|

[Previous Page]

THE PEARL

CHAPTER I.

"MAURICE

MACDONALD will make the

most of it, of that I feel sure," said a friend, discussing the

prospects of three or four students of our acquaintance.

The "it " was nothing less than the life which stretched before us,

full of varied prospects of usefulness, ambition, pleasure.

"No thanks to him," said another, "so much of it has been made for

him. He is rich. He has only to choose the best and the highest, and

to find every furtherance in his choice."

"But he loses the stimulus to exertion," said a third.

"You do not know him," was the rejoinder. "He has stimulus enough in

himself. He sat beside Andrew Home the other day in class. You know

Andrew, a good, solid fellow, with lots of head. What a contrast

they presented! Andrew looked like a figure cut in freestone. Not a

fold of his sandy hair seemed capable of motion. But Maurice — the

professor played on him; every nerve of his face moved, dashed,

quivered. The very hair of his head seemed stirred with a

spirit-breath."

It was a graphic description. Maurice Macdonald was of all things a

man — alive, alive to the finger-tips and hair-points — with eager,

seeking, searching, sentient life.

His father was Scotch, an adventurer in the good and noble sense of

the word, a sense now nearly lost. He had come up to London, entered

a merchant's warehouse, saved, and set a-going enterprises of his

own, till he had become a great Russia merchant. He was not a

scholar, yet he was a man of education, travelled, polished,

public-spirited. He had married an English lady, who had died

leaving him a son. Again he had married, but without any accession

to his family. Maurice was still his only child. He had bestowed on

him a liberal education, and had sent him to one of the Northern

universities, believing strongly in the physical and moral if not

intellectual hardihood of the North.

The moral atmosphere was certainly bracing. The greater number of

Maurice Macdonald's companions were more distinguished by poverty

than by wealth. They could not indulge in pleasure, for pleasure is

more or less costly; and, setting aside the mere boys, who took what

pleasure they could in rough boyish fashion, they indulged in study

instead. There were young men there from remote parishes (studying

theology and medicine), who would go back, when the session was

over, to the farm, the shop, or the sheep-fold, to lend helping

hands to the toils that enabled them to devote themselves to

learning; some of them destined in after-time to raise the whole

religious thought of a nation to higher levels, some to diffuse, by

new discovery, a world-wide healing.

The students were poor for the most part, for in Scotland the path

of learning, from the bench of the parish school to the chair of the

professor, is open to all. The ambition of the true Scottish mother

is for a son in "the ministry" — the Church. Learning is loved and

honoured in the humblest homes, and that very love and honour has a

refining influence there. In our own day the son of a cobbler has

preached before the Queen. A baker's apprentice was the discoverer

of chloroform; and, later, a little low-browed shop in a tiny

fishing town has sent three Senior Wranglers in succession to one of

the two great English universities.

These had their work laid out for them, and were in earnest about it

too; Maurice was one of the few who might rove at will over the

whole field of knowledge, and he did. Everywhere he was attracted in

search of truth, not the truth of this or that science or philosophy

only, but THE TRUTH, that which gives to each science and philosophy

its highest import, and unity to all.

With the chemist he studied the subtle mixing of the elements,

almost justifying the guess of the first philosophers of ancient

Greece when they resolved the world's wondrous whole into air or

water. With the geologist he examined the testimony of the rocks,

and learnt how the foundations of the earth were laid. With the

botanist and the zoologist he scanned and classified its vegetable

and animal products, and with the anatomist entered into the still

more sacred mysteries of life. And all with an eagerness

unsurpassed, a fervour of spirit which nothing seemed to daunt or

weary. His very teachers felt his presence inspiriting. Hardly one

of them could see the fixed beautiful face turned up to the rostrum,

or the thoughtful head bent over the rapidly-filling page of his

notebook, without even unconsciously responding to the eager

scholar. More than one of these teachers were, besides Christian

men, men who brought to the science of which they were masters the

simplicity and humility of childlike faith, and who saw the hand of

God in all his works, the greatest and the least. These looking on

Maurice Macdonald loved him, as Christ himself looked on the young

man who was rich like him and had kept himself so pure.

For Maurice Macdonald was not a Christian. He had not been led to

profess Christianity, otherwise he would not have contented himself

with mere profession, he would have carried into it the same eager

searching spirit which he carried into everything else, and might

thus have arrived at "The Truth" by a nearer way than that which he

had entered, that maze of knowledge in which many wander weary and

heavy-laden to the end, never reaching (while we can hear their

voices) that home of the spirit which is set in the midst.

Maurice had not been brought up in a Christian home. What the mother

who had died so young might have been he did not know. He had often

thought of her, looked on her miniature, and wished that he had had

the lovely living face to gaze upon instead. He had longed for her

affection when the want of such affection had made itself felt in

his heart. He had even fancied her looking down upon him from

heaven, which was very unphilosophical of course, only he could not

help the fancy; but this was all. How she had thought and felt,

believed and lived, he never asked himself.

And his father explained nothing. He was one of those men who

explain nothing — not even themselves. He spoke and acted very much

as other men in his position spoke and acted on the ordinary affairs

of life. But he gave no key to his thoughts; the purely practical

side of his character was always towards you. You had an idea — at

least, people of a more spiritual metal had an idea — that the man

was solid. It might be that the shaped and polished block was a

casket; in that case there might be jewels within, or only musty

parchments — title — deeds to a great estate, or old love-letters —

no one could tell. He spent money on art, but you could not tell

whether he really cared for art, or did it because other people

cared for it. He worked for the public weal, but whether from

benevolence or expediency, it was impossible to say. He held himself

aloof from churches and sects — would name himself by none of their

names — Protestant or Catholic, Trinitarian or Unitarian. Such

was Mr. Macdonald.

And the friends or acquaintances whom he gathered about him were all

what are called practical men — men who did not trouble themselves

with any theories about themselves or the universe; practical

politicians, who believed that happiness consisted in the greatest

good of the greatest number, as far as meat, drink, and other

purchasable things were concerned, or perhaps only to the extent of

the greatest number of Englishmen; political economists, not of the

new school, who calculate in moral values, but of the old material

type — such were Mr. Macdonald’s chosen friends.

True, with school and college his son had seen little of

either father or friends; but the home atmosphere had been imbibed

in childhood, and his father, in choosing for him teachers and

tutors, had, without exactly meaning it — though that too is

doubtful — excluded the religious element. It may appear

strange, but it is true, for all Maurice Macdonald knew of real

Christianity he might have been born a Greek or Roman of the first

century. Of course, historically and socially he knew all that

was to be known — the life of its founder, the divisions of its

adherents, but of its spiritual aspect nothing at all.

The home to which Maurice was about to return was pagan to

the core. The wife whom Mr. Macdonald had married made no

scruple of acknowledging her infidelity. Mr. Macdonald himself

acknowledged nothing, neither belief nor unbelief, but she was an

avowed Sadducee. She would turn upon you her large dark eyes —

she was a very pretty woman, though her beauty was of a fleshly type

— and quite gently and quietly put aside all reference to spiritual

matters with a "You know I don’t believe in anything of that sort."

And yet she would have been full of melancholy apprehension if a

single black crow had crossed her in her morning walk. An

additional black crow, however, reversed the decree, which was

fortunate.

Towards the close of his last session an incident occurred

which formed a turning-point in Maurice Macdonald’s career, though

it did but send his thoughts running in another channel. The

chemistry professor became ill, and unable to conduct his class;

friends supplied his place. His students missed and lamented

him, and went on as usual, but Maurice came to a dead stop.

Maurice had not only loved the teaching, but the teacher. His

whole heart had gone out to this man; why he could not tell.

The professor was a man of genius, but that would not account for

it. There were men of equal if not greater genius at the

university, for whom he did not care at all. There were even

more genial teachers; for the professor was by nature shy and

somewhat reserved; but for Maurice he had an unaccountable charm.

His voice, his eye, his smile, thrilled him with pleasure.

The young man called once to inquire at the

professor's house, and was sent away sorrowful. The professor's

state was very precarious. Though not hoping to see him, before

leaving town Maurice called once more; but on this occasion he was

asked to come in. Hearing of his last visit, the professor had

desired that if he came again he should be admitted.

He was admitted into a very plain room on the ground floor, about as

well furnished as the servants' room in his father's house. The

professor lay upon a couch at full length, with his head raised on a

horsehair cushion. A brown rug covered his limbs. There was no

attempt to make anything bright about him. Even the fire, a necessity

in the cold Northern spring, was smothered with ashes. The only

bright spot in the room was the sufferer's face. That was radiant

with a light from within, as he took the

hand of his student.

"I am glad to see you, Macdonald," was his simple greeting.

"And I — I hope you are better?" Maurice was strangely moved.

The professor shook his head. "Not much of that," he said, "my

general health is improved, but" — he looked down on his

outstretched limbs — "these are as bad as ever. I fear I shall never

walk again."

A hot flush of pain spread over Maurice's face. He could not speak.

"I have often thought my brain might go," continued the professor,

"but I never thought of my legs. I shall have reason to be thankful

if it rests with them. Ah! you may think this room a prison, but

the body itself may become a closer prison — a prison more terrible

than was ever devised by man's worst imaginations. I have seen it in

my own family. I have reason to dread it for myself. Think of having

organs of speech and being unable to utter a word, or even give a

sign, to those waiting to catch it! I have not come to that yet, you

see." He was speaking quite cheerfully. And then he turned from the

subject altogether, asking, "Do you mean to go on with your studies,

Macdonald? I think you said once you would not enter any

profession?"

"I do not know," answered Maurice, for the first time in his life

feeling the worthlessness of all his knowledge. "My father desires

to initiate me into business. I don't know that I shall care for it,

but at any rate I shall have leisure for something else."

"What have you been doing with yourself?" asked the professor,

kindly, but with a searching look. He was struck with the difference

in the young man's tone, and unaware that the change had taken place

since he entered the room. "You are not usually so little in

earnest."

"What is there worth doing," Maurice longed to say, "in the face of

a liability like this? What is there worth knowing? — except,

indeed, it were the secret, impossible and unattainable, of

reversing the decree of nature by which it is imposed." And if he

had said this, the professor would have answered, "Or that other

secret, neither impossible nor unattainable, which reconciles to its

infliction." And if Maurice had asked further, "What is this?" he

would have answered, "Faith!" He would have bowed his head and

answered, as he had answered to his own soul in its sorest conflict,

"Faith in God the Father, and in the Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ."

But Maurice did not say what he longed to say, instead of it he

smiled, and said he had been dissipating in Edinburgh society, and

was idler than usual.

And the professor, who was anything but an ascetic, told him that

that was no excuse, and that having played heartily, he ought to

work all the more heartily. Then he pressed upon him the importance

of a particular vein of thought which he had entered upon with his

class, and urged him to continue working it out.

"Your doing so is all the more important that you are going into a

new sphere. You will be sure to bring new ideas and new ways of

thinking to it," he said; and at parting, "Mind you keep up with

us!"

"Keep up with us!" Then he meant to go on. Knowledge, the merest

grains of it, were still of value to him. It was incomprehensible to

go on unless it was so. "Yes," thought Maurice, trying to account

for the fact, "knowledge is power, he can still feel that; but if

the worst comes, the state which he pictured, even that will cease

for him.

Thus he went on thinking, after he had bidden adieu to his friend

and teacher, and the prostrate figure, whose singular grace and

nobleness he had almost worshipped, haunted him in every avenue of

thought.

It was as if suddenly he had found himself behind the veil of some

mystery after which he had toiled and strained, and behold a heap of

ashes! He had in his heart a yearning which would not be appeased.

At one time he thought he would like to go back to the professor and

open his heart to him, offer to stay with him, give up his life to

him as disciple, nay, as a very servant, as limbs to him, as senses,

if these should fail. Then he laughed at himself, "Bah! a woman

might do this; women can do these sort of things." The only thing he

did was a thing inconsequent, of no consequence whatever. He was

wandering about in the east wind till his face was as grey as the

stones of the city, and he went into a florist's and sent the

professor a bundle of exquisite flowers. Then reflecting on their

perishable nature and the probable indifference of the man to whom

he had sent them — to Maurice himself they would not have been

indifferent, but a genuine solace — he betook himself to a

publisher's and sent him a pile of the newest books.

The professor guessed rightly concerning the books, that they were

the gift of a student, and felt a grater pleasure in their perusal,

beyond and above what their contents afforded, but concerning the

flowers he guessed wrongly. He was forty, the professor, and far

from rich; but for once in his life he was vain enough to suppose

that he was an object of special tenderness, and to single out the

subject of it — a thing which might have led to unpleasant

consequences, but that, with health and prospects such as his, the

professor could not and would not entertain the idea of marriage. He

must manage to let the lady know that he felt and appreciated the

kindness, however. So he had the flowers placed quite near him, on a

small table, and when he was once more alone, he put out a thin hand

and touched tenderly the cool, soft petals, fancied it must be like

the touch of a certain fair forehead, and he smiled as he closed his

eyes and repeated the process.

CHAPTER II.

MAURICE

MACDONALD'S

life was not one which could satisfy even moderately a character

such as his; even if it had been full of higher influences and

interests, it is unlikely that it would. He was by nature a seeker. The thirst of the soul consumed him, and the cup which alone can

slake it had never been offered to his lips.

A few months' eager devotion to business — he could do nothing

without being eager — and he knew as much as some would have taken

years to understand. He grasped the principles of a great trade, and

proceeded to master its details. Then followed routine, which is

only ordered industry, and calls for a power which is moral rather

than intellectual, and he set himself to that. He could see its

value, and was determined to acquire the power which it needed. It

was to him a difficult task, but this also he accomplished, only,

like a dammed-up river, the energies of his spirit burst forth when

the barrier was removed.

And the question was how they were to expend themselves. There was

pleasure, pure pleasure — for Maurice was one who sought for pearls,

and turned with a disgust which was absolute, in body and soul, from

the swine-trough of licentiousness — and the highest and purest

pleasures were within his reach. His home, though only a West London

mansion, was a perfect paradise of sensuous beauty. The soul of the

woman who presided there seemed to have taken refuge in her senses. She indulged in the most exquisite tastes. Exquisite art adorned the

spacious chambers, exquisite flowers bloomed there in fresh

succession as if they were immortal. Exquisite food, exquisite

dress, exquisite music awaited Maurice every evening. His

step-mother had a perfect passion for beauty, only "passion" does

not express her calm absorbing love of it. She chose her friends for

their beauty, just as she chose her flowers. She threw aside an ugly

or faded one without remorse. Plain girls were rigidly excluded from

her parties. No grace, no bloom, no freshness in the world could

equal those of the young English girls Mrs. Macdonald could gather

together. She never crowded them.

All this was not without its influence on Maurice, but his love of

the beautiful went deeper than outward beauty. Time after time, when

he lighted on a lovely face, he was attracted, but it was to seek

under it the beautiful soul of which it appeared the embodiment, and

time after time he was repelled. Levity repelled him on the one

hand, and inanity on the other. Doubtless some of those who repelled

him were good and sweet girls, who laid aside the levity and inanity

to a great extent with their evening dresses. It was the fault of

the society in which they moved that they appeared as they did, and

were in deadly danger of becoming what they appeared, vain,

frivolous, bold, unmeaning. The purpose of life set before them,

display and attraction, was eating into their hearts. Maurice judged

them harshly. He loved none of them, and yet his heart had become

conscious of seeking something to love.

Just at this time, when Maurice had been at home about a year, there

had dropped, or rather been dropped, from his step-mother's circle,

a young married lady, whose loveliness all had admired. The

beautiful reckless creature had been sorely sinned against as well

as sinning, and Maurice gave her a too perilous pity. They met by

chance. How tell the mournful story? yet in truth it must be told. "He that thinketh he standeth, take heed lest he fall." Maurice

fell. He entangled himself in a connection equally fatal to both,

for she had nothing to gain, everything to lose, in loving him. She

lost all for him, so he believed, and he would have given her all in

return if that had been possible. He would have married her; but her

husband, an old and cruel profligate, declined to trouble himself

about her. Her maintenance fell upon Maurice. She was frightfully

extravagant, and Maurice got into money difficulties. Disappointment

too had settled upon his spirit, for the false jewel he had bought

so dearly was gone, crushed into a pinch of dingy paste-powder. He

saw this woman as she was, shallow, indelicate g saw in her, with a

shudder of revulsion, an unclean thing. He was degraded in his own

eyes, degraded and in chains, for he could not set himself free. He

had a glimpse too, in those days, of a love that might have been

his. He had made the acquaintance of a gentleman whose family he had

not yet seen. It was difficult to see them, as they did not go much

into society, staying chiefly in the country, at a place of their

father's not far from London. Since they did not go to society,

however, society came to them; but it was a society selected by a

wise and good father. If he had known what there was to know of

Maurice Macdonald's life, he certainly would not have admitted him;

but Maurice interested and attracted him, and, for good or evil, he

brought him to his house for a summer holiday.

The holiday lasted only from Saturday till Monday, and Maurice was

the only guest. His host was bent on making his acquaintance — bent,

too, on a nobler aim. He saw in the young man, or thought he saw,

one who craved for higher things, one who would love the highest if

he knew.

And so far he was right. Mrs. Messenger welcomed him, and Maurice

longed for such a mother. She introduced him to her daughters one by

one, and he received a new impression of women. They led him into

the garden, and with Mary Messenger walking by his side he felt a new

sensation, thrilling, horrible — that is not too strong a word for

it — like that of the man without the wedding garment looking round

at the guest by his side. How pure, how sincere, how simple she was

in dress, in manners, in all things! There was a light upon her

loveliness like that in her eyes, which was true and sweet, which

was holy. In her presence he breathed a purer, freer air — the air

for which he had panted. It was the difference between his mother's

pent-up imprisoned exotics and this wide fresh English garden, with

its back ground stretching to the distant sky-line over miles of

bowery land.

Its effect upon him was to sadden, almost to sicken him with shame. He felt just as he ought to have felt, that he had no right there.

His face took an almost withered look. "He must be out of health,"

thought the mother, who had no son of her own, and she redoubled her

frank tenderness. "He is unhappy," thought Mary, and checked her

innocent gaiety to accord with his mood.

After dinner came music and the garden. A bell recalled them from

its moonlit walks, and the song of the nightingale in the little

wood beyond. It was the prayer-bell. The two younger girls went

toward the house one on each side of their father, Mary returned

with Maurice. He looked at her pure face, etherealised by the soft

light. He did not dare to offer her his arm. Her white dress brushed

him as they walked, and he could hardly help shrinking, as if the

contact might reveal him as he was.

They entered the house. Mr. Messenger led the way to a little

private chapel, where the servants were already seated. He took his

place on a slight elevation in front of them, and conducted family

service. It was the first time Maurice had been present at such a

scene. He knelt as they knelt, and hid his face in his hands. He did

not wish to appear absorbed in prayer, but his humiliation was

complete. Mr. Messenger used the prayer, "For all sorts and

conditions of men." In the pause he prayed for the stranger.

That night Maurice could not sleep, he was miserable. He sat at his

window looking out upon the garden, and saw the dawn. Next morning

he was looking haggard. Mrs. Messenger noticed it with concern. He

had better not go to church. She herself would stay with him. They

saw the others go, Mary by her father's side, the younger sisters

following, and sat down on the lawn under a great walnut-tree.

Maurice could hardly trust himself to speak. He would gladly have

laid his head on this woman's knees, and confessed to her what he

was, and been gone before her daughter's return. After a little talk

she went and brought out some favourite volumes and laid them on the

grass, and begged to be excused for a time. She fancied that he

wished to be alone. When she came back he had fallen asleep under

the tree.

She stood and looked at him pityingly. Should she wake him, and try

to win from him perhaps some unacknowledged sense of mortal

weakness? But the frame, though slight, did not seem diseased, and

the face, no longer worn and haggard, looked anything but sickly. At

length she resolved to let him sleep on.

And he slept soundly, serenely, under the broad-leaved tree, out of

which the warm sun drew aromatic fragrance. He was still sleeping

when the little party came back from church. They stepped over the

grass, and did not wake him, and Mrs. Messenger, keeping guard over

him now, put her finger on her lips. No one made the least noise,

and yet he woke. His eyes met Mary's first. She was clasping with

two hands her father's arm, and bending over Maurice with a gaze

half admiring, half tender, such as women bestow on a sleeping

child. He started up, flushed, smiling, apologetic, and for the

remainder of his stay was more like his old self, the Maurice who

charmed all women and most men. He talked with Mr. Messenger on the

graver topics of the day, treated by the latter from a far higher

point of view than any to which Maurice had been accustomed. And, to

his amazement, not only did the ladies form an attentive audience,

but Mrs. Messenger and even Mary took part in the conversation.

In the afternoon they walked, the afternoon sky having drawn over it

the delicious awning of cloud by which English skies make amends for

their frequent gloom, those grey and white clouds which are like the

wings of a dove for cool, soft shadow. In the evening they had music

again, Mary's music. She alone could do justice to the great master. The selection was from Beethoven, from his last and grandest

sonatas, and from the "Missa Solennis." After a pause — "I

never hear his music," said Mr. Messenger, without thinking of his

life — that he who created such harmonies was deaf to all. I think I

see him sitting apart, in his total silence, while the finale of his

Ninth Symphony drew down the plaudits of the musical world at

Vienna, till a friend turned his face to the audience, that he might

see the enthusiasm whose thunders he could not hear. I think I see

him turning, and the tide of applause breaking like a wave upon the

shore — the crowd bursting into tears before the old man's face.

What a piece of sardonic mockery that scene would be, but for the

faith which made his life a grander music!"

"But for faith!" the words echoed and re-echoed through Maurice's

heart, and somehow with the words came back also a vision of the

Scotch professor lying stricken in his prime.

Faith! Was this the key which would unlock the mystery of the

universe? Was this the jewel of life, the one thing worth seeking

and finding, worth giving up all to obtain? Faith! the substance of

things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen, as he had

somewhere read. Was that the light which shone in Mary Messenger's

quiet eyes, so different from other eyes he had known that they

seemed to belong to another world? He could not tell; but he yielded

himself to the influence of that home atmosphere, to him so strange

and sweet and new.

"I fear," said Mr. Messenger, when their guest had departed, "that

my favourite has not realised your expectations?"

"And yet he has raised them somehow," said his wife. "I should like

to see more of him."

"I like him very much indeed," said Mary, frankly.

"Then I will ask him to come again soon," said her father.

But Maurice was not destined to come again soon. His life had become

unbearable. His father must soon be made aware of his

embarrassments. He absented himself for a few days from home and

wrote to him, making a full confession.

Mr. Macdonald was seized, on the receipt of this letter, with a

passion which in him was rare. He had been seldom disappointed,

being a man of rare calculating powers, and he was proportionately

unable to brook disappointment. Maurice had disappointed him — he

had made a fool of himself that was the way in which he put it. He

thought not "the fair promise of his youth is blighted," but "my

faith in him is lost." He could not even make up his mind to write

to Maurice and put him out of suspense.

But Maurice's step-mother stood by him in the crisis, and served him

better than a mother might have done, because more dispassionately. She softened down offence, she made allowances; she was full of

kindness and sympathy towards both; she talked over her husband,

she wrote to her step-son, and really kept them from finally

breaking with each other.

Mr. Macdonald at length proposed an ultimatum. There was no need for

him, if he had but known, to pen that clause of the proposal

insisting on the breaking off of his connection, that had already

broken itself off for all time; but the ultimatum included a three

years' residence in Russia, as his father's agent, and an instant

departure from London. Maurice accepted, and was immediately

dispatched to Scotland to transact some business with a mercantile

house in Glasgow, previous to his departure for the country of the Czar.

He did not pass through Scotland without thinking of the professor,

and wishing to pay him a visit, but time failed him. He arrived in

Glasgow on Saturday morning, had only the day for his business, the

next for rest, and on Monday morning he was to leave the country for

his place of banishment. But the Glasgow merchant was rapid;

transacted the business, and whisked him off to his villa down the

Clyde on Saturday afternoon, promising to fetch him back again in

good time on Monday morning.

He was duly carried off to the kirk by the merchant and his maiden

sister; but in the afternoon he was free to take a stroll by the

seaside — so much was conceded to youth and a worldly upbringing. Taking his stroll in rather melancholy fashion, whom should he see

at some little distance but a man so like the professor, that he

watched his approach with the keenest interest. Of course it could

not be the professor himself. The gentleman had a lady on his arm

too.

But there was no mistaking the smile of recognition which lighted up

the professor's face, nor yet the hearty greeting shouted forth, on

a nearer approach, by the professor's voice.

"Macdonald! one of the last people in the world I expected to meet

here! My wife, Mr. Macdonald." With an exchange of hearty greetings

and sufficient explanations, Maurice turned and walked with them. He

would have been glad to spend the rest of his day in their society,

but that was impossible, so he made the most of the present.

Talking of books, a sudden thought darted into the professor's

brain. He stood still for a moment, and laid his hand upon his

companion's shoulder. "Did you send me a lot of books when you left

us?" he asked.

"I sent you a bouquet, I remember," Maurice stammered, blushing, and

trying to get out of being thanked.

The professor laughed. A look passed between him and his wife, and

then, not a little to Maurice's embarrassment, they both laughed

together.

The professor felt that some explanation was necessary. "But for

your posy we might never have been married. It was the missing link,

you know. I accused her of sending it — in short, it brought us

together. I am sure we ought to thank you — eh, Alison?" said the

professor.

Alison thought so too, and smiled, and hoped that Maurice would not

fail to visit them when he returned to Scotland. Then they parted at

the merchant's door, and the professor and his wife continued their

stroll upon the beach.

It was quite true that Maurice's flowers had brought about an

understanding between the professor and the lady whom he loved. The

day after they had been sent, she and her mother, the wife of a

fellow-professor, had called to see the invalid. The professor had

known Alison Scott in the shortest of short frocks. He knew all

women through her. Men know women mostly thus, through a medium, and

happy is the man who knows them through such a one, uncoloured by

affectation or envy, undwarfed by littleness or frivolity.

He would have thanked her for the flowers then and there, but she

bent over them till she almost brushed them with her lips, and said,

"How beautiful!" and he was mute.

Gradually he got a little better, and at length was able to be moved

to the seaside. The Scotts had taken up their summer quarters at a

pretty little town on the coast of Fife, and thither he had

followed. He got well enough to walk about on crutches, and took the

first opportunity of being alone with Alison to call her a little

hypocrite.

Alison looked uncomprehending, and asked the reason why she was

called such a shocking bad name.

"You know you pretended never to have seen those flowers before," he

had answered.

"What flowers?" she had asked.

They were sitting in a little wood that stretched along the shore.

The professor was resting himself and his crutches on a rustic seat

placed there for the public convenience. Alison was standing over

him, her back against a tree.

"What flowers?" she had asked, innocently.

"Why, those beautiful flowers you sent me when I was ill," he had

made answer. He thought himself well now by comparison.

"I never sent you any flowers," was Alison's plain matter-of-fact

statement. She wished she had sent him all she had ever had in her

life when she saw his face, the light gone quite out of it.

"Someone sent me some very pretty flowers, and I jumped to the

conclusion it was you," he said, in his most distant voice. He did

not mean his tone to be so very different to what it had been a

moment before; but he was chilled and disappointed, and could not

command it.

"If I had thought you cared —" she was beginning.

"It was not the flowers I cared for," he interrupted, hastily. "It

was that somebody cared enough about me to send them. I wonder who

did!" He seemed absent, speculating. When he looked up, Alison was

blushing crimson, evidently struggling with herself

"I would have brought you a cart-load," she said, bravely meeting

his eyes, "if I had known you would take it so."

"Ah, Alison, I am selfish, I fear! but I would not have you care too

much for me," he had said; "I am a cripple for life."

"As if that had anything to do with it, as if I could help caring

for you. I will never love any one as I love you," had burst from

the impetuous girl, "I never feel so good as when I am with you, so

happy as when I am doing something for you."

And so the professor had won a wife, a companion in health, a

comfort in sickness, one whose price he held to be above all rubies. And God gave him, as a foretaste of His kingdom, a few years of

earthly happiness as unalloyed as ever fell to mortal lot.

He and his Alison often wondered, when they went back to the city,

or took their well-won holiday in the summers that followed, what

had become of Maurice, whose profound melancholy had interested the

latter almost as much as his unconscious connection with the story

of their love.

And what was Maurice doing then? The three years were drawing to a

close. What had the seeker found in them? Was he still a seeker, or

was he satisfied at last? Much had happened in those years. Maurice

had led a life of incessant labour. Besides transacting the business

entrusted to him with energy and ability, he had reached forth on

every side in search of fresh enterprise; larger and larger

discretionary power had been yielded to him, as it was found always

exercised with prudence. From being the mere agent of his father's

house he had become its partner, and its most active one. His spare

time he had devoted to the acquisition of the difficult Russian

language. In this ceaseless activity lay his only happiness, for

happiness it was — no man can work heartily at any work worth doing

without enjoying a certain amount of satisfaction. But his heart was

empty, there was the "aching void" within.

He was desperately alone; the cultivated young merchant was offered

the entrée into the gay society of St. Petersburg, but when

he accepted invitations to its gatherings he only felt all the more

keenly his utter loneliness. When he went abroad in the city or its

environs he envied poor men's joys, so he sat oftenest solitary,

learning or working, brooding over vaster and vaster schemes.

Towards the close of the three years his father died, and he was

recalled to England to take his place at the head of the concern,

now one of the greatest in the country. It was an enviable position. With a princely fortune, it conferred princely power, far more real

power than falls to the lot of princes nowadays. A scrap of writing

fell from his hands, and hundreds on hundreds, whole villages, whole

towns, set to work to execute an order; another scrap, and they were

fed and clothed, they and theirs provided for by the labour of other

hundreds. But Maurice was not to be envied; his father's death had

still further saddened him. He had died as he had lived, shrouded in

unbroken reserve. The casket remained sealed for ever. When the news

of his sudden death reached Maurice he could hardly realise it. He

went to his desk and took out the last letter he had ever received

from him. There were the brief business-like communications about

business matters, the equally brief and formal acknowledgment of

their near relationship at the close. Was it possible that the

correspondence had ended? that all communication, as far as this

world was concerned, had ceased? As far as this world was concerned!

Was there any other world? He could not answer, not even with an

undoubting "No."

Very soon after his return he renewed his acquaintance with the

Messengers. On the occasion of his first visit Mary was there — he felt his heart thrill as his hand met hers. Vain regret and

humiliation filled his soul.

It is the fashion of the world to make light of such a sin as

Maurice had been guilty of especially when it is a thing of the

past, to pretend that it thinks hardly any the worse of a man for

it, and that a man need not and does not think any the worse of

himself for it. Away with the vain pretence! Sin is of the soul, and

stains as deeply the man's as the woman's, if he is more callous

over it, that is only a proof that it has hurt him more. But Maurice

did not think lightly of it. He felt degraded, humiliated, lost as

ever any fallen woman did in the presence of spotless womanhood. Such a feeling has driven many a man out of such presence, and into

that of womanhood anything but spotless, till perhaps callousness

was attained.

CHAPTER III.

A FEW months

after her husband's death, Mrs. Macdonald began to show symptoms of

declining health. That death had been a great shock to her — the

first profound alarm she had ever felt, though she was no longer

young. She had had neither brothers nor sisters, nor any children,

to realise the truth that—

|

"All tenderness

In human hearts is guarded by a fear." |

She had led a life unusually free from trouble and sorrow. Her eyes

had never been dimmed with weeping, nor her cheek paled with

watching. She looked ten years younger than most women of her age. But since her husband's death she had worn a strangely haggard look. She was restless and unhappy in her enforced seclusion. She hated

the gloomy garments which she felt bound to wear; but far more she

hated and longed to rid herself of the thought of death. She was

constantly going over in her mind the actual physical horror of it,

rehearsing the last scenes of the tragedy; the failing breath, the

closing eye, the stiffening limbs, the rigid marble features, the

closing coffin, the everlasting farewell. No wonder Mrs. Macdonald

looked haggard and worn. She had sedulously kept aloof from disease

and death, guarded herself against horrors of all sorts, and lo! the

worst of horrors had invaded her, come close to her as her own

garments, dwelt with her, and would not be sent away.

But for Maurice's presence she felt she could not have endured those

first months. If he had been her own son he could hardly have

treated her with greater devotion and tenderness, and his tenderness

was real, not apparent. She had been very good to him, and he had

learnt to love her long ago. Then she was the only one who knew him,

and she loved him still. They had planned to go away together, and

spend a month or two abroad, when Mrs. Macdonald became so much and

so rapidly worse that the plan had to be given up.

A fashionable physician was called in, and, having received a hint

of his patient's state of mind before the complete prostration which

he witnessed, he prescribed, along with his powerful tonics, a

constant cheerfulness and ease of mind. Mournful and pathetic were

the efforts made to obtain these precious things in that wealthy and

luxurious household. The gloomy garments were laid aside. The

invalid was attired in virgin white, in spite of continued and

increasing weakness, her toilette was as elaborate as ever. Whatever

could tempt the palate was set before her. The fairest flowers, the

choicest pictures were brought into her rooms. The most tasteful

trifles were elaborated to please her. Friends were called in, and

responded to the call, to chat and trifle with her. All was of no

avail. Nothing continued to please, nothing satisfied.

At length it was evident that the struggle was one between death and

life. It was death that prevailed. With all her faculties

unimpaired, with her love of life in full force, this woman learnt

for she was not to be deceived — that she was about to die, and

then, and not till then, she managed to rid herself of the thoughts

of death. She summoned all her resolution; so long as she did not

feel the hand of death upon her, so long she would hold out.

She made Maurice promise that he would not even see her when that

hour came, or look upon her face in death. "It is unpleasant," she

pleaded, "and I do not like to be unpleasant."

She was very brave, but she had to do with the king of terrors. When the end came her cries resounded through the spacious mansion.

The awe-stricken servants clung together in the passages, and wept. When Maurice came back from the City, early, because of the state in

which he had left her, he rushed up to her, forgetful of his

promise, forgetful of everything but her extremity. She turned her

dying eyes upon him. He will never forget their look! He will never

forget that hour! Its shadow stretched

across his life.

He caught the trembling hands, and held them in his own, and her

cries ceased, but her eyes were fixed upon his face — hopeless and

imploring. Strangely enough his first impulse was to pray, and he

would have prayed had he known how; but he did not. Sending forth a

form of words into the unknown he knew was not prayer, but

incantation. So he stood by her side through the long dumb agony,

and strove to sustain her, till his knees knocked together and the

sweat stood upon his forehead.

When it was over, and he was released, he stumbled down the stairs

and fell fainting at the foot.

The sadness of Maurice's life had deepened still more. He fell ill

of a nameless disease, whose symptoms were languor of all the

functions. Doctors sounded him to find out the seat of it, and all

alike pronounced heart, lungs, and every organ sound. No disease was

discoverable, only a general want of tone. He felt old and weary. He

had an utter lack of interest in life, nay, rather an utter distaste

for it, looking upon it as a painted prison from which only a

terrible release awaited.

The physicians sent him away in search of health. He went, hardly

caring whither.

It was autumn, and he turned northward into Scotland. It struck him

that he would like to redeem his promise to the professor, and see

him once more after the lapse of years. Perhaps he too was dead. To

Maurice, in his present mood, it seemed most natural that he should

be. It seemed more natural to die than to live.

But the professor was not dead, nor was it difficult to find him. From the capital he traced him to the little Fifeshire town where he

had taken up his abode. His house was a small freestone cottage set

on a little hill, and looking down on a narrow strip of wood along

the shore of the firth.

"Laid up again, you see," was the professor's greeting.

"I grieve to see it," replied Maurice. "Is it the old disease?"

"That and worse," was the answer given, cheerily. "The enemy only

invaded a small portion of the territory last time. He is marching

on to the final conquest now."

"Yet you do not seem unhappy. You look more cheerful than ever,"

said Maurice.

"Why, what an ingrate I should be to do anything else! Just look." He waved his hand towards the open window.

Maurice looked, and saw a lovely prospect. The silver firth, the

glittering shore, a fair city lying in the embrace of the hills.

"It is very beautiful," he said; "but, pardon me, what is it to you? It is to me at this moment nothing."

The professor raised himself a little on his elbow — it was but

little he could raise himself now.

"You are neither blind, deaf nor senseless in the body, and

therefore, Macdonald, you must be suffering from disease of the

soul. Feel that breeze coming in at the window," he added, waxing

eloquent, "to me it is the very breath of God. Nothing! why, in at

every gate of sense streams a perfect flood of joy."

"Yes," replied Maurice; "but in at these gates come also pain,

horror, darkness, corruption, death."

"My dear fellow," exclaimed the professor, "what a fearful shadow

you are casting! You must have turned your back upon the light."

"Forgive me," said Maurice. "How inconsiderate I have been! You must

have more than enough of your own shadow." Maurice had heard the

saddest accounts of all his friend had suffered.

The professor smiled. Just then his wife came in, looking

thoughtful, but seriously sweet. She recognised Maurice immediately,

and welcomed him.

"Alison, Mr. Macdonald will dine with us," said her husband, "and in

the meantime he will stay with me. It will set you free for an hour

or two."

She smiled on them and left them together.

"Shadow!" said the professor, resuming their discourse. "I have

turned my back upon that long ago. There is only one shadow to face

now — that of the dark valley. Life is all too bright for me. You

can guess how bright she has made it, can you not? God's last, most

precious gift."

"Yes," said Maurice, in a low tone, "but the more precious a thing

is, the harder it is to give it up."

"'The kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchantman seeking goodly

pearls, who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and

sold all that he had and bought it.'"

The voice of the professor sounded on like a strain of perfect

music.

"And again — 'This is life eternal, to know him the only true God,

and Jesus Christ whom he hath sent! For that knowledge I laid down

everything long ago, all earthly wisdom — all earthly love — all,

all. Do you know what attracted me to you, Macdonald, more than to

any of the young men I had taught? It was that I saw in you a reflex

of my own ardent youth. Like you, I coveted the best gifts."

"But you never failed as I have failed," interrupted his hearer,

bitterly.

"How do you know that?" said the professor. "I only know that my

wisdom had become foolishness and my love idolatry, when I was

plunged headlong into a sea of sorrows. Failure! I should think I

know what that is. I had failed to find a God in the universe. The

more I studied his marvellous works, the less I knew of him, till,

with the fool, I had said in my heart, 'There is no God.' Can any

failure be so great as that — to seek life and to find death?"

He paused exhausted. Maurice's countenance fell, for he had been

hanging on his master's lips, with the secret hope that they might

drop this pearl of price, this knowledge which was worth all the

world besides.

"I will go on," said the professor. "I will tell you my story,

though there is not much to tell. I was in the heyday of my youth,

poor but successful, and bent upon success in the branch of study I

had chosen. A prize offered, a prize of no ordinary kind — one which

would have set me at once above poverty and necessity, and given me

the amplest means and opportunity for the pursuit of my science. More than that, it would have allowed me shortly to marry the woman

I loved — not this Alison, but another, her youngest aunt. That

prize I lost through the treachery of the friend I loved best. The

prize itself was only a certain gold medal, but the gainer of the

medal was to receive an appointment of value. I and my friend went

in for it together and it would have been mine but for a flaw in my

method, due, as I came to know, to his wilfully damaging my work. "It was at terrible experience. I think I could have borne the loss,

especially if it had been his gain; but the after-knowledge was more

than I

could bear. It shook my faith in that humanity which I had been

exalting to the chief place in the universe. But worse was to

follow. I had been overworking before, and the shock proved too much

for me. I fell down in a fit, which passed away, but left me, the

doctor said, liable to a recurrence of the same kind of seizure, and

revealed in my never very healthy constitution a tendency to

paralysis. Under the circumstances I myself would have set Alison

free; but she was the first to break the bond. Shortly

after she married my friend, and they went away together to the post

which was the fruit of his treachery."

"But he never prospered. Such men never do," said Maurice,

triumphantly. "I should like to hear how that man ended."

"The end is not yet," said the professor, sadly. "He is a prosperous

man as the world counts prosperity; one of the shining lights of the

great metropolis — everywhere quoted, courted by the great, rich,

and renowned. He has friends, he has children."

"Her children?"

"No; she died young, and he married a wealthy wife."

"How did I survive it? I threw off the disease instead of the mortal

coil which I desired to be rid of. Do you know that I have sometimes

longed to lay hands on my own life. I knew enough of the secrets of

nature to have put an end to it painlessly; but something withheld

me — a feeling of the meanness of deserting mingled with the

interest of the lover of experiment in watching it to the legitimate

end. But I was sunk in a very sea of sorrow. I could have said with

the psalmist, 'All Thy waves and billows have gone over me.' I

seemed to lie forgotten and forsaken of God and man.

"Then one day I began to think over my childhood, a very lonely but

a very happy one, and I remembered a dream of mine — a very frequent

dream it was, of climbing up an endless stair, all in darkness, and

that one day in going up an actual stair the dream had led to a

strange realisation. Young as I was at the time, I thought to myself

'This stair is my life. I am going up and up into the darkness; but

it will be light at the top.' And then I thought the Christ of my

childish fancy stretched a hand out of the darkness and led me on. When I came to myself I was standing still on the landing-place. But

the momentary vision had made the greatest impression on me. I

remember trying with all my might to be good, and to feel that

presence with me always. All this came back to me then, and in my

weariness I took up the Greek Testament that lay beside me, and had

been used as a mere text-book for the language. I read and read. All

at once — all at once that central figure became a Divine reality. This knowledge of God in Christ Jesus the Lord was no cunningly

devised fable. It was life itself, the spring and source of all. 'All that I have, all that I am, are thine,' I exclaimed aloud. I

had found the pearl of great price, and I thank God," added the

professor, "that from that hour to this I have been enabled to count

all things

but loss that I might win Christ, and be found in him."

"I envy you," said Macdonald, "for what so evidently gives to your

life its unity and joy; but you do not know how hopeless it makes me

feel. If you had spoken to me in an unknown tongue, I could hardly

have realised less the nature of the influence under which you feel

and act."

"I can understand it well, for the influence is faith, as much the

gift of God as this wonderful gift of sight, the secret of which all

the microscopes and all the science in the world cannot reveal. All

that I can tell you happened to me was that 'whereas' (spiritually)

'I was blind, now I see.'"

"I would give all I have for such a vision," said Maurice,

earnestly.

"Then," said the professor, sinking back wearied, "you are not far

from the kingdom of God."

That day they conversed no more. The conversation had exhausted the

invalid, and though he was very glad to spend himself in such a

service, both Maurice and Mrs. Macdonald insisted on complete

repose. He lay on his couch beside them, and listened to their quiet

converse, and looked "infinitely happy." Maurice could describe it

as nothing less. "Heaven!" he would say in the after-time, "it

requires no translation to take us there. I have seen it shining on

a human face. Nay, what is more, I can

say, humbly and reverently, I have felt it within me, especially

when I have been wearied out with bodily service."

Maurice was able to say this, for, remaining with his friend to the

last, pouring out his whole heart to him, and taken into close

communion with his Christian spirit, he too found the priceless

pearl. A recognition of their immortal fellowship was among the last

earthly utterances of the dying saint, for whom death had lost its

sting — nay, to whom to die was gain. Only the Christian can feel

that. The worldling may meet death stoically even if it does not

come upon him unawares; but to him it is the loss of

all, "the direst discouragement."

And Maurice had been living in the very shadow of death. The death

he had witnessed, and that which he had not witnessed, had both

taken a supreme hold of his imagination; a verse he had seen

somewhere was for ever ringing in his ears:—

|

"Oh, awful triumph of the tomb!

The deepest love must leave us there,

And ending thus in hopeless gloom,

The deeper love, the worse despair." |

It rang in his ears as he walked along the shores of the firth, and

came back again to the side of his dying friend and teacher, from

whose lips he heard, as if in another language, that to die was

gain.

What gain? Was it a gain in love, in power, in knowledge? How could

any one tell? No one had returned; no one had ever succeeded in

piercing the dark veil. Every earthly thing had to be laid down

before taking that journey. And yet they were no meaningless words

to him who uttered them. When the hour of mortal weakness came, with

solemn joy the professor hailed the summons.

"Maurice," he said, "this faith supports me;" they had been speaking

of immortality — an immortality of love, and joy, and power. "This

faith supports me; but I shall not need it long, I am going to

exchange it for reality. Even the merchantman bought the priceless

pearl to exchange again, and not to keep. There will be no need of

faith in Heaven. Have you found it yet?"

And Maurice had knelt down by the bed of his friend, and whispered,

"I have found it."

"And you are satisfied?" He spoke as if with assurance.

Maurice pressed his hand, and answered, "I am satisfied."

"And you close with the bargain?"

"All that I have,"' whispered Maurice, as it making a vow.

"And all that you are or can be," echoed the professor, solemnly,

laying his dying hand on the young man's head.

Maurice rose up released for ever from death's dominion. There are

those who say that even if this life was all, if it ended with the

latest breath, there would still be enough to thank and bless God

for having given; who say that they could still enjoy life, with all

its varied pleasures, its beauty, its goodness, its tenderness, its

love.

Not so Maurice Macdonald. No sooner had he come in contact with sin

and death, than that last fearful penalty annulled for him every

joy, quenched every aspiration, poisoned the springs of life. He was

ready to exclaim;—

"T'were better that we had not been,

If death's dominion holds, and he

The face of God has never seen

Who dreamt that dream of life to be.

"Better that unto us be born

No child, to us no son be given;

That, mocked of God, Creation's scorn,

Our race should fail from under heaven.

"The childless world for some few years

Would bear her freight of human woe;

And then, rejoicing, with her peers,

Voiceless but glad would onward go." |

But now in Him who brought life as well as immortality fully to

light, Maurice could be satisfied. His swift-thoughted fervent soul

need no more sink to earth, but might move in curves wide as

eternity itself

"To die is gain." The words had been often on the professor's lips,

and Maurice had at length understood their force and preciousness. Yes, truly, the bargain he had made was an infinite one. All that he

had was the poorest, the most worthless exchange for it. Yet it

followed naturally. If he had given himself to Christ, all that he

had went with it.

And what had he? He began to reckon. He had wealth. If he could have

laid it down at an apostle's feet, that would greatly have

simplified matters for Maurice, but times had changed since the days

of Peter, James, and John, and even if there had been an apostle at

whose feet he could have laid it, the wealth of the London merchant

was difficult to realise. He might draw from it a princely revenue,

but the capital from which it was drawn was at the four corners of

the earth. To gather it in would be to plunge hundreds into poverty. It was better obeying the command, "Occupy till I come," to let it

remain where it was. In this light he could not look upon that vast

capital as his at all, and for the rest he was also a steward. He

had culture. "How could that be given up to Christ and used in his

service?" Maurice asked himself. It could not be worthless — a thing

to be cast away as soon as a man became a Christian. Surely that

which had received so much from Christianity had something to give

back. They were questions which Maurice would never have asked at

all, if some of the finest minds of his day had not misunderstood

the nature of culture — had not exalted it on a false basis, till

they had made it a means of separation from their fellows, instead

of a bond of union — a thing of forms of words, instead of living

truths. Thus treated culture becomes sickly and feeble. To create a

caste of culture is a folly, for culture lives on universal

knowledge and universal sympathy. It is the filth of the soil of

humanity, and instead of making that soil richer, such a culture

tends to make it poorer and poorer, to exhaust it altogether.

By a flash of his quickened intellect, Maurice perceived that

religion was the highest culture, and that all lower culture was in

its service, was helping to do its work. Besides wealth and culture,

Maurice had the influence derived from these, from his position, and

from his youthful energy, which seemed intensified under the power

which had taken possession of him. More than all the old ardour of

his nature returned to him. It was the renewing of his youth, the

renewing of his strength. "He has come back with new life," said

those who knew him, and noted the outward change. Maurice felt it to

be nothing less, only he knew that it was not due to the body, but

to the spirit. Men embrace the Gospel so coldly that they never know

its joy. Maurice did. Accepting its terms without reservation, he

knew what is fully known to few,

the peace that passeth understanding, the joy that is unspeakable

and full of glory.

And it seemed his function to distribute joy. Some poor struggling

East-end curate would get hold of his name, and come to him as a

last resource for help for some failing school, some sinking refuge,

saying, "You don't know how hard it is to collect money for such

things. It is harassing work. People seem to have so many claims

upon them; doubtless you have more than most. And yet a little will

help us with your name."

"Save your energies for better things than begging," would Maurice

answer. "I will give you all you require."

"All!"

Having ascertained that the thing was good, why should he withhold

what was needful to its success? "Oh, but we want so much," the

slightly abashed worker would say. "We could not expect you to do it

all."

They might not expect, but Maurice would perform. Asking simply,

"How much do you require?" he would hand over to the astonished and

generally depressed collector a sum over and above what he asked,

saying, "Call upon me next year, and I will do the same." "For the

first time in my life I wept for joy," said one who had experienced

many a disappointment and many a rebuff for the cause he had at

heart, and who had gone to Maurice anxious and care-burdened, and

had come away thankful and free. "He is the only man I ever envied,"

said another, in the like case, and that man would have given his

life for his work.

And that was what Maurice longed to do. Nay, he was doing it in a

measure, for he laboured on at the calling which enabled him to give

his princely gifts. His charity was simply unbounded, for much of it

was unknown and unheard of. He still lived in his father's house, but

its expenditure was reduced to the minimum. In it were no idle,

wasteful servants. Its master lived a life of austere simplicity. He

kept no carriages. He walked, or used the public conveyances. He had

to be a law unto himself, and very strictly he ruled the

interpretation concerning "all that he had."

CHAPTER IV.

IT was the summer of 1870. With the suddenness of a thunderstorm war

burst upon Europe. Like the peals of its thunder, followed one

another in rapid succession its strange and terrible events. The

army of France marched to the invasion of Germany, and the German

legions retaliated by the invasion of France. There is a skirmish at Saarbruck, at which a sickly boy receives "his baptism of fire" —

hollow horrible words, which reverberate with a ring of mockery

among the nations. In two days follows the battle of Weissenburg, in

two more that of Wörth. The fields of France are already reeking

with slaughter. A few days more and Courcelles is fought under the

walls of Metz. Mars-le-tour and Gravelotte follow, with hardly

enough interval for the burial of the dead. After the desperate

slaughter of Gravelotte there is a brief interval, till the hosts of

Germany, still pouring into France, surround and capture a whole

army at Sedan. Round and about the city is a very Aceldema. The

Emperor gives up his sword and 8o,ooo prisoners. And all within one

short month since that skirmish at Saarbruck.

Then from those conquered provinces rose a cry

which rolled over Europe. On to Paris tramped the conquering

hosts, leaving behind them a mass of human misery unequalled in

modern times — burning villages, ruined homesteads, homeless wanderers, and everywhere the

wounded and the dying, and the fields of dead.

Among those whose hearts rose at the cry — and in England they were

not a few — no one responded more eagerly than Maurice Macdonald. There was yet in the background of his life a sense of

incompleteness, a feeling that he had a warfare to accomplish, and

was straitened till he had accomplished it. When the horror of that

time seemed to reach its culmination in the burning of Bazeilles, he

could remain a spectator no longer. He said to himself "I must go to

help not only with money, but with personal effort, in the relief of

the sufferers." To don the red cross, whose badge some few

miscreants were wearing for pleasure or for profit, and to make it

the sign, as was meet, of supreme self-devoting sacrifice, was to

his eager spirit the very service for which he craved.

No time was to be lost. Before the business day was done on which

his resolve was taken, he called on Mr. Messenger in the City,

prepared at all points. The object of his visit was to ask that

gentleman to be his executor, which he did in so many words.

"You are making a will. It is quite right, but you seem in haste

about it," said Mr. Messenger.

"I am going abroad. I may be in danger. You ought indeed to know all

about it before you undertake this. I will tell you. I am going to

the seat of war."

"On business?" asked his friend.

"No," replied Maurice, and he smiled. "I am going as a Red-cross

Knight."

The elder man was cautious. His eyes moistened; but he said, "Are

you sure you ought to go?"

"I think I can be of use there," he said, simply. "But you must keep

my purpose secret. I do not wish it to be known."

"But," Mr. Messenger urged, "there are many in the field already. Had you not better keep your post here and contribute to the funds?"

"I am called," said Maurice. "Do not think me vain, but I know

something of business and the modes of getting rapid supplies. I

know the language of both combatants, and men are dying. I may be

privileged to speak the word of life, as well as to give the bread

which perishes."

"Go," said Mr. Messenger. It was all he could say. He was deeply

moved.

Then Maurice told him what he would be called upon to do in the

event of his death. There was provision made for the carrying on of

the great concern of which he was the sole head. He had nominated

two of his principal employees his successors, on the payment of

certain sums to his executor, stretching over a period of years; he

had endowed the various schemes he had hitherto aided, and made

munificent bequests to others. Everything had been thought of. No

one dependent on him had been forgotten, whether friend or servant. When he had explained every arrangement, he and Mr. Messenger drove

together to the lawyer's chambers, to whom a draft of the will had

been already sent. It was signed, sealed, and witnessed that very

hour.

"Now I am ready," said Maurice, as they walked out together.

"And when do you go?"

"To-morrow," was the quiet answer.

"So soon? Won't you come and say good-bye?" asked his friend. "How

long have you?"

"Till noon."

"Then come with me now."

Maurice hesitated, and answered, "No." It would be better to have no

farewells. There were some things he could do. And there was

something to say before he could take the place he coveted in Mr.

Messenger's household.

Mr. Messenger insisted on knowing what it was, and received from the

young man a full and free confession of the wrong that had stained

his life. "If I come back again," he added, "will you receive me?"

"Maurice, you are not going with the dream of making expiation?"

said Mr. Messenger.

"No," he replied. "That has been made for me."

"Come back, and we will receive you gladly," said Mr. Messenger.

"As a son?" he asked, holding out his hand.

"As a son, Maurice."

"Will you give my love to Mary, then?"

"I will."

And so they parted; and Mr. Messenger went home and told the news

to his eager circle.

"Going to the war!" said the younger sisters, half-incredulous, and

anxious to know all about it. Then they looked wistfully at Mary,

for though Maurice's visits had not been so frequent as so favoured

a guest's might have been, and though there hovered about his

attentions an indefinable timidity, the sisters in their secret

confidences had set him down as Mary's lover. But Mary murmured,

"Oh, mamma!" and went away that she might hear no more.

Next morning early, long before visiting hours, Mrs. Messenger

brought her eldest daughter to pay a farewell visit to Maurice. They

spoke to him so cheerfully, that, though he had shrunk from the

meeting, he was glad they had come, he hardly dared think how glad.

"Have you done all your packing?" asked Mrs. Messenger.

"I do not know," he answered, smiling.

"Why do you ask?"

"Because we want to give you something, and we must not waste time

about it," she answered.

"See, it will not burden you to carry," said Mary, holding up a bit

of red braid.

He understood in a moment, and went away, and came back with a coat

over his arm.

Mary sat down and took out a little work-bag, and sewed upon the

sleeve the figure of a cross. Mrs. Messenger looked on while her

brave girl did it and gave it to Maurice with a sweet serious

smile. "Good—bye," she said, putting away her things, and rising to

go.

"Good-bye, and God bless you, dearest!" said Maurice, holding her

hand for a moment.

"Come back safe to us," said Mary's mother, and they left him, for a

moment half-unmanned.

A week after Maurice was in Sedan. Almost all trace of the battle

which had raged round its walls had disappeared. The dead had been

buried, the wounded carried off to such shelter as could be found

for them, the débris of musket and helmet and war material gathered

up and removed, and the dew had washed away the strange dark stains

where horse and man had fallen, shattered by shot and mitrailleuse. Only a dead horse lay here and there, tainting the wholesome air,

only a letter fluttered by bush or roadside, the last of hundreds

already gathered and sent "home" by kindly hands to French village

and German cottage.

But in the villages round there was no end to the trail of horrors,

to the suffering which seemed to increase instead of diminishing as

the days went by. September waned, and as the wounded were healed

the hale sickened. The Prussian requisitions had swept away the

people's food. Pestilence, too, followed in the track of the war,

smiting man and beast. The cattle over a wide area died by thousands

of rinderpest; fever and dysentery attacked the starving peasantry.

Maurice had intended to follow the army, but he could not leave the

scene of such wide-spread disaster. Everywhere the young Englishman

was known, in every emergency; in the lazaretto tending the

stricken, working with M. le Curé in saving his scattered flock from

famine and despair; thoughtful of the coming winter, ordering

blankets, provisions, fuel, and food.

Another month passed away, during which the utmost exertions had

only sufficed to keep the people alive, and had done little to

repair the actual ravages of the war. Another month brought the rain

and the cold, and the capitulation of Metz. An American, foremost in

the work of mercy, entreated Maurice to come thither, for all the

district round the beleaguered city was in misery and in ruin, and

within its walls was hidden the most fearful suffering.

On the raising of the lengthened siege the soldiers, happily for

them, fell into the hands of their enemies ― the sick to be cared for,

the prisoners to receive welcome rations; but the poorer among the

townspeople, left to their own resources, were in greater straits

than before. Thousands of cases called for immediate relief. From

house to house in the narrow back streets Maurice and the American

went, carrying food and cordials to those who were too far reduced

even to make known their wants; to fathers and mothers who sat

listlessly starving, knowing nothing about their city's fate,

knowing only that it was days since they had eaten their last meal

of bread mixed with sawdust, or of the carrion of which their little

ones had long ago sickened and died.

This was their first task, and they saved many lives which another

day, or even a few more hours, would have put an end to. But outside

the city, in the burnt and battered villages, the scenes were still

more appalling. Having seen the most pressing distress within the

walls alleviated, and its recurrence to some extent provided

against, by a large index of help and the liberality of the richer

citizens, Maurice and his friend separated, to render what

assistance they could to the wretched country people in the environs. From an outlying village Maurice managed to send a message to his

friend that he would remain for the present, as his services were

urgently needed. They had taken rooms together in Metz. Maurice did

not return, and the American was called elsewhere; at the end of

eight days he set out in search of him.

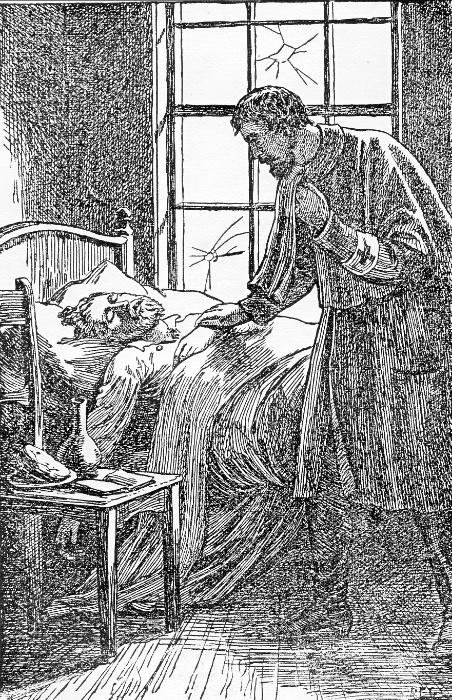

"With a great and bitter cry he recognised in one of

them

the body of Maurice

Macdonald."

It was with difficulty that he found the place, asking first, as

always, for M. le Curé. He was answered that M. le Curé was dead. Where was his house? It had escaped the general destruction, and he

had turned it into an hospital and general refuge — he had turned it