|

[Previous page]

CHAPTER LXXXIII.

AMONG THE FISHERMEN OF CROMER.

(1867.)

IT is at once incredible and amusing to contemplate

the primeval spiritual subjugation which parts of this little island are

still under. I was wandering in 1867 on the stormy coast of Cromer.

The boisterous sea visible there was once covered by cliff and forest.

Druidical temples, Aryan altars, villages and churches had all been beaten

down by the fierce waters which now roll over their sites. The noble

church of lofty arches and majestic towers which now stands in Cromer

would have been swept away ere now had not a stout sea wall protected it.

The great ocean, being free, had no doubt suggested to the inhabitants

round about that thought ought to be free also. I had never been in

the place, but on the morning of my arrival it was noised abroad that I

was the guest of a Quaker of repute thereabout. On Sunday I attended

church. In a new town I take the first opportunity of hearing the

most distinguished preacher in it. Preachers of different

denominations often utter noble sentiments in a noble way, and hearing

them enables one better to appreciate the eclecticism of piety. The

preacher at the church was a grey-headed, dignified ecclesiastic in the

maturity of his powers. He was a dean who preached. He said

that there was a class of persons of high character, of perfect

intellectual probity, who had that living morality which bound society

together. Yet they professed not the Christian name.

Nevertheless, it must be observed that, while morality bound man to the

world, it was spiritual life which bound man to God. The sentences

were clearly cut, as though chiselled by the hand of Woolner. Nor

were the sentiments taken back again in any part of the discourse, as is

often the case with some preachers. One often hears a fine

concession at the beginning of a sermon which is explained away at the

conclusion.

The next day it was represented to me that many inhabitants

of the town, and especially the fishermen, would like to hear from me a

lecture on the "Orators of the English Parliament." A messenger was

sent miles away to the nearest printing press, and early next morning, as

I went down to the beach, I found neat little placards in every shop

window announcing my lecture for the evening. In some windows which

faced the town two ways, placards were exhibited on each, announcing that

I would speak in the evening. Outside the Bible Society's Depot one

of the bills appeared. So amicable was everything, I thought I had

alighted in an unfrequented corner of the Millennium! The fishermen's room

was readily granted by two of them who had authority over it. It was

in that room that an eminent member of Parliament, Charles Buxton, used to

deliver annual summaries of Parliamentary proceedings, which ranked among

the classics of political criticism. He was dead then; and a

memorial window of great beauty of colour and design, which I was told

cost a thousand guineas, had been put up in Cromer Church to his memory.

The clouded and chastened light which passed through the window recalled

those fine sentiments he used to express, in which philosophy had softened

and variegated the fierce light of the controversies of his day.

Before noon a great change had come over Cromer; there was

consternation in the place. Muffled whisperings were heard behind

every counter. The vicar had been in the town. The bill on the

Bible Society's door had attracted his attention. He did not know

me, but he knew I was not one of the apostles. Though my name is

partly Biblical, the vicar had the announcement bearing it removed.

He went to the shopkeepers and requested them to take the bills from their

windows, and not to go to the lecture. He admitted my subject was

not in itself objectionable, but then I might say something else in

speaking upon it. He was told that I regarded it as a breach of

faith to announce one subject, and, after inciting people to come to hear

that, to speak upon another. Whether the vicar was convinced, I know

not; but, as he did not call again at the places he visited to reverse his

request, the bills were not replaced, and by the afternoon not a single

copy was to be seen anywhere in the town. Had Mr. Buxton, whose

guest I had been, been living at hand, things would have been different.

In the meantime I composed, in case the fishermen had a

choir, a variation of one of Byron's Hebrew Melodies—beginning, as they

say in chapel, at the second verse:

|

"Like the leaves of the forest when summer is green,

Placards in the windows at sunrise were seen;

Like the leaves of the forest when autumn has blown,

The placards at sunset lay withered and strown.

The vicar of Cromer came in with the blast,

And spoke at the door of each shop as he past;

And the hearts of the keepers waxed deadly and chill;

Their souls but once heaved and thenceforward grew still." |

When I returned from a tour of inspection, I sent word to the fishermen

who had let their rooms to me, that if they thought anything would happen

to their families through their act, they were quite at liberty to recall

it. I thought it likely that the vicar might be the almoner of many

kind-hearted and wealthy families in the neighbourhood, and the people

might fear being passed over when they wanted help in the hard seasons

that befell them. "Tell the men," I said, "that I am no pedlar of

opinions; I do not hawk my principles about the country; and if Cromer

would rather I should not speak in the town, I had no wish to speak to

unwilling ears."

The stout fishermen probably reflected that they earned their bread in the

tempest, by day and by night, holding their lives in their own hands,

while the vicar passed his days secure from harm, and that they would get

through my lecture as they had through other storms. Hence they

answered "they should light their best candles for Mr. Holyoake, and make

their room as bright and cheerful as they could, if he chooses to come."

When nightfall arrived, I marched through the village with my host (whose

Quaker blood was a little stirred) to lecture. Not a soul was moving

in Cromer. Nearing the rooms, we observed a solitary man emerging

from a cottage in the direction of the Lecture Room. His back was

made visible by a penny candle in the window. "There does not

appear," I said to my friend, "any great stampede to the lecture, but I

shall deliver it to you, and our friend, whose back we have seen, should

he arrive there." On entering the room I was astounded by an immense

shout of welcome. The fishermen were there in force. A

respectable inhabitant of the place was voted to the chair, and a gracious

little speech of introduction was made by the gentleman, Mr. Kemp, whose

guest I was.

I delivered my lecture. As I explained the difference

between oratory and mere public speaking, and the characteristics of

Bright, Gladstone, Disraeli, Lowe, Bernal Osborne, Buxton, Sir Wilfred

Lawson, Stansfeld, and others, and pointed out the gradations of that art

by which men climb on phrases to power, signs of discernment arose

sufficient to satisfy any speaker. A reverend visitor, Mr. Valpy,

whose father was a great classic authority, made a neat little speech at

the end.

We said not a word about the vicar. I made no allusion

to him, direct or indirect. It is a long time since those little

peculiarities of the ecclesiastical mind, which he had displayed, affected

or concerned me; and the audience imagined I did not notice what he had

done. I doubt not he was a kind-hearted gentleman to whom many have

been indebted for words of counsel and acts of humanity. He was,

perhaps, a little apt to forget that the people of Cromer were citizens as

well as Christians, and had a right to know what affected them as

Englishmen—that they needed to understand the secular merits of those

great men who influence their destinies and make the English name

distinguished on the earth. The Cromer men had no doubt reasons for

respecting the vicar in removing the placards which were distasteful to

him, and respected themselves by giving a courteous hearing to what a

stranger had to say to them.

In any other town in England it is necessary to advertise a

lecture two or three days; but in Cromer it is sufficient to advertise a

lecture for three hours, and this may have been the reason why they took

the placards out of the windows at midday. However, to the

inexperienced visitor, it seemed that Church courtesy in Cromer had

contracted the qualities of the East wind, and dictation of the Romish

type, which many thought obsolete in England, was still in force in that

remote corner of East Anglia.

CHAPTER LXXXIV.

STORY OF THE LIMELIGHT ON THE CLOCK TOWER.

(1868.)

DURING several pleasant years I was secretary to a

member of Parliament. His residence being at a considerable distance

from the House of Commons, he had no means of knowing when "the House was

up." Some days there would be an early "count out." Most

members daily leave the House during what is termed "dinner hours" to

dine, but it sometimes happened that the House would be counted out in the

dinner time. Then the return journey to the House was needless.

A member in constant attendance at committees and Parliament would be glad

to absent himself until later in the evening, when a division in which he

was interested might be taken. But though the House might adjourn

before the usual time; there was no means of discovering this until he

drove into sight of Palace Yard. At that time the limelight was

coming into use, and I thought it might be made available to prevent this

inconvenience to members. The present Duke of Rutland was then at

the Board of Works, and I addressed to him a letter on the subject which

remained some years in the archives of the Board of Works, and is probably

there now. I have no copy of the letter, but I well remember its

purport. It was to this effect:—

"Being secretary

of a member of Parliament, I have observed that considerable inconvenience

arises by members having no means of knowing when the House is up, at

times when they are unable to foresee it. There are no means by

which a member can know it, unless he provides some one to send him a

telegram to an address which he would have to renew every night, according

to the place where he expected to be after leaving the House sitting.

If he dined at one of the great clubs, he would learn when the House was

up there, by members coming in who had recently left the House, or from

the arrival of the hourly report of the proceedings in Parliament.

But he might be dining four or five miles away, and must drive to one of

the clubs to get the information. It is true that in Palace Yard gas

lights, which have three arms, have only the centre one left burning—to

indicate to persons arriving there that the House is up. But any one

must drive to the bottom of Parliament Street before the single light can

be discerned. It is a probable calculation that many members in the

course of a session drive five hundred miles before they can reach Palace

Yard to learn that the House is up. Reporters and others who have

business with members at the House at night are subject to similar

inconvenience. All this might be prevented if a limelight were

placed at the summit of the Clock Tower. It could be seen six or

seven miles in most directions, and members could learn at will whether

the House was sitting or not."

This letter was longer than would seem necessary; but it was needful to

explain in detail the inconvenience to which members were subjected which

might be so simply obviated. It was necessary to show that all the

existing means of information were taken into account by the writer, for

if any one had been omitted the suggestion might be thought based upon

insufficient information—the official mind being always quick to show that

there is no necessity for doing what it does not want to do. Lord

John Manners, the name by which the Duke of Rutland was then known,

acknowledged the receipt of the communication, but without indicating

whether it would be considered. Nothing came of it until Mr. Ayrton

became Commissioner of the Board of Works. Though he excelled all

Ministers in making himself unpleasant in debate, he also excelled in

being the most vigilant of servants of the public in Parliament, being

tireless in his attendance and reading more Parliamentary Papers than any

four members. He found my letter in the pigeon-holes of the Board of

Works, and put up the limelight on the Clock Tower, which has made the

House of Parliament as it were a beacon light visible all over London

during the night sittings. An article upon it in The Times,

after Mr. Ayrton had ceased to be Commissioner, giving a description of

this Tower light, began by the remark that "a former Commissioner of Works

found the suggestion in the office." The article was evidently

written by a well-informed but reticent writer. It implied that the

Commissioner who put up the light did not originate it, but it was not

said how the suggestion came into the office, or who sent it there.

CHAPTER LXXXV.

PARLIAMENTARY CANDIDATURE IN BIRMINGHAM.

(1868.)

MY second candidature was in Birmingham. It

was constantly said that the working class had no reasonable measures to

propose which the middle class would not pass. This was not, and is

not, true; for the master class no more feels as the workmen feel than the

old aristocratical class before 1830 felt, or as the middle class proved

they did, when afterwards they came into power. And if it were true

that the middle class would now do all the working men want, it is better

that the working men should do it for themselves. For these reasons

I sought the opportunity of addressing my own townsmen, to whom I could

naturally speak with most freedom, upon the conditions and consequences of

working-class representation.

In my address delivered in the Town Hall I said—

"More than thirty years ago I was a

member of your Political Union, and since

that time there has been no combination (sometimes called "conspiracy") in

this country to bring general enfranchisement about, which I have not, by

speech and pen, advocated without intermission. Now we have a

considerable extension of the suffrage, there are things of evil to

cancel, and conditions of progress to create.

"We have, though limited, a 'political commonwealth' at last,

and one result is that working men will, sooner or later, find their way

into Parliament. Venturous of it myself, it is my townsmen whom I

address. My ancestors lie here; I know most of, and naturally care

much for, Birmingham. In all my writings I have looked on public

affairs in the light of the workshop. A Democracy is a great

trouble. Everybody has to be consulted. The Conservative is

enraged to have this necessity put upon him; the Whigs never meant it to

come to this; and I am not sure that many of the Radicals like it.

"Several things will happen now.

-

"The Irish Church will go. Well I remember the

horror with which the news was received in the workshops of this town of

the massacre of Rathcormac, when a clergyman of the Irish Protestant

Church had the sons of the poor Widow Ryan shot before her eyes for the

non-payment of tithes. The middle class mother cannot feel

resentment as a poor woman can; she can afford to pay tithes, and no

dragoon shoots her children down. But Widow Ryan's sons were

labourers—they belonged to us. The shriek of the mother reached

us. We in England could do nothing to avert or avenge their

murder. But let us not have the baseness to forget it. Now

that slow, tardy, long-lingering retribution has put the Irish Church in

the noose, let its hope it will be allowed a good drop.

-

"We shall have compulsory education. There is no ascendency for

the people without sense. We live in a world where the battle of

life can no longer be fought by fools; and the child who is turned out

into it ignorant is bound, hand and foot, in the conflict. We

shall put away with contempt that pitiful, fitful, partial, mendicant

instruction with which voluntaryism has cheated and degraded us so long.

-

"Pauperism will be put down as the infamy of industry. A million

paupers—a vast standing army of mendicants—in the midst of the working

class, depending for support upon the middle class, is a reproach to

every workman now. Every law which deprives Industry of a fair

chance must be attacked; whatever facilitates the accumulation of

immense fortunes and tends to check the natural distribution of property

must be stopped.

-

"We shall have the ballot. Open voting is merely an insolent

device for getting at those electors who do their duty. The

poll-book is a penal list, first made publishable by those who intended

to act upon it—and it is acted upon by all who are enraged at defeat."

It does good to create a popular belief that the day of progress has

arrived; that men need no longer despair of improvement, or seek to obtain

it by conflict of arms, as they were formerly justified in doing under the

hopelessness of obtaining it by reason. In my address I ventured to

say that the Irish Church would go; that we should have compulsory

education; that pauperism would be regarded as the infamy of industry;

that elections would be decided by ballot. I had heard the four

things I had spoken of, hoped for, agitated for, and they seemed no

nearer, and were believed to be no nearer, than the right of women to sit

in Parliament is now. Yet each of these things, then regarded as

words of Utopian enthusiasm, have come to pass.

The object of my being a candidate at Birmingham was to test

and advocate the question of working-class representation. At that

time there was no strong feeling on the part of the working class in

favour of the representation of their order. Had I sought I could

have obtained a sufficient support from Conservatives to have embarrassed

the prospects of Mr. Bright or his colleague, and the Conservatives would

have obtained the credit of supporting a principle for which they did not

care and would disown when their own end was served. I might have

obtained some publicity useful to a candidate by such an alliance, but it

never seemed to me to be any more right in politics than in morals to do

evil that good may come. For thirty-six years the representation of

Birmingham had been in the hands of the middle class, and though the

working class were twenty times more numerous than they, it had never

occurred to the middle class that the industrious majority were entitled

to any personal representation. Certainly they never offered or

facilitated it.

CHAPTER LXXXVI.

A DANGEROUS VISITOR.

(1868.)

A FEW years ago, London was startled by the

discovery of a murder in Whitechapel which recalled the Red Barn murder of

Maria Martin, by William Corder, half a century before. A woman was

shot in the rear of some business premises in Whitechapel and buried

there, and her murderer, one Wainwright, was caught in the streets twelve

months later, conveying the body to another hiding-place.

Some time previously a public writer, for whom I had much

regard, became unwell. One day a lady came to me at Cockspur Street

saying that he was very ill, that she was his wife and needed aid for his

succour. She met my offer to visit him by assuring me that he had a

malignant fever, and I had better not call. This was to deter me

from calling, but I did not suspect it. Soon after she came again in

deep mourning, in the character of his widow. She was a handsome,

voluptuous woman, with great dramatic talent. Her speech, tears, and

gestures were very eloquent, and I promised to ask for subscriptions for

her. This entertaining applicant gave me to understand that she had

been upon the stage in earlier years, and certainly she showed

qualifications for acting which warranted what she said. I knew that

my lost friend, who was really dead, had at one time £30,000 in a public

company, which yielded 10 to 12 per cent., when he lived opulently in a

house in Piccadilly. Afterwards his income fell to zero. In

his prosperous days he had given eighty guineas for a jewelled watch, and

presented it to Samuel Bailey, of Sheffield, in testimony of appreciation

of his philosophical writings.

In the end I fulfilled my promise to the distressed lady in

black, and published the substance of the story told to me by her.

The eventual result was some £40 or £50. The first and second £5 I

remitted to her. The lady paid me a further visit of thanks, and

asked me to call upon her and take breakfast at a suburban cottage, at

which she resided with a female friend, as it would save my time in

writing, and I could bring any further subscription which might be to

hand. Not wishing any personal acquaintance, which might raise

expectations of aid beyond my means of procuring, I asked my brother

Austin to make a call at his convenience, and leave further remittances

for her; and sometimes a clerk in my employ was sent. I never went

myself.

It was fortunate I did not. On the apprehension of

Wainwright, I saw in the papers accounts that his brother—who was

afterwards transported for his complicity in the murder—was supporting a

mistress, and was frequently at the very house to which I had been

invited. Had I accepted the invitation to breakfast, I might have

been found there by the police officers who went to the place in search of

the brother. As the murderer was a lecturer at institutes of the

kind I had promoted and been present at myself, my intimacy with him would

have been inferred. Had my name been mentioned as that of a visitor

at Rosamond Cottage when the address with other interesting particulars

were published, I should have found it difficult to persuade everybody of

the disinterested nature of my visits, especially as I could only have

explained that my business there was to take money to a lady who had

invited me there. My brother had simply called and left the sums I

gave him, and neither of us suspected that she was not the wife of my

friend.

Before the Whitechapel affair transpired, the enterprising

pretender had written to several public persons on her own account.

As it was my practice always to print in the paper I edited all sums for

whatever purpose sent, the "widow" could see who were the friends who had

answered my appeal, and she wrote to them and others whom she thought had

knowledge of her alleged husband, enclosing what I had written upon him on

her behalf. She was what the Scots would call an "ingenious body."

All her letters to me bore a deep mourning border. Several members

of Parliament wrote to me to ask whether they were warranted in giving

money. In my replies I said I had no knowledge

of the new applications made to them, nor was there any public claim on

them, though I understood there was need of help. Several cheques

were sent to me for her. When I found that I had been misled, I gave

notice to all who afterwards wrote to me, and publicly cancelled my appeal

and informed the applicant to that effect.

|

|

|

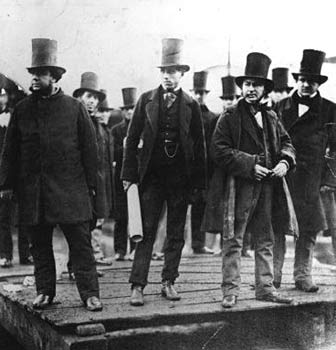

Sir Alexander Cockburn

(1802-80) |

The judge at the trial of Wainwright was Lord Chief Justice Cockburn.

The summing-up of some judges is often so learnedly elaborate, involved,

dreary, and inartistic, that it is a species of penal infliction on the

jury and only merciful to the doomed, upon whom it acts as the drugs given

to the Suttee, which stupefies and makes insensible to the fatal fire.

Sir John Holker, as Attorney-General, conducted the prosecution. Sir

John was a Conservative. It was frequently said there was a good

deal in him, but it did not come out on this occasion. Mr. Moody

made the speech for the defence, in which he said nothing wrong and

nothing strong. There was no glamour of light, or pathos, or

ingenuity in any one.

But when Lord Cockburn rose, the hand of the master appeared.

The ornateness which he sometimes showed in speeches out of court was

chastened down. His sentences were expressed with pure nervous

force. Nothing was repeated, no phrase nor even idea recurred.

The story of the evidence was clear, direct, vivid, brief, complete, and

conclusive. The first sentences of the summing-up against Wainwright

had death in them. The jury could see, as in a panorama, the

perpetration of a foul murder; the source of the blow, and the ghastly

procedure of successive concealments, as plainly as Hamlet displayed the

process of the death of his father to his mother and the king. In

sleuth-hound sentences the stealthy steps of the brutal, calculating

murderer were tracked. Wainwright must have seen the noose in every

passage. Lord Cockburn's address to the jury was an unequalled piece

of forensic reasoning, so far as any charge of the kind has come within my

knowledge. Its coherence was not only evident to the jury—it was

never out of sight. It had picturesque terms which had colour in

them. The crisp, penetrating voice of Cockburn suited the finished

structure of his address. Juries charged by him were instructed; the

prisoner at the bar, who had taste, was afterwards proud to have been

condemned with such classic art, and the sentiment of the Court was raised

above the level of crime by the genius of the judge.

CHAPTER LXXXVII.

REPORTING SPEECHES WHICH NEVER WERE MADE.

A GOOD deal of reporting has fallen to me in my

time, chiefly of the descriptive kind. During several years that I

had opportunity of hearing nightly the speeches made in Parliament, I

found that all the new ideas expressed there could easily be taken down in

long hand, since they occurred seldom and were far between. A

newspaper, not having space to report everything said, might entertain and

much instruct its readers by giving merely the new ideas of the debates,

or remarkable ways of presenting a familiar case. Once a Cabinet

Minister, who was going into the provinces to make a speech he wished to

see reproduced in London papers, asked me what he should do to secure that

what he said should not be open to misinterpretation. I answered

that, if he was sure of saying exactly what he intended, he might ask the

editor of the leading local paper to send a reporter to take down his

speech exactly as he made it. Good stenographers so abound that he

would get what he wanted. But were he doubtful of being quoted at

full length in the London press, he had better take a summary reporter

with him, since a verbatim reporter, by his habit of literalness, would

lack the faculty of bringing into focus the genius of a speech. To

produce a telling summary the reporter need not be able to make the

speech, but he must be able to measure the mind and discern the purpose of

the speaker.

When in America in 1879, I found in some parts a class of

Reversible Reporters. After an interview I found next day in the

paper sentiments put down to me the very reverse of what I had expressed.

Once I tried the experiment of saying the opposite of what I meant, and

next day it came out all right. It was not perversity nor incapacity

which misrepresented me, it was owing to professional confidence in young

reporters that they knew better than any speaker did what he ought to say.

Once a friend of mine, a Jew, who knew this world as well as

the Talmud, was the proprietor of a newspaper in a country town, within an

hour's ride from London, asked me to come down and give an account of

laying the foundation stone of a new town building and report the speeches

at the banquet which was to follow at night. Some members of

Parliament came down with whose ways of thought I was familiar, and I made

summaries of their speeches which I knew they would be willing to

circulate among their constituents. If the object is to promote the

circulation of the paper, the effective portion of what a speaker says

must be brought out, or there will be no orders for copies sent to the

office. A reporter may make a clever report of a speech and prefix

it with the remark that "the meeting was small." There are no copies

of that paper bought by the speaker or his friends for circulation.

If the hall is crowded it is well to say so. But no public persons

care to circulate information that few care to listen to them. If

the object is to discredit a speaker the question is one of policy not

circulation.

Now, there was a rival paper in the town to which I went.

The proprietor of the paper I represented wished his paper to excel that,

which was not difficult, as it was sleepy and unenterprising. So I

wrote a leader upon the speeches at the stone-laying. A speaker who

has ability is pleased to see it discerned and handsomely acknowledged.

A man who acquits himself well may without vanity be pleased with the

credit he has fairly earned; and he who does not excel in expression may

have merit of character and purpose to which it is the interest of the

public to accord recognition.

The banquet in the evening was prolonged and boisterous.

No reporter was present from the rival paper and I was instructed to

report the speeches. On seeing the composition of the guests, I

consulted with my Jewish friend, who, like all his race, was shrewd and

foreseeing. We examined the toast list and then I inquired the

characteristics of the speakers, their manner of mind, peculiarity of

expression and antecedents of family, public service, and other

particulars. One old farmer was reputed to represent a generation of

predecessors who had held the same land from the Norman Conquest. By

the time the toasts began the whole company was more hilarious than

coherent. Some never could speak in public, and little was expected

from them. A few when they began to speak were unable to stop.

Some had forgotten what they intended to say, and others had nothing to

forget. Some could speak better before the banquet began than after,

and some acquired boldness in consequence of it, and made up by audacity

what they lacked in relevance. By eleven o'clock I had sent out

speeches for them all, and by midnight their orations were all in type,

and the paper was out in the early morning. The town was astonished

at the enterprise to which it was unaccustomed. The principal orator

had a speech of some brightness to read at his breakfast, of which he was

unconscious when he retired to rest. My friend the proprietor of the

paper had misgivings when he read the report. He said the town would

be surprised that such speeches were made. I answered, "the town

was not present. The guests who did not speak were not in a

condition to know what was said, and, take my word for it, no speaker will

disown what he is reported to have said." And no one did. As a

leader upon the proceedings of the day confirmed and illustrated the

report by descriptive characteristics of the speakers, which the town knew

to be true, my friend received many congratulations on the variety and

vivacity of that issue of his Gazette. The office was not

rich, and for all the writing? from midday till midnight my remuneration

was but thirty shillings, but I served my friend and increased for that

week the reputation of his paper and its commercial value when he

transferred it, as it was his intention shortly after to do.

"Reporting speeches which never were made" is a title open to

the objection of being incomplete. The speeches were made, but not

in the manner which met the public eye. Two or three of the festive

orators had sagacity and brightness, though, on that occasion, not of the

consecutive kind. Every provincial assembly of speakers furnishes

instances of native wit or idiomatic humour. If these points are

preserved in the report of the proceedings, an interesting monograph of

the meeting is the result. Every night in Parliament occur notable

relevant passages, occasional flashes of common sense, sometimes overlaid

with words, and sometimes insufficiently expressed, of which an epitome

would be good reading. Every day the Parliamentary reports of

speeches presents them in a more effective form than the hearer was

sensible of during the delivery. When The Times sought to

destroy the popularity of Orator Hunt of a former day, it reported his

speeches verbatim. There are many speakers in Parliament who would

suffer in public estimation if their repetitions and eccentricities of

expression were recorded. On one memorable occasion the Morning

Star reported a passage from a speech of Mr. Disraeli's, with ail its

bibulous aspirates set forth, which few forgot who read it. It was

on the night of his famous financial speech when Lord John Manners carried

into the House five glasses of brandy and water to refresh him—which got

at last into his articulation. The late Sir John Trelawny told me

that he had preserved notes of speeches made after midnight in the House

of Commons over a period of twelve years. At late sittings scarcely

a reporter remains, and the necessity of going to the press with some

account of the proceedings obliges the editor to give but a brief summary

in which the speeches are not only divested of flesh and blood, but are

almost boneless. Yet things are said at those times which the public

would read with amazement both for their instruction and their boldness.

Sir John said he did not intend his notes to be published until after his

death. It will be a remarkable volume when it appears.

A London daily paper of age and pretension, often describes

speeches of note which are never found in the report in its columns.

Sometimes it quotes sentences of distinction which nowhere appear in the

speech in its pages. Only one paper gives a full Parliamentary

report. Once five papers did it. On the great debate when the

Taxes on Knowledge was the question before the House, five daily papers

gave full reports. So marvellously accurate were they, that there

was scarcely a variation of a word in them. I heard all the speeches

and compared the reports the next day. Competition in reporting

produced a perfection which exists in London no longer.

CHAPTER LXXXVIII.

AN UNTOLD STORY OF THE FLEET STREET HOUSE.

(1868.)

THIS chapter illustrates the wisdom of the proverb

that zeal without experience is as fire without light.

It was an early ambition of mine to have a publishing house

in Fleet Street. There Richard Carlile had established the right of

heretical opinion to publicity. I was for continuing it there.

The Duke of Wellington headed a society to drive Carlile from the street.

He did not intimidate him, nor was the society able to remove him except

by procuring his further imprisonment. Resentment at this incited me

to succeed him. Fleet Street was one of the highways of the world.

A million curious people pass through it every year, of every travelling

nationality under the sun.

We had won the right to say what we pleased, and the question

arose, 'What did we please to say, and how were we going to say it?' In the

combat for the right to speak, very picturesque invective had been used.

In the use of that weapon our adversaries much excelled us; but, we being

the party of the minority, the blame of employing it fell upon us.

When we had won the field we could hold it only by fairness of speech, the

"outward and visible sign" of just intention and just principles.

William and Robert Chambers had established a secular

publishing house in the High Street of Edinburgh. I proposed to my

brother Austin that we should do the same thing for Freethought, in Fleet

Street, London. The printing business was to be his—the publishing

and its risks mine. The responsibility of capital, trade salaries,

rent, and taxes remained with me. My name alone was on every bond.

Mr. James Watson had been, since the days of Julian Hibbert,

the publisher of Carlile's works, taking like peril. As the new

house in Fleet Street would necessarily affect his business, which was his

only means of subsistence, I asked him what would compensate him for loss

of trade thus caused. He said £350, which, with what he had, would

provide for him in the future. According to the accepted morality of

trade, I was under no obligation to consider his interests. A man

sets up in business next door to one in the same line, doing what he can

to lure away his neighbour's custom, and it is not counted dishonourable.

It seemed baseness to me, and I promised Mr. Watson the money. This

proved an unfortunate thing for me. When he came to know the

indispensable business expenses of the new house were £300 a year, he did

not see how I was to meet them, apart from fulfilling my promise to him,

and, being of an apprehensive nature, he could not conceal his misgivings;

and as he knew the chief country agents upon whom I depended, his fears

transpired in personal communications with them and to my chief friends

whom he knew, they having as much regard for him as for me. The

effect of this was disastrous on a young business. My solicitor, who

had advanced me purchase money of the lease, asked me what I was to have

for the money to be paid to Mr. Watson. He thought me imprudent.

I had nothing to produce, save the right of selling his books, which never

yielded £50. Nevertheless I kept my promise. My brother Austin

was as solicitous as I was to do it. Seeing Mr. Watson on the

opposite side of the street, looking in his wistful way at the house, I

sent my brother with the only £60 in hand to go over and pay him the final

instalment, which he did. The transaction was in every way

unfortunate to me, but I never regretted it. Nor do I now. The

curious thing was that no one respected me for it, or believed it, and no

one ever made any acknowledgment of it, not even Mr. Watson. Mr. W.

J. Linton in his "Life of Watson" omits it, although it made the end of

Watson's days pleasant. It was treated as incredible, and for the

first time I came to understand the sagacious maxim of the Italians,

"Beware of being too good." I had known few persons in danger of

transgressing the rule, and did not suspect I was one.

A valued colleague, Charles Southwell, took a very different

view from Mr. Watson as to the profits obtainable in Fleet Street, and

thought I was making riches there, as many others thought, so what was

loss tome was envy to others. Southwell published pamphlets on my

prosperity. One day I sent for him, showed him the bonds I had

signed, and that I owed all the money he thought had been given me.

His exclamation was a full acquittal—"Jacob, you are a damned fool!" I

asked him to publish it. "No, I won't own I was wrong; but I will no

more say what I have said," was all I could get. The financial part

of the story may end here. The £250 given me after the Cowper Street

debate, £650 given me subsequently, a gift of £250 and all I could earn by

lectures and writing—over the needs of my household—were all lost.

Propagandism is not, as some suppose, a "trade," because

nobody will follow a "trade" at which you may work with the industry of a

slave and die with the reputation of a mendicant. The motives of any

persons to pursue such a profession must be different from those of trade,

deeper than pride, and stronger than interest.

Afterwards there came mischief of another kind, which I had

bespoken without knowing it. As a co-operator I was an advocate for

profit-sharing, and I made this arrangement with those I employed.

As the law then stood, this made them my partners, and gave them an equal

claim with me to the property. One who had some knowledge of law,

and was hostile to me, incited two servants to act on their "rights."

They might have carted the stock away, and could only be prevented by

force, which I had reason to avoid. An assault case would then have

come on at the Mansion House which would have had an effect bad for the

secular cause. The addresses of my friends were copied from my

books, and letters sent to them, which cost me for many years many valued

friendships, for reasons I could not answer—not knowing them. The

manager of the newsagents' department was instructed that he might take

away the business books, and did it. It was two years before I could

recover them by process of law. Then I had to keep outside the court

because, were I called upon to give evidence, I could not take the oath,

and that fact would have set the court against me. The judge said

that had I come into court he would have given the man twelve months'

imprisonment. [24] This affair put me to £200

expense—besides losses through having no proof to adduce of the balances

of newsagents due to me. Had the law which, later, Mr. Wm. Scholefield, M.P. for Birmingham, caused to be passed, been in force then,

I should not have been at the mercy of enemies. Now-a-days, an

employer giving profits to servants does not constitute them partners.

Just then, when my fortunes were least to my mind, Mr. Ross,

at that time an optician of repute, learning that I was being unfairly

used, came down and gave me a cheque for £250. That was a bright,

unparalleled morning which I shall never forget until remembrance of all

things fades.

Despite all difficulties, "147, Fleet Street" was kept in

force from 1853 to 1861. Its objects were—

1. Promoting

the solution of public questions, on secular grounds, apart from theology.

2. Obtaining equal civil rights for all excluded from them by

conscientious opinion not recognised by the State.

3. Maintaining a publishing organisation which should influence

public affairs.

4. Maintaining a centre of personal communication open to publicists

at home and from abroad.

5. Stimulating the free search for truth, without which it is

unattainable—the free utterance of the result, without which search is

useless—the free criticism of it, without which truth must remain

uncertain—the fair action of conviction, without which public improvement

is impossible.

6. Maintaining an organ which should be open to all writers, without

regard to coincidence of opinion, provided there was general relevance and

freedom from odious personalities.

The shop was made bright, and, by removal of partitions, spacious.

All new books of progress were on sale, and advertised in papers of the

house without cost to the authors. A large room was fitted up for

meetings and for the use of visitors. In each panel hung a portrait

of some eminent writer. Visitors from every part of the world

interested in New Thought came and found information respecting all

lecture halls and places they wished to see. We published a

catalogue of all the chief works of advanced thinkers (giving the prices

and the names of the publishers to promote their sales), by whomsoever

issued. No other house ever printed a catalogue like it. The

house was an Institute. There have been other houses in Fleet Street

since with similar objects, but none like it—none having the same

features. The main object was the advancement of new opinion:

business was an appendage to be well attended to; but it stood in the

second place.

When the peace of 1856 was proclaimed—though the great

nations of the Continent were left still enslaved—we illuminated in front

of the house those nobly reproachful words of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,

which said:

|

"It is no peace.

Annihilated Poland, stifled Rome,

Dazed Naples, Hungary fainting 'neath the throng,

And Austria wearing a smooth olive leaf

On her brute forehead, while her troops outpress

The life from Italy." |

These words

were read by a quarter of a million of people. Every newspaper in

London agreed that this was the sole illumination which expressed the

political truth of the hour. These things could never have been done

save in a house standing in one of the highways of the world, where those

must pass whose eyes it was worth while engaging, and where nothing can

well be ignored which was done. On other public occasions

Garibaldian and Italian flags greeted memorable processions.

In 1857 there was the Day of Humiliation proclaimed on

account of the Indian Mutiny. Instead of joining in it, a placard

appeared in our windows which attracted crowds of readers. It was

entitled, "Objections to the Humiliation."

"1. It is an

ineffective proceeding, seeing that temporal deliverance is not to be

obtained by intercession of Heaven.

2. It is offensive, as imputing to the judicial act of God the

blunders of the East India Company.

3. It is impolitic, if we have enemies in India, to give them the

satisfaction of thinking that they have brought Great Britain to confess

'humiliation.'"

Without a publishing house we could not have rendered the

service in the Repeal of the Taxes upon Knowledge mentioned in a previous

chapter. In the affair of the opposition to the Conspiracy Bill, the

committee met in the Fleet Street house, as did the Garibaldi Committee at

the time when the British Legion were sent out to Italy. Then, for

several days, a committee of soldiers sat in the visitors' room, and the

shop was constantly crowded with Garibaldians who volunteered to join the

Legion. My brother was as much occupied as I was. This was

international service, but it was not business.

We published works for Mazzini, Robert Owen, Kossuth, Louis

Blanc, Professor Newman, Dr. Arnold Rouge, January Searle, Major Evans

Bell, William Maccall, W. J. Birch, and many others.

I had a bust of Kossuth made by a Hungarian sculptor, and one

of Mazzini by Bizzi. The original of Mazzini was purchased by Mr.

Ashurst. The mould, which cost me £7, was never returned to me by

the bust maker. It was said it had been broken. A few years

later I saw several busts in a window cast in my mould, which I judge

still exists.

We printed and published also the "Manifesto of the

Republican Party," by Kossuth, Ledru Rollin, and Mazzini. Though

written by Mazzini, he modestly, as was his wont, put his name last.

All the publications I issued bore my imprint as printer as well as

publisher, for the law makes the printer responsible. Were there no

printing of books, there could be no publishing of books. The

publisher may be a nominal person, of residential address unknown; but the

printer is real, and commonly has a plant of type which may be

confiscated, while he himself can readily be found and incarcerated.

The law aims mostly to intimidate the printer. I, therefore, took

the responsibility of the printer as well as publisher.

Julian Hibbert gave Carlile £1,000 with which to furnish his

shop when he opened it, and he had like sums from him on other occasions

for publishing purposes. Notwithstanding the vicissitudes which

befell us, we should have succeeded in a "business point of view" had we

had money sufficient to continue when hostilities were surmounted.

As it was, we did enough to justify the expectation of usefulness which

induced so many to support the undertaking.

When we opened this house the voice of the Socialist was

silent in the land and the watch-fires of the Chartist were extinct.

As far as we were able, we intended to maintain the claim of Socialists

and Chartists and some other causes for which they cared not. We

cared for political freedom at home and abroad, for unless it prevails

abroad it can never be secure at home. There is an aristocracy of

sex quite as offensive as an aristocracy of peers. Manhood suffrage

was popular with the Chartists, but they cared nothing for women's

enfranchisement. In a passage which I quote from a manifesto of

Kossuth, Rollin, and Mazzini, which did but express our ambition:—

"A great movement

must have an arm to raise the flag, a voice to cry aloud—The hour has

come! We are that arm and that voice. . . .

Advanced Guard of the Revolution, we shall disappear amid the ranks on the

day of the awakening of the peoples. . . . We are

not the future; we are its precursors. We are not the democracy; we

are an army bound to clear the way for democracy."

It was my intention to "disappear in the ranks." As soon as I had

extinguished all the liabilities I had incurred, I volunteered to hand

over the place to the promoters. I thought if others had the profit

which might accrue they would continue the work without direction.

This was my mistake. To me it was of no consequence who had the

advantage if the house was maintained. But nobody believed this.

Freethought is of the nature of intellectual Republicanism.

All are equal who think, and the only distinction is in the capacity of

thinking. I never set up as a chief. I never talked of loyalty

to me, but of loyalty to principle alone. In freethought there is no

leadership save the leadership of ideas. I went into this

undertaking with this conviction, and as I went in I came out.

CHAPTER LXXXIX.

LORD CLARENDON'S CONCESSION.

(1869-72.)

THIS chapter describes another instance of work

which, my being of the Secularistic persuasion, I was incited to attempt. In my Christian days I had been taught that the safety of my own soul was

the supreme object I should keep before me; but experience showed me that

the human welfare of others was a more honourable solicitude, and more

profitable to them.

It has been the custom of the Government, since 1858, to instruct her

Majesty's Secretaries of Embassy and Legation to prepare "Reports on the

State of Manufactures and Commerce Abroad." It seemed to me that the same

persons might collect information of not less importance to working men. At times, during several years, I made attempts to get this done.

Through Mr. Milner Gibson, I obtained a copy of the original circular of

instruction for the preparation of the manufacturers' reports on commerce,

as I intended to base on them a plea for reports on labour.

At length, in April, 1869, Lord Clarendon being Foreign Minister, whose

generous sympathy with those who live by industry was known, I concluded

he might, on due representation, make this concession. It was then I

wrote to Mr. Bright, whose attention was always given to proposals which could

be shown to be reasonable, useful, and practical; for that which is

reasonable may not be useful, and that which is useful may not be

practical, while a project which is at once relevant, beneficial, and

possible, is self-commended. Seeing me next midnight at the House of

Commons, he called me to him, saying, "Tell me now what you want." On

hearing it, he answered, "Write me a letter with your reasons in it, and I

will give it to Lord Clarendon." By the courtesy of Mr. William White,

chief doorkeeper of the House, I wrote in his room the letter' the same

night, and posted it in the Lobby before two o'clock. The next day

(April 19, 1869), Mr. H. G. Calcraft (Mr. Bright's secretary, he being then a

Minister) wrote to say, "Mr, Bright would ask Lord Clarendon to take into

consideration my suggestions." On April 21st following, Mr. Calcraft

again wrote, "by Mr. Bright's request, to say that Lord Clarendon thought my

proposal an admirable one, and that he had given instructions that the

information may be obtained from the several Legations." My letter upon

which Lord Clarendon acted set forth that workmen needed information of

the condition of labour markets abroad as much as their employers. Strikes

against reduction of wages take place, which reduction is often owing to

competition abroad, but is not believed, owing to the knowledge upon which

the employer acts being unknown to the men. Authentic information

accessible to trade unionists would be instructive and useful. Emigration

is promoted by Government. Some who go out suffer great disappointment

from want of knowledge of the right places to which to go. This becoming

known, many are deterred from emigrating, and thus miss good opportunities

of advantage through ignorance of where the right labour markets in other

countries lie. In Turkey 6,000 stone-masons were suddenly wanted for one

of the Sultan's new palaces, while masons were emigrating to countries

where stones were not used in buildings. I enumerated certain kinds of

information secretaries of Embassy and Legation could furnish from the

countries in which they were stationed.

Questions to which I asked answers were:—

-

What was the state of the labour market? What openings

were there, if any? And what kind of workmen were wanted?

-

How would English workmen be hired and housed? What kind

of dwellings would they find? What wages would they be offered? What

rent would they have to pay? In what quarters would they have to dwell,

in healthy or unhealthy places? Would they find tenements

available—ventilated, drained, and free from air poisoning?

-

What was the purchasing power of money in other countries? All prices should be reduced to English values. A workman at home

earning £2 a week, on hearing he could earn £6 a week abroad, would

resolve to go out; whereas the cost of food, clothing, and rent might

be thrice as high as in England, and his £6 in a new country might go no

farther than £2 at home.

-

What is the dietary and habits to which an Englishman

must conform in another country, as respects health-preserving power. Should a workman live in some places abroad as he lived in England, he

would be dead in twelve months. Workmen who have overcome every

industrial disadvantage and have raised themselves to competence abroad,

yet rush down the inclined plane of excess, the bottom of which is

social perdition. A report which afterwards came from Egypt said

"Spirits must be avoided. Temperate workmen keep their health well. The

intemperate die." The report from Reunion said, "Rum is rank poison to

the European. None who contract the habit of drinking it can remain in

this country and live." These are torpedo sentences which arrest the

attention of the unthinking transgressor. In the mining districts of

Alabama night air is deadly.

-

School questions need also to be asked. If an

emigrant took out a family, what education could he get for his

children?

-

What is the standard of skill among native artizans with

whom the Englishman would have to compete? Do they put their character

into their work, or are they without artizan pride? Would they make a

stand against doing bad work as they would against bad wages? In what

degree would good quality in work have effect in raising wages? A

workman might deteriorate among new comrades if they were shabby,

bungling, careless workmen.

All these

questions were not contained in my first letter. They were increased by

permission of Lord Clarendon, as mentioned hereafter. The additions

incorporated were three—(a) those relating to health-preserving power

abroad, (b) to means of education of children, (c) to the quality of

artizan skill.

A few days after these suggestions were made (April 26), Sir Arthur (then

Mr.) Otway informed me that "he was to state that Lord Clarendon, who

fully shared my views as to the interest and importance of such

information, had received my suggestions with much pleasure, and that it

was his lordship's intention to instruct her Majesty's Secretaries of

Legation to furnish reports on this subject, which Lord Clarendon proposed

eventually to present to Parliament in a collective form, which he hoped

might meet the objects indicated in my letter." When the first

volume of these "Reports upon the Condition of the Working Classes Abroad"

appeared, they received from the New York Tribune the name of the

"People's Blue Book," given, I believe, by Mr. G. W. Smalley. The volume

was found to be of unexpected interest, and abounding in curious

information. Some Secretaries of Embassy excelled in brightness, variety,

and relevance. As each volume appeared, I wrote a letter in The Times

describing it. On April 13, 1870, and on September 26, 1871, leaders in

The Times were written, illustrating the value of the reports,

concurring also in my representations of their usefulness. Lord Clarendon

was pleased to express the satisfaction with which he read my first letter

to The Times. His death unfortunately occurred soon after.

In Lord Clarendon's instruction to the Secretaries of

Legation, I observed that he had changed my phrase "purchasing power of

money" into "the Purchase power of money." "Purchasing power" was a

phrase new to the Foreign Office, nor was I aware that it had been used in

this financial sense before I employed it. It seemed a fair form of the

participle. The term afterwards came into general use, and is quite common

now.

Occasionally a consul of an inquiring mind, who happened to be in England

when the instructions were first issued, had doubts as to their purport. Lord Clarendon sent him to me, at Cockspur Street, where I then had

chambers, and I had the honour of explaining the nature of the information

sought.

In due course, Mr. Robert Coningsby, a young working engineer, known at

that period as the author of letters on social questions having a Tory

tinge, wrote to The Times, saying, "It was all very well for Mr. Holyoake to connect his, name with these Blue Books. The Society of Arts

is entitled to the credit of bringing the subject before the Government,

and the credit of bringing the subject to the notice of that society

belonged to him." The Society of Arts did not corroborate Mr. Coningsby,

nor did he know how early had been my efforts in this matter. Nor did he

pretend that he conceived or defined the scope of the questions, or method

of obtaining the information required. The Foreign Office frankly accorded

me permission to cite the communication received from them. I

therefore explained in The Times that Lord Clarendon sent me the

minute he had forwarded to the Embassies beginning with the words—"Mr. Holyoake has

made a valuable suggestion as to the steps to be taken to ascertain the

facts as regards the position of the artizan and industrial classes in

foreign States." This minute was also sent to me for my consideration with

the intimation "that Lord Clarendon would be happy to consider any

suggestions I might have to offer, as to any other matters connected with

foreign countries in which the industrial classes in this country take an

interest, on which the Secretaries of her Majesty's Legations might be

instructed to report." This I did, as the reader has seen, in the

enumeration already given of questions to be answered. Sir Arthur Otway,

with the spontaneous courtesy usual with him, wrote to me, saying that

"these reports which were found so useful and interesting were mainly due

to my suggestions, and that the late Lord Clarendon, as also the late Mr. Spring Rice, spoke to him more than once of my services in this matter in

terms which would be very gratifying to me." After these facts

appeared in The Times, Mr. Coningsby made no more claim of being the originator of

these People's Blue Books. Three volumes of reports, of nearly 1,000

pages, were issued. Had the trades unions subscribed £20,000 and sent out

commissioners, they could not in five years have collected and published

the same amount of accurate, verified, and trustworthy information

contained in these volumes thus supplied without cost to them by the

Foreign Office. It was believed that these reports would be furnished at

intervals of five or ten years. Twenty have elapsed since the last was

issued. Changes in artizans' condition, interests, and aims have occurred

since then, and new reports would now have new uses and new influence. Before the People's Blue Books appeared, the information necessary for

industrial advancement abroad depended mainly on chance and charity, and

as Madame de Staël said of M. de Calonne, whether he meant mischief or

service, "he did not do it with ability"—for want of knowledge.

Men learn patience if not contentment by a comparison of their condition

with that of others, which may be no better or worse than their own. They

may be encouraged by examples of success attained under discouraging

circumstances. A workman can appreciate industrial causes in operation

apart from himself, which he fails to discern or estimate through

familiarity and prejudice, while he is in contact with his own condition.

Principles true in our own streets are discerned more vividly when their

operations are traced in the destiny of strange and distant communities. Artizans gain expansion of knowledge, like that which travel gives, when

they are brought into the presence of international facts, and are

inclined to respect a Government which, instead of lecturing them or

coercing them, gathers the experience of nations into a page, and bids

them read it for themselves.

CHAPTER XC.

ASSASSINATION BY A JOURNALIST.

(1870.)

ABOUT the time of the sixth volume of the Reasoner

(that is not an accepted calender of events, though it enables me to fix

the date of many) two young Irishmen came to London seeking their fortune

in literature, and to them I was able to be of some service. Both made

acknowledgments of it in after years, which I did not often experience in

other instances. One of them, Mr. Gerald Supple, came from Dublin; for him

I had regard because, out of his slender earnings, he always sent a

portion for the support of his mother and two sisters. He had seen

patriotic service in 1848, having been concerned in an insurrection

planned in Meath. He wrote for me in the Reasoner on secular subjects. Afterwards he wrote in the Empire and Morning Star, to which

I introduced him. At length he went to Australia, studied law, and became

a barrister. As is the case with the best Irishmen, his sympathies were

with liberty and freedom everywhere, and he never forgot the claims of his

country. He had many friends at the bar, and no one who knew him could

fail to be impressed by the generous qualities in his character. In 1848,

he had been a contributor to the Nation, then at its best, and several

national ballads written by him are to be found in Hayes's collection, to

which good judges assigned great merit. Mr. Ebenezer Syme said in the

Argus that Mr. Supple "always wrote with extreme moderation and good

taste, never permitting his private predilections or animosities to

influence his public writings. On several subjects outside the newspaper

sphere, he had a fulness of knowledge, and wrote upon them with a judgment

that was admirable. He wrote on Irish genealogies and antiquities in

a manner no other Australian journalist could approach."

In 1870 news came that he was under sentence of death in Melbourne. Newspaper controversialists, as is common in new colonies, are addicted to

primitive forms of invective. Melbourne resembled then the amenities

of journalism which prevailed in Canada, a much older settlement, until

Mr. Goldwin Smith infused refinement in it; and my friend in Melbourne

believed that no reformation in certain quarters there was possible except

by the pistol. He therefore resolved to shoot an imputative adversary, one

George Paton Smith, at sight—and did it, the shot taking effect in his

arm. Mr. John Walshe, a retired police officer, hearing shooting about,

with the instinct of his profession, rushed forward to defend the man

assailed. Mr. Supple, being near-sighted, mistook the ex-officer for his

enemy, shot and killed him. It was his near-sightedness which caused him

to entertain unfounded resentment against many persons whom he thought

showed him public disrespect by passing him without notice, who had no

unfriendly intentions towards him; he was simply unable to observe their

recognition. His brother barristers considered that he had suffered in his

professional career by loss of briefs through his infirmity of sight, and

he had become moody and unhinged in mind. They therefore set up a plea of

insanity to save him. This Mr. Supple repudiated in court, stating

that he knew perfectly well what he was doing, and that he intended to

kill Mr. Smith, but did not intend to kill Mr. Walshe.

Many persons who commit brutal outrages, or even commit murder in a brutal

manner, when it comes to their turn to suffer, squeal and whine to be

saved from that which they have inflicted upon others. It was not so

with Mr. Supple. In his speech to the Court, before sentence was pronounced, he

declared "his purpose was to teach certain persons in Melbourne a lesson

in manners. He well knew the consequences of what he had undertaken, and

did not object to be hanged." Mr. Supple continued:—"Some years ago

I quarrelled with G. P. Smith because of his scurrilous abuse of the

people of my country, written by his pen and published in the newspaper he

edited. I was the only Irishman on that paper, and I resented it.

He who will not stand up for his country is a paltry person. From

that time Mr. Smith slandered me. In this colony there is no check

on slander. An action for libel does not arrest it. The duel

does not exist here. If any man sent a challenge he would be handed

over to the police, and his challenge treated as a farce, as a piece of

swagger or bravado. In England public opinion acts as a check on

slander. There is nothing of the sort here. I have done this

colony good service in reviving something of old-fashioned honour, in the

middle of this coarse and wholly material civilization—this mean and

sordid thing, in which little seems to be valued higher than the dinner or

the bank account. The time will come, and my act will hasten it,

when the community will cease to tolerate the assassin of character.

As for me, I hope to give my life very cheerfully in this cause.

Hanging cannot disgrace me. The gallows cannot disgrace me—I shall

confer honour upon it. I shall be glad to get away from this colony,

and I can leave it no other way than by the gate of death."

This manly speech could not but inspire respect for the prisoner, however

much one must feel that society would be impossible if everybody should

resent slander in the deadly way he had adopted. Mr. Supple was sentenced

to death. But his counsel appealed against it, on the ground that it was

not justifiable to hang a man for an act he never intended to commit. A

plea good in morals, but not in law. Mr. E. J. Williams, who was in

the Gallery of the House of Commons, and who knew of my early friendship

for Mr. Supple, having intimation of the appeal, asked me to aid in saving him

from execution. To this end I made the following affidavit, which Sir Wilfrid Lawson did me the favour of attesting for me:—

"I, George Jacob Holyoake, of 20, Cockspur Street, London,

County of Middlesex, do truly and solemnly make declaration that I knew

well Mr. Gerald H. Supple, now imprisoned, as I am informed, in Melbourne,

Australia, on charge of murder. When he was in England he was employed by

me in journalistic work: I assisted in procuring him engagements. I had

and still have great respect for him as an honourable man; but I observed

a moodiness in his manner, varying from impulsive generosity of speech to

inexplicable reticence. His shortness of sight was greatly against him. He

seemed a despairing man at times, and I used to consider him a person whom

some great calamity would one day overtake. From the difficulty his manner

put in the way of his friends serving, or indeed being sure when they were

serving him, I feared great suffering would befall him. Though very

intimate with me, and as I believed having personal regard for me, he went

away without saying such was his intention, and never communicated with me

at the time, nor mentioned me in writing to friends of mine who had

served him at my instigation. I doubt not he had acquired some distrust of

me, utterly without reason. No doubt he was liable to dangerous delusions.

"GEORGE JACOB HOLYOAKE.

"Signed in the presence of WILFRID

LAWSON, Justice of the Peace

for the County of Cumberland."

Having rendered political service to Lord Enfield in his Middlesex

candidature, I asked him if he could do me the favour of enclosing my

affidavit in the Foreign Office bag, he being then in that department. The

transmission would then be surer and probably swifter. Lord Kimberley, who

became aware of my request, directed (Aug. 4, 1870) me to be informed

(which I was by Mr. J. Rogers) that my "affidavit would be forwarded by

the next mail to the Governor of Victoria." But Lord Kimberley did much

more than this, as I afterwards learned. Seeing that a man's life was at

stake, his lordship, from motives of humanity and kindness, directed that

the substance of my affidavit be telegraphed to the Governor of Ceylon

with instructions to transmit it to Lord Canterbury at Victoria. By

good fortune, which ought always to attend on so generous an act, the

telegram was received in Melbourne on the very day before the appeal, and,

being delivered by the Foreign Office messenger, it was a welcome surprise

to Mr. Supple's counsel, and gave the Court the impression that the

Government at home were desirous that the prisoner should have the

advantage of whatever evidence existed on his behalf. The result was

that, instead of the sentence of death being confirmed, Mr. Supple was granted a

new trial on the ground of his mental condition.

Four months later a letter arrived from Lord Canterbury upon the subject.

Lord Kimberley, still remembering my interest in the fate of my friend,

desired Mr. H. T. Holland to transmit to me a copy of the following

despatch from the Governor of Victoria:—

"LORD CANTERBURY TO THE EARL OF KIMBERLEY.

"GOVERNMENT OFFICES, MELBOURNE,

Sept. 7, 1870.

"MY LORD,—I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your lordship's

telegram forwarded to me through the Governor of Ceylon, relative to the

mental state of health of G. H. Supple (now under sentence of death), and

stating that a despatch and affidavit would be forwarded by the next

mail." I lost no time in forwarding this telegram to the Law Officers of

the Crown. I may mention that a point of law was reserved at Supple's

trial which comes on for argument before the full court to-morrow.—I have

the honour to be, &c.,

"CANTERBURY."

It is clear from this despatch that but for Lord Kimberley's calculating

promptitude my affidavit had been all too late.

The next communication I received was dated Melbourne

Gaol, October 4, 1870, from the prisoner, saying:—

"MY DEAR MR.

HOLYOAKE,—How can I thank you for your friendship and

kindness in stepping in so promptly to my help! That telegram must have

been an expensive one—I understand from £15 to £18. My friends only

ascertained from the Government the day before the last English mail left

that it is you who thus came forward for me.

"I have been thirteen years in this country now. Ebenezer Syme was my very

good friend, thanks to the favourable things you said of me in your letter

of introduction to him.

"I calculated upon getting into trouble for what I did, but I cheerfully

accept the consequence as a smaller evil than endurance. The medical

commission found I was no lunatic. I was to be hanged last month, when,

two days before the morning fixed, leading members of the bar picked flaws

in the legal proceedings, the public was stirred with interest, and the

Government granted a reprieve and an appeal to the Privy Council. I was

notified of a new trial—the same case under another aspect. My legal

friends insisted on the plea of insanity. I would have no more of it, and

defended myself. The jury were half for acquittal and half for conviction. I may not be hanged for some time yet.

"I often think of those days in London in '50 and '51, and again in '56,

when you and Mrs. Holyoake made me feel as if I were at home.—Ever yours

sincerely and gratefully,

"GERALD H. SUPPLE."

In the end he was sentenced to imprisonment during her Majesty's pleasure. A year later (Aug.

11, 1871), he wrote again from his gaol, saying:—

"I am unable to express what I feel, and how grateful I am, for what you

have done for me, so kindly and ably in such various ways, at a time 'when

a friend is twice a friend.' Your articles in the press, your telegram,

and Lord Kimberley's kind interference, thanks to you, have each and all

had a great effect in my favour on public opinion here. Your article in

the Reasoner, which I saw (as well as that in the Birmingham Post, which

you enclosed to me), was put into one of the papers here, the Herald, and

has done me much service. The public in Australia are much influenced in

all social matters by opinion at home, and your word goes a long way here

as well as in England, even among people who may differ from you in

politics and theology. After the appearance of that article I had an

unusual number of visiting strangers, including three or four members of

the Legislature, cordially promising me their good offices at

opportunity."

How difficult Mr. Supple was to serve was shown by Sir Charles Gavan

Duffy. When he was in office at Melbourne, Supple, at that time a law

student and journalist, asked him for permanent Government employment. Several months afterwards, he offered him a post with a salary of £400,

which had been previously held by another journalist, one of Supple's

friends. Supple had a short time previously been called to the bar. He

indignantly resented the offer, which made Sir Gavan think his mind was

affected. He was a singular being, but his courage, disinterestedness, and

noble scruples, were honourable singularities. He had done that for which,

as a lawyer, he knew he deserved hanging, and felt bound in honour as a

gentleman not to shrink from nor evade the penalty. Eight years'