|

[Previous Page]

LEAVEN.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

THE Haycrafts had

prospered in the world, so everybody said; and certainly they

deserved to prosper in the world, for their devotion to it was

unlimited. But if the reward had been great, so also had been

the toil and trouble which had secured it. There were those

who remembered them as quite poor people, Mr. Haycraft only a

managing clerk in a City firm, Mrs. Haycraft cooking her own dinner,

while the servant went out with the children, not because the dinner

required the most attention, but because nobody was supposed to know

that she was drudging in her little kitchen, and all the world would

be certain to see her carrying a baby.

All this was long ago, however; so long ago that Mrs.

Haycraft had certainly forgotten it, though some people had stronger

memories. Mr. Haycraft had gone into business on his own

account, and succeeded; so everybody said. He may have known

the proverb, "Nothing succeeds like success," or he may not: he

certainly acted upon it. He believed that success, to be real,

must be apparent, and he therefore made success apparent before it

was real. In this he was steadily seconded by his wife, so

that any upward move they made was made in advance, as it were.

Thus the pair led an anxious life of it in secret. Many

a day had Mr. Haycraft worked ten times as hard as ever he had done

for a master, and worked, too, with ruin staring at him over his

desk-rail, till his hand shook, and his brow ached, and his brain

reeled, and he lived ten years in every five. And many a day

Mrs. Haycraft sat in her drawing-room scheming to keep up

appearances, and finding it harder work than cooking in the back

kitchen ever was.

It was in this first era that their children were born to

them—three daughters; and very lovely children they were, growing up

likewise into very lovely young women, tall and slender, neither

fiercely dark nor gently fair, but clear-browed, dusky-haired,

soft-eyed maidens. At least this description suits the two

eldest exactly, Harriet and Maria being very much alike; but the

youngest, Lilias, added a more sportive grace, a more vivid fancy,

and a warmer heart, all of which told in her aspect and her eyes.

It was in the second era that they were formed—for this world

and for the next—that they got their shallow, showy education, their

love of dress and display, and their dread, and hate, and shame of

poverty, however honourable. And yet their mother believed in

her heart that she had done the very best for them, and that they

had well-nigh reached the highest point of mental culture and

superiority. And she had done her best according to her

notions. Even in the nursery she had been careful that they

came into contact with nothing vulgar; and when Lilias was a baby of

two years old, and Harriet was only eight, she had engaged a

superior nurse to be with the children always, one whose speech and

manners were alike above reproach, and whose piety had been included

in the recommendation, as a guarantee for her strict integrity.

Mrs. Haycraft had been sometimes a little jealous of this woman's

sway over her children; but it was exercised so gently and lovingly,

that there was no ground of offence. She had left them when

there was no further need of her services, when Lilias at seven went

to school with her sisters; and she had speedily been heard of no

more—forgotten, as though she had never lived among them, and given

her life so fully and freely to their service.

It seemed to Mr. and Mrs. Haycraft a complete justification

of all that they had done when their eldest daughters married; for

they married early, and they got the two best matches in the

neighbourhood, as far as money went.

Harriet married a Mr. Armstrong, the son of a man who had

made an enormous fortune in one of the ephemeral trades of London.

He was still a young man, though looking older than his years, for

he was coarse, sensual, and overbearing. But Harriet seemed to

think him all that was manly and noble, and she was quite formed

enough to know her own mind at three-and-twenty. Her sister

Maria was only twenty when she, too, married, within the year, a

friend of Mr. Armstrong's, a man old enough to be her father, almost

her grandfather. No undue pressure was put upon her. She

was like a child tempted with cakes and toys, who realises the cakes

and toys, but not the condition attached—the hard lesson, the

distasteful medicine, the new and strange, and, perhaps, the

unloving faces. There were many things she knew that her

father could not afford. Mr. Scales could afford anything; and

it was whispered to her that a time might come when her father would

be taken away, and that he could leave her nothing at all.

Nothing!

Maria was in haste to be as rich as her sister; to have as

fine a house, as beautiful gardens, as much jewellery, as many

dresses. Mr. Armstrong spent lavishly on his beautiful wife,

and gave her trappings of gold, just as he mounted superbly the

harness of his horses. Alas for poor Maria! Mr. Scales

was anything but lavish; he was unutterably mean. The fine

house and beautiful grounds were there, but he lived in the heart of

them, much like a rotten, dried-up kernel in a glossy, beautiful

shell. The young wife soon found this out, and owned it, with

the frank grief of a child, and with many sobs and tears. And

so the unequally yoked pair began to lead a most unhappy life.

But even Maria was partially reconciled to her fate when her

father died, worn out with the long struggle to stand well with the

world, and when she knew what were the consequences of being left

with nothing. Everything had to being be given up to the

creditors, the furniture sold off, the pretty house abandoned, and

Lilias and her mother had to become dependents on the bounty of the

sisters' husbands.

Mrs. Haycraft went to live with the Armstrongs, while Lilias

was handed over to Mr. Scales. Mr. Armstrong would willingly

have taken both; but he would not humour "that miserly fellow," as

he termed his brother-in-law. No, he was determined to make

Mr. Scales do his share. And owing to this resolution it came

to pass that the helpless mother and daughter were treated with

anything but delicacy and kindness.

Lilias being a proud and sensitive girl, resented it

bitterly; and finding that she would have to beg or to fight for

even the smallest allowance, as Maria had to do, and that without a

claim upon the niggard her begging or fighting might have less

effect, she looked out at once for a situation. Her friends

opposed her, every one, and Mr. Armstrong even offered her money,

but he did it in a way which offended her, and she carried out her

purpose. Soon after Mr. Armstrong settled on his wife's mother

a hundred a year, and desired Mr. Scales to do the same, and in the

squabble about this Mrs. Haycraft left the roof of her son-in-law,

and went to live alone in lodgings.

It was a sad and lonely widowhood for her, and it made her

very bitter. She was especially bitter with her youngest

daughter, and blamed her freely for what had happened, especially as

Mr. Scales made her conduct a plea for the non-payment of the

hundred a year fixed by Mr. Armstrong. He expressed his

willingness to provide for the young lady under his own roof, but

not otherwise.

Lilias had found a situation in the neighbourhood as nursery

governess to the children of a Mr. and Mrs. Ogburn, and she had not,

to use a quaint North-country phrase, her sorrows to seek. It

was about as uncomfortable a house as the poor girl could have

entered.

A cook and a nursemaid comprised the whole establishment, far

too small a staff of servants for so large a house and family.

As a consequence everybody was over-worked, except the mistress, who

spent her superabundant energy in scolding. She had no

objection also to do a little cooking, but with her children she

could not be troubled at all. They were a pack of little

savages, and the keeping of their persons tidy was a task which left

the cultivation of their minds a long way behind. Lilias did

her best, in a slipshod way, to get a little reading and spelling

into the heads of her pupils. Also there came to her a

freshening memory of her own childish days, and of the nurse to whom

she (perhaps because she was the youngest, the little one) had been

the most tenderly attached, and who, when father and mother were

receiving visitors or paying visits, or idling away the sacred

hours, had gathered the children round her, and taught them hymns

and holy lessons, and knelt with them in prayer. And she

gathered those unruly ones round her, and tried to teach them, too,

something more than the prayer which each repeated like a charm at

nightfall. So much she felt constrained to do; but the time

had not yet come when the holy influence working secretly within

would penetrate her whole life. Lilias had much to learn and

to suffer before this.

And in her troubles with the children she was driven to make

an ally of the nursemaid, a black-eyed rogue of a girl, who

lightened toils, and amused her in her weariness. The girl had

the profoundest admiration for the governess, and pronounced

judicially in the kitchen that she was "more of a lady than the

missus."

But this association was not good for Lilias, not even

harmless, as it might have been for most. Her education had

been, of its kind, as defective as the others, and her nature was as

luxuriant and untrained.

Lilias learnt to think lightly of the misdemeanours which

furnished her with amusement. Emma had her young man, and was

wont to meet him at odd times. She was especially fond of

giving baby an airing on Saturday afternoons, and by no means fond

of the company of the elder children on these occasions. It is

to be feared Lilias aided and abetted her in escaping from the

latter, even to her own cost. The girl had confided to her

that she was going to be married.

One evening, when Lilias was doing some needlework for the

nurse, who had still the baby in her arms, though it was hours past

the time when he ought to have been asleep, it came into to her head

to ask how she had got acquainted with her lover.

She answered readily, "My cousin and me were going to the

theatre on Boxing Night. We had left our places for a bit of a

holiday. She's a 'general' up in Holloway, my cousin is.

There was a crowd at the door, and we were in it tight as tight,

when I feels something pitching against my ear. It was a

nut-shell; but I couldn't see who throwed it. There was

another came, and hit me on the cheek, and then one went right into

my ear, and I kept putting up my hand, and looking about, but still

I couldn't see where they came from. He told me afterwards it

was he as flung them. Well, when we were going home, at eleven

o'clock it might be, a young man comes up behind, gets on before,

and then turns and has a look at me. I had a good look at him,

too, you may be sure. He gave a nod, and says he, 'I'll see

you home.' Says I, 'I can see myself home, thank you;' but he

walked all the way with us, though we did not speak. I was

always meeting him after that, and he always nodded, and said 'Good

evening!' quite polite. Then I didn't meet him one day; but I

knew now where he worked. It was at a smith's, and as I was

going into service again the next day I went and had a look at him.

He caught sight of me through the smithy door, and laughed, and I

ran away. Well, I went out that evening to buy something.

It was after work hours, but I didn't meet him, and I stayed out a

goodish while. And what do you think? When I got home,

there was my gentleman sitting at tea with my mother."

"He knew her, then?" said Lilias, interested.

"Not he. He watched me out, and went straight indoors

to my mother, and said he was after me; and he made hisself so

uncommon sweet that my mother was quite taken with him."

"And what did you do then?"

"I didn't say anything before mother, but when I got him

outside, I told him it was like his impudence."

"But you did not send him away again?"

"No, it was no use he had set his mind on me," she answered,

with evident admiration of his boldness. "Mother thought I had

been keeping company with him, and he asked me to marry him

off-hand, for he was in full work, and earning good money."

"It was very dangerous," ventured Lilias. "He might

have been a bad character."

"Oh, no fear," replied Emma, "so long as it's one of our own

sort. I wouldn't speak to a gentleman that way for nothing,"

she could say.

And this was Lilias Haycraft's sole companion—this rude, bold

girl; and she was finding her way, by many a simple service, and by

a never, failing sympathy, to Lilias Haycraft's heart.

One day Lilias had obtained leave of absence for an hour or

two, after the children had gone to bed. They had been as

tiresome as possible, and it was late before she started—quite eight

o'clock. She was going to visit her sister Maria, whose

husband was absent that evening, and the opportunity might not soon

again occur, for Lilias was no longer openly welcomed to her

sister's house. She and Mr. Scales had come to an open

rupture, and that gentleman had expressed a wish to see her no more.

It was an hour's walk to her sister's house, and in the eager

confidences which they poured out to each other, time passed

unheeded. But at length Lilias was about to go, seeing with

consternation that it was long past ten, when the master's knock

resounded through the house.

The master himself followed. After looking about him a

little he came upstairs, and encountered Lilias standing her ground

in defiance. Mr. Scales had been drinking freely. Lilias

stood and looked contempt at him with her great grey eyes, but left

him to speak the first word. Maria was about to say something

conciliatory. "My sister," she began. But he passed her

over.

"What are you doing here?" he asked of Lilias, rudely.

His voice and manner exasperated the girl, but she only threw

back her head, and darting at him a look of withering scorn, turned,

and putting her arms round Maria, said, "Good-bye, dear. I'll

come and see you as soon as I can."

"You'll do no such thing," said Mr. Scales; "you'll never

enter my house again." He went up to the bell and rang with

fury.

The maid was not far off, for she answered the summons before

she could have had time to quit her legitimate abode.

"See this person to the door," he shouted, losing all command

of himself. "She is not to come here any more, do you

understand; and if ever you disobey me in this it will cost you your

place, I can tell you."

"I don't care if it do," retorted the girl.

"Go down stairs, Mary," said her mistress, and the girl went

away, leaving her master to show Lilias out. Beside himself

with rage, he pushed her through the open door, and closed it upon

her with a force which shook the house, and made Maria sink

trembling on her knees.

Lilias hastened down the steps and away from the house with

burning indignation, chilled by a feeling of uneasiness at finding

herself out alone, almost in the midnight for the first time in her

life. She shivered as she went forth into the lonely road.

She was feverish with excitement, and the night was bitterly cold.

She walked on swiftly; then she fancied that she heard a footfall

keeping pace with hers, till the walk became almost a run, and her

heart was beating hard against her side. There was no one

either behind or before her, and she reached the Ogburn Villa

without having met a living creature.

To her dismay, the outer gate was shut; but it had a bell,

and Lilias seized and rang it with panting eagerness. She

stood waiting, but there were no answering signs from the dark and

silent house. She began to feel very faint; she had had

nothing save the schoolroom tea, following a more than usually

meagre dinner.

She rang again with all her might.

Still no answer.

Somebody was coming along the road at last, coming nearer and

nearer on the sparely-lighted pathway. She was standing in the

circle of light thrown by a lamp opposite the gate. The

surrounding darkness would bide her from the passer-by, and she was

about to step into it. But what had happened to her? The

lamp was reeling, her limbs refusing to sustain her. She tried

to grasp the wall, and slid heavily to the ground.

A quick step crossed the road and stopped where she lay, a

face bent over her closely, a face expressive of pity more than

astonishment to see a fair young girl in such pitiful plight.

He lifted her head, as one would lift a broken lily, and having

lifted it, forebore to lay it down on the damp earth. The face

he saw was fine as statuary marble. It was thin, and that made

it more spiritual than was natural to it, for it had not lost the

roundness of early youth. He could see the pathetic loveliness

of the still brow and of the sweet curving lips, the perfect shape

of the closed eyes.

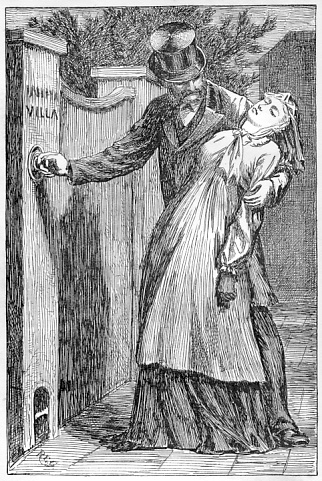

"The stranger raised her on one arm, and thus

supporting her went at the bell."

By way of doing something, the stranger raised her on one

arm, and thus supporting her went at the bell. He had seen her

pull it, as she stood in the light there, before she fell. But

there was no answering result in his case any more than in hers, and

he must have nearly pulled it down. Exasperated at his

powerlessness, he was about to lay down his burden, leap over the

wall, and ply the knocker which was most likely to be found on the

house-door inside, when his burden stirred and moaned. Once

more the stranger bent over her, and asked, in a voice which had the

tone of a gentleman, if he could do anything for her.

After a few minutes she spoke, recovering rapidly. "I

must have fainted from cold and fatigue," she said. "I cannot

get them to hear the bell."

"Neither can I, and I have tried my best," he answered.

"It rings downstairs," she said "and I suppose they ceased to

expect me to-night, and so locked up the house and went to bed."

"Who are they?" he asked, thinking the excuse insufficient.

"Is this your home?"

"I am only the governess," said Lilias, with a touch of her

natural satire.

He laughed. "Shall I get over the wall and knock them

up?" he asked.

"My mother's lodging is not a great way off. Perhaps I

had better go there."

"Will you take my arm?" said the stranger, convinced by her

voice and manner of the girl's respectability, and treating her with

profound respect. He would have done the same, however, had

she been what he at first had taken her to be.

"I think I can walk without assistance, thank you," said

Lilias, still faintly, "but I shall be glad of your escort a little

way."

There was that in the manly voice which reassured her, and

she still trembled at the desolate streets.

"You had better take my arm," he repeated, kindly, and Lilias

left the Ogburn Villa leaning on this utter stranger.

As the tinkle of that down-stairs' bell reached Mrs. Ogburn's

ears as she lay awake that night it ought to have sounded, and

sounded again, "Her blood shall be required of thee."

Lilias at length reached her mother's lodging, and with the

exchange of a few more sentences, in which Lilias explained her

dilemma, as far as she could, and her companion expressed his

sympathy, they parted. "I am at home now," she said, "thank

you." She stopped as she spoke, and he, lifting his hat, bade

her good night, and was gone.

He returned, however, saying, "You may find the same

difficulty here."

"Oh, no, my mother will be sure to wake, if no one else does.

See, here comes a light. Thank you, thank you," she repeated.

He went away this time, and Lilias was admitted without

delay.

The poor girl longed for her mother's arms, as she had never

longed since her babyhood; and there was her mother looking cold,

cross, frightened, angry. People are not apt to be

sympathetic, knocked up out of bed on a bitter November night.

Lilias explained what had happened, and was met by a storm of

reproaches. What business had she to stay out so late?

What business had she to be at Maria's at all?

Lilias broke down and wept, and thought everybody cruel and

unjust. alike, and said so, and went to bed without tasting food.

On the morrow she was too ill to proceed to Mrs. Ogburn's,

and her mother had to go and make her excuses. Mrs. Haycraft

had spirit enough to defend her child, angry as she was with her,

and she met Mrs. Ogburn with so much firmness and dignity that that

lady felt herself under some restraint. She was going to say

that she would not have under her roof a young person who frequented

the streets at such hours, instead of which she told a story, and

said that no one had heard the bell, adding that Mrs. Haycraft was

aware that she was not obliged to take her daughter back after what

had occurred, and that it would be impossible for her to account to

any other lady for the absence of the night.

Mrs. Haycraft told her she might do as she pleased, and left

her haughtily, but it was to vent all her vexation and affront on

Lilias

During the day, however, Mrs. Ogburn changed her mind.

She had intended to dismiss Lilias without a character; but Lilias

suited her exactly, and she thought that to keep her without one

would be better. She found the children, let loose upon her

while the nursemaid was occupied with other duties, which seemed

nearly all day, insufferable. It was wet and cold, and she had

a commission to execute, and no one to send. Before the

evening was over, she sat down and wrote, in what she considered

dignified terms, asking when Miss Haycraft would be able to resume

her duties.

So Lilias went back and resumed her slavery, ten times the

slavery it had been. Mrs. Ogburn knew that she possessed a

power over her which she had not possessed before, and she used it.

It was open to her to doubt the correctness of Lilias's behaviour,

or at least to profess such a doubt, for she did not feel it, in a

specific form; it needed only to be young and poor, to be pretty and

unprotected, to awaken such doubts in Mrs. Ogburn's mind.

Lilias winced under her hints and sneers. She longed to

turn upon her the full light of her scorn, but she dared not; and

thus it was that the bondage reached her spirit. Her character

was in the hands of this woman, who might destroy it with a hint;

that much of it certainly on which she depended for bread. The

world was beginning to seem very hard to Lilias.

CHAPTER II.

FIVE years have

passed away—a large portion of the individual life, a portion which

determines much, if it be in the middle stage of it—often all the

future of a man or woman. Those years have wholly changed the

life of Maria Scales. Mr. and Mrs. Scales have been at the

sea-side for a week. It is August, and the weather is

oppressive even there. Mr. Scales is worse than usual; he is a

confirmed invalid, paralysed, and helpless. He is worse than

usual, that is to say, more restless, fretful, and irritable, and

also evidently more alive to what is going on around him. They

are sitting in a handsome ground-floor apartment, communicating with

a bed-room behind. Mr. Scales never goes up stairs, even at

home; and Maria always sits beside him, for he cannot bear her out

of his sight. He is perfectly silent and quiet, indeed he is

usually so, except when he misses Maria, though perhaps she has not

been ten minutes out of the room. "She is terribly tied to

him," say her friends; only he is just like a child, and goes to

sleep in the middle of the day, and to bed long before the day is

done.

Maria is pale, but not colourless, thin but not worn.

There is an altogether new expression on her face. Soul and

body appear to be in harmony, and that harmony in itself is health.

Now she rises, and drawing near to her husband with a look,

which has in it more of the daughter than the wife, and more of the

mother than either, she asks if he will come out for an airing.

He shakes his head, and signifies refusal. But she knows that

it is always so, that he does not like to be disturbed, only the

doctor has said he must be roused to take a little out-door exercise

every day if possible. So she coaxes and persuades him, and at

length rings for his servant to come and prepare him for his chair.

How much he knows, how much he feels, how much he remembers,

it is impossible to say, connected speech is so difficult to him, so

unintelligible to others. Maria is thankful when she sees a

gleam of appreciation come into his face. The doctor thinks he

has neither taste nor smell. Food the most exquisite and the

most tasteless seems alike to him. Maria in the bloom of her

youth and beauty is wedded to a man half dead.

There was a lengthened period after his seizure, during which

life seemed confined to the body alone. He saw without seeing,

heard without understanding, appeared insensible alike to pleasure

and to pain, certainly to the former. The good things of this

world had turned for him to dust and ashes; the lessons of that

terrible time of many months' duration had sunk deep into the young

wife's heart, and would have produced an apathy of despair, or a

deeper, deadlier, more hardened worldliness, if something in her

heart had not risen up to meet them, and that something was the

leaven of Christian truth implanted in the old nursery days.

She felt as if she had fallen asleep and had dreamt a terrible

dream; a nightmare dread had come upon her, but now she was awaking.

Life could not be such a nightmare, with the eyes of the Father in

heaven upon it, with the light of the Saviour's love chasing away

the darkness, that she might rise and live.

Not all at once was Maria's heart leavened with the spirit of

the kingdom. She set herself to do the duty nearest to her,

and strength came, and newness of life in the way which she humbly

trod. She watched and waited on her helpless husband, whom in

that bad dream she had wholly hated, as devotedly as if she had

entertained for him the tenderest regard, so that before

consciousness and memory returned to him in any measure he had got

so accustomed to her presence, her voice, her hand, that he clung to

her like a sick child to its mother.

He has been coaxed out of his chair by his wife, and leans

upon her arm. She leads him half way along the upper terrace

of the Grand Parade, and seats him in the sunshine, looking out upon

the sea. It is quite quiet there, though there is a crowd upon

the beach below. Mr. Scales cannot bear the crowd. He is

great-coated and shawled, while Maria's morning dress is of muslin,

with a mantilla of lace. The cool breeze from the sea is

delicious to her, but it makes him shiver. The seat is too

exposed, and they move away to another. In a very short time

he tires, and wants to go in-doors.

She rises and leads him away, back to their lodgings on the

Parade. She tries to gain his attention to the beauty of sea

and sky; but to no purpose. He only asks if it is time for

lunch. It is not more than eleven o'clock; but there is a

cordial which he may take. She administers it with her own

hands. His servant unwraps him, and seats him in his cushioned

chair. They have brought it down with them. She places a

footstool for his feet and a table on which he may rest his arms,

and leaves him. She would not do so now, only she has promised

to see Harriet this morning. Harriet arrived yesterday with

her husband and children.

Maria goes forth again and walks along the terrace. She

looks out with eyes of dreamy sadness upon the sea, many-shaded and

ever restless. It is neither still nor stormy, but just

crisped with a light steady breeze. Her face is sadder than

usual. She loves the sea, but it invariably makes her sad.

She walks along the whole terrace, and returns again. Harriet

has not yet had time to be abroad, but doubtless the children are.

She descends to the lower stone terrace—the upper is laid out like a

garden. From it she can see the nursery-maids and their

charges, sitting or moving on the bright shingly beach. She

tries to discern among the busy groups her sister's children, and

succeeds. There they are with their nurses. Baby

smothered in fat and finery on the lap of a staid elderly woman; his

predecessor, a little chubby thing, clinging round the neck of a

stout girl, who can hardly hold her as she jumps with delight while

they run before each chasing wave. Two girls and a boy are

there besides in sea-side suits of blue serge and black glazed hats

with blue ribands.

Maria has beckoned, and they have seen her. The girls

are running to meet her, their yellow manes flying behind them.

They are fine, strong, straight-limbed girls, larger and coarser in

form and feature than ever their mother was. The hope of the

house, Master Joshua, is his father's image, but in finer clay—in

porcelain, perhaps.

Maria had time to go down on the beach with them and ask for

the infant Hercules, as she chose to call her baby nephew. She

then inquired of the nurses when Mrs. Armstrong was likely to make

her appearance on the scene.

"There is mamma!" cried the boy, catching sight of her in the

distance. "There is mamma!" echoed the little girls, jumping

for joy, and they and their aunt set out to meet her.

Could that be the slim, lily-like Harriet, that portly

British matron?—a perfect type in face and figure of all that is

most comfortable, most prosperous, most egotistic in the character.

No one would have recognised her who had not seen her during the

last years and beheld the growth of that wonderful girth and

expansion. In five years, too, fashions change greatly, like

everything else, by only changing a little year by year.

Harriet had grown stout and florid, and her flounced costume, or

costume of flounces, made her look stouter still. And Harriet

was in the height of the fashion—a fashion suiting youthful faces,

and not the best of these, and slim, youthful forms. Her head

was crowned by a very small high hat, a perfect contrast to Maria's

quiet coiffure, which, though it followed the prevailing mode, did

so with a limit, showing two rich bands of plaited hair at the back

of her head, only thick and heavy because the rich brown locks were

so.

Mr. Armstrong was by Harriet's side, in a very light tweed

suit, yellow sand-shoes, and a white felt shell hat, round which he

had fastened a puggaree. He too had gained flesh, and it did

not lie lightly on the huge frame. His very eyes stood out

with fatness. The self-complaisance of the wealthy Englishman

was stamped on every feature and on every gesture. Harriet had

made a good wife to him, had worn her chains as ornamentally as

possible, covering them with gold rather than with flowers, and she

had greatly improved Mr. Armstrong's manners, unknown to that

gentleman. They had wealth, they had goods, they had children

in plenty—all that money could purchase of comfort, of ease, of

service, of pleasure—and an inscrutable Providence had refrained

from inflicting on them any of the lesser ills of life. Mr.

Armstrong's children had never had the measles! If he had been

a poor man he would have had to nurse four of them while Mrs.

Armstrong was getting over her fifth confinement.

And nothing on earth would have made Mr. Armstrong believe

that he had not deserved all these good things, or conversely that

the people who possessed none of these good things had not failed to

deserve them. Mrs. Armstrong had come to share in this belief.

They went to church once a day on Sunday—all respectable people did.

It would be the most wonderful of earthly phenomena, if it was not

as common as the daylight, that it never occurred to them to ask

themselves what it was all about. Why people should call

themselves miserable sinners once a week who thought themselves

anything but miserable or sinful. How they could listen to the

beatitudes, and acquiesce in the blessedness of the poor in spirit,

and the meek, and those who mourn. If they had heard them for

the first time from the lips, say, of Chesub Chunder Sen, they would

have voted them a string of pagan curses, spoken in bitter mockery.

They despised the poor in spirit, of course. The meek!

Why, meekness was always to be suspected. As for the mournful,

it was generally people's own fault if they were depressed.

Christianity might as well never have existed for all the influence

its spirit had exercised on these nineteenth century church-goers.

The idea of self-denial never came into their minds. And as

for universal charity, it was to them universal humbug.

They were family people. It was a phrase of Harriet's,

and of her husband. It is a phrase much in favour with the

British Philistine. Yes, they cared for their own, because

they were their own. Social duty, social tenderness they

comprehended not. It never came into Harriet's heart to feel a

pang when she saw little feet naked to the cold, because she had

kissed that pink pair at rest in their dainty cot, or to pity the

little pinched faces that sometimes looked through the lodge gates

at home, having wandered from a wretched suburb not two miles off,

because the roses on the cheeks of her own little folks bloomed all

the year.

A little girl seized hold of each of Mr. Armstrong's hands,

and left their mamma and aunt Maria to come on behind.

The former appeared greatly fluttered by something she had to

communicate. She seemed quite relieved when her husband was

fairly out of earshot, and turning to Maria, she whispered, "You

won't guess who I saw yesterday."

Maria did guess. Yet she said, "Not Lilias?"

"Yes, Lilias," was the answer.

"And where is she? What is she doing?" asked Maria,

eagerly.

"I could not have spoken to her," replied Harriet, in a tone

of reproach. "Mr. Armstrong and the children were with me; but

even if they hadn't, I don't think I could, after the way in which

she behaved."

"Did she show any desire to speak to you?" asked Maria,

making no comment on her sister's words.

"Not at first," replied Harriet. "You know we went to

the station to meet a friend of Mr. Armstrong's, who was coming to

dine with us, and I saw her stepping out of one of the carriages of

the down train. A gentleman, whose face I could not see, was

handing her out. She started, and drew back when she found I

was looking at her, and then she would have come forward, but I

looked as if I did not recognise her."

No one could look that better than Mrs. Armstrong, as her

sister knew.

"How could you, Harriet!" exclaimed Maria, with tears in her

eyes; "and you don't know where she has gone even!" she exclaimed.

"How should I?" asked Harriet, indignantly. "You know

very well that Mr. Armstrong would not allow me to have anything to

say to her. It is very hard, I think, to have such a person in

one's family. I'm sure it broke poor mother's heart."

"Do you think she is staying here?" asked Maria. "I at

least am free to seek her;" and she sighed.

"I suppose she has come to stay here," said Harriet. "I

caught sight of her again in a carriage, with the gentleman and a

little girl."

"Oh, Harriet, I hope we shall find her!" cried Maria, her

heart beating to faintness.

"I am sure I hope not," was Harriet's reply. "I hope I

shall not see her again. Indeed, I think she will leave the

place when she knows we are here. I could not bear to meet her

again, and, to do her justice, she seemed very much ashamed of

herself when she caught sight of me the second time, and stooped

down, pretending to kiss the child, a poor, pale little thing.

Our fly went quite close to hers in passing. I do hope,

Maria," she concluded, "you won't go seeking her out here. My

children don't know of the existence of such a person. We've

never mentioned her name from the first."

There came no answer from Maria.

"You are coming into tea this evening," said Mrs. Armstrong.

"I think not," answered Maria. "Mr. Scales is getting

very restless. I fear we shall have to take him home again.

Good-bye," she added mechanically, and turned sadly away. Not

her sister Lilias' fate, however dark it might be; not her husband,

stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted, depressed Maria, like

prosperous, respectable, well-satisfied Harriet.

To get rid of her sadness, she walked away in the opposite

direction before she ventured home. "Lily, Lily, my little

sister Lily," her heart was crying, with pangs of tenderness.

She had gone back to the early days when Lilias was the baby,

thought so merry and so wise, and such a miracle of baby beauty.

It was as Maria had anticipated; in another week she had to

return home with her husband, leaving Harriet to enjoy herself in

peace, for Lilias had not appeared. In vain had Maria spent

every hour which she could spare in looking for her. She had

paced the terraced parade at all times, till she knew its

frequenters at any distance. Often and often had she followed

a form taller and more graceful than others, only to turn

disappointed from the face of a stranger. No Lilias was there.

It is necessary to go back a little, to take up the thread of

Lilias Haycraft's story; back to days after that November night,

when she fainted at the inhospitable door of Ogburn Villa.

In the afternoon, when nurse was ready to take care of the

children, Lilias was not seldom sent to do errands for Mrs. Ogburn,

especially if the weather was bad. It spoilt people's good

clothes to go out in the wet, Mrs. Ogburn reflected, and especially

to get into those nasty omnibuses which people who lived in the

loftier suburban regions were compelled to do, if they wanted to

reach the lower region of shops and shopkeepers.

It was about a week after the night of her faint that Lilias

had been thus sent forth to encounter sleet and slush in matching

some wools for Mrs. Ogburn, and procuring some stockings for the

feet of young Master Ogburn, who had grown out of his last year's

set. It was between four and five, and already the wintry day

was darkening before she had made her purchases, and with her hands

full of packages, took her seat in the return omnibus.

There was in the omnibus only one gentleman, leaning on an

umbrella which he had planted between his legs, and one poor woman

with a bundle in her lap and a wedding-ring on her finger.

Lilias, who was feeling particularly depressed and miserable, took

no notice of either. The young gentleman and the poor woman

alike sat gazing at her, the latter unconsciously refreshing herself

with the beauty which shone even in that gloom with its divine

lustre. Lilias could not look miserable, feel what she might.

The mouth might take a sadder curve, and the eyes a more mournful

gaze; but nothing as yet could dim their lustrous shine, or change

the ivory of the fair brow, the rose-leaf hue and texture of the

cheek. Man and woman alike felt glad to look on her.

But there was something more than a perfectly reverent regard

for her beauty in the gaze of her opposite neighbour, continued

because she was gazing as persistently out of the misty window into

the gas-lit street through which they were passing. There was

something of recognition in his look, but he did not venture to

address her.

The poor woman with the bundle signalled to the guard to

stop. She and her bundle had arrived at their destination,

diving into one of the side streets of the crowded thoroughfare, and

the omnibus went on. But Lilias had taken the opportunity of

mentioning the place where she wished to be set down, and at the

sound of her voice the face of the gentleman opposite to her lighted

up suddenly. When he spoke the recognition was mutual, and

Lilias blushed rose-red as he said, "I was not quite sure until you

spoke; but I am glad to meet you again. I hope you are

well—that you got no harm by being shut out the other evening."

All this was said, rather disjointedly, before Lilias had

recovered sufficient self-possession to speak at all, the source of

her embarrassment being in reality that she had never ceased to

think of the kind and courteous stranger since they had parted on

that night. He on his part had been absolutely haunted by the

form of his companion, and still more by her voice. When he

heard it again it seemed quite familiar, and not at all like the

voice of a stranger.

They were young, each seemed good and fair to the other, and

they could not sit opposite for half an hour without speaking, as

Fate had introduced them to each other. The stranger drew from

Lilias more of her circumstances than was altogether necessary, and

more concerning Mrs. Ogburn than was altogether prudent; and when

she got out of the omnibus, he also got out unquestioned; and as she

would not allow him to carry her parcels, he held his umbrella over

her till he had seen her to Mrs. Ogburn's very door.

"I have looked for you every bright day," he said at parting,

"now I shall look for you every gloomy one;" and the words made the

girl's heart beat strangely as, having said good-bye, she ran up the

steps of Ogburn Villa without once looking round.

Lilias and her new friend had made no appointment; from this

Lilias would have recoiled with a strong instinct which as yet was

not lulled to sleep. But they met, nevertheless, again and yet

again. They learnt each other's habits. He was poor like

herself, she hoped and believed, from something he had dropped; but

he was a gentleman, she felt sure of that. He came up about

five o'clock in the omnibus regularly; but he was not so regular in

going down. He was sometimes so late that he met Lilias out

with the children, and exchanged smiles and bows with her. He

took his work home with him, that was it.

What was it that tempted Lilias, when he asked her name, to

say Lilias Lindsay? The name was her own, it is true; it was

her middle name, given to her in baptism, and therefore it cost the

thoughtless girl no shame to utter it. She was not telling a

lie. It seemed to keep him at a little distance, too.

Perhaps he did not really care for her. He had never said so

in as many words. Not a syllable of love had ever passed

between them. He might only be amusing himself with her, after

all. Alas! what a pang that thought gave her, that unworthy

thought, for she put it from her as unworthy as soon as she

conceived it. Was he not uniformly kind, gentle, respectful,

sympathising, chivalrous in his ideas of women, and in his treatment

of them? Yes, he was all these to Lilias, and she loved him

unbidden with her whole heart and soul.

Lilias's treatment at Ogburn Villa had become worse and

worse. Mrs. Ogburn's insolence was unbounded. There was

a cause for it. Mrs. Ogburn had a brother home from India, and

the more Lilias repulsed this gentleman, the more desirous he seemed

to be of her favour. He had found out that she was well

connected, and he could see for himself that she was exceeding

beautiful, and he insisted on her being treated less as a servant,

and more as a member of the family, which meant that he wanted to

see her in that stupid drawing-room in the evening. It had

been opened in permanence for his entertainment.

Mrs. Ogburn felt exasperated, and she began seriously to wish

to get rid of Lilias at the cost of any amount of inconvenience to

herself, and Lilias retailed her persecutions to her friend.

Things were coming to a crisis, she said, and she should be obliged

to leave. Had she a home to go to? Yes and no. Her

mother was poor, and had urged her to remain where she was at

present. Then came the history of her wrongs, real and

fancied, and her relations were voted savages. Just at this

time, too—Christmas time—her friend was going away. Would she

write? He would leave a letter for her at the little

stationer's shop, where the post-office was, and he hoped to find a

letter there for him on his return. He had told her his name

on the occasion when Lilias had given and yet withheld her own.

It was Christopher Ward.

He went away; and never had a Christmas and New Year seemed

so dismal to Lilias. Only she had her letter—her first letter.

She carried it about in her empty little purse, and felt richer,

richer than Mrs. Ogburn and her Indian brother rolled into one.

It was thus that a correspondence commenced; and that their

meetings, often brief and unsatisfactory, continued till the month

of March was in.

But Lilias had been watched for weeks, and at length Mrs.

Ogburn, in a fit of fury, owned it, and virtually dismissed her.

She was to go at the end of the quarter, which was now close at

hand. Then she wrote to her lover a hurried note. "She

has found us out," it said. "I cannot tell you what she said,

but there was a grain of truth in the bushel of scandal, and I must

see you no more. If we meet again"—the last sentence was

intolerable—"If we meet again, it must be to say good-bye for ever."

Instead of saying good-bye for ever, the next day Lilias left

a little parcel at the stationer's, and called for it later in a

cab. And in the cab was Mr. Ward. As they drove off

Lilias covered her face with her hands and wept.

She had left Mrs. Ogburn's without her quarter's salary, or

even her clothes; but she had laid on the hall table a note

requesting that they should be handed over to her mother, which Mrs.

Ogburn proceeded to do. That lady was altogether much edified

or built up in her opinion concerning Lilias's evil behaviour, and

she chose as her successor the very plainest person of the score or

two who presented themselves for the vacant situation.

And she did not communicate to Mrs. Haycraft the news of her

daughter's flight in the gentlest manner. It fell upon the

poor woman with a terrible shock. She had been making up her

mind too, just then, to have Lilias back again, acknowledging to

herself that she had been rather harshly treated. And now she

was gone beyond recall. Mrs. Ogburn sent for her to tell her

that Lilias had left her house, that for some time she had been

carrying on a clandestine correspondence with a gentleman, and that

she had been seen to go away with him at last.

CHAPTER III.

AFTER the repulse

which her hasty and almost unconscious advance to her sister had met

with, Lilias was driven to the hotel where she had been going to

stay. It was late in the evening when she issued from it

again, and she was closely veiled, and chose to walk with her

companion on the loneliest part of the cliff. She only issued

from it once again, and that was to enter a carriage with all her

belongings, and drive away to a solitary house several miles distant

along the coast. She had said to her husband—for her husband

he was as far as he or she knew—that there were people here who knew

her intimately, and from whom she could not conceal the fact of her

marriage. He had been on the point of saying, "Don't conceal

it, then; let them, let all the world know it," for he was, if

possible, more disgusted with his mode of life than she was.

And yet he had held back many a time before from an open declaration

of that which had been so long concealed, the concealment itself

creating its own necessity.

Christopher Ward was the second son of a poor but proud

family, who had devoted him to business in despair, and sent him to

a city office with heart-burning and shame. Having carried off

Lilias from the shelter of a respectable roof, he married her.

If he had carried her off innocent and loving, as he knew her to be,

to a life of sin and shame, as hundreds of young men of his rank and

education do, he would not have been the man he was; he would not

have won the ready friendship of every man, the tender esteem of

every woman, the love of every child that came near him. Nor

would this Lilias have loved him as she did. He was incapable

of contemplating an act so dastardly, but he made the great mistake

of concealing his marriage, a mistake of which time increased the

offence, while it made the reparation more and more difficult.

He had not, it is true, contemplated any action at all; but

his love and hers had proved too much for him. Lilias loved

him for himself, he could see. "She does not know I have

anything in the world but what I stand in," he said to himself, and

it was true. And he loved her in return, as it was in his

passionate, affectionate, impressionable nature to do.

So he soothed the weeping, trembling girl, who had committed

herself only too easily to his care, and took her straight to his

landlady's house in Highgate, saying, as he presented her, "Here,

Mrs. Watson, I have run away with a young lady, and I mean to marry

her to-morrow. You must give her a room for a night."

And Mrs. Watson, who knew nothing of her lodger, except that

he paid his lodgings, and had unexceptionable shirts and stockings,

took Lilias in without more ado, saying, "Lawk, Mr. Ward, what a one

you are for a joke!"

She was quite taken aback, as she phrased it, with Mr. Ward's

easy way, and thought the lady would turn out to be his sister, he

treated her so sober-like.

How well Lilias remembers every incident of that evening.

How they had tea out of a battered metal teapot, and cut their bread

and butter with knives worn to dagger-points, and how, making up

their minds to forget everything, they got childishly gay, and had

an hour or two of the strangest spirits, Lilias especially.

Christopher thought he had never seen her equal for beauty and for

wit.

At length he became tender and confidential, thinking of the

morrow. He could see her alarm and sorrow when he told her

that he was the son of an English gentleman of property. She

paled, and whispered that "she thought he was poor."

"And so I am poor enough to please you, I hope," he said;

"and besides, nothing can take you from me after to-morrow."

This confidence was one-sided, however, for Lilias feared to

speak of her relations. She had never set him right with

regard to her real name. The name he knew her by was Lilias

Lindsay still. And he had made her promise that she would keep

their marriage a perfect secret, and have nothing more to do with

her unkind, her heartless family. "There is nothing so bad as

half-kept secrets for getting one into trouble, and making one tell

a pack of lies, and there is nothing I hate like a lie," he said.

And Lilias promised. She would have promised anything

he had asked—poor, infatuated girl! and she let the precious

opportunity, which lasted but a moment, slip away. "He hates a

lie," she thought, "and he may think that I am false if I tell him

that I have another name."

Then she had been shown up-stairs into a little room at the

top of the tall house, and left for the night; not to sleep—she was

too excited for that—but to look out at a little window, out into

the cemetery, and on the white monuments standing distinct in the

moonlight.

More than once she thought of slipping out and running away.

But she loved this man so that the thought of never seeing him again

almost made her swoon with pain. It was more than she could

bear to think of. What were her mother and her sisters to her

now? They would soon cease to miss her. They did not

care for her enough even to make it necessary to write and tell them

she was happy. She thought differently by-and-bye; but now all

other love was dim and shadowy in the light of the passion which had

fired her heart.

So she banished such thoughts, and sat all night at the

window, looking on the signs and symbols of death, and musing on the

sweetness of life. In the morning she was married, and Mrs.

Watson lost her lodger, and was highly indignant thereat.

Christopher took Lilias away, and kept her till after Easter at a

pretty farm-house he knew of up among the Cumberland mountains.

And Lilias saw the spring come over the valleys, and rejoiced in the

spring. They were very happy in those early days, this

careless, heedless pair. Lilias was very deeply in love, and

Christopher Ward believed himself to be as deeply in love as she.

He was very fairly so, but such a love as hers comes only once for

all, and not to all, by any means, even once. It was already

beautifying her whole nature, clothing her with a new grace, the

grace of a lovely humility. It might end in purifying and

ennobling her, and it might destroy.

She strove to forget and to bury her past; but life is a

whole, and cannot be separated in this way. As the flame of

passion burned purer and clearer it threw a steadier light upon what

she would fain have hidden from herself, the sacredness of the ties

she had rent asunder.

Then they had come back to London, and settled down, and

Lilias had striven hard to give to their bright little dwelling the

sacred stability of home, a task that grew day by day more and more

difficult, as it became apparent to the shrewd eyes of servants that

there was something wrong somewhere. They could feel that some

kind of sanction was wanting to this union, and they jumped to the

conclusion that it was the legal one. The virtuous were shy,

the unworthy were obtrusive. More than once a servant went the

length of absolute insult, and was dismissed by high-spirited Lilias

on the spot. But her spirit was forsaking her in view of such

petty torments going on endlessly. They made another reserve,

too, between her and her husband. She could not tell him that

he had placed her in a position which she found untenable. And

oh that promise! If she could only have written and told her

mother that she was married and happy, it would have been a

consolation. But she was strangely timid with Christopher.

She would sit at his feet sometimes with her wonderful hair sweeping

the floor about her, looking like another Magdalene, so sad was her

averted face, trying vainly to summon courage to speak.

A year after her marriage a little daughter was born, and her

bliss and her pain culminated together. Had her mother ever

loved her as she loved this little morsel of humanity? How

should she bear it if these little hands in the time to come should

never clasp hers more, if these little feet should depart from her

wilfully for ever? Many were the tears she shed over the

unconscious face that nestled in her bosom. But more and more

impassable was the barrier between her and a return to perfect

sincerity of life. How could she look in the face of her

child's father, and tell him that she had all along been heartless

and false? No, she could not. She suffered in silence,

and when she went about her daily life again she felt that she must

bear her burden to the end. She lived but for her husband and

her child. Even the best of wives and mothers own some

distractions, social or otherwise. Lilias had none. Her

life was too concentrated in deed to be healthful, and she was

becoming far from strong. The child did something for her.

It necessitated greater activity, and she loved to walk out with it,

and have it continually in her sight, to its nurse's extreme

discontent. But for that daily walk she saw little of the

outer world. She never murmured that her husband went into

society from which she was excluded. He was too generous and

affectionate not to strive to make up to her in every possible way

for the isolation she suffered. Every autumn he took her away

to some place of his own choosing in Scotland or Wales, and stayed

with her there in peaceful seclusion.

And Lilias would forget her false position and the

difficulties it entailed, and become once more tenderly gay.

Then little Lily would bloom afresh, not only with the out-door life

and the added freedom, but as if she sympathised in the freer moral

atmosphere, and drank in new life from the happiness of those about

her. Never were parents blessed with a sweeter child.

She was not in the least like either of them, nor could either see

in her any likeness to any one they knew. They were fair and

she was dark, at least her hair and eyes were, with a shadowy, not a

brilliant darkness. They, at least Christopher, was robust;

she, as she grew older, was more and more fragile.

It would have been difficult to say whether the father or the

mother's love for this child was the more intense. Christopher

was the most indulgent of the two perhaps. He had an uneasy

feeling that the child was losing something, that as his child she

ought to have had something of consideration and association with

other children.

Life would have been different to Christopher but for that

false step of his; very different, both to him and Lilias. He

would have given much to be rid of the weight upon his heart,

especially whenever he happened to be the companion of his now

fast-failing father.

Christmas was the time he dreaded because of this. It

was the saddest season for Lilias too. Then her husband was

sure to be absent, and she would have been hardly a flesh-and-blood

woman if she could have forborne in her loneliness many a jealous

pang.

"I don't like Christmas, mamma," said little Lily, evidently

feeling the influence on her mother's spirit, and also full of

certain conversations with the maids. "Do other little girl's

papas come and kiss them on Christmas morning, and bring them pretty

presents?"

"Sometimes, my darling," answered Lilias. "Your own

papa has sent you a pretty present in a box—a real

Christmas-box—which you and I will open, and perhaps find a lovely

new doll."

"But, then, papa will not be here to see," objected the

child. "Where is he gone, mamma?" she asked, suddenly.

"To see his friends, darling."

"And have we no friends, mamma?" asked the child, sadly.

"If Lily is a good little girl," replied the mother, sending

back her tears by force upon her aching heart; "if Lily is a good

little girl, papa will take her to see his friends some day."

"And mamma too?" said the child. "May I ask him?"

"No, darling, you must not ask him. You must wait till

he is ready."

There was nothing the matter with the little darling—nothing

that could be named. She never complained; but she got thinner

and thinner, and there was a failure in her small appetite, and a

proneness to fatigue on the least exertion, which woke an anxious

fear in her mother's heart. They took her to a celebrated

physician, and he said there was certainly a want of vitality, and

prescribed change, fresh air, a visit to the coast, and plenty of

milk to drink. Thus it was for the sake of their child that

Lilias and her husband had come down to the sea-side within easy

distance of London. But Lilias herself was far from strong.

And that repulse of her sister's had wounded her deeply,

though she tried to think it was well that her advance had not been

met. A depression which she could not shake off seized upon

her. Christopher could only remain for a few days, and though

she was grieved at his going, she was glad to be alone, that she

might give vent to her bitter grief

But she was not alone. There was little Lily clinging

to her with wistful sympathy, reading her face, and reflecting its

most mournful expression. For the child's sake she must rouse

herself, at least in the day-time. In the night she might weep

unrestrained.

It was a sad, lonely house to which they had come, directed

by the people of the hotel when they had asked if a lodging could be

found at some little distance from the town. Its owners were

reduced gentlewomen, who rendered themselves invisible to their

lodgers, and for that matter the only servant might have been a

reduced gentlewoman too. The house stood away from a tiny

village, in the midst of a neglected garden, which had on one side

for a wall the moat of an ancient ruin. All round stretched

the green flats, bordered by the grey sea-sands, with here and there

a solitary fort. It was a bad exchange for the cheerful little

town on the first slope of the cliff.

But there Lilias and her little daughter stayed week after

week. One servant had been left at home in London, and one

Lilias had brought with her chiefly to wait upon the child; and she

would send oft the two to ramble in search of wild flowers, while

she herself sat on some point of the ruin looking out mournfully

over the dreary scene, for dreary it ever seemed to her then and

afterwards.

Christopher came down once or twice, for a day or two, and

went back to town again, and once or twice he wrote to say he was

disappointed of a visit by being asked to go home. His

presence there was often called for now, for his father's health had

latterly begun to fail. Not that, as yet, there had been any

anxiety on his part, but the old man was fading, and Christopher was

his favourite son, and many a pang it gave him to meet his father's

confidences with his own silent deceit and acted lie.

And during his absences Lilias would feel more wretched than

ever; for then, though he wrote to her, she never answered him.

She was in that condition of bodily illness so much misunderstood

and so much abused, called nervousness. All sorts of sick

fancies came into her head. Her time of happiness was gone

past. Her husband's affection was becoming cold. Her

child, her little angel, was about to be taken away from her.

Perhaps she would sicken and die while her father was absent, and

could not be recalled. Sitting among those ruins she seemed to

see around her the ruins of her life, and only a barren waste of

existence stretching on before her, grey and desolate, and haunted

by the memories of the past.

At length Christopher came down to stay, and to plan their

usual autumnal excursion. He thought of laying hold of some

little vessel, and, sailing across to France, make their way to

Étretat. Lilias revived, and as if the child really brightened

with her mother's smiles, and drooped under her mother's sadness,

little Lily was in the gayest spirits. Christopher himself

seemed the least happy of the three.

And just when they were ready to start a letter came

recalling him. His father had become suddenly worse. The

family physician had desired a consultation, at which his father

requested him to be present. Thus called, Christopher hurried

away to his home in the West of England, leaving Lilias once more

alone. He was present at the consultation, and heard the worst

actual and anticipated. The worst anticipations might be

warded off for a time if they could succeed in arresting the

progress of the disease. But the result, though it might be

delayed, could not be averted, and it was a fatal one. Day

after day Christopher stayed on, unable to leave his father.

It was his annual holiday time; and when at length he returned to

the lonely house by the shore, it was only to bring Lilias and the

child back to London. His father had rallied a little, and his

holiday was at an end.

On this occasion Christopher had made up his mind to tell his

father of his secret marriage, and beg his forgiveness, only he

desired to prepare Lilias for one of two results, either an angry

repudiation of his relationship, or a complete forgiveness, in which

case his father might desire to see Lilias and the child

immediately.

Christopher had returned from the City. He had dined,

and Lily had sat beside him as usual, and chatted all through the

meal. He could not wait for her till dessert. Then he

led her into the drawing-room; and the three established themselves

for the evening.

Lily then spent her happy hour with papa, and went off with

her maid. The room was hushed, only she seemed to leave behind

her a sweetness in its atmosphere. Lilias had been lying

listening to their prattle, and had only risen from her sofa to give

little Lily her good-night kiss. Her husband took up his book,

and very listlessly Lilias laid hold of the day's paper and began to

glance at it.

But the peace of the evening seemed destined not to last.

It was broken by a furious ring at the outer bell, which had not

ceased tinkling after the peal when a servant entered with a

telegram. Christopher seized it, tore it open, glanced at it,

and ordered a cab before the girl had gone out of the room.

"It is from my mother," he said to Lilias, who had turned

away her face. "My father is dangerously ill—cannot survive

the attack. There is not a moment to lose," he added, looking

at his watch. "I must go home without delay."

Lilias rose, and would go and see his things put up, but he

prevented her. He had just time to catch the last train, and

he would only put up a few things in a bag; the rest could be sent

to him.

"I fear it will be over before I get there, from the words of

the telegram," he said, coming down bag in hand, and ready to start

in less than five minutes. "And, Lilias, you must be prepared

to come to me the moment I send for you. I can't stand this

any longer, and I shall tell my father all about you if he is able

to bear it."

"Oh, Christopher!" cried Lilias, "I am so glad." Then,

to his astonishment, she burst out weeping. She had just

remembered her own fatal falsehood.

He tried to soothe her, but she would not be comforted.

"Can you forgive me, Christopher?" at length she sobbed. "When

you married me I did not give you my real name."

He stood back and looked at her in amazement. "You gave

me a false name?" he cried, fiercely.

"No, not a false name, only not my whole name. My name

was Lilias Lindsay Haycraft."

"My God, what have you done!" cried Christopher, turning pale

in his turn. "Married in a false name! Do you know that

you are not my wife, and that your child is illegitimate?" He

believed it. His hot blood was up. "False in this, you

may be false in all."

"That was just what I feared," she answered, wonderfully

calm. It was the calmness of despair. There was nothing

now to fear. The worst had come to pass, and nothing could

hurt her more. "Don't blame me more than I deserve," she

added. "I did not give you my full name at first, and I had

not courage to set it right, lest you should say what you have said

to-night; and how I loved you then."

She turned from him as if she made this last appeal to other

than him.

The servant announced the cab.

"I would go and leave you free," she said, "if it were not

for the child, for you do not care for me now."

"I care for you more than I ever did," he answered, but the

tone was a bitter one, "only you have done me and your child an

irreparable wrong."

"Oh, now I see how I have been punished, Christopher.

Spare me," she cried.

"Lilias, I shall lose the train. I must go."

He paused an instant in the hall, looking as if he meant to

spring upstairs and have a look at the little one, but he denied

himself, and hastened away.

He was forgetting to say farewell to Lilias. Little

things appear great at such moments. She stood the picture of

despair, when he turned and kissed her hastily and was gone.

Left alone to brood over her error, and the terrible,

unforeseen penalty which her husband had told her attached to it,

Lilias's unhappiness may be imagined. The night on which

Christopher left her she spent in sleepless misery, and complete

prostration followed. She sat all day when no eye was upon

her, with bowed down head and hands idly folded. Her little

girl laid aside books and playthings, and crept to her side,

drooping in sympathy.

Next day a letter came from Christopher telling her that all

was over. His father was dead. To the heated fancy of

Lilias the letter was cruelly cold, and she wept over it long and

bitterly.

"Papa is not dead?" said little Lily, trying to comfort her.

"No, my darling. It is his papa."

"And your papa?"

"Is dead, too."

"Everybody dies," sighed the child, with an anxious look.

"Will my papa die?"

"Not for a long time, I hope, darling; not till you are quite

grown up."

"And will you too, mamma?" and a spasm of fear contracted the

child's brow.

"Some day, my love," Lilias whispered. "When I am grown

up?"

"I hope so."

"Oh, mamma, I don't want to grow up," cried the child,

clinging to her. "I don't want to grow up and have no papa and

mamma like you."

"But you would not like to leave me, Lily, even to go to

God?"

"No, mamma. And where do people go when they die,

mamma?"

Sooner or later this question comes to the lips of every

child. "To God, my darling," whispered Lilias, softly.

"But I do not know God, mamma," came from the childish

mouth—a gentle whisper, and yet as the hammer that breaketh the rock

in pieces.

With humble and contrite spirit, Lilias tried that highest

task which falls to earthly parent to make her child know something

of the Father in heaven.

On the following day she had little Lily dressed, and taking

her out with her, she called a cab, and ordered the driver to set

them down at the corner of the road where her mother had lodged.

The desire to see her mother and sisters, and to be reconciled to

them, had become an uncontrollable longing.

It was a bitterly cold day. A cutting east wind swept

the hard grey road. Lilias took her little girl's hand, and

walked along it. She passed and re-passed the house. At

length she found courage to inquire. She remembered the name

of the lodging-house keeper, and inquired for her. No such

person was known there. The same answer was given by the

dwellers on either side. They too were strangers. Bound

by no social ties, loose as the drifting sand of the desert, further

search among these dwellings seemed vain.

Lilias, however, accosted an old milkman, whose form she

remembered, passing along the road with his basket of addled eggs on

his arm, and his pail of milk and water, or worse, in the other

hand. He had stopped in front of a house with his shrill mew.

And the old man, who had been there for years, did remember

something, owing to his daily gossip with the servants. The

people had gone away, he knew not whither.

Lilias looked down at her darling, and saw that she shivered

and seemed fatigued.

Anxiously she hurried back to the cab, and ordered the man to

drive home. "Lean on me, love," she said to the tired child;

and she put one arm about her and drew the little head upon her

breast. There, as the cab rolled on, little Lily fell into a

kind of sleep. Her mother never lifted her eyes from the still

face. The child was very pale, the tender shadow under the

eyes had deepened. The dark lashes rested on it. The

delicate eyebrows seemed traced on alabaster, and the blue veins

showed through the transparent temples. What did the mother

see there besides to stamp such a look of dread upon her face?

But when the child looked up, with the stopping of the

vehicle, that look had changed. Her mother's face bent smiling

over her. She was led cheerfully into the warm drawing-room,

and undressed by her mother's hands. "I must not take you such

a long way in the cold weather again," she said. "You and I

must amuse ourselves at home."

They dined together early, Lilias watching every morsel her

darling ate. A mouthful or two of chicken, a few spoonfuls of

a delicate pudding was all she could manage. What would Lilias

have given to see her with the appetite of many a labourer's child

fed on bread and bacon?

In the afternoon, what with the warm room, and her mother's

exertion to amuse her, little Lily became quite lively again, with

the gentle sportive liveliness peculiar to her. Her colour

became even brighter than usual, and she shared her mother's tea

with zest.

Lilias went up stairs with her at bed-time, and saw her

undressed by the nursery fire, noticing how attenuated was the

slight frame. Then she heard her say her evening prayer,

kissed her tenderly, and left her to sleep. Then she went down

stairs, changed all at once from the smiling, winning mother, to the

woman whose heart is nigh to breaking. She took off the stern

restraint which her love had imposed, and abandoned herself to

sorrow.

But weeping cannot last for ever. She wept herself as

calm as a statue and as white, and as she wept there fell from her

the last remnants of falsehood and fear, and there came to her the

longing which fulfils itself only in a divine reconciliation.

Then, late in the night, she sat down and wrote a letter to Harriet.

It ran:—

"DEAR, DEAR

SISTER,—I cannot think

you will spurn me when you know all—all my sorrow for doing as I

did, and all my longing to see you again. I am not what you

think. I am married, at least till yesterday I believed I was,

and I know I am in the sight of God, though my own folly and

wickedness has led to some illegality. But I can explain this

when I see you. Dear sister, for the sake of old times, come

to me or bid me come to you.

"Yesterday I tried to find our mother, but failed. I cannot

think that she has gone where I can never tell her how deeply I

repent every sorrow I have caused her. Let her and Maria know

where I am. I have one little girl, whom I love so much, that

if she were taken from me I think I must die, and she is so fragile