|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XIII.

THE DEFENCE.

THE paper dropped from the hand of Dionysius Curling.

He was not an excitable man, nor a sentimental man, as we know. Yet

had the affair of Clara Melrose taken hold of his imagination in a

remarkable and unprecedented manner.

The statement contained in the Deepdale Gazette shocked him beyond

measure. How to reconcile it with the extraordinary fact of the

lady's presence here, in the midst of her accusers, remained as yet

in obscurity.

"She must have lost her senses," thought he.

He had scarce uttered this mental ejaculation when a tap at the door

announced the presence of Martha Beck.

"If you please, sir, the lady wishes to see you."

Dionysius started in his chair. He did not know how be could face

Clara Melrose just then.

"Yes, sir, and she seems to have something on her mind. Dr. Plume

thinks you had best come up and hear what it is, sir."

Dionysius rose slowly, and with dignity. He could not refuse to

listen to what this woman had to say. At the same time he fancied

the interview would turn out to be a confession.

With this feeling on his mind, he walked upstairs, and having been

duly announced, found himself in the presence of Clara Melrose. He

had no intention this time of being ensnared by any womanly device. He

desired Martha Beck to remain in the ante-room, within reach of his

voice, should the lady be taken faint.

Clara Melrose was sitting by the fire in the easy-chair. She was

still pale and wan; but it seemed to Dionysius as though he had

never before seen so sweet, so innocent a countenance. Her blue eyes

expressed naught save truth and purity, her open forehead gave no

hint of guile. Dionysius looked, and while he looked he marvelled.

She glanced up at him, and their eyes met.

Dionysius, bashful as a girl of sixteen, blushed to the very roots

of his hair.

The pale cheek of Clara Melrose remained without an atom of colour.

"I wish again to thank you for your kindness," said she, in the same

dulcet voice that had before half-captivated him, "and to express my

regret for the trouble of which I have been the innocent cause."

Dionysius bowed, as it was imperative he should at the conclusion of

such a speech, and from the lips of a lady.

"I am sure, sir," continued Clara Melrose, in the same dulcet

strains, "you will do me the justice to believe that I came here in

entire ignorance of my dear uncle's death."

Dionysius bowed again. He might have been an automaton.

"Ah, sir, in my dear uncle I have indeed lost a parent. He was

father and mother too. In fact, next to my beloved husband, he was

all I had in the world."

The remembrance of the Deepdale Gazette caused Dionysius at this

juncture to turn red in the face and emit a sound very like choking.

"I resided with my uncle, the late vicar," continued she, her

handkerchief to her eyes. "I was like a daughter to him, and the

remembrance of the happy clays we spent together in this dear house

must needs add to my grief. I am young, sir, in years, but it seems

as if I were already getting old in sorrow."

To look to Dionysius for sympathy, or, indeed, to appeal to him in

any way, was futile. So Clara Melrose proceeded:

"Perhaps you are not aware that my late husband was the nephew of

Mr. Melrose."

"I—I—believe I have heard so, madam," stammered Dionysius.

"My husband resided with me in the vicarage, sir, for three happy

years. Ah! so happy!" and the tears trickled down the widowed cheek

of Clara Melrose.

Dionysius looked, or rather, if we might use the

expression, glowered at her.

"Then, sir, came affliction. Ah! I know it is wrong to say so, but

it is hard at times to submit to the chastisements of Heaven!"

She paused, apparently convulsed with grief. Dionysius, alarmed,

glanced towards the door. His movement seemed to rouse her.

"You need not fear, sir, I am not going to faint," said she, smiling

through her tears.

He muttered a few incoherent words, the only intelligible ones being

that he should be most happy, but on what ground did not appear.

Again she smiled, partly at his oddness and want of tact, partly to

encourage him, and to dispel his fears. Then the smile faded, and

she resumed her story.

"Perhaps you may have heard, for my sad history is well known in

Deepdale, that my dear husband fell ill of our country's greatest

scourge―consumption?"

"I―I―think I have heard," stammered Dionysius, the contents of the

Deepdale Gazette staring him blankly in the face.

"And you may have been told that he was recommended to seek a warmer

climate?" added she, again appealing to him.

He murmured an inarticulate assent.

"Sir, we were poor. I had hard work to raise the funds which were

absolutely necessary for our journey." Here she paused, deeply

affected.

"Ah, sir," resumed the widow, when her grief had somewhat abated,

"as the event proved, all our endeavours were futile. It is true, I

obtained the means of reaching the more genial climate of Madeira,

and we landed in safety; but the dread disease had progressed too

far—"

Again she wept. There was something irresistibly touching in her

sorrow.

Dionysius, softened in spite of himself, ventured to offer a few

words of consolation.

"I need not have troubled you with these details, if it had not been

due to myself to explain my unfortunate position. My dear husband

died while in Madeira. Ah! were it not for the hope of reunion in

another and a better world―"

Again her voice failed, and she wept abundantly. Dionysius, further

softened, again attempted to console her.

"I had not heard from my uncle since I left England," resumed she—"a

circumstance which both pained and surprised me. I wrote to him

several times, and once I wrote to my uncle's churchwarden, Mr.

Crosskeys."

Dionysius gave a great gasp.

"To Mr. Crosskeys," continued Clara Melrose, glancing up at him with

some surprise; "but, alas! he, too, made no reply. I fear my

letters, and also those of my friends, were lost on the passage."

Dionysius made no reply.

"You may imagine my position, sir: a widow in a strange land, and a

destitute widow, likewise. My resources had all been exhausted

during the illness of my husband, and I had not the means of

returning to my own country. Providentially, friends were raised up

to me in my affliction. A sum of money was subscribed to enable me

to take my passage in a ship about to sail for England—a sum barely

sufficient, it is true; but I fondly anticipated finding my beloved

home as I left it, and that my uncle would receive me with open

arms. Alas! I had forgotten the sad and terrible, uncertainty of

life!"

She wiped away the tears that had welled forth again in spite of her

efforts to be calm.

"Alas! sir, you know the rest. You know that when, at length, I

arrived—for the vessel was delayed by contrary winds—it was to find

my last anchor reft away, my only refuge gone—except One, whom

indeed I have found to be 'a present help in time of trouble,' and

who found me a friend in my need."

She had told her story, and the dulcet strains of her voice no

longer sounded in his ears.

What was he to think? What was he to believe

Judging from appearances, it was an easy matter to decide. That fair

face, those eyes of tender blue, that absence of all hesitation or

guilty confusion, spoke of innocence.

But then the disclosure of Simon Crosskeys?—a disclosure made in

cold blood without any apparent motive—a full, complete, and, as

yet, uncontradicted assertion of Clara Melrose's guilt. What was he

to do?

But greater trials still were in store for him. The lady was,

indeed, somewhat exhausted by her recital. Yet, upheld by a feverish

energy, she was unwilling to let Dionysius go.

"And now, sir," said she, appealing to him with great earnestness,

"what am I to do?"

"Indeed, madam, I—I am incompetent—I really cannot tell you, madam,"

replied he, speaking the last words with precipitation.

"Oh, sir, pray do not leave me, until you have, at least,

heard—heard and advised with me upon my future plans! Pray sit down

again, Mr. Curling."

Mr. Curling did sit down, uneasily, it is true. Still he sat.

"I should like to remain in Deepdale," said Clara Melrose, "where I

am well known and respected."

Respected! could she possibly mean respected?

"I am told by your housekeeper that there is a cottage to let at the

entrance of the village. I know the place well. In my time a lady

resided there who kept a small school for young gentlemen. She used

to train them for larger establishments. Now it occurs to me that,

since she has left, an opening seems made for me by Providence."

"What! to keep a school here in Deepdale!" exclaimed Dionysius, half

out of his senses.

"Why not? My dear uncle took care that I should receive an excellent

education," said Mrs. Melrose, with a smile. "And I am sure my

uncle's parishioners would afford me all the support in their

power," continued she.

"With God's blessing, I might find the means of maintaining myself."

"But—the money," stammered Dionysius. "You said, pardon me, that you

were destitute."

"I know it," replied she; "but, at the same time, I have reason to

expect that some small sum will come to me in consequence of the

lamented death of my uncle."

"Of your uncle!" stammered Dionysius, petrified.

"Yes, sir. He had insured his life for a hundred pounds, to be paid

to me on his decease. Also he had bequeathed to me the furniture of

the vicarage. I am not, therefore, wholly without the means of

carrying out my project. As soon as possible, I should be glad to

have an interview with Mr. Crosskeys. I believe he was named as

trustee."

"Madam, you cannot be aware," burst out Dionysius. Then he checked

himself with such a violent effort that his face became scarlet.

"I am aware of the difficulty every woman finds in standing her

ground alone," said Clara Melrose, calmly; "but I am not one who

shrinks from exertion. I have been well disciplined, Mr. Curling."

He was silent. What could he say?

"I have written to Mr. Crosskeys," continued she, taking a sealed

envelope from the table, "and with your permission, I will send it

by your servant-man. Indeed, I was about to give it to Martha, when

something occurred to prevent me."

"I am thankful you did not," cried Dionysius, much excited.

She looked at him in surprise.

"Why so?" asked she, mildly.

"Because—no matter, madam—no matter. Only if you would be good

enough to give me—the letter—"

She hesitated, still surprised at his manner.

"I will see that it is delivered," stammered Dionysius, hardly

knowing whether he stood on his head or his feet. "My man is hardly,

in such a delicate matter, to be trusted

Mrs. Melrose, having given him the letter, leaned back and closed

her eyes. It was apparent that even now she had gone beyond her

strength.

Dionysius, all his fears revived, hurried into the ante-room to

Martha Beck.

"Go at once to Mrs. Melrose; she is going to faint." Away flew

Martha Beck, and Dionysius walked leisurely to his study.

"She is innocent as a lamb," thought he, "and Crosskeys is an

idiot!"

CHAPTER XIV.

"TIME AND TIDE WAIT FOR NO MAN."

"ON my word, Mrs.

Chauncey, this steak is done to a turn," said Reginald Chauncey in a

tone of profound admiration.

Frank heard the observation as he came in at the door of the

breakfast-room, the morning after his arrival at home.

At an early hour that morning, Frank, whose slumbers had been

light and uneasy, had become conscious of stealthy footsteps about

the house, and of the ordinary household arrangements being carried

on below.

This circumstance would not have interested him in the least,

had not the suspicion flashed into his mind that the said household

arrangements were being performed solely by his mother.

Under this impression he rose, and cautiously stole

downstairs to the room usually occupied by the family. As he

did so the sounds ceased, and as he approached nearer and nearer the

door opened, a startled face was put out to reconnoitre.

"Mother," said Frank, hastily, and in a tone of annoyance,

"what are you doing?"

"My dear, I have almost finished. I am only seeing to

things a little," replied she, still trembling with fright.

"Can I assist you?"

"Oh, no; and would you please speak lower, lest you should

awake him;" and she made a movement indicating that in the room

overhead Reginald Chauncey was stretched in lordly repose.

Frank retired, not, however, to sleep. A young man

under such circumstances was hardly likely to sleep.

At the present moment Reginald Chauncey, in an elaborate

morning costume, his hair and his whiskers trimmed to a nicety, his

ring on his finger, and his very nails in a state of perfection, sat

at the head of the table. By his side was that day's Times,

as yet unopened, and before him the steak under discussion, and all

his other little epicurean arrangements round about him. His

wife in her plain print dress, her simple cap and black apron, did,

it must be confessed, present somewhat of a contrast to her husband.

Frank and his father had not yet seen each other; when they

did meet, their recognition was not remarkable for its cordiality.

Reginald Chauncey held out two of his smooth, white fingers.

"Ah! Frank, my boy, I hope you're well. Just in

time for breakfast," added he, without giving Frank time to reply.

Then, as if this reception would suffice, and he had done all

that could be expected, he opened his Times, and became

wholly absorbed in its contents.

The breakfast proceeded; Frank and his mother sustaining the

entire conversation. Reginald Chauncey seemed as far removed

from them and their subordinate interests as the Antipodes.

Frank had not as yet revealed to his mother the position in

which he stood, nor his projects for the future. I should say

project, for Frank had but one.

His early education had been to fit him for the medical

profession; and, indeed, he was fitted for it now. He had

carried on his studies when at Deepdale Manor, during the times and

seasons that other men would have chosen for recreation. But

Frank had a quiet energy that could seize upon an object, and pursue

it without slackening his hand till the object was reached.

Besides, he had his mother. It was to meet her urgent and

pressing difficulties—to prevent, in fact, absolute ruin—that he had

engaged himself as tutor to Lord Landon. The step had been

taken during a crisis. There had been many such during in the

history of Frank Chauncey.

But now his thoughts returned to their old channel. He

wished to make his way as a surgeon—then he hoped as a physician;

for in whatever walk of life he was found, there he resolved to

excel. It did occur to him, for he was young, and youth is

sanguine—it did him to him that the time might come when his mother

would be safely sheltered by him from her many trials, when better

and happier days would dawn upon them both. But at present

there would be toil and struggle—labour before rest; the seedtime

before the harvest. And it occurred to him, likewise, as he

beheld his father's countenance, serenely apathetic to all but "last

night's debate," that he would appeal in some sort to his paternal

solicitude. If there were a chord in that cold and selfish

bosom, he would try to strike it; for the man of the world, the

diner-out, the favourite of society, might, perchance, pave the way

for the young novice, especially if that novice were his only son.

When breakfast was over and his mother had retired, then was

Frank's opportunity.

Reginald Chauncey had finished the perusal of the Times.

Now he offered it with a smile of infinite condescension to Frank.

He had not asked Frank a single question touching his affairs.

It was not his habit to do so.

"I am an indulgent father," he would say to his set. "I

never interfere in any way with my son."

Frank took the paper, folded ready for his immediate benefit,

but he laid it down again."

"Father," said he, endeavouring to appear at his ease—a

difficult achievement, under the circumstances—"can I have a little

conversation with you?"

"Certainly, my son; I shall be most happy. But you are

aware that I am instantly going out," replied Reginald Chauncey.

"I have not much to say, and I will say it as quickly as I

can," resumed Frank, hastily, "I wished to tell you that I have left

Deepdale Manor."

"Well, my son, the world is before you. I am not one to

coerce you in any way. You have but to choose a profession.

I am a man of independent fortune, as you know, and tread in the

footsteps of my ancestors. But if you wish to do otherwise――"

"It is no matter of wishing, sir," said Frank,

hurriedly, but of necessity. "Not that, under any

circumstances, I would be unemployed." He paused, unwilling to

cast the slightest reflection on his father.

And during this pause, we may observe that Reginald

Chauncey's independent fortune brought him in exactly two hundred a

year. His annual expenditure was quite another matter.

"You are aware," resumed Frank, somewhat awkwardly, "that I

was educated for the medical profession. It is my intention—"

"Frank, my dear son," interrupted Reginald Chauncey, in his

blandest manner, "there is an old proverb, that time and tide wait

for no man. I have an appointment at ten o'clock, punctually,

and a little business to transact before I go. I will trouble

you to hand me the inkstand."

Frank did as he was requested, and his father began

immediately to write a note, an employment which so engrossed his

attention that he seemed to forget Frank's very existence.

When he had finished, he placed the note in an envelope, fastened it

down, and, with a serene and smiling countenance, placed it on the

mantelpiece.

Then he walked hastily to the window.

"Ah! said he, cheerfully, and with alacrity, "I see the cab

at the door. Good morning, my son!"

And, touching Frank's hand with the tips of his well-pared

nails, he quitted the room.

There was a slight confusion in the hall as he took his

actual departure. There were sounds of a coat being brushed,

and sundry final touches being put to his outdoor toilette.

But, when the toilette was completed, Reginald Chauncey—got up to a

state of perfection, from his glossy hat to his well-polished

boots--got into the cab and drove off.

CHAPTER XV.

A CONFIDING PARENT.

FRANK turned from

the window with a bitter sigh.

It was hopeless to build upon the sand—to extract sweetness

from wormwood, or to pluck figs from the thorns of the desert.

Equally so to find a vein of parental sympathy in the callous breast

of Reginald Chauncey.

Yet sympathy is a precious boon to struggling, suffering

humanity.

He sat down by the fire, and having gathered the few

scattered embers together, began to look his fortune steadily in the

face. Not with despondency. No; a more sanguine nature

than Frank's rarely existed. Nor with discontent and repining.

He had all the cheerfulness of youth, and of Christianity too: for

what a great mistake it is to suppose that being a Christian means

being, if not wholly miserable, at least melancholy and

low-spirited, and submitting to a despotic and unrelenting sway!

To be a Christian is to have your burden cast upon One who cares for

you, and fills your breast with a "larger hope" that leaves no room

for doubt or despair.

Frank was, as we said before, fully resolved to become a

medical practitioner. He was prepared for taking this step.

Ere he had been driven to Deepdale Manor he had duly passed his

examination and walked the hospitals. There would be nothing

to do except get his diploma and at once enter on his profession.

Had the countess been content, Frank had remained some time

longer, for he had found the solution of Phil's character and

capabilities.

But, now, he would at once make for himself a position, if he

could; and a name.

There was another theme connected with Frank's residence at

the Manor, on which he dared not dwell.

Among the ideal scenes which his fancy chose to paint, there

would ever appear the dovelike eyes, the auburn hair, the serene

countenance of Lady Lucy.

He had never breathed a syllable of love, not even in its

remotest stages. He was too true a gentleman—too honourable a

man. But he loved her, notwithstanding, with all the zeal and

fervour of his nature. Lucy only knew that she had lost a

friend.

This theme having insidiously forced its way into Frank's

mind, he rose and resolved to shake it off by some more profitable

employment.

But ere he had time to do so; a light footstep on the stairs

announced that his mother was at hand.

If anything could cheer the forlorn destiny of Reginald

Chauncey's wife, it was the prospect of passing a day with her son.

She had few to sympathize with her—few that were even acquainted

with her sorrows.

There are some women in whom the domestic virtues are

inherent. Home is the theatre of their grandest exploits.

The home circle bounds at once their hopes, their joys, their

energies.

Such was the despised wife of Reginald Chauncey. Her

home, alas! had proved a failure and a ruin. Still —amid the

ruin, amid the decaying ashes of a world whose illusions had long

ago been dispelled—the poor woman, heroic in her faith and patience,

remained firm at her post. Not till the last fond wreck was

gone would she abandon it.

True to the instincts of her nature, she never made the son a

confidant of the wrongs practised by the husband. No; the veil

was never raised from before the grim, skeleton in Frank Chauncey's

home. Now she had come to sit with him, bringing in her hand

the work-basket with its faded silk lining, a bridal present, and

intending, as heretofore, to stitch with nimble, unwearying fingers.

She was wont to stitch alone. She was not a nervous woman by

nature, or one apt to brood morbidly, or else she had grown

hypochondriacal.

But Reginald Chauncey's wife had a solace in her woe that the

world knew not of. She was a Christian woman, with a

Christian's consolations and a Christian's joys. In that

lonely deserted room angels might have ministered to her. So

that, though subdued and chastened, she was not despairing; though

cast down, she was not destroyed.

To-day, however, was a high day for Mrs. Chauncey. She

was not alone; and opposite to her was her joy and pride,—her son,

born, as it were, for adversity.

But Frank's office on this especial occasion was not

altogether so consoling as might be expected. He had to tell

his mother of his recent dismissal. It was useless to put off

the news any longer. But though Frank's prospects were not in

his own estimation damaged by the freak of the Big Countess, his

mother would think far otherwise. She looked upon the position

of her son—"tutor to a nobleman," as she fondly observed—as one of

peculiar advantage. Indeed, she began the subject this very

morning by alluding to it.

"You continue to be quite happy, dear, at Lady Landon's?"

Frank did not immediately reply.

"It is such a comfort to me Frank, to think that you are so

well established, and under such patronage. Why, you will be

travelling with his lordship on the Continent, by-and-by."

"Mother," interrupted Frank, smiling, "there is no knowing

where your romantic tendencies may not lead you. His lordship

is barely fourteen."

"Ah! but time passes very quickly, dear; and when—"

"Mother, you must not think of it," said Frank, hastily.

"The fact is, I have left Deepdale Manor."

"Left!" repeated she. Her work dropped on her knee.

"Left! No, Frank; you cannot mean that."

"I am sorry to say that I do, mother. At least, I am

sorry for some reasons; for others I am glad."

"Glad!"

"Yes; because I mean now to set about in earnest, and make a

home for myself."

Her face looked so pale and sad. There was such a

trouble in her eyes, that Frank felt half inclined to anathematize

the Big Countess.

"Mother," said he, soothingly, "it may all turn out for the

best. I have long wished to take up a profession."

"But, my dear――"

"Besides, if you knew his lordship personally," continued

Frank, smiling, "you would not build another instant upon that

foundation."

And, partly to rouse her, partly in his own justification, he

told her how it was the dismissal had come about. He hoped to

win a smile; but no! She sighed as she took up her work; her

hands trembled, so that she could hardly hold the needle. It

may be that she knew more of life's shoals and quicksands, of its

hard and dreary passages, than did Frank.

He began to talk cheerfully and hopefully. He sketched

out his plans. His few years of struggling, it might be—he did

not shrink from them. Sheer perseverance, with God's blessing,

would gradually open the path to independence and prosperity.

He included in this prosperity a home for his mother; but he did not

say so, for it was a tender subject. "If ever she should need

it; and she surely will," said Frank to himself.

He had scarce said the words, when his eye fell upon the note

his father had left upon the mantel-piece. Unwilling to

frustrate any of the plans of the lordly Reginald, he took it up.

"Mother," he began—then he stopped, wonder expressed on every

feature. The note, or letter, or whatever else it was, was

directed to himself. To himself! "Mr. Frank Chauncey."

Much surprised at so unwonted a circumstance, he opened it in haste.

Never to the last day of his life will Frank forget the sensation

that tingled from head to foot, the unutterable horror and dismay

with which he read the words――

MY DEAR

FRANK,—It is fortunate

that you are at home. You can take care of your mother.

Ere the day is out, you will most likely receive a visit from chose

unpleasant members of society, the bailiffs. To show the

confidence I have in your judgment, I leave all necessary

arrangements in your hands. I have taken my departure.

Your affectionate parent,

REGINALD CHAUNCEY.

CHAPTER XVI.

THE VICAR BROUGHT TO THE POINT.

FOR three

consecutive days, Dionysius Curling went about with the letter

addressed to Simon Crosskeys in his pocket. He was in a state

of the utmost perplexity. To deliver it was impossible; to

keep it back equally undesirable. What was to be done?

He had formed his opinion on the matter; and he was a man remarkable

for adherence to his own principles; in fact, his disposition

inclined to obstinacy. He was convinced of the innocence of

Mrs. Melrose.

Possessed with this idea, it seemed to him that he had only

to put it forth in suitable language, and the Deepdale world would

recant. Little did he know of Deepdale!

During these three days he kept aloof from any further

interview with the widow. But, it was not therefore a sequence

that the thought of her did not run in his head continually.

Yet she was a lady, and a widow. "Widows are always artful,"

was his favourite axiom; and "to beware of the ladies," was the

point from which he started.

This woman, lying under the ban of society, accused of

positive crime, was the only one of the fairer sex that had in the

slightest degree interested him.

"It is the peculiarity of the case," thought Dionysius, as he

vainly strove to fix his attention on his beloved "æsthetics."

And yet this peculiarity could hardly justify the unwonted

train of ideas that floated through the mind of Dionysius. He

closed his æsthetical volume in despair. That very moment

Martha Beck presented herself at he study door.

"If you please, sir, here is Mr. Crosskeys."

Dionysius started in his chair. He was far gone in

reverie already.

"Ask him to walk in, Martha."

"Please, sir, he has walked in."

And ere Dionysius could recover his scattered ideas, the

redoubtable Simon Crosskeys was upon him. He stiffened into

all his natural angularity in an instant.

"Take a seat, Mr. Crosskeys, if you please."

"Thank ye, sir. Yes; I'll happen sit down a bit."

Simon Crosskeys had the faculty of making himself perfectly

at home wherever he went. He was, however, a man of business.

His time was precious. So, without any circumlocution, he burst upon

Dionysius by saying―

"And now, sir, about that paper?"

Dionysius, uneasy and perplexed, glanced round the room.

Once, he opened the volume that lay close beside him, as if there

might be, in its well-known pages, a solution of the question.

But as none was to be found, he closed it with precipitation.

Simon Crosskeys, meanwhile, spread his broad, open palms upon

his knees, and leaning forward, said, in a tone of great

significance―

"Mr. Curling, sir, what are you intending to do?"

Dionysius, more uneasy still, glanced round the room a second

time. Then bringing his eyes to bear on Simon Crosskeys, he

replied―

"I intend to do nothing at all."

"Sir?"

Simon Crosskeys had not heard that observation with

sufficient correctness.

"I intend to take no step whatever," repeated Dionysius, in a

firm, intelligible voice.

"No?"

And Simon Crosskeys glanced at him in a somewhat threatening,

certainly a very offensive, manner.

"No," repeated Dionysius; "because it is my calm conviction

that the lady is innocent."

Simon Crosskeys was still glaring. He was a burly man,

with a neck of remarkable thickness. His throat was partly

uncovered, and there seemed a large lump to move up and down in it.

Dionysius, having uttered what he fondly hoped would be the

oracle of Deepdale, relapsed into silence.

He thought he had strangled the slander, as the infant

Hercules did the snakes. But, alas, it was not so!

Bringing down his sinewy fist on the table with a force that

was remarkably unpleasant to the nerves of the young vicar, Simon

Crosskeys thundered forth, "And what may you mean by that, Mr.

Curling?"

"I mean," said Dionysius, speaking with far less stiffness

than usual, "that the proofs of Mrs. Melrose's guilt are not by any

means clear to my mind. Indeed, she appears to know nothing

about it."

"About what, sir?"

"The loss of the money."

"Loss! call it robbery, if you please, sir! In these

parts, if we means a spade, we says a spade."

Dionysius bowed politely. He did not wish to bandy

words, if he could help it, with Simon Crosskeys.

"And as to not knowing it, why she isn't likely to!

That beats everything, that does!" said Simon Crosskeys, laughing

derisively.

The sensibilities of Dionysius began to tingle. "Mr.

Crosskeys," said he, "here is your paper. I beg you will allow

me to retain my own opinion in the matter. I shall treat Mrs.

Melrose with all the courtesy and attention that the widow of a

brother clergyman demands at my hands."

Simon Crosskeys took the paper, still glaring in a menacing

manner.

"As you please, sir. You see what the Deepdale

Gazette says, sir."

"The Deepdale Gazette is a local paper, and of limited

influence," began Dionysius.

But Simon Crosskeys cut him short. "The Deepdale

Gazette, sir!" cried he, half choking with choler, "why—it's—it's

the first paper going!"

Dionysius smiled. He was not the most suitable man in

the world to combat the prejudices of the Deepdale population.

By this time Simon Crosskeys had reached the door. So

far so good! A dim persuasion floated through the mind of

Dionysius that his work was done; that, by a few words, he had

altered the current of public opinion, and cast the shield of his

protection round the character of Clara Melrose. Alas! soon

were these pleasant dreams dispersed.

Simon Crosskeys, having arrived at the door, turned round and

faced the vicar.

"If you think, Mr. Curling, to set up that woman over the

heads of us Deepdale folks, you're mistaken. If you don't have

her took up, sir, we shall; and that afore many days is over."

Having hurled this defiance at the head of Dionysius, Simon

Crosskeys withdrew.

CHAPTER XVII.

"A WONDERFUL WOMAN."

DIONYSIUS

CURLING sat immovable in

his chair. What was he to do? Certainly, he might have

managed the affair with greater tact and dexterity. He might

have conciliated Simon Crosskeys, and, by a train of reasoning,

convinced him. His science, his philosophy, his various gifts

and acquirements, ought to have stood him in some stead: but

Dionysius the man was one thing—Dionysius the scholar was another.

There are some minds, highly cultured, who bring into every-day life

a clear insight into what should or should not be done; in fact,

whose genius and acquirements are welded into wholesome union with

common sense. Such was not Dionysius. The time would come, nay, was

coining fast, when common sense would work through the crust of

pedantry, and he would mellow into a useful and estimable member of

society. But at present he was young, far too young.

One thing, however, was clear as daylight: it would be impossible to

keep the matter from Mrs. Melrose any longer. In spite of Dr. Plume,

in spite of the dangers incident to such a course, he must tell her

! What if he were to convey the intelligence in writing? That might

do; but them--

Ah! Dionysius Curling, you are thinking of those beauteous eyes,

that fair sorrowful face which so haunts you. You would like to

witness the effect produced by your words. Something chivalrous, and

quite newly implanted in your heart, whispers that, whatever

betides, you would be at hand to console and to defend.

The widow had left her chamber, and was now ensconced in the

drawing-room.

"She is so eager to get on," said Martha Beck, in explanation of

this change of scene.

If he had thought her lovely when attired in a loose morning

-wrapper, her hair simply gathered into a net, and her appearance

presenting somewhat of the dishabille of the sick chamber, she

seemed tenfold more attractive now. Her deep mourning dress, with

its folds of crape, set off the exceeding whiteness and delicacy of

her complexion. Her lovely hair was coiled round her well-shaped

head, and all unconscious of the disfigurement of a widow's cap. She

came to meet him, holding out her band. " I am so glad to see you!"

said she, with eagerness.

Dionysius blushed as he took the little hand and slightly pressed

it. It is astonishing how tiny it was. "I am all anxiety to hear how

my affairs aye progressing, Mr. Curling," said she. "I have so far

recovered as to be quite able to move."

"Madam, you must not think of it," replied Dionysius, with energy.

She had resumed her place on the sofa. Dionysius, a trifle paler

than usual, sat opposite.

"Excuse me," said she, in her dulcet voice, "I have troubled you far

too long. I shall never forget your kindness to me, Mr.

Curling—never!"

"I am sure," stammered Dionysius, awkwardly, "you are very welcome."

She smiled. His oddity seemed to amuse her. Then she said, "I have

written to the landlord of the cottage, and find there is no

difficulty in my taking possession of it at once."

He did not speak.

"Pray may I ask if you have seen Mr. Crosskeys?"

Dionysius winced palpably. "I have, madam," replied he, with

extraordinary stiffness.

"Well?" said Clara Melrose, interrogatively.

"Madam!--There has been some little mistake," stammered the unhappy

Dionysius.

"Not about the insurance—there cannot be," said the widow, quickly.

"It is well known that my dear uncle made that small provision for

me. No one in Deepdale would be found to dispute it."

"Exactly so, madam," again stammered Dionysius.

"I am sorry to appear covetous," resumed the widow, sighing, "but in

my position I am compelled to look keenly after my resources. Once

fairly established, I doubt not that I could maintain myself in

tolerable comfort."

"Of course, madam," replied Dionysius, wondering the next minute how

he could have said so.

"Perhaps you are not aware that I am somewhat of a scholar," resumed

the widow, smiling. Her smile was wonderfully captivating to

Dionysius. "My dear uncle drilled me thoroughly in Latin and Greek.

He had an idea that women should have a classical education. What do

you say, Mr. Curling?"

"I really don't know, madam," returned Dionysius, more and more

embarrassed. "Women—ladies, I mean—are rarely able to master the

dead languages to any purpose."

"If you will allow me, I will give you a specimen of what I can do,"

said she, smiling. "I have here a Greek Homer; will you hear me

read?"

There was such a charming simplicity in the manner of the request

that Dionysius said, with fervour, "Indeed, madam, I shall be

delighted."

She took the book in her taper fingers, and a tinge of colour rising

to her cheek, partly from excitement, partly from timidity, she

began.

Oh! noble language of antiquity! language of heroes! surely you

suffered not a whit in flowing from the coral lips of Clara Melrose.

Dionysius was a scholar, remember. This was his own ground. A

blunder, even the most trifling, would have been detected. But no.

The first men of Oxford or of Cambridge might have envied the

correct and musical cadence of Clara Melrose.

When she had laid down the book, the same tinge of colour

beautifying her cheek, her eyes sparkling, and her features glowing

with excitement, he exclaimed, with an energy that startled even

himself, "On my word, Mrs. Melrose, you are a wonderful woman!"

CHAPTER XVIII.

INNOCENT OR GUILTY?

FOR the moment he

had been carried away by his enthusiasm. Not that he was an

enthusiastic man—far from it. The musical utterance of Clara

Melrose head entrapped him into this unwonted state of mind against

his will. He shared the popular prejudice of mankind against

that anomalous being called a "blue stocking."

But every rule has its exceptional cases. A fair face,

coral lips, and eyes of wondrous brightness and beauty might be

allowed to dabble in classic lore with impunity. A middle-aged

spinster is the type of womankind supposed to feed upon the dead

languages.

He had revelled in that delicious morsel of Greek—fresh, as

it were, from immortal Hellas. His correct ear had tested it,

syllable by syllable, and found nothing wanting. Each word had

rung out clear and musical as a silver bell. Yes, he was

fascinated,

She laid the book upon the table, and, glancing shyly up at

him, said, with all the simplicity of a girl, "You think it will do,

sir?"

Alas, for poor Dionysius! His thoughts, floating away

into cloudland, were arrested as by a grip of iron; and a voice

seemed to sound in his ear the ominous words, "Simon Crosskeys."

The look of pleasure died out of his face so quickly, and the

embarrassment and distress expressed themselves so vividly in its

stead, that the widow, little knowing what was in store for her,

said, "You need not be afraid of speaking plainly, Mr. Curling.

I am, perhaps, out of practice."

"Madam," said Dionysius, eagerly, "you read like a 'first

class.' There is no fault whatever to be found with your

Greek."

Her face brightened up.

"Then, sir, as the vicar of the parish, will you kindly use

your influence to recommend me?"

"Madam," exclaimed Dionysius, the horror of his position

driving him to extremities, "it would be impossible!"

"Impossible?"

The small graceful head drew itself up with a touch of

wounded pride; her eager eyes fixed themselves on Dionysius while

she repeated, "Impossible?"

"Under the circumstances, it would," replied Dionysius, his

face white with alarm and perplexity.

"Under what circumstances, Mr. Curling?"

She spoke in a clear steady voice, not without a touch of

authority.

He had taken the Greek volume into his hands, and was playing

with the leaves. His restless, nervous fingers were unable to

keep still a moment.

Mrs. Melrose was looking at him quietly and without a trace

of confusion. Surprise was the prominent expression visible on

her features.

Dionysius was in for it now. To do him justice, his

hesitation, at this juncture, partly proceeded from a desire to put

his communication into the least painful and offensive form.

But as, whatever attainments he might have made in other languages,

he was by no means proficient in the use of his own, he broke down

at the onset. Some men have a graceful and insinuating

address, and can garble any statement, however unpleasant. Not

of this stamp was Dionysius Curling. He blundered out, with

all the abruptness and stiffness of which he was capable, the words—

"I am very sorry, madam—it grieves me to the heart to say

so—but I am informed by some of the most respectable inhabitants of

Deepdale, that you have been guilty—"

He paused. Man as he was, he trembled from head to

foot.

She had risen, and was gazing at him in blank astonishment.

"Guilty!" said she, quickly, and, as it seemed,

sharply―"guilty of what?"

She had come quite close up to him in her eagerness. He

shrank away alarmed—and yet with a feeling of fascination too—and,

agitated far more than she was, stammered out the whole story, as he

had read it in the pages of the Deepdale Gazette—the story of

Clara Melrose's guilt.

He did not once glance up, though that he should have done so

was the pretext for this interview. She was so near to him

that he could distinctly hear the beating of her heart.

There was a profound silence.

All at once she moved to the sofa. Dionysius looked up

then. She was pale, and her lips moved, and her brow was knit.

She raised herself to her utmost height, as if confronting

Dionysius. He might have been the culprit—she the judge.

"Who dares to say it?" asked she, sternly—so sternly, that

Dionysius shivered.

Still, here was an opportunity, never, perhaps, to occur

again. He would hear from her own lips the words—innocent, or

guilty. Still, whether she should tell him or no, he could

declare to all the world that she was innocent!

"Mrs. Melrose," said he, "I am a comparative stranger in

Deepdale, and therefore unable to judge, from your previous history,

whether this strange and improbable story is correct. But your

assertion will have sufficient weight with me, for I am not to be

moved by popular clamour. Are you innocent, or are you

guilty?"

She stood; her figure still drawn up proudly, her head and

face in full relief. A sunbeam, straggling down upon her from

the half-raised curtain, invested her with a kind of glory, as she

said, "I am innocent!"

CHAPTER XIX.

THE RESOLVE TO "LIVE IT DOWN."

"I KNEW it!"

cried Dionysius, with fervour, and as from the bottom of his heart;

"I knew it!"

The man—stoic, cynic, whatever you might call him, was

actually in tears.

She moved from the sofa. Her face had lost its

sternness, and her lips quivered painfully. It must come, and

it did—the passionate storm of weeping, the raining of crystal drops

from her azure eyes. For she was a woman, caught, as it were,

in a snare—a very pit of destruction!

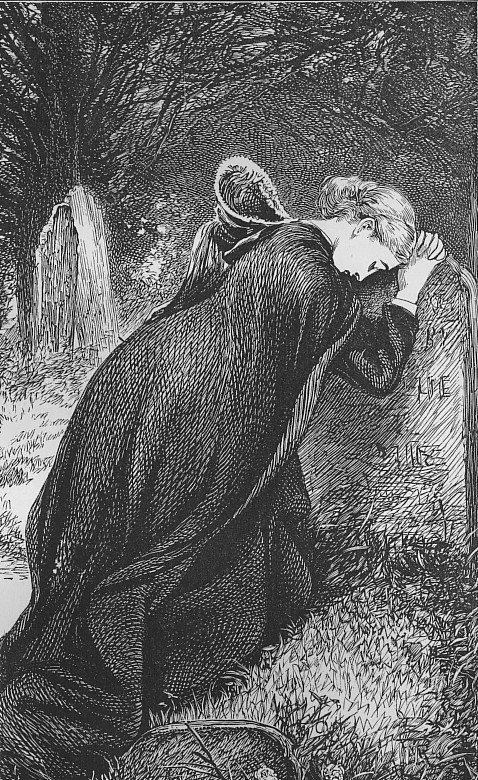

She wept; and Dionysius stood and beheld it. His eye

gleamed as, perhaps, it had never gleamed before. His face was

flushed—nay, almost eloquent. A mighty change had come over

the Vicar of Deepdale.

When the storm of grief was past, Clara Melrose looked up,

and pushed back the loosened hair from her damp forehead.

Tears add to the beauty of some women, and they did to hers.

Her eyes seemed all the lovelier for those rain-drops hanging from

their silken lashes. She had sat down to weep, and had rocked

herself to and fro, and made all the pitiful gestures of a woman

frantic with despair. But this had passed. She grew

calmer—calmer by far than he was.

She held out her hand. It was a spontaneous movement,

as if in him she recognized the only friend left to her in the

world. He took the hand. It was yet tremulous with

emotion. As it lay in his grasp it seemed to quiver. He

pressed it gently and respectfully, and, dropping it, retreated a

few paces.

Then, she thanked him for his generous sympathy, and

convinced him, while he listened, more entranced than ever, that the

slander contained in the Deepdale Gazette was improbable and

impossible. It had either been got up by some malicious and

secret enemy, or was the result of a mistake. Under either of

these circumstances, her plan would be to live it down—here at

Deepdale.

He started. The very idea was alarming. Still, it

had a sweetness about it, too. He had been saddened, as be

thought that she would fly—miles away—never again to be seen or

heard of. He fancied her womanly timidity would cause the

natural adoption of such a policy. She would flee, and be seen

no more. But to discover that she had the courage to stand her

ground, and abide where he could cast his protecting shadow round

her—this was very grateful to the feelings of Dionysius. He

was not a man of business, and ill able to advise her in an affair

of such intricacy. But it was inexpressibly sweet that,

notwithstanding this deficiency, she took him into her entire

confidence.

She declared her intention of immediately removing to the

cottage. In order to do so, she told him that it was necessary

she should be put in possession of the sum of money, which was hers

by right. This money—the hundred pounds mentioned above—was

most probably lying in the bank at Mansfield, the nearest market

town. As the services of Simon Crosskeys were likely to prove

unavailing, she requested Mr. Carling to apply on her behalf to the

authorities of the bank; in fact, to procure her the money.

The proceeds of the furniture had been, doubtless, sunk to defray

the debts contracted by the late vicar after his loss.

And here Clara Melrose wept again, and her tender heart was

well-nigh broken at the thought of what the old man had had to

suffer. "Would I had never left him!" cried she, clasping her

hands and raising her beautiful eyes to heaven. "Alas! had I

but foreseen such a catastrophe, no earthly consideration should

have tempted me from his side." When this display of feeling

was over, Clara Melrose turned to the vicar, and, with one of those

smiles which so captivated him, said, "Will you do me this kindness,

Mr. Curling?"

"Madam," said Dionysius, his heart bounding with rapture, "I

would do anything for you!"

She blushed, and cast down her silken lashes.

"The most beautiful," thought Dionysius, "and the most

injured of women!"

The very next morning he rode, post haste, over to Mansfield.

CHAPTER XX.

THE BAILIFFS IN THE HOUSE.

MRS.

CHAUNCEY was, as yet, in

ignorance of the blow that was so soon to fall upon her. She

had risen, and was putting up her work in the basket with its faded

lining, when her eye glanced accidentally towards Frank―her eye,

which was so quick to discern omens of evil. The poor woman

had had an education in them. Frank saw he was observed, and

with a quick gesture crushed up the epistle, and flung it into the

fire. Not for worlds would he have his mother see it. He

could break the news to her gently.

"Frank!" said she hastily, and in evident alarm, "what is

it?"

He did not answer all at once. With suppressed emotion

he was forcing the letter into the very heart of the flames.

His mother repeated the question anxiously, and in a tone of

distress. He turned from the fire. The scrap of tinted

paper, luxuriously perfumed, was blazing fiercely. Soon not a

vestige would remain. He went towards his mother. She

was standing with the basket in her hand, but he could perceive that

her hand trembled so much that she was scarcely able to hold it.

He told her by way of preface that the letter was from his father.

"From your father! and to you, Frank—to you?"

For Reginald the magnificent had never yet put pen to paper

to his son.

"Yes, to me. It was to spare your feelings,

dearest mother," added Frank, with some hesitation; "he wishes me to

break to you the news of――"

He paused. She set down her basket. Her eyes had

a terrified expression.

"Has anything happened to him?" she gasped, violently

agitated.

"No, no; nothing whatever."

"Thank God for that!" cried she, clasping her hands.

"If he is safe, and you are safe, I can bear any other trial."

Frank was silent.

"It was very kind of Reginald," continued she, wiping her

eyes, "to wish to spare me."

"To spare her!" thought Frank.

There was no great difficulty in telling her the news.

It was an event she had expected to happen for many a day. She

only bowed her head in meek submission. Far otherwise had he

told her, what he feared was the case, that her husband had deserted

her. She was a woman of sterling honesty, and a quick sense of

justice. The consciousness of debt had eaten into her soul

like a canker. She had, personally, exercised the self-denial

of an anchorite; but her efforts had been futile. When she

would have built up, another had destroyed; and that other her

husband. True, however, to the instincts of her nature, her

first thought was of him.

"Where is he, Frank? When will he come home?"

"I do not know, mother."

"Ah, I wish he were here!"

The words were spoken with a wail of yearning affection.

Frank, scarce able to control his feelings, walked to the window.

A weight like that of an incubus pressed upon his usually happy

temperament. He felt as though, indeed the sins of the father

were being visited upon the children. Two sharp knocks at the

front door startled him. He turned hastily round to his

mother. She had heard them, and, as if apprehending the full

misery and disgrace that was about to ensue, had sank upon her knees

in the attitude of prayer.

He left her still kneeling. From his own heart there

went up a short petition that God would sustain and comfort her, for

he knew that the moment of distress had actually arrived.

Two men were at the door. Only a single glance sufficed

to tell Frank who, they were and what was their errand.

They were the bailiffs come to take possession.

"Is the governor at home?" said the elder and more forward of

the two.

"No," replied Frank, quietly.

"Are you his son, young gentleman?"

Frank, a kind of shiver running through his frame, replied

that he was.

"All right," replied the man, taking a writ from his pocket.

I've got to serve this upon Mr. Reginald Chauncey, Esq. It be

a distraint, sir; and we're come to take possession."

It was a bitter moment for Frank. In this world the

innocent suffer for the guilty. Frank was innocent. He

owed no man anything. He was just, upright, and honourable;

and yet, here he was in colloquy with the bailiffs.

The men had stepped into the hall, and were looking about

them.

There was not much to look at. Bare walls once

handsomely papered, but from which the paper in some place hung in

strips; a stone floor, clean, but bare and comfortless; a worm-eaten

table, and a solitary chair. This was the entrance to Reginald

Chauncey's home. Poverty had eaten out the heart of all which

he once possessed—at least, not poverty, but extravagance.

Frank, stricken dumb with shame and anguish, stood a few

moments in silence, until the elder of the men roused him.

"Well, sir, are we a-going to bide here all day?"

Frank started; then, leading them into the kitchen, he said,

hurriedly, and in a tone of distress―

"You shall have all you want; but may I beg of you to be

considerate to my mother?"

"Is your mother in the house, sir?"

"Yes."

"And not the governor?"

"I told you―" began Frank, but the man stopped him.

"I see—I see! And more's the pity, sir, I say!"

interrupted he. "Well, sir, we want nothing in the world—only

a bit of baccy and a drop of beer; and you may be sure we won't

ill-convenience the lady no ways."

"Thank you," said Frank, warmly; and, having purchased the

goodwill of the bailiffs by a trifle of money, he left them.

CHAPTER XXI.

A WIFE'S LOVE CAN SURVIVE THE WRECK.

FRANK left the

bailiffs to return to his mother. As he walked upstairs, not

with his usual elastic tread, his heart felt heavy within him.

No tender bond of union had subsisted between Frank and his

father. He would not grieve after him with the pangs of

wounded affection. Still, it was a blow which might almost

crush his mother.

His mother was in the same attitude in which he had left her.

Frank had to touch her ere she moved, and then she rose to her feet

with difficulty.

A kind of decrepitude seemed to have come over her. She

sat on the sofa, and looked helplessly round the room—a strange sad

contrast to her former state.

"Frank," said she, eagerly, "is your father come?"

"No, mother, he is not."

He began to speak soothingly, and to utter words of

encouragement and of hope; but his mother heard them not; her eyes

roamed restlessly to and fro, and again she said, eagerly―

"When do you think he will come?"

"I cannot tell, dear mother. He may think it more

expedient to stay away for the present."

"Oh, no! no!" she cried, half angrily. "He would never

leave me to suffer this trouble alone. Your father is no

coward, Frank."

"He knows that I am with you, mother," was all that Frank

ventured to say.

"Oh, Frank, I wish he could come!"

There was such a pathos in the tone that Frank could not bear

it. He got up, and went again to the window. It was in a

recess, screened from his mother's view; and here he wept like a

child.

When he came out, somewhat relieved by those tears, his

mother was lying on the sofa. He had never seen her in that

attitude before. She was an active woman; her small, upright

figure disdained even to lean back in her chair. Now, it

seemed as if all her vital force was gone. Frank had yet to

learn that beneath the surface, his mother's energies, nay, her very

life, had been slowly ground away.

He stooped down and kissed her. She kissed him in

return, but she did not speak. Her eyes had a wild, wistful

longing, that haunted him for many a day. He covered her with

a shawl, for her hands were as cold as death; then he stirred the

fire, and drew down the blinds, and made what little arrangements he

could for her comfort. After this he stole from the room, to

think over, in the solitude of his chamber, what had better be done.

He was now his mother's sole protector. In fact, he was all

she had in the world; and his whole mind was possessed with the

filial desire to stand as much as possible between her and the

approaching trial. In fact, if she were driven from one

refuge, he must make for her another.

"Yes," thought he, with a glow of generous enthusiasm; "thank

God, I can work."

The most immediate thing that suggested itself was to find

some suitable attendant for her in this hour of need.

Frank could see that she was ill—stricken down, in fact; and

he ground his teeth in very agony as he thought of it.

It would not be possible for her to fulfil her domestic

duties, hitherto so cheerfully and untiringly performed. No.

And had Frank had his way, she would long since have been relieved

from a burden that must have pressed heavily upon her. It was

the drop of wormwood in his cup—the knowledge of what his mother

suffered.

Quitting the house for a short time he soon arranged the

matter. An old nurse of his—a faithful adherent of the

Chauncey interests—was persuaded to come at once, and render all the

assistance in her power. He flew rather than walked along the

streets, so eager was he to return to his mother. When be had

settled her under the beneficent guardianship of old Susan, be had

another piece of business to transact. It was to institute

inquiries after his father.

He intended to pay a visit to the man who managed the legal

affairs of Reginald Chauncey, and who would be most likely to know

his whereabouts. He did not like this man—few persons did.

And, more than that, he was a total stranger to him, personally.

He had never seen him in his life. Still it was necessary

something should be done to allay the feverish anxieties of Reginald

Chauncey's wife.

Frank hoped to find her reposing in same tranquil attitude in

which he had left her. But alas! no. She had risen.

The shawl with which he had so carefully covered her lay upon the

floor, and she had been for some time pacing up and down the room.

When Frank's step was heard, she stopped; her eyes turned

towards the door with the same wistful, yearning look. Frank

knew but too well what it meant. She fancied the footstep

might have been her husband's.

"Frank," said she, hastily and impatiently, "he is not come

yet?"

"No, mother."

"Where is he?"

Frank shook his head.

"My dear, I want to write to him. Poor Reginald!"

Frank's eyes were fixed upon the ground. The grave

expression of his face deepened into actual distress.

"Poor Reginald!" continued the wife, pleading, as it were,

his cause; "he had but a narrow income, Frank, and with his

acquirements and position he was sure to outrun it. Many men

have done so besides him," added she, appealing to her son.

Frank was silent. He could not force himself to say a

word in extenuation of Reginald Chauncey's guilt.

"And now," continued she, with the same piteous, yearning

tone, "I should like to go to him. Where is be, Frank?

You must know; you are not to keep it from me," pressing her hands

to her temples, as if the pain there were intolerable.

"Mother, I do not know as yet."

"As yet! When will you know?" asked she, coming close

up and peering into his face with her eager eyes. "When will

you know?"

"Perhaps when I have seen my father's lawyer. He may be

able to tell me."

"Will he? Then you must go at once. Oh, why did

you put it off so long?" cried she, reproachfully; her fragile form

trembling from head to foot.

Alas! Frank little knew the deadly sickening fear that

was gnawing at her heart—the dread lest Reginald Chauncey should

come no more. For the love of some women can survive the wreck

of all things!

CHAPTER XXII.

"£12,000."

THE offices of

Reginald Chauncey's lawyer were situated in a paved court, close by

the market-place.

The name of the lawyer was Solomon Twist. He did a

pretty extensive business of a certain kind, both in town and

country.

Some people said he was more of a money-lender than a lawyer;

and others declared him to be a Jew, and connected with a Jewish

house in London. Certainly his first name was Jewish, and so

was his physiognomy. He was seated in his little room,

presenting, as he always did, very much the appearance of a spider

lying in wait for a fly, when his clerk (his familiar spirit—so said

the public) brought him a card, bearing the name of "Mr. Frank

Chauncey." Solomon Twist took it, and smiled.

"Show him in, Jacobs. Yes; I'll see him."

A good-natured manner had Solomon Twist, at times.

A moment after, in walked Frank. Solomon Twist scanned

him from top to toe. He had jotted down all Frank's

characteristics in his mental note-book ere Frank had time to say

good morning. When he had finished, he said: "Glad to make

your acquaintance, Mr. Frank. You favour your father

wonderfully. I never saw such a likeness!"

Frank bowed in reply to this speech. He was not glad

personally, to make the acquaintance of Mr. Twist; and he would not

say he was.

"And now, sir," continued Solomon Twist, rubbing his hands

softly together, "what can I do for you? Want money?—eh?"

There was something so repugnant to Frank's feelings in the

question that he replied, rather curtly,―

"No, Mr. Twist; I do not want money. My business is of

another nature."

"Indeed; and pray what may it be?"

Frank coloured painfully, and every nerve quivered with

shame, as he said―

"I came about my father."

"Oh, my friend Reginald! Ah, unpleasant circumstance,

very!" said Solomon Twist, carelessly.

Frank bowed his head a moment in terrible humiliation.

"Could you tell me," he asked, at length, what is the amount

of my father's liabilities?"

"Twelve thousand pounds."

He said it glibly; and getting up, stood before the fire, his

hands in his pockets.

"So much as that?" said Frank, sadly.

"Much! Well, I think the figures pretty low,

considering that Mr. Chauncey is a public man. Bless you! a

man must have debts. Hang me if he can help it," said Mr.

Twist, good-naturedly.

"Mr. Chauncey lived high, and gamed high," added he, as Frank

made no reply to the foregoing observation.

"Gambling debts, are they?" said Frank, hastily.

"Well, some of them. Not all."

Another pause of cruel humiliation. Then the clear,

brown eye of Frank Chauncey rested on the countenance of the Jewish

practitioner.

"Mr. Twist," said he, "do you know what has become of my

father?"

Solomon Twist shrugged his shoulders.

"A-hem! Perhaps I do, and perhaps I don't, Mr. Frank."

"Because," said Frank, earnestly, and with pathos, "he has a

wife. I have a mother, who is suffering all the tortures of

suspense. Surely this is unnecessary."

"Well, you see, in the first place, ladies are very

unreasonable. Why need she suffer?"

"Because she loves him. He is her husband," replied

Frank, with a simplicity at which Solomon Twist laughed in his

sleeve.

"Well?" said he.

"Well, it would be a great relief to her mind to have some

tidings of him, and to mine also," added Frank.

"Quite right and proper, young gentleman; but, you see, I am

not authorized to tell."

"But you will surely tell me, his son."

Mr. Twist shook his head.

"Not on any account, Mr. Frank. Mind, I highly respect

you, and am very sorry for the lady; but professional secrets never

pass my lips."

Frank thought of his mother, and sighed bitterly.

"At least," said he, rising, "one thing you will disclose to

me. Is there," and Frank spoke with feverish anxiety, "any

hope of my father's speedy return?"

"None whatever."

Frank stared at him wildly.

"None whatever," repeated Mr. Twist. Should it be any

consolation to the lady, I will venture to assure her that her

husband is in safety; but as for his return, it would be folly to

expect it."

"But she does expect it. She is looking for him every

hour," cried Frank, in a tone of deep distress.

"More's the pity," replied Mr. Twist; "for between ourselves,

Mr. Frank, he may never come at all!"

"May the good God help us!" cried Frank, distractedly; "it

will kill my mother!"

CHAPTER XXIII.

AT REST.

FRANK walked

slowly home from his visit to the office of Solomon Twist. He

found his mother where he had left her, sitting at the window.

She got up as he came in, and tottering feebly towards him, threw

her arms round his neck.

"Frank, when—when will he come?"

"Mother," said Frank, trying to preface the intelligence as

best he could, "it is very unlikely that my father would run the

risk of being arrested. You forget that."

"Oh, no, I don't. He would think of me before he

thought of that. Where is he?"

Frank, tenderly as was possible, concealing every base

feature in the character of the man who was his father, and her

husband, told her the result of his interview with Mr. Twist.

How it was certain that, for the present at least, Reginald Chauncey

would not return. He put the best construction upon the act,

though in his secret heart he abhorred it. He told her that,

in a worldly point of view, his father's course was most prudent.

That he was scarcely likely to endure the odium of the thing, now it

was made public. That he might have gone among his friends,

and be soliciting their help. He had friends and partisans

that they knew not of. He might find means, since he was a man

of abundant resources, of extricating himself from his difficulties.

Better days would perhaps come—days of re-union and of freedom from

these cruel anxieties.

He thought his mother was listening to his representations,

and had grown somewhat calmer. Alas! she heard them not.

She had heard only one fatal declaration.

Her husband had deserted her. The man for whom she had

toiled so many years, and with whom she had borne so patiently, and

without a murmur. He was gone. He had left her exposed

to the pitiless storm alone.

She had tried to keep her skeleton from the eyes of thee

world; in one sense, she had succeeded but too well. The world

ignored her existence—it fawned at the feet of her husband.

To Frank's communication she answered not a single word.

She rose, a drear wan look was in her face—a look that

haunted Frank for many a day. She kissed him; her hand was

cold as marble. She had a shrunk, withered look, as if she had

suddenly grown some ten years older; then, with a kind of shiver,

she gathered her shawl about her, and still, without uttering a

syllable, quitted the room.

The bailiffs kept their word faithfully to Frank Chauncey.

They did not, as they had expressed it, "illconvenience the lady

noway."

The house was large, and the kitchen remote; and, plentifully

supplied with beer and with tobacco, they were civil and content.

Much, however, had to be done. A man, his pen in his

hand, and his ink-horn by his side, came and made an inventory of

the furniture from the top of the house to the bottom. There

was not much of it left, and what there was—as the man somewhat

disrespectfully observed—was "good for nothing." Still, every

bit of it would have to be sold, for the benefit of the creditors.

All this was infinitely distressing and humiliating to Frank.

After the auction he and his mother would have to turn out and shift

for themselves. But none of these things caused him such deep

and increasing anxiety as the state in which his mother was now

plunged. She had not taken to her bed, nor did she even keep

her room. She rose, as usual, the morning after Frank's

disclosure, and came down to breakfast. But, alas! it would

have touched the heart of even Reginald Chauncey had he beheld her.

She could not eat. In vain Frank placed the choicest morsels

before her. In vain he entreated her to make the effort.

"I can't, I can't," was all she said.

Frank called in medical assistance. He began to grow

alarmed. The doctor encouraged him by saying there was no

disease, and no reason why Mrs. Chauncey should not recover, if only

she could rally from her depression. "If!" ah! there was the

difficulty.

Frank knew it not, but the last fibre was giving way in that

loving, broken heart.

She lay on the sofa most part of the clay, only sitting up to

take food or medicine. Frank never left her. He was

young and sanguine, and he hoped against hope. He tried to

induce her to rally. He told her of his plans and projects,

and endeavoured to rouse her to talk, or even to smile. But

no, it was all in vain!

Sometimes, as she lay, her eyes were closed and her lips

faintly moving. Then, Frank held a reverential silence.

He knew that she was praying.

One day, it was getting towards the evening, she asked him to

read the Bible to her. He did so, and then—for the true

Christian is ever a priest unto God—he prayed with her. After

that be ministered to her daily.

Still, he had not surrendered all hope. He thought if

the immediate misery were over things would mend. The darkest

hour, he argued, is the one before the dawn. He wished to

remove her from the house, and to take her away to other scenes.

He mentioned several places, but she shook her head. She

seemed resolved to cling to her home to the last.

"Until I am carried out of it," whispered she.

It was the first allusion she had made to her approaching

death, and Frank's heart failed him as he heard it. He was

sitting by her in the twilight. A faint glimmer fell upon his

mother's face as she spoke. Words can scarcely express how

pinched and ghastly it looked. He sat by her in silence.

His heart was too full to allow him to utter a word. He was

racked with a keen and cruel anguish—an anguish such as he had never

before experienced. It was the fear lest his mother should be

taken from him!

Frank, affected even to tears, was wrestling with his own

heart lest he should give utterance to a sound which might disturb

the repose of the dear one before him, when suddenly she put out her

hand.

"Are you there, Frank?"

"Yes, mother, yes." And he was bending over her,

keeping back, as best he might, the surging tide of grief.

She drew him nearer. She had his hand in both of hers,

and her eyes were fixed upon him with the old wistful, yearning look

that touched him to the quick.

"Frank, if ever—and it may be so—if ever your father comes

back to you, will you promise me one thing, sacredly and on your

honour?"

"I will, mother; I will."

"Should he return in distress—for he is not very prudent,

Frank: it is not his nature—will you receive him, dear? Will

you be kind and loving towards him? Will you share with him

what Providence gives you, and—and as much as in you lies, shield

him from disgrace?" She spoke the last words slowly and

painfully, as if they cost her somewhat.

"Mother," said Frank, his voice scarcely articulate, "I will

promise faithfully, and as before God! But surely you will

yourself, dear mother, be here. You will yourself receive—and

pardon him." He could not help the phrase; it slipped from him

unawares.

She shook her head. "Not in this world, dear; it may be

yonder." And she pointed upward, her eyes fixed heavenward, as

in a kind of trance.

There was an interval of silence. Who knows what scenes

of light and glory were not opening up to the eyes of the dying

woman? for death is to such but the beginning of life.

At length she spoke again. "There is one more request,

and only one. If he should ever mention my name, and if he

should grieve for me"—she dwelt on the idea, as if it soothed

her—"tell him that I forgive him, and that I died praying for, and

blessing him." She was silent.

Frank, overwhelmed with a horrible grief and desolation,

faltered out his reply. Then he sank on his knees by the

couch. He knew that he would not long have a mother.

And it was so. The weary spirit had gone through its

last earthly conflict. Now, the moonlight flickered on the

face which was growing white and chill as marble.

There was a faint flutter, a sigh, and then the poor despised

wife of Reginald Chauncey was at rest for ever!

CHAPTER XXIV.

A REMOVAL.

HE is a brave man

who defies to the teeth the hydra of public opinion; that is, if his

cause be a just one. Dionysius thought his cause was eminently

just. Was it not the vindication of innocence?

His first step was easy and simple, owing to the prompt,

business-like habits of Clara Melrose. She had already

communicated with her uncle's solicitor, and joint trustee with

Simon Crosskeys, touching the payment of the insurance.

This gentleman at once arranged the matter to her

satisfaction, so that nothing remained but to take up the money.

Dionysius Curling, as we know, had ridden over to Mansfield

to receive it on behalf of Clara Melrose. After the necessary

preliminaries had been gone through, the money was paid to him.

Two fifty-pound notes constituted the sole capital of the widow;

save, indeed, her learning and her industry.

The Vicar of Deepdale rode home in excellent spirits.

He had a soothing vision, all the way, of a sweet face at the

windows of the gloomy old house; and of a sweet voice giving him the

praise which he justly deserved.

He was not mistaken. The face of Clara Melrose did

appear, fair and innocent as ever, at the window. And, a

moment after, she met him in the hall, in a perfect glow of

gratitude.

"Oh, Mr. Curling, how good, how kind you are!"

Dionysius, pleased and flattered, took out his purse, and

delivered up the money. She received it thankfully, but with

tears.

"Ah! my poor uncle," said she, weeping. Then, when her

tears had dried up, which they did presently, she disclosed still

further the energy and promptitude of her nature.

The cottage, it appears, was partly furnished. She had

decided to take the furniture at a valuation; nay, indeed, had

already done so. Then she had, through the medium of Martha

Beck, found and hired a young girl, who was to constitute her whole

establishment for the present.

"Until I get my pupils," said she, smiling. And he had

scarcely digested all these facts, when she added another. She

intended to quit the vicarage that very day.

How it would be with her when she emerged from her

hiding-place, the mind of Dionysius was troubled to conjecture.

She seemed so surrounded by an atmosphere of innocence—innocence was

so stamped upon her brow—her manner and bearing bore such evidence

of it, that, after the first moment of grief and indignation she did

not appear to realise her position. Still, when she announced

her intention of quitting the vicarage, Dionysius knew that the