|

A VOICE FROM DREAMLAND.

A

VOICE from dreamland said to me—

"Poet, what music is in thee ?

Ring it out until it find

A nook for rest within thy kind."

I stood and heard the voice speak out,

Then answered, bowing low in doubt,

"Of what use is a simple song,

That vainly wrestles to be strong?"

For, ever as I shape my lips,

A darkness comes and, rising, dips

In misty folds the vain, weak words

That creep by fits along the chords."

The voice then questioned,

"Art thou sure

If all thy purposes be pure?

If whim or low conceit is in

Thy singing: singing thus is sin."

I answered to that ready voice,

"I sing not as if making choice;

The impulse bearing me along

Has driven me against my song,

"And all my soul, like flax at fire,

Leaps up to grasp but one desire—

That I may touch the lower strings,

And fit them unto noble things."

I waited for the voice again,

But silence fell between us twain;

At last, like a low breath in spring,

The voice made answer, saying, "Sing!" |

|

__________________________

CUDDLE DOON.

|

|

THE bairnies cuddle

doon at nicht,

Wi' muckle faucht an' din—

"O, try and sleep, ye waukrife rogues,

Your faither's comin' in"—

They never heed a word I speak;

I try to gi'e a froon,

But aye I hap them up, an' cry,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

Wee Jamie wi' the curly heid—

He aye sleeps next the wa'—

Bangs up an' cries, "I want a piece—

The rascal starts them a'.

I rin an' fetch them pieces, drinks,

They stop awee the soun',

Then draw the blankets up an' cry,

"Noo, weanies, cuddle doon."

But ere five minutes gang, wee Rab

Cries oot, frae 'neath the claes,

"Mither, mak' Tam gi'e owre at ance,

He's kittlin' wi' his taes."

The mischief's in that Tam for tricks,

He'd bother half the toon;

But aye I hap them up an' cry,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

At length they hear their faither's fit,

An', as he steeks the door,

They turn their faces to the wa',

While Tam pretends to snore.

"Ha'e a' the weans been gude?" he asks,

As he pits aff his shoon.

"The bairnies, John, are in their beds,

An' lang since cuddled doon."

An' just afore we bed oorsel's,

We look at oor wee lambs;

Tam has his airm roun' wee Rab's neck,

An' Rab his airm roun' Tam's.

I lift wee Jamie up the bed,

An', as I straik each croon,

I whisper, till my heart fills up,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

The bairnies cuddle doon at nicht

Wi' mirth that's dear to me;

But sune the big warl's cark an' care

Will quaten doon their glee.

Yet, come what will to ilka ane,

May He who rules aboon

Aye whisper, though their pows be bald,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon." |

|

__________________________

WAUKEN UP.

A Sequel to "Cuddle Doon."

|

|

WULL I ha'e to speak

again

To thae weans o' mine?

Eicht o'clock, an' weel I ken

The schule gangs in at nine.

Little hauds me but to gang

An' fetch the muckle whup—

O, ye sleepy-heidit rogues,

Wull ye wauken up?

Never mither had sic faught—

No' a moment's ease;

Cleed Tam as ye like, at nicht

His breeks are through the knees.

Thread is no' for him ava'—

It never hauds the grup;

Maun I speak again ye rogues—

Wull ye wauken up?

Tam, the very last to bed,

He winna rise ava'

Last to get his books an' sklate—

Last to won awa'.

Sic a limb for tricks an' fun—

Heeds na' what I say,

Rab and Jamie—but thae plagues—

Wull they sleep a' day?

Here they come, the three at ance,

Lookin' gleg an' fell,

Hoo they ken their bits o' claes

Beats me fair to tell.

Wash your wee bit faces clean,

An' here's your bite an' sup—

Never was mair wiselike bairns

Noo they've waukened up.

There, the three are aff at last,

I watch them frae the door,

That Tam, he's at his tricks again,

I coont them by the score.

He's put his fit afore wee Rab,

An' coupit Jamie doon,

Could I but lay my han's on him

I'd mak' him claw his croon.

Noo to get my wark on han'

I'll ha'e a busy day,

But losh! the hoose is unco quate

Since they are a' away.

A dizzen times I'll look the clock

When it comes roun' to three,

For, cuddlin' doon, or waukenin' up,

They're dear, dear bairns to me. |

|

__________________________

THE LAST TO CUDDLE DOON.

|

|

I SIT afore a half-oot

fire,

An' I am a' my lane,

Nae frien' or fremit daun'ers in,

For a' my fowk are gane.

An' John, that was my ain gudeman,

He sleeps the mools amang—

An auld frail body like mysel'—

It's time that I should gang.

The win' moans roun' the auld hoose en',

An' shakes the ae fir tree,

An' as it sughs it waukens up

Auld things fu' dear to me.

If I could only greet, my heart

It wadna be sae sair;

But tears are gane, an' bairns are gane,

An' baith come back nae mair.

Ay, Tam, puir Tam, sae fu' o' fun,

He faun' this warld a fecht,

An' sair, sair he was hauden doon,

Wi' mony a weary wecht.

He bore it a' until the en',

But, when we laid him doon,

The grey hairs there afore their time

Were thick amang the broon.

An' Jamie wi' the curly heid,

Sae buirdly, big an' braw,

Was cut doon in the pride o' youth

The first amang them a'.

If I had tears for thae auld een,

Then could I greet fu' weel,

To think o' Jamie lyin' deid

Aneath the engine wheel.

Wee Rab—what can I say o' him?

He's waur than deid to me,

Nae word frae him thae weary years

Has come across the sea.

Could I but ken that he was weel,

As here I sit this nicht,

This warld wi' a' its faucht an' care

Wad look a wee thing richt.

I sit afore a half-oot fire

An' I am a' my lane,

Nae frien' ha'e I to daun'er in,

For a' my fowk are gane.

I wuss that He wha rules us a',

Frae where He dwalls aboon,

Wad touch my auld grey heid, and say—

"It's time to cuddle doon." |

|

__________________________

RAB COMES HAME.

|

|

WAS that a knock?

Wha can it be?

I hirple to the door;

A buirdly chiel' is stan'in' there,

I never saw afore.

He tak's a lang, lang look at me,

An' in his kindly een

A something lies I canna name,

That somewhere I ha'e seen.

I bid him ben; he tak's a chair,

My heart loups up wi' fricht,

For he sits doon as John wad do

When he cam' hame at nicht.

He spreads baith han's upon his knees,

But no' ae word he speaks;

Yet I can see the big, roun' tears

Come happin' doon his cheeks.

Then a' at ance his big, strong airms

Are streekit out to me

"Mither, I'm Rab, come hame at last,

An' can ye welcome me?"

"O, Rab!"—my airms are roun' his neck—

"The Lord is kind indeed;"

Then hunker doon, an' on his knees

I lay my auld grey heid.

"Hoo could ye bide sae lang frae me,

Thae weary, weary years,

An' no' ae word—but I maun greet,

My heart is fu' o' tears;

It does an' auld, frail body guid,

An' oh! it's unco sweet.

To see ye there, though through my tears,

Sae I maun ha'e my greet.

"Your faither's lang since in his grave

Within the auld kirkyaird,

Jamie an' Tam they lie by him—

They werena to be spared;

An' I was left to sit my lane

To think on what had been,

An' wussin' only for the time

To come an' close my een.

"But noo ye're back, I ken fu' weel

That no' a fremit han'

Will lay me, when my time comes roun',

Beside my ain gudeman."

Noo, wad it be a sin to ask

O' Him that rules aboon,

To gi'e me yet a year or twa

Afore I cuddle doon? |

|

__________________________

THE TWO SOWERS.

|

|

DEATH came to the

earth, by his side was Spring,

They came from God's own bowers,

And the earth was full of their wandering,

For they both were sowing flowers.

"I sow," said Spring, "by the stream and the wood,

And the village children know

The gay glad time of my own sweet prime,

And where my blossoms grow.

"There is not a spot in the quiet wood

But hath heard the sound of my feet,

And the violets come from their solitude

When my tears have made them sweet."

"I sow," said Death, "where the hamlet stands,

I sow in the churchyard drear;

I drop in the grave with gentle hands,

My flowers from year to year.

"The young and the old go into their rest,

To the sleep that awaits them below;

But I clasp the children unto my breast,

And kiss them before I go."

"I sow," said Spring, "but my flowers decay

When the year turns weak and old,

When the breath of the bleak wind wears them away,

And they wither and droop in the mould.

"But they come again when the young earth feels

The new blood leap in her veins,

When the fountain of wonderful life unseals,

And the earth is alive with the rains."

"I sow," said Death; "but my flowers unseen

Pass away from the land of men,

Nor sighs nor tears through the long sad years

Ever bring back their bloom again.

"But I know they are wondrous bright and fair

In the fields of their high abode;

Your flowers are the flowers that a child may wear,

But mine are the blossoms of God."

Death came to the earth, by his side was Spring;

The two came from God's own bowers;

One sowed in night and the other in light,

Yet they both were sowing flowers. |

|

__________________________

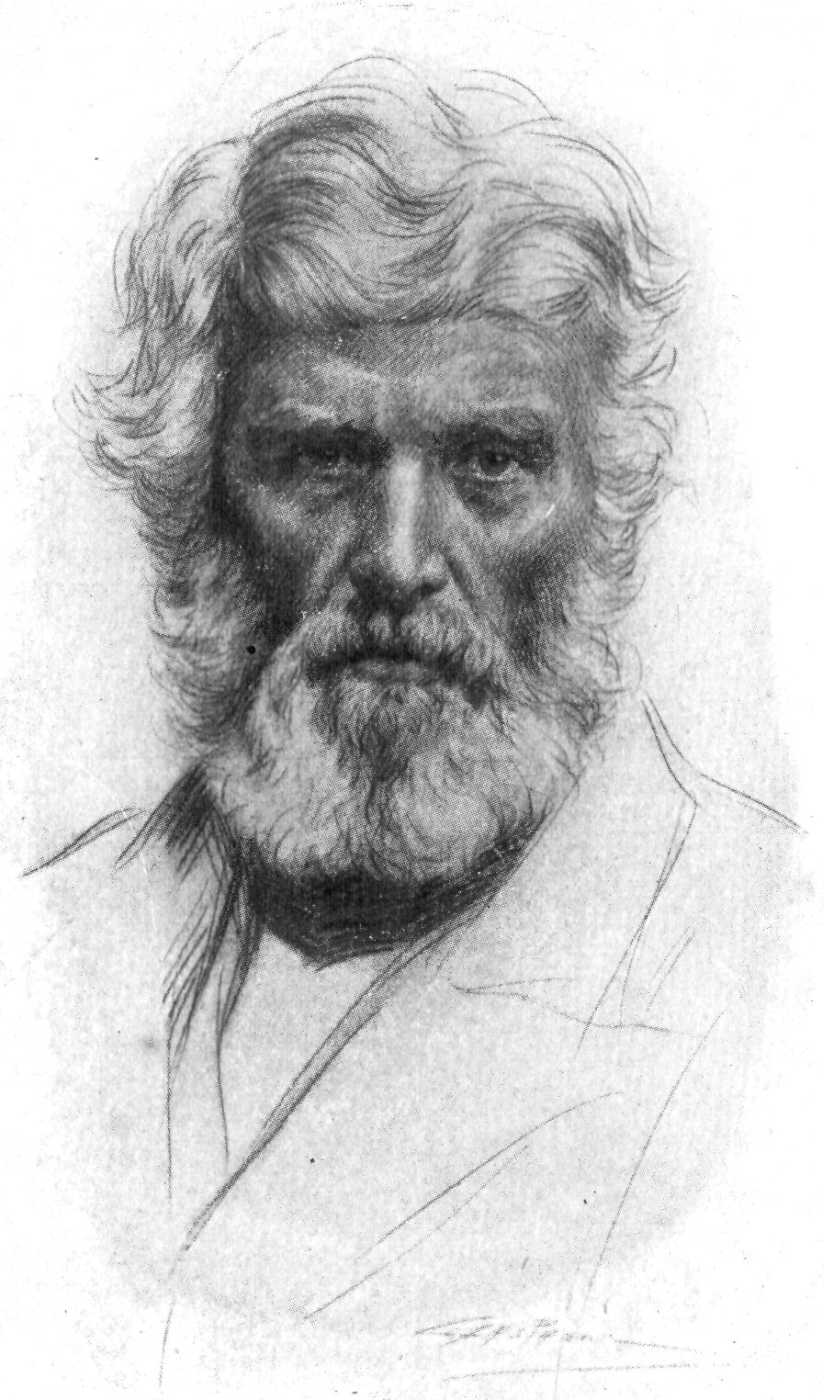

CARLYLE.

|

|

|

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881)

Scottish essayist, satirist, and historian. |

|

|

ENGLAND, amid thy great

in this great time

One man, white-haired, with misty, flashing eyes

Looms from the rest, in his life's toil sublime,

And all that hath the power to make us wise.

We hail him teacher, not as now they teach,

With soulless flow of ever-ready words;

He shapes his own life to his uttered speech,

As deft musicians to the air the chords.

So in this age when the quick growth of creeds

Grows up, as if to choke God's primal plan,

Ye who still waver in your higher needs,

Come and look nearer at this grey old man.

The Hebrew spirit, with its fervent fire,

Its vatic utterances of rapt word force

Is in him, bursting in explosive ire,

Like lightning when it takes its blinding course.

And Cant, girt in her armour o'er and o'er,

Lifting her putrid wings as if to fly,

Sinks in the slime of her own tracks, before

The word bolts of this thunderer to die.

He will not rest himself on other ground

Than that which God's own workers have made

smooth;

All other is to him the heave and bound,

And the volcanic motion of untruth.

This struggle for firm footing for his feet

Hath made his inner vision far and clear,

Piercing the under current, and the heat

That nourishes the action we have here.

Stern Cromwells, Luthers, Knoxes unto him

Rise from the world's wild clamour, and serene

Stand in heroic light that cannot dim

The virtue and the duty that have been.

All work is noble, but a nobler kind

Is that whose task is ever piercing through

The mummy folds of ignorance to find

True worth in man and hold it up to view.

High privilege this; but he upon whose head

It lights must ever walk and speak in fear,

Knowing the ages listen what is said,

And God above him bending down his ear.

Thus has he ever written, knowing well

What kind of heed to give the countless strings

Of those who, like the Corybantes, yell

When some slow good grows out of human things.

Not looking to the right nor to the left,

But conscious of the guide he had within,

He, armed with his strong battle words, has cleft

Paths for the feebler soul to take and win.

"Thou shalt believe in God," he cries, "and own

The sacredness of this poor life, though dim;

It is a part of His, in darkness thrown

Upon the earth to wander back to Him.

"Let no cant be within thy soul, but stand

Upon thy manhood, thy most sure defence,

Working at all true work with willing hand,

And growing up to God-like reverence."

For reverence with this man is the source

Of all those virtues which, like golden threads,

Draw man still upward with an unseen force

To where his spirit with the higher weds.

Be thou real also, be no sham or quack,

Half seen as manhood sickens and expires,

Two beings in thee resting back to back,

And turning vane-like as the world desires.

It may be that the force in him for this

Has borne him past his distance, as a steed,

The nostrils filling out with snorting hiss,

Tears up the ground before he checks his speed.

For all the early earnestness to wage

Battle with evil, is in him the soul

Of all his thought and life, that now in age

Moves grandly ripening to the wrought-for goal.

Then, brother, take him for thy teacher, let

The spirit of his words flash full on thine,

And thou shalt feel a dignity in sweat,

And all thy life and labour half divine.

I too can feel a pride to think I stand

A worker on a dusty railway here,

Pointing to this man with a feeble hand,

As one by whom the weaker ought to steer.

But he has strengthened me, as teachers ought

Who wrestle onward to the purer change,

Has fused more earnestness into my thought,

And made this manhood take a higher range.

Enough, the shadows lengthen far ahead

When the sun turns his feet to meet the west;

So this man's power shall broaden out and spread

When he, too, takes his well-earned sleep and rest.

But the full day beats on us, and the night

Is yet afar; so with strong heart and limb

Let us go onward, upward, and upright,

Until we take a twilight rest like him. |

|

__________________________

A VILLAGE SCENE—EVENING.

|

|

THE merry children are

playing

In the little village street;

The old men sit by the doorway:

Their evening rest is sweet.

And careful mothers are busy,

They hurry out and in;

Or pause by the door for a moment

To smile at their children's din.

And farther away in the distance,

From the playground comes a shout,

As quick-eyed youths at their pastimes

Run, strong of limb, about.

The old men sit by the doorway;

The children play in the street;

The dead are up in the churchyard,

Their rest is long and sweet. |

|

__________________________

OH, FOR THOSE DAYS.

|

|

OH, for those days that

had no doubt,

When I, a simple village laddie,

Sang with much glee the rhyme about

The devil's grave in old "Kirkcaldy!"

"Some say the de'il's dead," thus it ran;

I thought it very nice and witty,

So sang, unwitting, when a man,

He'd rise and pay me for my ditty.

Of course, I knew not then how much

He works with men and all their actions—

How all their plans are at a touch

Split into half-a-dozen factions.

Nor had I read those books that teach

The line between the good and evil;

Nor knew I what poor Faust could preach

When in the clutches of the devil.

I sang with little thought of this,

Or any such dim speculations;

And proved that ignorance was bliss

By very candid demonstrations.

He never came to me, nor did

I bother him with my intrusions,

But followed where I wished, and hid

Myself from all his deep illusions.

At last when halfway through my 'teens,

And life became a shade impassioned,

He rose up, full of all his spleen,

Just as my various bents were fashioned.

Then found I, to my grief, that he

Had risen from his grave, to wander,

A very poodle, after me,

To act as sworn and faithful pander.

He seemed at first so very sweet,

So full of nice polite attention,

I could have kissed his very feet,

Like others whom I need not mention.

He led me into many things,

Each very simple, fresh and pleasing,

Yet leaving always after stings,

That at the first were very teasing.

But in a little while they ceased,

And left me to my own enjoyment;

Nor did they come to mar my feast,

Like Banquo at the same employment

Of pale Macbeth; but, if their sting

I felt, true to my human nature,

I bounced and blamed some other thing

In philosophic nomenclature.

Ah, well, I'm rough and bearded now,

And given less to quick impulses;

Nor can I run away and bow

To that which one swift moment dulces.

But still I yearn to have that heart

I had when, yet a simple laddie,

I sang that song with little art

About that grave in old Kirkcaldy. |

|

__________________________

THE DYING COVENANTER.

|

|

LET me lie upon the

heather

Where the heath fowl have abode,

In my hand the open Bible,

On my lip the psalm of God.

I have kept the faith and conquered,

Slipped not foot nor quailed an eye;

Gather round, and in the moorland

See a Covenanter die.

In the might of kingly sanction,

As the mountain torrents sweep,

Came the foe, athirst for slaughter,

And their oaths were loud and deep.

But we drew ourselves together,

Broke the still, yet pitying calm

With the music of our fathers,

And the worship of the psalm.

Then we heard our leader's question,

"Is there one within our band

Faint of heart to go to battle

For his God and for his land?

Is there one who, seeing foemen

Coming from the plain below,

Puts his sword back in the scabbard?"

And we sternly answered, "No.

"For we fight against oppression,

For the weak against the strong,

For the right to God's own freedom,

And against the wrong of wrong,

For our homes in glen and valley,

For a thing of grander worth,

The old worship of our fathers

In the kirk and by the hearth."

Then we took a deeper breathing

For the fight that was so near,

Put our Bibles in our bosoms,

With no sign of doubt or fear,

Felt upon our lips a prayer,

Drew forth to a man the sword,

Rushed upon the ranks of Satan,

For our Covenant and the Lord.

Ye have seen, beside the river.

The tall bulrush, thick and strong,

Bend before the summer whirlwind

As it swept in might along.

Lo, the foe at the first onslaught

Backward went in their alarm,

Ours we knew would be the battle,

For the Lord held up His arm.

Ay, we knew that He was with us,

Israel's mighty God of old,

Felt His spirit clasp our spirit,

And His presence made us bold;

And we raised our thrilling slogan

Till it ran from tongue to tongue—

"God and Covenant, God and Covenant!"

And the bleak, bare moorland rung.

Had you seen the wild rough troopers,

Pale with very rage and hate,

As our steel still sent them backwards

To a flight or sterner fate.

"Canting dogs!" they cried, "and martyrs

For their heaven's paltry crown."

"Soldiers now," we hurled for answer,

And we shore the godless down.

Ay, they well may con their lessons

In their revels of to-night,

Tell, with all their newest curses,

That the babes of God can fight.

Did they think us sheep for slaughter,

Weak as weakest children be?

So they want that question answered,

Let them turn to their Dundee.

How the frown upon his forehead

(For I saw him in the fight)

Deepened till it burst in anger,

As the thunder peals by night!

And, when column after column

Shrank and withered at our brunt,

Onward came he like some devil,

With his black steed to the front.

"Are ye cowards?" forth he thundered,

As he rallied back his men.

"Fly from those that ye have hunted

Like the hare by field and glen?

What am I to send for answer

In your own, and in my name?

Give me better, or, by heaven!

Die, and so escape the shame!"

Ye have seen, beside the river,

The tall bulrush, thick and strong,

Springing upward when the whirlwind

Spent its force and passed along;

So came backward horse and trooper

On our firm, yet desperate few,

But our trust was not in princes,

And we knew what God could do.

Wild and high the conflict thickened

As a thunder-spout adds force

To the stream, and in the struggle

Down went rider, down went horse.

Foot by foot we drove them backward,

But they went like sullen seas,

Till I came against a war-horse,

And I knew it was Dundee's.

Swift as lightning's gleam at midnight,

When the stars are hidden dark,

Swift my sword upon the charger,

And I did not miss my mark.

Back he reared upon his rider,

And the two fell on the plain;

Had we not been such a handful

Black Dundee was with the slain.

But his troopers rallied round him,

Fought like devils at their need,

Drove us back and raised their master,

Brought him up another steed,

Made a front to stand our onset;

But they shrank as on they came,

Like the willow in the winter,

Like the heath before the flame.

Then we raised a shout of triumph

As the whelps of Satan fled,

But my death-wound came that moment,

And I fell among the dead.

Steeds and men, like one great whirlwind,

Thundered o'er me, and I knew

That our God had swept the godless

As the sun sweeps off the dew.

Closer, closer come around me,

Lift the grand old psalm again,

For I want to hear its music

Ere I pass away from men.

Shame to Scotland and to Scotsmen,

If they turn away in pride

From the songs that were our bucklers

On the bare, bleak mountain-side.

Let the Bible still lie open,

That my failing sight may see

My own blood upon that promise

Of the crown awaiting me.

I have kept the faith nor faltered,

Slipped not foot nor quailed an eye;

Gather round, and in the moorland

See a Covenanter die. |

|

__________________________

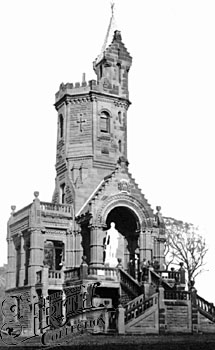

ROBERT BURNS.

On the Inauguration of the Burns' Monument at Kilmarnock,

August, 1879.

|

"See projected through time

For HIM an audience interminable."

WALT WHITMAN. |

|

|

Ho! stand bare-browed with me to-day, no common name we sing,

And let the music in your hearts like thunder-marches ring;

We hymn a name to which the heart of Scotland ever turns,

The master singer of us all, the ploughman—ROBERT BURNS.

How shall we greet such name that stands a beacon in the years?

With smiles of joy and love, or bursts of laughter and sweet tears?

Greet him with all—a fitting meed for him who came along,

And wove around our lowly life the splendours of his song.

What toil was his; but, know ye not, that ever in their pride

The unseen heaven-sent messengers were walking side by side;

He felt their leaping fire, and heard far whispers shake and roll,

While visions, like the march of kings, went surging through his soul.

"Thou shalt not sing," they cried, "of men low set in sordid life,

Nor statesmen strutting their brief hour in rancour and in strife,

Nor the wild battle-field where death stalks red, and where the slain

Lie thicker than in harvest fields the sheaves of shining grain.

"Sing thou the thoughts that come to thee, to lighten all thy brow,

When, with a glory all around, thou standest by the plough,

Sing the sweet loves of youth and maid, the streams that glide along,

And let the music of the lark leap up within thy song.

"Sing thou of Scotland till she feels the rich blood fill her veins,

And rush along like mimic storms at all thy glorious strains;

A thousand years will come and pass, and other poets be,

But still within her heart of hearts shall beat the soul of thee."

He came, and on his lips lay fire that winged his fervid song,

And scathed like lightning all that rose to walk behind a wrong;

He sang, and on the lowly cot beside the happy stream,

A halo fell upon the thatch, with heaven in its gleam.

And love grew sweeter at his touch, for full in him there lay

A mighty wealth of melting tones, and all their soft sweet way;

He shapes their rapture and delight, for unto him was given

The power to wed to burning words the sweetest gift of heaven.

O blessing on this swarthy seer, who gave us such a boon,

And still kept in his royal breast his royal soul in tune;

Men looked with kindlier looks on men, and in far distant lands

His very name made brighter eyes and firmer clasp of hands.

The ploughman strode behind his plough, and felt within his heart

A glory like a crown descend upon his peaceful art;

The hardy cotter, bare of arm, who wrestled with the soil,

Rose up his rugged height, and blessed the kingly guild of toil.

And sun-browned maidens in the field among the swaying corn,

Their pulses beating with the soft delight of love new born,

Felt his warm music thrill their hearts, and glow to finger tips,

As if the spirit of him who sang was throbbing on their lips.

What gift was this of his to hold his country's cherished lyre,

And strike, with glowing eye, the chords of passion's purest fire;

Say, who can guess what light was shed upon his upturned brow,

When in the glory of his youth he walked behind the plough?

What visions girt with glorious things, what whispers of far fame,

That from the Sinai of his dreams like radiant angels came;

What potent spells that held him bound, or swift, and keen and strong,

Lifted to mighty heights of thought this peasant king of song!

Hush, think not of that time when Fame her rainbow colours spread,

And all the rustling laurel-wreath was bound about his head;

When in the city, 'mid the glare of fashion's living light,

He moved—the whim of those that wished to see the novel sight.

Oh, heavens! and was this all they sought? to please a moment's pride,

Nor cared to know for one short hour this grand soul by their side;

But shook him off with dainty touch of well-gloved hand, and now—

Oh, would to God that all his life had been behind the plough?

And dare we hint that after this a bitter canker grew,

That all his aspirations sank, and took a paler hue;

That dark and darker grew the gloom till in the heedless town,

The struggling giant in his youth heart-wearied laid him down ?

What were his thoughts, that sad last hour, of earth—ah, who can tell!

When, by the column of his song our laurelled Cæsar fell ?

We ask but questions of the Sphinx; we only know that death,

Unclasped his singing robes in tears, but left untouched the wreath.

Thou carper; well we know at times he sung in wilder mirth,

Till the rapt angel of his song had one wing on the earth;

But canst thou wild volcanoes tame, to belch their hidden fire,

Without one stain of darker red to shame its glowing pyre ?

Back to thy native herd, and spend thy little shrunken day,

And if thou sting—for sting thou must—let it be common clay;

There live, nor step across this pale, but leave the right to heaven

To judge how far this soul has dimmed the splendours it has given.

For us who look with other eyes he stands in other light,

A great one stumbling on with hands outstretched to all the right;

Who, though his heart had shrunk beneath the doom that withers all,

Still wove a golden thread of song to stretch from cot to hall.

And now as when the mighty gods had fanes in ancient days,

And up the fluted columns swept great storms of throbbing praise,

So we to all, as in our heart this day with tender hand,

Uprear the marble shape of him, the Memnon of our land.

And sweeter sounds are ours than those which from that statue came,

When the red archer in the East smote it with shafts of flame;

We hear those melodies that made a glory crown our youth,

And wove around the staider man their spells of love and truth.

And still we walk within their light—a light that cannot die;

It streams forth from a purer sun and from a wider sky;

It crowns this heaven-born deputy of Song's supremest chords,

And leaps like altar flame along his soul-entrancing words.

Lo! take the prophet's reach of sight, and pass beyond the gloom,

Where thousands of our coming kind in thronging legions loom;

They, too, will come as we this hour with passionate worship wrung,

And place upon those mute, white lips, the grand great songs he sung.

Ho! then, stand bare of brow with me, no common name we sing,

And let the music in your hearts like thunder marches ring;

We hymn a name to which the heart of Scotland ever turns,

The master singer of us all, our ploughman—ROBERT BURNS! |

|

__________________________

WALT WHITMAN.

|

|

STRONG poet of the

sleepless gods that dwell

As far above the stars as we beneath,

Whose melody disdaining the soft sheath

Of dainty modern music, snaps the spell,

And careless of all form or fettering plan

Clothes itself slovenly in rough, free words,

And strikes with no soft touch the inner chords

That vibrate with the strong and healthy man.

What if the ages that are yet to be,

Emerging from the bloodless wars of thought,

Seize hollow custom, and at one keen blow

Smite off its seven heads, and having smote,

Turn round, and with their larger veins aglow

With new found vigour mould themselves to thee? |

|

__________________________

GOETHE.

|

|

UP went the finger, but

that royal eye,

Whose cunning saw through human life, was dim,

And fast becoming traitor unto him

Who used it with such magic. Ever nigh

And nigher, death crept to the feeble heart;

But, as the misty darkness came apace,

There slowly rose upon the sinking face

The soul's desire of Faust—the better part,

Which, working through a long, long life, became

A second being. Wrapt in earthly bands,

That now were giving way for other lands,

Whose light, slow dawning, was not held the same

As his—but as a darkness unto him—

"More light." It came, and all grew still and dim. |

|

__________________________

GETHSEMANE.

|

|

I WILL go into dark

Gethsemane,

In the night when none can see;

I will kneel by the side of Christ my Lord,

And He will kneel down with me.

I will bow my head, for I may not look

On that brow with its bloody dew,

Nor into those eyes of awful pain,

With the dread cross shining through.

Then my soul rose up, as a man will rise

Who hath high, stern words to speak,

And said, "Now what wilt thou do by Him

With that sweat on brow and cheek?

"Canst thou drink from the cup he proffers thee?

Canst thou quaff it at a breath?

For the dregs are sorrow and scorn and shame,

The crown of thorns and death.

"Stand thou from afar, for thou canst not know

That hour in Gethsemane.

Thou canst only know, in thine own dim way,

That He strove that night for thee."

So I stand afar, and I bow my head;

But I dare not look into those eyes,

Whose depths have the depths of the night

around,

With the starlight in the skies.

And my soul, as a friend will talk to a friend,

Still whispers and speaks unto me,

"Thou canst only know in thine own dim way

That hour in Gethsemane." |

|

__________________________

THE POET.

|

|

LIKE a great tree

beside the stream of life

The visioned poet stands,

And scatters forth his leaves of thought all rife,

As if from fairy hands.

And down, forever down the stream they float,

And work into the heart,

And there, by virtue of the magic thought,

Can never more depart.

But sleep unseen through all the weary day,

And waken up betimes

In the sweet night to cheer our gloom away

With their most pleasant chimes.

And in the hurry and the fret, the jar

Of restless things they come,

And act like oil upon the tempest's war

Till all the strife is dumb.

The labour of the wood and field, the slim

White clouds within the sky,

Have secrets Nature only shows to him

Who hath a poet's eye.

The unheard music and the gentle tones

Which float along her breast,

Give up their being unto him alone,

To tell it to the rest.

He is the necromancer who hath thrown

Open a wealth untold,

And placed within our hands the fabled stone

Whose touch turns all to gold.

O, noble poet, firm in thy great faith,

And in thy truth and love,

I prize thee as I do the dead, whose death

Has swelled the ranks above.

So in all earnestness my spirit sends

Its homage unto thee;

But this is naught, for from the sky descends

Thine immortality. |

|

__________________________

ON THE STATUES OF

GOETHE AND SCHILLER

AT FRANKFORT-ON-THE MAINE.

|

|

TWO master spirits of

German song, they stand

Each by the side of each; the sculptor's thought

Has guided the sure chisel, as it ought,

And placed the laurel wreath in Goethe's hand.

He holds it with that calm repose of face,

True reflex of his life, and looks straight on;

While Schiller, as if hearing some high tone

Playing within his life, has time to place

His finger tips within the wreath, but lifts

His vision upward; type, too, of his life,

That struggled, through thick clouds of early strife,

To the calm sunshine of all noble gifts.

Two spirits of melody—one broad and wise,

The other pure, and yearning still to rise. |

|

__________________________

SHE'S AN AWFU' LASSIE JENNY.

|

|

SHE'S an awfu' lassie,

Jenny,

No' her like in a' the toon,

For her heid is fu' o' mischief,

And her hair is hingin' doon.

What a faught maun ha'e her mither

Frae the mornin' till the nicht,

But she's awfu' like her granny,

An' that pits wee Jenny richt.

I ha'e tried to coort wee Jenny

But she'll no' ha'e me ava',

She wad raither ha'e a penny

To buy sweeties or a ba',

When I speak o' oor sweetheartin',

Just as lown as lown can be,

Wad ye think it for a moment?

She pits oot her tongue at me.

She's an awfu' lassie Jenny,

Yet a denty, bonnie quean,

An' there's licht, an' love, an' lauchter

A' at ance within her een.

Yet I ken fu' weel her mither

Maun get mony an unco fricht,

But she's awfu' like her granny

An' that pits wee Jenny richt. |

|

__________________________

YARROW.

|

|

THE simmer day was

sweet an' lang,

It had nae thocht o' sorrow,

As my true love and I stood on

The bonnie banks o' Yarrow.

I took her han' in mine an' said,

"Noo smile, my winsome marrow;

The next time that we come again

You'll be my bride on Yarrow."

A tear stood in her sweet blue ee,

An' sair she sighed in sorrow,

"I dinna like the sugh that rins

Alang your bonnie Yarrow.

"It soun's like some auld dirge o' wae,

If chills my bosom thorough,

An' it makes me creep close to your side;

Oh, I dinna like your Yarrow.

"For aye I think on the wae an' dule

That auld, auld sang brings o'er me;

An' aye I see that bluidy fecht,

An' the deid, deid men afore me."

I clasped my true love in my arms,

I kissed her sweet lips thorough,

Her breast lay saft against my ain,

On the bonnie banks o' Yarrow.

"A tear is in your sweet blue ee,

A tear that speaks o' sadness.

Noo what should dim its happy hue,

This simmer day o' gladness?

"The Yarrow rins fu' fresh an' sweet,

The licht shines bricht an' clearly,

An' why should ae sad thocht be ours,

We wha lo'e ither dearly?

"The Yarrow rins, an' as it rins

Nae sadness can it borrow

Frae that auld sang that's far awa',

When I'm wi' thee on Yarrow."

I pu'd a daisy at my feet,

A daisy sweet an' bonnie,

I put it in my true love's breast,

For she was fair as ony.

But aye she sighed, an' aye she said,

"I fear me for the morrow.

Oh, tak' awa' your bonnie flower,

For see, it grew on Yarrow.

"The bluid still dyes its crimson tips,

It speaks o' dule an' sadness,

An' the deid that lay on the gowany brae,

An' woman's wailing madness."

I took the daisy from her breast,

I flung it into Yarrow,

An' doon the stream wi' heavy heart

I cam' wi' my sweet marrow.

Oh simmer months, hoo swift ye flew,

Wi' a' your bloom an' blossom!

Oh Death, how waefu' was thy touch

That took her to thy bosom!

For my true love, sae sweet an' fair,

Lies in her grave sae narrow,

An' in my heart is that eerie moan

She heard that day in Yarrow. |

|

ED.—The Yarrow is a

river in the Borders in the south east of Scotland. A tributary of

the River Ettrick, it is renowned for its salmon fishing.

|

|

__________________________

THE STEPPING STONES.

|

|

WE met upon the

stepping stones,

She blushed and looked at me;

The river turned its short, sharp moans

Into sweet melody.

I heard the music in my heart,

I said, "Sweet maid, I find

That I will have to turn again,

And let you come behind."

Thereat she hung her dainty head,

The river's melody

Grew sweeter, and methought it said,

"The maid will follow thee."

I turned upon the stepping stone,

The maiden came behind;

She whispered in her sweetest tone,

"Dear sir, but you are kind."

"Nay, nay," I said, and took her hand;

"But shall I turn again,

Or wait until a tender band

Be bound about us twain?"

She hung her head, then, blushing, said,

"Dear sir, but you are kind;

If you will cross the stepping stones,

I will not stay behind." |

|

__________________________

ROW, KELLO, ROW.

|

|

ROW, Kello, row frae

rocky linns,

An' through amang thy grassy braes,

Where gowans grow an' hawthorns blaw,

An' sunshine sleeps on summer days.

Slip saftly by the quarry howm,

Where hingin' hazels hap thy tides;

Then murmur through aneath the brig,

An' by the cot where Annie bides.

Row, Kello, row to where the Nith

Half waits to clasp thy floods sae clear,

But leave ahin' the happy soun'

That Annie still delights to hear.

She walks by thee when gloamin' dims

An' darkens doon the vocal glen,

But what her ain sweet thochts can be

Nane but hersel' an' thee may ken.

Row, Kello, row when summer flings

A wealth o' licht the hills alang,

An' row when autumn's yellow han'

Shakes doon the nits the leaves amang.

An' row when winter's rouky breath

Strips a' the cleedin' frae the tree,

But leave to Annie still the thochts

At gloamin' when she walks by thee. |

|

__________________________

THE DOVE.

|

|

A DOVE went up, and

struck the air

Impatiently with all her wing;

I said, "O bird thy journeying

Is like the flight of thought. But where,

"In all the regions of the sky,

When weary, and you wish to roam

No longer, do you find a home?"

And meekly did the dove reply—

"I own no fancy; I am free,

And, shooting through the yielding air,

I look and find that all is fair,

And beautiful and sweet to me.

"And wish, when tired, no sweeter rest

Than drooping down with folded wing

Within a wood whose shadows cling

Across the river's dreaming breast."

"Well said, O bird, whose days are rife

With all the peace of rest and love,

And linked to quiet things that move

Around the orb of poet-life." |

|

__________________________

THE PIPER'S TREE.

|

|

COME in, gudeman, to

your ain fireside,

There's a cauld, cauld grup in the air,

An' the win' blaws snell frae Corsencon,

For the winter's snaw is there.

It sughs down Glenmuckloch Dryfestane glens

Wi' an eerie, eerie soun',

It whussles an' roars in the muckle tree

That stan's afore Nethertoon.

Come in, come in to the weans an' me,

The fire is lowin' bricht;

If ye stan' ony langer there, ye'll get

Your death o' cauld this nicht.

Do you hear me speak? What can mak' him turn

His back on his ain dear wife,

Wha has stood by him through mony a faucht

For fifty years o' her life?

Is he coontin' his purse? Oh, waes me noo,

Oh, wae for my bairns an' me;

The curse that my grannie tauld me has come—

He has sat on the Piper's Tree!

For after she tauld me, when I was a wean,

That, whaever sat by nicht

On the Piper's Tree, took a lust for gowd,

And made it their hale delicht.

An' the sign o' the Piper's curse was this:

That, whaever it micht be,

They wad coont their purse at pleuch or cairt,

Wi' a greedy look in their ee.

Come in, gudeman, for my heart is sair,

Come in to the lowin' licht,

An' "I'll tell ye the doom o' the Piper's Tree,

For the gude o' us a' this nicht.

Langsyne, afore my grannie was born,

On a nicht o' win' an' rain,

Auld Eadie Buchan, the miser, was faun',

Lyin' dead on his ain hearthstane.

He was killed for the sake o' the siller he had,

For he made it his only pride,

But, whaever it was that had dune the deed,

They fled frae the kintra side.

An' years an' years gaed by, until

The tale took anither turn,

An' they said that his gowd was aneath a tree

By the side o' the Laggeray Burn.

But a curse wad be sure to fa' on him

Wha wad try to howk for it there,

For ilk' coin was red wi' bluid, and still

The miser's ghaist was there.

But lang Tam Cringan lauched an' lauched,

An' said, wi' a lood guffaw,

"It's an auld wife's story to fricht the bairns,

As a bogle frichts a craw."

But aye after that he was seen to stan'

By himsel' an' coont his purse,

While the look in his ee was the look that comes

At the back o' the Piper's curse.

In a week after that what a change took place,

For white, white grew his hair;

He never lookit ye straucht in the face,

An' he jokit an' leuch nae mair.

He dwined and dwined on his feet, until

He took to his bed an' lay,

But the neebors whispered, "Afore he dees

He has something yet to say."

So ae drear nicht, as they sat by his bed,

He said, wi' mony a mane,

"Since the nicht that I socht for the miser's gowd

My peace o' mind has been gane.

"An' I canna rest wi' this wecht on my breast,

Sae, afore I steek my ee,

I maun tell ye sichts that I saw, an' the soun's

That I heard by the Piper's Tree.

"For days an' days, like ane in a dream,

I daun'ered oot an' in;

For my heart was set on the miser's wealth,

Though I kenned fu' weel 'twas a sin.

"I coontit my purse ilk' hour o' the day,

An' whenever I heard the clink

O' the siller I faun' my heart grow hard,

An' closer an' closer shrink,

"Till at length, with an aith, I said to mysel',

In the heicht o' greed an' despair,

'I will venture the lastin' gude o' my saul,

For the sake o' the siller there.'

"Sae I slippit oot on a munelicht nicht,

Took a gude stoot pick an' shule,

Stood aneath the Piper's Tree an' heard

The Laggeray Burn sing dule.

"I wrocht, an' I wrocht, as ane will work

Wha works for life an' death,

Till the black sweat fell in draps frae my brow,

An' I scarce could draw my breath.

"But, aye the deeper I howkit, my heart

Grew harder an' harder still;

An' every thocht that cam' into my heid

Was a thocht o' sin an' ill.

"I faun' that if even a brither o' mine

Had come to help me there,

The sin o' his bluid wad been on my heid,

For the sake o' gettin' his share.

"But a' at ance, an' abune my heid,

I heard the bagpipes play,

An' at the soun' the munelicht fled

Frae hill, an' glen, an' brae.

"An' I saw the glint o' an eerie licht,

That seemed like a ghaist to rise

Frae the breckaned heicht o' the steep Knowe Hill,

Where gude Saint Connel lies.

"An' doon it cam' like a wauf o' the win',

Wi' the sugh o' the Laggeray Burn,

An' aye the bagpipes skirled an' played,

But my heid I couldna turn.

"I faun' the sweat rin cauld doon my back,

An' trickle into my shune,

But I hadna the power to lift my heid,

To see wha played abune.

"But, just as that licht gaed flauffin' by,

I saw what made me grue,

A lang, thin shape, wi' its heid bent doon,

An' a red, red mark on its broo.

"An' I saw its han's gang up an' doon,

What they did I couldna tell,

But I thocht they were coontin' the ghaists o' coin,

As I used to do mysel'.

"It glided doon to the side o' the Nith,

Then turned as if to come back,

But the win' took it doon till it sank frae my sicht

On the lang green howms o' the Rack.

"An' aye the bagpipes skirled an' played,

An' looder an' looder grew;

An' aye the hair stood up on my heid,

An' the cauld sweat fell frae my broo.

"Then a' at ance the bagpipes ceased,

While an eerie, ghaistly cry

Rang oot on the nicht, an' took to the air

To dee on the hills ootbye.

" 'Howk on,' it said, 'an' gang deeper yet,

It wants but an hour o' twal';

I wuss ye may licht on the miser's gowd,

For I want to be sure o' yer saul.'

"Then I lookit up, an' abune my heid

(Oh, whatna sicht did I see

In the mirk, mirk nicht by the deein' mune,

On the tap o' the Piper's Tree!)

"I saw twa een that werena like een,

They were red as a lowin' peat;

A pair o' horns that were three feet lang,

An' feet that werena like feet.

"But I saw nae mair, for, wi' ae lood cry

That took the last o' my breath,

I lap frae the hole that was like my grave,

An' I ran for life an' death."

Oh, ye needna lauch at me, gudeman,

For grannie wadna lee,

An' said there was mair than fowk wad own

O' truth in the Piper's Tree.

That nicht Tam Cringan dee'd, an' juist

As they laid him oot in his shrood,

They heard a soun' like the bagpipes skirl,

An' it cam' frae the Laggeray Wood.

Fu' weel did they ken wha was playin' there;

The thocht sent the bluid frae their cheek,

An' siccan a fear was on ane an' a'

That nane o' them daur to speak.

The soun' cam' up like a risin' win'

When the winter nichts are lang,

They heard it skirl at the chimla tap,

Till a voice was heard in the thrang—

"Howk on," it cried, " for the miser's gowd,

Howk on wi' a' your micht;

Had the deid ye watch got my wuss, I ken

Where his saul wad ha'e been the nicht."

The win' fell doon, an' the eerie soun'

Creepit up to the hills ootbye,

An' there they sat wi' the deid at their side

Till the licht cam' into the sky.

It's an auld wife's havers, ye say, gudeman!

But still, to this very day,

When the mune draps owre the Kirkland Hills

Ye can hear the bagpipes play.

But nane daur venture up the burn

To see wha is playin' there,

For they ken o' the curse that is sure to fa'

Wi' its weird baith lang an' sair.

Sae ye needna lauch at me, gudeman,

For my grannie wadna lee,

An' said there was mair than fowk wad own

O' truth in the Piper's Tree. |

|

__________________________

AIMLESS LONGINGS.

|

|

I AM full of an aimless

longing

As I wander about to-day;

I turn from the light and shadow

As they chase each other at play.

I hear a wild bird calling—

A lonely cry from the hill;

And the haunting sense in my bosom,

Grows deeper and lonelier still.

What it can be I know not,

I cannot read it aright;

And I wander as men will wander

That stray from the path in the night.

Is it a sense of something

That to-day still follows me;

That out of my life has vanished,

As a ship goes down at sea? |

|

__________________________

BALLOCHMYLE.

|

|

A SWEET love-song,

whose early touch—

Ere yet the master-hand grew strong

To strike the chords that felt at such

The wondrous magic of his song—

Was with me, speaking soft and sweet

From leaf-clad tree, and from the smile

Of half-hid flowers among my feet,

That summer night in Ballochmyle.

The Ayr was hushed from bank to bank;

Its murmur, coming through the trees.

Was as of fairies when they prank

Their moonlight revels o'er the leas.

It mingled with the tender tone

Of lover's earnest plea and wile,

As I stood listening all alone,

That summer night in BallochmyIe.

There was no breath of wind to stir

The grass that grew beside my feet,

But silent as a worshipper,

When thought and silence are most sweet,

I stood: I felt my heart grow warm

With that soft dew of unshed tears

That comes, when, as beneath a charm,

We slip back into vanished years.

The spot was fair, but fairer still

In that high light which falls from song—

So fair that, bending to its will,

I only did this gentle wrong—

I plucked some grass, a token meet,

To take with me. No idle toil!

Since it perchance had kissed the feet

Of her, the "Lass o' Ballochmyle.''

The night came on, and in the sky,

A little space of which was seen

Between the trees, upon the eye

One star shone out with wondrous sheen.

It wore the tender look of love,

As if some link to me unknown

Had bound it to this spot, and strove

To make this haunted place its own.

Sweet dream! for here love's very soul

Might dwell, and feel no taint of earth,

But wander to its passionate goal,

Or dream, and, dreaming grow to birth.

Here might his feet for ever stay,

And here his heart for ever dream,

Without one wish to roam or stray

Beyond the music of the stream.

The moon rose up, and, all at once,

From leafy branch and trembling grass,

A murmur, like a sweet response,

Came forth, and sweet to hear it was.

And with that murmur came the light,

That flung o'er all a tender smile;

And deepened still the fairy sight

That held me bound in Ballochmyle.

But is there not a softer gleam,

Which is not of the moon, that lies

On grassy bank and wood and stream,

And touching makes them sanctities—

A light that, shining far apart,

Is only for the inner eye,

That sees the glory of that art

Which speaks in burning melody?

Hush! do I wake or dream? for lo!

A spirit wanders up the glen,

And as he comes a deeper glow

Bathes all that lies within his ken.

He moves as in some mood of thought,

And in the glory which he throws

Around him his dark eye has caught

That frenzy which the poet knows.

He leans against a tree, he turns

His eye upon the shining stream,

And in its burning depths there yearns

The first sunrise of passion's dream.

Where have I seen that swarthy face

Which now is radiant with the light

Of that high look that wears no trace

Of earth or death to mortal sight?

Lo! yet another spirit comes

With lighter foot and fairer face,

Each leaf in murmurous music hums

As on she moves with pensive pace.

The Ayr grows hushed, and will not speak,

And only one sweet breath of wind

Kisses the roses on her cheek,

And sways the grass that throbs behind.

She pauses, slowly turns her eye

On him, the poet spirit, bent

In half-adoring ecstasy,

As to some angels heaven-sent.

Then with a low yet tender sigh

She beckons him: they both pass on,

And all the light grows dim, and I

Am left in Ballochmyle alone.

I wake up. Am I still beneath

The spell of all that early tone,

Whose music, like the spring's sweet breath,

Hath made this fairy spot its own?

The star shines through the open space,

The moonlight quivers all around,

And lays sweet hands of tender grace

Upon this consecrated ground.

Oh, early love-song haunting yet

The spot where the immortal trod,

And breathing, where his feet were set,

The music of the singing god.

Oh, maid for ever young! for who,

When caught and held by magic song,

Can feel the years that bear from view

The common lot that plods along?

Ah me! we pass. But through this wood

Our swarthy singer still will roam,

And muse in high poetic mood

Apart from all the years to come.

While she, his sister-spirit, strong

In her unfading beauty's smile,

Will move throughout the land of song,

"The bonnie lass o' Ballochmyle." |

|

__________________________

THINKING OF MICHAEL.

(A Letter from the "Dead."—Upon the tin water-bottle of

one of the dead men brought out of the Seaham Pit, Michael Smith, there

was scratched, evidently with a nail, the following letter to his

wife:—"Dear Margaret,—There was forty of us altogether at 7 a.m., some

was singing hymns, but my thought was on my little Michael, I thought that

him and I would meet in heaven at the same time. Oh, my dear wife,

God save you and the children. Be sure and learn the children to

pray for me. Oh, what a terrible position we are in.—Michael Smith,

54, Henry Street." The Little Michael he refers to was his child

whom he had left at home ill. The lad died on the day of the

explosion.) |

|

IN the chamber of death

underground,

Came these words to touch men to the heart,

Bring tears to the eyes, and a sound

Of a sorrow that strikes like a dart.

Hear you not that low wail coming through

The death-gloom of that chamber so grim?

"I was thinking of Michael and you

When the others were singing a hymn.

"I thought—not of death that would come—

It was nothing, dear wife, unto me;

I was thinking of you and our home,

And how little Michael would be.

My God, what a fate we can view

In this deep vault that drips like our tears!

But still I was thinking of Michael and you,

With the sound of a hymn in my ears.

"Then I thought I would meet him above,

Both at once enter in at the gate,

Clasp his hand, hear his whisper of love,

With no hint of the earth and my fate,

Lead him into the light of that land,

Where no shadow may enter to dim—

All this in the midst of a band

Of my mates who were singing a hymn.

"Oh, pray for me, wife, when at night

Our children climb up on your knee;

When the hearth is still dark from the blight,

Oh, teach them a prayer for me!

Let their voices go up to our God,

Who through this dark shadow can see;

He will hear from the heights of His sinless abode

Their prayers for you and for me.

"Farewell! and afar in the years

That will deaden thy sorrow's deep smart,

And thine eyes only soften with tears

When my name stirs and leaps at thy heart,

You will say, when you think upon me

And this death-cavern, rugged and grim,

'He was thinking how Michael would be

When the others were singing a hymn.'

"Oh, fathers and mothers that peer

Down into that terrible mine,

See ye not, far too deep for a tear,

A love that was almost divine?

That father, waiting for death to come,

But still, in the midst of his fears,

Thinking of poor little Michael at home,

With the sound of a hymn in his ears. |

|

ED.—a massive explosion occurred at Seaham Pit, County Durham,

on the 8th September 1880, claiming 164 lives out of a shift of 230 men.

It happened, without warning, at 2.20 a.m. in the morning, during a

maintenance shift, when no coal was being worked and thus no escape of

explosive gas was expected. The cause seems to have been a shot

fired in an area of stone, where there was a considerable amount of dust

on the ground that was disturbed during the work preparing a 'refuge

hole'; and it was this dust suspended in the air that ignited with

tremendous effect. No one from the immediate area survived; many

others were trapped and died before rescuers could unblock the shafts and

reach them.

See also Joseph Skipsey, "The

Hartley Calamity"

|

|

__________________________

CONNELBUSH.

|

|

I HEAR the winds of

summer rush

Above my head to-day,

As here I sit by Connelbush

To dream one hour away.

Beside the old green walls are seen,

Half hid amid the grass,

Stray flowers that peep out from their

screen

In sorrow as you pass.

The garden lies a wilderness

Of growth untrained and free;

There is no hand to touch and dress

To bounds the life I see.

The walls still stand to mourn and sigh

For mirth that once was there,

In other years when youth was high

And days and nights were fair.

And still the winds round Connelbush

Blow sweet through glen and wood,

As when we heard them with the rush

Of youth through all our blood.

But still they do not seem to blow

With that sweet force we felt

When, in the years of long ago,

Our hearts were quick to melt.

The garden fence is broken down,

Unhinged the garden gate,

The roof of thatch has sunk and flown,

And all is desolate.

There is no welcome at the door,

No kindly voice to greet;

And on the path is heard no more

The sound of human feet.

I hear the tinkle of the stream

That slips beneath the grass;

I hear, and as I hear I dream,

And into visions pass.

I enter through the narrow door,

The fire gleams bright within;

And all, as it was once of yore,

Is full of mirth and din.

I hear the sound of dancing feet,

Of rustic revelry,

Of voices rising clear and sweet—

And each is known to me.

Beside the fire, and in her place,

Sits one to sympathise;

The light is on her kindly face,

And in her kindly eyes.

She watches with a quiet smile

The mirth and pastime there,

And, watching, she is young the while,

Though snow-white is her hair.

Beside her, in the hearth's sweet blaze

And leaning on her knee,

Is one—a woman in her ways—

Though but a child is she.

She, too, is full of quick reply

When laughing questions pass;

And catches with a ready eye

The wiles of lad and lass.

Another, too, who bears a part

In all this rustic life—

True woman of a daughter's heart,

Who art as true a wife.

Thou walkest other paths this hour,

For life's paths so divide;

And thine are full of gracious dower,

With children by thy side.

What can I wish to-day for thee,

If human joys should last,

But that the future years may be

As calm as were the past.

Hush, as I look a strange sad shade

Falls down upon the hearth,

And dame and grandchild slowly fade,

And pass from all the mirth.

Ah, me, that shade is death, and they

Look through its tender haze

With that half-joy that fades away,

And saddens as we gaze.

Fades, too, the sound of dance and song

The last good-night is said,

And up the pathway pass along

The last fond youth and maid.

The twilight sinks, the shadows fall,

A sense of something lost

Comes down and settles over all,

And haunts it like a ghost.

The ashes dwindle in the grate,

The last dull spark is gone,

The walls and roof are desolate,

And here I stand alone.

The winds blow sweet by Connelbush,

They fan my brow and cheek,

And in the pauses, when they hush,

I hear the streamlet speak.

I mark on hills the shadowings

That march in sad array

From clouds that float above, like wings

Of angels flung away.

And from low-lying meadow lands

Along the Nith I hear,

Uprising from haymaking bands,

Sweet laughter swift and clear.

And down the valley, further on,

Lies Sanquhar dim, and grey,

Still guarded by its pile of stone,

That crumbles day by day.

I look, and right in front is seen,

Beyond the wood and stream,

A long and narrow bank of green,

On which the metals gleam.

And up and down, with rush and roar,

Trains crash with seven-leagued stride;

Ah me, this moaning human shore

Must have its iron tide.

But here from lonely Connelbush

All life has fled away,

And nought is heard but winds that rush

And sport with its decay.

No welcome at the door to wake

The silence into mirth;

No sound but that of winds that shake

The weeds upon the hearth.

Farewell, but as I turn, my thought

Perforce is backward set,

And shadows all this lonely cot

With mists of vain regret.

Alas for human dreams that leave,

Instead of after-glow,

Cold memories that pine and grieve,

And sadden as we go.

Till, battling with the years, at last

They sink into decay,

And lie a ruin in the past,

Like Connelbush to-day. |

|

__________________________

A VOICE IS IN THE WIND TO-DAY.

|

|

A VOICE is in the wind

to-day,

And sweet its breath is blowing;

O, welcome summer wind I say,

From where the flowers are growing.

I feel the smell of meadows sweet,

With many blossoms showing,

As if the touch of fairy feet,

Set all their beauty glowing.

I know each spot where violets peep,

I bless them in their growing;

But O their breath is sweet to keep,

When summer winds are blowing.

"What makes them smell so sweet to-day?

Say wind, and good betide thee;"

And the wind came like a child from play,

And laughed and stood beside me.

The wind said, "I am from the hill,

With scents of blossom laden;

But I, to make them sweeter still,

In passing kissed a maiden." |

|

__________________________

THE SORROW OF THE SEA.

|

|

A DAY of fading light

upon the sea;

Of sea-birds winging to their rocky caves;

And ever, with its monotone to me,

The sorrow of the waves.

They leap and lash among the rocks and sands,

White-lipped, as with a guilty secret tossed,

Forever feeling with their foamy hands

For something they have lost.

Far out, and swaying in a sweet unrest,

A boat or two against the light are seen,

Dipping their sides within the liquid breast

Of waters dark and green.

And farther still, where sea and sky have kissed,

There falls as if from heaven's own threshold, light

Upon faint hills that, half-enswathed in mist,

Wait for the coming night.

But still, though all this life and motion meet,

My thoughts are wingless and lie dead in me,

Or dimly stir to answer, at my feet,

The sorrow of the sea. |

|

__________________________

ONE STAR ALONE.

|

|

ONE star alone from the

blue sky

Looks down upon the simple stream,

With such a quiet, loving eye,

That I perforce must dream.

And so I wish, if my rough brow

Should seam and furrow with the strife,

The star that leaps and kindles now

Might light my path of life.

That I, when weary with the fight,

And wishing for a rest at length,

Might look and draw from out its light

A comfort and a strength.

And gird my soul with stronger powers

To fight the lower thought and deed,

That agitate this life of ours

As winds will shake the reed.

But still in moods of calmer tone,

I feel a longing to retire,

And watch the broad world all alone,

And plod, but not aspire.

For I have thought, and still I think,

'Tis wiser that our lives should be

Like this fair stream within its brink,

So quiet, so calm and free.

Or like that star above, which beams

For ever down in holy mirth,

Than wed the heart to idle dreams,

Whose goal is still the earth.

O let me spend my little hour

In all the calm that Nature gives—

Profuse in plenitude of dower

Where each mute being lives.

For in the hush of her sweet face,

The soul will burst its earth-forged hands,

And wing its flight to purer space

In other purer lands.

Therefore it comes that still I love

The dim, sweet twilight, and the light

That comes, like whispers, from above,

And shines on me to-night. |

|

__________________________

A SOUND IS IN MY EAR TO-DAY.

|

|

A SOUND is in my ear

to-day,

And playful fancies with it throng;

It follows me and all the way

It haunts me like a snatch of song.

I know not what it all may mean,

I dimly ask myself, and say,

"Something that thou hast heard or seen,

In some forgotten summer day.

"A summer day when paradise

Lay near to earth as near could be,

When all the hills were red with fire,

And heather humming with the bee."

And it is this; an upland gleam

Of sunshine such as warms and thrills;

The tinkle of a quiet stream,

That broke the stillness of the hills. |

|

__________________________

THE LIFE-BOAT.

|

|

THE sea, as by some

inner demon stung,

Hath burst its glassy prison, and on high

A thousand waves in black despair are flung

In foaming supplication to the sky.

They yawn with fangs half-hidden by the spray,

And hiss and roar with madness in their breath,

And, blind with hate, for ever seek their prey,

To drag it downward to their gulfs of death.

The winds are in high holiday; they shear

Their way through spray and cloud, and high and

strong

Put forth their mighty strength until they bear

The billows downward as they roar along.

Between the waves there seethes a mimic hell,

Gaping with foam-flecked maw to swallow all—

For who can quench such thirst? or weave a spell

Over the anger of their carnival?

Lo, how they toss, as if from hand to hand,

That ship far out where help seems all in vain,

And thin white faces turning to the land

Whose only hope is to despair again.

Their ship is but a plaything for the sea,

A speck for winds to buffet and to toss—

Who will put out! although his life should be

Within his hand, to fling away like dross?

"Out with the life-boat! Willing hands are here,

Stout muscles, ay, and stouter hearts to fight,

Give way, give way, and with a voice of cheer,

We must save lives before the fall of night."

Between them and the ship that staggers on,

The waves like liquid phalanxes of steel

Rise up to bar their way with hiss and moan,

Till the staunch life-boat shakes from deck to keel.

But still she cleaves her way through stormy rifts;

In front the swooping sea-gulls show her path,

Until she seems a speck that sinks and lifts

Amid a thousand howling gulfs of wrath.

And those who stand in horror on the shore,

Watching the hell of shaking darkness there,

Hear their hearts throb an answer to its roar,

Now touching hope and now again despair.

Will they come back? The moments lengthen out,

Until they seem like hours to those who wait.

At last that far-off speck has put about;

But who can say what yet shall be its fate?

The storm, as if unconscious of defeat,

Re-marshals all its seething ranks of waves,

And, led by shrieking winds with foam-hid feet,

Swoops on the staunch true hearts, and roars and

raves.

But battling still with every wave that strives

To bear them back with rushing surge and sweep,

They gain the shore at last with human lives

Wrenched from the white teeth of the tigerish deep.

Brave hearts beneath rough bosoms! Well we knew

How ye would rise to God and Christ's own plan,

And stand heroic in the tasks ye do.

Grand is the sea, but grander still is man!

ED.—see also Samuel Layock,

A Tribute to the Drowned

and Prologue; and

Thomas Clounie's The

Rescue |

|

__________________________

WILD FLOWERS FROM ALLOWAY AND DOON.

|

|

NO book to-night; but

let me sit

And watch the firelight change and flit,

And let me think of other lays

Than those that shake our modern days.

Outside, the tread of passing feet

Along the unsympathetic street

Is naught to me; I sit and hear

Far other music in my ear,

That, keeping perfect time and tune,

Whispers of Alloway and Doon.

The scent of withered flowers has brought

A fresher atmosphere of thought,

In which I make a realm, and see

A fairer world unfold to me;

For grew they not upon that spot

Of sacred soil that loses naught

Of sanctity by all the years

That come and pass like human fears?

They grew beneath the light of June,

And blossomed on the banks of Doon.

The waving woods are rich with green,

And sweet the Doon flows on between;

The winds tread light upon the grass,

That shakes with joy to feel them pass;

The sky, in its expanse of blue,

Has but a single cloud or two;

The lark, in raptures clear and long,

Shakes out his little soul in song,

But far above his notes, I hear

Another song within my ear

Rich, soft, and sweet, and deep by turns—

The quick, wild passion-throbs of Burns.

Ah! were it not that he has flung

A sunshine by the songs he sung

On fields and woods of "Bonnie Doon,"

These simple flowers had been a boon

Less dear to me; but since they grew

On sacred spots which once he knew,

They breathe, though crushed and shorn of bloom,

To-night within this lonely room,

Such perfumes, that to me prolong

The passionate sweetness of his song.

The glory of an early death

Was his; and the immortal wreath

Was wrought round brows that had not felt

The furrows that are roughly dealt

To age; nor had the heart grown cold

With haunting fears that, taking hold,

Cast shadows downward from their wing,

Until we doubt the songs we sing.

But his was lighter doom of pain,

To pass in youth, and to remain

For ever fair and fresh and young,

Encircled by the youth he sung.

And so to me these simple flowers

Have sent through all my dreaming hours

His songs again, which, when a boy,

Made day and night a double joy.

Nor did they sink and die away

When manhood came with sterner day,

But still amid the jar and strife,

The rush and clang of railway life,

They rose up, and at all their words

I felt my spirit's inner chords

Thrill with their old sweet touch, as now,

Though middle manhood shades my brow;

For though I hear the tread of feet

Along the unsympathetic street,

And all the city's din to-night,

My heart warms with that old delight,

In which I sit and, dreaming, hear

Singing to all the inner ear,

Rich, clear, and soft, and sweet by turns,

The deep, wild passion-throbs of Burns. |

|

__________________________

A BLACKBIRD'S NEST.

(In the month of May, 1884, might be seen, at the Forth

Bridge Works, South Queensferry, a blackbird sitting on her nest, which

was built on an elevated projecting beam in the engineering shed, in close

proximity to the driving-shed, and immediately above a powerful

steam-engine.) |

|

SHE sits upon her nest

all day,

Secure amid the toiling din

Of serpent belts that coil and play,

And, moaning, ever twist and spin.

What cares she for the noise and whirr

Of clanking hammers sounding near?

A mother's heart has lifted her

Beyond a single touch of fear.

Beneath her, throbbing anvils shout,

And lift their voice with ringing peal,

While engines groan and toss about

Their tentacles of gleaming steel.

Around her, plates of metal, smote

And beat upon by clutch and strain,

Take shape beneath the grasp of thought—

The mute Napoleon of the brain.

She careth in nowise for this,

But, as an anxious mother should,

Dreams of a certain coming bliss—

The rearing of her callow brood.

Thou little rebel, thus to fly

The summer shadows of the trees,

The sunlight of the gracious sky,

The tender toying of the breeze.

What made thee leave thy leafy home,

The deep hid shelter of the tree,

The sounds of wind and stream, and come

To where all sounds are strange to thee?

Thou wilt not answer anything;

Thy thoughts from these are far away;

Five little globes beneath thy wing,

Are all thou thinkest on to-day. |

|

__________________________

ONE RED ROSE.

|

|

ONE red rose you took

from my hand—

O the light was sweet that summer day—

One red rose from her queenly band,

That was far too sweet to pine away.

"Come I will pluck thee," I said to the rose—

O the light was sweet that summer day—

"And give thee to one who is pure, God knows,

To wear thee though blooming from May to May."

I plucked the rose with a leaf or two—

O the light was sweet that summer day—

Rose bloom on the breast of one who is true,

Whatever her sisters may hint or say.

Then the rose made answer, "What if I fade"—

O the light was sweet that summer day—

"Fade on the breast on which I am laid,

And my beams grow dark in their sad decay."

Then I thus made answer and said to the rose—

O the light was sweet that summer day—

"Die, and the breath of your incense grows

A memory sweet, that shall last for aye." |

|

__________________________

THE POET'S VISION.

|

|

THE poet looks on human

things,

And, as his mood is, so he sings,

And lets his fingers touch the strings.

And as they stray the chords along,

He gives the passionate lover song,

And greater strength to help the strong.

He lifts the weak; with flashing eye,

He launches bolts at tyranny

That slowly withers ere it die.

When war looms like a red eclipse,