|

[Previous Page]

OLD GARMENTS.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

IN the High

Street of a certain well-known provincial town stood the house of

Doctor Hook. The house was of red brick, faced with grey

stone, and boasted the whitest of steps and the brightest of brass

knockers: an old-fashioned, substantial house, with an air of

old-world stateliness about it, which its newer and finer neighbours

somehow lacked.

Doctor Hook was by no means the first physician in the town,

as far as reputation went. He stood third, perhaps not for

want of ability, for the Doctor towered above his fellows in mental

as he did in physical stature. He could see far more clearly

and surely into the nature of a disease than could his opposite

neighbour, Doctor Dunscombe, who rattled about in his carriage and

pair, dressed so splendidly, and who spoke with such a tone of

authority. And he was a far sweeter natured, more sympathetic

human being than Doctor Blandford, of Blandford Villa, in the new

town, who drove in a dismal little close pill-box, moved upon the

tips of his toes, as if constantly fearful of awaking a sleeping

patient, had upon his face a look of perpetual concern, and spoke in

a tone hardly above a whisper.

Yet Doctors Dunscombe and Blandford occupied posts of honour

in the Infirmary, and were selected, in turn, by their

fellow-citizens to be put forward on great occasions; whereas Doctor

Hook was totally ignored. Of course, he had his patients, who

swore by him and by him alone, and took the liberty of applying to

the treatment pursued by his rivals a word of obscure etymology, but

clearest meaning, viz.—humbug.

Doctor Hook went his own way, and that way was not, at the

time we would indicate, an altogether evil way. To all outward

appearance, indeed, it was an excellent one. He drove about in

his open, decidedly fast and unprofessional vehicle, a picture of

health and energy, doing his patients good by his very presence and

by his cheerful voice and cheerful views, and staying longer with

them sometimes than he need have stayed, because he did them good

thus—more good than medicine, some of them said. Then he came

back to his home and his wife; and few men had such a home and such

a wife—a home in which comfort and refinement dwelt on equal terms,

the one never encroaching on the other; a wife with a mind at once

cultivated and original and a heart full of wifely devotion.

Mrs. Hook was at this time a fine, handsome, middle-aged woman, of

high mind and still higher temper; but who, in spite of her temper,

which showed itself only in a certain hardness to offenders, lived

on terms of the most unbroken felicity with her husband.

At holiday times there was also his schoolboy son, a

repetition of himself, with just an additional dash of spirit, a

frank, headlong, passionate, yet humorous and kindly lad. The

persistence, amounting to obstinacy, which young Spencer showed on

occasions only gave his doting father room to hope still greater

things of him. Just for want of such a resisting power, he

himself had stuck at what he was. Thanks to his high-minded

Martia that he had not sunk a good deal lower. Time was, it

was said, when the Doctor's doings had not been so correct; and it

was singular how retentive were the memories of his fellow-citizens

concerning that time. Doctor Dunscombe still spoke of it in

clearly actionable terms, and Doctor Blandford shook his head over

the terrible effects likely to result from dissipation in a man

entrusted with the keys of life and death, as he grandiloquently

phrased it. Neither of them associated with Doctor Hook,

though they were very civil to him when they met, and this also

Doctor Hook went on his way unheeding. His life would flow

along in any channel deep enough to hold it, like a strong stately

river, or it might dash itself in steep and narrow places, over

every barrier like a desolating flood, but it would never stagnate

in the shallow slimy pools of envy and jealousy.

Besides, he had no further ambition for himself. It was

all centred in his son. Spencer would carry everything before

him. He had distanced young Dunscombe at the school. He

would go to college directly, and distance half a dozen Dunscombes.

Spen. would take to the great art of healing. Spen. would make

a reputation; not a shabby provincial reputation, but a national,

perhaps a European one. The lad at his grammar-school had

already begun the study of physical science, and was already

enamoured of his future profession, and eager to make all the

learning of the schools subservient to it. Spencer was in very

truth a boy of splendid promise, and both father and mother seemed

to hold their lives bound up in him.

But how had Doctor Hook earned such a reputation from his

fellow-townsmen? Had he indeed earned it? or was it made up of

envy, hatred, malice, and all uncharitableness? The strangers

who came to settle in the place so thought and averred. The

Doctor regularly attended the Cathedral services. Nobody

enjoyed a beautiful anthem more than he. His domestic

relations were perfect. His conduct irreproachable. His

money matters correct. His dealings just and liberal.

Nevertheless, there was truth in that accusation of

dissipation which stuck to him, though it was a thing of the past.

He had come to the town a young fellow of twenty-one, whom nobody

knew, as assistant to his wife's father, Doctor Leighton, who lived

in the very same house which his son-in-law still inhabited, and

was, in his day, the first doctor in the town. The young man

took everybody's fancy by storm. He was so handsome, so

good-humoured, so clever. His qualities of head and heart

gained him the esteem and love of the good old doctor and the

affections of the doctor's only daughter, Martia Leighton, then a

very beautiful girl, a couple of years his senior, and her father's

housekeeper, and general adviser besides.

The young people were at once attracted by each other.

Spencer Hook fell in love with Martia on the very first evening of

their acquaintance, as she sat at the head of her father's table, so

sweetly, and yet so stately grave. He has a picture of her as

she was then, in the very dress she wore—a puce-coloured silk, cut

very low, with a fall of delicate white lace over the bosom, and a

couple of strings of pearl round her slender throat, golden brown

curls invading the ample forehead, crisp round curls like those on

the head of a young child, and the hair behind rolled up, nearly on

the crown of the head, in a subdued and more graceful version of our

modem fashion.

Spencer Hook was engaged to Martia Leighton within the year;

but her father was cautious in giving her, his all (and everything

he had went with her), to the young stranger. He insisted on

their waiting for two more years, at the end of which he would make

a partner of his future son-in-law, and then allow the marriage to

take place at once.

It was not good for young Hook this waiting, especially as he

had by no means enough to do, and, young as he was, he had already

imbibed a love of so-called pleasure. For a year or two before

he came to Doctor Leighton, he had, while pursuing his studies at

Edinburgh with the utmost success, been spending his little

patrimony in riotous living, the companion of the fastest of his

fellow-students. Having at length come down to the husks, and

not finding them pleasant eating, he had formed and acted on the

best of resolutions: he gave up his indulgences, forsook his boon

companions, and, having taken his degree, began at once to seek for

employment. It might have been better for him if he had found

the return path a hard one. It was all very easy. He

lighted upon Doctor Leighton, and comfort, and respectability, and

good prospects all at once.

Spencer Hook came from the north of England. There

still lingered in his speech, and would linger till the end of his

life, a trace of the Northumbrian burr. He had come of a

stalwart, vigorous race too—of that there was evidence in his broad

shoulders and ample chest, in his stalwart figure and clear though

dark complexion. But they were a race, too, of strong passions

and strong propensities, who loved to dare the very verge of moral,

as they did of physical, danger. Spencer's youth had been

overshadowed by a great calamity—the greatest of all calamities, a

vicious father. Only a tender and devoted mother had stood

between him and that calamity, and had spent herself in the effort

not only to hide and screen his father's vice, but, when it could

not be screened or hidden, to make as light of it as possible, in

her desire to save him from pain and shame.

Shirley Hook was one of the smaller proprietors of the

county, but he had entered upon life with an embarrassed fortune,

and had already cut off in his father's lifetime the entail of his

property before he met the lady whom he ultimately married.

She was without fortune, except a single thousand pounds, which were

settled on herself. It was a love match on both sides, and to

that love the lady trusted for the salvation of the man she had

married. Whether there was originally any virtue in him no one

knew, but he was a fearfully dissipated man when Spencer's mother

married him, in the hope of reforming him. She had surely seen

the possibility of better things in him, or she would not have

entered on the task which seemed to others hopeless.

And for a time she appeared to succeed; but the appearance

was a deceitful one. Suddenly, and as it were without the

least provocation, he broke out again and became worse than ever.

Possession, infatuation, are the only fitting words to apply to his

conduct, for he would sin and be exceeding sorry; be exceeding sorry

and then go on to sin. And every time he did this he became

distinctly worse. The evil seemed to invade a greater and

greater portion of his nature, to take a firmer and firmer hold of

his life. Each time a larger extent of his property was

recklessly gambled away, each time greater inroads were made on his

constitution, each time the will of the man seemed more hopelessly

enslaved.

Time after time would come a period, growing briefer and

briefer, when his unhappy wife would venture anew to hope, when,

yielding to her pleadings and remonstrances, he would become sober

and sensible—nay, even set to work to retrieve his fallen fortunes.

But in vain she thought, "Now I will screen him from every

temptation; I will never leave him, waking or sleeping; I will be

with him when the tempter comes to him, and help him to overcome."

In some way or other he would manage to elude her vigilance and to

disappear, returning more spent and broken and hopeless than ever,

till the very poison which was killing him became a necessity of

life. Whenever the impulse came (whether it came from without

or from within, driving him, like one whom Satan drives, into the

wilderness) he was whirled once more into the vortex of vice, which

must one day destroy him. And he knew it. He knew he was

breaking the heart of his wife, and yet he went on breaking it.

He knew he was killing himself, but with the very pains of death

laying hold of him he would drink the poison which roused their

fangs of torture.

At last it came to this that the man had no will except to do

evil, and that continually. He had lost everything that he

could lose, except life and soul, and these he was ready to stake on

the fatal self-indulgence. He had lost his property to the

last acre; he had lost his health; he had lost name and fame, and

even friends, the lowest and the worst of them; he had lost his very

manhood. But the strangest thing was that, among all his

losses, he had never lost the love of his devoted wife. He had

disappointed her hopes; he had ruined her prospects. He had

given her for her youth and her love only trouble and anguish, and

she loved him still. There must have been something in him

worthy of it surely.

All that she could do at last was to screen him from the eyes

of his son, for a son had grown up in their home to the verge of

manhood. He was sent to school at an early age away from home.

His mother yearned to keep him, for he had been her chiefest

solace—a gentle, loving and yet brilliant boy; but it was not to be

thought of. Her life was one constant self-sacrifice, and she

saw as little of the lad as she possibly could. Often at

vacation-time had Spencer been bitterly disappointed, and that too

in his warmest affections, by being sent somewhere else instead of

home, while some elaborate excuse was given why he could not be

received by his parents.

It was only in her letters that the mother's heart flowed

forth, and in them Spencer learnt to worship her. At length he

went up to college, and she knew that the time was coming when her

son must know the full extent of his father's misdoing, if he had

not already guessed it. No more excuses could be made to keep

him from home, and at home the truth must be revealed to him.

When she could no longer, therefore, screen her husband she

made light of his sins—a false and fatal step not successful in

deceiving her son as to their extent and disastrous consequences,

but confusing and darkening the young man's conscience and judgment

concerning them, apart from their consequence.

She did not live, however, to reap the bitter fruits of the

seed which she had sown. And her son was destined to be

orphaned of both his parents in his early youth. During his

first and second college vacations his father had conducted himself

better than usual. He had not left his home, nor had he

behaved in any outrageous manner. His wife had bribed him, as

it were, by supplying him with more than the ordinary allowance of

drink, to remain quiet; and he had remained quiet, though often in a

state of inebriation.

When Spencer returned at the end of his third year, his

father was not visible. His mother said he was ill in bed and

under the influence of an opiate. The son knew but too well

what that meant, and reconciled himself to his father's absence, but

it was more than usually intolerable. It had been a late and

cold spring up among the hills, and the house was in a lonely and

exposed situation. It was more like the beginning of March

than the end of April, and the wind howled round the house, when it

was shut in for the night, like a host of demons seeking entrance.

Spencer's mother had received him with an anxious and

pre-occupied air, and her absences were frequent even in the course

of seeing him enjoy his first meal at home. At length she

disappeared altogether, and Spencer thought he heard strange noises

in the house, especially in the pauses of the wind.

An old servant came to him at last, and told him, with a

scared face, that he must go for the doctor, his father was worse

than usual—in a dangerous state in fact.

He jumped to his feet, and in a moment was ready to go; but

he wanted to see his father first, or at least his mother, and would

not take the old servant's "nay," though she had nursed him when he

was a little child. He, too, was scared, as he went along the

passages of the rambling old house, by frantic shrieks, which were

certainly not the wind. But the old woman had gone on before

him, and entered the room where his father was. And his mother

came out of it, and turned him back, and entreated him to go for the

doctor.

He went, battling with the wind under the starry night; but

the doctor, who lived three miles off, was absent, attending a

woman, still further up the valley. Spencer followed, and

brought him back with him, but not till half the night was spent.

And in the meantime what had transpired in the room where the

wife watched over the husband, in the terrors and agonies of

delirium tremens? Fearful fancies took possession of him, and

kept him crouching in corners, stretching out the palms of his hands

to keep off his ghostly assailants. Then a fit of fury would

seize him, and he would spring at his wife with uncomprehending

eyes, evidently taking her for one of his fancied foes. She

managed once or twice to elude him, but at length he closed on her,

and held her with crushing force. Still she used her voice to

soothe him, and wrestled with him gently without calling for help.

She would not cry out even for mortal hurt, and mortally hurt she

was in the struggle, before the unhappy man sank into the stupor

preceding death. In his ravings he had managed to stab her

with a pocket-knife which he had concealed in his hand.

And to the very end she screened him. When he was dead,

and she too was dying, she would not allow her son to be told of the

manner of her death. Only the doctor and her faithful servant

knew. She feared that the horror of it would blight his life,

which would be sufficiently sad and desolate without such knowledge.

It was hidden from him without positive falsehood, for she was

suffering from heart disease as well; but it may be questioned

whether she was right in saving him from the sadder knowledge which

was hers.

It is a natural and generous impulse which tries to save the

young from the knowledge of the deepest evils and from the pressure

of the hardest necessities of life; but to hide from them the

consequences of sin is another thing. In these the voice of

God speaks, and speaks in a language which the youngest can

understand. Be that as it may, she died and made no sign, and

Spencer was thrown upon the world a solitary orphan. His

mother's thousand pounds came to him the day he was of age, and a

little from the sale of his father's house, and he chose the

profession of medicine, and continued his college career.

As is natural in youth, his grief for his mother soon faded

away. There was no restraint upon his actions, and he took, as

if by instinct, to a life of indulgence in pleasure. Was the

taint wrought into his nature, the dreadful taint which would not

wear out save with the very blood and the brain of him who owned it?

and would it end in destroying the heart and conscience, the energy

and will, and self-control, nay the very soul itself?

As yet his pleasures were social rather than sordid; he was

gay and reckless rather than vile; but young as he was he had tasted

the cup which brings longing to the lips, only not yet was it

unquenchable. Spencer Hook had a fine nature, and we have seen

that at this point he righted himself and played the man. He

had inherited his mother's virtues as much as his father's vice, and

none could say what the result would be in the future which was

still before him.

CHAPTER II.

DOCTOR

LEIGHTON'S

patients took to his assistant immediately, especially the younger

farmers and squires of the neighbourhood. Of necessity he was

out among them at unseasonable hours, and out among them meant

drinking freely. But he kept within bounds, and for a long

time this went on unnoticed. He loved Martia passionately; but

the quiet evenings at her father's fireside, with the doctor snoring

in his chair and Martia sitting opposite with her embroidery, chafed

his eager spirit, till he would drive out into the night with glee,

to join some jolly set in one of the country houses in the

neighbourhood, where the guests would stay on till morning broke in

upon their revels.

Such conduct could not long remain hidden, and accordingly it

came to the knowledge of Doctor Leighton, who remonstrated in no

measured terms—indeed, withdrew his countenance and favour from him

at once, and without any promise based on future amendment.

The doctor was terribly disappointed, and in the bitterness of his

disappointment told the young man that he must consider the

engagement between him and his daughter at an end.

When Martia also avoided him, and would have nothing to say

to him, all hope seemed at an end. He flung his good

resolutions to the winds, and the town was soon ringing with his

noisy misdeeds.

"Doctor and Miss Leighton are quite right to have nothing to

do with such a scapegrace," said the public opinion of the place;

but a lofty instinct whispered to Martia Leighton, "We are quite

wrong. We, and we alone, can save him. We, and we alone,

are sending him to destruction. What this man needs is not a

fear and a torment—it is a forgiveness, and a love which shall

overpower his nature and save him from his very self." It was,

indeed, that which he needed; but Martia Leighton did not know that

it was a love and forgiveness higher than her own, a love and

forgiveness which should have power to renew that nature of his, and

not merely to patch it over, like new cloth upon an old garment.

Martia's mind was of no common order; it could not linger in

indecision. Having listened to that whisper and accepted the

conviction which it carried to her, she lost no time in acting on

it. Instead of avoiding Spencer, she sought him on the first

opportunity, while he waited in the consulting-room the return of

Doctor Leighton from his morning round of visits.

Spencer Hook was sitting in her father's chair when Martia

stole softly upon him. He was thoroughly depressed and

miserable, and had covered his face with one of his hands as he sat.

He was in fact meditating a request to Doctor Leighton, and that

request was to allow him to break free from his business engagement

and leave the place. He could never hope to be so fortunate

again. He had been an utter fool. Probably he would be

an utter fool to the end of the chapter, and throw away other and

lesser opportunities as he had thrown away this one, till he sunk to

the dismal dregs. What matter! there was no one to care—no

mother's heart to break, no father's grey hairs to bring down with

dishonour to the grave.

Martia stole upon him, and stood beside him before he was

aware—stood over him at her full stately height, and spoke the words

of warning which came to her lips. She knew what he would say,

and he said it. He said, as he had thought, that there

was no one to care. That since she had renounced him he was

utterly reckless. He had not been reckless heretofore, he had

only yielded to temptation, and she did not know what the

temptations of his youth had been. He was unworthy of her, had

always been unworthy; and the best thing she could do was to forget

him, and let him go his way, and that way was the way to ruin.

But she had known also what she would answer, and she

answered. "I have not given you up; I hold myself bound to you

still. Your way will be my way; your ruin my ruin."

He had started up when she began to speak. As she spoke

his whole soul was stirred. He had loved her before with

youthful, passionate ardour, which clung, as it were, to the outward

form of beauty, but now, for the first time, there stood revealed to

him the woman's soul, and his love changed in a moment into a

passion absorbing the whole spiritual force of the man.

"No, Martia," he answered, standing erect and ennobled.

"The sacrifice is too great. I have never loved you as I love

you now; but I will not link your fate with mine. I will try

to be worthy of you even thus far; but I cannot be sure of myself.

It is in my blood, this beastly craving. My father died of

delirium tremens."

"You are not free, Spencer," she had answered, and quitted

the room as her father entered it.

It was certain that Spencer Hook did not ask to be released

from his engagement to Doctor Leighton, otherwise he would have had

no difficulty in that direction. He stayed on, and his conduct

became again all that could be desired. When others drank wine

he drank water, though he did not profess to be a total abstainer,

and such was the hilarity of his spirit and his general bonhomie

that he escaped excessive pressure with comparative ease, but the

wine-drinkers themselves never forgave his defection and never

believed in his reformation.

At the end of the two years, Doctor Leighton withdrew his

embargo on the engagement, and Spencer Hook was married to Martia

Leighton. But the town had never forgotten that curious

outbreak of his, and those who did not know him still credited him

with a secret love of liquor.

There never was a happier union than that of Spencer Hook and

his wife. Their companionship was perfect. They seemed

never to need any society save their own, and therefore their

society was charming. In the first year of their marriage two

events had occurred, and since then their lives had flowed on

uneventfully. A son had been born to them, and old Doctor

Leighton had died rather suddenly.

After that the chief incidents within their home had been

such as little Spencer cutting his first tooth, little Spencer going

into trousers, or little Spencer falling sick of the measles.

Then followed the boy's going to school and his troubles and

successes there, and now he was about to go into the larger world of

college. His father was to take him up to Cambridge and enter

him at Trinity.

So young Spencer Hook was entered of Trinity College, along

with Charles Dunscombe, Doctor Dunscombe's eldest son. These

two had been at school together at a small grammar-school in the

neighbourhood, whose only advantage was that it allowed them to be

much at home, the lads generally spending the Sunday with their

families. The two boys had been companions without being

friends. Spencer had indeed the greatest contempt for Charles

Dunscombe and his sneaking ways, but their comings and goings threw

them together, and though their bickerings were ceaseless, they

still continued to associate with each other. Charles was a

large, lymphatic lad, selfish and sensual, but not deficient in

brain, for with only the advantage of a year in age, he had managed

to keep pace with the brilliant Spencer.

At college they were thrown together again, and got on rather

better, owing to Charles's decided ability; but Charles got into a

bad set and Spencer with him, and the animal propensities of the

former speedily developed. He became one of the worst young

men of the day, steadily and soberly vicious. He drank a great

deal, but was never drunk. He indulged himself in every

possible way, and yet made his allowance cover all his indulgences.

And he tempted others to become ten times worse than himself.

On his equally liberal allowance, Spencer got into debt, and

made his father excessively angry, not because of the money, which

he could well enough afford to lose, but of what it indicated.

Cigars and wine and even brandy, it went sorely against Doctor

Hook's grain to pay for, and he said he would never on any account

pay for them again.

Nevertheless he had to pay for them. Spencer when he

finally left the university left it in debt, but he left it also

with honours, and his father once more set him free from

embarrassment, though not without heart burning and bitterness.

His son's youth appeared to him to be about to repeat his own, and

he knew how narrowly he had escaped an utter shipwreck. He

doubted, too, if any influence could be brought to bear upon his son

as strong as that which had met himself at the turning-point of his

career and saved him.

And he kept him therefore jealously under his eye.

Doctor and Mrs. Hook had never cultivated society. Martia did

not care for it, and the Doctor's social sympathies, which were

particularly strong, were abundantly satisfied in the course of his

professional duty. His son's, which were equally strong, were

not satisfied at all. He had to fall back on young Dunscombe,

who had returned to his father's house on a footing precisely

similar to his own, namely, to be his father's present assistant and

future successor. The two young men took their degrees

together, and were introduced together into the sphere of their

future labours. Each was provided with a riding horse, and

they were constantly to be found riding in the same direction,

though their work could hardly have lain there with anything like

frequency. The worst of it was that they had little or no work

to do, and what they did was but nominal, not real, responsible

work. Their fathers both were in the vigour of life, and

declined to give up. Then a great cloud of misery fell upon

the Hooks. Spencer had unmistakably wandered into evil ways.

There were dinners laid for three, at which only two were present,

and where all the talk that passed between the Doctor and his wife

were the merest formalities of the occasion, because before the

servants they could not speak of the subject nearest to their

hearts. There were nights, too, when the servants were sent to

bed, and the unhappy father and mother watched and waited for their

prodigal son.

How could they influence him, when all the pleadings of

affection had failed? They had pleaded with him each of them

alone and they had pleaded with him together, and he had faithlessly

promised an amendment, which never ensued. Latterly he had

been altogether mute.

One evening the Doctor and his wife sat together in the

drawing-room, waiting for Spencer, when the clock on the

mantle-shelf struck twelve. The Doctor looked up from the last

page of the British Medical Journal, which he had read

through, and waited silently till the last silvery stroke had

ceased. Then he looked at his wife, and said, firmly, "Martia,

let us go upstairs."

She rose, with a heavy sigh, the still beautiful woman whose

lightest wish had been a law to the man before her, and took up her

key-basket, a little straw toy, lined with satin of her favourite

plum colour. She was evidently reluctant to go, and she

gathered up likewise some bits of feminine work, with which she had

been trying to occupy herself, and paused.

The Doctor lit the candles, and handed her one, and she moved

away slowly, leaving him to turn off the gas. He went the

round of the house, and even across the yard to the coach-house and

stable, to see that all was secure before he joined her in her

dressing-room, where he found her sitting, without having made the

slightest preparation for the night. He advanced, and set down

his candle beside her's, with stern set lips and knitted brows.

A mirror had showed him Martia with her woeful and weary looks, and

his heart was set against his son.

Doctor Hook had come to a resolution, and had announced it to

his son in the presence of his wife. It was that if he kept

them waiting for him once more till beyond midnight he should find

his father's door shut against him.

"You have not undressed, dear," said Doctor Hook, in as free

a voice as he could command.

"No," murmured Martia. "I think he will come soon, and

you will let him in this once more, Spencer?"

"The hour is past," said Doctor Hook, "at which I told him he

should find my house doors shut against him."

"Just this once," said Martia, and she was the firmest of the

two by nature.

He was the softest. Yes; but has the reader ever had

any experience of the hardness of a soft nature? If so, he or

she will bear out the assertion that it is the most immovable of all

hardness.

"Martia," he replied, "when had you ever need to ask me twice

for anything that was mine to give? This is not mine. My

word has gone from me, and I cannot take it back. I have done

it once too often. He thinks he can play with me, and

transgress with impunity the rules I lay down."

"It is such a cold night, Spencer," said the night, "It would

be hard to keep him out to night. The river is frozen over."

"Martia, have I ever been hard to you? I have loved you

more than son or daughter, more than self, God knows."

"Yes, yes, my husband. You have been so good to me, so

good and kind," said Martia. "I shall never forget how tender

you were of me when our Spencer was born, and I went down to the

gates of death for that one precious life, and how you loved the

little one!"

The words were natural—came naturally to her lips; but they

were cunningly cruel, cruelly cunning, in their power at that

moment.

Dr. Hook shivered where he stood, but he answered not a word.

"My child, my child," she moaned. "To think of his

being shut out to-night."

"Martia!" said her husband, upbraidingly, "you unman me.

I cannot think of what has been, but of what is. The boy's

flesh has been too dear to us, and his soul has suffered. We

have hidden his faults from our very selves. We have come

between him and their punishment, and he has grown insolent,

disobedient, hardhearted. Yes, Martia, his heart is hard, hard

as the nether mill-stone. He has his hands upon both our

heart-strings, and he wrings them to torture. Night after

night you sit and watch for him, and sigh so wearily, and look so

worn, that I cannot bear to see you. And what is he doing

while we are suffering?—laughing at some feast of fools. I

never was hard like that. It was because I had no mother that

I went astray. Do you think I would have done it with such a

one as you?"

"I do not know," she answered wearily.

The Doctor waited again for a few minutes—they seemed hours

to Martia.

"Come away and let us put the lights out," he said at last,

He had scarcely finished speaking, when a horse galloped up

the street, some one dismounted, and a loud knock sounded at the

door. Then the scene in that room became tragedy of the

suppressed modern sort, but none the less tragedy in all its pity

and terror.

"That is his knock," said Martia.

Doctor Hook only moved a little further from the door.

He was silent.

"Let me go to him," said the mother, faintly.

No response came from her husband's lips. He took up

the extinguisher, and put out one of the candles."

Another knock, longer and louder than the last.

"I must go to him," cried Martia, wringing her hands

together. "Spencer, say I may?"

"No," he answered, firmly.

"Spencer, I am going," she whispered hoarsely.

He seized her by the wrist and held her fast. "Let me

go," she cried; "by all that I have suffered, let me go. If

you ever loved me, let me go, Spencer."

He held her fast.

"You are hard, hard, hard," she said fiercely.

"Hush, wife," he answered; "your words are wounds. They

are making me as faint as if the blood were welling from my veins.

But you shall not open to him, for your act is mine, and he will

despise us both. I think it will harm him less to be out a

night in the cold than to find that our words are worthless."

Another knock.

And hardly knowing what she did, Martia clung to her husband

for a moment.

"Be calm, dear wife, be calm," he murmured over her, for she

trembled violently.

Then all at once she started back from him, crying, "He is

gone!"

A horse's hoofs were echoing down the street. The drops

as of a mortal combat stood on the Doctor's forehead.

Then Martia's passion found vent, as she stood before her

husband, and both were conscious of that strange disembodiment which

they had felt once before; but now their spirits met in wrath and

not in love.

"My son! my son!" she cried; "where will he find

shelter—driven from the roof which should have been free to him,

free as the skies above us? A father should forgive, as God

forgives."

"And He," replied her husband, reverently, "forgives and

chastens."

Doctor Hook was by nature reverent, and in his misery there

came to him a remembrance of the God whom he had forgotten.

Had Martia gone mad? "No, I cannot bear it," she cried

wildly. "I must follow him. I must go!"

Was it a presentiment? She felt as if the night would

kill him. Something in the cold, cruel darkness seemed to her

waiting to devour him, and she could not stay. To her

husband's terror and amazement she threw on a shawl and bonnet in a

moment.

"Martia, are you mad?" he said. "Come back," for she

moved towards the door.

"I will never come back, unless I bring him with me," she

answered, and was gone.

He did not think it well to follow and to restrain her by

force. She would come to her senses presently. But what

a blow she had given him. He almost reeled into the chair in

which he had found her seated when he came upstairs. "Has it

come to this?" he murmured; "after all the love of a lifetime, has

it come to this?"

"She will turn again," he thought. But she had taken

the keys and unlocked the door. He heard the bolts drawn, and

started up. Then the door closed, and she was out in the

streets.

Still he did not follow. Though he could hardly realize

that the fierce, passionate woman who had stood before him a few

minutes ago, so stern and grey, was his own Martia; still he trusted

in her. We all trust in each other to act quite mildly and

sanely, till some whirlwind of passion strews the wrecks of our

confidence before our eyes.

As Doctor Hook sat there, he seemed to remember, with

unnatural vividness, every separate day of the three-and-twenty

years he had been united to Martia, and every day of all those years

seemed to have a separate dearness. These two had grown so

one, that the same thought often rose in both their hearts, and met

in the same words upon their lips. And yet it had come to

this!

CHAPTER III.

WHEN Martia went

out into the street it was already silent and empty. She

thought she could hear a faint echo of horse-hoofs in the distance,

and that was all. A little sobered by the fresh air and the

freedom, she walked rapidly along, but as yet without a purpose,

driven only by her inward violence of grief and love in conflict.

She was outwardly restrained; but she would fain have uttered

such a frantic cry as would have wakened all those windows sleeping

in the white moonshine. At the end of the long street where

the road divided, and both the ways led out into the open country,

she was forced to pause and reflect. The two ways, like those

which meet us into every turn in life, asked their silent question,

gave out their unescapeable "Choose!" and brought Martia still more

to her senses. She deliberated. Spencer would not ride

all night; he would stop somewhere. She would follow him—track

him, if possible, even through the darkness. Two young men

came up just then. They walked with unsteady steps,

intoxicated doubtless, and making their way home to their lodgings

in the town, most likely from some inn by the roadside.

"Leave her alone," she heard one say to the other.

"She's an old woman, Bill."

But Martia Hook, the delicately brought up and

tenderly-guarded woman, was at that moment impervious to insult and

beyond the reach of fear.

She stopped them and asked if they knew which way a horseman

had passed.

One could not say. The other pointed to the road which

led down to the river. Then they passed on, singing a tipsy

glee about not going home till morning, which sounded horrible and

unholy in the saintly night.

Martia took the road pointed out to her. The frosty

stars seemed staring at her with their numberless, pitiless eyes.

The moon—she had never liked the moon, it was a peculiarity of

hers—seemed mocking her with a grin of its death's-head face.

Yonder was the river, but its shine was deadened by the frost which

bound it. It gave out only a dim gleam in the moonlight.

No bridge crossed the river there; but only a ferry, and an

old-fashioned inn stood by the nearer bank. The towing path

ran in front of it—between it and the water. And the horses

stopped there, and the bargemen drank, as also did the carters

passing to the mill on the stream beyond, and the townspeople on

their holidays or evening rambles. They sold good cider at the

little inn. It had upper chambers, too, which were let in

summer-time as country lodgings, and the traveller could always find

there a clean if homely bed and a supper of trout or grayling.

"Perhaps Spencer has stopped there, and put up his horse for

the night," thought Martia, while still at a distance. It was

not unlikely. As she drew nearer, there were lights flitting

about, lights and a clamour of voices. At any rate, here she

might ascertain something concerning him; and if she should find him

there, and bring him back, and they two return together, her husband

would not refuse to let them in, and there would be peace. The

old love was tugging at Martia's heart—the love that was before this

young man had lived, and had sufficed if he had never been.

She went forward to the river's brink, and for a moment

failed to realise the meaning of the scene before her.

A horse was being led up to the inn. She did not notice

that it was dripping, panting, trembling. Only it seemed lame,

and two men were leading it. Another man and two women half

dressed, with shawls about them, were by the river's brink.

The man held a lantern, and leant over the edge of a boat which lay

upon the ice. He was looking by its light into a great hole in

the frozen river.

The man looked up at the new comer, and seemed paralysed with

awe. He knew her; he had known the horse, and he guessed who

the rider must have been who had gone down there into the darkness.

Rather, he had guessed before, and now he knew it must be so.

The mistress of the inn and her maid also recognised Mrs. Hook, and

began weeping loudly.

"What has happened?" asked Martia.

"He has gone under the ice, and we can do no more," answered

the man.

"Who?"

There was no answer. None was needed. The whole

truth flashed in an instant upon the miserable mother. It was

her son's horse she had seen led up the bank. It was her son

who had gone down to death under the icy water, and with a great cry

Martia fell upon the earth like one dead.

This was what had happened. Spencer had found that his

father was determined to carry out his threat, which he had

seemingly presumed to think an utterly childish one, and he could

see a faint glimmer of the light in his mother's room before he

applied himself to the door. When it was not opened to him as

he had expected, and he saw that he was wilfully detained outside,

he had remounted and ridden away.

He rode along the very road which his mother had followed

later, but with no intention of stopping at the roadside inn.

His intention was evidently to cross the river, and go out into the

open country beyond, though whither no one knew. The country

was studded with farmhouses and the seats of the smaller gentry, at

many of which Spencer was known. He had, in fact, as was

afterwards ascertained, just come home in that direction, and walked

his horse over the ice to boot; but in returning it is supposed he

sprang on it recklessly, without dismounting, or the insidious thaw,

which had already began, had thinned the ice at that particular

spot, for there was a crash and a great cry. The innkeeper and

the ostler, who had not yet gone to bed, heard it, and ran out to

find a man on horseback struggling in the water, where the ice had

given way. As they drew near, the man had jumped off the

horse, and with another lesser crash, and with no cry whatever, had

disappeared.

The men had used the most frantic exertions. Their

shouts had brought out every inmate of the inn—the mistress and her

servant and the one traveller who chanced to be sleeping there that

night. The women held the lights. The men with the oars

of the ferry-boat broke the ice in a wider circle, and drew out

great wedges that the drowning man might rise to the surface.

For the same purpose they got out, with great effort, the terrified

and unmanageable horse, and left him on the bank. They pushed

the boat upon the ice, and leaned over it to catch the rider the

moment he appeared; but they looked in vain. Minute after

minute passed, and he did not appear. Minute after minute, and

the time passed when it was possible for him to appear as a living

man again.

They now carried Martia in her insensibility into the inn and

sent for Doctor Hook, and he came and remained all night with his

wife, watching over her terrible return to consciousness, and

directing still further efforts for the recovery of the body of

their son. These proved unavailing, and it was only after some

days, when every vestige of ice had disappeared, that it was found,

fearfully disfigured, floating in a little rushy cove several miles

below.

During all this time Doctor Hook bore himself like a brave

man, though he was deeply changed. But for Martia—she was

altered out of knowledge. The Doctor, indeed, had trembled for

her reason or her life—one or other, he thought, would go.

Perhaps that had something to do with the control which he evidently

kept over his own sorrow. But she did not die, and her reason

kept its seat. She lived and suffered. Before that

terrible night, Martia would never have been called old. She

was old when she rose again from her sick bed. Her hair had

not turned grey, she was as erect as ever, but her whole colouring

had changed, to her very lips and eyes. It was completely

washed out, and turned to an ashen greyness.

When the body was found, her husband felt that it was

necessary to tell her, though he shrank from the task more than he

would have shrank from the operator's knife, if it had been to cut

off his right hand. He shrank to open her fearful wound, for

they had never once spoken together of their great sorrow. The

old confidence, the old communion of spirit, was at an end between

them, and that, too, when both needed it most to make life seem

bearable. And yet he knew she must be told. He knew she

must have the option of looking upon that dreadful thing which was

once her son. Would her reproaches burst forth upon him then?

and the man believed that he would bear that they should kill him

rather than that she should pass through another agony.

He told her in the twilight, as she lay on the sofa in the

darkened drawing-room. She could not see the working of his

face, and his voice was like the voice of a man who has been long

time sick. "Martia, Spencer has been found," he said; and,

after a pause, "where would you have him buried?"

She shook her head, expressive of the small matter it was to

her where they laid him.

"You will not see him, Martia," he rejoined, in the same

tone.

She acquiesced at once. She does not care, she will

care for nothing more, thought her husband, as he left her presence

to make the melancholy preparations. But he did her an

injustice. She cared for him. Through her own sufferings

and by her old perfect sympathy, she divined what his must be.

Like a tide that has been back far over dismal rocks, the old love

was sweeping in, filling all the recesses of her nature.

Martia was an eminently sane person, though she was capable

on occasions of acting on a sudden impulse. Her impulses had

always something of reason in them, if indeed they were not the

highest reason. She abstained from looking at the remains of

her son, not only from a natural shrinking, but that she knew that

her horror and anguish would redouble his. And yet she could

not draw near to him, and tell him this. That night lay

between them like a wrong. Uncheered by the only sympathy

which was worth anything to him, Doctor Hook went through the ordeal

of burying his murdered son.

Murdered! Yes, that was the terrible thought which laid

hold of the overwrought, sensitive brain of the man. He had

murdered his boy, and sent him unprepared to his account with God.

It was not till after their lives had been established in

their ordinary routine once more that the change which had been

wrought in Doctor Hook became apparent. He had no longer the

clear steady head he used to have, nor the fine genial temper.

He was shaky and irritable; not the latter at home though. To

Martia he was full of the tenderest consideration. But his

patients, and they were more or less like his friends or his

children, began to notice in his speech and behaviour something

which had not been there before, something of uncertainty and

indecision "Can the Doctor be drinking again?" was whispered at

length by one member of a family to another.

They feared it was so, and, thinking of the great calamity

which had come upon him, some among them, who knew not the stay of

the mourner, were fain to say, "No wonder."

Yes, the Doctor was drinking. He had never given up his

glass of wine at home; indeed latterly, before this trouble, he had

indulged in it freely, though without excess. The

strenuousness of his self-control had gradually relapsed. He

had passed the time of life, he thought, when he could relapse into

his one vice. He held that he had fairly conquered it—that the

"taint of blood" had, in process of tune, been eradicated

entirely—that he was free.

But in the prosperous and happy years which had gone by there

had been no strain upon him. He had been in no temptation.

All at once the temptation had come, sudden and strong, and had

found him unarmed to meet it. His wife never came down to

dinner now. She had little appetite, and eat what she could

eat in the earlier part of the day, taking a cup of tea in the

drawing-room, while he took his dinner in the dining-room below.

Then perhaps he had his horse out and drove away to visit some

patient, and Martia would be in bed before his return, and he would

go into the study for an hour or two before coming up to her, and

all the while he was struggling to throw off the nightmare of

self-accusation which tortured him, and he was left thus to struggle

unaided and alone. At last Martia stumbled upon the dreadful

truth, and it roused her as nothing else had had the power to do.

One day she resolved to go down to dinner with him and encounter

that tête-à-tête which must be agonizing, as everything that

had to be done by these two alone which they had formerly done in

the presence and with the companionship of their son was agonizing;

but the very thought of it brought on one of the dreadful headaches

to which she had been subject ever since that fatal night.

Prostrate and nearly blind with pain, she had to lie on the sofa.

Before dinner her husband came to her, bathed her temples, held the

cup out of which she drank a little tea, laid her easily on a

pillow, and screened her from the fire. In short he did all

that the tenderest heart and the kindest hand could do to ease her.

Then he left her in the half-darkened room and betook himself to his

solitary dinner.

But he could not eat. The first morsel seemed to choke

him. To see her suffer was driving him mad. He swallowed

a glass of wine, and again tried to eat. But in vain. At

length the almost untasted meal was removed, and the Doctor

swallowed another and yet another glass.

At length he rose from the table, and laid hold of a more

potent spirit. He took out a bottle of brandy, and helped

himself with reckless freedom. He had lost the power to act;

very soon he had lost the will also. And there he sat, hour

after hour, drinking and staring, and sometimes weeping. The

servants, mostly old and trusted, consulted in the kitchen on the

possibility of stopping the mischief. They had seen it, of

course, before any one else; and they had, to their honour, kept it

to themselves religiously. The Doctor's man, unbidden, took

him in coffee, but was silently dismissed.

Martia had been asleep. Two or three hours of rest in

the quiet and the healing darkness, had lightened, almost banished,

her headache. She looked at the time-piece. It was ten

o'clock. Should she go upstairs to bed? After her

refreshing sleep, she hardly felt ready for this. She wondered

if the Doctor had gone out, or if she would find him in his study.

She would go and see.

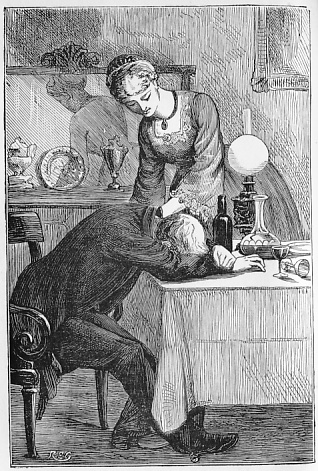

"His arms were spread out on the table before him,

and his head laid upon his arms."

She went accordingly, peeping in at the study door, where all

was darkness. She next stepped across to the dining-room,

hardly hoping to find him there. And yet there he was.

His arms were spread out on the table before him, and his head laid

upon his arms. Was he asleep?

She went up to him, and touched him gently, and at her touch

he looked up, but with such a look—dazed, insensate, brutified.

When he saw her, he began crying, foolishly and childishly, aloud—a

pitiful spectacle. The whole truth was laid bare before her at

a glance. He was hopelessly intoxicated!

Martia had saved him once; could she save him yet again?

She would try. The fire was out. There was only ashes on

the hearth, and it was cold; but she stayed beside him. If

possible, she alone should see the depth of his degradation.

She took away the wine and spirits from before him, and locked them

in the sideboard. Then she sat down to wait till he should be

partially sober. She managed to drag him into the library,

where a fire was still burning, and to lay him down on a sofa there.

Then she sent the household to bed, and, when he had slept for some

time, she helped him upstairs to his own room.

He woke in the morning oblivious of the greater part of the

past night, but distressed and wretched concerning what he could

remember. And yet, even before breakfast, unable to resist the

craving for a stimulant, he went and took some brandy. The

Doctor's downward career seemed likely to be very rapid indeed.

But that evening Martia came down to dinner for the first

time since their bereavement. Her husband had been drinking

already, and the craving for more was upon him in full force.

Before he touched anything, he asked apologetically for some brandy.

The man set it on the table, and he helped himself. The

servant then went out of the room for a minute, and, to the Doctor's

amazement, Martia came over and took the bottle, and pouring out a

full glass of the fiery fluid, swallowed it in a moment.

"Are you ill?" he asked, in concern.

"No," she answered, simply, and was seated before the servant

re-entered.

Again the Doctor hardly touched the food set before him.

Drink was what he desired, with a fierce and burning desire; but

during dinner he took but little—a single glass of sherry, which he

noticed Martia take likewise. From time to time he glanced

uneasily at his wife. She ate. The brandy had given her

a false appetite. Her colour had returned—that is to say,

there was a flush upon her cheeks, and a brightness in here eyes,

which had not been there for many a day; but it was a strange,

ghastly flush and brightness. The servant looked on in

astonishment. His mistress was looking suddenly like herself

again, only a bit excited," he reported downstairs. The veins

on her forehead and hands were swollen. The brandy and wine

were taking effect on her extremely temperate habit; yet she kept

possession of her faculties, and did not lose her self-control in

the very least.

The dinner over, she did not leave the table, on which a

slight dessert had been laid. The Doctor poured himself out,

almost mechanically, a glass of wine. Two decanters, full,

were on the table. Martia reached over and took the other and

did the same. What could it mean?

"Let us go upstairs," said the Doctor, leaving his wine

untasted.

Martia assented, and went, leaving her's also. To her

husband's horror, she reeled as she left her chair, and he had to

assist her up to the drawing-room. There he rang for tea, and

told the servant that his mistress felt her head ache. He had

put down the lights, that he might not see her flushed face and

strange aspect.

The Doctor did not go out that evening. He sat in the

drawing-room, beside his wife, full of the strangest apprehensions.

But through all the desire was tormenting him. At length, when

an hour or two had passed, he stole downstairs, and entered the

dining-room. He poured out and drank another glass of brandy.

When he turned, Martia stood behind him. She had risen and

softly followed him. Almost in fear of her, he laid down the

bottle, and she seized it at once and began to pour out another.

"Martia!" he exclaimed, in horror, "you do not like it."

"I loathe it," she said, shudderingly.

"Then why do you take it?" he asked.

"Because you take it," she answered.

Yes, certainly, Martia was going mad. She stood holding

the brimming glass.

"I loathe it," she repeated, "loathe it like drinking blood;

but I will drink glass for glass with you. I will go step by

step with you down the road of ruin," and before he could prevent

her she had swallowed the whole.

He hurried her upstairs before the spirit should take effect,

and got her into bed; but he did not leave her again that night,

though a little later he might have done so with perfect impunity.

He sat by her, and watched the uneasy slumber—the restlessness, the

moaning, the sickness—all the poisoning symptoms of inebriation.

Had she saved him? I think not, and yet he was saved

though as by fire. All night long he wrestled, as Jacob

wrestled with the angel, seeking no longer the mere outward

reformation of the life, but the inward regeneration of the spirit.

He no longer desired to subdue the sin which had power over him

because of its bitter fruit of suffering. He saw what it seems

hard for the refined and educated men of our day to see, unless

embodied before them in the coarse and foul deeds of the dregs of

society—the exceeding sinfulness of sin. He cried out, not,

who shall deliver me from this tyrannous vice, but, who shall

deliver me from the body of this death? "I amended my life

once," he said within himself, "and it has been like the new cloth

on the old garment. At the first strain it has given way, and

the rent is made worse."

Doctor Hook came out of that sorrowful vigil another man—no

longer trusting in his own strength or in his own righteousness, but

clothed with the righteousness which is of Christ.

When Martia woke to consciousness, her husband was still by

her side, watching over her with a worn and sorrowful look, which

had yet something quite new of hope and elevation in it.

Surely he had not been sitting there all night, and into the grey

dawn of a winter morning? She tried to speak, but was too sick

and wretched, and only made a moan. He soothed her, and

ringing for a servant to bring her a cup of tea, left her in the

woman's hands.

He had work to do which must be done, and he went about it

earnestly while Martia lay thinking how her plan had failed, and

must fail from its inherent weakness, that is to say, long before

her husband had begun to feel the effects of the poison, she would

have succumbed to its influence entirely. But she rose and

dressed, and was ready to go down to dinner with him, and repeat the

scene of the previous night if need were—nay, she would go on

repeating it every night of her life. This woman had a

tenacity of purpose which nothing could defeat.

The Doctor came home early, and joined his wife by the

firelight in their drawing-room. Martia's shaken nerves were

in a tumult. As she looked at the strong, noble face, so grave

and sad, and yet so kind, she burst into hysterical weeping.

"We are the two most wretched creatures in all God's world,"

she cried.

"Yes, Martia; but it is God's world, and not the devil's, and

not ours. It is His who makes all things new. We had

never been so wretched if we had sought His renewing grace. It

is not yet too late."

But Martia burst into still bitterer weeping. What of

her son, her only one—was it not too late for him?

As if he divined her thoughts, he spoke of him and prayed her

to leave him in the hands of Him who was the Eternal Father, wiser

and tenderer than any earthly parent.

In the days that came after, when they could bear to talk of

it, they took up the sorrowful theme again, and found that each had

the hope that the young man on that particular night had not been

drinking, but had been in a right mind even for momentary

repentance, and on this point they were yet to be satisfied.

CHAPTER IV.

SEVEN miles

across the country, at the distance of an easy ride, stood up a

range of little hills, and at the foot of one of them lay a large

dairy farm. The house was very lonely, and travellers often

stopped there for refreshment, leaving behind some little present in

money for the servant, as no charge was made by the hospitable

master. It was a long low house, very old and picturesque,

crossed by great black beams without and containing within traces of

former grandeur in the spacious hall and lofty fire-place.

Around it was a terraced garden, not a fashionable garden, but sweet

in the sunshine, with bushes of southern wood and great beds of

purple thyme, masses of dewy lilies and clusters of scented roses

and clove carnations. Roses and honeysuckles crept over the

whole long front and round the ends of the house. In the

centre was a wide doorway, which led straight into what had been a

hall, a great stone-paved, beam-roofed apartment, which was kitchen,

reception-room, and sitting-room, in one.

All the dishes and covers were arrayed there. All the

hams and flitches hung there. The cooking and baking and

sewing went on in it and most of the life of the house. To the

right a door opened into the parlour, a room half the size.

You went up a single step to it, and found it carpeted and curtained

and furnished with stuffed chairs and a piano, Miss Bessie Hope's

private property. Into this the more privileged guests were

led, when they had the benefit of Miss Bessie's company to boot.

Bessie was the farmer's only daughter, and spoilt youngest

child. He had sons besides, but they were married and away

from him, and had been for years.

Bessie was a dainty little lady in muslins and lace, with

hands that were white and slim fingering her music. Bessie's

mother wore an apron, and her hands were thick and fluffy from much

making of pastry and handling of butter and cheese.

The other half of the long house, the length of hall,

kitchen, parlour, and all, was dairy. It was shaded from the

sun at that end by a grove of trees, and kept as sunless and cool as

a cellar. The milk of sixty cows, feeding all round on the

rich meadows and lying under their bordering elms, poured into it in

frothy streams every day. The milk of sixty cows went all at

once into the huge tub, to be mixed with rennet and turned into the

curd of a single cheese, while the whey was poured out again into

the long troughs at which fed an equal number of swine, black and

white spotted, but all sweet and clean, in the yard behind.

Above the dairy was the cheese room, which held a cheese for every

day in the year. And every cheese was turned in its place

every day, so that there was work enough on the farm. Mr. Hope

had a man and a lad to milk and to muck the byre, which stood at a

little distance, and to feed the beasts. Mrs. Hope had her

maid to scour and clean beneath her watchful eye; but Bessie gave no

help and was asked for none, not that she was selfish or unwilling.

She only did what she was set to do—mindless as the china

shepherdess which stood on her parlour mantle-shelf.

When the cows were driven into the yard for milking, with

much clamour and shouting—much more than seemed in the least

necessary with the sleek, quiet beasts—and all the invaded pigs

squealing and grunting in concert, Mr Hope, a big man with almost

purple red face, came forth in his white, elaborately stitched

frock, with his three-legged stool in his hand, followed by his two

satellites and by the servant-maid, who had to assist in the great

operation, all carrying their stools, but Bessie sat still in her

parlour at the other end of the house and entertained the strangers,

if there were any.

In this way Bessie had often entertained Charles Dunscombe

and Spencer Hook on their botanical excursions. Either the

flora of the district must have been unusually rich, or the youthful

botanists must have been unusually exhaustive in their treatment,

from the number of times they appeared there with those tin boxes on

their backs. But Mr. Hope knew the fathers of both. He

was a patient of neither, for the good reason that he had never been

a patient of anybody's in the whole course of his life. He

knew them by repute however, and he made their sons welcome, and

never took it into his bovine head that they came just a little too

often.

They came and chattered with Bessie in the parlour, or

loitered with her under the elms, always the two together. "It

would be different if there was only one," thought the mother,

allowing it all; "but there can be no harm in the three being

together; and Bessie is so lonely. She is not the least like a

child of mine," she added to herself, with secret pride.

"Bessie should have been a lady; perhaps she will be one some of

these days." Whether Bessie was not in the least like her

mother it was impossible to say, for it was impossible to say what

her mother had been like in the general obliteration of feature and

shape which had taken place in that excellent matron. But

Bessie was very slim and very pretty and had a childish softness of

mind which gave to her pretty face an expression of utter innocence.

Nobody had been near the farm for the space of an entire

month; but, then, it was winter, and though the roads were good in

the hard snowless frost, there was nothing to bring anybody there.

True, young Dunscombe and Hook would drop in when they were riding

that way, even though the botanical excuse had worn itself out, but

there might be nothing to bring them that way. Bessie was very

dull; she had a pony now, and rode; it was doing her good her mother

thought, for she had not been well lately, and for the last few days

she had not been out at all. She sat in the parlour working

and doing something which she did not wish to be seen, for on the

least noise, indicating the approach of any one, she hid her work in

a little drawer, which she kept half-open in the table at which she

sat. It might be some Christmas present she was at work upon,

intended as a pleasant surprise to father or mother.

She was sitting thus when her ear caught the sound of a

horse's hoofs in the distance, and she started up and stood leaning

against the casement. From where she stood, though she could

not see any one advancing up the road, she could catch the first

glimpse of any comer on the path which led to the house. Her

eager breath dimmed the frosty pane, and she took out her

handkerchief and wiped it. The rider came nearer and nearer,

at length he turned from the road into the pathway, and she caught a

glimpse of him. It was Charles Dunscombe. She sighed and

dropped into the chair again, looking disappointed and dull.

All the eager light had faded from her face at once, and you could

see that she was out of health and nervous and spiritless.

Charles Dunscombe alighted on the terrace and came into the

house. He was welcomed both by the farmer and his wife; they

asked him to sit down or step into the parlour. It was the

most leisurely time of their day, in the afternoon, before the

evening milking. But there was something unusual about the

young man. He had not come in in the ordinary way, which was

after standing as long as possible with Bessie at the parlour

window. Where was Bessie, that he had not seen her nor she

him? He would neither sit down nor go into the next room, and

his face was very grave. At length the truth came out.

"You don't know, I suppose," he said, with a good deal of feeling,

"that young Hook is dead!"

"Dead! God help us!" exclaimed the farmer, loudly.

"What did he die of?"

"It was an accident. He was drowned."

"And such a fine handsome man," said Mrs. Hope, putting her

apron to her eyes.

"How did it happen?" asked the farmer.

Charles Dunscombe repeated the details shortly. "I was

riding near," he said, "and I thought you would like to know."

"Won't our Bessie be grieved about him," said her mother,

tearfully; "and what a thing for his poor family!"

Charles Dunscombe could not stay to hear their lamentations

over his companion's fate. He pleaded that he was in haste,

and would come back another day if they would allow him. He

had no intention of staying on this occasion, which was extremely

distasteful to him, but he wanted to be able to come in future, when

this should be forgotten. He bade the honest couple good day,

and mounted his horse and rode off at a rapid pace.

"What can Bessie be about?" said the mother. "I don't

like to tell her the news. She'll take it ill, I fear."

"She must know some time," said the father. "And the young

man, after all, was nothing to her."

So Mr. Hope went out upon his work, thinking reflectively on

the uncertainty of life, but by no means ill at ease.

Mrs. Hope was ill at ease. She had a kind of half

conviction that her daughter had cared for one of these young

gentlemen, and that the one she had cared for was Spencer Hook.

So, after sitting a little time to recover her composure, she went

in search of Bessie. She did not expect to find her in the

parlour, but the door which led by a ladder staircase to the

bedrooms above was in there—the proper staircase for the floor

opening into the cheese room, and the communication being closed.

Mrs. Hope opened the parlour door and pushed, but something lay

against it; something heavy, like a basket of clothes, had been set

down there by that thoughtless Bessie. Mrs. Hope pushed

harder, and at length got in her head. What was her terror to

find that it was Bessie herself lying in a heap on the floor!

By a wonderful effort, in which she nearly squeezed herself to

death, Mrs. Hope got herself into the room, and shut the door, and

knelt beside the prostrate figure. That Bessie had been

listening there, she was quick enough to know, and that it was the

fate of Spencer Hook which had affected her so severely there was

little doubt. Mrs. Hope threw open the parlour window, drew

her daughter into the middle of the floor, and in doing so made

another discovery, before which she lost er presence of mind

entirely.

In Bessie's hand was a little garment, which she had

neglected to put into the drawer as usual, if the fact had not

otherwise been plain to the mother's eyes. Instead of doing

anything to help her daughter, Mrs. Hope wept and wrung her hands

and wailed, "Her father will kill her, when he knows. Oh, her

father will kill her."

And Mrs. Hope had cause for her fear. The choleric man

was mild as a cow on most occasions, but he was subject to fits of

temper which made him a perfect madman. There had been more

than one almost tragical scene enacted in that homely house.

Father and son had come to blows there, which might have stained its

hearth with murder, and one son was yet a wanderer and an outcast

from his home because of it.

Mr. Hope indeed knew his failing, and tried to guard against

it. He had even gone to his clergyman and confessed it and

asked advice, and he had been told that nothing less than the

renewing of his whole nature would save him from it. But he

had gone on in his old ways, guarding himself as he best could

against its consequences, by rushing away from temptation and

behaving not very unlike one of his own bulls when it raved round

the pasture in a fit of passion. He had been known to run away

from his own servant for fear he should kill him for some slight

offence.

And now, passing by the parlour window, as he retraced his

steps along the terrace, he heard his wife weeping and wailing, and

looking in beheld his daughter lying senseless on the floor.

He entered immediately, half angry already that Bessie should

be making a fool of herself, as he concluded in his own mind she was

doing, about a young man who was nothing to her.

"What's ado?" he cried in the parlour doorway, in no gentle

voice.

He was not answered, but he took in the situation at one

glance.

Bessie was coming to herself now. She sat up with her

elbow on the floor, to see her father literally glaring over her.

He could not speak with the tide of fury which choked him.

The girl rose and stood helpless and drooping before him.

He clenched his fist as if to strike.

"Oh, don't hurt her, don't hurt Bessie," cried the mother,

attempting to come between them.

Her husband pushed her aside. His speechless rage was

more terrible than any amount of abuse. He went up to Bessie

and shook her violently.

"I am married, father," she pleaded, holding up her hands.

But he would not hear. With one terrible word he flung her

from him, and fled out of the house.

"Father has killed me," said the girl, when she could speak,

holding her hand to her side. She had pitched against the

table, and felt a great pain where she had struck it, a pain which

never left her.

"But, Bessie, are you really married?" gasped her mother.

"Yes, I am married, and he is dead," she answered in

heart-breaking accents.

"Why didn't you tell us? It was wrong not to tell us,

Bessie," said Mrs. Hope.

"I was frightened," she answered, "and Spencer said he would

tell you himself He wanted to tell his own father first."

"But you're sure you're married?" reiterated Mrs. Hope.