|

The Town of Derby.

CHAPTER I.

NOT all local readers have the past of the town in

their minds, familiar as they may be with the daily aspects amid which

they live. But readers elsewhere, into whose hands this narrative

may come, will be curious to know what kind of place Derby is, in which so

remarkable a store, as that of which we write, has sprung up in the last

half of the nineteenth century. Some account of the town is

therefore inseparable from a history of the store.

Fifty years ago no one looked for special enterprise among

the working class of Derby—nor as for that no expectation ran high with

regard to any class in it. Derby was believed to be a quiet,

respectable town of some antiquity, not much in the minds of men outside

the Midlands. It was probably the most stationary town in England.

It had little initiation, nor any wish for it.

True, the silk trade and china manufacture had their

birthplace in it, which implied the existence of skill among the

industrious classes—but progress was torpid as a python, half its time.

Hutton, its notable native historian, relates that so late as 1738 an

inhabitant of the town made a safe wager that "he could not find a single

house erected on a new foundation within 100 years." The stranger

lost the wager. Stationariness in industrial enterprise, and in

mind, go together.

Lying on the highway between London and the North, Derby,

like the Alma, was always "to wandering travellers known" if not to the

general public. The invader knew it. The Romans knew it—they

knew every place which had a strategical position. Their policy was

to make a road by a town and never through it—so the "Roman

Road" ran by Derby, like the Derwent. The town was a Royal Borough

in the days of Edward the Confessor, who did nothing but confess, and died

in 1066. Money was coined in Derby during several reigns. This

shows mechanical skill, civic influence, and importance—but not the

character of onwardness.

Insularity and preference for isolation of mind were

characteristics of Derby, it cared nothing for outside thought as is seen

in the charter, which the inhabitants obtained, by their own

solicitations, from Richard I. which gave them the power of expelling

every Jew who resided in the town, or ever after should approach it.

Centuries later, in the reign of Queen Anne and George I. not a Roman

Catholic, an Independent, a Baptist, an Israelite, nor even a harmless

Quaker could be found in Derby.

It is well there was no Midland Railway in those days or this

charter had given Mr. George H. Turner, the general manager, trouble.

There must have been a Theological Committee sitting permanently, to see

that no Muggletonian or Christadelphian crept into the town. The

Railway is a force on the side of toleration. It carries Jew or

Catholic without scruple or compunction. It will even elect a Quaker

as chairman, if he has good business capacity.

Let us hope that the people of Derby, in the days of their

charter of exclusion, had good light within their town since they set

their faces against having any light from without.

No wonder narrowness of ideas prevailed. It was seen in

the narrowness of the streets. Iron Gate, Sadler Gate, and other

thoroughfares were emblematic of the confined outlook of the inhabitants.

The channel streets were never used by carriages. Indeed there was

no room for carriages or for ideas to turn round in them. Wider

thoroughfares—intentionally made so—are signs of larger information and

a wider outlook.

The only recorded instance of independent thought in those

days, was that of an humble Derby girl who was born blind yet could see,

like others, into the nature of things. She doubted the Real

Presence. What could it matter what the helpless thing thought of

that? and the town burned her alive. The poor brave girl was only 22

years old. There is no town or city, within a hundred miles of

Derby, which has the distinction of possessing one of the humbler class of

like heroism of understanding. It is not often that a town has a

philosopher in it, whose convictions are thus torment proof.

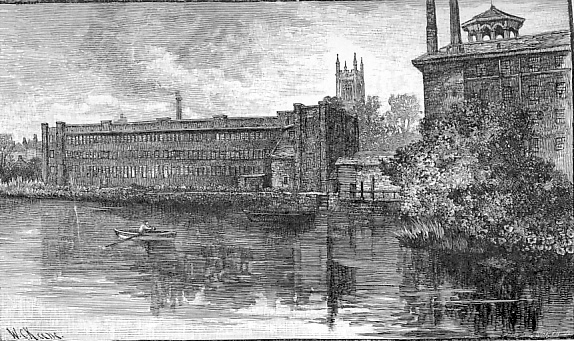

THE OLD

SILK MILL;

FIRST SILK

MILL IN ENGLAND.

Another instance of the vitality of thought among the working

class of Derby, was William Hutton the unrivalled historian of the town,

who still remains among Derby authors unsurpassed for veracity, sagacity,

and capacity. Hutton was a native of the town, who served two

apprenticeships at the old silk mill, of seven years each, like Jacob,

without being like him rewarded with Rachel. All Hutton obtained was

great hardship and poor wages. He wandered to Birmingham, became a

paper dealer, and wrote a history of that town which is still held in

respect. He wrote a book on the Court of Requests of which he was a

member. The Chambers Brothers reprinted it, as a remarkable example

of natural logic applied to the solution of the disputatious cases of

daily life. Hutton's "History of Derby" exhibits his honourable

pride in the town of his nativity. The wisdom of his opinions were a

century in advance of the time in which he wrote. No wonder a town

producing such an instance of vigorous reason and historic genius as

Hutton displayed, should eventually furnish impassable co-operators.

The somnolent white cactus is said to bloom but once in a 100

years. [1] But dilatory Derby, a burgh through

which Saxon Kings marched, took 1,000 years to bloom in. The Derby

cactus did not expand its leaves until the advent of the year 1800.

In 1790 the population was less than 9,000. In 1834 it had reached

24,000, and in 1871 it amounted to 49,000. Soon after the boundaries

were expanded, and the Midland Time Tables publish the population this

year (1900) at 100,000, an increase of 90,000 in the century.

Mr. Scotton in the Congress Guide Book (1884) says that

Defoe's description of Derby as "a town of gentry rather than of trade"

was true in Defoe's time. Derby is now a town of commerce rather

than gentry, who happily continue though their proportion has changed.

Derby [2] in its sleepy way has had a

distinguished past if regard be had to its royal visitors and illustrious

families, as that of the Earls of Derby who sprung from this town.

But the repute of Derby is now commercial. It has taken its place in

the front rank of civilisation. Its future is that of opulence and

industry, and one of the signs is—the rise and progress of Co-operative

Stores, which have become an historic feature of the place.

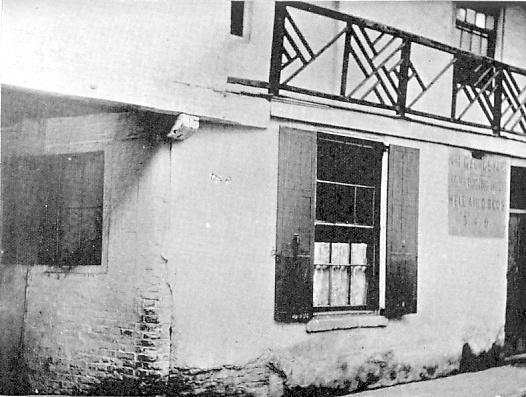

DERBY,

FROM EXETER

BRIDGE.

The Co-operative Store.

CHAPTER II.

NO Co-operative Society in England has had a more

romantic and unpromising origin than that of Derby, whose history these

pages record.

The Derby Co-operative Society is the third society of the

Rochdale type which has celebrated its jubilee in the nineteenth century,

thus furnishing another irrefutable answer to all who treated co-operation

as a dream, as a utopian aspiration, as an hysterical craze to which those

who labour are especially subject. In this case the hysteria has been on

the part of the convulsive prophets, who were incapable of foreseeing the

capacity which lay latent in the industrious classes. It was said that

with their diversity of view, prejudices, jealousies, and other unfitnesses, they could never be got to act together, and if they should

do so it would not be for long, as they would never hold together. It was

predicted that if a sensible object was put before them they would not

understand it, and if they did they would not like it. By what strange,

slow, and precarious steps the great success of this society has been

reached few of the general public know, and many members who have joined

in later years may be surprised to learn. The enterprise of self-help and

mutual help—for both go together in co-operation—which commenced in all

sorts of doubtfulness, has continued with decision for fifty years.

Continuity is distinction which only time confers. It means English

persistence, which is the source of success in peace as in war. In this

case of the store it is meritorious, because it has been evinced under

difficulties of a very

deterrent kind. It commenced in Derby in 1850, and has been growing day

and night ever since.

Half a century ago there were numerous prophets in England who professed

to foretell every new thing notable. Yet no Zadkiel foretold the

Co-operative Store in Derby, in

Rochdale, or Leeds. Yet they were all as remarkable as new comets. "Old

Moore," whom everybody thought all-telling, never mentioned them in his

almanac. These stores have made the fortunes of thousands and thousands of

penniless people; yet no wandering fortune teller ever thought to turn an

honest shilling by reading the signs of them in the palms of

toiling hands, where the fortunes all lay. The astrologer knew nothing of

what was to happen in the industrial heavens. The zodiac contained no sign

of it, and the stars were all silent. The rise of co-operation quite

escaped the notice of the stellar prophets.

The three great changes in the fortunes of the working people are (1) from

slave to serf; (2) from serf to hireling; (3) from hireling to

partner—all most momentous in the history of the vast race who labour. It

is co-operation alone that promises to convert the hireling into a

self-acting man, and establish permanent betterment by superseding hirelingism by the dignity of partnership. With or without "signs and

portents" heralding this new order of life—it is appearing.

Co-operation means acting with others in enterprises of trade or labour,

in which the profits arising in the store or workshop, shall be equitably

divided among those who create them by skill of hand, or skill of brain.

A Co-operative Society is a voluntary association and it acts by reason,

not by force. Its members depend upon themselves, not upon the State. Its

aim is the advantage of

each, consistent with the good of others. This care for the good of others

is the essential thing which distinguishes co-operation from common trade

and commerce. This principle carries a million moralities in its train. It

puts public progress on a new path. It means co-operating to live, instead

of

competing to destroy. Care for others implies tolerance—for if

co-operation does not include it, association may die of dislike.

Not all at once are all the consequences of the co-operative term

understood. Co-operation inspires fraternity. If fraternity is not a virtue, it becomes a necessity. It is not only a

grace, but an obligation. There must be goodwill—for persons

with ill-will in their hearts will not act with one another. The

profit of co-operation depends upon numbers. Few can gain

but little, many can gain much. Thus the conditions of profit teach

conciliation, and conciliation is impossible without justice to others,

which is the highest attribute of the moral nature.

It has been mentioned that the Derby Store is of the "Rochdale type." Many

readers of the outside public, will not know what this means.

The chief feature of "Rochdale Co-operation" is that the profits of the

store are paid to the purchaser. Five per cent

is allotted to paid-up shares. Reserve funds are set aside for the

security of the society, which ends in all property and buildings being

owned by the members. There is also an Education and Recreation Fund,

whose object is to secure

intelligent and pleasant membership. All goods are paid for on purchase

which saves clerkage, prevents loss by bad debts, and teaches working

people a dislike of indebtedness—which the middle class have not acquired

very largely.

Besides, Stores on Rochdale lines are pledged not only to honesty in

measure, but to purity in all commodities—important to the poor, to whom

family sickness is serious. "Disease" says the Indian proverb, "enters

by the mouth."

The profit made by purchases varies from 1s. to 2s 6d. in the pound, and

is determined by the number of members, which may be few or many. Profit

in excess of trade union wages, is given in the workshops as well as in

the store, as is done in the great Woolwich store. These profits, allowed

to accumulate, constitute a Profit Bank, from which members draw money out

who never put anything in, seeing that they pay no more for their

provisions than the market price, and can depend upon them being genuine,

and free from adulteration. By charging the market price for what is sold,

these stores do not undersell shopkeepers—thus maintaining amity, which

is the very principle of co-operation. For this reason many persons, not

needing the advantage of the store for themselves, become purchasers with

a view to encourage their poorer neighbours in efforts of self-help, in

knowledge of business, and habits of thrift.

The other kind of co-operation is known as "Civil Service" or "London

Co-operation." There is no membership here, no distribution of profits,

not even among purchasers—save in

cheapness—in these associations. The profits go to the shareholders, as

the business is joint stock, tempered by reduced prices. The co-operative

feature is limited to this. The advantage to purchasers is that they have

their goods a little cheaper, the cheapness being dissipated in a little

larger expenditure, without encouraging frugality. By thus underselling

other dealers, this form of co-operation creates irritation among

tradesmen which Rochdale Co-operation does not. Besides, these Supply

Associations, though the best of them aim at genuineness, are not able to

secure it, having no Wholesale Buying Agency pledged to purity and equity,

advantages which Rochdale Co-operation provides; nor is there the moral

satisfaction that the producers of the goods purchased have an equitable

share in the profits of their industry, free from the hateful conditions

of sweating, except so far as Supply Associations make (as the best of

them do) purchases from Co-operative Productive Associations, in which all

workpeople participate in the profits of their own labour. But inasmuch as

Supply Associations adopt the rule of ready money payments, they improve

the character of their well-to-do customers. The book-debt habit is so

common that large London shops have to go into convenient liquidation, as

the Receiver in Bankruptcy can collect the debts which the firm could not

obtain from their wealthy customers, through the County Court, without

risk of offending and losing them.

Such are the differences between working class co-operation on the

Rochdale plan, and the Supply Association of the middle class kind. What

other advantages come to working people,

and to the town, through Co-operative Stores will further appear as this

history progresses.

THE FIRST

STORE, GEORGE

YARD.

The Beginning in George Yard.

CHAPTER III.

THE now imposing Albert Street Store with its 37 branches, was

begun by a few capitalless carpenters and joiners in an inconvenient

out-of-the way (from the point of view

of business) unpromising hayloft in Sadler Gate, 1849-50. Too low in

fortune for ambition to reach them, necessity led the early store makers

to rent a hayloft only accessible by a rude flight of steps. On the

left-hand side of the George Yard entrance may still be seen, bricked up

now, the old doorway

which led to the primitive store. Underneath it was a stable. On turning

the corner into George Yard there is now a public

lodging-house, with a balcony in the upper part. That is where the store

was.

The George Yard is part of what is known as the "Wide Yard," a long

thoroughfare, having the appearance of a little forgotten street with

tenements of various aspects and pretension, but being a thoroughfare it

was so far favourable for outside custom, had it been sought. The entrance

to the George Yard, in which the store doorway stood, is a low-covered

passage, short, dark, vacuous, and originally uninteresting save to

visitors to the "George," or other contiguous taps—never wanting

thereabout.

In the old days there was a real George Hotel which gave its name to the

yard. It had an Assembly Room with a frontage of 100 feet in Sadler Gate. In the eighteenth century, balls were held in these rooms which were

attended by

"Royalty," as the newspapers say. There is still extant a picture of the

famous Scotch Pretender and his army passing through the Iron Gate, the

George Hotel being the chief feature in it, the sign of the George hanging

out in the street. The door on the right of the George Yard entrance, once

led to the taproom of the Inn then known as the Black Boy [3] and the balcony

round the corner, now part of a lodging house, was put up so that the

elite might watch the dog fights and other sports of

the day in comfort. Fifty years ago the spectator in the balcony would

look down upon the less exciting, but more wholesome spectacle, of honest

carpenters carrying home purchases from their humble store.

|

|

|

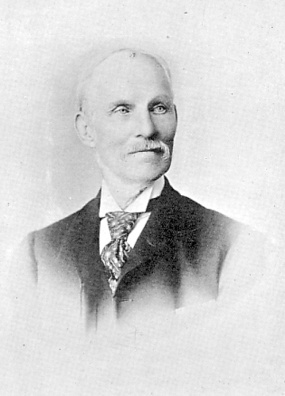

T. R. BROWN. |

The only living member of the George Yard Store, is Thomas Rushton Brown,

of Acton, and the earliest particulars of its formation are derived from

his intelligent testimony. After many years' absence he visited Derby

again last Christmas, when he and Mr. Scotton verified the

premises—occupied at the commencement. In the year 1849 Mr. Brown and

other members of the Union of Carpenters and Joiners, mostly in the employ

of Mr. Mansfield Cooper, whose workshops were then in St. Mary's Gate,

heard of the success of the Rochdale Pioneers. [4] The news was brought by

a wandering tramp to the Carpenters and Joiners' House of Call, which was

then at the Bull's Head, Queen Street. It came into the heads of some of

these workers in wood, to start a store among themselves on similar

Rochdale lines. Derby was as clever as Rochdale. Surely carpenters could

do what weavers had done. They conferred with Samuel Smith, a joiner, at

the Midland Railway Carriage Works, who ever encouraged them in their

purpose.

Jonathan Henderson, the secretary of the Carpenters and Joiners' Society

(who afterwards became secretary of the new coterie of Derby Co-operators)

wrote to Rochdale for information. It would be William Cooper—the

greatest propagandist

a store ever had—who would send it to him. "Several of the Derby

Joiners" says Mr. Brown, "gave their names and subscribed small amounts." The first committee of ways and means was held in his house 56, Abbey

Street. After the manner of Rochdale, they elected a committee and these

were their names:—

|

THOMAS RUSHTON BROWN. |

GEORGE ALLAN. |

|

JAMES

COOPER. |

ROBERT RILEY. |

|

THOMAS

WHITTLE. |

WILLIAM CORNER. |

|

SAMUEL LEAM. |

JOHN ASLIN. |

|

JAMES

WALKER. |

WILLIAM JOHNSON. |

|

JONATHAN

HENDERSON, President and Secretary. |

|

SAMUEL SMITH, Treasurer. |

These were the Twelve Apostles of Co-operation in Derby. Rochdale had 28

Pioneers, Derby 12. Rochdale began with £28, Derby with £2.

In the George Yard, Sadler Gate, they began their career. They bought

second-hand scales and weights, and purchased some flour from Shaw, the

miller, in St. Michael's Lane, and a parcel of groceries from Bakewell, a

grocer at Market Head. They bought as far as their small means would go. Mr. Brown being the son of a grocer, became their first buyer and shopman. They asked no credit and did not go into debt for stock, which is the

honourable co-operative policy.

Their first act of business in the upstair store was very creditable to

them. It was to weigh out a stone of flour, a quarter of a pound of tea,

and two pounds of sugar, and make

a gift of them to Mrs. Loam, the wife of a sick member. After a time they

opened their little night store from 8 to 10 o'clock three times a week.

It was not until the fourth year (1854) that the George Yard Store began

to keep any record of their limited transactions, which no doubt were

vividly inscribed on their memory. The minute book, when they had one,

bore no name or designation, nor did it state any place where the meetings

were held—it was not often that the year was given. The proceedings were

simply headed "Committee Night" afterwards "Committee Meeting." Accepting

members seems to have been the principal business of the committee.

The committee of management recorded December 4th, 1854, are the following:—

|

JOHN LEAKE. |

EDWARD LITTLEWOOD. |

|

THOMAS BUXTON. |

WILLIAM KANE. |

|

HENRY GLOVER. |

THOMAS

R. BROWN. |

|

HENRY ROBINSON. |

The first resolution recorded in 1854, is "That all the

members shall serve in the store in their turn, and that anyone failing,

and not finding a substitute, shall be fined 1s." It was certainly

hard to have to work for nothing and to be fined 1s. for failure in doing

it.

At the same time, 1854, it was resolved "That William

Griffith make a box to preserve the bacon belonging to the Society—the

box to be 5 feet long, 2 feet wide, and 20 inches deep." It would

require a much larger box to-day, to hold the bacon of the society.

On June 13th, it was ordered "That the sixpenny sugar on sale, be sold at

4½d. per lb. through it being an inferior

article, and that the fines of members be stopped out of their dividends."

This Draconian society took care that the fines were collected. On

June 24th they proposed "to give 2d. a lb. for newspapers provided they

were clean."

The first order of importance was sent "to Woodin and Jones

for 28 lbs. of best coffee, 1 cask of raw sugar, 56 lbs. of Patna rice,

and other commodities." At that time Mr. Lloyd Jones was in

partnership with Woodin. There are other transactions with the same

firm recorded. The first mentioned stock-taking was ordered on

August 19th. A non-attendance fine of appointed waiters, who acted

as shopmen, serving at the counter, was reduced from 1s. to 6d.

On September 5th, James Benson was appointed auditor in the

room of J. Henderson. Samuel Smith was appointed treasurer for the

next nine months. On October 28th the waiters appointed for three

months were Brown and five others.

On December 16th (still 1854) it was resolved "That Mrs.

Birkett be allowed £2 as a loan, and pay the same to the funds by not less

than 4s. 4d. a quarter, and more if she thinks well." This is

another act of friendliness to a woman member, probably a widow. The

minutes are entered in a crude way, and the one just cited is open to the

construction that "she might have more money if she thinks well," but the

meaning probably is that she might repay more than the "4s. 4d. a quarter"

if she be able. At this meeting it was proposed and seconded

(January 6th, 1855) "That Mr. J. Whittle buy a pig," of which nothing more

is said. It probably came to a quieter end than one purchased

subsequently.

A motion was made (December 16th, 1854) "to consider the

propriety of removing the Stores of the Co-operative Society." On

January 18th, 1855, a motion was made "That we take two rooms, that is,

two rooms belonging to Mr. Biggs, in Victoria Street." Samuel Smith

and John Cregg, who appeared to have an affection for the upstair store,

proposed "That we remain in the place in George Yard." It was,

however, unanimously carried "That we take Mr. Biggs' rooms, and that

Samuel Smith (who did not want to go there) be appointed with Littlewood,

Leake, and Corner to wait on Mr. Biggs as early as possible in the present

week." Eight months elapsed since a deputation was appointed to see

Mr. Biggs, but what they said to Mr. Biggs, or what Mr. Biggs said to them

is not recorded. But the unrest was revived at this time, and on the

motion of Wm. Corner and J. Henderson (September 3rd, 1856), it was agreed

"to summon a Special General Meeting to consider the propriety of breaking

up the Society." This was held on September 12th, 1856, when H.

Pemberton and S. Smith moved in Parliamentary terms "That the proposal to

break up the Society be adjourned to this day six months." That was

lost, but another motion was carried, "That the Society be broken up in

three months." At another special meeting, on the motion of H.

Pemberton and J. Henderson, it was carried "That this Society be dissolved

on the first Monday in December." At length the date of its

dissolution was fixed, but the party of continuity had not exhausted their

resources. They arranged that S. Smith and E. Sillwood wait on all

members who had given notice to withdraw their shares, to learn whether

they will allow them to remain if the society goes on. Evidently the

society consisted of determined co-operators, for it took more trouble to

break up the society than it did to start it.

December 4th, the day of doom, came, and the society was not

dissolved as ordered, for on December 11th the "Dead Stock" was

directed to be valued, and on December 19th it was proposed and seconded "That we carry on the trade of the Co-operative Store." Thus the gallant

little society continued its career. But the advocates of retreat were

still active.

It was a resolution of courage and faith, for the prospects were not good. In the September quarter, 1853, the sales had amounted to £173, the

dividend and interest was £5. 0s. 10d. In the second quarter of 1855, the

receipts had gone up to £200, but the receipts were now falling to £10 a

week, which was reached in 1857.

Remembering the futility of all previous methods then known, of putting

the society to death, a more vigorous process was now proposed. Since

resolutions to break up the society and to dissolve it—the day of

dissolution being duly fixed—had all failed, it was proposed (December

15th, 1857) by J. Henderson, seconded by William Corner, "That we smash

the concern up." Clearly, it was the only course, since all other means of

extinguishing the society had proved ineffectual. This desperate motion

would have ended the society if anything would. But there was a majority

of four against putting the

society to a violent death. Then the friends of continuation

took the field. J. Colbourne moved "That we get another place"

(Withdrawn). Strange to record it was moved by J. Henderson "That we keep

this place." Many had attachment to the store in the loft, and the motion

was carried. Lastly, it was proposed by H. Glover and seconded by S.

Smith, "That we try another quarter and see what progress we can make,"

which was carried by a majority of five. The battle of December 15th,

1857, ended by Littlewood and Corner being appointed to see Mr. Biggs, and

try to get the premises for less rent, which suggests that it was a

question of rent which caused the previous negotiation to fail.

The George Yard Society had got the ready money idea in their minds and

kept pretty well to it. In October, 1857, they restricted credit to the

amount any member had in the funds.

It is to be inferred, though not formally recorded, that the society came

to terms with Mr. Biggs and removed to Victoria Street. The society had

had an honest career in George Yard. It had no debts—being prudent it had

no losses except such as came from depreciation of their small stock by

time or misadventure, or by sugar proving to be of inferior quality than

they had bargained for—a very creditable record for working men during

seven years' administration of an unfamiliar business in which they had

everything to learn.

Transference to Victoria Street.

CHAPTER IV.

THE store in Victoria Street was in another yard—but it was without a

thoroughfare. On the right hand there stood, in 1858, a small plain

looking chapel, on which now stands a handsome Congregational edifice. Next the chapel was a private house, and between the two was a

narrow passage, which still remains. Next to the private house was a toy

shop occupied by a Mr. Biggs, and the yard was

called "Biggs' Yard," as he had a warehouse in it. It was that warehouse

that was occupied by the George Yard co-operators.

It is now occupied by a zinc worker and tinman. Indeed, at the present

time, there is quite a nest of workshops about the

yard. The private house is now a grocer's shop. The grocer, a very civil

person, who in answer to my question as to whether he had knowledge of any

co-operators being about there 40 years ago, said "O yes, the

co-operators began up the yard at the back of this shop," which identified

the Victoria Store. Mr. Hilliard was the first, as we rode by it, to point

out to the writer the narrow passage which led to it. Of course, as the

reader now knows, the co-operators did not begin there. But tradition is

seldom accurate. Their seven years in the George Yard, was unknown to the

courteous grocer.

Here, again, in the Biggs' Yard Store, Mr. Brown long waited on customers

behind the counter, without salary or fee of any kind—the business not

being sufficient to pay for assistance.

After October 14th, 1858, no minutes are recorded until January 13th,

1859.

In the year 1857 mention was made of applying for a

license, but it is not said for what purpose. This was probably because

the idea of opening the society to the public was in

the air. But a more immediate need was in the mind of H. Glover, who moved

"That we have the skylight repaired." Both as a carpenter and amateur

grocer, water coming in upon the sugar would seem to him intolerable.

An August committee meeting report commences with the words: "Mr. Benson

in the chair," the first time any chairman has been mentioned. Messrs. Colbourne and Sedgwick proposed

"That we take premises of the Working

Men's Association, and take possession of premises for £12 per annum for

one year certain, at a quarter's notice on either side." The committee of

the Working Men's Association, who appeared to hold the premises, were

willing to make any alterations that might be suggested. The warehouse

store in Biggs' Yard does not prove an ideal place, since already the

minds of members are turned towards a new one. The society was now bent

upon emigrating elsewhere, and they proceeded to appoint Samuel Smith and

Mr. Colbourne to wait upon the Working Men's Association Committee, to

effect an agreement. But whether the committee ever returned, or what

success they had, was never reported, and no more reference is made to the

subject. The unrest ended in the society going to Full Street, but no

minute records the time when the step was taken.

No minutes are ever signed, and the recording scribe appears to be often

changed, from the different handwritings, and on this date, for the first

time, it was agreed that the secretary's salary, whose name is not given,

be increased 5s. a quarter, by which time it may be inferred they were in

Full Street, where the business increased and the secretary had more

duties to perform.

If the reader be not distracted by the date, it may be mentioned here that

on June 6th, 1859, Colbourne and Slater were appointed to wait on Mr.

Thompson. Whether he was the agent of Mr. Biggs does not appear. Presumably he was. The object of the visit probably related to the

society's tenancy of the Victoria Street Store.

Nothing of mark is recorded this year, though a new departure of great

moment did occur. There was no mention of a resolution to admit the public

to membership, but the

effect of it, when it took place, was soon seen in the minutes being

mostly occupied in the admission of new members.

Towards the end of 1859 many proposals for the admission of new members

are registered in the minutes, some of them being women who have never

been named as members of the Carpenters and Joiners' Union. Among them

Eliza Winfield was proposed by Mrs. Eaton, and seconded by William

Winfield, and a candidate is spoken of "as a member of the Co-operative

Association," which implies a larger conception of the society than

heretofore.

By the best construction of the minutes now possible, it may be assumed

that the resolution to throw open the society to the public was arrived at

in Victoria Street.

The event of the admission of strangers to membership, meant the

effacement of the society which for nine years had carried the flag of

co-operation. It requires good sense, good insight, and generous heroism,

for a society to efface itself for the good of miscellaneous persons

unknown. No wonder the question became one of conflict. The proposals to

seek new premises and open the society to the general public, was regarded

with disquietude. There was the conservative repugnance, which we know in

politics, to transfer to others the advantages they had sought for

themselves. There was the natural apprehension that outsiders would

destroy the society. Some had fear of the business expanding beyond any

power of management they possessed. They had no experience, and no belief

in the chance of members furnishing persons abler than themselves. They

were unaware that every man, as Lord Chesterfield said, brings into the

world with him powers which are of the nature of Bills of Credit, upon

which he never draws. It is opportunity which brings unsuspected ability

into play, then these Bills of Credit become negotiable. The proposals to

open the society to the public, nearly produced a revolt. The wiser

members prevailed, and broke the barriers down which kept them from

prosperity.

Up to this time the constitution of the society only admitted joiners to

join. This had not arisen from narrowness or exclusiveness. The carpenters

and joiners had formed a Co-operative Club, with a view to benefit by

mutual dealing; just as the great Civil Service Co-operative Society in

London did.

That was begun by a few clerks at the General Post-office, who having

heard of co-operation in Rochdale, began by buying chests of tea and some

other family articles, and selling them

among themselves. Only post-office men were permitted to join. Afterwards

they opened a Civil Service Store in the Haymarket, and admitted the

public as members. When the carpenters and joiners found that the bulk of

their own order did not join them, who were uninformed or indifferent,

whom they had no means to instruct, or failed to inspire—and the wiser

members among them were too few to achieve success themselves, they wisely

resolved to see whether others would take up the co-operative idea, and

walk in the path they had marked out, and profit by the experience they

had gained for them. Thus they became the pioneers of the greater society

which succeeded them—which encountered difficulties that appeared

insurmountable and amid discouragement which would intimidate ordinary

men—and planted at last the co-operative standard on the heights where

all the Midlands could see it.

Singular Career in Full Street.

CHAPTER V.

IN the year 1859 the Co-operative Association of Carpenters and Joiners,

which had now become a public body, removed to premises in the rear of 47,

Full Street, opposite the Assembly Rooms.

For the third time the store was located up a yard, at the head of a blind

alley in a disused stable. The hayloft was the new shop and a small lower

place too rude to be called a compartment, served as a committee room, low

and so confined that when a member had to leave others had to go outside

to let him pass, as the little table in the centre occupied all the vacant

space.

A narrow, steep, ungainly flight of steps led to these "desirable

premises" as the auctioneers say. No stranger

could hope to find the place without a guide. Yet here they burrowed for

several years. Though a new room was built and a lower stable converted

into a shop, the inconvenience was merely mitigated. The premises may be

seen now pretty much as they were then, when I and Mr. Scotton went over

them 40 years later.

The place still has kinship with its old joiner occupants, for it is now a

carpenter's shop, used by Mr. George W. Wood, [5] who showed us a row of

old biscuit tins left by the co-operators, bearing the old labels, and for

which other uses are now found. Nothing deterred the joiners, who knew how

to put things together in their manger store. They fitted up the place

sufficiently for the business they had in hand. Hopeless as the prospect

looked, it is admitted that the removal to Full Street was the turning

point in the fortunes of the store, accelerated by the admission of

outside members.

The rabbit warren looking place in Full Street, into which the pioneers

had now crept, was not unknown to industrious and thrifty Derby citizens. The place had a name. It was

known as Penny Bank Yard. On the right hand side was a library, which the

store members had the advantage of using. This privilege was given them by

the trustee of the property, the Rev. J. Erskine Clarke, the Vicar of St.

Michael's Church, and the President of what was known as the Happy Home

Union, which shows the Vicar to have been a man of kindly

and genial sympathies. He is now known as Canon Erskine Clarke, Vicar of

Battersea, Rural Dean and Canon as Winchester, and holder of other

important offices, and of editor of The Chatterbox, and an author of

distinction. He was a well-wisher to the humble society which had settled

at the head of Penny Bank Yard, and is remembered with respect and honour

on that account.

The reader has seen in the last chapter a Working Men's Association

flitting through the pages like a shadow. All the while they were real and

had some occupancy or control over the premises. For in March, 1863, the

Rev. Erskine Clarke and Mr. Herbert Holmes, representing the Working Men's

Association, agreed to pull down some buildings, adjoining the old stable

where the store was, and build a room on the ground

floor for a grocery department. The rent charged for the new room being

£26 a year and the society had to pay two years

rent in advance, and take a lease for seven years. It was then that the

drapery and boot department was started, and meat was sold in another

room.

In June, 1860, the society consisted, like the French Academy, of 40

members. But before long a great change

took place. It was soon noised abroad among working people, who had ears

to hear, that there was a place up Full Street Yard where persons could

draw money out of a bank, who had never put any in, and what the members

received bore the unfamiliar name of "dividends on purchases." Before long

new members came dropping in. Henderson, Littlewood, Brown, Glover, Swift,

Corner, S. Smith, and other George

Yard pioneers, were proposing new members at one or other committee

meetings, Scotton, Hilliard, Riley, and other more recent names frequently

appear as proposers or seconders of new members. Pages and pages of the

minutes of the committee are filled with the names of new members who were

proposed and seconded, elected, and had paid their admission shilling. As

many as 36 were admitted on a single night in 1860. The ceaseless proposers were the vigilant scouts of the Full Street army, who

reconnoitred the enemy and brought scattered or wandering adherents, who

did not know where the new camp was. Railway men, who are alert by nature,

came about the place and put life into it.

Business began to improve, and the Full Street ramshackle rooms were

converted into a Night Store, opened every evening from 7 to 9-30, and on

Saturdays from 2 to 10 p.m. The society soon found they must open their

premises daily, and employ a shopman. Their secretary was Robert Riley. Mr. Scotton was appointed assistant secretary, who was also to take part

in the duties at Full Street while it was open at nights. Next "a safe is

to be bought, not being safe for the shop to be left to itself," which

needs explanation. The meaning was that the store premises at the top of

the yard, might easily be broken into and things of value be carried away,

and a safe to lock up books or articles most in need was required. A safe

might baffle casual and miscellaneous thieves. The store was too small to

tempt professional burglars.

This year (1860) mention is made for the first time of a "Quarterly

Meeting." Shortly after, a portion of the profits was set apart for a

Reserve Fund for incidental expenses. This, appears to be the beginning of

the Reserve Fund, which has falsified so many predictions of the dismal

prophets, who said that co-operative societies would soon fail. None of

them foresaw that working men would have the prudence to provide against

loss.

Hitherto the names of members, their proposers and seconders, and the

payment of their admission fee were recorded, and that was all the

committee knew about them. Now their increasing numbers made it necessary

to have a separate record of their residences, and the secretary was

empowered in September (1860) to get a book in which to keep the names and

addresses of the members. It was ordered "That we have 4,000 hand-bills

printed to distribute through the town,

that the words Co-operative Store be painted on the door." Probably the

first time the words were painted on the lintel of any Derby entrance. This implies that strangers were coming to their gates, and it was

desirable that the Co-operative Gate should be made plain to the curious

and to the inquirer. Increase of business had for some time imposed new

work on the office holders, and it was agreed that the secretary was to

receive 15s. extra for extra labour during the last year. His salary was

to be 4d. a head, the treasurer's 2d. a head, and the waiters 1d. per

head. Moreover the secretary was to have

a bag in which to carry his books. Subsequently, when Mr. George Smith had

become secretary (Sept., 1861), the salaries were revised. He was to have

£5 a quarter; A. Scotton, assistant secretary, £2. 10s. a quarter; S.

Smith, treasurer, £3

a quarter. This was very moderate payment for the strenuous labour, often

late into the night, which they rendered. This shows good sense on the

part of a working men's society—workmen being usually jealous of any one

having higher wages than themselves, not always remembering that the

skill, thought, and voluntary industry of others, often when they were

asleep, brought prosperity to the society and increased their own

dividends.

There was no Women's Guild in those days, but the names of women appear as

proposing members, whom they had doubtless induced to come to the store.

Contribution books were ordered to the number of 300. Thomas Brown was to

give 12s. 6d. per hundred for them, which shows that new

members were coming in. No mean devotion is now shown in the interest of

the store by purchasers, some of whom on Saturdays would trudge two or

three miles to their homes with their week's provisions on their backs,

strapped to their shoulder.

In 1861, it is ordered "that a printed report be made at the end of the

quarter in future." The society had got the length of having quarterly

reports—henceforth to be printed. The

society is in business bloom now. Other signs of business maturity present

themselves. The treasurer is requested to provide security of £100, four

persons being bondsmen to the amount of £25 each. Money, hitherto so

scarce, is at last coming to hand. Orders were given that two forms were

to be fastened to the floor, and the members enter at one end in their

turn and leave at the other, all of which implied increase of custom and

distribution of dividends.

Though the committee were doubtless jubilant in their hearts, they did not

neglect practical things: "Mr. Sherwin was directed to call and look at

the pig in Brook St." of which they had heard, "and purchase it if

suitable." A thousand copies of the rules which had come into existence,

though their advent had never been mentioned, were to be printed, which

looks as though a crowd of candidates were expected in Penny Bank Yard. In

due course two coffee mills were ordered to be purchased, as well as

scales suitable for general grocery business, upon which they were now

fully embarked.

In February, 1861, for the first time a public tea meeting is to be held,

the price being 9d. for adults, and 6d, for children under 12 years. When

a really good tea is given, enabling strangers present to judge of the

quality of the provisions of the store, there is no surer form, or more

agreeable form of propagandism than this. If there be loss upon the

entertainment, it is money well expended. A meeting was to be convened in

the Temperance Hall, which shows that they were calling the attention of

the town to the store. The Temperance Hall if disengaged is to be taken

for monthly meetings, which implies great increase in members.

The committee advertise in the Gazette, and another Derby paper, for a

female waiter in the hosiery and boot department. By beginning shoemaking

so early it would seem that the Derby co-operators are contagion proof,

which shows the workers should have a salubrious time. It is always

remembered that when the Great Plague visited Derby, it never entered the

premises of a tobacconist, a tanner, nor a shoemaker. A drapery was

commenced. By agreement, the owners pulled down some outbuildings, and

made a Grocery shop on the ground floor. Then the hayloft shop became the

Drapery and Boot and Shoe department. Miss Brown had care of the Drapery

department, to which access was still up the old stairs. The Drapery

department grew as is the way with store draperies. Two buyers were

despatched to Manchester to purchase new stock. At length the more

ambitious members of the committee began to tire of back yards, and longed

for a frontage in the street. Full Street was considered the Central

Store, until the new store in Albert Street was built, which became the

Central and the registered office of the society, and has continued so to

the present day.

The society, however, soon recurs to the project, latent but never still,

of making tracks into the open. "Mr. Durbus is to be informed that we

agree to take the premises in Traffin Street." There is no further mention

of the Trafiin Street premises, but they seem concerned also for the

extension of their own accommodation where they are, for "Mr. Clarke is

to be written to with a view to obtain the remaining part of the room on

the ground floor as soon as possible, and if he will, lengthen the

top-room floor." The committee then recur to their own affairs in Full

Street, and resolve to take the room downstairs at an increased rent of

£1. The work at Full Street is to be completed in a fortnight, which shows

that the society not only continue in the occupation of that dreadful

place, but contemplate additions. A refreshing thing seems to have

befallen the dust-choked joiners, it being ordered in August, "That the

joiners working at the Store have one gallon of ale given to them."

The general secretary appointed is to give his whole time to the duties,

and have a salary of 33s. a week. Mr. George Smith became permanent

secretary. A room was rented on the opposite side of the passage, which

became the secretary's office and committee-room.

A proposal was made to establish a Wholesale Store at Full Street. The

commissariat needs were growing.

The society early set itself against clandestine commissions, and ordered

that "no persons connected with the society should solicit any gift from

those from whom we purchase."

The society shows financial vigilance, and five coin detectors are to be

bought. The property at Full Street is to be insured at £350, and the

stock at £180, the drapery at £500, and grocery at £400.

The long deferred day of consideration touching the convenience of

officers came at last. There is no end of dignity to be conferred on Full

Street. A No. 4 safe, Cotterell's make, is to be bought for £8. A clock is

to be bought for the Full Street committee-room, and an extra

half-dozen chairs, including an arm chair. They are now to deliberate in

comfort, and, no doubt, in a new committee room, as no extra chairs could

be got into the old one. At this time the Full Street premises had long

been open all day, as an established emporium of provisions and other

household commodities.

At length some of the directors came to the conclusion—not at all hastily, that they ought to move into more accessible premises. Three persons were appointed "to look out for a suitable place for a new

branch store. The mind of the society was now fairly set upon extension,

but proceeded with caution, wisely limiting their ambition to the measure

of their

means. It was ordered "that the place in Brook Street be taken as soon as

possible, and calculations be made as to the cost of opening new stores,"

and further "that someone attend the sale of the Labour Hall and £450 be

the extent of the bidding providing the report of those appointed to

examine

property is satisfactory. If otherwise, £400 or £420 is to be the

highest sum offered. At the same time Colbourne, Reynolds, and Crossley

are to be a deputation to Mr. Cox "to see on what terms we can have the

Labour Hall and commence repairs." It was further agreed to advertise in

three Derby

papers for a contract to repair the Labour Hall. No mention is made

whether the Hall is bought or not; but the committee go on attending to

the business in hand. The treasurer was to place the money for the Labour

Hall purchase, in Smith's Bank. The society ultimately bought the premises

in Park

Street known as the Labour Hall. The names John Swift and A. Scotton,

appear on the committee at the time of the purchase of the Labour Hall,

who were always to the front in

enterprises. Mr. Brown is to have the key of the Labour Hall and attend

should they (presumably the recent occupiers) want

to get the boiler away. "The society will find its own wood for repairs

and pay for labour."

|

|

|

J. SWIFT,

late Secretary. |

It was ordered that the committee should see the landlord, with a view to

put in a ventilator, and if he would not do it, they were to do it

themselves. The society was of Æsop's

opinion, that they who want reluctant business done had better provide to

do it themselves. The long experience of the committee in the room they so

long occupied, which resembles the infamous Calcutta prison, in which so

many were stifled to death—may well have turned their attention to

ventilation. Vitiated air made worse by the flickering and smoking candles

which lighted them, oft till midnight, must have produced not only

physical enervation, but obfuscation of mind unless they were men of iron

intellect as well as of iron

constitution. In 1860, when their deliberations first began there, the

co-operative seed they had sown was indeed growing,

but it made a very scant appearance above the ground. Many

were the anxious nights spent by the committee in those times. Mr. Scotton

relates that "often have I heard during our deliberations, the midnight

chimes ring out from the tower of the neighbouring church of All Saints,

before we returned to our homes." Had this midnight committee in these

mysterious quarters sat in London, they would have been all arrested as a

new band of Cato Street conspirators. Nevertheless they continued for

years their nocturnal debates, in the confined and airless cabin they

called their committee room.

Sometimes an anxious wife would consult a policeman late at night, as to

whether he had seen a stray husband about, as hers was absent. When at

last he came home, he was found to have been at the co-operative

committee. It was something to the credit of Derby husbands, if none were

ever found to arrive at home late save those who were members of the

co-operative committee.

[Next Page]

NOTES.

1. The writer witnessed one bloom at midnight in its

100th year in Lord Monson's Vinery, as predicted in the records of the

House. The family came down to see it.

2. Earl Derby is called Earl Darby. The

pronunciation of a name is ruled by custom. I asked Mr. George H.

Turner, the general manager of the Midland Railway, whose experience makes

him an authority, if the town of Derby was by custom called "Darby?"

He said "Yes." The name of a family is its own usage.

Majoribanks is Marchbanks. Cholmondley is pronounced Chumley.

As the Frenchman said, "It is easy to learn English if you write it as it

is not spoken and speak it as it is not written.

3. For the facts pertaining to the earlier history of

the George Hotel, I am indebted to Mr. G. W. Wood. builder and engineer,

Sadler Gate.

4. They were only five years old then but they had

already become, it seems, an inspiration to others. They had

increased their members from 28 to 380; their capital from £23 to £1,193,

and their year's sales from £710 to £6,611; their profits from £32 to

£561.

5. Mr. G. W. Wood, mentioned in a previous note, is the owner of the old

premises. It is congenial to know that he has sympathy with innovatory

thinkers, as he has a son bearing the name of Emerson Darwin. |