|

Condition of the people before 1850.

CHAPTER I.

THE first half of

the Nineteenth Century was a time of great hardship for the working

classes. The prolonged conflict with Napoleon ended in 1815 with

victory for England, but peace brought little relief to her

over-burdened toilers.

The history of the years from 1815 to 1845 is a continuous record of

distress, periods of scarcity and consequent privation, fluctuating

prices alternately starving labourers and ruining farmers, bread

riots and disturbances, and in manufactures uncertainty and loss.

For this state of things the heavy taxation due to the Napoleonic

War was partly responsible; the frequent occurrence of bad harvests

was another cause. But ill-regulated industrial changes, and a

commercial policy ill suited to the country and the times, and not

the war or the niggardliness of Nature was the root of the mischief.

In the Eighteenth Century, after England had gained possession of

extensive Colonies, and had secured a practical monopoly of the

trade with India, the demand for manufactured goods could not be met

by means of the primitive machinery then in use; and soon, in

consequence of the pressure put upon those engaged in her

manufactures, there came a long series of great inventions, by which

the productive capacity of English manufactures was enormously

increased. Industrial methods and conditions were completely

revolutionised; England became a manufacturing instead of an

agricultural nation; and the workers were drawn from the country

districts and massed together in towns, where population

increased with unprecedented rapidity. Factories superseded the

old domestic workshop; the capitalist employer took the place of

the old master-workman; the domestic worker, who had once not been far removed in station from his employer, became the

factory “hand,” and between the people of this class and

the capitalist there was seldom any bond other than a cash

payment.

So swift was the transformation of industry, and so fully

occupied was the Government with other and more imperative —

though scarcely more important — matters, that the change was

allowed to proceed without regulation. Inevitably, therefore,

much mischief was wrought.

The conditions of labour in many of the factories were

unspeakably bad; in nearly all they were of such at nature as

to endanger the health of the workers. Hours were long, the

buildings were insanitary, the machinery was unguarded. The

Factory Acts were not very stringent, and even had they been

better, the staff

of Inspectors was so inadequate that evasion of the law was

a very simple matter. The first ray of light came in with

the strengthening of the Acts in 1844. Evil conditions within the factories, the workshops, the mines, and other places of labour

were well-matched by the insanitary homes of a large proportion

of the town population, and the towns had grown so rapidly,

and the Municipal Authorities in most instances were so

inexperienced — if not also incompetent and corrupt — that little

or nothing was done to ensure due regard to the health of the

people. Houses overcrowded, jerry-built on the banks of streams

fouled by the refuse of works and all manner of domestic filth,

streets and courts unpaved and undrained — such were the

surroundings in which many, perhaps the majority, of town workers

were condemned to dwell.

Agricultural labourers suffered also, though in a different

way. In agriculture as in manufactures new methods had been

introduced, which called for large capital. Small owners

unable to compete successfully with the new style of farmers were

obliged to sell their land; some degenerated into farm labourers,

or drifted into the towns, to intensify the competition amongst the

wage earners there. The agricultural labourer, moreover,

lost heavily by the enclosure of common lands, where he had once

been able to feed his cow or his pig, and until 1834 he was degraded

by a vicious Poor Law.

The evils associated with these industrial changes were intensified

by other conditions. Imports were checked by Customs duties, which,

in many cases were so heavy as to be prohibitive. The most obnoxious

of them all was the duty on foreign corn, which, without serving the

end for which it was said to be imposed, viz.: ― the encouragement of

the English farmer — inflicted intense suffering on the wage

earners, by raising the cost of food; nor was this the only

ill-effect. The exclusion of

foreign goods, and particularly of foreign corn, restricted the

market for English manufacturers; for the foreigner could not buy

our manufactures because we would not take the only payment he could

offer — the produce of his farm, of his sugar plantation, or of his

forest lands. Our industries were disturbed by frequent stoppages

and violent fluctuations of prices. The price of food was high and

the wages of the workers were low and irregular.

The distress was exceptionally severe between 1837 and 1842. In

these years the wages of agricultural labourers was often as low as

7/- per week. In the manufacturing districts many of the mills were

stopped, and many more were working little time, and the amount of

pauperism was appalling. In Manchester, we are told, 116 mills and

many of the works were stopped, 2,000 families were so reduced that

they had to pawn even their beds, 12,000 families were receiving

poor relief, and thousands subsisted on charity. Out of 50 mills in

Bolton 30 were idle, and 6,995 persons whose average earnings were

only 1/1 per week were aided in one month by the Poor Protection

Society. In Nottingham 10,580 persons were receiving poor relief. In

Leeds 21,000 persons were earning on an average 11¾d. per week. In

Stockport so many firms had failed that work had practically ceased,

and multitudes earned less than 10d. a week. Bury, Rochdale, and

many other towns had a similar record of failure and distress. While

the working classes were on the verge of starvation, British corn

was 65/- a quarter, and the duty on foreign wheat was 24/8 per

quarter.

To meet the great distress in Bury a fund was started, called “The

Bury Loyal Relief Fund.” The movement originated in a desire to

celebrate with local rejoicings the birth of a male heir to the

throne — his present Majesty King Edward VII. It was at the

suggestion of the late Rev. Franklin Howorth, who was the wrong type

of man to fiddle when Rome was in flames, that the decision was

arrived at to use the money subscribed for the relief of distress

rather than for merry-making.

The committee felt it their duty to make the many subscribers

acquainted with the manner in which they had dealt with the monies

entrusted to their charge. To accomplish this object a meeting was

called on the 20th November, 1841, at which the Rector of Bury

presided. It was reported that £1,500 had been collected and placed

at the disposal of the committee.

The condition of the working classes of the town may easily he

gathered from the following abstract from the report: — “In

distributing this relief your committee were anxious to combine

liberality with caution. To assist their labours two persons were

employed as Inspectors, and by this means a careful enquiry was made

by actual inspection into the condition of the working classes, and

a record was furnished to the committee of the names, residences,

and occupations, the number of the family, &c. 1,157 families being

visited, consisting of 5,371 persons, of whom only 1,487 were at all

in work, and many of these only partially, and the average amount of

weekly earnings per head was found to he only 1/9¼.”

Some idea of the condition of the town may be gathered from the fact

that the committee of the local Relief Fund decided that families

which could show an income of 2/6 per head per week could not

receive relief. To those who were not in this state of comparative

affluence assistance was at once given in the shape of flour, meal,

and potatoes, also in blankets, sheets, calico, flannel and clogs,

and in this way there were relieved:—

|

Families |

Persons |

Average per family |

Average per

head |

| |

|

s.

d. |

s.

d. |

|

151 |

804 |

12 11¼ |

2

3¼ |

|

336 |

1914 |

9

5¼ |

1

7½ |

|

153 |

807 |

4

0½ |

0

5 |

|

116 |

301 |

2

4½ |

0 10½ |

|

173 |

549 |

nil |

nil |

The amount actually paid away was as follows:―

| |

£ |

s. |

d. |

|

In food |

338 |

17 |

0 |

|

» Clothing |

583 |

11 |

2 |

|

» Money |

74 |

17 |

0 |

|

» Sundries |

73 |

2 |

8 |

|

Balance left over |

459 |

15 |

8 |

| |

£1530 |

3 |

6 |

In consequence of the diminished demand for labour, and the very

high price of all kinds of provisions, the same committee were again

called together to a meeting at the Dispensary in January 1847, when

it was proved to their satisfaction that assistance was again

urgently needed. It was resolved to augment the balance left over

from the last meeting by another appeal. This second effort resulted

in £908 being placed at the committees disposal; and the money, with

the exception of £158, was spent in soup, bread, and other

necessaries.

The Secretaries to the fund were the Rev. H. C. Boutflower, Vicar of

St. John’s, and Head Master of the Grammar School; and the Rev.

Franklin Howorth, Minister at Bank Street Chapel. Messrs. John

Walker and Wm. Hutchinson were the Auditors.

The wage-earners suffered in yet another way; in many instances

their wages were paid in kind. This, of course, is tantamount to

saying that the Truck Act of 1831 was evaded. The workman was often

compelled to occupy a house owned by his employer, and to buy his

goods at a shop kept either by his employer or by an official of the

mill or works where he was employed. The result was that he

generally got the worst goods at the highest prices. Worse still, he

ceased to be a free man. He was often in debt, and the owners of

“free shops” were compelled to give long credit ― a proceeding

injurious alike to buyer and seller. A local illustration will be of

interest here: In the Ramsbottom district only one mill was without

its “Tommy Shop” and in the village of Nuttall there was no

independent shop at all. In Bury itself the “Cottage System” was

general, and the “Tommy Shop” not uncommon.

The intense distress was attributed to this cause and to that, and

called forth many schemes of reform. The more ignorant among the

workers took violent measures. They smashed machinery, and burned

farms and ricks. The more thoughtful fondly believed that

Parliamentary Reform would enable them to set matters right. But the

Act of 1832 was far too modest a reform to satisfy those who had

clamoured for it. In plain English, they were bitterly disappointed

at it. The working men resumed their agitation. They demanded

opportunities of realising their position as citizens, and in many

parts of the country the dissatisfaction gave rise to the famous

Chartist movement. At one time this movement seemed likely to end in

revolution, but finally it was killed, in part by ridicule, but

mainly by returning prosperity.

Chief among the causes which led to its death was the triumph of the

Anti Corn-Law agitation. The repeal of the Corn Laws and the removal

of prohibitive imports generally opened foreign markets to our

manufacturers, checked violent fluctuations of prices, and gave the

workers more regular wages and cheaper food. The conditions of

labour were also much improved through the agency of beneficent

factory legislation. The Factory Acts passed between 1844 and 1852

incorporated many of the proposals which Robert Owen made many years

before, but which were then pronounced impracticable.

The teachings of Owen also gave rise to the Co-operative Movement,

the most practical of all the attempts made to improve the

conditions of the working classes, and in the long run the most

successful. The earliest experiments in co-operation made by the

disciples of Robert Owen failed through bad management and ignorance

of true economic principles. The Rochdale Pioneers, in 1844, avoided

the mistake which had proved so fatal to earlier attempts. Basing

their Society on broader democratic principles, they struggled

successfully through the many trials which beset the infancy of all

great movements, and thereby encouraged imitators in other towns. By

1851 there were no fewer than 130 “Stores” in England and Scotland. The motives and the cause of the new departure were well put by Mrs.

Webb in her admirable little book, “The Co-operative Movement in

Great Britain.” In some cases the Chartist Club became the Chartist

Shop. In other cases, such as Bacup, the Co-operative Association

arose out of an unsuccessful strike, during which the retail traders

sided with the masters and refused to allow credit, while a general

desire on the part of the factory hands to emancipate themselves

from the truck system, and the forced tenancy of masters’ cottages,

was an exciting cause of no mean strength. But viewed in its widest

aspect the rapid and successful establishment of Co-operative

Societies in certain districts was part of the general transference

of the spirit of association from a political into an industrial

form.

Can any of our readers wonder then, that under all these distressing

and discouraging conditions, a body of men should spring up who

would demand and work for a change. On the gradual decline of the

truck shop, or the “Tommy shop,” there sprang up in Bury a fresh

kind of shop, then known by the name of “Badger Shops.” The owners

of these badger shops, who allowed their customers to have goods on

credit for varying periods of time, were often of a keen and

exacting nature. The “badger business” was very profitable, and the

foundations of the fortunes of more than one family of note in Bury

were laid in that trade.

The system of continually being in debt was always repugnant to the

best of the sons of toil of that time, and many were the vows made

that they would extricate themselves at the earliest opportunity.

The only hope of escape from this for the majority lay in the

acceptance of the principles so strenuously advocated by stalwart

Robert Owen — the principles of associated effort; and although many

of the men had never known the value of capital, it was resolved to

make an effort, and the first form of co-operation in Bury starts

from this point.

They could not afford to stock a shop, and the first effort was to

get a week in advance instead of being so far behind. This object

accomplished, a few of the men would meet and arrange among

themselves what to purchase for the coming week; having decided this

momentous question one of their number would be appointed to buy the

articles required, the buyer sometimes going to Manchester,

sometimes to Bolton, and sometimes buying off some wholesale dealer

in Bury. The articles thus purchased were very limited in variety,

and were confined to the real necessaries of life. When the goods

were purchased, they were brought to the home of one of the number

and distributed, the cost of the transaction being arranged amongst

all concerned. This simple effort succeeded, thus presenting a

gleam of hope to the heavily burdened toilers of the town, the

principle began to be further discussed, and encouragement was held

out to others to take advantage of the opportunities which the

movement presented.

The advantages of the new system were many. There was the prospect

of being out of debt, the purchaser had the choice of quality and

purity, and the savings effected were considerable. These advantages

were not long in having their effect upon others, and small bands of

men organized with a similar purpose in view sprang up in several

parts of the town, until, between 1847 and 1850, there were about a

dozen organizations of people practising this kind of associated

effort or co-operation.

Thus was the first step taken towards Co-operation as we understand

it to-day, and from these modest beginnings we may trace the rise of

the great trading concern which now has branches in every part of

the town, and numbers among its adherents more than half the

householders in Bury. A great trading concern it is, but it is

something more. Its claims to respect lie not in the multitude of

its returns but in the amount of good it has accomplished. As a

social element making for improvement and increased happiness, and

as an educational force, it stands without a rival among the

agencies of which the nineteenth century, and more particularly the

Victorian era, has witnessed the birth and development. Of that

birth and development we shall have more to say in the chapters

which follow.

――――♦――――

The General Labour Redemption

Society.

CHAPTER II.

THE transition

from this elementary form of co-operation to one with a wider basis,

was both natural and beneficial. It was seen that if all these

various groups of working people could be got to join in one

organization a great economy would be effected, and there would be

some prospect of their ideas being developed to a much greater

extent, and so it came about that after some negotiation, an

arrangement was made to try to start a shop on a proper basis, and

on Saturday, September 16th, 1850, a Society was formed and styled

“The General Labour Redemption Society.” The shop at No. 50, Stanley

Street, was obtained, and was opened on October 20th, 1851. The

rental was £12 per annum, payable quarterly.

The objects of the Society were of a varied character, and reflected

great credit on the promoters. The first of these objects was to

invite labourers of every grade to join for the purpose of carrying

out and extending the practice of associated labour. It was proposed

to do this:―

(1) By forming working associations of men and women, who shall

enjoy among themselves the whole produce of their labour.

(2) By organizing both among such associations and any others of

combined workmen and capitalists, who may be admitted into the

Union, the interchange and distribution of commodities.

(3) By endeavouring to reduce the hours of labour.

(4) To purchase and cultivate land upon the co-operative principle,

to make provision for the education of children, and to provide for

the widows and orphans of deceased members of the Society.

The education imparted was to be of such at character as to render

its possessor a good member of society, understanding his rights,

and ready to discharge his duties, the right to live and the duty to

labour being considered fundamental.

The thirtieth rule says, “Co-operative stores or workshops shall be

established by the members in every town and village where a branch

of this Society many exist.”

The Society soon became prosperous, its membership being continually

increased, and its trade developing, and in order to celebrate its

success it was decided to hold a festival and invite some leaders

of co-operative thought to be present. The party was held in the

Town Hall, Bury, when upwards of 600 persons took tea together. The

meeting was crowded, and speeches were delivered by His Honour Judge

Hughes, Mr. Vansittart Neale, Rev. Charles Kingsley, and other

influential gentlemen. The proceedings were concluded by a

cheerful, merry dance.

At this time the Society had over 500 members on its books in Bury,

and its weekly receipts reached 250. Business went on smoothly for

a time, but a feeling of jealousy crept in, owing to the management

having failed to establish a proper system of keeping its accounts. This feeling of jealousy proved fatal to its welfare, and its trade

gradually dwindled away. The total trade done was about £1660. The

Society paid away £59 in dividend, and a bonus of 10,/- per share,

which took up £29 14s. 0d.

Mr. George Watson was first treasurer, and his successors in the

office were Mr. William Meadowcroft und Mr. Henry Roberts.

At the winding up of the Society the following item was posted:―

April 23rd, 1853, “To 2 trustees at 4/4½

each and one at 4/5, total 13/2, to 3 trustees for their extra

labour at various times previous to the store breaking up,—Timothy

Wilkins, Henry Roberts, and Hiram Ratcliffe.” The Society went out

of existence on April 3rd, 1854.

――――♦――――

The Rise of our own Society.

CHAPTER III.

AND now we come

to the formation of our own Society. The work accomplished by the

now defunct Society, the favourable impression it had left behind,

and the knowledge that had been gained as to where its weakness lay,

could hardly have failed to point to another effort to plant the

standard of Co-operation in Bury, as being likely to effect the

overthrow of many of the most formidable obstacles to the material,

moral, and intellectual advancement of the masses of the people. It

was customary at that time, as it is to-day, for a working man who

has a greenhouse and garden to be visited by a few comrades for the

purpose of talking over matters of local or general interest. One

Mr. Richard Sully, who had a garden and greenhouse at a place known

by the name of “Adam o’ Heywood’s,” on the south side of what is now

Heywood Street, was in the habit of receiving such visitors — men of

his own stamp, shrewd, intelligent, hard-headed workers. Not

only was the failure of the previous Society a subject for discussion at

these informal conferences, but that failure would be contrasted

with the reported success of similar efforts in Heywood, Middleton,

Rochdale, and other places, and it is easy to understand that these

reports would be listened to eagerly as the potting or grafting went

on. In the summer of 1855, there were about ten regular weekly attenders at Mr. Sully’s garden, and eventually it was agreed to

make an effort to establish a Co-operative Society. The effort was

made, and the result. was the formation of the “Bury District

Co-operative Society.” Thus was the old simile, “The gardener for

usefulness,” justified in a modern example, recalling the words that

Tennyson put into the mouth of Merlin, the sage:—

|

“I once was looking for a magic weed,

And found a fair young squire, who sat alone,

Had carved himself a knightly shield of wood,

And then was painting on it fancied arms,

Azure, an Eagle rising or, the Sun

In dexter chief; the scroll “I follow fame:”

And speaking not, but leaning over him,

I took his brush and blotted out the bird,

And made a Gardener putting in a graft,

With this for motto: ‘Rather use than fame.’

You should have seen him blush; but afterwards

He made a stalwart knight.” |

The enthusiastic gardeners who founded the Bury District

Co-operative Society were stalwart knights of industry who had

probably never blotted out from their scroll the words "I follow

fame,” but none the less they had adopted Merlin’s motto, and right

well they lived up to it, as the fifty years’ history of the Society

now testifies.

Having arrived at the decision to found a Society, the next

consideration was the raising of the requisite capital, and three

pence per week was the sum which it was agreed each person wishing

to assist and become a member should pay. Mr. Richard Sully was intrusted with the funds so raised. By the end of September of the

same year, finding the summerhouse getting too small for the members

congregating, and winter time approaching, it was decided to change

the place of meeting, and one of their number, Mr. John Mayor, of

Paradise Street, offered the use of his front room free of charge. This offer was accepted, and for a short time longer this small band

of pioneers continued to meet, pay their weekly subscriptions to the

treasurer, and discuss their chances of success or failure in the

art of shopkeeping. It was whilst in this house that they ventured

to make their first purchase — a very appropriate one — a load of

flour. This was bought from Mr. John Schofield, shopkeeper and

wholesale dealer, in Paradise Street. By the end of December the

capital account amounted to £6 9s. 6d., and the names of those who

had subscribed were Richard Sully, John Walmsley, Robert Austin,

James Carlton, James Wolstenholme, John Mayor, Edwin Barnes, Thomas

Clegg, John Muir, and George Raistrick. The trade done up to that

time was in the load of flour mentioned, for which £2 5s. 9d. was

paid. At this juncture a very important decision was arrived at. It

was pointed out that if the new venture was to succeed, its

conditions of membership must be opened as wide as possible,

consistent with reasonable security.

It was known to these men that in some previous efforts made in

various parts of the country the membership was confined to persons

holding certain political opinions, and that such actions had

resulted, if not in actual failure, in preventing that full

expansion and development that was so essential to complete success. And so it was decided at a very early stage of the Society’s history

that the membership should consist of all who chose to join, and who

were willing to work for the social welfare of the members; and that

no questions should be asked as to the opinions held on either

political or religious matters. The members were to be free to hold

whatever opinions they chose in matters religious, social, or

political, outside the domain of the Society; but inside they must

be Co-operators willing to work for the common weal. Another matter

they decided on was that when they began business they must not try

to undersell anybody else in the trade, but must see to buying pure

and wholesome foodstuffs, and sell them at reasonable prices.

It was about this time that a Mr. Smithson, of the firm of J. & J.

Smithson, of Halifax, was introduced to the pioneers of Bury

Co-operation. Mr. Smithson explained to the members that he had

heard about them, and desired, as an experienced person, to help

them. He told them they were adopting the correct principle by

starting in a small way. The taking of a shop required some little

courage, but after the inducements held out by Mr. Smithson that he

would supply them with a part of the goods required to stock a shop,

and wait for his money until they had drawn it over the counter, it

was resolved to make the plunge, and take a shop.

An opportunity soon presented itself for carrying out their ideas. No. 11, Market Street, being to let, negotiations were opened with

the owner, Mr. Thomas Rose. At this stage obstacles to continued

progress began to present themselves. The Co-operators were only a

small body of working men, enthusiastic about a new fad, and almost

without capital. Those who had not studied the question regarded the

Cooperative movement with a jealous and sometimes with a suspicious

eye. At first Mr. Rose hesitated to let the Society have the shop,

but ultimately he relented so far as to allow them to have the place

on lease for three years, at a rental of £31 per annum, the rent to

be paid quarterly. The members agreed to the conditions of tenancy,

and the first payment for rent was made on April 28th, 1856. Mr.

Smithson kept his word, and proved a good friend to the Co-operators

in their early struggles. He was not paid anything until March 11th,

when he received £20, a similar sum being paid him on April 8th, and

on May 6th they paid him £25. After this time they traded with him

on ordinary business lines. As amateurs at the work of furnishing a

shop, stocking it with goods, &c., their task was no light one, but

they had made up their minds to succeed, and they set to work

resolutely. At first the shop was open at nights, from 6 to 10

o’clock, the members arranging among themselves as to who should

attend to the cleaning of the place, the wrapping up of the goods,

and the actual work of serving at the counter.

As the subscribed capital only amounted at this time to £15, it is

clear that the work of furnishing the shop must have been on a very

limited scale. But the members were enthusiastic in their devotion

to the Co-operative ideal — limited as the conception of that ideal

must necessarily have been, and all were anxious to do what they

could for the success of the infant Society. Thus we find that many

of the articles required for use in the shop were willingly lent by

several of the members. Some found one thing and some another, and

thus the expenses of administration were kept down. Still many

things had to be bought, and although very essential and necessary

at that time, the mention of them may cause a little amusement

to-day. Amongst other things we find the following charges:— “Paid

for soap 4½d., brush 10d.,

spigot and focit 3d, candles 1d., writing paper 1d., twine 1½d.,

Epsom salts 1½d., coffee mill

15s., table 5s., butter knife 3½d.,”

and so on. The system of keeping an account of each member’s

purchases was very different to what it is now, there being at that

time no checks of either metal or paper, the principle being that

each member, on making a purchase, had it written down in a small

book, five inches long and two inches wide, containing 18 leaves, a

copy of which has been kindly lent to us by Mr. Lawrence Walker,

whose number in the Society then, as now, was 126. The name, ”Bury

Co-operative Stores,” was on the front page, the member’s name and

number following immediately under. When the purchase had been

effected, and entered in this little book, the member went to

another part of the shop, where another person was waiting to enter

the transaction into a general book, and at the close of each day’s

sales this book was taken upstairs, where the President and

Treasurer were in waiting to complete the matter by comparing the

amounts thus entered with the total cash drawn at the counter.

After at time this system was found to be inefficient, inasmuch as

it lent itself to inaccuracy and misunderstanding. A new system was

introduced, though at what date we are unable to say, but the

earliest mention of checks is in the September quarter of 1857. The

new checks for shillings and pence then introduced were made of tin,

and the pound checks of copper. The first date the word “shop” is

mentioned is on February 2nd, 1856, when the sum of £10 9s. 2d.

appears under the heading of “Receipts in Shop.”

The first week s business showed a turnover of £22 15s. 11d., and

during this time new members were being constantly enrolled. The new

system of shopkeeping formed the main theme of conversation amongst

the labouring classes in the town, and the interest taken in the

movement augured well for the success of the undertaking. The

question of how the business should be conducted now presented

itself. Many of the applicants for membership were heavily in debt

to some shopkeeper, and whilst wishful to join the new “Stores,”

were at the same time anxious to pay their just debts. Many were the

schemes proposed to accomplish this very difficult task, but the

general course adopted was to buy at the Stores and pay off their

old score with the dividends. When the question “Should we allow

credit to our members?” was asked, there was an emphatic “No” given

as the answer. “We’ve had enough o’ th’ badge-book,” was the reply

of one sturdy Co-operator. The decision not to give credit was in

itself honourable to the members, and showed that they had mastered

the first principle of Co-operation. Many of them had had bitter

experience of the hated badge-book, and their hope was that by the

new system they might replace it with a bank book. At the same time

it needed a great effort on the part of men accustomed to the credit

system to break away voluntarily from that system, and impose upon

themselves the onerous condition of always paying cash down. That

they were able to do it says much for their moral backbone. In the

early stages of the movement it must have been a test of exceptional

difficulty. Still the members fought nobly for the new principle,

and as time wore on its difficulties gradually disappeared with its

attendant evils of debt and dependence became a vanishing commodity

in the town.

It may be interesting at this point to say that, although the

Society was called the "Bury Co-operative Stores,” it could not

then, according to the ruling version of the law, trade in that

name, and it must have duly appointed trustees. The names of the

first trustees were Robert Law, Robert Austin, and Thomas Balmforth,

whilst George Raistrick allowed his name to be used as the trading

name of the Society. The Society traded under his name till April,

1859, and on the 26th of that month it was resolved by the members,

— “That in consequence of George Raistrick having withdrawn, our

trading name be ‘Raistrick & Co.’;” and on April 5th, 1862, the

trading name of the Society was again changed to “Sully & Co.,” and

the licence made out in that name.

On August 29th, 1861, the name of the Society was changed from “Bury

Co-operative Stores” to “The Bury District Co-operative Provision

Society,” and it was also decided that this name be placed over its

shops, and the word “Limited” added. The word “Provision” was

deleted from this name in 1904. Harking back to 1856, when the

Society had been at work in the actual distribution of goods about

five months, the question arose as to what system had best be

adopted to pay back to the members the balance of profit on the

Society’s transactions. Profits had been made, but so far none paid

away, and on July 19th, 1856, a deputation was sent to Rochdale with

a view of learning how their Rochdale comrades had met the

difficulty. Sufficient information seems to have been obtained by

the visit, for we find that in the month following the Society paid

away its first dividend, which amounted to a sum of £18 0s. 2d.

The constantly increasing trade of the Society, and the growing

difficulty of dealing with it all at nights only, compelled the

Committee to consider the advisability of opening the shop all the

day, like other grocers in the town, and of employing a shopman.

This they decided to do, and the following advertisement appeared in

the Bury Times for August 30th, 1856:—

BURY CO-OPERATIVE STORES,

11 MARKET STREET.

The Stores will be open Daily from 8 till

half-past 9. Saturday till 11.

Commencing this day, Saturday, Aug. 30th.

____________

The public will be supplied with articles of the

best quality at the most reasonable prices.

BY ORDER OF THE COMMITTEE.

Having now decided to open the shop daily (Sundays of course

excepted), the next step taken was to appoint a suitable person to

take charge, and one can easily imagine the consideration that this

change would cause. The business was altogether different from that

of any other shop in the town; the man appointed must thoroughly

understand the peculiar business, and also be in full sympathy with

the movement, besides having a knowledge of the ordinary

requirements of a shopman. It is not surprising to find that the

choice fell on one of their own number, Mr. Thomas Holroyd, a man

who had taken great interest in the Society’s welfare, and had

served in the shop at nights. His wages were fixed at 20/- per week,

and the first week’s wage was paid on September 5th, 1850. A boy

assistant, James Raistrick by name, was also appointed at a wage of

4/- per week. At this time there were 72 members on the books,

owning capital amounting to £162 12s. 0d., and the dividend paid was

1/3 in the pound on purchases.

It will be seen from what has been said, that the Bury Co-operators

adopted the Rochdale system of computing dividend, and the system is

similar in all respects to the one in force today. The road to this

system was therefore comparatively easy, but it was not so with the

Rochdale Pioneers, for we learn that they had been sorely troubled

for a considerable time as to what system to adopt for computing and

dividing their profits so to give satisfaction to all who were

interested in the movement, and deal justly with all the purchasers

in proportion to their purchases. Some years ago the story of how

the problem was overcome used to be told in Rochdale. The question

of the division of the profits had taxed the ingenuity of the

Pioneers for some time, until at last a Mr. Charles Howarth, who had

taken a leading part in the new movement, suddenly hit upon a

solution of their difficulty. It is said that after retiring to rest

one night he found himself unable to sleep, and while he was lying

awake a new thought entered and burnt itself into his mind. He rose

up in bed and shouted, “I’ve got it; I’ve got it.” The shout

disturbed very much the peaceful slumbers of his spouse, who jumped

up in bed and asked, “Got what? What has ta getten?” “How to pay the divi!” was the immediate reply. Mrs. Howarth, more matter-of-fact

than her partner, could not see the necessity for so much

disturbance in the dead of the night, and advised her enthusiastic

husband to lie down and keep his solution until the morning. This,

however, was just what Charles was unable to do. He would get up,

and get up he did, dressed himself, and went out to acquaint one of

his companions of his discovery. Uttering the same exclamation to

his friend, he began at once to explain his plan, which was to pay a

fixed rate of interest on the monies paid in as shares, the balance

left to be paid to the members in proportion to the amount expended. This principle seemed so just to the two concerned, that a meeting

was called the following night, and it was then and there agreed

upon that the system should be tried for a time. It was tried, and

proved so satisfactory in its trial that it was continued, and is

still in force.

From this time onward the developments of the Society were

remarkable in many ways. A few working people still looked upon it

with suspicion and prophesied its ultimate failure, but a far larger

number took a more favourable view of its objects and enrolled

themselves as members. The statement read out to the meeting at the

end of the March quarter of 1857 showed a membership of 154, and a

trade for the past quarter of £1,758, which was more than four times

the amount of the business done in the previous June quarter.

|

|

|

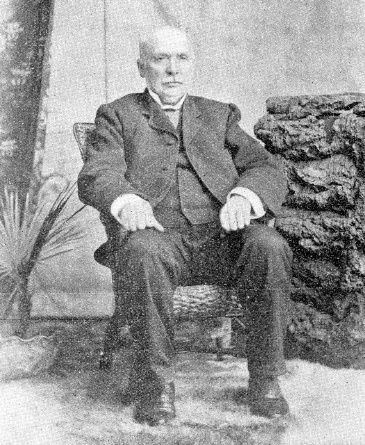

RICHARD SULLY

(One of the founder members of our

Society,

and the first Treasurer) |

At this time a demand was made for the Society to deal in goods

other than groceries, and arrangements were made with several

tradesmen in the town, as the first balance sheet shows, to enable

the members to purchase goods at their shops at the ordinary prices,

such purchases to be entitled to dividend as though they had been

made at the stores, the tradesmen making a corresponding allowance

in his bill.

For the quarter ending March, 1858, the balance sheet shows a trade

of £2,573, with a membership of 280 and a capital of £1,346, paying

a dividend of 1/3 in the pound on purchases. During this quarter the

Committee of Management desired to make an effort to become their

own landlords. This they proposed to do by undertaking the building

of two shops in Market Street, Nos. 17 and 19. The proposition gave

rise to a protest on the part of several members, who feared

difficulties on account of the youth of the movement, and the

smallness of the available capital. These Fearings of Co-operation,

who were not yet convinced that it had become a permanent part of

the fabric of English society, advised the members to wait a little

longer. On the other hand, the men of good courage, the

Great-hearts, if we may so term them, of the movement, who believed

in it to the uttermost, and perhaps foresaw much of its future, were

in favour of building. These men pointed out the vast strides

already made by the Society, and the benefits of employing the

capital in acquiring buildings of their own, and maintained that if

the members were loyal to the Society, both in their trade and with

their small items of capital, all would come right in the end. Their

advice prevailed, and although the capital at that time available

for building purposes only amounted to £908, the motion “That we

proceed to the erection of Nos. 17 and 19, Market Street,” was

carried.

Having received their instructions, the Committee of Management were

not long in getting to work. Land was taken, and the building

contract was let to Mr. Thomas Crossley, Mr. John Heap being

appointed clerk of works at 16/- per week. The first instalment of

£100 was paid to Mr. Crossley, when he had laid the first floor. This was on June 18th, 1858. The second instalment was paid on July

7th. Altogether the cost of these two shops, including furnishing

and fixtures, was £1,227, and so successful had been the appeal for

financial help at the beginning of operations, that, after paying

for the new buildings, no less than £1,180 left in the bank. It will

thus be seen that already Co-operation had done great things for the

people of Bury. The Committee at this interesting stage of the

Society‘s development were Thomas Baron Smith, Richard Sully, Robert

Law, Mark Rigby, George Yates, Joshua Proctor, Robert Austin,

William Tweedale, Robert Carter, James Holden, and Thomas Balmforth. Mr. Smith was the chairman.

Up to this time, the meetings of the members of the Society had been

held in the Athenæum, but after the building of these shops the

meetings were held in the new premises. The change was made on

November 6th, 1858, the chairman of this meeting being Mr. T. B.

Smith.

In September, 1858, a little trouble arose, through some

insinuations having been launched at the committee in reference to

the new buildings. The Society had had its troublesome member from

the first, and matters were pushed a little too far for the

committee at this particular time, as the following statement read

out to the meeting held on September 4th, 1858, shows:―

“To the members of the Co-operative Store Society;― We, your

committee, wish the members to express an opinion, in this meeting

assembled, on the conduct of the committee in reference to the new

buildings, and also on the insinuations that were thrown out at the

last monthly meeting in reference to their position (on having good

shops, and that they can’t be punched out of office). We, your

committee, are greatly dissatisfied at such language, inasmuch as

your committee have given their services gratuitously since the

commencement of the Society, and have endeavoured by all the means

in their power to benefit the Society, without fee or reward, and

have no other wish but to see the Society prosper, and that anything

derogatory to its interest shall be destroyed by the voice of the

members.

Thomas Baron Smith, President.”

After some little discussion it was resolved, “That this meeting is

perfectly satisfied with the present committee, and that this

meeting hereby expresses its continued confidence in their

endeavours for the Society’s welfare.” This resolution seems to have

had a good effect, for no unpleasantness of a similar nature is

recorded for many years after.

In January, 1859, the Society’s business was being conducted in the

new shop. They entered into the grocery shop first, the drapery

portion not being quite ready. In a very short time the change was

justified to all the members, the membership and trade developing

rapidly in the new buildings. The wisdom of the decision of the

members to build is proved by the following extract from the Balance

Sheet for March, 1859:—

"In presenting this quarter’s report, the committee have great

pleasure in directing the attention of members to the highly

satisfactory progression of the Society. During the quarter 150 new

members have been entered on the books, making a total of 550. The

amount received for goods from various departments is £4,293 13s.

5d., thus showing an increase of £1,039 over last quarter."

In addition to the grocery trade, the Committee of Management opened

out new departments at once. They opened the drapers’ shop, and

engaged the services of a shoemaker and clogger, and in the

following quarter the sales were again very encouraging, and an

assistant shopman in the grocery department was engaged. Success

begets a feeling of confidence, and this feeling, once engendered in

the Bury Co-operative Society, grew rapidly amongst the members. In

a very short time all doubts as to the amount of business they were

likely to do vanished, and with them vanished all fears as to the

soundness of the Co-operative principle, a principle of which it has

been well said:—“It supplements political economy by organizing the

distribution of wealth. It touches no man’s fortune, it seeks

no plunder, it causes no disturbance in society, it gives no trouble

to Statesmen, it enters into no secret associations; it contemplates

no violence, it subverts no order, it envies no dignity; it asks no

favour, it keeps no terms with the idle, and it will break no faith

with the industrious; it means self-help, self-dependence, and such

share of the common competence as labour shall earn or thought can

win, and this it intends to have.”

“Mighty things from small beginnings grow.”

――――♦――――

Origin of the Branches.

CHAPTER IV.

FROM the point to which the last chapter brings us the balance

sheets show remarkable development. Before the members got fairly

settled in their own premises, a request was made to establish a

branch shop in the neighbourhood of Rochdale Road, and on July 24th

1860, the Committee decided to take the shop No. 143, in Walker

Terrace, at a rent of £18. Mr. George Clegg was appointed shopman. From the door of this shop at that date could be seen almost the

very spot where Mr. Sully’s garden stood. On the sign was painted

the words: “Co-operative Store, No. 1 Branch.” After taking this

shop, arrangements were made for the building of the Heywood Street

shops, and the business was transferred thereto on completion of the

buildings. On January 10th, 1860, Mr. Mark Rigby and Mr Thomas Baron

Smith were appointed to look out for a site suitable for a

slaughterhouse, and on January 27th it was decided to take one

thousand yards of land in Back Garden Street, for that purpose, at 1½d.

per yard. On October 19th, 1860, No. 40, Moorgate, was taken from

Messrs. Walker & Lomax, at a rental of £22 per year. This shop was

opened and used as a grocery store till the Peter Street range of

shops was built by the Society, the removal taking place in July,

1869.

In August, 1860, a letter was received from a body of working people

in Radcliffe, asking that the Co-operators in Bury would establish a

branch Store in Radcliffe in connection with the Bury Society. The

matter was referred to the Monthly Meeting following, but the

members decided that they could not accede to the request. But the

extension of Co-operation in their vicinity could not be without

interest to them, and they wrote a cordial letter to Radcliffe

expressing willingness to give all information and assistance to

help the Radcliffe people to start a “Store” of their own. As a

result of the receipt of the letter a deputation came over from

Radcliffe to Bury to ask if the Society would allow some of their

members to attend and speak at a meeting to be held in that

district. This was agreed to, and Messrs. Mark Rigby, Thomas

Brierley, Thomas Slater, and Thomas Baron Smith attended, and with

their aid the now

flourishing Radcliffe Society was formed.

A request having been made for a Branch Shop to be opened in Elton,

two members of the Committee were deputed to look out for a suitable

place, and on November 16th, 1860, it was resolved: “That we take

the shop at Crostons, lately occupied by William Pyott, from Mrs.

Whitehead, for the term of year to year, at £14 per year.” Business

was conducted in this shop until the building of the Elton Branch,

which was opened in 1867. On April 6th, 1862, the Quarterly Meeting

passed the resolution: “That a Branch Shop be opened at Blackford

Bridge as soon as convenient.” Arrangements were then made with a

Mr. Rigby to take land adjoining his house at 2½d. per yard. Tenders for the work were obtained, and that of Mr. John Smith was

accepted. The shop was completed and opened in the month of October

following, Mr. John Tootill being engaged as shopman at 20/- per

week.

In November, 1859, it was decided to start a Tailoring department,

and a temporary room was provided over the draper’s shop in Market

Street, the first full quarter’s transactions showing a turnover of

£190. Every effort was made to increase the trade, but the place did

not suit the members, and for a long time no increase in the

receipts could be secured. This determined the Committee to look out

for a more eligible place, one more in touch with the feelings of

the members, and in a short time a shop in Princess Street, owned by

a Mrs. Woods, was taken on rent, and the words “Co-operative Store,

Limited,” were placed on the sign over the shop. Here the tailoring

branch of the Society was conducted until No. 21, Market Street,

then used by Mr. John Greenwood as a shop and beerhouse, known by

the name of the “Rising Sun,” was purchased by Messrs. Abel Standring and John Ashworth on behalf of the Society. The purchase

was made at a sale by auction at the Derby Hotel, in November, 1867.

The tailoring business was conducted in the Market Street premises

till its transfer to No. 18, Silver Street, which took place in

March, 1895, where it remained until the existing premises at the

junction of Broad Street and Silver Street were purchased and

adapted.

The next demand made by the members for a branch Store was made by

those living in the Limefield and Baldingstone districts, and

although the Committee were being kept very busy with building

operations of one sort or another, they had to consent in February,

1865, to a store being established at Limefield. This branch was

opened in a house in Pigslee Hollow, and by the following May was in

full swing, the June quarter’s receipts being £358. On September

4th, 1865, the Committee purchased some property at Limefield from

Mr. Richard Rothwell (a part of which had some years previously been

a beerhouse known by the name of the “Bird-in-Hand”, with the

intention of transferring the grocery business there from the

“Hollow.” This idea was carried out. In May, 1868, a clogger’s shop

was opened at Limefield, but it failed to realize expectations, and

in June of the following year the shop was closed. In the balance

sheet for the September quarter of 1869, the Committee say: “We are

sorry to have to say that during the past quarter we have had to

close the clog shop at Limefield, in consequence of not being

sufficiently supported by the members in that locality to make it

pay.” In October, 1868, a branch Butchering department was opened at Limefield, and remained doing business till the quarter ending

December, 1876, when the business had decreased so much that the

Committee felt compelled to close this also. However, in January,

1881, another effort was made which was more successful, and a

butchers’ business has been done at Limefield ever since.

Early in the year 1866, a body of members hailing from Walshaw,

asked for the consideration of their case, and in February the

Committee decided to establish a branch Grocery Store in that

district. This shop, taken for 21 years from Mr. George Leigh, was

opened in April, 1866; and in October, 1877, a Butchers’ shop was

opened, business being transacted in these rented premises until

January, 1892, when the present range of shops were built, Mr.

Thomas Wilde being the Architect. The Hornby Street branch was the

next to be undertaken. A shop, No. 61, Hornby Street, was purchased

from Mr. Lightbown for £450, and converted into a Grocery branch,

and opened in July, 1866. Here the Store remained until a new shop

was built in the same street. These buildings, after being altered

and enlarged, were found too small for the

constantly increasing business, and in April, 1899, they were pulled

down and the present premises erected.

The branch shop at Heap Bridge was not started by the Bury Society.

It was purchased from the Heap Bridge Co-operative Society, a

Society which had done well in its early years, but which, probably

on account of a decline at the time in the population of that

district, had ceased to be prosperous. The remaining members asked

the Bury Society to purchase it towards the end of the year 1874. The request was complied with, and the shop was taken over in

January, 1875.

In February, 1868, Mr. Thomas Shaw, Clogger, of what was then 53,

Stanley Street, offered his shop, stock, and utensils to the

Society. The offer was accepted, and a Cloggers‘ shop opened, where

business was done till the building of the Peter Street Shops, when

this place was closed and the business transferred to the new

premises.

The decision to open branch shops in Paradise Street and King Street

was arrived at for a different reason altogether from those which

gave rise to the formation of any other branch. In April, 1891,

Messrs. Owen Thomas and Edwin Sharples were appointed delegates to

attend the Co-operative Congress, which was held that year in

Lincoln. At that Congress a Paper was read by Mr. Sydney Webb on the

subject of Co-operators trying the experiment of starting branch

shops in large towns in very poor neighbourhoods. The paper was a

most excellent one, and the delegates came away from Lincoln

convinced that the arguments used were sound, and that the

suggestion was thoroughly practicable. They did not stop here, but

in their report to the June meeting they recommended the members to

give the question their favourable consideration. The advice was

accepted, and the Committee set to work at once. They decided to

purchase No. 50, Paradise Street, from Mr. John Schofield (the

gentleman who sold the Pioneers their first load of flour), for

£182; and the shop in King Street was bought from the Exors. of M.

A. Nabb for the sum of £175. Extensive alterations had to be made in

both places, but the Paradise Street shop was opened September,

1891, and King Street in September of the year following.

Business at the present premises in the other districts began in the

following years; — Bell Lane, 1869; Warth Fold, 1875; Bolton

Road,1877; East Street, 1878; Hudcar, 1881; Fishpool, 1882; Wash

Lane, 1891; Porter Street, 1891; New George Street, 1892;

Fairfield,1890; Ainsworth Road, 1903; and Irwell Street, April,

1905.

To return to the Market Street Shops, always regarded the central

premises of the Society, we have traced the establishment of

Grocery, Butchering, Drapery, and Tailoring Stores. In June, 1873,

two shops, Nos. 25 and 27, Market Street, were purchased from Mr.

Samuel Jackson for the sum of £1,750. The former was opened as a

butchers’ shop, and the latter as a boot and shoe store. On July

21st, 1884, it was decided to purchase No. 23, Market Street, from

Mr. Wm. W. Park for the sum of £975. This was opened for the sale of

hats and caps. The last purchase in Market Street was the property

No. 7, which was bought from Mr. John Horrocks for £700. Co-operators in many parts of Lancashire had proved that it was

desirable to start the business of caterers, and many buildings had

been adapted for that object. The idea had taken root in Bury, and

the present Manager (Mr. Wm. Wild) had long desired to have an

opportunity of proving the utility of this branch of business. The

purchase of the property gave him the opportunity he desired, and

the Board of Management, having obtained the sanction of the

members, set to work at once to carry out the scheme. The property

purchased was pulled down, and the present commodious and handsome

building erected in its place, Mr. David Hardman being the

architect, and Messrs. Thompson & Brierley the builders. The place

was opened by Mr. Wm. Wild on April 11th, 1901, and the following

statement shows the progress made up to the present time:—

|

|

1901

|

1902

|

1903

|

1904

|

|

Average Quarterly takings |

£726 |

£882 |

£1,199 |

£1536 |

|

» Dividend made |

2/2¾ |

2/1¾ |

2/7¾ |

2/9¾ |

The building that taxed the patience of the members the most was the

erection of the Knowsley Street property, comprising the Cellaring,

Warehouse, Offices, Stables, and Hall. It was decided that the work

should be proceeded with on July 11th, 1866, when Mr. Mark Rigby was

President. No time was lost, for on the 16th inst. Mr. Edmund Simpkin was requested to make the plans and specifications. The work

was taken in hand at once, and on September 15th, the plans were

presented to the Committee, passed, and forwarded to the Earl of

Derby’s Agent, the late Mr. Statter, for approval.

Up to this time the meetings of the members had been held in an

upper room in Market Street, and goods had also been warehoused in

Market Street, but for some time prior to 1866 these arrangements

had been found to be totally inadequate to cope with a business that

was always increasing. The capital available for building purposes

was about £14,000. Mr. David Barnes was appointed inspector of

works. The following contracts were entered into:— Edward Hill &

Brothers, stonework, £880; Thomas Clough, brickwork, £1,124; John

Smith, joiners’ work, £1,329; Thomas Balmforth, plumber, £199;

Thomas Fairclough, plastering and painting, £262; John Kay, slating,

£106 10s. Just before the walls of the building were ready for the

roof to be placed upon it, an agitation was started amongst the

members, some of whom desired to have a flat roof, with an

observatory in the centre. The question was brought forward and

discussed at the quarterly meeting held on October 5th, 1867, but

the suggestion was negatived. Undeterred by this resolution, Mr.

Thomas Slater sent the following letter to the Committee under date

October 31st, 1867:—“Gentlemen,—Would you have the kindness to bring

before the monthly meeting of the Society, to be held on Saturday,

November 2nd, 1867, the following proposition for consideration and

discussion: ‘The advisability or otherwise of erecting an

observatory on the Society’s new building, now in progress in Knowsley Street.’”

Mr. Slater brought the matter forward, and after a long discussion

it was decided to adjourn the question to a special meeting to be

held on November 12th, the Committee to get an estimate of the cost

in the meantime. Mr. Edmund Simpkin, the architect, was instructed

to prepare plans and estimates for the cost of two schemes — one to

have the observatory on a corner of the new building, and the other

to have it in the centre. On resuming the debate at the adjourned

meeting, it was very soon evident that the opinion of the members

was evenly divided, and after the meeting had thoroughly thrashed

the matter out, the voting showed 185 votes against the proposal,

and 116 for the observatory. The “No’s“” had it, and consequently no

observatory was built. After this adverse decision the building

proceeded until its completion. Since then several important

alterations have been made respecting the position of the platform

and gallery. The Corporation officials inspect the building once a

year, in order to see that proper arrangements are provided for the

security of life in case of fire, and several improvements have been

made from time to time to comply with their requirements. The

principal alteration has been the construction of two additional

staircases at the back of the Hall, leading down to the back street.

Slight reference has already been made to the removal of the Drapery

department to the buildings at the corner of Broad Street and Silver

Street, but the purchase and adaptation of this large pile of

buildings calls for rather more than passing reference. It had been

evident for some time that the Market Street Drapery premises were

inadequate, but it was not easy to find suitable shops. At length

the Committee decided to purchase the property situate at the above

spot, and known as Stanley Buildings, from the Queen’s Building

Society, Manchester, with the intention of transferring both their

drapery and tailoring business thereto. The cost of the purchase was

£4,400. After the completion of the purchase, the Committee found

that very extensive alterations would be required to make the

building suitable for the purposes for which it was needed. The

contract for the alterations was given to Alderman C. Brierley, and

the whole of the work was finished, at considerable cost, by April,

1901. The formal opening of the new premises took place on the 26th

of that month, the members of the General Board, together with

Alderman Brierley, his clerk, Mr. Barnes, and some of the officials

of the Society being present. The President (Mr. Kay Kay) declared

the building open for business, and expressed the hope that, as the

other ventures the Society had undertaken had been successful, a

like result would be achieved in relation to the present move. He

referred to the many difficulties that had been met and overcome

during the alterations, and said he believed the building had been

strengthened from basement to top storey with columns and girders,

and was substantial and strong, and in every way worthy of the Bury

Co-operative Society.

From a very early period in the Society’s history the members have

been strong on the point that good, wholesome bread should be made,

and baking arrangements have been carried on for a long time.

Extension after extension has had to be made to meet the ever

growing trade of this popular department. Machinery of the most

up-to-date character has been brought into use, and ovens of large

dimensions have been erected. Heavy demands have been made at times

upon the staff and machinery by the placing of large orders for

parties of all descriptions, and the Society have earned a wide

reputation as caterers. Not only is bread baked, but all kinds of

confectionery and sweet cakes are produced, and some idea of the

amount of work done in this department at the present time may be

arrived at by the statement that the average weekly number of sacks

of flour used is 101, and the number of servants employed is 13.

Speaking generally, Co-operators like to be the owners of all the

properties used by them in conducting their trade, and it has been a

rare occurrence for Bury Co-operators to rent a building for

business purposes for any lengthened period. They believe in finding

employment for the capital of their members, and paying rent does

not find such employment; but they are debarred from using their

capital in the purchase of the land on which their buildings stand,

inasmuch as the ground landlords prefer to let land on the leasehold

system for a term of 999 years. In consequence of this preference

all the properties erected by this Society, with one exception, have

been erected on leasehold land, Lord Derby being the owner of almost

the whole of the land. The one exception referred to is the site at Walshaw, where the ground was bought outright for a sum of £181. When the old property, No. 7, Market Street, was purchased, the land

was only for a short lease, and previous to building the Committee

deemed it advisable to re-lease the land, and this Lord Derby

consented to do, at the same time raising the rent from £5 5s. to

£10 10s. per annum. Application was also made to re-lease Nos. 25

and 27, Market Street, the lease originally granted by Lord Derby

being only for 99 years, and the Committee were anxious to have all

Market Street properties on a long lease. This land Lord Derby

consented to re-lease for 999 years on an increased rent from £8

18s. to £17 10s. per year, a proposal to which the Committee

consented. The total amount of ground rent paid to Lord Derby by the

Society during 1901 was £650, and the amount paid to other parties

was £135.

|

"Look back, how much there has been won,

Look round, how much there is to win;

The watches of the night are done,

The watches of the day begin." |

――――♦――――

|

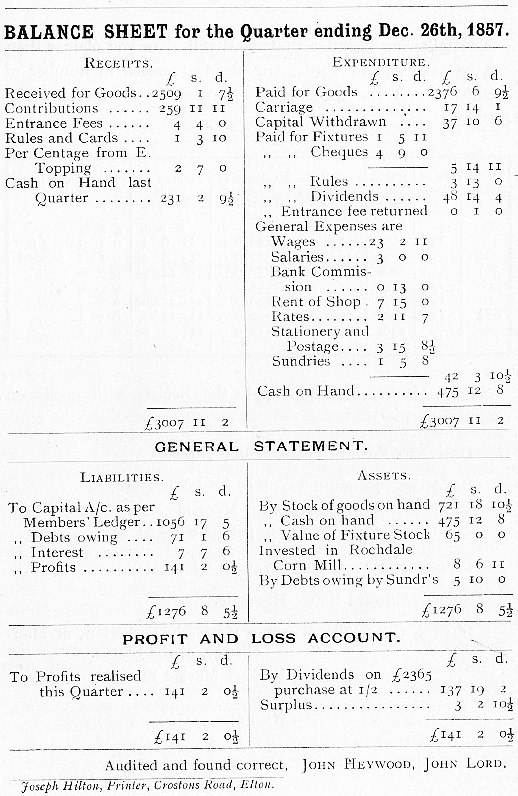

JAMES HOLDEN

(The first permanent Secretary and

Manager of the Society, and compiler of our first

balance sheet, a very valuable document, which will be

found on the next three pages). |

――――――

Bury Co-operative Provision Society.

President:― THOMAS BARON

SMITH

Trustees:― Robert Law, Robert Austin, Thomas Balmforth.

Treasurer:― Richard Sully.

Secretary:― James Holden.

Committee:― Mark Rigby, George Yates, William Tweedale,

Robert Carter, and Joshua Proctor.

Auditors:― John Lord and John Heywood.

――――――

QUARTERLY REPORT

ENDING DECEMBER 26TH,

1857.

To the Members of the Bury Co-operative Provision Society.

Fellow Members,

In laying this Quarter’s Report before you, we would

earnestly desire you to examine the various statements contained, to

weigh them honestly, to judge them fairly, then calmly, soberly, and

impartially to say, has any good resulted, or will any be derived

from such Associations as this, of which you have now ample

evidence.

It has been thought desirable to place before you the results which

have been accomplished by your aid (and that of others, who through

circumstances over which they had no control, and who have been

compelled to leave the town), in order that you might see our

progress has been one of gradual and satisfactory onward progress;

that we have in the short space of about one year and eleven months

attained a position never surpassed, if ever equalled, in the same

time by any cooperative body in

existence.

Your attention is also solicited to the names appended to this

report, who are now doing business for the Society on commission,

your cordial and unanimous support and patronage to these

individuals is respectfully solicited by the committee, in order

that they may still further promote the good and welfare of the

Society and its members.

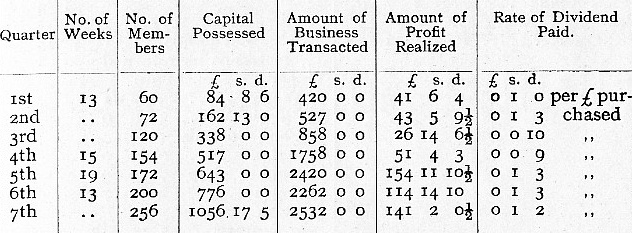

The following Tabular Statement will shew you plainer than can be

expressed in words, our steady increase in number of Members, and

the consequent extension of business of the Society:

Names of persons who supply the Society with goods on commission:—

DRAPERY—Edward Potts, Bolton Street.

BUTCHERS—Edmund Topping, Rochdale Road.

William Redfern, Moorside.

James Redfern, Princess Street, Mosses.

CLOGGER—John Cooper, Water Street.

SHOES—Edward Bates, Moorside.

HATS & CAPS—The Working

Hatters’ Association, of Manchester, at the Stores.

Richard Parker, Market Street.

We are,

Yours truly,

THE COMMITTEE.

――――♦――――

Wellington Mill & Bury Permanent

Co-operative Building Society

CHAPTER V.

IT is interesting

to note that there has always been a close relationship between the

Bury Co-operative Society and the Bury Co-operative Manufacturing

Company Ltd., or Wellington Mill, as being the first mill built in

this town after the passing of the Joint Stock Act. As early as

April, 1859, just when the Bury Co-operators were meeting under

their own roof in Market Street, Mr. Richard Sully asked leave for

the use of their meeting-room for a few Co-operators who were

anxious to discuss the advisability of building at Mill. The

application was at once granted free of charge, and in that room the

preliminary steps were taken which resulted in the building of the

Wellington Mill. Several meetings were subsequently held, and on

February 18th, 1860, a special meeting was held in the Stores’

Newsroom, presided over by Mr. Sully, at which it was decided; “That

a Company be formed to carry on the business of a Cotton Spinning

and Weaving Concern, and that a Committee of eleven be formed, to

consist of the following persons:—Messrs. Thomas Slater, J. C. Hill,

Richard Sully, John Hall, Abraham Whittaker, Thomas Jackson, Thomas

Clegg, John Valtous, William Tweedale, John Wain, amd Joseph

Holmes.” It was resolved, further, that the Company be separate and

distinct from the Stores. Many more of the pioneers of the

Co-operative movement rendered valuable aid in carrying out the

object. The corner stone of the Mill was laid on July 16th, 1860,

and Mr. Richard Sully was afterwards appointed first Chairman of the

Company. He held that office till August, 1862, but remained a

member of the Board for many years after.

|

|

|

Edwin Barnes

(one of the founder members of our

Society). |

Having found the men, it was natural that the Society should be

looked to for a share of the capital. The expectation was not

disappointed, and on May 7th, 1864, the members agreed to lend the

Company £2,000 on mortgage security. At various times subsequent to

this date the amount was increased, until in January, 1867, the sum

advanced on mortgage was increased by £6,000, making a total of

£14,000. In January, 1877, a further sum of £3,000 was lent to the

mill on loan, making a total of £17,000. Since the last-named date,

the Company has fortunately been both able and willing to reduce its

indebtedness, and has at various times repaid to the Society sums of

not less than £1,000, until in the balance sheet for December, 1904,

the amount standing on mortgage is £5,000. The half-yearly meetings

of the Company have always been held on the premises of the

Co-operative Society. The mill was completed in the troublous days

of the American War, and it had to wait until the termination of

hostilities and the reduction in the price of cotton before it could

begin operations. A start was made in February, 1865.

Bury Permanent Co-operative Building Society.

Besides the Wellington Mill, the Bury District Co-operative Society

has given birth to another institution whose career of usefulness

has left its mark upon the life of the town. We allude to the Bury

Permanent Co-operative Building Society. The members decided in the

latter part of 1868 to start an organisation into which they could

pay money as subscriptions, such money to lie there until such times

as they decided either to buy or to build a house. As in the case of

the Wellington Mill Company, it was resolved that the Building

Society should be separate and distinct from the parent Society, and

bearing its own financial responsibility. Operations were commenced

in April, 1869, when Mr. William Addy was appointed chairman, Mr.

Charles Atkinson treasurer, and Mr. John Hilton secretary. The other

members of the Committee of Management were Messrs. Lawrence Walker,

John Lord, jun., Robert Meadowcroft, Jeremiah Fielding, and David

Perritt. Messrs. Henry Driver, John Olive, and John Burgoine became

the first trustees.

Subscriptions soon began to flow in freely. Advances on mortgage to

members were made on a liberal scale, and in a short space of time

the Building Society became a popular institution. In the latter

part of the year 1877, owing to the number of applications from its

members to use the funds of the Society, it became necessary to seek

outside assistance, and the Co-operative Society lent the Building

Society £1,000 to meet such demands. This sum was repaid within

twelve months. From its birth the Bury Permanent Co-operative

Building Society has been an economical, well-managed, and

beneficial concern, and has been no mean factor in helping forward

the principles of thrift and commercial honesty which Co-operation

has ever sought to place in the front rank, a harvest of good and

intelligent citizens being the result. The meetings of the Society

have always been held on the premises of the Co-operative Society,

and although the two Societies are not to be regarded as identical —

inasmuch as each bears its own burdens and has its own defined

objects — it may be said with perfect truth that they have concluded

an offensive and defensive alliance against the old evils that

Co-operation came into existence to remove.

――――♦――――

A Great Trial.

CHAPTER VI.

THE breaking out

of the American War and the consequent scarcity and high price of

cotton, prices going up to 2/7½

per lb. for Mid. American in July, 1864, was the cause of one of the

most severe trials that Lancashire was ever called upon to bear. Bury and district suffered in common with the rest of the county. The impossibility of getting cotton from America caused a large

number of mills to stop altogether, and many more to go on for a few

days only per week, whilst many trades closely allied with cotton

shared in the trouble. Hundreds of families in Bury, formerly in

fairly comfortable circumstances, began to feel the keen pinch of

poverty, and to realise the pangs of hunger. Many who had been

striving to lay by for a rainy day were compelled to part with their

hard-earned savings, in their efforts to stem the tide of trouble. In the great majority of cases the effort was futile, and the