo’ed aarsel’s

together; bud once we geet agate we made up for lost time, an’ there

were soon plenty of willin’ honds to help i’ fotchin’ aat th’ deead

an’ th’ dyin’. Aw’d been at wark skiftin’ an’ liftin’ an’

carryin’ for over an haar, when Jimmy come up an’ axed me if aw’d

seen aught of th’ lasses — meaning them as he kept company wi’.

“Nay,” aw says, “aw’ve been o’ this side all th’ time; if thaa wants

them, thaa’lt ha’ to ged in among the looms fro’ th’ back.”

An’ to th’ back we both on us started.

‘When we geet there th’ passage were craaded wi’ folk lookin’

for their own; but Jim an’ me pushed aar way among th’ ruins till we

come to a beam as had part fallen, wi’ a length of floorin’ hangin’

o’er it, an’ blockin’ th’ way. “Aw’m for geddin’ o’er,” he

turned raand an’ shaated. “An’ aw’m for ‘follerin’,” aw said;

an’ i’ less time nor it tak’s to tell we were on t’other side.

‘As soon as aw leeted an’ looked raand aw wished aw were back

agen. Th’ whole o’ th’ factory seemed to be jammed into th’

basement where th’ looms were. Yo’ never seed such a ruck i’

yore life, an’ noabry else, for that matter noather. Th’

pillars were knocked o’er like ninepins, an’ th’ beams smashed like

carrots, an’ all maks thrown topsy-turvy — brokken wheels, twisted

shaftin’, knotted belts, an’ riven warps, mixed up ony road an’

every road, while some o’ th’ weyvers, poor lasses, were underneath

it all. “First come, first sarved?” aw axed Jim. “Yi,”

he said, “it’ll be like to be, though aw fain could save Clara;” an’

we both on us set to wark wi’ a will.

“Hoo’s comin’ aat,’ he said, ‘or aw’m stoppin’ in.’”

‘I’ a bit we geet aat two of th’ lasses ’at were nobbud badly

scratched, then we poo’ed aat one ’at were deead; an’ we should ha’

managed two-thre more if it hadn’t been for th’ ruins takkin’ fire,

through th’ gas ’at had been left lighted i’ th’ under-manager’s

office. It were just like spark an’ paader, touch an’ go;

first yo’ smelt it, then yo’ seed it, and afore yo’ could turn raand

yo’ felt it on yore flesh.

‘“Sithee, Harry,” shaated Jimmy, just as we were baan to turn

an’ run, “yon’s Clara.” And there hoo were, lyin’ flat under a

loom, an’ doin’ all hoo could to poo’ hersel’ aat. “Is there

time, think yo’?” aw axed, for the fire were leapin’ like th’ wind.

“Hoo’s comin’ aat,” he said, “or aw’m stoppin’ in;” an’ he set off,

an’ me after him, to save th’ girl.

‘Bud there were two on ’em, — Clara an’ her rival — an’ when

we’d poo’ed her aat as we thought were Clara, th’ three on us blind

wi’ smoke an’ scorched wi’ flame, we fun’ aat it were Clara we’d

left behind. Then it were as Jimmy lost his yed, an’ would ha

rushed back into th’ flame if folk would ha’ let him.’

‘And how was it,’ I asked, ‘that you missed Clara?’

‘Nay,’ said the old man, ‘there’s nobbud one can tell yo’

that, an’ hoo’s th’ woman we’re talkin’ abaat. When Jimmy come

raand he crossed th’ seas an’ left her, as hoo desarved. There

is as puts two an’ two together an’ adds up th’ total, an’ it’s not

a creditable one oather. All aw know is as yon woman’s never

smiled sin’; an’ though hoo says her prayers, an’ goes to th’

chapel, an’ gie’s her brass to th’ heathens, hoo’d ha’ better ha’

perished i’ th’ flames nor carry abaat wi’ her a sin, which, if it’s

forgiven, hoo con none forget.’

――――♦――――

THE BATTLE ON THE SIZE-HOUSE FLOOR

|

This story, which has neither point nor

pathos, preserves a type of Lancashire life which is now

fortunately altogether a thing of the past. I give

it as it was told to me somewhere about twenty-five

years ago, and by one who as devoutly believed in its

truth as he believed in his own consciousness. The

artistic value is nil, but to those who care to

know what Lancashire was before the days of School

Boards, it is a relic worthy of preservation. |

IT was a heap of

crumbling walls and rotting rafters, damp with ooze and stained with

streaks of repulsive slime. From the paneless windows the

spider spun his web; and the battered door, hanging from its rusted

hinge, flapped like the wing of ill-omened bird. The floor was

littered with the refuse of bygone labours — broken troughs and

frames, with remnants of mouldy warps, lying in forgotten confusion,

and telling of long abandonment and disuse.

It stood at the farther end of the factory yard where no

sunlight fell, and where the air was chill on the warmest hours of

summer noon. Around it the wind seemed never weary — it was as

though the burden of the village sorrow found there a shrine of

desolation whereat to plaintively outpour its tale of woe.

Never saw I a sparrow settle on the sagging eaves, nor cat clamber

over the ruined walls. Children, too, shunned it in their

hours of play; and few of the operatives cared to pass it when the

fall of night gave to it more gruesome shade. There it stood,

sombre and forbidding, as though each stone were imbrued with the

stain of some past sin — a heap of desolation, a monument of shame.

The first time I ventured to survey its domains I selected an

hour when my curiosity would be unobserved by the eye of the

operatives. The engines had stopped, and the hum of labour

ceased. The last clink of the iron clogs was dying away on the

distant pavements; and a faint cloud of steam, issuing from the

boiler-house, drew a thin curtain of light across the gathering

gloom. Twice or thrice I looked round to see if my steps were

noticed; for I feared the prying eye more than the ghostly ruin I

was about in secret to explore. But shadow or footfall there

was none. I was alone. Once within its portal I pushed

aside the door, the timbers striking an uncanny chill to my touch.

Then my foot slipped on the refuse which lay thick over the

threshold; and a sudden resolve seized me to retrace my steps.

Curiosity, however, got the better of my superstition, and with

renewed courage I determinately walked within.

Looking round, I saw little else than four ruined walls

ridged with rafters, now bare save where roofed by patches of slates

and rags of plaster. The paneless windows glowered in the

gathering gloom; and the fragments of warps on the floor lay like

reptiles in their slime. Old instruments of labour were

scattered around as though mocking the dead hands of those who once

had been their masters; while the silence seemed to tell of long

years past since the sound of labour had echoed there. As I

surveyed the scene a raindrop fell through the open roof and the

overhanging trees moved as if in disquiet at my intrusion on the sad

spot over which they cast their protective gloom.

Lost as I was in brooding thoughts, it was with a startled

sense I heard a voice break in upon the stillness: ‘Naa, thaa’rt

speirin’, aw see.’ And looking round I discovered the presence

of old Harry within the ruined door.

Continuing, he said: ‘Thaa’rt on forbidden graand, thaa

knows. There’s not mony on ’em would care to be rootin’ where

thaa’rt — not after neetfo’ onyroad.’

‘I am doing no harm,’ I replied; — ‘up to no “marlocks,” as

you would say. It would take a cleverer man than either of us

to do much mischief here.’ And I tapped the crumbling walls

and the accumulated rubbish with my stick, and laughed.

‘It’s been th’ playgraand for mischief long enough,’ said he;

‘an’ th’ tale it con tell is as dark as itsel’. Aw wonder th’

gaffers let it stand as long as they do! But then it would

cost brass to poo’ it daan; an’ it’s given o’er botherin’ folk sin’

they’ve built another size-haase — that is, if they keep aat o’ its

gate.’

‘And if they get into its gate,’ I said; ‘what then?’

‘If they’re wise they’ll get aat on’t as fast as they con, as

yo’ an’ me’s baan to.’ And so saying he laid his hand upon my

shoulder, and led me into the factory yard.

We walked towards the engine-house where, on entering, the

old man struck a match, and lighted a jet of gas, bidding me be

seated, and composing himself in oracular fashion for what I felt

was to be a weird story.

Jerking his thumb across his shoulder in the direction of the

old size-house we had just left, he said, ‘It’s aboon twenty year

sin’ him ’at worked yonder poo’d his last warp. But like as he

connot sattle, an’ he still haunts th’ owd shop, cursin’ th’ Almeety

as he used to when he had breeath. Everybody were freetened on

him when he were alive; but they’re a deeal more freetened on him

naa he’s deead, yo’ bet.’ And the old man threw a glance over

his shoulder, as though in fear of being heard by some avenging

eavesdroppers from another world.

‘Come, Harry,’ I laughed, ‘you are not of the stuff out of

which they manufacture superstitious minds.’ But he took

little heed of my remark, and continued:—

‘There’s things i’ this world that’s close akin to things i’

t’ other — things that ’ill plague a wise mon like yoresel’ if yo’

mak’ up yore mind to maister ’em.’ Then, once more jerking his

thumb over his shoulder, he wound up this bit of philosophy by

saying — ‘an’ that’s one, yonder.’

He paused, and I was silent. I thought the great engine

took a gloomier form, and cast more gruesome shadows. The

spell of an unbroken stillness rested upon us, and I looked on the

grim profile of this hard-headed, yet none the less superstitious,

son of toil, as his face was thrown into relief by the feeble glare

of the luminous jet.

Lowering his voice to a hoarse whisper, he said, ‘There were

as telled as haa he’d a quarrel wi’ th’ Almeety; an’ aw welly think

it were so, for he were nobbud reet but when he were cursin’ Him.

Aw’ve heard them as could swear, an’ aw con do a bit mysel’ when

aw’m i’ th’ mind; but th’ owd sizer were th’ most terrible tongued

chap aw ever knew. He were awlus shappin’ new oaths, an’ he

awlus shapped ’em for th’ benefit o’ Him ’at’s aboon. There

were one oath ’at were awlus on his lips;’ and once more the old man

looked fearsomely over his shoulder. Seeing nothing, however,

he put his mouth close to my ear and whispered, ‘it were this — “Th’

Lord stiffen me.”’

I confess old Harry’s manner, as well as the spirit of his

story, somewhat unstrung my nerves, and I began to wish I had

allowed my curiosity to lie dormant. It was not, however, for

me now to take the backward step, but to follow him through the maze

and mystery into which he had led me; or, to be more correct, into

which I had led myself.

‘There were some things,’ continued Harry, ‘th’ owd sizer

couldn’t ston’. One were th’ singin’ o’ hymns. One

mornin’ as a weyver lass passed th’ size-haase dur wi’ a bit o’ a

song on her lips abaat “th’ nearer waters rollin’,” he run aat an’

cursed her, an’ telled her he’d have no, — Methody melody sung abaat

his shop. It were th’ same wi’ childer. He couldn’t bear

th’ seet on ’em; an’ aw welly think if he’d had his own way he’d ha’

been like owd Herod an’ ha’ had ’em all killed.

‘One neet, when he had a leet burnin’, one o’ th’ chaps as

had had a sup o’ drink crept up to th’ owd size-haase, aat o’

curiosity like, to see what were goin’ on. As he come back aw

met him, his knees wobblin’ an’ his teeth chatterin’; an’ when aw

axed him what were up, he telled me to go arf look for mysel.’

‘And did you go?’ I inquired.

‘Forsure aw did,’ said the old man, with tremulous voice and

perspiring brow.

‘And what did you see?’

‘Aw seed two pieces o’ wood shapped like a cross, set up i’

th’ corner o’ th’ hoile, an’ him cursin’ it, an’ slatterin’ it wi’

size.’ Then looking up at me with awed glance he said: ‘A chap

cornd do wur nor that, con he?’

‘The man was a maniac,’ was my comment.

‘Nowe,’ said old Harry; ‘he were possessed.’

‘Did he drink?’

‘Nay, he were teetotal — as daycent a chap as ever walked as

far as keepin’ hissel’ steady an doin’ his work were concarned; but

awlus feigh’tin’ th’ Almeety.

‘One day owd Enos, th’ Methody, stopped him, an’ telled him

it were ill-luck for a chap as strove wi’ his Maker. “It’s

ill-luck for him as strives wi’ me,” he shaated; an’ seizin’ th’ owd

chap by th’ scruff o’ his neck, he flung him aat o’ his gate.

They gave o’er tryin’ to get him convarted after that, an’ yo’ll not

wonder.’

‘And what was his history?’ I asked.

‘Nay, yo’ ax me what aw connot tell yo’. There were as

said ’at afore he come i’ these parts he’d buried both his wife an’

child, an’ lost his bit o’ brass i’ speculation like mony a fool

afore him. Happen it were this as set him agen th’ Almeety;

aw’ve heard on’t doin’ so afore. But like i’ a bit folk geet

used to him, an’ left him alone; an’ th’ maisters axed no questions,

for he sarved their purpose, an’ th’ weyvers had naught to say agen

their warps. But he were feightin’ a loisin’ game; an’ one

neet i’ th’ “Sheaf an’ Sickle,” when they were talkin’ abaat him,

owd Jerry, who were a bit o’ a sportsman, said he’d lay his money he

were baan to be licked. An’ he were reet. As th’ months

passed o’er, his yure began a-turnin’ grey, an’ his chops took th’

colour o’ ith’ size he worked in. Then he started a bein’

slamp an’ wambly (thin and shaky). But he were gam’ for all

that.

‘One neet th’ watchman seed a leet i’ the size-haase.

At first he took no heed to’t, for there were times when the sizer

stopped lat’; an’, what were more, he were none particular abaat

botherin’ wi’ him. But as he went his raands the leet kept

burnin’ till at last he fell unyessy like, an’ wondered if aught

were wrang. Not likin’ to go by hissel’ he fotched a bobby,

an’ th’ two on ’em together crept up to see what th’ marlock were.

‘Afore they geet to th’ dur they heard th’ sizer cursin’ an’

swearin’ as though he were vomitin’ aat hell. This poo’ed ’em

up, t’one wantin’ t’other to go first, th’ bobby sayin’ he could

face a drunken felley an’ midneet burglar, but haa his truncheon an’

bracelets were no use i’ th’ case o’ sperrits.

‘Onyroad, i’ a bit they managed it atween ’em, th’ watchman

peepin’ through th’ key-hoile, an’ th’ bobby dodgin’ raand th’

windows to where he could get a sken. They telled after haa th’

sizer were feightin’ summat they couldn’t see. He seed it,

haaever, an’ no mistak’, an’ struck aat straight fro’ th’ shoulder,

gettin’ badly punished hissel’. Haa long th’ feight continued

they could never tell, for they were too taken up wi’ it to keep

caant o’ th’ minutes. Onyroad, it were give an’ tak’, an’

fought i’ one raand, for there were no stoppin’ for breath.

When th’ sizer fun’ aat he were gettin’ th’ worst on’t he seemed to

loise his head an’ let drive harder nor ever, an’ wi’ his tung an’

all, till th’ watchman’s an’ th’ bobby’s marrer fair froze wi’ th’

oaths they heard. It fair capped ’em, they said at after, to

know what schoo’ he’d been to to get such larnin’. Aat they

come, hot an’ fast, like coils when yo’re drawin’ yore fires, an’

all agen Him as is aboon. Then drawin’ hissel’ up, they telled

haa he hissed out th’ owd oath; an’ it welly seemed as if th’ Lord

took him at his word, for he threw up his arms an’ fell amang th’

size, an’ never spoke at after.

‘As yo’ may suppose, there were an inquest, an’ th’ crowner

were inclined to be awkward o’er th’ tale th’ two felleys told.

But they were no shakin’ ’em, they both stuck to their text, so they

browt it in as a case o’ temporary insanity — an’ infusion, or

summut on th’ brain.

‘When they come to layin’ him away there were a deeal o’ talk

abaat his past doin’s; an’ there were as said as th’ curse o’ th’

Almeety had been on him. Happen it were so, an’ happen it

weren’t; it’s none for th’ likes o’ me to say. Onyroad, when

th’ time come for th’ screwin’ daan o’ th’ cofhn there were none as

would do it, thinkin’ as th’ further they were off th’ safer it were

for ’em.

‘Aw’se never forget it. We all sat as gawmless as

nicked geese raand th’ kitchen table, none on us carin’ to go up to

th’ chamber where he were laid aat. Aw never seed such a

regiment o’ bleached faces afore i’ my life. Th’ pipestems

fair chattered atween aar teeth, an’ we supped aboon aar share o’

drink. As for talkin’, there weren’t a word said, an’ th’

haase were as still as a churchyard at midneet when th’ wind’s gone

to sleep.

‘Th’ time crept on, but there were none as shifted.

“Th’ berrin’s at three,” said one on ’em, “an’ it nobbud wants ten

minutes to th’ haar;” but noabry said naught, an’ everybody looked

on th’ floor. “Wilta go an’ screw him daan, Harry?” axed

Jerry. “Nay,” aw said, “aw’d rather be excused; aw’m not mysel’

this afternoon?” “Wilta, Jerry?” said th’ watchman ’at had

seen th’ sizer die. But he nobbud shook his yed, an’ said he

were nobbud slack set up; an’ he took a long poo at th’ ale jug.

“Fotch in th’ landlord,” suggested one o’ th’ mourners, “he’s a

nerve for aught; like as he con hondle deead folk, whatever sort

they be.” So they fotched him.

‘He come in wipin’ his maath wi’ his apron, for, as he telled

us at after, he fun’ it necessary to fortify hissel’ for th’ job.

‘“Naa then, lads,” he said, “aw’m ready if yo’ are. Yo’

munnot keep th’ parson waitin’, yo’ know. Who’s baan to go i’

th’ chamber wi’ me?” But there were none on us responded to

his invitation; an’ we sat smokin’ on, an’ lookin’ at th’ floor.

“Dun yo’ think aw’m goin’ upstairs by mysel’?” he shaated, layin’

the screwdriver on th’ table. An’ it welly seemed as if he’d

have to, for aar feet were as quiet as aar tongues. “Surely yo’

religious folk are none feeared,” he said; “yo’ sing loud enough up

at th’ chapel yon, abaat ‘devils fleein’ an’ flyin’.’ Come naa,

back up yore faith by works.”

‘Then two on ’em ’at were “leaders” up at th’ Chapel, plucked

up an’ said, “Go on, landlord, we’ll follow thee;” an’ th’ three

went up th’ staircase like chaps as were steppin’ to th’ Deead March

i’ Saul.

‘They seemed a terrible time o’er th’ job; an’ all th’ while

they were screwin’ him daan we could yer th’ prayers o’ th’ leaders

an’ th’ cursin’s o’ th’ landlord feightin’ t’one agen t’other.

But like a deeal o’ other things, both better an’ wurr, it were o’er

wi’ at last, an’ when they geet th’ corpse to th’ bottom o’ th’

stairs all three on ’em looked as though gowd wouldn’t fotch ’em to

do th’ job a second time.

‘So that was the end of the sizer, was it?’ I said, somewhat

shocked with the old man’s blunt realism; though he told his story

with an unconscious reverence and awesome superstition, which

redeemed it from what a stranger would have deemed vulgarity.

‘Nay,’ replied the old man, ‘it were noan his end.

He’ll never be laid, th’ sizer willn’t, till they poo daan yon hoile

i’ th’ yard.’ And once more he jerked his thumb in the

direction of the ruin where the man accursed had been wont to

labour.

‘Then there’s a story of the sizer dead, as well as the sizer

living?’

Harry shook his head. ‘Nowe,’ said he, ‘yo’re off it.

Th’ sizer’s more gradely wick naa nor ever he were. Folk gave

him elbow room when he were i’ th’ flesh; but they’re a vast sight

more feeard o’ him naa nor they were then. Yo’re laughin’, aw

see. Weel, aw’ve heard ’em say ’at eddication mak’s wise men

o’ fools; but aw’se like to be content wi’ th’ owd school.

Aw’m nobbud tellin’ yo’ what aw know, an’ what folk abaat here

believe; an’ yo’ve axed me for’t.’

‘Never mind what they believe; let me hear what you know, for

one witness is worth much hearsay.’

‘Nay, aw’m noan baan to tell th’ likes o’ yo’ what aw know;

aw’m noan forgetful what th’ owd Book says abaat pearls an’ pigs,

an’ it’s a case o’ pearls an pigs when yo’ start tellin’ a chap what

he willn’t believe.’ And the old man relapsed into a sullen

mood of silence in which I joined.

In a little while, however, he found his speech and

continued:—

‘Like as he couldn’t let them as followed him on th’ job

alone; he were oather awlus spillin’ their size or marrin’ their

warps; onyroad, they said it were him. One thing were certain,

it were noan th’ sizers, for we geet some o’ th’ best i’ th’ caanty.

But like as there were summat agen all on ’em, an’ some were sacked,

an’ them as wirnd gave in their notice.

‘One afternoon, just as th’ dark were fallin’, him as were

sizin’ come across to th’ engine-haase an’ says, “Harry, owd lad,

yo’re noan a white-plucked un.” “Nay, aw durnd know as aw am,”

aw says. “Then come wi’ me to th’ size-hoile, an’ thaa’ll see

summat.”

‘As we were baan he telled me haa he’d left th’ shop abaat an

haar ago all reet an’ tidy, an’ haa when he come back he fun’

there’d been th’ ferrups to play. “’Sithee for thysel’,” said

he, throwin’ oppen th’ dur; an’ as th’ Lord’s aboon, th’ place were

topsy-turvy. Th’ size were spilt, an’ th’ warps were twisted,

an’ th’ frames banged abaat as though they’d been th’ playthings o’

a giant.’

‘“Naa then, what doesta think o’ that?” he axed. “Nay,

Bill,” aw says, “it’s aboon my wit.” “Thy wit or onybody

else’s wit,” he shaated; “th’ dule’s i’ th’ shop, an’ ’aw’m off.”

And slipping on his coat he showed his heels, an’ aw followed.

‘Weel, it were th’ same wi’ th’ chap as come after him.

He hadn’t been there so long afore he towd th’ same tale; an’ when

he gave in his notice he telled th’ maisters he mun ha’ a bigger

wage if he were to feight th’ dule as weel as poo warps.

‘One mornin’, a bit at after, th’ young maister come to me:

“Harry,” he says, “what’s this aw yer abaat th’ size-haase.”

“Nay,” aw says, “durnd ax me; the size-house is noan my shop.

Yo’ mun ax them as works there.” “That’s what aw have done,”

he says, “an’ they talk like foo’s. We used to have th’ best

warps i’ th’ valley, an’ naa we cornd get one as weyves reet.

Th’ owd hoile seems cursed.“ “Yo’ have it naa,” aw says.

“Have what?” he axed. “Th’ secret o’ th’ whole marlock.

Yo’ con seck flesh an’ blood, but there’s no seckin’ a speerit; an’

him ’at used to work there for yo’ works there agen yo’, naa.

Th’ only way to lay him is to poo th’ shop daan abaat his yers.”

“E’ Harry,” he says, “aw thought thaa’d more sense.”

‘Onyroad, i’ a bit he come raand to my way o’ thinkin’; an’

when they built a new size-haase th’ work began agoin’ on as usual.

Like as th’ owd felley sattled when they left him to hissel’.

Naa then, yo’ve heard my tale, what dun yo’ think on it?’

‘That a generation of School Boards will remove all such

beliefs;’ and as I said this I saw a shadow fall across the old

man’s face.

‘Yi,’ he said, ‘pigs an’ pearls, as aw told yo’, aw were a

foo’ for ever startin’ o’ my tale. Yo’re a chap as is larned

up, an’ aw’m a chap as they say knows naught; but aw know what aw

knows for all that, an’ it’ll tak’ a better mon nor yo’ to mak’ me

believe it’s a lie.’

That night as the moon, filling the factory yard, threw the

many-storied shrine of labour into relief, and lit up with pale

reflection the long rows of serried windows, I walked once more

across to where, in unrelieved shadow, the ruins of the old

size-house stood. The sagging roof, rent and gappy, the

bulging walls half-rased to the ground, the flapping door moving to

and fro as though releasing the haunting spirits of the past — these

wore a weird complexion, the more so for the strange associations of

the old man’s tale. As I looked and listened, the faint moan

of the burdened wind fell upon my ear, while the rustle of the

overhanging trees seemed to whisper of the secrets of the past, the

drip of the water from the adjoining lodge the while falling as the

tear of some unspoken woe. Was it to be wondered that I felt

the sense of that other world of which we know so little, and yet of

which we cannot break the spell, and that as I walked home my

thoughts were with the rude operative who felt the touch of a

mystery which it were wiser to confess than deny.

――――♦――――

AGAINST THE DAY OF MY BURIAL

‘IF yo’ do aught that’s gradely, durnd yo’ think it caants wi’ th’ Almeety?’

It was Harry who put the question to me as we sat together in the

factory yard one Sunday afternoon in June. Around lay the hush of

almost universal quiet, for the ponderous engine slept, and the

myriad iron-tongued machinery stood motionless and mute. The air,

too, was clear, for from the tall chimneys no smoke came, and the

sky was bright with the reflected smile of a valley at rest. On

distant hills scattered groups of loiterers told of welcome respite

from sore labour’s hours, while a dreamy hum seemed to echo the

quiet of the day.

Within a stone’s throw from where we sat was a knot of

Salvationists, their voices alternating between song and speech,

distance toning the one into sweetness and the other into utterance

broken and indistinct. There was, despite the ‘tow-row’ of the

tambourine, a plaintive tone in the deep bass of the men and the

sweet treble of the girls, each burdened with its sad notes of

earnestness. I saw the old man was a listener, for, with head bent

forward and ear on the strain, the rigid muscles of his face relaxed

as some sound or sentiment was swept towards him on the wind. Not

that he held anything in common with either the speakers or their

theme — his religion was of another order. But, as he used to say,

‘There were good among all sorts, an’ he were noan pertickler who it