|

FANNY'S FORTUNE

BY ISA CRAIG-KNOX, AUTHOR OF "ESTHER WEST," "TWO

YEARS," ETC. ETC.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

PHILIP.

"At forty man suspects himself a fool," says Young, the sententious. Philip Tenterden suspected it a little earlier, it seemed, for he

muttered the objectionable word, evidently casting it in his own

teeth, as he passed the mirror on the mantelshelf, and greeted his

gloomy reflection there. Then he flung himself into the nearest

chair, and from thence surveyed the immediate prospect with

determined resignation.

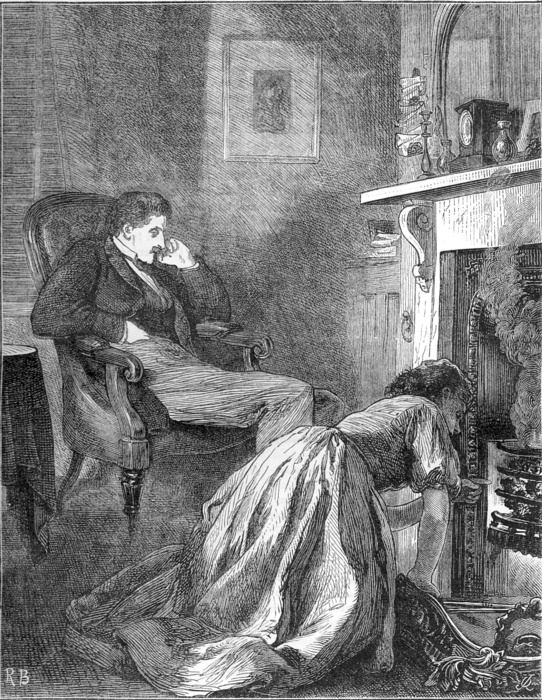

It certainly was not an inviting one. A newly-kindled fire sputtered

in the grate, and the room, already full of November fog, was fast

filling with the acrid smoke of burning wood. "Fool!" muttered

Philip; but for what?—for living the life of a bachelor in London

lodgings, or for feeling desperately depressed and miserable on that

particular occasion, when there was nothing more than usual in the

circumstances, except that the fire refused to burn up and the not

very neat-handed Phillis, Mary, had re-lit it so awkwardly that half

of the smoke found its way into the room instead of up the chimney. She had also disappeared, leaving behind her a stalactite-looking

candle, the light of which made fog and smoke and darkness visible.

Presently, however, the damsel reappeared, carrying a regulator

lamp—a very ill-regulated lamp it was, for Mary generally contrived

to make it smoke and smell abominably at some period of the evening,

besides which, it showed itself capable of a variety of caprices

quite incomprehensible to the ordinary intelligence. On the present

occasion it simply went out as soon as it was set upon the table,

and Mary—who, by the aid of a vivid imagination, could always

account for its vagaries—stated apologetically that it had had too

much "ile," adding privately what sounded very much like "drat it,"

as she lifted the glass globe and chimney, and applied a lighted

match to the wick. When she had set the lamp agoing, she went down

upon her knees and poked the fire with her fingers, and blew it with

her breath. And not a word of remonstrance fell from the lips of the

figure in the chair—not a word, for he knew that the slightest

murmur would bring down upon him a shower of fibs.

(Drawn by ROBERT

BARNES)

"Not a word of remonstrance fell from the lips of the

figure in the chair."

Mary was an Irish girl, clean and active and clever enough, but

awkward at little things, as if her fingers had an inherited

incapacity for dealing with them, an incapacity which extended to

her tongue with regard to facts big and little. Several times

in his despair Philip had summoned the landlady, but on her appearance

his accusations had assumed the mildest form—indeed, they had

sounded to the poor woman, unused to so much courtesy, like

commendation itself. She laboured under a distressing

breathlessness, which made her eyes brighten and dilate, and which

gave her, as she leaned heavily against the table with one hand, and

held the other before her lips in a deprecating manner, the look of

a creature hunted and at bay. Philip was glad to see as little of

her as possible.

Mary, having coaxed, the fire into burning, proceeded with the

ordinary routine of the evening. She covered one half of the table

with a cloth—a plan which strictly defined the isolation of the meal-maker—and set thereon the materials for a nondescript meal—tea,

and a mutton chop. Philip Tenterden had given up dining. In this

fashion he breakfasted and in this fashion he supped, eating besides

a comfortless midday meal in a city dining- room.

He ate his chop and drank his tea slowly and in silence. It seemed

indeed a very silent house, in one of those "no thoroughfare"

roads, where the grass grows along the edges of the pavement and by

the sides of the railings. When the things had been removed, he went

to a side-table and took up a book, one he had taken from a

lending-library, and sat reading for a time. At length he threw it

down in disgust—it might have been with his own mood, but the

unfortunate author came in for a share of it. He wished that he had

brought work with him—a thing which he often did—but as he had not,

he tossed back his hair from his forehead and sat resolutely looking

into the fire, daring to do nothing. Yes, daring! for it was not a

pleasant airy daydream that came to take possession of the mind of

Philip Tenterden; it was a troop of dark, sad, bitter, perhaps

well-nigh maddening thoughts, to which, with a scornful smile

lengthening his long, close lips, he said, "Come on."

Philip Tenterden is dark, but certainly not strikingly handsome, he

is too long-nosed and lantern-jawed for that; but he has a fine

graceful head and beautiful eyes. The lines of his face are neither

weak nor sensual. A man who would enjoy keenly and suffer keenly;

he sees and fights with the shadows about him, pursues them,

entreats them, and does not succeed in dispelling them with the

light of common day, or its artificial substitutes, as most of us

do. And distrust has come to be the attitude of his soul; perhaps

his profession fosters it, for he is junior partner in a firm of

City solicitors, Messrs. Austin, Tabor, and Tenterden, and he sees a

good deal of naked human nature on one side or the other. And he

never gives over suffering because of this: every new instance of

falsehood, treachery, overreaching, and wrong which comes before him

gives him a new pang. He would fain reverence humanity, and to him

its wholesale insincerities and degradations are continually

revealed in their darkest colours. Once on a time, with a youthful

passion of pity, he had gone down among the poor—the outcast poor of

London—and he had found himself floundering in a perfect quagmire of

imposture and deceit. "Charity is an impossibility," he had said to

himself, turning back into the beaten tracks of respectability, and

adding, "all men are liars."

But was there no insincerity in Philip Tenterden's own life? It

seemed to some who knew him that there must be, for his conduct and

principles were not always reconcilable, at least from without. He

was rich—that is to say, rich for his position, having an income of

nearly £1,000 a year, and yet he was not liberal—in fact, never gave

at all toward any purpose, however laudable, even when he had been

betrayed into speaking of it with enthusiasm. Was he a miser? It

seemed so to some who knew that he lived in humdrum lodgings at a

guinea a week, dressed with extreme plainness, and never entered a

place of amusement. "Why do you live in that out-of-the-way place, Tenterden?'' said his senior, Mr. Tabor. "I wish you would come up

beside us again and be a little more accessible."

But Philip Tenterden shook his head and said he had got accustomed

to his solitude and had given up going out in the evening.

It was strange, so many things men think good were open to him;

society, local public business, the claims of which he had been

wont to advocate and from which he had hurriedly withdrawn, and

last (not least) marriage. And he had nothing to say to any of them.

"Depend upon it there is a lady in the case," said Mrs. Tabor in

confidence to her husband.

"I thought at one time," said Mr. Tabor, speaking with his usual

deliberation, as if he always weighed his words, which was the

case—"I thought at one time he was getting fond of our little Lucy."

"You discouraged him rather, I think," said his wife, with the

slightest ring of dissatisfaction in her tone. Philip had always

been an immense favourite of Mrs. Tabor's.

"I don't know that I did particularly," said Mr. Tabor. "There was

no advance on his part enough to be dealt with in a discouraging

manner, and Lucy was but a child. You know it is two years nearly

since he left the neighbourhood, and we have seen little enough of

him since then. Lucy is only nineteen, and we don't want to lose the

little one yet, do we?"

"No," replied Mrs. Tabor, warmly; "but there's nobody I would like

so much to see her marry as Philip."

Mrs. Tabor was anything but deliberate—a rash, warm-hearted woman.

Not that her husband's deliberateness was the result of want of

heart. On the contrary, Mr. Tabor was kind and liberal; it was the

result of an overwhelming conscientiousness acting upon a naturally

slow and cautious temperament.

"I did not know you had gone so far as that," remarked her husband,

rather wistfully; "at least in serious intention."

"I don't know about serious intention," she answered, laughing. "He

was fond of her when she was ten years old, and he was twenty. They

were the best of friends up to two years ago, and I think she misses

him."

"Has she said anything to make you think so?" said Mr. Tabor,

anxiously.

"No, she says nothing—a far worse sign in a girl like Lucy."

"Well, you know best, mamma," he answered, smiling tenderly; "but I

think the child does not look unhappy."

"Oh! thank God, no," said the mother, earnestly. These two had known

sorrow in their youth, and their one desire was to shield their

daughter from it, though indeed it had not been bad for either of

them; it had not been to either of them the sorrow that worketh

death. Not death to the body, it seldom does that; but to the soul,

with its hopes and loves and aspirations. They had laid their

trouble clean away out of sight and hearing, and made their little

world as bright and gay as they could make it for their laughing,

dancing child.

"That is well," said Mr. Tabor, "for of late I have noticed some

things I do not quite approve of in Philip."

"Indeed!" said Mrs. Tabor. "He used to be the best young man you

ever had in the office; before be was taken into partnership you had

the highest opinion of his business abilities."

"And so I have still," replied her husband; "he transacts every

piece of business entrusted to him with ability and zeal, throws his

whole heart and soul into it. It is not that. I have noticed a

certain graspingness, which is unnatural in youth, and a

parsimoniousness which is unfitting and unnecessary. I would not

like to give our little one into the keeping of a miserly man. I

like a liberal spirit, even if it errs on the side of liberality."

And Mrs. Tabor once more jumped to her own conclusion, and repeated,

"Depend upon it he is going to get married, and is saving up for

it. You can have nothing to say against that, my dear."

CHAPTER II.

MEMORIES.

PHILIP

TENTERDEN'S mode of living did not allow of much variety of

occupation. When he had looked for some time into the fire, he went

and looked out at the window, to see whether there remained for him

the possibility of the only alternative to his lonely sitting, a

long lonely walk. At first, of course, he saw the reflection of the

room, with its lamp and fire blurred with fog. But he got behind the

venetian, and as he watched the street lamp glimmer feebly on the

opposite side of the road he decided that the night was not very

bad, and that he might venture out. He heard just then the eight

o'clock post enter the road. Rat-tat after rat-tat sounded nearer

and nearer, but awoke no expectation in his mind. He had no letters

that did not go to the City. So he neither stirred nor changed his

attitude, even when the postman knocked at his own door. He was

standing there when Mary entered with two notes on a little black

tray. He advanced to take them, and noted a mark on each,

suspiciously like that called "Peter's thumb," but he saw nothing

more till the girl had withdrawn. Then he looked at the letters, and

as he did so a smile dawned on his face, making it tenderer and more

beautiful than one might have fancied. The letter held uppermost,

the letter smiled upon so tenderly, was addressed in a pretty hand

he knew. He opened it, and it was written in the same, but not in

the writer's name. It was a formal invitation to a party on the 28th

of the month, purporting to come from the writer's mamma. It was

quite extraordinary the amount of attention those four and a half

lines seemed to require. He knitted his brows and bit his lips over

them, took several turns up and down, stood irresolute, sat down and

got up again, and appeared as if he could not dismiss them.

At length he sat down once more, wrote an acceptance, which was

informal, and ran:—

"DEAR MRS. TABOR,—Though I have given up party going for some time,

I mean to allow myself the pleasure of being present on the

28th.—Yours, always sincerely

"PHILIP TENTERDEN."

But when he had so written he laid the note aside, as if quite

uncertain whether he should send it or no, while his face relapsed

into the deepest gloom. He took up the other with a look of supreme

disgust. It was addressed in a particularly scrawling hand, and

written in the same; but it had also the merit of being brief. It

ran:—

"DEAR PHIL,—I want to see you immediately about something that has

happened. Please come to-night if you can.—Yours affectionately,

"FANNY LOVEJOY."

Over this Philip hesitated not at all. He determined at once to

answer the summons, perhaps for the very reason that it would

dispose of a disagreeable duty, though he had a certain relish for

such, and in five minutes more he was abroad.

He caught a train at the suburban station, about ten minutes' walk

from his lodgings, and by dint of expertness reached the other side

of London in little more than an hour. Having arrived at the

outskirts—that is to say, the last row of buildings that had

infringed on the open fields—he had also arrived at his destination;

but for full five minutes he paused, looking up at the closely

shuttered and curtained windows before him, through which not even a

ray of light escaped to cheer him, with tidings of warmth and light

within.

The row consisted of a block of three villas, distinguished—or

rather quite the reverse of distinguished—by the title of "Park

Villas," looking out on the pleasant fields which stretch upwards to

Hampstead Heath. They had been built and inhabited by families

connected together by the ties of business and friendship, who had

migrated thither in a body from the neighbourhood of Finsbury

Square.

Mr. Austin, who took possession of No. 1, was the head of the firm

of Austin and Tabor, solicitors. He was at that time a bachelor. His

partner, Mr. Tabor, brought with him a wife and daughter, a little

maid of some nine summers, to No. 2; while Mr. Tenterden, Philip's

father, who was an old friend of both partners, occupied No. 3, with

his sons Francis and Philip, and his orphan ward, Fanny Lovejoy.

As Philip glanced up at the houses the thought in his mind was not

of the changes wrought within and around them by the tide of human

vicissitude; it was of sunny slips of garden on Sabbath afternoons,

when he sat upon the wall, a long-limbed lad, and teased and petted

and pelted with flowers a laughing girl, whose every secret he knew,

whose every happiness he shared. Winters must have alternated with

summer even in that favoured locality, but they were blotted out

of remembrance, only the "sunny memories" lived and clung about the

home of Philip's youth.

At length he knocked at No. 3. A great brass plate was on the door

bearing upon it the name of Lovejoy, a fancy of Fanny's when she

came to live there all by herself. A tidy housemaid admitted him,

rather astonished at his late appearance; but looking a welcome when

she saw who it was, and ushering him at once into the presence of

her mistress.

Fanny rose with an exclamation of pleasure and advanced to meet him,

took his hand in her plump fingers and led him to a chair, while a

big light-coloured cat caught the ball from which she had been

knitting, and played with it, lazily lying on his side on the

hearth-rug.

"It was very kind of you to come to-night, very; but I hardly

expected you. Indeed, there was no hurry. I didn't say there was,

did I, Phil? I forget exactly what I said."

"What has happened?" he asked, releasing his hand. "I see Puck is

all right," looking down at the cat. "Has one of the servants been

robbing you? or is it a case of virtue in distress you want to see

me about?"

"Oh, dear, no—that is, yes. The servants are the best creatures in

the world. Thank you."

This last was for the return of the ball, which Philip had picked

up, and disentangled from the feet of the stool, just as Miss

Lovejoy had upset a basketful of diamond-shaped patches of knitting

in search of it.

"Thank you," she repeated, as he picked up the pieces. "This is the

fifty-fourth diamond of my fourth quilt. I can't see now to read at

night; and I like to sit and think."

"That's more than I do," said Philip. "Your thoughts must be

pleasant ones."

"Oh yes," she answered, with a little laugh. "I was thinking before

you came in how many people I have known, all dead now. There was

father and mother and the little ones, you know, before I came to

live with you. Then there was Uncle Joshua and your father and

mother, and Dr. Darle and his wife, and our old neighbours the

Finches, and the Rev. Mr. What-was-his-name, the young curate, who

went to Torquay with his sister."

"Quite enough! Fanny, stop," exclaimed Philip, when she had got so

far; "I can't bear that sort of thing, you know."

Fanny was accustomed to Philip's impatience with her speeches, and

she placidly paused in her cheerful enumeration.

For the first time in his life, and he had known her as long as he

could remember, Philip felt a movement of pathetic interest in Fanny

Lovejoy, sitting there with that group of old familiar faces looking

at her out of the shadows and peopling her solitude.

It was greater than his own, and growing greater as she advanced on

her journey, and one after another old friends dropped off. She was

at the age, too, when all the ties of later life are forming; when

the little ones are growing up who will lend us their arms to lean

upon when our steps begin to be feeble, who will close our eyes in

the last darkness, and lean over the verge of our graves; but she

had no link to the new generation and no attraction for the old; no

light nor heat of intellect or energy to draw a little circle round

her out of the advancing darkness.

Fanny had been the oldest daughter in a sickly family, a family in

which disease and death had been ever present in their saddest

forms. Neither, it might be, had this man sinned, nor his father;

but sin there must have been somewhere against those laws written on

the tissues of flesh as clearly as on tables of stone, to have

introduced those fearful visitations of malformation, sickliness,

and idiotcy which had afflicted the Lovejoy family. The unhappy

parents, struggling with their own infirmities, had laid down child

after child, with aching hearts, acknowledging that it was better

so; that death was better than the life which they had transmitted;

and in the midst of all this Fanny lived and throve and grew fat and

merry, an altogether inconsequent little person, never considered

very wise, though her only unwisdom lay in her immense

imperturbability, and in her being fat when it was expected that she

should be lean, and cheerful when all around her were depressed. Good nature was scrawled in every lineament of her fat face, a good

nature which had been set down to stupidity, an opinion justified by

a curious incoherence and inconsequence of speech, qualities which

did not come out in act or deed. She was not, as a girl, either

ill-formed or ugly; but she was unusually fat, and persistently

untidy. Her strings were always untied and her buttons unfastened,

and she lost things endlessly. And now, before middle age, she was

left entirely alone, and entirely independent, a woman who trusted

everybody who came near her. She was bound to do something foolish,

in the opinion of the one or two people who had any interest in her

still, and they watched accordingly; but her confiding trust had

hitherto been completely justified.

A friendless orphan at seventeen, she had been left to the care of

Philip's father, who was her sole guardian; and for fifteen years of

her life she had remained in his house as a daughter. She had three

hundred a year at her own disposal; and, after paying a hundred and

fifty for her board and that of the servant who waited on her, she

spent the remainder in her own slipshod fashion, giving away a large

proportion of it in easy charity. But she had been very free and

very happy in the Tenterden household, having apparently no ambition

and no desires beyond it.

Five years after the removal to Park Villas, Mrs. Tenterden died, a

quiet, colourless woman—perhaps because her lot was quiet and

colourless—but one who ruled her house like an embodied equity. Mr.

Tenterden, a singularly reserved man, exhibited a strange mixture of

sorrow and of what appeared relief from restraint when she died. His

sons believed that he acted under excitement, for he was

demonstrative where he had been hitherto shy, and voluble where he

had been silent. Philip, the youngest son, had remained under his

father's roof. Articled at seventeen to Messrs. Austin and Tabor, he

had remained after his five years' probation on the footing of a

future partner, an honour which he obtained after other five years

of servitude.

Francis, the eldest son, was settled in the North of England as an

engineer.

The long-established routine of the widower's household went on as

before, under the guidance of Fanny Lovejoy; but Mr. Tenterden

himself was failing rapidly, becoming a tremulous, sleepless, sickly

man. One day he astonished Philip by saying that he would be glad to

see him settled in life before he gave up entirely.

"I am not an unsettled character," Philip had said, with truth; "and

I have no immediate wish to marry, if that is what you mean."

Philip laid stress on the word "immediate." He did wish to marry

some time, of course. Then what was he waiting for? Was it for the

lady? Her he had chosen long ago, and she had kept the door of his

heart against all comers; but only the other day his little Lucy had

been a child, and he had held back from wooing her with scrupulous

delicacy, for younger and tenderer than she seemed either to father

or mother, she seemed to him.

Imagine Philip's feelings, therefore, when his father said, with a

ghastly attempt to appear jocular, and an ill-concealed anxiety

beneath the surface, "You and Fanny might make a match of it."

"What can have put such an idea into your head?" replied the

indignant Philip; "an imbecile old woman!" Fanny was not so many

years older than himself.

The joke was never repeated in the face of Philip's unmitigated

amazement and disgust; but many a time did the young man look at the

unconscious Fanny with curious eyes, wondering how such an idea

could ever have entered into his father's mind.

CHAPTER III.

UNCLE VALENTINE.

TWO or three months elapsed, and one evening Philip was called in

from a little party at Mr. Tabor's, to find the whole house in

confusion, one servant having been sent for him, and one for the

nearest doctor, while Fanny stood crying helplessly over his

father's chair, in which the old man was, to all appearance, dying. He had a long illness nevertheless, or rather a long dying; and, as

he lingered for months, Fanny

watched over him with the greatest devotion. He recovered

consciousness, but not the power of speech, or even of motion; so

that you could but dimly guess at his meaning by the expression in

his eyes.

Both his sons were present at his death-bed; but it was Fanny to

whom he looked for everything—literally looked, for she watched his

eyes, and knew when he wanted anything. She had raised him on the

pillow, with Philip's help, and he was actually making an effort to

speak, an effort which became painful to witness as it increased in

intensity. He was evidently expiring; but again and again he roused

himself, trying to articulate, while one and another bent over him

with words of soothing.

"It is nothing be wants," said Fanny. "It is something he has to

say. It is you he seeks, both of you, not me;" and she stood back,

that his sons might draw nearer.

The long-pleading, fast-fading gaze wandered from one face to the

other. Francis remained mute; but Philip stooped and said in clear

tones, "Do not trouble yourself about anything. We will try and find

out what you would wish to have done, and do it." There was no sign

that the words had penetrated the dying ear; but his eyes rested on

Philip a few moments longer, and then closed for ever.

Before the funeral the brothers had begun to look into their

father's affairs, and to find that they were in a very disordered

condition; but on the eve of that event there was a quarrel, and

Francis washed his hands of them altogether. On the day after he

went away, and all correspondence between the brothers ceased.

Philip Tenterden then prepared to leave his father's house, which,

however, Fanny Lovejoy took over, furniture and all. She was rather

hurt that Philip should go away, and that he should be so very

particular as to a valuation of the things. She liked round numbers,

especially with cyphers to them; and her affairs were to be managed

by Philip, as they had been managed by his father, so what could it

matter that everything should be so rigidly set down to the last

sixpence before Fanny commenced housekeeping on her own account.

"Tell me what has happened," said Philip, rather abruptly, breaking

the pause.

"Oh yes," cried Fanny, with another little laugh, provoking beyond

everything to her listener, who would have given her a certificate

of lunacy on the spot, and with a clear conscience. "He has turned

up at last; I knew he would."

"Who has turned up at last?" said Philip.

"Uncle Valentine. Papa had a younger brother than Joshua, you know,

one who went away and married beneath him, and was never heard of."

"Well, have you seen him?"

"Yes, last Monday; that's, let me see, two days ago. I was going

out, but I didn't go, when he came to the door, and asked for Miss

Lovejoy—asked if she lived here. The servant said 'Yes,' but didn't

ask him in. She asked what he wanted, and he said he wanted to see

me. And she said he couldn't, for she thought he was a man selling

pencils or pens or something, for he looked rather shabby. But I was

listening in my bonnet and cloak, and I heard him say that he was

father's own brother, and I ran down-stairs as fast as I could, and

asked him to come in."

"How do you know he is not an impostor?" said Philip.

"I knew he was Uncle Valentine," said Fanny, "the moment I heard his

voice; so I had him in and fetched him a glass of wine, for he was

all of a tremble."

"How did you know him?" asked Philip, interrupting her.

"By his voice; it was so like papa's," replied Fanny.

"But that is not enough. Did he show any knowledge of the family?"

asked Philip.

"I told him papa and Uncle Joshua and all the others were dead, and

that I was left all by myself; and he told me that he and his family

had come down in the world, and were in great need of help just at

present."

"I thought that would be the case," said Philip, in a hard tone: "and of what does his family consist?"

"Oh, he has a wife and four children, nearly grown up; the rest are

dead, like ours."

"He wanted money, of course?" said Philip, quite prepared to find

that she had given all that she possessed at the moment to a rank

impostor.

"Yes, I suppose so," said Fanny; "but I didn't like to give him a

little and send him away like a beggar. A little would not do him

any good. He wants enough to set him on his feet, he says."

"Doubtless," said Philip, who was now compelled to admit that it

must have been Uncle Valentine of whom he had heard.

"And I thought I would like you to advise me what I ought to do,"

she added.

"As far as I ever heard," said Philip, "your uncle broke off all

connection with his family of his own accord; and he has sought you

out now only for what he may get."

"I wish Uncle Joshua had been alive," said Fanny. In his lifetime,

the bachelor uncle had been habitual referee on all occasions of

difficulty.

"Or your father," she added. "Perhaps, after all, I ought not to

have anything to do with them."

Philip was silent for a little. There was a conflict going on in his

own mind, and he became for a moment oblivious of his listener,

whose round dark eyes were fixed patiently and wistfully on his

face.

"No, I cannot go so far as that," he answered, after a time. "These

people, if they are what they profess to be, are your nearest

relations. The children can have no blame in the matter, and they

are your first cousins. I think you ought to see them, and form your

own opinion, and help them as far as you can without injury to

yourself, for that, remember, would also injure your power of

helping them hereafter. Give them what you can spare out of your

income, but do not pledge yourself to anything like setting them on

their feet. If people can't get on their own feet," he

concluded with severity, it's likely they won't be able to stand on

them."

"No, no; I'll take care," said Fanny, joyfully, having received the

sanction which she had desired. "I'll take care. You may trust

me;"

and she laid special emphasis on the last syllable, as if it was

impossible to doubt her sagacity and insight. "Father always told me

never to touch the capital, and to trust Mr. Tenterden. Do you know,

Philip," she added, with solemnity, "I would like to make my will."

Philip answered nothing, and she wandered off into less important

matters, certain to return to it at a greater or lesser interval.

Walking home that night—and he walked the whole way, through suburb

and bye-way, over bridge and thoroughfare—Philip had food enough for

reflection. He strode along, with set, drawn lips

and knitted brows, and when he arrived at his own door he actually

reeled, and had to grasp the railing. The sensation was not one

arising from bodily exhaustion—he was unconscious of fatigue in

those lithe strong limbs—but from a concentration of thought, which

the sudden stoppage at his own door had jarred.

Mary had kept in his fire, and now asked if he wanted anything, with

sleep in her brown, doggish eyes, at once faithful and furtive.

"I'm sorry I've kept you up so late," said Philip, kindly. "I shall

not want anything."

Mary could have lain down to sleep at the back of the door for pure

appreciation of his courtesy, as she turned away with her "Good

night, sir."

It was indeed Uncle Valentine who had turned up—Uncle Valentine,

concerning whose beauty and whose gaiety of heart traditions still

lingered among the friends of his family—Uncle Valentine, who had

set out on the high road of life with such brilliant expectations,

such dazzling visions of success. His family had heard from him at

first from time to time, each letter more overflowing than the last

with hope and happiness. Liverpool was the place where he finally

settled, and was lost sight of. There he had begun business as a

general merchant, with a partner who had money it was to be hoped,

as Valentine had but a few hundred pounds. Friends heard of the

beginning of the business, but never of the end of it—at least from

him; but the general business was reported to have ended in general

bankruptcy, and with the absconding of the partner with the money of

the firm, which appeared to have come entirely out of other people's

pockets. At the very first sign of failure, Valentine had ceased to

communicate with his friends. It was like him to wait for better

times, and to go on sure of the future, denying himself everything

but hope; but the better times were long of coming. He had been

heard of again as a clerk in a Liverpool warehouse, married to the

daughter of his lodging-house keeper.

Later, he had gravitated to London; but by that time both his

brothers were dead, and the place that had known them in the vast

city knew them no more. He had not even heard the names of the

people who had received and protected his orphan niece, and he had

not been anxious to make inquiries. He had still his fortune to

make, and firmly believed that he would make it yet, though his

locks were turning grey. He threw up a plodding situation as town

traveller to an oil merchant, with £150 a year—on which his family

had lived in comparative comfort—in order to turn commission agent,

and make fabulous sums by per-centage on a patent invention. The

pretty little house and garden had to be given up for a stifling

court, for nobody wanted the new invention, and his old post was

filled up. Since that time, endless had been the migrations of the

family, and legion on the agencies which Mr. Lovejoy had held; but

the invention had evidently not yet been patented by which his

fortune was to be made. But he could now look back upon prosperity as well as forward to it, and that was a gain. The days of

his prosperity were those of his small but steady income, and his

pretty cottage home. What flowers he used to rear in its garden. To

his fancy they were brighter than any ever seen at the most

aristocratic flower-show; what luxuries he enjoyed of Mrs. Lovejoy's

own making; what holidays he had with the children, who were

dressed in all the colours of the rainbow, in wonderful frocks and

bonnets, of Mrs. Lovejoy's own construction. He had an excellent

wife, and had reason to know it; one who made the most of every

sixpence, and who believed in her husband with all her soul.

Alas! that these happy days were over and gone; alas! that she no

longer believed in him, though she still made the most of every

sixpence, and even helped to earn them. Husband and wife had been

falling more and more apart; they had long been sinking deeper and

deeper into the slough of poverty. One after another of their

children died, always, it seemed, owing to some preventable cause,

or rather some cause which poverty alone made unpreventable. They

had been very pretty as children, and they grew up absolutely

lovely; but the younger ones had been sadly neglected. He tried to

teach them himself, and succeeded with the youngest, Ada, who

learned without any trouble, remembered everything she learned, and

had the voice of an angel. Indeed, all the girls had sweet voices,

and picked up every song they could hear, or induce their father to

sing to them. They had had a piano in the days of the pretty

cottage—one their father had picked up at a sale. It had been Ada's

delight as a baby, but not more than it had been her father's. Even

after the old piano had to be sold, the singing went on. What cared

the blithe young hearts for plainest fare or lack of gay garments;

but it had gradually died down, as they grew older, and care fell

more heavily, and the voices were seldom heard mingling in glee or

chorus, as in more childish days.

They were very silent, and very busy at the hard, ill-paid work,

which was their last resource, when their father returned one

evening in elastic spirits. He had been coming home of late worn out

and depressed, and the change was visible in his brisk gait and

happy smile.

"You have had a lucky day, papa," cried Ada, her pale face lighting

up all over.

"I should think so," said Mr. Lovejoy, rubbing his hands, and

simmering with good tidings; "the luckiest day of my life is this."

"What is it?" asked Geraldine, looking up from her work.

"Do tell us, papa!" cried Ada still more eagerly, laying aside hers

altogether.

Mrs. Lovejoy looked up for a moment, and continued her task with an

energy of indifference.

"I've found out a cousin of yours, girls—my brother Frank's only

daughter, living all by herself in very good style—indeed, she is

quite wealthy, I fancy, and without a friend in the world. I am sure

if I had known that a daughter of Frank's was left in that lonely

way, I would never have rested till I had found her. As it is, it

was the merest accident that I discovered her. I saw the name on a

doorplate—it's an uncommon name, ours—and I thought I would ask who

lived there. I asked a baker's boy, who served the house, and he

told me that the lady was single, and I felt sure it was Frank's

daughter. I had seen her, you know, when she was a very little

girl."

"But how did you know, papa?" said Ada; "it might have been another

Miss Lovejoy."

"You can't account for intuitions, Ada; I have had them all my

life, my dear," he answered blandly.

Mrs. Lovejoy sniffed.

"And in this instance my intuition was verified, you see; and, what

is more wonderful, my niece recognised me at once, and bade me

welcome. She was extremely kind."

Mrs. Lovejoy could not help betraying some slight interest; but her

husband's relations had been rather a sore point. She thought that

in some way or other they might have turned up sooner to help them

in their straits, only that she had given up believing in any help

by or through her husband.

He was now assailed by a shower of questions: "How old was she?

What was she like? Was she beautiful?" those were Geraldine's

questions. "Was she clever?" was Ada's.

Mr. Lovejoy found the queries rather difficult to answer. "One thing

I feel sure of," he said evasively, shirking the beauty and talent

queries, "she is kind—she will help us. I told her that I only

wanted to be set upon my feet; with a very little capital I could

realise a handsome income on the patent polish for instance—that

sold well, if there had been any profit on it."

"And what did she say?" asked Mrs. Lovejoy sharply.

"She said she would gladly do anything in her power. Of course I

told her that we did not want anything as a gift—that money affairs

even between near relations were matters of business; in all of

which she acquiesced. Yes, she was most agreeable," he added warmly,

"and she is coming to see you very soon."

"To see us!" cried Ada, joyfully.

"To see us!" echoed Geraldine, ruefully; "I shall have to run

up-stairs and hide myself, I'm sure; look at my feet."

"You needn't trouble yourself about your feet, nor yet about

your head, Jerry; she'll never look near us," said Mrs. Lovejoy,

adding, "make haste, or we shall have to sit up to finish, and waste

coal and candle."

CHAPTER IV.

LUCY TABOR.

THE room was already full of guests when Philip presented himself at

Mrs. Tabor's, on the 28th. After paying his respects to the busy

host and hostess, he took up his station close to the door, a

position from which his quick eye could take note of every person

present. There, sunk in a low easy chair, was Fanny Lovejoy, airily

attired in black net, and fanning herself with a black-and-gold fan. Beside her, seated on a high chair, and also in black, evidently

worn as mourning, was a most attractive-looking young lady, fair,

slightly drooping, and pensive, and entirely free from

preoccupation. Philip catches her eye and bows, then his own wanders

off again. The yellow lady with the black hair, the blue lady with

the light hair, and the white and pink ladies with the brown

hair—that was the rather uncomplimentary fashion in which Philip

mentally distinguished the ladies present. When he had come round

again to the yellow lady, he turned away his eyes; she whom he

sought was not there.

Lucy had not been in the room when he entered, but presently she

came up behind him, and frankly saluted him by name. He started

perceptibly, for he had been looking the other way; and at this she

laughed, saying gaily, "One would think I was a ghost."

"I think you are," he said.

"Why?" she asked.

"I'm not going to tell you," he answered.

"It's one of your riddles. I can guess," she answered, merrily. Such

quips and cranks had been a favourite pastime in the old days, when

Philip had sat with his legs over the garden wall.

She stood with her head a little on one side, trying to guess. "It's a long time since you were here, but it has nothing to do with

that." A pause, "Won't you help me?"

"No," decidedly, from Philip.

"Then I give it up," said Lucy.

"I think you had better," said Philip, grimly.

"I am so glad you came to-night," she went on, putting a world of

sweet cordiality into the commonplace words. "You used to be at all

our parties;" and she looked, though she did not say, as if they

were pleasanter then.

But he did not respond; and when she went away to another corner, he

did not follow her, as she hoped and expected—for she wanted a chat

with her old kind playfellow—so she held aloof from him, frankly

disappointed, as any one might have discovered with very little

pains.

It is a difficult matter to describe Lucy, who was neither short nor

tall, slim nor stout, dark nor fair. Her features were rather round

and childish; but hers was one of those illumined faces which seem

transparent to every emotion, where the large clear eyes and soft

full lips seem capable of expressing to the utmost the joy of joy,

the very woe of woe. As yet, happily, Lucy had lived in the

sunshine, and the illumination was one of gladness and of mirth. She

was not a sentimental girl. She was too honest to manufacture

feeling, and too shy at heart, with all her frankness, to show it;

and she was not sarcastic, for sarcasm gives pain, and Lucy could

not bear to give pain; neither was she opinionated, as some young

ladies are, for she had not two opinions in her dear little head

that did not belong to somebody she loved, and she exercised her intellect in making them agree with each other, so as to allow her to

hold both when they happened to oppose—and not such a bad exercise

of intellect either. But this is a description in negative, which

every one who knew Lucy Tabor would protest against, for she had the

most perfect individuality in the world.

Philip followed this charming individuality with his eyes, and saw

her provided with a companion, a young man whom he knew, a pleasant

fellow, and the best of talkers—at least in the opinion of

unprejudiced people, which you may have begun to see Philip was not.

"There he goes," thought that gentleman; "just like a

barrel-organ—any tune you please. Music, literature, art; art,

literature, music; " and he stalked over ostentatiously to where

Fanny and her companion sat.

He shook hands with Fanny, who was radiant with good humour, and

more ceremoniously with her neighbour, Mrs. Austin, the widow of the

late senior partner, whose name was still retained in the firm. Mr.

Austin had been old enough to be her father. People had marvelled at

the marriage after they came to know her; for she was so unlike the

kind of woman who marries from mercenary motives. They rather

suspected her of some great sacrifice. Then she had behaved so well

to Mr. Austin. She had waited upon him through a long and trying

illness with the greatest sweetness; and he, poor man, was anything

but sweet. Her temper was angelic, every one said, for the old man

had been irritable nigh to madness; and all that she ever did was to

leave him quietly to his nurse, and take a walk for the sake of her

health, or read for an hour or two in her own room. When he was

unusually bad, she shrank and trembled and cried a little, and

stayed away as long as she dared. People said she had been sold to

him, and it was true; but she had behaved beautifully as wife and

widow. This was her first appearance in public after a year of

seclusion.

Mrs. Austin was what is called interesting. People liked to be

introduced to her, and wanted to know more of her. There was a

wonderful sadness in her face, which was, perhaps, its attraction. By the way, she was a perfect contrast to Lucy. Her face was an

opaque one, with long and slightly sharp but perfect features, and

large, but rather dull grey eyes.

Music had commenced, and was going on vigorously. It was a noisy

duet which was being played; and two young ladies appeared to be

scolding each other, one on each side of the performer. Philip stood

behind Mrs. Austin in gloomy silence. She tried to say something

that would lead him to talk, but hardly knew on what subject to

begin. Had he read a certain book, the best of the season? He had;

and they discussed several in succession.

"You are almost as omnivorous a reader of fiction as I am," he said.

"I should never have guessed it," she replied, smiling. "It is my

world, this world of fiction; much more real to me than these

living men and women."

"But it is necessary to correct one's ideas by a little knowledge of

living men and women," said Philip, smiling.

"But how is one to get it?" she replied. "One knows so little of the

people one meets. If I knew their histories, I would cease to be

afraid of them."

"Afraid of them!" he repeated. He had hated heartily a good many of

his fellow-creatures, but he had feared none. Then he reflected that

she was a woman, and might fear where he hated. He had a strong

desire to combat her fears, however; and he found himself assuming

the attitude of a defender of human nature. "Men are bad enough," he

said, "but they are not so bad as fiction paints them. I believe

that, in this, imagination outruns reality. Worse things have been

imagined than were ever done, I fancy."

"What dreadful things are in the papers, then," she said.

"You ought not to read the papers," he said impulsively. "You must

remember that they drain the impurities and crimes of a whole nation

into their pages. They represent life even more unfairly than

fiction. If I had a sister, I would not allow a newspaper to enter

the house."

"You are rather arbitrary, I think," she answered, with brightened

eyes. "Do you think women ought to remain ignorant of all evil?"

"No, I am not speaking from the obscurantist point of view; I am

simply pleading for a fair representation of life as it really is. When you read the daily papers, you are apt to forget from what a

wide area their daily allowance of horror is drawn, and that a large

proportion of crimes—all the worst of them, I am inclined to

believe—are the result of aberrations of intellect."

Mrs. Austin smiled at his earnestness. "I have not got the length of

fancying I may meet a murderer any day," she said. "It is not the

passions of my fellow-creatures I am afraid of; it is rather their

harsh judgments, their repulsions, their discords."

"And fiction, for its own purposes, exaggerates them all."

"Why do you read so much of it then?" she said, laughing, and

showing her white, regular teeth.

He laughed also. "For the sake of company," he answered, "or, to

put it grandly, to satisfy my social instincts."

"Are you so lonely, then?" she asked, in a voice full of sympathy.

"Lonely enough," he answered, grimly watching Lucy, who seemed to be

enjoying herself quietly; while her companion divided his

attentions, keeping however, as Philip could see, the largest share

for Lucy.

"Your friends complain of your keeping aloof from them," Mrs. Austin

said frankly.

"Do they?" he asked, with sudden eagerness. "Mr. and Mrs. Tabor

especially," she added.

"Yes, they are true friends," he replied, warmly; "they are not

subject to the chills and changes of those who turn whichever way

the wind blows."

"And Lucy is such a darling," put in Mrs. Austin; "she is just as

steadfast and sincere."

Thus they talked while the evening flew on, condescending to little

personal matters of likes and dislikes, and finding, as only people

who have kept their first youth—though both Philip and Mrs. Austin

might to ordinary eyes have appeared to have lost it—find, that they

had very much in common, and yet feeling, as only two people who

have gained by the loss of youth feel, that it is not necessary to

be lovers to enjoy each other's society. These two felt that they

could never be strangers again, as, though claiming a longish

acquaintanceship, they had hitherto been. Each really knew a little

of the other, that little which enables to know more. A certain

confidence had been established between them.

Then Mr. Tabor came up, and said, holding out one arm to Mrs. Austin

and another to Fanny, who had not spoken a single word during the

evening, but had sat beaming and listening, "I have come to offer

an arm to each of you, if you will go down to supper."

"I will take Mrs. Austin," said Philip, and he led her away. Just

before he spoke he saw Lucy led off by Mr. Wildish.

But Mrs. Austin, who was very fond of Lucy, led him to the seat

beside her, which was vacant, and so Philip had to stand and serve

before her. He attended to Mrs. Austin's wants, and then he went

away and ate a hearty supper of cold chicken and champagne.

When they were all up in the drawing-room again, the same group

gathered in the same corner, with the addition of Mr. Tabor. "By

the way," he said, addressing Mrs. Austin, "Tenterden here might

look over the papers you were speaking to me about." Then, turning

to Philip, he explained that Mr. Austin had left a mass of private

papers, which it was desirable to go through, and Mrs. Austin

required some help in doing so, as it was impossible for her to know

what was valuable and what not, many of them relating to the

affairs of the firm.

Philip readily promised to devote one or two evenings a week to the

task, the time for beginning to be settled by a communication from

Mrs. Austin. But suddenly, and without warning, Philip stalked away. He had seen an opportunity—Lucy standing unoccupied and alone—and he

reached her just as another music storm set in.

"I haven't found out your riddle yet," said Lucy.

"Have you been trying?" asked Philip.

"Yes, all the evening."

"Hasn't Mr. Wildish helped you?" he said wickedly.

"I did not ask him."

"You are not up in ghosts, Lucy; you might have seen me acting one

the other night, looking up at your windows. They were barred and

bolted; nothing but blackness to be seen, not a single ray of light

greeted me except that of the hall lamp." His tone was

one of light mockery, but Lucy looked up with serious eyes, and

asked wistfully—

"Why did you not come in?" She knew that he had been with Fanny.

"I was haunting the place where I had lived," said Philip.

"I shall never like to close our shutters again," said Lucy; "I

don't much like it as it is."

He had not answered her question; but answering questions does not

matter much when every look and every tone is an answer to unspoken

questionings, that go deeper than words.

Philip and Lucy kept together for the remainder of the evening.

Philip indeed saw nothing and heard nothing, beyond Lucy's happy

voice. In vain young Wildish strove to enter the charmed circle; he

was obliged to fall back and yield to Philip the claims of old

acquaintanceship. That gentleman did not even notice Mrs. Austin go,

and he was himself among the last to leave.

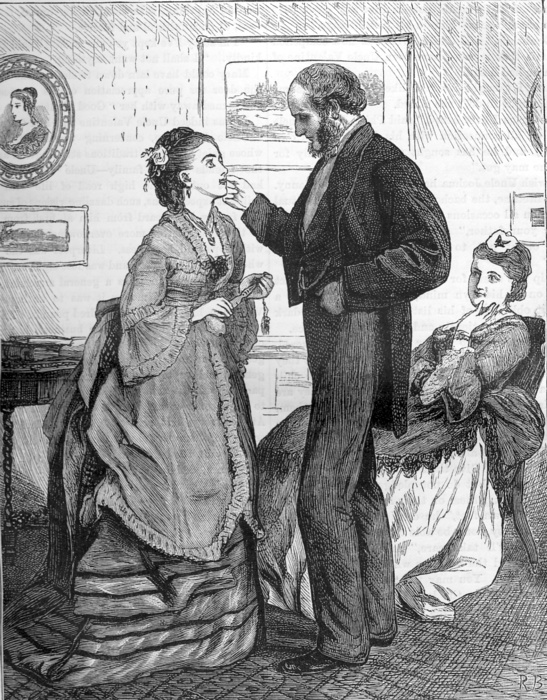

"Well, puss, and how have you enjoyed yourself?" said Mr. Tabor,

touching Lucy's cheek, where the pure pale colour had deepened; "you

don't look sleepy!"

"I thought it rather slow at first," said transparent Lucy, "but

it went off very well; don't you think so, mamma?"

"Yes, my love," replied Mrs. Tabor, absently, and looking wistfully

at the bright eyes and glowing lips, as bright and as glowing as if

there were neither weariness nor woe in all the world, and no need

of the night for either rest or weeping.

(Drawn by ROBERT

BARNES)

"Well, puss, and how have you enjoyed yourself?"

CHAPTER V.

A LAWYER'S LEGACY.

Sunday Philip called on the Tabors at the hour when he knew that

Lucy would be out teaching her class at the rector's school; and he

went away before she returned, to the great relief of Mr. Tabor, who

had been made uneasy in his mind by sundry observations which Mrs.

Tabor had made on the night of the ball, and who felt—what a good

many fathers feel, in spite of modern mammonism—utterly disgusted at

the idea of giving up his daughter to any young fellow, however

worthy. How could any young fellow be worthy of a creature who had

absorbed all the care and affection of two whole lives? how could he

possibly have earned a right to such rose-leaf kisses as dropped

every evening on the crown of his bald head when Lucy came to bring

him in to tea and to coax him out of his guineas—not for herself,

that would have been easy, but for some object of charity which he

considered doubtful; and the little puss had lighted on this fact,

and used it as an argument on occasions like these. "You know,

papa," she would say, "you would give me ten times as much for a new

dress, if I liked to have it, and I would rather have this and go

with an old one. Lucy Tabor liked to shower gifts about her like a

fairy princess, for pure delight in giving; and I think, for pure

delight in giving, she might one day give herself, if anybody wanted

her very much.

"Mr. Tenterden has been here, my love," said her mother, watching

the effect of her words; "and he left his kind regards for you."

But Lucy made no remark. She neither turned red nor pale, nor

behaved in any way unusual to her. Only she seemed that evening more

lavish of her kisses and her smiles; seemed to throw herself more

entirely into the sacred Sabbath music which her father loved. The

small but perfect circle of husband, wife, and child, spending the

evening together and alone in tranquil happiness, seemed as yet

independent of the great chain of life, of which, with all its

stress and strain, they formed a link.

"You see," said Mr. Tabor, when Lucy had gone to her room, "there is

nothing the matter with the child."

"The matter with her!" repeated Mrs. Tabor; "of course not."

"Yet Philip did not seek her to-day as he might have done, if he had

chosen," said Mr. Tabor. "He avoided her, I fancy, and she has not

drooped in consequence."

"No, that sort of thing does not come on all at once, like a fever,

with girls like Lucy. But if she cares at all for Philip, as I think

she does, this way of his of keeping at a distance from her and,

than devoting himself to her, as he did last night, and then leaving

her again, will only end in making her love him all the more. I have

known more than one instance of a girl having her heart and life

completely wasted in this way."

"Remember what an old acquaintance Philip is," said Mr. Tabor; "he

would never treat our little girl in that way."

"Not knowingly," said Mrs. Tabor.

"Philip never does anything unknowingly," said Mr. Tabor.

Mrs. Tabor was convinced against her will, and every one knows what

that means: she was decidedly of the same opinion still.

Next day Mrs. Austin communicated to Philip, through Mr. Tabor, her

desire, if it was convenient, to begin upon the papers at once.

After some little consultation, the Thursday following was fixed as

the date when the work should begin; and Mrs. Tabor resolved to put

on all her armour of defence against the foe who would thus be in

such close proximity.

On Thursday evening, accordingly, Philip presented himself at Mrs.

Austin's house; but he showed no intention of invading that of her

next door neighbour, further than by glancing up at the windows.

That glance, however, was enough to cause him first to smile and

then to frown. The smile was for Lucy, the frown was for himself.

Something more than a fool it was that he called himself when he saw

a light streaming through a chink left unclosed in the shutter of

what he knew to be Lucy's room, a little sitting-room set apart to

her sole use, and opening out of her mother's drawing-room.

Philip was shown into Mrs. Austin's presence. An elderly lady was

with her, to whom he was introduced, Mrs. Austin saying simply, "My

mother, Mrs. Torrance, Mr. Tenterden." Then they all three adjourned

without loss of time to the library, a room which Philip knew well

as the usual sitting-room of the late Mr. Austin. A cheerful fire

was blazing in the grate, and a couple of shaded reading-lamps were

burning on the table. Three chairs were set in the circle of light,

but a great leathern one stood back against the wall, among the

shadows. It was the chair which had always been occupied by the late

master of the house, and Philip had a curious feeling of the harsh

old man's presence for a moment.

The papers which Mr. Austin had left behind him and which were now

to be examined for the fin time, were contained in a series of black

tin boxes, numbered and ranged along the wall untie: the lowest

bookshelf. They agreed to begin with No. 1, and proceed in a

thoroughly methodical manner, concerning which Philip gave a few

simple directions. He placed the box between them on the floor, and

at the side of each a waste-paper basket. Mrs. Austin was to hand

over to her companion whatever seemed of the slightest importance,

or related to business of which she had no knowledge; while

circulars or unimportant notes were to be thrown at once into the

basket. Philip, on his part, was to consult Mrs. Austin concerning

the more strictly private papers; while he set aside any of the

business ones which seemed to him worthy d preservation. Mr. Austin

had been one of those men, generally anything but benefactors of

the' kind, who never destroy a single scrap of paper, written or

printed, which comes into their hands, There they lay, papers of

thirty years back, done up in bundles, and in packets tied with red

tape, or threaded on cord, just as they had been whet removed from

their dusty pile—circulars, notices of meetings, appointments,

drafts of letters and of ancient briefs, notes of cases,

instructions to counsel, The baskets at their feet were filled

almost in silence. They had not exchanged more than half a dozen

brief sentences when Mrs. Austin rang the bell to have them removed

and emptied, and they paused to take breath.

Philip had glanced now and then at Mrs. Torrance, seated in the

chimney-corner, with an idle desire to know what sort of woman Mrs.

Austin's mother might be. Whenever he did so, he found the lady's

eyes directed on her work, though if he had glanced up a moment

sooner he might have seen them watching her daughter and himself;

and yet if he had glanced up a moment sooner the probability is that

Mrs. Torrance would have been looking at her work all the same. She

held an ivory mesh in her still deft and youthful-looking fingers,

and netted with amazing rapidity, fastening every knot with a jerk

which seemed to say, "That is a final business." The web at which

she worked was stuffed into, and proceeded out of, a linen bag which

lay on the floor; and Philip found himself taking an interest in the

work which seemed so slight, and yet so strong. It seemed to him as

if she was weaving the web of fate. It, too, is slight and strong;

made up of the slightest threads of action, twisted ever so little,

and yet not to be undone except by the fatal shears.

After the brief pause, Mrs. Austin turned to her task again. She

evidently did not desire to play over it; and it was no child's

play, for the mass of papers to be got through was immense.

They had tea a little later, and had to wash their hands in order to

partake of it. Mrs. Austin's almost transparent fingers were black,

looked blacker than Philip's, with the dust of those bygone years.

After tea they resumed their work once more. At ten o'clock they had

filled their baskets three times over, but they had not got through

the first of the black boxes. However, Philip then rose and took his

leave, and Mrs. Austin acknowledged, with a sigh of fatigue, that

she had had enough of it for one evening. The task was to be resumed

on that day next week, and so on each week till it was finished.

It certainly was not particularly interesting work, and yet somehow

Philip had been interested in it. He took his way homeward under the

December stars with a calmer spirit than usual, even after glancing

up again at the neighbouring window, and ascertaining that a light

was still burning in Lucy's room for the benefit of any homeless

ghost who might be roaming near. Why he felt calmer than usual he

did not ask himself. It was probably owing to a combination of

influences: to his having had no time to brood over his grievances;

to his having been surrounded with the subtle atmosphere of womanly

refinement, to which he was now a stranger; and to his sense of

kindly feeling in having been engaged in. helping one so gentle and

sweet as Mrs. Austin in the performance of a disagreeable duty.

Philip's grievances, as far as they were known, did not bring him

any sympathy. It was known that his father bad left nothing,—had

even been to some extent insolvent, though to what extent no one

knew, as his sons had evidently taken his debts upon their own

shoulders. Then he and his brother had quarrelled,, and held no

communication with each other. But these things did not appear to

justify the change in him, or to account for the mode of life he had

adopted.

When he had gone, a little colloquy took place concerning him

between the ladies he had left.

"My dear, I don't like that young man," said Mrs. Torrance,

fastening a knot with an additional jerk.

"Indeed, mamma," said Mrs. Austin, but with very little

astonishment. "Mr. Tabor likes him, and trusts him, and so did Mr.

Austin," she added.

She did not venture upon any opinion of her own; she knew her mother

too well for that. Mrs. Torrance would have simply jerked another

knot, and said something which implied that her daughter's remark

was quite irrelevant. Mrs. Austin did not even inquire into the

reason of her mother's dislike of Mr. Tenterden; but her mother was

ready to give it, and did give it.

"I should think he was designing, Ellen," she remarked.

Mrs. Austin replied quietly, " There is nothing make you think so,

mamma."

Mrs. Torrance was evidently rather astonish at the decision of the

reply. Her daughter was n ordinarily so decided. She went on, "It

strikes me that he is remarkably ready to give up his evenings to

this tiresome job. It is not likely that young man like him has not

engagements that pleasanter—at least if he has not some end in vie)

You are young, my dear Ellen, and rich, and he might think it an

excellent opportunity—"

"Mother," interrupted Ellen Austin, but the word ended in a choking

sob.

Mrs. Torrance looked perplexed. "I did not me vex you, my dear," she

said. "You don't care for him, do you?"

"No, no—it is not that," she answered, but s did not explain. She

went and divided the curia' and let them fall and shroud her, as she

looked out into the night with a mute pitiful appeal.

Mrs. Torrance netted on faster than ever, glancing up at the curtain

that concealed her daughter's figure. Nothing was sacred from that

woman's tongue, though she could bid it be silent, tie it a double

knot if she chose; but she knew very Wei the power of talk over

feeling—she knew that rose- buds unfolded leaf by leaf before their

time will not open, but die. It was, or had been, the secret of her

power over the finer nature of her daughter; the terror of that

tongue of hers, not loud, but sharp—sharp, and, if necessary, tipped

with poison, the poison of detraction and malice. And at present she

was only trying experiments. She did not know how much, if any, of

this power remained to her. As a married woman, whose husband had

determinedly kept Mrs. Torrance at a distance, Ellen had slipped her

neck out of the yoke, and Mrs. Torrance was not quite sure that she

would submit to it again. But Ellen felt that she would. It is very

easy to despise her for it, but gentleness was the habit of her

soul, and obedience to her mother had been the habit of her life. It

did not matter that hers was by far the larger nature, in intellect

as well as heart, and that sometimes she knew it; her mother's sharp

words, her mother's watchful eyes, would constrain her against her

judgment and her will, and she would act upon her mother's decisions

instead of upon her own, accept her mother's conclusions instead of

her own—in fact, hand herself over bodily to every tyranny, while

she escaped in the life of the soul. There was in Ellen a defect of

will, a defect which had been her father's, and had been his ruin.

CHAPTER VI.

POOR RELATIONS.

ACCORDING to her

promise, and backed up by Philip's advice, Fanny Lovejoy determined

to know something more of her long-lost relations. They lived at a

considerable distance, and as Fanny was no pedestrian, and was apt

to lose her way whenever that feat was possible, she hired a

brougham for the occasion, and set out one morning at ten o'clock. Less than an hour's driving took her to their place of abode—one of

an endless row of small houses in an unsavoury suburb of district

S.E. But the houses, though small and dingy, looked respectable, and

did not prepare the visitor for the poverty of the interior. Fanny,

like many a woman of her class, knew nothing whatever of the homes

where poor men lie.

A tall, gaunt, middle-aged woman opened the door, and opened it only

a very little way, informing Fanny, who inquired for Mr. Lovejoy,

that her husband and son had gone to business.

"I'm Miss Lovejoy," said Fanny, beaming on her in her usual manner.

Not the ghost of an answering smile dawned on the woman's face, as

she said with a sigh, "I'm Mrs. Lovejoy. Will you walk in, miss?"

Crabwise, Fanny got through the narrow doorway and was ushered into

the parlour. There was a handful of fire in the grate, and a piece

of drugget laid down before the fire; but the room was bare of every

comfort else. On a table at the window lay a heap of work, which

looked like children's dresses, and two girls sat at the table, each

with a small embroidered garment in her hands.

"That is pretty work," said Fanny, advancing, and they both looked

up without speaking. "Are these your daughters?" she asked, turning

to Mrs. Lovejoy.

"Yes, that's Ada and this is Geraldine," said Mrs. Lovejoy,

indicating each; "Beatrice has gone to business."

"I am your cousin," said Fanny again, addressing the girls, and

holding out her hand before she took the seat Mrs. Lovejoy had

placed for her.

They each looked up with a pair of very bright eyes, and held out to

her a little thin chilly hand.

"Now go on with your work," said Mrs. Lovejoy to the girls in a

dreary hopeless tone, and they bent their eyes and began sewing

together the parts of each little garment.

"I hope I am not hindering you," said Fanny, looking to Mrs. Lovejoy

for an answer.

"Well, if you'll excuse me a minute," replied that lady with no

excess of politeness.

"Oh, certainly," said Fanny, and Mrs. Lovejoy thereupon disappeared.

Fanny was capable of a great deal of silence, and evidently so were

the young ladies before her. She had time to examine their faces,

and every detail of their dress and surroundings before another word

was spoken. She had time to notice that their flimsy gowns were

stained, patched, and torn; that they had trumpery earrings in their

small ears, and enormous chignons disfiguring their pretty brown

heads, that they had slim, graceful figures and clear

complexions—Geraldine with rose pink on her cheeks, and Ada pure and

pale as a white lily. Fanny's kind heart took in the pair at once. "Have you lived a long time here?" she ventured to ask.

"Oh yes, a very long time," replied Geraldine. Papa has often wanted

us to go away from here, but mamma wouldn't stir, she was tired of

moving."

"Well I might be," said Mrs. Lovejoy, re-entering. "I've had ten

children, and not two of them born in the same place; and I've

buried six, and not laid two of them together."

"Dear me! how sad!" exclaimed Fanny.

"And this house is handy for the City, and for the warehouse where

we get our work; and Albert's wife stays with us and helps pay the

rent," continued Mrs. Lovejoy, "so the girls and me can live."

"How quickly they work," said Fanny; "I've been watching them. I

could not do as much in a day as they have done since I sat down

here. Is it well paid now?"

"We have to work from morning to night, all three of us to earn a

shilling a day each. I've just been hanging up a few things to dry,

and I'll have to make up the time, for they're busy at the warehouse

with Christmas orders, and if you try to turn out the work when

they're busy, they'll try and keep you on when they're slack,"—she

had already found needle and thread, and was making them fly through

the stuff.

"But what does Mr. Lovejoy do?" said Fanny, reflectively; "you

oughtn't to have to work so hard as that." Fanny held the good

old-fashioned notion that money-earning belonged to the man's part

in the world's work.

"He's agent for selling something or other—something which nobody

ever wants to buy," said Mrs. Lovejoy with a burst.

"Dear me!" said Fanny; "why doesn't he give up selling it then?"

"He has given up things often enough, and worn the shoes off his

feet looking for something else, and when he got it it was worse

than ever; they wanted the new thing less than the old."

"It must be very disheartening," said Fanny with sincere sympathy.

"Disheartening!" exclaimed Mrs. Lovejoy, who had got upon her great

grievance, and was communicative in a cheerless fashion; "I should

think so, to keep going and going where nobody wants you, and asking

and asking, and never getting. I couldn't live such a life. When the

girls or me go to the warehouse, and they say they haven't any work

for us, we're hard put to it before we can go back again. It turns

me sick to have to beg for it like, and I've seen Ada and Jerry

crying before they'd do it. But nothing disheartens Mr. Lovejoy. He's been going to make a fortune every day the last thirty years,

and all the time we've been getting worse and worse off, till I

wouldn't trust to him any longer, and I only wish I had settled to

work before we got so poor and had to part with everything."

"You have a son?" said Fanny, wondering how such poverty had come

about.

"Yes, Albert has enough to do with himself. He has a wife and two

children, and he hasn't been fortunate." She was not going to be

communicative on this subject.

"And they live here?" said Fanny.

"Yes, up-stairs."

"Might I go and see them?" she asked.

"Oh yes," replied Mrs. Lovejoy. "Jerry, take your cousin up to see

Emily and the children." Geraldine rose, and it seemed as if her

wretched dress would fall from her tall figure as she led the way up

the narrow stair. But the rooms when reached were not uncomfortable,

though far from tidy; that is to say, they were carpeted, and one

furnished as a bedroom, the other as a parlour. Fanny was introduced

to a white-faced girl with a superabundance of dark hair, who was

suckling a baby; while a little fellow between two and three years

old stood by her side, quiet, but with evidences of recent riot all

around him. Fanny thought she saw traces of tears on Emily's face,

and after a little chat with the passive young creature retreated.

"We sleep up-stairs," said Geraldine, pointing upward as they closed

Mrs. Albert's door; and Fanny took it as an invitation to ascend,

and did not in the least observe the girl's evident reluctance.

"This is our room, and that is mother's," said the girl, as she

opened the doors, blushing crimson and coughing terribly.

"But you don't sleep here?" said uncomprehending Fanny.

"Yes, we do," said the girl, with a suppressed sob. Mother

had to

part with the beds when we were slack in the summer-time."

"Dear me!—dear me!" said Fanny, weeping, and stumbling down the

steep stairs. "You'll come and see me," she said to the group as she

re-entered the parlour.

Mrs. Lovejoy replied that she seldom went from home.

"But you'll let the girls come?" said Fanny. "Could they come and

dine with me on Sunday next?"

Mrs. Lovejoy hesitated. "Beatrice might," she replied; " she has

boots. But Ada's and Geraldine's are both worn out, and they catch

cold with the wet coming in. Other things they can make up for a

trifle, but boots are boots."

"You'll let me make my cousins a little present?" said Fanny, shyly. "This is a rather pretty purse;" and she put hers into Geraldine's

hand. "You can share what is in it between you;" and saying goodbye,

she hurried out of the house, with head and heart both a good deal

fuller than they could well hold.

The examination of the contents of the purse took place as soon as

the door had closed upon their visitor. Geraldine shook out into the

palm of her hand four sovereigns, and six-and-sixpence in silver,

and in spite of the impassivity with which she had received her

husband's relative, Mrs. Lovejoy trembled with excitement as she saw

the glitter of the gold. She had felt very little interest in the

advent of her husband's niece. She was only another of the mare's

nests which Mr. Lovejoy was perpetually finding, and which, far from

supplying the fabulous riches he had believed them to contain, had

failed to furnish his family with daily bread. She had listened

every day since the new discovery to schemes in which his niece's

wealth and his niece's influence bore a part, but in which so much

was taken for granted that Mrs. Lovejoy may be pardoned a little