|

AMONG THE AMERICANS.

___________

CHAPTER I.

SEA WAYS AND SEA SOCIETY.

IN England we have sea-side books. My friend,

the late George Henry Lewes, who wrote upon most things better than many

men of mark write upon any one, wrote a charming sea-side book. But

I never remember to have seen a sea-book. A man who has made many

voyages in different vessels to the chief countries of the world, might

supply a very useful and popular book, teaching the voyager what to expect

and what to avoid. All I knew was that mathematically the least

motion occurred in midship. That even sickness must have its

conditions—that temperance in eating and drinking was likely to answer

upon sea as well as upon land; and that resting horizontally after meals

had its advantages, and that lemon and biscuit (if hunger occurred in the

early morning) were useful. Sickness did not occur to me, although

we had head-winds outward and homeward each voyage, which delayed us

nearly two days each way. I spent an idle week in Liverpool before

setting out, and another in New York before returning, as being perfectly

rested before a voyage sickness itself would be less fatiguing. I

could write a little manual about ship experience as far as I acquired it;

but it would be absurd and misleading to many without further knowledge of

different kinds of ships, varying seas, and vicissitude of storm, climate,

and shipwreck—the last I have not tried. Only one rule may be

mentioned here, which I observed in America as well as on the sea.

Being in new climates and in new cities, of whose sanitary condition I

knew nothing, I trusted to temperance in eating, to temperance in fatigue

and in exposure, for security in health, and found it. I have

observed that excitement, worry, or fatigue, whether of pain or pleasure,

alike pave the way to illness.

I selected the Cunard line because I knew less of the habits

of other vessels. This line has lost two ships, but during forty

years it is reputed not to have lost a passenger. This furnishes a

sense of security which is very profitable to the line, and diminishes the

sickness among many voyagers. Travellers, however, have assured me

that more space and comfort are to be found in the ships of some other

lines. The Cunards travel in a prescribed path, and have the merit

of not caring to outrace other vessels, and will even take a day or two

longer rather than incur risk. They act upon the principle that it

is better for passengers to be late than be lost. Good imagination

is a powerful quality at sea. Many passengers become sick by

suffering their eyes to rest upon the waves, as the sea appears to mount

and fall around them. I was surprised to find that the officers and

sailors of the Cunard ships, to whose skill and watchfulness passengers

owe much of their security, do not receive higher wages than men in other

vessels. On the second Sunday of a voyage a collection is made for

the widows and orphans of seamen. These ought to be provided for

otherwise, after the manner of the Bill lately passed in Parliament for

the compensation of workmen who suffer injury or loss of life in their

employment, and the subscription made on board should be given to the

common sailors there and then, to whose good seamanship it is mainly owing

that you are alive to subscribe at all.

Sailing, as a rule, is attended with no more risk to life

than railway travelling, and since the facilities for sailing increase

every year, the time is not far distant when everybody will sail

somewhere. A good book, therefore, upon the "Art of being a Sea

Passenger" would be as useful as one on the Art of Swimming. Out at

sea some persons prefer a rolling motion to the heaving; some can sleep

over the screw (which I could do myself, although it seemed to be grinding

under my pillow). A ship has such a variety of motion and sound that

the passenger can take a choice. The stoutest disciple of Dr. Darwin

is generally content with the fertility of evolution on the ocean.

So many people have got to go to sea that the nature of the going ought to

be explained. In the steerage, where the heaving is greatest—that

part of the ship often rises out of the water and, of course, goes down

again—sickness is prevalent; yet children recover from sickness much

sooner than their parents, probably because they know less about it and do

not make themselves miserable by gratuitous imagination. While their

parents are pale and apprehensive, I saw the children delighted at being

rolled about the deck and nobody doing it. The drollery of that

diverted them greatly. In the saloon, when passengers first see the

storm fences on the table, they lose their appetite for the repast; the

children think it very droll, and eat with a new sense of pleasure.

A voyage is indeed a source of recreation and diversion of

mind beyond what any who have never made a voyage imagine. Ideas are

often absolutely suspended. "Dirty" weather comes and discolors

them; "nasty" weather perturbs them; "fresh" weather gives them quite a

new turn; a rain "squall" comes and softens them; a "gale" disperses them;

a "storm" dashes them against each other, bending them or breaking them; a

"cyclone" gives a rotary motion to the most fixed ideas; a "hurricane"

seems to blow them all finally away, and it is some time before the most

diligent shepherd of his thoughts gets them into the old fold again.

The machinery of the mind is unlimbered, and only the best fitting parts

are ever got into position again.

It is thus that the ocean is entertaining and recreative.

The fresh wind blows through your mind. Cries of sailors, straining

of cordage and planks, creaking of the stubborn masts, beatings of the

"steely sea," the roar of the revengeful blast, the clanking of the iron

slaves within—I regarded as companions of the voyage. All the while

the brave engines are driving you through the turbulent and disappointed

waves. Three hundred and fifty miles in every day and night,

The pulses of their iron hearts

Go beating through the storm. |

The passage between England and Ireland, I was told, would

prove unpleasant, but that when we got into the Atlantic, the sailing

would improve. When we reached Queenstown, the more experienced

passengers observed that we should know how to appreciate the serenity of

the Irish passage, when we had a taste of the "roll of the Atlantic,"

which was very encouraging. Every day brought some promise of

novelty. Until I was on the Atlantic, I had never seen the sea

alive. I had heard of "seas as smooth as glass." What I saw

was a sea as smooth as mountains. The Atlantic is a genuine American

ocean; it is never still.

The white crests of the waves appeared to me like white birds

coming over the distant waters. It was quite a new experience to see

dark clouds a great distance before us, where rain and squall were raging,

and know that we had to sail through them; and when in a squall which

appeared at first as though it would last always, we could soon see the

sun and blue sky a long way off, and it was pleasant to discover that we

should ride into the bright sea under them. If a storm did not

extend over an area of sixty miles, we were through it in four hours,

unless head winds blew. The screw of the vessel was then half out of

the water. Albeit the head winds generally did blow with us.

In consequence of what was said in the "Pall Mall Gazette"

concerning the treatment of poor steerage passengers of the Cunard Line, I

went over the steerage quarters, both in the "Bothnia" and the "Gallia."

It was admitted by the writer of the complaints in the "Pall Mall " that

the passengers in the Cunard fared better, as to quarters and diet, than

in other vessels. I went round the ship with Dr. Johnson, the

medical officer of the "Bothnia." The occupants of the steerage

include many rough unmanageable people, whose habits often justify some

coercion for the sake of the comfort of others. But I ascertained

from those who knew, that the general comfort for the steerage passengers

is not what it ought to be, or what it might be. Either Parliament

or the press should compel improvements in the arrangement of the

steerage. When reporters visit a new vessel to report upon its

equipment, they should look into the steerage arrangements. If our

naval architects who seek distinction in rendering vessels shot-proof,

would give attention to rendering them discomfort-proof for the emigrants

who crowd the steerage, it would be a great blessing. Mr. Vere

Foster and Mrs. Chisholm secured many attentions to poor passengers; but

the attention wanted is a different construction of the ship. In

parts of the ship where comfort abounds there is eccentricity of

contrivances. For instance, the name-plates on Cunard doors were so

low that it was only by going down upon your knees that a passenger could

read them. Only a passenger who had broken his leg could find out

the doctor's door. Recurring to the steerage, Dr. Johnson said he

commonly found poor women who came on board with families, and with one

suckling at the breast, were generally in such a state of weakness as to

be quite unable to bear the strain of rough weather; and I saw myself

orders given for dozens of porter and gallons of milk, whereby the poorer

women and children were strengthened. This was additional to the

supply ordered by law, and were given at discretion by the kind-hearted

doctor, who said the company never interfered with him in these things,

and that in many cases, in the ships of this line, emigrants lived better

than they had been accustomed to at home, which may be true of other lines

also. If American ships took as many steerage passengers to Great

Britain as Great Britain takes to America, there would soon be new devices

in the arrangement of ships.

|

|

S.S. Bothnia.

In service, 1874 - 1912. |

As a rule the solitude of the sea is less than a stranger would think. A

large ship is a moving community, and generally affords great variety of

good society. It was only at night, when most persons had gone below, and

the deck was silent, that—leaning among the cordage and listening to the

beating of the dark sea against the sides of the resolute and defiant

vessel as it drove through the baffled waves—you could realize the

loneliness of the ocean. It was like thinking in another world, as I

contemplated the dark desert of water, afar from any land—the busy world,

familiar to me for sixty years, far behind—all before strangeness and

untried existence.

At other times I gave some thought as to what I should do in case it fell

to me to speak in public in America. Like the Scotch, many Americans pride

themselves on speaking English better than the English do themselves,

although they have some peculiarities of their own which sometimes attract

our attention. Clearness of expression and precision of idea I knew were

qualities of American speech: whether I could fulfil these conditions were

disturbing considerations with me. However, a small American book which I

bought to read on the voyage out was reassuring to me. It

was published by a popular house, and was one of a popular series.

The book opened with this passage:—

"The people of the United States have now fairly entered

upon the discussion of economic problems of the gravest

importance—problems upon the right settlement of which both the immediate

material and moral welfare of the community will greatly depend. These

questions are—First, the Money Question: what is good money and what is

bad? Second, the Legal Tender Question: what shall be the standard or unit

of value by which contracts shall be enforced? Third, the Tariff Question:

in what manner and for what purposes shall the revenue derived from taxes

upon foreign imports be collected? Fourth, the National Excise System: how

shall internal taxes be assessed, and what shall be the subjects of

national taxation? Fifth, the Bank Question: how shall those persons who

desire to gain profit to themselves, by rendering the exchange of products

and of services among the people most rapid and least costly, be permitted

to organize the work? Finally, and beside all these great national fiscal

problems, come all the vexed questions respecting State, city, and town

taxation and expenditure, and the yet greater problem of national or State

interference or non-interference in the pursuits of the citizens, either

for shortening the hours of work, promoting education, or attempting to

compass the material and moral welfare of special classes by means of

legislation. What is called civil service reform, or the question whether

corruption or purity shall rule in civil service, waits largely on the

determination of these questions before it can he fully accomplished,

because it is a well-established fact that an attempt to impose a tax

beyond certain limits will promote dishonesty in the revenue service

somewhere, under whatever party name appointments may have been made. To

these we might add the Railway Question; or, how shall the owners of large

or small portions of capital be permitted to combine, for the joint

service of themselves and of the community, in the work now developed into

such gigantic proportions, of transporting passengers and goods over the

continent?"

If America had all these things to settle, I thought it might be glad to

hear of something simpler by way of prelude. If this complex series of

propositions could be put forward without bewildering the popular reader,

nothing I could say would be likely to confuse them. I remember the saying

of General Ludlow "It is not enough to mean well, you must know well what

you mean." If the popular reader believed that the writer above indicated

knew all the answers to his multitudinous questions, any stranger might

hope for liberal attention. As I was never likely to wander into the

social infinites in this way, I took heart and thought I could tell, if

called upon, a simple story of industrial devices, which would be

tolerated. The work which I have alluded to was not without passages of

merit and ideas of value, but it remained evident that a people who would

make their way through its stupendous series of topics would bear with me. I might annoy them or disappoint them. I could never lead them headlong

into a wilderness so vast as this.

My cabin companion passenger was the Rev. James J. Good, of Philadelphia,

a young preacher, who had been travelling in Europe, visiting the Holy

Land among other places. Not knowing that even numbers in a ship

represented the lower berth in the cabin, an upper one fell to me. Mr.

Good, seeing I was the elder, very civilly volunteered to take the upper

berth himself, leaving the lower to me, as being more convenient. He was

quiet, well-informed, and studious, and his pleasant courtesies were

constant during the voyage. One morning a gentleman nearer my age, of very

animated expression, came down to my cabin, and

asked permission to introduce himself. It was the Rev. Dr. Prime. He was a

preacher of great repute in New York, the most evangelical of the

Evangelicals. I never quite knew how evangelical he was; but I was told it

was very much beyond what I could expect to understand; but this did not

prevent him being a very bright-mannered and intelligent gentleman, with

whom I had several conversations which interested me very much. He

introduced me to another minister, who had a wonderful theory of uniting

monarchy with American democracy. But as I had no innate faculty for

appreciating either thing, I made no progress in that way of thinking. This minister was evidently a man of strong thought, and had some original

views. There were twelve clergymen on board, which was pleasant to me to

think of, for if there was anything wrong in me, I doubted not that they

would use friendly intercession in the quarter where they had

influence—and get it all put right.

There is an offensive rule on board ships that the service on Sunday shall

be that of the Church of England, and that the preacher selected shall be

of that persuasion. Several of the twelve ministers of religion among the

passengers of the "Bothnia" were distinguished preachers, whereas the

clergyman selected to preach to us was not at all distinguished, and made

a sermon which I, as an Englishman, was rather ashamed to hear delivered

before an audience composed almost entirely of intelligent Americans. The

preacher told a woeful story of loss of trade and distress in England,

which gave the audience the idea that John Bull was "up a tree." If the

old gentleman who personifies us

had been very high up I would not have published it in a sermon. The

preacher said, after the manner of his class, that this was owing to our

sins—that is the sins of English men. The devotion of the American

hearers was varied

with a smile at this announcement. It was their surpassing ingenuity and

rivalry in trade which had affected our exports for a time. Our chief

"sins" were uninventiveness and commercial incapacity, and the greater wit

and ingenuity of the audience were the actual punishment the preacher was

pleading and praying against. He was preaching this before the punishers,

and praying them to be contrite on account of their own success. The

minister described bad trade as a punishment from God, as though God had

made the rascally merchants who took out shoddy calico and ruined the

markets. It has been political oppression, and not God, that has driven

the best French and German artists into America, where they have enriched

its manufactures with their skill and industry, and enabled that country

to compete with us.

The preacher's text was as wide of any mark as his sermon. It asked the

question, "How can we sing in a strange land?" When we arrived there

there were hardly a dozen of us in the vessel who would be in a strange

land; the great majority were going home. They were mostly commercial

reapers of an English harvest who were returning home rejoicing, bearing

their golden sheaves with them. Neither the sea nor the land was strange

to them. Many of them were as familiar with the Atlantic as with the

prairie. I sat at table by a Toronto dealer who had crossed the ocean

twenty-nine times. The congregation at sea

formed a very poor opinion of the discernment of the Established Church. There were wise and bold things which other preachers on board could have

said, and a good sermon would have been a great pleasure mid-ocean.

On the return voyage in the "Gallia" we had another "burning," but not "a

shining light" of the Church of England, to discourse to us. He had the

merit of reading what he had to say with confidence and evident sincerity. He was a young man, and it required some assurance to look into the eyes

of intelligent Christians around him, who had three times his years,

experience, and knowledge, and lecture them upon matters of which he was

himself absolutely ignorant.

This clergyman dwelt on and enforced the old doctrine—severity of

parental discipline of the young, and on the wisdom of compelling children

to unquestioning obedience; and argued that submission to a higher will

was good for men during life. At least two-thirds of the congregation were

Americans, who regard parental severity as cruelty to the young, and

utterly uninstructive; and unquestioning obedience they held to be

calamitous and demoralizing education. They expect reasonable obedience,

and seek to obtain it by reason. Submission to a "higher will," as

applied to man, is mere submission to authority, against which the whole

polity of American life is a magnificent protest. The only higher will

they recognize in worldly affairs is the will of the people, intelligently

formed, impartially gathered, and constitutionally recorded—facts of

which the speaker had not the remotest idea. Everyone felt that the

preacher himself had been trained in "unquestioning obedience," since he

was evidently without the power of inquiring into or acquiring the

commonest international facts of his time.

I observed that the steerage passengers were not invited into the saloon

to hear the service. Probably the souls of the poorer passengers did not

need saving, and the service was only necessary for the sinners of the

saloon. In this the ship authorities were probably right.

CHAPTER II.

COURTESIES OF NEW YORK.

A STRANGER in America is very much like the Tangier

oysters, which but partly fill the large shell in which they are incased.

Before being sold, they are sent to reside for a short time in another

water, when they are found to have grown double their former size, and

entirely fill the copious shells in which they were born. A brief

residence in America in like manner enlarges the ideas of an insular

Briton. At the Gloucester Co-operative Congress the Heckmondwike

Manufacturing Company exhibited two handsome rugs. One was presented

to Professor Stewart, and the other I had the honor to receive. I

took it with me to America, thinking to astonish New York with the beauty

of co-operative manufacture. I had it hanging on my arm as I entered

the city alone. I soon found that the rug had fascination for other

eyes as well as my own, for when I next thought of it it was gone, in what

way I had no idea. So the discernment or envy of New York prevented

me from displaying my choice example of co-operative industry. If

any "smart" foreign trader brings rugs of that pattern into the English

market, Mr. Crabtree will understand how the design got abroad.

My friend, Dr. Hollick, gave me the use of his rooms in the

Broadway for the purpose of business and seclusion. One Saturday afternoon

when I was alone in that many-roomed building, all other occupants having

left, a creature with quiet manner, a pretty auburn beard, and sharp,

useful eyes, of about thirty years of age, walked noiselessly into the

middle of the inner chamber, I having left both doors unlocked. He was

what was known in the city as a "sneak thief." He pressed me to buy

pencils of him. I observed that he took an inventory of two open trunks

which I kept there, and that he meant to come again. When I was in Kansas

City he did. As I had taken the precaution of throwing newspapers over the

trunks he appeared not to have observed them, and carried away only some

articles of clothing which I had left out, and a large illustrated work of

my friend's, entitled the "Origin of Life." The clever police captured

the pencil seller, but as I was far away at the trial and could not claim

my clothing, it fell to the police, at which I was glad—as I suppose they

were—for the articles were English, new and good. I lost nothing else

during my sojourn in the land.

Once, when I was a guest of Mr. Alderman Samuelson, brother

of the member for Danbury, at a Boston hotel, an umbrella, which I had

bought of a London Jew, because it was unlike any other, disappeared from

the place where I had placed it. My host spoke to a shrewd black waiter

and said in his emphatic way that it was necessary that the umbrella

should reappear, as it belonged to his guest. When I came to leave the

hotel I found it where I had placed it.

The impetuosity of New York was in everything and everybody. The painted signboards relating to the telegraph offices contained

animated figures of men and juvenile messengers, racing as though a fire

engine or Milton's Satan was after them. The mahogany tables of the

Western Union Telegraph Office, on which the public write messages, are

covered with great sheets of plate glass, which gave them a cleanness and

brilliancy very striking. As there are several of these, the appearance of

the office is that of a drawing-room. The public in England have no

accommodation of this kind. Sitting there alone and late one Saturday

evening, while a friend was arranging some messages upstairs, I passed

from meditation to sleep. Immediately my eyes were closed, a sharp youth,

from some unseen room, awakened me. I assured him I had no intention of

passing the night there; but three times, when sleep overtook me in the

large and deserted room, he promptly issued from his recess and desired me

to look about. I concluded that nobody was allowed to go to sleep in New

York under any colorable pretext.

Occasionally I went down to the Astor House, because I liked

to lunch at the great, broad, circular table, with the waiters inside, who

serve you so promptly; and also to watch business men eating, though I

cannot say I ever saw it done. "What do you think of it?" said Mr. Barnum,

as we came out. My answer was, "All I observed was that a gentleman

enters, reads the bill of fare, speaks to the waiter, pays the cashier,

and departs. He has, doubtless, taken his dinner; but the operation is so

rapid that I cannot say properly that I witnessed it." Yet in the clubs

and private houses, where I was at times a guest, I found that the dinner

was eaten as dilatorily and as daintily as in an English mansion—besides

including a greater number of delicacies. Americans, as a rule, know how

to dine like gentlemen.

In "Appleton's Guide," as I construed it, No. 1, Broadway,

was the Old Kennedy House, and that Fulton (the inventor of steamships,

whom Robert Owen aided in Manchester) died in one of its rooms; that

General Sir Henry Clinton (grandfather of my friend Colonel H. Clinton,

who has never forgiven the Americans for defeating his famous ancestor)

once resided there; as afterwards General Washington and Talleyrand (the

"lame fiend" who tempted Cobbett to teach him English).

On my first night in New York I engaged a room at No. 1, now

the Washington Hotel. There are spacious rooms in it, where a cohort of

generals and diplomatists might confer. The hotel looks out on the Bowery

in front and Castle Gardens on the right. The associations of the place

were very pleasant to me, but as the hotel was full of old ship

captains—whose talk was of cargoes, storms, shipwreck, and blockade

running, and in every language but English—I did not find a human being

to converse with on any topic. I understood my room was on the fifth tier,

quite removed from the lower part of the hotel. There was no speedy

communication below, and nobody to be met with above. I felt utterly

solitary and lost. Notices told me that certain passages led to the fire

escape. Being so far above the ground it occurred to me to study them. I

pursued them through as many corridors as Mrs. Radcliffe found in the

Castle of Otranto. After ascending narrow stairs I suddenly entered a long

room, where six stalwart Irish women were engaged at washing tubs. As they

all looked at me at once, wondering what brought me there, I retreated,

well confused, saying I "thought they were the fire-escapes." I preferred

the fire to going any further.

My room was one, no doubt, once occupied by the Hessians when

the Duke of York was there. The bell-rope had, I concluded, been broken by

those valiant troopers ringing for beer, and had not been repaired. So

desolate was that chamber that I should have been glad to invite their

ghosts in, had any been about the deserted corridors. Once I hoped it

might be the room where poor Fenton died, and had Spiritualism been true I

might have had conversation with that clever inventor.

In the early morning I heard strange noises under my window,

which at first I thought must be some Hessian or Fulton visitation. Upon

looking out I found the elevated railway almost running through my

bedroom, and a stoker stood by his engine turning off his steam. His

engine was No. 99, and I was told that the other (98) would probably be by

before breakfast.

The elevated railway is a wonderful contrivance of iron

architecture; nevertheless beautiful streets are disfigured by it, just as

we have cut the view of St. Paul's Cathedral in London in two by the

railway crossing Ludgate Hill. Had the people of New York possessed St.

Paul's they would never have tolerated a railway before it. I was some

weeks before venturing upon a journey through the air on it; when I did, I

watched for the open bedroom windows on the way, to see which I could best

leap into, in case the dubious thing gave way altogether.

|

|

|

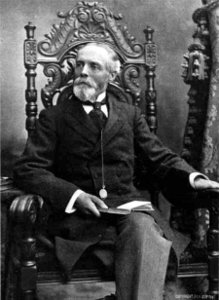

Whitelaw Reid

(1837-1912) |

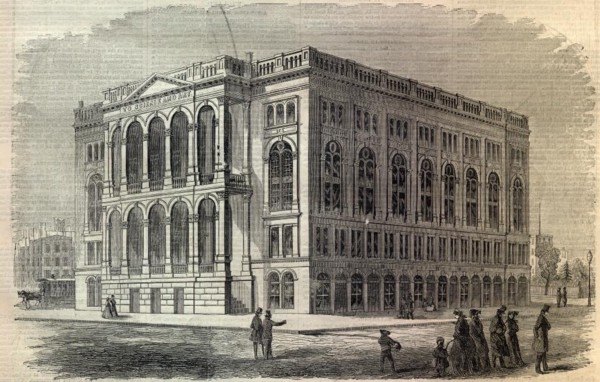

The New York "Tribune" office is the noblest newspaper

building I had seen. Its lofty tower, where the editorial and type rooms

are, overlooks the great post-office, a small sea, and all the great

buildings around. Printers may live longer there than in any office I

know. The spacious and high chambers, with abounding ventilation, insures

the health of the men. Every telegraphic, telephonic, and pneumatic

convenience perfected, is in operation there. Clocks around show the time

in distant parts of the United States, and in the chief capitals of

Europe. Everything shows the taste and resources of Mr. Whitelaw Reid, the

editor, who devised the arrangements. The "Ledger" offices of

Philadelphia, and other cities are distinguished also in their ways, but I

had not the opportunity of examining them.

|

|

|

New York Tribune Building.

Erected 1873-5. |

The plan of travel I had made for myself was simply to see

New York, Boston, Washington, and Philadelphia. I knew it was impossible

to see every place in America, and I did not intend to try. To see a few

of the chief things in any town, or a few of the chief places in any

country, and see them well, easily, and without fatigue, is my idea of

travelling. Men must travel as they read books. No one could read all the

books in the world, however interesting they are, and he who attempted it

would die discontented through not having accomplished it. So I select a

few of the objects and places I most care for, and have perfect enjoyment

therein.

When my intention became known in New York some friends put

it into a paragraph, and the Associative Press telegraphed it, I was told,

to one hundred and twenty papers. When I expressed my surprise at this, a

friend said, "As you are going up the country we wish to give you a good

send off." I had never heard the phrase before. It was some time

before I got reconciled to it. It had such a strange sound to me. It would

never enter into the mind of any Englishman to use it. It was merely the

American way. It is their habit to look clean into a thing, estimate what

it amounts to, and if an act of service or friendship to a stranger to

"put it through."

The "Mail" said that "old anti-slavery citizens would not

forget a criticism of mine in the "Leader" (1851) of the Garrisonian

agitation, which called forth a reply from Wendell Phillips, the most

argumentative and brilliant of his great anti-slavery orations."

The New York "Tribune" had at times made mention of my name, in connection

with some English affairs it thought of interest to its readers, in terms

which were of the nature of a letter of recommendation to me everywhere,

as I afterwards found.

The New York "Herald," though democratic, and of the opposite

politics to the "Tribune," recorded proceedings in which I was concerned,

as did other journals.

One morning the "Tribune" mentioned that I was staying at the

Hoffmann House, whereby it came to pass that I saw many distinguished

citizens. Introductions were sent me to the great clubs—the Union, the

Century, and the Lotos, where I spent enchanted days amid the pictures,

books, and stately chambers.

One afternoon I met the members of the Press Club and was

invited to address them. Journalists, men of letters, men of science,

travellers and thinkers of many lands, as well as of America, were there. The proceedings, I was told afterwards, were a "reception," but I did not

know at the time what it was. It was well I did not, for I should have

been confused at the disproportion of so much courtesy to any merit on my

part to justify it.

In New York I had the pleasure to meet again with Garibaldi's

well-known naval officer, William de Rohan, who took out the British

Legion in the Italian war of freedom. He had lost nothing of the high

spirit and vivacity which characterized him in that undertaking. I found

him engaged in promoting colonization in Virginia, of which he published

the best account for the information of emigrants I saw in the States.

It was my intention to sail in the "Scythia" early in August,

as Mr. Potter, M. P., was going out at the same time. His sailing becoming

uncertain, I changed my vessel for the "Bothnia," which sailed mid-August,

in order to arrive after the August storm, which breaks over New York at

the end of August, had cooled the air. I was willing to go earlier and be

roasted in company, but felt no call of patriotism to be roasted alone. Mr. Potter and I never met until we were on board the "Gallia," on the

return voyage. Mr. Potter, and Mrs. Potter who accompanied him, were

received with honor in America, to which he was known to have rendered

great services.

Mr. Evarts, the Secretary of State, made one of his most

brilliant speeches at the dinner given to Mr. Potter in New York, where

Mr. Evarts sent the memorable message to Mr. Bright that "the people of

the United States hoped he would not die until he had seen America." Mr.

Potter made wise and excellent speeches during his visit, saying, with

great judiciousness, very little about free trade, which it was known he

was desirous of promoting. For myself, though a partisan of free trade, I

elected never to allude to it, having discerned before I went, that the

best advocacy of free trade in America is to say nothing about it,

Americans being apt to believe that when an Englishman recommends it to

them, he does so because it is a national interest of his own. They do not

understand that we see free trade to be as much to their interest as to

ours.

The South being unfortunately in favor of free trade, the

North regard it as a sort of Copperhead policy, and are prejudiced against

it. As South and North become one again in sentiment and fraternity, which

increases every year, it being their common interest to be united, the

wonderful business discernment of America will lead them to see,

eventually, that free trade is the profit of their country. And they will

see it sooner if they find we do not solicitously intrude it upon them.

On the day of my arrival in New York I walked out into the

city alone. Not having mentioned to any friend the name of the second

vessel I had taken a berth in, there was no one I knew on the shore, and I

went peering amongst the Rotterdam-looking houses which I first

encountered, and saw the strange city for the first time for myself, and

by myself. I knew of no address save that of my early friend and

fellow-student, Dr. Hollick. When I reached him he handed me a letter,

which was an invitation to the office of the "Worker," 1455 Broadway. It

was from Mr. E. E. Barnum, Secretary of the Colony Aid Association, who became my friend, and was my friend always. He was a man of singular

modesty, with an entirely honest voice, of quiet, unobtrusive ways. Though

he was much trusted, he left nothing on trust, but presented a clear

record of all transactions passing through his hands.

He had been a minister of religion, and retained the

agreeable self-respecting manners of one of the better sort. He was taken

by his father in early life into the prairie, where the hardships he

shared made him a wise and practical counsellor of emigrants. He

accompanied me to Saratoga, as I was new to American railroads. By day or

by night he would accompany me about New York. When I returned to the city

he would meet the early boat when I arrived in the morning. If I returned

by late train, he would come over the river to meet me, lest my being

unable to see in the dark should cause me to take the wrong boat. It was

with real sorrow that I received not long ago a letter from Mrs.

Barnum—who also had shown me attentions of genuine courtesy—a letter in

which she said:

"It is very hard for me to tell you that the busy feet that

ran for you, and the bright eyes that looked for you are still and closed. He regarded you with so much love and tenderness. He was only ill for two

weeks, and passed away like a child going to sleep. He had been looking

forward with so much pleasure for your return. As you knew him so he

always was—as gentle and kind to every one; and we were such friends and

comrades. I realize that all the world and myself could die, but not him;

and until he had passed away it never entered my mind he could die. He was

the only one I had, and now I am indeed desolate."

Mr. Barnum cared for co-operation for the sake of its moral

influences, and he had the capacity, which does not always go with right

feeling—the capacity of giving effect to principles by material

organization.

The Co-operative Colony Aid Association have objects wise,

practical, and unpretending, expressed with moderation and good sense,

which I never knew exceeded in England. The qualities are much more common

in America than Englishmen know. In England, journalists tell us much of

points in which America differs from us, or falls below us, and too little

of the points in which its people equal or excel us.

|

|

|

The Cooper Union

for the Advancement of Science and Art. |

The association I mentioned invited me to deliver an address

in the Cooper Union. It is not possible to collect in London an audience

such as I met there—men of thought and action of all nations,

representatives of all the insurgency of progress in Europe are found in

New York, as well as the men of mark who arise in that mighty land. I met

there for the first time the Rev. Robert Collyer, the famous preacher of

Chicago, and Mr. Peter Cooper, who was then in his eighty-ninth year. He

gave to New York the great Institute in which we met. He is a man of fine patriarchial appearance. He made a bright, argumentative, freshly-spoken

speech. Professor Adler, a Jewish orator of great repute, the Rev. Heber

Newton, an Episcopal clergyman, a man of fine enthusiasm, and the Rev. Dr. Rylance, who knew me in London many years ago, spoke after the lecture. The platform of the hall is very wide and projects into the middle of it.

The hall is so spacious that it is like speaking into a town, and the

lecturer is as a voice speaking in the midst of the people. Everybody can

hear him. American architects have a mastery of space unknown in England,

and in their halls and theatres, everybody can see everything, and the

speaker meets the eye of all whom he addresses.

|

|

|

Peter Fennimore Cooper

(1791-1883) |

When I went down to Liverpool to embark for America I was

invited by a committee of journalists, and other gentlemen, to a public

dinner there, at which Dr. Thomas Carson presided, and Mr. E. R. Russell,

editor of the Liverpool "Post," and other gentlemen, made friendly

speeches to me, but it never occurred to me that this would happen to me

in America. Yet it came to pass before I left New York. A public breakfast

was given me in St. James' Hotel, Broadway, eighty persons were present,

though the tickets were fourteen shillings each.

He should be very reticent who writes of himself, yet entire

silence would be an ungrateful or contemptuous return to make to those to

whom he becomes indebted. Mr. Peter Cooper was present at the St. James'

Hall, as well as the gentlemen who spoke at the lecture at the Cooper

Union. Mr. Whitelaw Reid, the editor of the New York "Tribune," sat on the

left of the chairman. Here I met for the first time Mr. Parke Goodwin,

son-in-law of Bryant the poet, himself the editor of the "Evening Post,"

and Mr. E. L. Godkin, editor of the "Nation," a journal which resembles

our "Saturday Review." Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson, a lady distinguished for

countless and discerning acts of national munificence, and other ladies

were present. The Rev. Dr. E. H. Chapin, whose impassioned eloquence I

often heard spoken of in America, and the Rev. Dr. E. A. Washburne, had

travelled far to be there.

I have preserved the many letters which were received from

heads of departments at Washington—from Wendell Phillips, Colonel Robert Ingersoll, George Wm. Curtis, and others. One was from Mr. R. B. Hayes,

President of the United States, who, though engaged all day at a military

fair, and under a public obligation to return to Washington that night,

took time to write, saying: "It would give me pleasure to accept the

committee's invitation to join in breakfasting with Mr. Holyoake, and

thereby show my appreciation of the work in which he is engaged, and I

regret that imperative engagements to return to Washington immediately

prevented me attending the breakfast."

It never entered into my mind that anything I had done could

be known or could interest persons so numerous and so eminent, in a

country so remote from my own. All my days I have been among those who

wrote and spoke in defence of the Republic from instinct. The New York

"Tribune," in a graceful expression, ascribed the proceedings "to my

earnest and fruitful friendship for America."

The utter unpreparedness with which I was called upon to do

things in schools, churches, or public meetings, at first perplexed me. In

England, when any one is entertained, the chairman makes a speech and some

proposition is spoken to, after which the guest speaks. By this time he

understands something of the sentiments of the assembly, and what ideas

had been formed of him. At the New York breakfast I expected the same

course would be followed, and was sitting with perfect unconcern,

expecting to hear the Rev. Dr. Newton, who acted as secretary, read the

letters received, when the Rev. Dr. H. W. Bellows, the chairman, who had

spoken with gaiety and humor, and with a felicity of expression which I

was envying and admiring, suddenly "presented" me to the meeting, and said

I could address them, I knew not what to say, not having had time to

consider what there was available in the chairman's speech. I thought

again of the curate who, when Archbishop Whateley asked him if he had

prepared his trial sermon, said he had not, as he trusted to the promise

that in that hour in which he had to speak it should be given unto him

what he had to say. "But you forget," said the Archbishop, "that that

promise was made to an apostle, and unless you are sure of being one, the

promise may not hold good in your case." As my apostolate was one thing

of which I was doubtful, I had to speak and take my chance of the

"promise." The speeches which followed mine were so admirable that they

seemed to have the aid I lacked.

It was impossible not to be sensible of the things said to

me, seeing that I had neither rank, nor office, nor riches, nor even

ecclesiastical repute; nor could I bring to the country any distinction,

nor confer upon it any advantage. All the while it was known that when the

first volume of my "History of Co-operation in England" was sent to the

press by Messrs. Lippincott, the American publishers, the reviewers, with

three exceptions, reviewed me and not my book, and gave it to be

understood, that I was not known to believe half as much as a

"well-conducted" person should. Nevertheless, during my whole stay in the

country, not a single journalist ever alluded to any opinions of mine,

other than those I myself chose to express. When I think of all that

occurred to me, I feel upon returning to my own countrymen—who know me

better—that I ought to offer some apology for having received attentions

so much beyond any discernible merit of mine.

CHAPTER III.

THE REPUBLICAN CONVENTION AT SARATOGA.

THE pleasantest way to Saratoga from New York is up

the broad waters of the Hudson River in one of the great steamers, large

enough to carry a town. On the road you see the majestic and dreamy

Catskill Mountains, where Rip Van Winkle met the Dutchman playing at

ninepins.

Saratoga, being called a "watering place," I expected to find

lake or sea there; but found instead mineral springs, which are situated

in a picturesque vale, where fountains, foliage, statues, and shaded walks

prevail. Cheltenham and Harrogate together are not so alluring, but

there is not much of Saratoga. The principal street has lofty trees,

of a torrid fruitfulness of leaves and branches. The vastness of the

hotels was bewildering. That of the United States Hotel, where I

stayed, enclosed three sides of an immense quadrangle, as large as a park,

abounding in foliage. I was told 2,000 persons were residing in it

when I arrived. A thousand additional visitors, who came the same

evening to attend the convention, seemed to make no sensible addition to

those who conversed in corridors and saloons. The colored attendants

were ready and unconfused. In a few minutes you were in possession

of bedrooms as lofty as those of the Amstel Hotel, Amsterdam, where the

bed curtains appeared to descend from the clouds.

The object of the convention, called by the Republican

leaders, was to choose a candidate for governor of New York and other

State officers. My wish was to see not merely what was done, but how

it was done, and where it was done.

A public meeting in London is, except in the Society of Arts,

a mere proceeding, hardly ever a spectacle. There is nothing

imposing about it, save the grand throng of eager faces, if many are

present, and the mighty roar when a great speaker interests the assembly.

The hall of the Society of Arts, with Barry's great paintings around its

walls, on which are depicted the great historic actors of the world, who

are, as it were, listening to the speakers; the broad dais at the upper

end of the hall, its three table-desks, two being independent tribunes,

where speakers right and left of the president can take their stand—the

open side room where auditors can arrive, survey the meeting, and choose

the vacant place they prefer, or see and hear where they are—constitute

the one scenic hall of London.

The Saratoga Convention of 1879 was held in the Town Hall;

not a bad interior, but the stage had the ramshackle arrangements common

in England. There was more space than we reserve for speakers to

deploy in; but in the centre stood a mean, narrow desk, upon the hollow

top of which the president struck, with a pitiful wooden hammer, awakening

dilapidated echoes within. Nobody had thought that the grandest use

of a public hall is a public meeting, and that the mechanical accessories

of oratory should be picturesque, and yet have simplicity, but the

simplicity should be scenic.

Tammany Hall I did not see; but Faneuil Hall, Boston, has

quaint grace and fitness as a hall of oratory, worthy of the famous

speakers who have given it a place in history. No arrangement had

been made for delegates at Saratoga occupying the floor of the hall, and

for preventing any other persons entering that area. Ten dollars

cost, and two carpenters, would have done the work in two hours.

This not being done, the hall was one compact political mixture; and as

the delegates wore no flower, cross, medal, or badge, nobody knew each

other, nor who was which. This cost an hour's fruitless discussion,

and confusion all day. Twice over, at long intervals, a wild motion

was made that all who were not delegates should rise and stand in the

sides of the hall, and allow the delegates to be seated in the centre.

This proposition proceeded on the assumption that 600 persons who had

arrived early, and struggled their way into good seats, would rise by

natural impulse of disinterested virtue and disclose themselves, the

consequence being that they would lose their seats and be condemned to

stand all day if they were not ejected from the hall. This

extraordinary virtue did not appear to be prevalent, for no one rose.

By sitting still they were secure, for nobody knew them not to be

delegates, and they had the wit not to discover themselves. Indeed,

if they had, the hall was so densely packed that nobody could move to

another part, and the confusion of attempting to change places would have

been ten times worse than that which existed. I was surprised to

hear the impossible proposition made to an American audience. When

Mr. George William Curtis pointed out that it was an incoherent proposal,

everybody laughed at it.

I had heard in England a good deal about American political

organization. It did not appear in the arrangements of the meeting,

though it was well manifest in the proceedings. The names of the

candidates for the chief office in the gift of the day were read over.

The popular name was that of "Alonzo B. Cornell," the son of the founder

of the Cornell University. Mr. Cornell received the nomination of

Governor of New York State. That day I heard his name pronounced a

thousand times. Each delegate was called upon to say aloud for which

candidate he voted. There was only one Cornell, yet nobody answered as we

should do in England—"Cornell"—but each said, with scrupulous precision,

"Alonzo B. Cornell," or "Jehosophat P. Squattles," or whatever was the

name of the rival candidate. Alonzo was pronounced clearly; the B.

separately and distinctly, and Cor-nell with the accent on the "nell" as

decidedly as that knell which "Macbeth" thought might awaken "Duncan." The

name of "Alonzo B. Cornell" emerged from under the platform in a musical

accent, as though it proceeded from a pianoforte. "Alonzo B. Cornell" was

next heard in the rough voice of a miner. "Alonzo B. Cornell" came in meek

tones from a delegate appointed for the first time. "Alonzo B. Cornell"

cried an old sea captain, with a voice like a fog-horn. "Alonzo

B.

Cornell" came quick from the teeth of a sharp man of business, who meant

to put that affair through at once. "Alonzo B. Cornell" said a decided

caucus leader, in a tone which said, "Yes, we have settled that before we

came here," "Alonzo B. Cornell" chirped a small political sparrow in a

remote corner of the room. Then Mr. Conkling, raising himself to his full

height (which is considerable,) in the centre of the platform, pronounced,

in tones of a deliberate trumpet, "Alonzo B. Cornell." An hour was spent

over that new governor's name, yet if "Alonzo B." had been eliminated, the

business had been got through in a third of the time. Mr. Cornell was a

modest, pleasant gentleman, with a business-like method of speech. From

the interest which was attached to the course Mr. George William Curtis

took, I wished to speak with him, but could conceive no sufficient pretext

for doing it. One result of this was that afterwards a friend had to give

me an introduction to Mr Curtis, which ran thus:

|

|

|

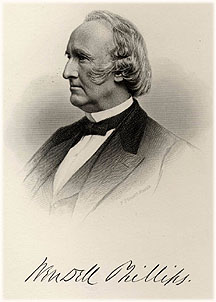

Wendell Phillips

(1811-84) |

"DEAR CURTIS:—This is George J. Holyoake, whose works on Labor and

Co-operation you know. * * * He saw you at Saratoga. With English

diffidence he did not introduce himself. I tell

him he must learn American manners. Till he does, let me make you

two acquaint.

Yours cordially,

WENDELL PHILLIPS."

The character of

every people, like that of every individual, is made up of flat

contradictions. The Americans, as a rule, have a prompt apprehensiveness;

their conversation is clear, bright, and precise; their penetration

direct; their narrative swift, characterized by brilliant abbreviations;

yet these quick-witted hearers will tolerate speakers in the Senate and on

the platform with whom redundancy and indirectness are incurable diseases;

and will sit and listen to them just as they would watch the descent of a

cataract,

until a change of season shall dry up the falling waters. At the Saratoga

Convention "a programme of principles" was read—called a "platform." No

discernment could make sure what was meant, and a professor of memory

could not retain half of what was written. All I recollect was that the

platform ended with some miscellaneous platitudes on things in general,

but yet there were parts of it which showed capacity of statement—if only

the writer had known when to stop. It was with regret I was unable to go

to the Syracuse Convention, and witness a Democratic nomination, and,

perhaps, furnish my friend, Mr. Herbert Spencer, with materials for a

chapter on "Comparative Caucusism." The Saratoga Convention was

characterized by great order and attention to whoever desired to speak. If

any one put a question, the answer was, "The Chair takes a contrary view;

the Chair decides against you." The chairman spoke of himself as an

institution, or as a court of authority. This I found to be a rule in

America.

I was told the Democratic conventions were marked by comparative

turbulence and irregularity. The New York "Tribune" said that

"large

heads" would abound at Syracuse. I wanted to see "large heads," as I had

no idea what a political "large head" was. I was told that the Democrats

are more boisterous and peremptory in their proceedings than Republicans. The Democrats seem to resemble our Tories at home—indignant at any

dissent at their meetings, but persistent in interrupting, the meetings of

others. At the Saratoga Convention the immediate attention given to any

auditor claiming to speak by the chair, and, what was more, by the

audience, was greater than in England. In

England the theory of a public meeting is that any one of the persons

present may address it, but we never let them do it. If the chairman is

willing the audience is not. At several public meetings at which I was

present the right of a person on the floor seemed equal to that of those

on the platform. Citizens seemed to recognize the equality of each other. In England there is no public sense of equality. Somebody is supposed to

be better than anybody.

While I was at Saratoga, one of the New York papers

said that "Mr. Conkling (who made the chief speech of the day), had two

attentive listeners upon the platform, to whom the proceedings were

evidently of great interest. One was Professor Porter, of Yale

College, the other, to whom the entire convention was an absolute novelty,

was George Jacob Holyoake, the English writer upon co-operation and reform

questions in general. Mr. Holyoake had come to Saratoga with the

sole purpose of seeing the convention, and seemed greatly interested in

its methods of procedure, and all its many aspects. He remarked to a

friend that he had been defending American democracy for forty years, and

had now come to observe for himself some of its practical manifestations.

He compared Mr. Conkling's manner of speech-making to Mr. John Bright's."

In what respects I afterwards explained in a letter to the "Tribune,"

saying:—

"I am a connoisseur in eloquence, as some men are in art. I have heard oft

many renowned orators. But though I have lived near the rose, it is not to

be inferred that I have caught the scent myself. It only means that I am

sensible of it when I come near it. That is what I meant

by the remark of mine you quoted the other day, concerning Mr. Conkling's

speech at Saratoga.

"A good presence is but an accident of oratory. Mr. Conkling has the art

to make it a condition and a grace. His singular and sustained

deliberateness, which never delayed, had a charm for me, that quality of sustainment being one of the difficulties—as it is one of the marks of

mastery—in eloquence.

"Mr. Conkling ended sentences at times with a simple brevity, where other

men would have lost power in expansion, which they mistake for force. Mr. Conkling's compression was completeness. These were the respects in which

his speech at Saratoga reminded me of Mr. Bright."

The favorite water of Saratoga bears the name of "Congress water," and it

was the first natural mineral water I found agreeable to drink. If

Congress politics are as refreshing as "Congress water," America is not

badly off in the quality of its public affairs.

[Next Page] |