|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XXXIII

THE GREAT GLADE.

AND now I must go

back in this chronicle of events to the time of Claude's coming to

Highwood, in order to tell the story of the other lives which

entangled themselves with ours. I will set down their story

not as it became known to me from day to day, but as I came to know

it after the events, from one or other of the actors and sufferers.

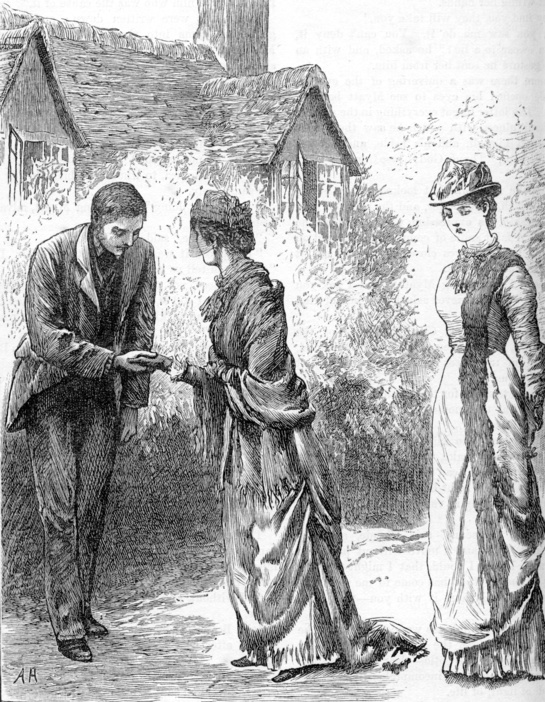

"The pair responded modestly."

The two girls Phillis and Priscilla were by far the

pleasantest pair to be encountered in the village, and Claude

pleased himself with watching them accordingly. He always

spoke to them at the Sunday school, and regularly overtook them on

their way back from it, bowing to them as he passed, while the pair

responded modestly. They generally turned up one of the lanes

which intersected the street, and passed through a long narrow field

skirting the thicket into the Great Glade.

The Great Glade was the magnificent evening promenade of the

little village, a vista of velvet sward, stretching far as the eye

could reach, between ranks of old and stately forest trees.

Without doubt those trees had seen Elizabeth and her train sweep

past from her "Bower" at Havering, and looked down upon the courtly

pageant as on a swarm of summer flies. Now their noonday shade

was the shelter of tramp and vagrant, the resort of many a noisy

cockney party taking a day's "outing," and their evening shadows

fell on the courtship of the village pairs.

"Tom was to meet me here," said Phillis, breaking the silence

in which they had walked across the field in the yellow October

sunshine. It was enough for these two merely to walk together.

They so often thought about the same things that they almost forgot

to speak about them, and indeed the same thought had so often come

to their lips in the same words that they had ceased to regard the

thing as wonderful. "Tom wanted me to stay away from school

and spend the afternoon with him," she added, after an interval.

Her companion's only answer was a look of wistful tenderness,

but she seemed about to speak when Phillis interrupted her.

"Prissy, dear," she said, as they moved slowly on, "what are

you thinking about? You look as if you had seen a ghost, only

it can't have been a bad one."

"Phillis," replied the girl, turning round, and standing

still for a moment, with a new light on her fair pale face, "I have

found the Lord Jesus."

"I wish you wouldn't talk like that, Prissy," said Phillis;

"I don't know a bit what you mean, only it makes me feel

uncomfortable."

"Don't say that, Phillis dear," returned Priscilla, speaking

low. "I hope you will understand one day what it is to find

Him."

"I don't know," said Phillis, stoutly, and a little

discomposed by the change in her friend, for which, after all, she

was not wholly unprepared. Mr. Jewel's humble housekeeper had

been a pious Methodist, and had imbued the girl's mind with the

religious ideas and feelings of her communion. "I don't know.

It has no more meaning to me than if you said you had found the

moonshine lying on the fields in the morning, and less. What

is it like?" she added, more sympathetically, as she saw the tears

gather in Priscilla's eyes.

"Like nothing on earth," she said, raising them, and speaking

with a subdued rapture, "It was not at the church it came to me.

It was last night. I was passing Crouch's place, and there was

a crying out and struggling and cursing round the door. The

men were drunk and fighting, and Sally Crouch was drunk too, and

screaming herself hoarse, and I began to think of Jesus, and all at

once I found Him, and I stood still for a while, and the crying and

cursing and struggling seemed quite far away, and round me there was

such a wonderful peace, and a voice within me saying, 'I have bought

thee with a price, and thou art Mine.' Phillis, dear, it is

heaven itself. I could have stood listening for ever and ever.

Oh, if you could find Him, too!"

"You never loved me as I loved you," said Phillis, with

seeming irrelevance, "and now you'll care less for me than ever.

You won't have me for a friend now at all, perhaps."

"I don't see that it need make any difference," answered the

other, sweetly; adding, "I think I shall love you more, dear; I

never was so warm-hearted as you. I seem to love everybody

more now."

And, indeed, the attachment might have appeared warmest on

Phillis's side. Her manner was the more caressing of the two.

And now, leaning against her companion, with a half-embrace, she

said, tenderly, "You were always better than me, Priscilla, and I'll

go on loving you best, whatever you think."

Phillis had spoken hurriedly, for she had seen young Myatt

approaching, and Priscilla exclaimed, "There's Tom!"

"You'll come out with us this evening?" said Phillis,

coaxingly.

Priscilla shook her head. "No, dear; I 'm going to

church."

"Then I'll come too," said Phillis.

Priscilla's duty was divided. It was best for Phillis

to come to church, but her lover might be offended. This was a

disputed subject between them, and for the last few Sundays

Priscilla had taken herself out of the way completely, and gone to

church alone; so she said, hesitatingly, "Won't Tom want you, dear?"

"Let him come with us," said Phillis.

"But if he won't?" said Priscilla.

"Then he can stay with mother," returned Phillis, coolly.

They were both silent, for just then the young man came up to

them. He met them as he had met them any Sunday for the last

two years. He gave no greeting, for he had seen them before,

and took his place at Phillis's side as became her acknowledged

lover, all three sauntering on upon the velvet grass. Although

the three were always together thus, there never was any doubt as to

Myatt's preference. It was Phillis, and Phillis alone, he

courted, but he was so accustomed to the presence of Priscilla that

he had hitherto never objected to it, and had to be content to

snatch the smallest opportunity for a tête-à-tête, as if

Phillis had been the most zealously chaperoned maiden in the land.

Priscilla had, however, on one of these occasions found herself in

the way, and had managed to leave them to themselves in the evenings

of late, a privilege which the lover was not slow to appreciate.

They sauntered to the end of the glade, talking about the

merest nothings, and sometimes not talking at all. The girls

seemed to have less conversation than usual.

"Hadn't we better go home, Phillis?" said the young man,

looking at his watch; "mother"—it was her mother he spoke of—"mother

will be waiting tea, and we can come back here in the evening; the

moon is at the full."

"I'm not coming out to-night, Tom," said Phillis; "I'm going

to church with Prissy."

"To church?" he echoed. "Haven't you had enough of it,

forenoon and afternoon? What do you want to go in the evening

for? To hear the new curate, I suppose?" he added.

"Come with us, Tom," said Phillis, coaxingly; and her voice

and the words were very sweet to the young man's ear.

"I can't," he answered. "You can stay with me. I

never asked you to give up anything for me before. Do,

Phillis," he pleaded.

"But why can't you come with us?" she said, persistently.

"Because if a man goes there, it means that he approves of

what is going on. Now, I don't, and my going would be a

pretence and a lie."

"You'll want me to stay away always," she urged.

"I don't deny it," he said, frankly. "I should like you

to think as I do; and you will some day," he added, confidently.

He said it quite seriously. He was far too much in

earnest to be content that Phillis should keep her religion as a

sort of pastime or ornament, as John Bower was content that his wife

and daughter should. That is a feeling born of contemptuous

indifference, and he was a man prepared to share the burden of

thought, as he would share the burden of life, with any woman he

loved. Priscilla had been listening without taking part in the

conversation, but at these last words of Myatt's, the tears started

into her eyes, and she clasped her hands round her companion's arm

as if to hold her fast.

Seeing the three together, it would have been difficult for

any one to say whether Phillis was in love with Myatt or no.

She might have loved him a little, or not at all. There

certainly was no admixture of passionateness in her affection.

Her manner might be born of security, and the absence of lovers'

hopes and fears, anxieties and doubts; but any one could have told

that, half consciously, half unconsciously, Priscilla loved him,

that she basked in his presence, that his most careless utterances

were precious to her. She had absented herself from the trio

with a sharp pang of wounded love, which was not wholly for her

friend; and yet she had no thought of supplanting her in her lover's

affections. She thought Phillis did not love him enough;

sometimes, indeed, that she did not love him at all, as in their

girlish confidences she had often declared. And of her own

feelings in the matter she did not think. She could not help

feeling as she did any more than the cloud can help becoming

rose-hued in the dawn; though when the sun has risen in the sky, it

will be grey again, or have melted quite away into the haze of the

horizon.

They parted at Phillis's door, and the pair went in to tea.

Priscilla also went in to find her father sitting by the fire, as

was his wont on Sunday afternoons, having been in bed all the

morning.

"How are you now, father?" she asked. He had gone to

bed intoxicated the night before, and this was his first appearance.

She had carried him a cup of coffee and the morsel of bread he could

eat at such times before going out.

"I'm but so-so, child," he answered, not meeting her eyes.

"I hope I haven't kept you waiting, father," she returned,

laying aside her outdoor things.

"You? no, no, child; you never keep me waiting," he replied,

with a sort of deprecating politeness.

But there was nothing to deprecate, unless it was her filial

affection, for she went about to get him his Sunday evening meal

with gentle haste, casting every now and then a look of pitying

fondness at the bent head by the fire. Besotted as he was, he

could not but notice the tenderness with which she waited on him;

she had always been good and gentle, but there was something new in

her manner which puzzled him.

At length, when tea was finished and cleared away with the

same gentle rapidity, she came softly behind his chair and stood

smoothing his grey hair with her hands. Then she said, in a

faltering voice, "Father, you haven't been to church for a long

time; will you come with me to-night and hear the new curate?"

"I would like it very well, Prissy," he replied, "but my best

coat is very shabby now. No, not tonight, dear," he added.

"I don't mind about your coat, father. I'll get it out

and brush it for you. It will do very well."

"Not tonight, Prissy," he repeated; "I don't feel well enough

to-night."

He knew it would be unendurable, for his thirst for something

stronger than tea was asserting itself already.

"Then I'll stay and read to you, father," said Priscilla; and

the two hands once more smoothed down the grey hair, and the mystic

blue eyes were raised to heaven, so that the girl standing there

looked like the man's guardian angel.

"Don't stay at home for me, Prissy," he said, uneasily; "I 'm

going out a bit."

"Oh, father!" sighed the girl, heavily.

He knew all the words and the sigh meant, and the tears—tears

of impotent regret and compunction—swam in his eyes, as she came

round in front of him, and knelt on the hearth, imploringly.

"Don't go, father!" she whispered.

He looked at her through those tears.

"I must go," he said; "but, Prissy, I'll come home all right;

I will indeed, I promise you;" and he rose, and shuffled into the

next room to get his boots and his hat, while Priscilla remained

kneeling by his empty chair.

John Bower did not trouble his family much on Sunday

afternoons. Tom Myatt had tea with Phillis and her mother, and

after tea the young people went out as usual.

They took a little turn together, and then the young man

endeavoured to persuade Phillis to give up her intention of going to

church with Priscilla, but to no purpose. Phillis, as a rule

the most easily swayed of creatures, was firm as a rock. Myatt

had made it a personal matter—a test of his influence and of her

affection—and his anger was in proportion to his failure. He

became ungracious, and she cold and distant, till at length he lost

his temper, and the lovers parted in anger as the church bell began

to tinkle, which caused young Myatt's anger to concentrate itself

forthwith on the cause of the quarrel, which he took to be the new

curate.

Not a little to her surprise and disappointment, Phillis saw

no more of her lover that night, would see no more of him, in all

probability, for a week to come.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXXIV.

THE LOVERS' QUARREL.

ON the following

Saturday Claude returned to his lodgings, his mind fully occupied

with the mental and spiritual condition of the parish of Highwood.

He was conscious, as he passed upstairs, of the presence of the

master of the house. He had already learned to recognise it in

stifled silence and sudden storm. John Bower was at home.

He was often at home on Saturday, and when at home he was apt to be

out of temper, so that he was oftener out of temper on Saturday than

on other days. He was out of temper now. He was doing

some little bit of carpentry about the house with unnecessary,

indeed, savage force.

Mrs. Bower was in the parlour, where the kettle was boiling

for her lodger's tea, and her lodger looked in upon her there when

he had deposited a dripping umbrella, for it was raining heavily.

She started at his entrance, but smiled when she saw who it was, and

with a friendly "good-afternoon," Claude went upstairs to his books

and his meditations.

John Bower went on hammering and swearing. His wife

listened, and knew that he was in a worse temper than usual.

By the time the job in hand was finished he would be in a very bad

temper indeed. Phillis was out, and it was a good thing, for

she could not bear to see him in those moods of his, but would pale

and tremble, and make him worse if he happened to see her.

Most likely he would be out of the way before she returned.

She had doubtless met her lover, and, now that the rain was over,

was loitering with him. They had still their little quarrel to

make up.

Young Myatt—he had been called Young Myatt in his father's

lifetime, and the name had remained with him—had been Phillis

Bower's acknowledged lover ever since the girl was out of pinafores.

He was her mother's favourite. It was she who had fostered his

liking and forwarded his suit. John Bower had never done more

than overlook his presence, and it was doubtful if he knew its

purport. He had come about the house since Phillis was a

child. His mother and hers had been bosom friends. Each

knew the other's secret cares and sorrows as well as she did her

own, and in this way each had been more to the other than either

husband or child. Mrs. Myatt had been left a widow for some

years, and her son had been her support and stay. He had

inherited his father's business, that of a builder, and was

well-to-do in the world. When his mother died, and for a whole

year he had been alone, the young man wanted a wife. But he

had made choice of and loved Phillis, and for Phillis he must wait.

It was only of late that he had offered the girl the signs and

tokens of love. He had been content to watch the rosebud he

had chosen, till it grew into the perfect rose; but the feeling that

it was his to appropriate when the time came, had become a part of

his nature. The feeling was unreasonable, unjustifiable, but

no man could have convinced him of that. He was one of the

people who boast of reason and remain the most unreasonable of

beings. Phillis was his, and any one else approached her at

his peril. His love for her was single, passionate,

self-controlled, and it controlled his life.

Phillis, on her part, had liked him very well as a youth,

when he had brought her the rosiest apples from his mother's garden,

and she had liked his attentions as she grew older—at least, she had

accepted them in her sweet yielding way, and allowed him to suppose

they were agreeable to her, as, indeed, they were. She would

have missed them sadly, and have fancied herself in love with him if

they had been withdrawn; but they had neither awakened her

imagination nor touched her heart. She was, as yet, deficient

in passion. The mother, who closely watched her beautiful

girl, wondered at the undisturbed repose, the childhood of heart, in

the full-grown woman.

Phillis knew quite well that Myatt wanted to marry her—he had

left no doubt about that—and she had not shrunk from the proposal.

Not till of late, and that shrinking had followed the accidental

witnessing of a scene between Myatt and one of his workmen.

She had seen her lover in a passion. She had seen him with his

fair face flushed, and his blue eyes aflame, speaking fierce and

angry words, and ready to strike a blow. No matter that he had

justified his indignation, and was dealing justice on a recreant—a

"skulker"—Phillis had shrunk from that very hour.

And now, as Mrs. Bower at length sat silent and unoccupied in

her little parlour, the young man came in.

"Well, mother," he said, shaking hands with her, "where 's

Phillis?"

"She's out," said Mrs. Bower. "I thought she was along

with you."

"She knew I would be here," he muttered, discontentedly.

"I dare say she's up with Prissy," returned Mrs. Bower,

soothingly. "Sit down, and she'll be here in a little."

He sat down, as he was bidden, at the window, keeping a

restless look-out along the street.

The house was quiet now, ominously quiet, Mrs. Bower thought.

She knew as well as possible, from what she had seen of her husband

during the afternoon, that an outbreak was impending, an outbreak

that, like the storms of nature, was often heralded by a calm.

She sighed wearily, and then made an effort to engage the young man

in talk. But he answered in monosyllables, and still kept his

outlook along the street.

The day wore on and darkened, and Mrs. Bower set about

lighting the lamp and preparing the family tea. And still no

Phillis. Mrs. Bower kept wondering about her, and at length

urged her lover to go out in search of her. This last was a

little bit of domestic diplomacy. One of John Bower's

peculiarities when his dark moods were upon him was his dislike to

the presence of any one at meals. But this the young man

declined to do, and glad enough was Mrs. Bower to find, on going

upstairs to fetch her husband, that he had slipped out in the

meantime.

Young Myatt ate and drank what was set before him almost in

silence, but when the meal was over his tongue was loosed.

"I tell you what, mother, I want things settled between me

and Phillis. I can't go on like this any longer. It's

time we were married and done with it," he said, abruptly.

Mrs. Bower almost allowed the tea-cup she was holding to drop

out of her hand. It was what she had all along been looking

forward to, and yet, now that it had come, it filled her with

sickening fear. She began to tremble violently, and her eyes

filled with tears.

"Phillis is young enough yet," she said, gently.

"I've a good home ready for her," he answered, not noticing

the objection. "This job that's just finished turned out a

fine thing, and there's more behind it. Why should we wait?"

There was a pause, and in it he took out a small packet from

his waistcoat pocket and laid it on the table.

"What's that?" asked Phillis's mother, as if fain to keep

back the words of fate.

"It's a present for her," he answered; "a pair of gold

earrings. I've never given her anything worth before."

Mrs. Bower turned upon him, weeping. "Oh, Thomas!" she

said, with entreaty, "you'll be good to my girl, won't you?

You'll never break her heart, as mine's been broken? Promise

me never to lift your hand to her, never!"

"That I can promise," cried the young man, with scornful

vehemence. "I'd deserve to be hanged if I struck a woman."

"Hush!" entreated Mrs. Bower. "Don't speak so loud."

"I wanted to settle it tonight, if possible," said Myatt.

"Can't I see him?" And he nodded upwards in the direction from

which John Bower had last been heard hammering, to indicate whom he

meant.

"He 's out now," replied Phillis's mother. "You can see

him when he comes in," she added. "But don't speak tonight,"

she urged. "I wish Phillis would come in."

"I'll go and find her," said the young man, rising, and about

to go,

But just then Phillis herself appeared. She lifted the

latch, and came in, more like a dewy rose than ever; for it had

rained again, and she was wet, and the moisture lay on her face, and

heightened its bloom. She had on a dark waterproof, and a

little hat and feather, and she hastened to take them off, greeting

Myatt frankly enough, but at a distance. When she had laid

them aside, he held out his hands to her; but she had taken her

place on the other side of the little table, and merely smiled,

without offering to touch them.

"Where have you been, Phillis?" said her mother, in a half-

displeased tone.

"I've been at Miss Thorpe's, mother," answered the girl.

"Didn't you expect me?" asked her lover, somewhat

peremptorily.

"Yes, Tom," was the gentle answer; "I didn't think you would

stop away."

He looked keenly at her. Was she bearing a grudge at

him for the little bickering they had had last Sunday about going to

evening service, concerning which he had made up his mind to say

nothing? or was there something else in the background—that

something which had precipitated his resolution to marry Phillis out

of hand? He had a strong feeling that the presence of the

curate under the same roof with her would somehow prejudice her

against him. He had felt it as a positive injury when he heard

of the arrangement.

Phillis did not avert her eyes. He was about to upbraid

her for not staying in for him; but, disarmed by her look, which was

even kinder than usual, and which had, indeed, a new tenderness—the

tenderness of compunction—he pointed to the little white parcel on

the table, and said, gently—

"I wanted to give you this."

"What is it?" she said, with girlish eagerness.

He handed the packet across the table, and she opened it and

looked with a smile at the two pretty bits of virgin gold lying oil

the snow-white wool within. She looked at them, and then her

look became graver, and the colour overspread her face. It was

a blush of pain, and not of pleasure, but he misunderstood it and

her, for he crossed over to where she stood, and offered to kiss

her. It was not the first time, and she had been accustomed to

take the caress quite calmly—as calmly, indeed, as if he had been

her brother—but now she started from him with a cry.

"What 's the matter, Phillis?" asked her mother, sternly.

"What's the matter?" echoed her lover; for Phillis had begun

to tremble, and had laid the little packet on the table.

"Nothing! oh, nothing!" she exclaimed; "only I wish you

wouldn't come after me any more, for I can't marry you—indeed I

can't."

Her listeners looked at one another, as they stood over her,

and her mother was the first to speak.

"What nonsense is this, Phillis?" she said. "Tom was

your own choice, wasn't he?"

"No, no," sobbed Phillis. "I didn't choose at all."

"But he chose you, and you didn't say him nay," said Myatt,

whitening about the lips. "And, Phillis, I came here tonight

to have it settled one way or other. You don't know how I love

you," said the young man, again holding out his hands to her.

"I've never loved but you. I loved you when you wasn't higher

than that table, and I've waited for you all these years. I've

worked for you, and saved for you, and kept myself out of evil for

you," he went on with simple eloquence. "Don't say you won't

have me, Phillis, after all!"

"I like you very well, Tom," said Phillis, lifting her wet

soft eyes to his face; "but not like that."

"Not like what?" he said, sternly.

"Not to be your wife," she answered, with quivering mouth.

They had been very quiet hitherto, but at this young Myatt's

passion overcame him, and be broke into a storm of upbraiding.

"You have made a fool of me, Phillis Bower," he said.

"What did you mean by it? What did you mean by letting me look

in your eyes and think they were loving me, and by letting me kiss

your lips? What did you mean, I say?" and he came so near that

Phillis shrank back a pace, and half raised her arm.

The movement enraged him, and he laid hold of the arm by no

means gently.

"I didn't mean anything!" she murmured, faintly.

"You didn't mean anything," he cried; but just then the door

was flung open, and John Bower—his iron-grey hair standing up on his

head and his face ominously livid—entered the room, and with a look

of fierce inquisition struck the whole party dumb.

There was silence for a moment, and then young Myatt essayed

to speak.

That was enough. It turned the pent-up fury full upon

him. Without inquiring further into the merits of the

question, John Bower told him to leave the house, or be kicked out

of it, in language too coarse to repeat.

The young man stood his ground, while Phillis, white with

terror, clung trembling to her mother. "Go," cried Mrs. Bower,

beseechingly.

And after a moment's hesitation, Tom Myatt nodded assent, and

turned and left the room.

The earrings were lying on the table. John Bower

pounced upon them, and flung them after the young man into the

pitchy street.

Then he turned upon the two trembling women with oaths and

imprecations. He seized the table that stood between them, and

shook it till it threatened to come to pieces in his hands.

"Don't blame mother," cried Phillis, as he came nearer; "it

was all my fault."

She had interrupted him in the outpouring of his rage, and,

for the first time, he raised his hand to strike her. Her

mother, with a cry, came between, but he hurled her aside and

inflicted a heavy blow on the girl's ear.

Immediately the whole house resounded with shrieks of murder.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXXV.

IN THE NIGHT.

THE noise of the

altercation that had been going on came to Claude's ears as be sat

in his room, and at last he had opened the door and stood on the

landing, divided between a desire to interfere and a dread of doing

harm by interference.

At the sound of these unearthly shrieks, he hesitated no

longer, but hastened down. Already, however, they had ceased;

the street door stood open, and Claude heard a rush of footsteps

without, as of pursuer and pursued.

The shrieks had not come from Phillis, who was sitting in a

chair, moaning inarticulately, as if stunned by the blow she had

received; nor yet from the white lips of Phillis's mother, who was

bending over her in silent anguish. A boy from a neighbouring

farm had been sent to John Bower with a message, and, the door

standing open, he had been a genuinely interested spectator of the

scene enacting within. He had stood aside for a moment to

allow young Myatt to pass—then he had seen the blow given to Phillis

by her father; but the cries, which seemed delivered under the

influence of terror, were pure mischief. The boy had a grudge

against John Bower, and began screaming "Murder!" with all his

might, thinking to create a scene and escape in the confusion.

His terror became real enough, however, when the enraged man sprang

out upon him, and he fled, closely pursued by one who narrowly

escaped being a murderer that night in truth.

Claude hastened to close the door, and began to help Mrs.

Bower to recover her daughter, who seemed at first only

half-conscious; and no sooner had they succeeded in rousing her from

her stupor, than she began to exhibit the most painful agitation.

"Save me! save me! Oh! hide me from him! hide me!" she

cried.

"You are quite safe," said Claude, soothingly. "Are you

hurt?"

"My head feels very bad," she answered, putting up her hand

to the side on which one small ear was a burning crimson; "but, oh!

let me go away before he comes back," she added, with a gesture of

supplication.

"You needn't be afraid of him when he comes back," said her

mother. "He won't come home tonight as long as he thinks any

of us are about; " and she added, with a look of horror, "sometimes

I think after one of these fits he'll never come back at all."

She knew that in a very short time her husband's fury would

be spent. That before he sought his home, he would be a

miserable downcast man, whom, in spite of all, she would be glad if

it were possible to cheer and comfort; so she urged the girl, who

was shivering with strong emotion, to sit by the fire, and let her

make another cup of tea. But Phillis could not be quieted so.

Her nerves were too completely shaken.

"Oh! let me go," she cried. "I can't stay in the house

to-night. I would stay if I thought he would be bad to you,

mother," she said, caressing her mother's brown and withered hand.

"I would stay though he killed me; but he has turned against me, and

he won't hurt you."

"There's Prissy," said her mother, as a gentle tap came to

the door, and the latch was lifted, sending another strong shiver

through Phillis's frame.

"Come in, dear," said Mrs. Bower; and Priscilla Jewel,

knowing too well the nature of the event which had taken place, came

across the floor with eyes full of tender concern.

"Father's given me a blow," said Phillis, in answer to her

look, "and I want to go away before he comes back. If it

wasn't for mother, I'd go away, and never come back again."

"Don't say that, dear," said Priscilla, kissing her.

"You must not go."

"I think you ought to stay at home," said Claude, who was

still standing by the chair on which Phillis sat.

"Stay at home, and I will meet your father alone when he

returns, and remonstrate with him. If it has no effect, I can

at least protect you from further violence."

All three seemed to answer in a breath, and to repudiate any

such intervention.

"But it is not right to let him go on in this way unchecked.

It is a duty to warn him," said Claude.

"Oh, sir, you will only do harm," said Mrs. Bower. "He

can't bear being spoken to by any one, far less by a clergyman.

For our sakes, sir, let him alone."

"Don't speak to him," said Phillis, with imploring eyes, and

in the midst of her pain and fear preserving her delicate

thoughtfulness for others, she added, "He might strike you, and you

might be obliged to strike him again, and it might bring disgrace to

you which it would not to another."

"Come to me, dear," said Priscilla. "Let her come with

me, Mrs. Bower. I am quite alone. My father won't be in

till eleven," and she sighed heavily as she spoke.

"But if he"—Phillis did not name the name he

profaned—"if he finds out I'm gone he'll be angry, and if he knows I

am with you he'll make me come back," said Phillis. "I would

rather go to Miss Thorpe."

Priscilla yielded quietly.

"I will go with her," said Claude, addressing Mrs. Bower.

"It will be safer, perhaps."

Mrs. Bower thanked him with her lips, and Phillis with her

sweet sad eyes, and soon after they were passing down the street

together, she with the hood of her cloak drawn over her head and

carrying her hat in her hand, and he walking by her side.

She was evidently very much shaken, for she began crying and

sobbing as they went, and Claude made her lean on his arm, and

supported her to the schoolmistress's door.

It was well that young Myatt did not see the pair as they

passed through the village, for the demon of jealousy had already

been whispering in his heart. Casting about for some reason

which would account for Phillis's rejection of his suit, and falling

back upon their quarrel about going to church, he had come to the

conclusion that it was for Claude's sake she had flung him over,

not, indeed, out of love for the curate, or in the hope of winning

him—that did not enter into young Myatt's mind—but simply because of

his own antagonism to religion. "She has done it to please the

parson," he said to himself, as he dashed through the wet woods, on

his way to the solitary home, which he still occupied at intervals.

And the tiger in the man made him clench his teeth, and spring

forward with cursing on his lips.

Claude, meantime, had returned to his lodgings, and as the

evening wore on he determined to watch for the return of John Bower

to his home. For that purpose he put out his light, the better

to see into the darkness without, and took his seat at the window,

which looked out into the street.

Mrs. Bower, while she waited on him at supper, had told him

the cause of the disturbance, and allowed him to see something of

the desolation of her own heart as well. It was the first

time, since the death of Tom Myatt's mother, that she had unburdened

herself of the sorrow which sat always behind her sad eyes and

patient mouth; and Claude did his best to lead her to the source of

all consolation. She listened in respectful silence, but made

no response until the end, when there came from her lips one bitter

cry of hopeless anguish, and she turned and left him.

It was as if he had witnessed a volcanic eruption, not from a

vast smoking looming mountain, but amid the quiet and peaceful

fields. Up through the dull routine of life had burst the

central fires of human passion, scorching, devastating, choking with

ashes the common ways of life. Were they smouldering all

around and within him? Surely he, of all men, was armed with

the right to quell them—he, the minister of Christ, to whom had been

committed the ministry of reconciliation. Ought he not, in his

Master's name, to cast out these devils, calm this rage, assuage

this terror, annul this hopelessness? If the religion he

taught was a reality, these things it ought to do, and greater

things than these. Yes; there still remained the mighty and

miraculous Witness for the truth, which could accomplish all things

by its sovereign power over the spirits of men; and that power was

at the service of a Christian's prayer.

It was a quarter past eleven by his watch, for he had just

looked at it by a flicker of firelight, when Claude heard a step

coming nearer and nearer in the silent street. He looked out,

but could see no further than the patch of light thrown by the

window beneath, which showed that another watcher waited John

Bower's return. The step was an unsteady and shuffling one,

and Claude jumped to the conclusion that John Bower had been

drinking, and had come home in a state of intoxication.

Presently the figure of a man appeared, swaying to and fro, and then

falling in a heap on the pavement. A door was opened

immediately, and a woman came out and bent over the prostrate

figure. Claude hastened at once to her assistance.

When he reached the pavement he found, not Mrs. Bower, but

Priscilla Jewel, stooping over the senseless form of her father, and

vainly endeavouring to raise him up. Claude already knew the

old man's failing, and was not astonished, but the sight that met

his eyes was one calculated to increase the burden already weighing

on his spirit. The rain was still coming down heavily, and the

old man lay with white hair dabbled in the mire. As the

raindrops dashed into his face he began feebly to wipe them off,

muttering, "Don't ye, don't ye," as if remonstrating a human

persecutor.

"Oh, father!" groaned Priscilla, trying to shield him, and

turning to Claude for help. "I'm ashamed that you should see

him," she said. "He has not been so bad as this for a very

long time."

It took all Claude's strength to lift the old man and get him

upstairs and into his arm-chair by the side of the fire, while his

daughter wiped the rain from his face and the soil from his grey

hair. And no sooner was he sensible of warmth and kindness,

than he began to look round and smile with amiable imbecility.

"He vexes me dreadfully," said his daughter, "but he is

always so gentle. He is not so bad as Mr. Bower."

"I do not know which is the worst," thought Claude, taking

his leave.

And now for the other.

He watched long and patiently, but not long or patiently

enough. In the small hours he stretched himself at length on

the horse-hair sofa and fell fast asleep. He was sleeping

peacefully when John Bower stole into his own house, drenched to the

skin and exhausted to helplessness, and a weary woman stole up to

him and entreated him to eat and drink and go to rest.

The next morning Phillis was at home. Her mother had

got her to return early in the morning, for fear of rousing her

father's anger, and because she herself was suffering. She had

said nothing about it at the time, but she had received a hurt the

night before which had almost disabled her. In throwing her

off from him, her husband had caused her to reel against a small

table which stood in the window crowded with flower-pots, and the

corner of it had struck into her side. She had often received

still rougher usage, but she had never been so badly hurt before.

It had been sharply painful at the time, but the pain did not abate

as she expected. It seemed rather to grow worse and worse.

During the weeks that followed, matters remained on much the

same footing. Mrs. Bower continued to be invalided, without

breathing a word to any one why or where she suffered. John

Bower kept as much as possible out of everybody's way, and muttering

fearful things against himself and the world in general; and Phillis

and her little handmaid waited on Claude in an invisible fashion.

Phillis had been relenting towards her lover ever since she

had cast him off. It was not in her nature to inflict

suffering; and when she thought of his suffering—and her mother was

not slow to tell her of the part she bore in it—she longed to

comfort him. She heard that he was about to leave England for

ever, with a sinking heart. The unknown had always had a

terror for Phillis; and her lover seeking his fortune in strange

lands was a picture that moved her to pity and compunction, unlike

any possible reality as it might be. Compassion in this pure

nature was stronger than love, and to save him from this fate of

banishment, she felt almost inclined to sacrifice herself.

With her mind full of relenting tenderness, she met him one

evening as she was coming out of the chemist's with something her

mother required. He was standing opposite the window, as if

watching for her, and at first she did not recognise him, for he

stood in a stream of blue light transmitted by a huge bottle of that

colour. When she did, he was looking sufficiently sinister

under the ghastly influence. She was the first to hold out her

hand.

"Tom," she murmured, wistfully, stopping before him.

"Oh, Tom, won't you speak to me?"

He took the hand, and held it tight, tighter than was at all

pleasant, and moved with her out of the glare.

"Have you come round to me, Phillis?" he asked. His

voice was not reassuring, and the question was a difficult one to

answer.

"I have never been against you, Tom," was her reply.

"And I am sorry I have vexed you so much."

Had he known the way to her heart, had he been gentle and

tender, acknowledged a misunderstanding, and not unduly pressed his

suit, at that moment young Myatt might have won Phillis for ever;

but he could not. Instead of this, he asked, bluntly—

"What set you against me? Was it that preaching fellow

you have got in the house?" ignoring her last words.

"No," she answered, quietly, her ideas clearing. "It

was not Mr. Carrol, it was yourself, if you will have it. I

saw you all but strike Joe Reynolds one day. You were in a

dreadful rage. I could not bear to see it, and I told you so

at the time. It came into my mind the other day, and I could

not" she hesitated—"I could not live the life my mother has lived."

"I dare say you never saw the curate in a rage," sneered

Myatt. "It's easy work telling people to do things, and then

going away and never minding in the least whether they're done or

no. I have to get things done, and when men won't do them, I

must make them. Blest if I wouldn't like a whip in my hands!

wouldn't I lay it on, too, on Joe and some other fellows I know!

The moment your back's turned they are shirking their work, stealing

your time, which is the same as your money, or stamping and cheating

the public; mean, lying, dirty rascals. And fellows like your

curate, I've heard them stand up and be praise them, and beg of them

not to work so hard, to take time for recreation, and so forth."

"What harm has Mr. Carrol done you, Tom, that you should go

on at him? He is as gentle as a lamb," said Phillis.

"Oh, yes! I have no doubt—with kid gloves on.

Would you like to see me sawing a plank with a pair?"

"But, Tom," she said, "I could fancy things being done so

differently. I can't think that swearing helps, and rough

words and savage looks."

They were at her mother's door. "Won't you come in?"

said Phillis, timidly. "Mother would be glad to see you."

"No, Phillis! I won't come in. I'll never enter

your father's house again, but I'll take you out of it, if you

like."

"My mother is ill, Tom. It cannot be. I could not

leave her, even if I was willing. Can't you be friends with

me?"

"No, I can't."

He turned away abruptly, and the next time he met her he

thrust a letter into her outstretched hand, and spoke not a single

word.

She took the letter home, and read it up in her room, telling

no one of it, and putting it in her purse, which had been Myatt's

gift to her, and constantly reminded her of him.

The letter was a threatening one, telling her that he knew

now for whom she had turned him adrift (who it was, Phillis had not

the wit to guess), that he was watching them, and that some day he

would kill the fellow, though he should swing for it. After

that Phillis seemed to encounter Tom at every turn. He never

spoke to her, but she could do nothing that he did not seem to know.

She began to feel a sickening dread of him. What could he

mean? Was he mad? He had invented what was to her a

supreme torture—the dread of some unknown evil.

Then came Claude's illness, and Mrs. Bower fairly shut

herself up in her lodger's room, just as she would have done with

one of her own children, while Phillis minded the house and waited

upon them "hand and foot," as her mother phrased it.

The kind-hearted girl had indeed laid aside her own trouble

in view of the trouble which had befallen the stranger. She

did not persist any longer in avoiding her father, but waited on him

also, though with inward shrinking, and he, on his part, being

sensible that his lodger's illness had placed matters on an easier

footing for him, was quite ready to accept the fact without a

murmur.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXXVI.

THE TIGER ROUSED.

AND now to come

down to the Saturday before Easter when Claude walked home with

Phillis from church. Few words passed between them as they

walked up the street together. Phillis's words were few at any

time, and she still stood somewhat in awe of her companion, for the

sake of his office. So she kept dropping half a pace behind

him, and he had to turn his head slightly in order to address her.

Once or twice he did so, and she raised her eyes and gave him some

soft monosyllabic answer, letting them fall again half-musingly on

the ground as she spoke.

"It was Myatt."

They were passing the lane just then, and neither noticed the

young man who stood still that he might not cross their path.

It was Myatt, who had come there for the first time for weeks, for

Phillis had lately kept in-doors persistently.

As his eyes fastened on the pair his face flushed, the veins

in the throat swelled to bursting, and he stood clenching teeth and

hands in murderous rage. Seeing these two together thus had

been like oil thrown on a dull fierce fire. In a moment his

passion of smouldering jealousy sprang into a consuming blaze.

As they passed, he turned and strode into the thicket to give

vent to it out of human sight. He was a man who prided himself

upon his manhood, and in this overpowering rage there was for him

deep humiliation. He had often enough put himself in a

passion, told himself that he had a right to be angry; but then he

had been the master, now he was the slave, and he went and literally

bit the dust.

In the interval that had passed since be had last spoken to

Phillis, he had fully made up his mind to quit England. He

could think of nothing harder to do, and he craved for hardship as a

kind of solace. He would tell Phillis of his resolve, and say

good-bye to her for ever. Still across the desolation he

pictured to himself would fall a ray of light. At the last

moment Phillis might relent and go with him, leaving father and

mother, and with her mother's blessing on the deed.

He made all the haste he could, but it was not a thing to be

done in a day. He must wind up his affairs and pay his debts,

and sell the freehold on which cottage and garden and workshop had

stood for generations. In the meantime he could not work, and

he took to hanging about and making himself miserable. He

hated idleness, and he idled. He hated drink and drunkards,

and he took to frequenting public-house bars and tasting what he had

been wont to call their filthy slop. He was not likely to

become a drunkard. His healthily organised but sensitive

system refused to absorb the poison. It made him ill and

intensely irritable, but if he went to the public-house he must

drink, and where else had he to go? His home had become

utterly distasteful to him. He had never before discovered how

solitary and comfortless it was, because he had filled it with her

image. She had sat in his mother's chair by the hearth.

He had seen her moving about in kitchen and parlour and handling all

the household things; for when Mrs. Myatt lay dying, Phillis had

been sent by her mother to wait upon her friend. And

thenceforth to him she had been there always, illumining everything

with her grace and beauty. But now he was bereft of the

vision. It had made the poetry of his life, and with its loss

everything had become sordid and worthless. He had had no idea

of the absorbing strength of his passion, nor had he been able to

give anyone else an idea of it. He had no religion, and but

little love of his fellows. He had kicked not a few of them

for lying and stealing, which were the vices he hated, despising

sensual sins too much to hate them, and looking upon them as a kind

of disease. Home was this man's altar, and the woman he loved

was its deity. He had meant to live for her, and losing her he

had nothing to live for. Nor was he one of the men who when

they have loved one woman, turn easily toward another—love all women

a little for the one's sake. He rather turned away from other

women because of Phillis. The poor widow who had come from the

neighbouring cottage to wait upon him daily since his mother's

death, wondered what she had done to offend him. She could not

understand the change in him. It was in vain she tried to make

things "a little comfortable for him." He seemed to take a

pleasure in being comfortless. He had broken through all his

regular ways, and it began to be whispered that young Myatt was on

the road to ruin.

Mrs. Bower, sitting in the chair which she almost never left

now, shed bitter tears over the news. She had loved the lad as

if he had been her son; he had been so good and upright, so kind to

his mother, so steady and temperate; and it was her daughter's

doing. She fancied her old friend reproaching her from the

other side the grave; so she felt more and more inclined to overlook

the fault of young Myatt's anger—to find in it, indeed, no fault at

all, considering the provocation he had received—and to long for a

reconciliation between the lovers. Her dread of what would

become of Phillis when she was gone had been growing with her

increasing weakness. She greatly underrated her daughter's

strength of character, overlaid as it was by excessive gentleness,

and trembled to leave her in a world so unkind. As she thought

of her future, and remembered the little child who had run to her

bosom if even she saw an evil face, in whom terror and apprehension

had been so easily roused, so wrought into the nature, that her

mother's care had been doubled to guard her from sight or sound of

fear, she could almost have wished her with the other little ones,

whom she pictured to herself in heaven, pillowed among soft white

clouds, like the cherubs in the old family Bible.

And Mrs. Bower was convinced that she had not long to live,

that she "carried her death," as she phrased it, confiding in

Priscilla Jewel.

"Don't tell Phillis yet-awhile, dear," she said; "only

prepare her, like, if you can manage it. I wish she and Tom

could make it up again; but I don't rightly understand Phillis about

him. I don't want to know more than she tells me," she added,

hastily. "Girls often tell one another more than they tell

their mothers; but I think she likes him better than she likes any

one else; and I want you to give him a hint, Prissy, to look after

her when I'm gone. Take this to him," and she produced a

careful little parcel—the earrings she had picked up and kept—"and

tell him what I said, and that at least I would like to say good-bye

to him before I go. He could slip in some Sunday."

Priscilla knew what she meant, and took the parcel, though

her hands trembled as she did it. Her voice trembled, too, as

she promised to meet Myatt, and give the message.

Phillis was in the habit now of summoning Priscilla to sit

with her mother while she went out on necessary household errands,

so that Priscilla had an opportunity of talking to Mrs. Bower, whom

she tried to lead to her own religious standpoint.

"I've had a world of sorrow, Prissy," she answered, quietly,

on one of these occasions, "and I used to seek comfort that way,

especially when my babies died. If I had married a Christian

man, I think I might have been a Christian woman."

"Don't say you're not a Christian, dear Mrs. Bower," said

Priscilla. "You love the Lord Jesus."

"I love to hear about Him; and the world seems a dreary place

to live in when one hears tell that it's all nonsense—that no such

Man ever lived, or that, if He lived, He was only mocking and

deceiving people, or else nothing but a lunatic."

"You don't think that!" said Priscilla, with a long breath of

dismay; "it's too dreadful."

"No, I've never thought John in the right about religion.

It doesn't seem possible for things to fit in as they do if they

came by chance, and if there was some one at the making of them and

us, He would be sure to let us know. And, if we were not meant

to be better, it wasn't worth while making things as they are.

It all hangs together, I can't explain how."

"I could never rightly understand either," said Priscilla,

"till I saw for myself, and now I don't want any explanation.

I don't mean that I haven't a great deal to learn. But it's

like being able to read. You can get to know anything there is

in books if you can read—and you can get to know anything in

religion if you know the Lord."

Mrs. Bower shook her head; the vision was denied her.

Phillis and Priscilla were outwardly as great friends as

ever; but it had come to pass that each had thoughts and feelings

the other did not share, and, this being so, they were divided in

spirit as they had never been before.

A change had come over both. Phillis's singing was

silenced as she moved about the house. Her heart was heavy,

and not for her mother only. She had loved more than she knew,

and was longing for reconciliation with her lover, and between them

she had placed the dreadful barrier of her father's mad rage.

As for Priscilla, who had ever moved about her household

tasks quiet as a ghost, she had broken out into joy and singing.

She had had no one to speak to when her father was at work till she

could finish her own and hasten to Phillis, or Phillis to her.

But now there was a presence with her always, and she would pause in

the midst of the humblest occupation to pour out some fervent prayer

to the Saviour.

But it was when left alone in the long evenings, with her

father away besotting himself at the alehouse, that her whole life

became absorbed in devotion. Then, if the world had gone

crashing to its doom of fire, this simple girl would have been found

tranced in the worship of everlasting love. And it laid on her

the necessity of love to communicate its fervour. If others

could see as she saw, and feel as she felt, they, too, would be

saved. At first she only prayed for her father, then she spoke

to him, moving him to tears of penitence, which disappointed her

hopes again and again.

"Come for me, Prissy, come downstairs for me, and keep me in

the house," he said at length. "I want to stay at home.

I'm getting an old man now, and I feel it will be the death of me.

I don't want to go and drink, but it's just as if someone else was

drawing me and I can't resist."

Even after this the besotted man went the old way, and

escaped from the forge to the ale-house before the appointed hour;

but Priscilla, growing bolder, followed after, and more than once

she had succeeded in rescuing him from what, to her—coming from her

pure and silent heaven of thought into the reeking noise and

ribaldry and strife—was a place of horror indeed.

Young Myatt strode off into the thicket wild with jealousy.

It was for this man, then, that Phillis had cast him off.

Walking by his side with downcast eyes, she had not so much as seen

him. Mentally he raved, raved at Claude, and his calling, and

his creed, with the utter irrelevance of insanity. Up and down

the little wood walk, that witnessed Claude's weekly meditations, he

paced like a caged tiger. In the gathering darkness the naked

boughs crossed each other like an iron network. His red lip

snarled, and showed his white teeth, as he muttered curses on

himself, and life, and all things. At length, flinging himself

on the earth, he expended his passion in a prolonged brute-like cry,

which he stifled by biting the root of a tree which showed above the

earth.

Shame checked the outburst, and followed it. He could

have sat down and wept like a child at his mother's knee, but there

was none to comfort him, either in heaven or earth. He was

exhausted, but the torture was still within. Could he have

rushed away there and then, he might have quenched it; but he could

not command modern appliances, any more than he could the elements.

The former were, indeed, the more inexorable, inasmuch as he could

not defy them. If a ship will not sail until a certain date,

you cannot go in spite of it. Should he stay, then, and avenge

himself on Phillis and her lover; watch, threaten, thwart them, at

least as far as their hopes of each other were concerned? It

was an idea and a purpose, and so it calmed him, restored him to

comparative sanity.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXXVII.

FLAWED.

ERNEST has been

staying with Mr. Temple and his uncle for the last few days.

It was Easter Eve before he arrived at Highwood. He was at

home when I returned from the Rectory from passing an hour with

Linnet and her mother.

Lizzie was making tea in the drawing room for him and Aunt

Monica when I got in, and I heard him saying, "Temple goes down to

Bournemouth to-day. You will hardly guess with whom."

Of course it was impossible to guess, but, as he rose to meet

me, Ernest's face had a troubled look, as if there was something

behind the words he had tried to say so lightly.

"He has gone to look after Edwin," he added, after a

momentary pause.

"To look after Edwin?" I repeated.

"He has got a holiday," was Lizzie's remark.

"He is ill," was mine.

"Yes, he is ill," said Ernest.

"He never told us," said Lizzie. "How long have you

known?"

"I never knew till Temple told me" he replied, very gently,

"and that was only the other day."

"And you have not seen him!" said Lizzie, reproachfully.

"Yes, I have seen him," he answered, sadly.

"Oh, I am so glad!" cried Lizzie. "And he is not very ill, is he?"

"I fear he is, Liz."

"How did Mr. Temple know?" said Aunt Monica.

"He met Edwin in the City one day, and went home with him," said

Ernest. "Edwin was looking very ill—said the doctor had recommended

him to take a holiday; had, in fact, told him that he must have

rest. Temple offered to go down to Bournemouth with him for a

fortnight."

"It ought not to be left to Mr. Temple," I said. "Could you not have

gone instead?"

"I would have gone," said Ernest, humbly, "but, I believe it is

better as it is. If I had gone, his wife would have insisted on

going also; and there would have been no peace for him. Besides, he

is better with Temple than with me," he added, looking at Aunt

Monica. "He sends his love to all of you."

"Do you know what is the matter?" I asked.

"He has not been well all the winter," said Ernest. "The doctor says

he should have been consulted sooner; it is disease of the lungs."

We were all silent for a few minutes. Ernest was evidently suffering

the keenest compunction, and we shared in it more or less. We had

let him drift apart from us without a struggle, it seemed, and now,

perhaps we were going to lose him for ever.

"Oh! Aunt Mona, we must go to him," cried Lizzie, as if it was a

thing we could accomplish within the hour.

I was silent, but my heart was crying out after him likewise. It

seemed hard not to be able to be with him.

"Temple is to write. He will write to us daily," said Ernest; "and

he may get better down there. The summer is coming, and there is

nothing to hinder his recovery as yet."

Our Easter Sunday was saddened by this news and on Monday, in spite

of the crowded state of the trains, Aunt Monica and Lizzie set off

to London to see Doretta and the children.

I had Ernest all to myself, and he broke silence with regard to

Edith. He has, it seems, seen a good deal of her in London, and

wishes to have the engagement between them recognised, even if they

must wait for a year or two. He would have made it public before,

only Edith would not have it.

"I can quite understand it," I said. "And even now, I think if you

must wait so long it would be better not to make your engagement

public."

"Why do you think so?" he asked.

"Oh, only because of the former engagement, you know," I answered,

wondering that he should ask me to give a reason when there was one

so obvious.

"I don't see what that has to do with it," he replied. "The

gentleman is dead—was dead, you know, before Edith and I came

together again. Of course, there is his family, but they can't

desire any consideration of that kind. By the way," he added, as I

listened, astonished and aghast, "was it any of the people about

here to whom Edith was engaged?"

Was it possible, then, that he did not know?

"What is the matter, Una?" he said, quickly. "You look completely

flabbergasted—just as you used to look when I had made you open your

mouth and shut your eyes, and experimented on your trustfulness by

giving you a taste of something not too agreeable. You know you

never could be got to believe that anybody wanted to do anything

disagreeable."

It was only too true—oh, so terribly appropriate to the present,

that I wrung my hands, and, I have no doubt, looked, as I felt, in

utter despair.

"What has happened?" he went on, laughingly. "You are growing

tragic."

"Oh, nothing—only I made sure you knew."

"Knew! What in the name of wonder is there to know?"

"That Edith was engaged to our Uncle Henry."

It was a shock, and he staggered under it.

"And why was I not told? " he asked, coldly. "I think it was you

who told me of the—thing itself—why did you not tell me this?"

"Simply because it was so intensely disagreeable," I answered. "I

shrank from writing of it, and afterwards I made sure you must

know; I did not think it was possible for you to be with Aunt Robert

and not hear of it."

"A nice thing to know—so intensely disagreeable that you all shrank

from speaking of it; and she, too—she has never made the most

distant allusion to it."

"Oh, Ernest! you must not blame her," I cried. "She could not have

spoken of it. She could never have thought that it was unknown to

you. She must have believed that you were silent from motives of

delicacy. Besides, she herself hated and loathed the whole affair. See how ill it made her. I do believe it would have killed her."

There was no relenting in his face. A stony sneer had taken

possession of it.

How bitterly I blamed myself for this fault of mine, this shutting

my eyes to things ugly or painful, as if ignoring their existence

would cause them to cease to exist. It is not that I wanted to hide

the truth from myself or others, so much as that I wanted to cover

it, as dead things are covered and buried. To me it seemed almost

sacrilege to listen, to look when unlovely things were said or done.

In my dislike I forgot that in order to be covered and buried, the

things that hurt and offend must first be brought to light and

handled, however reverently.

"Of course, every one but me knows all about this precious

engagement," he said, at length. Then, after walking up and down the

room for a few minutes, he burst into a mocking laugh.

"Oh, Ernest," I could not help exclaiming; "you hurt me so by laughing

in that way; I would rather see you cry."

"Life is such a farce," he said. "Was there ever such an

incongruity? I hate the whole thing! I wonder," he went on,

standing still before me, and speaking contemplatively, "I wonder

if the governor would let me change my mind about this law business?

I should like to get away—to go in for a sword instead of a gown. I

shouldn't mind a bullet through me, to let in the daylight; you

know, Una, I never could bear anything that was flawed or damaged. Don't you remember what an insane desire I used to have to break and

utterly destroy anything of mine that got injured in any way? No

matter of what value the thing was, or how much I had cared for it,

I never cared for it again. I feel like that about her!" he ended,

in a hoarse whisper.

"Oh, Ernest! you are cruel! What a terrible thing to say!"

"It would be if I said it to her, but I won't. I can't break with

her now. I must bear it in silence, I suppose."

"It is a cruelty even to think it," I said, indignantly. "People

are not like things—like china that will only mend with a crack—or,

at least, they are only like things that live and grow. A blossom or

a fruit may perish without any hurt to the tree, the blossom and

fruit of a whole season may perish, and yet the tree may live, and

grow stronger and more beautiful the next."

"You are the poet of the family," he said, half mocking, half

tender. "I am going out for a little. Good-bye for the present." And, nodding carelessly, he left the room.

My father and I lunched alone that day, as Ernest did not make his

appearance; and after luncheon I went and sat in one of the

drawing-room windows by myself, full of the saddest thoughts. I do

not know how long had been there, idly brooding, when I heard the

clatter of hoofs. Through the trees I could see that the rider was a

lady, but before I could really distinguish who it was, I felt that

it was Edith, and very soon I saw her dismounting at the door.

My heart almost failed me, for I realised the task that lay before

me; but I hurried out into the hall to meet her.

"Ernest told me you would be alone to-day, and I came over early to

catch you before you went out," she cried, throwing down her hat and

whip, and kissing me.

We went into the drawing-room together. Edith had not released me. She kept her arm half round me, and I fear I shrank a little; not

from her—it was the consciousness of the task before me from which I

shrank, for I meant to tell her what had taken place between Ernest

and me.

She looked hurt at what she thought was my coldness.

"You know about Ernest," she said, looking into my face. "Do you

dislike having me for a sister? Perhaps it is natural," she went on,

rapidly; "but if he does not mind the past, you ought not, Una. And, oh! I mean to be so good." She held both my hands in hers, and

her beautiful eyes were fixed pleadingly on mine, filled with the

steady light of devoted affection.

Clasping her in my arms, I burst into tears.

"Dear," she murmured, caressing me, "I am so glad you will love me! Now I know you will. And you will help me, you and Aunt Monica. I

want to help him to live the higher life he craves for, not to

hinder him. And, indeed, dear, I never cared for a life of pleasure.

Only one gets dragged into it; and once dragged into it, the machine

goes round with you, whether you will or no."

With her arm still round me, we sat down together; but I was no

longer passive to her tenderness, I returned it with all my heart.

"You have not seen Ernest to-day, then?" I said. "No," she answered. "Last night he told me to come to you, to see you alone."

"I must not withhold the truth any longer. Do you know, Edith," I

said, "that Ernest did not know about—about your engagement till

to-day?"

"Not know, dear! What do you mean? He has known all along."

"Not who it was. I have only now told him."

A frightened look came into her eyes.

"I never doubted that he knew all," she said.

"I am sure of that," I answered. "And it is all my fault." I could

not say that I shrank from telling him.

"But how was it that he did not know?" she persisted. "Ah, I need

not ask," she added. "You are not blushing for yourself, Una. It was

too disgraceful."

"I thought Aunt Robert would certainly tell him," I said. "But I

blame myself acutely."

"You are blameless enough," she answered, sorrowfully. "Did he

condemn me? Is he disgusted, angry?"

"He is not angry."

"But he is disgusted," she replied, quickly. "And now I know what

that means with him, Una, there is only one thing for me to do, and

that is to give him up."

"He will not give you up," I said.

"Has he said so?" she asked, looking bright and hopeful for a

moment.

I answered, "Yes."

"Ah! but I know it is not for love's sake, only for honour, because

he will see that I had no wish to conceal it, and that he has only

been deceived by accident. I know exactly what he will think and

feel, and how he will act; but, if he had known, he would never

have renewed his friendship for me—would never have loved me—and oh!

Una, it must all be as if it had never been."

"Do not say that, dear," I exclaimed. "He must sympathise with your

distress. It is no fault o£ yours that he did not know."

"No, Una; I love him too well to keep him to his engagement, feeling

sure, as I do, that this has revolted him. I have a complete

conviction that it is so. I wondered at his generosity and

goodness—thought it more than human in him, with his fastidious

notions. I do not wonder at his disgust. I am going home," and she

rose from her seat beside me, "and I will write to him at once. It

will pass for one of my flirtations; mamma will be a little harder

on me than usual, and I will fall into the old round."

"Not that, Edith!" I cried, clinging to her.

"I wonder what I shall do with myself then," she said, with her old

mocking look, only more gentle and spiritual. "I wish I might have

been left behind in Italy, beside the sea. It would all have been

over and done with, then."

"But you do not believe it would all have been over and done with,"

I said gravely. "There is the life everlasting,' which you repeat

every Sunday."

She looked at me questioningly, and answered, "Of course we believe

in that!"

"But it isn't 'of course,' Edith. It has never been 'of course' to

me, you know, and I could not say it if I did not truly believe it.

I heard you say the words last Sunday."

"Don't you say them?" she asked, curiously.

"Yes, these words I say, and some others, as I learn to believe

them; but if we say them and believe them, then there is something

quite other to live for than the world, even the world's best."

"You are more and more like Aunt Monica," she said. "Una, if he

does not want to see me again, will you send her to me?"

"Aunt Monica?"

"Yes. Good-bye, dear."

I watched her from the window, with tears in my eyes, as she rode

rapidly away.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

FADING LIGHT.

EDITH went home

and wrote her letter. Ernest had it the next morning. I

knew by the air of studied unconcern with which he opened it and

only scanned its contents, reserving it till he could read it by

himself. I will not speak to him on the subject. I hope

everything from Edith's action, and will leave it to work. She

has done just what I would have done in her place.

There was also a note from Mr. Temple, which Ernest passed

round the table in answer to our entreating looks. It was very

brief and anxious. Edwin was rather worse.

"I think I ought to go down to him," said Ernest, when papa

read the note and had handed it me.

"By all means go," said our father; adding, after a pause, "I

think I shall go with you."

We are all so thankful; now there will be no more

estrangement among us. We must not let Doretta separate us

again.

Ernest has sent a telegram to Mr. Temple, to say that papa

and he are coming down immediately.

He has also written to Edith. I saw the note lying with

others in the hall, but concerning its contents he has not spoken.

Edith came to tell us what Ernest had written in answer to

her proposal. He does not give her up. He says he cannot

allow her to suffer, if indeed it would involve her in suffering.

"I did not try to make him think it would not. In spite

of pride I could not do that," she said; "but I ought not to accept

anything so coldly offered. And that doubt of his—as if he

could not believe me capable of disinterested affection! I

shall not write again," she concluded, "lest I should be tempted to

sin against the truth. At any rate, he shall not think more

meanly of me."

I never saw any one so changed as Edith, so devoid of false

pride, so anxious to do right, so unselfish in her suffering.

The Easter holidays are rapidly passing away; Ernest is still at

Bournemouth, and his accounts of Edwin are anything but reassuring.

Of himself he says nothing.

I am a great deal at the Rectory with Linnet and her mother;

they both welcome me only too eagerly. Linnet is still

labouring under her mother's chill displeasure, and it seems as if

the estrangement must go on increasing rather than diminishing.

Neither of them has the key to the other's nature; and in a

relationship so close and dear, the mere want of sympathy must be

sufficient for the production of misunderstanding. With Linnet

the inability to comprehend her mother's character arises from her

youth and inexperience. On the part of Mrs. Lloyd it is deeper

seated; still, both are suffering, and each carries in her heart a

sense of outrage and humiliation.

It is not every one that could tell that Linnet is suffering.

There are no traces of tears on her face, but the brightness has

vanished from it; the smile has gone out of her eyes, and the gay

tones out of her voice. Her mother thinks her sullen, as she

sits by her side working her pretty embroideries, while she longs to

jump up and run out, even in the drenching rain. She would

like to take lonely walks, but dare not propose them. Her

father still comes to the rescue, and takes her out with him, but he

has become sadly preoccupied. He has had very bad accounts of

his son. The doctor who has been attending him—an old friend

of the family—has written to him in a tone of warning not to be

mistaken; and now they are expecting him home every day.

I was sitting with Linnet and her mother the other day, when

Mr. Benholme was announced. He came in saying that a slight

accident had happened, and he had been obliged to send the carriage

to the smith's. After a little chat and the serving of

afternoon tea, at which Mr. Lloyd appeared, Mr. Benholme asked the

latter if he could spare time to walk over to Highwood with him.

Mr. Lloyd explained that he was waiting for the carriage to

go to the station to meet Charles.

"There are two young ladies, who will be all the better for a

walk," he suggested.

We both expressed our willingness to go, and Mr. Benholme

thanked us and accepted.

"I think I must bow to fate," he added, "and find some one to

lead me about and read to me."