|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER LIV.

THE REBELLION OF ’45.

A.D. 1745.

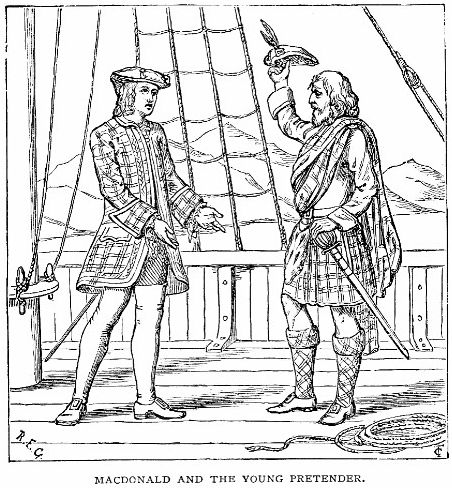

IF Prince Charles Edward had stood in his

father’s place, he might have won back the crown which his

grandfather had lost. In 1745 he had all the qualities which

attract and attach men. He was handsome, brave, and

high-spirited, generous, affectionate, and self-denying; but his

education had been shamefully neglected, and his judgment was far

from strong.

After the failure of the expedition from Dunkirk, France deserted

his cause; but nothing would induce him to return to Rome and accept

defeat. He was resolved to try his fortune alone, and he wrote

to his father to sell his jewels for money to fit him out. With

this, and some which he borrowed, he fitted out a little ship, and

with seven followers set sail for Scotland. He landed on one

of the western islands, and asked for the chief of the Macdonalds.

He was absent. Next day the old man came on board of the

prince’s ship, and tried to persuade him of the madness of the

enterprise; but it ended in his persuading the Macdonald to risk

everything in his behalf.

So it was with every other Highland chief who came to him.

Cameron of Lochiel held out long; but Charles said, “I am resolved

to put all to the hazard. I will raise the royal standard and

tell the people of Britain that Charles Stuart has come back to

claim the crown of his ancestors, or perish in the attempt.

Let Lochiel stay at home, and read the news in the papers.”

“Not so,” replied Lochiel, “I will share the fate of my prince,

whatever it may be, and so shall every man over whom I have any

power.”

It was a whole month before the English Government knew that the

prince had appeared, and in that time Charles had raised a Highland

army. King George was, as usual, in Hanover. Sir John

Cope in Scotland was ordered to oppose the prince, and offer thirty

thousand pounds for his head.

Cope marched northwards, leaving the way to Edinburgh open, which

Charles at once seized, and led his little army to the capital.

Edinburgh was unprepared, and could offer no resistance. The

garrison of the castle shut themselves in, and Charles entered

Holyrood, the ancient palace of his ancestors, unopposed. That

very day he had his father proclaimed at the market cross, and in

the evening he gave a ball in the palace.

News came that Cope was marching on Edinburgh from Dunbar. The

prince did not await his coming; he went out to meet him with only

two thousand five hundred men and a single gun. They came up

with each other at Prestonpans, about six miles from the city.

The Highlanders charged fiercely, and in less than ten minutes the

battle was won. Cope’s men were flying, and the Highlanders

cutting them down without mercy. Charles put an end to the

slaughter as quickly as he could, and he stayed all day upon the field

caring for the wounded, chiefly his enemies. Next day he

marched back to Edinburgh, and with great delicacy would allow of no

rejoicings for the victory, because it was over his father’s

subjects. He wrote to France of his wonderful success, and

asked the king for aid; but none was given; only a little money was

sent to him. A powerful fleet was by this time in the Channel,

and prevented more substantial help. King George had returned,

an army had been brought over from Flanders, and General Wade with

the English, and the Duke of Cumberland with the foreign troops,

were advancing. All this time Charles spent at Holyrood,

waiting for French help, and eager to set out for England.

At length he would wait no longer, and contrary to the advice of the

chiefs, he left Edinburgh, and began his march into England.

His enterprise had been hopeless from the first. It became more

and more hopeless with every step he took. He reached Derby

unopposed. The way to London was open, and he wanted to press

on. Wade and Cumberland were both between him and Scotland.

To turn back was to give in. But he could no longer urge

forward his disheartened followers. They wanted to get back to

their native hills. Hardly any Englishmen had joined them.

The English looked upon Highlanders with a kind of horror.

Some of the ignorant people believed that they ate little children.

So from Derby Prince Charles turned back, no longer bright and

radiant, but listless with bitter disappointment. The towns

and villages through which they passed mocked and insulted the

retreating army, sometimes even ventured to attack it, and provoked

attack in return. But at length they crossed into Scotland,

and got safe to Glasgow. That city was against the Pretender;

and Charles made its inhabitants contribute new clothes and new

shoes to his army.

Leaving Glasgow he marched on Stirling Castle, and gained a battle

at Falkirk, but it did him no service. The Highlanders were

deserting to go home. Their chiefs were quarrelling, and

Cumberland and his army were coining on. Charles began a

retreat into the Highlands.

He marched into Inverness, and on Culloden Moor the decisive battle

was fought. The army of the Pretender was worn out with

fatigue, and weak with fasting; the army of Cumberland in good

condition and high spirits. The latter opened the fight with

cannon while the snow was blowing in the faces of the poor

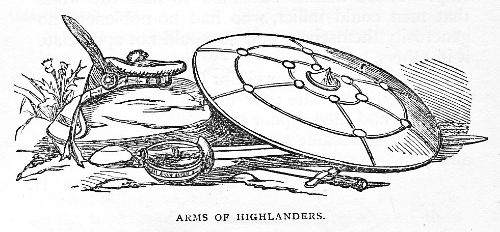

Highlanders, who could hardly stand. Several times they tried

to make a rush, and cut their way with their broad swords through

the English lines; but they fell, before they could strike a blow,

under the steady fire of their enemies. The slaughter was

terrible. The Highlanders were utterly defeated. They

were pursued and cut down without quarter by the English troopers.

Even the wounded were mercilessly killed, and that by command of

Cumberland. Twenty wounded men, who had taken refuge in a

farm-house, were shut up and burned in it. His ferocious

cruelty earned for the Duke of Cumberland, the son of King George,

the title of “THE BUTCHER.”

Charles escaped to the mountains, and Cumberland continued to hunt

out his adherents, and slay them, not even sparing the women and

children. For this kind of work he was praised and pensioned

by the Government, and hated and abhorred by all good men wherever

his name is heard. The search for the young Pretender was

going on with vigour, for the thirty thousand pounds were still upon

his head.

He took refuge among the Macdonalds of the Isles; the hunters

following landing on the very island where he was. Hundreds

knew of his hiding-places; but not the poorest among these poor

Highlanders ever offered to betray him. In his greatest peril

he was rescued by a young lady, Flora Macdonald, who took him to a

place of safety, dressed as her maid. From the islands to the

mainland, through shires where every pass was guarded, he was guided

and passed on from one to another till his friends had seen him safe

on board a French ship. These friends remained to face the

worst that men could inflict, who had no nobleness, no generosity

themselves, and so could not appreciate it in others.

It would have been well for Charles Stuart if he had shared their

fate; for he outlived all his fine qualities, and died a poor

miserable drunkard. His only brother became a priest, and was

made a cardinal, and so ended the Stuart race.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LV.

GEORGE II. CONTINUED.

THE king’s eldest son now died. He was

in the prime of life, but he had wasted his strength in dissipation.

Still he was better than the Duke of Cumberland; and the people were

sorry, and said openly that they wished it had been THE BUTCHER.

Frederick, Prince of Wales, left eight children, the eldest of whom

became George the Third.

On the 30th of April, 1748, a truce was concluded at

Aix-la-Chapelle, and everything was left much as it had been before

the war, except that the King of Prussia ruled over a state that had

once been part of Austria; that England had spent some millions of

money, and that a countless number of lives had been lost, and

another countless number made poor and miserable. It must

always be so with war; therefore to cause war is the greatest crime

that a man or a nation can commit.

This peace did not last long. France and England were soon

again at war; but this time it was in the remotest parts of the

world, in North America and East India.

The French had a great colony in North America called Canada.

It is the only part of North America that now belongs to England,

but at that time almost all the country which had been colonised was

ours. A dispute having arisen between the French in Canada and

the English in New England about the boundaries of these states, the

French had built a fort and begun an irregular war.

Washington, of whom you will hear more presently, took the field

against the French and their allies, the Indians. Then a fleet

was sent out from France to help the Canadians. After them

went a British fleet to drive the French fleet away, which it would

have done, only the French fleet escaped in a fog near Newfoundland.

When the war had gone on some time, William Pitt, who was prime

minister in England, sent out a young general named Wolfe, who took

Quebec, the capital of Canada, after which the whole colony fell

into our hands. Quebec is a very strong city, built on a high

rock above the river St. Lawrence, which is frozen over for months

every year. There was a garrison inside the city and an army

under a brave French general outside, and Wolfe despaired of taking

it. However, one dark night he took his men higher up the

river, and set them to climb the steep rocks, so that they could get

a good position for fighting.

The next morning the French general was astonished to see the

English army on the heights. A battle was fought; the English

gained a victory, but Wolfe was killed. As he was dying, one

of the officers near him said, “See how they run!” He opened

his eyes and asked, “Who runs?” “The enemy,” was the answer.

“Then I die happy,” said the young general with his last breath.

This happened in 1759.

Meantime England had gained an empire in India. A young man,

whose name was Clive, and who had been a clerk in the service of the

East India Company, thought he would like fighting better than

clerk’s work, and so left his desk and became a soldier. There

was fighting going on, and he soon showed that he could fight well.

There were French merchants and English merchants in India, as well

as French and English soldiers; and when the French and English

merchants quarrelled, the French and English soldiers fought out the

quarrel. The native princes of India fought, some on one side

and some on the other, and some against both. So Clive had

plenty of practice. At length, in 1757, he took Calcutta,

which you know is the capital of a vast province. Its prince

was an ally of the French and he had shut up 146 English prisoners

in a place so narrow that they could not breathe, and one night 123

out of 146 died a terrible death. The place where they died is

known by the name of “the Black Hole of Calcutta.” This cruel

prince Clive utterly defeated, and made him give up to England the

city and the land all round it; and at last put another prince on

his throne, who promised to be faithful to the English.

I have not much more to tell you of this reign. Towards its

close France seized Hanover, which was defended by the Duke of

Cumberland, who was compelled to surrender, and not to serve again

during the war. He died in 1765. Five years before died

the king himself. His reign had not been a happy one; but in

it were begun those great improvements in machinery which have made

England what it is at present, “the workshop of the world.” A

chapter in the next reign will tell you a little of the men who

fought in this better war, the war of industry; a war not to kill

and destroy, but to save the life and labour of millions.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LVI.

GEORGE III.

A.D. 1760 to 1820.

GEORGE THE THIRD

succeeded his grandfather at the age of twenty-two. He was a

much better man than his father, though he had very little wisdom

and a great deal of obstinacy. When he came to the throne he

was sovereign of the States of America as well as of England; and it

was in his reign that America became a separate nation. His

want of wisdom and his obstinacy had a good deal to do with

hastening this; but sooner or later it must have happened, at any

rate. America had grown too big to be governed by England.

In the time of George the Third its States were growing into

nations, with great cities and assemblies of their own, by which all

their affairs were managed. In 1764 the English Government

resolved to tax the Americans; and instead of asking them to vote a

share of their taxes to England, for the expense to which England

was certainly put on their behalf, the English Government put on the

tax without their consent. The Americans refused to pay it;

just as Englishmen, you will remember, refused to pay the taxes

Charles the First put on them without their consent.

They sent over to England a clever man called Benjamin Franklin to

plead their cause with the king and Parliament. He had been in

England for several months, where he had worked as a journeyman

printer. He was now known as a philosopher all over Europe.

It was he who discovered, by means of a paper kite, the nature of

electricity, which in our days has been put to such wonderful use in

sending messages by the telegraph. Franklin told the English

Government that, if they would only send letters to the States,

requesting them to vote money, they would get it without any

trouble.

A few wise men in England would have done this, but the king and his

ministers would not. An Act, called the Stamp Act, was passed,

imposing much the same duties on the Americans as were already paid

by the people at home. When the news of this reached Boston,

the city bells tolled as for a funeral, and the flags on the ships in

the harbour were lowered as for a death, half-mast high.

The American Legislature denied that England had a right to tax

America, and the Americans determined to resist. So great was

the opposition to the stamp-tax that the next English Parliament

repealed it. The Americans would not let the stamped papers

come into the country.

It was next proposed that the Americans should be made to maintain

the troops that were sent over from England. They replied that

they would pay no tax whatever, unless it was laid upon them by

their own representatives, in their own assemblies.

Then the English Government ordered troops to be stationed in

Boston, to frighten the people into paying their taxes, and the

people only insulted the troops. All the taxes were now to be

taken off, except a tax on tea. Three ships loaded with tea

came into Boston harbour. The people demanded that they should

be sent back. The governor appointed by England would not do

so. Then the people waited till it was dark, and went on board

the ships and threw the tea into the sea.

After this the governor was told to leave Boston, and the people

began to arm themselves to fight with the king’s troops. The

Americans asked that England should take away all its ships and

soldiers, and leave them to manage for themselves.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LVII.

THE AMERICAN WAR.

A.D. 1775 to 1782.

THE first blood was shed at a place called

Lexington. The Americans say the English were the first to fire,

the English say it was the Americans. At all events the

English had the worst of it. A great many of General Gage’s

soldiers were killed by men who fired from behind trees and walls and

houses, and were themselves unhurt. This was on the 19th of

April, 1775.

The Americans now appointed a commander-in-chief, and the war began

in earnest. The man whom they appointed was George Washington,

a simple country gentleman, who had been a colonel of militia.

He began a career of the purest patriotism by at once taking the

post assigned to him, and refusing to take the salary attached to

it. He joined the army on the 15th of June, 1775, and two days

after was fought the battle of Bunker’s Hill, which the English

gained with loss and difficulty.

The Canadians had not joined in the insurrection, therefore the

Americans invaded Canada. Upon this fresh measures were taken

against them by the English Government. German soldiers were

hired to fight against them, and worse still, the savage Indians who

roamed in the vast forests which everywhere surrounded the settled

States.

On the 1st of July, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was

passed. The American colonies became the “United States of

America.” France was ready to support them with an army.

They had need of help just then, for Washington’s army was very

small and ill-furnished. The English were gaining all the

victories. Still, Washington struggled through the winter.

The British troops suffered greatly, but the Americans suffered

more. They had no shoes and no blankets in the bitter cold,

and Washington could hardly get money to buy food for them.

They were obliged to seize upon provisions to keep themselves from

perishing of cold and hunger.

In the beginning of I778 the English Government proposed to treat

for peace; but the Americans said they were now a separate nation,

and could not listen to terms of peace till England withdrew her fleets

and armies. The French troops arrived in America in 1780, and

the fighting went on more fiercely than ever. But at the close

of the next year the English general, Lord Cornwallis, surrendered

himself and his army to the united armies of France and America, and

in another year the war came to an end. The independence of

America was acknowledged, and England might even have had to resign

Canada, but that while there had been nothing but loss and disaster

on land, the fleet, under Admiral Rodney had triumphed over the

navies of France and Spain.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LVIII.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

A.D. 1789.

A FEW years passed in comparative peace, when

the second great event of the reign of George the Third took place.

That event was the French Revolution of 1789. You may think

that this ought surely to belong only to the history of France, and

so, indeed, it ought. But it led England into a long and

bloody war. How it came to do so you will now hear.

You remember that I told you how very wicked the French noblemen

were in early times. I am sorry to say that in the time of

George the Third a great number of them were very bad still, and

almost all were very thoughtless and selfish. The poor people

and all who had to labour were cruelly treated, and dreadfully

oppressed. They could get by their hardest work only just

enough to keep them alive. The houses of the labourers were

dark and damp and unwholesome (I am sorry to say there are some in

England the same). Their food was poor and scanty; they were

clothed in rags. And yet these poor people had to pay all the

taxes, and mend all the roads, and do a great deal of unpaid work

for their rich masters. Everything was taxed, even the salt

which is so necessary to health that without it people would sicken

and die though fed on the richest food.

The land belonged to the rich noblemen and to the priests, and they

would pay nothing; and while they lived in the greatest luxury the

working people starved. The kings, too, who were always taking

more and more from the people, and carrying away by force to the

wars the men who earned bread for the children, had been very

wicked, more wicked than I can tell you. They did not care how

many people died of hunger that they might waste as much as they

pleased in pleasure; or how many were killed for their pride.

The Great Revolution began in Paris. The Parliament there had

spoken out about the misery of the people; and the people took it

into their heads all at once that, if they were so badly governed,

they would have no government at all. They thought they would

put an end to their poverty and misery by putting an end to kings

and nobles and rich people, and making everybody equal, which you

know would only have been making everybody as miserable as

themselves. But they were too ignorant to know this, and too

mad with all they suffered.

When you come to read fully about the things these unhappy people

did in their fury, you will feel inclined to hate them. There

never were such horrors before in the history of the world, and I

hope there may never be again. Their rage and their cruelty

were hateful enough, but I think that those who had lived for years

in luxury and selfish pleasure and seen their fellow-countrymen

become so miserable and so vicious were more hateful still.

The French king in whose reign the revolution took place happened to

be a far better man than those who had been kings before him for a

very long time. He was a plain, slow man, very sleepy-headed,

and fond when he was awake not of ruling his kingdom, but of making

curious locks. He had married the daughter of that brave

empress, Maria Theresa, of whom you read in the last reign.

Her name was Marie Antoinette, and she came to France very young,

and was very beautiful and very gay. The unhappy people

thought it cruel of her to be dancing and laughing while they were

starving and weeping. She was only thoughtless, but kings and

queens have no right to be thoughtless, and live only to enjoy

themselves. This king and queen had two children, a girl and a

boy, when the revolution began.

I cannot tell you all the dreadful things this poor royal family

suffered. The great crowd of miserable wretches marched to

their palace, broke into it, and terrified and insulted them in

their own rooms, where they were never safe afterwards, but lived in

constant fear of being murdered. Then they tried to escape,

and got away to a good distance; but they were missed and pursued,

caught and brought back again to be worse treated than before.

They were kept prisoners in their palace, and after a time taken

from it to a real prison, where the poor king was separated from his

family. And when the people heard that an army was coming

against them to place the king on the throne again, they made haste

to put him to death. They were still more cruel to the queen.

They took her little son, who was only eight years old, away from

her, and said she was so wicked that they could not leave him with

her. At last they killed her as they had killed her husband,

and she died as bravely and patiently as he had done.

The poor little Dauphin was given to a brutal keeper, who would

often shut him up alone, and who frightened him so that he never

spoke or called for anything. He grew up a sickly, neglected

child, as dirty and more miserable than any beggar-boy — he who had

been born heir to all the splendour of the kings of France. He

lingered a few years, and then died. The little girl alone

lived to be a woman.

Before the death of the king, Prussia, Austria, and several of the

small German States had united to invade France, and when Louis had

been put to death England too joined the allies. The French

had sent an army against the invaders, and had invaded Germany in

turn. Their general, Dumouriez, took a great many German

towns, but at last he went over to the Austrians, and would not fight

for the French Republic any more.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LIX.

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE.

A.D. 1799 to 1815.

FRANCE was now surrounded by enemies, indeed

the whole world was against her, and she was alone against the whole

world. No sooner was the Reign of Terror over, and a

government called the Directory set up in its stead, than another

rising took place to unsettle everything again. Just then,

however, arose the wonderful man who was destined to be Emperor of

the French, and to conquer every country in Europe except England.

His name was Napoleon Bonaparte.

He was at that time only a poor officer living in lodgings in Paris,

with his mother and sisters, when the Government appointed him to

defend them; even then he was only made second in command. He

did not hesitate. He saved the government by a great slaughter

in the streets of Paris, and his fortune was made.

He was next sent into Italy, which he overran and conquered, making

the Italians give him, not only a great deal of money, but their

most beautiful pictures and statues, which he sent home to his

masters in Paris.

When he came back from Italy he was received with every honour.

He had been recalled to take the command of the “army of England;”

for there was nothing the French people desired so much as to

conquer England; and no wonder, for England had given money by the

million to almost every other nation that they might fight against

France. Napoleon was wise enough to find out that he could not

conquer England just then, however. So he marched away to

Egypt. There he gained a battle, which he called the battle of

the Pyramids, and took Cairo; but his success ended there.

England as yet had no great commander. Wellington was only a

young soldier, fighting out in India; but she had Nelson on the sea,

and in the battle of the Nile he gained a great victory over the

French fleet. In Egypt Napoleon showed himself in his true

colours — a man who cared nothing for human lives.

When he returned from Egypt he was made First Consul of France; but

this did not content him. He went out again to conquer other

nations, that he might make himself greater at home. Some day

you will read more particularly how he crossed the Alps, and

conquered Italy the second time, plundering her still more; how he

came back, and governed in France, and made new and mostly wise

laws, and put to death all who stood in his way, till at length he

made himself emperor, and got the poor old pope, who was eighty

years of age, to come all the way from Rome to put the crown of

France on his head. All the nations had made peace with him,

even England; but after he was crowned, Prussia, Austria, and

England united against him, and he soon found an excuse for making

war against them. Next year (1805) he marched into Vienna, the

capital of Austria, whose king had run away; and there, as usual, he

took everything he could. He then defeated the Russians and

Austrians at Austerlitz, and once more returned victorious.

In this same year was fought the famous battle of Trafalgar.

The news of Nelson’s victory was brought to Napoleon when he was on

his way to Vienna. He was full of rage, for he knew that after

that he could never conquer England.

Nelson had been staying at his home, Merton, in Surrey, in very bad

health. When he heard, however, that a great French and

Spanish fleet was threatening England from the harbour of Cadiz, he

offered at once to take the command. On the 15th of September

he was again on board his ship, the Victory, and sailing for

Cadiz. The enemy’s fleet was expected to come out; but Nelson

was watching it as a cat watches a mouse. “I am sure I shall

beat them,” Nelson said; “but I am also almost sure I shall be

killed in doing it.”

It was the 19th day of October before the French fleet came out.

On the 21st, off Cape Trafalgar, they came in sight; and Nelson

immediately ordered his ships to bear down upon them, and then went

into his cabin and wrote a prayer. He felt that he should not

come out of the action alive.

Then he ran up a signal on the mast of the Victory for all the other

ships to read. It was the famous signal, “England expects

every man to do his duty.” By twelve o’clock at noon Nelson’s

ship was engaged with four of the enemies’ ships. One of them

held fast to her with great hooks, so that they were like two

sea-monsters gripping each other. Each ship kept firing at the

other, and the masts and spars were crashing together till they were

shattered. Then both took fire. The fire in the Victory

was extinguished, but the enemy’s ship was destroyed. It was

from this ship (the Redoudtable) that Nelson received his

death-wound. One of the French riflemen, from where he stood

upon the mast, saw the commander, knew him by the star upon his

breast, took aim at him, and shot him down. He fell upon the

deck. Captain Hardy came and asked if he was severely wounded.

“Yes,” he replied; “they have done for me at last.” He was

carried below, and lay for an hour or two listening to the thunder

of the guns. The captain came again. Nelson asked how

the battle went. Hardy replied that fourteen or fifteen vessels

had been taken. “That is well,” said Nelson, “but I bargained

for twenty.” He had made up his mind before the fight to take

at least twenty of the French ships.

The battle was not half over when Nelson fell; but never was there a

more decisive victory. The enemies’ fleet was entirely

destroyed. For the next fifty years England was safe from

invasion. This safety was bought with the life of Nelson.

The fight was no longer doubtful when he died. He remembered

those whom he had loved in his last moments, and begged the captain

to kiss him; for this man was a true hero, as tender-hearted as he

was brave.

Napoleon next marched into Prussia, and in three weeks defeated its

armies at Jena and Auerstadt, took possession of its fortresses, and

lived in the palace of its king. Then the conqueror went into

Poland, and fought more battles; but at one place he met with a

repulse, and retired to Warsaw, where he intended to stay till the

spring of 1807. But while it was still winter he was forced to

come out and fight, amid snow and ice, an army of Russians, the

allies of Prussia and England, at a place named Eylau. The

French were severely repulsed; but the Russians were unable to stay

on fighting, and their emperor met and made peace with Napoleon.

Next year (1808) the fighting was chiefly in Spain and Portugal.

Joseph Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon, was made King of Spain.

In 1807 a French army had occupied Lisbon and Madrid, and robbed and

oppressed the people as usual. But the Spaniards and

Portuguese had risen against their enemies, and called on England

for help. England, though at war with Spain, at once sent

money and arms, and, what was of much greater value, a small army

under Sir Arthur Wellesley, afterwards the great Duke of Wellington,

who defeated the French at Rolica and Vimiera, and soon after

entered Lisbon in triumph, driving out the French and the new king,

Joseph.

When Napoleon heard of these reverses he came himself into Spain,

marched on Madrid, and immediately began to re-conquer the country.

One brave English general, Sir John Moore, was obliged to retreat

with great loss, and was himself killed in the battle at Coruna.

The English were again driven out of Spain and Portugal.

Napoleon had been obliged to withdraw, and Wellington was sent out

to take the chief command. He took the city of Oporto, and defeated

the French at Talavera. This great battle lasted two days, and the

French were just twice the number of the English. In the meantime

Napoleon was fighting the Austrians again, whom he once more defeated

at the battle of Wagram, and forced to make peace with him.

Not only did he make peace with Austria, but the very next year he

married an Austrian princess, Marie Louise, the niece of the

unfortunate Marie Antoinette. When this princess left Vienna, her

father’s capital, the people wept round her carriage, thinking she

was going to France to suffer as her aunt had done. But she seemed

well pleased to go, though Napoleon was now twice her age, and had a

wife living. The name of his wife was Josephine, and everybody

esteemed her. She had married Napoleon when he was a poor officer,

and loved him then and always. She loved him so much that she

pretended to be willing to go away from him when he wished her to

go, though it almost broke her heart.

In the meantime Wellington had been defeating the French generals in

Spain. All the winter of 1810, and the next year, and the year after

that, the fighting there went on.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LX.

THE RETREAT FROM MOSCOW.

A.D. 1812.

IN 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia with an army

of five hundred thousand men. He was quite confident of success,

and talked of conquering it in two battles. Calling his

soldiers to victory, he crossed the river Niemen on the 23rd of

June. The Russians had made up their minds how to act.

Great gloomy forests stretched along the banks of the river.

No army was to be seen to oppose the march of Napoleon’s soldiers.

When the head of the first column crossed the river, a single Cossack

rode out of the woods, and asked why they had come upon Russian

soil. The soldiers replied, “To beat you.” Then the

Cossack rode away into the woods again, and all was silent as

before.

It took three days for the great host to cross the river, over which

so few were ever to return. The Russians fell back as they

advanced. Napoleon, impatient to overtake them, pushed on

rapidly. That was just what the Russians had planned, to draw

the French into the heart of their country. They carried off

the provisions, burning what they could not carry. They set on

fire their towns and villages. They left behind them nothing

but a desolate waste, where neither man nor beast could live.

Still Napoleon pressed on. On the journey to Moscow one

hundred thousand men fell from fatigue and disease. When, on

the 15th of July, they drew near the city of Smolensk, the officers

entreated him to turn back; but he would not hear. “We must,”

he said, “advance upon Moscow, and strike a blow in order to obtain

peace, or winter-quarters and supplies.” He could not believe

that the Russians would carry out their plan of wasting the country

so far. But as the army of the invaders drew near Smolensk,

the people poured out of its gates on the other side. In the

night the fires broke out. In the morning the conqueror entered a

deserted city, or, rather, deserted ruins.

In Moscow, the ancient capital of Russia, and regarded by the

Russians as a sacred city, a council was held whether they would

abandon it or no. Even this was resolved upon at last; the

greatest sacrifice ever a nation made.

On the 14th of September the Russian army filed through the streets

of their beloved city. With sad hearts and mournful looks,

they went silently out of its gates. The inhabitants followed.

The governor before he departed took two prisoners, one a Frenchman

and one a Russian. The Russian he ordered to be put to death,

with the consent of the rnan’s own father. The Frenchman he

set at liberty, telling him to go to Napoleon, and say that one

traitor had been found in Russia, and him he had seen cut in pieces.

On that same day, the French, still a great host, though worn with

marching and sick with hunger, came in sight of the city, where they

hoped to rest for the winter. They rushed up the hill to get a

sight of it, shouting for joy, “Moscow! Moscow!” There it lay

before them, with its churches and its palaces. They could not

believe that the Russians would forsake it. No, they would

come out and fling themselves at the conqueror’s feet, and sue for

peace, and save their city.

But no one came out. Not a man was on the walls. It

looked like a city of the dead. Two hundred and fifty thousand

people had left their homes there. The city was abandoned.

Still, there was something left. They had not carried the city

with them. The troops poured into its deserted streets and

squares, and entered the empty houses. The officers chose the

palaces and gardens where they intended to stay.

But all had been prepared. In the night fires broke out here,

there, everywhere. The houses, chiefly of wood, burned so as to

defy the efforts of the soldiers to put out the flames. The

governor had left in the city men who came out at night and lit the

raging flres. They had devoted their lives to it, for the

soldiers hunted them out, and shot them down to the number of three

hundred.

They had done their work. Even the great palace was on fire.

Napoleon had to quit it, and pass through the blazing streets.

Five clays the city was burning. Then it lay a heap of ashes.

And now Napoleon sent a letter to the Emperor of Russia, asking him

to make peace. It took a long time for a letter to be carried

from Moscow to St. Petersburg; but the time passed and no answer

came. The French army was living chiefly on dead horses, which

they salted. The winter was coming on — the terrible Russian

winter. “Another fortnight,” the Russians said, “and their

frost-bitten fingers will be dropping from their hands like rotten

boughs from a tree.” The Russians, too, were gathering to fall

upon their enemies as soon as the winter had done its work.

At length, in the middle of October, Napoleon set out on the

dreadful retreat. He left some soldiers behind him, as if he

meant to return, and took with him, besides his guns, a great train

of carriages loaded with the spoils of Moscow that the fire had

spared. But on the way he ordered them all to be thrown into a

lake. They could drag them no farther.

Then, while they were still on the march through the desolate

country, the snow came. The wind drove it blinding in their

faces, and filled the hollows and ravines with treacherous drifts, in

which thousands of soldiers sank and were smothered. Thousands

more fell with weariness, cold, and hunger as they marched along;

and those who came behind found them already covered up in their

graves of snow.

After about a month of such dreadful suffering, Napoleon left what

remained of his army to perish among their enemies, and hastened

away to Paris to place himself in safety and comfort.

After their leader had thus forsaken them, all heart died out of the

wretched men who were left. Their officers could scarcely

rouse them to go on. When their horses died they would cut and

eat them almost raw, and lie down by their fires to sleep. In

the morning their heads would be frozen to the ground, and their

feet consumed by the fire. Others, as they lay, were thrust

through by the Cossack spears. Only about one man in fifty

crossed the Niemen again.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LXI.

FALL OF NAPOLEON — WATERLOO.

A.D. 1815.

NAPOLEON returned to Paris, and hastily

gathered together an army; but he could not replace the men whose

bodies strewed the road from Moscow. The new soldiers were

mere boys. And now Germany was roused at last to put down this

scourge of the nations. In vain he once more placed himself at

the head of the troops. His army was routed and driven back

across the Rhine. Once more he entered Paris defeated, amid

the curses of the people, whom he had deluded into shedding their

best blood for his vain and wicked ambition.

Wellington, with the allies, had now re-conquered Spain. His

next step was to invade France. This he did early in the year

1814, and soon entered Paris as a conqueror. Thither came also

the King of Prussia, the Emperor of Austria, and the Emperor of

Russia, whose Cossacks encamped in the streets of Paris.

Napoleon’s new empress had fled, with her infant son, whom his

father, in his foolish pride, had made King of Rome.

Napoleon knew nothing of this. At Fontainebleau he was told

what had happened; that the allies refused to treat with him, and

that he must give up the crown of France. He saw the

necessity, and resigned in favour of his son, the baby King of Rome.

But the brother of Louis the Sixteenth was chosen instead, and

Napoleon was banished to the island of Elba.

The allied sovereigns had met at Vienna early the next year to

settle the affairs of Europe at their ease, when they were startled

by the news of Napoleon’s escape from Elba. He made at once

for Paris, his old generals flocking round him again. Louis the

Eighteenth ran away, and Bonaparte was once more Emperor of France.

There was no more peace for Europe.

Wellington set off at once to Belgium to collect an army.

England put forth all her power. So did Prussia. But

Napoleon was soon at the head of two hundred thousand men; and in

three months he left Paris saying, “I go to measure myself with

Wellington.”

They met at Waterloo. Wellington and the English were there

alone, numbering fifty thousand, while Napoleon had seventy-five

thousand. The fighting on both sides was severe.

Wellington asked one young gentleman, whom he was obliged to send

with a message, “Have you ever seen a battle?” He answered, “

No.” “Then,” said Wellington, “you are a lucky man, for you

will never see such another.”

In the village of Waterloo, Wellington’s cook was preparing his

dinner. He was told during the day that he had better fly, for

it was going against the English. “No,” said the cook; “I

shall not fly; my master always comes home to dinner.”

It was, indeed, a terrible battle; and the English losses were very

great. All that Sunday afternoon it raged round the pretty

farm-houses and over the peaceful fields. Napoleon thought he

was going to win, and made a last great struggle to break the

English lines; but his columns gave way before their steady fire, and

rolled down a little hill. They might have formed again; but

Wellington had two fresh regiments lying flat on their faces, behind

a ridge, so that the French could not see them; and just then he

called on these to charge. The Guards rushed on; Napoleon rode

away; the battle was won.

The Prussians, under the brave Marshal Blucher, came up before the fighting

was over, and completed the ruin of the French army. Once more

Napoleon escaped; but he was taken, and sent a prisoner to the

lonely island of St. Helena, where he remained for the rest of his

life — a little more than six years.

About two years previously died the poor old king, George the Third,

blind and mad. He had been in this sad state for ten years,

and had known nothing about the war and its victories. He was

in the eighty-third year of his age, and the sixtieth of his reign,

his having been the longest of all the reigns of the Kings of

England.

He had had many troubles. Several of his sons behaved very

badly, and rebelled against him and their mother. Others died

before him, as did his daughter Amelia, of whom he was very fond.

After her death he never was in his right mind again.

In this reign the people were very miserable. The war took

away thousands and tens of thousands who were the support of their

families. It made food and every necessary dear, and the taxes

heavy. At the close of the century there were bad harvests for

several years, and the poor were starving. There were riots

for bread in the towns and great suffering everywhere. The

people thought it was the fault of the Government and the taxes, as

indeed it was; and they held meetings and made speeches about their

wrongs and sufferings.

Then the Government, through fear, was cruel and unjust, and made it

unlawful to hold meetings and make speeches. At Manchester the

soldiers were called out, and killed a great many people who had

done nothing more than march in pro-cession to declare their

opinions. This made the better part of the nation very angry.

Now we have all that these poor people asked for, and a great deal

more.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LXII.

PEACEFUL CONQUESTS.

I MIGHT call this chapter “True Conquests.”

God commanded men to replenish the earth and subdue it. This

is only to be done by industry. Compared with these victories,

the so-called conquests of war are fruitless. You know that

when two kings, with their armies, fight for any land, they neither

make it larger nor richer, but waste it and make it poor. The

man who makes a piece of waste land grow corn for bread has been

more truly a conqueror.

I should like you to understand what a very different country

England was in the beginning of the reign of George the Third, that

is, about a hundred years ago. There were no electric

telegraphs then, no railways, no canals, only very bad roads, on

which it took a week or a fortnight to travel as many miles as we

can travel now in a day. There were no great power-looms

spinning and weaving. The woollen and linen thread was all

spun and woven by the hand. There was no gas to light the

streets and the houses; and, if you wanted a fire, no handy box of

lucifer matches — you had to hammer away with flint and steel to get

a spark.

The roads were the first thing conquered, and this began in Scotland.

A road may seem a very simple thing to you, nevertheless, it takes a

great deal of skill to make the roads of a country. It

requires an able engineer to choose the best places for the road to

go. It must go over or around the hills, through the uneven

and swampy places, and across the rivers. It was Thomas

Telford who planned the beautiful roads that run through some of the

roughest parts of Scotland. He built also some of the finest

bridges in both Scotland and England.

The next great work undertaken was the making of canals. You

know it is much easier to carry by water than by land, especially

such heavy things as iron and stone and coals, which often have to

be brought from the mines and quarries great distances. It is

very difficult to make canals, which must be cut so that the water

from the rivers will run along the channel from river to river.

The water must be carried over the hollows by bridges called

aqueducts, and go under tunnels through the hills. Brindley

was the name of the engineer who was the first to conquer all these

difficulties. Others followed, and in thirty years three

thousand miles of canal had been made. This was up to the year

1800.

But the greatest work of all was the railway. Tramways, or

lines of smooth wood, for the wheels of heavy wagons to run upon,

had been long used in the mining districts. Then iron came to

be used, as still smoother and more durable than wood; but it was

the invention of the steam engine which made the railway what it is.

As early as 1758 James Watt, a Scotchman, began to think that it was

possible to put steam-engines on these iron ways. But it is

said to have been a Frenchman, in Paris, who really made the first

locomotive, though it was not quite perfect. It took along

time to perfect. It was seven years after the death of George

the Third before the Manchester and Liverpool Railway was commenced,

and ten before it was opened. The man who did the great work

in this department was George Stephenson. In 1807 Fulton

launched a steamboat on the river Hudson, in America. Nobody

in England would help him to do a thing which was thought equally

ridiculous and dangerous. The first cotton mill worked by steam

was in Nottinghamshire, in 1785. The next built for the

purpose was in Manchester, in 1789. Arkwright, Hargreaves,

Crompton, and others had gradually perfected the various machines

which the steam-engine was to set in motion ― machines which a child

can guide, and which would tear a man limb from limb in a moment.

Still, many things wanted mending worse than the roads, especially

the morals and the manners of the people. There were men’s

minds and hearts to conquer; and there were not wanting the men to

do this. I have named already some of the great generals of

industry. They were not the rich and the noble, as the

generals of war usually are. They were for the most part poor

and working men, who had learned to use their hands as well as their

heads. I can do no more than just tell you a few of those

other great, not greater, men who set forth to conquer men’s minds

and hearts. Some day I hope you will know them for yourselves,

through their immortal works. First, there is Sir Walter

Scott, with a long list of delightful stories. Then there are

Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Southey, Byron (whom you will only

be able to understand when you are older), and a host of others too

numerous to mention. At this time, too, there was very little

education given to the poor, in some places none at all. This

was the case among the colliers, who had been allowed to live like

savages and die like beasts of burden, while they furnished the

country with its greatest necessary; for without coals our little

island would soon become a desolate wilderness. To these poor,

ignorant, wild, and wicked men two of the soldiers of that noble

army who follow Christ, and make conquests for him, went forth.

Whitefield and Wesley at first were hooted and jeered and struck at,

and pelted; but they conquered at last, and made tears of repentance

stream down the blackened faces of the miners, who would still

remain poor and ignorant, but would never be wild and wicked any

more. Many followed the footsteps of these good men, who

raised up a whole army to fight against ignorance and sin.

At the head of another army was William Wilberforce. He and

his friends had resolved to give themselves and their country no

rest till the slave trade was given up, and England had no more

slaves. In the slave trade, ships, many of them belonging to

the merchants of Liverpool and London, went to the coasts of Africa,

and bought for the merest trifles hundreds of men, woman, and

children, taken by the savage chiefs in war, or stolen from some

neighbouring tribe for the purpose of selling. They were

stowed away in the holds of the vessels, packed so closely that they

could scarcely move, and chained down besides. They were fed

on bread and water. The most dreadful fevers raged among them

during the long voyage to America or the West Indies, and hundreds

died by the way.

The Quakers in America were the first to set free their slaves, and

to call on all Christians to do the same. But in the reign of

George the Third the slaves of England were not set free, only the

slave trade was abolished. No more English ships were sent to

Africa for slaves, but those who had slaves were allowed to keep

them. Does it not sound strange that England should have

slaves at all?

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LXIII.

GEORGE IV. AND WlLLIAM IV.

A.D. 1820 to 1837.

I PUT these two reigns together, because they

were both very short, and the events which happened in them were of

a kind which you cannot understand till you are older. Both of

these kings were sons of George the Third, and uncles of our present

queen, Victoria. George the Fourth came to the throne on the

death of his father, in 1820. He had been a bad son, and he

was a bad husband; but he did not do much harm as a king. His

health soon failed, and he lived in great retirement at Windsor.

He had grown very selfish with always indulging himself in whatever

he wished; but he was naturally kind-hearted, and did many kind

things. He had also great taste, and helped to establish the

National Gallery for painting and sculpture, and made a present of

his father’s fine library of eighty-five thousand volumes to the

British Museum. He died in 1830, having reigned only a little

over ten years.

George the Fourth was succeeded by his brother, William the Fourth.

He was called “the Sailor King,” for he had been Lord High Admiral,

and the sailors of the fleet were very fond of him. In the first

year of his reign the first railway was opened. A still greater

event, also long prepared for, took place in 1834. On the 1st

of August in that year the slaves in all the British colonies were

set free. The people of England paid for their freedom twenty

millions of money — surely the most nobly spent millions that ever

were paid away. In 1833 the Government made its first grant or

money for education (twenty thousand pounds), which was continued

yearly till 1839. This grant in recent years was very greatly

increased, until now we have begun so extensive a system of national

education, that in every parish there are to be schools for the

poor, for which poor and rich alike must pay.

In 1834 there was a new poor-law made. Christian men cannot

suffer people to perish for want without sin, so that from very

ancient times there has been in England a public provision for the

poor. But it had come to pass in this country that a great

many idle people were living on this money, which ought to be for

the sick and the helpless, for the aged and the young orphan

children. This new law was to make all work who were able, and

has done a great deal of good up to this time.

In June, 1837, King William died, having reigned not quite seven

years. He was succeeded by his niece, our present sovereign,

Queen Victoria, who had just completed her eighteenth year, and was

therefore of age to begin her long and happy reign.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LXIV.

VICTORIA.

A.D. 1837.

WHEN a king or queen begins to reign in

England, the bishops and chief men of the realm come before the

throne and take an oath called the “Oath of Allegiance,” to be

faithful and true to their sovereign. When they had thus knelt

before the young Queen Victoria, she addressed them in a speech in

which she said that the duty of governing this great nation had come

upon her while she was so young that she should feel utterly

oppressed with the burden, only that she trusted the Divine

Providence, which had called her to the work, would support and

direct her in it.

In 1840 she was married to her cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg

and Gotha. It was a happy marriage; children came to them, to

whom they were faithful and loving parents. The highest family

in England became, as it ought, a model to all others. Prince

Albert died in 1861, so that the queen has now been for many years a

widow.

The first considerable event in the reign of Queen Victoria was the

Chinese war. It broke out in the year of the Queen’s marriage,

owing to a dispute between the Chinese Government and the English

merchants who had settled in Canton.

The Chinese are the most curious people on the face of the earth.

They number more than three hundred millions, and their nation is

older than the oldest nation in Europe; that is, they lived together

under one ruler and knew most of the useful arts when the nations of

Europe and we in England were wandering savages. They are very

clever, but not at all an amiable people. Their pride is so

great that they call all who are not Chinamen barbarians; their

empire is the Celestial Empire, and their emperor is Brother of the

Sun and Moon.

The dispute arose about a drug called opium, of which the Chinese

are very fond. It is most valuable as a medicine, and is often

given by physicians to relieve those who are suffering great pain;

but it is for all that a deadly poison, and taken in a sufficient

quantity brings on a sleep which is very pleasant at the time, but

very hurtful afterwards, and from which, if only a little more is

taken, the sleeper may never wake again.

Now the Emperor of China had forbidden this drug to be brought into

the kingdom, because it took so much money from his subjects, and

ruined a great number of them altogether. The English

merchants at Canton brought it from India, and sold it to them, and

these merchants were told not to bring any more, and to give up all

that they had to the Chinese Government.

Now the English Government had sent a fleet to protect the merchants,

for the Chinese also demanded that the crew of any English vessel

which brought opium into China should be given up to them

“willingly,” to be put to death. This, of course, our

Government would not undertake to do. The Chinese had also

blockaded the factories of the English merchants at Canton, to make

them give up the opium; and, by the advice of the commander of the fleet

this was done. More than twenty thousand chests were given up,

and immediately destroyed. Later the emperor issued another

edict that all trade with England should cease for ever, and the

English merchants were banished from Canton.

Then the Chinese fleet came out of harbour, and alongside the English

fleet, demanding that an Englishman who had offended should be given

up to them.

This was refused, and the English ships, threatened by those of the

Chinese, fired upon them. One “war junk” — so the Chinese call

their ships — blew up, three sunk, and several more became useless.

In less than an hour the Chinese admiral was defeated, and had to

hasten back into the harbour with his remaining vessels.

The emperor now ordered the English barbarians to be exterminated.

The Chinese were not particular about the way in which this feat was

to be accomplished. The Chinese authorities at Canton sent a

boat-load of poisoned tea, done up in small packets, to be sold to

the English sailors; but the boat was taken by Chinese pirates, who

sold the cargo of poisoned tea to the Chinese themselves, and a

great number died of it. Another time they tried to set fire to

the English ships.

At last the English proceeded to active measures, and took the

island of Chusan, in which there was a city, with a very long name,

and a wall of granite and brick six miles round. The city,

too, was given up. Then the English offered to make peace; but

they soon saw that the Chinese were only trying to deceive them, and

that they would turn upon them, and put them to death whenever they

could.

For all the time the cunning mandarins, as the Chinese great men are

called, were pretending to make peace, the emperor was raging at

them for not obeying his commands to put an end to the whole of the

barbarians, and not allow one to escape back to his country.

Nothing less would appease his wrath he said. And so it

appeared, for one mandarin who ventured to tell him that the

barbarians were rather difficult to put an end to, he ordered to be

cut in two, and all his friends and relations besides. Another

was chopped up in pieces, and a great number were to lose their

buttons, these buttons being the signs of their official rank.

Fresh mandarins were sent to exterminate the barbarians. I

don’t know whether they lost their heads, or only their buttons; but

it soon became clear that the barbarians were quite as likely to

exterminate them. The English fleet sailed up the river, and

captured the Chinese towns and forts so easily that some were taken

without the loss of a single Englishman. At one place where

the British troops landed, one mandarin rushed into the sea and

drowned himself, and a good many others killed themselves in other

ways for fear of the wrath of the Celestial Emperor.

At length the Chinese found out (I suppose even the emperor) that

the barbarians were likely to have the best of it, and a treaty of

peace was signed in August, 1842. The Chinese agreed to pay a

large sum of money, opened five new ports to the British merchants —

Canton, Amoy, Foo-choo-foo, Ningpo, and Shanghae, and gave up the

island of Hong Kong altogether.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XLV.

THE INDIAN WARS.

WHILE the Chinese war was going on another war

had also been undertaken by the British in India. This war was

in Afghanistan, a country to the north-west of the great peninsula

of India, a wild and mountainous country, inhabited by fierce and

warlike tribes. I must tell you how we came to be fighting

there, where, indeed, we had very little business to be.

It was scarcely a hundred years since the British Empire in India

consisted of a single factory surrounded by a wall, and protected by

a ditch. To guard its factory their labourers were armed.

Then the British merchants, united in a company called the East

India Company, began to treat with the native powers, and discovered

how weak they were. Every cause of quarrel with these princes

was an occasion for the British to attack and triumph over them,

till, under Lord Clive and Warren Hastings, they were completely

subjected. The servants of a company of merchants put down and

set up kings, and took tribute, and maintained armies, and made wars

and treaties, till all Hindostan was at their feet. It is a

splendid story, though I am sorry to say that there are sad pages in

it of injustice and wrong on our part, as well as of faithlessness

and treachery on the part of the natives.

Afghanistan lay far away on the borders of India, and did not own

the English rule. But the East India Company were anxious that

the neighbouring states should be friendly, if independent, and to

secure this they interfered in the affairs of Afghanistan.

The reigning Afghan chief, Dost Mahomed Khan, was not friendly; and

the British took part with one who had been deposed, and succeeded

in placing him again on the throne as an ally. This was in

1839. The English army was to stay in his capital of Cabul

till January, 1842; but just before the close of the preceding year,

1841, the British minister and several officers were murdered in the

city by the son of Dost Mahomed, to whom many of the Afghan tribes

adhered.

Then the English army of four thousand five hundred men, with twelve

thousand followers, besides women and children, left Cabul as

agreed. They had to journey through long and gloomy

mountain-passes, deep in snow; and they had scarcely commenced their

march through the Khyber Pass before the treacherous Afghans

attacked them. Their guns were captured, and they had to fight

their way sword in hand, defending the women and children. The

pass was strewed with dead and dying, who were stripped naked by the

savage foe, and hacked in pieces. The whole number who had

left Cabul perished in a week in that dreadful pass. Only one

European, Dr. Bryden, reached Jellalabad to tell the tale. But

a good many officers and several ladies remained prisoners in the

hands of Akbar Khan.

Troops were immediately sent into Afghanistan to deliver the

captives, as well as the town of Jellalabad, which was threatened by

the enemy. The troops were commanded by General Sir Robert

Sale, whose own wife was one of the prisoners. Captain

Havelock was with Sale, also General Pollock. The latter

defeated Akbar Khan, but the prisoners were already free, and were

coming to meet their deliverers. They had bribed the chief who

was taking them farther away, and he had brought them to meet their

friends.

Then the British took the city of Cabul, and nearly destroyed it, first

allowing the people to seek safety in the mountains; and, having

done their work, the army returned from Afghanistan, leaving the

Afghans, whom they had punished for their cruelty, to manage their

own affairs for the future.

The end of the Afghan war did not end the troubles in India.

Scinde was another border state, with whom the British had made a

treaty. We were bound by this treaty “never to look with

covetous eyes ” on this country; but the nobles of Scinde, when the

first English vessel sailed up the great river Indus, said, “Alas!

Scinde is gone. The English have seen the river.”

It was too true. In 1843 Sir Charles Napier was sent, on very

slight pretext, to take possession of a part of the country.

It ended in his subduing it entirely, and adding another great

province to the British Empire.

No sooner was Scinde conquered than another province, called

Gwalior, was attacked, a battle fought at Maharajpore, and another

territory submitted to Britain. But the Home Government

recalled the governor-general, Lord Ellenborough, for these

conquests, and sent out Sir Henry Hardinge desiring him to pursue a

more peaceful policy.

But, through no fault of his, he was soon engaged in a terrible conflict

with the most warlike tribe in India, the Sikhs. The Sikhs

inhabited the Punjaub. They numbered altogether seven

millions, and had a large army in the field. Anxious to

preserve peace, the new governor-general allowed them to begin the

attack before he had a force in the field to meet them. But he

went himself to the assistance of General Gough, and gained a

victory over them, though with fearful loss, after two days’ hard fighting.

About three weeks after this, on the 10th of February, I846, the

decisive fight called the battle of Sobraon took place. The

Sikhs were overcome, and forced with heavy loss across the river.

The British marched into the capital, Lahore, and a peace was

concluded. But the Sikhs would not keep the peace. They

were constantly rebelling and giving trouble; and at length, in

1848, they were again at war. In January, 1849, they fought

the battle of Chillianwallah, where they were forty thousand strong,

and at which they succeeded in keeping the field, and in taking a

good many British guns. Soon, however, the British retrieved

their losses; and the end of this war was like that of all our

Indian wars — the Punjaub was annexed.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER LXVI.

FREE TRADE—THE CORN LAWS.

A.D. 1846

I DARE say you think that this will be a very

dry chapter, because it is about things you do not understand.

But with a little trouble you will be able to understand, and then

you will find that these subjects are not so uninteresting after all.

I know that you are all very well pleased when papa, or uncle, or

some one who cares for you, gives you a little present of

pocket-money. Not that you care to carry about certain little

round bits of metal; but that each little round bit of metal has a

particular value: it will buy something.

You do buy something, and somebody else gets your money — somebody

who does not care to keep it any more than you did, but who buys

something else with it. And so on it goes, buying a great many

things all of the same value, and always keeping its value, till

perhaps some old miser gets hold of it, and ties it up in a

stocking, where of course it remains useless till some one finds it,

and sends it about again.

Thus, if you want anything, you must give something else for it of

equal value, and that value is counted in money, but is not the

money itself. When one thing is given for another it is called

barter; and you can easily imagine it is very inconvenient.

Then money comes in, and instead of the man who has a sack of corn

to sell carrying it to the shoemaker when he wants a pair of shoes,

he sells his corn, and for the money gets the shoes he wants, and

the person who wants his corn buys it; for perhaps the shoemaker had

no need of the corn, though he wanted a new coat badly enough.

Money came to have this value because gold and silver are beautiful

in themselves, and are coveted for ornament; and a great deal of

labour and trouble are spent in getting them. Most useful

things cost a great deal of labour and trouble, and are not found

ready-made; so, if some one takes time and trouble in making

something for you, you must give back something that will repay this

time and trouble.

Now one nation produces and makes some useful things, and another

produces and makes other useful things, and they want to exchange

them; for each has twice as much as it wants of its own good things,

and is very much in need of its neighbour’s. So they send what

they do not want to each other in ships, and in a variety of ways,

from the very ends of the earth. China sends us tea, the West

Indian Islands sugar, America, cotton; for none of these things

could be produced in England. And we, with our wonderful

machinery, and coal and iron mines, with which to make and work

machinery without end, make that cotton into cloth, and send it back

to them to wear, and furnish them with knives and scissors and

spades and tools of every kind.

Now it seems very foolish for any nation to make the foreign things

its people want dear, so that they cannot buy so much of them as

they need or would like, and so cannot sell so much of their own

things in exchange. Yet this was just what the rulers of

England were always doing, till one wise man, Dr. Adam Smith, showed

that this was the way to keep the country poor. And long after

he had proved this plainly, they would go on doing it, not because

it was good for the nation, but because it brought wealth to a few,

and because they would not be at the pains to reason out the matter.

Those who understood and cared for the welfare of their country had

a long and hard struggle to get Free Trade; and, especially, free

trade in corn, for the laws that made bread dear were the most

foolish and the most cruel of all.

Long ago our Governments made all sorts of curious laws, at which we

laugh nowadays, such as what certain people were to wear, and how

many dishes they were to have at table. They were stupid

enough, these old laws, but I don't think they did very much harm.

But the Corn Laws did such terrible harm that, instead of laughing,

they made strong men weep to know the misery they caused.

You know this small island of ours does not produce enough food for

all the people in it, but other countries produce so much more than

they can use that there is always food enough and to spare in the

world. These countries, in Europe and America, are glad to

send us their cheap corn, and to buy from us all sorts of things

which our workmen make. But the Government would not allow

their cheap corn to be sold till they had made it dear.

However dear the corn might be in England, they made the foreign

corn quite as dear by taxing it, so that the poor people were never

any better for it, but in years of scarcity suffered and died of

starvation when they might have had plenty.

The laws preventing the sale of cheap bread were called the Corn

Laws, and they began just two hundred years ago, and lasted at least

one hundred and seventy years. For a long time, of course, no

one knew the harm they did, as they made some people far richer than

they were before; for they made the land on which the English corn

grew so much more valuable and it was the men who owned the land who

made the laws in those days.

But towns such as Manchester, were now filled with people working in

the factories; and when bread was dear it sometimes took all their

wages to get it, so that they and their children were in rags and

misery. Then when work was also scarce they starved outright.

When Queen Victoria came to the throne the people were in great

distress in all the manufacturing towns, and the next year, 1838,

they were still worse, owing to a severe winter and bad harvest.

Then it was that some noble men, who saw how much the poor suffered,

and had thought a great deal about how the suffering might be

removed, began to work against the Corn Laws. In Manchester

they formed themselves into an association to get them done away

with, and a gentleman, the Hon. Mr. Villiers, spoke against them in

Parliament. But he was not listened to, because it was the

interest of the landlords there not to listen, and there is nothing

that makes people so deaf and blind as selfishness.

But the opposers of the Corn Laws, with Mr. Bright and Mr. Cobden at

their head, and Lord Brougham and a few other great men already on

the same side, were determined to make them listen. They got

up associations all over the country, and called themselves the

Anti-Corn-Law League, and some of the gentlemen who belonged to the

league spent a great part of their time lecturing and writing

against the Corn Laws, till nearly every one outside Parliament

understood all about them. Then I am happy to say that inside

Parliament good men, in spite of their interests, began to see the

evil of them, and to turn against them, chief among whom was Sir

Robert Peel. When he changed his mind he was at the head of

the Government, Prime Minister of England, and it was he who at

last, in 1846, brought in a bill for the Corn Laws to cease, and

Parliament agreed that they should begin to be altered at once, and

in three years should be done away with entirely.

There was, however, an event which hastened their end, and that was

the Irish famine. It was caused by the failure of the potato

crop, which began in 1845. In August of that year, from the

south-eastern counties of England and from Ireland there came

accounts of a blight that had suddenly come upon the potato-fields.

The leaves and flowers over whole acres of ground became black and

shrivelled, and the entire plant rotted away. The Government

sent the first scientific men of the day to inquire into the cause of

it, but all their skill was of no avail, they could not find it out.

Next year, 1846, the farmers and poor people who depended upon their

potatoes for subsistence, to whom they were bread, meat, and

everything, planted them as usual. In the beginning of the

season the crops looked healthy and abundant; but suddenly, in the first

days of August, the blight came again. In a week the blackened

fields looked as if scathed with lightning, and rotted and sent out a

putrid smell. Everywhere the poor people were wringing their

hands. Their whole year’s food had disappeared. For a

few weeks after the time that should have been harvest they managed

to live by the sale of their pigs and fowls. Then their

furniture and clothes went. Then hunger came. “The

hunger” they called it. The mothers went miles to get a little

Indian meal for their children once a week. The rest of the

week they lived on raw turnips. In many and many a cabin there